Keywords:

On May 4th, 2019, a lamentable act took place. We (líderes and lideresas) have been attacked… . We hope that stigmatization against social leaders and environmental activists stops because stigmatization kills—kills life, kills leaders, disappears and displaces entire communities. We hope to be guaranteed with our basic rights and to abolish structural racism in this country, and violence against women. A significant deed is that peace one day arrives to our territory because we are exhausted; we are tired of this violence; we are tired of this nation-state-led barbarism, of racism and patriarchy… . We are tired of the politics of death. Enough blood has been spilled as a result of the armed conflict and of the political and economic violence… . We want life; we love life and want to care for it.

—Francia Márquez, after an attempt to take her life1

Francia Márquez is an environmental activist and leader of the Afro-Colombian community in Cauca (southwestern Colombia). She is one of the few who have escaped murder since environmental activists, human rights defenders, and community leaders, defending land against social and environmental extraction, have become a “threat.” It is horrifying. Just in the first sixteen days of 2020, twenty human rights defenders were killed in rural areas of Colombia, more than one per day. This form of violence has increased substantially in the last three decades, dramatically in the last three years, and alarmingly in the first days of 2020.2

The collective outcry “Nos están matando” (We are being killed) was first heard in Colombia years ago, with similar outcries taking place in different neighboring countries where, likewise, displacement and forceful disappearances as a consequence of extraction practices were emergent and soon normalized.3 Moreover, it occurred where extraction was being imposed as the only social and economic logic, the most desirable one.4 Today, “Nos están matando” is a form of protest outside and across Colombia, led not only by those vulnerable but also by a whole community tired of an imposed invisibility. It is a collective call that asks the government for acknowledgment and action after its repeated claims that such murders are “systematic.”5 It is a demonstration also addressed to a world that has not yet been exposed to this terrifying news or, in a similar way, does not want to know about them.

This micro-narrative stems from the urgency of exposing a wearisome situation where violence, displacement, and extraction practices are inextricably linked. It turns to the actors who are its invisible protagonists to emphasize that this invisibility derives from practices of othering inherited from colonization.6

Extraction

The Quimbo is the biggest hydroelectric dam in Colombia and the first constructed by a transnational company, Emgesa-Enel—an Italian-Spanish company through its subsidiary Endesa. It is built just 150 km downstream from the Magdalena’s source (Colombia’s principal river) and located just 30 km upstream from another large hydroelectric dam, Betania, which has operated since 1987. The Quimbo Dam is 151 m high and 632 m long. It generated a reservoir of 8,250 ha, covering fertile lands and forests. The families affected by the land clearing for the construction of the Quimbo Dam were not consulted; many of them had already been relocated for the Betania Dam and were forced into a second relocation; six towns were directly affected, and approximately three thousand people have been displaced.7

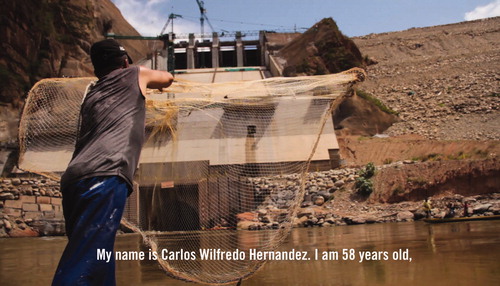

The two film stills ( and ) are from El desangre del Huila (Huila’s Bleeding, 2015) and Tierra de los amigos (Land of Friends, 2014), respectively, and are part of a larger and ongoing project entitled BE DAMMED, led by the Colombian artist and activist Carolina Caycedo in collaboration with Movimiento Ríos Vivos (Living Rivers Movement). The project investigates the effects that large dams have on natural and social landscapes in various bio-regions of the Americas and the consequences of transitioning public bodies of water into privatized resources.8 Importantly, through aerial and satellite imaging, geo-choreographies, and audio-visual essays, it exposes how water has become an index of extractivism while emphasizing the significance of water as a common good.

Figure 1. Carolina Caycedo y Jonathan Luna, El desangre del Huila/Huila’s Bleeding (Still), 2015, HD video, 12 min. (Image courtesy Carolina Caycedo.)

Figure 2. Carolina Caycedo, Tierra de los amigos/Land of Friends (Still), 2014, HD video, 38 min. (Image courtesy Carolina Caycedo.)

Both stills are powerful and telling. In the first still, the foreign corporate structure of the dam under construction stands abruptly facing the fisherman, his embodied labor, and the land and water that he and his family have inhabited and possibly lived from, cared for, and protected for generations. The openness of the fishing net (atarraya) is superimposed with the concrete dam in the back; the malleability of the woven net contrasts with the impermeability of the solid structure behind. For Caycedo, this re-presents the complex interrelations between the construction of dams and social repression—here understood as an instance of power that interrupts the flow of the social and community organization.9 In the second still, a satellite photograph is superimposed with black ink and brush, highlighting the forceful and painful intervention to the territory.

Caycedo’s work is among the most important to address nationally and internationally the consequences of the Colombian mining industries and extraction practices, which by the late twentieth century were still little discussed in the news. Local mining industries, together with other forms of extraction practices, have only recently been repositioned at the center of the Colombian government’s and other legal and illegal groups’ political agendas. This is largely due to the reduction in confrontations between armed groups, such as guerrillas and paramilitaries, following the signed peace treaty (2016) between the government and the main guerrilla group—las FARC—as well as to the pressing demands from mining corporations. Practices of extraction in the form of mining and hydroelectric dams are being promoted by multinationals, backed up by the government, and presented to the nation as “progressive” projects. But they are projects conflicting in nature and even more problematic because they are further entangled with practices of forced migration taking place in rural areas of the country where processes of land redistribution are also taking place. In some cases, these territories were formerly controlled by FARC guerrillas and sitting today at the margins of existing illegal armed groups.10

In Colombia, a country with a wealth of natural resources, the looming prospect of these expansive projects has once again put all ecosystems at risk, thus directly impacting the national (and global) environment. The rivers have been greatly affected by all decisions about mining and its regulations; social and natural landscapes are being eroded; and whole communities are being forcefully and violently displaced from their territories. Collectives, organizations, and individuals in rural and urban lands, those who mobilize in defense of these territories, have become targets of constant attacks that aim to constrain their spaces of action.11 The murder attempt on Márquez is one example. Movimiento Ríos Vivos, which has been standing against the Quimbo for many years, is yet another of many others. On September 17, 2013, Nelson Giraldo Posada, at thirty-one years of age, was shot dead. Posada was Movimiento Ríos Vivos’s leader. He was then in charge of a group of fifty people affected and displaced by the Hidroituango hydroelectric project, another large dam, in northwest Colombia.12

Othering

Just before her murder in October 2019, leader of the indigenous Nasa community, Cristina Bautista, voiced the following: “If we keep silent, we get killed, and if we speak too. So we speak.”13 These words echo those of Márquez and Posada, who, like many, have been threatened or murdered defending their land from legal and illegal extraction practices. For Bautista, “we” not only stands for environmental activists but also for community leaders whose race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality have been mobilized in definition and identification as Others and, thus, as targets of historical and physical disappearance. This consideration of the Other as a vulnerable minority, instead of as central pillars of biopolitics related to a specific region, is a clear example of what Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano denominated as “coloniality of power,” where “the fundamental axes of the model of power is … around the idea of race, a mental construction that expresses the basic experience of colonial domination.”14 Therefore, Quijano argued, the model of power is globally hegemonic today—and the control of power in global capitalism presupposes an element of coloniality—in this case, bound to the long blood history of Colombia, like in many other previously colonized countries.

Colombia’s colonization process (as in many other formerly Spanish colonies) operated through dispossession of land along bodies of water. The Magdalena River, as well as many other rivers, allowed colonizers to reach land and to therefore introduce slavery while displacing, controlling, and eradicating indigenous populations. Drawing upon Quijano, stepping out of the colonizer’s vessel meant stepping onto the land of a “new world” and of renaming the native populations as Others.15 Those conquered through violence were “condemned to a zone of non-being, stripped of humanity, rights, and self-determination.”16 This is how otherness, the separation between humans (i.e., Europeans) and nonhumans, emerged and how categorizations, such as the natural primitive, the indigenous, and the enslaved, products of “Western eyes” in Chandra Talpade Mohanty’s words, were legitimated.17

The ongoing assassinations not only prove that even today othering practices in the form of murder, racism, and forced migration have survived colonization. They have also been further legitimized by the advent of republican systems of governance, modernization, and development, as Silvia Cusicanqui and others have argued.18 An urgent matter of concern is how they still permeate consciousness, social relations, and relations of power on which economies of extraction, such as hydroelectric dams, are based. This calls to mind an excerpt from the “Feminist Manifesto Against Large-Scale Mining and the Extractivist-Patriarchal-Colonial Model,” as it still seems to echo today’s situation: “We are Latin American women and our identity was forged in the resistance to the colonial conquest of our territories and the pillaging of our land’s commons. After more than five centuries, we continue to face ever-renewed forms of colonialism and patriarchy, now at the hands of transnational corporations who, backed by national governments, plunder and steal our common goods, thus moving forward with the silent genocide of our people.”19

These words draw attention to and emphasize the main aims of this micro-narrative, as many others have done in different media and through different voices: an urgent conversation is still required to address these systematic and continuous ways in which processes of resistance have been criminalized and persecuted, leading to the murder of those who are sustaining, maintaining, and caring about life, bodies of water, and land. There is a blindness toward consequences of extraction practices, land protection, and distinctive local everyday realities—phenomena that in this case are one and the same. What makes me expose this terrifying reality through this writing, and in this publication platform, is a need to confront that legitimation and perpetuation of the Other through marginalization and murder, and to contribute to stopping the invisibility inherited from colonial differences that have kept this situation, as with many others, marginalized. “Nos están matando.” We are being killed, and it needs to stop.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Catalina Mejía Moreno

Catalina Mejía Moreno is lecturer in architectural humanities at the Sheffield School of Architecture. She studied in Colombia and the UK. Her Ph.D. from Newcastle University explored material practices to different photographic canons. Her research has been funded by the DAAD and the Getty Research Institute. She was Andrew W. Mellon Fellow at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), 2016–2017. She is also a member of editorial board of the Birkhäuser Exploring Architecture book series and of the scientific committee for the Dearquitectura (Dearq) architecture journal in Colombia. Interested in the ethics of collaboration, her recent work and research interests explore critical ways of decolonizing and reenergizing architectural humanities, history, and theory teaching.

Notes

1 Francia Márquez, “Francia Márquez: “Defender el territorio nos cuesta la vida,” Caracol Radio, May 4, 2005, https://caracol.com.co/emisora/2019/05/05/popayan/1557015127_780594.html.

2 The UN registered 683 murders of communal leaders or landowners between 1994 and 2014, and 462 between January 1, 2016, and February 28, 2019. By the end of 2019, a social leader was being killed every four days. By 2020, the rate has increased to more than one per day. See “Un líder asesinado por dia,” Revista Semana, January 18, 2020, https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/asesinato-de-lideres-sociales-uno-por-dia-en-2020/648542. Other independent platforms reporting daily assassinations include Pulzo and Pacifista.

3 See “Latin America and the Caribbean, Building on a Tradition of Protection,” special issue of Forced Migration Review, no. 56 (October 2017). See also Global Report on Internal Displacement, 2019 from the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (IDMC). https://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2019/ (accessed July 10, 2020).

4 Mara Viveros-Vigoya, “From the President,” Forum: Latin American Studies Association 50, no. 4 (Fall 2019): 1.

5 Ángel Ocampo Rodríguez, “Gobierno dice que no hay sistematicidad en asesinatos de líderes sociales” In: La FM, 15 January 2020, Accessed: July 10, 2020, https://www.lafm.com.co/politica/gobierno-dice-que-no-hay-sistematicidad-en-asesinatos-de-lideres-sociales. The following article deliberately responds to the claims of murders as “aleatory” Diana Manrique Horta, “Asesinato de líderes sociales no es aleatorio,” UN Periódico Digital. Accessed: July 10, 2020, https://unperiodico.unal.edu.co/pages/detail/asesinato-de-lideres-sociales-no-es-aleatorio/

6 Breny Mendoza, “Coloniality of Gender and Power: From Postcoloniality to Decoloniality,” in The Oxford Handbook of Feminist Theory, ed. Lisa Disch and Mary Hawkesworth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

7 Carolina Caycedo, “‘We Need the River to Be Free’: Activists Fight the Privatization of Colombia’s Longest River,” Creative Time Reports, March 17, 2015, http://creativetimereports.org/2015/03/17/activists-fight-privatization-colombias-magdalena-river/. See also Carolina Caycedo, “BE DAMMED Interviews Brochure,” December 2013, http://carolinacaycedo.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/BeDammedDAADBrochure1.pdf.

8 Carolina Caycedo, “BE DAMMED (ongoing project),” Accessed July 10, 2020, http://carolinacaycedo.com/be-dammed-ongoing-project.

9 Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 95.

10 Mounu Prem et al., “Civilian Selective Targeting: The Unintended Consequences of Partial Peace,” SSRN, July 19, 2019, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3203065.

11 Camila Esguerra-Muelle et al., “Introduction,” Forum: Latin American Studies Association 50, no. 4 (Fall 2019): 4.

12 “Comunicado, denuncia, Movimiento Ríos Vivos,” Movimiento Ríos Vivos, September 19, 2013, https://riosvivoscolombia.org/asesinado-lider-del-movimiento-rios-vivos/. References to this murder can also be found in Carolina Caycedo’s work.

13 “‘Si callamos, nos matan, y si hablamos, también’: palabras de líder indígena antes de ser asesinada,” Noticias Caracol, posted October 30, 2019, YouTube video, 2:42, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hy8cp3TWSk8.14Aníbal Quijano, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Social Classification,” in Coloniality at Large: Latin America and the Postcolonial Debate, ed. Marael Montaña et al. (London: Duke University Press, 2018), 181.15Quijano, 181–224.16Quijano, 181–224.17See also Maria Lugones, “Toward a Decolonial Feminism,” Hypatia 25, no. 4 (Fall 2010): 742–59.18See Mendoza, “Coloniality of Gender and Power.”19“Feminist Manifesto Against Large-Scale Mining and the Extractivist-Patriarchal-Colonial Model,” Observatory for Mining Conflicts in Latin America (OCMAL), 2013, ocmal.org. This source was referenced in Martin Arboleda, Planetary Mine, Territories of Extraction Under Late Capitalism (London: Verso, 2020), 68.

14 Aníbal Quijano, “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Social Classification,” in Coloniality at Large: Latin America and the Postcolonial Debate, ed. Marael Montaña et al. (London: Duke University Press, 2018), 181.

15 Quijano, 181–224.

16 Quijano, 181–224.

17 See also Maria Lugones, “Toward a Decolonial Feminism,” Hypatia 25, no. 4 (Fall 2010): 742–59.

18 See Mendoza, “Coloniality of Gender and Power.”

19 “Feminist Manifesto Against Large-Scale Mining and the Extractivist-Patriarchal-Colonial Model,” Observatory for Mining Conflicts in Latin America (OCMAL), 2013, ocmal.org. This source was referenced in Martin Arboleda, Planetary Mine, Territories of Extraction Under Late Capitalism (London: Verso, 2020), 68.