Keywords:

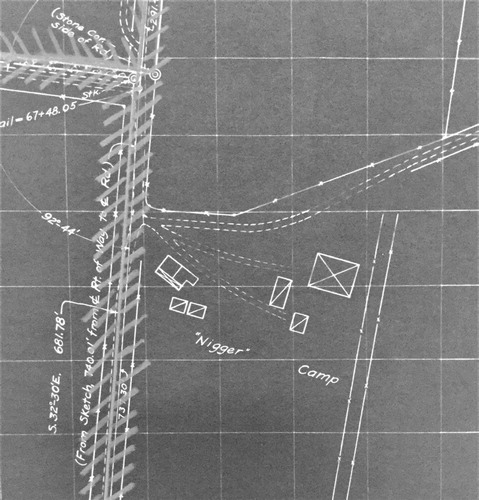

The measured drawing of a “‘N_____ ’ Camp” is a small speck in a sea of information contained in an atlas of New Village, New Jersey (). There are lands and houses with their owners clearly cited, large curvilinear shapes that define quarry perimeters, and patterns that demarcate roads and railway tracks. The camp buildings, likely built of wood, are marked on the page as permanent structures, noting their scale, orientation, and relationship to one another; immediately underneath them is the text that separates the site from all others as distinctive and even threatening. It is this juxtaposition that is most jarring: camp structures meant to be temporary and invisible suddenly appear to be concrete.

Figure 1. “‘N_____ ’ Camp” marked in Thomas Edison’s 1926 atlas of New Village, New Jersey. (Courtesy of Thomas Edison National Historic Site.)

The essay’s title therefore refers to this dual invisibility of cement and African American workers, many of whom were involved in the manufacture of this medium of modernity in the Lehigh Valley region and beyond.1 Few know that in addition to inventing the electric lightbulb and other gadgets, Thomas Edison owned a cement business. From the turn of the twentieth century through the 1930s, he manufactured this material of modernity in his New Jersey plant to build architecture and infrastructure for places as close as New York City and as far away as Cuba. Before he could produce this “grey gold,” however, Edison had to acquire limestone from the nearby quarries to then bring it to the cement plant, where it was crushed, burned, and then crushed again to manufacture cement (). While we are quite familiar with the white architects and immigrant laborers who built structures like Rockefeller Center or the Empire State Building, African American workers who quarried the vital medium have been largely lost to the historical record. There weren’t many of them—steel magnate Charles M. Schwab worked hard to make sure few African Americans migrated to the valley—yet it was their hands that chipped away at the limestone bedrock, their bodies that dragged the boulders up to the surface, and their lungs that breathed in the air thick with cement dust. For American architecture to grow taller, black bodies had to endure rigorous industrial labor.

Figure 2. Limestone quarry on the edge of the Lehigh Valley illustrates the scale of cement manufacturing operations and its impacts on nearby residences, ca. 1920s. (Courtesy of Thomas Edison National Historic Site.)

Uncovering the labor of African American cement workers is not an effort to study marginalized communities in isolation—a direction that can lead to othering. Instead, it is a call to re-center architectural history itself, putting significantly greater emphasis on cycles of labor than has been traditionally afforded. It is a way to think about architecture not merely as a series of surfaces and enclosures but also as structures of work. By bringing into focus this disciplinary ethic, scholars can expose the complexity of architectural narratives as integrated wholes rather than as distinctive case studies of identity. In other words, a study of African American cement workers who manufactured the material for the construction of concrete structures and roadways illuminates that, much like the modern American economy built upon the foundations of slavery, modern architecture was possible only thanks to the racialized labor of African Americans. It therefore matters not only who designs or even builds our architecture but also who manufactures materials involved in its construction.2 And because this component of architectural production has been severely overlooked in scholarship, we have failed to fully understand the violence that urbanization and its materials have and continue to propagate.

My discovery of the camp in Edison’s atlas unearthed numerous questions: Who were these workers? What were their names and stories? Where did they work, and how did they live? I struggled to find information that could produce any semblance of an answer. This is by no means a novel experience—scholars of African American history and culture, including Saidiya Hartman and Stephanie M. H. Camp, among many others, have long described the limits of the conventional archives when researching people whose humanity was thought not to be worthy of record, except as statistical data for measuring productivity or insurance.3 A narrative about the lives and efforts of African American cement workers is therefore one full of silences and pauses, loose ends and full stops.

African American men were employed not only in quarrying limestone for cement manufacture but also in constructing the modern built environment in the Lehigh Valley and beyond. After the 1865 passing of the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished forced labor except as punishment, Southern businesses benefitted from the influx of a nearly free workforce seasoned to endure harsh labor conditions. In states like Georgia and Alabama, African American carceral workers labored in mines and quarries, in cement plants (some of which were run entirely by prison workers), and on construction sites. Indeed, road and highway construction were often performed entirely by African American prisoners ().4

Figure 3. Convict laborers built concrete highways in Georgia and other Southern states. W. Jess Brown, “Convict Labor on Concrete Road Construction,” Concrete Highway Magazine 2, no. 7 (July 1918): 152–53.

Cement businessmen envisioned that segregation of labor was in many ways productive for business. They emphasized that hierarchies based on racial distinctions equipped local men with superior visual literacy that enabled them to distinguish good from bad concrete—identifying bad concrete was therefore not much different from identifying an African American person based on select visual cues. One manual articulated that “much like the black or red man, Portland cement gets its identity from its color.”5 In other words, the whiter the tone, the superior the product.

The pristine, stuccoed, white surfaces of concrete architecture were available only to white urbanites, however. Although African American cement workers toiled to manufacture this new material of permanence, their own environments were temporary and fleeting, removed and rebuilt over and again in new locales. The modernity that concrete brought to American cities in the shape of permanent and hygienic built environments was therefore inaccessible to camp dwellers. Instead, they resided in temporary communities, largely built of wood or other locally sourced and recycled materials.

Isolated communities of African American workers—be it limestone quarrymen, coal miners, or gold diggers—were first defined as camps starting in the second half of the nineteenth century; their specification as “N_____” or “Colored” camps was a remnant of the Civil War, which maintained segregated military and construction units throughout the conflict. The residential camps were a regular topic of discussion in local newspapers, which noted both the physical appearance and social composition of the sites. Some narrators described such places as filthy and disruptive environments that assaulted genteel values and white hegemony: “They’ll fish, they’ll throw tin cans in the water, they’ll keep us awake with their fanatical powwows.”6 Other white observers saw the camps and meetings they hosted to be a form of entertainment, in some cases even volunteering to pay African American pastors and other leaders to arrive from across the country to deliver speeches.7

Activities within the camps were not merely concerned with everyday domestic responsibilities like cooking, cleaning, and preparing for another day’s work. Instead, a major focus was presenting the African American community with opportunities for leisure and spiritual awakening. One newspaper described a local camp as a site for a major celebration, a type of fair replete with refreshments, ice cream, and confectioneries. At the center of the site was a “spacious canvas-top tabernacle within which the worshipping is done.”8 Taken directly from the Book of Exodus, the tabernacle was a temporary sanctuary built of fabric and supported by four pillars; in the Bible, Moses constructed and transported the tabernacle with the Israelites on their journey to the Promised Land. The camp therefore was a multitudinous environment that, on the one hand, provided African Americans a distraction from the toil of daily life and conditions to communally practice religion as their enslaved ancestors had done half a century earlier; on the other hand, the camp offered participants the opportunity to imagine a future marked not by racism, segregation, and violence but by self-sufficiency and independence.

Although African American cement workers rarely had the opportunity to use the material they manufactured to build their own residences and communities, they purposely avoided the cultural connotations that concrete projected. Indeed, in many ways the material represented the stability not only of built environments but also of political and social structures that materialized them. For example, cement and concrete promoters’ emphasis on hygiene emerged from the eugenics movement of the late nineteenth century, whereby cleanliness signaled physical and social normalization.9 The absence of concrete in African American camps therefore could be interpreted not as a sign of deficiency but a move toward resistance.

The exploitative dynamics of early twentieth century cement manufacture continue to haunt us today. While regulations have no doubt transformed the labor landscape in the US, many cement businesses have enjoyed similar freedoms of exploitation in distant regions that maintain weak labor and environmental laws. For example, in 2018, media outlets uncovered that the international French cement manufacturer Lafarge paid nearly thirteen million dollars to keep the terrorist organization ISIS and other jihadists at bay as the company continued to manufacture cement in Syria.10 The payments were considered to be a “tax” in exchange for the free movement of the company’s staff and goods inside the war zone. Lafarge is a historic company that has been providing cement for various notable construction projects since its first major commission in 1864—the Suez Canal. In the mid-twentieth century, the company acquired firms in North and South America and, by the 1990s, extended its reach to sub-Saharan and East Africa, as well as to China, India, and South Korea. With hundreds of plants around the world, Lafarge was not hard pressed to continue cement manufacture in Syria amid a violent civil war. Indeed, it is hard to fathom why a company would continue its already hazardous business in such extenuating circumstances, risking the wellbeing of its workers and surrounding communities. By working with the militants, Lafarge not only supported the group financially but also legitimized its gruesome operations, including slavery, murder, and rape. And yet cement manufacture in ISIS territory made sense to Lafarge executives. First, extensive destruction as a result of war meant skyrocketing demand for cement. Indeed, by keeping the kilns burning, Lafarge could ensure a monopoly on wartime and eventually peacetime reconstruction. Equally significant was the low cost of labor that the company enjoyed; limited oversight also meant that workers could be pushed to their limits while their injuries could be attributed to external circumstances. Media reports further noted that several Syrian cement workers were either captured or murdered by the terrorist organization.

While certainly outrageous, the human rights violations that occurred in Lafarge’s cement plant in Syria are not especially shocking from a historical perspective. Examining the history of African American cement workers reveals that the cement industry has always benefited from rendering manufacturing labor invisible. Of course, construction and design industries have also been complicit, consuming copious amounts of cement but never bothering to investigate where it came from or who quarried it. Similarly, while scholars have pushed the limits of architectural history by tracing the design of buildings to address questions of construction and use, they have rarely extended their queries to include manufacturers who risked their lives to procure the materials of modernity. By expanding our frame of reference to include the full chain of architectural production—from the quarry to the landfill—we can better understand the multifaceted, global, and unequal cycles of labor that continue to shape our built environments.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the valuable comments provided by anonymous reviewers, Carolina Dayer, and Richard Longstreth.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Vyta Baselice

Vyta Baselice is a Ph.D. candidate in American Studies at the George Washington University, where she is completing a dissertation on the cultural and social history of concrete, titled “The Gospel of Concrete: American Infrastructure and Global Power.” Her research is centered on twentieth-century architecture and urbanism, with a particular focus on the manufacture and dissemination of construction materials and their effects on built, social, and natural environments. Prior to entering the Ph.D. program, she earned her master’s degree in architectural history from University College London and a bachelor’s degree in studio arts/architecture from Wesleyan University.

Notes

1 In the early decades of the twentieth century, Pennsylvania was ripe for African American industrial workers. Various industries, from cement to iron and tobacco, were putting out products that were distributed across the nation and beyond; meanwhile, farm labor was unavailable due to the monopoly established by the Pennsylvania Dutch. African American businesspeople predicted that “the industrial field will sooner or later be invaded by the Negroes of Pennsylvania.” See Pennsylvania Negro Business Directory, 1910 (Harrisburg, PA: Howard, 1910).

2 Several scholars have shifted their focus from the history of design to that of labor and construction. See “Who Builds Your Architecture?: A Critical Field Guide,” Who Builds Your Architecture?, February 25, 2017, http://whobuilds.org/. Especially relevant for this essay is director Ziad Kalthoum’s 2018 documentary film, Taste of Cement, that examines Syrian construction workers building skyscrapers in Beirut while their homes are bombed during the violent civil war.

3 See, e.g., Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: Norton, 2019); Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 1–14; Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016); and Caitlin Rosenthal, Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018). Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

4 Tammy Ingram, Dixie Highway: Road Building and the Making of the Modern South, 1900–1930 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2014); and Alex Lichtenstein, Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South (New York: Verso, 1996).

5 Henry Colin Campbell, Concrete on the Farm and in the Shop (New York: Henley, 1916), 10.

6 Robert W. Chambers, “The Shining Band,” Beverly Tribune, July 5, 1917.

7 “He Likes Colored Camp-Meetings: A Wealthy New Yorker Who Pays Well for a Unique Enjoyment,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 9, 1890.

8 “Lamokin Camp Was in Full Blast: Crowds of Colored People in the Grove on the Sabbath,” Delaware County Daily Times, July 28, 1902.

9 Preference for white-colored or lighter products has been aptly discussed by scholars of capitalism, particularly in histories of sugar. See April Merleaux, Sugar and Civilization: American Empire and the Cultural Politics of Sweetness (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015); Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (New York: Penguin Books, 1985); and David R. Singerman, “Inventing Purity in the Atlantic Sugar World, 1860–1930” (Ph.D. diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2014).

10 Liz Alderman, Elian Peltier, and Hwaida Saad, “‘ISIS Is Coming!’ How a French Company Pushed the Limits in War-Torn Syria,” New York Times, March 10, 2018.