Abstract

This essay focuses on imagination as a crucial source of innovation and makes a plea for an approach to architectural education that enables imaginative thinking about new spatial and temporal realities. It starts by foregrounding the strong connections between imagination, stories, and language. It then proposes the reading, telling, writing, and making of stories as four approaches in introducing exercises of literary imagination within architectural education that touch upon such themes as meaning, empathy, temporality, and the poetics of making. The contribution unpacks these approaches in a twofold way, pairing an academic grounding of each theme with a short narrative piece describing a pedagogical example. By means of this sequence of thematic explorations and examples, we aim to tangibly illustrate the power embedded in stories for future architects’ education.

Keywords:

Architectural Imagination

Many societal challenges of today, such as ongoing urbanization, migration, and climate change, have spatial implications that drastically alter the way in which people relate to their surroundings. These challenges demand from future architects both the capacity to develop imaginative visions on how we can shape our cities and societies in a responsible way, and careful designs attuned to the specificities of place, natural conditions, and diverse social communities. For these capacities and designs to be developed in the education of architects, courses that address methods of imagination need to become a natural part of the architectural curriculum.

It is remarkable that in architectural education, very little attention is given to imagination as a field of study. Even if imagination lies at the heart of each and every architectural project, it rarely plays a central role in studio pedagogy. Architects design, but how they use imagination to do so—how they use their creative capacity to envision new spatial situations—is not often explicitly taught or investigated in the world of architectural academia.Footnote1 We therefore argue for the establishment of imagination as a central field of investigation, and for a central role for courses on creative imagination in architectural education. We depart from the premise that through literary stories, architecture can be imagined differently than through the use of other representational forms like architectural drawings, photographs, or modern mapsFootnote2—means employed extensively by architects. Unlike these more conventional modes of architectural representation, literary language has a characteristically different influence on imagination, addressing such issues as temporality and empathy that are not easily expressed through conventional architectural drawing. It is in literature that jumps in time can be made and that the spatial experiences of various characters can be evoked.

As the shared etymology of the two words suggests, however, imagination is commonly connected to image rather than language, and seen as the capacity to develop mental images in the brain—images that are not direct perceptions of the surrounding context. As Richard Kearney noted, referring to Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, and Sartre, “most phenomenological accounts on imagination have concentrated on its role as a form of vision, as a special or modified way of seeing the world.”Footnote3 With the hermeneutic turn in phenomenology, though—an opening of phenomenology from the focus on description of perceptual phenomena to the study and interpretation of texts and linguistic accounts—there is a significant change in the connection between imagination and image.Footnote4 In his essay “The Function of Fiction in Shaping Reality,” Ricoeur also argues that the creative imagination has primarily linguistic origins.Footnote5 Ricoeur goes further towards understanding imagination in terms of language: “Are we not ready to recognize the power of imagination… Imagination would thus be treated as a dimension of language.”Footnote6 Indeed, Ricoeur affirms the potential of literary imagination to say one thing in terms of another by means of metaphors, or to say several things at the same time, creating new worlds of possibility.Footnote7 Through such literary devices as metaphor, imagination is seen as an agent in the creation of meaning in and through language, which Ricoeur calls “semantic innovation.”Footnote8 Following Ricoeur, we argue that imagination is more than the mere production of images, but rather the capacity to invent and see new worlds—and this is done first and foremost through language and narration. In a field like architecture, where innovation in terms of rethinking spatial possibilities within cultural contexts is necessary, the emphasis on examining and studying these linguistic origins of imagination seems crucial. This dimension of imagination thus has everything to do with narration, an aspect we claim as particularly relevant for and generally overlooked in architectural education.

This essay will describe how literary forms of imagination can offer knowledge and methods for architectural education. By unpacking different modes of engagement with stories—reading, telling, writing, and making stories—we will distinguish different forms of literary imagination that can offer respective exercises devised for architectural education. To develop these modes of engagement with stories, we will look at stories from various angles. First, we will look at stories and reading; what knowledge can literary stories offer about places, which meanings can the reading of urban language reveal? Second, addressing stories and telling, we will explore in which ways stories accommodate the multiple voices of communities, allowing for empathetic views that include the perspectives of users or inhabitants. Third, we will discuss how visions of alternative futures are written and how writing offers ways to move in time. Finally, we will expand on the potential role of stories in the understanding and making of architectural details by using a poetic gaze to study material cultures and processes of making.

Stories and Reading: Meaning Embedded in Place Description

Connecting the linguistic dimension of imagination with the evocation of architectural experiences, Elaine Scarry shows how literary descriptions can be more vivacious and more meaningful than pictorial images, as they depend on the active and intimate involvement of readers’ imagination.Footnote9 According to Scarry, reading a story challenges readers to actively imagine a situation. Readers may find themselves in a landscape, a city, a street, a building, a room, on a flight of stairs, or on a balcony, purely by means of literary description. Reading a good story can make the reader travel into other spaces and landscapes, and through the writer’s words imagine how life might be in another situation. There are ample examples of stories that can bring us to spaces and places we have not visited ourselves, and yet we can have an almost sensory and emotional connection to them through our very act of reading. The list of literary works providing such insights is vast.Footnote10 We can learn about Istanbul through the works of Orhan Pamuk, wander through the streets of Dublin with James Joyce, and learn about Hungarian urban and rural culture through authors such as Georgy Konrad and Peter Nadas, we can find surreal and magical experiences of cities in Latin American literature such as Claire Lispector’s accounts of BrasiliaFootnote11 or Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s atmospherical descriptions of Colombian towns, or learn about the intricate sensory details of the Japanese city through the eyes of Nagai Kafu.Footnote12

The reading of stories can attune students with the spatial qualities and atmospheres of particular places and situations. More than a source of inspiration, reading can become an analytical and interpretive approach that is productively related to places, programs, and experiences, and one that cultivates the imagination in relation to spatial thinking. In a more and more globalized world where international competition is the norm in architectural practice but also commonly the topic of design studios in academia, contemporary or historical novels can prove valuable research guides to understanding particular cities and urban cultures around the world. As students work towards a design proposal for cities they are not familiar with, novels can enrich their understanding of a place from a cultural and experiential perspective. In this way, reading stories about cities allows students to imagine themselves as part of the city’s historical milieu and to envision architectures related to the particularities of its history and character.Footnote13

In the same way that we argue for a meticulous, analytic reading of literary stories, we also argue for the innovative potential that the literal reading of the words of a place can have in an educational context. As de Certeau reminds us, the names of streets or the words we find inscribed in the city’s walls and streets may carry histories, meanings, and symbolisms that in a conscious or unconscious way can influence our interaction with the city itself: from choosing one street over another in order to reach our destination or connecting a square with feelings of happiness or discomfort.Footnote14 Reading the urban language that surrounds us as potential stories to be unpacked, understood, and carefully considered in the process of architectural analysis and design opens the path for a connection with the multiple cultural and sociopolitical layers of a place.

The following example briefly describes a moment in the course of which the city was literally read through the words inscribed in the city. These urban words and stories, after being carefully read and imagined, were meticulously collected, creating a shared archive of knowledge among the group to inform the design process of the winter design studio in Montreal ().

Figure 1. Discovering words and stories in the cold winter city. McGill University, School of Architecture, History and Theory Option, master’s program, The Word Collector Project, Montreal, Student: Olivier Martinez. Credit: Olivier Martinez.

Walking around the northern city in the winter months of January and February leaves much to be desired. Colors are more subdued, smells less prevalent, voices hushed, noises absorbed by the mass of snow covering walkways, parks and squares. Cars on the street come and go, shops follow their usual opening hours, but the mist on the glass windows hinders the view towards the interior. The city resides in a state of hibernation. A group of students, defying the cold and the snow, roamed its center. Their attention was focused on reading words and stories written on the city canvas; words and stories the snow cannot take away. Shop signs, street addresses, bus schedules, posters for missing pets, concerts or theater productions, advertisement slogans and promotion flyers, were read as stories of the city that could reveal its usual customs. They could silently disclose actions, practices, rhythms and temporalities of the city, envisioning people’s interactions with the city, commuters’ routes, consumers’ habits, inhabitants’ practices, and tourists’ preferences. Countless moments of silent automatic readings, performed daily in the city fabric (for directions, instructions, information). These readings fill the air, turning the city into a unique winter creature.Footnote15

Stories and Telling: Empathetic Design Approaches

Stories are populated and tell about the intrinsic relationship between peoples and their environment. As such, stories allow us to see architecture through the eyes of the literary characters—each with their own background, socioeconomic status, mental or physical abilities and disabilities. As De Certeau suggests, the novel could be seen as “the zoo of everyday practices.”Footnote16 Indeed, literary stories often disclose detailed information about how cities and spaces are used in everyday life, and even how characters from different social groups may attach different meanings to spatial elements, depending on their social and economic conditions, their resources and their needs.

Being attentive to these characters, learning to see through their eyes, encourages students to develop empathy for others—and, by extension, for possible users of their designs. Through the description of the lifeworld of their protagonists, stories often portray conditions of human life. For instance, through the reading of Virginia Woolf’s On Being Ill or Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, students can imagine experiences of physical pain and suffering, develop an idea of how it feels to long for physical and mental health, or find out about the advantages and shortcomings that the described spaces of healing feature. Reading J. Bernlef’s Out of Mind, students can sense and imagine what it means to suffer from Alzheimer’s disease. They can understand how the world appears to you when your memory fails you. Taking into account such perspectives challenges the students to develop empathy for the user. The abovementioned examples, describing conditions of mental or physical health, can be helpful in designing and can prove to be a pathway for students to understand the impact of their designs for such programs as a hospital, a health center, or a clinic. By developing an understanding for such mental or physical conditions, students will be encouraged to approach an architectural design for such a program with the necessary sensitivity and care.

While ‘telling’ thus refers to the very characters of a story, which can provide information about social and spatial conditions relevant for architecture, it is also in addressing sites that the idea of “telling” as a pedagogical approach can be introduced, encouraging students to address the social diversity of a site and develop empathy for different types of users. It entails the training of students to look for diverse stories, guiding them to allow the inhabitants to narrate and to share their stories, and encouraging students to connect with the different actors within a neighborhood, suburb, or municipality. Engaging in these activities makes students aware of the many different voices that comprise a place, and opens students’ architectural thinking and creative imagination to the actual events of a place. Hearing aspects of peoples’ everyday life in a place—the ways they appropriate and connect with space and architecture—offers students a valuable glimpse into the ways in which spatial elements give meaning to people’s everyday routines and habits. This approach thus cultivates a strong sense of empathy, putting the stories of the place’s actual actors at the center, rather than a top-down imposed architectural program.

Learning to unearth these stories—either the ones of the actual dwellers or the ones of the fictional characters in novels—allows the students moreover to tell stories of their own design from the perspective of the users and build their design around such stories. In this way, they learn to understand that architecture should never intend to tell a singular story or be limited to one perspective and that, instead, the role of architecture could be to include multiple stories and to offer the openness to accommodate new ones. In that way, the students’ imaginations expand with a focus on the social and cultural context of architectural practices and go beyond merely rhetorical or representational uses of storytelling.

As Caroline Dionne points out, following Ricoeur, linguistic recognition involves fictionalization as a “creative recounting and retelling of events and experiences.”Footnote17 People relate to places through stories, and indeed through the iterations of such stories. Taking this idea further to architectural education, a process of design may not only be informed by the multiple stories of a site, but may also offer a “retelling.” This retelling can be both linguistic, through the everyday language students use to talk about the social-spatial practices their projects accommodate—thus to imagine them—as well as architectural, through retelling found stories in space.

There is another creative and imaginative aspect in the telling of stories when it comes to architecture, one that has to do with “telling” as a mode of communication. By challenging students to use their storytelling skills and narrate their projects without drawings, other dimensions of the projects come to the fore, since situations of use and inhabitation almost naturally become part of the stories. Such stories can be stories of the cultural and spatial context in which the projects are situated, stories of the projects’ possible inhabitations through the perspective of the user, stories of the students’ decisions and choices as they were elaborating and developing their architectural work.

The following short description is precisely based upon “telling” the stories of the historical city center of the Latin American city of Bogotá, identifying particular characters that use the city in their own specific ways, contributing to urban liveliness through their practices.

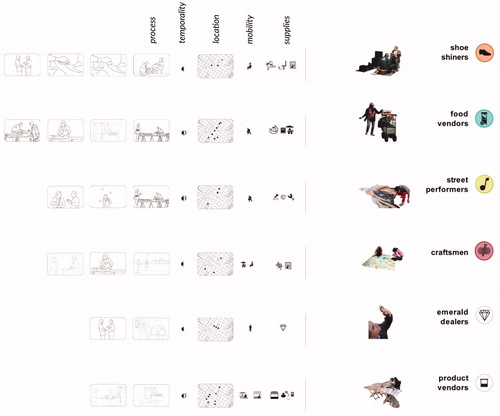

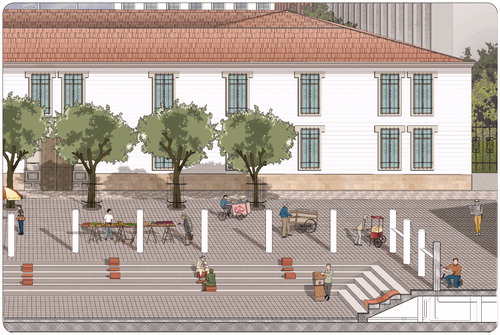

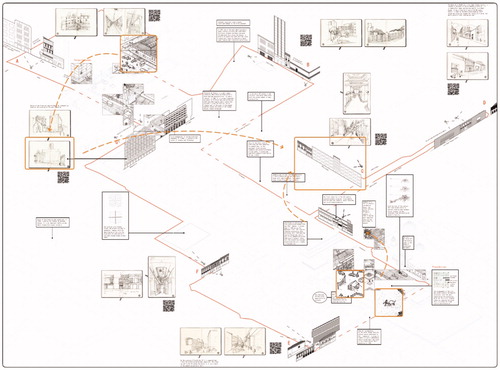

Description: Roaming the streets of the city of Bogotá, two studentsFootnote18 immersed themselves in the urban liveliness of its historical center. Making notes, sketches, videos, interviews, and sound recordings, they tried to capture stories of everyday life. Signs on buildings, fragments of interviews, sounds on the streets and repeating patterns of small everyday practices together formed a pallet of diverse stories with many voices, bringing together different temporalities of the city (). They noticed how such characters as the street vendors, emerald sellers, shoe shiners, and street artists that populate the streets of the city, are prominent figures in everyday urban life, and yet, their practices could not easily be confined to conventional building types. As an architectural analysis, the students set out to observe the spatial and temporal characteristics of these street practices: how much time do vendors, shoe shiners or street artists spend at one place? Do they move around? Which objects do they use ()? After meticulously describing these social-spatial practices, the students proposed a brief: not a brief for a building, with designated square meters, allocated rooms and technical installations, but an invitation for small gestures that would accommodate the practices of those characters that bring the streets to life. They wanted to hear the voices of those people without power and without resources, and proposed architectural solutions for their everyday stories, making the streets of Bogota safer, more pleasant, and more alive. For the presentation of their project, the students stepped back from the conventional PowerPoint slides, and instead composed an exhibition, including maps of the historical city center with written and drawn accounts of narratives, audio-fragments of interviews and recordings of street practices, and project drawings in the style of a graphic novel (), which allowed the inclusion of colorful and lively representations of the street practices in their new, imagined settings.

Figure 2. Narrative map, including façade studies, signs on buildings, fragments of interviews, and observations of everyday urban practices. TU Delft, Department of Architecture, graduation studio methods & analysis: Positions in Practice, Bogotá. Students: Valentina Bencic and Yoana Yordanova.

Stories and Writing: Moving in Time

Georges Perec stated that we ourselves are the authors of the worlds we live in: “the earth is a form of writing, a geography of which we had forgotten that we ourselves are the authors.”Footnote19 For writers and architects alike, we indeed shape our worlds through our works—by means of creating meaning through stories, and by means of literally intervening in the earth through architectural projects. Thus, with each story and each architectural project, we not only respond to existing realities, but we also imagine new conditions and experiences in space. In this respect, the temporality comes to the fore as a crucial notion that literature can address. In literature, time does not always move in a linear chronology. Stories can move in time, use flashbacks and flash-forwards, describe memories, particular moments, or imaginations of possible futures.

In the essay “Telos and Technique: Models as Modes of Action,” Marx W. Wartofsky speaks about the double nature of models in imagining future possibilities. He defines models not in the strict architectural sense—as three-dimensional physical or digital representations of an architectural proposition—but as any tool we use in order to envision a future. In this sense stories are also seen as models. Models, in this view, are not merely representations of a final outcome or product, but are rather tools to imagine the way a product, or architectural space, comes to life, the way it is constructed, or the way it could develop in the future. By selecting and imagining what is, or might be, important a story “is more than an action; it is at the same time a call to action.”Footnote20 “Stories can generate creative action”Footnote21 in the imaginative faculty of the students and tangibly expand, in terms of temporality, as a story allows one to imagine the “biography” of an object or space.

If we look again at the language that authors use in their writings, we can discover how literary techniques like narrative and sensory description, as well as exercises of creative writing, can be employed towards design, working in tandem with drawings and models. Here, Elaine Scarry’s discussion of some of the techniques used by literary writers to make descriptions vivid comes to the fore. “By what miracle,” she writes, “is a writer able to incite us to bring forth mental images that resemble in their quality not our own daydreaming but our own (and much more freely practiced) perceptual arts?”Footnote22 Using a number of literary examples she shows how descriptions of materiality, movement, vagueness of images (a moving veil, ice, smoke), or the juxtaposition of layers are used to evoke sensory experiences and invite readers to image movement, perspective, or depth. Scarry reveals, in a systematic way, techniques of story-writing that make space more vivid and palpable in language.

Such techniques, employed by students through exercises on creative writing, can allow them to think through design decisions by prioritizing the lived experience of the architecture they are creating. Writing stories during the design process, as a way to formulate strategies for action in the future, and to consider how spaces have been and will be experienced in time by using some of the tools of literary writers to make things appear more vividly, can deeply benefit students’ educational experience.

Why not extend the use of language to more performative modes and look into the actual act of writing a story as an architectural praxis that communicates spatial values and ethical concerns? The following example, from the Words in Place Project taught in the bachelor’s program at Tec De Monterrey, Campus Puebla, Mexico, did precisely this, confronting the urban environment through performative writing—not only writing about the city, jumping between its past, present, and possible future, but also projecting these words on the city itself, making the stories literally readable to inhabitants.

Description: While trained to design buildings or spatial interventions in their city by means of drawing, once upon a time, a group of students was asked to imagine and write stories on the city instead. Their city, Puebla de los Angeles in Mexico, was a complex and multilayered city story in itself, with a fascinating past and a challenging present, like many cities of the country. The students all looked surprised at the request and for a little while refused to believe that the task of an architect can also be to write stories on the city; literal stories and not stories through their buildings. But as the initial surprise subsided, the city’s surfaces started appearing as large writing papers. The walls of buildings, the asphalt of the streets (), the cobblestones of the alleys, the ceilings of the public arcades, the trees and benches of the main square in front of the cathedral, transformed imaginatively on surfaces for story writing. The stories were all about the city and for the city, communicating its urban planning failures, architectural shortcomings, spatial inequalities and injustices. Both the stories themselves and the very act of writing became exercises of spatial sensitivity and acuteness. Writing words and stories on the body of the city required a careful editing and polishing of the stories themselves, so that they could be easily perceived, seen and read in fast rhythm of the urban life of the city. Placing words on the body of the city itself required also a careful thinking of the craft and art of writing, the writing material, the writing method, the writing scale, the writing time. By the time the written stories appeared on the city, the students had no more doubts about the architectural nature of the assignment and the imaginative creativity it evoked in them and the readers of the stories, the city’s inhabitants and random passersby.

Stories and Making: the Poetics of Architectural Detail

Ernesto Grassi in Rhetoric as Philosophy (1980) takes a critical stance towards the tendency of modern scientific thinking to “equate[s] the rigor of objective thought with the provable and exclude[s] every form of figurative, poetic, metaphorical, and rhetorical language from the theoretical sphere.”Footnote23 He claims that it is only through storytelling, by use of such poetic tropes as the metaphor and by recognizing the polysemic nature of language, that one can truly grasp human truths and, as a result, formulate strategies for ethical action and valorize effective communication. Indeed, as argued by Heidegger, language is inherently poetic, capable of polysemic expression by virtue of its continuity with the body’s expressivity and gestures connected to cultural habits. “Words and language are not wrappings in which things are packed for the commerce of those who write. It is in words and language that things first come into being and are.”Footnote24

There is an aspect of craftsmanship in the construction of literary texts. Richard Sennett in his book The Craftsman tells an anecdote about the material consciousness of craftspeople, whether they are working with wood, steel, drawings, or language: “The painter Edgar Degas is once supposed to have remarked to Stephane Mallarmé, ‘I have a wonderful idea for a poem but can’t seem to work it out,’ whereupon Mallarmé replied: ‘My dear Edgar, poems are not made with ideas, they are made with words.’”Footnote25 For Mallarmé, the making of literary works indeed has to do with craftmanship; it is extensive experience with language, with the combinations of letters and words, with structure and form—in other words, linguistic experience of making, or crafting—that “makes” his writing.Footnote26 In architectural education, such a poetic approach towards craftsmanship, experimenting with the very components of a building and exploring material and structural possibilities, can be fruitful both in analytical and projective modes of working. Simultaneously, Wartofsky’s understanding of the story as a model of how things are made helps to understand making not as a merely technical exercise, but indeed as a “creative action.”

The meticulous and evocative investigation of details, observing how things are made, how materials meet, and whose minds and hands have been involved in the process of making, is a skill that poets undeniably have. By training the skill of poetic receptivity, especially when it comes to such aspects of materials and atmosphere, students learn to see familiar things anew, by wondering about their histories of making. As Gaston Bachelard noted, “poems will help us to discover within ourselves such joy in looking that sometimes, in the presence of a perfectly familiar object, we experience an extension of our intimate space.”Footnote27 Further, it is in poetry that disconnected scales can come together, as Bachelard explains: “the two kinds of space, intimate space and exterior space, keep encouraging each other, as it were, in their growth.”Footnote28

By using exercises of poetic description, students can be encouraged to investigate details as linked to the “poiesis” of architectural making. In a course focused on architecture and craft, we let students pick a detail of a site or building and asked them to meticulously reimagine how it has come together, reconstructing as it were the biography of the detail.Footnote29 What could have been the starting point, could an order be discovered, whose hands brought the materials together, in how many stages, and by which means? The detail then becomes much more than a seemingly simple corner; it becomes a microcosmos in itself, with a particular story of its making. Also in broader design studios, the poetic reading of a site or landscape can allow one to connect various scales and connect urgent questions such as climate change to concrete architectural solutions. In a master graduation studio in Valparaiso, Chile, students were confronted with the conditions of the steep hills, and the environmental challenges that came with it, erosion and drought and the consequences of human intervention such as urban expansion. In the case of student Sába Schramkó, the writing of poems helped to connect the scale of the landscape with that of the architectural detail, integrating in the entire project a sense of care. In the analytical phase of the project, she used poetry to read the landscape as a constantly shifting construct of forms, colors, textures, and movements. Through poetic writing she could, in her own words, “address the vastness of the natural landscape and the lived experience of touching a leaf, simultaneously.”

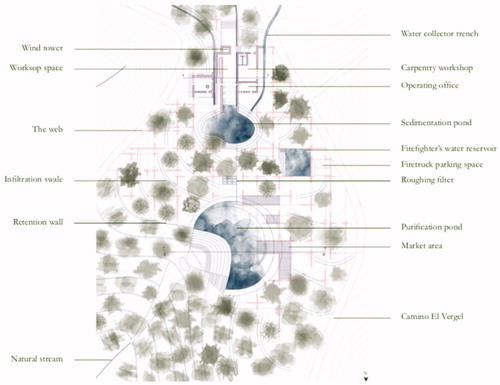

It was through the poems that the different scales came together, and it was through poems that the design process continued. The idea of weaving the branches of the trees led to the design concept of establishing a modular, structural web in the forest. The intervention was envisioned as an environmental care center that forms an integral part of the forest. The water reservoirs, the forest, the topography of landscape and the emerging buildings are all layers interconnected by the structure of the web (). Just as the concept of the web stemmed from spatial metaphors found through poetic writing, the detailed design of the buildings was born through a series of poems ().

Figure 6. Weaving: site plan of the environmental care center. TU Delft, Department of Architecture, graduation studio methods & analysis: Positions in Practice, Valparaiso. Student: Sába Schramkó.

Figure 7. Making: balancing different scales, programmatic layers, and materials. TU Delft, Department of Architecture, graduation studio methods & analysis: Positions in Practice, Valparaiso. Student: Sába Schramkó.

Stories for Architectural Imagination

Our contribution thus advocates a turn to stories and language in the field of architectural teaching, so as to stimulate future architects’ creative imagination. In our account of imagination as a necessary field of emphasis for architectural education, we have focused on four modes of engaging with stories: reading, telling, writing, and making. Despite the fact that for the needs of this contribution we have discussed them separately, we do not necessarily advocate for a clear-cut separation between these actions in a pedagogical context, nor for their engagement in this specific order. There are definitely interconnections among these acts, and overlaps, which can prove all the more useful for students. The writing of a story may precede its telling if an assignment calls for such an order. The story regarding the making of a structural detail can be the very beginning of an entire studio, that can later lead into the reading and telling of other stories. And the reading of literary texts does not always have to be situated at the beginning of a site analysis or a design studio. The exercises we suggested in this contribution can work in tandem with other site explorations or inform the architectural design process at a different moment within the educational trajectory of a seminar or studio context.

By including modes of reading, telling, writing, and making stories in architectural education, we aim to open students’ analytical capacities to include a much needed sensitivity towards the meanings, atmospheres, and settings already embedded in place, while encouraging imaginative projections of alternative futures. Through the use of literary modes of working, architectural education can thus enhance both the analytical and projective capacities of students. Their analysis of site-specific social, material, and atmospheric conditions can be informed by the reading of stories for places, as well as by the reading of actual language and texts inscribed in places. By training students to engage with the multiple voices of local communities as a valuable source of information on the social aspects of a place, they will develop an empathetic approach towards the stories of different communities, the perspectives of multiple users, and the habits of various actors that an architectural design may address. The mode of “telling” will also occur through the students’ own storytelling during the design process—the telling of stories from multiple perspectives will make students more aware of the social impact of their design decisions. Through engaging with writing, imaginative architectural thinking will be further developed as an act of connecting space and time by the use of writing techniques that take into account temporality. Such projective imagination may include schemes for projecting future scenarios or future worlds as innovative answers to current societal needs and demands, as well as schemes—deriving from more personal and intimate spatial desires—that aim to shed a new light and reinterpret established spatial conditions. The projective capacity that writing stories cultivates can also be employed creatively in raising awareness of architectural and urban issues through performative writing in space. Lastly, stories can serve as a model for explorations of processes of making, in which details are not seen as merely rational composites, but rather as biographies of making in which materials, tools, people, and time play their parts. Exercises in developing poetic receptivity to details and atmospheres can be used as a way to take into account the relationship between the micro scale of the detail and the macro scale of cities and landscapes.

In our approach, the engagement of stories in architectural education in the different modalities we have discussed contributes to building a concrete foundation for expanding students’ creative spatial imagination. With imagination being at the very center of the architectural process, stories and language can bring forward imaginative possibilities that have long been left on the margins of architectural curricula and pedagogical environments. By encouraging students to engage with the reading, telling, writing, and making of stories throughout their studies, we educate a generation of future architects to be strongly connected with the poetic and multivocal nature of the world around them. We prepare them to look for the unexpected, mesmerizing, and imaginative elements that the world stories contain, and that their own stories and architectures can add to this world.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Klaske Havik

Klaske Havik is professor of methods of analysis and imagination at TU Delft. Her work relates architectural and urban questions, such as the use, experience, and imagination of place, to literary language. Her publications include Urban Literacy. Reading and Writing Architecture (2014), and the edited volume Writingplace, Investigations in Architecture and Literature (2016). For architecture journal OASE she edited, among other issues, OASE 98, “Narrating Urban Landscapes,” OASE 91, “Building Atmosphere” (2013), and OASE 70, “Architecture and Literature” (2007). She initiated the Writingplace Journal for Architecture and Literature in 2018. Havik is currently leading the EU COST Research Network “Writing Urban Places.”

Angeliki Sioli

Angeliki Sioli is an assistant professor of architecture at TU Delft. She is a registered architect and holds a Ph.D. in the history and theory of architecture from McGill University. Her work on architecture, literature, and pedagogy has been published in a number of books and presented at numerous conferences. She has edited the collected volume Reading Architecture: Literary Imagination and Architectural Experience (Routledge, 2018). Before joining TU Delft, Sioli taught both undergraduate and graduate courses at McGill University in Montreal, Tec de Monterrey in Mexico, and Louisiana State University in the United States.

Notes

1 Some exceptions include the recent online course The Architectural Imagination of K. Michael Hays at GSD, Harvard, https://online-learning.harvard.edu/course/architectural-imagination?delta=3. See also Lisa Landrum, “Varieties of Architectural Imagination,” in Warehouse 25, ed. Alena Rieger and Ally Pereira-Edwards (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 2016), 71–83, and Marco Frascari, “An architectural good-life can be built, explained and taught only through storytelling,” in Reading Architecture and Culture: Researching Buildings, Spaces and Documents, ed. Adam Sharr (New York: Routledge, 2012), 224–233.

2 Before the birth of scientific cartography in the seventeenth century, maps used to combine pictographic and topographic elements with short narratives that would describe, through language, the elements represented. See Edward S. Casey, Earth-Mapping: Artists Reshaping Landscape (Minneapolis, MI: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), xiii.

3 Richard Kearney, “Paul Ricoeur and the Hermeneutic Imagination,” in The Narrative Path, The Later Works of Paul Ricoeur, ed. T. Peter Kemp and David Rasmussen (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 1989), 1.

4 Kearney, “Paul Ricoeur.” See also Edward S. Casey, Imagining: a Phenomenological Study (Bloomington/London: Indiana University Press, 1976).

5 Paul Ricoeur, “The Function of Fiction in Shaping Reality,” Man and World 12, no. 2 (1979): 127.

6 Paul Ricoeur, Hermeneutics and the Human Sciences (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 181.

7 Ricoeur, Hermeneutics, 3, 2.

8 Ricoeur, Hermeneutics.

9 Elaine Scarry, Dreaming by the Book, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 76.

10 We do not have the space in this contribution to elaborate on these and many other literary sources that describe urban places, but refer the reader to a number of recent anthologies that have explored this relation between city and literature: Sarah Edwards and Jonathan Charley, Writing the Modern City. Literature, Architecture, Modernity (London: Routledge, 2012); Pedro Gadanho and Susana Oliveira, eds., Once Upon a Place. Architecture and Fiction (Lisbon: Caleidoscopio, 2013); Jonathan Charley, ed., Research Companion to Architecture, Literature and the City (London: Routledge, 2018), Angeliki Sioli and Yoonchun Jung, eds. Reading Architecture. Literary Imagination and Architectural Experience (London/New York: Routledge, 2018); and Martin Kindermann and Rebekka Rohleder, eds., Exploring the Spatiality of the City Across Cultural Texts. Narrating Spaces, Reading Urbanity (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

11 A recent study on Lispector’s account of Brasilia is Kris Pint, “Brasilia is Blood on a Tennis Court,” in Writingplace #4: Choices and Strategies of Spatial Imagination (Rotterdam: nai010, 2020), 90–109.

12 Gala Maria Follaco speaks of ‘sensing’ the city of Tokyo through the work of Kafu, in “Private Topographies: Visions of Tokyo in Modern Japanese Literature,” in Exploring the Spatiality of the City Across Cultural Texts. Narrating Spaces, Reading Urbanity, ed. Martin Kindermann and Rebekka Rohleder (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), 301–320.

13 A few relevant examples could be: Haruki Murakami’s South of the Border or West of the Sun (2000) and After Dark (2007) for an understanding of Tokyo’s intense urban life; Juan Gabriel Vasquez’s The Sound of Things Falling (2013) for a glance into Bogotá’s underground city realities; Gonzalo Celorio’s And Let the Earth Tremble at its Centers (2009) for a sonorous and multilayered reading of Mexico City; and Nikolski (2008) by Nicolas Dickner for a deep dive into Montreal’s urbanity. Many books from the Western canon are also rich sources of historical and urban knowledge on various metropolises, like Andrei Bely’s Petersburg (1913) for Saint Petersburg, James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) for Dublin, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) for London, and Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer (1925) for New York.

14 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 105.

15 For a detailed account of this assignment and its philosophical underpinning, see Angeliki Sioli, “The Word-Collector: Urban Narratives and ‘Word-Designs,’” in Writingplace: Literary Methods in Architectural Education, no 1 (2018): 90–100.

16 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, 78.

17 Caroline Dionne, “We Build Spaces with Words: Spatial Agency, Recognition and Narrative,” in Reading Architecture: Literary Imagination and Architectural Experience, ed. Angeliki Sioli and Yoonchun Jung (New York: Routledge, 2018), 160.

18 Valentina Bencic and Yoana Yordanova, as part of the TU Delft graduation studio methods & analysis: Positions in Practice, Bogotá.

19 Georges Perec, Species of Spaces (1974; London: Penguin Classics 2008), 79.

20 Marx W. Wartofsky, “Telos and Technique: Models as Modes of Action,” in Models: Representation and the Scientific Understanding, ed. Robert S. Cohen and Marx W. Wartofsky (Dordrecht: Holland; Boston: U.S.A; London: England: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1979), 143.

21 Wartofsky, “Telos and Technique,” 145.

22 Scarry, Dreaming by the Book, 7.

23 Grassi, Ernesto, Rhetoric as Philosophy: The Humanist Tradition (Carbondale and Edwardsville, Ill: Southern Illinois University Press, 1980), 76.

24 Martin Heidegger as quoted in Richard E. Palmer, Hermeneutics, Interpretation Theory in Schleiermacher, Dilthey, Heidegger, and Gadamer (Evanston; IL: Northwest University Press, 1969), 139.

25 Richard Sennet, The Craftsman (London: Penguin Press, 2009), 119.

26 A.S. Bessa, “Vers: Une Architecture,” in Architectures of Poetry, ed. María Eugenia Díaz Sánchez and Craig Douglas Dworkin (Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi, 2004), 41–51.

27 Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, (1958; Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), 199.

28 Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, 201.

29 Research and design studio Transdisciplinary Encounters, Methods of Analysis and Imagination, Department of Architecture, TU Delft, Spring 2020. A reflection on this course on craft and material culture was presented by course instructors Jorge Mejía Hernández and Eric Ferreira Crevels, as “Uno y Varios Detalles: Las contingencias de la construcción como evidencia empírica para la proyectación arquitectónica” at the VIII Simposio De Investigación En Arquitectura. Proyecto - Tradición - Procedimientos, Bogotá, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, December 2–4, 2020.

30 Poem by student Sába Schramko.

31 Poem by student Sába Schramko.