Abstract

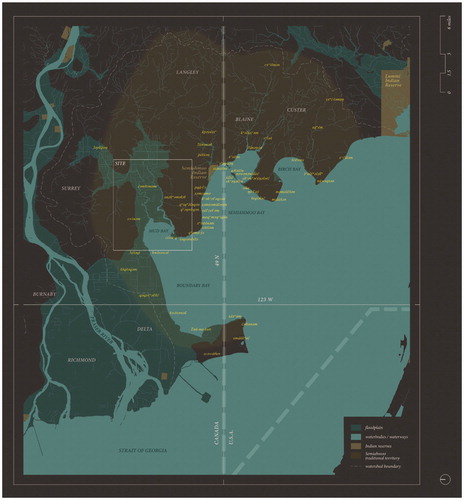

This paper is a series of tales of sea level rise on the coastal floodplain of Surrey, British Columbia. It begins with the Indigenous tales of the Great Flood that inform Coast Salish collective identity. This collective identity becomes permanently altered as illustrated in tales about how colonial tools of maps and surveys dispossessed Indigenous peoples of their lands while inflicting ecosystem damage. The paper concludes with tales that contemplate an expanded definition to “land reclamation”—one that provides a framework for flood adaptation and ecosystem restoration, while making space for a decolonized future urbanism on the floodplain.

Setting the Scene

15,000 years ago, the region which would become Coast Salish territories was under a 1600-meter-deep section of the Cordilleran ice sheet at its southwestern corner. The 2,500 years that followed saw cycles of glacial advance and retreat that accumulated deposits, which emerged as islands as sea levels began to drop to about 160 meters above current levels.Footnote1 Rivers formed as sculpted valleys filled with glacial meltwaters. The Fraser River was born in this way approximately 11,000 years ago. Indigenous peoples began settling along this river in the Fraser Valley and Fraser Canyon, thus taking on the name Stó:lō, which means “people of the river.”Footnote2 The Fraser River is one of many watercourses within the drainage basin that empties into the Salish Sea—composed of the Strait of Georgia, Puget Sound, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and other smaller water bodies; its watershed approximates Coast Salish territories. Following periods of fluctuations from ice melt and post-glacial rebound, sea level finally stabilizes within five meters of the current datum around 5,500 to 5,000 years ago, allowing salmon runs to flourish in abundance.Footnote3

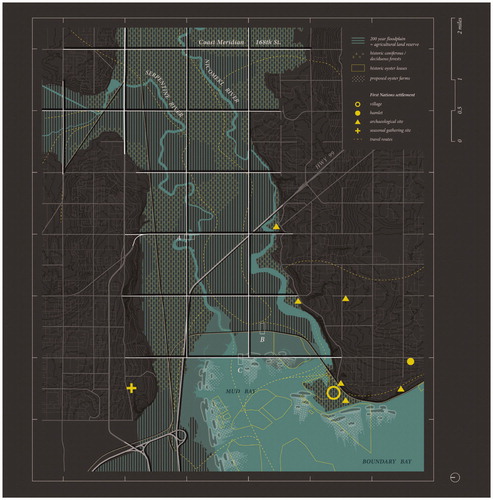

The traditional territory of the Semiahmoo people, a Coast Salish subgroup, coincided with the watersheds that drained into Boundary Bay, Mud Bay, Semiahmoo Bay, and Birch Bay, but their kin connections and past subsistence patterns extend beyond this area and across colonial boundaries. In the past, the Semiahmoo would gaff salmon in the Dakota and California creeks in autumn, and hunt for bear and beaver at the heads of the Serpentine and Nicomekl rivers in the winter. Come spring, they would hunt for deer and elk near Lake Terrell and travel as far as Waldron Island to harvest camas. They would return north in the summer to share reef netting grounds near present-day Point Roberts and harvest shellfish in Boundary Bay.Footnote4 Today, the Semiahmoo Indian Reserve occupies 319 acres of land drawn to the south of the city of Surrey in British Columbia, just north of the Canada-United States border.Footnote5 Surrey is located on the unceded traditional territories of the Semiahmoo, Katzie, Kwikwetlem, Kwantlen, Qayqayt, and Tsawwassen First Nations. One-third of its municipal lands is reserved for agricultural use, which coincides closely with the coastal floodplain.Footnote6 This area is vulnerable to inundation from the combined effects of climate-change-induced sea level rise and increased rainfall expected from more frequent and intense storm events. Reports have shown that 1.2 meters of sea level rise from waters entering from Boundary Bay and Mud Bay is expected in 80 years, with 1.63 meters forecasted in a high emissions scenario.Footnote7 And as a river delta formed by deposited sediments, it also needs to contend with the added risk of soil liquefaction, being in a seismic zone.

Tales of a Great Flood

Long ago, my grandfather told me this story of how, long, long before that, his great grandfather had spoken of the years before his time when the people were nearly all drowned in a big, big water which flooded all this country. It rained such a big rain that time. The people didn’t care at first because they had seen big rains before. But this time the rivers and the creeks could not take it away, so the water rose up and up until it reached our houses. We took our dried salmon and berries and moved to the mountain, but the water kept following us. We climbed higher and higher up the mountain but still the water kept coming after us.

So, the greatest leaders called a council of the warriors and doctors on the highest hill behind our village. The council could see that if the water kept coming as it had, this hill wouldn’t be dry very long. Everything kept drifting past, even the great cedar planks that we used to build the walls of the smoke houses. The leaders ordered the young men to swim out and gather all the cedar planks so that they could make big rafts. Then everyone worked hard to make two rafts from the house boards and piled all their provisions on it. Then they got on themselves.

The water kept coming, over the top of the place where they were on the highest hill behind the village. So, we drifted around. Then a big wind came up, washing a lot of the provisions away. Now for food we had to catch some of the animals that swam to the raft, looking to be saved. The two rafts got separated then, one of them drifted far until the leader saw a peak still out of the water, and then wind blew the raft straight to that peak.Footnote8

The survivors of the flood escaped to the mountains, seeking shelter in a cave and subsisted off of dried salmon. Once the water receded, the people made their return.

Everything was changed. Some of the creeks that had been there were no more, and there were new lakes and creeks in different places. The people were pretty weak before the salmon came again but that year there was lots of salmon and the people were saved.Footnote9

This is an oral history recounting of the Great Flood that devastated the homes of the Stó:lō people generations ago as told by First NationsFootnote10 elder Harry Uslick. It was translated from Halkomelem to English by his wife to anthropologist and folklorist Norman Lerman. While this story of the Stó:lō represents the Fraser Valley region of southwest British Columbia, there are many versions of the story of the Great Flood connecting communities from all lands touching the Salish Sea (the combined waters of Puget Sound, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and the Strait of Georgia), which corroborate it as an actual historic event.

Chief Harley Chappell of the Semiahmoo First Nation also tells a version of this story of the Great Flood as experienced by the Lhaq’temish—“the survivors of the flood”—the Indigenous peoples in present-day southwest British Columbia and northwest Washington.Footnote11 Long ago, an elder received a premonition of a great flood and ordered two canoes to be tied together, filled with supplies, and boarded with children. Tethered to the ground, the canoes rose with the rising waters that washed away the villages. After the waters receded and the canoes returned to the ground, the survivors dispersed to different locations, guided by their preference for specific food sources. A wise survivor sent for those who departed to return for a gathering. At this gathering they assigned the suffix “-mish” to the end of their names to signify who they were and where they came from. We see this in the names of such Indigenous groups as the Samish, Swinomish, Skykomish, Snohomish, and Stillaguamish. The Semiahmoo and Lummi, however, never acquired this suffix because they remained where the canoes had landed.

For these Indigenous peoples, oral histories are part of a tapestry of collective memory that involves multiple retellings. Unlike written records, which are static products of singular, authoritative voices, oral histories can be seen as living records that carry messages that often need to be validated by the group. Tellers are expected to share how they knew the story (for example, in the Tale of the Great Flood as told by Harry Uslick, it starts with “my grandfather told me of how…”), referencing an elder in a manner of “oral footnoting.”Footnote12 The naming of the source(s) holds these respected knowledge keepers, and those who came before them, accountable for the veracity of the stories. Nuances may emerge with each retelling as the purpose of these narratives is not necessarily to provide a detailed, archival account of past events. Rather, the variations that develop in the act of telling and retelling these stories engage in the historiographical discourse as signifiers of evolving worldviews over the generations and help shape Indigenous collective identity.Footnote13 Collective identity is not stagnant; it is constantly being formed and reformed. Therefore, oral narratives are not stories stuck in a distant past and thus immutable. Instead, they are living records of momentous events and collections of traditional knowledge that transform and adapt with each successive generation.

The stories of the Great Flood can be used to understand the ethnogenesis of the Coast Salish peoples, and their ancestral ties across vast geographical distances. The story of displacement is not meant to be segregationist or imply that those who floated away or relocated are lost and need to be repatriated. Instead, it reinforces the shared and intermingled ancestry among seemingly disparate groups and unites groups with a collective identity. It also represents the complex regional network of relations of the Coast Salish, formed around the term siyá:ye, which is Halkomelem for “friend or relative.” The term describes kinship outside of bloodline and marital unions and is used instead to help form and validate political alliances within Western constructs.

The collective identity of the Coast Salish was not bound to territory defined by winter residences as markers of settlement; their social structures were formed by seasonal migrations to various sites across the region to share local resources. With fluctuations of scarcity and abundance of food from year to year, it was important to forge alliances across ecological niches. Before modern technology, the Indigenous peoples were reliant on the climatic and geographical variations of each niche for the hunting, harvesting, processing, and storage of local foods. Alliances enabled other groups to be brought in to assist with these activities during periods requiring concentrated labor. Coast Salish collective identity was, in this way, an expression of Indigenous socioeconomic life centered around cycles of seasonal migrations to regionally dispersed resources, as opposed to a nomadic life without fixed habitation.

From the Coast Salish stories of the Great Flood, we also learn that this region is subject to cycles of inundation. Archaeological evidence and other historic accounts also attest to a number of large-scale floods that these stories could describe. One such event happened after the last glaciation approximately 11,000 years ago.Footnote14 Geologists have recently discovered that the failure of an ice dam along the Fraser River would have released a massive volume of water from a glacial lake downstream, flooding lowland areas. The great flood has also been attributed to the high-magnitude Cascadia earthquake of 1700 that caused a catastrophic tsunami and land subsidence along the coast of one to two meters.Footnote15 Whether the story of a great flood as told by different groups in the region is specific to one event or applicable to multiple events, it demonstrates how the First Nations people responded to the landscape they occupied and provides lessons in disaster preparation and managed retreat.

Tales of Permanence

The Indians have really no right to the lands they claim, nor are they of any actual value or utility to them… It seems to me, therefore, both just and politic that they should be confirmed in the possession of such extents of lands only as are sufficient for their probable requirements for purposes of cultivation and pasturage, and that the remainder of the land now shut up in these reserves should be thrown open to pre-emption.Footnote16

The British colonizers justified their territorial claims through their commitment to the framework of The Doctrine of Discovery and Manifest Destiny. They believed it their destiny to occupy the land, and their mission to evangelize their way of life by bringing European culture and religion to the “uncivilized savages.”Footnote17 The philosophies of John Locke guided colonial policies around property rights at this time: ownership was to be earned through investing labor in cultivating the soil. If land was not improved upon by agriculture and tilled for production, then it would be terra nullius and thus free for appropriation by settlers. The adoption of this European agriculturalist model held up cultivation as the ideal use of land, and commitment to improve the land was the prerequisite for settlers to acquire acreage through preemption. By framing the Indigenous peoples as uncivilized, “natural” people, the policies devised by the colonial authorities forced Indigenous peoples to transform themselves from hunter-gatherers into farmers to prove they were entitled to land that was once theirs. The Indian Land Policy reflected this as it refused to recognize Aboriginal title to land and assigned small allocations of land based on European standards of what was deserved. White ownership of land, as the Indigenous peoples learned, was very different from their own relationship with land. White settlers would fence their properties and advance legal action onto trespassers. The Indigenous peoples did not benefit from the same protections of the law though, as demonstrated in an incident where their lands were invaded by white settlers’ cattle without penalty.Footnote18 Adopting European agrarian ideals also meant that the Indigenous peoples had to abandon their traditional food practices and the diverse social and economic uses of their ancestral land for a new mode of subsistence.

The Indigenous peoples were seen as anachronistic impediments to progress, as evidenced in the decree from Britain to the Governor of the Colony of British Columbia James Douglas in 1859: it demanded that the Indian policies were to “in no way interfere with the progress of the white settlers.”Footnote19 To secure title over the sovereign Crown Lands, the Indian Policy sought to “[curtail] Aboriginal mobility while geographically restricting indigenous activities.”Footnote20 By ending the traditional seasonal migration to food sources, this had the direct impact of erasing the collective identity of the Stó:lō people. This colonial mechanism delegitimized the Indigenous way of using their land, controlled their movement, and disaggregated collective political consciousness. The colonizers asserted that the alleged nomadism of the Indigenous peoples inhibited colonial land development, disregarding the fact that there were clearly settlements that the Indigenous peoples would return to following seasonal migrations. Prior to European arrival, Indigenous peoples also had distinct territories. Unlike Western notions of territory, these boundaries were fluid and unmarked, and people were free to roam from one territory to another. With the Indian Policy formulated by the summer of 1859, the Royal Engineers set out to demarcate Indian reserves and make way for settler land. These reserves were initially defined by existing village sites, burial grounds, and cultivated potato patches. But as tensions escalated between the Stó:lō and the settlers, the reserves were expanded to include “provisioning grounds,” such as fishing sites. And for a little while, the Stó:lō were even permitted to preempt land like their white counterparts. However, this policy allowing Natives to preempt land came with many conditions,Footnote21 including some proficiency in the English language to fill out paperwork, as well as a basic knowledge of Cartesian geometry to map out lot extents.Footnote22

Figure 1. Remnants of piles and scatterings of shells from the historic oyster farm along the coast, with the railway line cutting across the horizon. (Photograph by author.)

As part of the reserve creation process, an 1863 census of the Stó:lō peoples ordered by Douglas effectively divided communities and simplified a complex network of relationships that was fostered by free movement between settlements. This registry, which eventually evolved into band membership lists, permanently altered Indigenous identity and belonging. It assigned Indigenous peoples to specific reserves and restricted mobility for the purpose of maintaining land-to-person ratios. Land reserve sizes were assessed by acreage per resident to determine what would be sufficient for communities to “make adequate use of the land”Footnote23 in colonial terms. Confined to their own designated parcels of land, temporary relocation of members to another reserve would put a strain on the already limited resources for those living there. Once registered, an Indigenous person was prohibited from accessing and using another reserve because colonial law dictated that they had no rights there. This permanent parceling of land severed extended family ties to hereditarily-owned properties and discouraged the seasonal relocation of members for opportunities across the diverse range of resource sites.

For the most part, Douglas was remembered as diplomatic in his handling of Indian affairsFootnote24 and would respectfully refer to the Indigenous peoples as “Native Indians” in his correspondences. While faithful to the empire, he also saw it as his mission to defend Indian rights and was well regarded by the Indigenous peoples for his efforts. His approach was likely carried down from his previous role as chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), where it was company policy to “treat the Indians as fairly as possible and interfere with them only when they molested a white man.”Footnote25 HBC held quasi-governmental authority over Vancouver Island when Douglas was chief factor, as it had already established the foundations for a colony there. This meant Douglas was able to use goods from the company as bargaining tools with the Natives in reserve negotiations, a privilege he relinquished when he left his HBC position. Purchasing so-called Native title was made more difficult as Douglas encountered trouble securing funds from the Crown, which saw this as a purely colonial matter.

Douglas’s approach to Indian land ownership also aligned with British views that the Indigenous peoples have proprietary rights to the land even though the Crown held absolute title, and those rights could only be extinguished by way of treaties and negotiated compensation. For instance, in April 1863, Douglas observed an inappropriate allocation of properties for a reserve at Coquitlam, reprimanded his Lands and Works Department for not providing sufficient lands for subsistence, and directed that the surveys be redrawn to the satisfaction of the Indigenous peoples. The idea was if the Indigenous peoples were able to support themselves on those lands, then there would be no need to seek further handouts from the government. Further to this, Douglas believed that once reserves were laid out, they were not to be reduced nor encroached upon.

The year 1864 was a turning point in the administration of the Colony of British Columbia as Douglas retired as governor and was replaced by Frederick Seymour. Seymour passed on the management of Indian Affairs to the newly appointed chief commissioner of lands and works, Joseph Trutch, whose actions ran contrary to the established policies. Trained as an engineer, Trutch had arrived in British Columbia five years prior, following the gold rush from California to the Fraser River. As a contract surveyor supplementing the work of the Royal Engineers, Trutch had surveyed the Coast Meridian in 1859, the axis (which cuts through Surrey) that became the benchmark for subsequent surveys in the Fraser Valley. A capitalist at heart, Trutch was interested in amassing wealth through infrastructure constructionFootnote26 and establishing townships and farmland, as evidenced in his correspondences with his family.Footnote27 This meant relieving the Indigenous peoples of their lands for colonial settlement, as he saw this as the most efficient road to progress for people he regarded as “savages.”Footnote28

Before his retirement, Douglas had directed William Cox (a gold commissioner and magistrate) and William McColl (a former Royal Engineer) to survey new Indian reserves in the Okanagan and Lower Fraser River respectively. Completed in May 1864, McColl’s map is highly disputed to this day as it had officially documented much larger reserve lands. With Douglas’s departure and McColl’s passing in 1864, their successors took this opportunity to reverse their predecessors’ efforts to provide fair distribution of land. Trutch discredited McColl’s work by alleging that the lone surveyor had deviated from Douglas’s instructions and even questioned the validity of these instructions as they came from an aging governor. Trutch falsified the record by stating in a report that “there [were] no written directions”Footnote29 from Douglas even though there were plenty of letters documenting Douglas’s direction to lay reserves according to the Indians’ wishes.Footnote30 Similarly, Trutch condemned Cox’s survey of the interior reserves as a misrepresentation of Douglas’s instructions, even though there is evidence proving that Douglas had reviewed the plots and was satisfied with their allocation. Trutch even attempted to use gold commissioner Phillip Nind’s claim that “these Indians do nothing more with their land than cultivate a few patches of potatoes here and there; they are a vagrant people who live by fishing, hunting, and bartering skins”Footnote31 to corroborate his claim that the reserve lands were “entirely disproportionate to the numbers or the requirements of the Indian Tribes.”Footnote32 Trutch furthered his accusations, claiming that the Indians were moving survey stakes after they had been laid out. By arguing that the original tracts of land were provided at an unreasonable extent, he was able to resurvey without providing any compensation to the Indians. He managed to reduce the mapped reserves by 92 percent on account of inconsistent ratios, thus opening up 40,000 additional acres for preemption by white settlers. This left the Stó:lō with at most 10 acres per family plus some additional land for grazing for those who owned cattle or horses. This paled in comparison to the 160 acres available by land grant to white homesteaders, with an additional 480 acres available for purchase. Upset with this injustice, 3,000 Indigenous peoples from the Fraser Valley gathered on Queen Victoria’s birthday in 1864 to protest the drastic reserve reductions ().

Figure 2. Coast Salish peoples gather in protest of the land reserve reductions on Queen Victoria’s birthday in 1864. (Charles Gentile Early British Columbia Photos, Uno Langmann Family Collection of British Columbia Photographs.)

The Stó:lō became fully reliant on their land reserve allocations by 1866, when the colonial government issued a land ordinance to repeal its earlier policy allowing Natives to freely preempt private land off reserve.Footnote33 Instead, through forced assimilation, a Native manFootnote34 had to deny his Indian identity and prove his loyalty as a “brown-skinned British subject” in order to claim private land.Footnote35 By the time British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871, Trutch was promoted to Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia where he was even better positioned to uphold his policies, even though they were diametrically opposed to the views of the federal government. The minister of the interior saw Trutch as responsible for the discontent of the Indians: “the people of Canada generally would not sustain a policy towards the Indians of that Province which is, in my opinion, not only unwise and unjust, but also illegal.”Footnote36 Unfortunately, by the time Trutch retired from his post in 1876, the federal government was unable to reverse British Columbia’s Indian policies. The government realized that the Indians were now apprised of the value of their land and it would be too costly to extinguish Indian title after so many years. Doing so would also risk introducing further tensions with white settlers who were already upset over unrelated railway disputes. Unlike other parts of Canada where the issues of Indian land title are formalized in treaties, land policies in British Columbia have been inconsistent and Aboriginal land title claims remain unresolved.

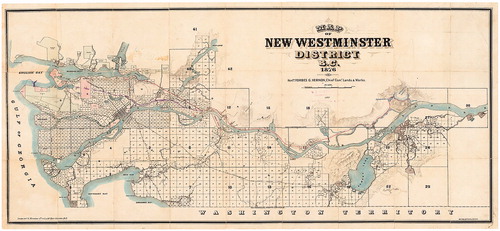

Apart from being used to prepare land for white settlers, surveying and mapping were also means for the British colony to fortify their claim to territory in western Canada. This was motivated by the threat of the United States’ parallel expansion and to control the influx of prospectors to the Fraser Canyon in search of gold. The Royal Engineers were dispatched to British Columbia in 1858 to “conquer nature…so that all nations will gaze on gardens and cornfields” and to carve a cadaster “from the wilderness.”Footnote37 The survey process provided clarity to preemption, but also bound the Natives to their reserve lands within an invisible sea of gridded property lines made manifest, initially, by survey posts and ephemeral clearings through the forests. These markings of civilization on terra incognita were used to establish the six-mile square blocks of the township and range system of the Dominion Land Survey (). Based on meridians centered on Greenwich, the grid had provided legal descriptions across the prairie provinces and extended to British Columbia along the Railway Belt. The spatial logic and mathematical precision of this international standard helped legitimize Britain’s sovereign claim to land. Its Cartesian rationality was meant to be indisputable, masking political agendas behind a facade of supposed scientific objectivity and authority. The blocks of the township and range system easily subdivided into quarter sections of 160 acres, which were equitably granted to white homesteaders willing to make improvements to the land. The forest clearings that suggested boundary lines eventually materialized into permanent infrastructure connecting the properties.

Figure 3. Map of New Westminster District, B.C., 1876. (Map by the British Columbia Government Department of Land and Works, City of Vancouver Archives, AM1594-: Map 2.)

The equitable distribution of sections of land amongst white settlers was not afforded to the Natives. Instead, the Natives were dispossessed through the hegemonic colonial conceptualizations of territory and property, using maps as a tool of dominance and segregation. These politically motivated abstractions of space, as Bjørn Sletto describes, “shaped by statist requirements for spatial fixity, precision, and cartographic ‘accuracy,’ inevitably effect violence to the fluid, shifting, and socially contingent nature of lived, indigenous spatial relationships.”Footnote38 The abstractions applied in map production erased, severed, and redefined the complex relationships of Indigenous peoples with each other, the land, and even the sea. Western maps’ reliance on finite edges as a means of representation reinforces boundedness and privileges unambiguous spatial orders. They create and perpetuate divides between Indigenous communities. For instance, the 1846 Treaty of Oregon that extended the 49th parallel border to the Pacific coast bisected Semiahmoo territory, causing some members to join the Lummi tribe south of the border in the United States (). This cartographic construct also cut through the Indigenous dining table that is Boundary Bay,Footnote39 which had been relied on for shellfish harvesting for generations. In the past century, nonpoint source pollution from surface runoff and unregulated discharge within the catchment area has deteriorated water quality, rendering shellfish unsafe to consume.Footnote40 The Semiahmoo in British Columbia have been prohibited from harvesting shellfish since 1962 due to blanket closures, while clean-up efforts and routine testing in Washington have enabled conditional access for the Lummi since 2004.Footnote41 Disparities in ecosystem management across the border and asymmetrical access to historically shared resources have introduced rifts and countered efforts to reunify Coast Salish communities disrupted by colonial mechanisms.

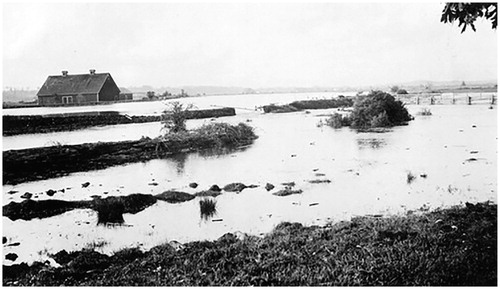

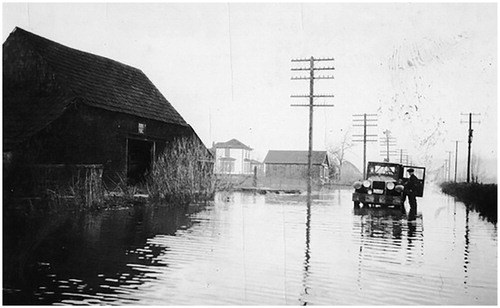

Fixed boundaries have also neglected natural phenomena, like flooding, which is not new to this region, as demonstrated through oral histories and scientific evidence. However, the patterns of development dictated by the colonial maps and surveys have turned this natural phenomenon into a risk. Early European settlers saw the coastal wetlands as “wasteland” that inhibited growth and proceeded to drain them with ditches and pumps for agricultural use. Flood risks were mitigated with tidal gates and dikes that reinforced and fixed the coastline. Even with these hard engineering measures in place, the city of Surrey has experienced a number of major flood events in the past century. Dikes were overtopped in January of 1935 due to heavy snowpack that interfered with stormwater infiltration after record rainfalls and due to river ice that blocked floodgates. Overflowing brackish waters from the flooded Serpentine and Nicomekl Rivers in December of 1951 led to salinity damage to soils, which impacted agricultural production for years to follow ().Footnote42 This event was partly caused by the accumulation of sediment behind floodgates, which was eventually mitigated in 1957 with the purchase of a drag line to dredge the riverbed. Even still, two major flood events occurred on the rivers again in January of 1968 and December of 1979 (). Several years later in December of 1982, a flood came from the sea when a coincident windstorm and high tide overtopped the dikes. Since then, the city had upgraded its dikes in 1988 and formulated strategies and implemented measures for the improvement of flood management in 1994 and 1997. Confidence in the ability of hard engineered solutions to combat natural processes persists despite these past failures.

Figure 7. Flood resulting from dike breach at Serpentine River, 14 February 1952. (Surrey Archives SM.224B.)

Figure 8. Flood along Pacific Highway near 40th Avenue, 25 January 1968. (Surrey Archives SA1992.036.11409.)

These are some of the consequences of the colonial maps and surveys, which, at their inception, were relied upon as tools of control for Britain to choreograph actions from a distance. However, their manipulation under Trutch’s supervision slipped under the radar and has resulted in unresolved territorial disputes. In fact, the latter part of the nineteenth century was regarded as an era of “distant oversight” in British Columbia—referring both to its remoteness from the ivory tower of London and its concomitant neglect.Footnote43 As the fight for stolen land continues, oral narratives have been accepted as historical evidence in court proceedings on Aboriginal land claims. In the seminal Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, stories, songs, dances, and speeches were accepted for consideration as proof of Aboriginal occupancy.Footnote44 Chief Justice Lamer determined that “notwithstanding the challenges created by the use of oral histories as proof of historical facts, the laws of evidence must be adapted in order that this type of evidence can be accommodated and placed on an equal footing with the types of historical evidence that courts are familiar with, which largely consists of historical documents.”Footnote45 These intracultural oral traditions used to inform personal and collective identities have also come to serve another purpose involving an external, foreign audience—for legal cases, land use and occupancy studies, and as education tools.

Non-Indigenous architects and designers serving as accomplices must not only work in partnership with Indigenous peoples in participatory processes, but we must also challenge colonial/Western constructs, contexts, and conventions of design. The embrace of oral traditions in Delgamuukw v. British Columbia has proven that the state is amenable to other ways of knowing, which could help expand the horizons of how Indigenous space is conceived and represented. By shedding light on past corruption, it helps inform ways to disentangle the systemic forces that have dictated the evolution of our cities. The scale of infrastructure works being planned compels a radical shift in thinking that does not require a reliance on hard engineered solutions. Elevating the roadways and their associated infrastructure would be symbolic of an emancipation from a non-Indigenous ideology and makes way for soft infrastructure and coastal management based on Indigenous values. Peter Walker and Pauline Peters remind us that “the job of mapping should not end with the drawing of boundaries” and ask that when “social scientists assist social groups to draw maps, it is crucial that they also document and communicate what these boundaries mean for local people.”Footnote46 Extending this reminder to architects and designers, we should think critically about how, through maps and surveys, we become complicit in affecting marginalized communities through the perpetuation of boundaries, and how we can help dismantle them where appropriate. We should also be reminded that ecological collapse, species stress, sea level rise, storm events, or tsunamis from the Next Big OneFootnote47 are all phenomena that do not respect boundaries, and so they force us to think about what we do when these boundaries are erased.

Tales of Reclaiming

To do this, how might we shift away from the colonial lens of gridded cadastral mapping and its rigid but futile attempts to control nature? We might draw upon Indigenous concepts of land, which Glen Sean Coulthard describes as a “system of reciprocal relations and obligations” that teaches us how to engage with the natural world in “non-dominating and nonexploitative terms.”Footnote48 As the most authoritative reference for climate change globally, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has finally acknowledged the value of Indigenous, local, and traditional knowledge systems and practices, citing “indigenous peoples’ holistic view of community and environment [as] a major resource for adapting to climate change.”Footnote49 The participation of Indigenous voices in promoting ethical land practices that are adaptive to climate change is an example of how Indigenous peoples can exercise their right to “determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources”Footnote50 per Article 32.1 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This includes “the right to the conservation and protection of the environment and the productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources.”Footnote51

To engender mutual benefits from the convergence of climate change adaptation planning and the Indigenous reconciliation discourse, we might begin by examining the term “land reclamation.”

“Land reclamation” is generally understood as the engineering method of draining wetlands for productivity. However, this exposes the colonial preoccupation with grooming land for exploitation and is disconnected from the natural processes of the environment. It compels us to view coastlines not as amphibious blurred edges, but rather as a single continuous, defined boundary held in place by human constructions. Another definition of “land reclamation” implies the creation of artificial landforms, though it seems a misappropriation of the term since “reclaiming” implies that there is territory to be recovered. This definition reinforces colonial desires to extract value and impose sovereignty over land as a fixed entity. Antithetical to the definition of reclaiming land from the sea is perhaps an inverse “land reclamation” that implies reclaiming land by the sea. This is the process where land formed by deltaic deposits resubmerges and becomes reabsorbed back into the sea as sea level rises. “Land reclamation” has also come to mean the restoration of land following disturbances from resource extraction, such as mining or fossil fuel operations. What if we expanded the meaning of “land reclamation” further, so it applies to the combined efforts of socioecological resilience and reconciliation? In this case, it describes the act of deconstructing a system to reclaim land for ecological restoration and traditional land use, and reestablishing environment-based markers (or toponyms) often used in Indigenous stories. By doing so, it begins to open opportunities for Indigenous self-determination, restoration of collective Indigenous identity, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and new climate-adaptive imaginaries.

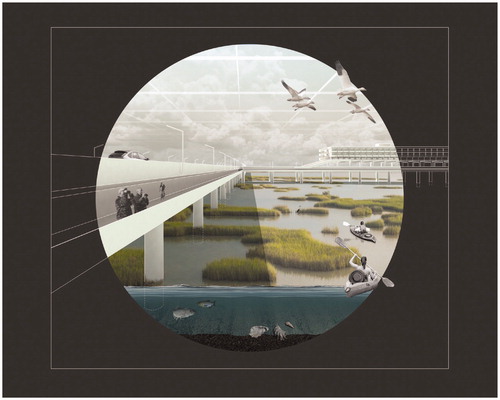

Land reclamation for “othered” populations, and for a resilient future for all, requires staging the ground for new potentials and indeterminacies. What would happen if the superimposed one-square-mile imperial grid of the Dominion Land Survey was decoupled from the ground plane? These property divisions have locked the landscape into a network of roads, utilities, dikes, and ditches at sea level that is susceptible to flooding and liquefaction. Just as fishbone patterns of road construction in the Amazon have facilitated deforestation, the infrastructure grid on this floodplain has subtracted valuable wetlands and caused widespread ecosystem damage and habitat loss. As infrastructure begets development, the farming and industry practices that ensued have introduced pollutants into the waterways. The increase in runoff and overflow of sewage systems that will occur from heavier rain events and snowmelt as temperatures rise will cause further contamination. The selective demolition of destructive and redundant infrastructure on the grid is a material response to the immaterial decoupling of the hegemonic structures of colonial powers. It echoes Keller Easterling’s argument for the subtraction of built form from exhausted land and floodplains, which would in turn “[offer] a redoubled territory for design,”Footnote52 making subtraction a productive technique for orchestrating new territory. In fact, subtraction should be seen as part of an adaptive cycle of gains and losses in the long-term evolution of a city, similar to what C.S. Holling and Lance Gunderson conceptualized for resilient socioecological systems.Footnote53

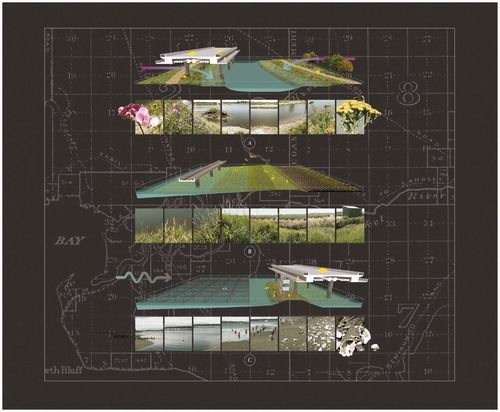

The reconstruction proposal envisioned here would involve elevating infrastructure from the imminent risks of erasure by natural forces ( and ). This produces a mediated space that participates in the gradual undoing of colonial constructs on the ground plane while, at the same time, preserving the organizational function and utility of the grid and how it connects with the rest of the city. The elevated grid maintains its efficiency in connecting communities on higher ground across the floodplain. When inscribed into the ground on the floodplain, the grid interferes with the complex and diverse systems at play and draws us into fixed containers of restrictive development and modes of production. By retreating vertically above projected flood levels, the landscape can then be reconstituted through an embrace of wetness or aqua fluxus.Footnote54 We then finally treat water as the protagonist (instead of land) and, for a moment, relieve ourselves of terrestrial preoccupations. The idea is not to follow a path of regression and return to some idealized past by allowing the entire floodplain to be submerged. Rather, it is to heal the existing landscape using another lens.

Figure 9. Map of the Surrey floodplain with an elevated grid of infrastructure, and past and proposed oyster farms. (Image by the author.)

The proposal has three ecological goals: cleanse the waterways, restore wetlands, and revitalize mudflats ().

The Nicomekl and Serpentine Rivers that discharge into Mud Bay have long been used by the Indigenous peoples as liquid highways, while the white settlers saw the wetlands through which the rivers flowed as “wasteland” that inhibited growth. Lowland forests and brush were cleared so that the wetlands could be drained with ditches and pumps and protected with dikes, in order to “reclaim” them for agricultural use. As development increased and farming practices evolved, the waterways became polluted with sewage, fertilizer, pesticides, motor oil, and industrial discharge.Footnote55 Elevating the infrastructure would serve to control and convey runoff, and planting riparian buffers around the meandering waterways would help filter out contaminants. Wider multizone buffers have the added benefit of promoting biodiversity and accommodating channel migration.

Since 1880, nearly all of the salt marshes, seasonal wet meadows, and bog habitats in the Fraser River delta were converted to cultivated fields, and suburban and industrial developments.Footnote56 Within a century, 70 percent of the original wetlands in the estuary were lost due to drainage and diking.Footnote57 As the natural water boundary advances, protected agricultural fields may be subdivided and gradually converted to wetlands with the support of wetland easements. This may result in savings from discontinued dike maintenance and relief from future dredging.Footnote58 Not only do the wetlands serve as carbon sinks, flood controls, and storm buffers, they also provide sanctuary for diverse wildlife, including migratory birds travelling along the Pacific Flyway. Wetlands provide expanded wintering grounds so that birds, like the snow geese making their annual international sojourn from Siberia, can be directed away from airports, schoolyards, parks, and farmland. Snow geese, for example, have been known to strip these fields of vegetation by uprooting marsh grasses to feed on their rhizomes.

When tidal waters receded, Indigenous people would forage for clams, crabs, and oysters, as evidenced by the shell middens that were recovered on Crescent Beach, dating back more than 5000 years.Footnote59 Capitalizing on this abundant resource, the Crescent Oyster Company was established in 1904 and saw the multicultural collaboration of European- and Indo-Canadian oyster farmers for half a century ( and ), until the operations were closed due to water contamination. Scatterings of oyster and clam shells, and stumps of abandoned wood piles used to support bunkhouses and piers can still be found at the original site near today’s Blackie Spit (). Once the riparian buffers and wetlands have cleansed the contaminated waterways and pollutants have been controlled, this may allow for the ban on bivalve shellfish harvesting in Boundary Bay to be finally lifted. Indigenous people would then be able to engage in their traditional practices of coastal foraging once again, and recreational harvesting may be reopened to the public. Adaptable farmers may find opportunities in reviving a bygone aquacultural industry. Oyster farms can play an important role in mitigating coastal flood hazards as the oyster reef structures are natural breakwaters that attenuate waves and encourage the gradual accumulation of sediment to form strategic soft barriers and flood protection landforms over time.Footnote60

The proposal has, in parallel to these ecological goals, the goal of reintroducing Coast Salish values and setting them in conversation with the colonial spatial history of the past 150 years or so.

The new land reclamation challenges the dominant narrative and Western concepts of territory by exposing the spatial power of mapping conventions. What underlies alternative approaches to cartography—be it Nancy Peluso’s “counter-mapping,” Matthew Sparke’s “contrapuntal cartography,” or Brian Thom’s “radical cartography”Footnote61— is a call for new perspectives on non-dualistic, non-compass-directional representations within a layered, mediated space.

The colonial mapped containers of space reinforce “territorial traps”Footnote62 that condition us into thinking in binaries: inside vs. outside, inclusion vs. exclusion, and by extension, land vs. sea, dry vs. wet. By adjusting the scale of a map, we realize that the coastline is a wide and variable threshold—its own mediated space. To avoid dichotomous relationships and a tendency to “other,” maps should convey a pluralism that enables the convergence of different narratives, cognitions, and understandings of space. Rather than circumscribing space, counter-maps may represent Indigenous life-worlds as a surface of nodes—a constellation of place names and land features—connected by traditional stories, wide-reaching networks, and extended relations. One example of this is Homer Barnett’s map linking summer resource harvesting sites with winter villages in Coast Salish territory, depicted as a meshwork.Footnote63 These connecting lines permeating conventional boundaries not only emphasize Indigenous ideologies around sharing and collaboration, they may also repair kinships across geopolitical divides.

While cardinal directions were important to European explorers and settlers for navigation and for efficient claiming and distribution of land, the Coast Salish people saw their spatial relationship to the environment in different ways. Their understanding of the environment was relative to the flow of travel routes (rivers and seas) and the direction in which salmon return to their spawning grounds. As such, their compass is anchored by four main water systems of the Salish Sea: the Strait of Georgia, Puget Sound, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and the Fraser River.Footnote64 This suggests that Coast Salish maps, should they draw them, would be reoriented according to how the waters move, and eventually drain into the sea. We see examples of this in the two biographical maps produced by K’HHalserten (or William Sepass), the Chief of Skowkale, with the help of A.C. Wells and a local farmer. The maps are oriented with south and east on top relative to the movements of the Fraser River, Chilliwack River, and other tributaries in each. The exaggeration of the watercourses defies the logics of Euclidean space to emphasize how they were experienced by Indigenous peoples as primary transportation routes prior to extensive terrestrial paths. These types of maps represent an intimate experience of place from the ground (or watercourses, in this case), compared to a detached cadastral system valuing abstract space. Landmarks and landscape features are also labelled in both English and a pidgin Halq’eméylem (a dialect of Halkomelem, a Coast Salish language) to suggest a means of adapting to and reconciling the inextricable transformations of an increasingly pluralist society.Footnote65

The proposal visualized here places both landscape stories—the Indigenous and the colonial—in dialogue. It embraces the ambiguity of our moment in history, while honoring the landscape and the ecological practices and relationships of the Coast Salish. By expanding the meaning and practice of the already multivalent term “land reclamation,” we make space for a decolonized future urbanism on the floodplain.

Acknowledgements

I extend my thanks to Don Welsh of the Semiahmoo First Nation for generously sharing his knowledge, and to the JAE theme editors Lisa Findley and Marc J Neveu, and reviewer(s) for their invaluable feedback that helped shape the paper.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Arthur Leung

Arthur Leung is an adjunct professor at the University of British Columbia. He is also an architect practicing on the unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations—where Vancouver is located today. His research focuses on resilient design in urban contexts at risk of natural hazards and disasters.

Notes

1 Keith Carlson, Albert Jules McHalsie, and Jan Perrier, A Stó:lō-Coast Salish Historical Atlas (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2001), 162.

2 The Stó:lō are regarded as a subgroup of the Coast Salish, which represents people from a larger geographical area in the Pacific Northwest Coast extending from British Columbia to Oregon. Both terms are used throughout the paper to reflect the varying degrees of specificity from the sources referenced. The use of the term “Coast Salish” is also meant to be inclusive of tribes and nations who do not identify as Stó:lō, such as the Semiahmoo. This is a reminder of the complexity of overlapping and shared territories of Indigenous groups.

3 Carlson et al., A Stó:lō-Coast Salish Historical Atlas, 162.

4 Wayne P. Suttles, The Economic Life of the Coast Salish of Haro and Rosario Straits (New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1974), 27–29.

5 British Columbia Assembly of First Nations, “Semiahmoo,” accessed December 20, 2020, https://www.bcafn.ca/first-nations-bc/lower-mainland-southwest/semiahmoo.

6 The coastal floodplain occupies approximately 20 percent of the municipal land area and sits within the agricultural land reserve.

7 Ausenco Sandwell, “Climate Change Adaption Guidelines for Sea Dikes and Coastal Flood Hazard Land Use: Sea Dike Guidelines,” BC Ministry of Environment Project No. 143111 Rev. 0, (Victoria, B.C.: Ministry of Environment, January 27, 2011).

8 Norman Hart Lerman and Betty Keller, eds., Legends of the River People (Vancouver: November House, 1976), 23–24.

9 Lerman and Keller, Legends of the River People, 25.

10 Different terminology is used for the original inhabitants of Canada. “Indigenous” is used internationally and by transnational organizations like the United Nations. “Aboriginal” was popularized in Canada following its usage in the Constitution Act of 1982. “First Nations” describes the Indigenous peoples of Canada who are not Métis or Inuit. “Indian” is considered inappropriate and outdated, but still used in legal contexts; it is also widely used in the United States. “Native” is another antiquated term that is still used today to encompass First Nations, Métis, and Inuit. First Nations Studies Program—The University of British Columbia, Indigenous Foundations, “Terminology,” accessed December 20, 2020, https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/terminology/.

11 Chief Harley Chappell’s telling of the story of the Great Flood has been paraphrased from a video that was a part of the “Che’ Semiahmah-Sen, Che’ Shesh Whe Weleq-sen Si’am (I Am Semiahmoo, I Am Survivor of the Flood)” exhibition at the Museum of Surrey, 2020–2021.

12 Wendy C. Wickwire, “To See Ourselves as the Other’s Other: Nlaka’pamux Contact Narratives,” The Canadian Historical Review 75:1 (March, 1994): 1–20; Keith Thor Carlson, “Reflections on Indigenous History and Memory: Reconstructing and Reconsidering Contact,” in Myth and Memory: Stories of Indigenous-European Contact, ed. John S. Lutz (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007), 52.

13 Keith Thor Carlson, The Power of Place, the Problem of Time: Aboriginal Identity and Historical Consciousness in the Cauldron of Colonialism (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010), 80.

14 John J. Clague, Nicholas J. Roberts, Brendan Miller, Brian Menounos, and Brent Goehring, “A Huge Flood in the Fraser River Valley, British Columbia, Near the Pleistocene Termination,” Geomorphology 374 (2021).

15 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Tsunami Historical Series: Cascadia—1700,” Science On a Sphere, accessed December 5, 2020, https://sos.noaa.gov/datasets/tsunami-historical-series-cascadia-1700/.

16 Joseph Trutch, “Report on the Lower Fraser Indian Reserves,” August 28, 1867, British Columbia. Papers Connected with the Indian Land Question 1850–1875 (Victoria: Richard Wolfenden, Government Printer, 1875), 42.

17 Robin Fisher, “Joseph Trutch and Indian Land Policy,” BC Studies 12:3 (1971): 5.

18 “The Red and the White,” The British Columbian, July 9, 1864; Powell to Attorney-General, January 12, 1874, British Columbia. Papers, 125–126.

19 Governor James Douglas to Edward Lytton, August 15, 1859, Dispatch No. 199, Colonial Office, 60:5, no. 10041, 13.

20 Carlson, The Power of Place, 171.

21 This legislation defined the initial rate of cultivation of land and required the construction of a log house with a shingled roof that was at least 20’ (W) x 30’ (L) x 10’ (H), amongst other rules. The Colonial Secretary to the Chief Commission of Lands and Works, July 2, 1862, British Columbia. Papers, 25.

22 Cole Harris, Making Native Space (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2002), 36.

23 Carlson, The Power of Place, 215.

24 At the time, “Indian affairs” was the official colonial term for matters related to Indigenous peoples. Although the use of the term “Indian” is now seen as politically incorrect, it is still used in legal settings. In this paper, “Indian” is also used to reference the terminology found in historical letters.

25 Wilson Duff, The Indian History of British Columbia, Vol. 1: The Impact of the White Man (Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum, 1992), 85.

26 Trutch was able to collect tolls for the Alexandra Suspension Bridge for seven years, having surveyed its site. K. Jane Watt, Surrey: A City of Stories (Surrey, BC: City of Surrey, Heritage Services, 2017), 30.

27 The settler-colonial project was an international business and Trutch revealed his personal financial interests in it through his exchange of letters with his brother John. Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 54–55.

28 Trutch to Sir John A. Macdonald, October 14, 1872, Sir John. A Macdonald Papers, vol. 278, Library and Archives Canada.

29 Trutch to the Acting Colonial Secretary, August 28, 1867, British Columbia. Papers, 41.

30 As an example, on April 27, 1863, Douglas wrote to then Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works R.C. Moody, stating: “Notwithstanding my particular instructions to you, that in laying out Indian Reserves the wishes of the Natives themselves, with respect to boundaries, should in all cases be complied with, I hear very general complaints of the smallness of the areas set apart for their use.” Governor Douglas to the Chief Commission of Lands and Works, April 27, 1863, British Columbia. Papers, 26–27.

31 Mr. Nind to the Honorable the Colonial Secretary, July 17, 1865, British Columbia. Papers, 29.

32 Trutch to the Acting Colonial Secretary, January 17, 1866, British Columbia. Papers, 32–33.

33 Robin Fisher, “Joseph Trutch and Indian Land Policy,” BC Studies 12:3 (1971): 12.

34 The gendered reference here reflects property laws at that time, when women of any race were not allowed to preempt land.

35 Carlson, The Power of Place, 177.

36 Mills to Sproat, August 3, 1877, Canada Indian Reserve Commission, Correspondence. See also Robin Fisher, “Joseph Trutch and Indian Land Policy,” BC Studies 12:3 (1971): 31–32.

37 “Speech by Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, Colonial Secretary to a Company of Royal Engineers, Leaving London in 1858 for British Columbia.” Manuscript from UBC Special Collections.

38 Bjørn Sletto, “Special Issue: Indigenous Cartographies,” Cultural Geographies 16:2 (2009): 147.

39 The dining table alludes to the Coast Salish aphorism “when the tide is out, the table is set.”

40 Fisheries and Oceans Canada, “Reasons for shellfish harvesting area closures,” accessed December 5, 2020, https://dfo-mpo.gc.ca/shellfish-mollusques/reasons-raisons-eng.htm.

41 Emma S. Norman, “Who’s Counting? Spatial Politics, Ecocolonisation and the Politics of Calculation in Boundary Bay,” Area 45, no. 2 (London, 2013): 179–187.

42 Chuck Davis, The Chuck Davis History of Metropolitan Vancouver (Madeira Park, BC: Harbour Publishing, 2011), 260.

43 Unfamiliar with the particularities of Native affairs in British Columbia, the Colonial Office was highly reliant on the advice of the officials on the ground.

44 Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 S.C.R. 1011–1012.

45 Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, 1010, 1069, emphasis by author.

46 Peter A. Walker and Pauline E. Peters, “Maps, Metaphors, and Meanings: Boundary Struggles and Village Forest Use on Private and State Land in Malawi,” Society & Natural Resources 14:5: 412, https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920119750.

47 The “Next Big One” is the overdue megathrust earthquake and tsunami event expected in the Cascadia region in the near future.

48 Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 13, doi:10.5749/minnesota/9780816679645.001.0001.

49 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability—Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 26.

50 UN General Assembly, Article 32.1, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, resolution adopted by the General Assembly, September 13, 2007, A/RES/61/295.

51 UN General Assembly, Article 29.1, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

52 Keller Easterling, Subtraction (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014), 4.

53 Lance H. Gunderson and C.S. Holling, Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems (Washington D.C.: Island Press, 2002).

54 Aqua fluxus as defined by Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha is counter to terra firma in the land-water divide.

55 Fisheries and Oceans Canada, “Reasons for shellfish harvesting area closures.”

56 The study area from this report includes Mud Bay and Boundary Bay. Robert W. Butler and R. Wayne Campbell, “The Birds of the Fraser River Delta: Populations, Ecology and International Significance,” Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Occasional Paper 65 (1987), 16.

57 Habitat Group, Fraser River Estuary Study—Habitat Report, Fraser River Estuary Steering Committee, Government of Canada and Province of British Columbia (1978), 7.

58 Dredging of the Nicomekl and Serpentine Rivers has ceased since the 1980s, but continue for the Fraser River to maintain navigable channels. Northwest Hydraulic Consultants Ltd., “Mud Bay Coastal Geomorphology Study” in Prioritizing Infrastructure and Ecosystem Risk Phase 1 Report (MCIP15330), City of Surrey, February 28, 2018.

59 Chief Harley Chappell, “Semiahmoo First Nation Blackie Spit History and Flood Song,” City of Surrey, October 18, 2018, YouTube video, 27:01, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xWBDHb3yZps&t=13s; Leonard Charles Ham, “Seasonality, Shell Midden Layers, and Coast Salish Subsistence Activities at the Crescent Beach Site, DgRr 1” (Ph.D. diss., The University of British Columbia, 1982).

60 The employment of innovative soft infrastructure technologies from “Oyster-tecture” by Kate Orff of SCAPE would be fitting in a location like Boundary Bay, which has a history of oyster farming.

61 Brian Thom, “The Paradox of Boundaries in Coast Salish Territories,” Cultural Geographies 16 (2009): 179–205.

62 John Agnew writes in the context of international relations where the enforcement of boundaries is motivated by the need to defend sovereignty. This can also be applied to the boundaries of Indian reserves nested within a nation-state. He argues that a historical-geographical consciousness would help break this “territorial trap” that is conceived as a “timeless space.” John Agnew, “The Territorial Trap: The Geographical Assumptions of International Relations Theory,” Review of International Political Economy 1, no. 1 (1994): 53–80.

63 Brian Thom presents this example in reference to Tim Ingold’s use of “meshwork” as a way to express the complex relational epistemologies of the Coast Salish peoples.

64 Carlson, The Power of Place, 55.

65 Jeff Oliver, Landscapes and Social Transformations on the Northwest Coast: Colonial Encounters in the Fraser Valley (Tucson, Arizona, The University of Arizona Press, 2010), 196–199.