Abstract

In the time of upheaval and crisis, what is the point of design education? In nearly every school of architecture or design there is a central, unspoken rejoinder to this question: the point of design education is to condition each successive generation of students for a lifetime of exploited labor that is detached from any critical relationship to the role that designers play in aestheticizing and instrumentalizing global capitalism. While there are always spaces of exception in the academy—the long tradition of community-engaged studios (e.g., Auburn’s Rural Studio and a number of design-build studios elsewhere)—most efforts tend to reproduce the long hours and infinite production that underpins so much of design education. This goal is not written in mission statements or strategic plans—to do so would threaten the machinery of student recruitment and major gift fundraising. But it is there, plain to see, in the tendency of design institutions to reproduce their most common traits: valorizing individuality and competition, endless work and infinite production, and service to the elites that fund much of the field’s work. Put another way, design education exists to reproduce the social and racial order of capitalism. And the core of its pedagogy is rooted in the studio.

This is hardly a novel analysis. Peggy Deamer deftly recognizes this relationship in Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present, writing that “while the construction industry participates energetically in the economic engine that is the base [of design practice], architecture operates in the realm of culture, allowing capital to do its work without its effects being scrutinized.”Footnote1 While reputation laundering has burst into the public’s consciousness through scandals related to the Sackler Family and opioids or Jeffrey Epstein and MIT’s Media Lab, design has not yet reckoned with its role in laundering capital across the world. Douglas Spencer gestures in this direction in The Architecture of Neoliberalism, writing that “while architects and architectural theorists have generally been less brazen (than Schumacher) about their enthusiasms for the subsumption of the urban and architectural orders to those of the market, they have tended, since the mid-1990s in particular, to push those same truths of the way of the world as have served [the logic] of neoliberalism.”Footnote2 This, borrowing from Fisher’s theory of capitalist realism, situates the design fields alongside the rest of the liberal moral order in finding it “easier to imagine an end to civilization than an end to capitalism.”Footnote3

Neither Deamer nor Spencer directly relate their analysis to the central role that studios play in design education. But their formulations of the postcritical, projective design fields are inexorable from the ways in which the studio shapes design education in general. Though individual faculty can and occasionally do work to subvert this tendency, the postcritical turn in architecture and landscape architecture—embodied in various ways by Somol and WhitingFootnote4 within the former and Corner, Meyer, and WaldheimFootnote5 within the latter, all of which coincide with the rise of neoliberalism and the momentary infatuation with “the end of history”Footnote6—has produced a form of epistemic hegemony in schools of design that treats markets and capitalism as natural, and criticism, theory, and leftist thought as at best, unproductive, and at worst irrelevant to practice.Footnote7 Even spaces of exception—the community-based, design-build, and other studios that attempt to build new alignments in the academy—often reproduce the same kinds of conditions for students. By that I mean they tend to demand the same kinds of overwork and infinite production and, crucially, they tend to continue working within markets, only at their ragged edge, to offer design services at a discounted rate. They often hew towards the idea that design is best when it builds, not questions, the political economy of the built environment. This is admirable, but quite different from a model that takes fervent, anticapitalist movements seriously.

Yet the studio is rarely imagined in such nefarious terms. Quite the contrary; many if not most studio critics are working in earnest to train their students to build a variety of skills, whether organized around technical expertise or critical thinking and analysis. Few challenge the supremacy or naturalization of markets. Fewer still take seriously the work of Black Marxists around sacrifice zones—the conceptual framework that racial capitalism requires sacrifice zones, that those zones are delineated in time and space by existing and imagined racial hierarchies, and that those spatial and temporal patterns repeat within and across communities, cities, and regions.Footnote8 While their efforts are surely important, they are no match for the power of an institution—especially elite institutions—to by and large manage capital and reproduce the status quo.Footnote9 Though it would not be appropriate to speak for all of the design disciplines or every single academic studio, it is clear that landscape architectural education remains mired in this mode of toxic reproduction. It tends to do so through the same narrow band of issues that have dominated the field for more than a half-century: aesthetic and formalist experimentation aimed inward and toward elite audiences; techno-futurist design fictions aimed at prefiguring the whims of Silicon Valley; and ecological pseudoscience aimed at producing verdant, nonhuman imagery for a mostly white, elite-led environmental movement (often with Malthusian undertones through concepts like the ecological footprint). For all of landscape architecture’s, architecture’s, and city planning’s self-referential talk about imagination and creativity, much of their praxis is organized around these themes and filtered through capitalist realism that masquerades as a kind of realpolitik—despite the total lack of political education in landscape architecture beyond vague, nonpartisan calls for voting and electioneering.

So again: what is the point of design education? For those who fancy themselves capitalist to the bone, then perhaps little, if any, change to the status quo is required. For those who do not, however, formulating alternatives to this institutional exploitation is urgent, necessary work. It is this search for alternatives that led to the Designing a Green New Deal (DGND) studio sequence in 2018.

Though some may refute the framing above, it has been ubiquitous—sometimes acknowledged, often implied—in nearly every studio review across a range of institutions over my four years directing the McHarg Center. It is also there, on the tip of most design students’ tongues, whenever they are asked and given space to honestly answer questions about their experience navigating schools of design—something that has become clear in exit interviews with former studio students each year. The machinery of design education exists to reproduce exploitation, and it has gotten very, very good at doing so.

Framing Climate Justice in a Design Studio

The DGND studio sequence flows from a simple premise—that not only must one look for ways to break this cycle of reproduction, but that one could not look at the world around them, creaking and groaning under the weight of multiple overlapping crises, and reasonably conclude anything other than how designers are trained is failing to accomplish anything outside of narrow aesthetic, technological, or faux-ecological aims. That, coupled with the luxury of a three-year commitment to teaching an advanced interdisciplinary studio from the University of Pennsylvania, allowed the mapping out of a multiyear process, linked through a series of shared research questions, pedagogical experiments, and experiments with immersive, “climate fiction” (cli-fi) storytelling. The DGND studios were never intended to offer a quick or easy solution to the problems of design education under capitalism. Rather, their development emerged from a recognition that any pedagogy or praxis aimed at subverting capitalist hegemony within a design school must be organized around the idea that “before landscape problems can be solved, they must be framed. Solutionism short-circuits this crucial step.”Footnote10 As of this writing, the second of three planned studios recently concluded (December 21, 2020).

These studios are framed around three key concepts: probing, usable speculation, and platforming. Within each studio and across the entire series, the concept of probing is derived from Lutsky and Burkholder’s “Curious Methods” essay. In it, they write that “probing is a mode of exploration that informs but does not limit. It is a creative process that involves asking and enacting questions… and is a non-linear operation… involving three components: inquiry, the process of asking and enacting questions; insight, which is generated through that process; and impression, or the representation of those activities.”Footnote11 Within each DGND studio, probing is structured into the work through a hybrid seminar-studio model of pedagogy. Over the first four to six weeks of each semester, students are engaged in close reading and discussion of critical historical, theoretical, and sociological texts tied to issues of climate justice,Footnote12 the energy transition,Footnote13 statecraft,Footnote14 and particular places,Footnote15 before any drawing, mapping, or design work is allowed to commence. Each seminar day involves a student-moderated discussion with at least one of the texts’ authors and a preparatory “seminar slack chat”—an hour-long exercise on slack in which a small group of students and I talk about key concepts and takeaways from the day’s readings as a way to prime the conversational pump for the entire class.

As these seminars conclude, students then work in teams focused on a specific region (Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, and the Corn Belt) to produce two key analytics products, informed by their seminar discussions: a manifesto, which serves as both a working conceptual framework for the students to begin understanding the sequence of extractive regimes that helped shape their region’s political, economic, and cultural history and present along with an argument for how and why to propose futures for them; and an atlas of the region, blending fieldwork (oral histories and interviews with local activists), counter-cartographies, and other spatial phenomena into a coherent package of images. These assignments are directly linked to Judith Schalansky’s conceptual framework in An Atlas of Remote Islands that states “I didn’t realize then that my atlas—like every other—was committed to an ideology. Its ideology was clear from its map of the world, carefully positioned on a double-page spread so that the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic fell on two separate pages… geographical maps are abstract and concrete at the same time; for all the objectivity of their measurements, they cannot represent reality, merely one interpretation of it.”Footnote16 Each of these assignments—the seminars, the manifestos, and the atlases—are tethered to the principles of inquiry, insight, and impression that comprise probing. This work forms the first half of each studio, with the manifesto and atlas forming the core of the mid-review.

For the rest of the semester, students are challenged to engage in usable speculation. The modifier “usable” is doing significant work here. It draws on the concept of “usable pasts” from public historians, in which “past national experiences can be placed in the service of the future”Footnote17 and that “we must learn how to make a better world out of usable pasts rather than dreaming of infinite futures.”Footnote18 This is distinct from most other forms of design fiction and speculation, which often aligns with methods and principles in Dunne and Raby’s Speculative EverythingFootnote19—a delightful book that treats speculation as a mostly technological and aesthetic proposition, eliding the blinders of capitalist realism, the constraints of contemporary politics, and, crucially, the demands of movements. In fact, usable speculation in these DGND studios is framed explicitly as a rebuke to Dunn and Raby—an entire seminar day is dedicated to deprogramming the kind of cultish individuality that it engenders in designers. It means centering the demands of the climate justice movement in the production of climate and design fictions, and, over the entire series of studios, investing time and resources into the kind of long-term collaboration and trust-building with those groups that are necessary if a design school ever intends to live up to its stated goals. In each studio, core collaborators are brought into the work by the instructor—most of whom are longtime collaborators in other contexts—as new groups and individuals are identified. As each studio concludes, some work is often carried forward through ongoing collaborative projects based in the McHarg Center and has included the Sunrise Movement, Gulf Coast Center for Law and Policy, the Green New Deal Network, and the Red, Black, and Green New Deal.

More instrumentally, the concept of usable speculation also engages with the theory that no one will ever understand or rally around a climate change energy transition through molecules (carbon in the atmosphere) or electrons (electricity in their circuits). Rather, people will only understand it through material investments in their lives and livelihoods—through the buildings, commutes, offices, parks, public works, and civic infrastructure that stitch together everyday life. So, in coproducing cli-fi with leaders from the climate justice movement, these studios aim to both illustrate their demands and, in doing so, to advance them by giving form, aesthetic, and visual culture to their demands—reframing conversations about climate justice and the Green New Deal from one of scarcity (for example, a ban on airplanes and hamburgers) to one of dignity and plenty. Within this framework of usable speculation, students are then charged with proposing and developing their own storytelling vehicles—things that have ranged from graphic novels and zines, to cookbooks and farmer’s almanacs, to children’s books, among many others (more on them below).

Finally, and most simply, these studios are dedicated to the principle of platforming. The reliance here is on Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s analysis of institutions and their role in reproducing a particular, self-serving ideology in Manufacturing Consent. They write that “the beauty of the system is that dissent and inconvenient information are kept within bounds and at the margins, so that while their presence shows that the system is not monolithic, they are not large enough to interfere unduly with the domination of the official agenda.”Footnote20 Though they are writing about the media ecosystem and elite capture within it, their analysis holds for much of design education—indeed, nearly all elite schools of design are funded in part by the same class of global elites at the core of Herman and Chomsky’s analysis. In these studios, platforming holds dual meaning. Materially, it relates to the ways in which the studio serves as a vehicle for elevating the demands of the climate justice movement—demands that, at best, are placed on the fringe of most design programs and, at worst, are banished altogether as unrealistic and divisive. Instrumentally, it relates to the ways in which this studio serves as a platform for students in their final year of study to begin building alternative career pathways for themselves—using the exposure and relationships these studios have provided to find modes of practice outside of the private, client-driven practice of contemporary design.

This latter point has been among the most generative throughout the DGND studios. They have not served as a way to reproduce the exploitative model of a “studio” or “firm” book, in which the unpaid and often un/undercredited student work is used by a critic or principal to “write” a book. Rather, it has resulted in students who have matriculated the studio becoming go-to leaders in the climate and environmental media, developing ongoing projects with the local movement groups they met, and leading studios and policy-focused work around the Green New Deal elsewhere.Footnote21

Fictions and Collective Dreaming in a Design Studio

In their visual essay on the history and future of democratic design, Liz Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers write that “if we can use design thinking, making, and enacting to visualize and explore the future together, then we will be able to harness our collective creativity to serve our collective dreams.”Footnote22 Their notion of collective dreaming is at the core of the work produced in each of the DGND studios thus far. Because these individual studios are linked—the second builds on the first, and so on—the following is a condensed chronology of the work being done in these studios to date. A third studio is planned, but its fate is a bit uncertain (more on that in the coda).

The first DGND studio, held in the fall of 2019, revolved around two core questions of implementation priorities: 1) what regions of the U.S. must be “won” in order to achieve the technical aims of the Green New Deal tied to decarbonization, justice, and job creation; and 2) from that more limited pool of potential regions to receive the first wave of GND investment, which ones belong at the front of the line—either because they are historic sites of public disinvestment, because they offer an opportunity to grow the climate movement’s coalition by making the material benefits of the GND real for those who do not already support it, or both?

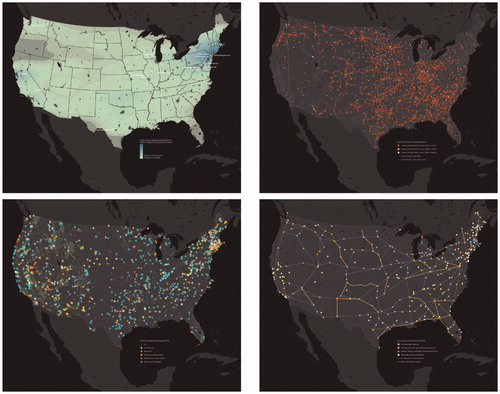

During the first half of the studio, seminars focused on the New Deal’s built environment legacies, sectoral plans for decarbonization (e.g., electricity and transportation), and policy sequencing and design.Footnote23 The studio then moved through an economy-wide analysis of the U.S., looking for critical clusters and overlaps of public housing, transportation, electricity systems, food production, water management, and public landscapes—all of which formed the basis of their mid-review. Over the course of a weeklong in-person and slack-based discussion, students then settled on three priority regions for rolling out the first wave of GND investments: Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, and the Corn Belt of the Midwest. This work was framed to purposefully exclude places like Manhattan, San Francisco, and Boston—not because they are unimportant, but because they are cities with a surfeit of financial, technical, and political capital that will develop an adequate response to the climate crisis (or not) whether or not a Green New Deal ever materializes. Indeed, the entire purpose of design studios like this is to operate outside of market forces—to work with communities and in places that cannot and never will be served in the short term by the firms beholden to those same market forces. So, while there are a number of other places that could have been selected through the framing offered, these three regions formed an excellent response to the questions above ().

Figure 1. These maps reflect the built environment legacies of the Works Progress Administration (top left), Rural Electrification Administration (top right), Civilian Conservation Corps (bottom left), and Civil Aeronautics Authority (bottom right). Credit: Allison Carr.

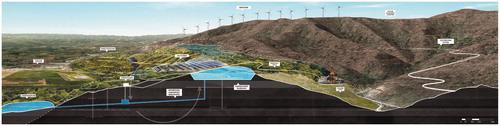

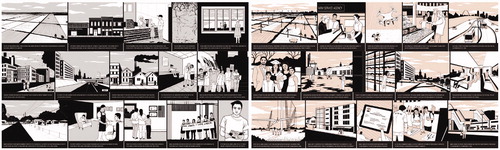

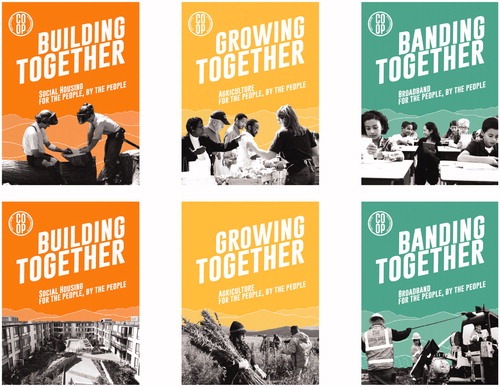

For the final half of the studio, students were charged with curating an exhibition of ideas and producing a report for policymakers on their work. The exhibition, held on December 19, 2019, was curated by Chelsea Beroza (city planning) and Rosa Zedek (landscape architecture)—an interdisciplinary team charged with designing the entire show, from material choices to wall space allocations. Students were also asked to think of their primary task as one of design communication—to create images and visual material aimed at speaking to broader publics about the kind of world that a Green New Deal could build. This led them to producing a series of propaganda posters, annotated and didactic sections showing the rollout of clean energy investments, speculative fiction zines about pre- and post-GND life in the Midwest, and a variety of other media rooted in cli-fi storytelling. Rather than a conventional final review, in which jurors arrive in all-black clothing and students stand at their boards sleep-deprived and largely excluded from the post-presentation conversation about their work, this group was charged with developing a set of gallery tours and programming a series of panel discussions that would allow the students to accomplish a few professional goals: to demonstrate their real expertise in this subject matter, to prepare them for speaking on panels and having conversations about their work, and to engender a more collegial, generous atmosphere for what is supposed to be a celebratory day ( and ).

Figure 2. This image was taken during the first “Designing a Green New Deal” studio exhibition. Credit: Katie Pitstick.

Figure 3. This section illustrates how clean energy infrastructure, surface mine remediation, social housing development, and public land improvements could be co-located and deployed along a range in Central Appalachia. Credit: Zachary Hammaker, Tiffany Hudson, Sara Harmon, Allison Carr, and Joshua Reeves.

In addition to including invited jurors and advisers who were with the studio throughout the semester—including Julian Brave NoiseCat (Data for Progress), Randy Abreu (Rep. Ocasio-Cortez’s office), Kate Wagner (architecture critic), and Peggy Deamer (Architecture Lobby), among others—the exhibition was open to the public, drawing more than 150 guests from the broader Philadelphia community (including members of the local Sunrise Movement and Philly Thrive, an environmental justice organization). The work was covered in Gizmodo and the policy report—edited by another interdisciplinary team, Tiffany Hudson (city planning) and Sara Harmon (landscape architecture)—is now being used by a large network of local climate justice groups in Appalachia and the Mississippi Delta for their organizing work.Footnote24 Their work also won the Award of Excellence for Community from the American Society of Landscape Architects in 2020 ( and ).

Figure 4. These comics focus on the development of three characters in the Midwest, tracking their lives pre- and post-Green New Deal-related investments in the region. Credit: Rosa Zedek, Chelsea Beroza, Katie Pitstick, Will Smith, and Jesse Weiss.

Figure 5. These posters are linked to a fictional social housing, co-operative agriculture, and rural infrastructure development program administered by the Appalachian Regional Commission. Credit: Rosa Zedek, Chelsea Beroza, Katie Pitstick, Will Smith, and Jesse Weiss.

In many ways, the second DGND studio, held in the fall of 2020, picked up where the first one left off. It began back in Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta, and the Corn Belt. Rather than taking an all-sector approach to regional analysis, the studio instead focused on three key industries throughout the semester—the industrial agriculture, fossil fuel, and prison systems. The studio was framed around these issues in large part because in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, the national organizing tables for the Green New Deal Network (where I often provide pro bono design and technical services) and the Movement for Black Lives merged a number of their strategies and operations. One of the first items to come out of that merger was a focus within the climate justice movement on those three systems—and their abolition as a key step in winning a Green New Deal.Footnote25 So this studio revolved around how to translate the demands of abolitionist movements linked to fossil fuels, prisons, and industrial agriculture into compelling, charismatic design fictions that could build up the library of images and stories about the future world a Green New Deal might build.

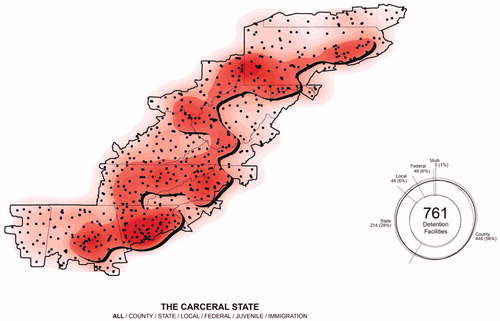

During the first half of the studio, seminars focused on the legacies of racial capitalism in each region, including the nexus between the plantation economy and slavery in the Mississippi Delta, settler-colonialism and absentee land ownership in Appalachia, and commodity landscapes in the Corn Belt. Students then worked in three groups—one per region—to develop a conceptual framework for understanding the political economy of each region, using that to produce an atlas of incarceration, fossil fuels, and industrial agriculture in each region, and from that proposing a series of key sites to focus their speculative fiction work throughout the rest of the course. Here, their work was framed around two key goals: to develop a critical rhetorical and cartographic analysis of how the fossil fuel, prison, and industrial agriculture landscapes of each region were produced and continue to be upheld, and to use that analysis to build an argument for interventions rooted in the demands of local abolitionist movements. Their conceptual frameworks and atlases formed the core of their mid-review, and they did not produce a single speculative concept or drawing until after this date (approximately week 9 of a 16-week semester) ().

Figure 6. This image is part of a much larger Atlas of Incarceration and Fossil Fuels in Appalachia that can be found at http://dgnd.us/appalachia-atlas.html. Credit: A McCullough, Chris Feinman, Diana Drogaris, Ada Rustow, and Amber Hassanein.

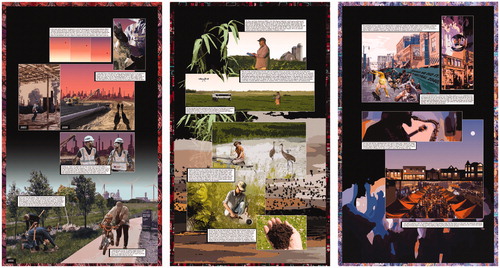

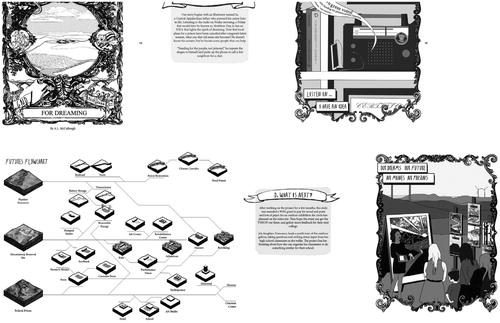

For the remainder of the studio, students worked in their regions—sometimes on their own, often collaboratively—to develop a set of speculative futures with local movement groups identified during the first half of the course.Footnote26 They were given considerable space to conceive of and then execute their own storytelling vehicles—several studio days were dedicated to “pitch sessions” in which students presented storytelling media precedents and assembled object lists to begin producing work for the final review. They found and developed relationships with movement groups in each region, with many of them coproducing the final work and joining the jury for final reviews. In all, the groups experimented with five storytelling vehicles: a “Workbook for Dreaming” aimed at democratizing the design process and based on the Fumbling Towards Repair workbook, a prison-to-rural cooperation manual, and a climate-driven community farmer’s almanac in Appalachia; a cookbook, a children’s book, and a fictional NPR podcast all linked to climate migration, agricultural co-ops, and prison abolition in the Midwest; and a series of zines, oral histories, and character development projects in the Mississippi Delta. Rather than a final review, students were asked to create a website (dgnd.us) to house their atlas and speculative futures work, and to lead a series of panel discussions moderated by invited experts Beka Economoupoulos (Appalachia), Bryan Lee (Mississippi Delta), and Anjulie Rao (Midwest). This took the form of a zoom webinar that included 30 invited respondents and jurors and nearly 200 members of the broader public on December 21, 2020 ( and ).

Figure 7. These images are part of a series of zine-based climate fictions in the Mississippi Delta that can be found at http://delta.dgnd.us/. Credit: Christine Chung, Al-Jalil Gault, Erica Yudelman, Rachel Mulbry, Pat Connolly, and Avery Harmon.

Figure 8. These images are from “A Workbook for Dreaming,” part of the larger set of climate fictions developed for Appalachia and found at https://appalachia.dgnd.us/. Credit: A McCullough.

Throughout these studios, design is viewed as an instrument of redistributive climate justice. Speculative design in particular is framed as a medium for translating the often-abstract demands of the various movements for justice into compelling, charismatic images and stories about the future worlds they intend to create. This isn’t merely an exercise in illustration, but rather a way of testing those demands—by giving them form and aesthetic, and by landing them in real communities and on real sites, through storytelling that opens up possibilities for the future rather than putting forward a singular, idealized future. Drawing on the work of Ruth Levitas in Utopia as Method Footnote27 and others in similar veins, students are challenged to develop the imagery and iconography of the world that Green New Dealers intend to build—often rooted in the idea that the fight for a GND becomes at least a bit easier when the frame of conversation moves from one of scarcity to one of beautiful, communitarian, low-carbon luxury for all. In that spirit, the advisers and jurors for these studios are comprised primarily of frontline and fence-line activists; movement leaders at organizations like the Sunrise Movement, the Gulf Coast Center for Law and Policy, People’s Action, members of the Democratic Socialists of America; and academic designers with affinities for, and/or real connections to, one or more of these movement organizations. Though this work is only just beginning, it is part of a larger project within the design professions—one that involves real political education within schools of design, materialist commitments to communities and issues throughout the professions, and a more confrontational role (at least within academia) with the systems of immiseration that shape design practice around the world. If the Green New Deal is about a total restructuring of the economy, then the DGND studios have been about finding a place for the design professions within that process.

Coda

In a sense, these studios have become extensions of a larger critique of the design disciplines first outlined in an essay for Places Journal titled “Design and the Green New Deal.” They have focused on rural communities already operating as sacrifice zones within the markets and flows of global capitalism that bound so much of contemporary practice. They have also pushed back against the ways in which capitalist realism frames what constitutes “pragmatism” in the design professions—a term often used to describe projects that are eminently buildable, even if their construction is predicated on the preservation of a status quo that all but ensures social and ecological immiseration. Put another way, the DGND studios have sought to question whether it is pragmatic to uphold the very systems of exploitation and immiseration that wrought planetary climate change in the name of building out one’s portfolio.

In its planned third iteration, the DGND studio will focus on two key sites in each region: the Mountain Valley Pipeline Corridor and the Big Sandy Correctional Facility (atop an abandoned mine land) in Appalachia; Angola Prison and the field of orphaned wells within the corridor of the Colonial and Plantation Pipelines in the Mississippi Delta; and the abandoned coal mines-turned corn fields and the Keystone XL corridor throughout the Midwest.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Marc J Neveu, Lisa Findley, and the anonymous reviewers for their incisive feedback on earlier drafts of this essay. I would also like to thank and acknowledge the incredible students and collaborators who’ve made so much of this work possible, including: 100 Days in Appalachia, Black in Appalachia, the Gulf Coast Center for Law and Policy, the National Family Farm Coalition, the Federation of Southern Co-operatives, Randy Abreu, Claudia Aliff, Leila Bahrami, Chelsea Beroza, Allison Carr, Salonee Chadha, Yvette Chen, Christine Chung, Daniel Aldana Cohen, Patrick Connolly, Peggy Deamer, Diana Drogaris, Beka Economopoulos, Christopher Feinman, Liz Gagliardi, Al-Jalil Gault, Zachery Hammaker, Avery Harmon, Sara Harmon, Amber Hassanein, Tiffany Hudson, Emily Jacobi, Katie Lample, John Michael LaSalle, Bryan Lee Jr., Rob Levinthal, Reinhold Martin, Rennie Meyers, Julian Brave Noisecat, Kate Orff, A. McCullough, Rachel Mulbry, Katherine Pitstick, Anjulie Rao, Joshua Reeves, Ada Rustow, Will Smith, Kate Wagner, Jesse Weiss, Erica Yudelman, and Rosa Zedek. I’m also indebted to Frederick Steiner, Richard Weller, and the broader Weitzman School of Design for giving me the space to build this studio and research agenda out through the McHarg Center.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Billy Fleming

Billy Fleming is the Wilks Family Director of the Ian L. McHarg Center in the Weitzman School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania. He has a fellowship with Data for Progress that has focused on the built environment impacts of climate change and resulted most prominently in the publication of low-carbon public housing policy briefs tied to the Green New Deal for Public Housing Act introduced in 2019. His writing on climate, disaster, and design has been widely published and his research has been supported by grants from the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy, Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, William Penn Foundation, Summit Foundation, Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Hewlett Foundation, and by a variety of sponsors in the design and building industry.

Notes

1 1 Peggy Deamer, Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present (New York: Routledge, 2014).

2 Douglas Spencer, The Architecture of Neoliberalism: How Contemporary Architecture Became an Instrument of Control and Compliance (London: Bloombsbury, 2016).

3 Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (New York: Zero Books, 2009).

4 Robert Somol and Sarah Whiting, “Notes around the Doppler Effect and Other Moods of Modernism,” Perspecta 33 (2002): 72–77.

5 For more on this, see James Corner, “Critical Thinking and Landscape Architecture,” Landscape Journal, 10(2) (1991): 155–172; Elizabeth Meyer, “Landscape Architecture as a Critical Practice,” Landscape Journal, 10(2) (1991): 155–172; and Charles Waldheim, “The Landscape Architect as Urbanist of Our Age,” in Landscape Architecture Foundation, The New Landscape Declaration: A Call to Action for the Twenty-First Century (New York: Rare Bird Books, 2018).

6 For more on this, see Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992).

7 Billy Fleming, “Design in the Time of Crisis: Landscape Architecture, Climate Politics, and the Green New Deal,” in Richard Weller, ed., The Landscape Project (New York: ORO Editions, forthcoming 2022).

8 For more on this, see Cedric Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1983), and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

9 Reinhold Martin, Knowledge Worlds: Media, Materiality, and the Making of the Modern University (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021).

10 Rob Holmes, “The Problem with Solutions,” Places Journal, June 2020, https://placesjournal.org/article/the-problem-with-solutions/.

11 Karen Lutsky and Sean Burkholder, “Curious Methods,” Places Journal, May 2017, https://placesjournal.org/article/curious-methods/.

12 Readings included but were not limited to House Resolution 109, Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/109; Kate Aronoff, Alyssa Battistoni, Daniel Aldana Cohen, and Thea Riofrancos, A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal (New York: Verso, 2019); and Kian Goh, “Planning the Green New Deal: Climate Justice and the Politics of Sites and Scales,” Journal of the American Planning Association 86(2): 188–195, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01944363.2019.1688671.

13 Readings included but were not limited to Myles Lennon, “Decolonizing Energy: Black Lives Matter and Technoscientific Expertise Amid Solar Transitions,” Energy & Social Science, 30: 18–27; Johanna Bozuwa, “The Case for Public Ownership of the Fossil Fuel Industry,” The Democracy Collaborative, available at: https://thenextsystem.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/Public%20Ownership%20Briefing%20final%20v5.pdf; and Reinhold Martin, “Abolish Oil,” Places Journal, https://placesjournal.org/article/abolish-oil/.

14 Readings included but were not limited to Brent Cebul et al., Shaped by the State: Toward a New Political History of the Twentieth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018); Michael Katz, The Undeserving Poor: America’s Enduring Confrontation with Poverty (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); and Shalanda Baker, “Anti-Resilience: A Roadmap for Transformational Justice within the Energy System,” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, 54: 1–48.

15 Readings included but were not limited to Clyde Woods, Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in Mississippi (New York: Verso, 1998); Richard Mizelle, Backwater Blues: The Mississippi Flood of 1927 in the African American Imagination (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014); Manu Karuka, Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019); and Karida Brown, Gone Home: Race and Roots through Appalachia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

16 Judith Schalansky, An Atlas of Remote Islands: Fifty Islands I Have Never Set Foot on and Never Will (New York: Penguin Books, 2009).

17 Van Wyck Brooks, “On Creating a Usable Past,” The Dial, 64:7 (April 11, 1918): 337–341.

18 Tony Judt, “The Last Interview,” The Prospect, 173 (July 21, 2010), https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/tony-judt-interview.

19 Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2013).

20 Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (New York: Pantheon, 1988).

21 Many of the students involved in this sequence are now working on the leading edge of the Green New Deal in organizing and policy domains, including: Katherine Lample, a Knauss Fellow assigned to the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee and Sen. Jeff Merkeley; Rachel Mulbry, a research associate with the climate + community project leading much of the research behind its green public housing initiative; A. McCullough, a project manager for the climate + community project; and Xan Lillehei, organizing fellow for Architects Declare in the U.S.

22 Liz Sanders and Pieter Jan Stappers, Convivial Toolbox: Generative Research for the Front End of Design (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2013).

23 All of my syllabi are publicly available. The 2019 DGND studio syllabus can be viewed at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1AsvYYqJ0vFHvvuwsK0dDxUOlcWenpB1czLv5-B0ZD5Q/edit?usp=sharing. The 2020 DGND syllabus can be viewed at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1_XpNhoxe0DlKxWUGJnUn8xvbb-ixKwoy/view?usp=sharing.

24 Throughout the fall 2020 semester, we were surprised to learn from many of our new Appalachian interlocuters that dozens of groups were now using that 2019 studio report in their organizing and advocacy work. Some of these findings are reflected in this component of the 2020 Appalachia group’s project: https://appalachia.dgnd.us/A-Practitioner-s-Guide-to-Appalachian-Futures.

25 Varshini Prakash and Guido Girgenti, eds., Winning the Green New Deal: Why We Must, How We Can (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020).

26 These groups included but were not limited to the Gulf Coast Center for Law and Policy, the National Family Farmer’s Coalition, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, Black in Appalachia, and 100 Days in Appalachia.

27 Ruth Levitas, Utopia as Method: The Imaginary Reconstitution of Society (New York: Palgrave, 2013).