Abstract

By reconsidering the Watts Urban Workshop’s architectural proposals for funding from President Johnson’s Model Cities Program, an outbranch of his 1964 War on Poverty, this microhistory outlines feasible architectural visions of reparations in 1970s Watts, Los Angeles. While most histories of the War on Poverty consider Johnson’s concept of “maximum feasible participation” as a driving force of self-help programming for poor communities as more of a gesture than a call, a consideration of the Workshop’s goals to teach self-determination and community participation shows how Black practitioners were thinking about reparative futures in ways that simply have not been registered by architecture, urban planning, or history.

War on Poverty must become more than just another opportunity to point out the fraudulent nature of U.S. Liberalism. It must be an opportunity to organize and involve in struggle the broad masses of poor, with the Black community as a vanguard, around concrete demands based upon the real needs of the people…It must be an ideology that has its testing ground not in the parlor, but in the streets.

—Bob Stewart and Richard Price of the Watts Action CommitteeFootnote1

Officially called The Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act, the Model Cities Program was implemented in 1966 by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Federal funding was set aside for large metropolitan cities like Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago to help develop social projects in response to the changes caused by large urban renewal projects of the 1950s. Through a number of open-ended grants, the program funded a combination of physicalFootnote2 and social programsFootnote3 that intervened in the impoverishedFootnote4 areas of America’s cities.

The initiative appeared to include the residents of poor urban areas that it wished to improve by asking for “maximum feasible participation of the poor.”Footnote5 The manner and degree to which residents would participate, however, was unclear, particularly because the program did not define citizen participation as “shared decision making.”Footnote6 According to the Organization for Social and Technical Innovation (OSTI), an outside agency hired by the government to monitor participation, six months into the program, OSTI saw little evidence of continued citizen participation during implementation stages.Footnote7

Even though Johnson’s language claimed to include impoverished voices through “self-help” programming, the agency found that “by and large, people were once again being planned for.”Footnote8 Indeed, rather than listen to community needs, Johnson’s programs were centered on changing the attitudes and cultures of impoverished people.

Nowhere was the disconnect between the language and practice of the Model Cities Project more clear than in Watts, Los Angeles, where Black architects and planners interpreted “citizen participation” as an opportunity to introduce new pedagogies to Black communities. Edgar Goff and Eugene Brooks, both planners and architects, provided guidance to residents on how to effectively utilize institutional language in planning to secure reparations for the disinvestment of Black communities.

Known in the early twentieth century as “the Hub of the Universe,” Watts was nestled in an area of 2.12 square miles in southeast Los Angeles, a main thoroughfare for four Pacific Electric Railway lines that connected Los Angeles to surrounding cities.Footnote9 In postwar Los Angeles, Watts was one of the few places where Black people were allowed to live,Footnote10 and by the mid-1960s, Black artists and writers living there made the area a center for Black cultural and artistic production. Many Black community organizations such as the Studio Watts Workshop (1964), Watts Writers’ Workshop (1965), the Watts Towers Art Center (1965), and the Mafundi Institute (1969) were headquartered in Watts.Footnote11

In August 1965, Watts received national media attention due to a community uprising in response to the arrest of 21-year-old Marcus Frye and the police beating of his pregnant mother, Rena Frye. Historically subject to paramilitary surveillance, when the streets of Watts erupted into protests, police tactics mirrored military responses to insurgency. Known as the “long hot summer,” this prolonged conflict received intense media attention.Footnote12

In the immediate aftermath of the Watts Uprising, Goff and Brooks founded the Watts Urban Workshop. A nonprofit organization and what one participant characterized as “the only indigenous organization in Watts trying to resolve the urban crisis facing this disorganized community,”Footnote13 the Workshop offered on-the-ground and direct-action seminars that taught Watts residents how to navigate urban planning policies and advocate for their needs as a community. Through seminars with names like Soul and T-Square, Goff and Brooks (pictured on the right in ) playfully acknowledged how their training in planning at UCLA and architecture at USC informed the Workshop’s curriculum content and design.Footnote14

Figure 1. In the last image in the above series, Eugene Brooks (B.Arch., USC) is shown standing on the left, and Edgar Goff (B.Arch., USC) is shown standing on the right.

Goff and Brooks believed that by constructing seminars, they could foster communities to actively engage in urban planning, and viewed pedagogy as the means to generate self-governed Black communities in the United States. Due to how closely it aligned with ideologies of Black Power and Black Nationalism which advocated for self-sustaining, autonomous Black communities, the Workshop’s pedagogical goal of generating agency was easily viewed as a threat.

While Johnson characterized the War on Poverty as a chance for the “maximum feasible participation”Footnote15 of poor communities, Goff and Brooks’ proposal to train individual residents of Black communities did not align with Johnson’s intended outcomes.Footnote16 It was certainly not the type of on-the-ground activity that municipal leaders who were facing urban revolts like the Watts Uprising wanted to indulge. In fact, when Goff and Brooks submitted their proposal to the Los Angeles area Model Cities Agency, one of their biggest detractors was Los Angeles Mayor Samuel Yorty, who saw these ideas as more “opportunities for black nationalism.” In his eyes, such philosophies would manifest in more incidents of urban unrest like the 1965 Watts Uprising. Such attitudes towards Black self-determination were confirmed when the City of LA left the Worskshop’s proposal out of LA’s first round of Model Cities funding in 1970.Footnote17

In 1971, the Workshop gained access to Model Cities funding and published a report called “Community Planning Project South Central Los Angeles” (). Close analysis of this report provides us with a sense of how Black architects and planners were actively thinking through the possibilities of an architecture of repair in direct response to federal programs. Through their report, Goff and Brooks responded directly to Johnson’s request for participatory “self-help” programming by proposing a specific kind of community space in Watts. In other words, Goff and Brooks wanted to build a space where they could teach people how to raise the bar for what “maximum feasible participation” could look like in Black communities.

Figure 2. Cover of Urban Workshop report, “The Community Planning Project for South Central Los Angeles.”

Goff and Brooks negotiated the term participation in a variety of ways, including their articulation of Black collective action in Watts where “no one person speaks for the community.”Footnote18 They also renegotiated the concept of participation through a three-pronged approach outlined in the “Community Planning Project South Central Los Angeles” report.

While one agenda of the report included building out a larger workshop space, other submitted components of the report elaborated on pedagogical practices that would enable residents to feel comfortable navigating institutional policy and speaking policy language.Footnote19 A third component of the planning project imagined “Ghetto Beautiful,” a self-sustaining city run by these paraprofessional residents newly trained to lead every municipal chapter of Watts, including the police force, hospitals, schools, and other municipal services.

Workshop Space

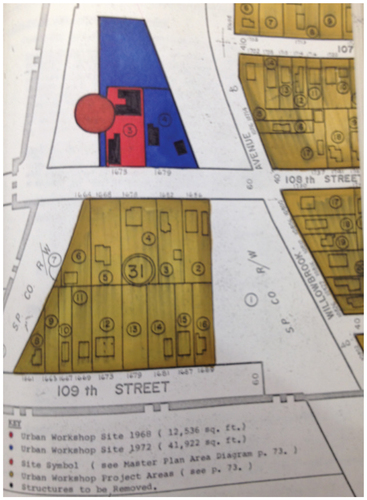

In 1968, the physical space of the Watts Urban Workshop occupied approximately 12,000 sq. ft. of its urban parcel (). Goff and Brooks intended to increase this to over 40,000 sq. ft. by 1972, reflecting a major increase and investment into the workshop space itself. By breaking down the walls around the Urban Workshop’s studio professional space, Goff and Brooks designed a porous space where practice and teaching could happen alongside one another. Furthermore, expansion of the space was clearly intended to encourage more community engagement, as one can see from the variety of functional spaces designated in their plan. Together the rooms, galleries and exhibition areas, training spaces, research library, arts and crafts laboratory, and “builders emporium”Footnote20 served as hybrid spaces meant to cultivate a collective Black citizenship in the Watts community. Reflecting the workshop’s goal of participation through engaged pedagogy and informed citizenship, over half the space of the Watts Urban Workshop was programmed for learning, education, and participation.

“Involvement is the Name of the Game”Footnote21

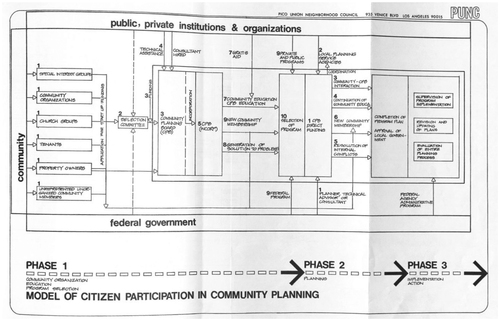

This bureaucratic pedagogical priority can be seen in a diagram created by the Workshop, titled “Model of Citizen Participation in Community Planning.” The Community Participation Diagram () served as an example of how the Workshop planned to enact curriculum design that could create a community of paraprofessionals. The diagram illustrates a hierarchical flowchart for the way that different arms of municipal government speak to and report to one other. Special interest groups, community organizations, church groups, tenants, property owners and underrepresented “unorganized” community members are each slotted into their own rectangle, and come together to form the “community.”Footnote22 As community stakeholders, each of these groups select programs and funds according to their desired outcomes. In other words, the “community” as it was conceived of in the diagram sits at the very center of public and private institutions and federal sponsorship.

The diagram makes complex bureaucratic processes clear for communities who had never worked within public systems before. Such training enabled Goff and Brooks to imagine the cultivation of a group of paraprofessional residents who were prepared to engage with civic projects as self-determined members of the community. The resulting collective self-determination contributed to the formation of Watts as its own self-governing Black community, not unlike separatist plans explored by Black freedom movements in the aftermath of the Watts Uprising. In 1966, members of the National Urban League (NUL) were featured in Jet Magazine, where they called to “make Watts a separate town in California,” and publicized a proposal titled “Freedom City.” Even freedom seekers who taught anticolonial cultural nationalism alongside more left-wing manifestations of Black Power, such as local Watts resident Ron (Maulana) Karenga, forwarded plans to make Watts a separate city. With language strikingly similar to Karenga’s phrasing for an operational secession of Watts and the NUL’s proposal for “Freedom City,” the Watts Urban Workshop developed their own proposal for an independent Watts, with an urban plan they called Ghetto Beautiful.

Referencing Daniel Burnham’s use of the word “beautiful” to title the Clean the City agenda in his 1909 Chicago’s City Beautiful project, Goff and Brooks’ Ghetto Beautiful project critiques aspects of Burnham’s agenda that displaced large numbers of people of color. In other words, Ghetto Beautiful gives land to Black citizens of Watts.Footnote23

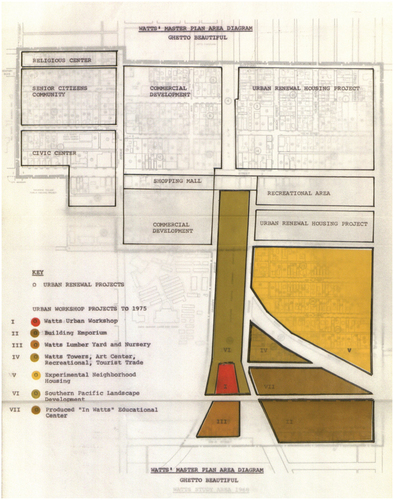

Ghetto Beautiful called for the improved quality of Watts, what the Workshop called “ghetto turf.”Footnote24 The Ghetto Beautiful Plan’s 115-acre urban plan, which included an industrial center, educational park, housing, and civic center, is one of the most pointed examples of architects using Black separatist thought as the basis for an urban plan. The Ghetto Beautiful Plan included a complete set of drawings with a multi-phased implementation plan. They were specified in detail as two-year, five-year, or longer-term plans and included various subelements for balancing land-use, circulation, and municipal service facilities within the general Ghetto Beautiful Plan. Though the master plan () does not include street names, based on the location of the Workshop in the map we can surmise that all parcel blocks left unfilled were north of 106th Street. These parcels included a shopping mall, two commercial development projects, a recreation area, two urban renewal housing projects, a religious center, and a civic center. With the Workshop (red) alongside experimental housing (yellow) and educational services (brown) anchoring the southernmost region of Watts, the Ghetto Beautiful Plan demonstrates how programmatic and social hybridity was essential to Ghetto Beautiful’s success.

Together, the workshop space and the proposed pedagogical seminars on planning, policy, and civic engagement were meant to inform the community and encourage residents to voice their needs in the language of planning itself. Goff and Brooks met Johnson’s initial call to arms with the War on Poverty, for educational “self-help” programs, by submitting their valid community plan that met Johnson’s call at face value. Simultaneously, their proposal supported the possibility of educating the Watts Black community to practice self-determination by actively navigating and shaping 1970s changes to urban development. Though they sound alike, these two goals, of creating a self-determined community and enabling maximum feasible participation of a poor community, did not intersect in the eyes of the government at the time. What is this incongruity between the idea of “self-determination” and “maximum feasible participation,” if not a willful rejection of the possibility of reparations?

By bringing the Urban Workshop’s architectural visions back into historical consideration, this microhistory outlines how the Watts Urban Workshop created a feasible vision of reparations in 1970s Watts, Los Angeles. The fact that this vision was never carried out gives architectural history yet another example of how Black practitioners were thinking about reparative futures in ways that simply have not been registered by architecture, urban planning, or history.Footnote25 Given that Goff and Brooks drafted and wrote a feasible pathway towards reparations for the Watts Black community in a way that satisfied President Johnson’s call to action regarding impoverished communities, now is the time to reconsider and advance their visions.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rebecca Choi

Rebecca Choi is currently a postdoctoral fellow and visiting lecturer at the ETH Zürich, and holds a PhD in architectural history and theory and a Master’s degree in urban planning from the University of California Los Angeles. Her research explores intersections of architectural agency, power, and labor practices through Black material production. Charting the racialization of politics, culture, and representation within architectural forms and urban spaces, her book project Black Architectures examines architecture’s relationship to the changing landscape of American race relations between 1940 and 1970, focusing on how antiracist protests, boycotts, sit-ins, and insurrections related to civil rights and Black Power movements impacted the field of architecture.

Notes

1 Bob Stewart and Richard Price of the Watts Action Committee, “Watts: Politics of Poverty,” Liberator (September 1965): 7–9.

2 This included housing, general rehabilitation, and improvement projects. Projects included.

3 Funding for social programs was directed to daycare, physical recreation, health, and educational services.

4 “Impoverished neighborhoods” were defined as areas that did not already receive municipal investment such as social services, and contained less than 10 percent of the city’s overall population.

5 John H. Strange, “Citizen Participation in Community Action and Model Cities Programs,” Public Administration Review 32 (1972): 655–69.

6 Organization for Social and Technical Innovation (OSTI), Six-Month Progress Report to Office of Economic Opportunity, Region 1, February 1, 1969, 27, 28, and 35, reprinted in Sherry R. Arnstein, “A Ladder Of Citizen Participation,” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35:4 (1969): 216–24.

7 OSTI, Six-Month Progress Report, 27, 28, and 35.

8 OSTI, Six-Month Progress Report, 27, 28, and 35.

9 See Mary Ellen Bell Ray, The City of Watts California, 1907 to 1926 (Los Angeles: Rising Co., 1985).

10 Rebecca Choi, “Watts Towers,” in SAH Archipedia, eds. Gabrielle Esperdy and Karen Kingsley (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012), https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/CA-01-037-0102.

11 Jerome Fortier, Watts: Art and Social Change in Los Angeles, 1965–2002, catalog designed by Jerome Fortier (Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University, 2003).

12 Watts Riot Collection, 1963–1970, Special Collections & Archives, University Library, California State University, Northridge, Los Angeles; Los Angeles Times “Eye Witness” coverage of riots; UCLA Special Collections, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive and California Ephemera Collection.

13 Robert Blair Ballard. “The Watts’ Urban Workshop.” Thesis research (B.Ar.) Arizona State University, 1969 Architecture., 1968.

14 Edgar Goff had worked for the office of Victor Gruen, widely known for designing regional shopping malls across the US, and Brooks continued to pursue a graduate degree in planning (although he never completed it) after completing his BArch at the University of Southern California.

15 Strange, “Citizen Participation.”

16 Indeed Black nationalists were expressing their discontent with the War on Poverty. In the Liberator, a monthly political magazine and leading intellectual incubator of Black Nationalist thought, Watts was described as the “greatest crusade of the 20th century.” Contributors to the Liberator included the Watts Action Committee (WAC), and they made precise connections between the “so-called War on Poverty” and the riotous response in the streets. For example, the WAC wrote: “the so-called War on Poverty seems to be another highly overrated Power Structure propaganda effort to convince everyone how much is being done for them…” Bob Stewart and Richard Price of the Watts Action Committee, “Watts: Politics of Poverty,” Liberator (September 1965): 7–9.

17 Los Angeles, California Department of City Planning: Applications to the Department of HUD for a Grant to Plan a Comprehensive Model Cities Program, 1968; A Concept for the Revitalization of South Central Los Angeles, 1967; Preliminary Plan for Watts Development Project No. 1, LA, 1967; Southeast District Plan Study: Phase 1, LA, 1968; Southeast Los Angeles District Preliminary Alternative Plan Concept Development Study, LA, 1967; Watts Community Plan, LA, 1966.

18 Ellen P. Berkeley, “Workshop in Watts,” Architectural Forum 130 (January–February 1969): 58–63.

19 According to WUW student intern R. Ballard, the Workshop’s goals were “to instruct community members in the processes, language, techniques, skills associated with urban planning.” Robert Blair Ballard. “The Watts’ Urban Workshop.” Thesis research (B.Ar.) Arizona State University, 1969 Architecture., 1968.

20 Ballard, Robert Blair. “The Watts’ Urban Workshop.” Thesis research (B.Ar.)–Arizona State University, 1969–Architecture., 1968.

21 One of the names of the seminars offered by the UW; see Berkeley, “Workshop in Watts.”

22 Urban Workshop, and Southern California Association of Governments, Community Planning Project: South-Central Los Angeles [Final Report], (Watts, Calif.: 1971).

23 While Ghetto Beautiful did seek to beautify and improve parks and public facilities with a variety of streetscaping designs, I take the stance that while UW never mentions Burnham, the architect responsible for the plan of Chicago in 1909 and for master plans for Detroit, DC and US-occupied Manila, the UW were critical of the historic displacement of people of color in large numbers to carry out urban beautification projects. For a critique of Burnham and claim of the City Beautiful as a real estate franchise, see Samuel Stein, Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State (London: Verso, 2019).

24 Robert Blair Ballard. “The Watts’ Urban Workshop.” Thesis research (B.Ar.) Arizona State University, 1969 Architecture., 1968.

25 Sriprakash, Arathi et al., “Learning with the Past: Racism, Education and Reparative Futures,” Apollo, University of Cambridge Repository, 2020, https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/310691.