Abstract

The Julius Rosenwald Schools, built across the segregated American South, had generational impact. This narrative explores this educational initiative’s investment in rural Black communities, the design of Black schools by Black architects for Black communities, and a current conservation project as an act of generational repair and reparation. The Rosenwald Schools embody the resilience and self-determination of African American communities across the southern United States, in direct response to the institutional inequities of Jim Crow, as a way to empower future generations of students and leaders.

A visit to a historic site, argues the scholar James Horton, makes a life once lived real Footnote1. Experiencing these places matters because it allows us to situate ourselves on the continuum of time, and in turn, helps us understand cultures before our own through a connection with meaningful memoryFootnote2. The practice of preserving our built environment has traditionally prioritized the image of place, but often falls short of preserving the fullness of its histories. The history of preservation in the South has favored architecture that reflects the image of Southern power structures of racism, and in turn helps maintain their longevity. The practices and motivations of historic preservation simultaneously sanctify (memorialize) and thoroughly dispose certain histories over others (erasure). To preserve in more equitable ways, these practices must consider and advocate for fuller and richer pasts. Historian and preservationist Brent Leggs argues that preservation is an act of racial justice and can foster real healing, true equity, and validation of all Americans and their historyFootnote3.

The rural South is made up of communities that raised generations of students who laid the groundwork for the Civil Rights movement, the majority of whom were educated in segregated schools, including Congressman John Lewis and poet Maya Angelou. The Rosenwald Schools of the American South, their physical buildings, teachers, and the communities that supported them made generational impacts through the education of Black children during Jim Crow. By 1928, one-third of the South’s rural Black school children were served by Rosenwald Schools, making it the most important initiative to advance Black education in the early twentieth centuryFootnote4. Today, due to lack of preservation and maintenance, the physical history of these places is being erased.

The Rosenwald School Program was a reparative building campaign with deep social and cultural impacts. Booker T. Washington, founder of Tuskegee Institute, imagined a future of equitable educational opportunities for rural Black children. With the support of white philanthropists from the North, Washington began addressing these inequities, one school at a time. Efforts in advancing southern Black education in the progressive era included the Peabody Education Fund, the Slater and Jeanes funds, the Southern Education Board and the General Education Board, which called for policy changes within state school systems. A partnership with Julius Rosenwald, CEO of Sears and Roebuck Co., helped expand and amplify Washington’s intended program by building approximately 5,000 schools across the segregated South. Washington and Rosenwald shared the belief that the physical buildings and facilities were most in need of improvementFootnote5. Up until this moment, Washington had been pursuing the building of country schools in Macon County, Alabama by collecting support from individual donors; the 1903 Harris Barrett School in Tuskegee remains today. It was these early schools that proved to Rosenwald the school building campaign was a worthy investment.

Julius Rosenwald sought to reconcile racial tensions between white and Black communities by supporting the construction of equitable school buildings. Prior to the start of the Rosenwald School Program, educational funding disparities in the deep South were significant, particularly in areas where Blacks significantly outnumbered whites in many rural counties. In 1909, in Lowndes County, Alabama, white schools received $20 per student while segregated Black schools only received $0.67 per student of public moneyFootnote6. Washington and Rosenwald sought to address this inequity.

The Rosenwald Fund provided seed money to fund one-third of construction costs, with local communities raising a portion of the funding or committing to in-kind labor, with white school boards funding the remainder. Rosenwald believed this matching-grant program would encourage cooperation between African American and white communities. Black communities were familiar with the double taxation structures of Jim Crow. They were left no choice but to pay both direct and indirect taxes for public education. Southern public school authorities diverted school taxes largely toward the development of white public educationFootnote7. Despite this double taxation, between 1913 and 1932 over 5,000 schools and buildings were built for a total of $28.4 million. The Rosenwald Fund’s donation of some $4.3 million had sparked $4.7 million in in-kind Black contributions. Local governments had in turn contributed $18.1 million (approximately 64 percent of total costs) with private local white contributions making up the remaining 4 percentFootnote8. The building of a school represented a community achievement, evidenced by the crowds attending the school openings (). The rural school buildings would most often be named after the community where they were built, as a namesake for the family who donated lands for their construction, or the church that served as a former school in those communities. These projects would collectively become known as Rosenwald schools.

Figure 1. The dedication of the first Rosenwald School, in Loachapoka, Alabama, well attended by community members. Julius Rosenwald Fund Archives, Fisk University Franklin Library, Special Collections.

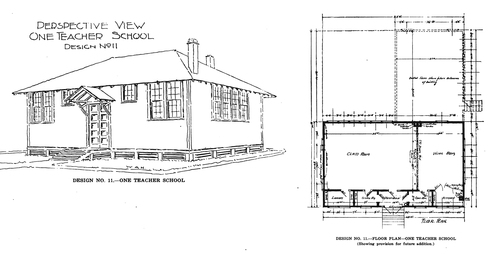

Prior to the establishment of the Rosenwald Schools, rural schools for African American children consisted primarily of dimly-lit, one-room schools where teaching, often with a single instructor, focused on a limited pedagogy of the “three r’s”: reading, writing, and arithmetic. Additionally, many rural communities that didn’t have a formal schoolhouse utilized churches as classrooms. To help address this, Booker T. Washington empowered Black architects to design schools for Black children. Robert R. Taylor and W. A. Hazel, architecture faculty at Tuskegee, led the design of the pilot and first phases of the Rosenwald School program, which was published by Tuskegee’s Extension Department in The Negro Rural School and Its Relation to the Community (Tuskegee Institute, 1915) (). Architectural decisions in these schools were focused on improving the quality of daylighting in the classroom, which enabled new ways of teaching while simultaneously improving learning.

Figure 2. Design No. 11, One Teacher School, designed by Robert R. Taylor and W. A. Hazel. From The Negro Rural School and Its Relation to the Community, (Tuskegee Institute: Tuskegee, Ala., 1915.).

Schools varied in typology. Of the eighteen types in the Rosenwald portfolio, one-, two-, and three-teacher schools were the most common. This variety of types gave agency to each community-specific agency to meet their individual needs. Published in Community School Plans (The Julius Rosenwald Fund, 1924), Rosenwald School designs were of such quality and economy that many Southern states would adopt the designs as model rural schools for white and Black students alike, appeasing arguments for ‘separate but equal.’ While the Rosenwald Fund only provided seed money for schools in Black communities, white Southerners benefited from the building program as well, in the form of modern school building plans developed by Black architects. In a time when white supremacists argued the inferiority of the Black race, the Rosenwald Schools refuted that view and transitioned modest country schools into thriving community institutions. As Rosenwald schools became model schools, they also became powerful, subversive, and physical statements about Southern education by stripping away more and more of its racial identifiers, making the building program an architectural challenge to Jim Crow and white supremacyFootnote9.

Following the racial integration of segregated schools across the South, many Rosenwald Schools closed their doors in the 1960s. The closure of schools resulted in the loss of significant community cornerstones, where students were no longer educated in their community or taught by community members. Some schools were privately purchased to serve as community centers, religious facilities, or even private residences. Most schools, however, have been or are at risk of being lost (). In 2012, the National Trust for Historic Preservation estimated that of all the Rosenwald Schools built, only 10-12 percent of the school buildings remainFootnote10.

Figure 3. Tankersley Rosenwald School, 1921–1967 in Hope Hull, Alabama, has fallen into disrepair and nearing structural collapse as the LiDAR scan represents. Photograph by author.

Historical sites are often preserved when they have wealthy and powerful advocates. As a result, the sites that are preserved become a reflection of those in power and their individual histories. Rayshad Dorsey, on antiracist practices, argues that “architects are responsible for negotiating hegemonic historical narratives, and this task is fundamental in supporting deeper and more comprehensive socio-spatial justice efforts in the present and future.”Footnote11 Similarly, conservation as reparations requires more equitable attention and investment in perpetuating erased or systemically and historically excluded narratives, not merely those with the power and the means to maintain and sustain their histories. Within the last five years, significant efforts towards preservation equity have been made through national grant programs by leading preservation organizations, including the National Park Service and the National Trust for Historic Preservation African-American Cultural Action Fund. All acts of conservation should be on the table, including the rehabilitation and sensitive adaptive reuse of these historic structures. More investment and consideration must be made to enable rural communities to determine possible futures for Rosenwald Schools for themselves.

Given the risk of loss, the Rosenwald Schools are the focus of a seminar I developed at Auburn University entitled “Critical Conservation: Representing the Underrepresented.” This course calls into question the traditional practice of historic preservation. Students explore the past by contextualizing historical events, documenting and assessing the current condition of a Rosenwald School, and by considering the potential future of how these places can be utilized again (). The course uses digital documentation technology including LiDAR scanning (including the iPhone LiDAR camera), photogrammetry cameras, and drone photography to create precise as-built digital records. Students meet with alumni of the schools and community members, and in doing so, they begin to understand their role as more than architect: as activist and advocate, empowered with necessary—and reparative—expertise in partnership with local communities (). Engaging architecture students in the field (not just as field of study) with extensive documentation and historical research around the Rosenwald Schools connects current generations to our physical and sociocultural pasts.

Figure 4. Architecture seminar students surveying the Tankersley Rosenwald School. Photograph by author.

The Rosenwald School Program aspired to serve as reparations within, against, and beyond the institutions of racial discrimination and segregation in the deep South. Reparations must acknowledge the fact that the pasts of Black, Brown, Asian, and Indigenous communities have been considered disposable while the pasts of white Eurocentric peoples have been sanctified. Rosenwald Schools are historically considered by economists to have created the African American middle classFootnote12. By foregrounding the Rosenwald Schools and their origins, the fuller impact of segregated education in the South is documented, and in turn highlights the particular values embodied in the architecture.

As these schools continue to fall into disrepair and ruin, the cultural artifacts of their architecture are lost. The building of Rosenwald Schools demonstrates the capacity for community action and grassroots development, and signaled a material challenge to the looming specter of Jim Crow, one school and one student at a time. The Rosenwald Schools are artifacts of the struggle for equality in education and existed to challenge systems of racial segregation and discrimination. The communities that worked to build them and fund them—through great personal and collective efforts—sought better lives for their childrenFootnote13. The Rosenwald Schools serve as a testament to the self-determination and resilience of the community that worked to build them. By connecting the people who originally planned, designed, financed, and constructed these schools with the people who now seek to document and preserve them, this effort empowers members of rural communities to preserve the enduring legacy of the Rosenwald Schools.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gorham Bird

Gorham Bird is an assistant professor of architecture at Auburn University’s School of Architecture, Planning, and Landscape Architecture, where his scholarship and practice explore architecture as a cultural artifact, its sociopolitical and historical pasts, and questions related to historic preservation, conservation, and adaptive reuse. In 2022, Bird and his research team were awarded a National Park Service African American Civil Rights Preservation grant to rehabilitate a dilapidated Rosenwald School. He is a graduate of Auburn University where he studied both architecture and interior architecture and holds an MSArch in Conservation from Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan.

Notes

1 James Horton, “On-Site Learning: The Power of Historic Places,” Cultural Resources Management 23:8 (2000): 5.

2 Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin, 3rd ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2012), 71.

3 Brent Leggs, “A Conversation about Landscapes and Preservation as Justice” (presentation, Pastforward 2021, online, November 22, 2021) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SJTI0sf2SMY.

4 Lester C. Lamon, “Black Public Education in the South, 1861–1920: By Whom, For Whom and Under Whose Control?” Journal of Thought 18:3 (1983): 76–90, www.jstor.org/stable/23801725, accessed March 3, 2021.

5 Mary S. Hoffschwelle, The Rosenwald Schools of the American South, New Perspectives on the History of the South (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006), 30.

6 “The Rosenwald Schools: Progressive Era Philanthropy in the Segregated South,” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, July 8, 2021, https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-rosenwald-schools-progressive-era-philanthropy-in-the-segregated-south-teachingwith-historic-places.htm.

7 James Anderson, The Education of Blacks in the South 1860–1935, 1st ed. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), 156.

8 Edwin R. Embree and Julia Waxman, Investment in People: The Story of The Julius Rosenwald Fund (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1949), 37–106; Hanchett, 387–89.

9 Hoffschwelle, The Rosenwald Schools, 273.

10 “America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places—Past Listings,” National Trust for Historic Preservation, March 2021, https://savingplaces.org/places/resenwald-schools.

11 Rayshad Dorsey and Natalia Escobar Castrillón, “Introduction: A Call to Anti-Racist Action,” OBL/QUE 4 (Fall 2022): 4.

12 Daniel Aaronson and Bhashkar Mazumder, “The Impact of Rosenwald Schools on Black Achievement,” SSRN Electronic Journal, October 2009.

13 John Lewis, foreword to A Better Life for Their Children, by Andrew Feiler (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2021), xii–xiii.