Abstract

Mabel O. Wilson teaches architecture and African American and African Diaspora Studies at Columbia University, where she also serves as the Director of the Institute for Research in African American Studies. With her practice Studio &, she was a member of the design team that recently completed the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia. Wilson has authored Begin with the Past: Building the National Museum of African American History and Culture (2016) and Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums (2012), and coedited the volume Race and Modern Architecture: From the Enlightenment to Today (2020). She is a founding member of Who Builds Your Architecture? (WBYA?)—an advocacy project to educate the architectural profession about the problems of globalization and labor. For the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, she was cocurator of the exhibition Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America (2021).

Cruz Garcia, Nathalie Frankowski, and Ema Yuizarix Garcia Frankowski held this conversation with Mabel O. Wilson in New York City on August 4, 2022.

WAI: On the occasion of the upcoming JAE issue on Reparations, we’re interested in thinking about reparations across different scales, political territories, and realities. As a background question, since we are all familiar with your work as a historian, designer, and consultant who’s continuously confronting the very problematic history of the United States, what would you say is the state of the conversation about reparations today? What is the state of reparations within an architectural framework, in your role as a historian, knowing that history has been so complicit and instrumental in formulating an absence of the damages reparations tries to address? And how do you see that conversation evolving? Is it stuck, or has it changed? Is there something that has been done? Or is there something that must be done in order to be able even to start thinking about reparations?

Mabel O. Wilson: Well, the fact that you’re doing the issue (on Reparations), I don’t want to say gives me hope, because I think that’s the wrong sentiment. But it certainly gives me confidence that the conversations, and hopefully the actions following those conversations, will lead to change. Because I think what’s useful about journal issues, like the one you’re doing, is it gives people the terms by which to have that dialogue.

I think this is the brilliance of the toxic Fox News media barrage, that they know the informational nuggets they put out always define the terms of the political debate. Even if it’s for a day or ten minutes. And they’re shrewd. I think it was George Lakoff, the political scientist, who said that you have to frame the discussion, that you have to put the terms out by which you want to have the discussion, that you can’t assume people have the vocabulary to even interpret what it is that they’re even experiencing in their everyday lives.

And I think that is the work of social movements, to define and circulate those terms of political debate, which is exactly the meaning of the term “consciousness raising.” Since we are linguistically based as humans, to some extent, to make someone aware, you have to be able to say it in the most apropos way in words that reflect someone’s experiences in the world. And I think a lot of that language on reparations has been absent, the historical reasons why they are necessary is exactly what has been redacted. And history as a discourse is certainly one thing that gives meaningful narratives to the nation-state and narratives to capitalism. In modern times, advertising has become a generator of those narratives, visually and aurally. And so I think an issue like this one [on reparations] will be helpful, particularly in a discipline like architecture that has certainly been integral to building spaces of racial inequities.

WAI: There’s something really, really interesting that you mentioned. I would like to go into the framework of the current political discourse. You mentioned Fox News, and how it embeds us in the construction of a populist discourse that reappropriates, weaponizes, and instrumentalizes critical concepts like, for example, Critical Race Theory. We are in a moment where not only critical positions like those discussed in Black or Gender studies are questioned, but even historical facts, like slavery, plantations, and colonialism. Many states across the US have implemented bans on books and classes that discuss these topics. This has happened at many levels of education, but has also made its way to the university. Are we experiencing a new form of backlash for many of the things that the protests of BLM in 2020 were trying to address? Do you think this is a particularly new phenomenon, or is it just another recurrent practice? Is there something that we can learn from history, even from your own experiences?

Wilson: I think the question that you are bringing up is where does the university sit, which is where we teach? And what is our responsibility in professional schools as educators of future architects? There are different ways of understanding how the university contributes to our political discourse. Historically in moments of political unrest, bourgeois intellectuals within the university—the institution that produces knowledge in and of the world—were an initial group to harass, silence, and perhaps even imprison. Institutions of higher education in the United States to some degree, tend to be more left leaning. Its disciplines have launched critiques of nationalism, capitalism, liberalism, sexism, racism, and so on. But on the other hand, as Black, feminist, postcolonial, and Native studies have shown us, the university has played an important role in the formation of bodies of knowledge that created the West. The university and its disciplines “universalizes,” it produces the West’s modern episteme. The university defines and circulates the terms and ideas that make the world fit within its worldview, which makes the university complicit in the West’s colonial and imperial projects. And that’s why I find Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study useful because it provides a manual for how the dispossessed and the colonized can engage the university.

WAI: We want to go back to the topic of language, because we think that’s also something very important, especially as you’re saying, in terms that are so fundamental to open the discussion. And we’ve seen different trends of reappropriating those very important terms in very superficial ways just to capitalize on the movements that have been taking place these last couple of years. Also, there has been a lot of fearmongering created behind those terms, so it becomes very important that they are used correctly. So, we wonder, how do you see the importance of language? And what tools can we think about in terms of bringing those terms into a real discussion so they become part of our daily language, especially in a field like architecture, where we have to deal with the material ramifications of very violent histories?

Wilson: I’m very interested in poetics, in particular Black feminist “poethics,” because I think poesis is a transformative act, it takes the everyday and transforms it into something else. Poetry has the power to shift the ways we name and think about things, it changes our perspective. Poetic language isn’t burdened with having to freight the exact meaning. It liberates meaning.

WAI: Or the scientific way…

Wilson: Exactly, and especially English. Poetry makes language malleable; it opens words to a multiplicity of possible meanings. There are a lot of people who are expanding the notion of “poesis” to think and make liberation. Fred Moten, who is a poet, is a perfect example. I’ve been reading and teaching Zong! by poet M. NourbeSe Philip. The way she transforms a legal document is a revelatory poetic act. She operates on the language of the legal record in order to create a psychic space of remembrance of the lives of enslaved people who were murdered when they were thrown overboard in the Zong massacre (1781). But the violence continued in the absence of their names in the two-page legal record of the court case, an important milestone for ending the British slave trade. Over 200 enslaved persons didn’t exist as human beings because they had no names, no dates of birth or death, they were merely cargo. Thus, they had no habeas corpus, they had no right to be seen by the law. Poetic acts like Philip’s can transform political discourse. The political, after all, defines our modern subjectivities such as the self, the citizen, the resident, the criminal, and so on. Therefore, in terms of language, I feel there is great potential in the poetic to transform discourses, ideologies, and institutions that do great harm.

WAI: Indeed, as you mentioned, poetry is so important, especially in the context of the Caribbean, with Édouard Glissant but also the ones that are not as recognized, or published in English or French or Spanish. Much of our contemporary decolonial or anti-imperialist political theory is written in the form of poetry, which displays that malleability and usefulness you are referring to. Another aspect of poetry is the capacity to disguise in a way what a legal document won’t necessarily allow. And poetry allows for those sorts of contradictions to exist. There are also things that may speak to some people that may be unnoticed by others because they lack the conceptual or linguistic tools to decode it. In this way, this also relates to studies on architecture, and connecting it back to your own work…

Wilson: I would add to that list: Martinican psychiatrist Frantz Fanon. Through the inclusion of Aimé Césaire’s poetry in Black Skins, White Masks, Fanon uses poetic acts to transform the colonizer’s language of French.

WAI: Aimé Césaire and Glissant provide so many useful thinking tools. Ideas about opacity, archipelagos, and even Négritude or Black consciousness. They are poetic in a way, because they’re impossible to understand without that capacity of transformation of language. But what we wanted to connect it to has to do with a different type of disguise. You have dedicated part of your work to the state of Virginia, where we also got to live during a very traumatizing year.

We’re interested in how you have revealed historical facts that, although evident in the documents you have shown, remained hidden from public discussion. We have seen some of your lectures about the history of the University of Virginia, showing a fairly recognized and iconic drawing where a slave appears carrying a professor’s baby. We would like to learn about if and how the conversations about reparations are taking place in those contexts where engaging with the material history of slavery, or the acknowledgement of the role of Blackness and race, are constantly downplayed. And as we all know, your work really shows undeniable proof of those very problematic histories. So, in a very poetic way, there’s also scientific evidence to your work. Do you find forms of ideological or institutional resistance to evidence in your research?

Wilson: I think that’s a great question about the necessity for proof and evidence in the production of history and historical narratives. But as you know, history is a discipline and a discourse that emerges from the West, from its universities. History creates periods in order to separate the modern from not-modern, to place Euro-American civilization in advance of the ahistorical primitives and savages. So, in and of itself, history is a problematic discipline that has been a useful tool of domination.

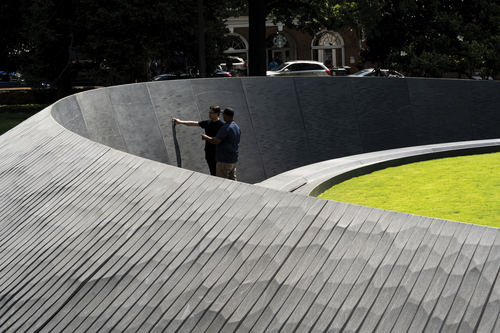

Remembering this problematic was important when we designed the memorial at UVA. The typical monuments are built to remember people who have left records in archives or sometimes in the built environment. Typically, you know when they were born, you know when they died, you know what they did, you know what they looked like, history reproduces a narrative of some aspect of their lives. But when you don’t have the records, precisely because they were not humans but things, how do you remember them? How do you use the form of the monument, which is about power, to represent the thing that had no name, no dates, no image? That was what was so difficult about designing a memorial to enslaved people. Because we had to engage the violence of slavery that had erased the humanity of this enslaved community.

I’ll never forget when we started reviewing the documents to design the memorial’s timeline. I read through it and just had to close the document right away, because it was filled with acts of violence. I thought, “how are we going to make these fragments into a historical timeline?” How do we recuperate, or as someone said, “rehumanize” a group of people, many of whose names we don’t even know? That was a big challenge. But it also made me realize that the architectural form of the monument was also a problem because of the kinds of evidence it requires to fulfill its commemorative function.

What’s been helpful for me is to constantly be conscious of the fact that the university is a problem, that the discourse of architecture is a problem, that history is a problem, that liberalism is a problem. They construct a modern world in which my being—in language, in institutions, in space—is not allowed to exist, not allowed to be human. Quite the opposite, modernity’s project is to eradicate my being—swiftly or slowly. Which is why I think the evocation of “Black Lives Matter” is strategic. Because the “unmattering” of my life, which is the project of modernity, has to be halted, be reversed. I’ve always thought that the term “Matter” was so smart, because it’s exactly the way the modern world constructed Blackness to dispossess and destroy its others—inclusive of Black, Brown and Indigenous folks.

WAI: And it’s incredibly powerful. And you know how powerful it is that by stating a fact, people get angry. It’s like saying water is wet, and people yelling at you, “well, juice is wet too!” (laughter). We’re just stating a fact, that Black Lives Matter, and you still feel like you need to insult me or something.

Wilson: What happens when you assert that Black Lives Matter is you tap into the violence that was and is necessary to maintain that myth of the universality of whiteness, as “Man” (to employ theorist Sylvia Wynter’s term here).

WAI: As everyone’s standard.

Wilson: As everyone’s common experience of being human.

WAI: The American Wing in The Met is the whitest thing ever, and somehow, it’s bulletproof because I’m sure they have gotten criticism, and they added three little labels about the Indigenous version of genocide. But that’s it, nothing changes. No, not at all. It’s like, bulletproof ideology, there’s nothing you can do to move it.

Wilson: And whenever the hegemony of whiteness gets challenged, white supremacy gets challenged, there is a vicious and violent backlash. Always, always. And that’s exactly the moment we’re experiencing now.

Because that’s how whiteness maintains its order, its modes of domination.

WAI: And even going back to the idea of the monuments. What happens when the state is a monument? When the settler-colonial state is the monument?

Wilson: It is the monument.

WAI: What happens when the university is the monument? That’s the concrete, material manifestation of the memory of the settler-colonial state.

Wilson: I’ve been part of a group here at Columbia that’s trying to figure out what to do with all the buildings named after white men who had associations with slave ownership or trade.

A dormitory in the medical school, for example, is named after Dr. Samuel Bard. Now it’s become known that Bard didn’t own one or two, but multiple enslaved people. He was a medical doctor and helped found the first medical school in New York City (the second one in the country at what would become Columbia University). There’s Hamilton Hall named after Alexander Hamilton who “may” have owned slaves. There’s Thomas Jefferson, who owned hundreds of slaves, and his statue sits in front of the Journalism School. There is Havemeyer hall. The Havemeyer family’s sugar refinery in Brooklyn became Domino’s Sugar. And the sugar cane that initially contributed to the family’s immense wealth came from slave plantations in Cuba. These are the names that make up the university’s symbolic landscape.

WAI: Which connects back to that project of Kara Walker (A Subtlety, a large-scale public project presented by Creative Time at the Domino Sugar Factory) connected to gentrification processes in Brooklyn.

Wilson: That’s exactly where the Havemeyer factories were. The original factories are in Brooklyn, which became the Domino Sugar refinery. What has taken its place?

WAI: A huge gentrification development.

Wilson: Exactly, which is just a continuation of the extractive logic of capitalism.

WAI: This connects to what we should even call these processes. As in the case in Puerto Rico, where we started questioning if it’s gentrification, or just the ongoing project of settler-colonialism. Because it’s still the same project. It’s not really like it changed into something else. It’s the same forces behind it.

Wilson: Yes, it all operates by spreadsheets, the ledgers recording the transactions.

WAI: We’ve heard Angela Y. Davis talk about things like free university for all, as a way of reparations. But how do we even address reparations when we don’t even have the records of those who were damaged, and destroyed, and separated? Maybe this is a question for the imagination, but how do we even start with reparations knowing that white supremacy operates like it’s a continuous eraser? As it goes through history and rewrites it again and again to fit its narrative? How do we engage with repairing something that we cannot even find that is broken?

Wilson: I think within the idea of erasure is both removal and destruction. The extractive, exploitative nature of capitalism just lays to waste so much. Basically, we’re killing the habitat for the human species through capitalism’s voracious cycles. It’s why everything’s burning, flooding, cities and landscapes are being destroyed. That extractive project at a global scale is making the planet unlivable not only for human species, but also for many other species. The planet, mind you, will still be here. There will be some species that survive, but maybe not Homo sapiens. So that’s the question: if we are to repair, how much of it do we repair, and how much of it do we have to start anew or transform? How can we live together without killing off other species, without killing off our habitat, and without killing each other?

WAI: That’s an incredible positioning. One of our ethoses as a collective is that other worlds are possible. Which then brings the question: are reparations even the actual issue? Or do we need something else?

Wilson: Yes, I would just ask, how much of it do you want to (repair), especially if it’s a system that we know is not perfect, that we know is destructive?

WAI: Yeah, like capitalism is not salvageable.

Wilson: Is it worth repairing? Or what aspects of it could be useful to retain? And what aspects would then have to change? Same with the university. What does it mean to be a free university as Angela Davis suggests? What would you change, especially in light of its late capitalist transformation into the corporate university?

WAI: Which links to all these other questions at the planetary scale. A lot of your research is centered in the history of the settler-colonial state of the United States. But many of these questions, they really have no boundaries. If we think about the transatlantic slave trade, especially the case of Haiti being the first successful slave revolution to form a legitimized form of government, to then having to pay tens of billions of dollars in tax to enslavers and their families. Haiti is still suffering the consequences of their revolution. And so are all of us. Achille Mbembe calls this “the becoming Black of the world” by means of neoliberalism, the industrial military complex, the process of turning the blueprint of the plantation into a global condition. As this machine of extraction and asymmetrical wealth accumulation keeps expanding, it becomes increasingly difficult to address discussions based on ideas about the nation-state without addressing the planetary scale of everything we’re doing. And particularly the United States being the biggest polluter, the biggest military power that the world has ever seen. And now, talking about education, how some of the most powerful universities are continuously constructing positions and narratives of hegemony and imperialism. How do you see that relationship between the knowledge and the struggles that are particular to some regions, and the networks of solidarity, networks of struggle, oppression, and emancipation around the world?

Wilson: That’s a big question. One I don’t know the answer to. I think that COVID disrupted the system’s flows. In part because it debilitated labor, or the bodies necessary to keep the global economy moving apace.

Also, as we were discussing, by not working, people discovered, “oh, I have time to learn something new, I can spend time with my family or friends.” I think people discovered there was something beyond earning wages, that gave life meaning, that sustained life.

But the machine of Global Capitalism needs the energy of labor, or as Marx would say “labor power.” And right now, it’s in crisis. And I think that the 99 percent who keep the system churning are not happy with the billionaire class. It’s a class that emerged from the digital and financial revolution and has essentially allowed elites to accumulate wealth from not just one concentrated area, but from across the globe.

WAI: Which is also connected to the plantation, right? The transatlantic slave trade was basically the beginning of globalization.

Wilson: The plantation’s enclosure has now enclosed the entire globe and it never ends well for the planter class. The plantation owner knew he was outnumbered by his slaves. So he had to employ the police, which in their origins in the US deployed regimes of violence to contain and control the forced labor. Today, will the world be like the US and employ almost one-third of its labor as guard labor in order to protect the wealth of the top one percent? Or will that order break down? I don’t know whether there’ll be a radical redistribution of resources, but I don’t think the current system of accumulation is sustainable.

What can one do with billions of dollars like Jeff Bezos? At least Bill Gates is trying to give his away via philanthropy. I love that Bezos’ ex-wife (MacKenzie Scott) can’t give away the money fast enough. You really can’t buy anything with that amount of wealth, it is essentially useless except in making more money. And yet that amount if spent in the right way could have a real impact for people who don’t have clean water, a place to live. Truthfully, these inequities are not sustainable in the long term, especially on a planet whose ecosystem is also in peril.

WAI: With your idea of narrative, it goes back to the question that was asked before, but also as a historian we were really interested in how you see the construction of history, including the question about futures. If we speak about optimism, maybe that’s where it lies, in thinking how we can have the right to construct a better future. But what does it mean to have the right to construct your future? Is the right to construct your future a tool for resisting what is happening right now? Can we also reclaim the right to do so?

Wilson: Maybe we need to rethink the nature of history. I was reading somewhere a few months ago that in Peru, they believe that in ancient Andean cultures the past, present, and future were not linear or sequential, but were all parallel. I thought this was really quite interesting, that the past is simultaneous with the present, which is simultaneous with the future.

And I wonder if just that kind of reorientation would change how history has been used to validate colonialism, imperialism, and racism. The emergence of history as a modern discipline in the nineteenth century assigned racialized “others” to the past. It rationalized wiping out indigenous populations through Manifest Destiny by affirming: “Well, they’re a dying civilization, so why not take their land?” Or “they are primitive and savage.” Consigning a group of people to the past rationalizes their erasure or consignment to the enclosure of the reservation or the ghetto or the favela. The future, on the other hand, for those who are modern, becomes a site of possibility, of speculation. But if we shift to say that they’re simultaneous, I don’t know, maybe that’s one way of recalibrating the damage that has been done by the West’s ethos of progress and development.

WAI: One of the thinkers that we reference often is the Bolivian philosopher Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui. She talks a lot about the spiral temporality of time. She also strongly criticizes powerful US universities and how they have been turning students into the consumers of their own knowledge, and universities in the Americas for valuing asymmetrically very problematic Eurocentric forms of knowledge. In the architectural sense, knowing that architecture is so complicit in all of this, as an institution, as a form of knowledge, as a practice of extraction, accumulation, as a measurement of colonial time, and as a tool of settler colonialism: how do you imagine the role of architecture? Can we imagine a different form of thinker who uses architecture as an instrument to provide other ways?

Wilson: I have this ongoing conversation with an architectural historian at UVA named Louis P. Nelson, who has actually done great scholarship on the history of slavery at UVA and plantations in Jamaica and elsewhere. And Louis agrees that “architecture” is the Western definition of building. But there are other ways to think and make buildings. So, if we look elsewhere, outside of the West, perhaps we should consider it as building rather than the Eurocentric term “architecture.” The West applied its concepts and categories of the art of building, “architecture,” through architectural history to other forms and methods of building found in other parts of the world. In the application of styles, for example, they formulated hierarchies and definitions of what is modern, ancient, or as Banister Fletcher categorized “ahistorical.”

And so I wonder if there’s a way to think about building that allows for a more sympathetic and reasonable use of resources. And that might also challenge the tethering of architecture to capitalism, colonialism, and imperialism. Because architecture became the tool by which Europe built Empire, by which it constructed the infrastructure that moved commodities, slaves, and wealth from the colony to the metropole and back. The wealth from Europe’s colonies funded the building of banks in the nineteenth century, the building of high rises in the twentieth century, and now it’s the building of supertalls. And so, rethinking what building is outside of architecture could be a really interesting project, or perhaps a more apt process.

WAI: Which brings us even to the concept of world building.

Wilson: In a way, yes.

WAI: I love the name that you’re using to describe a process. Rather than a discipline, which is really problematic. And also building. What is building? Is it the action, or the name, that’s building something?

Wilson: That’s why I say process, because project implies projection, as to project into the future, which can become a means of financial speculation and profit. But a process may be more enmeshed in the social engagements between people. This is why it’s productive to be cognizant of language. I typically ask my students to look up the etymology of words. When I teach nineteenth century architectural history, the second week of the course examines “race and nation,” so we look at the definitions of “race” in the OED. We unpack the origins of terms like “nation” or “social” or “style” or all of the terms that we think we know. The origins of these words in English or Latin, or whatever the original language it came from, can reveal their connections to histories of colonialism. These are things that you have to address when you talk and teach about architecture. You can’t escape it, it’s impossible.

WAI: And yet, somehow people manage (to escape it).

Wilson: Exactly. I just found today a review of the memorial to enslaved laborers at UVA in the American Conservative.

WAI: What did they say?

Wilson: They hated it. They launch a full frontal critique of abstraction. They even make fun of the eyes of Isabella Gibbons, an enslaved woman who labored as a cook at UVA. My guess is that they wished there was no memorial to slavery on the grounds. They say its abstract circle made from granite has nothing to do with the historical architecture of Jefferson’s academical village. It doesn’t fit into the character of the campus, because it’s not brick with white columns.

WAI: In a way that’s the whole point. It doesn’t fit. That’s a compliment, actually. It’s like, every time people say you’re un-American. Yes. Whatever thing you think America is, yes.

Image list for On Reparations and the Possibility of Other Systems

Robert E. Lee Monument as it stands in Richmond, Virginia, after the George Floyd Protests 2020, from Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository.

J. M. W. Turner, “Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhoon coming on” (also known as “The Slave Ship”), 1840. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia. Photo: Sanjay Suchak.

Historical timeline, Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia. Photo: Sanjay Suchak.

Memorial to Enslaved Laborers’ genealogical cloud of names of enslaved men, women, and children, including those whose names are unknown.

Protest by UVA’s Medical Center’s White Coats for Black Lives, June 2020. Photo: Sanjay Suchak.

Gathering of descendent community at Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia. Photo: Sanjay Suchak.