Abstract

This essay explores reparative design pedagogies to advance intersecting racial justice and climate goals through the case study of the “CoDesign Field Lab: Black Belt Study for the Green New Deal.” Through engaged community design processes with Afro-descendant communities in the Black Belt South, the design action research seminar sought to reimagine and future the region as fount and staging ground for a reparation-based Green New Deal. We examine the course design and setup—including relational infrastructures to deepen collaboration between regional youth and community elders and graduate students of urban planning, architecture, landscape architecture, and design studies—and the resulting future histories of reparative infrastructures for the Black Belt. The concluding discussion considers case implications for design pedagogies, including the importance of shifting away from knowledge bases and design-cultures predicated on whiteness and white supremacy, and supporting community-based processes of reparative design and reparations centering those who have directly suffered harm and their descendant communities.

Reparations are the act or process of making amends for a wrong. According to the United Nations, full reparations require restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of nonrepetition. International standards further designate the state responsible for the wrongful acts as obligated to meet the five conditions of full reparations and necessitate the participation and leadership of harmed persons in determining courses of repair, healing, and justice.Footnote1 In the United States, the reparations movement for slavery and its legacy of racial injustice is rooted in centuries of organizing and advocacy led by formerly enslaved people and their descendants.Footnote2 In 1783, Belinda Royall first petitioned the Massachusetts General Court for remuneration of her uncompensated labor by the slaver Isaac Royall, Jr. through pension payments. Thereafter, generations of African Americans and Black-led organizations—from the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief and Bounty and Pension Association (founded 1897) to the Movement for Black Lives (formed in 2014)—have sought redress from the federal government, states, cities, religious institutions, and colleges and universities for racialized expropriation and injuries. Reparations leaders have moreover appealed to the United Nations with petitions and communiqués demanding reparations from the United States government.

Since 2020, antiracist protests and reckonings in response to continued police violence and brutality towards Black Americans have renewed calls for reparations with widening public traction and salience. By fall that year, democratic presidential candidates debated reparations as a major campaign issue. In April 2021, HR 40, a bill seeking to establish a federal commission to study slavery reparations for Black Americans, progressed past the house committee for the first time since being introduced at every congressional session since 1989. At the subnational level, California became the first state to create a reparations task force in 2020. The next year, Mayors Organized for Reparations and Equity (MORE) launched as a national coalition with an active commitment to support federal reparations legislation, establish advisory commissions in their respective cities, and work toward developing and implementing reparations demonstration programs targeted to a pilot group of Black Americans in their communities. In 2021, Evanston (Illinois) became the first city to launch a Restorative Housing Program, which provides qualifying African American or Black residents with housing grants up to $25,000. Reparations measures have further identified land use (i.e., exclusionary zoning, redlining, urban renewal) and infrastructural sectors such as transportation (i.e., highway construction and transit divestment), education, health, and criminal punishment among avenues of racial harm and redress.

This essay explores possibilities for the built environment disciplines and professions to better align with reparations movements, in part, through pedagogical shifts oriented towards preparing architects and planners to work alongside community-based activists, organizations, and movements that are already leading the work. It focuses on the “CoDesign Field Lab: Black Belt Study for the Green New Deal,” an interdisciplinary design action research seminar offered at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in Spring 2021. Developed in collaboration with the Georgia-based Destination Design School of Agricultural Estates (DDSAE) and led by the author, the exploratory course sought to reappropriate design education to supplement and amplify existing reparative justice measures of centering those who have been harmed in repairing past harms, stopping present harm, and preventing the reproduction of harm. Course participants reimagined and futured the Black Belt Region as fount and staging ground for a reparation-based Green New Deal—in part, through virtual teamwork between regional youth and community elders and graduate students of urban planning, architecture, landscape architecture, and design studies. While examining infrastructural assets, mobilizations and struggles, and future pathways for just transitions, the course extended the DDSAE’s reparative justice framework of elevating Black women’s leadership, youth voices, and cultural paradigms of community-based caring and sharing in the Black Belt.

The following section presents an overview of the Black Belt South as it relates to the case for racial and climate reparations before considering design politics for just transitions and reparations. We next present the course design and setup for CoDesign Field Lab along with relational infrastructures for deepening design action research with the DDSAE. This entailed designing course lectures and exercises to corral research and data in ways affirming the hopeful desires and practices of communities in the Black Belt region and combining with speculative planning and design techniques that excavate the past, present, and future possibilities of environmental sustainability and climate resilience in the Black Belt. We also conducted an AfroFuturing workshop and followed up with codesign methodologies to create future histories of reparative infrastructures for the Black Belt. The concluding section discusses case implications for reparative design pedagogies.

View from the Black Belt South

Originally named for its dark, alluvial soil, the Black Belt Southern region of the United States comprises nearly 200 noncontiguous counties stretching from eastern Texas to Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia with large African American populations (forty percent or more).Footnote3 Guilefully and violently taken from Indigenous nations and tribes by European settlers, the area functioned as the seat of cotton slavery and the plantation economy from the 1820s. Built up and enriched through the labor of enslaved people of African descent, the region was dominated by a gilded plantocracy whose interests fundamentally shaped the American political system and whose transatlantic trade relations laid the foundations for modern-day global capitalism.Footnote4 The next two centuries were a tumultuous period spanning the Civil War in which the “general strike” of enslaved Black workers sealed Union victory; broken promises of Radical Reconstruction by which federal withdrawal through the 1877 Hayes-Tilden compromise soundly reversed Black gains (in electoral participation, political leadership, labor rights, and property ownership); the onset of Jim Crow; the ensuing Great Migration of an estimated six million African Americans from the region; the rise of the Civil Rights movement; and racial politics of backlash.Footnote5 Yet the region remains home to many African American and Black communities, including return migrants from northern and western points of origin.

The Black Belt South is a critical location from which to consider the historical pertinence and imperative of reparations. It was there that Union Army General Sherman issued Special Field Order #15, giving 40,000 former slaves forty acres each of captured land from South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida—a measure later reversed by President Andrew Jackson, who restored property to its former Confederate landowners. Over time, racial injuries and harms by federal, state, and local governments have grown and accumulated to include discriminatory access to New Deal and postwar policies for rural electrification, farming loans, housing, education, and business loans.Footnote6 African American-majority Black Belt communities have disproportionately suffered exposure to polluting industries and toxic waste sites.Footnote7 Over the past four decades of federal retrenchment, public disinvestment from urban neighborhoods, and criminalization of poverty, they have also experienced undue burdens of policing and incarceration connected with the proliferation of all-purpose use of prisons as geographical solutions to social and economic crises.Footnote8 Across the country, racialized predatory lending fueled the 2008 housing crisis, which reversed Black homeownership gains and escalated property vacancies and abandonment while further consolidating real estate holdings among global banks. Meanwhile, African Americans in the region have continued to organize around establishing just claim to the share of national wealth derived through Black expropriation and demand capital transfers into African American and Black communities.

Anticipating climate futures from the Black Belt Southern region brings into relief the intertwinement of racial and climate injustices and urgency of reparations. Critically examining the modern history of built environment practices driving climate change, we can see varying inheritances of moral liabilities vs. claim rights across different groups. For instance, white preferences for segregated communities toxically combined with single-family home ownership, preferential mortgage lending (in white-only neighborhoods), and new greenfield developments to create sprawling metropolitan regions across the continent.Footnote9 Whites also overwhelmingly benefited from federal investments in new highways, universities and colleges, and defense industries,Footnote10 which manifested as a land-intensive and ecologically-extractive endeavor carrying devasting environmental consequences. With projected rises in annual temperatures and extreme heat events for the United States over the coming decades, many Black Belt communities are now situated at the front lines of climate change.Footnote11 Despite all the public attention paid to sea-level rise in coastal areas of the country, states like Alabama and Georgia actually face among the highest levels of climate vulnerability due to socioeconomic metrics and lack of government capacity to make preparations and respond to crisis events.Footnote12 Black Belt communities which are home to American descendants of slavery appear especially vulnerable in the face of systemic injustices and arguably merit reparations on both a racial and climate basis.

Design Politics for Just Transitions and Reparations

For design educators who seek to incorporate reparations frameworks into pedagogical approaches and practices, constructive views of reparations present particularly exciting alignments and opportunities. In Reconsidering Reparations, Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò conceptualizes common ways of approaching reparations.Footnote13 Harm-repair arguments focus on fixing present harms causally connected to or constituted by past harms based on welfare comparisons. Relationship-repair arguments focus on fixing damaged relationships between the aggrieved and aggrieving party following moral wrongdoing. Táíwò advances a third approach—a constructive view of reparations. As he defines it, reparations as a “world making perspective on justice is concerned with material and social resources, formal rules and norms, and also with informal patterns and attentions of care.”Footnote14 It is less concerned with definitions of harm or wrongdoing than with evaluating and transforming social structures and arrangements to be more just. That is, reparations serve to make tangible differences in the material conditions of peoples, address the core moral wrongs of transatlantic slavery and colonialism, and distribute benefits and burdens based on inheritances of moral liabilities vs. claim rights. Taiwo focuses the goals and ethos of the constructive view of reparations on climate justice, noting that both racial injustice and the climate crisis result from global racial empire and that the costs and burdens of climate change will only reinforce existing hierarchies and inequalities.

In considering how to operationalize the constructive view of reparations and finding entry points for practice, designers can take cues from Damian White’s essay, “Just Transitions/Design for Transitions: Preliminary Notes on a Design Politics for a Green New Deal.”Footnote15 White makes a case for politicized modes of design to help expand just transition methodologies and practices in future-oriented, constructive directions. He identifies gaps within just transition movements and policy platforms in terms of “the future-oriented political imaginaries, the cultural and material aesthetics, the modes of work/life balance, and the modes of making and doing that might inform post-carbon futures.”Footnote16 White sees synergies with design education components of “prototyping, prefiguring, speculative thinking, scenario-building, doing things differently, failing, and then starting all over again.”Footnote17 However, to overcome Euro-American centricity in design futuring for the pluriverse additionally requires learning from Indigenous, African American, and Latinx design traditions and building practices along with decolonial designers to pluralize the knowledge base and construction of design-cultures for disassemblage, repair, maintenance, and reuse.Footnote18 It necessitates careful consideration of what kinds of modes of life—forms of urban design and culture, consumption, work and leisure, aesthetics and pleasure—we might choose to sustain as they relate to low-carbon/high-quality futures. White also calls for relational, movement-based design approaches:

What is needed, then, is less endless evoking that we are at ‘five minutes to midnight’ or that ‘tech/automaton will save us,’ and more hybrid, multi-scalar, and programmatic accounts that can think about the modes of state-led action and grassroots innovation, the forms of social institutionalization, democratic design and planning and modes of radical design futuring that can ally with protest, struggle and resistance to move a post-carbon politics forward. Footnote19

Such approaches to designing for just transitions can further inform design practices aligned with the constructive view of reparations, particularly given the interrelations between just transitions and reparations. Just transitions are principles, practices, and processes of divesting from the extractive economy based on a consumerist and colonial mindset, extraction of nonrenewable resources, labor exploitation, enclosure of wealth and power, and militarism. They also entail investing in regenerative economies based on caring and sacredness mindsets, resource regeneration, cooperative work, ecological and social well-being, and deep democracy. As the Climate Justice Alliance emphasizes, “The transition itself must be just and equitable; redressing past harms and creating new relationships of power for the future through reparations.”Footnote20 This suggests that corresponding design politics must actively reckon with the past, present, and future in seeking to make tangible differences in the material conditions of peoples, address the core moral wrongs of transatlantic slavery and colonialism, and distribute benefits and burdens based on inheritances of moral liabilities vs. claim rights. Besides multiple time scales, designers might also consider the roles and responsibilities of federal, state, and local governments in making reparations as they additionally develop strategies and tactics for just transition across varying issue areas and infrastructural sectors related to built environments.

Course Design and Setup

We now turn to the “CoDesign Field Lab: Black Belt Study for the Green New Deal” to examine how design pedagogies might incorporate reparations frameworks and reparative justice principles in practice. The interdisciplinary design action research seminar was offered at the Harvard Graduate School of Design over Spring 2021, an entirely virtual semester. It came at the invitation of Euneika Rogers-Sipp, cofounder and executive director of the Destination Design School of Agricultural Estates (DDSAE) based in the Black Belt Southern region of the United States. As an art and community design school, the DDSAE was creating spaces for Black Belt youth and community leaders to work with the cultural sector to enhance intergenerational access to traditional lands and resources in the Black Belt region and promote environmental sustainability and climate resilience. As Rogers-Sipp sought out opportunities to collaborate with faculty around design research and education, the remote instruction and learning requirement amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic became an enabling factor. Combining participatory action research with speculative planning and design methods, the CoDesign Field Lab would be able to work directly with the DDSAE throughout the semester. Course participants would gather, analyze, synthesize, visualize, and narrate data to help make the case for, reimagine, and future the Black Belt Region as fount and staging ground for a reparation-based Green New Deal led by place-based activists and frontline communities with a focus on critical infrastructures.

The CoDesign Field Lab and Destination Design School jointly enrolled in the Green New Deal SuperStudio, an open call by the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) for designers to translate the core goals of the Green New Deal—decarbonization, justice, and jobs—into design and planning projects with regional and local specificity. Coalescing mobilizations for just transitions with growing interest among built environment disciplines and professionals in designing for transitions, the Green New Deal SuperStudio invited designers to support the “opportunity for change.” Since the United Nations announced the Global Green New Deal in 2008, the Green New Deal had surfaced in various US political campaigns and policy debates, generally as ambitious, wide-ranging, and transformative measures to shift from the current extractive economy to a regenerative one. Building on decades of mobilizations for just transitions and mounting youth activism by the Sunrise Movement, Representative Ocasio-Cortez (NY) and Senator Markey (MA) introduced HR 109—Recognizing the Duty of the Federal Government to Create a Green New Deal—in February 2019. President Biden made climate change and infrastructure investments key issues and upon election, struggled to translate campaign promises into legislation and funding. The LAF appealed to designers to utilize their unique training to help give form and visual clarity to the scale, scope, and pace of transformation implied by the Green New Deal.

The CoDesign Field Lab and the Destination Design School approached the Green New Deal as a substantive means to redress past harms and create new relationships of power for the future through reparations. We not only sought to translate HR 109’s goals of decarbonization, justice, and jobs into design and planning projects, but also HR 40—Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act—and the Climate Justice Alliance’s Just Transition Framework. The CoDesign Field Lab (CDFL) was structured around three course exercises, which would leverage the interdisciplinarity of the fourteen enrolled master’s students (from urban planning, landscape architecture, architecture, and design studies) and generate outputs that would be widely sharable, legible, and salient across different audiences. The first was to create a digital storymap examining twenty-first century dilemmas, movements, and possibilities for just transitions in the Black Belt. This included mapping community assets and opportunities present in the region in addition to documenting conditions and drivers of racial injustice. For the second exercise, students would map environmental, climate, and racial justice organizations engaged in works of collective repair as well as agenda setters, decision makers, and resource holders across different sectors, agencies, and organizations with significant stake and influence in Green New Deal planning and implementation at the regional scale—along with their power dynamics. The final exercise was a future history of a reparative Green New Deal that centers the identities and ingenuities of Black Belt communities along with existing leadership and mobilizations around just transitions in compensating for and healing past harms as well as radically repairing forward. The future history could take the form of a graphic novel, video, zine, or summary report. The three exercises would be conducted in self-selected teams, each focused on one of five infrastructural topics for the duration of the semester (mobility + access, food + fiber, housing + buildings, energy + waste, and water + climate).

Infrastructures of Sistering and Deepening Design Action Research

Undergirding the collaboration between the CoDesign Field Lab and the Destination Design School of Agricultural Estates was a shared design epistemology and methodology of sistering, which in architectural terms means to affix a beam or other structural member to another as a supplementary support. The teaching team included the author and Euneika Rogers-Sipp along with the DDSAE program manager, a special advisor to the DDSAE, and two course teaching assistants, who were also enrolled as students in the CDFL. Together, the team planned and adapted the course through weekly coordination meetings going into the semester and throughout. The team also wove together an interdisciplinary network of course mentors with expertise in neighborhood and urban planning, public art, social and economic justice, AfroFuturism, strategic communications, historic preservation, public health, and education, who would share their diverse expertise with the class through panel presentations, instructional videos, and workshops as well as desk crits with the student teams. The team made sure to prioritize community activists and movement builders who were based in the Black Belt region.

The design action research approach of the seminar course initially focused on case-making to amplify work that the Destination Design School and their network of community and movement-based organizations in the Black Belt region were already doing, and on creating storymaps and stakeholder power maps that could further inform the design education and activism of DDSAE’s youth and community leaders. During a synchronous in-class discussion a month into the semester, students raised the question of working directly with DDSAE youth elders, a term used by the organization to acknowledge the wisdom, foresight, and leadership of young people within multigenerational families and communities. Revisiting the idea over a series of weekly coordination meetings among the teaching team, Rogers-Sipp expressed interest and willingness, noting the resonance with DDSAE’s supplementary educational programs centering intergenerational legacy, community wealth-building, and equity-centered design frameworks in the Black Belt region. She reached out to DDSAE youth elders and community elders who had previously taken part in the organization’s immersive design curriculum and education programs targeting members of African diasporas (African American and more recently-arrived Black communities) in the Black Belt region. As they responded positively, we decided that for the final future history exercise, each of the five teams would be joined by youth and community elders (nine in total) from the Destination Design School over a month and half. This required applying for funding through the newly created Racial Equity and Anti-Racism Fund at the Harvard Graduate School of Design to cover honoraria for youth and community elders along with course speakers and mentors.

The guiding vision for the blended team work on future histories was to create a generative design practice co-led by youth that affirms personal identities, ancestral knowledge, and creativity while introducing infrastructure topics, the just transition framework, and reparative justice principles. In preparation, the DDSAE partners developed a parallel curriculum for the youth elders, ranging from age nine to seventeen, who would meet separately on Saturdays by Zoom, and assigned the youth along with a few family elders to the five teams based on personal interests and alignment. With the two teaching assistants, the author structured an agenda and schedule for joint learning and teamwork between the CDFL students and DDSAE youth elders. The teaching team also gathered individual biographies from the students, youth elders, teaching team members, and course mentors, all of whom further shared skills and knowledge offerings, and shared the bios with all CDFL students and DDSAE youth and family elders. To ensure all participants felt supported throughout the experience, DDSAE created a Guide to Nourish in conversation with youth, to which CoDesign students responded with Youth Elder Engagement Guidelines. For example, the youth elders requested movement breaks and learning quality over quantity, and teaching assistants for the CoDesign Field Lab responded by incorporating stretch activities and free-drawing games in agendas.

Codesigning Future Histories

Across architecture, urban design, and planning practice, design charrettes are widely used to bring people together across different backgrounds and disciplines as well as with local communities to explore design ideas and options for a given area. While their design and idea-driven qualities suited our goals of codesigning the future history, we sought a more culturally resonant approach to participatory design that was racially affirmative (as opposed to color-blind) and intergenerational. The team also wanted to ground the work in Black-led struggles and social movements. This was in part to counter damage-centered narratives “that [establish] harm or injury in order to achieve reparation” yet carry long-term repercussions of rendering marginalized communities depleted and broken.Footnote21 We aimed for fuller, depathologizing, desire-full imaginings and invocations that were life-affirming and community-centered with respect to a reparative Green New Deal. Working with the Fathomers,Footnote22 the teaching team developed an AfroFuturing workshop, “Afro-Rithms from the Future: A World-Building Game Centering Race and Antiracism,” to serve as a communal medium for generating creative ideas for design interventions. The world-building game applied the Destination Design School’s reparative justice framework, creating an “inspiration card” featuring youth eldership and “tensions cards” featuring Black women’s leadership (based on empathic and shared decision making), and cultural paradigms of community-based caring and sharing (where the monetary currency is based on building and strengthening community).

Through joint participation in the AfroFuturing workshop, the blended teams gained introduction to speculative futuring concepts and tools. Thus kicking off the future history exercise, the blended teams continued to cocreate future artifacts and scenarios for their respective sectors over the next month and half. After the AfroFuturing workshop, the CDFL students posed to the youth elders a series of questions to better understand existing values and practices around environmental sustainability and climate resilience. Questions included: “Who in your family and community is a leader in conserving environmental resources and caring for others? How would you reimagine and design an aspect of your sector to ensure this leader is healthy, safe, and nourished?”Footnote23 Within a week, the youth elders came back with written and drawn responses to questions—relayed by the teaching team via text, email, and Google doc— and their CDFL teammates incorporated these focal ideas and inputs into the future histories of mobility + access, food + fiber, housing + buildings, energy + waste, and water + climate for the Black Belt region. In so doing, CDFL students were instructed to weave in historical sources and multifaceted data to ensure the future histories were recompensing for historical and systemic injustices and healing forward in creative, joyful, and care-centered ways. Following two more joint teamwork sessions—one during a CDFL class and another during a DDSAE youth elder meeting—the CDFL team members received feedback on the future history projects through a pinup session with Rogers-Sipp and the author, and made improvements as requested.

On the final day of class, the five teams presented and received feedback on their future histories, with course mentors and DDSAE associates and supporters in attendance. Each team began with an introduction from a DDSAE youth elder and proceeded with a presentation of the future history by one of the CDFL students. CDFL and DDSAE teammates were listed as coauthors, and the CDFL students highlighted specific inputs and inspirations from DDSAE youth elders during the future history presentations. The mood was celebratory. After each of the five teams shared their future history and received feedback, the event ended with a round of reflections on their codesign experience. Over the next two weeks, CDFL students finalized all three course outputs, which were uploaded to a public-facing website for use by the Destination Design School. The five future histories of reparative infrastructures for the Black Belt were further submitted alongside DDSAE’s visual summary of our relational infrastructures of sistered design to the Green New Deal Super Studio upon spring semester’s end.Footnote24 That fall, the Landscape Architecture Foundation selected the sistered design work between the CoDesign Field Lab and Destination Design School of Agricultural Estates as part of their curated set of fifty-five projects—among 670 submissions for the Superstudio. The Black Belt future histories were featured as part of the Superstudio Showcase: Reflections from a Year-Long Open Call in November 2021. It also went on display as part of the Grounding the Green New Deal Summit at the National Building Museum in April 2022.

Future history of housing and building

The housing + building team’s future history took the form of a dispatch zine from 2050. Through the historic Green New Deal and 21st Century Homestead Act, housing shifted from a commodity to a human right, and incorporates multi-generational housing opportunities, sustainable and healthy living environments, and care, repair, and maintenance-related union jobs that are targeted to historically marginalized groups. Debt-free home ownership opportunities and support programs for heir’s properties help Black Belt families—and others who fled racial violence and discrimination as part of the Great Migration— to gain intergenerational wealth and stability.

Future history of food and fiber production

The food + fiber production team created an illustrated short story. Starting in 2100, a 70-year retrospective encompasses a young woman’s enrollment in a historically Black college, paid internship with family-owned farms involving a mobile farming school modeled after George Washington Carver’s original invention, creation of a local farm registry for Black and Brown fiber and food growers, deals with anchor institutions to engage in direct sale and shift industry supply chains, and legislating government funding programs to support regional producers and consumers. Old mall buildings transform into food and fiber hubs for the multigenerational federation of farm and cottage producers, featuring solar panels and plants watered with gravity systems, drop irrigations, and other methods to reduce waste, save energy, and use as little water as possible.

Future history of energy and waste

The energy and waste team created a video dispatch from the future multi-campus Destination Design School situated along the Digging DuBois trail, which serves as a community hub and clean energy model to public schools around the nation. Funds from the American Jobs Plan and a larger public policy and investment package under President Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez along with continued organizing by Southern Movement leaders expand the carbon-neutral and care-centric education model. Intergenerational energy councils across the country govern federal expenditures, prioritizing historically marginalized communities, and working with energy cooperatives to shift to clean energy and eliminate energy black outs. Both energy councils and cooperatives are unionized—affiliated with the United Care Workers of America.

Future history of water and climate resilience

The water and climate resilience team created a manual for lifelong learning to promote safe drinking water, sustainable systems, healthy waterways and ecosystems, water management, and clean industrial technology. The year is 2070 and the Green New Deal enabled policies and programs that create family-sustaining jobs focused on testing public water sources, educating the public on resource management, and conducting public science on watersheds. Floods and storm events are opportunities to collect water for gardens, drinking, and agricultural production. Healthy waterways and ecosystems incorporate regional Afro-Indigenous foodways and cultivation techniques from Gullah-Geechee communities. Accessible and recyclable wastewater management systems incorporate water-cleaning plants as part of small-scale community interventions that simultaneously improve air quality. Clean industrial technology helps convert formerly hazardous water bodies into renewable energy sites.

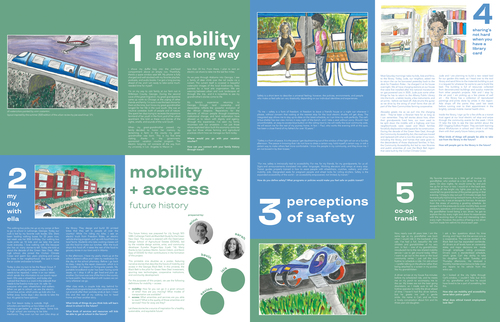

Future history of mobility and access

The mobility and access team presented their infrastructural vision on a poster encompassing 5 different narrative vignettes and watercolor art. One story focused on leisure and recreation as a right, complete with government travel vouchers and a high-speed rail network along with electric car share for last-mile connections. Other vignettes feature regional mobility services being provided through electrical vehicle sharing and driver cooperatives, neighborhood ambassadors, repair scouts, and bike mechanics helping people get around actively and safely, as well as libraries loaning everything from books to building and farming tools, digital tablets, and musical instruments.

Implications for Reparative Design Pedagogies

To make reparations is to repair, heal, and make whole a divided nation and people whose spatial segregation and segmentation correspond with metropolitan sprawl, environmental devastation, and now climate crisis. Reparations for slavery and its legacy of racial injustice is not exclusively an African American issue but rather one that widely concerns those who have inherited illicit advantages and cumulative disadvantages alike on racialized bases. To seek reparations is to actively reckon with the past, present, and future. It requires tracing back harms to particular causes and responsible parties and establishing claims to wrongful injuries. It also requires stopping harm in the present and guaranteeing their nonrepetition in the future by reimagining and transforming harmful systems, institutions, and practices. Reparations movement leaders such as the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America and National African American Reparations Commission have identified infrastructural systems like education, health, criminal punishment, and information-communications among key areas of racial harm and redress.Footnote25 At the subnational level, state and local reparations measures additionally focus on land use, housing, transportation, and other infrastructural sectors in which we work. Following their lead, the built environment disciplines and professions can organize and advocate for reparations across issue areas, domains, and sectors in which we work.

As Damian White points out, core components of design education lend themselves well to design futuring postcarbon built environments and modes of collective life. The interdisciplinary, synthetic, and speculative nature of design also appears compatible with Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò’s constructive view of reparations—including connecting the political- economic, historical, and ethical dimensions of reparations work with imaginative and transformative scenarios. However, only by shifting knowledge bases and design-cultures predicated on whiteness and white supremacy culture can designers help envision modes of disassemblage, repair, maintenance, and reuse that are relevant and accountable to those who have directly suffered harm and descendant communities.Footnote26 For the CoDesign Field Lab, this required supplementing the Green New Deal framing of the course with the just transition framework, HR 40, and DDSAE’s reparative justice framework. We intentionally set up the storymap exercise to attend to community assets and opportunities as well as conditions and drivers of racial injustice present in the region and the stakeholder power mapping exercise to identify regional environmental, climate, and racial justice organizations alongside key agenda setters, decision makers, and resource holders. We incorporated the AfroFuturing workshop for a more culturally resonant approach to participatory design, and followed up with continuing interactions and exchanges among the blended teams that centered family and community traditions from the Black Belt.

While designing for reparations must be handled with care, the speculative work that captures the hope, visions, and wisdom of disenfranchised communities can be highly fraught so as to necessitate direct participation. Standpoint theorists, commonly found among Black radicals, decolonial activists, and feminists, posit that there is no objective world that is universally knowable but only embodied social situations and corresponding standpoints.Footnote27 Those situated at the margins have particular insights on infrastructure systems that are often invisible to dominant groups who are blinded by comfort. These systemic insights can fuel radical openness and possibility that hold promise for reparative design. Infrastructures of “sistering” such as weekly coordination meetings, network of interdisciplinary course mentors (including community activists and movement builders from the Black Belt region), “Guide to Nourish” by youth elders, and “Youth Elder Engagement Guidelines” by CDFL students structured our terms of mutual engagement and collaboration. These not only set expectations and boundaries for interacting and cocreating but also clarified respective strengths and the importance of working together. Among the greatest rewards of “sistering” was the response from participants. One of the graduate students stated in her video message to DDSAE teammates:

You shaped so much of our project. Before we got to speak with you both, we were thinking, honestly, [in a way that was] kind of boring! We had ideas about how to change the food and fiber sector but nothing as visionary as what you provided.… Every time we met with you, you provided so many ideas and enthusiasm…

Sharing her reflections on the course, a DDSAE youth elder stated:

This type of experience speaks to the type of education I seek to receive in the future. It’s very hands on, creative, and concrete. It has that duality that I really look for and the perspectives I gained from people in my sector and hearing from other sectors is important to my understanding of my world.

The quotes speak to mutual expansion of understanding and imagination.

Ultimately, design politics for just transitions and reparations will not originate from dominant design institutions and spaces. Reparative design practices and acts of collective repair will no doubt continue to be led by the abolitionists, activists, and artists who have long conjured futuristic visions that serve as alternatives to the unjust social and material conditions of the world and whose practices are rooted in place and community. It was only at Rogers-Sipp’s invitation and through the ensuing call and response that we sought to retool and reformulate design education and training in ways that centered the identities and ingenuities of Black Belt communities in designing for just transitions and reparations. Radical design futuring that allies with protest, struggle, and resistance to move postcarbon politics forward has little use for binaries between social mobilizations and design corollaries that render movement builders and designers mutually exclusive entities. Rather, we must dismantle barriers of entry to design disciplines and professions while simultaneously realigning our cultures, methods, and pedagogies around reparation and care—social and ecological. Nor should universities be the primary spaces of design pedagogy and instruction. Only with community-based processes of reparative design and reparations centering those who have directly suffered harm and descendant communities can we begin to overcome our epistemic and methodological limitations and free ourselves from the current sociopathic trajectory of planetary destruction.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to Euneika Rogers-Sipp for her vision and sistership; to Cynthia Deng, Thandi Nyambose, Scarlet Rendleman, and Mina Kim for their course coordination and teaching support; and to all the youth and student participants of the CoDesign Field Lab for their creative contributions. Additional thanks to Jeana Dunlap, Syed Ali, Dorian McDuffie, Dr. Robert Tucker, Lanona Lee Jones, Stephanie Guilloud, Emery Wright, Dr. Lonny J. Avi Brooks, Ahmed Best, Chinelo Ufondu, and Lacey Wozny for their course mentorship, and to Naisha Bradley for the funding support.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lily Song

Lily Song is an urban planner and activist-scholar. Her research and scholarship focus on the relations between urban infrastructure and redevelopment initiatives, socio-spatial inequality, and race, class, and gender politics in American cities and other decolonizing contexts. Her work both analyzes and informs infrastructure-based mobilizations and experiments that center the experiences and insights of historically-marginalized groups as bases for reparative planning and design. Song was previously a Lecturer in Urban Planning and Design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), where she was Founding Coordinator of Harvard CoDesign, a GSD initiative to strengthen links between design pedagogy, research, practice, and activism. She holds a PhD in Urban and Regional Planning from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MA in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of California— Los Angeles, and BA in Ethnic Studies from UC Berkeley.

Notes

1 “Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law,” United Nations General Assembly, 2005, https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/basic-principles-and-guidelines-right-remedy-and-reparation.

2 Robert L. Allen, “Past Due: The African American Quest for Reparations,” The Black Scholar 28:2 (1998): 2-17; Martha Biondi, “The Rise of the Reparations Movement,” Radical History Review 87:1 (2003): 5–18; Adjoa A. Aiyetoro and Adrienne D. Davis, “Historic and Modern Social Movements for Reparations: The National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’Cobra) and Its Antecedents,” Tex. Wesleyan L. Rev. 16 (2009): 687.

3 Dale W. Wimberley, “Quality of Life Trends in the Southern Black Belt, 1980–2005: A Research Note,” Journal of Rural Social Sciences 25:1 (2010): 7; Rosalind Harris and Heather Hyden, “Geographies of Resistance within the Black Belt South,” Southeastern Geographer 57:1 (2017): 51–61.

4 See Robin L. Einhorn, American Taxation, American Slavery (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008); Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (New York: Vintage, 2015).

5 See Clyde Woods, Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta (London: Verso Books, 1998); Clyde Woods, Development Drowned and Reborn: The Blues and Bourbon Restorations in Post-Katrina New Orleans, vol. 35 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2017).

6 Ira Katznelson, When Affirmative Action was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America (New York: WW Norton & Company, 2005).

7 See Robert D. Bullard, Unequal Protection: Environmental Justice and Communities of Color (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1994); David Naguib Pellow, Garbage Wars: The Struggle for Environmental Justice in Chicago (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004).

8 Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California, vol. 21 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007).

9 Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987).

10 Lisa McGirr, Suburban Warriors: The Rise of the New American Right (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2002).

11 K. C. Binita, J. Marshall Shepherd, and Cassandra Johnson Gaither, “Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment in Georgia,” Applied Geography 62 (2015): 62–74.

12 Solomon Hsiang, Robert Kopp, Amir Jina, et al., “Estimating Economic Damage from Climate Change in the United States,” Science 356:6345 (2017): 1362–69.

13 Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Reconsidering Reparations (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022).

14 Táíwò, Reconsidering Reparations, 97.

15 Damian White, “Just Transitions/Design for Transitions: Preliminary Notes on a Design Politics for a Green New Deal,” Capitalism nature socialism 31:2 (2020): 20–39.

16 See pg. 28, White, “Just Transitions/Design,” 9.

17 White, “Just Transitions/Design,” 33.

18 See Arturo Escobar, “Designs for the Pluriverse,” in Designs for the Pluriverse (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018).

19 White, “Just Transitions/Design,” 3.

20 “Just Transition: A Framework for Change,” Climate Justice Alliance, 2022, https://climatejusticealliance.org/just-transition/.

21 Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79:3 (2009): 409–28.

22 Fathomers is a creative research institute dedicated to producing sites and encounters that challenge people to live and act differently in the world. Afro-Rithms from the Future is a group game and card deck developed by Afrofuturist Podcast coproducers Ahmed Best and Lonny Brooks in collaboration with game designer Eli Kosminsky. Fathomers is supporting Brooks, Best, and Kosminsky in the ongoing public play-testing and refinement of the game for eventual public release and distribution as a school curriculum tool.

23 Other questions were: If you were in charge of creating a Green New Deal that allows your family and community to thrive together with other species on the land, what is something you would fight against? What is something you would fight for? What kinds of jobs would you create to help humans live healthier, happier lives? And what kinds of jobs would you create to help animals, plants, and their habitats? Think about how pollution affects your sector. How would you get rid of or reduce this pollution? What methods or technology would you use?

24 The CDFL submitted the future history research and design outcomes, while the DDSAE submitted design boards illustrating the codesign process that informed and resulted in the overall design outcomes of the sistered collaboration.

25 “Preliminary Reparations Program,” National African American Reparations Commission, 2015https://ibw21.org/docs/naarc/NAARC_Preliminary_Reparations_Program.pdf; “Injuries: The Five Injuries of Slavery Defined,” National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, 2022, https://www.aboutreparations.org/the-five-injuries-of-slavery-defined.

26 See Rashad Akeem Williams, “From Racial to Reparative Planning: Confronting the White Side of Planning,” Journal of Planning Education and Research, 2020: 0739456X20946416.

27 Maksim Kokushkin, “Standpoint Theory is Dead, Long Live Standpoint Theory! Why Standpoint Thinking Should Be Embraced by Scholars Who Do Not Identify as Feminists?,” Journal of Arts and Humanities 3:7 (2014): 8–20; Julian Go, Postcolonial Thought and Social Theory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).