Abstract

Death takes up space, but not all bodies have clear access to it. Muslim Americans routinely face prejudicial, and often arbitrary, community and institutional opposition to proposals for Islamic cemeteries. These proposals intend to address the overwhelming deficit of local denominational plots, the desolate conditions of their existing death spaces, and typological collisions with the nation’s dominant white-Christian-capitalist burial paradigms. Using both literature and cartographic information, this article contextualizes obscured present-day conflicts within the settlement history of Muslims in America to reveal the entrenched operations—and consequences—of space being exploited to negate the diaspora’s sense of belonging and dispossession of place.

Editor’s Note: This piece was invited and did not undergo blind peer review

Death takes up space, but not all bodies have clear access to it. We are all a delicate yet mundane assemblage of correlative chemical elements. Yet some bodies, in life and in death, are bad—or rather, they’re treated that way. In the aftermath of the 2016 United States presidential election, New America, a civic-action think tank, conceived of the Muslim Diaspora Initiative to define the scale and scope of rising “anti-Muslim activities” across the country.Footnote1 Of the total 763 reported cases between 2012 and 2018, a subset of this research collated incidents of Muslims in the US routinely facing prejudicial, and often arbitrary, institutional and community opposition to proposals for Islamic cemeteries. These proposals intend to address the overwhelming deficit of local denominational plots and the desolate conditions of their existing death spaces. Several elements of their procession—from prescribed burial within 24 hours to directional plot placement towards Mecca to differences in material applications—collide typologically with the nation’s dominant language of Christian burial paradigms. The journey towards building new Islamic cemeteries in expression of their communities finds Muslims confronting a constructed otherness.

Supplications

In 2013, the SpencerMagnet reported on Kentucky’s Bullitt County Board rejecting a permit for an Islamic cemetery, and how the decision was met with cheering from the 125 neighbors in attendance. Board members stated that the cemetery wouldn’t fit into the “harmony of the neighborhood.”Footnote2 Community members expressed fear for their family’s safety and that it would be “a slap in the face” to their ancestors.Footnote3 A saddened representative of the project said that the response demonstrated the need for “aware[ness] of the Muslim community, our needs, and basically who we are.”Footnote4 In 2017, The Washington Times reported on Minnesota’s Chisago County Board denying a permit to the Islamic Community of Bosniaks to build a cemetery—despite them having approval from the Planning Commission and the unused plot being zoned for burial. Rural residents adjacent to the land had opposed the project because of the Muslim neighbors it would bring.Footnote5 After the Department of Justice got involved, to uphold laws protecting religious land use, the board was compelled to reverse its decision. In 2016, WBUR reported on residents of Dudley, Massachusetts strongly opposing an Islamic cemetery proposal, citing concern about water contamination due to the absence of coffins or embalming, fear of hearing “crazy music” and devaluation of neighboring properties. During a zoning meeting, a resident testified to applause: “Put it in your backyard. Not mine.”Footnote6 The Department of Justice launched investigations into the matter but the project was later abandoned. Dr. Amjad Bahnassi, a Syrian immigrant and citizen of Dudley, stated during an interview for the New York Times: “I’ve been here since 1983. I don’t deserve to die here?” He travels to visit his son’s grave at the nearest Muslim cemetery 60 miles away in Connecticut, which is reportedly quickly reaching capacity.Footnote7 These three cases represent a cross section of the myriad concerns ubiquitous across the US. Aside from barbed remarks—like countering statements about the long drives to neighboring states’ cemeteries with “well, the ride from Afghanistan for a dead soldier is about 14 hours”Footnote8—people were willfully misinformed about Islamic rites and rituals (). For instance, embalming is restricted because it defiles the body for purely cosmetic purposes and contributes to the chemical contamination of soil. Caskets are limited to avoid material luxuries in death and allow the body, wrapped in natural biodegradable fabrics, to easily merge with pure earth. Loud displays of grief are strongly discouraged because it curtails the natural cycle of life and peace found in death. The subtext of such weaponized ignorance, disguised as legitimate concern, is the persistent belief that Muslims in the US should be prevented from having the same rights as everyone else because they do not belong within the established framework of American identity.

Figure 1. “Funeral Procession,” Folio 35r from a Mantiq al-Tayr (Language of the Birds). Sultan ‘Ali al- Mashhadi & Farid al-Din `Attar, dated A.H. 892/A.D. 1487. Metropolitan Museum of Art, public domain.

This fight for rights is perhaps best illustrated by the recent civil suit All Muslim Association of America (AMAA) v. Stafford County. According to the public case file, AMAA owns the only Muslim cemetery in Virginia, located on a small parcel purchased in 1991 to provide affordable local burial assistance—particularly for Muslims without family nearby or financial security.Footnote9 In 2015, the AMAA projected that the cemetery would reach capacity in 2021 due to the growing regional population; the COVID-19 pandemic would later exacerbate the situation. So they purchased 25 acres of land with the approved notion of a cemetery—after completing geotechnical studies and neighbor permits to ensure that the property met the lawful requirements for its intended use. The Planning Commission, however, introduced additional ordinances ex post facto, in the hope of either rejecting the proposal or making it more difficult, costly, and time-consuming to proceed. The PW Perspective reported that Crystal Vanuch, chairperson of the Subcommittee, who lives across from the property, stated during a deposition that she “doesn’t want to see a [expletive] Muslim cemetery across from her and would rather die before she allowed her husband to be reminded of those people.”Footnote10 The case file details how the subcommittee orchestrated the vote date for preserving the obstructive ordinances on the major Muslim holiday Eid-al-Adha to prevent AMAA representatives from attending.Footnote11 Following a lawsuit by the Department of Justice against the County—which Stafford County settled for $500,000—the cemetery was finally approved in 2021.Footnote12 Still, it can’t compensate for the Muslim bodies that have gone uncared for during the six years of legal disputes—or the aftereffects of hearing neighbors regularly make inflammatory comments about Muslims giving children cancer by stacking up nearly “100,000 bodies” next door.Footnote13

I start with this verbose regurgitation of select reports and exchanges to demonstrate the austerity in which the community is addressed, to connect several disparate local news sources, and to illustrate that this is a pattern worthy of cognizance. In the trickling ends of the pandemic, the US holds steady as the country with the most COVID-related deaths after having crossed the one million mark in May of 2022. Historically, pandemics pressurize the milieu of burial—its speed, space, and safety—but Muslims in the US have been negotiating these dimensions well before the pandemic, so for them, urgency is at an all-time high. There are similar studies to Muslim Diaspora Initiative that have been completed by groups like the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) and American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). While they provided rich insight into funded Islamophobic networks of prominent figuresFootnote14 or anti-mosque activity,Footnote15 neither categorically included cemetery-specific contexts. The New America study is also admittedly limited. To meet their research criteria, the publicly reported incidents had to be unequivocally driven by anti-Muslim ideology and included community pushback only when institutional pushback was also present. This obscured a tier of happenings that, while being legitimate acts of violence, were classified as speculative. While the research succeeded in providing a controlled index of reports, it does not interpret or situate the data in any social, political, or historical context that would otherwise reveal the depth of burial difficulties. It does not interrogate the settlement history of Muslims in the US to counter the core argument of a lack of belonging that is wielded to dispute claim to burial space; nor does it refer to the aeonic operations of what I refer to in this paper as an obstructive white-Christian-capitalist American cemetery model that has served the othering of Muslims. The purpose of this research is to embolden these disparate threads in existing scholarships and start weaving them together relative to spatiality to make the invisible, or unseen, visible. Using both literature and cartographic information, this article contextualizes obscured present-day conflicts within the deep settlement history of Muslims in the U.S. to reveal the entrenched operations—and consequences—of burial space being exploited to negate the diaspora’s sense of belonging and dispossession of place.

Ligatures of (Us) and (Them)

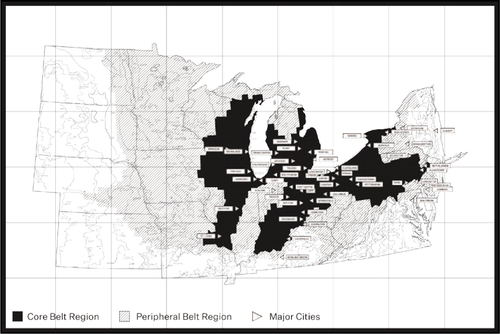

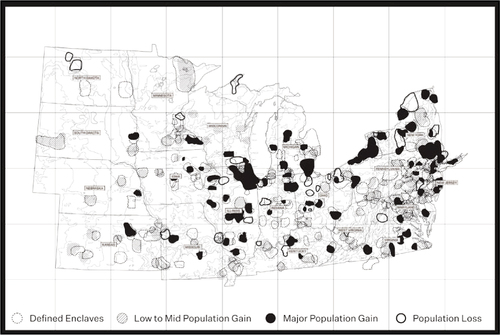

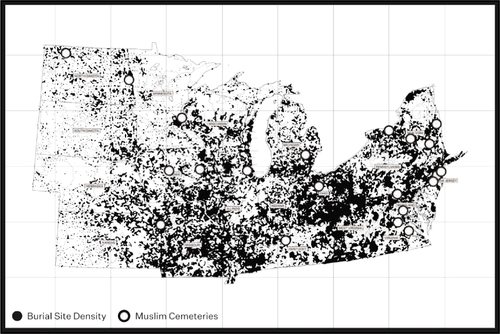

The sample region for this review was contained within the bleeding edges of the Rust Belt—definitively including Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Wisconsin, but often encroaching into Minnesota, the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa, Kentucky, Virginia, Maryland, Massachusetts, and New Jersey ()—for three reasons. Firstly, a religious landscape study by the Pew Research Institute in 2014 reported the largest concentrations of Muslims in America to be in Belt states such as New Jersey, New York, and Illinois, with Dearborn, Michigan serving the largest per capita Muslim population in the US ().Footnote16 Secondly, and unsurprisingly given the occupational densities, the majority of the New America reports opposing Muslim cemeteries were from the Belt.Footnote17 Thirdly, according to a compilation of 144,847 graveyards and cemeteries in the US via OpenStreetMap by Joshua Stevens in 2018, a large number of burial spaces are spread within the Belt—heightening the gaps in Islamic burial ().Footnote18 There are few exceptions to this focus, particularly for events preceding the Rust Belt’s industrial founding.

Figure 2a. The boundaries of the Rust Belt are not clearly or consistently defined so incorporating both core and peripheral regions, as well as identifying a group of major cities, provides comprehensive insight. Region mapping data by demographer Lyman Stone. Unless otherwise credited, all images Samiha Meem, 2020.

Figure 2b. Muslim settlement within the Belt. Population information is coalesced using three sources: Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) in 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010; Public Religion Research Institute (PPRI) 2020 Census of American Religion; and potential enclaves defined by local establishment of Islamic associations or mosques.

Figure 2c. As of 2020, the map depicts 144,847 US burial sites (mapping data by Joshua Stevens) contrasted with approximately 20–30 established Islamic cemeteries that service the entire region, as well as some external states, and vary vastly in size. The estimated plot capacity, based on land area and standard plot dimensions, was as little as 300 and an average of 4000.

Unmarked, Undeterminable

The first documentation of Muslims on US soil predates the founding of the nation itself—during Spanish expeditions. After landing shipwrecked alongside his Christian captors in 1527, a Moroccan slave named Mustafa Zemourri escaped towards the southwest and became a medicine man among Indigenous peoples.Footnote19 The Spanish would direct their understanding of the New World using Islam, with California deriving its name from a fictional eponymous island etymologically rooted in the term “caliphate.” Two hundred years later, Muslims made up an estimated one-third of the Africans who were stolen from Western shores and transported to build and be enslaved in the New World.Footnote20 Many were later converted to Christianity by slaveowners and religious missionaries under the threat of violence.Footnote21 While most Arabic names became Anglicized, you can still find traces of Fatimas and Ismaels in court documents, slave inventories, and death records. Numerous Muslim slaves and freedpeople pursued self-determination regardless—practicing their faith in secret—in the enclaves of Sapelo Island and St. Simons Island.Footnote22 Small groups of Muslims, mainly Black Americans, served in the 1775 Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the 1861 Civil War.Footnote23 During this period, Muslims did not have access to their denominational burials and would remain largely invisible.

The Naturalization Act of 1790, the first citizenship-by-naturalization law passed by the US, was limited to people who categorically fit into a definition of whiteness that was often conflated with Christianity and hostility towards Muslims.Footnote24 This would cast a shadow on immigration processes—with the US accepting mainly Western European, Chinese, and later non-Muslim African migrants well into the nineteenth century—with slow exceptions made in the context of labor exploitation during the Industrial Revolution. The first migration wave came in 1880–1924 with a plurality of immigrants settling in Belt states like Michigan, Illinois, and Ohio to work in US manufacturing factories.Footnote25 The region’s economic and industrial legacy stood rooted in the settlement of Muslim laborers, primarily Muslim Africans and Ottoman Muslims as well as Muslims from the Indian subcontinent and southeastern Europe.Footnote26

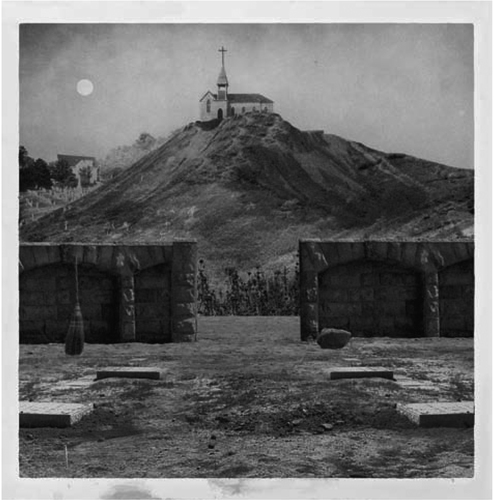

The early years of this period—post-Civil War and the Protestant religious revival of the Second Great Awakening—marked what Umar F. Abd‐Allah describes as a “time of secular numbness.” This spiritual skepticism, or rejection, constituted an unprecedented American interest in pursuing religious plurality. As part of the 1893 Chicago World Fair’s Parliament of Religions, Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb—an American convert—presented Islam to his Victorian contemporaries, to public fascination and disruptions by local Christian missionaries.Footnote27 He advocated that Islam was misrepresented to the US and insisted that his newfound faith did not negate his inherited, proudly adorned American identity. Abd‐Allah speculates that Webb’s missionary work had inspired Muslim immigrants to own their hyphenated identities, much as he had, and publicly organize around their faith. I note this because, while Webb and the Victorian religious scene brought a distinct national awareness of Islam, they did not alter much of the material conditions of Muslim death spaces. Similar to the past few centuries, Muslims had the smallest—or at least an undeterminable—burial representation within this first migration wave. Poor immigrants, including those who fought in World War I, were largely buried in mass, unmarked, or pauper graves which proves challenging when substantiating the identity, much less religion, of bodies (). In Till Death Do Us Part: American Ethnic Cemeteries as Borders Uncrossed, Rosina Hassoun reports that during field research into Arab-American burial patterns of this period, for which very little evidence exists, there were some traces of Arabic inscriptions on headstones for mass graves in Boston’s South End Burying Ground.Footnote28 At times, Muslims would violate the religious restriction against cremation as an alternative so they could still transport their family remains back to their country of origin and provide a modicum of respect in their death. If they could scrounge up the funds for local burial, families would be buried together within small, densely distributed plots, or even single graves.Footnote29 If they weren’t poor, they could afford to transport bodies overseas.

Interlude: Cemeteries as a White, Christian, and Capitalist American Institution

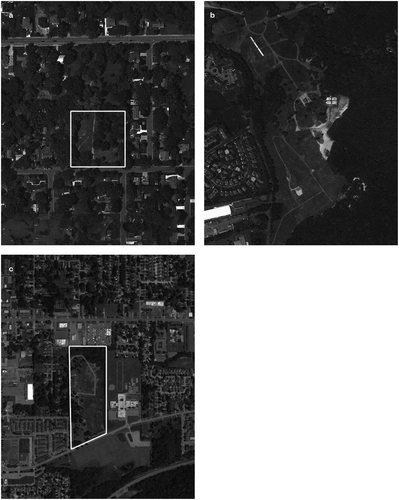

By the end of the 1920s, at least around 40,000 Muslim immigrants lived in the US, with much of the burial landscape in the nation having already been shaped.Footnote30 Death became professionalized—managed by dedicated workers rather than members of the community—and withdrawn from the heart of the US city between the eighteenth and late twentieth centuries following widespread concerns over public hygiene.Footnote31 Taking explicit precedence from the metropolitan garden cemetery Père Lachaise, located on the edge of Paris with garden arrangements without social or economic classifications, the US would undergo a shift in its death spaces, from church graveyards to garden cemeteries.Footnote32 This is primarily observed within the industrial region of the Rust Belt, where the first, and nationally defining, cemeteries were designed and built (). Of the nine cemeteries on the National Historic Landmark registry, seven are within the Belt. Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery, established in 1831, was the nation’s first garden cemetery. Following Père Lachaise most closely, Mount Auburn was placed on the outskirts of the city in a vast scenic landscape and became the city’s chief tourist attraction.Footnote33 While intended as a nondenominational cemetery to serve all communities, it became infused with Christian insignia in the desire to establish a distinct national and religious identity.Footnote34 Mount Auburn became the quintessential American cemetery, inspiring both cemeteries and public parks for years to come. For example, Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery—the first to gain National Historic Landmark status in 1998— was founded in 1836 and considered a public civic institution for people to enjoy refined landscapes that were once exclusive to the wealthy.Footnote35

Figure 4. Greenwood Cemetery in New York, Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts, and Spring Grove Cemetery in Ohio. Image courtesy Samiha Meem.

Then, in 1855, the lawn-park cemetery model was designed for the redevelopment of Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio by Adolf Strauch. It included more manicured open spaces, nonobtrusive gravestones styles to prioritize views, and simplified maintenance procedures. However, in “For Interment of White People Only,” Kelly B. Arehart states that his key contribution was proposing the cemetery “superintendent.” Before this model, burial spaces in the US were composed of church graveyard sextons, gardeners, and embalmers with minimal power. The superintendent would not only manage the day-to-day operations per the tight restrictions designed by Strauch but direct the image of the cemetery in alignment with national Christian-American motives. This tightened the objectives established by Mount Auburn and inspired cemeteries from across the country to appoint superintendents. One of these superintendents, J.R. Gaudin, presented a paper at a 1908 convention for the American Association of Cemetery Superintendents that included suggestions for how cemeteries should be managed by others, denoting interment of white Christian, preferably Anglo-Saxon Protestant, bodies.Footnote36 One critically relevant suggestion was to emphasize the far-flung locale of cemeteries from manufacturing districts since it would dissuade people of color, immigrants, and the poor who lived in those cities and often lacked the means to travel long distances, from accessing the cemeteries.Footnote37 Additionally, people with lower incomes—who are often immigrants of color—couldn’t afford to meet the strict design regulations that would constitute expensive plot packages and gravestones, many of which would represent Christian iconography.Footnote38 Superintendents became cultural curators of belonging, enforcing the economic, racial, and religious hierarchies that could not be evaded even in death. This would prime and mark the final turn to the modern commercialized cemetery operated by private corporations, who own and manage chains of death spaces for profit.Footnote39 Under these corporations, the modern cemetery was privatized and was no longer a public space. Death, now commodified, fortified structural discrimination but also created a barrier between the cemetery and the city. This typological genealogy addresses how the cemetery quickly became an American institution—a white, Christian, and capitalist American institution, nonetheless—that made living on the razor’s edge of otherness commonplace for Muslims and anyone who did not match its narrow specifications.Footnote40

Pocket Cemeteries

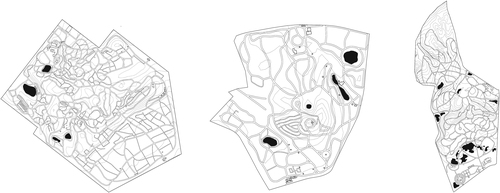

A significant shift in Muslim identity occurred during the first migration exclusionary period from 1924 to 1952, consequential on the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1924 that excluded nonEuropeans from settling in the US.Footnote41 This post-World War I initiative, compounded by the economic constraints of the Great Depression, further detached already-settled immigrants from their homelands. Now under focused acculturation, Muslims adopted more porous identities and began viewing themselves as Americans. They began to establish spaces of worship—the first of which were established between the early 1920s to late 1930s in Michigan, Illinois, and North Dakota.Footnote42 This introduced the first distinct Muslim burial typology: pocket cemeteries (). These “pockets” are small, partitioned areas of existing cemeteries designated for Muslim residents. The plots face Mecca and adorn minimal gravestones, contrasting with both the directional grain and the material extravagance of the larger cemetery.

These cemeteries, managed by superintendents, posed challenges for Muslims whose practices and identity had to be mediated within the white-Christian-capitalist model. This was the best, or at least the most accessible, burial option at the time.

Patch Cemeteries

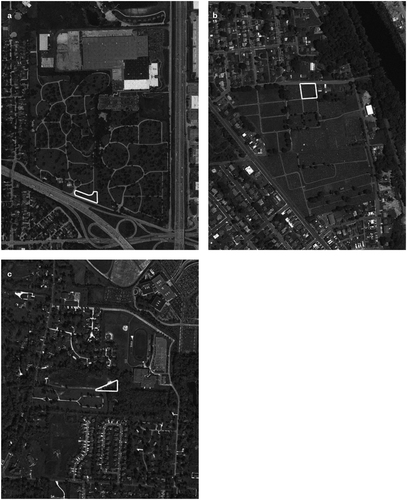

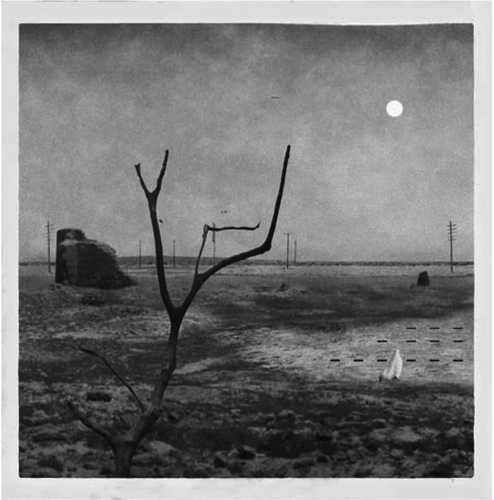

By the second migration wave of 1952–1965, Muslim migrants had established distinct enclaves and dedicated pocket cemeteries. The new national-origins quota system for immigration contained significantly more Muslims.Footnote43 This was largely motivated by the post-World War II competition between the US and the Soviet Union to gain global influence. This further diversified the burial landscape, with more qualified differentiation between subdenominations like Shi’a and Sunni Muslims. With first-wave migrants passing away and enclaves quickly filling their local cemeteries, Muslims began seeking out other cemeteries that would accommodate them. In the midst of expanding suburbia, the more straightforward options were within neighboring cities or states.Footnote44 This is hypothetically easier if these places already have local Muslim enclaves and delineated sections of cemeteries; however, this is not always the case.Footnote45 Based on this assumption, we can begin to understand the second typology: patch cemeteries (). A product of sprawl and the rapid increase of emergent mosques from the second migration wave onward, patch cemeteries are located on isolated rural grounds far from diaspora settlements and mark the first tier of exclusively Muslim cemeteries.Footnote46 Officially, Assyrian Moslem Cemetery in the prairies of Ross, North Dakota, with graves dating back to the 1890s, was the first of this kind.Footnote47 Still, it was anomalous, not yet a distinct burial pattern since major settlements were in industrial capitals. While patch cemeteries allow Muslims to have their own burial space without worrying as much about essentializing their practice to fit into pocket cemeteries, it makes it difficult to access and visit—some even inscrutable via GPS.Footnote48 They are also heavily underdesigned and without on-site facilities, mainly composed of nondescript patches of dirt and small sheds, making moving the body back and forth between different stages of the timed burial procession—ritualistic bathing, shrouding, service, and burial—arduous. These cemeteries are community-led nonprofits that rarely have funds—outside of providing affordable and sometimes free burial services—to invest in landscaping, basic infrastructure, and equipment.Footnote49

The third migration wave occurred from 1965 to 2017,Footnote50 with policies becoming even more open. Reunification rules allowed immigrants already living in the Belt to bring their families and cement settlements, raising the Muslim population to more than one million by 1971.Footnote51 However, in the aftermath of the Cold War, the U.S. and its allies targeted “failed states” to act as new “enemies”—primarily focused on those with predominantly Muslim populations. This ethnification, compounded by the continued anti-Muslim rhetoric of the US government since,Footnote52 forged tensions that Muslims were and are still forced to contend with. It was at the same time that the Rust Belt experienced industrial decline. In the years that followed, the shrinkage of the region’s metropolises was misattributed to its minority populations, many of whom were neglected immigrants from Islamic countries who helped build its inceptive legacy—or refugees housed in the derelict cities post-facto. At the end of the first Gulf War, the Office of Refugee Resettlement found it opportune to scatter the resultant refugees within small decaying Belt cities with low visibility.Footnote53 This prevented access to social services, mosques, and ethnic cemeteries established by prior waves. This inculpating narrative was enacted alongside the evolution of the white-Christian-capitalist cemetery typology that would further bifurcate religious minorities, people of color, and low-income communities from the mainstream.Footnote54

This would produce more patch cemeteries. Now, even with Muslims gravitating towards cities or suburbs with more established diaspora settlements, there is a continued dependence on this typology to accommodate the substantial overflow within the burial spaces established by the first and second waves in the absence of alternatives. This regional fracture would also fragment the burial locations of members within a single family.Footnote55 Some patch cemeteries are so divorced from current Muslim enclaves that they have no demand at all. A 2016 story in the New York Times revealed that even though burial plots were available at the historic Assyrian Moslem Cemetery, they may never be filled. This is because the local Muslim community has either moved, passed away, or converted to Christianity.Footnote56

Proximate Cemeteries

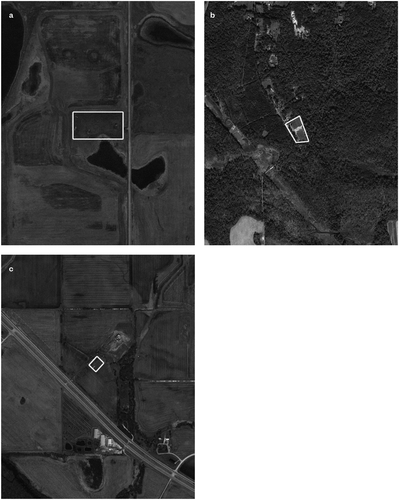

The second migration exclusionary period officially began in 2017 with a series of Executive Orders and Presidential Proclamations, colloquially referred to as the “Muslim Ban,” issued by the Trump administration.Footnote57 Migration or travel from select Muslim countries was prohibited or intensely reviewed. Before this, Rust Belt cities had been encouraging Muslim refugee settlements. In spite of being blamed for the industrial decline, studies showed that they had begun to reverse the population loss and bolster the economy in cities like Springfield, Massachusetts, and Syracuse, New York.Footnote58 The Bosnian refugees alone are responsible for preventing a six percent population dropFootnote59 in Utica, New York since they resettled in the US in 1997. Racialized decline suddenly became racialized potential. This newfound tension between this exclusionary period and the thriving diaspora brings forward the third typology: proximate cemeteries (). With Muslims in the US now working towards stronger, more assertive spatial representation to affirm their integration, contributions, and value, proximate cemeteries need to be located near urban and suburban areas. These cemeteries theoretically solve the accessibility issues particular to the preceding patch cemeteries, as well as establishing physical signifiers of settlement that have sometimes been possible with pocket cemeteries. However, they are the most difficult to get approved, as has been illustrated by the New America reports, and punctuated by the hostility brought by the exclusionary period. Neighbors strongly, and openly, oppose proximate proposals for the same reason that Muslims pursue them: they are proof that the Islamic faith is a part of the US.

Figure 5. a-c. Satellite aerial views of select pocket cemeteries in the Belt. Pockets are easily identified based on the seemingly irregular direction of the plots which point towards Mecca. The rest of the cemetery follows the urban grain or internal circulation paths. Pockets are sometimes located on undesirable edges, such as next to highways. Images courtesy Samiha Meem.

The residual effects of the ban—later reversed by the Biden administration—on the burial landscape will undoubtedly inflate because there is an invariant pattern of how an exclusionary period that follows successful migration waves places pressure on existing burial spaces. Muslims become compressed and limited in movement, necessitating immediate construction to accommodate newly settled populations. Without accessible denominational options, they have been discarded as nameless bodies or placed in compromising positions of forced assimilation. The urgency of the impact of the recent exclusionary period is all the more critical in the wake of COVID-19 and its ever-rising body count. The New York Times recently wrote about a Bangladeshi Muslim immigrant who was forced to be buried farther in New Jersey rather than his home in New York because the local Muslim cemeteries were too overwhelmed to conduct service within the prescribed twenty-four hours.Footnote60 Due to health-based border regulations, repatriation—a practice of recent immigrants—is difficult. More broadly, a 2022 CAIR report revealed that more than “$105 million was funneled into 26 anti-Muslim groups between 2017 and 2019 [from mainstream charitable institutions and foundations] to spread misinformation and conspiracy theories about Muslims and Islam.”Footnote61 This may escalate prejudicial sentiments in decisions regarding Muslim cemetery spaces.

Quotidian Impressions

The forgetting of early Muslims—and the subsequent modern representation of Islam as a recent addition to the country’s religious economy—bears direct consequences for the way conversations about belonging and ownership of land unfold. Muslims were imported into the US through brute force and violence, but in spite of the fact that they have been dying on its soil for half a millennium and prior to the nation’s founding, they continue to struggle to claim their rights to be buried on their own terms. The Rust Belt’s conflict of race is entrenched in this vast field of racialization that otherizes Muslim bodies in life as well as in death. Whether they are pauper, pocket, patch, or proximate, Muslim cemeteries are undesigned—muddy, stark, and severed—lacking the same attention given to major Belt cemeteries, thus cultivating inequality in its typological posture and being a physical expression of living banished in the footnotes of history. The principal issues raised by Muslim residents in the New America cases can be encapsulated as inaccessibility—whether it’s physical, procedural, or theological—posing cultural, social, and symbolic consequences.

The Cultural

Since Islam asks Muslims to bury their dead within twenty-four hours—and unembalmed—physical inaccessibility brings sobering complications. When Muslim burial spaces are full or proposals for Islamic cemeteries are rejected, as was the case in Dudley, citizens have to perform funerary rites locally and then travel for burial far from home, often in different states, which later prevents them from easily visiting the graves for years to come.Footnote62 Even if there are available plots in local pocket cemeteries, they can pose theological inaccessibility issues, such as when management can’t accommodate the urgency of the time constraints or understand the spatial separations required between different Islamic denominations to not homogenize all Muslims into one space.Footnote63 Superintendents who serve white-Christian-capitalist visions of the American cemetery only intensify these obstacles. This instigates a decisive position where Muslims are compelled to compromise their culture.

For example, “green burial” is regarded as one of the most successful US social and environmental movements in the twenty-first century.Footnote64 Elements like embalming, heavy coffins, or large gravestones are classified as excessive pollutants. Instead, green burial offers alternatives, which include, but are not limited to, unembalmed bodies that are wrapped in natural biodegradable fabrics and buried without coffins. These alternatives are routinely cited as reasons for not catering to Muslim clients or denying proposals for Muslim cemeteries. As reported by WBUR, despite hydrogeologists advocating against claims of “ground contamination” in defense of Muslim burial practices, Islamic leaders will often allow local Muslims to defy scripture and bury their dead within coffins or concrete vaults to appease the crowds—recalling the way first-wave Muslims were driven to cremate bodies. This compromise brings little conciliation: “Why not go bury your dead at a Christian cemetery… if you’re willing to violate ‘jihadi law’?” asked a Dudley resident.Footnote65 Despite green burial being proportionally more accepted, the veil of Islam discredits the same methodologies. Muslims can choose to hide behind the green burial movement to mediate the religious prejudice and accelerate locating space (and they have)Footnote66 but, as the spokesperson for the Kentucky proposal addressed, they’d lose representation of their identity in the process.Footnote67 If the diaspora reterritorializes into preexisting white-Christian-capitalist or green burial landscapes, it comes at the cost of their identity—forgoing harmonious integration for imposition. By actively differentiating Muslims from the mainstream, they are treated as a “special species” rather than individual citizens entitled to conscientious mourning and carving community touchstones of heritage that commemorate and enable their cultural belonging.

The Social

Although cemeteries were not initially integrated into city plans, the process of urbanization absorbed them into the US metropolitan fabric.Footnote68 In the industrial period, these “gardens” created a contrast to areas devoted to production—one served an aesthetic function and the other utility.Footnote69 Cemetery associations are organizing and renewing this ontological multiplicity. For example, Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati, Ohio—founded in 1845 and designated landmark status in 2007—currently has an extensive event schedule that includes plant and wildlife lectures, tours, national holiday events, family nights, and concerts. However, in the process of cemeteries becoming part of cities, Muslim cemeteries were being built even farther away. As discovered in the New America reports, patch cemeteries are the most consistently approved over those within more urban areas, even when the land is available and zoned for a cemetery. A geographical scan of the Rust Belt region substantiates this. The majority of Muslim cemeteries I found through mapping tools were patch or pocket, and rarely proximate. This extant burial pattern conserves Gaudin’s early vision of the white-Christian-capitalist American cemetery. This pushback of proximate cemeteries, along with pocket cemeteries reaching capacity, directs dependence on patch cemeteries.

In “The Garden and the Scene of Power,” Laura Verdi remarks that industrial, or postindustrial, areas are increasingly transformed into gardens because of the novel complexity of social power it brings to the city and its people.Footnote70 With more and more builds in the patch variation, Muslims are prevented from accessing this social power in their daily lives. Ironically, Muslim cemeteries in the East had adopted the ideology of the “garden” within their death spaces long before it was established in the West.Footnote71 Islam even encourages regularly visiting places of the dead rather than reserving them solely for personal grieving. A contemporary example of this is the Azimpur Graveyard—a landmark in the capital of Muslim-majority Bangladesh—where families grow plants and flowers on top of shrouded bodies. Landscaping and routine maintenance aren’t always feasible for patch cemeteries due to their considerable distance from enclaves and lack of basic infrastructure like water or bathrooms. By disconnecting an entire community from accessing this emergent social space, there is a clear fragmentation of Muslim identity in the city—and within themselves—as well as the bereavement of experiencing the same level of agency in death as others.

The Symbolic

In pocket cemeteries, Islamic representation finds itself desaturated or unable to assert itself at all. The extravagant coffins and headstones—an indulgence Islam is against—dominate the 200-year-old model. As scholars like Arehart have shown, this is a deterrent for controlling cultural makeup.Footnote72 The president of Islamic Funeral Services in Brooklyn, New York remarks on how the simplicity of Muslim funerary practices is “at odds with how the funeral business works in the US, where traditional funerals can cost from $6,000 to well over $50,000.”Footnote73 Symbolism is not just an affirmation of cultural representation, but acceptance. After Muslims in Flint established the “Garden of Peace,” families would no longer have to drive hours to bury their loved ones in pocket cemeteries, removing the metronomic reminder of their othering in their hometowns.Footnote74 When Aman Ali, an Indian Muslim who grew up in Ohio, was interviewed by the New York Times about his quasi-pilgrimage to the historic Assyrian Moslem Cemetery, he said: “Learning that Muslim communities have been in this country since the 1800s, made me realize I am the latest chapter in a book that’s being written about our beautiful community […] It was the first time I felt like I actually belonged here.”Footnote75 When symbolic expressions of acceptance and unity are in absentia, the felt separation between Muslim and non-Muslim communities instigates further complications in mending fraught relationships founded on hundreds of years of social and political tension. This is until, as in the case of Ross, North Dakota, they pack their bags and move elsewhere.

Yet, arguably, symbolic meaning cannot operate on its own. The American Moslem Society (AMS), established in 1938 in Dearborn, Michigan, serves one of the largest Muslim settlements—dating back to the first wave brought by Ford factories.Footnote76 In 1992, after purchasing land in Detroit’s Woodmere Cemetery, the AMS enacted a burial program that offered plots at cost or cheaper directly to Muslims. This enticed families across the Belt and filled thousands of plots, calling for the AMS to purchase 1000 additional plots with installment payments.Footnote77 However, the Detroit Free Press reported in 2020 that after they had already paid for 622 plots, Woodmere refused to give them access to any without having paid for all. According to the article, Woodmere was also not meeting its contractual obligation for grounds care. The surrounding rolling hills, rich flora, and polished circulation starkly contrast the patchy surfaces of Muslim pockets.Footnote78

These cases—from the six-year legal battle in Stafford County to the ultimately abandoned project in Dudley—are, in fact, an aggregation of a half-millennium of turmoil: they won’t go away so easily. When Muslim slaves were stripped of their religion, it was because the free will to explore their own faith acknowledged their humanity and eroded the moral authority of white Christian slaveowners.Footnote79 Now, the afterlives of that legacy persist in its modern performances of legal snags, design deficiencies, and the histrionic public forum circuit. In its continuance, Muslims face an “assimilation or bust” crisis. While under completely different circumstances, both pursue the same symbolic end: obscuring identity. It is for this reason that the Department of Justice’s involvement in these cases, although essential to hold discrimination and deprivation accountable, should become unnecessary. In the Netherlands, a Burial Act was revised in the 1980s that removed all unnecessary obstacles for Muslims, specifically addressing and understanding the components of Muslim burial. This allowed the number of Islamic burial plots to increase, bringing a significant change in the long-term and widespread material conditions of their Muslim diaspora that couldn’t be reduced to pure symbolism that otherwise absolves collective responsibility.Footnote80 They were coded in with specificity. The US currently lacks the definite easements required to incite structural change toward prevention to replace its current case-by-case system of damage control that otherwise obscures and aids a pattern of misbehavior at the county level.

Next of Kin

At a cursory glance, the New America reports, and similar articles that have cropped up since, seem like singular instances of violence in a post-Trump United States. When they are all viewed simultaneously—making connections between satellite maps, legal transcriptions, and migration history—they add up to unearth a more protracted and fraught relationship between the state, its spaces, and its subjects (). This Muslim fight against the erasure of belonging in burial—inheritance and representation of land—isn’t unique to the US, nor are Muslims its exclusive victims. The former is seen in the recent demolition of the historical Al-Yusufiya cemetery in occupied Jerusalem, despite protests by Palestinians, by Israeli authorities in its continued project of “Judaization”Footnote81; or the widespread disappearing of Uyghur graveyards in China’s coordinated scheme to erase Islam within its borders.Footnote82 The latter is seen in the lost burying grounds of Black slaves and freedpeople in the US that were carelessly excavated, built over, and only rediscovered centuries later on construction sitesFootnote83; the hundreds of John and Jane Doe dead in desert borderlands during their journey into the US from Mexico now buried nameless or ashes spread in the oceanFootnote84; and the Indigenous peoples who had to “prove that, when alive, the blood in [their] veins came 75 percent from Caucasian forebears” to meet American cemetery policies.Footnote85

Figure 6. a-c. Satellite aerial views of select patch cemeteries in the Belt. These cemeteries are far removed from urban areas and isolated in rural locales, from farmland plots to wooded areas. They likely require investment in basic infrastructure and resources like water. Images courtesy Samiha Meem.

Figure 7. a-c. Satellite aerial views of the three definite proximate cemeteries (as of 2020) discovered in the Belt. The criteria were for there to be prominent visibility of adjacent communities and confirmation of not being part of a larger non-Islamic cemetery. Images courtesy Samiha Meem.

Figure 8a. Representation of key elements within pocket cemeteries, including unkept grounds in enclosed Muslim pockets, refined landscaping and paths in the larger cemetery, and Christian insignia that overpowers the shared space. Image courtesy Samiha Meem.

Figure 8b. Representation of key elements within patch cemeteries, including backroads, minimal structures, and indistinct landscaping for grave zones. Image courtesy Samiha Meem.

Figure 8c. Representation of the proposed sites for proximate cemeteries in postindustrial Belt towns that are subject to rejection but could potentially become impactful public open spaces—like an Islamic cemetery—that increase neighboring real estate values and quality of life, as other major Belt cemeteries have. Instead, the veil of Islam interprets proposals as a source of property devaluation and social hostility. Image courtesy Samiha Meem.

In “Grave Matters: Segregation and Racism in U.S. Cemeteries,” David Sherman calls these systems of calculating whiteness in exclusion-coded US cemeteries an “esoteric mathematics,” interpreting it as the “desire to make one’s feeling of whiteness, as an intangible value or possession, into an existential fact” and this being a “desperate and incoherent claim for an exclusive social prestige that can be passed down through generational lineage” in the belief that “one’s whiteness preceded birth and will continue after dying.”Footnote86 Sherman’s statement offers some insight into the likely driving factor of this Muslim othering in death. If religious freedom is coded into the US ethos by law, then one can presume that refuting the social worth of an Islamic cemetery is not simply about denying religious expression in the present but, instead, preserving the unfaltering legacy of the white-Christian-capitalist American cemetery for generations to come. This defense mechanism originates from a haunting anxiety of a future that is entirely imagined. In “Fear of a Muslim Planet,” Grayson Clary coins the term “Islamophobic futurism” to categorize a microgenre in fiction writing in which authors reimagine the West as being taken over by Islam in near futures. In these books, writers employ vitriol against Islam—lumping hatred and fear of the religion, and its constituents, together indifferently—as directive material.Footnote87 This literary apparatus finds itself gratified in the public imagination as well. In a 2019 report for Brookings Institute on the views of Islam held by Trump supporters, George Hawley found that most “simultaneously wish to uphold the principle of religious freedom and are concerned that a large Muslim population will undermine American unity.”Footnote88 This illusion is shattered in the face of a 2018 Pew Research Center study that projected the US Muslim population to double from 3.45 million to 8.1 million by 2050 and become the nation’s second-largest religious group—marginal compared to the projected 261.96 million Christians.Footnote89

This “mortuary panic”Footnote90 is a future-forward mission: to deliver spatial agency in death is to sharpen the notional existence—the power, identity, and material evidence—of undesirable Muslim figures in a prospective United States. The conservation of Islamophobic futurist visions serves as an ongoing commitment to enacting tenets of privileged belonging and dispossession amidst the urgencies of the contemporary field of death. In order to repair this disquiet and excise the ever-lingering inheritance of finite, or forgotten, burial representation of the growing Muslim diaspora, these fictions must be countered with facts—excavating and exposing further unknown dimensions of their interments—but, also, with calls for a total reconstruction of the insidious existing cemetery model with explicit claiming of Muslims, and a change in the way we perceive a tomorrow in the United States with Islam. As expressed by Amjad Bhatti, a first-generation Pakistani immigrant in Massachusetts: “[My family] belong to this land now.… This is our country [too].”Footnote91

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Samiha Meem

Samiha Meem is a Bengali-Canadian designer and writer. She holds an MArch from McGill University and a BArch from the University of Waterloo. Her work explores modes of representation, production, and labor and how that meets, shapes, and/or is shaped by new media and its social topographies. Her writing has been published in Flash Art’s Dune Journal, E-Flux Architecture, and at the Art Metropole. Her visual work and collaborations have been featured in New York Magazine, Interview Magazine, and The Architect’s Newspaper. She is currently teaching at The Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture at McGill University.

Notes

1 “Activities” are defined as incidents of targeted hate, including, but not limited to, hate crimes. See “Muslim Diaspora Initiative: Anti-Muslim Activities in the United States,” New America, 2018, https://www.newamerica.org/in-depth/anti-muslim-activity/.

2 Alex Wimsatt, “Bullitt County Board of Adjustments Denies Permit for Islamic Cemetery,” SpencerMagnet, February 2013.

3 Wimsatt, “Bullitt County Board of Adjustments.”

4 Wimsatt, “Bullitt County Board of Adjustments.”

5 Associated Press, “Chisago County Board Reverses Self, Approves Muslim Cemetery,” Washington Times, March 16, 2017, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/mar/16/chisago-county-board-reverses-self-approves-muslim/.

6 David Boeri, “Proposal for Muslim Cemetery in Dudley Meets Opposition from Residents,” WBUR, February 5, 2016, https://www.wbur.org/all-things-considered/2016/02/05/muslim-cemetery-proposal.

7 Jess Bidgood, “Muslims Seek New Burial Ground, and a Small Town Balks,” New York Times, August 29, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/29/us/muslims-seek-new-burial-ground-and-a-small-town-balks.html.

8 Boeri, “Proposal For Muslim Cemetery.”

9 All Muslim Association of America Inc. v. Stafford County, Virginia and Virginia and Stafford County Board of Supervisors, Civil Action No. 1:20-CV-00638 (2020), https://www.milbank.com/images/content/1/5/v2/159727/96-AMAA-Second-Amended-Complaint.pdf.

10 John Reid, “Lawsuit over Proposed Cemetery in Stafford Filed by AMAA,” PWPerspective, February 2021, https://pwperspective.com/news/lawsuit-over-proposed-cemetery-in-stafford-filed-by-amaa/.

11 All Muslim Association of America Inc. v. Stafford County.

12 Jordan Williams, “Virginia County Repeals Ordinances Preventing Muslim Cemetery,” The Hill, October 14, 2021, https://thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/576783-virginia-county-repeals-ordinances-preventing-muslim-cemetery-after-doj/.

13 All Muslim Association of America Inc. v. Stafford County.

14 Huzaifa Shahbaz, “Islamophobia in the Mainstream,” Islamophobia.org, July 26, 2022, https://islamophobia.org/reports/islamophobia-in-the-mainstream/.

15 “Nationwide Anti-Mosque Activity,” ACLU, January 2022, https://www.aclu.org/issues/national-security/discriminatory-profiling/nationwide-anti-mosque-activity.

16 “Religious Landscape Study,” Pew Research Center, 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscape-study/religious-tradition/muslim/.

17 The Belt also experiences high anti-mosque activity. See ACLU, “Nationwide Anti-Mosque Activity.”

18 Joshua Stevens, “Graveyards of The Contiguous USA,” Joshuastevens.net, October 28, 2018, https://www.joshuastevens.net/blog/graveyards-of-the-contiguous-usa/.

19 Sam Haselby, “Muslims of Early America,” Aeon, May 20, 2019, https://aeon.co/essays/muslims-lived-in-america-before-protestantism-even-existed.

20 Dora Mekouar, “America’s First Muslims Were Slaves,” VOA News, January 29, 2019, https://www.voanews.com/a/america-s-first-muslims-were-slaves/4763323.html.

21 Peter Manseau, “The Muslims of Early America,” New York Times, February 9, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/09/opinion/the-founding-muslims.html.

22 Muna Mire, “Towards a Black Muslim Ontology of Resistance,” The New Inquiry, April 29, 2015, https://thenewinquiry.com/towards-a-black-muslim-ontology-of-resistance/.

23 Samory Rashid, “Divergent Perspectives,” in Black Muslims in the US: History, Politics, and the Struggle of a Community (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 67–91.

24 Khaled A. Beydoun, “America Banned Muslims Long Before Donald Trump,” Washington Post, August 18, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trumps-anti-muslim-stance-echoes-a-us-law-from-the-1700s/2016/08/18/6da7b486-6585-11e6-8b27-bb8ba39497a2_story.html.

25 Rosina Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations: Arab American Burial Practices,” in Till Death Do Us Part: American Ethnic Cemeteries as Borders Uncrossed, eds. Allan Amanik and Kami Fletcher (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2020), 247–69.

26 Jane Smith, “Islam in America,” in The Columbia Guide to Religion in American History, eds. Paul Harvey, Edward J. Blum, and Randall Stephens (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 367.

27 Umar F. Abd-Allah, “The Yankee Mohammedan,” in A Muslim in Victorian America: The Life of Alexander Russell Webb (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 3–20.

28 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

29 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

30 Sally Howell, “Groundwork,” in The Cambridge Companion to American Islam, eds. Juliane Hammer and Omid Safi (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 47.

31 Craig Young and Duncan Light, “Interrogating Spaces of and for the Dead as ‘Alternative Space,’” International Review of Social Research 6:2 (January 2016): 61–72.

32 Jill Sinclair, “‘These Beautiful Pleasure-Grounds of Death’: Nineteenth-Century America’s Adaptation of the Parisian Rural Cemetery,” Foreign Trends in American Gardens: A History of Exchange, Adaptation, and Reception, ed. Raffaella Fabiani Giannetto (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016), 59–87.

33 Sinclair, “‘These Beautiful Pleasure-Grounds.’”

34 Sinclair, “‘These Beautiful Pleasure-Grounds.’”

35 Aaron Sachs, Arcadian America: The Death and Life of an Environmental Tradition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014).

36 Kelly B. Arehart, “‘For Interment of White People Only’: Cemetery Superintendents’ Authority and Wealthy White Protestant Lawn-Park Cemetery, 1886–1920,” in Till Death Do Us Part: American Ethnic Cemeteries as Borders Uncrossed, eds. Allan Amanik and Kami Fletcher (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2020), 183–208.

37 Arehart, “‘For Interment of White People Only.’”

38 Sinclair, “‘These Beautiful Pleasure-Grounds of Death.’”

39 Arehart, “‘For Interment of White People Only.’”

40 Sinclair, “‘These Beautiful Pleasure-Grounds of Death.’”

41 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

42 Harvard’s Pluralism Project identified that Muslims would previously gather in private homes or small rented spaces.

43 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

44 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

45 Muslim populations are not evenly distributed across the country, potentially exacerbating the sparseness of Islamic cemeteries. See Besheer Mohamed, “New Estimates Show U.S. Muslim Population Continues to Grow,” Pew Research Center, January, 23, 2018, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/03/new-estimates-show-u-s-muslim-population-continues-to-grow/.

46 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

47 Samuel G. Freedman, “North Dakota Mosque a Symbol of Muslims’ Long Ties in America,” New York Times, May 27, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/28/us/north-dakota-mosque-a-symbol-of-muslims-deep-ties-in-america.html.

48 Freedman, “North Dakota Mosque.”

49 The crowdfund webpage for Virginia’s AMAA Cemetery mentioned not having on-site water supply, toolshed, or washrooms.

50 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

51 Beydoun, “America Banned Muslims.”

52 New America, “Muslim Diaspora Initiative.”

53 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

54 Jason Hackworth, “Racial Threat and Urban Decline,” in Manufacturing Decline: How Racism and the Conservative Movement Crush the American Rust Belt (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 35–62.

55 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

56 Freedman, “North Dakota Mosque.”

57 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

58 Tanvi Misra, “The Cities Refugees Saved,” Bloomberg, January 31, 2019, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2019/01/refugee-admissions-resettlement-trump-immigration/580318/.

59 Misra, “The Cities Refugees Saved.”

60 Liam Stack, “The Pandemic Upends Islam’s Holiest Month,” New York Times, May 26, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/26/nyregion/coronavirus-ramadan-muslim.html.

61 Shahbaz, “Islamophobia in the Mainstream.”

62 Bidgood, “Muslims Seek New Burial Ground.”

63 Khadija Kadrouch Outmany, “Religion at the Cemetery: Islamic Burials in the Netherlands and Belgium,” Contemporary Islam 10:1 (2015): 87–105.

64 Marisa Gonzales, The Green Burial Movement (Saarbrücken: LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, 2014).

65 Boeri, “Proposal For Muslim Cemetery.”

66 Boeri, “Proposal For Muslim Cemetery.”

67 Wimsatt, “Bullitt County Board of Adjustments.”

68 Peter Johnson, “The Modern Cemetery: A Design for Life,” Social & Cultural Geography 9:7 (2008): 777–90.

69 Laura Verdi, “The Garden and the Scene of Power,” Space and Culture 7:4 (2004): 360–85.

70 Verdi, “The Garden and the Scene of Power.”

71 Oleg Grabar, Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984).

72 Arehart, “For Interment of White People Only.”

73 Mir Ubaid, “What Is a Muslim Funeral Like in New York?,” Al Jazeera, March 7, 2016, https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2016/3/7/what-is-a-muslim-funeral-like-in-new-york.

74 Sami Yenigun, “A Muslim Cemetery Helps To Ease Funerals’ Strain,” NPR, July 20, 2012, https://www.npr.org/2012/07/23/155137429/a-muslim-cemetery-helps-to-ease-funerals-strain.

75 Freedman, “North Dakota Mosque.”

76 Hassoun, “Family, Religion and Relocations.”

77 Afaf Humayun, “The Cost of Death Can Get in the Way of Grief,” Arab American News, October 13, 2017, https://www.arabamericannews.com/2017/10/13/the-cost-of-death-can-get-in-the-way-of-grief/.

78 Frank Witsil, “Dearborn Mosque: Woodmere Cemetery Shutting out Muslims from Graves They Already Purchased,” Detroit Free Press, July 3, 2020, https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/wayne/2020/07/03/dearborn-mosque-woodmere-cemetery-muslims/5370476002/.

79 Manseau, “The Muslims of Early America.”

80 Outmany, “Religion at the Cemetery.”

81 Myra Mansoor, “Israeli Militants Destroying Palestinian Graves To Make Room For National Park,” The Organization for World Peace, November 3, 2021, https://theowp.org/israeli-militants-destroying-palestinian-graves-to-make-room-for-national-park/.

82 Matt Rivers, “More than 100 Uyghur Graveyards Demolished by Chinese Authorities,” CNN, January 2, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/01/02/asia/xinjiang-uyghur-graveyards-china-intl-hnk/index.html.

83 Jill Lepore, “When Black History Is Unearthed, Who Gets to Speak for the Dead?,” New Yorker, September 27, 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/10/04/when-black-history-is-unearthed-who-gets-to-speak-for-the-dead.

84 David Sherman, “Grave Matters: Segregation and Racism in U.S. Cemeteries,” The Order of the Good Death, April 20, 2020, https://www.orderofthegooddeath.com/article/grave-matters-segregation-and-racism-in-u-s-cemeteries/.

85 Sherman, “Grave Matters.”

86 Sherman, “Grave Matters.”

87 Grayson Clary, “Fear of a Muslim Planet,” The New Inquiry, March 10, 2015, https://thenewinquiry.com/fear-of-a-muslim-planet/.

88 George Hawley, “Ambivalent Nativism: Trump Supporters’ Attitudes Toward Islam and Muslim Immigration,” Brookings, July 24, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/research/ambivalent-nativism-trump-supporters-attitudes-toward-islam-and-muslim-immigration/.

89 Mohamed, “New Estimates Show U.S. Muslim Population.”

90 Sherman, “Grave Matters.”

91 Denise Lavoie, “Backlash Greets Plans for Muslim Cemeteries Across US,” APNews, April 25, 2016, https://apnews.com/article/58d4287818d94658ac52db51ddd94f36.