Abstract

Sean Connelly is a Pacific Islander American artist in Honolulu, O‘ahu where he/they were born and still live and work. Connelly creates work that focuses on material, place, and time. They work primarily in sculpture, architecture, and installation, but are also active in experimental cartography, filmmaking, design theory, architectural history, urban sociology, land planning, data analysis, and visual arts like new media, bioculture, and land art. Through this work Connelly creates clarity around the physical and spiritual conditions of the built environment. They engage the built environment and its effects on their community to decolonize and address the traumas of settler colonialism, militarization, and modernism embedded physically in the environment in architecture and in everyday life. Professionally, Connelly operates under the imprint AFTEROCEANIC and directs a range of client-based and parainstitutional grassroots projects as a Pacific laboratory for applied theory and culture in design and built environments.

Figure 1. Sean Connelly, Thatch Assembly With Rocks (2017) integrates traditional loulu palm thatching as a viable example of modern architecture.

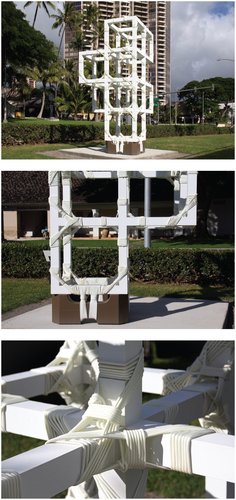

Figure 2. Sean Connelly, Sixteen Cube Truss (2020) adapts Hawaiian canoe lashing for use in common building structures, such as the truss.

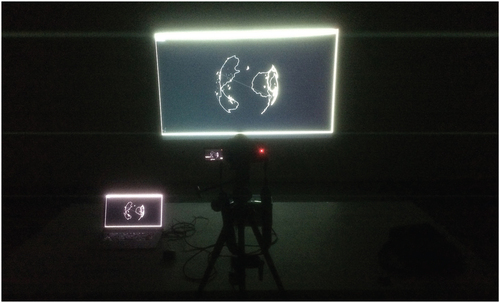

Figure 3. Sean Connelly, Hawai‘i Pangea Antipode in Africa-Pacific (2014) is one of a series of experimental cartographies exploring concepts of the oceanic in scale and time.

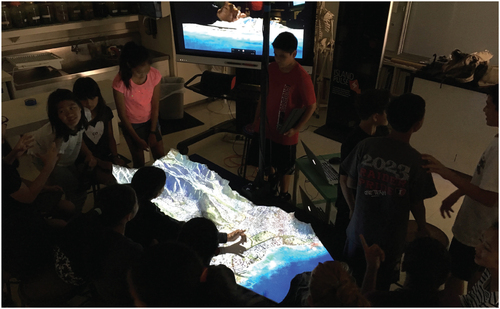

Figure 4. Sean Connelly, Holodeck Ahupua‘a (2017) was a mobile installation of the project Ala Wai Centennial, and doubled as a geospatial workshop for public school students in Honolulu.

Figure 5. Sean Connelly, Justice Advancing Architecture Tour (2021) is a documentary film in progress revealing an alternative architectural history for Hawai‘i.

Figure 6. Sean Connelly, Three Houses (2017) are architectural mockups paired with Thatch Assembly With Rocks and Sixteen Cube Truss.

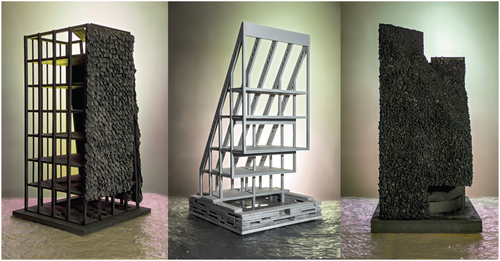

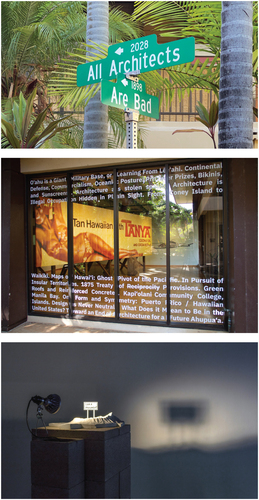

Figure 7. Sean Connelly, Learning From Lē‘ahi (2021) is a sculptural exhibition about architecture and urbanism relating to the history of the United States and its militarization of ‘āina (land, that which feeds).

Cruz Garcia: To be honest with you, the more interviews we do, the more we question the idea of reparations, because the conclusion seems to be that we need something else. We don’t need to fix this system, but rather replace it with something else. To start, it would be good to focus on some of your pedagogical and artistic projects in the framework of reparations. How does the historical-cultural-political framework of Hawai‘i in its condition to the United States provide a framework to your work as a teacher and in your artistic practice? How do you engage with Hawaiʻi’s history in the context of reparations when the system may be broken and not working?

Sean Connelly: I first became familiar with the concept of reparations because of the mentorship of my community. One thing that’s special about our community is that we have so many people from Hawaiʻi that have moved away and have done important work, and then have moved back home. One of them is Mari Matsuda. She was the first tenured female Asian-American law professor in the United States in 1998 and one of the leading voices in critical race theory since its inception. Mari Matsuda and her husband Chuck Lawrence are part of a whole network of people who contributed to the concept of critical race theory.

Another way I became familiar with reparations came from a job I had cleaning a neighbor’s house when I was younger. I had a side job as a house cleaner for my elderly neighbor who is Japanese. She told me about how Japanese Americans actually got reparations for being in internment camps in World War II. I believe the reparation was something around $20,000 for survivors. She would tell me stories about being in the internment camp in Chicago where she met her husband from Hawai‘i who was interned there. But today, not many people know or remember that Japanese survivors of internment camps received reparations.

When I hear the term reparations in today’s context, I always think about that history and background, and Mari Matsuda, whom I first met in 2012. She really influenced my thinking about race and reparations. In terms of the cultural context of the United States and its relationship to my work, I started off in architecture but eventually pushed myself to expand the discipline, in many ways. I felt there was a limit to what design could actually accomplish in regards to what really needed to happen. For example, in terms of the evolution of concepts from ten or fifteen years ago, I would say that conversations about the built environment, global warming, energy efficiency, and sustainability have evolved into terminology like climate change, sea level rise, and social justice. Meanwhile, Hawaiians have been talking about decolonization since the 60s and 70s, really even since 1898. There’s always been an underground contingent of radical thinkers and cultural practitioners who kept things going on the DL.

I think people still have a hard time making a connection to continuity concepts and how they evolve. When you’re talking about colonialism, decolonization, demilitarization, or antiracism, you’re also talking about, you know, climate change. It’s connected. Sometimes that connection is much harder to demonstrate in architecture than it is to express in, let’s say, art.

When you’re talking about reparations, you’re essentially talking about legal tools and financial strategies. There’s a whole list of strategies that could fall under the concept of reparations. There’s so many different categories we can think about when it comes to reparations. What are the different ways to frame the cost of healing or justice?

Garcia: Let’s talk about some of the studios you have taught at Columbia and other universities. I know you have an ongoing project about alternative education in Hawai‘i. Also, the way that your practice is framed as a space for the production of knowledges that challenge Hawai‘i’s occupation, and its use for military purposes. What is the role that architectural pedagogy plays in engaging with important questions about landscape, power, occupation, militarization, and the possibilities of other futures?

Connelly: The first thing that comes to mind has to do with this idea that Hawaiʻi is essentially a different country. There’s a completely different history of this place, as well as a culture difference. And this sort of dance between, you know, this idea that Hawaiʻi’s been either ahead of the curve or sort of behind the curve. Maybe you can relate to this being from an island, but there’s a ‘small island’ or insular mentality here that’s the residue of colonialism, where if you’re from Hawaiʻi you’re not good enough unless you’ve received validation from the mainland United States.

Garcia: Right.

Connelly: Growing up we called the United States the mainland but now we call it the continent. And so that insular thinking is part of the psychological abuse of being from a place that was recently a former territory. Hawaiʻi only became a state in 1959, six months before my mom was born in Honolulu. I think it was around 2014 when the Black Lives Matter movement grew nationally, then Standing Rock happened in 2016, and you saw more mainstream awareness of the concept and reality of Indigenous people in the United States. I went to Standing Rock in 2016 and it was grounding because the Native people I met there all knew about similar issues around the built environment happening in Hawaiʻi with Mauna Kea and the proposed construction of a telescope on top of the tallest mountain by the US government, which really divided the community in a way.

And so I guess that’s all to say that for architecture, concepts like decolonization, social justice, or even just acknowledging settler colonialism is still a new concept for many people in our field. A lot of people have just started thinking about these things, maybe since 2020, like two years ago…

Cruz: Yeah, like two years.

Connelly: I’m from a community that’s been thinking about these issues openly since the 70s, and a lot of that has to do with the work of Haunani-Kay Trask, as well as many others thinkers and artists in Hawaiʻi, many of whom are female scholars and artists. It’s also about the relationship that people in Hawaiʻi, as well as other Indigenous people, have to a place that makes it special.

One major thing that I appreciate about being from Hawaiʻi is that I feel our experience is different from the experience of people from the continent because of our heightened sense of relationship we have to place. On the continent, you’re born on a giant landmass and, especially in larger cities, there is an overarching sense of placelessness that you feel in, say, New York City, where there’s so many people settling from different places. In New York for example, you’re in this sort of urban zone where you’re not actually enabled to physically care for that place as land and environment. In this context, it’s really a transactional relationship with the place, where people can only care about what the place can do for them.

I don’t mean that as judgement. But in Hawaiʻi, there is a sense of place that is grounded in responsibility to care for that place in ways that are physically, historically, and genealogically connected. There is also a strong sense of acknowledging the legacy of the work of those who come before us, like remembering Haunani-Kay Trask, and enabling generations to pick up the torch. A lot of people who are really into environmental or cultural work don’t always consider themselves activists either. They’re just sort of like, ‘this is just our way of life.’

With all that said, there’s been a lot of progress in other disciplines like political science, history, and you know, Hawaiian studies. But in terms of architecture and the built environment, there’s a gap in that history. Architecture without the histories of Native Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders is essentially just a subsection of white studies. Mostly everything about architecture to date has been the study of how white people think about the environment. Putting all that architectural knowledge into a bucket of white studies is not meant to center whiteness, but it’s meant to acknowledge that the white canon isn’t the only knowledge. There’s so much more to remember. For instance, what happens when we center Hawaiian history in the context of American architecture and the built environment? American architecture is, to me, a pedagogy of the built environment. And so we don’t even really know what the built environment of the United States is without knowing the history of the United States built environments that emerged after 1898.

When we read Rem Koolhaas, he seems to talk about everything, like tourism, commercialism, real estate, all that kind of stuff. But he doesn’t talk about the military. Denise Scott Brown also talks about tourism and ordinary American life. But she also doesn’t really address the impact of the military. Even looking at a lot of the environmentalists like Rachel Carson, reading her work, I don’t really hear anything about the military’s impact on the environment.

The status quo has been talking about sustainability and climate change while ignoring the military and putting the blame on the average working class person. I drive a truck because I need to haul shit for work and, like, giving up my truck is not gonna make a difference as long as the military consumes the most fuel. It’s the military who built twenty giant fuel tanks underground on O’ahu during World War II, which is filled with fuel that is leaking into our freshwater aquifer that is our only water supply for a million people on one small island.

So there’s all of these deep layers of how unaware we all are about the condition of our built environment today. There are so many people who aren’t aware of these things. But then when people do become aware, it feels too overarching. In my experience, people either become really scared or just shut down because their families were in the military or like we just can’t imagine what demilitarization, or sovereignty, or repatriation, e.g., reparations actually looks like.

In terms of architecture and design, we do have to start confronting that history, and connecting building issues to issues that reach beyond just a concern for the environment.

Garcia: The questions about the military that you bring up are really interesting. You mentioned the telescope [on Mauna Kea], which brings up the issue of the US military being the single largest polluter the world has ever seen, and also being the biggest client of British Petroleum (BP). We wonder about the footprint of the military complex in a place like Hawai‘i.

For us, we can think of the military presence in Puerto Rico which serves as a strategic point on the ocean, because there’s a full infrastructural apparatus that comes with that. And with that footprint also comes precarity and inherent risk to the population and ecologies. As you mentioned, there’s an environmental footprint of toxicity that is dangerous and it harms people’s lives.

Can you talk a bit about that footprint and how it relates and shapes your practice? In your work you have presented polemics against authors that like to look at US popular culture while overlooking social justice struggles. You have worked with Learning from Las Vegas, which curiously enough was produced right after the Civil Rights movement but it makes no mention of it. There’s a very violent history of architectural theory being produced while overlooking the struggles of people that have been disenfranchised for centuries. In what sense is that confrontation of the military versus the official discourse informing what you have been developing?

Connelly: The footprint of the military is as obvious as it is hidden in Hawaiʻi. The entire island of O’ahu for instance was converted into a military base between 1898 and 1928. And in the process the Hawaiian language was repressed. Native Hawaiian farmers and other farmers of color were displaced from their ancestral lands as they were dredged and filled to build military defense systems and infrastructure for urbanization.

When I first started my practice in 2006, I started with a concept called “Decolonizing Architecture.” That evolved into a concept called “Hawaiʻi Futures.” At that time my practice was mainly about rethinking architecture and urbanism through the lens of sustainability, agriculture, housing, and land use informed by Indigenous notions of resource management, governance, and bioculture. There’s a lot I felt architecture can learn from this example of Indigenous knowledge. Before Western influence, Hawaiians were self reliant on the most remote landmass on the planet, for instance.

Over time my interest in land use evolved into an interest in the military footprint in Hawaiʻi because the zoning of land use districts in Hawaiʻi came decades after World War II, after the military already consumed a footprint covering over 25 percent of the island. And so land use in Hawaiʻi is actually structured around the military footprint. For example, agricultural and conservation land use tends to surround military training areas while urban land use surrounds military bases. Thus the military is hidden in plain sight.

Over the past ten years, my thinking has changed in three ways: thinking about the future, material exploration, and general advocacy and learning. One influence in my work is the concept of futurism or the ability to time travel into the future or think about the past with some sense of critical optimism. For instance my sculpture Thatch Assembly With Rocks is a material study that time travels to a moment in architecture history that didn’t happen because of US imperialism, which is the regionalism of incorporating the use of traditional thatching with loulu palm, a tree endemic to Hawaiʻi, as a material for modernism. Thatching is universal and often considered primitive or nonmodern. But it’s quite modern in its minimalism and utility in application.

I feel like the challenge of addressing the impact of the military or more generally settler colonialism in the built environment requires me to think about time with a sort of elastic or nonlinear dimension because we have to understand the past to a certain extent and understand the future. But of course not all architects are good at that. But at least we’re generally optimistic and so there’s a kind of ability to think about the past and future that also creates pathways for understanding the needs and possibilities for reparations, or reconfiguring space to atone for or repair the atrocities of the past.

With that said, the other influence of the condition of the built environment in Hawaiʻi that influences my work as an artist is about material exploration, and then pedagogy, or learning. In one project, I’m actually working with native materials like loulu palm for thatching or adapting traditional Hawaiian canoe lashing to make a conceptual prototype for building structures like a truss. So this project is in response to something like LEED that creates incentives to buy certain products or to use certain energy-saving technologies that are meant to help to drive a new sector or new market forward.

My work, Hawai‘i Futures and Ala Wai Centennial are examples of projects that try to address the issue of how we learn about the built environment and the skeletal structure that shapes it. My most recent exhibition sculptures Learning from Lē‘ahi and All Architects Are Bad, 1898–1928 directly confronts this issue of how we learn about the built environment and what is still missing from that learning specifically in the pedagogy of architecture. These are works that I offered as the basis for the design studios with Dominic Leong, Mario Gooden, and Shohei Shigematsu. When it comes to large-scale issues of infrastructure and development in the built environment, there is always a discussion of how it is financed. The example of Ala Wai Canal and how to upgrade it for climate change is an example.

Garcia: Your work engages the market and capitalism. It engages military occupation. Then there is the pedagogical project, and also the material culture that is confronting either the market or some Indigenous, native epistemologies and practices.

We’re also interested in a part of your practice that brings new vocabulary. It is not really new, because it is a vocabulary that has existed, but it is new to the mainstream architectural discussions. Because you’re using forms of language that are spatial and cultural. They are anchored in a socio-political-environmental context.

There’s a part of your work that deals with metaphors, not in the sense of metaphoric reparations, but in the way that they can provide a powerful and beautiful way to shape forms of political power and resistance.

The use of these words comes with some form of political power when there’s also resistance to let language go under the forces of colonialism. But also, because perhaps those concepts only exist in their vernacular or in their actual original language, they are untranslatable. As we talk about reparations, we can think about how the use of those concepts can carry ideas about futurism, or about projective possibilities of thinking about the world in a different way.

And if we consider that, as you mentioned, architecture as we know it is white studies, what happens when there are other studies that are taking all these concepts that are fundamental for us to understand the world? Do you also see the role of those concepts not only shaping discussions about Hawai‘i, but also expanding a conceptual apparatus that can help us think about the world in a more comprehensive and engaging way?

Connelly: I guess the first thing for this question is about who it is actually for, and how do we make different ideas across language, culture, and vernacular accessible? Accessible in a way so that the communities who are going to engage these ideas can transform them in a way that works for them.

Garcia: Right.

Connelly: So with vocabulary there’s an issue around concepts from different backgrounds with different foundations and what’s considered standard and what’s considered underground or beyond, in the periphery. And so that kind of gets back to the idea of calling the bulk of architecture “white studies” which is like acknowledging that there’s different foundations and stuff like that.

In terms of the idea of vocabulary as metaphor, it’s a double-edged sword because culture is real, it’s not a metaphor. But also there is poetry. It’s so beautiful to think about the way different languages inform concepts that we define in English or describe in English.

So, for example, in Hawaiʻi, on an island, the most crucial resource is fresh water. That’s a crucial resource for all of us as humans worldwide. We all need water… The Hawaiian word for water is wai, W-A-I, which has a really important meaning. All the different places where the word wai appears in the name tells you it has something to do with water. For instance, Waikīkī is about spouting waters. There is a word for saltwater which is kai, like the ocean, but freshwater is wai.

And so, the word it’s very, very specific. But also wai means blood. It means sap. It means bodily fluid. Wai can name things that come out of life or names life forms that require fresh water. Even then when we think about wai, or about freshwater, there’s also these other meanings of the derivatives of freshwater that communicate meaning, connection, and importance. Embedded in the word wai is also an understanding of the link between freshwater and life. Then, for example, when you put the word wai together, to spell wai-wai, that means wealth. And then when you say the word kānāwai, that’s the word for law, possibly related to the distribution and regulation of freshwater.

On a conceptual level, I do think there is value to learning a native language to reintroduce us to concepts that we might take for granted. I think it is a really important way to reframe our understanding with nature. Another word I appreciate is the word for a current, which is au. For me this word totally transforms architecture and the issue in western philosophy around the distinction between space and time. And the question of how understanding dynamics influences design. But the word au, or current, also means a period of time, and according to Rubellite Kawena Johnson it is a word that combines the concept of space, time, and flow into a single construct.

Indigenous understanding of space and time and flow is something that is integrated and combined, unlike concepts in colonialism that tend to split things up. For me, that really changes the starting point for conversations around design theory and the philosophy of architecture. But then there is the danger when native words are appropriated in ways that actually promote settler colonialism. Like the word ahupua‘a, which means land division, names a concept of resource management. It names a concept that involves how people and resources move across the different zones of the environment from mountain to ocean. Those zones or wao, wao akua and wao kanaka indicated where people live, kanaka, and where the gods live, akua, which ultimately creates a distinction between how different ecosystems across the island are more sensitive to human habitation than others.

Today that sort of understanding becomes reduced to a metaphor about the mountain to ocean connection that oftentimes is appropriated by planners and developers who do not necessarily understand the concept. It’s like greenwashing but worse…

And so I would sort of say that, you know, the ahupua‘a is an example of a Native concept that has been abused by developers and city planners. And then the worst is when developers use Native language to name luxury towers. It’s kind of like appropriation of the metaphor which takes advantage of the power of its ability to enchant people but they’re enchanting them, not for social justice or change, but to hide settler colonialism and capitalism in plain sight.

So when it comes to language, it is kind of a tricky balance. It’s not enough to include Native language or to pay off a group of elder descendants of an area so they can say the development is good when really it’s not. On my end, I’m really interested in how words like ahupua‘a can be translated to inform architectural terminology that’s more appropriate for the actual vernacular of native built environments. I could go on and on and on. There is also the word for land, which is ‘āina, which means ‘that which feeds,’ which is the concept for land that is about sustenance and reciprocity versus land as an object. So in the end, the language of every culture has something to offer in understanding and relating to the world around us.

According to scholars like Kamana Beamer, when the Europeans came over it was actually Hawaiʻians who were really interested in building trade partnerships because exchange is an important part of the culture to begin with. The culture already had a concept of naval trade between the islands based on the history of naval trade, between Hawaiʻi and Tahiti and Hawaiian Samoa, Aotearoa. Even historically you have sweet potatoes in Polynesia because between Southeast Asia to South America there was like a long history of tens of thousands of years of trading, you know, a sweet potato, breadfruit. Again like all these kinds of things, like when you look at the plant culture, you can definitely tell that there’s this long history of transoceanic interaction involved across the Pacific.

So early on, Hawaiians actually go out to the east coast seeking to learn English a decade before. The missionaries don’t just arrive in Hawaiʻi but are literally invited by Hawaiians to help translate the language into written text. So there is a lot of agency behind Hawaiian culture that most people don’t recognize in the trope of missionaries and colonization and western domination over Native peoples who put up a good fight. Hawaiʻians sent out diplomats to go to the east coast to learn English first and then invite missionaries to come to Hawaiʻi to find a way to create the idea of a language base to interact with Americans and the British.

So anyway, I just think there’s a really powerful archive in Hawaiʻi that really is unparalleled in many parts of the world, because Hawaiʻi as an Indigenous culture comes online so late into the game and then Hawaiians are so fast to not become colonized, but to appropriate the symbolism of Western culture, in ways resisting the forces of settler colonialism because you know, at the same time, the same things are happening where the Hawaiian populations are decreasing because of disease. So there is an awareness embedded in the survival of Native languages.

By 1840, Hawaiʻi was the most literate country in the world. In the 1840s it became a constitutional monarchy where the kings were elected. Hawaiʻi has the oldest public school west of the Mississippi. So all these things about the history of knowledge in Hawaiʻi have been retained and so that’s where the language comes in. There’s at least another hundred years of work to do in terms of unpacking the language, going through the archive and remembering a native concept of architecture and understanding what the environment means through that lens.

Garcia: Is there a word or concept in Hawaiʻi for what reparations should be, or whatever system is going to take place to fix or to replace what has been happening?

Connelly: I’m not sure, but that’s a really good question. My first instinct is to consult with my godsister who is a translator, and also an expert editor. So I would probably go ask them if this concept of reparations exists. Because I’m not a fluent speaker. What comes to mind are groups doing reparations-based work we call āina orgs. They’re basically on-the-land organizations that are focused on some aspect of cultural practice or ecosystem restoration through cultural practice, restoring food systems. For instance, the reconstruction of Native fish ponds, wetlands, taro fields, the restoration of sacred sites including religious sites that are tied to ceremony and observation necessary to continue cultivation and understand the cosmology, when to plant, how to remember and transmit knowledge, etc.

When to eat certain things, when not to eat certain things because they were spawning or exploring mechanisms in place to maintain the resilience and regenerative ability of all the small island. Those āina orgs often describe the work as mālama ‘āina or ‘āina aloha, meaning to care for the land, to love the land.

A lot of significant work goes into it, which has to get funded somehow. It’s an investment of people and money. And so there’s a huge nonprofit sector in Hawaiʻi that supports this work, but they’re mainly grant-based or donation-based. So āina orgs are the first thing that comes to mind in reparations directly to people or giving reparations to networks of people.

I’ve gone through different scales of referring to the concept of reparations in my own work. One being the restoration of [Fort DeRussy in Waikīkī] back into a fishpond, which was among the first fishponds to be filled by the military. I’m in this as part of the climate infrastructure, climate change infrastructure. Like this can go instead of the local taxpayers having to front one third of the cost, which should be completely covered by the military reparations.

But then there’s also education. If Hawaiʻi was one country, we would probably have more than one architecture school. I mean some cities have more than one architecture school and for the entire state we have only one architecture school that’s part of the land grant university system. And so there’s definitely an issue there. I’ll get back to you about an actual word for reparation though. I’m curious about what that would be. But for whatever it would be, it would relate to some sort of form of ina, which is some integration of people on the cultivation of land.