Abstract

For nearly eighty years, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) has done its mapping—everything from the surface of the moon to the compound hiding Osama bin Laden—from the city of St. Louis. In 2017, this federal agency pitted three regional sites against each other in the competition to host their new billion-dollar headquarters. Two years later, a site of nearly one hundred acres of “underdeveloped brownfields” in North St. Louis was selected to go from “eyesore to economic boon” as the host of this moated and militarized spy headquarters.Footnote1 This supposedly catalytic development eradicated nearly half of what was left of the St. Louis Place neighborhood following decades of erasure from urban renewal, malignant neglect, and unethical real estate transactions. While the project was touted as a massive win for St. Louis due primarily to preserving city income tax dollars, this essay examines how existing measures of success that conflate economic growth (or even simply economic preservation) with progress fail to capture the real social, environmental, and economic costs that development can bring. It considers how the difficult-to-measure aspects of city sociality—rootedness, optimism, opportunity, and social resilience, for example—are critical in recognizing and elevating the importance of spatial justice in our design decisions and design pedagogy. This paper explores the true costs of the NGA relocation to North St. Louis by measuring a broad range of social and economic factors ignored by the city’s assessment. It also considers a second adjacent project, the proposed Brickline Greenway, and explores how its more inclusive objectives begin taking small steps towards repair. Speculative design work from the Master of Urban Design studio at Washington University in St. Louis provides alternative mapping and design solutions that further this paradigm shift.

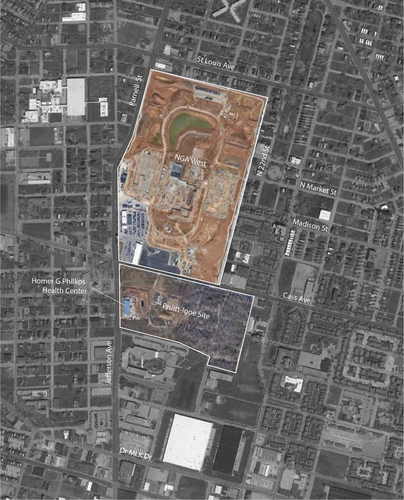

In April 2019, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) revealed its latest plans for a new NGA West campus in North St. Louis. This federal mapping and intelligence gathering agency has been a part of St. Louis since 1827, when it supplied small arms to early western explorers from the St. Louis Arsenal, the very building it currently occupies.Footnote2 After nearly a century of growth and transition in this historic building—where the agency mapped everything from the surface of the moon to the compound hiding Osama bin Laden—the structure could no longer accommodate the NGA’s technology and staffing needs. The new NGA will occupy ninety-two acres of land in the heart of the historic St. Louis Place neighborhood; this campus will include a 712,000 square foot office building, a limited-access visitor center, two parking garages, an inspection facility, and secured entrances and exits.Footnote3 City leaders claim that it will be a “project that will transform a swath of [the city] hollowed out by decades of disinvestment,” yet they fail to own their responsibility for the decades of urban erasure, unethical real estate transactions, and malignant neglect that instigated and perpetuated the demise of this African American neighborhood in the first place ().Footnote4 To add insult to injury, the new NGA will sit adjacent to the site of the infamous Pruitt-Igoe housing project, part of the city’s urban renewal program in the mid-1950s that cleared a previous portion of the neighborhood to build thirty-three eleven-story highrises (). Intended to provide quality housing for low-income city residents, Pruitt-Igoe, after notorious neglect by the city followed by low occupancy and high crime, was demolished in the 1970s, further contributing to the gutting loss of over 80 percent of the area’s population.Footnote5 Dr. Mindy Fullilove, American social psychiatrist and professor of urban policy and health at The New School, calls this unwelcome displacement “root shock” defined as “the traumatic stress reaction to the destruction of all or part of one’s emotional ecosystem.”Footnote6

Figure 1. Site of the new National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) West Campus located in the heart of the St. Louis Place neighborhood in (from left to right) 2016, 2017, and 2018. Image credits, left to right: David Carson, St. Louis Post Dispatch; Chris Lee, St. Louis Post Dispatch; provided by NGA West.

Figure 2. NGA West under construction and the beginning of the redevelopment of the former Pruitt-Igoe site, 2022. Image: Google Maps, notations B. Kim.

But the NGA and hundreds of current projects like it across the US perpetuate discriminatory practices of urban renewal—community displacement, land clearance, forced relocation, and so on—in the name of economic development and prolong the neoliberal paradigm that prioritizes development dollars over all other goals. Under this encompassing agenda, the consideration of social costs—both visible and invisible—is not typically part of the equation. There can be no repair for damages and disinvestments that remain unrecognized and unaccounted for.

Getting to Measuring What Matters: Alternative Metrics

What we measure reflects and reproduces our priorities. The rise of neighborhood-scale planning and community-oriented decision-making in recent decades has popularized sustainable development strategies and certification frameworks that standardize neighborhood-scale sustainability.Footnote7 Architects, landscape architects, and urban designers use these constructed measurement frameworks of sustainability like LEED Neighborhood Development (ND) (created by the US Green Building Council and the Congress for the New Urbanism), STAR (Sustainability Tools for Assessing and Rating) Communities, Sustainable SITES Initiative (for land development), and others that quantify a wide range of metrics, but almost always mask the true costs of the “pro-growth” model. These generalized frameworks primarily focus on readily measurable physical factors, often with a heavier emphasis on environmental aspects, while limiting social accountability to criteria such as mixed-use zoning, transit availability, and sidewalk presence.Footnote8 They entirely lack indicators to measure long-term impacts, particularly the impacts of new development on already established neighborhoods.Footnote9 Though recent adaptations of these metrics frameworks now include measuring the value of community input, the inability to adapt to local contexts and the inherent top-down approach of these tools de-emphasize meaningful local participation and disconnect residents from the decision-making process.Footnote10 Criteria such as “community outreach and involvement” and “mixed-income diverse communities” from LEED ND count as voluntary bonus points, but are not necessary for certification.

Rather than a neighborhood-scale metric, the NGA team chose to use LEED Silver Building Design and Construction (BD + C) and Net Zero Energy certification. These frameworks focus on the design and construction of the building alone and exclude any measured accountability for compactness of development, walkability, mixed use, parking footprint, trees and shade, and so on—all factors that are part of LEED ND—and overlook long-range social and environmental impacts on the neighborhood, as well as any supposed commitment to neighborhood connectivity.Footnote11 Though the NGA’s public narrative claims the project will offer future redevelopment and regeneration for neighboring communities, the fortress-like barrier of the NGA property bears little resemblance to the “seamlessly integrated” campus NGA director Robert Cardillo and then-Mayor Slay promised at the time the site was chosen in summer 2016.Footnote12 Renderings showing tree-lined streets with what appear to be public parks and baseball diamonds were later revised to eliminate any hints of public amenities. The current site plan further barricades the main building between two parking garages and a 500-foot fenced perimeter of non-publicly accessible turf. The political narrative behind the site selection and original design was to “recruit the next generation of intelligence professionals seeking the type of urban, car-optional lifestyle the City provides”Footnote13—an ironic statement as the surrounding neighborhood struggles with high rates of vacancy and poverty, and a lack of public transit, much of these the result of previous, top-down social and spatial injustices.Footnote14

The frameworks listed previously do little to directly address the impacts that neighborhood clearing has on existing communities, or the long-term impacts of historical discrimination. Alternative metrics must be sought or developed to fill the gaps if these issues are to be prioritized. We posit that the concept of “measuring what matters” aims to do just that—to prioritize metrics that are often elusive, ignored, or misrepresented in order to account for qualitative and social gains and losses. The new field of ecological economics models this kind of paradigm shift away from the unlimited resource, growth-at-all-costs neoliberal capital model towards the value of natural resource preservation and ecological systems (including humans).Footnote15 Unlike traditional economics, ecological economics recognizes the limited resources of the natural world and prioritizes their value. Genuine Progress Indicators (GPI), a metric system based on ecological economics, contrasts the widely used Gross Domestic Product (or GDP) measurement of “success” in three primary ways: it separates “good” dollars from “bad” dollars (like building schools versus going to war); it recognizes the costs of losses (like the loss of clean air and water to contamination), or the erasure of cultural history (like institutional memory or local landmarks); and it counts the value of often intangible factors like work in the home or intergenerational relationships. Measuring what matters, in an equitable world, negatively accounts for not only the seemingly intangible costs of conditions like root shock or the loss of tree canopy, but also rewards the value of difficult-to-measure, often qualitative benefits like personal agency, community empowerment, and social network preservation.

Like many postindustrial cities still struggling to stabilize, the St. Louis city government and its local business community continue to see development dollars and tax base growth as the key measure of success. The deals surrounding the NGA project, as we will explain, reveal not only that the accounting is erroneous, but that the accounting is negligent, exclusionary, and socially violent.

But other projects and other types of potential measuring are also happening adjacent to the NGA on the north side of the city. The development of racial equity indicators in 2018 under former St. Louis mayor Lyda Krewson—an outgrowth of the “Forward Through Ferguson” report which was a response to the murder of Michael Brown—represent one of the city’s efforts to track spatial and social injustice.Footnote16 Unfortunately, this has not been a sustained effort as the external funding supporting the project dried up with the dissolution of the larger Rockefeller Resilient City initiative and city government failed to expand the investment in tracking—and ultimately rectifying—these metrics.

The New NGA West and the St. Louis Place Neighborhood: A Development Case Study

To challenge these types of growth-at-all-costs development and reinvestment strategies, the existing frameworks for measuring urban renewal must identify and examine the missing costs in models used by the city. Given the complex history of urban renewal in St. Louis, this latest removal of community members from the St. Louis Place Neighborhood beginning in 2015 should be considered in a long historical context as just the most recent chapter of multigenerational community destruction and dislocation, contributing to decades of localized root shock. By the NGA’s own standards laid out in a Vision Framework that prioritizes growth in the areas of geospatial technology, sports, and logistics, St. Louis Place of the 2010s was a blighted neighborhood of vacant lots, high crime, toxic soil, and disintegrating infrastructure.Footnote17

Yet documented interviews of the recently displaced residents identified St. Louis Place as a vibrant social space and home to a tight-knit community.Footnote18 At the time of the NGA proposal, several formal and informal businesses and historically significant multigenerational residences contributed to the neighborhood’s value. The limited scope of the city’s approach to measuring the value of this neighborhood failed to include a range of human costs and the loss of informal or intangible benefits, which created the illusion of a massive net gain by the city. Had the government measured the St. Louis Place neighborhood’s current spatial and social community value instead of using a tax-preservation, growth-oriented measurement, the projected cost of building the new NGA would have included an accounting of the lasting consequences of neighborhood erasure rather than an overly simplistic compensation amount based on current market housing value. Had they also measured the cumulative cost of decades of manipulation and deprivation, the city debt would have been astronomical.

Measuring these kinds of complex and often intangible factors is not easy. In an attempt to rectify these gaps and show the city’s severe blind spots in determining the true costs of the new NGA, it is critical to measure both spatial and social costs and benefits. Sociologists and urban geographers have long tried measuring neighborhood change by studying disinvestment, decline, socioeconomic shift, and discriminatory practices.Footnote19 More recent studies have focused on unpacking the complex relationship between inner city investment, gentrification, and displacement, but are often unable to fully capture the dynamic nature of population change. The shift from qualitative analysis of specific neighborhoods to large census tract quantitative data sets have further complicated matters. Finding data that not only measures physical, cultural, economic, and demographic shifts, but is also reliable and readily available, has resulted in numerous approaches that only measure particular aspects of neighborhood change such as demographic changes or changes in housing stock.Footnote20

New quantitative models have tried to address this. The Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity’s (IMO) Neighborhood Change proposes a four-dimensional model that differentiates between overall growth, low-income displacement, low-income concentration, and neighborhood abandonment across generations. Although this methodology addresses some of the complexity necessary to analyze various aspects of neighborhood change over time, like many quantitative methodologies such as the Displacement Risk Index, Index of Displacement Pressure, and Federal Reserve study of Gentrification and Residential Mobility, it still fails to apply to neighborhoods that don’t fit into the typical image of rapid displacement and gentrification.Footnote21 Due to the slower and intergenerational “serial forced displacement” that has been taking place in St. Louis since the turn of the century, these kinds of metrics do not identify St. Louis Place as a neighborhood at risk.Footnote22

This case study aims to measure the true costs of the NGA relocation to North St. Louis, utilizing a mixed-methods approach that links both quantitative and qualitative data to triangulate information about neighborhood change.Footnote23 The case of the NGA relocation demonstrates how a neighborhood that does not, according to conventional quantitative data metrics, appear to illustrate any significant sociodemographic shifts, can actually still be experiencing ongoing historical displacement. Though the scale of that displacement may appear smaller than St. Louis’s urban renewal past, the trauma to the individuals and neighborhood remains.

Measuring Social Capital

It was the loss of a massive web of connections–a way of being–that had been destroyed by urban renewal; it was as if thousands of people who seemed to be with me in sunlight, were at some deeper level of their being wandering lost in a dense fog, unable to find one another for the rest of their lives. It was a chorus of voices that rose in my head, with the cry, “We have lost one another.” Footnote24

Measuring social capital is often used as a tool to evaluate the social sustainability or the well-being of residents and quality of life within neighborhoods.Footnote25 Neighborhood social capital specifically looks at interpersonal interactions—social networks, trust, shared norms, reciprocity, sense of belonging, and care—between residents in the same neighborhood. This “massive web of connections” is often a collective asset created by generations of long-standing communities that increases life outcomes and resilience.Footnote26 Growing literature across various disciplines including environmental psychology, urban design, social work, and geography illustrates how neighborhoods that support frequent interactions between residents increase social capital. Because measuring social capital varies widely depending on the disciplinary underpinnings of the researcher, methods of identifying the catalysts for robust social capital in the built environment range from parks, libraries, sidewalks, and benches to transportation networks and civic systems.Footnote27

Mindy Fullilove uses the concept of root shock to explain the impacts of serial forced displacement on African Americans, including development-induced displacement and gentrification.Footnote28 She defines community-level root shock as the loss of interpersonal ties and social capital generated by reciprocal connections, which increases the risk for stress-related diseases across entire populations and multiple generations. This trauma and destabilization caused by displacement is a direct result of both historic and current policies and cycles of serial displacement including segregation, redlining, urban renewal and planned shrinkage/disinvestment, deindustrialization, mass criminalization, gentrification, HOPE VI, and foreclosures.Footnote29 For cities such as St. Louis that have enduring legacies of both direct (forced physical relocation, increased housing costs, evictions) and indirect (homeownership exclusion, exclusionary social spaces) displacement, using Fullilove’s root shock concept to study investment-related displacement provides a more comprehensive and cumulative lens that contextualizes intergenerational trauma.

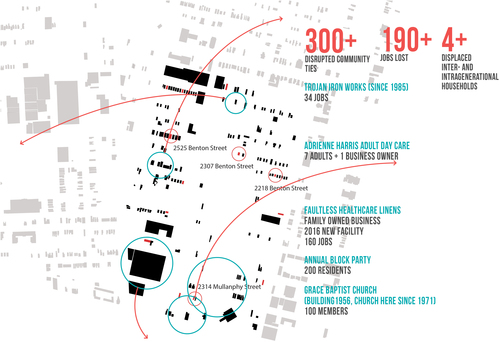

In this research, social capital is used to identify the spaces and spatial conditions that facilitated distinct interpersonal ties between residents and the neighborhood, the last of which were demolished to make way for the NGA relocation. This approach tries to quantify the social network disruption and displacement that is not recognized or compensated by the city. To measure the social capital loss, the homes, businesses, and community spaces that were destroyed to make room for the NGA project were mapped and analyzed. Adrienn Harris’s Adult Daycare Center, Iron Trojan Works, Grace Church, Faultless Healthcare Linens, and the green space on 2134 Mullanphy often used for community gatherings were all served formal eviction notices in 2016 as part of the relocation. Mapping these five spaces and their social characteristics shows that over 500 people’s social ties were disrupted by the very latest clearing of the site including the displacement of 100 parishioners and their fifty-year-old church, the loss of 190 jobs, and the uprooting of the last four historically inter- and intragenerational households in the neighborhood ().

Figure 3. Locations of properties impacted through eminent domain in the St. Louis Place neighborhood for the relocation of the NGA and the social costs of their displacement. Image Kim and Samuels.

The City of St. Louis created a $1.6 million NGA displacement fund to help relocate homeowners displaced from the St. Louis Place neighborhood. Little data, however, is available on how much of that funding went to the residents themselves. Between the numerous lots bought by local developer Paul McKee under a range of various business and personal aliases and the inflated property prices he charged the city for this development, it’s unclear who received funding, and how much.Footnote30 Census block data, property records, court documents, interviews, and news reporting tell a complicated story.

Mapping this meant first collecting a combination of building density loss and land ownership data that was used to isolate the number of occupied buildings that were lost both before and after the NGA site clearing. This map was then overlaid with information from court proceedings that detailed the specified residences and length of occupancy to isolate owner-occupied homes from property owned by McKee, his aliases, and other absentee developers. Of the sixteen compensated properties detailed in the NGA site-related court eviction notices in 2016, the map shows that only a fraction were owned by St. Louis Place Neighborhood residents ().Footnote31 Those owners received just 38 percent of the total eminent domain relocation cost.Footnote32 The other 62 percent was paid to developers and nonresidents, including McKee, whose land banking and intentional neglect had been driving the market housing value of the neighborhood down for years.Footnote33

Further results show that the city’s “generous” buyout at market price averaged only $157,000 per household, a portion of the cost of comparable move-in ready homes in nearby neighborhoods.Footnote34 Though city officials may argue that such compensation and the allocated $1.6 million displacement fund adequately covered the the cost of the loss of homes in the neighborhood, the total amount not only fails to consider the loss of intergenerational wealth, but also the additional burden of finding and affording equivalent housing in a new neighborhood. Furthermore, it entirely disregards the intangible costs of emotional displacement and fracturing of social relationships as outlined above and supported by Fullilove and others. Although the narrative from the city and NGA developers discounts the St. Louis Place neighborhood as an undesirable community due to the relative low market value of its housing stock, the social bonds documented above indicate otherwise.Footnote35 The insufficient payouts captured neither the long-term intentional devaluation of property by neglectful owners like McKee nor the spatial and social characteristics of the neighborhood.

Adopting this alternative framework of measuring social capital demonstrates that despite the narrative of fair compensation, the people and their community in the St. Louis Place neighborhood were exploited by the city’s decision to relocate the NGA campus to the Northside. Though material costs were obviously downplayed, social costs were entirely ignored.

The Tax Myth

In addition to the social costs that were not calculated or acknowledged, the claims of a $2.4 million annual tax benefit—the cornerstone of the city’s argument for keeping the NGA in St. Louis—fail to tell even the full financial story. Part of those city taxes is not gained but retained from the relocation of the NGA within the city limits. A portion of those tax benefits is projected city earnings taxes, which are based on additional employment the NGA is claiming—taxes that would be collected regardless of their chosen site as long as the facility stayed within city limits. A full range of state, federal, and local incentives must all be considered, as funding allocated for the NGA means other needs move down the list of priorities or get eliminated altogether. In addition to a $1.75 billion federal pledge, $131 million in state money was set aside to fund the project’s construction, including a $36 million state Brownfield Tax Credit to build on the now conveniently vacant lot. The city of St. Louis and the state of Missouri allocated an additional $1.5 million per year city tax earnings and $5.85 million per year state tax earnings over the next thirty years for the project.Footnote36 By 2045, the total state and city tax spending alone will cost the city more than seven times the estimated additional tax earnings from the NGA West Campus.

Lastly, the piecemeal land acquisition is an ongoing narrative of disenfranchisement. Though precise dollar amounts have not been verified, the properties owned by McKee and his related shell companies, for which he received initial tax incentives in 2007 and 2013 estimated at $95 million, then had to be repurchased by the city before they could be offered at no cost to the NGA. Additionally, the city took out a $20 million loan in 2015 to pay for those assembled lots, far more than the $600,000 price originally paid by McKee.Footnote37 Clearly, the advantages fall disproportionately towards the already wealthy and away from those simply struggling to hold on to their hard-earned assets. Over the course of four decades of displacement, from Pruitt-Igoe to the NGA, 19,542 residents in the St. Louis Place neighborhood and immediate NGA vicinity—a 91 percent drop from 1950 to 2016—were displaced ().

Figure 5. Figure-ground drawings based on Sanborn maps and aerial images of census tract 1271 beginning in 1950 and including 2000, 2010, 2015 and projected 2025 maps (spatial data between 1950 and 2000 is missing). The last two maps show the NGA West site overlaid in red. The final map shows the latest footprint (2019) with a primary center building and a parking garage on either side. The graph below shows the drop in total housing units and population from 1950, when the City of St. Louis was at its peak population, to 2019, a drop of over 90 percent. Image: Kim and Samuels.

Today, McKee owns more than 1600 parcels surrounding the site of the NGA campus, mostly vacant, decaying, and continuing to devalue neighborhoods. Few, if any, of the buildings remain salvageable, far from the 152 buildings McKee promised to rehabilitate in 2013. Over 200 of the buildings owned by McKee have been condemned or destroyed, including the historic Clemens House, a site he promised to renovate into senior apartments.Footnote38 The St. Louis Vacancy Collaborative estimates that 46 percent of the vacant buildings in St. Louis are owned by the top ten private owners in the city who owe $4.9 million in unpaid property taxes, $7.6 million in billed forestry maintenance fees, and $3.5 in unpaid vacant building fees and fines for a total of $16 million.Footnote39

McKee, in response to these accusations of negligence, points to signs of new investment: the $19.6 million Zoom gas station and GreenLeaf Market grocery on North Tucker Boulevard, as well as a partnership with a builder constructing several energy-efficient houses in the St. Louis Place neighborhood. McKee was sued in 2018 for over $7 million by the city for fraudulent development promises and settled out of court for less than half a million dollars admitting no liability, fault, or wrongdoing.Footnote40

Infrastructural Opportunism: The Brickline Greenway as a Case for Repair

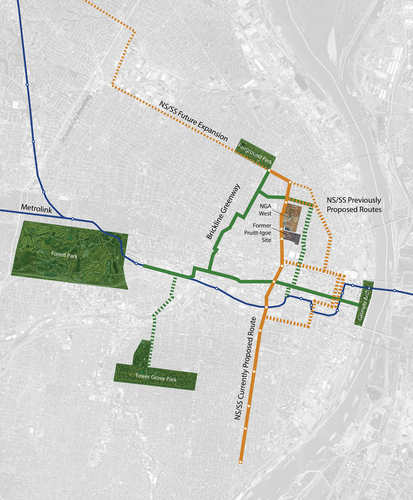

Two substantial proposed infrastructure projects, the Northside/Southside (NS/SS) Metrolink expansion and the Brickline Greenway, will pass within blocks of the new NGA site (). Both recognize that they must be equity-based investments aimed to bolster and benefit a long-mistreated population as part of their objectives. Although low ridership numbers make a NS/SS Metrolink expansion in North St. Louis hard to justify for transit needs alone, equity remains a chief concern with residents suffering from disproportionately excessive commute times, insufficient job opportunities, high poverty rates, and radically impacted life expectancies. Luckily, federal funding sources now take these equity concerns into consideration in addition to transit demands. This $2 billion project will pass through fifteen wards and twenty-three neighborhoods, including a dozen stops in North city, one—though not on the neighborhood preferred route—at the door of the new NGA.

Figure 6. The Brickline Greenway and the Northside/Southside Metrolink expansion represent millions of dollars of future investment in North St. Louis. These two projects have the potential to connect North and South city to each other and to the more affluent east/west corridor. Image: Kim and Samuels.

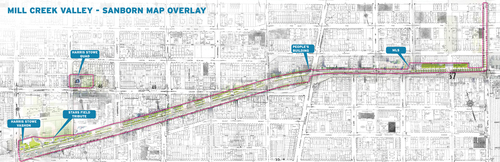

The Brickline Greenway (called Chouteau Greenway initially) was an international, two-phase design competition starting in 2017 for a multi-million-dollar, multimodal path funded by tax-supported public agency Great Rivers Greenway (GRG).Footnote41 On the tails of the NGA development site remediation, Great Rivers Greenway (GRG) unveiled the winning Brickline Greenway plan to the public. The team, led by Stoss Landscape Urbanism, articulated a framework with numerous parks, business and arts districts, transit corridors, and educational institutions along the twenty-mile route.Footnote42 The route also connects key cultural resources including the Griot Museum of Black History, located in the St. Louis Place neighborhood on the northern edge of the NGA site, Grand Center Arts District, and the historical site of Mill Creek Valley.

Over the course of the competition, the route evolved from an east/west-only route to also connect North and South St. Louis in an effort to more equitably distribute resources to the neighborhoods in deeper need. It was originally planned as a “Park to Arch” connector that would run from the edge of Forest Park, the city’s 1,300-acre green jewel, east to the newly renovated, multi-million-dollar St. Louis Gateway Arch grounds. Many critiqued this route as connecting “money to money” due to the existing affluence and growth in this central corridor and the exclusion of parts of the city which most need the investment, connection, and attention. This change was a result of expansive engagement with an active Artists of Color Committee, Design Oversight Committee, and Community Advisory Committee, in addition to direct feedback from the finalist competition teams. These engaged stakeholder groups, particularly the Artists of Color Committee, also encouraged GRG to invest in memory work as one form of social repair. St. Louis-based multimedia artist, musician, and filmmaker Damon Davis, who was a member of the winning team, is designing a mile-long memorial to the Mill Creek Valley community where 20,000 Black residents were displaced for the construction of Interstate 64. The Mill Creek Valley memorial is just a mile south of the old Pruitt-Igoe site and the new NGA.

Damon Davis, despite growing up in St. Louis, noted that he had no knowledge of Mill Creek Valley before the design bid and wanted to create a monument to the displaced residents to rectify those kinds of memory gaps for others. Davis’s Mill Creek Valley Monument, a retracing of demolished houses and eight hourglass pillars that represent time and lost collective history, will occupy the east end of that segment, taking up the southwest corner of the site of a new Major League Soccer Stadium (). “There was an intention behind removing these people from the narrative of St. Louis and now there must be the same intention behind bringing their stories back to life,” Davis said in an interview published in The Guardian. This one-mile segment of the Brickline also includes Stars Park, the former home of the St. Louis Stars of the Negro Baseball League; Vashon Community Education Center, site of the second Black high school in the city; Harris-Stowe State University, a historically Black public university; and the new Don and Heide Wolff Jazz Institute, and National Black Radio Hall of Fame.Footnote43

Figure 7. Damon Davis, local artist, musician, and filmmaker, is part of the winning team selected to design the Brickline Greenway. His contribution is a mile-long art piece designed to commemorate the 20,000 Black residents displaced from Mill Creek Valley for the building of Interstate 64. American for Arts Submittal.

Between the investment in the NS/SS Metrolink, the Brickline, and the NGA, billions of dollars could pour into the north side of St. Louis in the coming decades. Some of that is already being secured from the federal Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed in late 2021. As architects, landscape architects, and urban designers facing this moment of infrastructural opportunism, our research and creative responses could help guide the design and implementation of these projects and the future of these neighborhoods.

North Side Infrastructural Opportunism: The Green New Deal Superstudio

If what we measure reflects and reproduces our priorities, then measuring our progress, or lack of progress, toward repair is a critical step in recognizing and elevating the importance of spatial justice in our design decisions and in our design pedagogy. Projects like the NS/SS Metrolink and the Brickline Greenway are infrastructural opportunism projects—major investments that can be leveraged for greater social and environmental benefits beyond their singular mobility purposes.Footnote44 These projects often serve as catalysts for the first semester of the urban design program at Washington University in St. Louis, with the NS/SS Metrolink garnering repeat appearances in studio and serving as the basis for the Mobility For All by All research project.Footnote45 In addition to generating the conversation on alternative metrics described earlier in this essay, the Mobility For All by All project also funded local artists/activists to experiment with creative forms of community engagement along the NS/SS line.

The studio uses strategies of infrastructural urbanism, interdisciplinary systems-based urban design thinking, and a set of eleven next generation infrastructure criteria derived from previous research and teaching.Footnote46 These strategies aim to transform the infrastructural prototype, broaden the participatory process, and measure what matters to shift the prototype towards infrastructure that increases equity, reduces resource use, and supports a vital, inclusive, and productive public realm.Footnote47 Through the studio’s partnerships with the agencies and organizations in charge of project implementation, the students’ design propositions can be developed from a more politically neutral position, showing stakeholders alternative possibilities to those often produced when elections are at stake, nontraditional thinking is discouraged, and status quo standards, processes, and procedures are dominant or exclusive options.

During the early peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, when most design schools were entering a second semester of remote learning, the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) put out an international call inviting designers to join a collective Green New Deal Superstudio, adopting the policy framework introduced by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Edward Markey into design and planning studio briefs and projects. The Green New Deal is a unique federal initiative not only for its bold stance on climate change—calling upon the federal government to wean the US off fossil fuels—but also for its explicit recognition of the interdependence between environmental and social outcomes. Its action items—net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050; good, high-wage jobs; infrastructure investment; clean air and water, healthy food, and access to nature for all; and promotion of justice and equity through prevention and repair—point toward a radically different and far more optimistic and equitable future than the typical capital-driven path. The GND Superstudio prioritized decarbonization, jobs, and justice specifically. As part of the Green New Deal Superstudio, the Fall 2020 WashU urban design studio focused on the northern segment of the Brickline Greenway, which is proposed to run past the NGA and the old Pruitt-Igoe site and intersect the proposed NS/SS Metrolink route, as its infrastructural catalyst.

This studio, titled "The Land on Which We Stand, the Stand on Which We Land," was guided by two primary motivations—the momentum of global social uprisings for racial and social equity and their particular resonance in St. Louis, and the emergence of the Green New Deal as an optimistic, big-vision plan for more socially just and environmentally conscientious cities. This studio was the first that Samuels taught at Washington University to incorporate a new next-generation infrastructure criterion—number 12, Reparative. As described in Samuels’ book, Infrastructural Optimism:

Next-gen infrastructure must also repair the damage done and the violence caused to populations, human and nonhuman, and communities that have been oppressed, abused, or erased from lands where we plan to build. Criterion number 12 is reparative; this means taking into account that damage, but also incorporating steps to somehow make amends. Beyond being socially productive, reparations must reprioritize resources, add agency, and create optimism for those who have been most impacted by institutionalized structures of racism, erasure, and exclusion.Footnote48

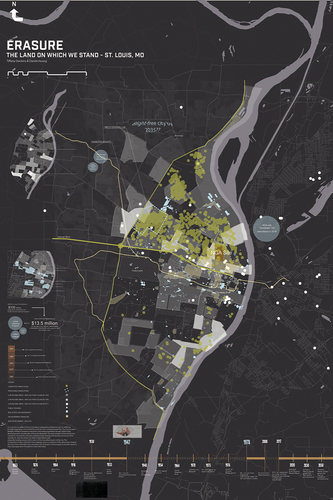

Students began the semester with deep mapping, researching, analyzing, synthesizing, and visualizing the complicated spatial, social, environmental, and temporal history of this Northside site. In addition to mapping climate impacts, energy, water, and transportation, students also mapped Power (contestations, ownership, and stakeholder relationships), Potential & Opportunities (including transportation as a form of financial and social access), Entries & Exclusions (showing historical and current layers of erasure, wealth, and social services) (), and Love & Bread (elaborating social connectivity, education, and history). Analysis and synthesis of this content exposed both the discrepancies between the different geographical areas of St. Louis, and the depth of history and cultural suppression and opportunities on the Northside of the city.

Figure 8. Erasure map, Master of Urban Design studio Fall 2020: "The Land on Which We Stand/The Stand on Which We Land." Following decades of erasure through eminent domain, urban renewal, and neglect, this map tracks the newest investment in North city demolition, overlaid on low-income areas and locations of tax abatement. Team members: Tiffany Dockins, Daniel Huang.

Figure 9. Hindrance to Wealth map, Master of Urban Design studio Fall 2020: "The Land on Which We Stand/The Stand on Which We Land." A wide range of contributing factors hinder residents’ ability to access and accumulate wealth. Recognizing these interdependent factors, this map explores the relationship between poverty rates, eviction, life expectancy, access to health insurance, and low educational attainment. Team members: Tiffany Dockins, Daniel Huang.

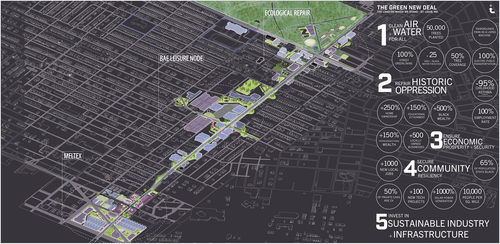

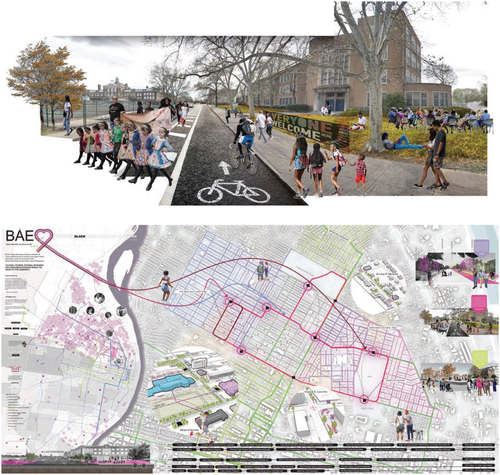

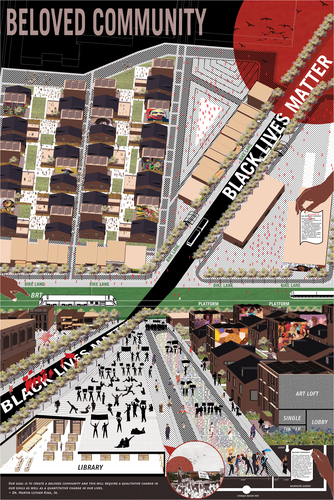

Three teams of students created design proposals. The Ecological Repair team designed a green infrastructure mobility corridor that would “repair the historical damage of racial violence present in intersecting neighborhoods in North St. Louis by building social impact through green infrastructure, symbiotic industry, and landscape interventions.”Footnote49 The Black Aesthetic Empowerment team, or BAE, focused on a three-part strategy of BAE Leisure, BAE Memory, and BAE Power, celebrating and reinforcing specific forms and notions of historical and contemporary Blackness grounded in the rich cultural history of the Northside (). Seeding the New North Loop team created a kind of sharing economy between the NGA and its less resource-rich neighbors (). In this proposal, components of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency program, like surveillance technology and business skills, would actively migrate to the adjacent neighborhood and provide micro-opportunities for small businesses or job training to local residents. From that third project, one student branched off to create a fourth proposal, Beloved Community (). As described by the student designer:

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. famously wrote that a healthy society requires an all-inclusive spirit of sisterhood and brotherhood that stands on the twin pillars of economic and social justice. King’s idea of the “Beloved Community” envisions a society based on justice, equal opportunity, and love of one’s fellow human beings. This project proposes using the goals of the Green New Deal to create a Beloved Community by improving access to healthy food, financial resiliency and rebuilding a sense of community in North St. Louis at the corner of Martin Luther King Drive and Grand Avenue, a prominent north/south axis that connects multiple universities, cultural districts and parks. By leveraging previous research that identified significant opportunities in North St. Louis, Beloved Community aims to rebuild at a neighborhood scale sensitive to historical urban fabric but providing new shared space to support community activities and achieve equitable prosperity for all.

Figure 10. B.A.E.: Black Aesthetic Empowerment. Master of Urban Design studio Fall 2020: "The Land on Which We Stand/The Stand on Which We Land." Design Credit: Catherine Hunley, Teddy Levy, Jennifer Wang.

Figure 11. Seeding the New North Loop, St. Louis, MO. Master of Urban Design studio Fall 2020: "The Land on Which We Stand/The Stand on Which We Land." This final project uses the development at the NGA site to seed amenities for the surrounding neighborhood. Design Credit: Bruce Zhao, Daniel Huang, Yu Tang.

Figure 12. Beloved Community, Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, St. Louis. Master of Urban Design studio Fall 2020: "The Land on Which We Stand/The Stand on Which We Land." Design credit: Yu Tang.

“The Stand on Which We Land” is the final studio position, the argument as a collective, the cumulative effort to use design as a form of repair. The final tally of efforts to incorporate the GND values at the end of this studio was consolidated in a single site axonometric drawing that exhibited the values of measuring what matters in terms of the twelve criteria and the objectives of the Green New Deal. This composite drawing brought together the original three projects and totaled, as much as possible, the kinds of impacts that would result from these symbiotic social and environmental efforts. Though as broad estimates of metrics they are incomplete, they clearly prioritize alternatives to the growth-at-all-costs, money-first model ().

Measuring what Matters: Reparations

Throughout history, large-scale public works projects have served as symbolic representations of collective optimism. In 1956, the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act called for 42,000 miles of interstate to knit together these separate “united” states in support of shared prosperity and economic growth. But that prosperity, like the GI Bill and suburban boom, was not intended for everyone. As Fullilove says, urban renewal in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s in the United States—the cause of displacement for up to a million people of color and the eradication of life as they knew it—was root shock at the scale of an entire race. As proven by the case of the NGA, and hundreds of others like it, this historical spatial violence not only goes unaccounted for, it continues to mount.

USC scholar Ange-Marie Hancock Alfaro, when asked to define equity, said it is a step on the path to justice.Footnote50 This metaphorical step has been portrayed graphically numerous times, depicting the difference between “equality” and “equity,” in which the former gives everyone an equal-height step, whether they can then see over the fence or not, and the latter gives everyone what they need to get the same view. Justice tears down the fence and invites everyone into the ball game. But what about repair?

If the twelfth criterion for next-generation infrastructure calls for the reprioritization of resources, addition of agency, and creation of optimism—the critical belief in a self-determined better future—for those who have been most impacted by institutionalized structures of racism, erasure, and exclusion, how do we measure what is owed?

According to the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenants on Human Rights, five conditions must be met for full reparation to exist: (1) cessation, assurances, and guarantees of nonrepetition; (2) restitution and repatriation; (3) compensation; (4) satisfaction; and (5) rehabilitation. Symbolic reparations—monuments, plaques, renaming, public apologies, memory museums, performative gestures, etc.— are important in that they build civic trust and social solidarity by recognizing the dignity of the victims and fostering and substantiating memories of relevant historical facts, but they are a beginning point, not a full solution. Getting even to this point, though, is long and complex, part of an ongoing process that centers inclusive, genuine dialogue and fosters trust in the interest of collective healing. These are the first steps, long before spatial changes can occur.

But spatial change is our medium. When considering billion-dollar investments in revitalizing obsolete—or building new—infrastructure, particularly when deciding where and how to invest, infrastructural opportunism projects must turn into infrastructural optimism projects for our neighborhoods and communities most in need. Infrastructural optimism is based on the concept that everyone deserves to believe in a better collective future, and that investments in infrastructure—our largest public space and the very basis of our quality of life—should contribute to that better future for all of us rather than detracting from it.

In the case of the NGA development, it is clear that the pattern of bestowing financial benefits on some while willfully sacrificing others has furthered the divide, and that spatial injustices will continue. The Brickline planning is making strides to incorporate symbolic reparations through memorials and monuments, but also through inclusive engagement processes and the distribution of some power through committees like the Artists of Color Committee and other diverse neighborhood input. Had Great Rivers Greenway invested first in the North city connector rather than risking running out of momentum and money before the north/south route even gets started, that would have indicated an even bolder step towards equity. The +StL: Growing an Urban Mosaic proposal for the Brickline (one of the four finalist projects) took on a decidedly proactive reparative position by proposing simultaneous and substantial investment in north and south city educational facilities, food sources, job training, and intergenerational housing as literally adjacent and indivisible from the Greenway ().Footnote51 In addition, the proposal offered that legacy families of previously displaced residents would receive a first right of refusal for adjacent properties and business locations, with accompanying no-interest loans, as part of a revitalization and repair package. In that way, lots expected to rise in property value would go to past homeowners who lost generational wealth rather than to developers out for speculative financial gain. The alignment would also serve low car ownership neighborhoods first, unlike the latest route of the NS/SS light rail, which has recently been shifted to stop at the door of the NGA and bypass downtown and neighborhoods to the east of the new NGA altogether. A radical and robust Community Benefits Agreement for the North side, with substantive content developed by local residents and some degree of participatory budgeting, would be a step towards incremental amends.

Figure 14. The + StL: Growing an Urban Mosaic proposal for the Brickline took on a proactive repair position by proposing simultaneous and substantial investment in North and South city educational facilities, food sources, job training, and intergenerational housing as adjacent to and indivisible from the Greenway. Project leads: TLS Landscape Architecture, Object Territories, and [dhd] Derek Hoeferlin Design with L. Samuels and an additional team of arts, economics, design, and community experts.

![Figure 14. The + StL: Growing an Urban Mosaic proposal for the Brickline took on a proactive repair position by proposing simultaneous and substantial investment in North and South city educational facilities, food sources, job training, and intergenerational housing as adjacent to and indivisible from the Greenway. Project leads: TLS Landscape Architecture, Object Territories, and [dhd] Derek Hoeferlin Design with L. Samuels and an additional team of arts, economics, design, and community experts.](/cms/asset/31e49c59-406a-4972-905d-6538d691fb89/rjae_a_2165840_f0014_c.jpg)

The Culpability of Pedagogy

In recent years, efforts have been made to quantify the “success” of individual buildings, neighborhoods, and systems, but holistic frameworks for deep evaluation that include a full range of real social costs and benefits have proven elusive. This is due to many factors, including but not limited to unreliable or unavailable data, necessary effort and time commitment, opaque or erroneous reporting, and the extreme complexity of understanding the workings of systemic, inter-reliant, and often subversive systems. But sheer greed and ignorance are factors as well. The former we may have little control over, but as scholars, designers, researchers, and teachers, we have some influence on the latter. All space is contested space and all design work inflicts costs and provides benefits, some invisible and some ignored. This research informs real action on the ground in St. Louis and exposes the ways in which a narrow scope of assessment overprivileges particular measures and, in the process, particular groups of people. Not only is this discriminatory, but it also fails to consider factors that help produce and perpetuate neighborhoods that support a high quality of life for all and cities that promote and sustain real publicness and vitality. Design practice and abstract studio projects in particular can, intentionally or unintentionally, perpetuate a narrow view of “success” by ignoring the complexity of social (and other) costs all development instigates. There are no empty sites; “vacancy” is never vacant. If we fail to teach the social consequences of design work, those values fail to emerge in our students’ future practices.

Truly reparative infrastructure investment requires guarantees of restoration, prevention, and transformation, girded by the optimistic conditions for civic confidence and inclusivity among all city residents. The right to a better future is inseparable from the larger right to the city. Engaging the complexities of repair through studio work by leveraging real, opportunistic projects and digging deeply into their histories—and their current realities—of spatial injustice, our design propositions can elevate the significance and necessity of repair. Not weighed down by the myopic, dominant (and often political and misguided) metric of “tax dollar saved” or “jobs created” (regardless of for whom), the studio environment can take a more holistic perspective on what matters in the longer-term life of the city. The longevity of relationships gained through committed academic outreach centers, established research institutes, and multi-year engagement projects is necessary to build much-deserved trust and commitment. Our responsibilities as teachers begin by teaching future designers that it matters what we measure and how we account for the importance of human networks and quality of life in the larger scheme of social sustainability.

Though all projects are not intended to be activist urban instigations—nor should they pretend to be when time, budget, and commitment do not fully allow—“measuring what matters” means that, at the very least, we hold ourselves and our students accountable for blindly buying into the default growth-at-all-costs neoliberal system. We must hold our disciplines accountable, too, for demanding and facilitating a more comprehensive list of “what matters” and a more aggressive commitment to ensuring that the measurement of what matters continues to improve.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10464883.2023.2208467)

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Linda C. Samuels

Linda C. Samuels is an associate professor of urban design at the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, where she teaches architecture and urban design studios and seminars on Infrastructural Urbanism, urban history and theory, and alternative sustainability metrics. She is the founder and director of Infra_OPTS, an independent consulting firm in St. Louis and Los Angeles focused on the design, mapping, and metrics of public infrastructure to create more equitable cities. Samuels earned her Doctorate in Urban Planning from the University of California, Los Angeles, where she was a Senior Research Associate at cityLAB. Samuels’ most recent book, Infrastructural Optimism, is now available from Routledge.

Bomin Kim

Bomin Kim is a doctoral candidate at the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. Her research focuses on the dynamic forms of community and the built environment that facilitate social resilience. Her professional work as an architect and sustainability specialist combines modeling, urban informatics, and geospatial data science to explore alternative indicators to create more inclusive and sustainable urban environments.

Notes

1 “Local, State and Federal Cooperation Paves Way for New NGA Facility in North St. Louis – EPA Region 7 Feature,” US Environmental Protection Agency, accessed October 1, 2021, https://www.epa.gov/mo/local-state-and-federal-cooperation-paves-way-new-nga-facility-north-st-louis.

2 “NGA St. Louis Heritage,” National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, accessed November 7, 2022, https://www.nga.mil/history/NGA_St_Louis_Heritage.html.

3 “About Next NGA West,” accessed November 7, 2022, http://www.nga.mil/about/About_N2W.html.

4 Jacob Barker, “Take a Look at What Uncle Sam Has Planned for North St. Louis,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 10, 2019.

5 According to US Census Data, the population of census tract 1271, which includes the future NGA site but sits just north of the Pruitt-Igoe site, dropped from a 1950 total population of 21,547 to 4,036 in 1990. Counting the adjacent Pruitt-Igoe site, now mostly vacant (but in the process of being developed by none other than Paul McKee), would increase the total population loss even further.

6 Mindy Fullilove, Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It (New York: Random House, 2004).

7 N. Szibbo, “Lessons for LEED for Neighborhood Development, Social Equity, and Affordable Housing,” Journal of the American Planning Association 82:1 (2016): 37–49.

8 US Green Building Council (2018c), USGBC History, retrieved February 22, 2018.

9 J. Wangel, M. Wallhagen, T. Malmqvist, and G. Finnveden, “Certification Systems for Sustainable Neighbourhoods: What Do They Really Certify?” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 56 (Supplement C) (2016): 200–13.

10 P. M. Weaver and A. Jordan, “What Roles Are There for Sustainability Assessment in the Policy Process?,” International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development (May 2008): 9–32.

11 M. Purcell, “Urban Democracy and the Local Trap,” Urban Studies 43:11 (2006): 1921– 41.

12 “Record of Decision: National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Chooses City of St. Louis Site to Construct $1.75 Billion Facility,” Stlouis-Mo.gov, June 2, 2016, https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/mayor/news/record-of-decision-nga-chooses-stlouis-to-construct-facility.cfm.

13 “National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Declares City of St. Louis Preferred Site for New $1.75 Billion Facility,” Stlouis-Mo.gov, March 31, 2016, https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/mayor/news/nga-declares-city-of-st-louis-preferred-site-for-new-1-75-billion-facility.cfm.

14 Though the St. Louis Development Corporation (SLDC) established Project Connect as a neighborhood engagement initiative “to understand the potential benefits and impacts the relocation of the NGA will have on surrounding neighborhoods and future development” soon after the site selection, the site boundaries, clearance area, and separation requirements had long been set. Though residents of the five surrounding neighborhoods are currently engaged through Project Connect in the development of new neighborhood plans, the oversized, securitized hole between them all is hardly a good social or spatial neighbor. Additional requirements for the NGA relocation, such as limitations on certain nearby uses due to terrorism concerns for federal agencies, have also impacted the art practices of nearby neighbors.

15 Eric Zencey, “G.D.P.R.I.P.,” New York Times, Aug. 9, 2009.

16 “Equity Indicators,” Stlouis-Mo.gov., accessed November 7, 2022, https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/data/dashboards/equity/.

17 “Strategy | National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency,” accessed November 5, 2022, www.nga.mil, https://www.nga.mil/about/strategy.html.

18 Exodus: Tale of Two Cities, directed by Jun Bae, independently produced documentary film, 2016.

19 D. S. Massey and N. Denton, American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

20 S. R. González, A Loukaitou-Sideris, and K Chapple, “Transit Neighborhoods, Commercial Gentrification, and Traffic Crashes: Exploring the Linkages in Los Angeles and the Bay Area,” Journal of Transport Geography 77 (2019): 79–89.

21 Benjamin Preis et al., “Mapping Gentrification and Displacement Pressure: An Exploration of Four Distinct Methodologies,” Urban Studies (February 2020): 1–20

22 Mindy Fullilove, Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It (New York: Random House, 2004).

23 D. J. Hammel and E. K. Wyly, “A Model for Identifying Gentrified Areas with Census Data,” Urban Geography 17:3 (1996): 248–68; J. Hwang and R. J. Sampson, “Divergent Pathways of Gentrification: Racial Inequality and the Social Order of Renewal in Chicago Neighborhoods,” American Sociological Review 79:4 (2014): 726–51.

24 Fullilove describing what the Black community lost during ‘urban’ renewal.

25 A. Dale and L. Newman, “Sustainable Development for Some: Green Urban Development and Affordability,” Local Environment 14:7 (2009): 669–81.

26 Fullilove, Root Shock.

27 Eric Klinenberg, Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life (New York: Crown Publishing, 2018).

28 Fullilove, Root Shock.

29 Fullilove, Root Shock.

30 Jacob Barker, “Developer Paul McKee Inflated Property Values to Secure Tax Credits, St. Louis Officials Allege,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 9, 2018.

31 Residents Say NGA is Not Welcome in St Louis Place.

32 Maria Altman, “NGA Site Property Owners Learn How Much They’ll Get From the City With Eminent Domain Report,” St. Louis Public Radio, May 9, 2016.

33 Maria Altman, “Missouri Tax Credits Helped McKee Buy Land; Now the City of St. Louis Wants to Buy It,” St. Louis Public Radio, June 16, 2015.

34 In addition to the payouts that went to nonresidents, one elderly, long-term neighborhood resident received disproportional support as the city elected to move her home to a nearby neighborhood. Perhaps capitalizing on a moment of publicity, this relocation cost half a million dollars.

35 Chris Naffziger, “How the City’s Pursuit of NGA Has Affected St. Louis Place Residents,” St. Louis Magazine, March 1, 2017.

36 Nicholas J. C. Pistor, “National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Will Stay in St. Louis,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 3, 2016.

37 Investigative journalists continue to update figures as new shell companies and lawsuits are exposed.

38 Jacob Barker, “St. Louis Deals with Aftermath of Failed Developer’s Plan,” AP News, March 29, 2019.

39 Karen Robinson-Jacobs, “Millions of Dollars Are Set to Pour into St. Louis’ North Side,” St. Louis American, August 12, 2022.

40 Steph Kukuljan, “Paul McKee’s Northside Regeneration Settles With State,” St. Louis Business Journal, June 5, 2019.

41 Finalist teams for the Brickline Greenway include: 1) James Corner Field Operations in association with [dtls], WSP, HR & A Advisors, Lord Cultural Resources, Sherwood Design Engineers, MIC, L’Observatorie, ETM Associates; 2) STOSS Landscape Urbanism in association with Amanda Williams, Urban Planning and Design for the American City, Alta Planning + Design, Marlon Blackwell Architects, HR & A Advisors and David Mason and Associates; 3) TLS Landscape Architecture, OBJECT TERRITORIES, [dhd] derek hoeferlin design in association with Langan, Linda C. Samuels, Paola Aguirre Serrano, EDSI, Ramboll, Kristin Fleischmann Brewer, eDesign Dynamics, Silman, Econsult Solutions, Bryan Cave, Preservation Research Office; and 4) W Architecture & Landscape Architecture in association with Arup, ABNA Engineering, Gardiner & Theobald, Kiku Obata & Co., Regina Myer

42 The collaborators on the winning team include: Stoss, urbanAC, Lamar Johnson Collaborative, ALTA, Marlon Blackwell Architects, Damon Davis / Heart Ache + Paint, De Nichols / Civic Creatives, Mallory Nezam / Joy + Justice LLC, MDavid Mason and Associates, HR&A, Lochmueller, DJM Ecological, Tillett Lighting Design, Bruce Mau Design.

43 Patrice Worthy, “St Louis City SC Looks to MLS Future by Remembering ‘Hard Truths of the Past,’” The Guardian, March 16, 2022.

44 See Samuels’ article “A Case for Infrastructural Opportunism,” Technology|Architecture + Design 3:1, 16–22, or the previously referenced Infrastructural Optimism (Routledge, 2021) for more on the ideas of infrastructural opportunism as a strategy to leverage large-scale infrastructure investment for greater social and environmental gains.

45 Mobility For All by All was coinvestigated with Penina Acayo Laker and Matt Bernstine, and was funded in part by a Divided City grant from the Mellon Foundation.

46 The next generations infrastructure criteria were derived from Samuels’ time at UCLA’s cityLAB codeveloping the WPA 2.0: Working Public Architecture competition and additional research and teaching that followed. The criteria, along with expansive case studies, strategies for implementation, and development of the infrastructural urbanism discourse, can be found in her book, Infrastructural Optimism. In short, next gen infrastructure is: Multifunctional; Public; Visible; Socially Productive; Locally Specific, Flexible, and Adaptable; Sensitive to the Eco-Economy; Driven by Design; Symbiotic; Technologically Smart; Developed Collaboratively Across Disciplines and Agencies; Operational at Both Micro and Macro Scales Simultaneously. The twelfth criterion, Reparative, was added in 2020.

47 Linda C. Samuels, Infrastructural Optimism(New York: Routledge, 2021).

48 Ibid.

49 Ecological Repair produced by Dylan Sabisch, Kia Saint-Louis, and Tiffany Dockins explores a “for us by us” regenerative model to repair social and historical erasure with ecological interventions in North St. Louis.

50 Ange-Marie Hancock Alfaro, interview with Bureau of Engineering Los Angeles, Infrastructure Equity Pilot Project, Zoom meeting, Los Angeles, February 2, 2022.

51 The + StL: Growing an Urban Mosaic team members include: coleads TLS Landscape Architecture, OBJECT TERRITORIES, [dhd] derek hoeferlin design in association with Langan, Linda C. Samuels, Paola Aguirre Serrano, EDSI, Ramboll, Kristin Fleischmann Brewer, eDesign Dynamics, Silman, Econsult Solutions, Bryan Cave, and Preservation Research Office.