Abstract

Infidel to academic disciplinarity, and employing a poetic, feminist reading of two vignettes and a case study, this paper presents “embodied infrastructures” as a fundamental grammar of prefigurative politics through which a redirected society rehearses an “otherwise” political future. Embodied infrastructures are identified in the people’s mic of the Occupy movement (2011), and the human chain and “home thrown in the mud” in the women’s antinuclear protest practices at the Greenham Common Peace Camp (1982-early 2000s). Acknowledging the interdependence of bodies, materiality, and democracy, and rejecting delegating their beliefs, morality, and intentionality to technologies, participants in prefigurative political movements are determined to become infrastructure themselves. Infrastructures of embodied resource circulation are seen in continuity with “corporeal infrastructures” found in communities of scarcity during which bodies are activated as social actants—evident in Chandigarh’s appropriation of autochthonous capacities of auto-construction, and a cautionary tale of the inherent vulnerability of bodily employment when co-opted by conditions of alienated social relations. Embodied infrastructures are radical in their transgression of the boundaries between collectivity and individuality, users and designers, labor and work, privacy and publicity, futures and presents. They bring “life making” and “thing making” together as entangled, mutually constitutive paths to collective emancipation.

Vignette 1: The People’s Mic

Human Machine

When I began repeating your words, little made sense,

a foreign language.

But as my voice was lifted by your myriad lips

and I breathed your words,

all I wanted was to scream you.

All I was were lungs.

All we were was a flawed machine rebooting itself, resurrecting.

Consider the following acoustic image: on October 23, 2011, at Occupy Washington Square Park—several blocks away from Zuccotti Park, where the Occupy movement beganFootnote1—a teach-in event featured Judith Butler as a guest. Her words reverberated through the crowd, suffusing, and then emanating from the bodies assembled in the square:

“I am Judith Butler… It matters that as bodies we arrive together in public, that we are assembling in public.… As bodies we suffer. We require food and shelter. And as bodies we require one another, independency, and desire. So this is a politics of the public body, the requirements of the body, its movement, and its voice.” Footnote2

Butler’s words were repeated by the participants, who in effect, became the people’s microphone. Every participant was Judith Butler; they were “the public body,” and the work they did was the “politics of the public body.”

The “people’s mic” (or as some call it, “the human mic”) was first enacted by the antinuclear movements of the 1980s but reemerged in the Occupy movement and soon became part of the “movement culture and a signifier of the participatory nature of the Assemblies.” Footnote3 Because of a spatialized struggle over noise control and forced silence,Footnote4 occupiers of Zuccotti Park used the “human mic to collectively oppose the aural violence of the state.” Footnote5 With the people’s mic, they reclaimed their function as a public body through a collective action of free speech. To participant Sheila Nichols, the people’s mic embodies the leaderless ethos of the movement: “[The] people’s mic forces people to be participatory, to listen, to understand that we’re in it together,” she explains, adding that “it’s an active experience that forces [individual] people to be a part of something that’s a whole.” Footnote6

Media theorist Marco Deseriis calls the people’s mic a “collective amplification of individual voices in public gatherings”—a way to “occupy simultaneously two positions, that of medium… and that of addressee.” Footnote7 As a repertoire of contention, its utility arises in various circumstances: from disrupting events and “contest[ing] the authorities” to enabling communication among demonstrators to “amplify[ing] speakers in a public meeting.” Footnote8 Analogies with the chorus in an ancient Greek tragedy abound: the people’s mic encircles and protects the speaker and, importantly, their right of speech. For Deseriis, this comes with a certain “de-subjectivation”: participants may feel uneasy when repeating words they disagree with, yet do so while understanding that “amplification [is] not endorsement” but rather an expression of a fundamental principle: “allowing all voices to be heard.” Footnote9 From a design perspective, the people’s mic is a spatial, socioaesthetic means of communication and amplification utilized in large open public spaces that, by choice, does not rely on conventional technology. Based on people’s voices and volition, this low-fidelity medium is as low-tech as it can get—an exemplary embodied infrastructure that distributes resources in an inherently collective, participatory manner. It operates without coercion or force, an animate ontology doing the work we normally delegate to the realm of the inanimate or the technical. The people’s mic does not endeavor to be technically efficient as a machine would, and indeed is prone to flaws, almost as a collective game of telephone. Relying fully on human bodies that stand in union, it is a communication infrastructure that generates community empowerment and incorporates checks and balances—an apparatus of vigilance that vibrates through bodies, with multiple mouths, lungs, and ears as its organs of operation. The people’s mic serves not simply to amplify sound, but to reiterate that fundamental belief in the right to be heard. It is a conduit that circulates this fundamental communal resource. It is part of the four infrastructures enacted in the protest camp—domestic, action, communication, and governance—which, according to the seminal study by Fabian Frenzel, Anna Feigenbaum, and Patrick McCurdy, are grounded on the conceptual clusters of spatiality, affect and autonomy.Footnote10

Prefigurative Politics and Design

Design has been indispensable to the colonial matrix of power, yet the act of designing is not inherently the “master’s tool.” Footnote11 Design can be an agentic constituent in processes of political emancipation, in tandem with antioppressive pedagogies such as those introduced by the 1930s traditions of workers’ education in the Caribbean, the United States, and Nordic countries, and in the 1960s in Latin America by Paulo Freire and Orlando Fals Borda. Within the embodied infrastructures of prefigurative movements, design can serve as a transformative mode of resistance that somatically rehearses a redirected material practice. Occupy Wall Street at Zuccotti Park was one well-known iteration of prefigurative political action: a protest camp based on principles of participatory democracy, modeled both performatively and materially to analogize the future society the movement envisioned and fought for. Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, an earlier prefigurative action that took place in the United Kingdom from the 1980s to the early 2000s, was another.

My interest in contemplating these examples of prefigurative politics is motivated by my understanding that the work of these movements is, at its core, designerly, despite its infidelity to the traditional tenets of professional design. While most acts of political disagreement oscillate between “speaking truth to power” and using violence to express rage, prefigurative politics are a repertoire of sociotechnical action that expresses dissent through radical engagement with materiality, presenting a distinct modality of contention: dissenting through making. Indeed, the term “prefiguration,” with origins in the Latin prae (“before”) and fingere (“to mold, shape”), which is related to the Latin figurare (“to represent, depict”), carries affinities with actions of molding and shaping—evidence of its relationship with materiality.Footnote12

The “making” that emerges within prefiguration is not simply a vehicle for achieving a desired political future, but rather a current embodiment of that future—an experience of change in the present. For social theorist and political activist Carl Boggs, prefigurative politics are “those forms of social relations, decision-making, culture, and human experience that are the ultimate goal” of a certain movement.Footnote13 For sociologist and gender scholar Wini Breines, prefigurative politics build a “new society within the shell of the old,” Footnote14 and offer living examples of alternative social formations that have “embraced the ‘concept of community’”Footnote15 and that “embody the desired society” of the future. Since at least the 1960s, participants in left-leaning prefigurative political movements and eventsFootnote16 have challenged states of domination by exercising principles of self-governance, decision-making, and collective action. By striving to establish unconventional relations and exchanges through the process of creating material assemblages, they embody futurity while practicing an “otherwise” scenario.

The radical material practitioner employs an ethos of self-determination and an emancipatory and empowering capacity for prefigurative forms of resistance—characteristics emphasized by economic and political sociologist Lara Monticelli.Footnote17 Collectives of nonexpert design actors, collaborating with (but often in the absence of) professional designers, acquire the agency necessary to craft sociomaterial alternatives. Committed to politics of emancipation, and often members of disenfranchised communities, these activists enact alternative ways of being, knowing, and doing. Their spatial and material practices concur with their epistemic and ontological reorientation, as evident in their rejection of expert knowledge or their multispecies commitments.Footnote18 For these reasons, prefigurative politics are significant for studies of space and materiality. They demonstrate actionable, impactful efforts that defy the entrenched dualities of mainstream material production (producer/user, expert/nonexpert, human/object), offering radical alternatives in both material practice and design knowledge. The infidelity and incompleteness of their design allow them to adapt to situated circumstances while remaining loyal to their utopian principles.

While designerly pursuit in no way guarantees a certain future, an expansive sense of design as redirected material engagement not only supports abolitionist visions but also is essential for their realization. Thus, in the embodied infrastructures of prefigurative movements, the emancipatory capacity of design differs from an understanding of design as inherently leading to positive change.Footnote19 It also opposes prominent interpretations of design as an act that exclusively adds to the exchange value of capitalist commodity, or as a sociotechnical application destined to follow or apply methods of technocracy and solutionism. Besides political commitment, prefigurative action also requires openness to a process of intersubjective transformation, which is enacted through a collective sociotechnical process where both human and nonhuman agencies coalesce.

Infrastructures

How can we understand the function of the people’s mic as an infrastructure that lacks the roughness of wires, pipes, and other familiar, heavyweight textures? Like “design,” “infrastructure” is an elastic word. For Brian Larkin, infrastructures are both “things and also the relation between things,” Footnote20 putting various resources—materials, capital, information—into circulation, which makes them “relatable.” Footnote21 These common goods, however, circulate upon uneven terrain; infrastructures not only connect but also divide, segment, and dispossess. They are susceptible to flaws, and for Susan Leigh Star and Karen Ruhleder “the normally invisible quality of working infrastructure becomes visible when it breaks.” Footnote22 Interruption and breakdown reveal the complexity of a system, from imperfect planning and implementation to missing or ad hoc acts of maintenance and repair.

The role of design in the process of infrastructuring—as a material, everyday engagement that includes consumption, contestation, and appropriation of resources, and as a sociotechnical action performed by both expert and nonexpert actants at various stages of the infrastructure’s life cycle—is indispensable. Multiple acts of designing configure an infrastructure, and plural types of material engagement shape its distribution, use, appropriation, or substitution, leading to new, unforeseen, and unscripted entanglements.

At the fringes and the antipode of capitalist infrastructure, the landscape of prefigurative spaces evokes what Fran Tonkiss calls a “shared infrastructural poverty,” Footnote23 which goes beyond a mere visual affinity with camps for the displaced, or “nomadlands.” The makeshift spatial structures and bricolage approaches to making in camps like those of the Occupy movement share similarities with spaces of informal urbanization, survival societies under austerity regimes, and communities facing systemic resource dispossession. This is more evident in prefigurative spaces that have endured through time. Such spaces sprout from auto-construction (as also found in slums or favelas) and often endure long processes of legalization.Footnote24

Inspired by AbdouMaliq Simone’s “people as infrastructures” Footnote25 concept, which “makes the leap from the infrastructures of steel and concrete to those of flesh and blood,” Footnote26 Tonkiss describes human bodies as

“the basic carrying element of these auto-infrastructures… ramified around the ordinary labour of talking, listening, carting, pulling, sorting, carrying and waiting… In the context of state and market failures… human bodies themselves become conduits of exchange and connection.” Footnote27

Living in the backstage of infrastructure, these individuals carry the double burden of “filling in the cracks… and becoming the infrastructure of their [own] lives.” Footnote28

The notion of embodied infrastructure has been employed in a somewhat different yet relevant formulation by feminist theorists such as Suzanne Clisby and Julia Holdsworth who consider it a “gendered construct” given the role of women’s bodies in “making social life and culture possible.” Footnote29 Yoana Fernanda Nieto-Valdivieso also uses the term “embodied infrastructure” to describe women’s work in conditions of conflict, particularly

“the activities, practices and roles played by women.. [which] are intertwined with the doings of everyday peace that enable people to ‘navigate life.’ Footnote30… They are grounded in the mundane tasks performed by women to make life livable amid violence (economic, symbolic, visceral)”

…

“Understanding women as embodied infrastructures makes visible how they use their own skills, roles, and capabilities, to mend their lives and communities.” Footnote31

Vignette 2: Built by Hand, Carried on Heads

“The city in Chandigarh was built by hand and carried on the heads of women.” Footnote32

In studying the collective body becoming a conduit of resource circulation, I suggest a continuum between “corporeal infrastructures” and “embodied infrastructures,” the first activating what Donna Haraway saw as the body’s social actant function versus as a vehicle of social agency, in the second.Footnote33 Cultural sociologists Chris Gilleage and Paul Higgs interpret Haraway’s view: the former refers to “the relatively unmediated materiality of the body and its material actions and reactions that are socially realized without recourse to concepts of agency or ‘intent;’” the latter refers to the body’s “materiality as an inseparable element in the realisation of personal and social identity.” Footnote34

Construction of the new northern Indian city of Chandigarh (designed by Swiss-French modernist architect Le Corbusier, after the official fall of colonialismFootnote35) showcases the collective body as a remarkably calibrated machine and “social actant”—it also serves as a cautionary tale of the inherent vulnerabilities of corporeal infrastructures.

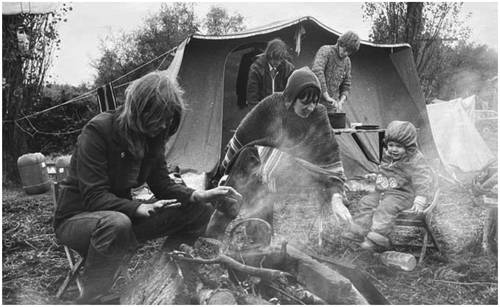

In the 1966 film Une Ville à Chandigarh,Footnote36 Alain Tanner’s cinematic lens bears witness to Chandigarh’s women builders, who perform a miraculous operation. Walking slowly and straight through a field, they carry straw baskets (typically used as fruit bowls) atop their heads (). Each inverted “hat,” affixed to a device on the woman’s head, contains earth and concrete. With extraordinary capacity and limited choices, the women deliver their goods, still wet and muddy, from head-to-head during this brief, perpetual, and carefully choreographed exchange. When the last link in the human chain reaches the edifice—a testament to a proclaimed postcolonial emancipation—a human ladder awaits: men on scaffolding, who pass the bricks from hand to hand all the way to the top.

Figure 2. Embrace the Base, women’s peace protests, RAF Greenham Common air base, December 12, 1982. Courtesy PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo.

This remarkable assemblage reveals the collective capacity of corporeal infrastructures—bodies and their coverings (saris for women, lungis for men), hands and heads, bowls and building materials, a scaffolding and a rising structure. Communities around the world have developed this capacity historically as a means of self-sufficiency—especially valuable in conditions of adversity—and it continues in many building practices to this day. More than just organizational structures of bodily ability, corporeal and embodied infrastructures comprise humans serving as engines of material making and frugal resource circulation.

Yet the enormous strength of corporeal infrastructures was not adopted for auto-construction at Chandigarh, but exploited for a project extraneous to the community’s needs or desires—as part of an extractivist network consisting of “concrete, abundant unskilled labour, [and a] lack of productive capital.” Footnote37 As Stanislaus von Moos and Russell Walden point out, “for some, Chandigarh means progressive, socialist planning, crowned by outstanding architectural achievement; for others, it is a symbol for the arrogance of Western planning ideology inflicted upon the Third World.” Footnote38 Beyond the decolonizing premise of this architecture, in agreement with Sanoja Bhaumik, I find a “deeper contradiction” in the recent Museum of Modern Art exhibition that presented Tanner’s film, particularly

“in the reliance of this ‘cultural emancipation’ on a more acute form of subjugation—a low-paid, often caste-oppressed labor force employed to construct temples to modernism and liberation.” Footnote39

It’s no surprise then—as Bhaumik points out—that this economy of construction embedded and reasserted internal hierarchies in newly independent, postcolonial states. While there is a big difference in political positions between these two cases—mic check performed in protest, and Chandigarh “carried on the heads of women” coercively, and with no other choice available—it is the capacity of the collective body to become a conduit of resource circulation, evident in both cases, that interests me.

Beyond the grand narratives of nation-building and the colonial exploitation of innate local practices, embodied infrastructures—despite the risks and vulnerabilities they share with corporeal infrastructures—display the truly audacious potential of the collective body. Notwithstanding their other similarities with corporeal infrastructures of auto-construction (as seen in various urbanization sites or premodern communities), these practices of self-determination and self-management do not arise strictly from emergency conditions or resource scarcity. They are more intentional, less teleological, aiming toward social (re)production outcomes rather than technical assemblages. They emerge through a perspective of futurity and introduce “otherwise” actions, disrupting the political and economic context. If corporeal infrastructures are a capacity, embodied infrastructures are a capability and a performance.

Material resources such as speakers, fences, machines that transport building materials—whether scarce or not—might be available as a state provision or market commodity, and might even be affordable to practitioners of prefiguration. Instead, the greatest value to proliferate throughout the choice of embodied infrastructures is communal power and horizontality, which can make them intoxicating and cathartic. Yet when the intentional community enters the realm of the everyday, scaled up to daily performance and maintenance as an alternative to the market system or state capitalism, the embodiment of infrastructure may become taxing for both the communal and the individual body.Footnote40

Case Study: The Human Chain

Women’s Fence

When I held your hands tightly, embracing the base,

your rings were engrossed in my fingers like links of endearment.

They made me forget the home that was thrown in the mud,

the teapots in the stroller ready for evacuation,

the sleepless, rainy nights in the camp.

As our thousand hands linked, embracing the base,

a social sculpture awakening,

a somatic monument becoming alive,

fences of all things nuclear fell

like a house of cards.

Only children’s canopies survived,

and under them we dream,

breathing the woodsmoke of our freedom.

Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp

The Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, a women’s movement that began in the early 1980s, soon became an important political constituent of antinuclear mobilization. The human chain in particular, a chain created by 30,000 women holding hands around the nine-mile fence surrounding the US cruise missile base in Berkshire, England, on December 12, 1982, was a paradigmatic, embodied infrastructure that incarnated this prefigurative political community—an “inventive, leaderless, constantly rotating population of women [who] blocked the smooth functioning of this cruise missile base for several years.” Footnote41 The day after the first Embrace the Base demonstration on December 12, 1982, some 2,000 women blockaded the entrances; at dawn on New Year’s Day, forty-four of them scaled the fence and danced on the missile silos.Footnote42 Similar actions reached a climax on April 1, 1983, when about 70,000 protesters formed a 23-kilometer human chain through the so-called Nuclear Valley, linking Greenham to Aldermaston to the Burghfield ordnance factory. Rebecca Mordan, who participated as a five-year-old with her mother, later recalled it as “just an incredibly powerful and uplifting experience. Becoming this human fence, encircling all this harsh military stuff on the inside and seeing all the police patrolling on the outside.” Footnote43

Space/Counterspace: A Tale of Two Fences

Note the rival human intentions of the two different fences: One was made by women’s own bodies, a human chain—think of the gentle, joyful circle of a necklace—as the collective body was tiptoeing on the double bind of womanhood.Footnote44 The other was “very serious,” made of “thick wire mesh topped by several feet of rolled barbed wire, all supported at frequent intervals by cement pylons,” as Ann Snitow put it.Footnote45 This double-reinforced fence functioned as a form of surrogate institutional authority (in this case, of the US military), prohibiting unauthorized human bodies in an act of bordering: delineating spatial differences in terms of sovereignty, ownership status, or spatial rights. Not simply defensive, its imposing character—designed to inflict injury and pain—disempowered and intimidated.

Like every border, however, the military enclosure created a dialectic: space and counterspace. It transformed space into a magnetic field that both attracts and repels, evoking both disavowal of and desire for transgression.Footnote46 The women’s chain, meanwhile, undermined its utility but also performed acts of affection, spending hours singing and taking care of the fence, embellishing it with colorful ribbons, garlands, balloons and children’s stuffed animals ( and ). For many women, it was a peaceful, unforgettable experienceFootnote47—a living, breathing social sculpture at the antipode of the barbed-wired fence, relying not on objects and technologies of surveillance, but simply on bodies determined to hug instead of repel.

Figure 3. Embrace the Base, RAF Greenham Common air base, December 12, 1982. Photograph from Bridget Boudewijn’s Archive, Greenham Women Everywhere, https://greenhamwomeneverywhere.co.uk/portfolio-items/bridget-boudewijns-archive/. Creative Commons.

How shall we interpret the human chain in relation to design? From a conventional viewpoint of design, the refusal to rely on things (fences, chains, and other bordering or building devices), this formation was firmly anti-design. But a broader definition accepts the action of the women’s chain as an enhanced or expanded form of design, a material engagement fueled by somatic power—not least in the songs of the Greenham women, whose inner somatic power (as described by Mordan) is reminiscent of the people’s mic:

“It’s a way of pulling on your inner reserves—using your core muscles. And women can make all kinds of sounds.… The Greenham women actually made some very disturbing noises to express their fear and their anxiety and their rage. And… it absolutely unified them.” Footnote48

In the embodied infrastructures of Greenham Common, the human chain, and the surrounding peace camp which persisted until the early 2000s, women used this capability to resist a technological regime of nuclear missiles and barbed-wire fences and manifest an alternative vision for the future. By holding hands and forming a human chain, they rejected delegating their beliefs, morality, and intentionality to things or technologies, and determined instead to become infrastructure themselves. Linked together, these women showed a readiness to prefigure worldmaking of a different type, with a protest based on economy of resources, self-imposed limitations, and inherent skepticism of machines. Their consciousness was especially pertinent at that historical moment of realization that all interlinked sociopolitical infrastructures—familial, national, and international—had failed them. Most importantly, the women’s multi-year presence outside the base played a pivotal role in the decision to withdraw the American missiles in 1991.

Everyday Commoning: A Home Thrown in the Mud

When scaled up and multiplied in the everyday (with various collective practices of maintenance, for example), the bodily infrastructuring of the Greenham Common women was no less labor intensive than the typical work of social reproduction—“the activities and institutions that are required for making life, maintaining life, and generationally replacing life,” as defined by Marxist feminist Tithi Bhattacharya, who developed the Social Reproduction Theory (SRT).Footnote49 Films documenting experiences from the camp,Footnote50 unlike the photogenic imagery of the fence actions, are replete with the exhaustion characteristic of women’s lives across histories and borders. These taxing conditions included battles with police, constant camp evictions, and weather-related adversity such as the wet, cold, muddy conditions that camp visitor Anna Faulkner describes: “It was miserable.… Look at their boots; you can see by the coats. I remember it raining, raining, and raining. It was soggy grass… slippery, sliding.” Footnote51Several participants talk about illness that hit after the “massive output of… emotional, mental, spiritual energy” that was poured into the protest.Footnote52 Snitow described the Greenham Common camp as a home thrown in the mud—at once vexing and liberating, “a thrilling visual landscape” Footnote53 of domestic practices out in the wild:

“Familiar domestic collages of blackened tea kettles, candles, corn flakes, bent spoons, chipped plates… lie around as if the contents of a house had been emptied into the mud, but here the house itself is gone. The women have left privacy and home, and now whatever acts of housekeeping they perform are in the most public of spaces.” Footnote54

In this newly domesticated landscape, the walls of the nuclear family had fallen to reveal both disaster and promise ( and ). This act of exposing the private world of tedious chores and strenuous daily practices was both forced and by choice. All the muddy messiness became visible, accentuated by intention. In these fragile homes supported by embodied infrastructures, we can sense a cacophony as in Moten and Harney’s undercommons. And this reminds us that “our desire for harmony is arbitrary, and in another world, harmony would sound incomprehensible. Listening to cacophony… tells us that there is a wild beyond to the structures we inhabit and that inhabit us.” Footnote55 The collective body acted not in compensation for missing things, but as an inherent force of abolition, recalling Simone’s observation of “people as infrastructures.” From a global perspective, 1980s England was an environment of relative abundance, but Greenham Common women of many class backgrounds cast off both the comforts and the imprisonment of home.

Figure 5. Greenham Common Camp. Photograph from Sandie Hicks’ Archive, Greenham Women Everywhere, https://greenhamwomeneverywhere.co.uk/portfolio-items/sandie-hicks-archive-2/. Creative Commons.

Figure 6. Greenham Common Camp. Photograph from Maggie Sully’s Archive, Greenham Women Everywhere, https://greenhamwomeneverywhere.co.uk/portfolio-items/maggie-sullys-archive/. Creative Commons.

In this prefigurative context, Greenham Common was a reproductive commons, experienced as collective social reproduction in an unwalled environment, independent from notions of waged labor or traditional domestic roles.Footnote56 Reproduction here was diametrically opposed to its value and validation within the capitalist framework, where domestic labor is typically undertaken by underpaid caretakers (such as nurses, teachers, and cleaners) and by women at home. The pursuits of the Greenham Common women were incompatible with life in the world of capitalism and patriarchy. Yet a cross-fertilization between the camp and everyday domestic life was possible—in particular, the edification of women who lived there or visited, and then found their lives transformed also outside of the camp. Faulkner spoke of her admiration for these women—both those who were willing to go to prison and those who came to support them—and of returning home with a “strong sense of sisterhood”:

“I’m not saying everybody had terrible problems. But you left whatever it was behind. What was going on at home didn’t matter. It gave a great deal of strength, and then you passed it on to other people at work…. I took away a great feeling that if you come together with people, with women or with men, they can do such brave things…. This was such a sharing, such a unifying thing. I wish I could have done more. But… everybody who came… contributed in some small way.” Footnote57

This experience shed new light on the daily tasks of social reproduction—underscoring childbearing, friendship, and camaraderie—so that even brief visitors to the camp felt in their bones a sense of belonging and connection. Women who experienced Greenham Common comprehended that liberation is never personal but always tied to a collective, and that gender and class oppression were coconstituted. “This was first time that I’d actually understood what feminism was really about,” said participant Lyn Barlow. “And how the personal is political, and joining up the dots between things that happened to me in my childhood, and poverty, and working-class roots, unemployment—it all made more sense once I’d become involved with Greenham.” Footnote58

Incommensurable Connections

Rearguard acts performed by bodies rather than technologies, such as the human chain, the home thrown in the mud, and the people’s mic approach materiality in a similar manner to acts encountered in sites of scarcity and survival, such as Chandigarh, which despite its modernist glorification had to contend with the material conditions of the place. We must not ignore the incongruity between these predominantly white women chanting and even enjoying themselves in front of a military fence and those silent, brown-bodied silent women transporting heavy building material atop their heads. Without a doubt, their struggles are incommensurate; the corporeal infrastructures observed in Chandigarh did not function as a vehicle of emancipation. Yet the bodies of women in both groups have been sites of domination inflicted by the compounded forces of colonial power, social inequality, Victorian morality, and patriarchal oppression. Despite experiencing different types and degrees of subjugation, both the need and the capability for liberation unite them.

These two realms—one of poverty attributed to extractive colonialism, and the other of intentional adversity by rebelling citizens in the heart of the colonizing power—might not be viewed in isolation. Maria Mies, for example, exposes the “underground connections” between European “housewifization,” natural exploitation, and the subordination of women in the colonies.Footnote59 Both protest camps and sites of survival have potent political power. As Michele Lancione claims, “[U]ncanny places, uninhabitable ‘homes’ and marginal propositions” challenge structures of domination by affirming a “different way of being in the world,” which makes them sites of radical political action rather than survival.Footnote60 Rather than exclude the study of political action from a scholarly rubric of “empowerment and capabilities” Footnote61 or in other words, agency from structure, in my perspective, bodily and material capacity, capability, and agency are inextricably linked with political action. To use the words of Jane Bennett, agency here is seen as “distributive,” or dependent on “a swarm of vitalities at play.” Footnote62

A Revised Perspective on Labor, Work, and Action

A helpful starting point for comprehending the subversive dimension of the commoning work at the Greenham women’s camp lies in Hannah Arendt’s distinction between unproductive (or reproductive) labor, which produces life; productive work, which produces durable artifacts; and action, which is the ultimate goal of political public life and is based on speech and contemplation. This understanding follows the Aristotelian analysis of acts whose ends lie within the activity, such as fishing or farming, versus in the products they yield, such as crafts or works of art (poiesis)—namely, that work should be conducted “for the sake of” meaningful values rather than functionality alone, while labor is executed simply “in order to” fulfill certain goals of utility, such as those of reproductive labor (nursing, eating, surviving). In this idealistic view, action surpasses both labor and work, engaged as it is with public affairs and with freedom, plurality, and solidarity.Footnote63

The type of work we encounter in embodied infrastructures defies these hierarchical distinctions. On the one hand, embodied infrastructures reflect bodily labor that does not create a lasting thing, but instead fabricates immaterial or immediately consumable artifacts (circulation of resources, voice amplification, human fencing) that are neither reproductive nor durable. And unlike in conventional fabrication, bodies must be present during both resource production and circulation. On the other hand, embodied infrastructures produce a deeply reproductive activity: relationality and affective infrastructuring among human subjects. Directly connected with speech exchange and political action (see ), this type of labor is executed not simply “in order to” produce a consumable good (an infrastructure that provides a resource) but rather “for the sake of” fundamental political values. Experienced as reproductive labor, work and action simultaneously, embodied infrastructures actualize the human capacity for freedom.

Figure 7. A picket mounted on the missile silo construction road by the Women’s Peace Camp at RAF/USAF Greenham Common, Berkshire, February 1982. Photograph by Edward Barber. Courtesy Edward Barber Archive.

By centering domesticity that breaks out of the private realm, introducing a “beyond,” Greenham Common incarnated Arendt’s fear of takeover by the social—the modern shift of the private realm “from the shadowy interior of the household into the light of the public sphere.” Footnote64 Rather than protecting the political sphere from domestic affairs, Greenham Common’s embodied infrastructures herald a society that does not distinguish between the two, where the public world not only protects social reproduction but also frames it as political action, of no less value than speech or artwork. By foregrounding the work of social reproduction, therefore, embodied infrastructures refuse its capitalist association with “invisible” domestic labor and institutional care, and demand that reproductive work be recognized and reevaluated. This feminist perspective rejects the creation of a human labor force as the the goal of social reproduction work, aiming instead not to produce workers who feed the capitalist system, but rather liberated subjects who oppose it.

Bhattacharya goes on to highlight the opposing processes of “life making” (reproductive work) and “thing making” (profit-making).Footnote65 As an architecture and design studies scholar, however, I see the essential role of materiality—the thing-making processes performed during social reproduction—as indispensable to the life-making work. With a wariness of technology and of creating a society of laborers in which “the world of machines has become a substitute for the real world,” Footnote66 embodied infrastructures produce relations between bodies, and bodily resources as well as care-full things that defy statist and market provisions.

While SRT typically focuses on the home and institutions of care, Nancy Fraser integrates theories of subjectivation, habitus, culture, lifeworld, and “ethical life” with Marxism and socialist-feminism, giving a fuller account that also comprises sites such as “neighborhoods, civil society associations, and state agencies.” Footnote67 One such space is the protest camp, discussed here: a space that conflates workplace, home, and polis; the private, the public, and the commons; labor, work, and action. Upending Marx’s view of alienation in the productive sphere, wherein “the worker… is at home when he is not working, and when he is working he is not at home,” Footnote68 Greenham Common has been highlighted as a nonalienating reproductive space. The women were at home, but their home was a collective, unwalled political home, a home thrown in the mud, and yet fenced by a bodily embrace. What sustained this home was an integrative process of laboring, working, and acting—without distinguishing between the three, and refusing to separate them.

No longer unappreciated and “naturalized into nonexistence,” Footnote69 this entangled labor/work/action power is at the forefront of collective action in prefigurative political sites. This type of collective is based not on kin or abstracted institutional relations (as within the conventional capitalist framework), but on intentional communities of choice. The “things” produced here are not singular objects or commodities, but infrastructural relational systems that, despite their flaws, benefit the collective. As in other prefigurative communities, such infrastructural systems are safeguarded from becoming abstractions or succumbing to capitalistic labor division by being embodied as a form of communal knowledge—“products” that reverberate through the participants’ bodies.Footnote70

While skeptical of SRT’s separation between “making things” and “making life,” and its persistence on sites of care that operate in service to the capitalist framework, I find SRT’s illuminations of the implications of capitalism in every aspect of life particularly instructive. For Meg Luxton the “production of goods and services and the production of life are part of one integrated process,” Footnote71 because from a Marxist perspective, as Bhattacharya observes, “our performance of concrete labor, too, is saturated/overdetermined by alienated social relations within whose overall matrix such labor must exist.” Footnote72 For social movement practitioners, whose labor is doubled because of their performance both at sites of capitalism and anticapitalist struggle, this saturation and overdetermination often result in emotional exhaustion and burnout. Nevertheless, within prefigurative domains, capitalism relinquishes its absolute control and embodied infrastructures with their emphasis on social reproduction provide an affect for collective emancipation. When asked “what one memory or feeling arose when they thought of Greenham, “woodsmoke” was a frequent answer, reflecting the women’s sensory memories of camp. But to this question, a participant named Becky replied: “Freedom, I think.” Footnote73

Transgressive Gestures: A Grammar of Prefiguration

Gestures of embodied infrastructuring, such as the people’s mic and the women’s chain, offer a basic grammar of prefigurative practices, through which a redirected society rehearses an “otherwise” political future. Acknowledging the interdependence of bodies, materiality, and democracy, embodied infrastructures are radical in their transgression of the boundaries between collectivity and individuality, users and designers, labor and work, privacy and publicity, futures and presents. Likewise, applying two vignettes and a case study to my analytical and normative argument propelled me beyond an empirical focus on what is to a radical exploration of what could be realized—a horizon of possibility. Encouraged by evidence of my own imaginings (and infidel to academic disciplinarity), I sought—and found—evidence of imaginings of anticapitalist modes of production.Footnote74

Embodied infrastructures are both a prefiguration and a reconfiguration of the world—pedagogies of collective ways of being, inscribed in bodies and establishing a new transformative habitus. Participants in these collective vibrant materialitiesFootnote75 carry their pedagogical seeds in their daily lives, beyond specific sites of prefigurative protest. Given the intentional material frugality and the abolition of walls and privacy, building relationships between bodies is the clear choice for action. As with any bodily performance, embodied infrastructures are inherently imperfect, prone to leaks, and in a permanent state of fragility. They carry risks—both internal (burnout) and external (extractivist exploitation)—which might point to deeply rooted, systemic inequalities or power dynamics that are preexisting or reproduced in their domains of action.Footnote76 Yet embodied infrastructures also are innately reparable: leaks are soon sensed by the collective body, always ready to mend and restore. They serve as a mutual aid, which “involves a sense of being in struggle with: understanding one’s survival and liberation as being tied to others.’” Footnote77

Neither design solutions nor alternatives, embodied infrastructures are fundamental prefigurative movement practices, both ritualistic and pragmatic, that reveal a care-full approach to sociomaterial engagement. They bring “life making” and “thing making” together as entangled, mutually constitutive paths to collective emancipation.

Acknowledgements

I am immensely grateful to the Special Issue’s guest editors for their guidance and care. I am also indebted to my New School colleague and friend Victoria Hattam for our intellectual and pedagogical “accompaniments” in the last ten years. The paper is dedicated to those who made homes for and with me, and my lineage of women: Kleanthi, Despoina, Ioanna, Efterpi, Eytychia, Katerina, Despoina-Kleanthi, and Maya for the human chain that connects us from Kriti and Athens to New York. Αυτή η δημοσίευση είναι αφιερωμένη στην δικιά μας αλυσίδα, Κλεάνθη, Δέσποινα, Ιωάννα, Ευτέρπη, Ευτυχία, Κατερίνα, Δέσποινα-Κλεάνθη, Μάγια.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jilly Traganou

Jilly Traganou is professor of architecture and urbanism at Parsons School of Design, The New School, and coeditor-in-chief of the journal Design and Culture. She is currently working on the role of space and materiality in prefigurative political movements and is interested in multivocal scholarship that experiments with poetic, performative, and collective forms of knowledge production and presentation. She is author of Designing the Olympics: Representation, Participation, Contestation (2016) and The Tôkaidô Road: Traveling and Representation in Edo and Meiji Japan (2004), and editor of Design, Displacement, Migration: Spatial and Material Histories (2023) with Sarah Lichtman, Design and Political Dissent: Spaces, Objects, Materiality (2020), and Travel, Space, Architecture (2009) with Miodrag Mitrašinović.

Notes

1 The first Occupy protest camp arose at Zuccotti Park in the Financial District of New York and lasted from September 17 to November 15, 2011.

2 Luke Taylor, “Judith Butler at Occupy WSP,” October 23, 2011, YouTube video, 6:51, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rYfLZsb9by4.

3 Sasha Costanza-Chock, “Mic Check! Media Cultures and the Occupy Movement,” Social Movement Studies 11:3–4 (August 1, 2012): 375–85, https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2012.710746.

4 Richard Kim, “We Are All Human Microphones Now,” The Nation, October 3, 2011, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/we-are-all-human-microphones-now/.

5 Lilian Radovac, “Mic Check: Occupy Wall Street and the Space of Audition,” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 11:1 (January 2, 2014): 34–41, https://doi.org/10.1080/14791420.2013.829636.

6 Carrie Kahn, “Battle Cry: Occupy’s Messaging Tactics Catch On,” NPR Section National, December 6, 2011, https://www.npr.org/2011/12/06/142999617/battle-cry-occupys-messaging-tactics-catch-on.

7 Marco Deseriis, “The People’s Mic as a Medium in Its Own Right: A Pharmacological Reading,” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 11:1 (January 2, 2014): 42–51, https://doi.org/10.1080/14791420.2013.827349.

8 Deseriis, “The People’s Mic.”

9 Deseriis, “The People’s Mic.”

10 Fabian Frenzel, Anna Feigenbaum, and Patrick McCurdy, “Protest Camps: An Emerging Field of Social Movement Research,” The Sociological Review 62:3 (2013): 459, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12111.

11 Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007), 110–14.

12 Fingere (“to mold, shape”) derives from the Proto-Indo-European root dheýh/; see Andrew L. Sihler, New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin (London: Oxford University Press, 1995), 158. So *dʰ or *dʰeyǵʰ- regularly becomes Latin f; *ey becomes Latin i; and *ýʰ- becomes Latin h, meaning that the nasal n must have been inserted at some point to give us fingō and not unattested fiho. This gives fingō—or fig-, with the loss of -n-, and forms nominal stems including figura, figulus (“potter”), and figurare. Special thanks to linguist Lefteris Paparounas for this detailed explanation.

13 Carl Boggs, “Marxism, Prefigurative Communism, and the Problem of Workers Control,” Radical America 11:6 (1977): 100.

14 Wini Breines, Community and Organization in the New Left, 1962–1968: The Great Refusal (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1981), 52. While Breines examined prefiguration through the politics of the New Left in the 1970s, this phrase references the 1908 manifesto of the Industrial Workers of the World labor union.

15 Wini Breines, “The New Left and Michels’ “Iron Law,” Social Problems 27: 4 (Apr., 1980): 422.

16 For studies of non-left-leaning prefigurative politics see Lara Monticelli, “On the Necessity of Prefigurative Politics,” Thesis Eleven 167:1 (December 1, 2021): 99–118, https://doi.org/10.1177/07255136211056992.

17 Monticelli, “On the Necessity.”

18 Monticelli, “On the Necessity.”

19 Amanda Perry-Kessaris, Doing Sociolegal Research in Design Mode (London: Routledge, 2021).

20 Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42:1 (October 21, 2013): 329, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.

21 Fran Tonkiss, “Afterword: Economies of Infrastructure,” City 19:2–3 (May 4, 2015): 384–91, https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1019232.

22 Susan Leigh Star and Karen Ruhleder, “Steps Toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces,” Information Systems Research 7:1 (1996): 111–34.

23 Tonkiss, “Afterword.”

24 Jilly Traganou, “The Paradox of the Commons: The Spatial Politics of Prefiguration in the Case Of Christiania Freetown,” in The Future is Now: An Introduction to Prefigurative Politics, ed. Lara Monticelli (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), 144–60.

25 AbdouMaliq Simone, “People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg,” Public Culture 16:3 (Fall 2004), 407–29.

26 Suzanne Clisby and Julia Holdsworth, Gendering Women: Identity and Mental Wellbeing through the Lifecourse (Bristol: Policy Press, 2016), 9.

27 Tonkiss, “Afterword.”

28 Mark Johnson, “Migration Infrastructures, Surveillance and Practices of Care and Control: Filipino Muslims in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,” paper presented at the Anthropology of the Gulf Arab States II: Ethnography and the Study of Gulf Migration, MESA Annual Meeting, New Orleans, October 7–11, 2013, 18–19; (Middle East Studies Association) cited in Clisby and Holdsworth, Gendering Women, 10.

29 Luce Irigaray, This Sex Which Is Not One, trans. Catherine Porter (Cornell University Press, 1985), 171; cited in Clisby and Holdsworth, Gendering Women, 11.

30 Roger Mac Ginty, “Everyday Peace: Bottom-up and Local Agency in Conflict-Affected Societies,” Security Dialogue 45:6 (December 1, 2014): 548–64, https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614550899; cited in Yoana Fernanda Nieto-Valdivieso, “Women as Embodied Infrastructures: Self-Led Organisations Sustaining the Lives of Female Victims of Conflict-Related Sexual Violence in Colombia,” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 17:2 (August 2022): 2, https://doi.org/10.1177/15423166221100428.

31 Nieto-Valdivieso, “Women as Embodied Infrastructures”: 2.

32 Une Ville à Chandigarh, directed by Alain Tanner, written by John Berger and Alain Tanner (Switzerland: Artaria Film, 1966), 16 mm color, 51 minutes, accessed December 2, 2022, https://www.swissfilms.ch/en/movie/une-ville-a-chandigarh/84AFACD8D40C4CAAACE2B6F404866B96.

33 Donna Haraway and Thyrza Goodeve, Modest_Witness@Second_Millennium. FemaleMan_Meets_OncoMouse: Feminism and Technoscience (London: Routledge, 1997) cited in Chris Gilleard and Paul Higgs, “Unacknowledged Distinctions: Corporeality versus Embodiment in Later Life,” Journal of Aging Studies 45 (2018): 5–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j. jaging.2018.01.001.

34 Gilleard and Higgs, “Unacknowledged Distinctions.”

35 Chandigarh is the capital of the provinces of Haryana and Punjab, a portion of which was assigned to Pakistan in 1947.

36 Une Ville à Chandigarh.

37 Adrian Forty, Concrete and Culture: A Material History (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 128, cited in Sanoja Bhaumik, “Can Western Architecture Ever Be Truly Decolonial?,” Hyperallergic, June 27, 2022, http://hyperallergic.com/738421/can-western-architecture-ever-be-truly-decolonial/.

38 Russell Walden and Stanislaus von Moos, “The Politics of the Open Hand: Notes on Le Corbusier and Nehru at Chandigarh,” MIT Press Open Architecture and Urban Studies, April 22, 2021, https://mitp-arch.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/55ayllas/release/1 .

39 Bhaumik, “Can Western Architecture?”

40 Jilly Traganou, “Maintenance in Autonomy: Christiania’s Self-Managed Infrastructures,” paper presented at Maintainers III Conference, January 1, 2019, https://www.academia.edu/40812525/Maintenance_in_Autonomy_Christiania_s_Self_managed_Infrastructures.

41 Ann Snitow, “Greenham Common,” Occupy #3, n + 1, 2011, https://www.nplusonemag.com/dl/occupy/Occupy-Gazette-3.pdf.

42 Snitow, “Greenham Common.”

43 “Rebecca Mordan in Conversation: Greenham Common Women,” Wales Art Review, August 27, 2021, https://www.walesartsreview.org/rebecca-mordan-in-conversation-greenham-common-women/.

44 Spivak’s early notion of “strategic essentialism,” with all its risks, as a way of mobilizing identity in the context of negotiation or resistance—rather than as an anthropological category—might be pertinent here. The concept was introduced in “Feminism, Criticism and the Institution,” Thesis Eleven 10/11 (1984–85): 175–87, but was eventually abandoned in Gayatri Spivak, Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), xi, 432–33.

45 Snitow, “Greenham Common,” 45.

46 Jilly Traganou, “Wall Street as Border Zone,” in Design Studies Companion, eds. Penny Sparke and Fiona Fisher (London: Routledge, 2016), 31.

47 Alexandra Topping, “‘A Demonstration of Female Energy’: Greenham Common Memories,” The Guardian, August 22, 2021, UK news, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/aug/22/a-demonstration-of-female-energy-greenham-common-memories.

48 “Rebecca Mordan in Conversation,” Wales Art Review.

49 Sarah Jaffe, “Social Reproduction and the Pandemic, with Tithi Bhattacharya,” Dissent, April 2, 2020, https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/social-reproduction-and-the-pandemic-with-tithi-bhattacharya/.

50 See for example film documentation from “1980s Greenham Common, Women Protest for Peace, CND, Police,” YouTube video, Kinolibrary Archive, Clip ref AB66, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0TIXBJuwUcE, timestamp 1:48.

51 Anna Faulkner, interview with the author, October 2022.

52 Testimony of Bridget Boudewijn, https://greenhamwomeneverywhere.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Bridget-Boudewijn-and-Sue-Bolton.pdf.

53 Ann Snitow, “Pictures for 10 Million Women,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 8:2 (1985): 45, https://doi.org/10.2307/3346053

54 Snitow, “Greenham Common.”

55 Jack Halberstam, “The Wild Beyond: With and for the Undercommons,” in Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (New York: Autonomedia Press, 2013), 7.

56 Silvia Federici, “Feminism and the Politics of the Common in an Era of Primitive Accumulation (2010),” in Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction, and Feminist Struggle, ed. Silvia Federici (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2012).

57 Faulkner interview.

58 Kate Kerrow, “It Ain’t Just The Web, It’s The Way That We Spin It, Creating A Women-Only Space,” in Out of the Darkness, Greenham Voices 1981–2000 (The History Press, 2022).

59 Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labor (London: Zed Books, 1998), 77.

60 Michele Lancione, “Radical Housing: On the Politics of Dwelling as Difference,” International Journal of Housing Policy (April 2019): 1, 3, 5, https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2019.1611121.

61 Lancione, “Radical Housing”: 5.

62 Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), 31–32.

63 Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1959), 5, 154.

64 Arendt, The Human Condition, 38.

65 In Jaffe, “Social Reproduction and the Pandemic.”

66 Arendt, The Human Condition, 152.

67 Nancy Fraser and Rahel Jaeggi, Capitalism: A Conversation in Critical Theory (Cambridge: Polity, 2018), 32.

68 Karl Marx, Estranged Labour, Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of 1844, quoted in Tithi Bhattacharya, “Introduction: Mapping Social Reproduction Theory” in Social Reproduction Theory, ed. Tithi Bhattacharya (London: Pluto Press, 2018), 10.

69 Bhattacharya, “Introduction,” 2.

70 Traganou, “The Paradox of the Commons,” 155.

71 Meg Luxton, “Feminist Political Economy in Canada and the Politics of Social Reproduction,” in Social Reproduction: Feminist Political Economy Challenges Neo-Liberalism, eds. Kate Bezanson and Meg Luxton (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006), 36; cited in Bhattacharya, “Introduction,” 3.

72 Bhattacharya, “Introduction,” 10.

73 Kate Kerrow, Rebecca Mordan, and Frankie Armstrong, Out of the Darkness: Greenham Voices 1981–2000 (Cheltenham, UK: The History Press, 2022).

74 Jilly Traganou, “Girl with Maquette: A Memoir of Prefigurative Imaginaries at Work,” Arena: Journal of Architectural Research 7:1, 2022.

75 Bennett, Vibrant Matter.

76 Dean Spade, Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next) (London: Verso Books, 2020).

77 Spade, Mutual Aid.