Abstract

This paper explains the ambitions of Africa’s first independent nonprofit school of architecture—the School of Explorative Architecture—in light of the decoloniality ideas that were galvanized by the Rhodes Must Fall protests at the University of Cape Town in 2015. The paper describes the School’s three modes of teaching and learning architecture, namely the thing (professional competencies of designing a building), the shadow of the thing (theorized and critical thinking around buildings and architecture), and the painted shadow of the thing (creative acts engaging architecture in ideas and critical thinking). The paper explains the nuances of teaching and learning architecture in the South African context and the importance of teaching professional competencies while surfacing ‘other’ conditions through the painted shadow. The paper ends by asking if a radical spatial alterity—the folding of the thing, the shadow, and the painted shadow into each other—is possible.

Revolution and Reformation

When an antiracism activist threw a bucket of feces over the statue of Cecil John Rhodes at the University of Cape Town in March 2015, it ushered in a reformation—not quite a revolutionFootnote1—that perhaps has had an impact similar to Martin Luther’s reformation a few hundred years earlier. Where Luther had stuck his 95 Theses to the church door—the noticeboard of the university at Wittenberg—Chumani Maxwele used other kinds of signifiers that surfaced a deep well of tortured emotions and victimization. As he later noted, it was “unbearably humiliating to walk every day past a statue glorifying an undeniable racist.” Footnote2 The event and the emergent Rhodes Must Fall (RMF) movement set in motion a massive program of ‘decolonizing’ South African universities—in word, if not totally in deed—that arguably then spread through the Western world. Statues had fallen before the world over, but this was to be the reckoning that Western civilization needed to finally acknowledge the original sins that established its global dominance. In South Africa, however, the Rhodes Must Fall movement, paralyzing the University of Cape Town with ongoing protest action against ‘whiteness’ and its signifiers, spawned and morphed into a more violent Fees Must Fall (FMF) movement—activism that aimed at helping poor and Black South Africans access fee-free university education. This drew from the same well of torture and rage that had ignited the Rhodes Must Fall movement, as one of the protest leaders at the University of the Witwatersrand wrote:

Free education you capitalist pigs

Free education the shackles of your fat mine shaft deep pockets

Making us feel like we are illegally mining success through education

We have no hope for an escape like the miners of Lily Mine

We are stuck in the rubble of your stupidity, lies and greed

While you feed your piglets with luxury cars, food and bonusesFootnote3

South African universities came to a standstill with ongoing violence and disruption.Footnote4 Months of classes were canceled, and it was looking like the entire academic year would be lost and have to be repeated with enormous financial and societal impacts—for instance, the country’s entire cohort of the incoming fresher first-year students who would not be accepted to study at institutions that were already full, having to repeat the preceding year’s first year intake. On the 25th of September 2016, Dr Max Price, the then vice-chancellor of the University of Cape Town, presented a disturbing outlook for the university at an assembly of academic faculty; it was clear that if things continued as they were until the end of the year, then he could not guarantee the assembled academic staff their jobs—the university would close as it would be bankrupt. This is the moment that the School of Explorative Architecture was born—Africa’s first independent nonprofit school of architecture—with no backing finance and through no conspiracy or betrayal but rather through a fidelity to the project of architecture and the students and colleagues who might have no place to go should the RMF reformation turn into an FMF revolution.

The University of Cape Town survived, terribly wounded, with an academic year that was meant to end before December limping its way into February. The new academic year of 2017 started much later, with curricula and student vacations truncated and emergency catchup teaching plans enacted. The protests continued. When the then president Jacob Zuma was forced from office under a cloud of corruption at the end of 2017, he presented South Africa with the ‘remember me for this’ farewell kiss of fee-free higher education for those in need. The students had won, and violent protests simmered down, although they have never left the space of publicly-funded universities in South Africa since then. Universities such as UCT have been radically transformed as a consequence of the RMF and FMF protest action, at least demographically. With the classist handbrake of tuition fee payments released, student numbers and class sizes have rapidly increased, largely with ‘first generation’ students—those who are the first in their families to ever study at the tertiary level, although at UCT they have entered an institution in a state of chronic crisis.Footnote5

When the Rhodes statue was removed, the plinth on which it had rested was covered over with hoarding—the university was unsure as to how deep to cut to extract the rotten tooth and its poisonous abscess. A poignant memory of the statue was painted across the steps, reenacting the shadow the statue would have cast—a powerful reminder of the ongoing presence of colonialism and the work to be done for a full exodontic extraction, no matter how painful (). The shadow painted in the absence of the thing is also a powerful conceptual framework through which to think through other positions and concerns—which I do below.

Between the Thing, Its Shadow, and Its Painted Shadow

For Roland Barthes, all things that are conceived as creative acts necessarily conjure a shadow into being at the same time. This shadow, for Barthes, is where the thing becomes interesting:

There are those who want a text (an art, a painting) without a shadow, without the ‘dominant ideology’; but this is to want a text without fecundity, without productivity, a sterile text…. The text needs its shadow… subversion must produce its own chiaroscuro.Footnote6

The shadow is an easily understood prompt for thinking about architecture and its impacts; architecture casts a shadow. Buildings obviously cast shadows, both literal and metaphoric, but architecture as a discipline, practice, and profession, casts shadows as well. As a dark and foreboding presence, a shadow can be read, for example, as the negative impact that the object has on the environment and people that helped make it. It is the effect, directly or indirectly, that the building as a thing, or building as the verb act of architecture, has on a milieu. But the painted shadow presented in the Rhodes statue case above is not the shadow of the real thing, nor is it the prompt to interrogate, through an ideological repositioning, the logic that led to the building or, in this case, the Rhodes statue. The shadow that is of concern is a representation of a shadow, in other words an interest ‘twice-removed’ from an originating thing. The representation of the shadow is an attempt to make the ideological positioning (the first shadow) the real thing, and hence the thing to be re-presented, as opposed to the sculpture or a building that is a physical entity.

If that sounds confusing, then another example might help. Beatriz Colomina has produced seminal feminist analyses of Modernist masterpieces.Footnote7 This is evidenced in her writing on Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye and then also Adolf Loos’ Villa Muller. Both buildings have immensely important lessons for architectural design, namely, the architectural promenade in Villa Savoye, and then the spatial diagonal of the ‘raumplan’ in Villa Muller. These have produced innumerable iterations in contemporary architectural practice that have enlivened architectural design and radically changed architecture’s potential. As architects, and architectural theorists, we have a direct interest in how this thing called a building works or, more precisely, how space works in Villa Muller for example. However, Colomina identifies in Villa Savoye evidence—largely photographic—of ‘the gaze,’ and then in Villa Muller a compelling argument around the liberating potential of a feminist positionality, complicit in the surveilling diagonal spatiality of a circumscribed domesticity. In other words, if the ‘heroic’ architect is interested in space and spatiality, then the critical theorist is interested in the ‘shadow’ that the object casts—what this space and spatiality does or conceals—and what a feminist interpretation might reveal about architecture and its potential as an instrument of surveillance and power. The domestic bourgeois environment of these two ‘villas’ affords Colomina the opportunity to expose the shadow such gendered spaces generate; a rewriting of the buildings as museums might require a new kind of shadow investigation but the spatiality would, arguably, remain the same for both function types. In other words, the building as a thing has some inherent qualities or conditions, but a specific lens or sun angle might choose to highlight specific aspects that are then read as a cast shadow.

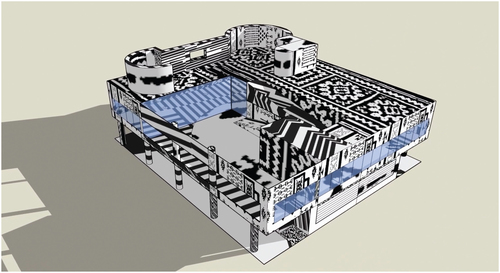

The painted shadow might be represented in the work of Stephanie Syjuco, a Filipino-American visual artist working in sculpture, photography, and installation art. Her work Ornament + Crime (Redux) Footnote8 is particularly apt as it combines Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye with Adolf Loos’s infamous ‘Ornament and Crime’ ethos. The exhibition installation presents Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye as a ‘dazzle ship’—a World War One strategy of painting a ship in geometrically obtuse and camouflaging zebra-like patterns—inspired here by overscaled Moroccan, Algerian, and Vietnamese folk-art patterns as a return of the repressed of France’s colonial atrocities; the plastic purism of Villa Savoye is denied by the distorting ambiguities of the surface pattern, literally deformed through the shadow of colonialism ‘painted’ directly onto the building surface (). The work is largely presented as a filmic ‘walk-through’ of a reconstituted Villa Savoye SketchUp model as well as a physical architectural model in the exhibition space. The exhibition press release rightly notes that the birth of Villa Savoye cannot be divorced from France’s coterminous colonies:

Figure 2. Stephanie Syjuco, Ornament and Crime (Villa Savoye) (still), 2013. © Stephanie Syjuco; Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York.

As a historical mash-up of publicly sourced files, this new version of Villa Savoye attempts to transcribe the colonial and cultural history of a Western icon back upon itself as if it were a body to be read and re-read. By infecting the visual cues of its colonies onto itself, a closer view of the society that birthed the building can be made.

As a further obfuscation of the originating object (the building as a thing), the use of an opensource SketchUp model revealed an unfaithful reproduction of the physically built Villa Savoye—a distortion—that reiterated the forming-deforming dual agency of colonialism. The work is a compelling commentary that has its deconstructivist sights set on the icons of architectural Modernism. It is important to note, however, that it does this not through a reworking of the spatiality of Villa Savoye but through a surface application, in other words through a painted shadow.

The painted shadow is an act of critique or revelation through a creative reimaging rather than an analysis of an existing artefact, object, or situation. In other words, if academics are interested in the shadow through the theorized and analytical frame of the essay format, then it is easy to see how students in a school of architecture might be interested in the painted shadow, or rather, painting their own version of the shadow through the representational mode of a studio project; the painted shadow is a creative act that brings radical insights through design, drawings, models, films etc. that explore an idea or rewrites or confronts or corrects a perceived injustice. Students can explore complex ideas about the world through the proxy painted shadow of a building. This slippage from the thing to its painted shadow is easily made in schools of architecture because, as Robin Evans notes in “Translations from Drawing to Building,” Footnote9 architects don’t build buildings but make drawings; they work on representations that are analogous to buildings. This is the key unacknowledged slippage that operates in schools of architecture around the world and is fundamental to the process of teaching and learning architecture. Here students find a rich seam to mine in that their work can be doubly removed from buildings by being focused on the representation—the painted shadow—of a range of concerns or commentary on ideas or issues such as social-spatial injustice. However, like the RMF painted shadow, this lens only captures one version of the complexity of the thing and is always removed from the thing itself; the shadow is frozen at the chosen sun angle illuminating the object but there are innumerable other potential shadows cast. The teaching and learning in these instances of the painted shadow can be intense and offer great depth while bringing a range of powerful awakenings—from finding a creative ‘voice’ to articulating a social-justice positioning to re-representing an issue that gains poignancy in its reframing. The transformative potential and educational potential of working with and making the painted shadow is immense, but it often lacks reference to the spatialized entity called a building. In other words, and as the Stephanie Syjuco Villa Savoye example demonstrates, the painted shadow becomes a thing in and of itself, but it tends to do this by being a 2D surface investigation lacking in spatial definition or relying on an existing 3D object to flatten into its representational surface.

The Value of the Painted Shadow in a Peculiar Context

At the School of Explorative Architecture, we recognize the potential deep learning that can emerge from working the painted shadow. By dislocating itself from its originating matter, meaning can float until it bumps into something unforeseen, emerging as a hybrid meaning machine, a new language, a new potential real. The painted shadow does not foreclose meaning and the transformative potential of educational cognitive fire but rather conjures them into existence. The painted shadow is simultaneously derivative and original. In the RMF example, the painted shadow derives from the originating act of colonialism and works as an original commentary on it. However, as Derrida’s deconstructionist process might note, with a reframing the painted shadow itself might become the dominant binary, subverting the originating logic and destabilizing established hierarchies. The deconstructionist meaning could be double-downed—twice removed?—to allow the representation to usurp the importance of the tangible object itself, as one would expect in an economy that trades in ideas rather than things. In other words, a representation of the idea of a building, drawn to establish its complicit nature, can be seen to be more ‘useful’ than the building itself—at least in the ‘marketplace of ideas’ as opposed to the ‘marketplace of things.’ This is the power of architectural design projects as research and commentary, as so ably demonstrated in the recent 2023 Venice Biennale “The Laboratory of the Future” curated by Lesley Lokko.

Indeed, the point needs to be made that until Lokko introduced the Architectural Association derived ‘Unit system’ in 2015 at the University of Johannesburg, architecture teaching and learning in South Africa had never really worked in the painted shadow. Teaching and learning at university level focused almost entirely on training architects to design buildings, with occasional forays, through theory courses, into the ideological shadow cast. The peculiar context of South Africa might explain this apparent lack of engagement with the painted shadow, and I would like to suggest a few reasons. As a gross generalization, it seems fair to claim that South Africans tend to be unreflective literalists (the legacy of Calvinist frontier settler colonialists who saw only one causal relationship between a hammer and a nail?); you study architecture to be able to design buildings—to become an Architect!—and not to explore ideas. On top of that the South African Council for the Architectural Profession has a fairly comprehensive set of prescribed professional competencies that leave little room for unexplored ideas and unknown possibilities. There is also perhaps a more complex and underexamined reason that stems from academic staff being historically made up of white middle-class progressives/liberals who had to confront, in their everyday lives, the literal abhorrent nature of apartheid and its spatial strategies of segregation and deprivation.Footnote10 Studio projects dealing in the abstract and abstruse world of the painted shadow would be morally repugnant in the face of harsh realities of the built environment in which the lives of apartheid’s subjugated masses had to suffer immense daily indignities; it seemed far better to have students design community halls or better housing and thereby suggest a hopeful future beyond the deprivation. In the face of such lack, such a crisis, the painted shadow can be seen to be a privileged indulgence (students all over the world might now be feeling a similar morally curtailing imperative brought on by the climate emergency). Most schools of architecture in South Africa continue this practice of dealing with the social realism of apartheid’s townships, but through the safe space of the design studio: ‘working in the townships’ from the safety of the ivory tower. At SEA we aim to be faithful to the social realism of our context and value the transformative power that working in the painted shadow might have for students in their personal and creative capacities and future abilities to act in and on the world and to establish new ways of thinking and being in it.

Spatiality and Professional Competencies

To be sure, architecture as a profession trades in things called buildings and not their twice removed representations—although Daniel Libeskind’s impressive built catalogue can attest to the power of the painted shadow as a route to built work. While buildings can be found, upon interrogation, to cast many shadows, their defining characteristic is arguably space and spatiality.Footnote11 In the practice of architecture there are many complex and contradictory requirements at play in the conjuring of a coherent building, but space and spatiality are arguably the engine of architecture. Even without the crude determinism of functionalism, ‘how space works’Footnote12 is a fundamental teaching and learning imperative in an architectural education. Another way to think about space is that it is the grammar of a building, giving it coherence while avoiding clumsy phrasing. To most students of architecture, who are learning design as if a new language—and especially spatially complex architectural design—this is the most difficult lesson to get right. Most people arguably come to architecture understanding it as an object to be admiredFootnote13—‘pretty as a picture’—rather than a spatially complex organism. Even in ‘the real world’ the pressure to treat architecture as a pretty picture is a compelling demand that invites students to stay in a representational world with little spatial integrity—which as Robin Evans notes, is already the world in which architects work. In architectural education, space, and the techne of putting a building together, have the danger of being marginalized by the more exciting, discursively rich, and immediate power of the painted shadow—especially in the Unit system—which, unlike a design for a building, adequately and satisfactorily concludes its life when pinned up on the review wall. As transformative as working for two years in the painted shadow of a design Unit might be, we believe in making sure that the defining and essential aspect of our discipline and its professional know-how, namely space and spatiality, is thoroughly and explicitly engaged with in our curriculum.

There is another, more complex, reason to remain faithful to ‘how space works’ and the techne of building in our educational work. While it is perfectly understandable that not all students study architecture to become architects and that there is deep learning—as we insist!—in the architectural education process that transcends professional competencies, there is a socially relevant context in which we teach at the School of Explorative Architecture. In South Africa, architecture and ‘first generation’ students present a prime example of Pierre Bourdieu’s problematizing ‘cultural capital.’Footnote14 Increasingly, students of architecture have informal settlements as home environments with a local high school or maybe a library being the only representative of formal architectural work. The horizon and form of capital A architecture disappears in the surrounding sea of shacks (). Houses in the formal sectors of apartheid’s townships are often 30 square meter (320 sq. ft.) one bedroom free-standing units that house extended families—which in turn set the horizon of what architecture can be, very close. Obviously, there are many lessons for architectural educators and students to gain from these ‘other’ contexts that can also provide students from these contexts with the inside lane on other teaching and learning projects, for example the structuralist emergence of an informal settlement spatiality,Footnote15 or the place-making potential of communal water taps as a reimagined village well.Footnote16 It should not be forgotten that students from these ‘informal’ contexts are studying architecture so that they might escapeFootnote17 these intense, and at times inhumane, environments and enter the formal economy—no matter what the learning potential these environments suggest, or whether studio projects set within these contexts are instances of fetishized or romanticized poverty as sometimes happens. Indeed, studies show that first-generation students from these contexts are expected, after graduating with a three-year undergraduate degree, to immediately start contributing income to an extended family by being instantly helpful and employable in an architect’s office.Footnote18 First generation students’ lack of cultural capital A architecture in this regard places them at an enormous disadvantage, while at the same time it has the potential to ‘turn the tables’ on more affluent students and their lack of experience in these contexts. Helping students overcome class immobility, and the constraints of what are essentially racialized ghettos, by providing the steppingstones to eventually registering as a professional architect with core competencies of ‘putting a building together’ must be fundamental to our mission—as well as engaging and validating ‘other’ experiences and realities. Again, it must be spatiality, and the painted shadow, core competencies and skills and a liberating and transformative discourse through representation—not just the reductive focus of making our students ‘work ready.’ Our ambition must be to validate the experience and social reality of students—and surface the potential hidden richness of this ‘shadow’ world—while also helping build the bridge for them to access a spatially and technologically complex world of normative architectural production. As we will see below, this ‘both/and’ ambition is literally embedded within our curriculum structure.

Agency and Radical Spatial Alterity

The scenarios sketched out above suggest that there are a range of conflicting ‘fidelities’ to manage in the development of an architectural curriculum that is both generic and germane, spatial and representational, professionally competent and contextually relevant—at least in South Africa. These conflicting fidelities can nevertheless be held by a single overarching concern, and that is for ‘agency.’ Agency is arguably the key defining condition or ambition of education—the empowering of students to act in and on the world (although we are not pure instrumentalists in this regard and understand that it is contestable as to which world and for whom they must act). As a curriculum manages and balances these conflicting fidelities it can nevertheless foreground agency as a dominant outcome no matter the mode, or combination of modes, deployed in the educational space.

At SEA our curriculum is a fairly bald structure, aimed at covering three modes of architecture and the attendant potential for developing agency in each: the thing (professional competencies and the spatiality of architecture as found in ‘Thinking Practice Studio’—although done through a critical lens), the shadow of the thing (the various ‘Theory’ courses that locate buildings and architecture in a social-cultural-political milieu), and the painted shadow which has the potential to be made manifest in the ‘Studio elective’ courses which are essentially semester long mini-Units. These courses and their ambitions might be familiar to most educators and architectural students, although they might not find them so baldly embedded in a curriculum that spends half the year exploring and validating the painted shadow and its other situatedness, and the other half bedding down normative architectural design thinking and learning. It is important to note that such ‘boundaries’ simply set up an overarching schema through which to have a global view of the teaching and learning process and that there is precisely a blurring across these boundaries which makes teaching and learning architecture such a powerful and transformative experience.

What is perhaps unusual for most schools of architecture would be our ‘Building Studies’ courses. These aim to use buildings as a site through which to read architecture in a holistic manner by exposing the range of conflicting complexities a building holds, from technology to material matters to stories of sustainability, from history to building types and cultural signifiers, from economics to philosophy. We miss the surety of the history survey and its simplifying narrative and centuries of scholarship, but Building Studies prompts us to draw intersecting lines from a contemporary building to an old one, or to a vernacular one, or to a scientific appraisal such as a thermal study, to a feminist reading, or to understand the origins of a structural system, or the role of a community in the design of a building. As architects, we understand the importance and pedagogical power of these intersecting narratives, and in the end, we can convince ourselves that we don’t miss the Eurocentric predominance of the history survey and its simplifying narratives too much.

Two things are missing from this abridged story of our curriculum: firstly, the ‘other’ contexts—the social realism of ‘the townships’—that privilege those ‘first generation’ or working-class students, and secondly, what could be identified as radical spatial alterity. Within these contexts and projects, we could ask how social realism meets magical realism, how the practice of the everyday can emerge from the shadows as a radical spatial alterity that talks back to the material conditions in an explorative and expositionary way. To be clear, radical spatial alterity remains an elusive conceit. It is elusive because the painted shadow finds it difficult to be formed into a thing, but also because we don’t really know what ‘radical spatial alterity’ is—although emerging cultural practices such as Afrofuturism hint at one possible potential. For a school of explorative architecture, we are comfortable not knowing how this exactly will work, but we have it as an ambition, a naïve or vain (a palindrome) tilting at windmills perhaps. I say ‘naïve’ or ‘vain’ because architecture, as building at least, is by nature conservative and this forecloses the horizon of spatiality. It does this by engaging an ergonomically predetermined (although not always bipedal) human, by engaging the laws of gravity and physics in general, and by being built by client’s money, not to mention bolstering institutions such as ‘the family home.’ Moreover, it demands a usefulness factor—a machine for living in—that cannot countenance alien inhabitation, a kind of otherness inhabiting the body of architecture itself. Architecture as a profession and a normative practice, if not predominantly in service of Capital and privilege, at the very least likes to think that it is bringing a useful order and built environment to a chaotic and troubled world, or, depending on your politics, bolstering social hierarchies and inequity.

It is no wonder that the ambitions of ‘radical spatial alterity’ by necessity reject this inherent conservatism and try to find ‘other ways of doing architecture’—as the Spatial Agency group helpfully enumerate.Footnote19 An immediate approach is for architects to work as if ethnographers examining ‘other’ kinds of spatial praxis—ranging from migrant worldsFootnote20 to a close reading of the surprising use of home-work space in pandemic LondonFootnote21—and hence talk back to the taken-for-granted mores of Western or capitalist spatial practice and open the realm of possibility for other kinds of spatial praxis. However, in terms of using the agency of architects as designers enacting change, there is a limit on how ‘radical spatial alterity’ is enacted. Apart from design-build projects, this tends to bifurcate into social-spatial activism around the real clients—the users of the building as marginalized community where no ‘thing’ is designed but rather a process of agency is facilitated or inculcated—or else remains in the congenial playpen of the painted shadow (where it is impossible to adequately simulate ‘community participation’ in a design studio project). In other words, a radical spatial alterity tends to look so far away from the everyday practice of architectural design for its rationality that it erases spatiality and replaces it with real-world social-justice activism of community-led empowerment processes, or at least pretends to do so through the permissive simulacra environment of the painted shadow. The teaching and learning at SEA does not shy away from this complexity—especially in the First Year engagement with urban farmers in the Cape Town townships of Langa and Khayelitsha. There should also, however, be a way in which the painted shadow is ingested by, or ingests, spatial practice and thereby forms a potential radical spatial alterity. We hope to find out how.

Does a radical spatial alterity exist? If so, what does it look like? What are its dimensions? What are its tectonic and architectonic approaches? How do we represent it? What are its translations from drawing to building? Olalekan Jeyifous’s Shanty Mega-Structures of Lagos, Nigeria are compelling images suggesting exactly this, but they offer no spatial articulation except as objects viewed from a distance. Constant Nieuwenhuys’s 1960s ‘New Babylon’ is also a touchstone in this regard, imagining a post-capitalist society of homo ludens, New Babylon being the infrastructure facilitating and encouraging pleasure, play and anything-goes creativity. For all their libertarian looseness, Nieuwenhuys’s scaled architectural drawings and models are richly suggestive of another kind of architecture that moves from within the depths of the painted shadow back to the thing itself. But somehow, they are not enough. Perhaps we need to return to direct embodied action—translations from building to building—and follow on with another ‘New Babylon’—this time hand-made by one of South Africa’s greatest sculptors and shamanistic visionaries, Jackson Hlungwani.Footnote22 Or perhaps we can just proceed with our own visions and see where they take us, as I do as a conclusion below.

The Meanings of SEA

This is the ambition of SEA—to find different ways to help students move from the painted shadow back to the thing and then back to the painted shadow again, to perhaps unlock the potential of a radical spatial alterity. We believe that this can be held within the nondualistic frame of emerging African philosophy,Footnote23 the ontological enframing of ‘vital force’ that connects disparate entities of human and nonhuman actors.Footnote24 As Leopold Sedar Senghor notes:

As far as an African ontology is concerned, too, there is no such thing as dead matter: every being, everything—be it only a grain of sand—radiates a life force, a sort of wave-particle; and sages, priests, kings, doctors, and artists use it to help bring the universe to its fulfillment.Footnote25

We encourage our students to be enthusiastic explorers across the different ‘zones’ of contradicting and conflicting fidelities, but to find the dialogical relatedness between them, to ride these wave particles. Whatever the zones of operation, our ambitions of agency and student empowerment are to inculcate a love of exploring, a fearlessness in a world of rising fearfulness, an ‘anything goes’Footnote26 that is willing to go anywhere. The School of Explorative Architecture has a useful acronym in this regard: SEA. We are hyper-aware of the associated meanings, both good and bad, and the potentially problematic language of ‘heroic’ exploration; if the sea brought us life, it also brought us trouble, the theta Phoenicians and the dhow and then the schooner and the slaver and colonialism. It brought us the sea of sand, a desert as a smooth space across which nomadic ships sail, the oil of ancient sea-life beneath their feet—it has brought us that catastrophe. It also brought us the horizon, and the sea of the moon, the moon in the sea. And so, like the ship that sailed to Mars,Footnote27 we are setting the controls for the heart of the sun. We are thinking beyond the horizon, which is the limit of what we know. We are more than a ship of fools, exiled offshore to survive social upheaval; we are building a community, we are building the ship as we sail it, a dynamic and agile institution floating in space and yet embedded in the land painted with shadows.

The sea is the salt of all life, a creative battery brine that charges us with uncertain potential; this is what keeps us going. Into the sea of doubt we flood, as the sea of doubt floods us. We don’t mind, we are happy to go there.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nicholas Coetzer

Nicholas Coetzer is a research-based associate professor at the University of Cape Town with a PhD from The Bartlett, University College London. He is also director of the School of Explorative Architecture (RF) NPC, Africa’s first independent, nonprofit school of architecture. He is the author of two books, An Architecture of Care in South Africa: From Arts and Crafts to Other Progeny (2023) and Building Apartheid: On Architecture and Order in Imperial Cape Town (2013), both of which are published by Routledge. As a registered architect in South Africa, he also occasionally finds time to practice.

Notes

1 Musawenkosi W. Ndlovu, #FeesMustFall and Youth Mobilization in South Africa (London: Routledge, 2017).

2 As cited in Amanda Castro and Angela Tate, “Rhodes Fallen: Student Activism in Post-Apartheid South Africa,” History in the Making 10 (2017): 205.

3 Bafana Nicolas Masilela, “Free Education,” in Crispen Chinguno et al., Rioting and Writing: Diaries of Wits Fallists (University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg: Society, Work and Development Institute, 2017), 78.

4 For insider accounts from the academic and administration experience see David Benatar, The Fall of the University of Cape Town: Africa’s Leading University in Decline (Johannesberg: Politicsweb Publishing, 2021); Max Price, Statues and Storms. Leading Through Change (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2023).

5 UCT is experiencing a crisis of governance: See Norman Arendse’s report on the University of Cape Town’s website titled ‘Council Adopts Independent Panel of Investigation Report’. This was accessed today, January 24, 2024. https://www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2023-11-01-council-adopts-independent-panel-of-investigation-report.

6 Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text (New York City: Hill and Wang, 1975): 32.

7 Beatriz Colomina, “The Split Wall: Domestic Voyeurism,” in Jennifer Bloomer, Sexuality and Space (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1992).

8 This work can be found on the Ryan Lee Gallery’s website, accessed January 24, 2024. https://ryanleegallery.com/exhibitions/stephanie-syjuco-ornament-crome-redux/

9 Robin Evans, “Translations from Drawing to Building,” in Robin Evans, Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997).

10 Mamphela Ramphele, A Bed Called Home: Life In The Migrant Labour Hostels of Cape Town (Cape Town: David Philip Publishers, 1993); Julian Cooke, For a Home, People Die: A Community Struggle Makes a Post-Apartheid Model (Cape Town: Julian Cooke, 2021); Nicholas Coetzer, An Architecture of Care in South Africa: From Arts and Crafts to Other Progeny (London: Routledge, 2023).

11 For an exposition of the emergence of ‘space’ as a key driver of contemporary architecture see Adrian Forty, “Space,” in Adrian Forty, Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004).

12 Bill Hillier, Space is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture (London: University College London, 2007).

13 A good example of this is the focus on the ‘look’ of architecture and a complete absence of a concern with ‘space’ as demonstrated in Alain de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2006).

14 Pierre Bourdieu, “The Forms of Capital,” in John Richardson, Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1986): 241–58.

15 Matthew Barac, “From Township to Town: Urban Change in Victoria Mxenge TT Informal Settlement, Cape Town, South Africa” (PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, 2007).

16 Nicholas Coetzer, “An Oasis of Safety in the Urban Desert,” Cape Times, July 30, 2013.

17 We should also not begrudge those RMF or FMF leaders who have subsequently entered the working world; for example, Bafana Nicolas Masilela, who penned the “Free Education” poem noted at the beginning of this paper, has subsequently listed his work attributes as: “Business Coach | SMME & Corporate Wellness Consultant | Counselling Psychologist| Founder and CEO of i-Wellness.”

18 Arinao Mangoma and Anthony Wilson-Prangley, “Black Tax: Understanding the Financial Transfers of the Emerging Black Middle Class,” Development Southern Africa 36:4 (2019): 443–60.

19 Nishat Awan, Tatjana Scheider, and Jeremy Till, Spatial Agency: Better Ways of Doing Architecture (London: Routledge, 2011).

20 Huda Tayob, “Subaltern Architectures: Can Drawing ‘Tell’ a Different Story?” Architecture and Culture 6:1 (January 2018): 203–22.

21 Frances Holliss and Matthew Barac, Work Home: Housing Space Use in the Pandemic and After: A Case for New Design Guidance, (London Metropolitan University: The Workhome Project, 2021).

22 Jonathan Noble, “Like a Fish in Water: The Smooth Hybrids of Jackson Hlungwani,” SAJAH 32:2 (2017): 120–31.

23 Harvey Sindima, “Community of Life,” in Charles Birch, William Eakin, and Jay B. McDaniel, Liberating Life: Contemporary Approaches to Ecological Theology (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1990), 137–49; Michael Onyebuchi Eze, “Humanitatis-Eco (Eco-Humanism): An African Environmental Theory,” in Adeshina Afolayan and Toyin Falola, The Palgrave Handbook of African Philosophy (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017); Mogobe B. Ramose, African Philosophy through Ubuntu (Harare: Mond Books, 1999).

24 Pius Mosima and Nelson Shang, “We Live in Paradise: Beautiful Nature in African Tradition” in Bolaji Bateye, Mahmoud Masaeli, Louise Müller, and A. C. M. Roothaan, eds., Beauty in African Thought: Critical Perspectives on the Western Idea of Development (Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books, 2023).

25 Léopold Sédar Senghor, “Negritude: A Humanism of the Twentieth Century,” in Gaurav Gajanan Desai and Supriya Nair, Postcolonialisms: An Anthology of Cultural Theory and Criticism (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2005): 183–90.

26 Paul Feyerabend, Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1970).

27 William Timlin, The Ship that Sailed to Mars: A Fantasy (London: George Harrap, 1923).