ABSTRACT

This case study explores arts-based teaching and learning in generalist teacher education by focusing on student teachers’ aesthetic learning processes in a professional workshop. The workshop is included in a Norwegian teacher education programme, where the student teachers learn about and through aesthetic learning processes. By asking what the student teachers emphasise about the learning processes, the study seeks an in-depth understanding of the case from student teachers’ perspectives. Multiple qualitative data sources have been analysed holistically and interpretatively, leading to three categories that reflect emotional, intellectual and practical qualities of aesthetic learning processes. The findings and the discussion highlight how the learning processes expand student teachers’ perception of learning, as well as how emotions seem to constitute a moving and cementing force in creating spaces for new understandings. Student teachers’ professional development in arts-based teaching and learning is further discussed.

Introduction

Arts-based teaching and learning is a current topic in many generalist teacher education programmes and can be related to a wide range of concepts and expressions, emphasising the use of arts and aesthetics as teaching approaches across and beyond subjects and curriculums (Møller-Skau & Lindstøl, Citation2022; Ogden et al., Citation2010; Oreck, Citation2004). Research highlights how these approaches to teaching and learning have qualities that are central for future education by emphasising their significance in promoting creativity (Burnard et al., Citation2015; Selkrig & Bottrell, Citation2018; Watson, Citation2018), critical thinking (Chappell & Chappell, Citation2016; Jones & Hall, Citation2009; Nilson et al., Citation2013) and diversity (Hall & Thomson, Citation2007; Harris & Lemon, Citation2012; Shockley & Krakaur, Citation2021).

When student teachers learn in and through the arts and aesthetics (Bamford, Citation2006; Fleming, Citation2011), their experiences are often perceived in the context of deep (Brekke & Willbergh, Citation2017; Giorza, Citation2016; Pool et al., Citation2011) and transformative learning (Bhukhanwala et al., Citation2017; Patterson, Citation2017; Selkrig & Bottrell, Citation2009). Aesthetic theories also describe how the learning processes activate senses, emotions, bodies, imagination and cognition in complex interactions (Dewey, Citation1934; Eisner, Citation2002; Greene, Citation1995). However, research (Barnes & Shirley, Citation2007; Ogier & Ghosh, Citation2018; Selkrig & Bottrell, Citation2009) has shown that many student teachers experience discomfort, fear or nervousness when participating in teaching approaches where arts and aesthetics are emphasised. The cited researchers imply that future teachers, especially those with few experiences in the arts, often find the teaching methods and learning processes challenging and demanding. It therefore seems that the teaching methods require student teachers to be more creative, open-minded and risk-taking than many of them are familiar and comfortable with. In this regard, the research field of arts-based teaching and learning in teacher education seems to mirror conflicting aspects.

In Norway, where this study was conducted, arts-based teaching and learning can be viewed in the context of the umbrella term aesthetic learning processes (By et al., Citation2020; National Council for Teacher Education, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). All student teachers, educating to be primary and lower secondary school teachers in Norway, should be able to facilitate aesthetic learning processes in schools after graduation (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). According to the National Council for Teacher Education (Citation2018a, Citation2018b, p. 10), student teachers must practice their ability to create, interact, reflect and communicate through aesthetic elements and tools and be able to facilitate creative learning through aesthetic expressions, communication and performances. Considering this, ‘aesthetic learning processes’ constitutes an interdisciplinary topic in Norwegian teacher education, where aesthetic approaches to teaching and learning are intended to work as integrated elements of student teachers` education. Despite this, a national report (By et al., Citation2020, pp. 69, 74, 78) addresses the point that the education student teachers receive in this topic lacks a systematic and comprehensive structure. The report also emphasises the need for research on teaching and learning from an aesthetic perspective in the context of teacher education, which could contribute to the understanding of aesthetic learning processes.

The need for research about arts-based teaching and learning in generalist teacher education on an international scale (Bamford, Citation2006; Møller-Skau & Lindstøl, Citation2022) and regarding aesthetic learning processes in the Norwegian context (By et al., Citation2020) illuminates the need for more knowledge. In many teacher education programmes, interdisciplinary arts-based approaches could be the only education in creativity, arts and aesthetics that many student teachers receive, unless they choose arts as core subjects. Further knowledge could therefore strengthen all student teachers’ ability to facilitate aesthetic learning processes in schools. As these approaches to teaching and learning also appear challenging for many student teachers (Barnes & Shirley, Citation2007; Ogier & Ghosh, Citation2018; Selkrig & Bottrell, Citation2009), this may inhibit their professional development. Additional knowledge about these issues in teacher education could therefore increase teacher educators’ awareness of the elements that promote aesthetic learning processes in teacher education. Being an educated teacher, who has worked with aesthetic learning processes in primary school for ten years, I have also gained embodied experiences about the significance of having knowledge and skills regarding arts-based practices in school.

Therefore, in this study, I seek an in-depth understanding of what student teachers emphasise when they are introduced to aesthetic learning processes as a topic and learn through them in a one-week professional workshop, which is included in a Norwegian teacher education programme. The research question is as follows: What do student teachers emphasise about aesthetic learning processes during their participation in a professional workshop? The study can be regarded as an intrinsic case study where the aim is to gain an in-depth understanding of an individual case that in itself is of interest (Stake, Citation2005). Multiple qualitative data sources have been analysed holistically and interpretatively in order to explore the case (Creswell, Citation2013; Stake, Citation2005), and the theoretical foundation is centred on the concept of aesthetic experience by John Dewey (Citation1934).

Aesthetic learning processes as aesthetic experiences

Among multiple perspectives in the field of education, emphasising the interplay among arts, aesthetics, experiences and learning, Dewey’s (Citation1934) aesthetic theory is a fruitful lens in this study, as it invites educational researchers and practitioners to explore aesthetic practices and how they can be perceived as meaningful for the people involved. Alternatively, Dewey’s (Citation1934, pp. 36–59) theoretical perspective emphasises human experiences and how they can be enriched, expanded and challenged through arts, aesthetic expressions and communication. Considering this, Dewey (Citation1934, pp. 36–59) turns to the concept of aesthetic experiences to explain what occurs when the senses, bodies and imagination are put into play in arts and aesthetic activities and when humans are present, active and immersed in them. According to Dewey (Citation1934, pp. 56–57), aesthetic experiences involve three different phases that are integrated elements of experiences. The phases can neither be separated from nor set against one another but constitute a unity or wholeness, and Dewey (Citation1934, pp. 56–57) regards them as aesthetic qualities.

The emotional phase is the binding element that ‘rounds out’ the experience into completeness, unity or wholeness. In this way, an emotion is an aesthetic quality that gathers different aspects of how something is experienced. However, emotions are not simple, compact or one-sided, and Dewey (Citation1934, p. 43) refers to them as ‘qualifications of drama’ that ‘change as the drama develops’. This implies that aesthetic experiences could be perceived as comprising a kind of ‘emotional drama’, where a wide range of emotional aspects move the experiences forward and create intensity and immersion. The intellectual phase involves the stage when humans draw meaning from the experiences (Dewey, Citation1934, p. 57). Dewey (Citation1934, pp. 17, 46) emphasises how arts and aesthetics can create connections in human perception because doing something and perceiving something aesthetically are closely attached. In the same way, arts and aesthetics reinforce past and present experiences, and by drawing these connections, Dewey (Citation1934, p. 46) argues that experiences gain depth and breadth. Aesthetic experiences could therefore be understood as human processes where arts and aesthetics work as dynamic forces in connecting experiences and creating meaning. Finally, the practical phase can be related to how humans interact with arts in their surroundings and adjust their experiences to new actions and experiences. Dewey (Citation1934, p. 45) states that ‘every experience is the result of an interaction between a live creature and some aspects of the world in which he lives’. He refers to experiences as a mutual adaptation that emerges between the self, the others and the objects that interact in events. An aesthetic experience is thus depicted as a human interaction with arts and aesthetics intertwined in the specific context or situation in which it takes place. Alternatively, it could be perceived as ‘an adaptation’ between elements interacting in the same process or unity.

In this study, the three phases have implications for the way that I view teaching and learning that involve arts and aesthetics. By this, I imply that aesthetic learning processes can be perceived as aesthetic activities, actions or practices in didactic and pedagogical contexts, where human experiences are developed, challenged and expanded through emotional, intellectual and practical qualities. In my interpretation, I therefore approach aesthetic learning processes through these qualities, brought forth through the characteristics of the arts.

Methods

With the aim of gaining an in-depth understanding of an individual case, this research can be regarded as an intrinsic case study (Creswell, Citation2013; Stake, Citation2005). An intrinsic case study is defined by its focus on a case that in itself is of interest, rather than representing a specific problem or other cases (Stake, Citation2005, pp. 443, 445). Multiple qualitative research approaches have been applied to explore the case. The empirical data consist of teaching materials, two days of video recordings, two days of field notes from observations, 121 comments/reflections obtained from a digital padlet, eight student assignments and audio recordings/transcripts of four semi-structured research interviews (one individual/three group interviews). The choice of using several data sources is based on the study’s case design, which highlights the importance of using multiple perceptions to clarify meaning (Stake, Citation2005, p. 454). The sample consists of 20 second-year student teachers, aged 20–30, and one university teacher educator. In the interviews, I chose to delve deeper into the research question. Therefore, five student teachers participated, four of whom were interviewed twice.

Analytically, I first approached the multiple data sources holistically (Creswell, Citation2013, p. 100) by creating an overview of the workshop. At this point, I focused on my secondary sources, which were the teaching materials, video recordings, field notes from observations, reflection notes/comments and assignments. Thereafter, I searched for complex details of the case by using the interviews, which were the primary sources of my interpretation. I condensed the meaning conveyed in the interviews and searched for significant elements. Eventually, I approached these various scopes as pieces of a whole (Creswell, Citation2013; Stake, Citation2005) and with the aim of understanding ‘what is important about the case within its own world’ (Stake, Citation2005, p. 450). Considering these points, I focused on what the student teachers talked about but simultaneously paid attention to what they wrote about, what they did, how they acted, and what they reflected on, created and chose. During the analytical process, I went back and forth between data and theory to create a base for my interpretation (Stake, Citation2005, p. 460).

All formal and ethical considerations were considered during the research study. I obtained approval from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (no. 884976), gathered formal consent forms and facilitated safe data storage. The purpose of the study and the informants’ rights were clearly expressed in the formal consent form. I was also present in the classroom and had the opportunity to inform the whole class about the purpose of the study using less formal language and with the aim of establishing a trustful environment. I still had to prepare other solutions if some student teachers declined to participate. In such a case, my plan was to drop the idea of using the whole class as informants and instead, reduce the sample by focusing on those student teachers who wanted to participate.

I also needed to reflect on the meaning of asymmetric relations and power (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2015, pp. 42, 97) before entering the research field. For example, my research position in this study was neither objective nor distant but close to the research field and the context that I explored. Being the colleague of the teacher educator, I was aware that my presence in the room as a researcher and observer could influence the student teachers. For example, the way that I was interacting with the teacher educator during the week could possibly affect what the student teachers preferred to tell me in the interviews. Considering this, I tried to be clear that I appreciated their honesty and immediate reflections about the teaching experiences.

The context – elaboration on the workshop

The workshop was held on a university campus (with approximately 5,000 students and 100 study programmes), located in a middle-sized town in the south-east of Norway. The students participating in the case study were studying to be primary school teachers, and the professional workshop was part of a pedagogy course. A teacher educator at the university was responsible for the workshop, and a primary school teacher participated as a co-mentor. In the workshop, the teacher educator focused on the youngest pupils in schools by choosing theory, research and teaching examples for the lectures which dealt with this group of pupils. The teacher educator also conceptualised ‘learning’ as socially constructed, mediated through social and cultural interactions. The students that participated had some prior experiences with aesthetic teaching from their first year in teacher education but had not yet been introduced to ‘aesthetic learning processes’ as part of their curriculum. The students’ reflections and comments indicate their lack of knowledge about the topic upon joining the workshop. Additionally, their aesthetic preferences seem to represent ordinary aesthetic practices, such as listening to music, knitting, cooking, dancing, painting and reading.

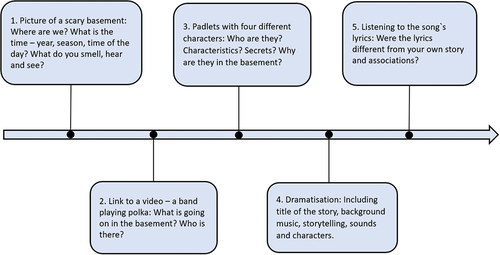

On the first day of the week-long workshop (Monday), the students were introduced to the topic ‘aesthetic learning processes’. The teaching was centred on practical activities, which were mostly conducted together as a whole group, led by the teacher educator. Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, the students had to maintain physical distance and remain seated during the lessons. This limited their opportunities to explore materials, space and bodies in the classroom. Instead, the teacher educator deconstructed a song’s lyrics and used its elements, following a timeline on a padlet (a digital teaching tool). These elements became the foundation for creative writing, storytelling and dramatisation (see ). The story grew out of sensory and imaginative experiences and associations, as the students were asked to write creative pieces based on images (showing an old basement and different characters) and music that reflected the elements in the song’s lyrics. The teacher educator encouraged the students to imagine how aesthetic elements, such as sounds and smells, were present in the story.

Figure 1. Figure that illustrates activities in the workshop (creative writing, storytelling and dramatisation).

After the session, the teacher educator scaffolded the learning by lecturing on the topic of ‘aesthetic learning processes’ and assigned several tasks with questions, where the students reflected on aesthetic learning processes and related topics. The teacher educator emphasised elements such as sensory, embodied and emotional experiences, aesthetic qualities in teaching and learning, variations in teaching methods, playing and various examples of art projects. At the end of the day, the students were given a group assignment that would be presented on the last day of the workshop (Friday). The assignment challenged them to create a digital, visual story or a podcast about aesthetic learning processes. Academic content and practical examples of how to facilitate aesthetic learning processes in school were required as part of the assignment. The students were asked to connect aesthetic learning processes to various topics, including deep learning, didactics, fiction, assessment, playing, friendship, reading and writing.

After working on the assignment in groups on Tuesday, the students arrived at the university for mentoring on Wednesday. The teacher educator and the primary school teacher participated as mentors. The primary school teacher was also interviewed by several students in order to use these interviews in their digital stories and podcasts. The primary school teacher gave examples of aesthetic learning processes and playful teaching with the youngest pupils. For the same purpose, many of the students visited schools on Tuesday and Thursday to interview pupils and teachers. On Friday, the students presented their digital visual stories and podcasts and discussed the processes and the products together with the whole group and the teacher educator.

Findings

The elements emphasised by the students are described through three categories, which reflect emotional, intellectual and practical qualities (Dewey, Citation1934, pp. 56–57) of their aesthetic learning processes. The categories are written with the aim of being illustrative and interpretive. The connection to Dewey’s perspectives is highlighted at the end of each category and shows how data and theory together create a base for my interpretation.

(1) Emotional quality – involving a drama

During the workshop, the students emphasise how senses and emotions play a substantial role in aesthetic learning processes. In a reflection note about the lecture on Monday, one student writes: ‘Aesthetic learning processes are processes in which students are given the opportunity to acquire knowledge through sensing. Whether it is to feel something, smell, hear, see, etc. […] Through the use of the whole body.’ The emphasis on senses and emotions is also expressed more indirectly, for example, through what the students highlight about their own experiences and how they act in the classroom. For instance, field notes from classroom observations on Monday describe smiles and laughter in the room while creating stories. Video recordings reveal bodily movements in rhythm with the music and eager typing on the PC keyboard. However, in an interview, a student describes the experience with storytelling more thoroughly and illuminates how the senses and imagination are put into play to create associations and emotional experiences:

As in the beginning, when there was a picture of stairs down to a basement, we did not know if it was down to a basement. … We were going to write about what sounds we heard and what we smelled? And then it was like that; I was in the middle of World War II right away [laughs]. It just came to me. I did not think; I just wrote. I read it afterwards, and thought, this was quite fun.

The ability to be active and to participate in the learning processes is also emphasised. For example, after the lecture on Monday, a student points at the opportunity to be active and participatory. The student does not pick any specific aesthetic quality of importance. Instead, he describes the aesthetic teaching methods as working methods that fit him well, although it is a new of way of thinking and talking about things. The student is laconic but conveys that he often feels uncomfortable, manifested by being passive in the lectures. If he is passive, he says that he feels like he is not part of what is happening in the classroom. This feeling therefore leads the student to experience the lecture on Monday as instructive and to arrive at this realisation: ‘It is important that I participate.’

In contrast to these mentioned characteristics, tensions and resistance are also evident. Some students express their dissatisfaction with the workshop. In the middle of the week, in an interview, a student emphasises that he prefers a greater extent of theoretical knowledge and that he has been very satisfied with another teacher educator, who always starts the lecture with a presentation of a theory. He says:

When I sat and wrote and worked at the workshop, it was no problem. But afterwards, I felt, ‘What am I really left with?’ When we got the assignment and should start answering it: What are aesthetic learning processes?

The other students in the group seem to agree, and one of them articulates this agreement. In another interview, two students also find the process stressful and challenging. For example, it has been difficult due to the many choices that have to be made. A student says that she and the class had never made anything like this before and gives the impression that the tasks have been unfamiliar to them. Considering this, the workshop also appears as a stressful experience but reveals the students’ high satisfaction with their own assignments and the workshop on Friday.

The students who are unsatisfied with the experience on Monday and miss the presentation of theories exemplify this matter, as they convey contrary aspects of how they feel about the workshop during the week. On Friday, they say that the learning processes have created a kind of action space with no ‘right or wrong’ answers and start to reflect on what kind of learning becomes memorable. The students tap into personal memories that depict their own experiences from their primary school years. This seems to be a turning point for them:

Student 1: For me, who likes to work practically, those are the things I remember, that is, the few times we worked like this in primary school. I still remember those things. I remember so concretely that we worked on the Middle Ages. We made a miniature village. I still remember it very well.

Student 2: I do, too, although I do not quite have the artistic abilities that you have. But I remember such things, too.

In sum, the students emphasise aesthetic learning processes through many emotional aspects, which indicate that they have enjoyed being involved in sensory, embodied, practical, participatory, memorable and open learning processes, on one hand, but have been unsatisfied, challenged and stressed through unfamiliar teaching methods, on the other hand. Relating these emotional tensions and contradictions to Dewey’s (Citation1934, p. 43) theoretical perspective shows that the students’ aesthetic learning processes seem to involve an emotional quality that can be understood as a kind of struggle, conflict or drama. According to Dewey (Citation1934, p. 43), these elements are all important parts of experiences and can even be enjoyed, although they may be painful. Dewey (Citation1934, pp. 42–44) states that intense aesthetic experiences are rarely wholly gleeful but can entail a kind of suffering and reconstruction, where emotions are significant contributors and become the moving and cementing force of the experiences. Therefore, the elements emphasised by the students portray an emotional quality of aesthetic learning processes, where they are active and present through their own and one another’s ‘emotional drama’.

(2) Intellectual quality – finding meaning

At the beginning of the lecture on Monday, the students’ reflection notes describe aesthetic learning processes as constituting a kind of variation in teaching. The students do not seem to emphasise any peculiar quality of the learning processes but refer to them as random features in a larger toolbox of teaching methods. Some students write that this variation is important for the pupils, due to the possibility of adapting the teaching to all students, as exemplified by this reflection note: ‘Aesthetic learning processes are about variation in teaching, where students at all levels manage to keep up with the class and get something out of the teaching.’

During the workshop, the abilities to create engagement and capture pupils’ attention through sensory, embodied and emotional experiences; facilitating learning based on the children’s own premises; communicating with pupils through multiple expressions; and adapting the teaching so that all pupils experience achievement are some of the elements highlighted in the students’ reflection notes and assignments and their comments during the interviews. One student becomes particularly engaged in this matter. At the beginning of the week, this student is quite centred on what the teacher educator said in the lecture. However, at the end of the week, she seems to have broadened her perspective, and her engagement appears to be more authentic. She states, ‘I have gained some insight into how important it is for the pupils […]. It is much more important than I thought about before we started.’ The student emphasises her realisation about the importance of making a difference and involving pupils through aesthetic learning processes. A few minutes later, she voluntary starts tapping into her personal story, as aesthetic learning processes have meant a great deal to her own school career:

At least, it had a very huge impact on me. I think this also counts for more people than me. Because if you do not like the school, it becomes somehow quite difficult to keep up with it as well. So, if you enjoy it and think it’s fun, then you concentrate more.

This and other quotes from the interviews illustrate how the students draw parallels to personal spheres and more clearly express their own experiences with learning. It thus seems that the topic becomes meaningful on personal and emotional levels.

Other statements from the reflection notes on Monday, such as ‘It is about learning through the use of the senses […], captures students’ attention by using the senses’, show several students’ emphasis on the connections between aesthetic practices and the ability to engage pupils and facilitate their achievements. For example, while working on the assignments, the students have to produce examples that move them closer to the identification of the aesthetic qualities of teaching and why these approaches may engage pupils. In one of the digital stories, two students show a project undertaken in a nearby school, where the pupils created a ‘friendship bridge’. Here, the students reflect on how the experience was manageable for all kinds of pupils, including the struggling ones. In this regard, they emphasise that the pupils ‘did not notice’ that the teachers integrated academic content into the various artful tasks that the pupils had to perform.

However, some students still have difficulties in explaining what creates such attention, engagement and achievement. In an interview on Monday, a student struggles to explain the value that these learning processes could have. However, he relates aesthetic learning processes to previous experiences in teacher education and to common topics, such as engagement and social relations. By doing this, the learning processes seem to create some kind of meaning for him:

No, I think it’s a great way to create engagement … for the pupils so that teaching could be a little more fun […]. Yes, it can be important for social relationships, so it has a value, I would say, in that way.

Altogether, the students seem to find meaning in how learning processes may engage pupils and how they, as future teachers, can contribute to achieving this aim. This emphasis can naturally be related to what the students have heard during the lecture. However, as they start to relate their own experiences from the workshop to their personal school experiences, previous experiences in teacher education, concrete examples of teaching methods in schools, and their prior knowledge of pedagogy, they seem to discover connections and find meaning on a deeper level. Theoretically, Dewey (Citation1934, pp. 46, 58) claims that when humans discover connections between experiences, such experiences acquire depth and breadth. This involves the interplay between doing something and undergoing something, connecting actions to consequences, and relating the present to past experiences. According to Dewey (Citation1934, p. 58), these connections may contribute to variety and movements, as well as counteract monotony and useless repetitions in human perceptions. In the arts, Dewey (Citation1934, pp. 50–51) addresses the point about the close relation between creating and at the same time perceiving. Such unity can explain how the student teachers find meaning in experiencing something authentically and aesthetically, for them to recognise how these experiences can be related to others. Therefore, the students’ areas of emphasis depict an intellectual quality of aesthetic learning processes, where they discover connections and find meaning.

(3) Practical quality – adaptation to interactions

During the lesson on Monday, the teacher educator shows examples of art projects and illustrates how to use arts and aesthetics in teaching. Simultaneously, the teacher educator reassures the students that they do not need to be particularly talented and skilful in the arts to facilitate aesthetic learning processes. For example, the video recording shows that while talking about creativity, the teacher educator says, ‘Creativity is a muscle that can be trained as anything else.’ Used as examples in the workshop, the art projects also support this idea, as they are both absurd and humorous and do not reflect perfection and beauty. This seems to be an element that is frequently referred to and may also reflect an important emphasis for the students. In the interviews, this point is articulated explicitly. However, it comes forth more indirectly from the whole group. In their reflection notes on Monday, for example, the students describe qualifications that are totally distinct from being artistic or a good aesthetician, which a teacher should possess to facilitate aesthetic learning processes. It is mentioned that the teacher must be able to foster an environment conducive to learning, communicate and interact with pupils, and be active, interested, creative and willing to take risks. Therefore, the students emphasise social competence and commitment as key qualities that a teacher should possess while facilitating aesthetic learning processes.

The students’ assignments also reveal their unfamiliarity with communicating through aesthetic expressions and forms. It means that the composition of music, pictures, colours, videos, storytelling, talking and layouts in the digital stories and podcasts show the students at the starting point in creating something aesthetically that will be used to communicate with an audience. Considering this and the students’ backgrounds (that reveal their ordinary experiences with arts and aesthetics), it seems comforting for them to hear that a teacher does not need to be talented or artistic to meet the curriculum’s expectations. This is articulated quite explicitly in an interview with a student, who reveals her lack of background in the arts:

Yes, personally, I have not been the best in arts and crafts and art and such. In general, I do not have that … . It’s not what I have liked the best. But that should not mean that I cannot use it. Because it’s like she says [referring to the teacher educator]; you do not have to be talented.

The preceding quote shows the student’s keen awareness of her limitation, but at the same time, it reveals that she has a contribution to make as a future teacher. Similarly, in one of the podcasts, two students interview a music teacher about how he thinks of and facilitates aesthetic learning processes. One of the elements brought forth in the podcast involves the challenges encountered in planning for this kind of learning. The students start to discuss aesthetic subjects and aesthetic expressions, such as drawing, painting and art, which they find exciting and difficult at the same time, as expressed by a student: ‘I think it’s very exciting, but when I think about it, I think it sounds a little difficult.’ However, the music teacher calms the students by explaining that this will come naturally after they have worked as teachers for some time. This sequence is subsequently cited by another group of students participating in one of the group interviews on Friday. They talk about how difficult they first thought it would be to teach this way, but the interview with the music teacher has made them more relieved, as expressed by a student:

We just thought, Help! Is it possible to do this in practice? It seems like you have to plan so much. But just like the music teacher said, he does not think anything special about it, until he does it, in a way. So, I think that when you are newly graduated, you have to plan a little bit more. But eventually, it may come naturally. I think that was a little funny to hear.

The music teacher’s statements somehow make aesthetic learning processes more achievable and less mysterious and difficult. This seems to alleviate the students’ worries about what aesthetic practices require from a teacher. These elements apparently equip the students with motivation, courage and the willingness to facilitate aesthetic learning processes in their future practice.

In general, it appears that the students need to explore how they can interact with their future surroundings as learning facilitators. Through Dewey’s (Citation1934, p. 57) lens, this adaptation can be viewed as mutual changes between the self and the aspects of the world or as an ‘act of abstraction’, where humans create their own experiences. Dewey (Citation1934, p. 56) claims that people extract what is significant for them, based on their own views and interests. Likewise, it can be assumed that the student teachers adapt the learning processes to their roles as future teachers, in accordance with their prior knowledge, skills, interests and views. This adaptation also shows that the lack of artistic skills is an issue for the student teachers and that the possibility to express themselves through arts and aesthetics may require more time and practice than the workshop offers. Therefore, the elements that are emphasised by the students show a practical quality of aesthetic learning processes, where an adaptation emerges between themselves and their future interactions with pupils.

Discussion

The elements emphasised by the student teachers show that they learn about and through aesthetic learning processes by being present through their own and each other’s emotional drama, by discovering connections between experiences with arts and aesthetics and finding meaning, and by being involved in a mutual adaptation that emerges between themselves and their future interactions with pupils. The students’ aesthetic learning processes can therefore be understood as those where they experience something as ‘learners’ in the classroom, for them to develop thoughts about pupils’ learning and their own practices as future teachers. For example, some emphasise that they miss theory and traditional lectures but later characterise aesthetic learning processes as memorable. Indirectly, it thus comes forth that they are in the process of developing and broadening their perspectives on teaching and learning through their own aesthetic experiences.

As mentioned, several international research studies illuminate this issue, that is, how students in generalist teacher education find arts-based and aesthetic approaches to teaching and learning challenging (Barnes & Shirley, Citation2007; Patterson, Citation2017; Selkrig & Bottrell, Citation2009). There are also researchers who shed light on the reasons for these prominent patterns, such as the fear of taking risks (Ogier & Ghosh, Citation2018) or discomfort about open-ended tasks (Barnes & Shirley, Citation2007). However, in this research study, the students’ challenges seem to be related to a kind of frustration or resistance (Dewey, Citation1934, p. 46), where their own perceptions of learning are challenged, developed and expanded through their own emotional experiences. In this sense, emotions become a moving force (Dewey, Citation1934, p. 44) in these students’ aesthetic learning processes.

While the student teachers start to reflect on these experiences, they also begin to change their own perceptions of learning. Alternatively, they discover connections and relations (Dewey, Citation1934, p. 46) between themselves as ‘learners’ and how these can work for ‘others’. Although the data show that the students generally emphasise these teaching methods as ways of interacting with pupils and creating engaging learning environments, it is primarily when they tap into personal memories, have flashbacks or relate to previous experiences in teacher education that these experiences grow in meaning. Research has illuminated similar aspects by explaining how teaching approaches that involve arts and aesthetics have the potential to connect to students’ personal spheres (Franklin & Johnson, Citation2010; Ogden et al., Citation2010; Oreck, Citation2004). In this study, it therefore seems that the students’ own aesthetic experiences from the past melt some of their resistance against the workshop and bring forth personal and emotional spheres that enable them to expand their perceptions.

Although the student teachers seem to relive some of their emotional tension during the workshop and eventually find meaning, the practical quality still portrays how they adapt to an aesthetic field that is unfamiliar to them (Dewey, Citation1934, p. 57). Previous research has also revealed that student teachers’ lack of arts experience can be an issue and can cause them not to feel confident enough to teach creatively and aesthetically (Barnes & Shirley, Citation2007; Ogier & Ghosh, Citation2018; Patterson, Citation2017). This research also substantiates the students’ worries about their own ability to facilitate pupils’ aesthetic learning processes. As a result, they seem to adapt these new experiences to their own possibility for achievement as a solution. However, student teachers are obviously not in a position where they can ‘change’ the premises for what kinds of knowledge and skills they should possess. It is enshrined in the curriculum that they should be able to facilitate aesthetic learning processes after their graduation (Ministry of Education and Research, Citation2016a). From another perspective, the students’ ways of adapting experiences, knowledge and skills about arts and aesthetics to their own possibilities to teach show that learning is not a mechanical process and that arts-based teaching cannot predetermine certain learning outcomes.

The outlined qualities cannot be separated in the real world but reveal close relations among emotions in learning, the meaning of personal connections in learning experiences and how the self takes advantage of them to adapt to and interact in specific situations. It remains that emotions become the moving and cementing force (Dewey, Citation1934, p. 44) in the students’ aesthetic learning processes and create spaces for new understandings. I refer to how the students’ emotional tension moves the learning experience forward but is simultaneously released through and in connection with their own personal and emotional spheres. I also allude to how emotional tension and emotional intentionality work in parallel in the learning experiences in order to adapt, situate and contextualise knowledge, skills and understandings. Although these emotional forces could be present in all kinds of learning processes, arts-based teaching seems to offer the students experiences where emotions have great potential to be activated. This is based on how the teaching methods that involve a variety of arts-based and aesthetic approaches facilitate an authentic, active and participatory use of the senses, bodies and imagination in learning (Dewey, Citation1934; Eisner, Citation2002; Greene, Citation1995).

Concluding remarks and implications

I have no foundation for making any kind of generalisation from this study (Stake, Citation2005, pp. 443–445), and the research has several limitations. For example, the students never had the opportunity to oppose, adjust or add elements and perspectives to my interpretation. Another research design, including more active involvement of the participants, could thus have strengthened the validity of the study’s findings and the ethical foundation. However, the case illustrates a useful example of student teachers’ professional development in arts-based teaching and learning. The example indicates that navigating away from artistic skills and focusing on arts and aesthetics as meaningful in learning seem to constitute a fruitful approach towards student teachers without prior knowledge of the arts. At the same time, it could be asked whether such an approach to aesthetic learning processes becomes too broad and reduces the expectations regarding the student teachers’ knowledge and skills to a minimum. If artistic skills and content are bypassed in teacher education, student teachers may end up losing the dimension in their teaching where the arts are integrated into their everyday classroom activities. It remains that arts and aesthetics are essential for children’s learning (Bresler & Thompson, Citation2002; Eisner, Citation2002; Wright, Citation2012), and this issue in teacher education will therefore need further elaboration. Perhaps generalist teacher education programmes, such as the one illustrated in this study, need a more equal balance between a pedagogical understanding of arts-based practices and some basic knowledge and skills regarding the arts.

Another risk that could inhibit student teachers’ professional development is related to how events, such as the above-discussed workshop, could end up as isolated experiences if they are not included in a systematic progression. For example, the way that the students in this study initially talk about aesthetic learning as a ‘variation in teaching methods’, rather than a legitimate form of teaching, could reinforce the point that an aesthetic learning process is understood as a supplement rather than an integrated way of thinking about teaching and learning. This study’s implication is therefore related to the importance of using arts-based approaches to teaching and learning across disciplines to educate future teachers and equip them with sufficient knowledge, skills and meaningful learning experiences that could change their perceptions of learning.

In this study, I have tried to create a bridge between the national and the international research fields by highlighting aesthetic learning processes in the context of arts-based teaching and learning (Møller-Skau & Lindstøl, Citation2022; Ogden et al., Citation2010; Oreck, Citation2004), which is one of many umbrella concepts in this genre. The reason for drawing this connection is to join the international debate about how to promote creativity, critical thinking and diversity in general education. To conclude, I argue that arts-based teaching and learning contribute to future teachers’ ability to meet the requirements of education in the twenty-first century, as this could expand a teacher’s didactic and pedagogical repertoire to facilitate building creative, collaborative, diverse and inclusive learning environments and meet pupils’ need for artful, playful and meaningful learning.

Acknowledgments

I extend my thanks to my supervisors, colleagues, reviewers, editors and my family. I appreciate their support, help and insights on multiple topics and challenges. I am grateful to the University of South-Eastern Norway for funding my research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bamford, A. (2006). The wow factor – global research compendium on the impact of the arts in education. Waxmann Verlag.

- Barnes, J., & Shirley, I. (2007). Strangely familiar: Cross-curricular and creative thinking in teacher education. Improving Schools, 10(2), 162–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480207078580

- Bhukhanwala, F., Dean, K., & Troyer, M. (2017). Beyond the student teaching seminar: Examining transformative learning through arts-based approaches. Teachers & Teaching Theory & Practice, 23(5), 611–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1219712

- Brekke, B., & Willbergh, I. (2017). Frihet, fantasi og utfoldelse. En kvalitativ studie av estetiske arbeidsformer i lærerutdanningene. [Freedom, imagination and expression. A qualitative study of aesthetic teaching methods in teacher education]. Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk og kritikk, 3(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.23865/ntpk.v3.554

- Bresler, L., & Thompson, C. M. (2002). Context Interlude. In L. Bresler & C. M. Thompson (Eds.), The arts in children’s lives context, culture, and curriculum (pp. 9–13). Springer Link.

- Burnard, P., Holliday, C., Jasilek, S., & Nikolova, A. (2015). Artists and higher education partnerships: A living enquiry. Education Journal, 4(3), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.edu.20150403.12

- By, I.-Å., Holthe, A., Lie, C., Sandven, J., Vestad, I. L., & Birkeland, I. (2020). Estetiske læringsprosesser i grunnskolelærerutdanningene; Helhetlig, integrert og forskingsbasert? [Aesthetic learning processes in teacher education; Holistic, integrated and research based?] (Report to the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, 24. June 2020). https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/ea18f23415a14c8faaf7bc869022afc2/estetiske-laringsprosesser-i-grunnskolelarerutdanningene.pdf

- Chappell, S. V., & Chappell, D. (2016). Building social inclusion through critical arts-based pedagogies in university classroom communities. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(3), 292–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1047658

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

- Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

- Eisner, E. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. Yale University Press.

- Fleming, M. (2011). Learning in and through the arts. In J. Sefton-Green, P. Thomson, K. Jones, & L. Bresler (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of creative learning (pp. 177–185). Routledge.

- Franklin, C., & Johnson, G. (2010). Disrupting the taken for granted: Exploring urban teacher candidate experiences in aesthetic education. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 5(2), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2010.02.001

- Giorza, T. (2016). Thinking together through pictures: The community of philosophical enquiry and visual analysis in transformative pedagogy. Perspectives in Education, 34(1), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v34i1.12

- Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Hall, C., & Thomson, P. (2007). Creative partnerships? Cultural policy and inclusive arts practice in one primary school. British Educational Research Journal, 33(3), 315–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701243586

- Harris, D. X., & Lemon, A. (2012). Bodies that shatter: Creativity, culture and the new pedagogical imaginary. Pedagogy Culture & Society, 20(3), 413–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2012.712054

- Jones, S., & Hall, C. (2009). Creative partners: Arts practice and the potential for pupil voice. Power & Education, 1(2), 178–188. https://doi.org/10.2304/power.2009.1.2.178

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2015). Det kvalitative forskningsintervju [the qualitative research interview] (3rd ed. ; T. M. Anderssen & J. Rygge Trans.). Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2016a). Forskrift om rammeplan for grunnskolelærerutdanning for trinn 1–7 [Regulation on the curriculum of teacher education, school levels 1–7]. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2016-06-07-860

- Ministry of Education and Research. (2016b). Forskrift om rammeplan for grunnskolelærerutdanning for trinn 5–10 [Regulation on the curriculum of teacher education, school levels 5–10]. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2016-06-07-861

- Møller-Skau, M., & Lindstøl, F. (2022). Arts-based teaching and learning in teacher education: “crystallising” student teachers’ learning outcomes through a systematic literature review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 109, 103545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103545

- National Council for Teacher Education. (2018a). Nasjonale retningslinjer for grunnskolelærerutdanningen, trinn 1–7 [National guidelines for teacher education, school levels 1–7]. https://www.uhr.no/_f/p1/ibda59a76-750c-43f2-b95a-a7690820ccf4/revidert-171018-nasjonale-retningslinjer-for-grunnskolelarerutdanning-trinn-1-7_fin.pdf

- National Council for Teacher Education. (2018b). Nasjonale retningslinjer for grunnskolelærerutdanningen, trinn 5–10 [National guidelines for teacher education, school levels 5–10]. https://www.uhr.no/_f/p1/iffeaf9b9-6786-45f5-8f31-e384b45195e4/revidert-171018-nasjonale-retningslinjer-for-grunnskoleutdanning-trinn-5-10_fin.pdf

- Nilson, C., Fetherston, C. M., McMurray, A., & Fetherston, T. (2013). Creative arts: An essential element in the teacher’s toolkit when developing critical thinking in children. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(7). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2013v38n7.4.

- Ogden, H., DeLuca, C., & Searle, M. (2010). Authentic arts‐based learning in teacher education: A musical theatre experience. Teaching Education, 21(4), 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2010.495770

- Ogier, S., & Ghosh, K. (2018). Exploring student teachers’ capacity for creativity through the interdisciplinary use of comics in the primary classroom. Journal of Graphic Novels & Comics, 9(4), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2017.1319871

- Oreck, B. (2004). The artistic and professional development of teachers. A study of teachers` attitudes towards and use of the arts in teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 55(1), 55–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487103260072

- Patterson, J. A. (2017). Too important to quit: A call for teacher support of art. The Educational Forum, 81(3), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2017.1314568

- Pool, J., Dittrich, C., & Pool, K. (2011). Arts integration in teacher preparation: Teaching the teachers. Journal for Learning through the Arts, 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.21977/D97110004

- Selkrig, M., & Bottrell, C. (2009). Transformative learning for pre-service teachers: When too much art education is barely enough! The International Journal of Learning, 16(1), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v16i01/46103

- Selkrig, M., & Bottrell, C. (2018). Exploring particular creativities in the arts through the voices of Australian visual arts educators. In L. de Bruin, P. Burnard, & S. Davies (Eds.), Creativities in arts education, research and practice (pp. 15–32). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004369603_002

- Shockley, E. T., & Krakaur, L. (2021). Arts at the core: Considerations of cultural competence for secondary pre-service teachers in the age of common core and the every student succeeds act. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 16(1), 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2020.1738936

- Stake, R. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 443–466). Sage Publications.

- Watson, J. (2018). Deferred creativity: Exploring the impact of an undergraduate learning experience on professional practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 71, 206–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.12.018

- Wright, S. (2012). Ways of knowing in the arts. In S. Wright (Ed.), Children, meaning-making and the arts (2nd ed., pp. 1–29). Pearson.