?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This article looks at the relationship of digital religious communication to “social resilience” or “community resilience.” The importance of, in particular, narratival communication of meaning for group resilience has been highlighted by Houston et al. (Citation2015b). Religious narratives as reflected communication of meaning are recognized to have quantified themselves in communities’ digital communications, thereby rendering themselves accessible to empirical assessment. From this perspective, we present a model for measuring community resilience quantitatively. Existing resilience models from research on ecological, mechanical, and community resilience were combined via their shared resilience trajectories to design the model. To further facilitate the empirical application of the model, we provide a conceptualization of digital religious communication and its viability as an effective indicator of community resilience. One significant advancement of this focus on digital communications and community resilience assessment consists in the qualities characterizing such communications as both communicators’ own self-prompted communications while also being quantifiable. This enables reconstruction and analysis of a more organic communication environment than that made accessible in survey-based approaches while also capable of achieving a higher level of representativity than ethnographic or case study approaches.

1. Occasion, goal and organization of the studyFootnote1

The COVID-19 virus pandemic has been affecting the global community for over two years now (WHO, Citation2021). Given the extreme stress that individuals, groups, and social systems have been under, it is not surprising that the concept of “resilience” – associated with “hope for crisis resistance, stability, inner strength and a calm well-being” (Richter & Blank, Citation2016b, p. 67) – has become a topic of both popular and scientific interest.

While acknowledging the dire effects of the pandemic, it simultaneously provided a unique research opportunity as an exemplary crisis challenging the resilience of social systems globally. In our own field of research – namely, religious somatizations of the social and vice versa – we became interested in the potential significance of religious narrations of the pandemic on social media for the resilience of organizations with a religious profile. We designed a study focusing on Twitter that looked at the communication about the pandemic of 126 Christian ecumenical and diaconic organizations worldwide, focusing particularly on their use (or lack of use) of religious language to do so. In the process of developing this study, we recognized the need for a model of social resilience that would enable quantitative, empirical assessment of resilience and that could operationalize communication as an indicator of organizational and community resilience. The tremendous quantity of digital data artifacts generated daily in today’s digitalized society, we hypothesized, might reveal insights into how future crises comparable to the current one could be navigated resiliently. Therefore, we prioritized developing a model for social resilience suitable for quantitative empirical research utilizing digital communication artifacts.

The present article, then, is Part 1 of a two-part project and presents the theoretical model just referred to. A second article, Part 2, is being published in a subsequent issue of this same journal and reports on the development, implementation, and findings of the research on the tweets of those Christian ecumenical and diaconic organizations.

In the course of developing that model for analyzing Tweets of religious organizations, we realized that it could be deployed just the same in research on various social (sub)systems and societal discourses. This article thus presents the model as a general model for quantitative analysis of the cultivation of shared meaning via communication during crisis on social media, drawing on various theories and models for reconstructing the interrelationship of these dynamics with one another. In illustration of the model, this article focuses on the significance of communication for the resilience of religious organizations and on the interrelation of resilience and religion. (Richter & Geiser, Citation2021, p. 9) We introduce the terminology of “digital religious communication” as an instance of “reflected religious communication” (M. R. Robinson, Citation2020) to define the field and call for further research on social resilience in this promising field.

2. Motivation and orientation: religious self-understandings, social objects, and information

The theoretical model introduced in the body of this paper formed in the course of addressing the question of how to theorize the changing relationships between the self-understandings of individuals and groups, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the ways these self-understandings are communicated. Now, this already can be understood as a “theological” task, in the sense articulated by Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834). Specifically, Schleiermacher outlined an understanding of systematic-theological research as the organized presentation of the self-understandings prevailing within a particular (Christian) group in a particular place and at a particular time. (Schleiermacher, Citation2011, p. 41) In order to access, formulate, and present these, however, additional questions must be considered: There are the questions of what media carry those communications, and how these can be approached in an organized and systematic manner, specifically, in ways that can rigorously assess – perhaps even measure – the significance of those communications in terms of their impact on the various functionings of particular social groups. In short, an interest in “theology” – reflected religious communication – as a form of social communication stimulated the project.

Work in the philosophy of language and social theory over the past one hundred years has generated numerous possible theorizations: Theology might be understood in a Marxian framework as “ideology”; or as a kind “symbolic” communication in the style of the philosophy of symbolic forms of Cassirer, and more narrowly, as a “cultural symbol” with Geertz; or perhaps as a form of social action following Parsons, whether in Austin’s framework as a speech act or in terms of Habermas’s philosophy of communicative action; or again, theology might be regarded, following Blumenberg, as “metaphor” for living or as creating what Anderson and Taylor in their separate ways call “social imaginaries”; still further possibilities include theorizing theology as a social “discourse” in a Foucauldian sense or as negotiating a kind of social “scape” in the sense in which Appadurai uses that terminology. All these philosophical-theoretical framings for plotting reflected religious communications are thinkable and probably many other others still besides. But none of them quite build a constructive empirical bridge between the lived communities and those communities’ self-understandings.

The new realist philosopher Maurizio Ferraris (Ferraris, Citation2013), in combination with the sociological theory of Niklas Luhmann (cf., among others, Luhmann, Citation1995), can help to address just this challenge. Ferraris’s theory of “documentality” offers a way of understanding social ideas as present and, in a way, textualized in what Ferraris calls “social objects”. Social objects include things like “money, roles, and institutions” (Ferraris, Citation2013, p. 120) and do not exist in the same way the natural objects, including things like mountains or animals, exist. But social objects do exist, and, indeed, often take on material, preservable, reproducible, and measurable forms of expression with characteristics that can be comparatively assessed alongside other similar forms. Ferraris proposes, moreover, to recognize in social objects “inscriptions”, arguing for a “weak textualism” that “assumes that inscriptions are decisive in the construction of social reality.” (Ferraris, Citation2013, p. 121) These points, we would like to suggest, to the communicative nature of society generally, and in this way, to the sociological systems-theory of Niklas Luhmann. Luhmann famously advanced the thesis that society is communication. The idea (and here we ourselves are making the combination of Ferraris’s terminology with that of Luhmann) is that to say inscription constructs social reality implies what Luhmann calls the “multiple constitution” of that reality. (Luhmann, Citation1995, p. 39) Unpacking the idea of “multiple constitution”, Luhmann observes that at least two elements are implied as well as something passing between them that can create an at least temporary unity in the presence of difference, which unity makes a new difference for both original elements even while preserving them. Society forms in, by means of, and indeed, as communication. For the purposes of the present study, the most practical specification that this theory offers is the identification that that which mediates existing difference and creates new difference can be referred to with the term “information”. Even though “information” in this usage is to be understood metaphorically, to a certain extent, it directs our attention to the actual encodings of information that convey or “media”- interactions among particular elements, namely, data. Even data in as simplified a form as 1s and 0s.

With this, then, we have an implementable theory for creating the empirical bridge between a lived community and its self-understandings that can enable us to document and, on scale, measure the significance of those self-understandings, as well as of their being communicated, for the group itself à la the question: “What does theological information do for the communities in which it circulates?” This question could be used then to identify any number of instances of theological information as possible inscriptions that can be assessed qualitatively and quantitatively. Most importantly, it breaks the concept and terminology of “theology” free from its more traditional media and directs the attention toward all kinds of mass communications. In our case, these ideas enabled us to realize that digital religious communications are social objects that inscribe social reality in data that can be quantitatively presented.

The model presented below is thus generated out of an interest in the possible relevance of religious and theological information for community and societal resilience. As noted in the introduction, the model is applicable not only to religious and theological information but could also be applied to any meaningful grouping or categorization of social discourses. Given that theological self-understandings tend to be highly subjective, however, this model could prove particularly useful for understanding religious and theological information in relation to resilience, provided large enough data sets can be gathered.

3. Theoretical foundations

3.1. “Social resilience” as a research area: review of recent literature

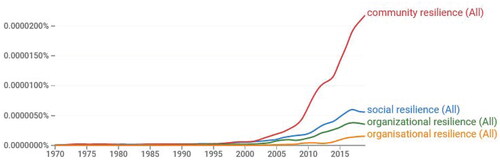

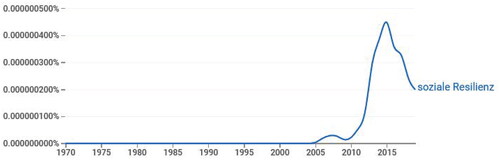

If, as Luhmann argued, society is communication (Luhmann, Citation1995), then to an increasing extent it might be said that society today is digital communication. From this perspective, we aim to assess the resilience not of individual persons nor of groups of persons per se except insofar as these organize and present themselves as communication and exist via their participation in the digital communication system of social media platforms. In the English-language scholarly literature, research on the resilience of groups is treated primarily using the terminology of “community resilience”, “social resilience”, and “organizational/organizational resilience.”Footnote2 Similar to resilience research in general, this discursive domain has shown immense growth since the dawn of the new millennium (see ). Comparatively less research has been conducted on resilience in relation to the social in German-language resilience research (being our second most proximate context for comparison). In the latter, all of the mentioned English terms are subsumed under the term “soziale Resilienz” (Endreß & Maurer, Citation2015a, p. 7) (see ).Footnote3

Figure 1. “Google Books N-gram Viewer” of the English corpus for the terms “social resilience, community resilience, organizational resilience, organizational resilience” (Case-Insensitive with Smoothing of 1) in the period from 1970 to 2019.

Figure 2. “Google Books N-gram Viewer” of the German corpus for the term “soziale Resilienz” (Case-Insensitive with Smoothing of 1) in the period from 1970 to 2019.

Due to the large number of research areas that work on the topic (Koliou et al., Citation2018, p. 14) as well as to the divergent objectives in individual studies (Koliou et al., Citation2018, p. 15), no single definition of social or community resilience has so far been agreed upon across all disciplines. Nevertheless, some common features in understandings of the terms can be identified. Koliou et al. (Citation2018) have recently noted these with respect to English-language research. Endreß and Maurer (Citation2015c) have done the same for German-language research.Footnote4

A distinction can be made between “natural science-oriented and material science-oriented” definitions of social resilience and “social science-oriented” definitions (Bonß, Citation2015, p. 16). Building on this distinction, the following definitions and models (sections 2.1.1 and 2.1.2) can be summarized and integrated into a theory enabling an empirical quantitative assessment of social resilience (section 2.2).

3.1.1. Natural-scientific perspectives on social resilience

Research in the natural sciences on social resilience largely follows the tradition of Holling (1973). Holling is acknowledged to have been “one of the first researchers to define resilience as the ability of ecological systems to absorb and bounce back from external shocks” (Koliou et al., Citation2018, p. 3). Models of resilience developed in keeping with this focus seek to allow an empirical-quantitative determination of the resilience of material objects (Koliou et al., Citation2018, pp. 6–14).

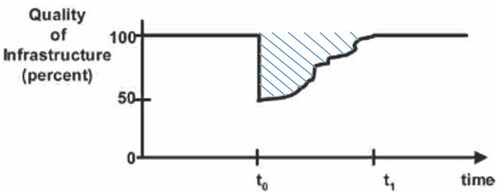

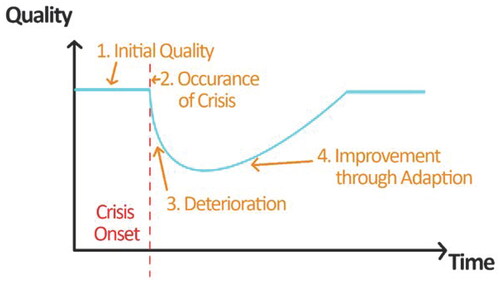

In particular, the mathematical model developed by Bruneau et. al. (2003, p. 737)Footnote5 may be highlighted. They modeled the loss of resilience of a system of quality

at the time when a crisis occurs, where

is defined as:

Here, the original quality Q of the system is normalized to 100 and the crisis occurs at time . In , the loss of resilience corresponds to the area above the curve between times

and

:

Figure 3. Development of an idealized infrastructure system’s quality when a crisis occurs at time

and the pre-crisis level is fully restored by time

(Bruneau et al., Citation2003, p. 737). The area shaded-in (by Fröh/Robinson) corresponds to the loss of resilience.

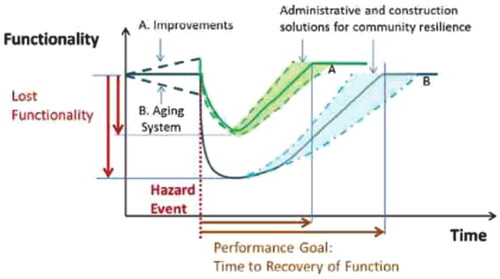

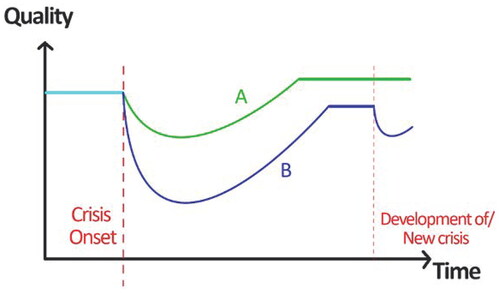

The resilience model proposed by McAllister in 2016 bears a strong resemblance to this model. McAllister depicts two different functional curves for infrastructure systems when a crisis occurs (see ). He defines resilience as “time to recovery of functionality” (McAllister, Citation2016, p. 1). The time to recovery, however, is directly related to the integral of the functionality curve. McAllister’s and Bruneau et al.’s definitions can thus be seen as similar in this respect.

Figure 4. McAllister’s resilience model depicting two different trajectories of an infrastructure system’s functionality over the course of a crisis (McAllister, Citation2016, p. 2).

3.1.2. Social-scientific perspectives on social resilience

Like natural-scientific models, social-scientific models also largely follow the Holling tradition (Koliou et al., Citation2018, p. 3). However, they tend to focus less on the quantifiability of the phenomenon than on a qualitative understanding of social resilience and its factors. The several, quite divergent models in this grouping have at least three features in common with natural-scientific understandings of resilience:

In social-scientific approaches, social resilience is studied in the context of a crisis and its management.Footnote6 Focused attention is given to the system’s response and the evolution of relationships within the system in the face of a stressor or shock (Koliou et al., Citation2018, p. 14).

Social resilience itself is understood by many researchers as an “adaptive capacity” (Becker et al., Citation2013, p. 5).Footnote7 This is determined by how effectively the social system uses its “individual, collective and institutional resources” to cope with crises (Paton, Citation2007, p. 6).

A special property of social resilience is the way in which it exhibits qualities of “emergent” phenomena. Analogously to Aristotle’s famous discussion of the way a whole is often to be seen as something more than the combination of its parts (Aristotle, Citation1989, 1041b), so also with community resilience. In this vein, the following hypothesis can serve as a point of departure for experimentation and analysis: “[A] resilient community is not simply a grouping of resilient individuals or organizations, but is a collection of people and groups who are able to interact successfully to facilitate adaptation of the whole” (Houston, Citation2018, p. 19).Footnote8

Depending on the research perspectives selected and the objectives identified, a distinct focus is usually set in addition to the three commonalities just noted. According to Koliou et al., these can be divided into three different lines of research, which are briefly outlined below.Footnote9

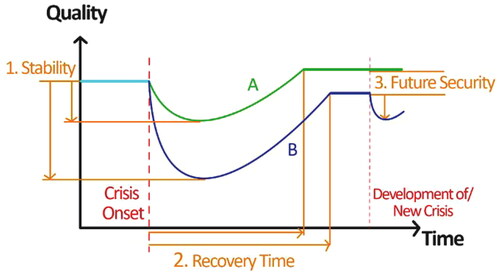

The first line of development is summarized under the phrase “reducing impacts or consequences” (Koliou et al., Citation2018, p. 4). This perspective, which is mainly used in German-language resilience research by Endreß and Maurer (Citation2015b, p. 7) and Bonß (Citation2015, p. 18), focuses on the resilience of a social system at the moment of the onset of a crisis. Such approaches tend to be interested in the “stability” of the system.

A second line of development bears a certain similarity to McAllister’s natural-scientific understanding of resilience. In keeping with the metaphor of “bouncing back” already used by Holling in 1973, the immediate impact of the crisis can be seen as less crucial, and the focus can be placed instead on the ability of the system to recover as quickly as possible from the consequences of the crisis. The “recovery time” of the system thus becomes the yardstick for resilience.

In the wake of the World Conference on Disaster Reduction in 2005, a third line of development emerged. Researchers here refer not only to “bouncing back” but to “bouncing forward” (Manyena et al., Citation2011, p. 418).Footnote10 It other words it is not only a system’s recovery that is taken to indicate resilience, but indications of “reducing future vulnerabilities” (Koliou et al., Citation2018, p. 4) are also important. For these perspectives of social resilience, “future security” gains relevance.

3.2. Toward a quantifiable model for social resilience

The quantitative investigation of “digital religious communication” requires us to apply a quantifiable model of social resilience to it. However, since research on social resilience has not yet identified a sufficiently quantifiable model of resilience (Koliou et al., Citation2018, p. 20), we have combined social-scientific understandings of the term as summarized above with insights drawn from the natural-scientific models described above. This was done on the hypothesis that an integration of quantitative methodologies might be possible at those points where there are fundamental agreements between the social- and natural-scientific understandings of resilience, such as, e.g., dependence on time sequences and the quantifiability of the social objects being analyzed.

More specifically, we noted at least four common features of social-scientific resilience research presented in section 2.1.2 that can be layered with fundamental aspects of natural-scientific, mathematical models discussed in section 2.1.1. The following points of overlap can be identified as necessary conditions for describing social resilience:

An initial “quality” of the system under investigation is assumed. While this is explicitly identified and quantified from a natural-scientific perspective, it is more implicitly assumed by social-scientific models.

The development of this quality from the moment of the onset of a crisis situation is considered relevant for analysis of social resilience.

The social system experiences a deterioration of its quality as a result of the crisis,Footnote11 to which the system reacts by generating adaptations.

The adaptation of the system aims at prevention of system failure and achievement of improvements in the crisis condition.

The above-mentioned similarities between the natural-scientific and social-scientific perspectives all relate to the development of that quality of a system to which the analysis of resilience refers. We offer a first, model-like visualization of the evolution of a social-system’s condition or status ad terminum that fulfills all of these necessary conditions in .

Figure 5. Development of a social system’s quality with the four necessary conditions resulting from the overlapping natural- and social-scientific perspectives on resilience identified in the literature.

A second observation drawn from the above review of natural- and social-scientific models now becomes particularly significant: All three of the social-scientific research emphases noted above correlate with the mathematical determination of the resilience value.

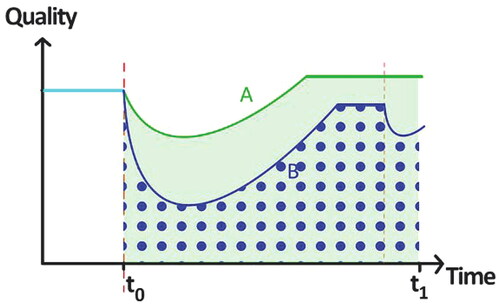

The point can be illustrated by two exemplary developments, A and B, of the quality of a social system (see ). The evolution of both systems starts at a normalized initial value. A deterioration of the systems follows the beginning of the crisis, leading to phases of recovery, adaptation and further development of the system in due course. In , we additionally visualize the possibility of a worsening of the crisis at a later point in time or the occurrence of a second, related crisis. Here, the quality of system A is stable, while system B again shows a slight deterioration.

Figure 6. Two developments, A and B, of a social system’s quality from the occurrence of a crisis until shortly after the further development of this crisis or until shortly after the occurrence of a related crisis.

From a social-scientific qualitative perspective, different aspects may be decisive for analysis of the resilience of a social system as reflected by the two evolutions, A and B, of the system depending on which focus is taken. As explained in section 2.1.2, potential points of focus include the greatest possible “stability” at the moment of the crisis, the shortest possible “recovery time” for the quality and “future security” in the event of a renewed crisis or a worsening of the current crisis. In the hypothetical case considered here, crisis course A would be more resilient than crisis course B according to each of the criteria mentioned (see ).

Figure 7. Illustration of the three social-scientific development lines “stability“, “recovery time” and “future security” based on two developments of a system’s quality .

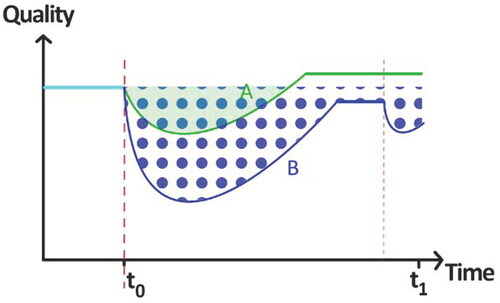

In natural-scientific, quantitative approaches to the study of resilience, it is not so much any given status ad terminum in the course of development that is relevant for the assessment of the system’s resilience, but rather the difference of the integral over the entire period from its initial status ad quem (Bruneau et al., Citation2003, p. 737). This means, as noted in section 2.1.1, that the area above the curve of the line showing the system’s development starting at the point of the onset of the crisis can be seen as marking the quantitative value for the loss of resilience. Therefore, development A of the systems is rated as more resilient than development B since the respective loss of resilience is smaller (see ).

Figure 8. Plot of the resilience integrals’ areas according to Bruneau et al. based on two developments of a system’s quality (green filled: A; blue dotted: B).

Both, social-scientific and natural-scientific perspectives, reach the same conclusion concerning which line of system development is the more resilient one, namely, A. This illustrates how the two perspectives can be seen to converge: both can be described as focused on determining the integral of over the crisis period. This integral now quantifies not the loss of resilience but a value for the system’s resilience itself. Therefore, a system’s resilience is indicated by the area below the line marking the development of quality

(see ).

Figure 9. Combined model of social resilience of the developments A and B, with the areas of the resilience integrals marked (green filled: A; blue dotted: B).

Such an integral can serve as a characteristic value for social resilience if the course of the system quality (t) in question fulfills the four necessary conditions described above (i.e., starting stability, crisis, deterioration, improvement). Social resilience may thus be described as a quantitative resilience value

, determined via quantification of a social system’s experience of a moment of crisis (Koliou et al., Citation2018, p. 14) and its use of individual, collective and institutional capacities (Paton, Citation2007, p. 7) to respond adaptively (Becker et al., Citation2013, p. 5) to the crisis. Here, the resilience value

is defined as:

where

corresponds to the evolution of the system’s quality over the period t ∈ [t0,t1]. A visualization of the combined model of social resilience is presented in .

The time-series function is decisive for the determination of the resilience value

. The particular “quality” whose evolution is to be followed includes any aspect of a social system of interest in social-scientific frameworks for resilience research. The challenge is that, for the determination of resilience, the aspects chosen have to be quantified, such that a framework with

aspects produces functions

with

which form the basis of the quality function

in the form:

Here, the integral form of the definition of resilience allows for both an individual consideration of particular aspects and a summary consideration of the resilience value as a whole (Grieser, Citation2015, p. 295):

This model could be applied to analysis of the quality of resilience of any social object that can be rendered quantifiable. It is not limited to the specific application discussed below. In the following section, we will now describe digital religious communication as a social object and define the way in which it can be quantified as a quality of a social system whose resilience might be analyzed.

4. “Digital religious communication” as an object of research

As described in the previous section, a framework is needed by which “digital religious communication” can be divided into a quantifiable domain of objects and graphed by the functions Qi(t) modeling their quality over time.

In this section, first, we explain our choice of a resilience framework (see 3.1 and 3.2). While there are many definitions and models of social resilience, we chose the framework used here to establish the link between the topic “social resilience” and the research object “communication”. Second, we describe specific dimensions of the framework, leading to our narrower focus on “digital” (section 3.3) “religious” (section 3.4) communication.

4.1. The choice of a theoretical framework for analyzing social resilience

Crystal Daugherty has recently observed that “[R]esilience requires communication” (Citation2021, p. 296). This is a point which has found broad agreement among researchers on social resilience. Starting with Paton et al. in Citation2008, who included “satisfaction with communication” (2008, p. 53) in their definition of resilience, communication has consistently been identified as a core feature of the resilience of groups (Houston et al. Citation2015b, 271; Houston et al. Citation2015a, 1; Longstaff and Yang Citation2008, 1; Houston Citation2018, 19; Pfefferbaum et al. Citation2015, 182; Houston et al. Citation2017, 355; Cummings et al. Citation2021, 89). Nevertheless, the phenomenon of “social resilience” has not received significant attention in the fields of linguistics and media studies (Houston et al. Citation2015b, 272).

One important exception to this is a study published in 2015 by Houston et al. (Citation2015). The authors examine previously published resilience frameworks in relation to three different communication-theory perspectives, namely, communication ecology, public relations and strategic communication. They then relate the common elements of resilience frameworks to these approaches in communication-theory to create a resilience framework that focuses on communication as the ether in and through and as which resilience dynamics develop (Houston et al. Citation2015b, 273).

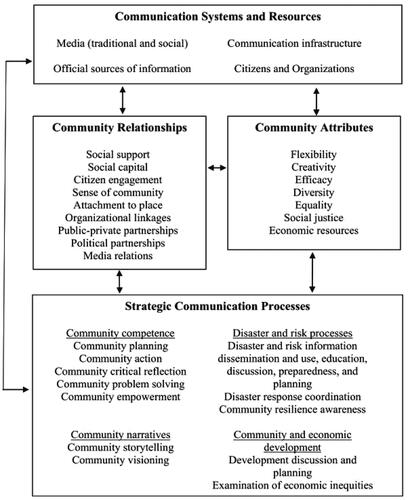

In terms of content, the framework developed by Houston et al. consists of a total of four different dimensions (see ), in which the connections between the research object “communication” and the primary research focus “social resilience” are outlined.

Figure 10. Communication-centered resilience framework from Houston et al (Houston, Spialek et al., Citation2015, p. 274).

The first of the four dimensions, referred to as “Communication Systems and Resources” (Houston, Spialek et al., Citation2015, p. 275), “represent[s] the reservoirs in which community meaning-making, information exchange, interactions, and connections can occur” (Houston, Spialek et al., Citation2015, p. 275). Our work has been focused on the social media platform “Twitter” thus far as a system of communication (Ang, Citation2021). Therefore, the “resources” to be analyzed in our research include the “communication infrastructure” provided by Twitter for private users as well as for companies and official bodies.

The second dimension refers to the relationships that are relevant for social resilience, using the term “Community Relationships”. These relationships can be a loose connection, a passive group affiliation or an actively designed interaction between normal users, companies and official bodies (Houston, Spialek et al., Citation2015, p. 275). All of these are prevalent on Twitter and other social media platforms where they are maintained by free-flowing individual, group and organizational interactions (Pfaffenberg, Citation2015, p. 26).

The third dimension, “community attributes” (Houston, Spialek et al., Citation2015, p. 277), is not discussed in detail by Houston et al. The relevance to social resilience, however, is clear and as such the category invites further investigation. Community attributes, such as “flexibility”, “diversity,” or “social justice”, “represent the “characteristics” of the communicating group - the more these attributes characterize a group, the more it can be said to demonstrate resilience.

The fourth dimension concerns the content of the communication itself. Houston et al. distinguish between four “Strategic Communication Processes” (2015, p. 276), all of which contribute to the resilience of groups during a crisis. These processes range from (i) factual stocktaking and (ii) information sharing, to (iii) collaboratively shaping (identifying and characterizing) the crisis, to (iv) making sense of the circumstances experienced. Once again, as communication services on which all four of these forms of strategic communication are taking place and in reciprocal ways, Twitter and other social media platforms constitutes a fertile field for further research on this fourth dimension of resilience (Pfaffenberg, Citation2015).

All four dimensions in the framework of Houston et al. unfold in interdependent relationships with one another (2015, p. 277). Of particular interest for our research is the possibility that this interdependence can, in principle, be modeled by quantifying various resilience relevant aspects of the communication system and their functioning over time, expressed by the functions Qi(t). Of course, not all communicative actions on social media would seem equally relevant as social resilience factors; for example, Daugherty identifies not simply communication itself as relevant to resilience, but more specifically effective communication (Daugherty Citation2021, p. 296). Thus, certain delimitations of scope are necessary. Two of them will be suggested in the following section, leading to a concretization of the framework.

4.2. Concretization of the framework

As early as 2008, Paton et al. showed that effective communication of information in crisis situations does not primarily depend on the quality of the content of this information (2008, p. 46). Rather, and with regard to the context of a pandemic in particular, the literature identifies two factors in particular as characteristic of effective communication: Trustworthiness of source and impact on meaning-making.

A disease pandemic is always accompanied by an information pandemic in communication about that disease (Ding & Tang, Citation2021, p. 33). In the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) coined the term “infodemic” to refer to this dynamic, which it defined as “too much information including false or misleading information in digital and physical environments during a disease outbreak” (WHO, Citation2021). In this light, it is unsurprising that the effectiveness of the information communicated depends on “trust” in the information source (Longstaff & Yang, Citation2008, p. 1; Paton et al., Citation2008, pp. 51–52; Pfefferbaum et al., Citation2015, p. 193). Trustworthy sources of information are identified as those communicators in a person’s environment with whom a relationship of trust already existed before the pandemic (Wise, Citation2021, p. 19) and who are perceived as holding the same values as the information recipient (Paton et al., Citation2008, p. 47). Therefore, we decided to focus our analyses first on communications that originated from sources likely to be regarded as trustworthy in these respects by the field of potential communication recipients.

Regarding the “impact” of communications on the meaning-making processes of information recipients, the contextual and referential nature of all information acquisition and interpretation must be considered. As with trustworthiness, impact will filter through previous experience and preexisting basic convictions. This is no less true during crises like the pandemic than in any other crisis, as “people attempt to understand a novel pandemic by relying on their existing mental models” (Tallapragada, Citation2021, pp. 75–76). Such examples of such basic convictions might include “unreasonable optimism, mortality salience, and identity protection cognition” (Tallapragada, Citation2021, p. 77) as well as certain kinds of “outcome expectancy” and “self-efficacy” (Paton, Citation2003, p. 214; Paton et al., Citation2005, p. 27).Footnote12 Thus, the part of communication that has a direct influence on these convictions is of particular relevance for resilience assessment. It is not clear that more objective forms of communication during and about the pandemic (e.g., reporting of scientific findings) have the biggest impact on meaning-making for groups. Indeed, precisely in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was surrounded by many protest and populist movements contesting scientific research about the pandemic, “unreasonable optimism,” “identity protection,” “mortality salient” communication became key sites for the study of the impact of communications on group meaning-making.

For our work, then, it follows that the area of “community narratives” in Houston’s framework has been of particular interest. Specifically, we became interested in the resilience relevance of religious communications as a kind of community meaning-making narratival form for participants in digital communication spaces.

4.3. “Digital” communication

Social media have become the “most important channel[s] of communication […] [in] all areas of human social life” (Saha, Citation2021, p. 349). The truth of this statement has been repeatedly attested in recent years, from the pandemic to high-profile domestic and international political developments including Black Lives Matter, the events of 6 January 2021 in the USA, the protests of farmers in India, the invasion of Ukraine to any number of additional examples. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of social media increased across the board (Saha, Citation2021, p. 349), and social media became the most used sources of information during periods of restricted physical contact (Saha, Citation2021, p. 350).

Despite wide usage in all sectors of society, the relationship of social media to social resilience has been viewed rather ambivalently by resilience researchers. On the one hand, social media are perceived by many researchers as of crucial significance for social resilience today (Gurwitch et al., Citation2007, I; Hughes & White, Citation2006, p. 213; Powell, Citation2021, p. 107; Reuter & Spielhofer, Citation2017, p. 168; Saha, Citation2021, p. 347). On the other hand, however, others have highlighted the potential for negative impact on social resilience presented by social media, seeing the “COVID-19 pandemic as the first social media infodemic” (Saha, Citation2021, p. 357). Thus, a deeper understanding of the interrelation between social media and social resilience remains a current research desideratum (Houston, Citation2018, p. 21).Footnote13

To look to just one field of particular relevance to present interests, insights may be gleaned from the field of disaster communication research concerning how to approach the collection, documentation and analysis of what might be called digital communication artifacts and the roles that social media can play. Social media, and Twitter in particular (Houston, Hawthorne et al., Citation2015, p. 11), have played a central role in disaster communication research in facilitating communications among a variety of actors and processes in disaster response (Houston, Hawthorne et al., Citation2015, p. 8). Researchers have been able to show, for example, that trust in social media messages from official institutions and organizations is significantly higher during disasters than toward private user groups (Reuter & Spielhofer, Citation2017, p. 172). However, the increased basic trust does not apply to government agencies, in whom trust has been “near-record lows” for several years, at least in the United States (Wise Citation2021, 27). As a result, other official institutions such as companies, social organizations, and even religious groups have held a special degree of potential influence in their social media communications during the crisis period (Paton et al. Citation2008, 46).

To identify effective - i.e., trusted and impactful - digital communication artifacts for our research, we decided that the Twitter user accounts of official non-governmental groups would be the primary focus. In addition, due to the functionality to actively follow user accounts, a user account’s number of followers provides an easy way to track its influence.

4.4. “Religious” communication

The last and at the same time most significant specification of the research focus on “digital religious communication” concerns the “religious”. Just as in the relation of social resilience and digital communication, here, too, researchers of social resilience have not yet paid extensive attention to the interrelation of social resilience and religion. So far, no resilience framework exists relating social resilience to religion, although the importance of the other is repeatedly pointed out by scholar in both research areas.Footnote14

Although no overarching framework for relating religion and social resilience is yet available, a number of individual studies have been published in recent years, mostly with a focus on particular aspects of the link between resilience and religion. These can be categorized according to the three dimensions of Houston et al.’s model not related to infrastructure: “Community Relationships,” “Community Attributes” and “Strategic Communication Processes” (Houston et al. Citation2015b, 274):

In the area of “Community Relationships,” several researchers have drawn attention to the social capital offered by religious communities that are well-integrated into society (Holton, Citation2010, p. 67; MHum et al., Citation2011, p. 313). These communities provide crucial “community support” (Francis, Citation2019, p. 509),Footnote15 which, it has been suggested, could be used in more intentional cooperation with governmental or other official agencies than has been the case to date (Ager et al., Citation2015, p. 216; McCabe et al., Citation2014, p. 96).

A more theoretical reflection is found in studies that can be related to what Houston calls “community attributes”. Incorporating ethical perspectives, Schneider and Vogt, for example, discuss the importance of “realism and problem awareness (1), process orientation (2), and relativizing the difference between descriptive and prescriptive (3)” (Schneider & Vogt Citation2018, pp. 192–196). Another recent essay by Steinmaurer looks at the ethical dimensions of social resilience in relation to the context of the digital (Steinmaurer Citation2019, pp. 40–44).

Applied and theoretical perspectives come together in studies which might be classified in relation to “Strategic Communication Processes”, especially those focused on what Houston et al. call “Community Narratives”. These studies empirically identify religious narratives, trace their development and evaluate their impact on the group, and some even reflect on the theological content of the narratives.Footnote16

This latter area of “community narratives” has particular relevance for our research interests in three respects: First, the study of religious narratives in social discourses includes an empirical component and can therefore be related to existing research on communication that is effective in cultivating resilience. Second, the empirical study of religious narratives can be related to existing research in religious studies and related fields, including sociology of religion and theology. And third, narratives constitute a direct interface between individual and social resilience. Hauschildt, for example, points out with regard to individual resilience that in crisis situations, “acquired resilience resources, including spiritual and religious ones, themselves fall into a state of crisis” (Hauschildt Citation2016a, p. 102). These resources are then renegotiated on the basis of “communicative experiences” and thus become relevant at the level of social resilience.

Our interest in religious narratives as community narratives – and, more specifically, community narratives as these are represented in digital communication – required that such narratives be collected from communicators whose communications could form a database subjectable to methods of data analysis. As discussed above, ideally those communicators are official, but non-governmental actors, with whom the recipients already had a relationship of trust before the pandemic, and whose values they believed they shared. Now adding the additional layering of the religious to the formation of this communication profile, these sources of communication can be identified in the context of social media as official accounts of religious institutions, organizations, churches and religious leaders.

5. Conclusion and future research directions

The significance and value of the theoretical model presented in this article may be summarized with the following three points:

The loss of social resources (Richter, Citation2021, p. 16) (e.g., personal contacts, community, and the information circulation connected with these) during the pandemic led in many cases to a massive increase in social media use (Saha, Citation2021, p. 348). Recent research on resilience has already demonstrated that social media have been actively used “[for] finding meaning and creating resilience” during the pandemic (Saha, Citation2021, p. 354). This confirms and reinforces the direct connection with resilience theory. This draws attention to the significance of digital communication artifacts from social media platforms as an important resource for research on community and social resilience, both during the pandemic and in crisis situations more broadly.

If “[a]ll that we know about religion and the church, we know through mass media” (Blanke, Citation2012, pp. 222–223), then communication in digital settings or via digital modes is vital for research in religion and theology. One key objective of research on religion is to document, describe and interpret “the manifold explicit and implicit expressions of religion and spirituality in society” in relation to social systems and social change (Richter, Citation2020, p. 121). By examining such expressions in digital manifestations – for example, by documenting and describing digital religious communication in relation to social transformation during the pandemic – further research on digital religious communication could deepen understandings of how faith and religion are interpreted in the digital realm and what exactly the relevance of these communications is for society. Of interest are not only the statements that users make, but also how digital discourses are structured, which participants make up the discourse network, and how religious groups are integrated into society in digital spaces - and all along the way, how both the actors or groups and communication itself demonstrate resilience or facilitate resilience for others.

Lastly, it is important to be cognizant of the complex ways that patterns in social communication “are highly dependent on culture and biography” (Hauschildt, Citation2016b, p. 492). We are not working under the illusions of any kind of digital positivism that might universalize and oversimplify connections between technology and social meaning. To the contrary, exciting transcultural distinctives – i.e., context-specific receptions of context-overarching issues – can be identified precisely via the worldwide reach of common platforms including but not limited to Twitter and thanks to the large amount of data generated through participation on them.

This article has pursued a theoretical goal. Namely, we have synthesized a model of social resilience from the existing literature that combines natural-scientific and social-scientific models of social resilience. This is an important contribution to research on religious communication in digital settings (including in such fields as Religious Studies, Digital Religion, and Digital Theology) since doing so makes it possible to quantify and measure the significance of religious actors’ communicative activity for social resilience. In other work, we are applying this model to analysis of religious organizations’ communication on Twitter during the pandemic, following up on the possible significance of digital religious communication as a social resilience factor.

However, the model holds great potential for quantitative analysis in other areas of social-scientific inquiry, as well. It is one of the strengths of the model presented here that it is operationalizable for research on any social system or societal discourse, such that the term “religious” could be substituted with, for example, “political”, “economic”, or “educational” and so on. In each case, it would be important only that the discourse to be investigated should be clearly defined and its scope demarcated. This makes the model potentially useful for research in such disciplines as Sociology, Political Science, and Economics among others.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This work was supported by the Volkswagen Foundation within the framework of the project ‘The role of transcultural semantics and symbols for resilience during the Corona pandemic – a hermeneutic approach to historical and intercultural expressions of severe crisis’. The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

2 ‘Organizational’ as well as ‘organisational’ are both used in research, reflecting the variation in English spellings.

3 The term ‘collective resilience’ (Richter (Citation2021, p. 2)) has also been recently used.

4 Following this work, among others, Böschen et al. in 2017 made an empirically based attempt to identify similar lines of research for the general concept of resilience (Böschen et al. (Citation2017)). These have in part great similarity to the results found by Endreß/Maurer and Koliou et al.

5 Bruneau's model has been used repeatedly as the basis for other models, for example, in 2010 by Renschler et al. for the PEOPLEs resilience framework (Renschler et al. (Citation2010)) and also in 2010 by Cimellaro et al. for an infrastructure-oriented resilience model (Cimellaro et al. (Citation2010)).

6 The context of crisis is by no means coincidentally present, but is given by the fact that ‘unfortunately, it is the existential crisis situation that leads to the becoming visible, possibly even to the genesis of resilience.’ (Richter (Citation2014, p. 265)).

7 This was noted by Becker et al. in 2013 within an overview of the conceptual understanding of social resilience as a central aspect of a variety of resilience models. It continues to hold true, as seen, for example, in Reuter (Reuter and Spielhofer (Citation2017, p. 168)) or Houston et al. (Houston et al. (Citation2017, p. 354)).

8 Also represented in this way, for example, by Chewning et al. (Chewning et al. (Citation2013, p. 240)).

9 It is worth noting that three nearly identical lines of research have been identified by Hiebel et al. with respect to individual resilience. This potentially strong similarity between individual and social resilience may be a fruitful line of inquiry to follow in additional studies, aimed at developing shared, or at least complementary, understandings of resilience. See: Hiebel: (Hiebel et al. (Citation2021, pp. 9–10)). The three lines of research on individual resilience are summarized there under the terms ‘Immunity, Stability or Resistance’, ‘Bouncing Back or Recovery’, and ‘Growth.

10 First called for in detail by Manyena et al. (Manyena et al. (Citation2011, p. 418)). Adopted, for example, by Houston et al. (Houston, Spialek et al. (Citation2015, p. 270)), later in a weakened distinction from the second line of research (see his elaboration on the metaphor in (Houston (Citation2018, p. 19))).

11 The concept of crisis used in the social science studies referred to above is of a system-theoretical nature. Similar to the natural science studies, a restriction of the functionality or quality of the system is already considered a crisis. Therefore, no existential character of the crisis situation is intended, although in research on other aspects of resilience that may be important. (Breyer and Janhsen (Citation2021, p. 41)) Possible causes of the crisis can include both direct effects on the system (such as natural disasters, see (Bruneau et al. (Citation2003, p. 736))) or changes in external circumstances (such as an increase in the complexity of the social system as a whole in the case of economic stressors, see (Koliou et al. (Citation2018, p. 14))).

12 The aspect of ‘self-efficacy’ is a theologically intensively discussed topic, which for example in the context of the DFG-FOR 2686 is addressed by Cornelia Richter under the term ‘individual self-care’ (Richter and Blank (Citation2016a, p. 69)).

13 We could not identify any frameworks published since Houston's remark that allow a more precise description of the relationship.

14 See, for example, (Spradley and Spradley (Citation2021, p. 51)). Listed here is an overview of the currently most important resilience frameworks in the pandemic context.

15 The same can be found in Buys (Buys (Citation2020, pp. 13–14)) and from an Islamic perspective in Bentley (Bentley et al. (Citation2020, p. 262)). Due to the comparability of the results to the Islamic context, an interreligious view on resilience would be interesting.

16 For more empirically oriented examples, see Holton (Holton (Citation2010, p. 67)) and MHum (MHum et al. (Citation2011, p. 313)). Analogously, for more theoretically oriented examples, see Duyndam (Duyndam (Citation2017, p. 175)) and Buys (Buys (Citation2020, pp. 11–13)).

References

- Ager, J., E. Fiddian-Qasmiyeh, and A. Ager. “Local Faith Communities and the Promotion of Resilience in Contexts of Humanitarian Crisis.” Journal of Refugee Studies, vol. 28, no. 2, 2015, pp. 202–21. https://academic.oup.com/jrs/article/28/2/202/1547290. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fev001.

- Ang, C. 2021. Ranked: The World’s Most Popular Social Networks, and Who Owns Them. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/ranked-social-networks-worldwide-by-users/

- Aristotle., 1989. Aristotle in 23 Volumes: Metaphysics, Book 7. Translated by Hugh Tredennick. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0052%3Abook%3D7%3Asection%3D1041b

- Becker, J., D. Paton, and S. McBride. 2013. “Improving Community Resilience in the Hawke’s Bay: A Review of Resilience Research, and Current Public Education, Communication and Resilience Strategies.” GNS Science Report: 2012/38. Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited.

- Bentley, J., F. Mohamed, N. Feeny, L. Ahmed, K. Musa, A. Tubeec, D. Angula, M. Egeh, and L. Zoellner. “Local to Global: Somali Perspectives on Faith, Community, and Resilience in Response to COVID-19.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, vol. 12, <SE-START > NO. </SE-START > S1, 2020, pp. S261–S263. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2020-49319-003.html. doi: 10.1037/tra0000854.

- Blanke, E. 2012. Systemtheoretische Beobachtungen Der Theologie. Tectum Wissenschaftsverlag.

- Bonß, W. 2015. “Karriere Und Sozialwissenschaftliche Potenziale Des Resilienzbegriffs. In.” M. Endreß & A. Maurer (Eds.), Resilienz Im Sozialen: Theoretische Und Empirische Analysen, 15–32. Springer Fachmedien.

- Böschen, S., C. Binder, and A. Rathgeber. “Resilienzkonstruktionen: Divergenz Und Konvergenz Von Theoriemodellen - Eine Konzeptionell-Empirische Analyse.” GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society, vol. 26, no. 1, 2017, pp. 216–24. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/oekom/gaia/2017/00000026/a00101s1/art00009#. doi: 10.14512/gaia.26.S1.9.

- Breyer, T., and A. Janhsen. 2021. “Empathie Als Desiderat in Der Gesundheitsversorgung – Normativer Anspruch Oder Professionelle Kompetenz? Preprint.” In C. Richter (Ed.), An Den Grenzen Des Messbaren: Die Kraft Von Religion Und Spiritualität in Lebenskrisen, 37–57. Kohlhammer.

- Bruneau, M. [Michel], S. Chang, R. Eguchi, G. Lee, O.’ Rourke T. Reinhorn, A. Shinozuka, M. Tierney, K. Wallace, W. Von Winterfeldt, et al. “A Framework to Quantitatively Assess and Enhance the Seismic Resilience of Communities.” Earthquake Spectra, vol. 19, no. 4, 2003, pp. 733–52. doi: 10.1193/1.1623497.

- Buys, P. “Building Resilient Communities in the Midst of Shame, Guilt, Fear, Witchcraft, and HIV/AIDS.” Koers - Bulletin for Christian Scholarship, vol. 85, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1–16. doi: 10.19108/KOERS.85.1.2464.

- Chewning, L., C. ‑H. Lai, and M. Doerfel. “Organizational Resilience and Using Information and Communication Technologies to Rebuild Communication Structures.” Management Communication Quarterly, vol. 27, no. 2, 2013, pp. 237–63. doi: 10.1177/0893318912465815.

- Cimellaro, G., A. Reinhorn, and M. [Michel]. Bruneau. “Seismic Resilience of a Hospital System.” Structure and Infrastructure Engineering, vol. 6, no. 1-2, 2010, pp. 127–44. doi: 10.1080/15732470802663847.

- Cummings, C., S. Gopi, and S. Rosenthal. “Vaccine Hesitancy and Secondary Risks” In D. Berube (Ed.), Pandemic Communication and Resilience, 2021, 89–105. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Daugherty, C. 2021. “Pandemic Resilience: What We Can Learn from a Rural Liberian Village’s Response to Ebola.” In D. Berube (Ed.), Pandemic Communication and Resilience, 295–305. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Ding, H., and Y. Tang. 2021. “Outbreak Narratives in Pandemics: Resilience Building in Communicating About 1918 Influenza and SARS.” In D. Berube (Ed.), Pandemic Communication and Resilience, 33–47. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Duyndam, J. 2017. “Resilience Beyond Mimesis, Humanism, Autonomy, and Exemplary Persons.” In B. Becking, A.-M. Korte, & L. Van Liere (Eds.), Numen Book Series : Vol. 156. Contesting Religious Identities (Vol. 156, 175–93. Brill. https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004337459/B9789004337459_013.xml.

- Endreß, M., and A. Maurer. 2015a. “Einleitung.” In M. Endreß & A. Maurer (Eds.), Resilienz Im Sozialen: Theoretische Und Empirische Analysen, 7–14. Springer Fachmedien. https://books.google.de/books?hl=de&lr=&id=JhZRBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA5&dq=Resilienz+im+Sozialen&ots=ilL9qXVsY1&sig=9EWpvLYU-AKY3TeiMoq32H_4J-I#v=onepage&q=Resilienz%20im%20Sozialen&f=false.

- Endreß, M., and A. Maurer. 2015b. “Einleitung.” In M. Endreß & A. Maurer (Eds.), Resilienz Im Sozialen: Theoretische Und Empirische Analysen, 7–14. Springer Fachmedien. https://books.google.de/books?hl=de&lr=&id=JhZRBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA5&dq=Resilienz+im+Sozialen&ots=ilL9qXVsY1&sig=9EWpvLYU-AKY3TeiMoq32H_4J-I#v=onepage&q=Resilienz%20im%20Sozialen&f=false.

- Endreß, M., & Maurer, A. (Eds.)., 2015c. Resilienz Im Sozialen: Theoretische Und Empirische Analysen [Resilience in the Social: Theoretical and Empirical Analyses]. Springer Fachmedien.

- Ferraris, M. 2013. Documentality: Why It Is Necessary to Leave Traces. Fordham University Press.

- Francis, J. “Integrating Resilience, Reciprocating Social Relationships, and Christian Formation.” Religious Education (Education), vol. 114, no. 4, 2019, pp. 500–12. ), doi: 10.1080/00344087.2019.1631948.

- Grieser, D. 2015. Analysis I: Eine Einführung in Die Mathematik Des Kontinuums. Springer Fachmedien.

- Gurwitch, R. H., B. [B. ]. Pfefferbaum, J. M. Montgomery, R. W. Klomp, and D. B. Reissman. 2007. Building community resilience for children and families. https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources//building_community_resilience_for_children_families.pdf

- Hauschildt, E. “Resilienz Und Spiritual Care: Einsichten Für Die Aufgabe Von Seelsorge Und Diakonie - Und Für Die Resilienzdebatten [Resilience and Spiritual Care: Insights for the Task of Pastoral Care and Diakonia - and for the Resilience Debates].” Praktische Theologie, vol. 51, no. 2, 2016a, pp. 100–5. ), doi: 10.14315/prth-2016-0209.

- Hauschildt, E. 2016b. “Spiritueller Bedarf – Recht Auf Religion – Resilienz Im Vollzug: Drei Phänomene Und Ihre Kommunikative Gestalt Im Alter Bei Geistiger Behinderung Oder Chronischer Psychischer Erkrankung.” In S. Müller & C. Gärtner (Eds.), Gesundheit. Politik - Gesellschaft - Wirtschaft. Lebensqualität Im Alter.: Perspektiven Für Menschen Mit Geistiger Behinderung Und Psychischen Erkrankungen, 485–96. Springer Fachmedien.

- Hiebel, N., M. Rabe, K. Maus, F. Peusquens, L. Radbruch, and F. Geiser. “Resilience in Adult Health Science Revisited—A Narrative Review Synthesis of Process-Oriented Approaches.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 12, 2021, pp. 659395. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.659395.

- Holton, J. “Our Hope Comes from God”: Faith Narratives and Resilience in Southern Sudan.” Journal of Pastoral Theology, vol. 20, no. 1, 2010, pp. 67–84. doi: 10.1179/jpt.2010.20.1.005.

- Houston, B. “Community Resilience and Communication: Dynamic Interconnections between and among Individuals, Families, and Organizations.” Journal of Applied Communication Research, vol. 46, no. 1, 2018, pp. 19–22. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2018.1426704.

- Houston, B., J. Hawthorne, M. Perreault, E. H. Park, M. Goldstein-Hode, M. Halliwell, S. McGowen, R. Davis, S. Vaid, J. McElderry, et al. “Social Media and Disasters: A Functional Framework for Social Media Use in Disaster Planning, Response, and Research.” Disasters, vol. 39, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1–22. doi: 10.1111/disa.12092.

- Houston, B., M. Spialek, J. Cox, M. Greenwood, and J. First. “The Centrality of Communication and Media in Fostering Community Resilience: A Framework for Assessment and Intervention.” American Behavioral Scientist (Scientist), vol. 59, no. 2, 2015, pp. 270–83. doi: 10.1177/0002764214548563.

- Houston, B., M. Spialek, J. First, J. Stevens, and N. First. “Individual Perceptions of Community Resilience following the 2011 Joplin Tornado.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, vol. 25, no. 4, 2017, pp. 354–63. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12171.

- Hughes, P., and P. White. 2006. “The Media, Bushfires and Community Resilience.” In D. Paton & D. Johnston (Eds.), Disaster Resilience: An Integrated Approach, 213–25. Charles C. Thomas. https://books.google.de/books?hl=de&lr=&id=B-1VGNdM8lkC&oi=fnd&pg=PA213&dq=The+media,+bushfires+and+community+resilience&ots=SWtWRIHw9D&sig=w0D2VMS6M_xJKZnJFiDSEHR1nDA#v=onepage&q=The%20media%2C%20bushfires%20and%20community%20resilience&f=false.

- Koliou, M., J. van de Lindt, T. McAllister, B. Ellingwood, M. Dillard, and H. Cutler. “State of the Research in Community Resilience: Progress and Challenges.” Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure, vol. 5, no. 3, 2018, pp. 1–34. (Author Manuscript). doi: 10.1080/23789689.2017.1418547.

- Longstaff, P., and S. ‑U. Yang. “Communication Management and Trust: Their Role in Building Resilience to “Surprises” Such As Natural Disasters, Pandemic Flu, and Terrorism.” Ecology and Society, vol. 13, no. 1, 2008, pp. 1–14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26267909. doi: 10.5751/ES-02232-130103.

- Luhmann, N. 1995. Social Systems: Translated by John Bednarz, Jr. with Dirk Baecker. Writing Science. Stanford University Press.

- Manyena, B., G. O’Brien, P. O’Keefe, and J. Rose. “Disaster Resilience: A Bounce Back or Bounce Forward Ability? Ocal Environment.” The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 5, 2011, pp. 417–24.

- McAllister, T. “Research Needs for Developing a Risk-Informed Methodology for Community Resilience.” Journal of Structural Engineering, vol. 142, no. 8, 2016, pp. 1–10. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0001379.

- McCabe, L., N. Semon, J. Lating, G. Everly, C. Perry, S. Straub Moore, A. Mosley, C. Thompson, and J. Links. “An Academic-Government-Faith Partnership to Build Disaster Mental Health Preparedness and Community Resilience.” Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974), vol. 129 Suppl 4, no. Suppl 4, 2014, pp. 96–106. doi: 10.1177/00333549141296S413.

- MHum, Tuti, Holly Bell, Loretta Pyles, and Ratonia C. Runnels. “Spirituality and Faith-Based Interventions: Pathways to Disaster Resilience for African American Hurricane Katrina Survivors.” Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, vol. 30, no. 3, 2011, pp. 294–319. doi: 10.1080/15426432.2011.587388.

- Paton, D. “Disaster Preparedness: A Social‐Cognitive Perspective.” Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, vol. 12, no. 3, 2003, pp. 210–6. doi: 10.1108/09653560310480686.

- Paton, D. “Measuring and Monitoring Resilience in Auckland.” GNS Science Report, vol. 18, 2007, pp. 1–88.

- Paton, D., B. Parkes, M. Daly, and L. Smith. “Fighting the Flu: Developing Sustained Community Resilience and Preparedness.” Health Promotion Practice, vol. 9, no. 4 Suppl, 2008, pp. 45S–53S. doi: 10.1177/1524839908319088.

- Paton, D., L. Smith, and D. Johnston. “When Good Intentions Turn Bad: Promoting Natural Hazard Preparedness.” Australian Journal of Emergency Management, vol. 20, no. 1, 2005, pp. 25–30.

- Pfaffenberg, F. 2015. Twitter Als Basis Wissenschaftlicher Studien: Eine Bewertung Gängiger Erhebungs- Und Analysemethoden Der Twitter-Forschung. Springer VS.

- Pfefferbaum, B. [Betty], R. Pfefferbaum, P. Nitiéma, B. Houston, and R. Van Horn. “Assessing Community Resilience: An Application of the Expanded CART Survey Instrument With Affiliated Volunteer Responders.” American Behavioral Scientist (Scientist, vol. 59, no. 2, 2015, pp. 181–99.), doi: 10.1177/0002764214550295.

- Powell, A. 2021. “COVID and Cuomo: Using the CERC Model to Evaluate Strategic Uses of Twitter on Pandemic Communications.” In D. Berube (Ed.), Pandemic Communication and Resilience, 107–24. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Renschler, C. S., A. E. Frazier, L. A. Arendt, G. P. Cimellaro, A. M. Reinhorn, and M. [M. ]. Bruneau. 2010. “Developing the ‘Peoples’ Resilience Framework for Defining and Measuring Disaster Resilience at the Community Scale.” Proceedings of the 9th U.S. National and 10th Canadian Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Paper No. 1827, 1–10.

- Reuter, C., and T. Spielhofer. “Towards Social Resilience: A Quantitative and Qualitative Survey on Citizens’ Perception of Social Media in Emergencies in Europe.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 121, 2017, pp. 168–80. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306052987_Towards_social_resilience_A_quantitative_and_qualitative_survey_on_citizens%27_perception_of_social_media_in_emergencies_in_Europe. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2016.07.038.

- Richter, C. 2014. “Vertrauen Und Resilienz Als Performanzphänomene: Konsequenzen Der Aktuellen Diskurses Für Die Theologie.” In P. David, H. Rosenaus, & A. Schart (Eds.), Theologie - Forschung Und Wissenschaft: Vol. 37. Wagnis und Vertrauen: Denkimpulse zu Ehren von Horst-Martin Barnikol (Vol. 37, 253–70. Lit Verlag.

- Richter, C. 2020. “What Systematic Theology Does.” In M. Robinson & I. Inderst (Eds.), What Does Theology Do, Actually? Observing Theology and the Transcultural (Vol. 1, 117–34. Evangelische Verlangsanstalt.

- Richter, C. “Integration of Negativity, Powerlessness and the Role of the Mediopassive: Resilience Factors and Mechanisms in the Perspective of Religion and Spirituality.” Interdisciplinary Journal for Religion and Transformation in Contemporary Society, vol. 7, no. 2, 2021, pp. 491–513. Preprint). doi: 10.30965/23642807-bja10027.

- Richter, C., and J. Blank. “Resilienz “Im Kontext Von Kirche Und Theologie: Eine Kurze Einführung in Den Stand Der Forschung.” Praktische Theologie, vol. 51, no. 2, 2016a, pp. 69–74. doi: 10.14315/prth-2016-0204.

- Pohl-Patalong, Uta, and Cornelia Richter. “Editorial.” Praktische Theologie, vol. 51, no. 2, 2016b, pp. 67–8. doi: 10.14315/prth-2016-0203.

- Richter, C., and F. Geiser. 2021. “Hilft Der Glaube Oder Hilft Er Nicht? “Von Den Herausforderungen, Religion Und Spiritualität Im Interdisziplinären Gespräch Über Resilienz Zu Erforschen.” In C. Richter (Ed.), An Den Grenzen Des Messbaren: Die Kraft Von Religion Und Spiritualität in Lebenskrisen (Vol. 3, 9–21. W. Kohlhammer GmbH. https://books.google.de/books?hl = de&lr=&id = MdQmEAAAQBAJ&oi = fnd&pg = PA9&dq = An + den + Grenzen + des + Messbaren.+Die + Kraft + von + Religion + und + Spiritualit%C3%A4t + in + Lebenskrisen&ots = LnfrcqfVPR&sig = Q2_zfaKR_wDTa9Cc6y4srXhiSXQ#v = onepage&q = An%20den%20Grenzen%20des%20Messbaren.%20Die%20Kraft%20von%20Religion%20und%20Spiritualit%C3%A4t%20in%20Lebenskrisen&f=false.

- Robinson, M. R. 2020. “Introduction: ‘What Does Theology Do’ as a Transcultural Research Perspective: A ‘Model-Of’ a ‘Model-For’ Theological Research.” In M. Robinson & I. Inderst (Eds.), What Does Theology Do, Actually? Observing Theology and the Transcultural, 25–36. Evangelische Verlangsanstalt.

- Saha, A. 2021. “Social Media Creating Resilient Communities During COVID-19: India, Bangladesh & Pakistan.” In D. Berube (Ed.), Pandemic Communication and Resilience, 347–62. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Schleiermacher, F. 2011. Brief Outline of Theology as a Field of Study: Revised Translation of the 1811 and 1830 Editions, with Essays and Notes by Terrence N. Tice (Third Edition). Westmindster John Knox Press.

- Schneider, M., and M. Vogt. 2018. “Responsive Ethik: Reflexionen Zum Theorie-Praxis-Verhältnisam Beispiel Von Resilienz Und Sozialem Wandel.” In B. Emunds (Ed.), Ethik Und Gesellschaft : Vol. 4. Christliche Sozialethik - Orientierung welcher Praxis? Friedhelm Hengsbach SJ zu Ehren (1st ed., 179–200.

- Spradley, T., and E. Spradley. 2021. “The Building Blocks of Pandemic Communication Strategy: Models to Enable Resilient Risk and Crisis Communication.” In D. Berube (Ed.), Pandemic Communication and Resilience, 51–73. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Steinmaurer, T. 2019. “Digitale Resilienz Im Zeitalter Der Datafication.” In M. Litschka & L. Krainer (Eds.), Ethik in Mediatisierten Welten. Der Mensch Im Digitalen Zeitalter: Zum Zusammenhang Von Ökonomisierung, Digitalisierung Und Mediatisierung, 31–47. Springer VS. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-26460-4_3 citeas.

- Tallapragada, M. 2021. “Pandemics and Resiliency: Psychometrics and Mental Models.” In D. Berube (Ed.), Pandemic Communication and Resilience, 75–88. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- WHO., 2021. Pandemie der Coronavirus-Krankheit (COVID-19) [Coronavirus Disease Pandemic (COVID-19)]. https://www.euro.who.int/de/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov

- Wise, K. 2021. “Developing Trust in Pandemic Messages.” In D. Berube (Ed.), Pandemic Communication and Resilience, 19–32. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.