Abstract

This article draws on Rebecca Schneider's thoughts on performance within archival culture (2001) in order to examine the use of HeLa cells in recent artistic practice. HeLa is one of the most commonly used cell lines in scientific research, renowned for its ‘immortality’ in vitro. The HeLa cell line originated from cervical cancer cells that were taken from an African American woman named Henrietta Lacks in 1951. Lacks died eight months after the biopsy, but her cells – which were removed without her knowledge and consent – live on and multiply in scientific laboratories worldwide. As artists working in the biological arts attempt to reimagine the controversial narratives surrounding HeLa and Henrietta Lacks, this paper argues that employing biological materials such as HeLa cells in artistic practice often gives rise to a flesh-like ‘object’ that resists the archive that instead privileges documentary and object remains. In this respect, the use of HeLa cells in some artistic work is reminiscent of performance's challenge to traditional archival logic. Despite disappearing in death, documentation and even in the moment of the live encounter, HeLa and its attendant histories nevertheless remain in material and immaterial acts that these artworks and their documentary texts participate in. Such practices importantly prompt areconceptualisation of our relationship to the body in light of the potential effects of contemporary biotechnological advancements on archival logic. It is this reconceptualisation which I suggest may be bestapproached, therefore, in dialogue with performance theory on appearance and disappearance within archival culture.

On 4 October 1951, an African American woman from Virginia died of cervical cancer. In 2011, as I write this paper, the cells that originated from her cancer sit in petri dishes, freezers and flasks in laboratories all over the world. Among scientific communities these cells are known as HeLa (Hee-Lah), retaining a visible trace of the woman named Henrietta Lacks, from whom the original cells were excised by cervical biopsy nearly six decades previously. Separated from Lacks' body just a few months prior to her untimely death at age 31, these cells gave rise to what is now considered a ‘workhorse’ of the cellular biology lab: the HeLa cell line. Under the right conditions, HeLa cells can grow indefinitely and are, therefore, scientifically and commercially useful because they are in endless supply. Among myriad uses, HeLa cells have been launched into space to study the effects of space travel on humans; exposed to huge amounts of radiation in order to examine the damage done to human cells by nuclear weapons; and injected into rats – who subsequently developed malignant tumours – as part of research into cancer growth. Most notably, the cell line that was derived from Henrietta Lacks' cells was integral to the development of the polio vaccine.Footnote 1

Drawing on performance theory on the archive and archiving, this article examines the use of HeLa cells within recent artistic practice and the appropriation of the story of the woman these cells came from, Henrietta Lacks. In particular, I argue that the increased use of biological material, such as HeLa cells, in art practices over the past decade has given rise to a flesh-like ‘object’ (for want of a better term) which is ‘reminiscent’Footnote 2 of performance's challenge to the traditional archive. I draw on Rebecca Schneider's writing on the position of performance within the context of archival culture to suggest that, much like performance, these living/biological (or semi-living) objects often ‘refuse the archive its privileged “savable” original’Footnote 3 and yet they also remain despite disappearing in documentation, death and even in the moment of one's encounter with them during the live event. Furthermore, I suggest that we think of the archive as act: an approach to archival thought espoused by Schneider in dialogue with the well-rehearsed idea of performance's ontology as disappearance, as put forward by Peggy Phelan. This has the potential to prompt the acknowledgement of embodied and other kinds of remembering in which these artworks, their biological component, and their documentary texts might be participating.

This article introduces and offers a critical response to the work of three artists who have employed HeLa cells in their artistic practice: Scottish-born artist Christine Borland, Australian-based artist Cynthia Verspaget, and Swiss artist Pierre-Philippe Freymond. HeLa and the ‘story’ of Henrietta Lacks is differently appropriated within each of their works and each artistic encounter raises different questions about what is at stake in the use of HeLa cells as a tool for remembering Henrietta Lacks, or for negotiating the appearance of certain histories of HeLa and Lacks through that which remains. Borland's treatment of HeLa cells, for example, reiterates the object status that HeLa acquires in the scientific community and so her approach follows the logic of the archive that references a body which no longer exists through its material remains. The use of HeLa cells in Verspaget and Freymond's work, on the other hand, arguably engages in acts of production and reception that suggest that the history of Lacks and HeLa has both been written and is, at the same time, continually being reconstructed through our encounters with its material and immaterial remains. By drawing on the proposal that traditional archival logic equates performance's ontology as disappearance with the inability to remain,Footnote 4 I propose that the relationship between the archive and performance is integral to a critical understanding of the use of HeLa cells in art practice and the use of living material in the biological arts more generally. It is through this dialogue between performance studies and the biological arts that we are able to develop an analytical vocabulary for articulating the way in which bioart appropriates and challenges life science tools. Performance theory is particularly important because these tools archive certain bodies by giving other ways of knowing and encountering the body to disappear. Biotechnological toolsand practices prompt new (and reiterate existing) challenges for apolitics of visibility and an ethics of responsibility to the other. The significance and relevance of performance theory in contemplating thesechallenges – and their wider implications in the creation and reception of artistic work – cannot, therefore, be underestimated.

Histories of Henrietta

When people ask – and seems like people always be askin to where I can't never get away from it – I say, Yeah, that's right, my mother name was Henrietta Lacks, she died in 1951, John Hopkins took her cells and them cells are still livin today, still multiplyin, still growin and spreadin if you don't keep em frozen. Science calls her HeLa and she's all over the world in medical facilities, in all the computers and the Internet everywhere. Deborah LacksFootnote 5

In the archive, flesh is given to be that which slips away. Flesh can house no memory of bone. Only bone speaks memory of flesh. Flesh is blindspot.Rebecca SchneiderFootnote 6

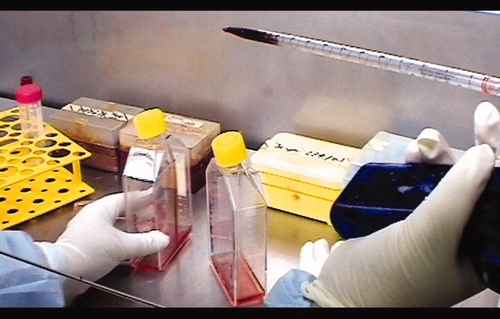

When Henrietta Lacks' cervical cancer cells were removed, they were placed into a flask to be cultured, and like any other growing cells, they were subcultivated (separated into different flasks) over time, to give the cells the necessary space to continue to grow. This is what gives the cells the status of a ‘cell line’, a term that refers to ‘a population of cells derived from [human] animal tissue and grown in vitro by serial sub cultivations for indefinite periods of time’.Footnote 7 However, unlike ‘normal’ human cells, which would only be able to survive a certain number of sub cultivations, Lacks' cancer cells never stopped growing. Indeed, ordinary human cells are subject to the Hayflick limit, which means that they only divide approximately fifty times when kept in culture outside of the body.Footnote 8 However, these cancerous cells continued to divide and grow indefinitely and, as such, they were established as a cell line and afforded the scientific appropriation of the term ‘immortal’.Footnote 9 The cells have this ability to grow indefinitely because they contain a rare enzyme which allows them to continue dividing ad infinitum in cell culture.Footnote 10 The cell line was subsequently named HeLa and is considered to be the first human immortal cell line. Here, I refer to the term ‘HeLa’ to capture both the scientific and socio-cultural resonances of cells that derive from Lacks' original biopsy. ‘HeLa’, therefore, becomes a linguistic signifier for both the material cells that exist in laboratories all over the world and the immaterial discursive economies which constitute these cells within scientific practice and, more recently, in the cultural imaginary following the publication of Skloot's text. The term ‘HeLa cells’, on the other hand, is employed in this article to foreground temporally the material cells that exist within scientific practice and, more specifically, within the artistic practices discussed here. ‘HeLa cell line’ is simply used in relation to its scientific definition, as a ‘population’ of cells that derived from cells that were taken from Henrietta Lacks.

As Lacks' daughter observes in the quotation above, there are many electronic and material remains of her mother, as well as, I would add, of HeLa and the narratives surrounding both. However, Henrietta's ‘story’ has only very recently been archived by scientific journalist Rebecca Skloot in The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, where the quotation from Lacks' daughter appears. Whilst Skloot's account is preceded by other histories of Lacks' cells and the HeLa cell line,Footnote 11 her book is the first sustained, ethnographically informed attempt to write a ‘biography of both the cells and the woman they came from’.Footnote 12 Interviewing friends and living members of the Lacks family, Skloot documents the situation surrounding the removal of Lacks' cells and the difficult fact that they were taken without her knowledge or consent. She notes that the storage and use of tissue samples after routine medical procedures – such as blood tests and the removal of moles – without explicit consent is as much a common and legal practice in the US today as it was in the 1950s.Footnote 13 Skloot's approach, in its move towards fixing the historical moment of this event, thus follows an archival logic that aims to record permanently the cells' and Henrietta's biography in written form. This is arguably the same West-identified archival logic that performance theorist Rebecca Schneider suggests approaches flesh, that is, the stuff of performance, ‘as blindspot’: as that which is given to disappear in anarchive that instead privileges document and object remains.Footnote 14 In other words, in current archival culture the document is seen as remaining but the flesh is not.

Paradoxically, HeLa challenges the dominant approach to the archive that drives Skloot's text. In material terms, the ability of HeLa cells to divide infinitely and reproduce undermines the archive in which ‘flesh is given to be that which slips away’, as Schneider contends above. In the case of these cells, flesh does remain. However, what exactly is ‘archived’ in, or by, HeLa as material remains begs clarification, particularly in view of the fact that there are now many different HeLa strains in use which are said to have derived from Lacks' cancer cells. A discussion concerning what remains, and how that remaining is both produced and received in different contexts, is especially urgent given that an ‘official’ and publicly available record (that we might more readily associate with the archive) ofthe ‘woman behind the cells’ was never attempted prior to Skloot's account, even with the persistence and visibility of the HeLa cell line in the scientific arena. Although the material persistence of HeLa cells in science did not encourage, and even disavowed, the writing of a history of HeLa and its ‘origin’ in/as Henrietta Lacks,Footnote 15 recent explorations withHeLa cells in the art world, despite there being only a handful of works to date, have deliberately sought to engage with this history in a wider public realm.

These artistic attempts to negotiate the history of HeLa and Henrietta Lacks prompt a reconceptualisation of our relationship to the archive and the body. In comparison with Skloot's approach to recording the life and death of Henrietta Lacks, the use of living remains gives rise to a different kind of remembering, which is arguably given to disappear in the traditional archive. Whilst these cells might also archive the life and death of Henrietta Lacks, unlike Skloot's text, they participate materially in both life and death. Furthermore, in the context of art, these cells, and the remembering they enact, have the potential to be encountered through the body of the artist and/or the body of the spectator. This embodied remembering is paradoxically made possible by the use of living material that exists outside of the body. Yet, whilst this kind of remembering might not appear in material terms (such as objects and documents) that are favoured by the archive, it nevertheless remains despite seeming to disappear. I suggest, therefore, that this reconceptualisation of our relationship to the body and the archive in relation to contemporary advancements in biotechnology may be best approached in dialogue with performance theory and its concerns with appearance and disappearance in the archive.

The Object and the Document

The use of HeLa cells within art emerges out of a growing field of contemporary artistic practice which is often referred to in the academy as bioart or the biological arts. Artists working in this area utilise the tools of biotechnology and, in doing so, often include a living or biological component in their practice. Biotechnological techniques, such as tissue culture or genetic engineering, and living or biological materials, such as cells, tissue, bacteria and viruses, are frequently employed as artistic media in bioart practice. Artists and art collectives working in this field have turned to the science lab and the tools and techniques of the life sciences for a number of reasons and with diverse intentions. Australia-based art collective The Tissue Culture and Art Project uses tissue culture as an artistic medium to prompt a wider public debate concerning our relationship to different forms of life that have been created through biotechnological advancements, such as sculptures they call ‘semi-living entities’ that are made possible through in vitro practices. Theatre and art collective, Critical Art Ensemble (CAE) practise and facilitate for their audiences an amateur or hobbyist approach to biology that contextualises issues such as genetic modification and germ warfare within performative situations and scenarios.Footnote 16 These performances work to challenge the discourse of expertise and fear within which a discussion of these issues are ordinarily couched and encountered in the public realm.

Whilst bioart practices span (at least) the past two decades, artistic explorations with HeLa cells are relatively new. One of the earliest uses of HeLa cells in art is a piece by Christine Borland, which was first exhibited at the Exit Art Gallery in New York in 2000. Borland's installation, named HeLa in 2000 and renamed HeLa, Hot in its exhibition in the UK in 2004, features a microscope under which HeLa cells can be observed in nutrient solution in a flask.Footnote 17 The microscope is connected to a small television monitor that displays a magnified view of the cells. In its 2004 version as part of the ‘Wonderful’ exhibition at Bristol's Arnolfini, the installation made reference to the story of Henrietta Lacks in an A4 text statement by the artist. Art critic, David Barrett describes the statement as follows:

The text informs us that we are looking at HeLa cells, which are tumour cells with an unusually fast growth rate, and hence ideal for scientific study. They are used in labs around the world and can be purchased from scientific-supply companies. However, Borland's text goes on to state that HeLa cells are so called because they originate from the tumour that killed the 31-year-old African-American woman Henrietta Lacks back in the 50s. Each HeLa cell contains Lacks' DNA, and it is supposed that there are more of her cells in existence now than there were when she was alive. Furthermore, Lacks' surviving children only discovered that their mother's cells had become astaple of the life sciences when they themselves were asked to provide DNAsamples for comparative study some 20 years after her death.Footnote 18

Borland's text is particularly significant to this discussion because it anticipates an artistic trend towards framing the appearance of HeLa cells in the gallery space in relation to Henrietta Lacks. It is also representative of the dominant mode of engaging with bioart, that is, through its textual, photographic or video documentation. Reviewers, such as Barrett, and journalists of earlier showings of HeLa (which took place as part of an exhibition that toured the US between 2000 and 2004 called Paradise Now: Picturing the Genetic Revolution) describe this encounter with Lacks' story as an artistic attempt to highlight the ‘human’ or ‘social’ history of HeLa cells.Footnote 19 The extent to which Borland is successful in this attempt to emphasise the human aspect, however, is questionable. Significantly, there is no reference to Henrietta Lacks or the issue of consent that is so pertinent to the human story of HeLa in the catalogue text that accompanied the US exhibition.Footnote 20 Presented under a microscope, the cells sustain an aesthetic association with the laboratory environment from which they derive their status as an object of science. An online photograph of the installation space attests to this relation by indexing the artwork's use of technologies of visualisation. Itstechnophilic approach further suggests the artwork's participation in the objectification of the cellular body that is enacted in the process oflooking down a microscope. The spectator is also encouraged to participate in the process by passively observing, through layers of mediation, the magnified image of the cells as seen under the lens on a television screen. Assuming that Barrett's account is accurate, therefore, the story of Henrietta Lacks seems to be subsumed by the technical equipment that constitutes this installation. Furthermore, the framing ofthe work in terms of genetics promotes a scientific perspective that reinforces the object status of the microscopic cellular body in vitro.

The HeLa cells in Borland's installation, therefore, do not deny the archive the object remains it so privileges. The installation even reinforces the objectification of HeLa cells; a reading that would be further encouraged if the cells were said to have been ‘fixed’ in a process of preservation that ultimately leads to cell death. It is only the artist's text in the gallery space, not the way in which the cells are included in the artistic space, that remembers Henrietta Lacks. The text in the UK exhibition remembers Lacks in the same way that Skloot's book follows the dominant logic of the archive to enact a certain memory of Lacks that presumes that memory can only be saved and recorded in/as visible and material documents and objects. This is contrary to my argument that the increased use of biological and living material in art has given rise to a flesh-like sculpture that is reminiscent of performance in its resistance to the traditional archive. However, in the context of this article, Borland's artwork importantly prompts the recognition that whilst the inclusion of living or biological material in art seems to enact this resistance towards traditional archival thinking, it does so in a way that is not dependent onthe reinstatement of what, following Jacques Derrida, we might call the‘metaphysics of presence’.Footnote 21 Rather, it is in the relation between the living/biological component, documentation, and the live event that the use of biological/living material in artistic practice finds its correlation with the challenge to the archive enacted through and by performance. These components (living material, document, event) work against the archive that scripts the disappearance of a certain kind of remembering. In order to address this further, it is necessary first to explore Schneider's proposal that the traditional archive problematically equates performance's ontology as ‘disappearance’ with loss and the inability to remain. It is in dialogue with this argument that we find a vocabulary for understanding the potential use of biological material in artistic practice, to interrogate – and in other cases to reinscribe – the patrilineal archive that operates as ‘a particular social power over memory’.Footnote 22

Performance Remains

Drawing on performance's long-standing association with ephemeralityFootnote 23 and Peggy Phelan's claim that performance ‘becomes itself through disappearance’,Footnote 24 Schneider argues that performance's ephemerality and ontology of disappearance has often been equated with an inability to remain. For Schneider, this conceptualisation of performance, as that which cannot be saved, is dictated by an archival logic identifiable with the West and western societies that privilege the document ‘because the document is what remains’.Footnote 25 She suggests that associating performance with the refusal to remain often leads to an understanding of performance, for the traditional archivist at least, as that which ‘lose[s] a lot of history’.Footnote 26 Conceptualising performance as such, she argues, ignores the different ways in which performance might interrogate archival thinking by offering access to an embodied history and, in doing so, remember and remain differently to objects or documents of the archive. As Schneider reminds us, memory and history do remain in the body, ‘in oral storytelling, live recitation, repeated gesture, and ritual enactment’.Footnote 27 Performance's association with disappearance then is not denied in Schneider's claim, but the appropriation of disappearance as loss is challenged by the author to suggest that the traditional archive requires that performance disappear in order to retain the self-same or singular origin on which the archive depends. She notes:

It is in accord with archival logic that performance is given to disappear, and mimesis (always in a tangled and complicated relationship to the performative) is, in line with a long history of anti-theatricalism, debased ifnot downright feared as destructive of the pristine ideality of all things marked ‘original’.Footnote 28

Drawing on oral history practices and performance re-enactments, she suggests that performance poses a threat to the original and the self-same of the archive because the said practices are ‘always decidedly repeated […] always reconstructive, always incomplete’ and, therefore, constituted by a form of repetition that does not necessarily participate in identicality. To illustrate this Schneider refers to the battle re-enactments of Civil War enthusiast, Robert Lee Hodge, who has the ability to simulate a bloated corpse. She proposes that even though Hodge seems to be invested in identicality through imitation (or mimesis, as Schneider would have it), his performance is engaged with disappearance in such a way that his body becomes a kind of archive for a collective memory in which spectators of his work attest to sharing. In this respect, the body in performance is both given to disappear by traditional archival logic and yet it still remains, even if that remaining is resistant to the material remains that are favoured by the archive. Performance's resistance to traditional archival thinking is not, therefore, dependent on the return to a metaphysics of presence in its ability to remain, even though it may participate in a flesh memory which is affected through bodily and ‘body to body’ engagement.

Disappearance, Schneider reminds us, is not antithetical to remains. Instead, performance ‘does not disappear, but remains as ritual act’ and, as ritual act, both performance and the archive, ‘by occlusion and inclusion script[s] disappearance’.Footnote 29 In other words, Schneider is perhaps proffering an approach to the archive (and performance) that is informed by what one might call performance logic – rather than by an understanding of performance predetermined by the logic of the archive. In this formulation, the archive is interpreted as act that instructs performance to disappear. For Schneider, the archive does this through ‘rituals of domiciliation’ that can be traced back through the etymological root of ‘archive’ to the house of the Greek magistrate, the Archon (Arkhon),Footnote 30 where official documents would be kept. Highlighting the ritualistic nature of the archive and taking up Derrida's claim that ‘there is no political power without control of the archive’,Footnote 31 Schneider situates the archive as an act of political power, which derives from this Ancient Greek patriarchal control over official documents.

Through this understanding of the archive as an act of political power that scripts performance as disappearing, we might begin a critical analysis of the use of HeLa cells in art practice and its attendant scientific practice of tissue culture. Approaching the archive as act also has the potential to acknowledge one's performative relation to more traditional ‘archival’ accounts of Henrietta Lacks and HeLa, especially the history offered by Skloot. Although further exploration of this is beyond the scope of this paper, the reader's participation in ‘securing memory backwards’, as Schneider would say, is never fully guaranteed by the words Skloot chooses but is constituted by spectatorial interpretation of her text through a processual relation that challenges the assumption of a predetermined or fixed reading. Recognising this spectatorial encounter does not deny the responsibility Skloot assumes in her decision to write about HeLa cells, Lacks and Lacks' family in a particular way. Instead, the intention here is to recognise that there are moments – when reading the words of Deborah Lacks for example – when one ‘hears’ a specific voice, aparticular accent and, therefore, an embodiment of those wordsto which one responds in the process of making meaning from thetext.

Considering the archive as act is particularly pertinent to art that uses tissue technologies. Tissue culture, which is the study of cells, tissues and organs that are grown and maintained alive in vitro, arguably participates in practices of archiving the body (human and animal) and other (cellular and micro) entities it recognises and identifies. As such, the archival practices of tissue culture, its hierarchisation of life in terms of taxonomic classifications, and the storing of biological materials in tissue banks are akin to flesh archives. These archives act as a form of political power that, like the traditional archive, give other ways of knowing and encountering the body to disappear. Archival practices in the life sciences, therefore, follow the same drive towards an origin as the traditional archive by (sometimes literally) freezing the division and reproduction of HeLa cells or, for example, by securing an origin through the process of patenting a cell line that has commercial value. To that end, artworks that utilise the tools and techniques of tissue culture, such as the artistic work with HeLa cells described here, inevitably participate in archival practices that are often commercially motivated and treat cells and tissue as commodities. In encounters with HeLa cells in artworks that employ tissue culture techniques, what is ethically and politically at stake is therefore dependent upon the extent to which these artworks follow archival practices that function to sustain a certain kind of memory whilst excluding other ways of remembering. However, as I will demonstrate, artistic work with HeLa cells does have the potential to challenge and to engage the spectator in acts that resist archival practices despite also participating in the violence of foregrounding some ways of knowing at the expense of other ways of encountering living matter.

My proposal that the use of living or biological material in artistic practice has the potential to challenge archival logic does not demand an ontological commitment to a metaphysics of presence. The inclusion of living or biological material in art, and specifically the use of HeLa cells, certainly alludes to what Schneider calls flesh memory as a ‘genetic’ memory that is repeated and that remains in the replication of HeLa cells. Further to this repetition, however, the use of HeLa cells provokes memories which, like Hodge's bloated corpse, have the potential to give rise to ‘body to body transmission’Footnote 32 that is more akin to performance. What is arguably remembered (or not) in these exchanges, for example, is a particular(ised) body; the body of a mother, a woman, an African American and so on. I am suggesting, therefore, that the use of biomaterial in art practice has the potential to resist archival logic through the negotiation of materiality. This negotiation takes place in the marked and unmarked acts that give this material (andits associated meanings) to appear and disappear. It is through one's engagement with biomaterial in the live event and/or documentation that this negotiation takes place, rather than in the identification of this biological material with presence. To say that biological material alone assists bioart practice in resisting the logic of the archive, would simply repeat this logic by assuming that this material guarantees immediate, authentic and full meaning. This conflation of biological material with presence is problematic because it both presupposes that the immaterial traces of biomaterials are lacking meaning and also denies that biological material ‘becomes itself through disappearance’.Footnote 33 It is the ‘disappearance’ of Henrietta's body and the ‘absence’ of differential signifiers, for example, that make possible the appearance of HeLa cells.

Hela as Anti-Archive

Anarchy (n): a state of disorder due to absence or non-recognition of government or other controlling systems.

From Greek ‘Anarkhos’: an ‘without’ + arkhos ‘chief, ruler’

In a project entitled The Anarchy Cell Line, which I interpret here through the artist's commentaries on and images of the work,Footnote 34 Cynthia Verspaget mixes her own blood cells with HeLa cells to create a new ‘artistic’ cell line. The naming of the cell line as anarchistic already assumes a conceptual relation to the archive and its Ancient Greek association with the law and political rule, since its etymological origin arkhos is a derivative of archon, the keeper of official documents. With the addition of the suffix (an-) in ‘anarchy’, one could read Verspaget's title as referring to the transgression of rule or law in the absence or non-recognition of the ruler (an-arkhos). This gives rise to many possible readings and questions relating to anarchy and, therefore, the archive in her work. Who is the absent or non-recognised ruler in The Anarchy Cell Line: is it Henrietta Lacks as the ‘origin’ from whom HeLa is derived? Is the ruler the artist whose work is received in her absence in an interpretive, ongoing and potentially anarchistic process of making meaning that can never be fully controlled by the artist or the spectator? Is the non-recognised authority the scientific gaze that would ordinarily control the visualisation and ordered use of the cell line? Is anarchy a description of the artist's processual enactment of mixing the cells together, which pertains to an understanding of anarchy in terms of chaos: a kind of uncontrollable setting lose of disparate elements that echoes the discourse of contamination often associated with HeLa in the scientific community? Perhaps ‘the anarchy cell line’ is a direct reference to the panic that ensued among the international tissue culture community in the mid 1960s after the proposal that the HeLa cell line had widely contaminated other cells in culture that were previously thought to be immortal cell lines in their own right.Footnote 35 Or might ‘anarchy’ recall evolutionary biologist Leigh Van Valen's proposal, at the turn of the 1990s, that HeLa should be defined as a new species, Helacyton gartleri to recognise that the cell line evolved separately from humans?Footnote 36 Indeed, by proposing a new taxonomic classification for the HeLa cell line, Van Valen inadvertently contextualises HeLa in terms of an anarchical dis-order, which is also echoed in the title of Verspaget's artwork.

In ‘i am a bioartist’, Verspaget highlights the association between what she calls ‘ineffective forms of re-categorising’ the HeLa cell line, such as Van Valen's attempt to reclassify HeLa as a new species and her own work. More specifically she locates the work's relationship to anarchy both in theact of creating the artistic cell line and in the cell line's rebellion againstscience as what anarchist parlance would term the ‘chief’ and final authority on the perception and categorisation of biological materials:

This artistic cell line was created by adding my whole blood to the existing HeLa cell line in an ‘act’ of abject, performative, domesticated anarchy and anarchistic domestication provoking engagement with the complex ideas of women in laboratories as workers, artists and remnants of women as lab tools […] The artistically mediated cell line is anarchistic in that it proposes and somewhat adopts the idea of ‘not-science’ – what cells survive, if they combine, hybridise or if they biologically coexist, essentially the science of things, is not in focus in the same way that the process and interactions of making the cell line, the possibility of hybridization, thequestion of zonal location/ambiguity and […] the appropriation of biological materials are in focus.Footnote 37

Verspaget's description of her artistic process as ‘an act of […] domesticated anarchy and anarchistic domestication’ is reminiscent of Schneider's account of the archive in terms of its rituals of domiciliation. These rituals of domestication, for Verspaget, are inherent in her work simply because she employs the tools of biotechnology, albeit an ‘anarchistic’ employment that attempts to subvert and challenge the way these tools (including HeLa) are ordinarily appropriated in the scientific realm. Just as the archive (as act) scripts performance as disappearing (through rituals of domiciliation) despite performance's reappearance in the memory and body, so too does the scientific gaze and the scientific procedure attempt to control and ‘tame’ HeLa (through rituals of domestication), despite HeLa's material and immaterial resistance to domiciliation. This challenge to domiciliation can be located both in the material refusal of HeLa cells to remain in one place,Footnote 38 and in the ongoing return of Henrietta's ‘ghost’ to what has primarily existed as a scientific success story of a cell line. This story has formed a significant part of multi-billion dollar industry of patenting, buying and selling cells. HeLa/Henrietta's resistance to domiciliation/domestication is emphasised and explored further in The Anarchy Cell Line by the artist's action of ‘contaminating’ HeLa cells with her own blood. In a gesture reminiscent of performance art's signature move towards the visceral and the potentially transgressive fluids of the body, this act defies the neat boundaries ordinarily observed within the laboratory environment between the disinterested scientist and the biological object of scientific research. Questions pertaining to gender, race and class relations are arguably marked by, made available in, and invited through Verspaget's documentary text, particularly when she speaks of ‘women as remnants’, of ‘hybridization’ and of ‘the luxury of privileging creative context’. Such concerns are largely absent from Borland's work precisely because her installation does not participate in rituals of production or reception that enact or point towards these relations either through the live event, documentation or both.

Thinking about Verspaget's work in relation to Schneider's reconceptualisation of the archive as act helpfully resituates the artist's description of her act as ‘performative’, in theoretical terms that are more akin to performance and performance theory than to the Austinian or Butlerian performative. Of course, the act of adding blood to the cells might be read in terms of the operation of a certain kind of authority that gains force through repetition and citation, such as the repeated scientific experimentation that is continually performed on these cells and which is authorised by ritualistic scientific procedures that follow current legislation on established cell lines. However, it is the framing of this act as ‘anarchistic domestication’ and as artistic act, which marks it off from all other (scientific) acts involving HeLa cells. The revelation of this act as act is only made possible through the enforcement of the conceptual frame that ensure its legibility as art; as such, Verspaget's act demonstrates, at once, its participation in and challenge to the appropriation of HeLa within the scientific arena. Again, documentary traces of the work play a key role in determining where this frame is located for the spectator who, like me, arrives at the work after the live event has taken place.Footnote 39 Indeed, the ‘live event’, as is sometimes the case in bioart practice, may take place in the privacy of the laboratory or the artist's studio with an audience of one: the artist herself. In the case of Verspaget's work, her documentary text serves to bolster a reading of The Anarchy Cell Line which supports my assertion that biological material in art has the potential to interrogate the archive as an operation of political power over what is given to appear and disappear, although again not in terms of a metaphysics of presence. It is, rather, the relation between the document and the live event – both creating the anarchy cell line and displaying the process or the outcome of that act in the gallery space – which enables the reappearance of what is ordinarily given to disappear inarchival acts of scientific research. What reappears is the memory of Henrietta Lacks, which is disavowed in the storing, use and the making knowable of HeLa as a biological tool within the scientific community.

Although the use of biological materials in art is significant to my argument, then, it is not the ability of these materials to remain that enables the possibility of a flesh memory to challenge the traditional archive. In fact, it is likely that, at a material level, the artist's blood cells would have survived only a limited number of divisions and following the installation the ‘cell line’ would have been discarded for the purposes of health and safety. Rather, it is in the negotiation of materiality that takes place in and through the relationship between the document, the live event(s) and the said biological materials that gives way to a different kind of archival practice. This negotiation does not necessarily depend on object or visible remains, such as bones that persist and only refer back to flesh that once existed.Footnote 40 In this respect, Verspaget's The Anarchy Cell Line facilitates an archival practice that emphasises the process of remembering as an act that need not be bound to savable material remains. Instead, it is an act that reappears in the artist's gesture of adding her own blood to ‘HeLa’ (as that which is irreducible to its material remains) as well as in the spectatorial encounter with that gesture in the gallery space and/or in documentation. Whilst the anarchy cell line, therefore, seemingly disappears in death and in documentation, ‘it’ nevertheless remains in one's encounter with the work. I place this ‘it’ in quotation marks because the anarchy cell line is subject to its own (anarchical) erasure in terms of meaning, by exceeding its possible reduction to either an art object, scientific object, concept or textual signifier in Verspaget's commentary. If we view The Anarchy Cell Line in terms of what Schneider calls ‘ritual repetition’,Footnote 41 we acknowledge the artist's return to HeLa within a scientific context, albeit a return that is marked by difference, as well as the repetitions that guide the spectator's or reader's return to the live event or the document. Such repetitions are ‘ritualistic’ in the sense that they are inevitably scripted by previous encounters with artistic events and documentary texts, just as one's encounter with cellular ‘bodies’ is haunted by previous encounters with other (human and non-human animal) bodies. To view these events, documents and the material presences of the anarchy cell line in terms of this idea of ritual repetition is to address and acknowledge that which scripts, in this case, the availability of a different kind of remembering in this work and its documentary traces.

The spectator potentially recognises Verspaget's act, and the encounter with it, as marked by difference in its repetition, in comparison with more routine uses of HeLa cells. This raises the inevitable question of ethics that is intimately linked with concerns over ownership and authorship of material and immaterial remains in this context. Does Verspaget's use of HeLa cells in this work simply reiterate (or ritually repeat) the kind of intervention at the cellular level that is commonly practised within tissue culture? If so, does this intervention reinscribe the kind of authorship that is ordinarily attributable to the scientist? If we see the act of adding blood to HeLa cells as an attempt at colonisation and as an act that follows the non-consensual use of HeLa cells within the scientific community, then perhaps we may draw such a conclusion. Similarly, if Verspaget's work had a fixed outcome that was available for purchase, then we might observe a parallel between the treatment of HeLa as a scientific and profitable tool and the anarchy cell line as having monetary value as an art object. However, this would significantly contradict the declared intentions of the project, which are given more visibility when one encounters the work through its documentary traces. Furthermore, this reading of the cell line as art object would deny the giving over of the self which is performed in the ‘sacrificial’ extraction of the artist's blood from her body.Footnote 42 I use the term sacrificial here in its etymological sense, as setting something apart (in this case, one's blood from one's body) in order to make it sacred.

I would argue that Verspaget's documentation on this project provokes a response that, for me, is analogous to the (sometimes) visceral experience that I have encountered on seeing sculptures constructed using living tissue within the artistic space, such as those created by the Tissue Culture and Art Project. These experiences during the live event have often resulted in a bodily response; ‘somersaults’ in the stomach or a specific kind of nervous tension in the body, which can be likened to the ‘body to body transmission’ that Schneider observes in the reception of Hodge's bloated corpse. Whilst Verspaget's documentation is less provocative in its invitation to the spectatorial body to respond, the knowledge that the image of ‘heart shaped anarchy cells’Footnote 43 is preceded by a ritual act of adding blood to HeLa cells, gives rise to a different kind of response to that which is encouraged by Borland's piece or Skloot's text. Verspaget's act is remembered in documentation in a way that suggests a cellular body-to-body transmission, but is also felt in the relation between the image and Verspaget's description of the act in terms of abjection and cohabitation. What exactly is being ‘transmitted’ in such encounters is less clear; or, particularly at the time of its occurrence, the transmission is not immediately determinable. This is perhaps where the question of ethics in terms of the reception of bioart (documentary or otherwise) might be located. It is arguably this kind of body-to-body encounter that invites and makes felt the incalculable moment of response to an absolute other, whose alterity cannot be reduced to the knowable or to the self-same but who/that nevertheless demands a response.Footnote 44 The way in which biological material is given to appear in both the artistic space and in documentation here, therefore, references the body but it is also something other than the body.Footnote 45 This body-to-body transmission does remain, through experiences that the logic of the archive would have us determine as either material or immaterial. However, this transmission has the potential to return in its various repetitions in and through the spectatorial body as an archive (which is by no means fixed or final) to the bodies and memories that (both materially and immaterially) haunt the cells which persist.

Henrietta's Tribute?

In 2006, Swiss artist Pierre-Philippe Freymond employed HeLa cells inan artwork also entitled HeLa.Footnote 46 Much like Borland's installation, Freymond's artwork consists of an incubator containing living HeLa cells in nutrient medium and an inverted binocular phase contrast microscope. In addition to this scientific equipment, Freymond includes a black and white photograph of Henrietta Lacks, a lightbox, a neon light displaying the possessive noun Henrietta's, a mural and an A5 booklet. The inclusion of the photograph and the neon light is particularly interesting, since both objects invite a plethora of significations, whether or not the spectator is familiar with the story of Henrietta Lacks. The neon sign, for example, initiates a nostalgic reference to an imaginary 1950s US diner called Henrietta's, whilst at the same time hailing the spectator into a voyeuristic scene in which neon light might ordinarily read ‘ladies, ladies, ladies’. Indeed, the separation of the installation space from the rest of the gallery, at least as it can be seen from the documentary images, readsas the transition from the public to the private world of the voyeur who secretly observes the private life of an unsuspecting other. That Henrietta's cells were removed and used ‘without her knowledge or consent’ takes on a more immediate and potentially uncomfortable resonance in an installation in which HeLa cells are magnified and Lacks' photograph is displayed alongside them in this intimate but nonetheless public exhibition.

In his commentary on the installation, the artist negotiates this public/private aspect of the history of the HeLa cell line and Henrietta Lacks' story, noting a deliberate attempt in the past to hide the name of the person from whom the cell line originates. He writes:

Since the 1950s, HeLa cells [have been] used in medical and biology labs as a reference for in vitro human cell culture in view of developing different treatments, e.g. for polio and for some types of cancer. These cells helped to save a great number of lives. All HeLa cells derive from the same sample taken in 1951 from a Baltimore patient called Henrietta Lacks, whose name was kept secret for a long time. The installation addresses the same post-mortem destiny of this woman whose cells survived and proliferated throughout the world since her death at 31.Footnote 47

Freymond's suggestion that Lacks' identity was intentionally kept out of the public realm is consistent with other accounts concerning the deliberate use of a fictitious name, Helen L., Helen Larson and Helen Lane, in newspaper and magazine articles up to the eventual disclosure ofLacks' real name in 1971.Footnote 48 However, there was also a growing trend in the 1950s – although not a legal obligation – to ensure patient confidentiality through anonymity, which would have served to protect the doctors and the scientists involved in Lacks' treatment and research with HeLa cells, as well as the university, from any unwanted publicity. It was this emerging practice of confidentiality, designed to protect the privacy of both the patient and the patient's family, that paradoxically prevented Lacks' family from knowing that her cells were still alive, despite the media interest around them.Footnote 49

The inclusion of the photograph of Henrietta Lacks in Freymond's installation enacts a particular history by echoing the first time that Lacks' name was made officially public in 1971 alongside her photograph in aco-authored article in a leading scientific journal.Footnote 50 Doctor Howard W. Jones, the gynaecologist who had been involved in Lacks' treatment at Johns Hopkins in the 1950s, along with some of his colleagues, wrote this article on the HeLa cell line as a tribute to George Otto Gey, the scientist whose laboratory had propagated the cells in the first instance. Whilst Freymond's installation employs the very same photograph, its recontextualisation with the cells here reads more like an artistic gesture towards resituating ownership of the cells with Lacks, freeing them and Lacks' image from this scientific tribute. Indeed, the original tribute was (perhaps predictably) not an attempt to record Lacks' contribution to science, but instead it pays homage to the scientist who (although he had not benefited financially from the development of the cell line) had freely shared the cells with his colleagues without the knowledge or consent of either the patient or the patient's family.

To the extent that the artist's text and the documentary images of the installation achieve this recontextualisation of the photograph, Freymond's work challenges the reductive framing of the photograph in Jones' article. In the paper, Jones et al. equate the woman in the photograph with the cell line by publishing it alongside a caption that reads ‘Henrietta Lacks (HeLa)’, as if the cell and the person are one andthe same thing.Footnote 51 Differently, Freymond's installation maintains a conceptual distinction between the cells and the photograph that would reduce the woman to the cell line by placing them next to one another and by not dictating the content of what follows the neon sign ‘Henrietta's’, although the sign does inevitably attribute ownership to Lacks by employing a possessive noun. What exactly is owned by Henrietta is for the spectator to decide (is it Henrietta's image, Henrietta's cell line or Henrietta's story?) and, in that act of decision, the spectator arguably becomes a participant in the act of archiving asproductive of immaterial and perhaps even flesh remains. This open-ended invitation to consider a different kind of history of HeLa and/or the story of Henrietta Lacks is counter to the logocentric attempt of Jones and his colleagues to achieve, as their subtitle describes, ‘AReappraisal of [the HeLa Cell's] Origin’. Freymond's installation, instead, creates a space not only to imagine a different kind of history but to imagine a different kind of archival practice.

Freymond's use of the photograph, much like his use of HeLa cells, however, inevitably participates in the non-consensual and continuous exploitation of Henrietta Lacks' image in the public realm. Ever since her identity was ‘officially’ revealed, this photograph of Lacks has appeared in numerous scientific publications, magazine articles, blogs and even on laboratory walls.Footnote 52 The question still remains, therefore, as to whether the inclusion of the photograph in Freymond's installation reproduces Henrietta Lacks and HeLa as object or challenges the reception of both in such reductive terms. The emphasis on visibility in this work – the spectacle which is evoked by the neon light, the microscope and the mural – certainly repeats the archive's habituation to the ocular. The photograph and the cells, for example, might be received as indices of disappearance as loss rather than as productive of an immaterial remembering that approaches the archive as ‘the repeated act of securing memory’.Footnote 53 The neon sign, in particular, reads almost like a signature, further complicating the questions of ownership and authorship that already haunt these cells and other cell lines that challenge the idea that I am both owner and author of my cells or tissues, once (or even before) they have been removed from the body. However, when the artist discloses that the sign is written in his own handwriting, the ownership and authorship of the cells is problematically, although perhaps unintentionally, assumed by the artist and HeLa cells, and potentially HeLa (as more than just the materiality of these cells), becomes yet another art object.

On the other hand, whilst these objects (the photograph and the HeLa cells) can be read as remains which index what is lost, the inclusion of an A5 booklet and a microscope arguably invite a tactile interaction with the installation that signifies beyond their status as objects. This tangibility has the potential, in turn, to give rise to an embodied engagement and/or an immaterial encounter with the unmarked acts, which both sustain the meaning of these ‘object’ remains and are prompted by the staging of the objects. These acts include the interpretive work of the scientific gaze facilitated by the microscope, or the construction and evocation of memories of flicking through a family album on seeing the black and white photograph of Henrietta Lacks. Unlike Borland's installation, the microscope in Freymond's HeLa invites ‘hands-on’ interaction precisely because it appears alongside other ‘objects’ that encourage tactility and that potentially engage the spectator in the construction of different histories. The notebook invites the spectator to flick through it, the photograph encourages her or him to pick it up, andthe microscope promotes hands-on engagement because, unlike Borland's installation, it is not accompanied by a magnified and guided video representation of that which already appears under the microscope. Of course, such a reading is made available in the documentary images of both Freymond and Borland's work, which may or may not coincide with one's experience of being in the gallery space with these pieces. However, this invitation to participate or not participate in the material presences of these works is echoed, and in the case of Borland's work enacted, in my engagement with their photographic images. The spectacle of the technical equipment in Borland's installation, which can be observed in the widely reproduced image of the work, for example, does not allow for anything other than a two-dimensional relationship with its objects to emerge. The photograph itself encourages me to engage with it as a record of a past event rather than inviting a participatory process of making meaning and this is, indeed, how I imagine the gallery encounter also to unfold. The mise-en-scène of Freymond's images, on the other hand, intentionally points to spectacle as an aesthetic strategy. This is exaggerated in the use of the light box and the neon sign in such a way that arguably permits one's recognition ofthe privilege ordinarily afforded to visuality in more traditional approaches to recording history.

Performing Archive

In 2004, Adrian Heathfield and the Live Art and Development Agency organised a series of conversations and debates which emerged out of, and in response to, the Live Culture programme at Tate Modern (March 2003). During a conversation entitled ‘The Fate of Performance’, art historian Amelia Jones was asked by an audience respondent, in an open floor discussion, to qualify comments that she had made concerning the differences between Mona Hatoum's use of medical imaging technologies and bioartist Eduardo Kac's use of genetic engineering in their respective art practices.Footnote 54 The respondent wondered whether Jones was making an ethical judgement in her claim that ‘there's a vast difference […] between using a medical technology that might be invasive but isn't tinkering with the building blocks of DNA and someone who's actually shifting the parameters of a certain kind of animal life’.Footnote 55 The discussion continued as follows:

Jones: I think you could say that's what interests me about Eduardo Kac is that he begs a lot of frightening ethical questions. I mean, do we have the right to engineer a different kind of bunny rabbit? Personally I would be uncomfortable doing that […]

Respondent: But scientists are doing it every day.

Jones: Of course, well that's what [Kac] is pointing out […] he's making that visible. And yet he's also participating in that. And that to me is a very frightening area. I'm not really making a moral judgement about Eduardo Kac, I'm just saying I think there are major ethical questions there that are not […] it's not the same thing as Mona Hatoum is doing.

Respondent: Would it be interesting if performance writing would address […] the ethical questions that are in the political debate among governments and scientists and ethics commissions?

Jones: I would certainly try to do that if I wrote about Eduardo Kac's work.

This paper initiates a theoretical entry point for performance studies to begin such a dialogue with the biological arts. Tissue culture participates in the archiving of certain bodies and artists are engaging with such archival practices in the context of art and performance as well as in documentary practices that, in turn, reinscribe or challenge those engagements. Performance writing on the archive, therefore, has much to offer a critical examination and appreciation of this area of practice. Jones' comments, here and in Adrian Heathfield's edited book Live: Art and Performance, arguably echo a dominant tendency within the fields of art history and performance studies to (intentionally or unintentionally) write bioart practices out of the art historical/contemporary performance canon or at least to sustain bioart's position at the margins of critical analysis. As Jones writes, ‘[a]s much as I want to restrain my knee-jerk (bone against flesh) reaction to such projects, I have to admit I find them terrifying’Footnote 56 and yet it is this (very bodily) knee-jerk reaction that arguably informs and is repeated in her decision not to write about Kac's work. Perhaps in thinking the archive as an act that gives bones to remain and flesh (and performance) to disappear, we might instead acknowledge our own participation in the archive as ‘a particular social power over memory’, one that ‘ritually repeats’ these knee-jerk reactions that resist or ignore the potential of flesh to ‘push back’.Footnote 57 As the use of biological material in art practice necessarily raises ethical questions, perhaps the most ethical response is to acknowledge the otherness in which bioart practices participate: within the acts of receiving as well as producing bioart. Indeed, despite repeated attempts in the academy to give bioart to disappear(ance), these bodily responses (bone against flesh, flesh against bone) will still remain and, like HeLa and Henrietta, will (and perhaps should) always return to haunt us.

Notes

For more on the uses of HeLa cells in science, see Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (London: Pan Macmillan, 2010), pp. 93–98, 100–02, 137–38.

By using this term, I wish to reaffirm its meaning in this context in relation to the etymological origin of ‘reminiscence’ as an ‘act or process of remembering’. Regardless of whether these living or biological objects are encountered in the flesh or not, it is my suggestion that the acts of reception that are specific to and encouraged by performance are remembered by and brought to bear on them.

Rebecca Schneider, ‘Archives: Performance Remains’, Performance Research, 6 (Summer 2001), 100–08, (p.101).

Ibid.

Rebecca Skloot, The Immortal Life, p. 9.

Schneider, Performance Remains, p. 102.

L. Hayflick and P. S. Moorhead, ‘The Serial Cultivation of Human Diploid Cell Strains’, Experimental Cell Research, 25 (Spring 1961), 585–621 (p. 586).

Ibid.

For a discussion of both the cultural and the scientific nuances of immortality in relation to Lacks, the HeLa cell line, and the science of tissue culture, see Hannah Landecker, ‘Immortality, In Vitro: A History of the HeLa Cell Line’, in Biotechnology and Culture: Bodies, Anxieties, Ethics, ed. by Paul E. Brodwin (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), pp. 53–72.

HeLa cells contain an active form of the enzyme telomerase that prevents the shortening of telomeres. These are the ends of chromosomes which protect the chromosome from deteriorating. The shortening of telomeres is associated with aging and death. See Skloot, The Immortal Life, p. 217.

See, for example, Landecker, ‘Immortality, In Vitro’, pp. 53–72.

Skloot, The Immortal Life, p. 6.

For more on the ethical and legal issues around the use and storage of human tissue for medical and scientific research in the US context see Skloot, The Immortal Life, pp. 357–58. See also Edwin Richard Gold, Body Parts: Property Rights and the Ownership of Human Biological Materials (Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1996); Lori Andrews and Dorothy Nelkin, Body Bazaar: The Market for Human Tissue in the Biotechnology Age (New York: Crown Publishers, 2001); and Robert F. Weir and Robert S. Olick, The Stored Tissue Issue: Biomedical Research, Ethics, and Law in the Era of Genomic Medicine (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004). Within the UK context The Human Tissue Act (2004) and The Human Tissue (Scotland) Act (2006) legislate on the removal, storage, use and disposal of human tissue and a concise outline of the current regulations can be found in Jane Lynch ‘Consent and Removal of Tissue’ in Consent to Treatment (Oxford, UK: Radcliffe Publishing, 2011). For the wider European context see Christian Lenk, Nils Hoppe, Katharina Beier and Claudia Wisemann (eds.), Human and Tissue Research: A European Perspective on the Ethical and Legal Challenges (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). For a comparison of UK and US tissue practices see Catherine Waldby and Robert Mitchell, Tissue Economies: Blood, Organs and Cell Lines in Late Capitalism (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2006).

Schneider, Performance Remains, p. 102.

Skloot writes that Lacks' name was deliberately withheld from the media until 1971 by the scientists involved in the establishment of the HeLa cell line and the author herself recalls being asked by an earlier editor of the book to write out the stories of Lacks' family. See Skloot, The Immortal Life, pp. 7, 105–09.

CAE take issue with the categorisation of their work as bioart because they suggest, as a genre, it has often served as a public relations exercise for the corporate world. For CAE's objection to the term ‘bioart’, see Steve Kurtz in Natasha Vita-More, ‘Brave BioArt 2: Shedding the Bio, Amassing the Nano, and Cultivating Posthuman Life’, Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research, 5 (September 2007), 171–86 (p. 178). I employ the term bioart or the biological arts for the sake of brevity and do so following an established body of literature that has employed these terms to describe artistic practices that use the tools and techniques of biotechnology in the name of art and artistic research rather than serving the agenda of the corporate world. See, for instance, Natasha Vita-More, Brave BioArt; Eduardo Kac, Signs of Life: Bio Art and Beyond, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2007); and Jens Hauser, ‘Bio Art – Taxonomy of an Etymological Monster’ in Hybrid – Living in Paradox: Ars Electronica 2005, ed. by Christine Schöpf and Gerfried Stocker (New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2005), p. 182–88 or online at: http://90.146.8.18/en/archives/festival_archive/festival_catalogs/festival_artikel.asp?iProjectID=13286 [accessed 22 October 2010].

David Barrett, ‘Wonderful: Arnolfini, Bristol, and Touring’, Art Monthly, 275(April, 2004), http://www.royaljellyfactory.com/davidbarrett/articles/artmonthly/am-wonderful.htm [accessed 30 November 2010].

Ibid.

See, for example, Kate Kellogg, ‘Exhibition Shows How Effects of Life Sciences Permeate Society’, The University Record, 23 April 2001, http://www.ur.umich.edu/0001/Apr23_01/2.htm [accessed 30 November 2010].

Ian Berry (ed.), Paradise Now: Picturing the Genetic Revolution, (New York: Tang Teaching Museum 2001), p. 42.

See, for example, Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology, trans. by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976).

Schneider, Performance Remains, p. 102.

See, for example, José Esteban Muñoz, ‘Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts’, Women and Performance: Journal of Feminist Theory, 8 (January, 1996) 5–16; and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Destinations Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance (London and New York: Routledge, 1993), p. 146.

Jacques Le Goff, History and Memory (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992) p. xvii. Quoted in Schneider, Performance Remains, p. 100.

Mary Edsall and Catherine Johnson cited in Schneider, Performance Remains, p. 101.

Schneider, Performance Remains, p. 101.

Ibid., p. 102.

Ibid., p. 105. Emphasis in original.

Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. by Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), p. 2.

Ibid., p. 4, n. 1.

Schneider, Performance Remains, p. 101.

Ibid., p. 104.

Cynthia Verspaget, ‘i am a bioartist’, a minima, 18 (nd), n.p, http://aminima.net/wp/?p=828&language=en [accessed 30 November 2010]. The Anarchy Cell Line was also exhibited as an installation piece at the Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery in 2004 at the University of Western Australia in Perth, Australia. See also, Cynthia Verspaget, ‘The Anarchy Cell Line 2004’, http://members.westnet.com.au/moth/t_art/antext.htm [accessed 30 November 2010].

Skloot, The Immortal Life, pp. 152–57. For the scientific paper that first drew attention to this contamination, see Stanley Gartler, ‘Apparent HeLa Cell Contamination of Human Heteroploid Cell Lines’, Nature, 217 (February 1968), 750–51.

Leigh M. Van Valen and Virginia C. Maiorana, ‘HeLa, A New Microbial Species’, Evolutionary Theory, 10 (December 1991), 71–74. Van Valen's naming of HeLa as the new species ‘Helacyton gartleri’ retains the original cell line name and the Greek word for cell, which is cyton, and combines it with gartleri in honour of Stanley Gartler, who was the first scientist to identify the widespread contamination.

Verspaget, i am a bioartist.

The contamination of other cell cultures with HeLa cells, even across laboratories in different countries, has been attributed to the transferral of the cells on shoes, clothes and even air droplets. See Skloot, The Immortal Life, p. 153.

My interpretation of the ‘live event’ is inevitably shaped by the way in which its material presences are framed and described by the artist. Whereas it is not always the case that documentary images and texts refer to events that have actually taken place, the documents used here are not questioned in relation to their faithfulness to the event (see Adele Senior, ‘Bioart in the Making: Aesthetics, Ethics and Politics in the Tissue Culture and Art Project’, unpublished Ph.D. thesis, 2010). It is, rather, the way in which the documentation invites, or does not invite, a material and immaterial engagement that I am concerned with here. Furthermore, this is an engagement with the work and not simply with the live event in the gallery space. For example, I am interested in live events which precede it, such as the act of adding the blood to the cell line prior to the artwork occurring in the gallery space.

Schneider, Performance Remains, p. 105.

Ibid.

My acknowledgement of the sacrificial nature of drawing blood within Verspaget's practice recognises the potential association of this act with the sacrificial use of blood within performance art practice. See, for example, Dawn Perlmutter ‘The Sacrificial Aesthetic: Blood Rituals from Art to Murder’, Anthropoetics, 5 (Autumn 1999, Winter 2000), http://www.anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap0502/blood.htm [accessed 30 November 2010]. For an analysis of the potential of biological material in bioart practice to become sacred and to only ever exist in ritual, see Adele Senior, ‘Towards a (Semi-)Discourse of the Semi-Living: The Undecidability of Life Exposed to Death’, Technoetic Arts, 5 (April 2007), 97–112.

Verspaget, The Anarchy Cell Line, no page.

Emmanuel Lévinas, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, trans. by Alphonso Lingis (Pittsburgh: Duquesne, 1969). Jacques Derrida, The Gift of Death, trans. by David Wills, (Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 1995).

Whether the body that it references is human, animal or both is a question that is central to a discussion concerning the kind of ethical dialogue bioart is able to facilitate. Such a discussion, however, is beyond the scope of this article.

Pierre-Philippe Freymond, ‘HeLa, 2006’, http://www.freymond.info/htmlfiles/anglais/works/hela_txt.html [accessed 30 November 2010].

Ibid.

Skloot, The Immortal Life, pp. 105–09.

Ibid.

Howard W. Jones, Victor A. McKusick, Peter S. Harper and Kuang-Dong Wuu, ‘After Office Hours: The HeLa Cell and a Reappraisal of its Origin’, Obstetrics and Gynecology, 38 (December 1971), 945–49.

Landecker, Immortality in Vitro, p. 59.

Skloot, The Immortal Life, p. 1.

Schneider, Performance Remains, p. 105.

Amelia Jones and Adrian Heathfield, ‘The Fate of Performance’, Activations, Tate Modern (October, 2004) http://channel.tate.org.uk/media/26610219001 [accessed 30 November 2010]. I would like to thank Amelia Jones for her permission to transcribe and reproduce this conversation here.

Ibid.

Amelia Jones, ‘Working the Flesh: A Meditation in Nine Movements’, Live: Art and Performance, ed. by Adrian Heathfield (London: Tate Publishing, 2004), pp. 132–43 (p. 137).

Schneider, Performance Remains, pp. 102, 105, 104.