Introduction

On Thursday 18 September 2014, the people of Scotland voted to remain part of the United Kingdom by the unexpectedly wide margin of 55 to 45%.Footnote1 In the highest percentage turnout of eligible voters for any UK poll in decades, over three and a half million people expressed their view on the ballot paper. As the results filtered through overnight, many stayed up into the early hours, watching in nervous anticipation as the 32 regions announced their totals one by one. Hundreds of thousands of people had been actively involved in the campaign and were heavily invested in the outcome. For our own part, we are both supporters of national self-determination and voted Yes. In the lead-up to the referendum, Laura was involved in a range of activities with the National Collective (‘the non-party movement for artists and creatives who support Scottish independence’)Footnote2 and David was working at The Arches arts centre in Glasgow with the pro-independence playwright Rob Drummond to direct Wallace – a work-in-development commissioned by the National Theatre of Great Britain in response to the referendum.Footnote3 Several months later, we are coming to terms with the potential opportunities and benefits of remaining part of the UK and hoping that some of our egalitarian aspirations as Yes voters can still be realised.

At the culmination of the Early Days Referendum Festival at The Arches, following the final performance of Wallace, we joined hundreds of people who came together at The Arches Political Party to convivially pass the time until the first results were broadcast.Footnote4 The festival was named after Scottish writer and artist Alasdair Gray’s call (paraphrased from the Canadian poet Dennis Lee) to ‘work as if you live in the early days of a better nation’, and this spirit of nation-building and communal progress framed the programme of events. The following morning, with the No vote confirmed, these ideals seemed to have been abruptly cut short and, perhaps unsurprisingly, far fewer of us returned to the What Now? brunch event to make sense of the final verdict. Here, with a coffee, a bacon roll, and a potato scone, we reflected on a uniquely theatrical build-up to the day of Scotland’s momentous decision. In this co-authored essay, we attempt to recreate that conversation and look forward to a new era of politically engaged theatre and performance. In the lead-up to the 2015 UK General Election, we also want to explore the particular circumstances that led to an 85% turnout in a country with a renewed interest in democratic politics. We believe that it is reductive to suggest that such a passionate and engaged electorate emerged from the divisive condition of a Yes/No debate. Rather, as we aim to demonstrate, the referendum acted as a catalyst for a new politics to emerge that is characterised by creativity, dialogue, and performance. Accordingly, the range of positions and arguments explored through performance go far beyond the question of whether Scotland should be an independent country to address wider issues of decentred and devolved power, democratic processes, and civic political engagement.

Although we were disappointed not to get the result that we wanted, we feel invigorated by the national agency of a large-scale democratic process, and intrigued by the role that theatre and performance played in the referendum. With almost half of the voting population of Scotland supporting independence, after a grassroots campaign that encouraged swathes of disenfranchised voters to engage with national politics (notably, the four districts that voted for independence were, proportionately, the poorest in Scotland), the result has not been as ‘decisive’ as the leaders of the major UK parties have claimed, and the move towards change is still very strong.Footnote5 Many have stated that ‘Scotland will never be the same again’.Footnote6 It therefore seems timely to chart some of the creative responses to the events of 18 September, as well as its political repercussions, as Scotland continues to negotiate and understand its decision. After all, as Jen Harvie points out, ‘national identities are neither biologically nor territorially given; rather, they are creatively produced or staged’.Footnote7 We are therefore interested in the variety of ways that the independence debate was ‘staged’ in 2014. Our aim is to present a snapshot of the range of performative events that took place in the run-up to the referendum, and, as we did over brunch on that bleak morning in September, to ask ‘What now?’ for performance, for politics, and for Scotland.

Creative Participation

On 5 August 2014, then Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond and, leader of the Better Together campaign, Alistair Darling stood on the Athenaeum stage of the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS) in front of a studio audience of 350 Yes, No, and Undecided voters. Using the RCS stage as the site for this televised debate meant that the drama of the political dispute was, seemingly without irony, located in an actual theatre venue.Footnote8 With 1.2 million viewers, the exchange was heated, antagonistic, and widely criticised as a nation watched ‘two rather similar men in background, age and views, shouting at each other and interrupting each other, with little respect for the bigger issues’.Footnote9 While Stephen Coleman warns against nostalgia for days before ‘the sensationalised politics of a political culture dominated by soundbites, spin doctors and CNN’,Footnote10 he also acknowledges the validity of a critical position against ‘the stage-managed nature of so much of contemporary politics, of which the great televised leaders’ encounters seem to be symbolic’.Footnote11 This staged debate failed to connect to the creativity, innovation, and enthusiasm that defined the referendum elsewhere.

In stark contrast to the debate at the RCS, the surge of grassroots movements and political gatherings responding to the issue of independence in the lead-up to the referendum was, in our experience, unprecedented. With emergent groups such as National Collective, the Radical Independence Campaign (RIC),Footnote12 Women for Independence,Footnote13 and the Common Weal,Footnote14 to name but a few, galvanising groups of people around affinity, community, common interests, and goals, the campaign period has had an immensely positive effect on Scotland’s political landscape which shows no sign of abating. These groups used music, spoken word, performance, and film as ways of creatively responding to the debate beyond the typical media focus on the ‘central belt’.Footnote15 If Salmond and Darling’s RCS debate can be considered a ‘stage-managed’ version of the referendum, these alternative creative responses might be understood as a more progressive, community-based, and democratic form of performance. As Richard Schechner suggests, ‘any behaviour, event, action, or thing can be studied “as” performance’,Footnote16 and the activity and engagement that occurred in village halls and communities all over Scotland can be productively framed as performative responses to the debate that escalated in the lead-up to the vote on 18 September. This wide range of community-generated activity is exemplary of Mikhail Bakhtin’s arguments for the ‘democratic cultural expression’ that is engendered by carnivals and festivals.Footnote17 However, the performances of the referendum escape the boundaries of Bakhtin’s ‘democratic’ festivities, which are all too easily managed and controlled by the State. These emerging performances of politics arguably generated far more appropriate conditions for the democratic expression of a national debate, although we later consider the potential exclusions that resulted from these cultural responses.

In the months prior to the vote on Scottish Independence, there was a huge number of discursive events dedicated to exploring the issues around the referendum. Laura’s personal itinerary included, for example, a February event at The Arches, co-hosted by Young Scot and The Sunday Herald (which came out in support of independence a number of weeks later – the only one of Scotland’s 37 newspapers to do so).Footnote18 This event was targeted at 16–24-year-olds, was hosted by Vic Galloway, and featured a panel including rapper Solareye from Stanley Odd; Dave Clarke of Soma; James Reekie, vice-chair of the Conservative Party in Scotland; and 16-year-old Saffron Dickson of RIC, as well as other representatives of the young Scottish electorate voting for the first time. In July, also at The Arches, Laura attended the Festival of the Common Weal – a large-scale, family-friendly festival organised in association with the Jimmy Reid foundation, with nearly 900 people in attendance.Footnote19 Many events like this had a similar format with speakers, musicians, performances and films, spoken word, and discussion, but the Festival of the Common Weal – whose motto ‘All of Us First’ acts as a rebuff to the ‘Me-First’ politics that they argue dominate the current political landscapeFootnote20 – aimed to diversify this format with a family area, an art area, and focussed discussions exploring detailed aspects of the debate. A few weeks later, Independence Blethers was held, a small local event in Milngavie, primarily for women but open to all, with attendees of different ages and genders.Footnote21 Over a cup of tea and Independence-themed baked goods (the ‘scones of destiny’ were a favourite) female speakers offered comments on business, the National Health Service (NHS), and the economy, amongst other things. This small-scale, grassroots event was typical of the mobilisation of communities (and often women in communities) to encourage debate and conversation around the referendum.Footnote22 Between June and August, this played out on a wider scale as the National Collective took their crowd-funded Yestival: The Summer of Independence tour all over Scotland – from Sanquar to Shetland.Footnote23

As well as standard electoral behaviours such as canvasing and public meetings, the referendum provoked a number of other embodied and creative ways of engaging in the debate and performing affiliations via social media. While both campaigns utilised online networks, the Yes campaign had far higher levels of activity than their No counterparts.Footnote24 Community groups posed with Yes signs in various parts of the country; people draped themselves in Yes banners and flags on tops of hills, by lochs, by the sea, and in city centres. Yes badges and T-shirts allowed politics to be worn literally on the sleeve. In Spain, holiday-makers wrote Yes in the sand on the beach and posted images on social media sites – an alternative/politicised holiday snap demonstrating a political affirmation marked on the land of another nation (until a big wave comes along). Throughout the lead-up to the referendum, comparisons were being made between Scotland and Catalonia, with Paul Mason of the Guardian describing both nations as ‘straws in the wind’ for wider resistance to the global ‘economic consensus’.Footnote25 The date 11 September 2014 marked the 300th anniversary of Catalonia’s loss of independence, and the Catalan people watched events in Scotland closely, considering how the outcome might influence the course of events leading up to their own referendum on 9 November. There were, of course, important differences between the two contexts: in Catalonia, the poll was not legally binding and could have no constitutional outcome. Consequently, there was also no Catalan equivalent to the Better Together campaign. Still, the sense of kinship between the Scottish and Catalan situations was demonstrated performatively: large-scale public events in support of Scottish independence took place in Catalonia in the lead-up to 18 September, and on 17 September the Catalan flag was created from candles in Glasgow’s George Square to demonstrate support for the Catalan people’s pleas for independence.

Elsewhere in Scotland, whole sides of houses were emblazoned with the word Yes to attract the attention of passersby – the building performing the politics of the people who live there. Yes was written in 20-foot letters on the ground as whole communities gathered and were photographed – an aerial illustration of the number of people who wanted to unite around the word and what it promised. Farmers mowed Yes in their fields to be seen from a distance, while neighbouring farmers painted No on their sheep. One week before the referendum, over 100 Labour Members of Parliament (MPs) arrived in Glasgow from London to demonstrate their commitment to the No Thanks campaign. The politicians were accompanied up Buchanan Street by the activist Matt Lygate on a rickshaw playing ‘The Imperial March’ from Star Wars while announcing via megaphone: ‘People of Glasgow! Your Imperial Masters have arrived!’ This comedic demonisation of the visiting politicians demonstrates attitudes towards the enactments of power, dominance, and bias from Westminster, and what should have been a grand gesture from the Labour party was undercut and subverted by a moment of street performance. Actions such as this are small and simple, but they were happening everywhere. The documents of these embodied acts – provoked by the political debate and by the desire to find ways of communicating opinion – were widely disseminated using Facebook and Twitter as prominent contemporary sites for performances of political discussion and debate.

Alongside the smaller-scale, everyday performances of the referendum, a number of more explicitly theatrical events took place in arts venues across the country. These plays and performances responded to, and generated, creative and intellectual engagement with the independence debate, frequently demonstrating what might be called ‘early-days thinking’; imagining a better nation or speculating on how Scotland might achieve a more progressive politics. At the 2014 Edinburgh Festival Fringe, various events explicitly tackled the referendum, including David Greig’s All Back to Bowie’s (a ‘mix of politics, poetry, polemic and pop’Footnote26 ), as well as the National Collective Presents…,Footnote27 MacBraveheart: The Other Scottish Play,Footnote28 Now’s The Hour by Scottish Youth Theatre,Footnote29 and Erich McElroy’s The British Referendum.Footnote30 On the evening before the referendum, the final performance of Davey Anderson and Gary McNair’s How to Choose? tour, part of the Early Days festival, focussed less directly on the Yes/No debate, instead including perspectives from philosophers, neuroscientists, and economists to reflect on human processes of decision making.Footnote31 While Christine Hamilton points out that many of the artists involved in the debate supported independence, and that ‘there [was] less active engagement by [artists who oppose it]’, most of the theatre that responded to the referendum avoided an explicit allegiance with either side – apparently so as to hold the issues open for continued debate.Footnote32 There are notable exceptions, however. In the late David MacLennan’s contribution to the National Theatre of Scotland’s Great Yes, No, Don’t Know Five Minute Theatre Show, the veteran playwright/producer expressed his doubts about what independence could do to change Scotland.Footnote33 In 2013, Tim Price’s I’m With the Band used the metaphor of a dispute between four band members from Scotland, England, Wales, and Northern Ireland to show how much stronger they were together.Footnote34 Conversely, David Hayman’s one-man show The Pitiless Storm, by Chris Dolan,Footnote35 and Alan Bissett’s The Pure, the Dead and the Brilliant, made impassioned cases for independence.Footnote36 Funded by members of the public, Bissett’s production drew humorously on Scottish myth and folklore as bogles, demons, and selkies, led by a banshee played by Glaswegian actress Elaine C. Smith, demonstrated the doom-laden future after a ‘No’ vote.

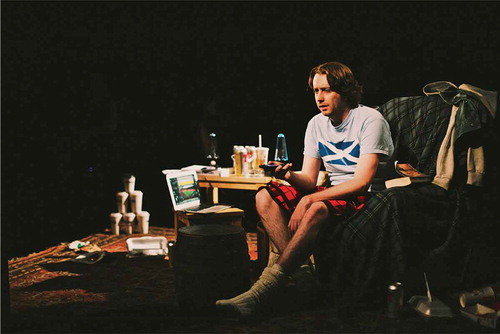

Rob Drummond’s Wallace positioned itself somewhere between these more polemical productions, although it is more easily read as pro- rather than anti-independence. The play is in three acts, each responding respectively to the political, historical, and personal context of the referendum. ‘Political’ Act I takes place during a live TV debate, featuring a panel of politicians, a journalist, and a comedian. The debate, which includes unsolicited questions and comments from the audience and several audience polls, is interrupted by Wallace Williamson, an ardent nationalist and writer of historical fiction, played by Drummond. Wallace embarrasses himself when asked by Tory MP Sir Edward Hammer to justify his position on independence, and finally storms off set after it is revealed that he has unwittingly sacrificed his vote by failing to realise that he needed to register. ‘Historical’ Act II suddenly and unexpectedly shifts the action to the story in Wallace’s book – a meeting in a farmhouse on the border between Scotland and England. The actors change character to their thirteenth-century counterparts as Edward I (‘the hammer of the Scots’) meets John Balliol and Robert the Bruce to demand Scotland’s feudal submission to the throne of England. After an interval, in ‘Personal’ Act III, alone in his Partick flat, Wallace reflects on his disastrous television appearance. Through a series of phone calls, he ruminates on the nature of democracy and independence and attempts to corner Hammer into an apology. Together, these genre-shifting sections of the play attempt to acknowledge, and respond to, the multiplicity of arguments, opinions, and questions that constituted the independence debate.

Image 1 Rob Drummond as Wallace Williamson in his play Wallace. The Arches, Glasgow, September 2014. Photograph by Niall Webster, courtesy of The Arches.

While the performances of Wallace were primarily scripted and rehearsed, like many of the artistic events that responded to the referendum, it included an audience debate. Although this was theatrically framed (as with much of Drummond’s work, spectators were cast in a ‘role’ – that of a passionate audience at a live television debate), the aim was to give the audience a significant voice in the exposition of the drama. This required a forthcoming, engaged audience (‘this really won’t work without your help’, the chairwoman entreats at the start of the debate), and in the charged atmosphere of the week of the referendum, this seemed like a realistic possibility. This first section of the play was demanding on the actors, who were required to be well-informed about the unfolding arguments and events of the independence debate, and to deploy this expertise, in character, without knowing what the audience would ask. Tensions were running high, and occasionally it seemed that the boundaries between fiction and reality were breaking down as some audience members directed their anger and frustration towards the performers. Perhaps it was testament to their skills as improvisers that they so convincingly portrayed their characters that audiences seemed to forget they were actors, not politicians. Or perhaps people simply needed someone to whom they could vent their disappointment with the real politicians, playing out their own drama on a larger stage. At any rate, when these sections of the play worked as well as was hoped (and this was not always the case), their power seemed to lie in the play’s ability to tap into the hunger for argument and discussion that The Arches’ audiences brought into the theatre that week.

Wallace, along with many other performances, demonstrated the desire to open up a space for dialogue and debate. Indeed, one could argue that the referendum became a catalyst for a large-scale relational aesthetic to emerge.Footnote37 For Nicolas Bourriaud, theatre is limited as a relational artform because, unlike exhibition-based relational art, such performances bring together ‘small groups’ of people ‘before specific, unmistakable images’, offering no opportunity for live discussion during the event.Footnote38 Yet the theatrical events of the referendum counter this questionable position, not only by demonstrating the potential for theatre to respond in the moment to the political context of its performance, but also because of the range of talks, symposia, meals, and parties that were programmed as part of the festivals that contextualised the more tightly scripted theatre events. The communal and convivial nature of many of these events resembled Bourriaud’s ‘micro-utopias’ – artistically constructed relational spaces which aim to ‘give everyone their chance’.Footnote39

Bourriaud’s aesthetic model has been heavily criticised for operating ‘too comfortably within an ideal of subjectivity as whole, and of community as imminent togetherness’.Footnote40 Such claims of ‘democracy’ are problematic when attention is turned to the institutional, cultural, and social boundaries of the environments that relational art often takes place within; the exclusions and antagonisms that are obscured by aspirations of ‘link[ing] individuals and human groups together’.Footnote41 Yet the performances of the referendum moved beyond the micro-utopianism of Bourriaud’s art galleries, connecting to a wider national debate and offering a space for opposing ideas and values to co-exist through ‘live discussion’. As Harvie argues, artistic practice is ‘never only abstract ideas but always also material practice enacted in – and constituted by and constituting – networks of social relations’.Footnote42 The Arches’ Early Days Festival, for example, was programmed in response to, and as an important extension of, Wallace. Through a ‘series of performances, conversations, art and music’ audiences were encouraged to ‘think about how we make decisions, where the human desire for independence comes from, and whether it even really matters’.Footnote43 The theatre of the referendum prompted these national conversations, but often it was also constituted through them, as debate and ‘live discussion’ emerged in the moment, using performance as a relational framework to examine the arguments and consider the implications of our decision. Nonetheless, as Claire Bishop points out, it is important to ask, as Bourriaud fails to do, ‘what types of relations are being produced, for whom, and why?’Footnote44 On one hand, the explicit political agenda of the referendum performances led to a very open acknowledgement of antagonisms and disagreements. On the other, in any socially constructed group there are always voices that are silenced and people who are excluded.

Performing Democracy

Writing on the formation of society and the place of the individual within the group, Félix Guattari observes a ‘minefield, with questioners hidden in fortified dug-outs waiting to attack you’.Footnote45 As artists and cultural commentators who have spent the last year grappling with the ostensibly divisive issue of Scottish independence, we sensed the presence of these critical voices at every turn. In some instances, these voices were so loud that they inevitably silenced others. As Guattari notes, whenever particular ideas or solutions are put forward that directly advocate change to the circumstances of the present day, there will be ‘systematic’ attempts ‘to restrict any approach to these problems that is remotely ambitious’.Footnote46 Conversely, though, anecdotal evidence suggests that the heavily pro-independence voice of the Scottish arts community may have obscured the opinions of those within it who were less committed, or directly opposed, to independence. In such cases, staying quiet may have resulted from a reluctance to subject oneself to the battlefield of political opinion. Inevitably, as we develop any sense of subjectivity on the issue of Scottish independence, like Guattari, we find ourselves ‘at the crossroads of multiple components, each relatively autonomous from each other, and, if need be, in open conflict’.Footnote47 Engaging with the ‘conflict’ of the debate has revealed a complex range of positions and arguments, many of which exist in open tension with one another. This has the potential to result in inhibition and silence on an issue as important as large-scale political change.

In this climate of political tension, some arts festivals and venues sought explicitly to avoid taking any position on the question of Scottish independence. In August 2013, looking ahead to the 2014 Edinburgh International Festival (EIF), its director Jonathan Mills notoriously stated that his ‘planning hasn’t coincided with or been influenced by that event’ and that he was ‘not anticipating anything in the programme at all’ that would speak to it.Footnote48 However, if Mills was attempting to quarantine the arts from politics, his inadvertent legacy was ‘to make 2014 the most political festival yet’, by helping to provoke a myriad of referendum-focused plays at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.Footnote49 Moreover, despite his own perplexing embargo, Mills eventually presented Rona Munro’s trilogy of James PlaysFootnote50 as a central part of the EIF’s 2014 programme. Providing further evidence of what Trish Reid identifies as ‘a resurgence of the history play in Scotland’,Footnote51 Munro’s new play cycle deals with the stories of three generations of fifteenth-century Stewart Kings. Rather than addressing the referendum directly, it provides what Observer critic Susannah Clapp described as ‘a tacit rather than explicit argument about Scottish independence’.Footnote52 And while it is perhaps significant that, as a high-profile co-production between the National Theatre of Great Britain and the National Theatre of Scotland, the James Plays explored national identity at a relatively safe historical distance, their lack of contemporary political specificity also allowed the production to find continuing relevance in its subsequent, post-referendum run in London (where Munro earned the Evening Standard award for best play of the year), as well as increasing the potential for international touring. Like many other contemporary Scottish history plays, including David Greig’s Dunsinane (2010) and the second act of Wallace, The James Plays explore issues of power, governance, and sovereignty that are clearly of direct relevance to the current political situation. However, if Jonathan Mills hoped that programming Munro’s work would act to mitigate the storm of complaint that his 2013 comments had attracted, he was sadly mistaken. Many artists and cultural commentators continued to take him to task for not addressing the referendum more explicitly through his programme.

If Mills’s response to the referendum was to attempt to steer clear of the ‘fortified dug-outs’ in Guattari’s ‘minefield’, the more common response in the Scottish theatre community was to head bravely straight for them. By creating spaces for dissensual debate, artists, companies, and festivals made a vital contribution to the wider political conversation. As Greig suggested, ‘the independence debate allows us to explore every aspect of our national life and ask ourselves the question – “does it have to be like this?”’Footnote53 Perhaps this is why theatre and performance proved so ready and able to respond to the referendum – a phenomenon that persisted right up to (and beyond) the day of the referendum itself. After a successful run at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, Bissett’s The Pure, the Dead and the Brilliant was re-staged at Glasgow’s Tron Theatre on the evening of 18 September, while at the other end of Argyle Street, Wallace was being performed at The Arches. The decision of these venues to have these works performed on the night of the referendum made a clear argument for the value of performance in framing, explicating, and defining political moments. At The Arches, David watched what he considered to be the most successful and lively performance of Wallace in its week-long run. At the Tron, sitting in the packed auditorium, Laura found the resonances of Bissett’s play took on a heightened sense of meaning and significance due to the timing of the event. One of its lead performers, Elaine C. Smith, had been a prominent campaigner for the Yes movement and had represented pro-independence views on televised debates and at political meetings in the months leading up to the referendum. Smith’s journey from actress to political spokesperson back to actress, as well as Bissett’s impassioned political speech at the end of the performance – in which he outlined the continued action and engagement needed in the event of both a yes and a no vote – blurred the boundaries between politics and performance (and, indeed, art and life). At the play’s climax, the audience were asked to ‘vote’ using their programmes – publicly re-performing an action that most (probably all) of them had undertaken in the privacy of the polling booth earlier that day. As expected, the theatre audience of the Tron said ‘Yes’, and the atmosphere was electric and jubilant.

The enactment of voting within The Pure, the Dead and the Brilliant, and the polling of audience members in the ‘Political’ Act of Wallace, perhaps recalled the use of ‘snap polls’ following events such as the Salmond–Darling debate at the RCS.Footnote54 Yet Wallace also satirically undermined the value of opinion polls, which ‘only record the views of those people too stupid to avoid a guy in the street with a clipboard’. Focusing finally, in its third act, on the troubled ruminations of an individual voter (as opposed to the relentless recourse to measurable statistics that dominated both sides of the campaign), Wallace attempted to dramatise a sense of the ‘tacit narratives’ which Coleman argues are crucial to any understanding of the ‘social performances’ of voting.Footnote55 For Coleman, ‘these less tangible, quantifiable or even rationally explicable flows of affect are no less characteristic of democracy as it is experienced than exit polls, swings and vote-seat ratios’.Footnote56 The performances of the referendum had particular value in this sense, as cultural spaces where the ‘flows of affect’ on display were oriented less towards measurable outcomes than towards the ongoing process of telling political stories, engaging in political debate, and asking political questions.

Conclusion

It remains to be seen whether the referendum on Scottish Independence has permanently transformed politics in the country, but it is certainly the case that popular engagement with grassroots campaigns, political parties, and community groups remains far higher than prior to the referendum campaign. In this essay, as we have engaged with some of the performances and events that have contributed to this changing political landscape, we have gestured towards the wider role that performance can play in relation to large-scale political events. In identifying some of the ways in which the independence referendum was ‘played out’, we hope to have captured something of the spirit of the debate in Scotland. We consider this to have been a hugely progressive, creative, and formative period in Scottish politics, in which theatre and performance played significant roles.

Of course, when performance positions itself as ‘political’, it is often those who are already interested and engaged with the issues at hand, and already agree with the politics of a given work, who will attend – rather than those whose views might actually be challenged or reconsidered. Judging by some of the audience responses to The Pure, the Dead, and the Brilliant, and indeed to Wallace, the majority of those in attendance had long since firmly decided their allegiance. The suggestion that theatre can function as a political apparatus might thus be considered limited in this sense. However, the role of professional performance as a site where debate and dialogue could occur, and where both Yes and No positions could be tried on for size, was important in confirming and affirming people’s views. So too were the everyday activities – conversations in shops and pubs, the wearing of badges and stickers, mass gatherings in George Square – that Schechner argues we can analyse ‘as’ performance. For Bishop, the paradox of art is that it is ‘perceived both as too removed from the real world and yet as the only space from which it is possible to experiment’.Footnote57 Art must therefore ‘remain autonomous in order to initiate or achieve a model for social change’Footnote58 In this sense, the performances of the referendum had a particular value in creating autonomous relational spaces for participants to rehearse and formulate their individual politics.

The performance and art scene in Scotland engaged with, and contributed directly to, a palpable energy and appetite for change, and a growing recognition of the possibility of taking the first step to creating a more equal society – whether separate from, or as a part of, the United Kingdom. Although much of the theatre work described here took place in the final six weeks before the referendum itself, and was limited to relatively small audience numbers, these pieces were a constituent part of a wider social movement, which included performances of opinion across the country and beyond. In its many forms and guises, performance has thus offered a space and time for both politicised spectacle and dialogue around political issues. Even the supposedly defunct tradition of ‘town hall meetings’ reappeared, with such gatherings being heavily attended up and down the country. What remains to be seen is whether this seismic political event will continue to galvanise future political participation. How will the campaign and its performances be documented and remembered? Will future performative endeavours offer a lens through which to further reflect on the events of 18 September, helping us to understand the implications of the referendum outcome? As a number of significant elections take place in 2015 and 2016, the politics of performance that the referendum campaign brought into play has great potential to contribute significantly to a changing political landscape.

Notes

1. The Electoral Management Board for Scotland, ‘Scottish Independence Referendum’ <www.scotlandreferendum.info> [accessed 29 September 2014].

2. National Collective <www.nationalcollective.com> [accessed 29 September 2014].

3. Wallace, dir. by Rob Drummond and David Overend, The Arches and National Theatre of Great Britain, The Arches, Glasgow, first performed 14 September 2014 (work-in-progress performance).

4. Early Days: The Arches’ Referendum Festival, The Arches, Glasgow. 4–19 September 2014 <www.thearches.co.uk/events/arts/early-days-the-arches-referendum-festival> [accessed 29 September 2014].

5. David Cameron, Prime Minister of the UK, Speech, 19 September 2014.

6. Nicola Sturgeon, Deputy First Minister of the Scottish Government, Speech, 19 September 2014.

7. Jen Harvie, Staging the UK (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005), p. 2.

8. STV, Salmond and Darling: The Debate, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Glasgow, 5 August 2014 <player.stv.tv/programmes/salmond-darling> [accessed 28 October 2014].

9. Gerry Hassan, ‘Democracy Needs More than Televised Slanging Matches’, The Daily Record, 26 August 2014 <www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/politics/democracy-needs-more-televised-slanging-4111862> [accessed 28 October 2014].

10. Stephen Coleman, ‘Meaningful Political Debate in the Age of the Soundbite’, in Televised Election Debates: International Perspectives, ed. by Stephen Coleman (London: Macmillan Press, 1999), pp. 1–24 (p. 3).

11. Stephen Coleman, ‘Preface’, in Televised Election Debates: International Perspectives, ed. by Stephen Coleman (London: Macmillan Press, 1999), pp. vii–viii (p. vii).

12. Radical Independence Campaign <www.radicalindependence.org> [accessed 29 September 2014].

13. Women for Independence <www.womenforindependence.org> [accessed 29 September 2014].

14. Common Weal <www.allofusfirst.org> [accessed 29 September 2014].

15. The term refers to the heavily populated ‘corridor’ linking Glasgow in the west to Edinburgh in the east.

16. Richard Schechner, Performance Studies (Oxon: Routledge, 2006), p. 32.

17. Cited in Harvie, Staging the UK, p. 9.

18. ‘Young Scotland: A Debate on Independence’, Young Scot and The Sunday Herald event, The Arches, Glasgow, 8 February 2014.

19. ‘Festival of the Common Weal’, The Arches, Glasgow, 6 July 2014.

20. Robin McAlpine, Common Weal, Glasgow, Scottish Left Review Press for the Jimmy Reid Foundation, 2014.

21. ‘Independence Blethers’, Milngavie Town Centre, Glasgow, 26 July 2014.

22. Cat Boyd and Jenny Morrison’s Scottish Independence: A Feminist Response (Edinburgh: Word Power Books, 2014) explores some of the reasons why women were mobilised in the lead-up to the referendum.

23. Yestival, National Collective, various events around Scotland, 20 June–3 August 2014 <www.nationalcollective.com/yestival> [accessed 1 October 2014].

24. The official Twitter account of the Yes campaign had 103,000 followers, compared to 42,000 for Better Together. Alex Salmond had 95,000 Twitter followers and Nicola Sturgeon 66,000 – while Alistair Darling had just 21,000. On Facebook, the Yes campaign page attracted more than 320,000 likes compared to 218,000 for the No campaign. Sophy Ridge, ‘Yes Wins Referendum’s Social Media Battle’, 19 September 2014, Sky News <news.sky.com/story/1337925/yes-wins-referendums-social-media-battle> [accessed 30 October 2014].

25. Paul Mason, ‘Scotland and Catalonia are Straws in the Wind for the Whole of Europe’, Guardian <www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/oct/05/catalonia-independence-more-than-nationalism> [accessed 20 October 2014].

26. All Back to Bowie’s, by David Greig, et al. The Stand Comedy Club, Edinburgh, 5-24 August 2014 <www.allbacktobowies.com> [accessed 1 October 2014].

27. National Collective Presents… by National Collective, Scottish Storytelling Centre, Edinburgh, 9–23 August 2014 <http://www.nationalcollective.com/2014/07/28/national-collective-presents/#sthash.BuSxrX5w.dpuf> [accessed 1 October 2014].

28. MacBraveheart: The Other Scottish Play, written and dir. by Phil Differ, Assembly Rooms, Edinburgh, 7–24 August 2014.

29. Now’s The Hour, by Scottish Youth Theatre, The Stand, Edinburgh, 7–24 August 2014 <www.scottishyouththeatre.org/involved/nows_the_hour_project> [URL no longer active].

30. The British Referendum, by Erich McElroy, The Community Project, Edinburgh, 7–24 August.

31. How to Choose?, by Davey Anderson and Gary McNair, The Arches, Glasgow, 17 September 2014. Podcast of the project available at <https://soundcloud.com/trigger-stuff/sets/how-to-choose> [accessed 8 November 2014].

32. Christine Hamilton, ‘Yes or No, That is the Answer’, Arts Professional, 7 July 2014. <www.artsprofessional.co.uk/magazine/276/article/yes-or-no-answer> [accessed 29 September 2014].

33. Great Yes, No, Don’t Know Five Minute Theatre Show, curated by David Greig and David MacLennan, National Theatre of Scotland, 23 June 2014 <http://fiveminutetheatre.com> [accessed 2 October 2014].

34. I’m With the Band, by Tim Price, Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh, 7–24 August 2013.

35. The Pitiless Storm, by Chris Dolan, Scottish tour, July–August 2014.

36. The Pure, the Dead and the Brilliant, by Alan Bissett, Assembly Rooms, Edinburgh. 7–24 August; transferred to Tron Theatre Glasgow, 18 September 2014.

37. Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics [1998], trans. by Simon Pleasance and Fronza Woods (Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2002).

38. Ibid., p. 16.

39. Ibid., pp. 31, 58.

40. Claire Bishop, ‘Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics’, October, 110 (Fall, 2004), 51–79, (p. 67).

41. Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, p. 43.

42. Harvie, Staging the UK, p. 5.

43. Early Days, The Arches.

44. Bishop, ‘Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics’, p. 65. Emphasis in original.

45. Félix Guattari, Molecular Revolution: Psychiatry and Politics (New York: Puffin, 1984), p. 24.

46. Ibid.

47. Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies (London: Athlone, 2008), p. 25.

48. Brian Fergusson, ‘Scottish Independence Productions Not at EIF 2014’, Scotsman, 11 August 2013 <www.scotsman.com/lifestyle/arts/news/scottish-independence-productions-not-at-eif-2014-1-3040283> [accessed 30 September 2014].

49. Mike Small, ‘The Edinburgh Festival’s Attempt to Keep Politics Out in 2014 is Farcical’, Guardian, 13 August 2013 <www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/aug/13/edinburgh-festival-scottish-independence-referendum> [accessed 29 September 2014].

50. The James Plays, by Rona Munro, dir. by Laurie Sansom, National Theatre of Scotland and National Theatre of Great Britain, Festival Theatre, Edinburgh, 5–22 August 2014.

51. Trish Reid, ‘Introduction’, in Contemporary Scottish Plays, ed. by Trish Reid (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), ix–xvii, (p. xii).

52. Susannah Clapp, ‘The James Plays Review – Rona Munro’s Timely Game of Thrones’, Guardian, 17 August 2014 <www.theguardian.com/stage/2014/aug/17/james-plays-edinburgh-sofie-grabol-observer-review> [accessed 30 September 2014].

53. David Greig, ‘Why the Debate on Scottish Independence Might Be More Interesting Than You Think?’, Bella Caledonia, August 2014 <http://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2013/08/04/why-the-debate-on-scottish-independence-might-be-more-interesting-than-you-think> [accessed 29 September 2014].

54. Tom Clark, ‘Poll: 71% Find Alex Salmond Victorious in Second Scottish Independence Debate’, Guardian, 25 August 2014 <www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/aug/25/guardian-icm-poll-alex-salmond-winner-scotland-debate> [accessed 8 November 2014].

55. Stephen Coleman, How Voters Feel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 33.

56. Ibid., pp. 33–34.

57. Claire Bishop, Artificial Hells (London: Verso, 2012), emphasis in original.

58. Ibid., p. 27. Emphasis in original.