ABSTRACT

The Sentence Repetition Task (SRT) is an assessment tool for children’s language abilities, which has been used in various languages and speaker types. The present study adapted the LITMUS-SRT to European Portuguese (EP) and applied it to 43 monolingual and 25 bilingual heritage speakers of EP with German as societal language (aged 6 to 10 years), in order to evaluate their knowledge of various syntactic properties, which differ in their level of complexity. Additionally, it also assessed the effect of language experience variables—that is, richness of the heritage language (HL) input and cumulative amount of HL exposure—on the performance of the bilingual children in the task. Results demonstrate that group (monolingual vs. bilingual), the children’s age and the level of complexity (with three levels) predict children’s accuracy scores. Furthermore, it is particularly in the highest levels of complexity that the bilingual children show more variation and more protracted development, with clitics and subjunctives being the most challenging linguistic properties. As for the role of the input-related variables, richness of the HL input, but not cumulative amount of exposure, emerged as a significant predictor of the bilingual children’s accuracy.

1. Introduction

It is by now a well-established fact that bilingual and monolingual children go through comparable trajectories of language development and may reach identical levels of proficiency in a target language; however, bilingual children show much more intra-group variation regarding the pace and the outcome of the acquisition process, compared to age-matched monolingual peers (De Houwer Citation2009). This is due to the variety of extra-linguistic factors that modulate bilingual language development, in particular age of onset of bilingualism, quantity and quality of language input, as well as type and degree of instruction in each language (Hoff et al. Citation2014, Rodina et al. Citation2020, Unsworth Citation2013; see also Paradis Citation2023, for a recent overview). In addition, language-external variables are in interplay with linguistic factors such as the (dis)similarity between the two (or more) language systems and internal characteristics of each language (Torregrossa et al. Citation2023). Understanding how language-external and language-internal factors interact in (bilingual) language development is a crucial endeavor for researchers, which adds to our knowledge of the human language faculty.

One important step in this endeavor consists of finding the appropriate instruments to assess children’s language abilities, in particular by developing assessment tools that are suitable to test mono- and bilingual children alike (Chiat et al. Citation2013). This becomes even more challenging when we assess bilinguals’ weaker languages, which generally are not the school language and may be characterized by low (or non-existent) literacy skills. This is normally the case of heritage languages (HLs), that is, the family language of bilingual children with an immigration background, who grow up with another dominant environment language. Against this backdrop, the present paper presents an assessment tool for European Portuguese (EP) and the results of its application to a group of monolingual EP children and another group of EP-German bilingual children, who acquired Portuguese as their HL in Germany. We developed a Sentence Repetition Task (SRT) to assess children’s knowledge of various syntactic properties, which differ in their level of complexity. We will show that the SRT is suitable to capture the language-internal differences between the tested properties in monolingual language development and, in a more pronounced way, in heritage Portuguese. Given that most work on the syntactic development of (European) Portuguese has focused on monolingual children, this study contributes to this field of research by analyzing the performance of bilingual children as well.

2. Background

2.1. Role of language exposure in heritage language acquisition

Research on heritage bilingualism has shown that child HSs’ language acquisition environment is more heterogeneous than that of their monolingually-raised peers (Montrul Citation2016, Paradis Citation2023). This is because bilingual children’s language exposure is divided between the two languages and there is huge individual variation regarding the amount and type of language input they receive from each one (Unsworth Citation2015).

The variability regarding the language environment in which children acquire the HL has been robustly shown to have an impact on its development across linguistic domains (Flores et al. Citation2017, Haman et al. Citation2017, Hoff et al. Citation2012, Rodina et al. Citation2020, Torregrossa et al. Citation2023). In fact, several studies in the last decades have revealed that the pace and outcome of HL acquisition are interconnected with language experience variables such as the amount of current and/or over time HL exposure (Komeili et al. Citation2020, Mitrofanova et al. Citation2018, Rodina & Westergaard Citation2017) as well as the richness of the HL input (Ibrahim et al. Citation2020, Jia & Paradis Citation2015). For example, Mitrofanova et al. (Citation2018) investigated Norwegian-Russian bilingual children’s acquisition of grammatical gender in HL-Russian, having found that cumulative length of exposure to the HL was the language experience variable that predicted children’s performance in grammatical gender tasks the best. Komeili et al. (Citation2020), in turn, found that Farsi-English bilingual children’s performance in a SRT in HL-Farsi was significantly and positively correlated with their total use of this language. Ibrahim et al. (Citation2020) also investigated the role of language experience variables in the performance of child HSs of Arabic with German as societal language on a SRT in the HL. They found that length of Arabic-schooling, current Arabic use, and Arabic-linguistic richness were significant predictors of the children’s accuracy scores in the task.

Thus, taking the effect of language experience variables into consideration when analysing HL development is an indispensable requirement.

2.2. Assessing syntactic development with Sentence Repetition Tasks

Assessing the syntactic development of heritage bilingual children is a challenging task, especially when their HL is the one being assessed, given that they may lack lexical knowledge to complete the task successfully. The SRT is a method that has been successfully used to assess syntactic development in bilingual children, in their majority language (see Almeida et al. Citation2017, for French in Arabic-French, EP-French and Turkish-French children; Fleckstein et al. Citation2018, for French in Arabic-French and English-French children; Prentza et al. Citation2022, for Greek in Albanian-Greek children), as well as in their HL (see Haman et al. Citation2017, for Polish in Polish-English children; Komeili et al. Citation2020, for Farsi in Farsi-English children) or, comparatively, in both their languages (see Andreou et al. Citation2021, for the use of SRTs in Italian and Greek; Hamann et al. Citation2020, for German and Arabic; Meir, Walters & Armon-Lotem Citation2016, for Russian and Hebrew). SRT is an elicited imitation task that does not require as much lexical knowledge as other production tasks and may thus be more appropriate for bilingual children, especially those that are not dominant in the language that is being assessed. Furthermore, the literature convincingly shows that the SRT is a valid method for assessing syntactic knowledge, provided sentence length and other details, such as frequency of lexical items, are controlled for (Blume & Lust Citation2017, Marinis & Armon-Lotem Citation2015). Children are not mere parrots that repeat sentences: to repeat a sentence correctly, besides holding the information in memory,Footnote1 the child must process it and comprehend its grammar (Lust et al. Citation1996). Specific mistakes that children make when they fail to repeat correctly give us information on their implicit grammatical knowledge. It is expected that children will only be able to repeat the sentence correctly when its syntactic structure is part of their internal grammar.

Elicited imitation tasks may be developed to investigate specific linguistic variables in experimental tasks contrasting sentences that differ minimally in specific syntactic aspects (Blume & Lust Citation2017, Lust et al. Citation1996). However, elicited imitation tasks have also been used to assess syntactic knowledge of monolingual and bilingual children in clinical settings (Almeida et al. Citation2017, Marinis & Armon-Lotem Citation2015), as well as to determine the grammatical knowledge, the language proficiency level and the language dominance of bilingual children or adult second language learners (Andreou et al. Citation2021, Erlam Citation2006, Gaillard & Tremblay Citation2016, Schönström & Hauser Citation2022, Spada et al. Citation2015).

For Portuguese, although some language batteries include the elicited imitation of sentences (e.g., SINTACS: Vieira Citation2011; ALPE: Mendes et al. Citation2014), there is no SRT based on theoretically informed linguistic criteria which systematically includes linguistic structures of different levels of difficulty designed for school-aged children. Furthermore, to our knowledge, no SRT tool has yet been used to assess bilingual children with EP as HL. Within the COST Action IS0804 ‘Language Impairment in a Multilingual Society: Linguistic Patterns and the Road to Assessment,’ versions of the LITMUS-SRT have been developed for more than twenty languages (Marinis & Armon-Lotem Citation2015).

In this paper, we describe the development and first results of a SRT for EP, adapted from the LITMUS-SRT to assess the grammatical knowledge of monolingual and bilingual children. Its reliability for clinical contexts has not been investigated yet.

In the next section, we describe the different syntactic structures that were included in the EP version of the SRT, considering previous findings on their acquisition, in order to justify their inclusion in our EP version of the task, according to different levels of difficulty.

2.3. Syntactic development in EP

The development of our Sentence Repetition Task-European Portuguese (SRT-EP) followed the rationale for the LITMUS-SRT. It was based on a first version of the task developed within the COST Action IS0804 that was later modified and improved according to criteria that will be explained in Section 3.

The task includes different types of syntactic structures with different levels of difficulty, some of which have been shown to be problematic for children with language impairment or to develop late both in monolingual and bilingual acquisition. Following the rationale of the LITMUS-SRT (Marinis & Armon-Lotem Citation2015), the SRT-EP includes easier and more complex structures distributed across three levels of complexity. The complexity of the task is progressive, starting with simpler structures and ending in more complex ones. It includes monoclausal sentences and biclausal sentences with coordination and subordination processes, structures that have proven to be difficult for children in many languages, as well as structures that are challenging in EP.

In this section, we consider previous findings on the monolingual or bilingual acquisition of these structures, that include: simple clauses (with the indicative or the subjunctive); accusative clitics in different syntactic contexts; actional and non-actional passives; finite and infinitival complement clauses; coordinate clauses; relative clauses; wh-questions; and conditional structures.

As for monoclausal sentences, the task includes structures with different degrees of complexity: SVO sentences with the indicative, SVO sentences with the subjunctive (triggered by the modal adverb talvez ‘maybe’), passives, monoclausal sentences with accusative clitics, and monoclausal sentences with wh-movement. In the monoclausal sentences, we expect children to perform better in sentences with the indicative (preterite and periphrastic future) than in sentences with the subjunctive, thus the former are included in complexity level 1 (C1) and the latter in complexity level 2 (C2). This division is based on previous studies, which have reported protracted development of the subjunctive in monolingual and bilingual language acquisition, compared to indicative forms in various syntactic contexts (Flores et al. Citation2017, Citation2019; Gonçalves et al. Citation2011; Jesus et al. Citation2019). The use of the subjunctive with talvez has not been studied yet.

As for the monoclausal sentences with an accusative clitic, these have been shown to be particularly challenging in EP, thus being included in complexity level 3 (C3). EP grammar has accusative clitics that may occur in preverbal position (proclisis) or postverbal position (enclisis) depending on several factors, in particular the presence or absence of a proclisis triggerFootnote2 (see, for a comprehensive description, Martins Citation2013) (see [1]):

Furthermore, when the referent for the object is linguistically or pragmatically salient, accusative clitics may alternate with a null object in some syntactic contexts, including simple sentences [see (2)]. This object omission construction, however, is not tolerated by most EP native speakers in island contexts [see (3)] (Raposo Citation1986):

These two properties—variable clitic placement and alternation with null objects—make EP clitics particularly difficult to acquire. Although clitics are produced early, their target production in obligatory contexts stabilizes late, as shown in many studies (Costa & Lobo Citation2007, Costa et al. Citation2015, Flores et al. Citation2020, Lira et al. Citationin press, Varlokosta et al. Citation2016). Late mastery of accusative clitics has also been observed for bilinguals and heritage speakers of EP (Costa et al. Citation2016; Flores & Barbosa Citation2014; Flores et al. Citation2016; Nardelli & Lobo Citation2018; Rinke & Flores Citation2014; Tomaz et al. Citation2019, Citation2020). In EP, children tend to omit accusative clitics at much higher rates than in other languages and until later, and they have trouble dealing with the variable placement pattern of EP: they tend to generalize enclisis to proclitic contexts.

Passive structures have also shown to be difficult for children in many languages (although not all), and they seem to be particularly affected in children with developmental language disorders. So-called “long passives” (the ones with a by-phrase) (4b) and non-actional passives (5) seem to be especially demanding for children:

These difficulties have been attributed to different factors: non-canonical word order (Bever Citation1970); semantic properties (Maratsos et al. Citation1985); development of the mechanism of theta role transmission (Fox & Grodzinsky Citation1998); the maturation of different grammatical constraints (Borer & Wexler Citation1987, Hirsch & Wexler Citation2006, Snyder & Hyams Citation2015, Wexler Citation2004).

For Portuguese, different studies have reported late mastery of reversible passives (Sim-Sim Citation2006), low production of passives in spontaneous production (Estrela Citation2013), asymmetries between actional and non-actional passives – the latter being more difficult (Agostinho Citation2020, Estrela Citation2013), and better comprehension of eventive passives than resultative and stative passives (Agostinho Citation2020, Corrêa et al. Citation2017, Estrela Citation2013, Lima Júnior et al. Citation2018). Whatever the source that explains their late mastery, passives, and in particular long non-actional passives, are structures that stabilize late and that can be indicators of language development. Based on these previous findings, short passives have been included in C2 and long passives in C3.

The task also includes monoclausal sentences with wh-movement. Wh-questions in EP usually show movement of the wh-constituent to the left periphery (although wh-in situ is also possible). When the moved wh-constituent is the subject, the canonical word order is maintained, whereas when the moved wh-constituent is the object, the canonical word order is disrupted, and the subject intervenes in the chain formed by the moved element and its base position:

There is now ample crosslinguistic evidence that object wh-questions are harder for children than subject wh-questions, especially when the wh-constituent has a lexical restriction, as in (7b) (Bentea Citation2017, Friedmann & Novogrodsky Citation2011, among others). EP is no exception: both Cerejeira (Citation2009) and Baião & Lobo (Citation2014) show that EP children produce less target object wh-questions than subject wh-questions; and both studies also show that children have more trouble comprehending which object wh-questions than who object wh-questions.

According to Bentea et al. (Citation2016), following on Friedmann et al. (Citation2009) and Grillo (Citation2009), this stems from a constraint—featural relativized minimality—which causes processing costs for children when there is an inclusion relation between the features of the moved element and the intervener. These asymmetries in the production and comprehension of object wh-questions (and, in particular, the ones with a lexical restriction) are quite widespread crosslinguistically, and therefore it is expected that object which-questions will cause difficulties for younger/immature children and for monolingual and bilingual children with DLD independently of their dominant language.

Alternative approaches considering adult processing of other structures with wh-movement, and relative clauses in particular, have proposed that different factors may play a role, including memory, interpretative processes and frequency (see Gordon & Lowder Citation2012, for a revision). Specifically, models that consider similarity-based interference during memory retrieval (Gordon et al. Citation2001, Citation2004; Lewis et al. Citation2006; among others), similarly to featural relativized minimality accounts, predict that the processing costs will be higher when the moved element and the intervening element are more similar in their semantic characteristics. In fact, Villata et al. (Citation2016), despite following a featural relativized minimality approach, leave open the possibility of integrating featural relativized minimality accounts and memory-based models. Both approaches predict that subject dependencies will be processed more easily than object dependencies and, crucially, that the processing costs will be modulated by the degree of similarity between the moved element and the intervening element.

Based on these previous studies, we included who object wh-questions in C2 and which object wh-questions in C3.

In addition to monoclausal sentences with different degrees of complexity, the task includes biclausal sentences. The production of sentences with two or more clauses, combined through coordination or subordination processes, is usually taken as an indicator of language development (Peristeri et al. Citation2017).

Biclausal sentences may display different degrees of complexity depending on the type of dependency between the clauses, the depth of embedding of the clause, the presence of wh-movement, and semantic properties of the clause. Common coordinators emerge earlier than subordinators (Costa et al. Citation2008, Costa Citation2010), and different types of subordinate clauses may display different degrees of complexity. For instance, relative clauses are embedded sentences that show a higher syntactic complexity than other embedded sentences because they imply wh-movement. These subordinate clauses, and in particular the ones with object dependencies, as argued above for wh-object questions, are difficult for children with language disorders and may be difficult as well for L2 learners and for heritage speakers (Delage & Tuller Citation2010, Novogrodsky & Friedmann Citation2006, Scheidnes et al. Citation2009).

Previous research shows that coordinators emerge earlier than subordinators. Costa et al. (Citation2008) establish the following emergency scale of connectives in EP children’s spontaneous productions: e ‘and’ > mas ‘but’ > porque ‘because’ > se ‘if’. Coordination processes with connectorsFootnote3 are generally assumed to be easier than subordination processes, and coordinate clauses are much more frequent than subordinate clauses in children’s early written productions (Batalha et al. Citation2022). Therefore, we included coordinate clauses introduced by e ‘and’ and mas ‘but’ in level C2.

For relative clauses, there is also robust crosslinguistic evidence that object relatives (8b) are harder than subject relatives (8a) (Adani et al. Citation2010, Durrleman & Bentea Citation2021, Friedmann et al. Citation2009, among others).

Similar results have been obtained for monolingual acquisition of EP. As in other languages, object relative clauses in EP are harder to produce and to comprehend than subject relative clauses, and this capacity develops over time (Costa et al. Citation2011, Lobo & Soares-Jesel Citation2017, Vasconcelos Citation1993). The source of the asymmetry between the acquisition of subject relatives and object relatives, in addition to non-canonical word order (Bever Citation1970), has been given different explanations. Some approaches have attributed it to featural relativized minimality, and to the processing cost of structures in which the moved constituent and an intervening constituent share similar features (Friedmann et al. Citation2009). Alternatively, following studies on adult processing, we can find memory-based models that explain these asymmetries with similarity-based interference or models that consider an interplay between several factors (see Gordon & Lowder Citation2012, for a review). These different approaches are not mutually exclusive and may in fact be complementary. Whatever is the right explanation, it is a well-grounded fact that object relatives are generally harder than subject relatives. Based on these findings, we included subject relative clauses in C2 and object relative clauses in C3.

As for complement clauses, the task includes both finite and infinitival complement clauses. Finite complement clauses emerge early, according to Santos (Citation2017) and Soares (Citation2006). However, not all properties of finite complement clauses are mastered early. Mood selection (indicative or subjunctive) in the finite embedded clause is subject to development, and children still have problems with some contexts at age 8-9 (Jesus et al. Citation2019). Protracted development of the subjunctive in embedded complement clauses has also been found in bilingual heritage speakers of EP (Flores et al. Citation2017, Citation2019). As for infinitival complement clauses, previous research has found that subject control infinitival clauses selected by volitional predicates are acquired early, whereas other infinitival complement clauses develop later (Agostinho Citation2014, Santos et al. Citation2016, Santos Citation2017) and may remain unstable in adult heritage grammars (Barbosa et al. Citation2018). For this reason, subject control infinitival clauses selected by volitional predicates were included in C1 and finite complement clauses in C2.

Conditional clauses introduced by se ‘if’ emerge later than other types of embedded clauses (Batalha et al. Citation2022, Costa et al. Citation2008). Although these embedded sentences do not display movement, they involve a high degree of complexity for syntactic, semantic, and morphological reasons. Some of these adjunct (non-selected) embedded sentences display the subjunctive mood. Additionally, conditional structures can be associated to different semantic values: hypothetical or unreal conditionals (with the subjunctive mood) are harder than real conditionals (with the indicative mood).

Although there is not much investigation on the acquisition of conditional clauses in Portuguese, the literature reports that different properties of concessive and conditional clauses develop late (Costa Citation2010, Gonçalves et al. Citation2011), thus these sentences with conditional predicates were assigned to C3.

Torregrossa et al. (Citation2023) have shown that assessment tools such as cloze tests, which include structures with different degrees of difficulty are useful instruments to capture developmental differences between heritage speakers of EP with different ages, varying degrees of language exposure and in contact with different majority languages. Since cloze tests are written tests, which require the heritage speakers to be literate to some extent in their HL, alternative oral tasks, as the one we propose here, are necessary for children that are not formally instructed in their HL. In this sense, we propose that SRTs that include structures with different degrees of complexity, defined on the basis of previous studies, as described in this section, may complement the existing array of language assessment tools for EP, being adequate to assess monolingual and bilingual children’s development (Gaillard & Tremblay Citation2016).

3. The study

3.1. Research questions

The overall aim of this study is to assess the effectiveness of a SRT, developed for EP following the LITMUS procedures, in testing the language abilities of monolingual children and child heritage speakers of EP who grow up in a German-dominant environment. To achieve this overall aim, we ask the following five research questions:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): Do the children’s accuracy scores reflect the different levels of difficulty, defined on the basis of previous research on the acquisition of EP? That is, do children indeed score differently on the structures belonging to the three levels of difficulty, as shown for SRTs developed for other languages (Ibrahim & Hamann Citation2017, Komeili et al. Citation2020, Marinis & Armon-Lotem Citation2015, among others)?

Research Question 2 (RQ2): Do monolingual and bilingual children perform alike in the SRT or do child heritage speakers of EP perform lower than age-matched monolingual peers? If we observe differences, are these modulated by the different degrees of complexity of the tested structures? If so, which structures stand out as being particularly difficult for heritage bilingual children?

Research Question 3 (RQ3): Does the children’s age at testing predict children’s accuracy scores? If so, is the age effect visible in each complexity level and for both groups?

Research Question 4 (RQ4): Regarding the bilingual children, how do language experience variables, such as cumulative amount of HL exposure and richness of the HL input, influence performance of the child HSs in the task, when controlled for age and complexity level of the syntactic structures?

Research Question 5 (RQ5): Which scoring method, target structure (TS) or target structure & grammaticality (TS&Gra), is more fine-grained in capturing performance differences in the monolingual and bilingual groups?

3.2. Participants

Participants were 68 typically developing child speakers of EP between the ages of six and ten years. The children were divided into two groups: EP monolinguals and EP-German bilinguals. The monolingual group comprised 43 children (25 female) with a mean age of 8.05 years (SD = 1.38). All these children were born in Portugal and were being raised in a monolingual environment, as reported by their caregivers. As for the bilingual group, whose sociolinguistic data were collected by means of a detailed parental questionnaire (Correia & Flores Citation2021), it included 25 child heritage speakers of EP (12 female) with a mean age of 8.60 (SD = 1.29) who were living in Germany at the time of testing. Twenty children were born in Germany and the remaining five were born in Portugal, having immigrated to the host country before the age of 36 months. All the children had been exposed to EP from birth and half of them (13/25) had also been exposed to German since they were born. The remaining children started receiving systematic input in the majority language between the ages of 10 and 36 months. Furthermore, 21 out of the 25 children were being raised in families in which both parents spoke EP as a first language (L1); the remaining children belonged to households where just one of the parents had EP as an L1. With respect to the bilingual children’s cumulative amount of HL exposure within the homeFootnote4 (C.EXP.HL) and richness of the HL inputFootnote5 (HL.RICHNESS), they ranged from 40.7 to 125 (M = 88.2; SD = 22.5) and from 0.05 to 0.63 (M = 0.33; SD = 0.18), respectively. Children’s socioeconomic status (SES) was assessed based on the mothers’ education level, which ranged from 1 (i.e., basic education/first cycle) to 5 (i.e., higher education) in both groups of speakers (monolinguals: Mdn = 4; IQR = 1; bilinguals: Mdn = 4, IQR = 2). No significant between-group differences were found regarding SES (U = 483.5, p = .466).

Participation in the study was voluntary and, prior to the study, a written parental informed consent was obtained for all participants. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in Social and Human Science of the University of Minho (CEICSH 004/2019 ADENDA1).

3.3. Materials: the SRT-EP

The current SRT-EP was built on the first version of the task which was developed within the COST ACTION IS0804 and included 56 sentences targeting grammatical structures such as: simple sentences with periphrastic future and simple past, long passives, accusative clitics in enclisis and proclisis contexts, object wh-question with who and which, coordinate clauses, finite and non-finite complement clauses, and relative clauses (see Table A in the Online Supplementary Materials).

All these structures were maintained in the new version of the task, but some modifications were made in order to accommodate additional grammatical structures (i.e., SVO sentences with the subjunctive, short passives, and conditional clauses)Footnote6 and to solve some issues that were found to be problematic when the first version was piloted (e.g., the use of proper nouns in several stimuli). The main alterations involved: (i) reducing/expanding the number of sentences per target structure, so that each one would have the same number of stimuli (i.e., four sentences); (ii) substituting proper nouns for common nouns (e.g., Maria for menina ‘girl’); (iii) avoiding contexts in which morphophonological properties would hinder the perception of the clitic. For the current version of the task, the stimuli were also pre-recorded by two adult monolingual speakers of EP (male and female) and incorporated in a PowerPoint presentation.

Moreover, to ensure that the lexical items included in the task would not be too difficult for the youngest children, we asked 11 primary school teachers to estimate on a 5-point scale, for every content word of the task (n = 144), the relative amount of 6-year-old typically developing children who knew its meaning. The scale was: none (0%) = 1, a few (+/- 25% = 2, half of them (+/- 50%) = 3, many (+/- 75%) = 4, all of them (100%) = 5. The reasoning behind this methodological approach was that, due to their daily contact with children within the same age range of this study’s participants, primary school teachers would provide more reliable information on the children’s actual knowledge of the task’s lexical items than some of the available EP lexical datasets such as ESCOLEX (Soares et al. Citation2014) or Portulex (Teixeira & Castro Citation2007). The latter databases are based on school textbooks, which may not cover the lexical knowledge of EP children who are starting to be literate. The outcome of the rating task revealed that the content words included in the SRT are suitable for children as young as six years old, since the medians of the ratings provided by primary school teachers ranged from 4 to 5 (see Table B in the Online Supplementary Materials for measures of central tendency and dispersion of each lexical item).

The resulting set of task stimuli comprised two practice items and 60 test items (four items per structure), with sentences varying from 10 to 18 syllables in length (see ). The setting-up of the task was done in two steps. In the first step and in line with the literature on the syntactic development in EP (see Section 2.3), each target syntactic structure was assigned one of three increasing complexity levels, which ranged from C1 (less complex) to C3 (more complex).

Table 1. Contents of the SRT-EP.

In the second step and taking into account their assigned complexity level, the structures were grouped into three blocks and pseudo-randomized so that the children would not be consecutively presented with two items of the same target structure or the same lexical items. Care was also taken to present children with stimuli produced by a female and a male voice in an alternating way. Furthermore, bearing in mind the huge individual differences that typically characterize the language proficiency of bilingual speakers in their heritage language and in order to prevent feelings of frustration when performing the task, the first block included structures from level C1 and C2, and the second and third blocks included structures from level C2 and C3, as shown in .

Table 2. Distribution of items by blocks in the SRT-EP.

3.4. Procedure and scoring

Participants were tested individually in a quiet room at their homes or, as was the case for some bilingual children, at the schools where they were attending Portuguese classes. The SRT was administered to each child by means of a PowerPoint presentation with embedded audio files. During the task administration, participants sat in front of a laptop computer and listened to the stimuli through headphones. They were instructed to listen to the sentences attentively and to repeat exactly what they heard. In order to familiarise children with the task, children were presented, prior to the experimental stimuli, with a practice session with two training sentences. In the actual experimental task, children were allowed to listen to each stimulus only once unless some noise or interruption prevented them from hearing it. Children were orally praised from time to time irrespective of how successful their repetitions were. Self-corrections were allowed but only the final response was scored, whether it was correct or incorrect. Children’s responses were audio recorded and later orthographically transcribed. The scoring was made offline based on the recorded audio files.Footnote7

The scoring procedure adopted for the present study included two measures: target structure (TS) and target structure & grammaticality (TS&Gra). The first measure is similar to the fifth scoring scheme (i.e., sentence structure score) presented by Marinis & Armon-Lotem (Citation2015). According to this scoring method, a score of 1 is given if the child produces the structure that is targeted independently of whether (s)he makes changes in other parts of the sentence [see (10a)] with a number mismatch in the NP, which is not the targeted structure). A score of 0 is awarded if the child either makes an error in the targeted structure, e.g., omission of the accusative clitic in sentences targeting accusative clitics (see [10b]), or does not produce it and substitutes it with another structureFootnote8, e.g., using the indicative mood instead of the subjunctive one [see (10c)].

As for the second measure, target structure & grammaticality, it is a combination of the previous one with the measure grammaticality proposed by Marinis & Armon-Lotem (Citation2015). According to this composite scoring scheme, a score of 1 is given only if the targeted structure is produced and the sentence has no grammatical errors despite the changes the child makes in it [see (11)]; otherwise, a score of 0 is awarded. Thus, with this scoring method, we aim not only at assessing whether the different syntactic structures are part of the children’s internal grammar, but also at evaluating children’s global grammatical/language proficiency.Footnote9

3.5. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 4.1.3, Core Team Citation2022), and data visualization was performed using the packages ggplot2 (version 3.3.5; Wickham Citation2016) and sjPlot (version 2.8.10; Lüdecke Citation2021). The internal consistency of the SRT-EP was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients, which were computed by means of the alpha() function of the psych package (version 2.2.5; Revelle Citation2022). To address the research questions, we fitted two sets of generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLMMs) to the data (see , for an overview) using the lme4 package (version 1.1.29; Bates et al. Citation2015). Set A addressed the research questions focused on the two groups of EP-speaking children (RQ1–RQ3) whereas Set B addressed the research questions focused on the role that language experience variables play in the performance of the bilingual group (RQ4). RQ5 derives from the results of both sets of models.

Table 3. GLMMs in Sets A and B: overview of the dependent variables (DVs) and predictors.

Regarding Set A, it is composed of two subsets of analyses. Subset A1 comprised two models—for one of the models, the dependent variable was accuracy under the measure TS and, for the other one, it was accuracy under the measure TS&Gra. Predictors were age (in months), level of complexity (C1/C2/C3), group (monolingual/bilingual), and their interactions. Subset A2 included two models—one for TS and another one for TS&Gra - per participants’ performance in each level of complexity. Predictors were age (in months) and group (monolingual/bilingual) as well as their interaction. With respect to Set B, it comprised two models. The dependent variables were TS, for one of the models, and TS&Gra, for the other one. Predictors were cumulative amount of HL exposure within the home (C.EXP.HL) and richness of the HL input (HL.RICHNESS) as well as age (in months) and level of complexity (C1/C2/C3). In each set of GLMMs, the dependent variables TS and TS&Gra were binomial categorical (two levels: 0 = inaccurate; 1 = accurate). Running a similar model for each measure enabled us to investigate whether differences in scoring method affect children’s results in the SRT. Moreover, including the variables age and level of complexity in the models of Set B allowed us to assess the role of C.EXP.HL and HL.RICHNESS while taking into account the children’s age and sentences’ level of complexity. Before running the GLMMs, the continuous variables age, C.EXP.HL and HL.RICHNESS were scaled using the scale() function from the base package with center and scale set to TRUE. As for the categorical variables, they were coded as follows: the two-level factor group was coded using sum contrast coding (−.50/.50) and the three-level factor level of complexity was coded using simple contrast codingFootnote10 (UCLA Statistical Consulting Citation2011). We specified random intercepts for participants and items (i.e., sentences). Predicted probabilities derived from the models were obtained using the ggpredict() function from the ggeffects package (version 1.1.2; Lüdecke Citation2018).

4. Results

We will start by presenting the results of the reliability analyses aimed at assessing the internal consistency of the task. Then we will show the descriptive statistics regarding not only children’s accuracy rates on the whole task, but also their accuracy rates broken down by level of complexity and grammatical structure. Finally, we will present the results that emerged from the two sets of GLMMs.

4.1. Internal consistency of the SRT-EP

In order to assess the internal consistency of the task, we conducted two sets of Cronbach’s alpha reliability analyses on the items of the SRT: one set per measure (TS and TS&Gra). Within each set, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated not only for the whole sample (i.e., monolingual and bilingual children together), but also for each group of speakers separately. As shown in , the internal consistency was excellent under the two scoring methods for the full sample and each subsample.

Table 4. Reliability statistics for both scoring methods.

4.2. Performance in the SRT-EP

4.2.1. Descriptive statistics

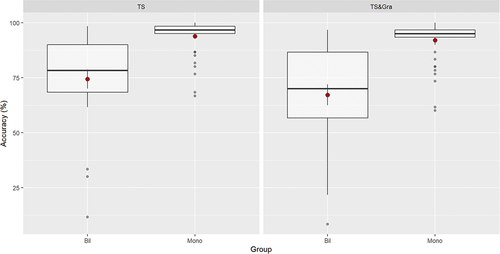

depicts the descriptive data of each group’s overall performance on the SRT by measure (i.e., TS and TS&Gra). A closer look at the boxplots shows that children’s accuracy on both measures tended to be higher and less variable in the monolingual group than in the bilingual one. Furthermore, we observe lower accuracy rates in the measure TS&Gra, compared to the TS one.

Figure 1. Overall performance (i.e., accuracy rate) on the SRT per scoring measure and group (the red dots and lines represent the mean and the standard error from the mean, respectively).

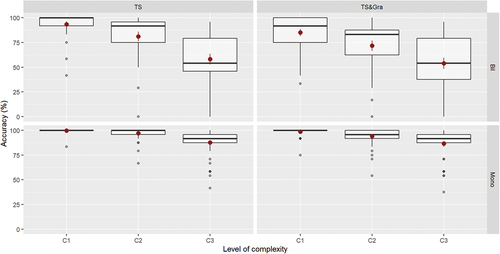

, in turn, illustrates each group’s performance across the three levels of complexity, also by measure. A visual inspection of the data shows that accuracy rates tend to decrease as the level of complexity of the structures included in the SRT increases and this occurs within each group and for the two scoring measures. Furthermore, the data display the same pattern observed for the children’s overall performance on the SRT, that is, in each level of complexity, the monolingual group presents higher accuracy scores and less variability than the bilingual group.

Figure 2. Performance (i.e., accuracy rate) on the SRT per level of complexity, scoring measure and group (the red dots and lines represent the mean and the standard error from the mean, respectively).

The children’s accuracy rates broken down by grammatical structure can be found in .

Table 5. Performance (i.e., accuracy rate) on the SRT structures per scoring measure and group.

4.2.2. Generalized linear mixed-effects model analyses

4.2.2.1 Set A

and report the outcome of the two generalized linear mixed-effects model analyses included in Subset A1, one for each scoring method. Regarding the measure TS (see ), the overall findings of its model are as follows: (i) there is a significant effect of level of complexity when level C2 is being contrasted with level C3, but not when it is being compared to level C1 (p = .059), showing that the log-odds of providing an accurate answer decrease from level C2 to level C3, but they do not significantly increase from level C2 to level C1; (ii) there is a significant effect of group, with the positive estimates showing that belonging to the monolingual group increases the log-odds of providing an accurate answer; and (iii) there is also a significant effect of age, showing that the log-odds of providing an accurate answer increase with age. We found no significant two-way or three-way interactions.

Table 6. Summary of the GLMM for the measure TS (Subset A1).a

Table 7. Summary of the GLMMs for the measure TS&Gra (Subset A1).a

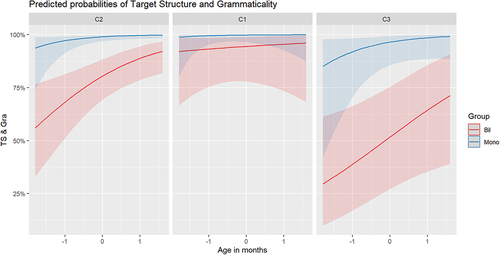

depicts the predicted probabilities, based on the model, of a correct response under the measure TS. It shows that, in the bilingual group, a change in age from 1SD below the mean to 1SD above the mean leads to an increase in the probability of observing an accurate answer of: 2% (from 98% to 100%) with respect to the structures of level C1; of 9% (from 86% to 95%) regarding the structures of level C2; and of 28% (from 45% to 73%) in relation to structures of level C3. As for the monolingual group, moving from 1SD below the mean to 1SD above the mean in age does not lead to an increase/decrease in the probability of observing a correct response in the structures of level C1 since monolingual children tend to perform at ceiling in this level of the task; however, the probability of monolinguals producing an accurate answer increases by 1% (from 99% to 100%) among the items of level C2 and by 5% (from 94% to 99%) among the items of level C3.

Figure 3. Measure TS: predicted probabilities of an accurate answer plotted by age, group and level of complexity.

Concerning the overall findings of the model focused on the measure TS&Gra (see ), they are similar to the ones of the previous model, except for the fact that the effect of level of complexity is significant both when level C2 is being compared to level C3 as well as when it is being contrasted with level C1, revealing that the log-odds of producing an accurate response decrease from level C2 to level C3 but increase from level C2 to level C1.

illustrates the predicted probabilities of a correct response under the measure TS&Gra. It demonstrates that, in the bilingual group, a change in age from 1SD below the mean to 1SD above the mean leads to an increase in the probability of producing a correct response of: 2% (from 93% to 95%) regarding the structures of level C1; of 21% (from 68% to 89%) in relation to the structures of level C2; and of 25% (from 39% to 64%) with respect to the structures of level C3. Regarding the monolingual group, going from 1SD below the mean to 1SD above the mean in age increases the probability of observing an accurate answer by 1% (from 99% to 100%) among the items of level C1, by 3% (from 97% to 100%) among the items of level C2, and by 7% (from 92% to 99%) among the items of level C3.

Figure 4. Measure TS&Gra: predicted probabilities of an accurate answer plotted by age, group and level of complexity.

As a final step in the analyses of Subset A1, we calculated the Coefficient of Discrimination of each model, using the r2_tjur() function of the performance package (version 0.9.0; Lüdecke et al. Citation2021). The outcome revealed that the fixed effects account for 53% of the variation in the dependent variable TS and for 50% of the variation in the dependent variable TS&Gra.

With respect to the analyses performed in Subset A2, aimed at assessing the effects of group and age in each complexity level, and report the outcome of the GLMMs that were run for each measure per level of complexity. Regarding the measure TS (see ), the overall findings of its models are as follows: (i) for level C1, the predictors age, group, and the two-way interaction age*group are non-significant, meaning that, among the items of level C1, the log-odds of observing a correct response do not change as a function of the children’s age (for both monolinguals and bilinguals) nor as a function of the group they belong to; (ii) for levels C2 and C3, there is a significant effect of age and of group, with the positive estimates showing that, among the items of both level C2 and level C3, children perform better with increasing age and belonging to the monolingual group increases the log-odds of giving an accurate response. Furthermore, the lack of interaction between age and group indicates that the effect of age holds for both groups.

Table 8. Summary of the GLMMs for the measure TS (Subset A2).a

Table 9. Summary of the GLMMs for the measure TS&Gra (Subset A2).a

As for the measure TS&Gra (see ), the findings of its models are similar to the ones found for the measure TS, except for the fact that there is a main effect of group among the items of level C1, meaning that the log-odds of providing a correct answer increase if children belong to the monolingual group.

The final step in this set of analyses also included the calculation of the Coefficient of Discrimination of each model, which revealed that, for the dependent variable TS, the fixed effects account for: 48% of the variation with the items of level C1, 46% of the variation with the items of level C2, and 54% of the variation with the items of level C3. As for the dependent variable TS&Gra, they account for: 33%, 44%, and 55% of the variation with the items of level C1, C2, and C3, respectively.

4.2.2.2 Set B

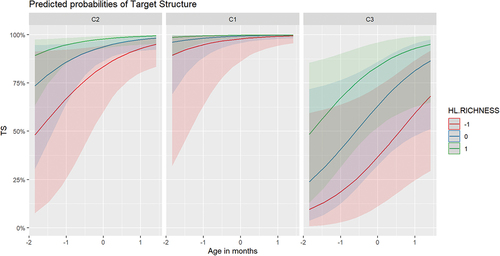

and , in turn, report the outcome of the two generalized linear mixed-effects model analyses included in Set B, which includes only the bilingual group. Regarding the measure TS (see ), the overall findings of its model are as follows: (i) there is a significant effect of age and level of complexity in the bilingual group even when language experience variables are taken into account, meaning that the log-odds of producing a correct answer not only increase with age, but they also decrease as the level of difficulty of the targeted structures increases (i.e., they increase from level C2 to level C1 and decrease from level C2 to level C3); and (ii) there is a significant effect of the richness of the HL input, with the positive estimate showing that being exposed to more diverse HL input increases the log-odds of giving an accurate response, even when age and level of complexity of the stimuli are controlled for. No significant effect of cumulative amount of HL exposure was found.

Table 10. Summary of the GLMMs for the measure TS (Set B).a

Table 11. Summary of the GLMM for the measure TS&Gra (Set B).a

displays the predicted probabilities, based on the model, of obtaining a correct response under the measure TS. Focusing our analysis on the language experience predictor that reached significance (i.e., richness of the HL input) and taking as reference mean-aged children, one can see that a change in HL.RICHNESS from 1SD below the mean to 1SD above the mean leads to an increase in the probability of observing an accurate answer of: 2% (from 98% to 100%) in relation to the structures of level C1; of 14% (from 84% to 98%) with respect to the items of level C2; and of 47% (from 37% to 84%) concerning the items of level C3.

Figure 5. Measure TS (Set B): predicted probabilities of an accurate answer plotted by age, richness of the HL input (HL.RICHNESS) and level of complexity.

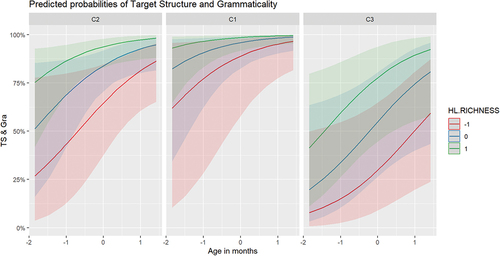

As far as the overall findings of the model focused on the measure TS&Gra (see ) are concerned, they are in line with the ones of the previous model, that is, there is a significant effect of age, level of complexity, and richness of the HL input. This means that the log-odds of observing a correct response increase with growing age and with greater exposure to more diverse and complex HL input, on the one hand, and decrease as the complexity level of the stimuli increases, on the other hand. The model did not find a significant effect of cumulative amount of HL exposure.

illustrates the predicted probabilities, derived from the model, of an accurate answer under the measure TS&Gra. Focusing again on the predictor richness of the HL input and also taking as reference the values for mean-aged children, one can see that moving 1SD below the mean to 1SD above the mean in HL.RICHNESS leads to an increase in the probability of observing a correct response: of 10% (from 89% to 99%) among the items of level C1; of 29% (from 65% to 94%) among the items of level C2; and of 48% (from 30% to 78%) among the items of level C3.

Figure 6. Measure TS&Gra (Set B): predicted probabilities of an accurate answer plotted by age, richness of the HL input (HL.RICHNESS) and level of complexity.

Finally, the results of the Coefficient of Discrimination of each model revealed that the fixed effects account for 55% of the variation in the dependent variable TS and for 51% of the variation in the dependent variable TS&Gra.

5. Discussion

In the present study, we tested EP monolingual and EP-German bilingual children’s language proficiency with a SRT developed for EP on the basis of the LITMUS-SRT version. The results give us interesting insights into the use of this instrument to capture the particularities of the children’s language proficiency as well as into the way individual differences in the performance of the child HSs are modulated by language experience variables. We discuss the results following the research questions listed in Section 3.1.

The first question (RQ1) asked whether, in general, EP-speaking children score differently on the structures belonging to the different levels of complexity, as shown extensively for other languages (Ibrahim & Hamann Citation2017, Komeili et al. Citation2020, Marinis & Armon-Lotem Citation2015, among others). The results indicate that this is clearly the case (see ). Both the monolingual and the bilingual children perform almost at ceiling with respect to structures classified as belonging to the lowest level of complexity (C1), in particular if the scoring method TS is applied. The scores decrease in level C2, particularly in the bilingual group, and are even lower in the highest level of complexity (C3). The GLMMs of Subset A1 identify, for both scoring methods, the level of complexity as significant predictor, with the probability of scoring lower decreasing significantly from level C2 to level C3. The difference between C1 and C2 is only captured by the more rigorous TS&Gra scoring method. This indicates that the SRT-EP indeed captures the particularities of EP children’s language development, being sensitive to different degrees of complexity of the linguistic properties.

Furthermore, the SRT-EP captures not only the differences reflected by the different degrees of complexity, but also the inter-group dissimilarities. Answering the second research question (RQ2), we can, in fact, conclude that the child heritage speakers of EP perform lower than their age-matched monolingual peers, mainly when they are assessed by means of the measure TS&Gra. The GLMMs in Subset A1 identify group as significant predictor of children’s accuracy scores, with a higher probability of monolingual children giving an accurate answer compared to bilingual children. The between-group differences are further supported by the GLMMs in Subset A2, which found a group effect within each complexity level under the measure TS&Gra and within levels C2 and C3 under the measure TS. These outcomes are, thus, in line with those of many other studies that applied SRTs to test bilingual children’s language proficiency and that have found that, in the HL, bilinguals were outperformed by their monolingual peers (e.g., Haman et al. Citation2017, Meir et al. Citation2016, and others).

A detailed look at the mean accuracy rates of the various structures corroborates the results obtained in the analyses of Subset A2 and gives us a more thorough understanding not only of the between-group differences, but also of the structures that stand out as being particularly challenging for the heritage bilingual children. As shown in , in the monolingual group, the accuracy rates for non-finite complement clauses (CompNonFinite), simple clauses with periphrastic future (PeriFuture), and with Simple Past tense (Preterite) lie between 98.8% and 100% for the TS scoring method and between 97.7% and 99.4% if the TS&Gra method is applied. This indicates that these structures have been fully acquired by most monolinguals. With respect to their bilingual counterparts, despite the fact that these speakers present slightly lower accuracy rates and more variation in their scores (i.e., TS: 88-98%; TS&Gra: 81-89%), one may also conclude that these structures have also been acquired by the majority of the bilingual children, providing evidence that EP-speaking children acquire these grammatical structures in pre-school age, regardless of growing up in a monolingual or in a bilingual context. The picture changes somehow when we look at the structures belonging to the level C2. While the mean scores in the monolingual group are still very high for all structures and for both scoring methods (above 89.5%, even though lower than at C1), the bilingual children reveal difficulties with respect to various structures belonging to level C2. Particularly challenging for the child heritage speakers of EP are the sentences with the subjunctive and ‘who-object’ wh-questions. A look at the C3 structures indicates that these are even more demanding for the bilingual children, with monolinguals also performing lower in this level of complexity. Sentences with accusative clitics, both in enclisis and in proclisis position, are the most challenging for the bilingual children, displaying the lowest accuracy rates (29% and 37%). This coincides with the structures displaying the lowest accuracy rates in the monolingual group, whose accuracy rates range from 63.4% to 75%. Conditional clauses, which-object questions and long passives, in contrast, displayed results above 90% in the monolingual group, but proved to be difficult structures for the bilinguals, whose highest accuracy rate in these structures is 68%. Against our expectation, object relatives were not problematic for either group, with bilinguals ranging from 86% to 89%, and monolinguals being almost at ceiling (99.4%). There are several factors that may explain why object wh-questions were more difficult than object relatives for the heritage bilinguals: object wh-questions in Portuguese require that the C position is filled with the grammaticalized “é que” expression. This is quite language-specific. Relative clauses, on the contrary, do not have this language-specific feature. A qualitative analysis of children’s non-target productions shows that, although some children make errors that correspond to theta-role reversal and are, thus, attributable to problems with intervention, most errors are related to difficulties in the production of the “é que” expression that fills the C position. Therefore, we believe that the difference between relatives and wh-questions in children’s productions may be due to late mastery of this specific grammatical feature.

In sum, the analysis of the various accuracy scores per structure confirms findings from previous studies which showed that heritage bilinguals demonstrate protracted development mainly in late acquired (and more complex) structures (see Tsimpli Citation2014). For child heritage speakers of EP, these structures encompass clauses with subjunctive mood (as already shown by Flores et al. Citation2017, Citation2019 for mood selection in complement clauses), and with clitics in various positions, as shown in several studies with bilinguals (Costa et al. Citation2016, Flores & Barbosa Citation2014; Flores et al. Citation2016; Nardelli & Lobo Citation2018; Rinke & Flores Citation2014; Tomaz et al. Citation2019, Citation2020). Additionally, our results show that some structures that are already acquired at this age for most monolingual children can still be problematic for bilinguals: these include conditional clauses, long passives and which-object questions.

Our third research question (RQ3) asked whether the children’s current age predicts their accuracy scores, thus showing language development with increasing age, even in primary school-aged children. Similar to previous findings from studies on bilingual and monolingual children, which were conducted with either SRTs (e.g., Komeili et al. Citation2020, Paradis et al. Citation2021, Taha et al. Citation2021, Theodorou et al. Citation2017) or other grammatical assessment tasks (e.g., Cadório et al. Citation2014, Flores et al. Citation2017, Torregrossa et al. Citation2023), the results from the current study reveal that the investigated monolingual and bilingual EP-speaking children perform better with growing age, that is, as shown in the GLMMs of Subset A1, the log-odds of giving an accurate answer increase as children grow older (but see, e.g., Fleckstein et al. Citation2018 for different outcomes). Moreover, the GLMMs of Subset A2, focused on the children’s accuracy by complexity level, together with the predicted probabilities derived from the GLMMs of Subset A1 (plotted by age, group and level of complexity) indicate, on the one hand, that the effect of age becomes more visible as the level of difficulty increases, and, on the other hand, that it is larger for the bilingual children (see and ). In a nutshell, these results not only suggest a similar qualitative trend in grammatical development for both monolingual and bilingual children as a function of age, but they also support the assumption that a heritage language develops through the whole childhood, as long as heritage children maintain regular contact with their heritage language—even in cases of gradual input reduction due to schooling in the majority language (Rodina et al. Citation2023). Corroborating the results from previous studies (Flores & Barbosa Citation2014; Flores et al. Citation2017, Citation2020; Torregrossa et al. Citation2023), our results on EP-speaking heritage bilinguals do not support the idea of stagnation or language attrition in heritage language development in childhood.

With respect to our fourth research question (RQ4), it investigated the role that language experience variables, such as cumulative amount of HL exposure and richness of the HL input, play in bilingual children’s performance in the task. The analyses performed in Set B reveal both expected and unexpected results. On the one hand, they show that, for both measures (TS and TS&Gra), the greater the diversity and complexity of the HL input the bilingual children are exposed to through certain activities and interactions, the more accurate are their responses in the SRT. This outcome is in line with previous research that shows a positive relationship between richness of the HL environment and HSs’ performance not only in experimental tasks aimed at assessing HL morphosyntactic (e.g., Ibrahim et al. Citation2020) and narrative abilities (e.g., Jia & Paradis Citation2015), but also in tasks aimed at evaluating HL vocabulary knowledge (e.g., Pham & Tipton Citation2018). On the other hand, our results further demonstrate that cumulative amount of HL exposure, a language experience variable that has been found to affect HSs’ performance in tasks evaluating either HL morphosyntactic (e.g., Mitrofanova et al. Citation2018, Rodina & Westergaard Citation2017) or lexical knowledge (e.g., Haman et al. Citation2017, Tao et al. Citation2021), does not emerge as a significant predictor of the bilingual children’s accuracy once variables such as age, complexity level, and HL richness are taken into account. Taken together, the outcomes of the GLMMs focused on the potential predictors of individual differences in the bilingual group indicate that contact with diverse sources of HL input, that is, media, HL-speaking friends, sociocultural activities in the immigrant community, and HL formal instruction, is a better predictor of the syntactic abilities of child HSs of EP than cumulative amount of HL exposure within the home. This could be explained by the fact that HL input at home is usually restricted to informal spoken registers and to a small number of interlocutors—sometimes, to just one of the parents. As stated by Polinsky (Citation2015:10), the HL input HSs receive at home “is not representative of the speech of the entire native-speaking population, nor does it cover all the possible contexts in which a language can be used.” Moreover, depending on the background of the migrant families, the verbal productions of their members may exhibit traces of language attrition and/or other effects of prolonged language contact with the societal language (Pascual y Cabo & Rothman Citation2012). Bearing this in mind, it may come to no surprise that HSs who are exposed to more diverse, complex and formal HL input in their daily lives perform better in the SRT than their counterparts whose language exposure comes from fewer sources of HL input.

Finally, we asked which scoring method, TS or TS&Gra, is more fine-grained in capturing performance differences in the monolingual and bilingual groups. Results show that children have lower accuracy scores if we apply the TS&Gra scoring method, which seems to indicate that this scoring method is more conservative than the TS one. This is particularly relevant in the bilingual group, where the TS&Gra scoring is more fine-grained at identifying children with lower proficiency levels, who produce ungrammatical sentences. We would, thus, recommend using this scoring method in future studies.

To close this discussion, the results of the Cronbach’s alpha reliability analyses on the items of the SRT reveal high internal consistency of the task (see ) both for the whole sample (i.e., monolingual and bilingual children together), as well as for each group separately. This confirms that the SRT presented in this study is internally consistent and suitable to test EP-speaking children’s language proficiency, at least in the age span between 6 and 10 years. In the bilingual group, it allows us to capture developmental differences between the bilingual children regarding their HL, caused by age and by diverse input experiences. In the monolingual group, even though the accuracy rates are high and many children perform at ceiling with respect to less complex structures, it still captures performance differences caused by age, thus showing that this task is useful to evaluate children’s knowledge of more complex structures. Testing of younger monolingual children will presumably reveal lower accuracy rates.

6. Conclusion

Overall, our results show that the EP version of the SRT may be used as an assessment tool for both monolingual and bilingual children’s language abilities and is able to discriminate between different levels of proficiency according to the complexity level of the structures. In accordance with previous studies, our research was also able to identify areas that are more vulnerable in bilingual development compared to the monolingual one and areas that stabilize early. In addition, the three complexity levels, defined for this task on the basis of previous findings from studies on monolingual and bilingual acquisition of EP, are proven to accurately capture the particularities of the linguistic system of EP.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the children and parents who participated in this study. We would also like to thank Camões, Institute of Cooperation and Language I.P. and all the individuals who helped us recruiting participants both in Portugal and in Germany, as well as Jacopo Torregrossa for helpful advice during data analysis. We extend special thanks to João Costa and Fernanda Pratas, who, in collaboration with Maria Lobo, developed the first version of this task within the COST ACTION IS0804. Finally, we would also like to thank not only Theo Marinis and all members of the aforementioned project for their ideas, support, and fruitful discussions, but also the participants of the Workshop LITMUS Sentence Repetition Task, held at University of Konstanz in 2019, for their valuable comments on the current study.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly.

Supplementary Information

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10489223.2024.2346586

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Sentence repetition is claimed to be a multifaceted task which involves linguistic representations in long-term memory (also called language knowledge, Ebert Citation2014) and the maintenance of information in short-term memory or working memory (Riches Citation2012). The role that each type of memory plays in SRTs is part of an ongoing debate, with some authors highlighting the association between sentence repetition and linguistic processing and other authors highlighting its relationship with working memory capacity (see Ebert Citation2014, Okura & Lonsdale Citation2012, Riches Citation2012). Nevertheless, despite the varying emphasis given to the role of long-term memory, linguistic processing and working memory capacity, SRTs, when properly constructed (e.g., sentences being long enough to exceed memory capacity and, consequently, disallow passive copying), have been argued to draw on linguistic knowledge (see discussion in Marinis & Armon-Lotem Citation2015).

2. Proclisis triggers include negation, negative subjects, some preverbal adverbs, some quantified subjects, complementizers, preposed wh-constituents, among others.

3. This may be different for coordination structures without connectors. For instance, juxtaposition contexts that express causal relations have been shown to be more demanding than coordinated sentences with connectors, as well as causal subordinate clauses (Aguiar Citation2017).

4. In the parental questionnaire, the caregiver estimated, on a 5-point scale, the frequency of HL use from each household member to the child for several age periods of the child’s life (i.e., from birth to current age). The scale was: Never (0%) = 0; Seldom (25%) = 0.25; Sometimes (50%) = 0.50; Usually (75%) = 0.75; Always (100%) = 1. For each age period, the quantity of language exposure within the home was calculated by totaling the responses and then dividing the resulting value by the number of household members, except for the child him-/herself and siblings under the age of two years. With these data, the quantity of HL input for each year of the child’s life was determined and converted into months of exposure, which were then summed up to obtain the child’s total amount of HL exposure in months over time within the household (for further details on calculation method, see Correia & Flores Citation2021).

5. Richness of the HL input was calculated based on the child’s language experience in four domains of his/her daily life, namely: (i) frequency of weekly contact with the HL by means of media-related activities (e.g., watching television, reading books, etc.); (ii) participation in leisure and sociocultural activities promoted by the Portuguese migrant community; (iii) HL use in the host country when among EP-speaking friends; and (iv) attendance of Portuguese classes. Points were given to each domain and then summed up and divided by the maximum possible score. The resulting value may range from 0 to 1; the closer the value is to 1, the greater the diversity and complexity of the HL input the child receives on a daily basis (for further details on calculation method, see Correia & Flores Citation2021).

6. The initial version was piloted with pre-schoolers. Since the present version targeted older children, we believed it would be important to include a set of more demanding structures.

7. The transcribed responses were scored by the first author and checked by the co-authors.

8. Note that children were not penalized for replacing the conditional with the imperfect indicative in the conditional clauses, for example:

9. In both scoring schemes, allowances were given for common phonological reductions (e.g., tivesse for estivesse), and expansions (e.g., por a for pela).

10. When using simple contrast coding, the reference level is coded as -1/3 and the level that it is being compared to is coded as 2/3. For example, regarding the variable level of complexity, if one is comparing level C1 to level C2 and level C1 is the reference level, then the coding is 2/3 for level C2 and -1/3 for all other levels. Similar to dummy contrast coding, simple contrast coding compares each level to the reference level. However, in contrast to the former, the intercept of the latter represents the grand mean. Moreover, simple contrast coding has the advantage that “factors outside of interactions can be interpreted as main effects” (Tilmatine et al. Citation2021).

References

- Adani, Flavia, Heather K. J. van der Lely, Matteo Forgiarini & Maria Teresa Guasti. 2010. Grammatical feature dissimilarities make relative clauses easier: A comprehension study with Italian children. Lingua 120(9). 2148–2166. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2010.03.018.

- Agostinho, Celina. 2014 The acquisition of control in European Portuguese complement clauses. Lisbon: University of Lisbon dissertation.

- Agostinho, Celina. 2020 The acquisition of the verbal passive in European Portuguese. Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona dissertation.

- Aguiar, Joana. 2017 Mecanismos de conexão frásica: a importância das variáveis sociais [Phrasal connection mechanisms: the importance of social variables]. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Universidade do Minho, Portugal.

- Almeida, Laetitia de, Sandrine Ferré, Eléonore Morin, Philippe Prévost, Christophe dos Santos, Laurie Tuller, Racha Zebib & Marie-Anne Barthez. 2017. Identification of bilingual children with specific language impairment in France. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 7(3–4). 331–358. doi:10.1075/lab.15019.alm.

- Andreou, Maria, Jacopo Torregrossa & Christiane Bongartz. 2021. Sentence Repetition Task as a measure of language dominance. In Danielle Dionne and Lee-Ann Vidal Covas (eds.), Proceedings of the 45th annual Boston University Conference on Language Development, 14–25. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

- Armon-Lotem, Sharon, Jan de Jong & Natalia Meir, eds. 2015. Assessing Multilingual Children. Disentangling Bilingualism from Language Impairment. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. doi:10.21832/9781783093137.

- Baião, Vera & Maria Lobo. 2014. Aquisição de interrogativas preposicionadas no português europeu [Acquisition of prepositional interrogatives in European Portuguese]. In António Moreno, Maria de Fátima Silva, Isabel Falé, Isabel Pereira & João Veloso (eds.), Textos Selecionados XXIX Encontro Nacional da APL, 57–70. Coimbra: APL.

- Barbosa, Pilar, Cristina Flores & Cátia Pereira. 2018. On subject realization in infinitival complements of causative and perceptual verbs in European Portuguese. Evidence from monolingual and bilingual speakers. In Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes and Alejandro Cuza (eds.), Language acquisition and contact in the Iberian Peninsula, 125–158. Berlin, Boston: Mouton de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9781501509988-006.

- Batalha, Joana, Maria Lobo, Antónia Estrela & Bruna Bragança. 2022. Desenvolvimento sintático em produções escritas de crianças de 1.° ciclo [Syntactic development in written productions of primary school children]. Revista da Associação Portuguesa de Linguística 9.

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Maechler, Ben Bolker & Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67(1). 1–48. doi:10.18637/jss.v067.i01.

- Bentea, Anamaria. 2017. Comprehension of wh-questions in child Romanian: A case about case and lexical restriction. In Jiyoung Choi, Hamida Demirdache, Oana Lungu & Laurence Voeltzel (eds.), Language Acquisition and Development: Proceedings of GALA 2015, 1–19. Newcastle upon Tyne: CSP.

- Bentea, Anamaria, Stephanie Durrleman & Luigi Rizzi. 2016. Refining intervention: The acquisition of featural relations in object A-bar dependencies. Lingua 169. 21–41. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2015.10.001.

- Bever, Thomas G. 1970. The cognitive basis for linguistic structures. In John R. Hayes (ed.), Cognition and the development of language, 279–362. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

- Blume, María & Barbara C. Lust. 2017. Research methods in language acquisition: Principles, procedures and practices. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Borer, Hagit & Kenneth Wexler. 1987. The maturation of syntax. In Thomas Roeper and Edwin Williams (eds.), Parameter setting, 123–172. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-3727-7_6.

- Cadório, Inês, Maria Lousada, Melina Aparici & Andreia Hall. 2014. Assessment of morphosyntactic development in European Portuguese-speaking children. Folia phoniatrica et logopaedica 66(6). 251–257. doi:10.1159/000368333.

- Cerejeira, Joana. 2009. Aquisição de interrogativas de sujeito e de objecto em português europeu [Acquisition of subject and object interrogatives in European Portuguese]. Lisbon: NOVA University of Lisbon dissertation.

- Chiat, Shula, Sharon Armon-Lotem, Theodoros Marinis, Kamila Polišenská, Penny Roy & Belinda Seeff-Gabriel. 2013. The potential of sentence imitation tasks for assessment of language abilities in sequential bilingual children. In Virginia C. Mueller Gathercole (ed.), Bilinguals and assessment: State of the art guide to issues and solutions from around the world, 56–89. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Corrêa, Letícia M., Marina R. A. Augusto & João C. de Lima-Júnior. 2017. Passivas [Passives]. In Maria João Freitas and Ana Lúcia Santos (eds.), Aquisição de língua materna e não materna: Questões gerais e dados do português, 201–224. Berlin: Language Science Press.

- Correia, Liliana, & Cristina Flores. 2021. Questionário sociolinguístico parental para famílias emigrantes bilingues (QuesFEB): uma ferramenta de recolha de dados sociolinguísticos de crianças falantes de herança [Sociolinguistic parental questionnaire for bilingual migrant families (QuesFEB): a tool for collecting sociolinguistic data from heritage-speaking children]. Linguística. Revista de Estudos Linguísticos da Universidade do Porto 16. 75–102. https://ojs.letras.up.pt/index.php/EL/article/view/11021/10077

- Costa, Ana Luísa. 2010. Estruturas contrastivas: desenvolvimento do conhecimento explícito e da competência de escrita [Contrastive structures: the development of explicit knowledge and writing skills]. Lisbon: University of Lisbon dissertation.

- Costa, Ana, Nélia Alexandre, Ana Lúcia Santos & Nuno Soares. 2008. Efeitos de modelização no input: o caso da aquisição de conectores [Input modeling effects: the case of the acquisition of connectors]. In Sónia Frota and Ana Lúcia Santos (eds.), Textos Seleccionados do XXIII ENAPL, 131–142. Lisbon: Colibri.

- Costa, João, Alexandra Fiéis & Maria Lobo. 2015. Input variability and late acquisition: Clitic misplacement in European Portuguese. Lingua 161. 10–26. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2014.05.009.

- Costa, João & Maria Lobo. 2007. Clitic omission, null objects or both in the acquisition of European Portuguese? In Sergio Baauw, Frank Drijkoningen & Manuela Pinto (eds.), Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2005. Selected Proceedings of Going Romance, 59–71. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. doi: 10.1075/cilt.291.06cos.

- Costa, João, Maria Lobo & Fernanda Pratas. 2016. Clitic production by Portuguese and Capeverdean children: omission in bilingualism. Probus 28(2). 271–291. doi: 10.1515/probus-2014-0015.

- Costa, João, Maria Lobo & Carolina Silva. 2011. Subject-object asymmetries in the acquisition of Portuguese relative clauses: Adults vs. children. Lingua 121(6). 1083–1100. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2011.02.001.

- De Houwer, Annick. 2009. An introduction to bilingual development. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. doi:10.21832/9781847691705.