ABSTRACT

This study reviewed the mobile technology-supported music education (MTSME) studies published in several academic databases, namely Scopus, WOS, ERIC, and RILM, from 2008-2019. Based on the technology-based learning model, the application domains, research issues, sample groups, research methods, adopted devices, and learning strategies were examined. In addition, visual categorization analysis was conducted to further analyze the keywords adopted in the studies. The results show that the number of MTSME studies increased in the time period. It was also found that a majority of studies mainly focused on learner perceptions (e.g. learning reception, learning attitude, and learning motivation). Tablet computers were the most frequently adopted mobile devices. In terms of learning strategies, guided learning, project-based learning, and inquiry-based learning were extensively used in the MTSME studies. In addition, the results of the keyword analysis showed three thematic clusters of MTSME studies, namely “mobile technology-supported teaching management and learning design,” “developing appropriate music educational resources for different educational levels,” and “mobile technology facilitated learning motivation in music education.” According to the research results, several suggestions for future research are proposed.

1. Introduction

Learning music is a skill-oriented and challenging learning process, in which learners not only need to practice repeatedly following the advice of experienced tutors to master performing skills, but they are also required to comprehend and learn to apply music theories. Differing from other courses such as mathematics, language, and science that focus on memorizing, understanding, and applying knowledge in the learning process, there is an emphasis on improvizational performance and musical creativity in learning music (Azzara, Citation1993). With the rapid development of information and communication technology (ICT), the relationship between technology and music education has begun to receive attention from musicians, music educators, and music practitioners (Crawford, Citation2017; Nart, Citation2016; Savage, Citation2007). Music teachers have attempted to adopt various technologies in music curricula, such as desktop computers and mobile devices (Guillén-Gámez et al., Citation2018; Webster, Citation2007).

Researchers have indicated that emerging technologies have different impacts on music education from many perspectives. In general, the ever-changing emerging technologies have revolutionized music pedagogy, including instruction methods, feedback mechanisms, and evaluation approaches (Johnson et al., Citation2020). In traditional music instruction, it is almost impossible for teachers to provide instant feedback on individual students’ after-class practice. This implies that students have fewer opportunities to receive comments from others or to compare their own performance with that of others. With the help of computer and network technologies, learners are able to compare their own performance with that of others, and to receive instant feedback from others via network communications, implying more opportunities to think in depth and to make reflections (Hanrahan et al., Citation2019; Williams, Citation2014). Several studies have further indicated that integrating technology into music education not only enhances students’ performance (Chen et al., Citation2020), but also improves their attitudes towards learning music (Ho, Citation2004), their interest in learning music (Kim, Citation2013), and their learning engagement in music classes (Crow, Citation2006). Researchers have further indicated that it is important for teachers to consider integrating effective teaching strategies and ICT technologies into performing arts courses (Reeves et al., Citation2017). In the past decade, researchers have attempted to apply technologies to music education, and have reported the positive impacts of the approach, such as teachers’ technology acceptance (Eyles, Citation2018) as well as students’ learning performances and motivation (Chen, Citation2020).

Among the various technologies, mobile technologies have unique advantages for music teaching and learning due to their convenience, connectivity, personalization and interaction. Teachers and learners have therefore been attracted to adopting mobile technologies to enhance and innovate music education (Crawford & Southcott, Citation2017; Terras & Ramsay, Citation2012). Researchers have indicated that integrating mobile technologies into music education could benefit learners in various dimensions, making them worth investigating (Martin & Ertzberger, Citation2013). Understanding the status and future trends of MTSME is important for educators and researchers; however, there is a dearth of reviews on this topic. Therefore, this study conducted a systematic review on MTSME based on the technology-based learning review model proposed by Lin and Hwang (Citation2019) by searching the Scopus, WOS, ERIC, and RILM databases to answer the following research questions. To address this issue, in this study, the following research questions are investigated by analyzing the relevant publications from 2008-2019.

What are the main application domains for MTSME?

What are the research methods used in MTSME?

What are the sample groups in the MTSME research?

What types of mobile devices have been adopted in MTSME?

What are the learning strategies used in MTSME?

What are the main research issues for MTSME?

What are the main keywords for MTSME?

2. Literature review

According to the definition of Hwang et al. (Citation2008), mobile learning is a pedagogical model in which learning is facilitated by mobile technologies, and learners can learn anywhere and anytime with the support of mobile technologies. Nowadays, it is easy for most learners to have access to mobile devices such as smartphones or tablets. This opens up the possibility of integrating mobile technologies into teaching and learning. Previous studies have shown that mobile technology-supported learning has great potential to improve students’ learning achievements (Bano et al., Citation2018; Han & Shin, Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2009) and positively affects learners’ learning attitude (Hwang & Chang, Citation2011). In addition, some studies have also shown that mobile learning facilitates the transformation of instructors’ and learners’ roles and helps learners to change from being passive to active learners (Hsia & Sung, Citation2020; Hwang & Chang, Citation2021).

In recent years, educators and researchers have investigated the use of different mobile devices to support music learning. Researchers used an interactive whiteboard to support students to learn basic music knowledge (Nolan, Citation2009); iPads have been adopted as simulated musical instruments for musicians in different places to organize a virtual live performance ensemble to facilitate instrumental music learning (Williams, Citation2014); researchers have also applied educational robots for melodic learning (Chou & Chu, Citation2017). In addition to the use of different types of mobile devices in music education, researchers have further combined different strategies (e.g. game-based learning) with music learning to investigate their effects on developing musical knowledge and skills (Jenson et al., Citation2016). In addition to the discussion of learning achievements in MTSME, researchers have also explored the effects of mobile learning on students’ learning motivation for popular music composition (Chen, Citation2020). Recently researchers have begun to pay more attention to the music learning experience with technology and to further explore key elements of application design to influence user satisfaction (Burton & Pearsall, Citation2016; Moreno, Citation2014). Researchers have also investigated music educators’ technology preference for adopting specific technology to teach or learn music (Waddell & Williamson, Citation2019).

Over the past decades, many findings of reviews on mobile learning across ages and subjects have provided researchers with important information to better understand the use of mobile devices in educational settings. In terms of age group, some researchers have reviewed articles on K-12 students engaged in mobile learning from 2007 to 2012 (Liu et al., Citation2014); researchers have also conducted a systematic review of emerging articles on mobile learning in higher education from 2010–2016 (Crompton & Burke, Citation2018); several researchers have reviewed articles on mobile learning including K-12, higher education, and adult learners from 2001–2010 (Bano et al., Citation2018; Crompton et al., Citation2016; Hwang & Tsai, Citation2011). In terms of subjects in mobile learning, researchers have reviewed articles on mobile technology in various fields such as science (Zydney & Warner, Citation2016), mathematics (Bano et al., Citation2018), language learning (Elaish et al., Citation2019), medical and nursing (Lall et al., Citation2019), libraries (Tu & Hwang, Citation2020), and so on. The use of mobile technology in music education can not only innovate traditional music instruction through non-traditional instrument simulations that allow learners to play instruments on mobile devices such as tablets, but can also contribute to increased learner interest and motivation through combining music education and mobile technology (Chen, Citation2020). It can be seen that exploring the impact of mobile technologies on music education is a valuable research topic, and understanding the current status and future trends of MTSME is of great significance for future research in music education. Thus, this current study analyzes the trends of MTSME, including music theory and music performance, and provides recommendations for future researchers.

3. Research methods

3.1. Resources

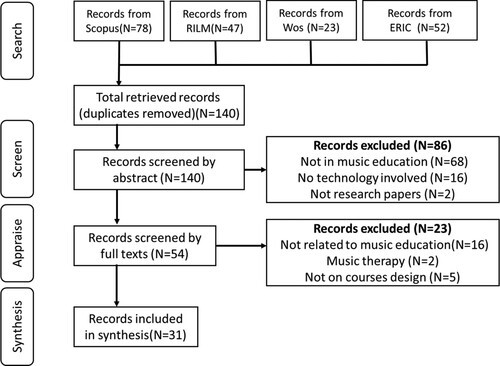

Using the databases of the Scopus, RILM, WOS, and ERIC, relevant journal articles on MTSME from 2008 to 2019 were searched. The search terms included mobile learning (“mobile learning” or “m-learning” or “location-aware” or “ubiquitous learning” or “iPad” or “hand-held” or “tablets” or “wireless learning” or “context-aware” or “digital learning” or “situated learning” or “u-learning” or “m-learning”), music education (“music” or “musicians” or “musical”) and education setting (“learning” or “education”). By searching for these terms in article titles, keywords, and abstracts, a total of 200 articles were identified. Excluding those articles that were duplicated between databases, 140 remained. By reading the titles and abstracts, 54 articles were retained after excluding articles that did not employ mobile technology, were not related to music education, or were non-research articles. Through reading the full texts, articles only related to music therapy or those that did not mention course design were excluded. Finally, 31 articles were further analyzed, as shown in .

3.2. Data distribution

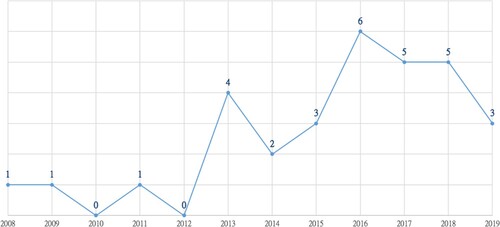

shows the publication situation of relevant articles on MTSME from 2008 to 2020. In order to indicate different stages of mobile technology and development, we analyzed the relevant articles on MTSME in two stages from 2008 to 2013 and 2014–2019 by referring to Lai (Citation2020) and Yang et al. (Citation2020). A total of seven articles were published in 2008–2013 compared with 23 in 2014-2019, showing the increasing number of studies in recent years.

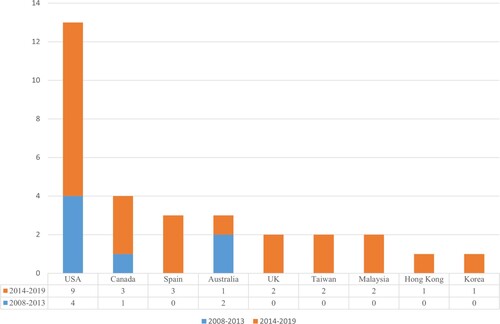

shows the distribution of publications on MTSME by countries or regions (counting the first author only). The top three countries or regions were the United States (13 articles), Canada (4 articles), Spain (3 articles), and Australia (3 articles). From 2008 to 2013, the top two countries or regions were the United States (4 articles) and Australia (2 articles). From 2014 to 2019, the top three countries or regions were the United States (9 articles), Canada (3 articles), and Spain (3 articles).

3.3. Theoretical model and coding schemes

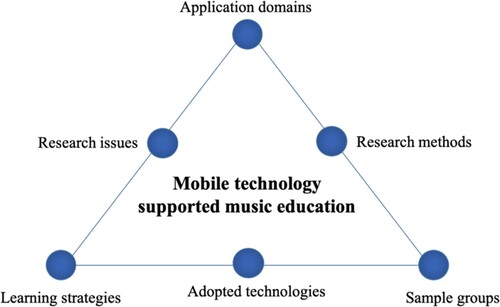

Based on the technology-based review model proposed by Lin and Hwang (Citation2019), the present study conducted a comprehensive review of MTSME with six categories: application domains, research issues, research methods, adopted technologies, sample groups, and learning strategies, as shown in .

The coding process was carried out by two experienced researchers in mobile learning. The two researchers discussed the coding and resolved any disagreement on certain items. The specific codes are described as follows.

Application domains

With reference to the research framework on musical learning proposed by Kelleher (Citation2015), this study generally divides musical learning into skills acquisition and conceptual learning. Conceptual learning includes aural knowledge and theoretical knowledge, and skills acquisition includes composing and improvising, listening and responding, performing and mixed.

Research issues

According to Chang et al. (Citation2018), the research topics of this study are categorized into cognition, affect, skills, learning behaviors, correlation, trend analysis, and others.

Research method

With reference to McMillan and Schumacher (Citation2006, p. 12), the research methods used in this study are classified into three categories: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods.

Adopted types of mobile devices

In this study, the mobile devices used in music education are categorized into smart phones, interactive whiteboards, tablets, mixed, non-specific mobile devices, and no devices.

Sample group

By referring to Hsu et al. (Citation2012), the sample groups were divided into the following categories: preschoolers, elementary school students, junior and senior high school students, higher education students, teachers, adults/ working adults, non-specified, and no participants. Non-specified means that the participants in the study were not explicitly identified. No participant means that the study was conducted through surveys or interviews to investigate teachers’ or students’ conceptions of and opinions on learning with mobile technologies, or the analysis of future research trends in MTSME.

Learning strategies

The study refers to 10 commonly used learning strategies proposed by Lai and Hwang (Citation2015), including guided learning, peer assessment, video sharing, synchronous sharing, issue-based discussion, computers as mindtools, project-based learning, inquiry-based learning, contextual mobile learning, and game-based learning. Moreover, two additional items, “mixed” and “no learning strategy,” were added to refer to those studies using two or more learning strategies and no learning strategy (e.g. review studies), respectively.

4. Research results

4.1. Application domains

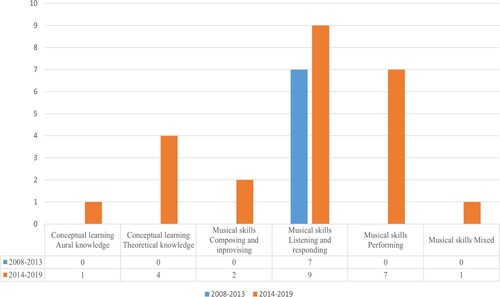

In terms of application, MTSME is mainly to facilitate student improvement in musical skills (77.41%) and conceptual learning (22.59%). According to , for musical skills, listening and responding (51.61%) was most investigated, followed by musical skills performing (22.58%), composing and improvising (6.45%), and musical skills mixed (3.23%). In terms of conceptual learning, more studies were conducted on theoretical knowledge (12.90%), and relatively fewer on aural knowledge (3.23%). During 2008-2013, mobile technology was firstly applied to improve learners’ listening and responding musical skills. From 2014 to 2019, research on MTSME in theoretical knowledge learning began to increase greatly. Furthermore, research on mobile technology to facilitate learners’ performing skills increased.

4.2. Research methods

shows that from 2008 to 2019, research on MTSME most frequently used qualitative methods (46.88%), followed by quantitative (31.25%), and mixed methods (21.88%). From 2008 to 2013, there were six articles using qualitative methods and one using mixed methods. From 2014 to 2019, studies using quantitative methods increased significantly (10 articles), followed by qualitative methods (9 articles) and mixed methods (6 articles). It can be seen that the current research on MTSME is mainly based on qualitative methods, and there is huge potential for research using quantitative methods in the future.

Table 1. Research methods.

4.3. Research sample groups

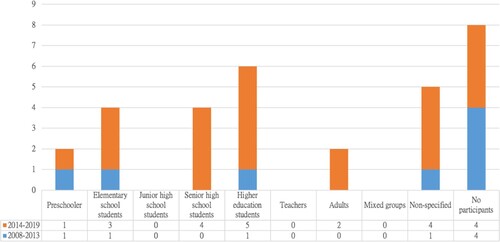

As indicates, for the sample groups in MTSME from 2008 to 2019, no participants (25.81%) was most common, followed by higher education students (19.35%), non-specified (16.13%), senior high school students (12.90%), elementary school students (12.90%), preschoolers (6.45%), and adults (6.45%).

From 2008 to 2013, studies involving no participants comprised the majority (4 articles), followed by preschoolers (1 article), elementary school students (1 article), higher education students (1 article), and non-specified (1 article). From 2014 to 2019, higher education students (5 articles) were the most common, followed by senior high school students (4 articles), non-specified (4 articles), no participants (4 articles), elementary school students (3 articles), adults (2 articles), and preschoolers (1 article). Compared with the period from 2008 to 2013, the number of studies increased most for senior high school students (4 articles) and higher education students (4 articles) from 2014 to 2019.

4.4. Mobile devices

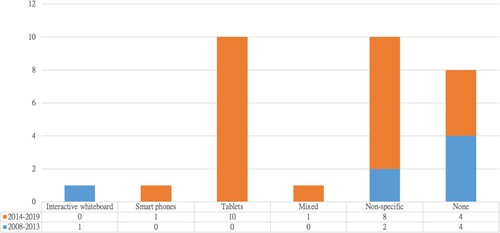

shows the distribution status of mobile devices adopted in each study. From 2008 to 2019, tablets (10 articles) and non-specified devices (10 articles) were the most common, followed by no mobile devices (8 articles), interactive whiteboard (1 article), smart phones (1 article) and mixed (1 article). From 2008 to 2013, there are four articles with no mobile devices, two with non-specified devices, and one with an interactive whiteboard. From 2014 to 2019, tablets (10 articles) were adopted most often in the studies, followed by non-specified devices (8 articles), no mobile devices (4 articles), smart phones (1 article), and mixed (1 article).

4.5. Learning strategies

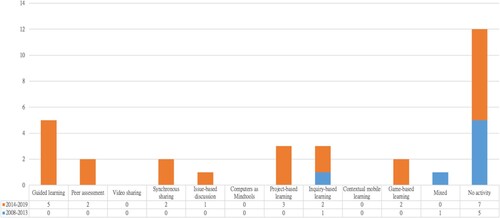

shows that 38.71% of studies on MTSME from 2008 to 2019 had no learning activities, mainly using surveys or interviews to investigate teacher and learner attitudes towards mobile learning or trend analysis. Among the 11 learning strategies, the most adopted strategies in sequence are guided learning (16.13%), project-based learning (9.68%), inquiry-based learning (9.68%), peer assessment (6.45%), synchronous sharing (6.45%), game-based learning (6.45%), issue-based discussion (3.23%), and mixed (3.23%). In addition, video sharing, computers as mindtools, and contextual mobile learning were not used in these studies. Therefore, there is still a large gap for integrating mobile learning activities into music education with appropriate learning strategies.

In the period of 2008–2013, the adopted learning strategies in sequence were inquiry-based learning (1 article) and mixed (1 article). From 2014 to 2019, the adopted learning strategies in sequence were guided learning (5 articles), project-based learning (3 articles), peer assessment (2 articles), synchronous sharing (2 articles), inquiry-based learning (2 articles), game-based learning (2 articles), and issue-based discussion (1 article). During this period, six learning strategies including guided learning, peer assessment, synchronous sharing, issue-based discussion, project-based learning, and game-based learning started to be employed.

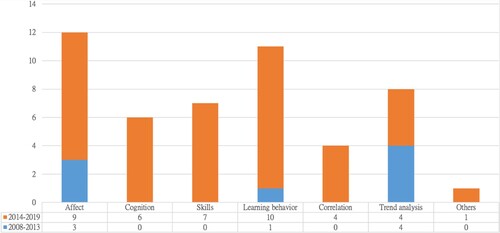

4.6. Research issues

The study examined 31 papers on the research issues of MTSME. shows the number of research issues in each period. It is indicated that studies on affect comprised the majority (12 articles). Following affect, studies on learning behavior also comprised a large proportion (11 articles). For instance, researchers adopted mobile technology to record participants’ training time and learning behaviors during the mobile learning activities (see A01, A02, A06, A07, A09, A11, A14, A21, A25, A27, A31 in the appendix). The third category was trend analysis (8 articles), followed by skills (7 articles), cognition (6 articles), correlation (4 articles), and other (1 article). At the same time, it was found that from 2014 onwards, the research issues on mobile learning in music education became more diverse. Compared with the period of 2008–2013, the number of studies exploring learning behavior increased significantly from 2014 to 2019, which indicated that researchers have been investigating the impacts of mobile technologies on assisting the training process and recording participants’ learning behaviors.

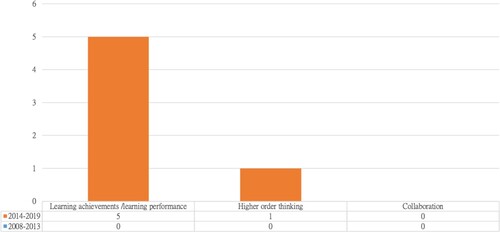

With regard to cognition, as indicated in , there is room for growth in research investigating the topic of cognition in MTSME. There were no studies on cognitive issues from 2008 to 2013. Learning achievement or learning performance by means of testing started to be discussed from 2014 to 2019 (5 articles) (see A2, A04, A10,A14, A25 in the appendix). Among the studies investigating the cognition aspect, the majority of researchers focused on student academic achievement and learning performance. It should be noted that higher order skills were investigated in one recent published article (see A04 in the appendix).

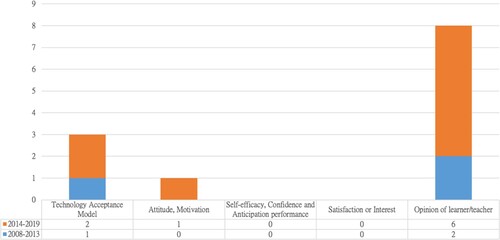

indicates the studies which investigate learner affect items. There are eight studies investigating participant learning opinions on mobile learning. There are three studies exploring the participants’ technology acceptance for mobile learning (see A09, A19, A31 in the appendix), and there is one study examining participants’ attitudes towards and motivations for mobile learning (see A21 in the appendix).

From 2008 to 2013, there were two studies on participants’ learning opinions about mobile learning, and one on participants’ technology acceptance for mobile learning. From 2014 to 2019, studies on participants’ learning opinions on mobile learning through interviews or surveys continued to be the most investigated (6 articles), followed by exploring participants’ technology acceptance for mobile learning (2 articles), and studies examining participants’ attitudes and motivations for mobile learning (1 article).

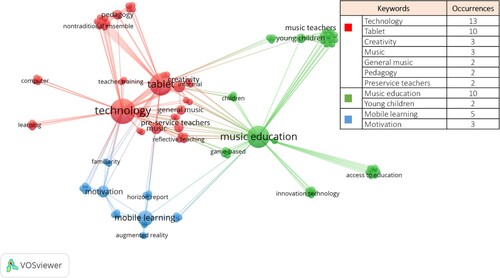

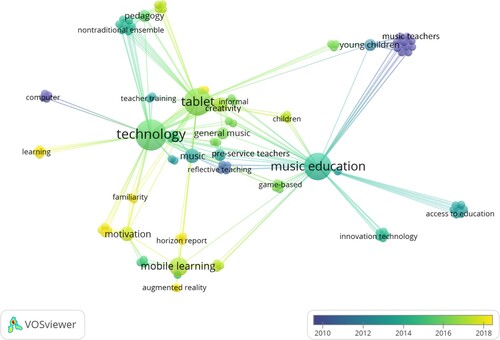

4.7. Keyword analysis

In this study, VOSviewer was adopted to perform cluster analysis of keywords. The keyword analysis was conducted in order to understand the research focuses of MTSME. There are 114 keywords in this study, and the network maps of keywords with more than two frequencies are shown in and .

Figure 12. The analysis of keyword co-occurrence on mobile learning studies in music education between 2008 and 2019.

As can be seen in , from 2008 to 2019, the research on MTSME focused on music teachers and pre-service teachers in the early years, but in recent years, the research has continued to focus on mobile learning, creativity, and motivation.

As shown in , the most used keywords are technology (f = 13), music education (f=10), tablet (f=10), mobile learning (f=5), creativity (f=3), motivation (f=3), music (f=3), general music (f=2), pedagogy (f=2), preservice teachers (f=2), and young children (f=2). It can also be seen in that from 2008 to 2019, studies on MTSME focused on three main clusters, namely technology, music education, and mobile learning.

The red cluster described the mobile technology-supported teaching management and learning design (7 top terms), including technology, tablet, creativity, music, general music, pedagogy, and preservice teachers. Among the mobile devices adopted in music courses, tablets such as the iPad were adopted the most often in music teaching and learning (Chou & Chu, Citation2017; Kang, Citation2018). Referring to research issues, previous studies on MTSME focused on general music (Chou & Chu, Citation2017), while more studies investigating other music topics, such as instrumental or vocal music, are needed. In addition, pre-service teachers emerged from the red clusters, indicating that integrating technologies into music instruction requires adequate attention to teacher perceptions and acceptance (Reese et al., Citation2016). It was also found that more than half of the music courses involved one-to-one tutoring, which implies that musicians’ or music educators’ self-rated technology skills have a direct impact on their decision regarding whether to adopt mobile learning in their courses through influencing their perceptions of the ease of use and usefulness of a certain technology (Waddell & Williamson, Citation2019). It is also worth noting that there is a growing focus on learner creativity in music education, while researchers indicated that mobile devices remain underused in music learning, especially in master-apprenticeship one-to-one music learning environments (Eyles, Citation2018). Therefore, it is worth exploring the role of technology in supporting music education and innovating pedagogy in music education.

The green cluster focused on developing appropriate music educational resources for different user groups. For example, Nardo (Citation2008) provided recommendations on use of music technologies for preschool children. Jenson et al. (Citation2016) explored how high school-aged students learning music through mobile games significantly impacted their music knowledge and skills. Burton and Pearsall (Citation2016) further found that young children preferred apps with high frequency of visual stimulation and familiar music, which could be a reference to developers aiming to design mobile apps for young children. This implies the need to implement mobile learning in music education, also considering the interests and needs of different user groups for mobile technologies, especially young children.

The blue cluster focused on mobile technology facilitated learning motivation in music education. Kang (Citation2018) indicated that the motivation related factors and technology preference significantly impact teachers and learners’ intention to adopt mobile technologies. For example, Chen (Citation2015) adopted mobile devices with an application Auralbook to assist young learners in learning aural skills, indicating that the method not only significantly improved students’ learning achievement but also positively impacted their motivation to learn music. Hanrahan et al. (Citation2019) integrated networked tablets into primary school ensemble music practicing, and found that the technology did help promote early-stage young music learners’ learning enjoyment and motivation. In addition to assisting learners in learning music through the features of mobile devices, the integration of effective learning strategies can also be considered to enhance students’ motivation and music learning effectiveness.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Based on the technology-based review model proposed by Lin and Hwang (Citation2019), this study provides a review and analysis of research related to MTSME from 2008 to 2019. The number of relevant studies was less in the earlier years from 2008 to 2013, and then there was substantial growth in the number of relevant studies on MTSME from 2014 to 2019. It can be seen that it will be promising to integrate mobile technologies into music education in the future, and the research topics on MTSME can become even more diverse. The major findings and discussions are as follows:

Research on MTSME has paid more attention to students’ music skills (see A01, A03, A05, A06, A08, A09, A11, A12, A13, A14, A15, A16, A20, A21, A22, A23, A24, A25, A26, A27, A28, A29, A20, A32 in the appendix) than to the conceptual learning of music. One possible reason for this is that music education focuses more on student skill-oriented activities in one-to-one instructional and instrumental settings. In contrast, conceptual learning has often taken place in other settings in the past (e.g. one-to-many instruction) (Waddell & Williamson, Citation2019).

With regard to the research issues of MTSME, more studies have investigated participant personal perspectives and learning experiences (see A09, A19, A21 in the appendix), or the impacting factors for their intention to adopt mobile devices (see A31 in the appendix), while fewer studies have focused on participant perceptions including learning satisfaction, self-efficacy, and anxiety. For the cognition aspect, researchers carried out more investigations of the impacts of mobile technology on students’ achievement or skill improvement in music learning by means of testing (see A2, A04, A10, A14, A25 in the appendix), while less attention has been paid to students’ higher order thinking development. As Lai (Citation2020) pointed out, when mobile technology is adopted in a new area, researchers should first explore learner and instructor using experiences and technology acceptance to prepare for future research. In contrast to the fields of science and social science, music-related courses are a new frontier in using mobile technology, and thus most of the studies to date have focused on exploring the learning experience.

It was found in the current study that most of the studies on MTSME have adopted qualitative methods by means of surveys and interviews to explore participants’ personal perspectives and learning experiences and to summarize the current status and analyze future trends for mobile learning in music education. There is huge room for growth in quantitative methods on mobile learning in music education. For instance, Zhou et al. (Citation2008) indicated that integrating mobile technology into music learning is helping to facilitate the skill-oriented learning process through touch-based interaction and enhancing the collaborative music learning experience for music learners. Compared with linguistics, mathematics, and social sciences, music is a less-discussed field for mobile learning; researchers can discuss learning experiences and feelings with mobile technology.

Inferring from the mobile devices adopted, excluding non-specific and no devices, the most adopted devices were tablets, and other mobile devices were used less frequently. This finding is consistent with previous findings from a comprehensive review of mobile technology to support physical education (Yang et al., Citation2020). Tablets offer several advantages, including high interaction, portability, and connectivity. In addition, compared to a smartphone, a tablet is equipped with a larger screen, which makes it more useful for music education. For example, Chou and Chu (Citation2017) adopted tablets as simulated musical instruments to perform repeated exercises, as a virtual music score for viewing, or as editable tools for music composition. For these contexts, larger-screen tablets are more popular for musicians and music educators.

Excluding studies of trend analysis and perspective statements, most studies on MTSME recruited higher education students. This finding is consistent with Wu et al. (Citation2012), whose study found that most of the studies in MTSME are convenient to implement in higher education. There are two possible reasons for this: firstly, most of the researchers are teaching in universities, and so it is convenient for them to collect data from students in their department; secondly, most higher education learners have their own mobile devices, which enables them to have easier access to mobile technology to support mobile learning activities.

The existing studies on MTSME are mainly perspective descriptions, trend analysis, and investigations of the perceptions and learning experiences of music educators and learners. However, they did not apply learning strategies in their learning activities. In other studies that adopted specific learning strategies, guided learning, project-based learning, inquiry-based learning, and peer assessment were commonly adopted (see A01, A02, A04, A05, A06, A07, A10, A11, A12, A14, A18, A20, A21, A22, A25, A26, A27, A29, A32 in the appendix). For conceptual learning, the most commonly adopted learning strategy is guided learning, while for skill acquisition, project-based learning was adopted the most often. The learning strategies of video sharing, computers as mindtools, and contextual mobile learning were not used in these articles. Crawford and Southcott (Citation2017) found that mobile technology is necessary for the development of music education. However, the research exploring the relationship between technology and music is minimal and vague, indicating that applying mobile technologies to music education is still in its early stages. This may be why most researchers have only tried to incorporate mobile technology into instructional activities and have not yet considered further incorporating learning strategies appropriately.

VOSviewer was used to analyze mobile learning's keyword clustering in music education, and three closely related groups were obtained. The first group is mobile technology-supported teaching management and learning design, the second group is developing appropriate music educational resources for different educational levels, and the third group is mobile technology facilitated learning motivation in music education. It can be seen that there are three primary research focuses: teachers’ experience in adopting mobile technology, discussion on appropriate use of mobile technology in music education, and future trends of mobile learning in music. In recent years, apart from exploring the application of MTSME, scholars have begun to focus on developing higher order thinking skills such as creativity. This changing trend is consistent with Lai's (Citation2020) research findings that the development of mobile learning is concerned with the improvement of learning achievement or skills and the development of higher order thinking skills such as the creativity of future learners.

However, there are some limitations of this study that should be noted. Although this study has captured relevant research on MTSME from four major databases, the final number of articles analyzed is still limited. This is most likely because music is not only about memorizing and comprehension but is also about student creativity and other advanced thinking skills. Thus, the incorporation of mobile technology into music learning is still challenging. This study is a literature review following the six dimensions of the technology-based review model, but there are still other valuable issues to be explored. Based on the major findings and limitations of this study, several recommendations for future research are made as follows.

There is great potential for applying different types of mobile technologies to music-related subjects. To expand the application domains of MTSME, it is necessary to not only investigate the musical skills but also to explore music conceptual learning. With regard to the music application domain, this area is worth investigating. In addition, it is suggested that attention be paid to different types of music learning content and that appropriate mobile learning activities are chosen.

In the field of MTSME, many researchers have focused on learning achievement or learning performance. This implies that learning behaviors, collaboration and other higher order thinking skills are seldom-discussed issues. Future studies investigating these issues would likely add value to their research.

In terms of research methods, it is recommended to conduct research on MTSME with mixed methods including a precise experimental design and more complex surveys and interviews which can investigate the effectiveness of MTSME through both quantitative and qualitative approaches.

In order to provide exciting and interactive learning environments for MTSME, it is also suggested that diverse mobile devices be introduced, such as wearable devices, AR/VR, or artificial intelligence technology to improve learning results and learning experiences.

It is also suggested that multiple learning strategies be appropriately combined in different music education units. It is possible to find suitable mobile learning modes for music education by observing and surveying learning experiences and processes.

The main purpose of the current study is to provide a comprehensive literature review on MTSME and to propose possible research topics for future research. Although previous studies have discussed the research trends of mobile learning in many domains, this study expands the application domain by reviewing studies in MTSME. The advancements of mobile technology and other technologies may promote the development of music education and bring new energy to this field. As a consequence, it is worth investigating how to come up with precise experimental designs for the future research in MTSME, how to choose appropriate learning strategies for different music learning units in mobile learning contexts, and how to facilitate the advancement of MTSME with the development of science and technology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Chenchen Liu

Dr. Chenchen Liu is an Associate Professor at the Department of Educational Technology, Wenzhou University, Chashan University Town, Wenzhou 325035, Zhejiang Province, China. Her research interests include artificial intelligence in education, digital reading and mobile learning.

Gwo-Jen Hwang

Dr. Gwo-Jen Hwang is a chair professor at the Graduate Institute of Digital Learning and Education, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology. His research interests include mobile learning, digital game-based learning, flipped classroom and AI in education.

Yun-fang Tu

Dr. Yun-fang Tu comes from Department of Library and Information Science, Research and Development Center for Physical Education, Health, and Information Technology, Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan. Her research interest includes E-library, digital learning and information literacy.

Yiqing Yin

Miss. Yiqing Yin is a Postgraduate student at the Department of Educational technology, University of Wenzhou. Her research interests include digital learning and technology education.

Youmei Wang

Dr. Youmei Wang is a professor at the Department of Educational technology, Wenzhou University. His research interests include digital learning, technology education and AI in education.

References

- Azzara, C. D. (1993). Audiation-based improvisation techniques and elementary instrumental students’ music achievement. Journal of Research in Music Education, 41(4), 328–342. https://doi.org/10.2307/3345508

- Bano, M., Zowghi, D., Kearney, M., Schuck, S., & Aubusson, P. (2018). Mobile learning for science and mathematics school education: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Computers & Education, 121, 30–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.02.006

- Birch, H. J. (2017). Potential of SoundCloud for mobile learning in music education: A pilot study. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 11(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMLO.2017.10001727

- Brownlow, A. (2017). A New Approach to Music History Pedagogy Using iPad Technology and Flipped Learning. College Music Symposium, 57. Retrieved September 6, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26574460

- Burton, S. L., & Pearsall, A. (2016). Music-based iPad app preferences of young children. Research Studies in Music Education, 38(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X16642630

- Chang, C. Y., Lai, C. L., & Hwang, G. J. (2018). Trends and research issues of mobile learning studies in nursing education: A review of academic publications from 1971 to 2016. Computers & Education, 116, 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.09.001

- Chen, C. W. J. (2015). Mobile learning: Using application Auralbook to learn aural skills. International Journal of Music Education, 33(2), 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761414533308

- Chen, C. W. J. (2020). Mobile composing: Professional practices and impact on students’ motivation in popular music. International Journal of Music Education, 38(1), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761419855820

- Chen, I. C., Hwang, G. J., Lai, C. L., & Wang, W. C. (2020). From design to reflection: Effects of peer-scoring and comments on students’ behavioral patterns and learning outcomes in musical theater performance. Computers & Education, 150, 103856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103856

- Chien, C. F., Walters, B. G., Lee, C. Y., & Liao, C. J. (2018). Developing musical creativity through activity theory in an online learning environment. International Journal of Online Pedagogy and Course Design, 8(2), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJOPCD.2018040105

- Chou, C. H., & Chu, Y. L. (2017). Interactive rhythm learning system by combining tablet computers and robots. Applied Sciences, 7(3), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/app7030258

- Crompton, H., Burke, D., Gregory, K. H., & Gräbe, C. (2016). The use of mobile learning in science: A systematic review. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 25(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-015-9597-x

- Crawford, R. (2017). Rethinking teaching and learning pedagogy for education in the twenty-first century: Blended learning in music education. Music Education Research, 19(2), 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1202223

- Crawford, R., & Southcott, J. (2017). Curriculum stasis: The disconnect between music and technology in the Australian curriculum. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 26(3), 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2016.1247747

- Crompton, H., & Burke, D. (2018). The use of mobile learning in higher education: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 123, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.04.007

- Crow, B. (2006). Musical creativity and the new technology. Music Education Research, 8(1), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613800600581659

- de Vries, P. (2013). The use of technology to facilitate music learning experiences in preschools. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(4), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911303800402

- Elaish, M. M., Shuib, L., Ghani, N. A., & Yadegaridehkordi, E. (2019). Mobile English language learning (MELL): A literature review. Educational Review, 71(2), 257–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1382445

- Eyles, A. M. (2018). Teachers’ perspectives about implementing ICT in music education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(5), 8. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n5.8

- Guillén-Gámez, F. D., Álvarez-García, F. J., & Rodríguez, I. M. (2018). Digital tablets in the music classroom: A study about the academic performance of students in the BYOD context. Journal of music. Technology & Education, 11(2), 171–182.

- Han, I., & Shin, W. S. (2016). The use of a mobile learning management system and academic achievement of online students. Computers & Education, 102, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.07.003

- Hanrahan, F., Hughes, E., Banerjee, R., Eldridge, A., & Kiefer, C. (2019). Psychological benefits of networking technologies in children’s experience of ensemble music making. International Journal of Music Education, 37(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761418796864

- He, S., Chiat, L. F., & Ying, L. F. (2015, June 10-12 ). M-learning in the transmission and sustainability of Cantonese opera in KSK Art Crew. 6th International Conference on New Horizons in Education, Barcelona, Spain.

- Hillier, A., Greher, G., Queenan, A., Marshall, S., & Kopec, J. (2016). Music, technology and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: The effectiveness of the touch screen interface. Music Education Research, 18(3), 269–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2015.1077802

- Ho, W. C. (2004). Use of information technology and music learning in the search for quality education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 35(1), 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2004.00368.x

- Hsia, L. H., & Sung, H. Y. (2020). Effects of a mobile technology-supported peer assessment approach on students’ learning motivation and perceptions in a college flipped dance class. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 14(1), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMLO.2020.103892

- Hsu, Y. C., Ho, S. N., Tsai, C. C., Hwang, G. J., Chu, H. C., & Wang, C. Y. (2012). Research trends in technology-based learning from 2000 to 2009: A content analysis of publications in selected journals. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 15(2), 354. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.15.2.354

- Hwang, G. J., & Chang, H. F. (2011). A formative assessment-based mobile learning approach to improving the learning attitudes and achievements of students. Computers & Education, 56(4), 1023–1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.12.002

- Hwang, G. J., & Chang, S. C. (2021). Facilitating knowledge construction in mobile learning contexts: A bi-directional peer-assessment approach. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(1), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13001

- Hwang, G. J., & Tsai, C. C. (2011). Research trends in mobile and ubiquitous learning: A review of publications in selected journals from 2001 to 2010. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(4), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01183.x

- Hwang, G. J., Tsai, C. C., & Yang, S. J. H. (2008). Criteria, strategies and research issues of context-aware ubiquitous learning. Educational Technology & Society, 11(2), 81–91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.11.2.81

- Jenson, J., De Castell, S., Muehrer, R., & Droumeva, M. (2016). So you think you can play: An exploratory study of music video games. Journal of Music, Technology and Education, 9(3), 273–288. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte.9.3.273_1

- Johnson, D., Damian, D., & Tzanetakis, G. (2020). Evaluating the effectiveness of mixed reality music instrument learning with the theremin. Virtual Reality, 24(2), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-019-00388-8

- Kang, S. (2018). Motivation and preference for acoustic or tablet-based musical instruments: Comparing guitars and gayageums. Journal of Research in Music Education, 66(3), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429418785379

- Kelleher, J. (2015). A framework for progression in musical learning. Music mark. https://www.musicmark.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/peer-to-peer_progression_framework.pdf

- Kim, E. (2013). Music technology-mediated teaching and learning approach for music education: A case study from an elementary school in South Korea. International Journal of Music Education, 31(4), 413–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761413493369

- Lai, C. L. (2020). Trends of mobile learning: A review of the top 100 highly cited papers. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(3), 721–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12884

- Lai, C. L., & Hwang, G. J. (2015). High school teachers’ perspectives on applying different mobile learning strategies to science courses: The national mobile learning program in Taiwan. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 9(2), 124–145. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMLO.2015.070704

- Lall, P., Rees, R., Law, G. C. Y., Dunleavy, G., Cotič, Ž, & Car, J. (2019). Influences on the implementation of mobile learning for medical and nursing education: Qualitative systematic review by the digital Health education collaboration. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(2), e12895. https://doi.org/10.2196/12895

- Lin, H. C., & Hwang, G. J. (2019). Research trends of flipped classroom studies for medical courses: A review of journal publications from 2008 to 2017 based on the technology-enhanced learning model. Interactive Learning Environments, 27(8), 1011–1027. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1467462

- Liu, M., Scordino, R., Geurtz, R., Navarrete, C., Ko, Y., & Lim, M. (2014). A look at research on mobile learning in K–12 education from 2007 to the present. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 46(4), 325–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2014.925681

- Martin, F., & Ertzberger, J. (2013). Here and now mobile learning: An experimental study on the use of mobile technology. Computers & Education, 68, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.04.021

- McMillan, J. H., & Schumacher, S. (2006). Research in education: Evidence-based inquiry. Pearson.

- Moreno, M. (2014). Soundcool: New technologies for mobile and ubiquitous learning in music education. Canadian Music Educator, 55(4), 24–28.

- Nardo, R. (2008). Music technology in the preschool? Absolutely!. General Music Today, 22(1), 38–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048371308323272

- Nart, S. (2016). Music software in the technology integrated music education. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET, 15(2), 78–84.

- Nolan, K. K. (2009). SMARTer music teaching: Interactive whiteboard use in music classrooms. General Music Today, 22(2), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048371308324104

- Order, S. (2015). ‘ICreate’: Preliminary usability testing of apps for the music technology classroom. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 12(4). https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol12/iss4/8

- Palazón, J., & Giráldez, A. (2018). QR codes for instrumental performance in the music classroom. International Journal of Music Education, 36(3), 447–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761418771992

- Paule-Ruiz, M., Álvarez-García, V., Pérez-Pérez, J. R., Álvarez-Sierra, M., & Trespalacios-Menéndez, F. (2017). Music learning in preschool with mobile devices. Behaviour & Information Technology, 36(1), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2016.1198421

- Riley, P. (2013). Teaching, learning, and living with iPads. Music Educators Journal, 100(1), 81–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432113489152

- Riley, P. (2016). iPad apps for creating in your general music classroom. General Music Today, 29(2), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048371315594408

- Riley, P. E. (2018). Music composition for iPad performance: Examining perspectives. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 11(2), 183–195. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte.11.2.183_1

- Reese, J. A., Bicheler, R., & Robinson, C. (2016). Field experiences using iPads: Impact of experience on preservice teachers’ beliefs. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 26(1), 96–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057083715616441

- Reeves, T., Caglayan, E., & Torr, R. (2017). Don’t shoot! understanding students’ experiences of video-based learning and assessment in the arts. Video Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 2(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40990-016-0011-2

- Reid, A. G., Rakhilin, M., Patel, A. D., Urry, H. L., & Thomas, A. K. (2017). New technology for studying the impact of regular singing and song learning on cognitive function in older adults: A feasibility study. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 27(2), 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/pmu0000179

- Savage, J. (2007). Reconstructing music education through ICT. Research in Education, 78(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.7227/RIE.78.6

- Tan, Y., & Conti, L. (2019). Effects of Chinese popular music familiarity on preference for traditional Chinese music: Research and applications. Journal of Popular Music Education, 3(2), 329–358. https://doi.org/10.1386/jpme.3.2.329_1

- Terras, M. M., & Ramsay, J. (2012). The five central psychological challenges facing effective mobile learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 820–832. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01362.x

- Tu, Y. F., & Hwang, G. J. (2020). Transformation of educational roles of library-supported mobile learning: A literature review from 2009 to 2018. The Electronic Library, 38(4), 695–710. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-10-2019-0230

- Upitis, R. (2013). Enriching the time between music lessons with a digital learning portfolio. Canadian Music Educator, 54(4), 22–28.

- Verrico, K., & Reese, J. (2016). University musicians’ experiences in an iPad ensemble: A phenomenological case study. Journal of Music, Technology & Education, 9(3), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1386/jmte.9.3.315_1

- Vratulis, V. (2011). A case study exploring the use of GarageBand™ and an electronic bulletin board in pre-service music education. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 11(4), 398–419. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/36053/

- Waddell, G., & Williamson, A. (2019). Technology use and attitudes in music learning. Frontiers in ICT, 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fict.2019.00011

- Wang, M., Shen, R., Novak, D., & Pan, X. (2009). The impact of mobile learning on students’ learning behaviours and performance: Report from a large blended classroom. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(4), 673–695. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00846.x

- Webster, P. R. (2007). Computer-based technology and music teaching and learning: 2000–2005. In International handbook of research in arts education (pp. 1311–1330). Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-3052-9_90

- Williams, D. A. (2014). Another perspective: The iPad is a REAL musical instrument. Music Educators Journal, 101(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432114540476

- Wu, W. H., Wu, Y. C. J., Chen, C. Y., Kao, H. Y., Lin, C. H., & Huang, S. H. (2012). Review of trends from mobile learning studies: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 59(2), 817–827. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.03.016

- Yang, Q. F., Hwang, G. J., & Sung, H. Y. (2020). Trends and research issues of mobile learning studies in physical education: A review of academic journal publications. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(4), 419–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2018.1533478

- Zhou, F., Duh, H. B. L., & Billinghurst, M. (2008, September 15–18). Trends in augmented reality tracking, interaction and display: A review of ten years of ISMAR. In 2008 7th IEEE/ACM International symposium on mixed and augmented reality (pp. 193-202). IEEE.

- Zydney, J. M., & Warner, Z. (2016). Mobile apps for science learning: Review of research. Computers & Education, 94, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.001