ABSTRACT

Many studies have addressed the issue of the relationship between digital games and aggressive behaviour. However, less attention has been paid to the stereotyping of digital games and overcoming stereotypes from gamers’ perspective. This paper presents research conducted using the classic version of Grounded Theory. The research problem, i.e. the main concern of digital game players – the stereotyping of digital games – and the processes of addressing this problem emerged during the coding and analysis of the research data. The study has revealed how digital game players reinterpret the characteristic of digital games that “digital games encourage aggressive behaviour”. A whole range of reinterpretations emerged: Handling of virtual material rather than aggressive actions; Open in-game actions visible to everyone rather than aggressive actions; Digital games do not encourage aggressive behaviour, aggressive behaviour is in human nature; A space to sublimate masculine powers rather than aggressive actions; Social experimentation rather than aggressive actions; Exploration of limit states rather than aggressive actions; Emotional training rather than aggressive actions. This paper investigates the features and the course of reinterpretation processes as well as the aspiration of the gamers to disrupt negative stereotypes that hinder successful game-based learning.

1. Introduction

The rapid development of digital technologies (mobile technology, maker technology, analytics technology, simulation technology, artificial intelligence (AI), games), the variety of genres and content of digital games, and the possibility to connect to online games and play with others in real time have encouraged people to play digital games. According to SELL (Citation2022), in France alone, 53% of the population (37.4 million) – young people, seniors, children, and their parents – played digital games regularly in 2022, of which 51% were men and 49% were women. Statistical data show that in the third quarter of 2023, it was shooter and action-adventure games that were the two most popular video game genres worldwide. Shooter games were the most popular game genre in almost all age groups (Statista, Citation2024).

According to Bonnaire and Conan (Citation2024), in recent years, digital games have become a leading cultural sector, with the emergence of communities of people who consider themselves “gamers”. Gamers share their gaming habits, have a common (sub)culture, favourite games, and a common identity created in the gaming space (Nauroth et al., Citation2014). Digital games are also being integrated into the field of education, with the emergence of game-based learning (GBL), in which digital didactics is being developed as an approach that combines digital technologies, pedagogy, and game thinking (Dahalan et al., Citation2024; Kiili et al., Citation2023). The aim of this strategy is to facilitate learning and teaching by creating an atmosphere of fun and providing an environment of self-directed, challenge-based, and creative learning.

The scale of digital gaming and its integration into education is fuelling debate about the impact of gaming, particularly playing violent games, on the health of gamers, especially young gamers. Concerns have been raised about the potential risk that certain genres of games (shooting, fighting, role-playing games, battle royale games, racing games) and the violent content of games may lead to aggressive behaviour (Adachi & Willoughby, Citation2016; Hawk & Ridge, Citation2021). The public debate in society and at school about the potential harms of digital games has led to a trend towards negative stereotyping of digital games as a phenomenon and of gamers.

This paper presents a study based on Grounded Theory methodology, which identified the stereotyping of digital games as a key concern for gamers and revealed how gamers address this concern by reinterpreting the stereotyped negative characteristic of the game, i.e. that it encourages aggressive behaviour.

1.1. Literature review

Salen and Zimmerman (Citation2004) define a digital game as a system in which gamers engage in a constructed, artificial conflict, defined by rules, where the outcome is enjoying and a quantifiable result. In the broadest sense, a digital game is a hybrid environment or medium that combines different technologies using different electronic devices (Belda-Medina & Calvo-Ferrer, Citation2022; Kücklich, Citation2006).

Playing digital games as a form of leisure activity comprises a large part of people’s cultural life. Gamers form communities of “gamers” and maintain relationships with each other (Bonnaire & Conan, Citation2024). Gamers are free to choose the genre and content of the games they play: sports, simulation, adventure, shooter, etc. This raises concerns among teachers, the public, and researchers about the impact of gaming on health, in particular the effect of playing violent video games on aggressive behaviour.

Digital games are nowadays being integrated into the field of education through the development of the GBL area. GBL is about learning by playing in an atmosphere of challenge and fun and achieving learning outcomes. The aim of GBL is to motivate and encourage individuals to engage in learning and increase its effectiveness (Belda-Medina & Calvo-Ferrer, Citation2022; Gee, Citation2003; Plass et al., Citation2015; Prensky, Citation2001; Xie et al., Citation2021). GBL has evolved as a model of an experiential learning environment, characterised by socio-cultural interactions and collaboration between learners, and as an effective teaching technique (Kirstavridou et al., Citation2020; Plass et al., Citation2015). Although it is very important to properly integrate games into the learning process when applying GBL (Belda-Medina & Calvo-Ferrer, Citation2022; Dahalan et al., Citation2024), some teachers are hindered in doing so by their own and the students’ parents’ negative attitudes towards the educational value of digital games and by concerns that the appeal of digital games to students might lead to addictive gaming and aggressive behaviour in students (Chen et al., Citation2020; Kirstavridou et al., Citation2020; Voulgari & Lavidas, Citation2020; Xie et al., Citation2021).

There is a large body of research analysing the impact of digital games, in particular violent video games, on gamers. The aim of these studies is not only to establish a relationship between the playing of digital games and aggressive behaviour, but also to shed light on the mechanisms underlying the impact of digital games. According to Greitemeyer (Citation2022), some researchers support the catharsis hypothesis, which suggests that playing violent games allows gamers to let off steam and purge aggressive impulses and reveal a link between aggressive gaming and reduced violence and crime (Beerthuizen et al., Citation2017), or argue that gamers differentiate between the virtual world and the real world, and therefore only engage in aggressive acts while playing and not in the real world. The impact of violent digital games on the development of aggressive behaviour in gamers has been dismissed. Other studies draw on social learning theories and argue that aggressive actions in games are rewarded by winning, become a habit, and are transferred to reality (Bonnaire & Conan, Citation2024), and reveal that playing violent video games reduces prosocial behaviour (Coyne et al., Citation2023), thus confirming the impact of violent games on the emergence of aggressive behaviour in gamers.

Another line of research that substantiates the impact of digital games on gamers’ aggressive behaviour is research on competitive video game play. A longitudinal study by Adachi and Willoughby (Citation2016) found long-lasting bidirectional associations between competitive video game play and aggressive behaviour. The authors found that the competitive video game play factor was a significant longitudinal predictor of aggression. The goal of competitive games is always to win the competition, either violent or non-violent, against a real person or imaginary (computer-generated) opponent, which hinders the achievement of the goal and thus provokes aggressive behaviour. A follow-up study by Hawk and Ridge (Citation2021) confirmed that competition in video games has an independent and significant effect on subsequent aggression, while violent content of the game and the level of difficulty of the game do not have a significant effect on gamers’ aggression. The study by Kahila et al. (Citation2022) also found that adolescents’ irritation when playing digital games was not caused by the violent content of the game, but by their reactions to the game with opponents (e.g. when they lost, when others succeeded and they did not), and in the same study, the level of difficulty of the game was also found to be a cause of adolescents’ frustration and aggressive reactions to the game.

Researchers have also attributed the aggressive behaviour in gamers after playing violent video games to another mechanism – the desensitising effect of violent images on adolescents. Following the Media Violence Desensitisation Model (Carnagey et al., Citation2007), viewing violent images while playing digital games can reduce neural activity and thus sensitivity to the pain of others, which in turn can increase antisociality and reduce prosocial behaviour. Miedzobrodzka et al. (Citation2021) sought to determine the short-term effects of violent video games on adolescents’ emotion recognition and inhibitory control. The research results show that recognising the emotions of a distressed victim can act as a “violence inhibition mechanism”, promoting empathy and reducing the likelihood of violent behaviour, and that less accurate emotion recognition is associated with anti-social content in various media, but not with playing traditional violent video games. Another study by Miedzobrodzka et al. (Citation2023), aiming to validate the Media Violence Desensitisation Model, found only a partial desensitisation effect of violent video games on adolescents.

It is also possible that personality factors that favour aggressiveness may predispose some individuals to enjoy and play violent video games (Groves & Anderson, Citation2017). The research by Bonnaire and Conan (Citation2024, p. 88) revealed a profile of gamers with a preference for violent video games, called “emotionally controlled” gamers. These are usually men who seek high sensations, adventure, danger, and risk, and who are deeply emotionally involved in the game; they have a low affect intensity and a good level of acceptance of their negative emotions. As violent games are characterised by failure and frustration, in order to succeed, gamers need to maintain emotional stability and regulate negative emotions, i.e. stay calm under negative pressure. Thus, these gamers are not, as they are stereotypically described, emotionally unstable, with low-stress tolerance or aggressive, but they have positive qualities such as strong self-regulation.

Coyne et al. (Citation2023) sought to identify risk factors for aggressive behaviour. The researchers examined for whom and under what circumstances playing violent video games would be associated with an increase in aggressive behaviour and for whom and under what circumstances it would not. The authors highlighted multi-risk adolescents whose families have lower incomes, who have difficult relationships with their mothers, and who are exposed to bullying and tensions in their families. Playing violent video games does not increase their aggressive behaviour, as real-life factors in the social environment are more consequential. Gamers belonging to the High Gaming, High Aggression group are more likely than others to exhibit aggressive behaviour when playing violent video games, to have psychological problems, and to use video games to cope with depression or stress. For the Moderate Risk group, playing violent video games does not pose an additional risk, as other environmental factors (parental control and discussions about the content of games) reduce the risk. Gamers belonging to the Low Risk, High Privilege group have enough protective factors in their environment to ensure that playing violent video games does not put them at any additional risk of reinforcing their aggressive behaviour.

The impact of prosocial video games on gamers has also been studied. Prosocial video games have been found to have a positive effect on gamers’ prosocial behaviour and to reduce aggressive behaviour. A positive impact is achieved through cooperative and collaborative games (Greitemeyer, Citation2022).

Ferguson and Wang (Citation2019) argue that, in some cases, the evidence on the relationship between digital games featuring aggressive content and violent behaviour is collected using inappropriate methods, and that there is a body of research that casts doubt on the relationship between digital gaming and aggression; therefore, games with violent content are unjustifiably treated as a risk factor.

Thus, there is still an ongoing debate about the impact of violent video games. In the context of this discussion, the problem of stereotyping of digital games and gamers emerges.

According to Kowert et al. (Citation2014), as recently as a decade ago, digital game players were stereotyped as unpopular, idle, overweight, and socially isolated. These characteristics were attributed to the community of digital game players as a whole. Nauroth et al. (Citation2014) note that the community of digital game players is publicly stigmatised every time the playing of digital games is associated with real-life outbreaks of violence in the public discourse. According to Ferguson (Citation2008), news articles tend to be quick to draw a link between violent mass shootings and the gaming habits of the perpetrator, but research studies (after reviewing for bias issues) have not confirmed the hypothesis that violent video games are associated with higher levels of aggression. Research suggests that aggressive human behaviour (school shootings) is linked to playing digital games if the person who is aggressive is a representative of the white race, and that aggressive behaviour is linked to race if the person who behaves aggressively is a black person (Markey et al., Citation2020).

According to Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer (Citation2022), even today, when the Covid-19 pandemic has fundamentally transformed attitudes towards the use of digital technologies, a part of the public has a stereotyped view of the low value of digital games for learning. As noted by Bonnaire and Conan (Citation2024), digital game players are still stereotyped as emotionally unstable with low-stress tolerance.

The developed differential susceptibility to media effects model (DSMM) sets the stage for the stereotyping of digital games as a medium. The model explains that individuals have different levels of susceptibility to media effects and that some individuals are more affected by media than others (Piotrowski & Valkenburg, Citation2015). This model emphasises the interaction between people and media: people choose certain media to meet their needs, and media can influence people’s behaviour through interaction. However, the study by Cudo et al. (Citation2023) did not confirm that game genre and other characteristics have an impact on the development of the game disorder, but rather that the personal characteristics of gamers, such as impulsive behaviour, lack of self-control, etc., play a greater role.

Digital gaming communities tend to oppose the stereotyping of gamers and games as a medium. Nauroth et al. (Citation2014) point out that players of violent video games who enjoy and play them willingly tend to underestimate the research-based arguments about the harm caused by these games. These processes are reinforced by the fact that digital game players identify themselves with a social group of gamers. Empirical research explaining the harmful effects of violent video games threatens the positive social identity of gamers. For gamers, this means stigmatising their group and undermining the relevance of scientific arguments.

Within the range of research on the relationship between digital game playing and aggressive behaviour, studies that reveal the position of digital game players themselves on the ability of digital games to encourage aggressive behaviour remain relevant. The aim of this paper is to reveal how digital game players try to overcome the stereotype that playing digital games encourages aggressive behaviour.

2. Research methodology

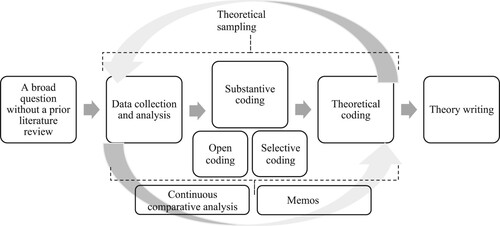

The classic version of Grounded Theory (GT) was used to analyse the research problem. At the heart of GT is the emergence of a theory from empirical data, allowing the study of a little-discovered phenomenon without preconceptions or hypotheses. This paper does not present the whole developed theory, but only a part of it, revealing the processes of reinterpretation of one stereotyped characteristic of digital games (digital games encourage aggressive behaviour) (see ).

The research followed all the steps and methodological principles of classic GT.

2.1. Research question

According to the methodology of classic Grounded Theory, the traditional research question is not formulated with the aim of exploring openly without preconception. Classic GT prioritises emergence versus preconception (Holton & Walsh, Citation2017). The research field was therefore approached with a broad (interview) question, without prior literature analysis (see ). In the first interviews, the participants were asked a broad question: how one can learn visual arts by playing digital games. This question was asked because the original idea of the research was to find out how visual arts are learned by playing digital games. However, once the research began, it became clear that gamers were not highlighting the educational aspects of digital games for visual arts learning, but rather the negative evaluation of digital games, i.e. the stereotyping of digital games. The emergence of an unexpected concern, even one that comes from a different domain, is typical of classic GT (Glaser, Citation1978; Holton, Citation2009).

In further interviews, after the main concern had already emerged and the core category was obviously starting to take shape, more specific questions were asked (e.g.: How do you deal with negative comments about your gaming? Could you please specify what you meant by saying; and so on.). The participants of the interviews were each individually asked these more specific questions as a response to the progress and contents of the conversation in order to fully saturate the already emergent and still emerging categories and to reveal their characteristics and processes.

2.2. Data coding and analysis

The research problem, i.e. the main concern and problem-solving processes, emerged in data coding and analysis (Glaser, Citation1978, Citation2018). The study included the following stages: substantive coding and theoretical coding. Substantive coding consisted of open coding, in which all data were coded, and the codes were compared with each other (Glaser, Citation1978), and selective coding, which focused on the substantive category and its associated variables (Holton & Walsh, Citation2017). Other GT features were also applied in the research: memos (theoretical notes on the data) were written regularly; theoretical sampling was applied (Glaser, Citation1978).

Coding of the data did not begin until the first data were available; in our study, after the first interviews. In open coding, data were coded line by line and given “labels” of one or two keywords. For example, a different meaning of the game, a different meaning, a change in a feature, an interpretation, and later in the course of the research, the episodes of the data that were labelled with these codes were given a more accurate code that illustrated the processes taking place in the data in a more precise way – the reinterpretation. All the codes that emerged were compared with each other. The codes that emerged from the new survey data were compared with those already available. The coding was based on several questions recommended by Glaser (Citation1978, Citation2004), which helped to identify certain patterns prevalent in the incidents by conceptually naming them rather than describing them: What do these data mean? What is really happening in the data? What category does this incident refer to? What is the main concern of the research participants? How do they address it? The codes were not grouped into categories until a sufficient number of codes had emerged. Once a large number of codes were available, the validity of each code was checked by means of a continuous comparison, i.e. a constant consideration of whether the code that had emerged (e.g. reinterpretation) was the most appropriate and the best representation of the data it represents. The coding process was constantly interrupted by the writing of memos and analysing how the resulting codes related to each other, what the data said, and so on. During the coding phase, different types of reinterpretations began to emerge and develop: reinterpretation that takes place in the context of the characteristics of the digital game, reinterpretation that takes place in the context of the interaction between the digital game and the human being, and reinterpretation that is all about making the digital game a phenomenon that has positive meanings and consequences for the player. Processes and stages of reinterpretation emerged and unfolded.

In the substantive coding phase, the stereotyping of digital games emerged as a key concern, and the inherent desire of gamers to refute negative stereotypes about digital games emerged as a response to the attitudes of non-gamers. This paper presents one way of overcoming stereotypes, i.e. reinterpreting negatively perceived characteristics of digital games. The reinterpretation processes that emerged were part of the core category and were not excluded during the selective coding.

In line with Glaser (Citation1978), Holton and Walsh (Citation2017), part of the theory presented in this paper was finalised at the theoretical coding stage. The theoretical codes were conceptually defined, the links between the categories that emerged were identified, and the relationships between the codes were established.

Other elements of the GT were also implemented in the process of research, such as the continuous writing of memos (theoretical notes on the data) and theoretical sampling of the data.

2.3. Selection of research participants based on theoretical sampling

The selection of the research participants and the selection of the other data in the research were determined by theoretical sampling that was applied (Glaser, Citation1978; Holton & Walsh, Citation2017). The research data was collected from different gamers until a theory emerged, was saturated, and formulated. To develop the emerging theory, the data were continuously compared, collected, coded, and analysed in order to decide from which gamers and what data to collect next.

The initial selection of the research participants was based on the chosen field of research – learning visual arts by playing digital games. For this reason, the first participants in the research were digital game players who:

– often (according to them) played digital games;

– attended art schools and art classes; and whose study programmes were related to visual arts;

– the specific games played by the gamers were irrelevant to allow them to emerge naturally, without being forced out of the data; in the course of the research, it became clear that the genre or type of games was not relevant to the emerging theory.

The interviews were conducted with 5 adolescents (14–16 years old) who study at school and attend art schools and classes. Later, 13 young people (aged 17–25) who study or studied visual arts or other study fields and who play digital games were included in the research. The process of involving young people and three mature (26–36 years old) research participants, most of whose professional activities were related to digital games, was based on a snowball sampling approach, where the participants themselves suggested other research participants. One focus group discussion was also organised with 12 eight graders (14–16 years old) who play digital games. The wide age range of the research participants was determined by the same concern of negative stereotyping of digital games highlighted by participants of different ages and by analogous codes unrelated to the age of the participants that emerged from the research data. According to Glaser (Citation2002), characteristics such as age, gender, marital status, etc. are only analysed if they are relevant to the emerging conceptual theory (Glaser, Citation2002). These characteristics are not significant in the emerging theory part presented in this paper and are therefore not elaborated in the methodology.

2.4. Interview

The primary source of the data for this research was interviews. The interviews followed the classic GT guidelines for interviews, i.e. a free-form interview, which can be defined as a relaxed conversation between equal participants, was used (Scott, Citation2012). In line with Scott (Citation2012), during the interviews, the aim was to create an environment in which the research participants felt able to talk about what was most important to them. The interviews with all the research participants started with general questions: How are you today? or What’s up? How have you arrived? etc. The general questions were followed by a broad question: How can one learn visual arts by playing digital games? The aim of the interviews was to listen and understand what the research participants themselves considered to be the main concern and how they were dealing with it, while observing where the research data would lead. This was about understanding what was really happening, rather than filtering data on the basis of preconceptions or hypotheses.

The number of interviews, drawing on Holton and Walsh (Citation2017), was not conditioned by any specifically defined sample but by the emerging theory, its richness, meaningfulness, and saturation. The data presented in this paper emerged from 21 in-depth interviews with digital game players. The position characteristic of classic GT, that everything is data (Glaser, Citation1998, Citation2001), was followed; therefore, to refine and supplement the emerging concepts, a focus group discussion was organised with 8th grade secondary school pupils, and informal correspondence with adult interview participants was conducted.

2.5. Conceptualisation

According to Glaser (Citation2016), the aim of GT is to provide a theory that conceptually explains the concern raised and the prevailing patterns of behaviour. Specific data are neglected once a grounded theory has emerged. In this paper, it was decided to leave some data episodes that illustrate some of the processes that emerged, as they allow a better understanding of the concepts that emerged. To comply with the methodological principles, the specific research participants are not specified in the paper alongside the illustrative data episodes. This is because GT is about the patterns of behaviour that people engage in, but it is not about people themselves. It is not people who are categorised, it is their behaviour that is categorised. Concepts are dissociated from a particular person, from time, and are therefore more durable (Glaser, Citation2002).

The emerging theory was assessed using the reliability criteria of GT. The criteria of fit and validity were implemented in the study by ensuring the fit of the emerging categories and the concordance of the data, when the concepts revealed the pattern embedded in the data correctly and conceptually, without relying on predefined categories (Glaser, Citation1978; Holton & Walsh, Citation2017). The criterion of workability, or work, was achieved by revealing how the emergent concepts and their relationships explain the resolution of the main concern of the study participants (Glaser, Citation1998; Holton & Walsh, Citation2017). The criterion of relevance was implemented by revealing the processes happening in the field of study that were important to the participants of the substantive field, rather than the questions that the researcher is interested in (Holton & Walsh, Citation2017). The criterion of modifiability has been implemented by constantly modifying the theory as soon as new data emerged (Holton & Walsh, Citation2017), and the author adheres to the principle that the reinterpretation processes of a single stereotyped characteristic of digital games (digital games encourage aggressive behaviour) described in this paper can be modified and supplemented if new data becomes available.

Research ethics was followed: all participants were informed about the purpose for which their data were collected and their right to withdraw from the study at any stage. The parents of minors were informed in writing about the study's purpose and their written consents allowing their children to participate were obtained. All identifying personal information of participants was changed. All participants took part voluntarily and gave their consents.

3. Results

The study revealed that the main concern of gamers was the stereotyping of digital games that they see as an obstacle to successful GBL. To solve it, gamers reinterpret certain characteristics of games associated with negative stereotypes in order to disassociate games from the stereotype, to disrupt the stereotype or its preconditions and to emphasise the positive meaning of games to the player.

Reinterpretation of digital game characteristics consists of processes that reconsider certain game characteristics and give them different meanings unrelated to negative stereotypes. Different reinterpretation processes emerged from the study data with different types, stages and courses of action. Three types were identified:

– Type I reinterpretation process takes place in the context of digital game characteristics

– Type II reinterpretation process is related to the interaction between digital games and human beings

– Type III reinterpretation process concentrates on identifying digital games as a phenomenon with positive meaning and consequences for the gamer.

3.1. Type I reinterpretation process

This process takes place in the context of digital game characteristics as a response to certain stereotypes. Its consequence is the disruption of certain stereotypes by reinterpreting characteristics associated with negative stereotypes and thus disassociating digital games from such stereotype.

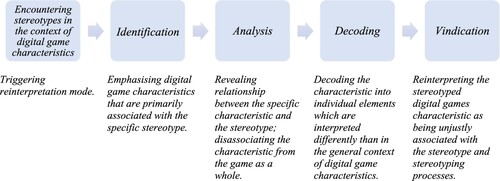

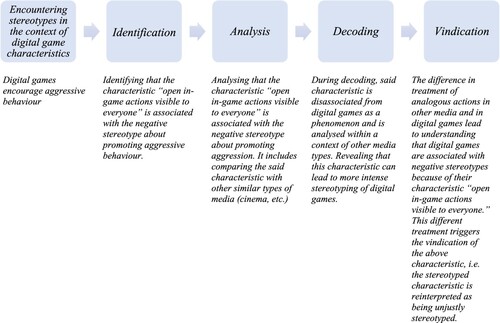

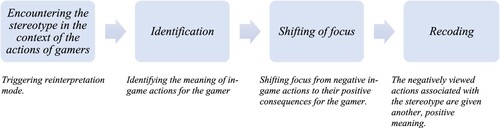

This type of reinterpretation process consists of several mostly consecutive phases: Identification, Analysis, Decoding and Vindication of the characteristic associated with a certain stereotype (see ). All phases can happen in succession, first by identifying the characteristics primarily associated with the stereotype, by analysing their relationship with stereotyping, by decoding the characteristics into individual elements and by vindicating, i.e. disassociating them from the negative stereotype.

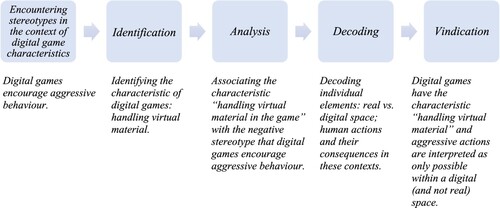

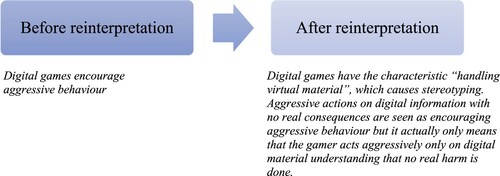

3.1.1. Handling of virtual material rather than aggressive actions

To disassociate digital games from negative stereotypes (digital games encourage aggressive behaviour), the stereotyped characteristic is reinterpreted as only taking place in virtual contexts and having no real consequences: handling of virtual material rather than aggressive actions.

In digital games you act freely because you are handling digital information in a virtual reality and not real objects. From the side, such actions are often understood as aggressive because they can have aggressive attributes. Such as:

… I would play this game where you drive a car and hit zombies and from time to time a cow would appear, and my mum walks in and I hit that cow. I was showing her how well I could drive and, like, this cow was all that stuck in her head. And I said, why are you so upset, it’s just some digital information, I mean, I’m not doing anything, it’s just some non-living thing, I couldn’t do it in real life.

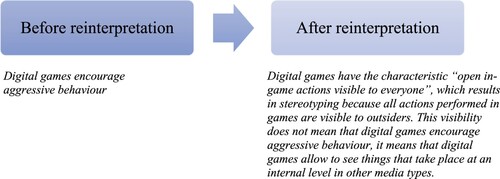

The reinterpretation of this characteristic includes identification that the game works with virtual material and analysis that it may be associated with a negative stereotype that digital games encourage aggressive behaviour (see and ). It decodes that the gamer acts freely and aggressively in the game only because he knows he is working with virtual, digital information, i.e. aggressive actions are disassociated from the game as such. Here aggressive in-game actions (hitting cow) are separated from real actions (it’s non-living thing, I couldn’t do it in real life) and are associated with actions strictly within a digital context. The gamer understands what material he is handling and knows that he cannot harm anybody or have any real consequences. Such decoding allows the vindication of digital games as a space that only handles virtual material and digital information rather than a space for aggressive actions.

3.1.2. Open in-game actions visible to everyone rather than aggressive actions

To disassociate digital games from negative stereotypes (digital games encourage aggressive behaviour), the stereotyped characteristic is reinterpreted by comparing it to other types of media and emphasising the visibility of in-game actions to bystanders which makes digital games more susceptible to stereotyping.

All in-game processes and activities are open and visible not only to participants but also to outsiders and, therefore, act as an element activating stereotypes:

It’s easy to disapprove of games because you can see if the gamer, your child, is playing something, you can see that he is shooting, so you can see what is going on on the screen. When you are showing a film … I am only an observer. I can see that this interaction is taking place but it is happening at an internal level, it does not extend to the outside …

The reinterpretation of this emerging characteristic of digital games “open and visible actions in a game” analyses it by comparing it with another similar type of media such as cinema or books. The analysis states that when you are watching a film or reading a book, you can identify yourself with negative characters but this identification is not visible to other persons although it may inspire aggressive thoughts or even actions, e.g.: “ … I had read ‘Robinson Crusoe’ and I hunted painfully stinging insects. I used to kill these insects and arrange their dead bodies on stones. … because Robinson used to arrange crows on dry sticks in the same way.” (see and ). It is decoded that both the content and all actions of the gamer are visible during gaming and, therefore, games are stereotyped more easily as promoting aggression. Here, this characteristic is disassociated from digital games as a phenomenon and is being analysed and decoded by comparing it with similar characteristics of other media types. In conclusion, the characteristic “open and visible in-game actions” can lead to stereotyping digital games more intensely than other media featuring similar content. This triggers the vindication, i.e. the characteristic associated with the stereotyping is reinterpreted as being unjustly stereotyped. The consequence of reinterpretation: the stereotype that digital games encourage aggressive behaviour is replaced with the concept that digital games have the characteristic “open and visible in-game actions” making them susceptible to stereotyping.

3.2. Type II reinterpretation process

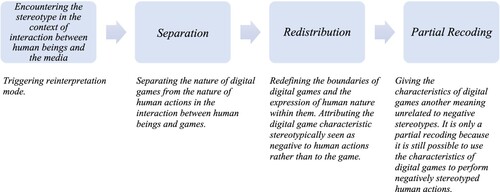

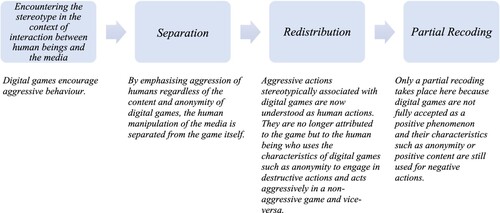

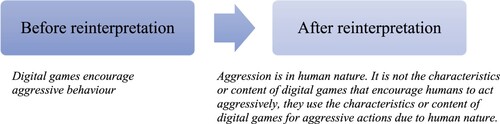

Type II reinterpretation of digital game characteristics relates to interaction between digital games and human beings. This interaction facilitates negative stereotypes about digital games as encouraging aggression (they shoot in a game, they will shoot in reality). The reinterpretation of this interaction creates preconditions for disrupting this negative stereotype. The first phase of this reinterpreting type disrupts the interaction between human beings and games, i.e. separates the actions of gamers from the nature of the game. The second phase redefines boundaries between digital games and human actions, i.e. redistributes them. This is followed by the partial recoding phase when the initially negative meaning of digital games is changed (see ).

3.2.1. Digital games do not encourage aggressive behaviour, aggressive behaviour is in human nature

When disassociating digital games from negative stereotypes and reconsidering interactions between humans and media, natural human tendency to act aggressively is emphasised.

Like many other types of modern media or social networks, digital games offer their user the anonymity option. The human use of anonymity in games often manifests as a destructive or aggressive behaviour:

The majority of games let the children stay anonymous … so people act like two dogs separated by a fence. They quarrel and bark at each other as much as they can but if the gate is opened, then both of them go away. When it is a live contact, they are scared … because then they already know that there will be some consequence.

Negative stereotypes about digital games often arise from the interpretation of the nature of human actions (such as aggressive behaviour) that use certain characteristics of digital games (e.g. anonymity) as belonging to the game rather than the human: they are not saying that a person behaves improperly, or that a human nature is aggressive, they say that games encourage aggressive behaviour. The human use of the anonymity to perform negative, destructive actions changes the interpretation of digital game characteristics creating the threatening image of digital games and encouraging negative stereotypes.

Aggressive human actions during gaming are often associated with the content of digital games: the content is aggressive, therefore, the human is playing aggressively. However, aggressive in-game behaviour (to kill a Sim, so that the person drowns) also takes place in games where the content is not related to aggression in any way. It is human nature to perform aggressive in-game actions; the games do not force people to act aggressively. Such as:

GTA 5 … The game does not restrict you in any way, you can do what you want. You can go to the city and if a hooker is standing on the street you can stop, take her into your car and drive her around. … You can attack, stab or shoot any passer-by, any person … but the game is not telling you to do that. … I, for example, played it with my kids during Christmas. … We did not go and did not beat anybody, did not fight with anyone, did not provoke anybody. … We went to clothing shops … We went to the beach and took a water motorcycle and went and did some tricks.

Thus, this type of reinterpretation process related to the interaction between humans and the media emphasise the peculiarities of human behaviour in games that have different characteristics (featuring or not featuring aggressive content) and offer an anonymity option. This emphasis helps to separate the boundaries of the human being and the digital game and to separate the human manipulation of the game characteristics and content from the game itself (see and ). Undesirable human behaviour in other types of media that share the same characteristic (anonymity) helps to separate the expression of destructive human behaviour from the digital game because similar negative behaviours can be seen on social platforms. The redistribution phase associates undesirable or destructive behaviour with human actions rather than with a specific media type. Human actions in games with aggressive or non-aggressive content emphasise that aggressive behaviour is caused by human nature and is not enforced by the content of digital games. Only a partial recoding of the stereotyped digital games takes place here because they are not fully redeemed as a positive phenomenon: because of the human nature, such characteristics of digital games as anonymity or non-aggressive content can be still used by humans to perform aggressive actions. The consequence of reinterpretation: the stereotype that digital games encourage aggressive behaviour is replaced with a concept that it is human nature to act aggressively.

3.3. Type III reinterpretation process

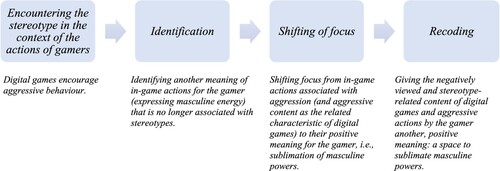

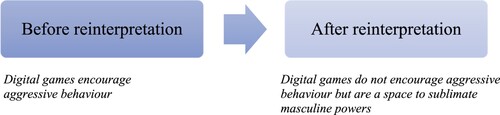

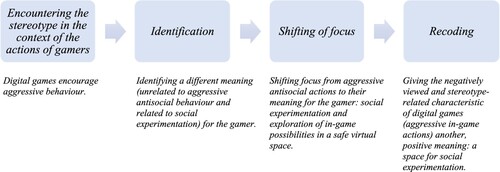

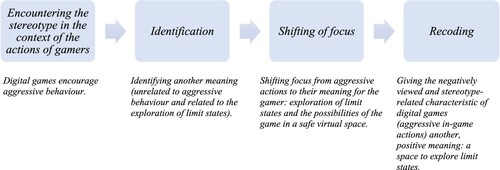

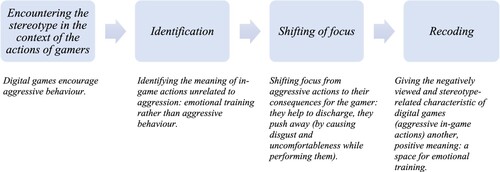

Type III reinterpretation processes identify digital games as a phenomenon that has positive meaning and consequences for the gamer. By emphasising the positive impact and possibilities offered by digital games, these processes try to influence or change related negative stereotypes. These processes are based on the reinterpretation of the meaning of in-game actions. There are three phases: first, the identification of the meaning of in-game actions for the gamer, then the shift of focus from negative actions associated with aggressive behaviour to their positive meaning for the gamer and, finally, recoding when the stereotyped property of digital games is given another, stereotype-unrelated meaning (i.e. positive meaning/positive consequence for the gamer) (see ).

3.3.1. A space to sublimate masculine powers rather than aggressive actions

Study data have revealed that some in-game actions that may be viewed as aggression are, in fact, associated and identified with “masculine behaviour” or “masculine powers” by the gamers themselves, i.e. they are exclusively attributed to the male gender.

… Certain aspects of male energy are suppressed and perhaps some aggressive video games can somehow sublimate it, can help boys to express it, especially those who are not really into moving a lot and they don’t really understand these emotions and these impulses.

Reinterpretation process identifies a different meaning of seemingly aggressive in-game actions for the gamer that is not related to their negative aspects (see and ). By shifting the focus from these actions to their positive consequences for the gamer, i.e. the sublimation of male energy for those unable to express it otherwise, the initial stereotype-related meaning of games is recoded from a negative to a positive one. Digital games are reinterpreted as a space allowing to sublimate the impulses of male nature, i.e. masculine powers, instead of a space intended for aggressive behaviour.

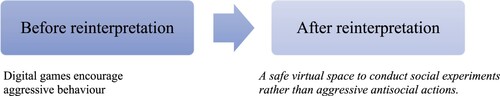

3.3.2. Social experimentation rather than aggressive actions

When the gamers act in social contexts (home, school, family) within the game, some of their actions can viewed as violent. The reinterpretation identifies that these actions, seemingly aggressive when viewed from the side, have a completely different meaning for the gamer: social experimentation. Its purpose is to cross the limits of social and moral standards and ethical behaviour to observe the consequences. Digital games facilitate such experimentation because it is not possible or acceptable in the real world. E. g.:

“I used to like to build houses and then start fires, or to take the ladder out of the pool so that the person drowns, and then we would create a cemetery behind the house:)) or we used to lock or barricade the person inside and when he could not communicate with others, he would go mad and then social bunny would come:)) … Also, this nasty orphanage lady would come to take away your children if you did not take good care of them. Or we used to not let them go to the bathroom so they would piss themselves.”

A different meaning of these aggressive anti-social actions, i.e. that they were not meant to hurt or injure, can be identified from the irony and black humour prevailing in this data incident conveying the understanding of the gamer that this is not real or serious (multiple smiling emojis) (see and ). The focus is shifted from the actions viewed as aggressive and anti-social to their meaning for the gamer: exploration whether the character can die in the game, whether you can play funeral, whether a person can go mad, whether there are social structures in place, etc. Aggressive anti-social actions become tools to perform a social experiment and to explore interest in their social consequences. Experimentation is related to the perception of the space, which you are experimenting in, as being safe and suitable for this type of experiments. Stereotypical attitudes seeing such actions as improper do not acknowledge the full awareness of the gamers that they are handling digital material. The recoding phase gives the in-game actions another meaning and value: not aggressive anti-social behaviour, but social experimentation and exploration of the possibilities of the digital game.

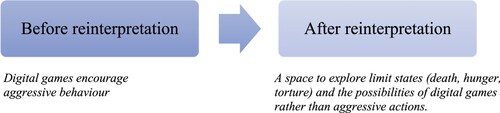

3.3.3. Exploration of limit states rather than aggressive actions

Digital games are a convenient space both for social experimentation and for the exploration of limit states. Exploration of limit states includes experimenting with human life (to burn a Sim, to make a Sim die of hunger, team member and you are killed) and physical body (we used to not let them go to the bathroom so they would piss themselves) and the exploration of human psychology (when he could not communicate with others, he would go mad, betrayed by your general) and violent behaviour (to lock a Sim in a cage). This exploration was not related to a wish to harm or torture. It was triggered by curiosity and by the desire to understand the logic of digital games, explore and experiment:

“And then you start thinking, what if I lock a Sim away, what will happen? Will he be able to leave, or will he die of hunger? Can a Sim die of hunger anyway? And suddenly I feel it’s an important thing to know. I am carrying out an experiment but no one is harmed.”; “I have played because there was this story where your closest team member and you are killed. And you are shown the scene how they are burned. And you are betrayed by your general.”

The reinterpretation identifies that the seemingly aggressive actions are actually only intended to explore (see and ). Outwardly they can look like aggressive behaviour but after shifting focus to their meaning for the gamer, another meaning (experimentation) is revealed. The exploration of limit states cannot be disassociated from digital games because the gamer clearly understands that it is only possible within the game; besides, after shifting focus from viewing these actions as aggressive to the concept that they manipulate technology (digital games), these actions (lock away, burn, etc.) represent the intention to understand how this technology works (how the game will treat it). Aggressive actions are being recoded to actions intended to explore limit states and the technological possibilities of digital games.

3.3.4. Emotional training rather than aggressive actions

In this study, emotional training is interpreted as a process that includes triggering and experiencing various strong emotions and feelings in different in-game situations in search of emotional discharge and emotional control. To a bystander, emotional training looks like aggressive in-game actions (shooting, fight, battle, etc.) but they often have a different meaning for and a different effect on the players: they are only used to conduct emotional training or serve as a background for it.

… GTA, it’s a phenomenal game. You can experience the life of a criminal there. The life of a violent person. You can torture your victims there. But if this makes you feel disgusted and uncomfortable while playing, … then it pushes you even further away so you won’t do that.

4. Discussion

The findings of the study show that the gamers seek to reinterpret the negatively viewed characteristics of digital games associated with promoting aggression by revealing their different meanings for the gamers themselves. Reinterpretation processes include contemplating such characteristic, disassociating it from negative stereotypes or their preconditions and giving it another meaning. Three reinterpretation process types that disrupt stereotypes emerged: a process that includes disassociating the negatively stereotyped characteristic from the game, decoding it into individual elements, and reinterpreting them differently than in the general context; a process that tears apart the interaction between humans and games and separates their boundaries by attributing this negatively viewed characteristic to human actions; and a process that shifts focus from aggressive in-game actions to their positive meaning for the gamers. A number of reinterpretation methods emerged. Handling of virtual material rather than aggressive actions: emphasising that in-game aggression only works with virtual material without any negative consequences and is not a real aggression. Open in-game actions visible to everyone rather than aggressive actions: emphasising the following characteristic of digital games as the media: all actions including aggression are visible to bystanders and become a precondition for certain stereotypes. Digital games do not encourage aggressive behaviour, aggressive behaviour is in human nature: emphasising a natural human inclination to aggression and viewing digital games only as a space to express this natural tendency. A space to sublimate masculine powers rather than aggressive actions: shifting focus from aggression to the possibility to sublimate masculine energy when unable to express it otherwise. Social experimentation rather than aggressive actions: emphasising the use of aggression to explore social boundaries rather than to hurt anyone. Exploration of limit states rather than aggressive actions: emphasising the exploration of limit states and in-game possibilities. Emotional training rather than aggressive actions: emphasising the exploration of repulsive emotions triggered by aggression.

The research findings that emerged in our paper explain how digital game players reinterpret the stereotype associated with digital games. The need to reinterpret the characteristic of digital games associated with aggressive behaviour is explained by Nauroth et al.’s (Citation2014) study, which shows that gamers tend to underestimate research-based arguments about the harm caused by playing digital games. Nauroth et al. (Citation2014) argue that this is because for gamers, such research findings imply a stigmatisation of their group and threaten their positive social identity. Thus, the emergent main concern of gamers – the stereotyping of digital games – and their high sensitivity to this aspect, according to Nauroth et al. (Citation2014), is the desire to defend the image of the group and their social identity.

The findings of our research are in line with Elson and Ferguson (Citation2014), who suggest that younger people are less likely to disparage new media or to see it as a source of societal ills. Research by Belda-Medina and Calvo-Ferrer (Citation2022) also shows that young people already recognise the value of digital games for learning, productivity, and high achievement.

Other researchers (Greitemeyer, Citation2022; Unsworth et al., Citation2007) have also found that games have no detrimental effects or can even have a positive (cathartic) effect, when players release their aggressive impulses, which leads to a decrease in anger after playing. These findings are consistent with the gamers’ interpretations in our study that certain aggressive actions and behaviour in the game have a positive effect on the gamers (help to release emotions, sublimate certain powers). Research also shows that gamers’ pre-game feelings and inclination to aggression predict aggressive actions in the game (Unsworth et al., Citation2007), and that a harsh upbringing that provokes anger increases the risk of aggressive behaviour online (Jingli Wu, Citation2022). The study by Kahila et al. (Citation2022) revealed that adolescents’ irritation during the game was triggered by repeated losses, losses at critical moments, comparison with others, incompetent teammates, cheating opponents, rather than violent content. This relates to the gamers’ interpretation, which emerged in our study, that aggressive actions in the game are triggered by the human factor rather than the digital game.

Research by Devilly et al. (Citation2023) suggests that there is no difference in the effect of the type of media (TV show, video game, book, video and so on) on anger and aggression. The differential susceptibility to media effects model (DSMM) also focuses on gamers’ susceptibility to media effects, i.e. the human factor, rather than on differences in media effects on gamers (Piotrowski & Valkenburg, Citation2015). This is consistent with the gamers’ interpretations in our research data that other media have a similar relationship to aggression as digital games, but that games are more likely to be stereotyped because of their specificity, as all actions in games are visible.

The data emerging in our study that aggressive behaviour is being associated with the handling of virtual material rather than with actually aggressive behaviour is in line with the study by Van de Mosselaer (Citation2019), which has shown that the tedious, complex challenges and cruel events experienced in the game (being chased by monsters, being killed, favourite characters being killed, etc.), as well as the feelings of sadness, anger, or fear are perceived by the gamers as occurring only in the context of the game.

Several studies indirectly echo the interpretations of gamers emerging in our study that the in-game space facilitates social experimentation, when social boundaries are being explored without the desire to harm anyone. Studies have shown that gamers see video games as an environment, a safe space, where they are free to try anything out without any consequences, even things they would never want to do in real life (for example, walk up to a guy on the street and start insulting him) (Razum & Huić, Citation2023) and that actions in virtual worlds allow teenagers to experience things that are impossible in real life and to experiment with their behaviour to have eudaimonic experiences (Daneels et al., Citation2020). This suggests a didactic potential, i.e. digital games may be a suitable medium for the exploration of critical social behavioural limits, provided that these explorations are then deeply reflected in the educational processes involving the players.

The interpretations of gamers emerging in our study that aggressive in-game actions are used to explore repulsive emotional states, i.e. to carry out emotional training, partly correlate with a study by Allen and Anderson (Citation2021), which has shown that immoral behaviour in the game can have an opposite result, i.e. the feeling of guilt caused by it encourages moral self-purification. It was more difficult for the gamers to identify with immoral characters, which indicates a certain desire of the players to distance themselves from immoral behaviour. Studies of Rončević Zubković et al. (Citation2022) have shown that the ability of the gamers to try out three different roles in a row: that of a victim, an observer, and an offender, and to go through different experiences actually increases compassion in anti-bullying games. Another aspect has been revealed by the study of Daneels et al. (Citation2020): digital games can trigger eudaimonic feelings in teenagers that encourage them to think about the contradiction between their violent in-game actions and their actions in the real world, thus awakening deep transformative reflections about their lives. Research on the specific characteristics of digital games (Moulard et al., Citation2019; Van de Mosselaer, Citation2019) has revealed a connection between the experience of suspense and negative emotions in the game and satisfaction received from the game: the suspense felt during the game, the emotions of hope and fear, as well as losing, disappointment and grief increase excitement and the pleasure obtained from the game. These studies support the didactic potential, i.e. that the space of a game is suitable for emotional training, thus creating possibilities for digital game-based learning to develop the socio-emotional competences of the players (Mukund et al., Citation2022).

It has emerged during the study that when reinterpreting this particular characteristic of digital games – that they encourage aggressive behaviour – gamers tend to shift the focus from aggressive actions to the possibility provided by the game to sublimate masculine energy when it cannot be expressed otherwise. A study by Scholes et al. (Citation2022) has revealed that boys, who are growing up in a specific social environment and who may be experiencing bullying in real life, choose to play games with a hyper-masculine image that, e.g. involve stealing cars, exercising power, etc. Research by Bonnaire and Conan (Citation2024), which highlights the profile of gamers who prefer violent video games, has shown that these games tend to be played by men who seek high sensations, adventure, risk, and competition. A study by Vilasís-Pamos and Pires (Citation2022) identifies game practices among teenagers, such as “escapist-gamer” or “ashamed-gamer”, that shows the need of the boys to escape from the real social context influenced by patriarchal masculinity models, which they may struggle to fulfil. These studies support the interpretations of gamers emerging in our research that aggressive “masculine behaviour patterns” in the game allow them to release the tension and sublimate the masculine energy. Other studies show that aggressive in-game actions are characteristic not only of men, but also of women. A study of Zhang and Gao (Citation2022) has demonstrated the effect of the gender of an avatar on aggressive behaviour. Identification with a same-sex avatar in violent games has been found to have led to a more aggressive behaviour short-term, with girls who use a same-sex avatar when playing being more aggressive than boys. On the other hand, a study by Waddell (Citation2020) shows that women are more likely to approve of the regulation of violent video games, while for men, the presence of violent details in games did not have a significant effect on their attitudes towards regulation. Based on the data of our research, it can be assumed that men are more forgiving of violent actions in the game because they interpret the in-game space as an opportunity to sublimate masculine energy.

There are studies whose findings contradict the gamers’ interpretations that emerged in our study. Playing competitive games has been found to be a direct predictor of aggressive behaviour in the long term (Adachi & Willoughby, Citation2016; Hawk & Ridge, Citation2021). In competitive games, the goal is always to win the competition, and the opponent’s actions always get in the way of achieving it, which leads to anger and aggressive behaviour. According to Anderson et al. (Citation2010), research shows that exposure to violent video games is a causal risk factor for increased aggressive behaviour, aggressive cognition and aggressive affect as well as decreased empathy and prosocial behaviour. The effects of exposure to violent video games have been significantly associated with more aggressive behaviour, and children may be more susceptible to such effects than young adults. These studies contradict the gamers’ reinterpretations of digital games that emerged in our research.

Hartmann et al. (Citation2014) found evidence that players intuitively perceived video game characters including virtual opponents not only as “dead pixels on screen” but also as social creatures and shot them because real violence became morally acceptable to them. According to Hartmann et al. (Citation2014), virtual violence is often accompanied by moral disengagement factors. The findings of this study contradict the gamers’ interpretations that emerged in our research, namely that gamers are consciously aware that they handle virtual material, that no real aggressive acts are being committed, and that no real harm is being done.

Further research is needed to develop the controversial aspects of the impact of digital gaming on gamers, but gamers of digital games themselves must be given a voice. As our research shows, externally observable processes and actions in games do not necessarily have the same meanings for gamers as for observers.

Research limitations: Our study did not distinguish between specific games or game types, so it did not demonstrate any game-specific reinterpretations of the stereotyped digital game characteristic in question (digital games encourage aggressive behaviour). Our study has identified aspects that are relevant to the participants of this particular field of study and the processes taking place in this field; therefore, other studies conducted in other fields of study may find different reinterpretation patterns. New aspects of the processes emerging in the study could be revealed through the use of other research methods and methodologies.

Our research suggests the following implications. Stereotyping a complex phenomenon such as digital games, simplifying it down to a single negative characteristic (digital games encourage aggressive behaviour), and attributing this characteristic to the whole phenomenon of gaming, provokes gamers to underestimate the research-based arguments and to reinterpret it in their own way. To have a preventive effect, i.e. to prevent the emergence of potentially aggressive behaviour when playing digital games, it is necessary not only for researchers, but also for public representatives and teachers to engage in a professional dialogue with the wider community of gamers, without stereotyping. For this dialogue to be effective, it is important to discuss specifically the types, content, elements, and modes of digital games that have an impact on the aggressive behaviour of gamers with certain characteristics and not to rely on general stereotypical phrases.

The processes of reinterpretation of a stereotyped digital game characteristic brought up by gamers can help to outline directions for the prevention of aggressive behaviour: to look back at one’s personality and qualities, to reflect on one’s real needs, to try to overcome the habits of aggressive behaviour by improving prosocial communication (Digital games do not encourage aggressive behaviour, aggressive behaviour is in human nature); to release the excess of energy and the accumulated emotions (A space to sublimate masculine powers rather than aggressive actions); to develop skills for regulating negative emotions and stress and managing playtime (Emotional training rather than aggressive actions);to learn to make meaningful use of the possibilities of the digital environment, seeking to understand real-life problems and to resolve them safely (Handling of virtual material rather than aggressive actions; Exploration of limit states rather than aggressive actions); etc.

5. Conclusion

The results of our study reveal processes related to the reinterpretation of the stereotyped digital game characteristic, namely that digital games encourage aggressive behaviour, which makes it necessary to reconsider motives behind aggressive in-game actions not only from a stereotypically negative point of view but also from the perspective of the gamers. The study revealed three types of reinterpretation processes that disrupt stereotypes: a process that includes disassociating the negatively stereotyped characteristic from the game, decoding it into individual elements, and reinterpreting them differently than in the general context; a process that tears apart the interaction between humans and games and separates their boundaries by attributing this negatively viewed characteristic to human actions; and a process that shifts focus from aggressive in-game actions to their positive meaning for the gamers. The findings suggest didactic potential, i.e. digital games may be a suitable medium for the development of socio-emotional competences, emotional training and exploration of the critical limits of social behaviour, provided that they are accompanied by deep reflections, spontaneous or moderated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Birutė Vitytė

Birutė Vitytė is a Doctor of Social Sciences (Education), Lecturer at Vytautas Magnus University Education Academy. Her major research interests include digital games-based learning, visual art education, early childhood education.

Ona Monkevičienė

Ona Monkevičienė is a Doctor of Social Sciences (Education, Psychology), Professor at Vytautas Magnus University Education Academy, chairman of the Transformative Educational Research cluster. Her major research interests include curriculum theories, pedagogical strategies of education, inclusive education, prevention of emotional, social and behaviour problems, social justice. Professor actively creates and develops national programs for development of children coping and social skills.

References

- Adachi, P. J. C., & Willoughby, T. (2016). The longitudinal association between competitive video game play and aggression Among adolescents and young adults. Child Development, 87(6), 1877–1892. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12556

- Allen, J. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2021). Does avatar identification make unjustified video game violence more morally consequential? Media Psychology, 24(2), 236–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1683030

- Anderson, C. A., Shibuya, A., Ihori, N., Swing, E. L., Bushman, B. J., Sakamoto, A., Rothstein, H. R., & Saleem, M. (2010). Violent video game effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in eastern and western countries: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018251

- Beerthuizen, M. G. C. J., Weijters, G., & van der Laan, A. M. (2017). The release of grand theft auto V and registered juvenile crime in The Netherlands. European Journal of Criminology, 14(6), 751–765. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370817717070

- Belda-Medina, J., & Calvo-Ferrer, J. R. (2022). Preservice teachers’ knowledge and attitudes toward digital-game-based language learning. Education Sciences, 12(182), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030182

- Bonnaire, C., & Conan, V. (2024). Preference for violent video games: The role of emotion regulation, alexithymia, affect intensity, and sensation seeking in a population of French video gamers. Psychology of Popular Media, 13(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000449

- Carnagey, N., Anderson, C., & Bushman, B. (2007). The effect of video game violence on physiological desensitization to real-life violence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(3), 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.05.003

- Chen, V. H. H., Wilhelm, C., & Joeckel, S. (2020). Relating video game exposure, sensation seeking, aggression and socioeconomic factors to school performance. Behaviour & Information Technology, 39(9), 957–969. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2019.1634762

- Coyne, S. M., Warburton, W., Swit, C., Stockdale, L., & Dyer, W. J. (2023). Who is most at risk for developing physical aggression after playing violent video games? An individual differences perspective from early adolescence to emerging adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(4), 719–733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01739-0

- Cudo, A., Kopiś-Posiej, N., & Griffiths, M. D. (2023). The role of self-control dimensions, game motivation, game genre, and game platforms in gaming disorder: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 4749–4777. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S435125

- Dahalan, F., Alias, N., & Shaharom, N. M. S. (2024). Gamification and game based learning for vocational education and training: A systematic literature review. Education and Information Technologies, 29(2), 1279–1317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11548-w

- Daneels, R., Vandebosch, H., & Walrave, M. (2020). “Just for fun?”: An exploration of digital games’ potential for Eudaimonic media experiences among Flemish adolescents. Journal of Children and Media, 14(3), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2020.1727934

- Devilly, G. J., O’Donohue, R. P., & Brown, K. (2023). Personality and frustration predict aggression and anger following violent media. Psychology, Crime & Law, 29(1), 83–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2021.1999949

- Elson, M., & Ferguson, C. J. (2014). Twenty-five years of research on violence in digital games and aggression: Empirical evidence, perspectives, and a debate gone astray. European Psychologist, 19(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000147

- Ferguson, C. J. (2008). The school shooting/violent video game link: Causal relationship or moral panic? Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 5(1-2), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.76

- Ferguson, C. J., & Wang, J. C. K. (2019). Aggressive video games are Not a risk factor for future aggression in youth: A longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(8), 1439–1451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01069-0

- Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussion. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G. (2001). The grounded theory perspective: Conceptualization contrasted with description. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G. (2002). Conceptualization: On theory and theorizing using grounded theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100203

- Glaser, B. G. (2004). Naturalist inquiry and grounded theory. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-5.1.652

- Glaser, B. G. (2016). The grounded theory perspective: Its origins and growth. Grounded Theory Review, 15(1), 4–9.

- Glaser, B. G. (2018). Getting started. Grounded Theory Review, 17(1), 3–6. Sociology Press.

- Greitemeyer, T. (2022). The dark and bright side of video game consumption: Effects of violent and prosocial video games. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46(101326), 1–5.

- Groves, C. L., & Anderson, C. A. (2017). Negative effects of video game play. In R. Nakatsu, M. Rauterberg, & P. Ciancarini (Eds.), Handbook of digital games and entertainment technologies (Vol. 1, pp. 1297–1322). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-50-4_13

- Hartmann, T., Krakowiak, K. M., & Tsay-Vogel, M. (2014). How violent video games communicate violence: A literature review and content analysis of moral disengagement factors. Communication Monographs, 81(3), 310–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2014.922206

- Hawk, C. E., & Ridge, R. D. (2021). Is it only the violence? The effects of violent video game content, difficulty, and competition on aggressive behaviour. Journal of Media Psychology, 33(3), 134–144. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000291

- Holton, J. A. (2009). Qualitative tussles in undertaking a grounded theory study. Grounded Theory Review, 8(3), 37–49.

- Holton, J. A., & Walsh, I. (2017). Classic grounded theory: Applications with qualitative and quantitative data. Sage Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071802762

- Kahila, J., Viljaranta, J., Kahila, S., Piispa-Hakala, S., & Vartiainen, H. (2022). Gamer rage—children’s perspective on issues impacting losing one’s temper while playing digital games. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 33, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2022.100513

- Kiili, K., Siuko, J., & Ninaus, M. (2023). Tackling misinformation with games: A systematic literature review. Interactive Learning Environments, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2294772

- Kirstavridou, D., Kousaris, K., Zafeiriou, C., & Tzafilkou, K. (2020). Types of game-based learning in education: A brief state of the art and the implementation in Greece. The European Educational Researcher, 3(2), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.31757/euer.324

- Kowert, R., Festl, R., & Quandt, T. (2014). Unpopular, overweight, and socially inept: Reconsidering the stereotype of online gamers. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0118

- Kücklich, J. (2006). Literary theory and digital games. In J. Rutter & J. Bryce (Eds.), Understanding digital games (pp. 95–111). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205430701528630

- Markey, P. M., Ivory, J. D., Slotter, E. B., Oliver, M. B., & Maglalang, O. (2020). He does not look like video games made him do it: Racial stereotypes and school shootings. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(4), 493–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000255

- Miedzobrodzka, E., Konijn, E. A., & Krabbendam, L. (2021). Emotion recognition and inhibitory control in adolescent players of violent video games. Journal of research on adolescence, 32(4), 1404–1420. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12704

- Miedzobrodzka, E., van Hooff, J. C., Krabbendam, L., Konijn, A., & A, E. (2023). Desensitized gamers? Violent video game exposure and empathy for pain in adolescents – an ERP study. Social Neuroscience, 18(6), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2023.2284999

- Moulard, J. G., Kroff, M., Pounders, K., & Ditt, C. (2019). The role of suspense in gaming: Inducing consumers’ game enjoyment. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(3), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2019.1689208

- Mukund, V., Sharma, M., Srivastva, A., Sharma, R., Farber, M., & Chatterjee Singh, N. (2022). Effects of a digital game-based course in building adolescents’ knowledge and social-emotional competencies. Games for Health Journal, 11(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2021.0138

- Nauroth, P., Gollwitzer, M., Bender, J., & Rothmund, T. (2014). Gamers against science: The case of the violent video games debate. European Journal of Social Psychology, 44(2), 104–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1998

- Piotrowski, J. T., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2015). Finding orchids in a field of dandelions: Understanding children’s differential susceptibility to media effects. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(14), 1776–1789. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764215596552

- Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., & Kinzer, C. K. (2015). Foundations of game-based learning. Educational Psychologist, 50(4), 258–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2015.1122533

- Prensky, M. (2001). Digital game-based learning. McGraw-Hill.

- Razum, J., & Huić, A. (2023). Understanding highly engaged adolescent gamers: Integration of gaming into daily life and motivation to play video games. Behaviour & Information Technology, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2023.2254856

- Rončević Zubković, B., Kolić-Vehovec, S., Smojver-Ažić, S., Martinac Dorčić, T., & Pahljina-Reinić, R. (2022). The role of experience during playing bullying prevention serious game: Effects on knowledge and compassion. Behaviour & Information Technology, 41(2), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2020.1813332

- Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. MIT Press.

- Scholes, L., Mills, K. A., & Wallace, E. (2022). Boys’ gaming identities and opportunities for learning. Learning, Media and Technology, 47(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1936017

- Scott, H. (2012). Conducting grounded theory interviews online. In V. B. Martin & A. Gynnild (Eds.), Grounded theory: The philosophy, method, and work of barney glaser (pp. 15–30). BrownWalker Press.

- SELL. (2022). Syndicat dės editeurs de logiciels de loisirs. L‘esentiel du jeu video. Les Francais et le jeu video. https://www.sell.fr/sites/default/files/essentiel-jeu-video/lessentiel_du_jeu_video_nov_22_0.pdf

- Statista. (2024). https://www.statista.com/statistics/1263585/top-video-game-genres-worldwide-by-age/

- Unsworth, G., Devilly, G., & Ward, T. (2007). The effect of playing violent video games on adolescents: Should parents be quaking in their boots? Psychology, Crime & Law, 13(4), 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160601060655

- Van de Mosselaer, N. (2019). Only a game? Player misery across game boundaries. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 46(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/00948705.2019.1613411

- Vilasís-Pamos, J., & Pires, F. (2022). How do teens define what it means to be a gamer? Mapping teens’ video game practices and cultural imaginaries from a gender and sociocultural perspective. Information, Communication & Society, 25(12), 1735–1751. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1883705

- Voulgari, I., & Lavidas, K. (2020). Student teachers’ game preferences, game habits, and attitudes towards games as learning tools. In Proceedings of the European conference on games based learning (pp. 646–654). https://doi.org/10.34190/GBL.20.175.

- Waddell, T. F. (2020). Do press releases about digital game research influence presumed effects? How details about methodology and references to societal violence affect the anticipated influence of violent video games. Mass Communication and Society, 23(3), 400–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2019.1672751

- Wu, J. (2022). Exploring the process of harsh parenting on online aggressive behaviour: The mediating role of trait anger. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(5), 508–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2022.2121035

- Xie, J., Wang, M., & Hooshyar, D. (2021). Student, parent, and teacher perceptions towards digital educational games: How they differ and influence each other. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 13(2), 142–160. https://doi.org/10.34105/j.kmel.2021.13.008

- Zhang, Q., & Gao, J.-Y. (2022). Effects of same-sex avatar versus opposite-sex avatar violent video games on aggressive behavior among Chinese children. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 31(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2021.1984351