Abstract

Narrative ads are more appreciated and more persuasive than non-narrative ads. This superior effect is ascribed to the pleasant, entertaining experience narrative ads provide. Humorous narratives do so by evoking positive emotions and providing a hedonic experience. There are also ads that tell moving stories thereby evoking negative emotions too and providing a eudaimonic experience. In two studies, the questions are addressed to what extent moving ads evoke both positive and negative emotions and what their impact is on the attitude toward the ad. In each study, 96 participants saw and evaluated three narrative ads: a humorous ad, a joyfully moving ad, and a sadly moving ad. The results reveal that whereas humorous ads evoked only positive emotions and provided a hedonic experience, the moving narrative ads evoked positive and negative emotions, and provided a eudaimonic experience. Nevertheless, the attitude toward the moving ads was as high, or even higher, than those of the humorous ads. These results thus show that for a thorough understanding of how narrative ads exert their influence, it is important to distinguish whether they aim to provide a hedonic or a eudaimonic experience and that eliciting negative emotions may lead to a better liked ad.

Introduction

In 2015, John Lewis launched a Christmas commercial in which a little girl spots a lonely old man on the moon, tries repeatedly yet unsuccessfully to come into contact with him, and then, when Christmas comes, sends a spyglass that enables them to see each other, liberating the old man from his loneliness. In the comments on Youtube, viewers confess that they felt sad, cried their heart out, but also appreciated the commercial very much. This commercial is a good example of a narrative commercial (Escalas, Citation1998): it contains a character (the little girl) that finds itself in a situation (spotting the lonely man), sets itself a goal (getting into contact), and takes action to attain that goal. The outcome influences the character’s mindset as the failure of her early attempts make her sad, while her ultimate success makes her (and the old man) happy.

Kim et al. (Citation2017) show that narrative commercials yield more positive attitudes toward the ad and the brand compared to non-narrative commercials providing factual information. They argue that the narrative commercials’ persuasive superiority results from their hedonic value, that is ‘the extent to which a viewer finds the content of an ad to be pleasurable and entertaining’, which is, ‘by definition (…) always positively valenced’ (2017, p. 287). Meta-analyses provide ample evidence for the relation between pleasant experiences and positive ad-evoked emotions on the one hand, and the attitudes toward the ad and toward the brand on the other (Brown et al., Citation1998; Eisend, Citation2011). Especially humor is used extensively to provide viewers with a pleasurable experience. Indeed, meta-analyses reveal that humorous ads (compared to non-humorous ads) yield more positive attitudes toward the ad as well as toward the brand (Eisend, Citation2011; Walter et al., Citation2018).

Against this backdrop, the John Lewis commercial provides an intriguing case. It does not make the audience laugh; it saddens it. Whether narrative commercials that evoke negative emotions are liked as well or even better than their humorous counterparts, is both a theoretically and practically relevant question. From a theoretical point of view, it deepens our understanding of what fuels the persuasive superiority of narrative commercials compared to non-narrative ones. That is, do the emotions evoked by the narrative commercial need to be positive for a positive effect to occur on the attitude toward the ad? Or can negative emotions have this effect as well? In addressing this question, this study also responds to the call by Poels and Dewitte (Citation2019, pp. 85-86) who state that it is “particularly interesting” to study negative emotions as these “are currently underused as commercial ad appeals in favor of seemingly safer to use positive emotions”. This latter remark brings us to the study’s practical relevance: eliciting negative emotions may help advertising managers to make their message stand out from the clutter. But does this strategy subsequently damage the attitude toward the ad or will it have a positive effect on the attitude?

Literature review

Positive, negative, and mixed emotions in advertising

In the past 35 years, research has documented the importance of emotions for advertising effectiveness (see, e.g., Aaker et al., Citation1986; Batra & Ray, Citation1986; Burke & Edell, Citation1989; Edell & Burke, Citation1987; Holbrook & Batra, Citation1987). Meta-analytic reviews of such studies reveal that ad-evoked positive emotions are positively correlated with the attitude toward the ad and the attitude toward the brand, whereas ad-evoked negative emotions are negatively correlated (Brown et al., Citation1998; Eisend, Citation2011). In a large scale study analyzing responses of over 1500 consumers to over 1000 commercials, Pham et al. (Citation2013) also found that ad-evoked emotions were significantly correlated with the attitudes toward the ad and toward the brand. These findings suggest a simple picture: ads that evoke positive emotions are more appreciated as are the brands featured in these ads. Evoking negative emotions has the opposite effect.

Apart from evoking either positive or negative emotions, some ads elicit both. Bennett (Citation2015), for instance, developed print ads for a fictitious charity organization in which pictures of animals or children in distress evoked negative emotions whereas the verbal part provided hopeful information on how the charity could remedy the situation thereby evoking positive emotions. He reported positive correlations between experiencing mixed emotions and the attitude toward the ad and the behavioral intention to support the organization. Similar effects of evoking mixed emotions have been reported in other studies as well (see, e.g., Bae, Citation2021; Hong & Lee, Citation2010; Janssens et al., Citation2007; Williams & Aaker, Citation2002). In these studies, emotions are elicited through appealing to the emotional consequences of the advocated behavior (Gong & Cummins, Citation2020). But emotions can also be elicited by narrative commercials.

Narrative commercials and emotions

Narrative commercials do not provide factual information on the advertised product’s attributes or the consequences of using it. As Escalas (Citation1998, p. 274) defines it: “a narrative ad is simply an ad that tells a story”. More specifically, she considers as typical for a narrative commercial the representation of chronologically and causally related events in which one or more characters are involved. Kim et al. (Citation2017) had participants respond to 25 narrative commercials and 25 non-narrative commercials. They found the former more emotionally involving, pleasurable and entertaining than the latter. Not only did narrative commercials elicit emotions to a stronger extent than non-narrative commercials, this difference in emotional experience proved instrumental for the more positive attitudes toward the ad and the brand that resulted from viewing the narrative commercials compared to the non-narrative commercials.

Kim et al. (Citation2017) showed that the extent to which people considered the ad entertaining was essential for its superior persuasive effect. Many narrative ads aim to entertain by telling a humorous story. Yelkur et al. (Citation2013), for instance, showed that 69.2% of all Super Bowl commercials aired in the period from 2000 till 2009 contained humor; the presence of humor proved to be the strongest predictor of ad liking. Humorous stories fall into the category of what Oliver et al. (Citation2012) call hedonic entertainment. Hedonic entertainment is characterized by evoking mainly positive emotions, typical examples being comedies, such as The Hangover and The 40 year old virgin. Oliver et al. refer to these movies as pleasurable narratives. They contrast pleasurable narratives with what they call meaningful narratives, examples being Schindler’s list and Hotel Rwanda. These movies provide eudaimonic entertainment, characterized by evoking both positive and negative emotions, for instance, joy and sadness. The John Lewis Christmas commercial discussed in the introduction is an example of a narrative commercial providing eudaimonic entertainment.

The experiencing of mixed emotions, especially joy and sadness, has been identified as a defining characteristic of ‘being moved’ (Cova & Deonna, Citation2014; Menninghaus et al., Citation2015). Oliver et al. (Citation2012, p. 364) relate the feeling of being moved to eudaimonic entertainment provided by meaningful narratives. So, what kind of story needs to be told in order to move its audience? For a story to be moving, it should represent acts of moral virtue (Cova & Deonna, Citation2014) or prosocial behavior (Konečini, Citation2005), examples being forgiveness, sacrifice, and generosity. Menninghaus et al. (Citation2015) had participants describe an event that had moved them. Their results revealed that people were moved predominantly by relationship events (concerning friendship, parent-child interaction, confession, and reconciliation) and critical life events (notably death and funerals). Oliver et al. (Citation2012) also suggest that ‘meaningful’ films are more likely to portray altruistic values (e.g., care for the weak) and the importance of family relations (e.g., safety of loved ones).

In sum, narratives can provide hedonic entertainment, which is characterized by experiencing positive emotions that are typically elicited by humorous narratives. However, narratives can also provide eudaimonic entertainment, characterized by experiencing positive and negative emotions, typically elicited by narratives about prosocial acts or relationship events. To what extent are these latter ads appreciated?

Meaningful narratives in commercials

Wu and Dodoo (Citation2017) have studied meaningful narrative advertisements. They had participants evaluate two different commercials: one from Under Armor about achievement, telling the story of the ballerina soloist of the American Ballet Theater who had received a rejection letter of a ballet school as a little girl. The other commercial was from Guinness and featured friendship and altruism: six men play a game of wheel chair basketball at the end of which it becomes clear that only one of them is handicapped, the other five playing in a wheel chair for his benefit. Participants were asked, amongst others, the extent to which they felt moved and experienced a warm feeling in their chest. Their results showed that these experiences positively influenced the attitude toward the ad and the attitude toward the brand. Wu and Dodoo (Citation2017, p. 607) conclude that for ads telling meaningful stories, “the term “positive feelings” alone may not sufficiently describe individuals’ advertisement viewing experience”.

Wu and Dodoo (Citation2017) studied two meaningful advertisements. Therefore it is unclear whether these kind of narrative commercials are more, less or equally effective as commercials telling a humorous story. Wu (Citation2019) reported on two experiments in which he assessed whether ads telling a meaningful story led to more positive attitudes toward the ad than an ad telling a romantic (Study1) or a funny story (Study 2). In both studies, the ads telling meaningful stories were significantly higher appreciated than the other ads. These results suggest that ads providing eudaimonic entertainment may be even more effective than those providing hedonic entertainment. Wu and Dodoo (Citation2017) discuss that there may be other ads that are good illustrations of meaningful narrative advertisements. A relevant distinction could be between meaningful narratives that ultimately have a happy ending and those with a sad ending.

Joyfully and sadly moving stories

Wassiliwizky et al. (Citation2015) distinguish between two types of moving stories: joyfully and sadly moving ones. In the case of joyfully moving stories, “uplifting events dominate the scene (…) yet it only becomes moving because either some negatively evaluated memories of a preceding unhappy state are reactivated or some saddening aspects of the scene itself are blended with the positive event” (Wassiliwizky et al., Citation2015, p. 407). The John Lewis commercial referred to in the introduction or the Guinness wheel chair basketball commercial used by Wu and Dodoo (Citation2017) are examples of joyfully moving stories with the old man’s loneliness and the man in a wheel chair evoking a sad background whereas the prosocial behaviors of the little girl and the man’s friends provide the uplifting events.

For sadly moving stories, the valence of the background and foreground are reversed. That is, the negative emotions dominate yet there are positive emotions as well. Wassiliwizky et al. consider as typical examples scenes in which a character learns about the death of a loved one. Whereas this news and the character’s response to it constitute the negative foreground, the positive background is often provided by, for instance, the selflessness or courage displayed by the deceased or the strong bond between the characters. An example is a Johnny Walker commercial displaying the bond between two brothers as a positive background, whereas at the end it becomes clear that one of them has died. To the best of our knowledge, research on moving narrative commercials has restricted itself to joyfully moving ones. This raises the question to what extent the more gloomy, sadly moving narratives provide entertainment can have a positive impact on the attitude toward the ad.

Research hypotheses and question

Emotions play an important role in establishing a positive attitude toward the ad (Pham et al., Citation2013). Especially narrative ads are effective in bringing about these emotions (Kim et al., Citation2017). There is ample evidence for the importance of positive emotions whereas there is a paucity of research on the impact of negative emotions (Poels & Dewitte, Citation2019). In this paper, we report two studies in which we compare the appreciation of three different types of narrative ads: humorous, joyfully moving, and sadly moving ones. There is abundant evidence for the positive impact of humorous ads (Eisend, Citation2011; Walter et al., Citation2018), which makes them a strict criterion to compare the impact of moving ads to. As a first step, we aim to assess what emotions are to what extent elicited by the different commercials using self-report measures. The first two hypotheses are:

H1. Humorous ads will evoke mainly positive emotions whereas moving ads will evoke both negative and positive emotions.

H2. Joyfully moving ads will evoke positive emotions more strongly and negative emotions less strongly than sadly moving ads.

Humorous and moving movies have been shown to evoke different physiological responses associated with the hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment; hedonic entertainment is associated with a smile, relaxation, and energy (Oliver et al., Citation2012). Eudaimonic entertainment is experienced as a lump in one’s throat, goose pimples, and tears in one’s eye (Cova & Deonna, Citation2014). Schubert et al. (Citation2018) had participants watch short clips that were considered moving with some participants rating the emotion of being moved, whereas others reported on their physiological experiences. They obtained strong positive correlations between changes in the emotion of being moved, and the experience of weeping, chest warmth, and goose bumps. We thus expect that humorous ads are associated more strongly with smiling, relaxing, and feeling energized, whereas the moving ads are associated more strongly with prickling tears, a lump in one’s throat, and goose pimples.

H3. Humorous ads will evoke hedonic physiological responses to a stronger extent and eudaimonic physiological responses to a weaker extent than moving ads.

Wu (Citation2019) found a more positive attitude toward the ad for a joyfully moving ad compared to a humorous ad. We aim to replicate this effect using different commercials.

H4. The attitude toward the ad for the joyfully moving ad will be more positive than that for the humorous ad.

On the one hand, studies have shown that the emotions elicited by ads are related to the attitude toward the ad (e.g., Eisend, Citation2011). Yet Kim et al. (Citation2017) claim that this attitude is determined by the level of entertainment narratives ads provide. As we measure both the self-reported individual emotions and the physiological experiences related to the entertainment experience, we can assess to what extent these different predictors (individual emotions, hedonic and eudaimonic experiences) predict the attitude toward the ad. This leads to the following research question:

RQ. To what extent is the attitude toward the ad determined by the emotions and physiological experiences evoked by the ad?

Study 1

To test the hypotheses, participants needed to watch and respond to humorous, joyfully moving, and sadly moving ads. The nature of an ad being humorous or moving depends essentially on the events and characters involved, therefore the ads differed on many dimensions. In addition, telling a moving story without it becoming tacky, is an art mastered by few scholars, and not by us. Therefore, we chose to use professionally produced ads that could be classified as either humorous, joyfully moving, or sadly moving based on how well the events depicted in the ads matched the definitions provided above. To assess whether this classification was experienced as intended, manipulation check items were employed. Finally, to assess the robustness of the results, we conducted two studies that were identical in design except for employing different sets of ads and different participant samples.

Method

Design

A single factor within-participants design was employed with each participant watching and responding to a humorous, a joyfully moving, and a sadly moving commercial. There were six versions that differed in the order in which the ads were presented. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the versions.

Procedure

Participants were approached individually either in the university library or in their home and asked whether they were willing to take part in a study on the appreciation of TV ads, resulting in a convenience sample. Participants watched the ads one by one on a 15.6 inch laptop and filled out the questionnaire after watching each ad. An experimental session lasted between ten and twenty minutes. After the session was completed, participants were debriefed about the study’s goal and any remaining questions were answered.

Participants

Ninety six native speakers of Dutch took part in the experiment (50% female). The mean age was 37.0 years (SD = 17.6) ranging from 16 to 68.

Materials

In the first study, three ads for alcoholic beverages were used. Because the three ads were in English, Dutch subtitles were added. Virtually all foreign language programs in the Netherlands are subtitled. The ads’ durations were 1:01, 1:12, and 1:30 minutes, respectively. The humorous ad, for Carlsberg beer, depicted a young man’s visit to a hair dresser, during which all kinds of things happen, such as a live band playing the song ‘Make my day’, mirrors reflecting beautiful landscapes, clients drinking beer while their mustaches are being shaved off, and so on. At the end of the ad a commentator says ‘If Carlsberg did haircuts, it probably would be the best in the world’. One participant had already seen this commercial.

The joyfully moving ad was for Guinness beer. The ad depicted six men playing an intense game of wheel chair basketball. There is soft background music and a voice-over saying “Dedication… loyalty… friendship…”. At the end of the game, five of the six players get up from their wheelchair, one of them commenting “we’re getting better at this” and another one saying “next week buddy”; it appears that they have all been playing in wheelchairs for the benefit of one friend who is handicapped. Then they go to the bar for a beer. At the end of the ad a voice-over says “The choices we make reveal the true nature of our character”. Eleven participants had already seen this commercial.

The sadly moving ad was for Johnnie Walker whiskey. Two men, with a clear family resemblance, walk through the foggy, rocky terrain of Scotland's Isle of Skye where they have spent their childhood: one of them more pensive, carrying something covered in cloth, the other more upbeat. A voiceover recites a poem about their experiences and their deep feelings for each other. Reaching a farm house ruin, they share some Johnnie Walker in a broken glass they find in the rubble. At the end, they reach a peak overlooking the sea, and the more upbeat brother disappears. The object covered in cloth turns out to be an urn, and the brother scatters the ashes over the sea while the final words of the poem are spoken: “And promise me from heart to chest to never let your memories die. Never. I will always be alive and by your side - In your mind - I’m free.” Four participants had already seen this commercial.

Questionnaire

First, the attitude toward the ad was measured employing the items used by Pham et al. (Citation2013). On seven-point scales, participants indicated to what extent they agreed with the statements “I like this ad” and “The ad is well-made” and responded to the question “My general evaluation of the ad is” on a scale ranging from “very negative” to “very positive”. The reliabilities of the scale were good (humorous: α = .84; joyfully moving: α = .89; sadly moving: α =.85).

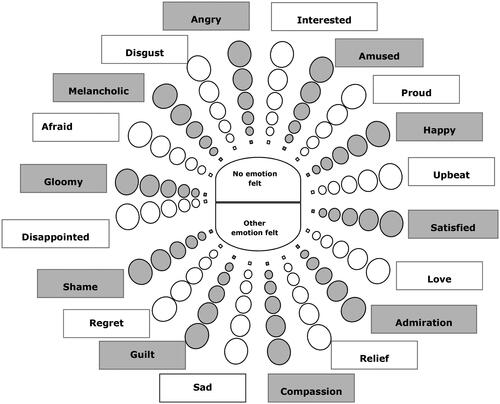

Emotions were measured with the Geneva Emotion Wheel (Sacharin et al., Citation2012). Twenty emotions were selected: interested, amused, proud, happy, upbeat, satisfied, love, admiration, relief, compassion, sad, guilty, regret, ashamed, disappointed, gloomy, afraid, melancholic, disgusted, angry (see Appendix 1). These were presented at the ends of the spokes of a wheel. In the middle of the wheel there was space to indicate that no emotion was felt, or another emotion could be mentioned. Participants had to respond for each of the emotions on a scale ranging from ‘not felt at all’ to ‘strongly felt’.

Next, participants were asked to indicate on seven-point Likert scales ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” the extent to which they had experienced certain physiological experiences described by Schubert et al. (Citation2018). Three items measured the hedonic experience: “smile on face”, “relaxing”, and “energetic”, with reliabilities being at least adequate (humorous: α = .80; joyful moving: α = .78; sadly moving: α =.71). The eudaimonic experience was also measured with three items: “goose bumps”, “tears in eyes”, and “lump in throat” (humorous: α = .78; joyfully moving: α = .81; sadly moving: α =.85).

Four seven-point Likert items (anchors: “strongly disagree” – “strongly agree”) were used as a manipulation check, to assess whether the ads were experienced by the participants as intended, for instance, “I consider this commercial humorous”, “heart-warming”, “gut-wrenching”, and “moving”. The humorous ad was expected to be perceived as the most humorous one, the joyfully moving ad as the most heart-warming one, and the sadly moving ad as the most gut-wrenching one. The joyfully moving and sadly moving ads were predicted to be considered more moving than the humorous one.Footnote1

Finally, after rating these ads, participants were asked for each ad whether they had seen it before, what brand was advertised for, as well as age, gender, education level, and whether they had children.

Results study 1Footnote2

In , the results for the manipulation check items are reported. For each of the variables, large significant effects were obtained with all three ads differing significantly from each other.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for the manipulation check items in study 1 (1 = very negative, 7 = very positive; different subscripts indicate significant differences).

The humorous ad was considered more humorous than the joyfully moving and the sadly moving ads. The joyfully moving ad was perceived as more heart-warming than the other ads, whereas the sadly moving ad was perceived as more gut-wrenching than the other two. The humorous ad was considered much less moving than the joyfully moving ad, which was less moving than the sadly moving ad.

In , the results for the twenty emotions measured in the Geneva emotion wheel are presented.Footnote3

Table 2. Means and Standard Deviations for Emotions Study 1 (0 = not felt at all, 6 = strongly felt; bold means differ significantly from zero; different subscripts indicate significant differences).

For each ad, it was assessed which emotions differed significantly from zero using one sample t-tests against a Bonferroni-corrected alpha of (.05/20 =) .0025. As predicted by hypothesis 1, the humorous ad evoked only positive emotions (admiration, amused, happy, interested, satisfied, and upbeat), whereas the joyfully and the sadly moving ads evoked other emotions as well, including negative ones (e.g., sad, melancholic). Finally, only the sadly moving ad evoked a feeling of gloom.

Secondly, for each emotion, a one way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to assess whether the emotion was evoked to a different extent by the different ads (again, a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons yielded an alpha of .0025 (.05/20). If a significant main effect was found, pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction were conducted. For ten emotions, a main effect was obtained. The results were in line with hypothesis 2: the joyfully moving ad evoked positive emotions (upbeat, happy, amused, admiration, proud) to a stronger extent than the sadly moving ad whereas the sadly moving ad evoked negative emotions (sad, melancholic, gloomy) to a stronger extent than the joyfully moving one.

Subsequently, separate oneway analyses with repeated measures were conducted for the perceived hedonic and eudaimonic physiological experiences. contains the results of these analyses.

Table 3. Means and standard deviations for the hedonic and eudaimonic physiological experience and attitude toward the Ad Study 1 (1 = very negative, 7 = very positive; different subscripts indicate significant differences).

For both the hedonic (F (2, 190) = 40.02, p < .001, ƞ2 = .296) and the eudaimonic experience (F (2, 190) = 100.83, p < .001, ƞ2 = .515), significant effects of ad type were found. Pairwise comparisons employing Bonferroni corrections revealed that the humorous ad evoked a stronger hedonic experience than the joyfully moving ad which in turn yielded a stronger hedonic experience than the sadly moving ad. For the eudaimonic experience, the humorous ad scored lower than the joyfully moving ad which in turn scored lower than the sadly moving ad. These results are in accordance with hypothesis 3 with the addition that the joyfully and sadly moving ads also differed from each other for these experiences. There was no effect of ad type on the attitude toward the ad (F (2, 190) = 1.92, p = .149) thereby finding no support for hypothesis 4.

Finally, for each ad separately, regression analyses were conducted to explore the extent to which the attitude toward the ad was predicted by demographic variables (block 1: age, gender, education level, being a parent, having seen the ad), those emotions that differed significantly from zero for each ad (block 2), and the hedonic and eudaimonic experiences (block 3). For none of the ads, entering the demographic variables increased the amount of explained variance significantly (p’s > .13). For all ads, entering the evoked emotions led to a significant increase of explained variance (p’s < .001). Importantly, subsequently entering the hedonic and eudaimonic experiences also led to a significant increase of explained variance (humorous ad: p = .011; joyfully moving ad: p = .007; sadly moving ad: p = .001.) For the humorous ad 48.0% of the variance was explained, with the hedonic experience (β = .294, p = .007) and feeling amused (β = .234, p = .029) as significant predictors. For the joyfully moving ad, 45.6% of the variance was explained, with the hedonic experience (β = .262, p = .042), admiration (β = .281, p = .01), and feeling interested (β = .250, p = .014) being significant predictors. Finally, for the sadly moving ad, 48.4% of the variance was explained but in this case, the number of significant predictors was larger: eudaimonic experience (β = .317, p = .002), feeling interested (β = .328, p < .001), admiration (β = .265, p = .009, gender with men having more a positive attitude toward the ad than women, (β = −.209, p = .018) and age (β = .221, p = .013). Appendix 2 contains the detailed results of the regression analyses.

Conclusion study 1

The large effects for the manipulation check items revealed that the three ads were experienced as intended. The first three hypotheses were supported: whereas the humorous ad evoked positive emotions only, both the joyfully and the sadly moving ads evoked positive and negative emotions (H1), with the sadly moving ad evoking stronger negative emotions and weaker positive ones than the joyfully moving one (H2). The humorous ad evoked the strongest hedonic physiological experience, whereas the two moving ads evoked a stronger eudaimonic experience, with the sadly moving ad doing so to a stronger extent than the joyfully moving ad (H3). However, there were no significant differences between the ads with respect to the attitude toward the ad, thus finding no support for hypothesis 4. Finally, for the humorous and the joyfully moving ad, the hedonic experience proved an important predictor for the attitude toward the ad even if the individual emotions were entered into the analysis first. For the sadly moving ad, the eudaimonic experience contributed to the prediction of the attitude toward the ad. In the second study, it was assessed to what extent a similar pattern could be obtained using different humorous, joyfully moving, and sadly moving ads.

Study 2

Method

Participants, design, instrumentation, and procedure

The questionnaire, design, and procedure were the same as Study 1. As in Study 1, 96 people took part in the study (49 women, 47 men). They had not taken part in the first study. Age ranged from 17 to 68, with a mean of 37.3 years (SD = 17.3). For each ad, the majority of the participants had already seen it: humorous ad (61.5%), joyfully moving ad (85.4%), and sadly moving ad (60.4%).

The reliabilities of the scales measuring the attitude toward the ad were good (.82 < Cronbach’s α < .90). The reliabilities of the scales measuring the hedonic physiological experience were adequate (humorous: α = .75; joyfully moving: α = .72; sadly moving: α = .71). The same was true for the scales measuring the eudaimonic physiological experience (humorous: α = .79; joyfully moving: α = .85; sadly moving: α =.89).

Materials

In this study, three Dutch ads were used. The sadly moving ad was about a funeral service insurance and involved a father and daughter. Instead of looking for humorous and joyfully moving ads from insurance companies, we searched for ads that also included a father-daughter storyline. The constant factor in the second study was thus not the product category, but the characters involved in the plot. This resulted in the following selection.

The humorous ad was for a chain of Do It Yourself shops. A father and daughter are shopping in one of those shops. The father is excited about the low prices. When the daughter bumps into a young shopping assistant, a spark flies between them and the assistant says: “Do you come here often?” The father interferes and says to his daughter “I hope you don’t fall for his cheap pick up line”. When they leave the shop, they look back and see the guy standing under a large sign stating “Always extra cheap” which leads the father to remark: “Well, he’s in exactly the right spot”.

The joyfully moving ad is about a brand of ginger bread. A young girl in soccer attire rides her bike through wind and rain, taking shelter under a bridge while thunder can be heard. Finally, she gets home where her father is putting butter on a piece of gingerbread. She sits on the kitchen top, clearly disappointed. Her father asks “Lost?” “Cancelled”, she replies. The father smiles and butters a second piece of gingerbread and hands it to her. She takes a bite and they smile at each other.

The sadly moving ad is about a funeral insurance. It starts with a man sitting in a car, building up courage, while looking at some adolescents who are hanging out. He leaves the car and takes a few steps toward the group. A girl turns around and with a sigh of annoyance, she walks toward him. As she nears him, her expression changes from annoyed to anxious and she questioningly shakes her head; the man nods sadly and she throws herself in his arms while he makes comforting noises. A text appears stating “surviving relatives are already burdened enough” followed by the logo of an insurance company and its tagline: “Support for every funeral”. The ads’ lengths were 35, 42, 35 seconds, respectively.

Results study 2Footnote4

In , the results for the manipulation check items are presented. The pattern of results was exactly the same as in Study 1 with large, significant effects for all comparisons.

Table 4. Means and standard deviations for the manipulation check items in study 2 (1 = very negative, 7 = very positive; different subscripts indicate significant differences).

The humorous ad was considered more humorous, the joyfully moving ad more heart-warming, and the sadly moving ad more gut-wrenching. Both moving ads were considered more moving than the humorous one, with the sadly moving ad being perceived as more moving than the joyfully moving ad.

In , the results for the twenty emotions measured in the Geneva emotion wheel are presented.Footnote5

Table 5. Means and standard deviations for emotions study 2 (0 = not felt at all, 6 = strongly felt; bold means differ significantly from zero; different subscripts indicate significant differences).

Again, the results are highly similar to those of the previous study. The humorous ad evoked the same positive emotions as in study 1, except for admiration being replaced by love and compassion. The two moving ads evoked both positive and negative emotions with the joyfully moving ad evoking positive emotions to a stronger extent than the sadly moving ad, whereas the opposite pattern is obtained for the negative emotions. Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 are thus supported in this study as well.

presents the results for the hedonic and eudaimonic physiological experiences as well as for the attitude toward the ad.

Table 6. Means and standard deviations for the hedonic and eudaimonic experience and attitude toward the Ad Study 2 (1 = very negative, 7 = very positive; different subscripts indicate significant differences).

Again, main effects of ad type were found for the hedonic (F (2, 190) = 148.85, p < .001, ƞ2 = .610) and the eudaimonic experience (F (2, 190) = 83.60, p < .001, ƞ2 = .468). Post hoc comparisons employing Bonferroni corrections revealed that for the hedonic experience, only the sadly moving ad scored lower than the other two ads with the joyfully moving ad not differing from the humorous ad. With respect to the eudaimonic experience, the sadly moving ad yielded higher scores than the joyfully moving ad which in turn scored higher than the humorous ad. Finally, there was a significant effect of ad type on the attitude toward ad (F (2, 190) = 5.50, p = .005, ƞ2 = .055). Comparisons revealed that the joyfully moving ad scored higher than the two other ads.

Similar regression analyses as in Study 1 were run (see Appendix 2 for the complete results). Again, entering the hedonic and eudaimonic physiological experiences in the third step did lead to a significant increase (p’s < .001) in the variance explained for the attitude toward the ad. For the humorous ad, 54.6% variance of the attitude toward the ad was explained. The only significant predictor proved to be the hedonic physiological experience (β = .604, p < .001). For the joyfully moving ad, 29.0% variance was explained, with the hedonic physiological experience being the only significant predictor (β = .520, p < .001). Finally, for the sadly moving ad, 61.6% of variance was explained. As in the previous study, there were more significant predictors: eudaimonic physiological experience (β = .426, p < .001), the hedonic physiological experience (β = .159, p = .031), interested (β = .239, p = .001), and compassion (β = .173, p = .042). In addition, disgust contributed negatively to predicting the attitude toward the ad (β = −.353, p < .001).

Conclusion study 2

Study 2 differed in important respects from Study 1: all the ads were Dutch, had already been seen by a relatively large number of participants, and were on very different products. Nevertheless, the first three hypotheses were (again) supported. In addition, hypothesis 4 was supported: the attitude toward the joyfully moving ad was higher than that for the other two ads. Finally, the hedonic physiological experience played a role in predicting the attitude toward the ad for all ads, whereas the eudaimonic experience only did so for the sadly moving ad.

General discussion

The first three hypotheses were supported in both studies: the humorous ad evoked positive emotions only, whereas both the joyfully and the sadly moving ads evoked positive and negative emotions (H1), with the sadly moving ad evoking stronger negative emotions and weaker positive ones than the joyfully moving one (H2). The humorous ad evoked the strongest hedonic physiological experience, whereas the two moving ads evoked a stronger eudaimonic experience, with the sadly moving ad doing so to a stronger extent than the joyfully moving ad (H3). Hypothesis 4 was only supported in Study 2: the attitude toward the joyfully moving ad in Study 2 was more positive than those toward the humorous and sadly moving ads. However, when analyzing the two studies as a single experiment, the results revealed that the attitude toward the joyfully moving ads was significantly higher than those toward the humorous and sadly moving ads.Footnote6 Finally, the research question was about the predictive strength of individual emotions compared to the hedonic and eudaimonic physiological experiences. The latter proved to be better predictors of the attitude toward the ad than the individual emotions.

Theoretical contributions

What are the theoretical implications of these findings? Firstly, the results provide more insight into the impact of negative emotions in commercial advertising as was called for by Poels and Dewitte (Citation2019). Most studies on negative emotions have been conducted within the context of charity advertising (see, e.g., Bae, Citation2021; Bennett, Citation2015), in which the negative emotions serve to signal the wrongs the charity aims to right. In this study, the appeal of negative emotions is studied in commercials for products such as beer, whiskey, or ginger bread. The link between these products and negative emotions is more farfetched in comparison to charity advertising. In combination with the results reported by Wu (Citation2019), this study nevertheless suggests that the attitude toward these ads is at least as positive, and in some cases even more positive, than that toward ads using humor. This is striking as humor in advertising is a strong and effective advertising strategy (Eisend, Citation2011; Walter et al., Citation2018). These results suggest that Poels and Dewitte are right in qualifying the elicitation of negative emotions in commercial advertising as underused.

This raises the question as to how negative emotions can lead to a positive attitude toward the ad. The answer is related to the second theoretical implication of our study: a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of narrative advertising. Kim et al. (Citation2017) have shown that narrative ads are more persuasive than factual ads. They ascribe this persuasive superiority to their hedonic value, that is, the extent to which the commercial provides the viewer with a pleasurable and entertaining experience. Research on media entertainment has identified two distinct types of entertainment: hedonic and eudaimonic entertainment (Oliver et al., Citation2012). Whereas the former is associated with the presence of positive emotions and the absence of negative ones, eudaimonic entertainment typically elicits both positive and negative emotions. The findings of this study reveal that narrative commercials can provide hedonic entertainment as well as eudaimonic entertainment depending on the stories they tell. Furthermore, eudaimonic entertainment providing commercials can lead to attitudes toward the ad that equal or even exceed those of hedonic entertainment providing commercials.

Wu and Dodoo (Citation2017) already suggested that there may be different types of narrative commercials providing eudaimonic entertainment. A third theoretical contribution in this respect is the distinction between joyfully and sadly moving commercials. This distinction was originally developed in film theory (Wassiliwizky et al., Citation2015) but appears relevant in distinguishing different types of moving narrative commercials as well. The results suggest that joyfully moving commercials, in which the positive events dominate the negative ones, provide a more balanced entertainment experience compared to the sadly moving commercials, leading to a more positive attitude toward the ad for the former commercials.

Finally, Kim et al. (Citation2017) argue that it is the entertainment experience that drives the persuasive effect of narrative ads. This experience can be measured by having people report the emotions they experienced but also by the physiological experiences that are typically associated with hedonic (e.g., relaxing, smiling) and eudaimonic (prickling tears, lump in throat) entertainment (Schubert et al., Citation2018). In this study, both indicators were measured. The regression analyses revealed that the self-reported physiological experiences were better predictors of the attitude toward the ad than the emotions, even if the latter were entered into the regression first. These findings suggest that the entertainment experience is indeed more important for the evaluation of the ad than the associated emotions.

Managerial implications

The findings of these studies have important managerial implications. When managers choose to employ narrative commercials to sell their products, the entertainment value of these commercials is key. The more entertaining the experience, the more likely that the attitude toward the ad will be positive. Self-report measures of physiological experiences that are associated with the entertainment experiences provide a relatively simple evaluation method that can explain a relatively large proportion of the attitude toward the ad.

This study also shows that managers do not have to restrict themselves to develop funny commercials. The attitude toward the ad for moving narrative commercials equaled, and in one case even exceeded that for humorous commercials. As the majority of the aired commercials provide hedonic entertainment (Pham et al., Citation2013), providing eudaimonic entertainment can make a commercial stand out from the clutter.

Limitations and future research

The ads used differed on various dimensions from each other. Apart from story-related characteristics, such as plot, characters, and setting, they also differ in length, music, and product category. Full experimental control would be desirable, but it is practically out of reach. The difference between humorous and moving narratives is by definition related to the events depicted. However, despite the differences between the ads in the two studies, the manipulation check items showed very similar and large effects: the humorous ads were considered the funniest ones, the joyfully moving ads the most heart-warming ones, and the sadly-moving ads the most gut-wrenching ones. This indicates that the ads differed from each other in the intended way.

A second limitation is the use of a within-participants design in which participants watched and responded to three ads. Given that commercials are usually clustered in a block, this is not an unrealistic setting. However, filling out the Geneva emotion wheel as well as the other items for the first commercials, may have influenced their responses to the later ones. In addition, one may question how accurate self-reports of emotions are. It would be interesting to tap into these experiences while participants are watching the ads using physiological measures (see, e.g., Sukalla et al., Citation2016). Such a set-up would lead to a more accurate assessment of the emotions and physiological experiences.

Third, as a measure of the ad’s effectiveness, only the attitude toward the ad was measured. Any difference in brand attitudes obtained, could have resulted from preexisting differences in attitudes toward the different brands and products. However, given the evidence for the importance of the attitude toward the ad for the attitude toward the brand (see, e.g., Eisend, Citation2011; Pham et al., Citation2013), these findings are relevant for the ad’s persuasiveness. Still, it would be preferable to compare humorous and (sadly or joyfully) moving commercials for the same brand and product.

An interesting question for future research would be to assess whether there are conditions under which the audience considers the use of moving ads as inappropriate. Being moved is evoked by representing morally valued practices or themes. As such, this type of ads is the exact opposite of shockvertising in which the audience is confronted with morally offensive images. Parry et al. (Citation2013) found that people considered the use of shockvertising more justified when used by non profit organizations than by profit organizations, based on a ‘the goal justifies the means’ reasoning. It would be interesting to see whether moving narratives evoke a similar response if people think that their appreciation for moral virtues is exploited in order to sell mundane products.

Conclusion

Whereas the impact of ad-evoked positive emotions on the attitude toward the ad has been well established, the role of negative emotions is much less understood. In this paper we show that narrative commercials can tell stories on prosocial behavior or family relations that elicit negative emotions next to positive ones. These commercials are equally, or even better liked than humorous commercials eliciting only positive emotions. This effect appears to be driven by the entertainment experience the commercial provides. As such, this study deepens our understanding of the role of negative emotions in advertising as well as of the mechanisms responsible for the persuasive impact of narrative commercials.

Ads used

Study 1.

Humorous ad – If Carlsberg Did Haircuts - Carlsberg The Barber ad

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXFiCVI6WEs

Joyfully moving ad – Guinness wheelchair basketball ad

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iiB3YNTcsAA

Sadly moving ad – Johnny Walker Dear brother ad

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gG4TfA3_u4I

Study 2.

Humorous ad – Always extra cheap Gamma ad

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jr6QuygDIWw

Joyfully moving ad – Nice at home Peijnenburg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PrroK54DPt4

Sadly moving ad– Monuta father and daughter

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Madelijn Strick, Julian Hanich, and Jos van Berkum as well as two reviewers for their insightful comments on previous versions of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 In addition, participants responded to the following items: “the ad made clear what is really important in life”, “the ad inspires me to do good things for other people”, and to what extent they considered the ad “nice”, “inspiring”, and “easy to understand”.

2 We ran the statistical analyses with all participants as well as without the response of the participants who had already seen a commercial before. The pattern of results was similar in both analyses therefore we reported the pattern including all participants. In the regression analyses, we included “having seen the commercial” as a predictor variable in the first step.

3 Eight participants reported having experienced an emotion other than the ones listed. In response to the humorous ad, two indicated to feel irritated, two felt surprised, one felt confused, and one stated “little fun”. One participant indicated to have felt “surprised” by the joyfully moving ad whereas one participant expressed “doubt” in response to the sadly moving ad.

4 For each commercial, we ran a Manova for all relevant dependent variables employing Seen commercial (yes, no) as the independent variable. For none of the commercials, this factor proved significant (respectively: p = .120, p = .392, and p = .493). In the regression analyses, we included “having seen the commercial” as a predictor variable in the first step.

5 Six participants reported having experienced an emotion other than the ones listed. In response to the humorous ad, two participants felt irritated and one felt skeptical. In response to the joyfully moving ad, one participant felt bored. In response to the sadly moving ad, one participant felt irritated and another participant felt tense.

6 We analyzed the two studies as a single experiment, with Ad type (humorous, joyfully moving, sadly moving) as a within-participants factor, and study (1, 2) as a between-participants factor. We found a main effect of Type of narrative ad (F (2, 188) = 7.97, p = .004, ƞ2 = .078); post hoc comparisons using Bonferroni correction reveal that the joyfully moving ad is appreciated more highly than the humorous (p = .001) and the sadly moving ads (p = .044). The latter two did not differ from each other. The interaction between Ad type and Study was not significant (F (1, 188) = 2.307, p = .102). The difference in the results between the two studies thus appears to be more a matter of degree than of a different pattern.

References

- Aaker, D. A., Stayman, D. M., & Hagerty, M. (1986). Warmth in advertising: Measurement, impact, and sequence effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(4), 365–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/208524

- Bae, M. (2021). The effect of sequential structure in charity advertising on Message elaboration and donation intention: The mediating role of empathy. Journal of Promotion Management, 27(1), 177–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2020.1809597

- Batra, R., & Ray, M. L. (1986). Affective responses mediating acceptance of advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(2), 234–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209063

- Bennett, R. (2015). Individual characteristics and the arousal of mixed emotions: consequences for the effectiveness of charity fundraising advertisements. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 20(2), 188–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1500

- Brown, S., Homer, P., & Inman, J. (1998). A meta-analysis of relationships between ad-evoked feelings and advertising responses. Journal of Marketing Research, 35(1), 114–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379803500111

- Burke, M. C., & Edell, J. A. (1989). The impact of feelings on ad-based affect and cognition. Journal of Marketing Research, 26(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378902600106

- Cova, F., & Deonna, J. (2014). Being moved. Philosophical Studies, 169(3), 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-013-0192-9

- Edell, J. A., & Burke, M. C. (1987). The power of feelings in understanding advertising effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(3), 421–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209124

- Eisend, M. (2011). How humor in advertising works: A meta-analytic test of alternative models. Marketing Letters, 22(2), 115–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-010-9116-z

- Escalas, J. E. (1998). Advertising narratives: What are they and how do they work? In B. B. Stern (Ed.), Representing consumers: Voices, views, and visions (pp. 267–289). Routledge.

- Gong, Z., & Cummins, R. G. (2020). Redefining rational and emotional advertising appeals as available processing resources: Toward an information processing perspective. Journal of Promotion Management, 26(2), 277–299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2019.1699631

- Holbrook, M. B., & Batra, R. (1987). Assessing the role of emotions as mediators of consumer responses to advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(3), 404–420. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209123

- Hong, J., & Lee, A. Y. (2010). Feeling mixed but not torn: The moderating role of construal level in mixed emotions appeals. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(3), 456–472. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/653492

- Janssens, W., De Pelsmacker, P., & Weverbergh, M. (2007). The effect of mixed emotions in advertising: The moderating role of discomfort with ambiguity. In C. Taylor & D. Lee (Eds.), Cross-cultural buyer behavior (advances in international marketing) (Vol. 18, pp. 63–92). Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-7979(06)18003-5

- Kim, E., Ratneshwar, S., & Thorson, E. (2017). Why narrative ads work: An integrated process explanation. Journal of Advertising, 46(2), 283–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1268984

- Konečini, V. J. (2005). The aesthetic trinity: Awe, being Moved, thrills. Bulletin of Psychology and the Arts, 5(2), 27–44.

- Menninghaus, W., Wagner, V., Hanich, J., Wassiliwizky, E., Kuehnast, M., & Jacobsen, T. (2015). Towards a psychological construct of being moved. PLoS One, 10(6), e0128451. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128451.

- Oliver, M. B., Hartmann, T., & Woolley, J. K. (2012). Elevation in response to entertainment portrayals of moral virtue. Human Communication Research, 38(3), 360–378. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2012.01427.x

- Parry, S., Jones, R., Stern, P., & Robinson, M. (2013). Shockvertising’: An exploratory investigation into attitudinal variations and emotional reactions to shock advertising. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 12(2), 112–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1430

- Pham, M. T., Geuens, M., & De Pelsmacker, P. (2013). The influence of ad-evoked feelings on brand evaluations: Empirical generalizations from consumer responses to more than 1000 TV commercials. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 30(4), 383–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2013.04.004

- Poels, K., & Dewitte, S. (2019). The role of emotions in advertising: A call to action. Journal of Advertising, 48(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1579688

- Sacharin, V., Schlegel, K., & Scherer, K. R. (2012). Geneva emotion wheel rating study. University of Geneva, Swiss Center for Affective Sciences.

- Schubert, T. W., Zickfeld, J. H., Seibt, B., & Fiske, A. P. (2018). Moment-to-moment changes in feeling moved match changes in closeness, tears, goosebumps, and warmth: Time series analyses. Cognition & Emotion, 32(1), 174–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1268998

- Sukalla, F., Bilandzic, H., Bolls, P., & Busselle, R. (2016). Embodiment of narrative engagement. Journal of Media Psychology, 28(4), 175–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000153

- Walter, N., Cody, M. J., Xu, L. Z., & Murphy, S. T. (2018). A Priest, a rabbi, and a minister walk into a bar: A meta-analysis of humor effects on persuasion. Human Communication Research, 44(4), 343–373. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqy005

- Wassiliwizky, E., Wagner, V., Jacobsen, T., & Menninghaus, W. (2015). Art-elicited chills indicate states of being moved. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(4), 405–416. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000023

- Williams, P., & Aaker, J. L. (2002). Can mixed emotions peacefully co-exist? Journal of Consumer Research, 28(4), 636–649. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/338206

- Wu, L. (2019). Understanding how the message appeal of moral beauty influences advertising effectiveness under mortality salience. Journal of Marketing Communications, 25(6), 586–606. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2018.1461125

- Wu, L., & Dodoo, N. A. (2017). Reaching goals and doing good: Exploring consumer responses to meaningful advertisements. Journal of Promotion Management, 23(4), 592–613. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2017.1297978

- Yelkur, R., Tomkovick, C., Hofer, A., & Rozumalski, D. (2013). Super Bowl ad likeability: Enduring and emerging predictors. Journal of Marketing Communications, 19(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2011.581302

Appendix 1.

Geneva emotion wheel

Appendix 2.

Tables for regression analyses

Study 1. Humorous Ad

Study 1. Joyfully Moving Ad

Study 1. Sadly Moving Ad

Study 2. Humorous Ad

Study 2. Joyfully Moving Ad

Study 2. Sadly Moving Ad