Abstract

Brand communication via social media influencers (SMIs) has become a vital constituent of firms’ brand communication strategy. The current study assesses the mediated (via brand content engagement) and direct influence of SMI attributes and brand content esthetics on followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand and brand-link click behavior. The current study analyzed the data from an online survey of 300 followers of the top 40 Instafamous Pakistani SMIs to test the model and hypotheses. The results show that brand content engagement mediates between SMI attributes (i.e. trustworthiness, expertise, and similarity), brand content esthetics, and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. SMI’s credibility directly influences followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. Furthermore, brand content engagement has an attitudinal and direct influence on followers’ brand-link click behavior. These findings will help practitioners understand how SMI and SMI-generated brand content influence followers’ brand-link click behavior.

Introduction

Social media have become a vital mode of interactivity. Firms use it to carry out business activities such as promoting brands (Fitriati et al., Citation2023). Specifically, Instagram has become a key channel for brand communication (Hazari & Sethna, Citation2023), which is the focus of the current study. Marketers use different strategies to promote brands via Instagram. One such strategy is using social media influencers (SMIs) for brand communication (Voorveld, Citation2019; Vrontis et al., Citation2021). SMIs start as ordinary users, but over time, they develop a network of sizable followers, improve their expertise, and generate sophisticated content (e.g. stories, visuals, videos) to influence their followers (De Veirman et al., Citation2017). Recent research (e.g. Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Wiedmann & von Mettenheim, Citation2021) indicates several desired effects of brand communication via SMI, such as improved brand awareness, image, and purchase intentions.

Considering the never-ending importance of attributes of the message and its source in communication effectiveness, several studies (e.g. AlFarraj et al., Citation2021; Khan & Saima, Citation2021; Wiedmann & von Mettenheim, Citation2021) examined the influence of SMI attributes on brand communication effectiveness. Similarly, some studies (e.g. Lou & Yuan, Citation2019; Khan & Saima, Citation2021) assessed the influence of SMI-generated informative and entertaining content on brand communication effectiveness. Marketers apply SMI marketing to engage users with the brand (Delbaere et al., Citation2021). Brand engagement is a firm’s key goal and an indicator of its effective social media marketing strategy (Trunfio & Rossi, Citation2021). The influence of SMI and SMI-generated content attributes on followers’ endorsed brand engagement has scarcely been investigated. Importantly, engagement has previously been treated as an antecedent or outcome of SMI brand endorsement (Vrontis et al., Citation2021). Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández (Citation2019) suggest that researchers should treat followers’ brand engagement as a mediator in the SMI marketing context. Rare studies have assessed the mediating role of SMI-generated brand content engagement between perceived attributes of SMIs and brand content and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand and brand link click behavior. The mediating analysis provides a deeper insight into how variables relate and uncovers the causal mechanism by which a predictor contributes to an outcome (Preacher, Citation2015).

Besides mediation by engagement, literature (e.g. Lin et al., Citation2021) indicates that SMI and content attributes can directly influence followers’ endorsed brand attitude. Such a relationship has scarcely been investigated in the SMI marketing context. Notably, researchers rarely conceptualized mediated (via engagement) and direct influence of SMI and SMI-generated content attributes on followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand in a single model. Assessment of this kind of dual relationship is warranted because mediation and direct effect generally coexist (Zhao et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, researchers have mainly focused on followers’ endorsed brand attitude. A positive brand attitude does not indicate the overall value of online marketing communication efforts unless it leads to click-through behavior (Briggs & Hollis, Citation1997). Does followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand trigger their brand-link click behavior on Instagram? This question has rarely been addressed. On Instagram, two types of producer-generated brand links appear (i.e. sponsored content in the user feed and content in the brand’s account) (De Jans et al., Citation2020). Clicking these links can redirect followers to the brand’s external website, where they take further actions, such as purchasing the endorsed brand or interacting with the seller (Chen et al., Citation2021).

In addition, SMI marketing research (e.g. AlFarraj et al., Citation2021; Khan & Saima, Citation2021; Wiedmann & von Mettenheim, Citation2021) treated attractiveness as a dimension of credibility. Source credibility and attractiveness are conceptually distinct constructs and should be treated independently. Source credibility influences consumers’ brand attitudes and behavior via the internalization process. Internalization indicates that consumers accept a marketing message as valid and valuable based on their inferences about its source as trustworthy and expert (Chebat et al., Citation2007). It relates to the content and the quality of communication. Conversely, source attractiveness influences user attitudes and behavior via identification (Kelman, Citation1958). Identification indicates similarities between the message source and its receivers. In the identification process, consumers accept the marketing message based on their inferences about the physical attractiveness of its source and shared attributes (e.g. same lifestyle and interests) and values (e.g. same cultural background) (Chebat et al., Citation2007). It relates to the admiration of the message source and the aspiration to identify with them (Schimmelpfennig & Hunt, Citation2020). Furthermore, prior Instagram studies (e.g. Khan & Saima, Citation2021; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019) primarily focused on informative and entertaining attributes of SMI-generated brand content. The prime focus of Instagram is on esthetically rich visual brand content (Masdari & Sarvari, Citation2021). Research (e.g. Yang et al., Citation2021) shows that SMIs use esthetic appeal to attract and influence their followers on Instagram. A few studies have assessed the influence of SMI-generated brand content esthetics on followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand while using brand content engagement as a mediator. Moreover, scarce studies have applied fundamental communication models such as McGuire’s (Citation1969, Citation1978) persuasive communication model in the SMI marketing context (Voorveld, Citation2019).

To address the abovementioned gaps in the SMI marketing literature, the current study aims to assess the mediated (via brand content engagement) and direct influence of SMI credibility, attractiveness, and brand content esthetics on followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand and brand-link click behavior. SMI credibility and attractiveness attributes are re-conceptualized using Hovland et al. (Citation1953) and McGuire’s (Citation1985) source effect models. McGuire’s (Citation1969, Citation1978) persuasive communication model is applied to rationalize how SMI’s attributes and brand content esthetics influence followers’ brand content engagement and attitude and trigger their brand-link click behavior on Instagram. Voorveld (Citation2019) suggested that researchers should employ a persuasive communication model in the SMI-marketing context because it includes all the fundamental elements of effective communication, such as source, message-content, channel, audience, and destination variables (Aghazadeh et al., Citation2022). The structure of the paper consists of conceptualization of SMI attributes, brand content esthetics, engagement, attitude, brand-link click behavior, research model and hypotheses development, research methodology, discussion, conclusion, contribution, implications, limitations, and future research agenda.

SMI attributes

The message source is a vital input variable of the persuasive communication model (McGuire, Citation1969, Citation1978). Its impact on brand communication effectiveness is determined in terms of perceived attributes that describe and distinguish a source (Mulilis, Citation1998; Petty & Wegener, Citation1998). Generally, source credibility (Hovland et al., Citation1953) and attractiveness (McGuire, Citation1985) models are used to assess brand communication effectiveness. Credibility and attractiveness capture distinct attributes of the message source and influence consumer attitudes and behavior through different processes. Credibility is related to the content and the quality of the message communicated by the source (Kelman, Citation1958). It brings a change in consumer attitude and behavior through the internalization process. Internalization refers to the degree to which consumers accept an endorsed message as authentic and valuable based on their perception of the source or endorser as trustworthy and expert (Chebat et al., Citation2007). Attractiveness is related to the admiration of the message source. It indicates the receiver’s aspiration to resemble or identify with the message source (Schimmelpfennig & Hunt, Citation2020). Source attractiveness affects consumer attitude and behavior through the identification process (Kelman, Citation1958). In the identification process, consumers accept the marketing messages based on their inferences about the physical attractiveness of the source and the similarities between them (Chebat et al., Citation2007). The following text presents dimensional structures of source credibility and attractiveness models and their application in the SMI marketing context.

SMI credibility

The source credibility is a crucial factor that substantially affects the effectiveness of brand endorsement via SMIs (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). It describes the communicator’s positive characteristics, which improves message acceptance (Hovland et al., Citation1953). Credibility refers to the perceived ability of a source to provide correct and honest information. It has two dimensions: trustworthiness and expertise (Ohanian, Citation1990). Research (e.g. Wiedmann & von Mettenheim, Citation2021) identifies trustworthiness and expertise as vital attributes of SMIs. Trustworthiness is the audience’s perception of an endorser as honest, reliable, dependable, and believable who intends to convey valid information (Hovland et al., Citation1953). Since SMIs often endorse different brands by showing them using themselves and explaining their advantages and disadvantages in their posts. Thus, their followers perceive them as trustworthy (Kim & Kim, Citation2022). Expertise refers to the audience’s perception of a communicator as competent (Ki et al., Citation2020), knowledgeable, experienced, and an authentic source of information (Hovland et al., Citation1953). Since SMIs create specific content in niche areas (e.g. fashion, beauty, fitness, and food) and are perceived as experts in their particular fields by their followers (Erz & Christensen, Citation2018). The perceived trustworthiness and expertise of SMIs have several positive consequences for influencer marketing. For instance, perceived trustworthiness and expertise positively change followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand (Dangi & Dhun, Citation2023).

SMI attractiveness

Attractiveness is an important attribute that followers associate with SMIs (AlFarraj et al., Citation2021; Wiedmann & von Mettenheim, Citation2021). Attractiveness refers to the audience’s perception of an endorser as appealing (Kok Wei & Li, Citation2013). The source attractiveness model by McGuire (Citation1985) proposes four dimensions of source attractiveness (i.e. familiarity, likability, similarity, and physical attractiveness). It claims that the effectiveness of a message depends on these four characteristics of an endorser. Based on McGuire’s source effect model, the current proposes physical attractiveness, similarity, and likeability as the dimensions of SMI attractiveness. Physical attractiveness describes SMI’s appearance-related perceptions of followers, such as attractive, good-looking, stylish, sexy, beautiful, and elegant (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). It positively affects brand communication via SMIs (Morton, Citation2020). Similarity describes the perceived resemblance between SMIs and their followers, such as sharing similar tastes, preferences, interests, lifestyles, and values (Ki et al., Citation2020). The similarity between the source and receiver is crucial for communication to be persuasive (McCroskey et al., Citation2006). Contrary to prior research, the current study treats likeability as a distinct construct from physical attractiveness (De Veirman et al., Citation2017; Pulles & Hartman, Citation2017). It describes followers’ affection for SMIs based on their personality and behavioral traits, such as pleasant, warm, polite, nice, likable, and friendly (Pulles & Hartman, Citation2017).

Brand content esthetics

The second crucial independent variable of the persuasive communication model is the message content (McGuire, Citation1969, Citation1978). Like the source, its impact on destination variables is evaluated in terms of perceived attributes (Mulilis, Citation1998). Prior studies (e.g. Lou & Yuan, Citation2019) indicate brand content attributes as vital predictors of SMI-endorsed brand communication effectiveness. Specifically, esthetics is an integral attribute of visual brand content (i.e. photos and video clips) (Masdari & Sarvari, Citation2021) appearing on Instagram. In marketing, esthetics is defined as an appeal based on the principles of design (e.g. novelty, proportion, balance, unity, contrast, and smoothness) (Hagtvedt, Citation2022) or elements of design (e.g. light, color, angle of view, focus, and line). These principles and elements make content esthetically pleasing or enhance the esthetic value of content (Van der Heijden, Citation2004). Esthetics stems from sensory perception involving an experience that is fascinating, pleasing, and meaningful. It often revolves around beauty (Hagtvedt, Citation2022). Goldman (Citation2001) defined esthetics as sensory pleasure and delight. Following this definition, the current study views perceived brand content esthetics as sensory pleasure, which followers experience when exposed to SMI-generated attractive, lovely, fascinating, and beautiful brand content (i.e. pictures and video clips) on Instagram. Followers receive esthetic value from SMI-generated brand content on Instagram, which is the sensory pleasure from their interactions with attractive visual brand content (Bashir et al., Citation2018).

Followers’ brand content engagement

Followers’ brand engagement is a crucial indicator of successful SMI marketing. It determines the influence of SMI attributes and brand-related posts on followers (Arora et al., Citation2019). Brand engagement on social media (e.g. Instagram) was previously (See Hollebeek et al., Citation2014) claimed to be cognitive, affective, or behavioral. Cognitive engagement reflects brand-related thinking. In contrast, affective engagement mirrors brand-related emotions (Delbaere et al., Citation2021). The behavioral dimension of engagement reflects actual brand-related actions on social media (Hollebeek et al., Citation2014). However, recent research (e.g. Obilo et al., Citation2021) suggested that social media brand engagement solely consists of user behaviors such as generating, viewing, reading, liking, commenting, and sharing content. The current study, therefore, focuses on the followers’ behavioral brand engagement. Furthermore, behavioral engagement corresponds to Instagram features (e.g. Like button, commenting, and sharing options). Importantly, practitioners and researchers use these features to measure followers’ responses to SMI-generated content (Arora et al., Citation2019).

Muntinga et al. (Citation2011) classified social media behavioral brand engagement into consumption, contribution, and creation factors. Based on this classification, Tsai and Men (Citation2013) presented two dimensions (i.e. consuming and contributing) of users’ brand engagement on social media. Consuming behavior represents activities such as watching brand-related photos and videos, reading comments and reviews, and liking the brand content. In contrast, contributing behavior refers to follower activities, such as commenting and sharing brand content with other users (Triantafillidou & Siomkos, Citation2018). The current study follows the Tsai and Men (Citation2013) conceptualization of users’ social media brand engagement because it is consistent with fundamental Instagram features (e.g. Like, comment, and share options). Furthermore, liking, commenting, and sharing are the common engagement behaviors that users exhibit across social media platforms (Trunfio & Rossi, Citation2021). Viewing and liking SMI’s posts requires relatively lesser effort, thus belonging to the consumption dimension of followers’ brand engagement. Conversely, commenting and sharing the SMI’s posts requires more user active participation, thus belonging to the contribution dimension of the followers’ brand engagement (Triantafillidou & Siomkos, Citation2018).

Attitude toward the endorsed brand

Assessing followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brands is crucial because it plays the mediation in the SMI marketing context (Torres et al., Citation2019; Trivedi & Sama, Citation2020). Two dominant perspectives exist as far as the conceptualization of attitude is concerned: traditional and contemporary. The traditionalists who promote the tripartite theory recognize cognition, affect, and behavior as components of brand attitude (Fabrigar et al., Citation2005). Cognition is a thought or belief-based evaluation of the brand rooted in the attributes of an object or stimulus (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). Affect is brand-related emotions and feelings triggered by the motivational response (McGuire, Citation1969). The behavioral component of attitude describes a person’s overt reaction to the brand (Fabrigar et al., Citation2005). Unlike traditionalists, contemporary theorists (e.g. Spears & Singh, Citation2004) define attitude as a general evaluative summary of the information about a brand derived from the beliefs, emotions, and behaviors expressed partly with some favor or disfavor. The contemporary perspective of attitude presents a holistic view of attitude. In agreement with contemporary theorists, the current study defines followers’ attitude toward SMI-endorsed brands as a one-dimensional general evaluative summary stimulating them to click the company-owned and sponsored brand links on Instagram.

Brand link click behavior

Firms use a two-tier Instagram brand communication strategy (Jin & Muqaddam, Citation2019). One, they publish brand content (photos and videos) in Instagram user feeds labeled sponsored brand content. For sponsored content, firms pay Instagram to promote the brands to specific target groups. Furthermore, brand content (photos and videos) also appears in firms’ Instagram brand accounts, known as owned content. Two, firms promote their brands through SMIs (De Jans et al., Citation2020). SMIs use different strategies to endorse brands on Instagram. For instance, they share brand-related images and short videos with their followers on Instagram or show using those brands themselves in photos and videos. For example, SMIs share images with their followers on Instagram showing them holding trendy brands such as Gucci handbags, wearing Nike sneakers, and so on (Kim et al., Citation2021). The current study presumes that followers seek the sponsored and brand-owned links of SMI-endorsed brands on Instagram and click on them, or whenever they encounter those links while surfing Instagram, they click on them. Clicking brand links (e.g. sponsored ads) on Instagram directs followers to its external website, where they take further actions, such as purchasing the endorsed brand or interacting with the seller (Chen et al., Citation2021).

Research model and hypotheses development

In recent years, SMI-brand endorsement has become a crucial component of social media marketing communication strategy (Vrontis et al., Citation2021). The current study applies McGuire’s (Citation1969, Citation1978) persuasive communication model to explain the mediated (via brand content engagement) and direct influence of SMI credibility, attractiveness, and brand content esthetics on followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand and brand-link click behavior. This model identifies five independent variables: source, message, channel, receiver, destination, and four output variables: reception (i.e. attention and comprehension), yielding, attitude change, retention, and action (McGuire, Citation1969). These variables are the fundamental elements of persuasive communication (Aghazadeh et al., Citation2022). A source is a person (e.g. SMI) that sends the message to a targeted audience (e.g. followers). A message is an argument that a source sends to a targeted audience. Source and message content attributes influence the targeted audience. A channel like Instagram is a medium through which a brand message is delivered (Mulilis, Citation1998) to the targeted audience. Destination variables include attitude and behavior, which persuasive communication intends to influence (Aghazadeh et al., Citation2022).

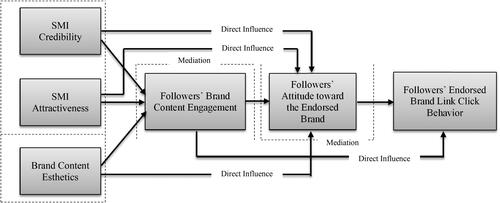

Independent variables influence destination variables through internal mediating processes: reception and yielding (McGuire, Citation1969). Whether the message sent by the source through the channel was received and yielded desired results are usually measured in terms of attitude change (McGuire, Citation1985) and behavior (McGuire, Citation1969). Researchers use cognitive, affective, or behavioral processes as mediators between independent and destination variables (Petty & Wegener, Citation1998). The current study proposes the behavioral process as a mediator between SMI credibility, attractiveness, brand content esthetics, and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. Followers’ engagement with SMI-generated brand content represents the behavioral process (). Prior SMI marketing research (e.g. Jiménez-Castillo & Sánchez-Fernández, Citation2019) supports the mediating role of user engagement.

Besides mediation, independent variables can influence attitude through different processes (Petty & Wegener, Citation1998). The current study proposes that besides the mediating role of brand content engagement, SMI credibility, attractiveness, and brand content esthetics can directly influence followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand (). Recent studies (e.g. Torres et al., Citation2019; Trivedi & Sama, Citation2020) recognize the direct influence of SMI attributes on followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. Similarly, Jin and Muqaddam (Citation2019) found a direct relationship between brand content attributes and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. Furthermore, the current study proposes that brand content engagement has an attitudinal and direct influence on followers’ brand-link click behavior on Instagram (). Attitude is not only a key destination variable in persuasive communication (See Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975; McGuire, Citation1969, Citation1978) but also a well-established mediator. Calder et al. (Citation2009) found that online engagement directly affects ad–click behavior. Followers click on brand-related posts to learn more about the endorsed brand (Gavilanes et al., Citation2018). On Instagram, company-owned accounts and sponsored content links contain brand information (De Jans et al., Citation2020). Clicking these brand links on Instagram redirects followers to the external website of the brand, where they take further actions such as purchasing the endorsed brand or directly interacting with the seller (Chen et al., Citation2021). Based on the abovementioned argument, the following text presents specific hypotheses.

Mediating role of brand content engagement

Consumer social media brand engagement signals a firm’s successful online branding strategy (Trunfio & Rossi, Citation2021). Firms use diverse tactics to engage consumers on social media. One such tactic is using SMIs to endorse the brands and engage consumers on social media like Instagram. Grounded on McGuire’s (Citation1969, Citation1978) persuasive communication model, the current study proposes that followers’ brand content engagement on SMI’s Instagram account mediates between SMI attributes (i.e. credibility and attractiveness) and their attitude toward the endorsed brand. Similarly, it mediates between brand content esthetics and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand (). According to the persuasive communication model, source/endorser and message attributes cause a change in brand attitude (McGuire, Citation1969). Brand attitude is the key destination variable used to measure the impact of persuasive communication on the targeted audience (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). However, scholars (e.g. Petty & Wegener, Citation1998) proposed that engagement processes could mediate between input and destination variables identified in the persuasive communication model. This proposition supports the inclusion of followers’ brand content engagement in the current context. Besides this theoretical backing, recent research also supports the current postulation. For instance, AlFarraj et al. (Citation2021) found that followers’ social media brand engagement mediates between SMI attributes and purchase intentions. Similarly, it mediates between brand content attributes (e.g. esthetics, see Kusumasondjaja, Citation2020) and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand (Raajpoot & Ghilni-Wage, Citation2019). Based on the above argument, the current study offers the following hypotheses:

H1a. Followers’ brand content engagement on SMI’s Instagram account mediates the relationship between SMI’s credibility and their attitude toward the endorsed brand.

H1b. Followers’ brand content engagement on SMI’s Instagram account mediates the relationship between SMI’s attractiveness and their attitude toward the endorsed brand.

H1c. Followers’ brand content engagement on SMI’s Instagram account mediates the relationship between brand content esthetics and their attitude toward the endorsed brand.

Direct influence of SMI attributes

SMI marketing brings positive changes in followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019), which is the main objective of the firm’s brand communication efforts (Rossiter & Percy, Citation1985). This positive change in followers’ brand attitude can occur through multiple mechanisms (e.g. via mediators or directly) (Petty & Wegener, Citation1998). Thus, the current study proposes that SMI’s credibility and attractiveness factors can directly affect followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand (). This postulation conforms to the assumption that the message source identified in McGuire’s (Citation1969, Citation1978) persuasive communication model can directly influence the targeted audience’s brand attitude (Petty & Wegener, Citation1998). Recent SMI marketing research supports it as well. For instance, Lin et al. (Citation2021) identified a direct association between SMI attributes (e.g. trustworthiness, expertise, and attractiveness) and users’ brand attitude. In light of this argument, the current study offers the following hypotheses:

H2a. SMI’s credibility directly influences followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand.

H2b. SMI’s attractiveness directly influences followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand.

Direct influence of brand content esthetics

Message content is crucial for communication to be persuasive (McGuire, Citation1969, Citation1978). Prior research (e.g. Freberg et al., Citation2011) shows that SMI-generated content shapes their followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. SMIs generate visually rich brand content (i.e. pictures and videos) on Instagram. Through repeated exposure, their followers learn the value of that content, which ultimately influences their attitude toward the endorsed brand (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). Jin and Muqaddam (Citation2019) found that the perceived value of social media content directly influences user brand attitude. The current study postulates that brand content esthetics directly influence followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand (). Esthetics is a fundamental attribute of the visual content of Instagram (Masdari & Sarvari, Citation2021). SMIs generate esthetically pleasing brand content on Instagram (Yang et al., Citation2021). When followers interact with that content, they receive sensory pleasure (value) (Bashir et al., Citation2018), which influences their endorsed brand attitude (Colliander & Marder, Citation2018). In light of the above argument, the current study offers the following hypothesis:

H2c. Brand content esthetics directly influence followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand.

Mediating role of attitude toward the endorsed brands

Brand attitude is the central destination variable in McGuire’s (Citation1969, Citation1978) persuasion communication model (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). Besides being influenced by various input variables (e.g. source and message content), brand attitude plays mediation in the SMI marketing context (Torres et al., Citation2019). For instance, brand attitude mediates between SMI attributes and purchase intentions (Trivedi & Sama, Citation2020). The current study postulates that attitude toward the endorsed brand mediates between followers’ brand content engagement and their Instagram brand-link (owned and sponsored) click behavior (). This postulation is supported by Raajpoot and Ghilni-Wage (Citation2019), who found that brand content engagement on social media affects consumers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand, which consequently triggers their brand-related behaviors. In light of the above argument, the current study offers the following hypothesis:

H3. Attitude toward the endorsed brand mediates the relationship between brand content engagement and followers’ brand-link click behavior.

Direct influence of brand content engagement

Firms focus on social media engagement because it drives consumers’ online brand-related behaviors (Jiménez-Castillo & Sánchez-Fernández, Citation2019). The current study proposes that followers’ brand content engagement triggered by SMI’s credibility, attractiveness, and brand content esthetics directly influences their behavior to click endorsed brand links on Instagram (). In line with this postulation, researchers (e.g. Lee et al., Citation2018) identified that consumers’ brand content engagement (i.e. liking, commenting, and sharing) on social media improves ad-click-through behavior. Ad-click-through behavior signals the effectiveness of SMI-brand endorsement. When followers click on endorsed brand-related content links (company owned and sponsored) on Instagram, it redirects them to the brand’s external Website, where they can take further actions related to the endorsed brand, such as buying it (Chen et al., Citation2021; De Jans et al., Citation2020). In light of the above argument, the current study offers the following hypothesis:

H4. Followers’ brand content engagement directly influences their brand-link click behavior.

Research design and methodology

Data were collected from 300 followers of Pakistani Top 40 Instafamous SMIs. These SMIs promote different brands ranging from personal wear (e.g. clothing, handbags, footwear, makeup, jewelry, wristwatches) to electronic devices (e.g. smartphones, Laptops) by generating visual brand content (photos and video clips) on their Instagram accounts. Instagram is the key social media platform for endorsing brands (Hazari & Sethna, Citation2023). Pakistan is an emerging digital economy with 82.90 million internet users. In early 2022, Instagram users in Pakistan were 13.75 million (Kemp, Citation2022).

In the current study, active followers who had followed SMIs on Instagram for more than six months were sampled using purposive sampling. Purposive sampling helps to choose those individuals who are experienced with the phenomenon under investigation and can provide rich information about it (Cresswell & Plano Clark, Citation2011). After getting consent, researchers sent an online questionnaire link to 335 targeted followers. A few of them did not respond. Furthermore, some questionnaires received contained incomplete information. A total of 35 questionnaires were excluded. Sample size (n) 300 was decided based on the guidelines given in the literature. Researchers generally apply these guidelines in the case of nonprobability sampling techniques (e.g. purposive sampling). Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2007) recommended that n = 300 is good if the study contains factor analysis. According to Comrey and Lee (Citation1992), n = 300 is excellent for structural equation modeling. The current study included both factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Thus, n = 300 met the requirements of the study. Sampled followers of SMIs consisted of 69.3% male and 30.7% female. This substantial difference in the gender percentage of the sample size is due to cultural context. Pakistan is a masculine country where more social media users are male than female. In addition, the targeted followers’ ages ranged from 18 to 30 years. This age group is in line with the demographic structure of the Pakistani population. Around 52% of the Pakistani population falls in this age group and is active on social media (Jamal, Citation2020).

Construct measurement source and assessment

The SMI credibility and attractiveness were measured using 13-item and 17-item inventories from the studies (i.e. De Veirman et al., Citation2017; Kim & Kim, Citation2021) respectively. The brand content esthetics was measured using a seven-item inventory from the studies (i.e. Bashir et al., Citation2018; Lavie & Tractinsky, Citation2004). The brand content engagement was measured using an 11-item inventory from Tsai and Men (Citation2013). Seven items from Kim and Kim (Citation2021) were adapted to measure attitude toward the endorsed brand. The brand link-click behavior was measured using two items adapted from Mir (Citation2018). The content validity of measures was ensured using a relevant literature review. Responses related to SMI credibility, attractiveness, brand content esthetics, and attitude toward the endorsed brand were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale varying from strongly disagree (1) – strongly agree (5). Responses related to followers’ brand content engagement and brand-link click behavior were recorded using a scale containing four options: (1) very often, (2) often, (3) sometimes, and (4) never.

The principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on data to identify construct dimensions and reduce their measures into meaningful scales. Construct factors were determined using Eigenvalue > 1.00 criterion. Factor items were selected using Loadings > .60 and commonalities >.40. The PCA with a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) = 0.851, p = .000, and total variance explained = 69.929 extracted two factors of SMI credibility: trustworthiness (Factor1) and expertise (Factor2). With Eigenvalue = 3.999, trustworthiness explained a 37.415% variance. Similarly, with Eigenvalue = 1.595, expertise explained a 32.514% variance. Based on the abovementioned criteria, the PCA validated four items for each factor of SMI credibility. The PCA with a KMO = 0.821, p = .000, and total variance explained = 72.295 extracted two factors of SMI acttractiveness: physical attractiveness (Factor1) and similarity (Factor2). With Eigenvalue = 3.061, physical attractiveness explained a 37.215% variance. Likewise, with Eigenvalue = 2.722, similarity explained a 35.081% variance. Based on the abovementioned criteria, the PCA validated four items for each factor of SMI attractiveness.

The PCA with a KMO = 0.834, p = .000, and percentage of variance explained = 74.609 extracted one factor of brand content esthetics. With Eigenvalue = 2.984, the PCA validated four items of brand content esthetics. The PCA with a KMO = .707, p = .000, and total variance explained = 79.149 extracted two factors of brand content engagement: consuming (Factor1) and contributing (Factor2). With Eigenvalue = 2.842, consuming explained a 44.554% variance. Similarly, with Eigenvalue =1.115, explained a 34.595% variance. The PCA validated three items of the consuming factor. It validated two items of contributing factor. The PCA with a KMO = 0.869, p = .000, and percentage of variance explained = 71.201 extracted one factor of followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. With Eigenvalue = 3.560, the PCA validated four items of followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. The PCA with a KMO = .500, p = .000, and percentage of variance explained = 85.152 extracted one factor of brand-link click behavior. With Eigenvalue = 1.703, the PCA validated two items of brand-link click behavior. shows the construct measures, factor loading, and reliability (Alpha).

Table 1. Constructs, measurement items, factors, loading and reliability.

The confirmatory factors analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the good fit and validity of the construct measurement models. SMI’s credibility two-dimensional measurement model with χ2 = 23.913, df =19, p = 0.200, and χ2/df = 1.259 < 3) fitted the data. A low χ2 with an insignificant P typically greater than .05 indicates that the model fits the data. Similarly, χ2/df ratio < 3 indicates the goodness of fit. To ascertain that two dimensions of SMI credibility were not produced by common method bias, which is expected to occur in the case of self-reported survey data (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003), an alternate one-dimensional model of SMI’s credibility was tested. With a χ2 = 357.837, df = 20, p = 0.000 < 0.001, and χ2/df = 17.892, GFI= .705, NFI= .725, IFI= .736, TLI = .628, CFA = .734, and RMSEA = .238, one-dimensional model of SMI’s credibility revealed a bad fit, thus established that common method bias was not a cause of concern. With a χ2 =29.044, df = 19, p = .065 > 0.05, and χ2/df = 1.529 < 3, the two-dimensional measurement model of SMI’s attractiveness fitted the data. An alternate, SMI attractiveness one-dimensional model with a χ2 = 773.815, df = 20, p = .000 < .001 and χ2/df = 38.691, GFI= .566, NFI= .438, IFI= .445, TLI = .218, CFA = .441, and RMSEA = .355 revealed a bad fit, thus established that common method bias was not a cause of concern. With a χ2 =1.138, df = 2, p = .566 > .05, and χ2/df = .569 < 3, the measurement model of brand content esthetics perfectly fitted the data, thus establishing its unidimensionality. With a χ2 = 5.236, df = 4, p = .264 > .05, and χ2/df = 1.309 < 3, the two-dimensional measurement model of followers’ brand content engagement perfectly fitted the data. On a one-dimensional model with a χ2 = 159.208, df = 5, p = .000 < .001, and χ2/df = 31.842, GFI= .852, NFI= .757, IFI= .763, TLI = .523, CFA = .761, and RMSEA = .321 it produced a bad fit, thus confirmed that common method bias was not a cause of concern. With a χ2 = 12.708, df = 5, and p = .026 < .05, the measurement model of followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand indicated a bad fit. Yet, with a χ2/df = 2.542 < 3, (GFI = .983, NFI =.986, IFI = .992, TLI = .983, CFA = .992) > .90, and RMSEA = .072 < .08, it fitted the data and confirmed the unidimensionality. The measurement model of followers’ brand-link click behavior was not assessed using the CFA because it contained only two items. presents constructs, their dimensions, scale items, path statistics (ß, SE, t, and P), and average variance extracted (AVE).

Table 2. Constructs, dimensions, scale-items, path statistics and AVE.

Convergent and discriminant validity

Convergent validity, which indicates the strength of association between items of a construct, was assessed by evaluating their ß, SE, and t statistics. The ß of all construct measures were > SE, and their corresponding t statistics > 1.96 (), thus establishing convergent validity. Furthermore, the AVEs of all construct measures were > .5 (), thus confirming convergent validity. Discriminant validity, which indicates that measures of a construct are different from the measures of another construct in a proposed model was examined by comparing the square root of the AVE with the study construct correlations (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The square root of the AVE of the study constructs surpassed their correlations, thus confirming discriminant validity. The brand-link click behavior was excluded from the discriminant validity assessment due to fewer items. presents the discriminant validity matrix.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and discriminant validity matrix.

Proposed model and hypotheses testing

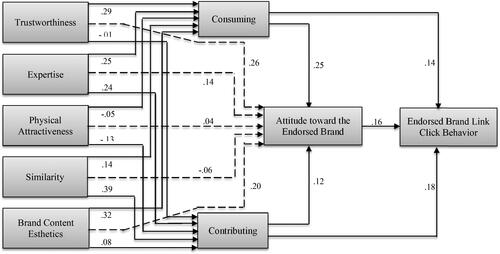

The structural model yielded a bad fit to data with a χ2 = 16.628, df = 6, and p = .011 < .05. Yet, it produced a good fit to data with χ2/df = 2.771 < 3 and GFI = .985, NFI = .982, IFI = .988, TLI = .928, CFI = .988 and RMSEA = .076. presents the tested model.

Path statistics (β, t, & p) between SMI attributes, brand content esthetics, and destination variables were assessed for hypotheses testing (). The β = .29, t = 4.862, and p = .000 < .001 indicated a significant relationship between trustworthiness and consuming. In contrast, β = −0.01, t = −0.020, and p = .984 > .05) revealed an insignificant relationship between trustworthiness and contributing. With β = .25, t = 3.975, and p = .000 < .001 and β = .24, t = 3.043, and p = .002 < .01, expertise indicated a significant relationship with consuming and contributing dimensions of followers’ brand content engagement, respectively. Both consuming (β = .25, t = 3.958, and p = .000 < .001) and contributing (β = .12, t = 2.360, & p = .018 < .05) dimensions of followers’ brand content engagement showed a significant relationship with their attitude toward the endorsed brand. These results partially supported H1a. With β = −0.05, t = −0.678, and p = .498 > .05 and β = −0.13, t = −1.488, and p = .137 > .05, physical attractiveness indicated insignificant relationships with consuming and contributing dimensions of followers’ brand content engagement respectively. Conversely, with β = .14, t = 3.046, and p = .002 < .01 and β = .39, t = 6.502, and p = .000 < .001, similarity indicated a significant relationship with consuming and contributing brand content, respectively. Both consuming (β = .25, t = 3.958, & p = .000 < .001) and contributing (β = .12, t = 2.360, & p = .018 < .05) brand content showed a significant relationship with their attitude toward the endorsed brand. These results partially supported H1b. With β = .32, t = 4.763, and p = .000 < .001, brand content esthetics indicated a significant relationship with consuming. On the contrary, with β = .08, t = .897, and p = .370 > .05, brand content esthetics indicated an insignificant relationship with contributing. Both consuming (β = .25, t = 3.958, & p = .000 < .001) and contributing (β = .12, t = 2.360, & p = .018 < .05) dimensions of followers’ brand content engagement showed a significant relationship with their attitude toward the endorsed brand. These results partially supported H1c.

With β = .26, t = 4.280, and p = .000 < .001, trustworthiness indicated a significant relationship with followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. Similarly, with β = .14, t = 2.151, and p = .031< .05, expertise indicated a significant relationship with followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. These results supported H2a. With β = .04, t = .522, and p = .601 > .05, physical attractiveness indicated an insignificant relationship with followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. Likewise, with β = −0.06, t = −1.323, and p = .186 > .05, similarity indicated an insignificant relationship with followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. These results did not support H2b. With β = .20, t = 2.829, and p = .005 < .01, brand content esthetics indicated a significant relationship with followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. These results supported H2c.

Both consuming (β = .25, t = 3.958, & p = .000 < .001 and contributing (β = .12, t = 2.360, & p = .018 < .05) dimensions of followers’ brand content engagement showed a significant relationship with their attitude toward the endorsed brand. With β = .16, t = 1.969, and p = .04 < .05, followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand indicated a significant relationship with their behavior to click on endorsed brand links. These results supported H3. With β = .14, t = 1.703, and p = .08 > .05, consuming brand content indicated an insignificant relationship with their behavior to click endorsed brand links. Conversely, with β = .18, t = 2.782, and p = .005 < .01, contributing brand content indicated a significant relationship with their behavior to click endorsed brand links. These results partially supported H4. presents the summary of hypotheses testing.

Table 4. Summary of hypotheses testing.

Discussion

Brand endorsement via SMIs has become a vital part of firms’ marketing communication strategy (Voorveld, Citation2019; Vrontis et al., Citation2021). The current study found McGuire’s (Citation1969, Citation1978) persuasive communication model valuable in understanding how attributes of SMI and SMI-generated content indirectly and directly influence followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand and brand-link click behavior on Instagram. Consistent with source effect models (Hovland et al., Citation1953; McGuire, Citation1985), the results showed credibility and attractiveness as distinct SMI attributes that influence followers’ endorsed brand content engagement and attitude differently. The results indicated SMI credibility as a two-dimensional model composed of trustworthiness and expertise, which is in line with prior research (e.g. Wiedmann & von Mettenheim, Citation2021). In line with earlier studies (e.g. Kim & Kim, Citation2021), the results supported physical attractiveness and similarity as dimensions of SMI attractiveness but not likeability. Furthermore, in agreement with previous research (e.g. Bashir et al., Citation2018; Masdari & Sarvari, Citation2021), the results indicated that followers perceive the SMI-generated brand content on Instagram as esthetically rich.

The results supported Tsai and Men (Citation2013) two-dimensional (i.e. consuming and contributing) model of brand content engagement. A key finding of the current study is that SMI-generated brand content engagement mediates between SMI credibility and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. Prior studies (e.g. Jiménez-Castillo & Sánchez-Fernández, Citation2019) support this finding. However, this mediation was partial in the case of SMI trustworthiness. For SMI expertise, brand content engagement showed absolute mediation. The results revealed that brand content engagement mediated between similarity and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. Similarity generates feelings of relatedness and perception of the content as relevant (Simons et al., Citation1970). These feelings and perceptions trigger followers’ engagement with SMI-generated brand content that eventually positively influences their attitude toward the endorsed brand (Raajpoot & Ghilni-Wage, Citation2019). The results did not show mediation of this kind in the case of SMI’s physical attractiveness. It suggests that SMI’s physical attractiveness does not determine the effectiveness of brand communication on Instagram (AlFarraj et al., Citation2021; Kim & Kim, Citation2021). Furthermore, the results indicated that only the consuming dimension of brand content engagement mediated between SMI-generated brand content esthetics and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. This partial mediating effect may be attributed to the followers’ behavior of watching and liking the brand content on social media more than sharing it (Baldwin et al., Citation2018).

Another significant finding of the current study is that SMI credibility and SMI-generated brand content esthetics directly influence followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. This finding validates the argument that source and content attributes may not necessarily affect the user brand attitude in a predetermined hierarchical order, as indicated in McGuire’s (Citation1969, Citation1978) model. They may directly influence users’ brand attitude in the persuasive communication process (Petty & Wegener, Citation1998). SMI marketing studies (e.g. Jin & Muqaddam, Citation2019; Lin et al., Citation2021) have also validated this argument. However, data did not support this type of direct relationship in the case of SMI attractiveness. Furthermore, consistent with prior studies (e.g. Torres et al., Citation2019; Trivedi & Sama, Citation2020), the results showed that attitude toward the endorsed brand mediated between brand content engagement and followers’ endorsed brand-link click behavior on Instagram. In addition, in line with Calder et al. (Citation2009), the results showed that brand content engagement triggered by SMI attributes and brand content esthetics directly influences followers’ endorsed brand-link click behavior.

Conclusion

SMI and SMI-generated brand content attributes lead to brand communication effectiveness on Instagram. Specifically, SMI trustworthiness, expertise, similarity, and brand content esthetics trigger followers’ brand content engagement and influence their attitude toward the endorsed brand. Brand content engagement on SMI’s Instagram account mediates between SMI attributes, brand content esthetics, and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. Furthermore, brand content engagement attitudinally and directly influence followers’ brand link-click behavior on Instagram.

Theoretical contribution

Considering the growing importance of SMI marketing, the current study addressed some critical research gaps in this area. Consistent with the suggestions by Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández (Citation2019), the current study assessed the mediation of brand content engagement on SMI’s Instagram account between SMI credibility, attractiveness, brand content esthetics, and followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. Prior research had treated brand engagement in the SMI marketing context as either antecedent or outcome (Vrontis et al., Citation2021). Thus, it is a salient addition to SMI marketing literature. Before assessing the mediating role of brand content engagement, SMI credibility and attractiveness were re-conceptualized as distinct attributes based on source effect models (Hovland et al., Citation1953; McGuire, Citation1985). Prior studies (e.g. AlFarraj et al., Citation2021; Khan & Saima, Citation2021) had treated attractiveness as a dimension of SMI credibility. This re-conceptualization of SMI attributes is an incremental contribution to some extent. Furthermore, the current study theorized brand content esthetics and measured its indirect and direct influence on followers’ attitude toward the endorsed brand. It was a crucial but under-addressed issue. In addition, the current study assessed the attitudinal and direct influence of brand content engagement on followers’ endorsed brand-link click behavior. Prior research had rarely tested this postulation. Clicking brand links on Instagram takes followers to the brand’s external website, where they may convert into customers (Chen et al., Citation2021). Moreover, the current study applied McGuire’s (Citation1969, Citation1978) persuasive communication model, which was hardly employed before in the SMI marketing context.

Practical implications

The significance of brand communication via SMIs has grown in the last few years (Voorveld, Citation2019; Vrontis et al., Citation2021). Instagram, in particular, has become the leading social media platform for promoting brands via SMIs (Hazari & Sethna, Citation2023). The current study findings indicate that SMI trustworthiness, expertise, and similarity drive the followers’ brand engagement and influence their attitude toward the endorsed brand. It implies that firms should hire those SMIs for brand endorsement whom followers perceive as trustworthy, experts, and share similar characteristics. Besides SMI attributes, content esthetics play a critical role in engaging followers with SMI-endorsed brands. It suggests that firms should encourage SMIs to share esthetically rich and pleasing brand-related photos and videos with their followers on social media. Brand content engagement and attitude toward the endorsed brands lead to followers’ brand-link click behavior. Therefore, SMIs should mention the endorsed brand links (company-owned Instagram accounts and sponsored links) while endorsing the brand. It would function as a cue for their followers while seeking company-owned accounts and sponsored brand links on Instagram for collecting further information or interacting with the seller.

Limitations and future research agenda

While the current study contributes to the SMI marketing literature on brand communication, it is not free of constraints. First, the current study examined the influence of only the SMI and brand content attributes on endorsed brand engagement, endorsed brand attitude, and brand link click behavior. Future research should examine this relationship using other input variables such as medium/channel identified in McGuire’s (Citation1969, Citation1978) persuasive communication model. Second, future research should examine the moderating role of followers’ demographic and psychographic variables while measuring the influence of SMI attributes and brand content esthetics on brand content engagement and endorsed brand attitude. Third, the current study presents followers’ insights about SMI-endorsed brand communication from a developing and collectivistic context. The cultural psyche might have influenced the followers’ responses in the current study. Therefore, replicating this study in a developed and individualistic context is warranted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aghazadeh, S., Brown, J. O., Guichard, L., & Hoang, K. (2022). Persuasion in auditing: A review through the lens of the communication-persuasion matrix. European Accounting Review, 31(1), 145–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2020.1863243

- AlFarraj, O., Alalwan, A. A., Obeidat, Z. M., Baabdullah, A., Aldmour, R., & Al-Haddad, S. (2021). Examining the impact of influencers’ credibility dimensions: Attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise on the purchase intention in the aesthetic dermatology industry. Review of International Business and Strategy, 31(3), 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1108/RIBS-07-2020-0089

- Arora, A., Bansal, S., Kandpal, C., Aswani, R., & Dwivedi, Y. (2019). Measuring social media influencer index-insights from Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 49(July), 86–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.03.012

- Baldwin, H. J., Freeman, B., & Kelly, B. (2018). Like and share: Associations between social media engagement and dietary choices in children. Public Health Nutrition, 21(17), 3210–3215. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018001866

- Bashir, A., Wen, J., Kim, E., & Morris, J. D. (2018). The role of consumer affect on visual social networking sites: How consumers build brand relationships. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 39(2), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2018.1428250

- Briggs, R., & Hollis, N. (1997). Advertising on the Web: Is there response before click-through? Journal of Advertising Research, 37(2), 33–45.

- Calder, B. J., Malthouse, E. C., & Schaedel, U. (2009). An experimental study of the relationship between online engagement and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23(4), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2009.07.002

- Chebat, J.-C., Hedhli, K. E., Gélinas-Chebat, C., & Boivin, R. (2007). Voice and persuasion in a banking telemarketing context. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 104(2), 419–437. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.104.2.419-437

- Chen, J. V., Nguyen, T., & Jaroenwattananon, J. (2021). What drives user engagement behavior in a corporate SNS account: The role of Instagram features. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 22(3), 199–227.

- Colliander, J., & Marder, B. (2018). Snap happy’ brands: Increasing publicity effectiveness through a snapshot aesthetic when marketing a brand on Instagram. Computers in Human Behavior, 78, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.09.015

- Comrey, A. L., & Lee, H. B. (1992). A first course in factor analysis (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cresswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Dangi, H. K., & Dhun, (2023). Influencer marketing: Role of influencer credibility and congruence on brand attitude and eWOM. Journal of Internet Commerce, 22(sup1), S28–S72. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2022.2125220

- De Jans, S., Van de Sompel, D., De Veirman, M., & Hudders, L. (2020). #Sponsored! How the recognition of sponsoring on Instagram posts affects adolescents’ brand evaluations through source evaluations. Computers in Human Behavior, 109, 106342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106342

- De Veirman, M. D., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/026

- Delbaere, M., Michael, B., & Phillips, B. J. (2021). Social media influencers: A route to brand engagement for their followers. Psychology & Marketing, 38(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21419

- Erz, A., & Christensen, A.-B H. (2018). Transforming consumers into brands: Tracing transformation processes of the practice of blogging. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 43(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2017.12.002

- Fabrigar, L. R., MacDonald, T. K., & Wegener, D. T. (2005). The structure of attitudes. In D. Albarracin, B. T. Johnson, & M. P. Zanna, (Eds.), The handbook of attitudes (pp. 79–124). Routledge.

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

- Fitriati, R., Siwi, I. S., M., Munawaroh, & Rudiyanto. (2023). Mega-influencers as online opinion leaders: Establishing cosmetic brand engagement on social media. Journal of Promotion Management, 29(3), 359–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2022.2143992

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., & Freberg, L. A. (2011). Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relations Review, 37(1), 90–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.11.001

- Gavilanes, J. M., Flatten, T. C., & Brettel, M. (2018). Content strategies for digital consumer engagement in social networks: Why advertising is an antecedent of engagement. Journal of Advertising, 47(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1405751

- Goldman, A. (2001). The aesthetic. In B. Gaur, & D. M. Lopes (Eds.), The Routledge companion to aesthetics (pp. 181–192). London.

- Hagtvedt, H. (2022). A brand (new) experience: Art, aesthetics, and sensory effects. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(3), 425–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00833-8

- Hazari, S., & Sethna, B. N. (2023). A comparison of lifestyle marketing and brand influencer advertising for generation Z Instagram users. Journal of Promotion Management, 29(4), 491–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2022.2163033

- Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., & Brodie, R. J. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2013.12.002

- Hovland, C. I., Jannis, I., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion. University Press.

- Jamal, A. (2020). Generation Z in Pakistan: Individualistic and collectivist in orientation. In E. Gentina, & E. Parry (Eds.), The new generation Z in Asia: Dynamics, differences, digitalisation (the changing context of managing people) (pp. 105–117). Emerald Publishing.

- Jiménez-Castillo, D., & Sánchez-Fernández, R. (2019). The role of digital influencers in brand recommendation: Examining their impact on engagement, expected value and purchase intention. International Journal of Information Management, 49, 366–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.07.009

- Jin, S. V., & Muqaddam, A. (2019). Product placement 2.0: Do brands need influencers, or do influencers need brands? Journal of Brand Management, 26(5), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-019-00151-z

- Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200275800200106

- Kemp, S. (2022). Digital 2022: Pakistan. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-pakistan.

- Khan, M. A., & Saima. (2021). Effect of social media influencer marketing on consumers’ purchase intention and the mediating role of credibility. Journal of Promotion Management, 27(4), 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2020.1851847

- Ki, C.-W., Cuevas, L. M., Chong, S. M., & Lim, H. (2020). Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102133

- Kim, D. Y., & Kim, H.-Y. (2021). Trust me, trust me not: A nuanced view of influencer marketing on social media. Journal of Business Research, 134, 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.024

- Kim, E., & Kim, Y. (2022). Factors affecting the attitudes and behavioral intentions of followers toward advertising content embedded within YouTube influencers’ videos. Journal of Promotion Management, 28(8), 1235–1256. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2022.2060414

- Kim, E., Shoenberger, H., & Sun, Y. (2021). Living in a material world: Sponsored Instagram posts and the role of materialism, hedonic enjoyment, perceived trust, and need to belong. Social Media + Society, 7(3), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/205630512110383

- Kok Wei, K., & Li, W. Y. (2013). Measuring the impact of celebrity endorsement on consumer behavioural intentions: A study of Malaysian consumers. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 14(3), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-14-03-2013-B002

- Kusumasondjaja, S. (2020). Exploring the role of visual aesthetics and presentation modality in luxury fashion brand communication on Instagram. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 24(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-02-2019-0019

- Lavie, T., & Tractinsky, N. (2004). Assessing dimensions of perceived visual aesthetics of web sites. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 60(3), 269–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2003.09.002

- Lee, D., Hosanagar, K., & Nair, H. S. (2018). Advertising content and consumer engagement on social media: Evidence from Facebook. Management Science, 64(11), 5105–5131. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2902

- Lin, C. A., Crowe, J., Pierre, L., & Lee, Y. (2021). Effects of parasocial interaction with an Instafamous influencer on brand attitudes and purchase intentions. Journal of Social Media in Society, 10(1), 55–78.

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

- Masdari, F., & Sarvari, S. H. H. (2021). The aesthetics of Instagram exploring the aesthetics of visual and semantic aspects of Instagram. Journal of Cyberspace Studies, 5(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/10.22059/JCSS.2021.325552.1060

- McCroskey, L. L., McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (2006). Analysis and improvement of the measurement of interpersonal attraction and homophily. Communication Quarterly, 54(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463370500270322

- McGuire, W. J. (1969). An information-processing model of advertising effectiveness. In H. L. Davis, & A. J. Silk, (Eds.), Behavioral and management science in marketing (pp. 156–180). Ronald Press.

- McGuire, W. J. (1978). An information-processing model of advertising effectiveness. In H. L. Davis, & A. J. Silk, A. J. (Eds.), Behavioral and management sciences in marketing (pp. 156–180). Wiley.

- McGuire, W. J. (1985). Attitudes and attitude change. In G. Lindzey, & E. Aronson (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (3rd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 233–346). Random House.

- Mir, I. A. (2018). Dimensionality and effects of information motivation on users’ online social network advertising acceptance. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 58(2), 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-759020180206

- Morton, F. (2020). Influencer marketing: An exploratory study on the motivations of young adults to follow social media influencers. Journal of Digital & Social Media Marketing, 8(2), 156–165.

- Mulilis, J.-P. (1998). Persuasive communication issues in disaster management. A review of the hazards mitigation and preparedness literature and a look towards the future. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 13(1), 151–159.

- Muntinga, D. G., Moorman, M &., & Smit, E. G. (2011). Introducing COBRAs: Exploring motivations for brand-related social media use. International Journal of Advertising, 30(1), 13–46. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-30-1-013-046

- Obilo, O. O., Chefor, E., & Saleh, A. (2021). Revisiting the consumer brand engagement concept. Journal of Business Research, 126, 634–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.12.023

- Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

- Petty, R. E., & Wegener, D. T. (1998). Attitude change: Multiple roles for persuasion variables. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 323–390). McGraw-Hill.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Preacher, K. J. (2015). Advances in mediation analysis: A survey and synthesis of new developments. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 825–852. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015258

- Pulles, N. J., & Hartman, P. (2017). Likeability and its effect on outcomes of interpersonal interaction. Industrial Marketing Management, 66, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.06.008

- Raajpoot, N. A., & Ghilni-Wage, B. (2019). Impact of customer engagement, brand attitude and brand experience on branded apps recommendation and re-use intentions. Atlantic Marketing Journal, 8(1), 1–18. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/amj/vol8/iss1/3.

- Rossiter, J. R., & Percy, L. (1985). Advertising communication models. In E. C. Hirschman, & M. B. Holbrook, (Eds.), Advances in consumer research (Vol. 12, pp. 510–524). Association for Consumer Research.

- Schimmelpfennig, C., & Hunt, J. B. (2020). Fifty years of celebrity endorser research: Support for a comprehensive celebrity endorsement strategy framework. Psychology & Marketing, 37(3), 488–505. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21315

- Simons, H. W., Berkowitz, N. N., & Moyer, R. J. (1970). Similarity, credibility, and attitude change: A review and a theory. Psychological Bulletin, 73(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0028429

- Spears, N., & Singh, S. N. (2004). Measuring attitude toward the brand and purchase intentions. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 26(2), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2004.10505164

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Experimental designs using ANOVA. Thomson/Brooks/Cole.

- Torres, P., Augusto, M., & Matos, M. (2019). Antecedents and outcomes of digital influencer endorsement: An exploratory study. Psychology & Marketing, 36(12), 1267–1276. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21274

- Triantafillidou, A., & Siomkos, G. (2018). The impact of Facebook experience on consumers’ behavioral brand engagement. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 12(2), 164–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-03-2017-0016

- Trivedi, J., & Sama, R. (2020). The effect of influencer marketing on consumers’ brand admiration and online purchase intentions: An emerging market perspective. Journal of Internet Commerce, 19(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2019.1700741

- Trunfio, M., & Rossi, S. (2021). Conceptualising and measuring social media engagement: A systematic literature review. Italian Journal of Marketing, 2021(3), 267–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-021-00035-8

- Tsai, W.-H. S., & Men, L. R. (2013). Motivations and antecedents of consumer engagement with brand pages on social networking sites. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 13(2), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2013.826549

- Van der Heijden, H. (2004). User acceptance of hedonic information systems. MIS Quarterly, 28 (4), 695–704. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148660

- Voorveld, H. A. M. (2019). Brand communication in social media: A research agenda. Journal of Advertising, 48(1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1588808

- Vrontis, D., Makrides, A., Christofi, M., & Thrassou, A. (2021). Social media influencer marketing: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(4), 617–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12647

- Wiedmann, K.-P., & von Mettenheim, W. (2021). Attractiveness, trustworthiness and expertise – social influencers’ winning formula? Journal of Product & Brand Management, 30(5), 707–725. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2019-2442

- Yang, Y., Tang, Y., Zhang, Y., & Yang, R. (2021). Exploring the relationship between visual aesthetics and social commerce through visual information adoption unimodel. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.700180

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257