ABSTRACT

Background

Few studies have examined dissolution rates among cohabitating and married couples, using prospective data.

Objective

The main aim was to examine trends in living arrangements and dissolution rates among married and cohabiting couples in Norway.

Method

Analysis of Norwegian longitudinal cohort data of 168,636 newly formed couples. Dissolution rates and relative risk were assessed at maximum 14 years of follow-up.

Results

Most of the married couples with a child were still living together after 14 years (65%), this was not the case for cohabiting couples. The majority of cohabiting couples who stay together eventually marry, particularly those who have children. At 4-year follow-up, young cohabiting couples had split up three times more often than married young couples.

Contribution

This study contributes by examining the effect of the living arrangement from a country where cohabitation has been the predominant living arrangement for many years.

Introduction

Strong, supportive and long-lasting interpersonal relationships increase the sense of belonging, which is a fundamental need associated with improved physical and mental health (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Vila, Citation2021). Thus, being in an intimate relationship, including marriage, cohabitation and dating, has been associated with high mental well-being, whereas being single or being divorced/widowed has consistently been associated with poorer mental well-being and increased distress during the course of one’s life, especially among men (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Grundström et al., Citation2021)

In most countries worldwide, the distribution of different relationship patterns has shifted, increasing nonmarital cohabitation and reducing marriage formation (Bloome & Ang, Citation2020; Perelli-Harris & Amos, Citation2015; Sassler & Lichter, Citation2020). Since the 1960s, radical changes in living arrangements, sexual habits, and the position of marriage has been described in Europe (Coleman, Citation2013), and the combination of new values and new behaviors which has resulted in changing family patterns has been called the Second Demographic Transition (Lesthaeghe, Citation2010, Citation2014, Citation2020). Consequently, nonmarital cohabitation has become a common and widely accepted form of partnership and is now an integral part in the lives of people in Europe, especially in the Nordic countries (Sassler & Lichter, Citation2020; Sobotka & Toulemon, Citation2008). Since the 1970s, Norway has had the highest proportion of cohabitation relative to marriage, at least among young adults. In the beginning of the 2000s the proportion of women aged 25–29 who cohabited for at least 1 year relative to all women at similar age who were living together in a marriage-like union, was slightly above 0.7 (Lesthaeghe, Citation2020). However, even in countries where cohabitation is very common, such as Norway, marriage is still considered the ideal (Lappegård & Noack, Citation2015).

Thus, cohabitation and marriage may seem to have distinct meanings, as the increase in cohabitation has not devalued the concept of marriage as an ideal for a long-term commitment (Perelli-Harris et al., Citation2014). Although cohabiting couples are a very heterogenous group (Thornton et al., Citation2007), cohabitation is often seen as a more individualistic and less institutionalized family form (Cherlin, Citation2004; Lewis, Citation2001), and cohabitating couples are generally less inclined to pool their resources compared to married couples (Vitali & Fraboni, Citation2022). Moreover, detraditionalization, women`s empowerment and changes in family policies, such as recognition of same-sex unions, have led to major changes in traditional views (Gross, Citation2005). Different attitudes toward cohabitation have also been revealed: Some couples view cohabitation as a common and socially accepted means of testing a relationship, whereas others view cohabitation as an alternative to marriage that can be legally recognized as equivalent (Hiekel & Keizer, Citation2015; Perelli-Harris et al., Citation2014). Any such conceptual boundaries that separate marriage from cohabitation are less salient in a Scandinavian context, and therefore could be less meaningful or consequential in everyday life (Hiekel et al., Citation2014). Still, studies from various places, including Scandinavian countries, indicate that cohabitators are generally more likely to report lower relationship commitment and satisfaction compared to married couples (Kulu & Boyle, Citation2010; Perelli-Harris & Amos, Citation2015; Schoen & Weinick, Citation1993; Wiik et al., Citation2012).

Cohabiting unions are also still significantly less stable than marital union (Andersson, Citation2002; Andersson & Philipov, Citation2002; Jalovaara, Citation2013; Jensen & Clausen, Citation2003; Liefbroer & Dourleijn, Citation2006; Manning et al., Citation2004; Musick & Michelmore, Citation2015, Citation2018; Rackin & Gibson‐Davis, Citation2018; Raley & Wildsmith, Citation2004; Wu & Musick, Citation2008). In a previous Norwegian study, cohabitors were more likely to end their current relationship than married respondents, but cohabitors with intention to marry current partners within 2 years differed less from married respondents than those with no marriage plans (Wiik et al., Citation2009). Moreover, results from a Finnish study showed that separation rates were highest at the beginning of a cohabitation union, whereas entry into marriage is followed by a significant drop in separation levels and a modest rising-falling pattern, which is independent of the length of premarital cohabitation (Jalovaara & Kulu, Citation2018).

Even if cohabitation might be intended to be a trial marriage (Harris, Citation2021; Kulu & Boyle, Citation2010), several studies have found that premarital cohabitation increases rather than decreases the risk of divorce (Budinski & Trovato, Citation2005; Cohan & Kleinbaum, Citation2002). However, this effect may have diminished in parallel with the increasing prevalence of cohabitation. In fact, Kulu and Boyle (Citation2010) discovered that, after controlling for a number of confounding factors, the risk of divorce was significantly lower for those who cohabitated prior to marriage compared to those who did not live together before marriage. Several factors may contribute to explain differences in divorce risk between cohabiting and married couples, for example, cohabiting individuals seem to have lower levels of commitment to their relationships compared to married individuals (Elizabeth & Baker, Citation2015; NOCK, Citation1995), and also higher incidence of domestic violence (Anderson, Citation1997; Brownridge & Halli, Citation2002). Regarding violence, Kenney and McLanahan (Citation2006), have argued that the higher rate of domestic violence observed among cohabiting couples might be explained by selection effects as the least violent couples tend to marry, whereas the most violent marriages tend to end in divorce.

In recent years, researchers have focused on what has been termed “gray divorce,” i.e., divorces among individuals over the age of 50. This phenomenon has been rapidly increasing in large parts of the Western world (Bildtgård, Citation2022; Brown et al., Citation2019; Koren et al., Citation2022). In 2010, approximately 1 in 4 divorces in the United States involved older adults (Brown & Lin, Citation2012) and the financial consequences, especially for women, are often detrimental (Lin et al., Citation2021).

Choosing cohabitation as a living arrangement may be related to various factors, such as age, gender, and economical safety. King and Scott (Citation2005) reported differences in views of cohabitation according to age, as elderly cohabiting couples seemed to view their relationship as an alternative to marriage, whereas younger cohabiting couples viewed it as a precursor to marriage. Furthermore, Reneflot (Citation2006) reported differences in attitude to marriage according to gender, with men being generally more hesitant to marry than women, and women being more concerned with the costs of the wedding. Moreover, financial stability may seem to play a significant role in cohabiting couples’ decisions to marry, according to Smock (Citation2005).

A basic aspect of the Second Demographic Transition is the sub-replacement fertility, paralleled by a steady rise of cohabitation observed in most European countries and elsewhere in the western world, during the few last decades (Lesthaeghe, Citation2014). The difference in stability between cohabitation and marriage is therefore of particular interest among parents. In keeping with this, it is notable that Scandinavian studies have reported that cohabitating couples planning to have children, were more likely to marry and less likely to break up (Moors & Bernhardt, Citation2009; Wiik et al., Citation2009). Still, previous findings among Norwegian parents during the 1980s and early 90s indicate that children born to cohabiting parents had 2.5 times higher risk of family dissolution than children born to married parents (Jensen & Clausen, Citation2003). Even larger differences have been reported in a more recent American study among a representative sample of adults, in which cohabiting parents had considerably higher risk of breaking up 2.5 years after having a baby compared to married parents; 24% vs. 2% breakups, respectively (Treter et al., Citation2021). These figures correspond with other findings from the U.S., indicating that 13% of the cohabiting couples ended their relationship within the first year after their baby’s birth (Lichter et al., Citation2016), whereas only 4% of married parents ended their relationship within that same time frame (Stykes, Citation2015). Given the short period of follow-up, these discrepancies may perhaps be accounted for by the documented disparities in cohabiting and married couples’ trajectories; that is, cohabitating couples have the highest risk of dissolution from the start, while marriages have a rising and falling pattern (Jalovaara, Citation2013; Jalovaara & Kulu, Citation2018).

The differences in relational quality and stability between cohabitants and married couples may be partly explained by factors such as younger age, lower socioeconomic status, increased likelihood of living in urban areas and decreased likelihood of being parents or expecting a child among cohabitating couples (Bloome & Ang, Citation2020; Jalovaara, Citation2013). Additionally, the majority of couples live together prior to marriage (Hiekel et al., Citation2014), particularly in Scandinavian countries (Jalovaara & Kulu, Citation2018), which implies a natural progression from cohabitation to marriage. In addition, cohabiting couples with the most stable relationships tend to increasingly choose marriage as their preferred living arrangement (Thomson et al., Citation2019).

Scandinavian countries are now leading the way in achieving gender equality in values, education, employment, and living conditions (Lesthaeghe, Citation2020). Moreover, Norwegian cohabiting couples with a joint biological child or those who have lived together for at least 2 years will have many of the same social security, pension, and taxation rights as married couples (Noack, Citation2001).

Most previous studies examining union dissolution risks have assessed data retrospectively through surveys or from registered data with limited data on the history of the living arrangements (Andersson, Citation2002; Jensen & Clausen, Citation2003; Raley & Wildsmith, Citation2004). As a result, there is a lack of understanding about the differences between married and non-married cohabiting couples who begin living together with or without a child. As the general Norwegian population has a particularly high proportion of young cohabiting couples (Lesthaeghe, Citation2020), our study aimed to examine cohabitation trends and dissolution rates among married and cohabitating couples in Norway from 2006 through 2020 according to age and birth of child. More precisely, we wanted to assess; i) whether the proportion of cohabitation relative to marriage has levelled off or continued to increase throughout this period; ii) to what extent any changes are different for couples at various ages, and for couples with or without children, and iii) whether any differences in the dissolution rate between cohabitating and married couples are contingent on their age or parental status.

Method

Data

The present study was based on longitudinal data collected by Statistics Norway. Couples were followed for several years and data on the groups specified below was made available for our research group to analyze at cohort level. Register data collected yearly by Statistics Norway between January 1, 2005, and January 1, 2020, were used to identify living arrangements among newly formed couples in 2006, 2011, and 2016, respectively. To select relevant data for analyses, we first selected those identified as couples living together as of January 1, 2006. To include only newly formed couples, we removed those identified as couples living together one year prior (as of January 1, 2005). Finally, the different types of living arrangements, cohabitation, and marriage, were identified. In order to assess age differences, we decided to create age groups based on 1) the age expectancy for couples to have their first child and 2) the age in which fertility has declined so much that getting pregnant naturally is unlikely. According to Krokedal (Citation2023), approximatley 50% of 30 years old Norwegian women have not delivered a child, and on average Norwegian women and men, have their first child at 30.1 and 32.1 years of age, respectively (Andersen, Citation2022). Further, at the age of 45, the end of fertility rises to approximately 90%. Thus, and according to the age of the oldest partner, the final sample of couples was grouped as follows: < 30-year-olds, 30–44-year-olds and > 44-year-olds. Furthermore, we identified couples who started living together with and without a newborn child (born between January 1, 2005, and January 1, 2006), and these two groups were analyzed separately. The same method for identification and grouping was used for the 2011 and 2016 cohorts, and we performed a yearly follow-up of each couple before the data was aggregated and further analyzed. The 2006 cohort included 14 years of follow-up. Married couples could continue living together, end their relationship by moving apart, or get divorced. In Norway, separation and divorce rates are registered by Statistics Norway, but both separation and divorce were considered indicators of union dissolution in this study. Thus, couples included in the present study could continue living together as a cohabitating couple, marry, or end their relationship by moving apart. From now on, couples who started cohabitating or their marriage without a child will be referred to as couples without a child, even if some members of that group may have had a child during follow-up. The other group of couples will be referred to as couples with a child. At each follow-up, we also assessed whether the couples had registered the birth of a first-born child. A cohabiting couple who started their relationship without a child could be a cohabiting or even married couple with a child at follow-up and thus continuing their relationship. The final sample consisted of 33,225 married and 135,411 cohabiting Norwegian couples (n = 168 636 couples). The data for this study may be downloaded here: DOI: (link will be provided at acceptance).

Analyses

We conducted descriptive and relative risk analyses using the Bayesian packages brr (Laurent, Citation2015) within the R software (R Core Team, Citation2017). The relative risk analyses calculate the risk of dissolution for couples in one type of relationship (cohabitation) compared to the risk of dissolution in another type of relationship (married). Thus, the formula used by the software to assess the relative risk for each group was (number of dissoluted cohabiting couples/total number of cohabiting couples)/(number of dissoluted married couples/total number of married couples). The output of Bayesian analytic methods are probability distributions for model parameters, conditional on the data and our assumptions. We used default non-informed priors. The Bayesian credible interval (CI) indicates the degree of uncertainty associated with our prediction based on the available data. We opted to show the range within which 95% of our predictions fall.

Results

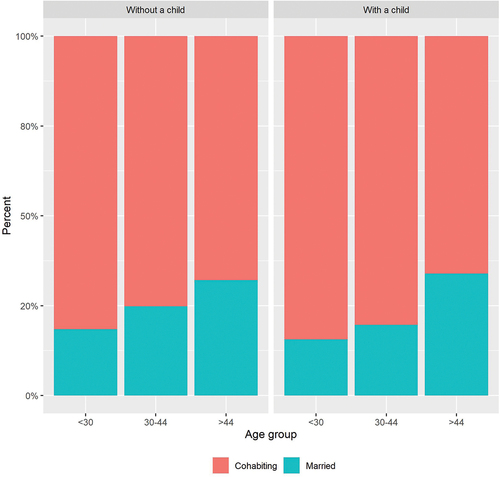

In the total sample, the proportion of cohabitating couples was 4.1 times higher than that of married couples (33,225 married and 135,411 cohabitating couples). A substantial increase in the proportion of cohabitants and a decrease in the proportion of married couples was observed between 2006 and 2016 (from 3.3 to 5.1 times more cohabitants). Among new couples with a child, the proportion of cohabitating couples was 4.4 times higher in 2006, 4.6 times higher in 2011, and 5.0 times higher in 2016 than the proportion of married couples. shows the percentages of cohabiting and married couples in each of the three age groups in 2006.

Among couples with a child, the portion of cohabitating couples vs. married couples increased only slightly from 2006 to 2016, whereas the increase was more substantial for couples without a child. We observed a lower marriage rate among couples with a child than without a child for the younger age groups. Among couples without a child, cohabiting comprised 76% of all the couples in 2006 and 84% in 2016. In the oldest age group without a child these figures increased from 68% to 80%. For more details, see . Married couples were older than cohabiting couples, especially if they did not have children. Furthermore, among all age groups, the age difference between the man and the woman was higher among married compared to cohabiting couples.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the sample.

In the total sample of cohabiting couples without a child, a majority (57.1%) were not living together after 14 years. Only 7.3% of all couples were still cohabitants without a child, whereas 9.4% had given birth to a child but were still unmarried. Moreover, 6.1% had no children but had married, while 20.0% had children and were married. Among the youngest group of cohabiting couples without a child, only 2% were still living together after 14 years – either as cohabitants or married (1% in each condition) if they still did not have any children. Corresponding figures for the oldest couples were 37.5% (21.4% as cohabitants and 16.2% as married).

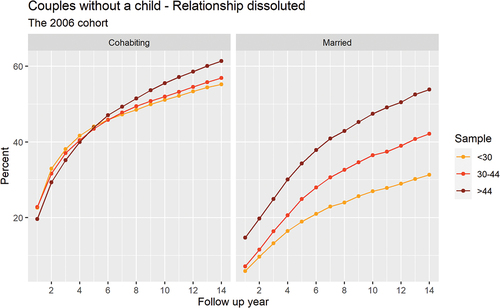

At 14 years follow-up, 42.6% of the total sample of married couples without a child had experienced relationship dissolution. As illustrated in , the oldest group of married couples with and without a child had the highest risk of relationship dissolution. Unexpectedly, we found that 25.5% of the married couples in the oldest age group without a child decided to separate while still legally married, while 28.3% moved away and divorced (see Figures s1 and s2 in the supplemental material for details). The supplemental material contains details of relationship dissolution for all three cohorts (2006, 2011, 2016) of married and cohabiting couples.

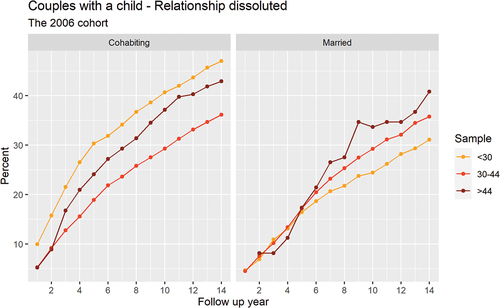

As depicted in , cohabitating couples’ relative risk of breaking up decreased over time for all age groups. The highest relative risk of union dissolution was observed among the youngest age groups of couples without a child, in which cohabitants had a 2.5 to 3.2 times higher risk of relationship dissolution than married couples in the subsequent 4 years after entering into a cohabitation agreement. Corresponding figures for the two older groups of couples without a child were 1.4 to 2.5. Among couples with a child, the youngest group of cohabitants had a relative risk of relationship dissolution between 1.5 and 2.0, whereas no significant differences in relative risk were observed in the other two age groups, except for the oldest couples in the 2016 cohort.

Table 2. Dissolution rate and relative risk.

Discussion

Results from the present study showed that the proportion of married couples has decreased, whereas the proportion of cohabitating has dramatically increased between 2006 and 2016, particularly among couples without a child. This trend is in line with other studies reporting that from the 1980s, newly formed couples had an increased tendency to move in together without being married in the Nordic countries (Noack, Citation2001), Europe (Lesthaeghe, Citation2020) and the U.S (Smock & Schwartz, Citation2020). Since Norway has had the highest proportion of cohabitants among marriage-like unions since the 1980s (Lesthaeghe, Citation2020), it is notable that cohabitation has continued to increase throughout this period. This may indicate that the Second Demographic Transition has not yet levelled off or reached any ceiling effect with regard to cohabitation. Therefore, countries that lag behind this transition may expect further growth of couples living in marriage-like unions without being married. In line with this expectation, results from our study showed lower marriage rates among couples with a child than without a child. This trend might also be partly explained by the fact that the legal system in Norway has over time gradually provided cohabitors with similar rights to married couples, particularly those having children together (Lovdata, Citation2021). Moreover, as raising a child require commitment of time and finances, cohabitation without being married may be the chosen solution for many parents of young children due to the time, money and effort needed to plan a wedding (Reneflot, Citation2006).

Furthermore, as predicted by the Second Demographic Transition the increase in cohabitation was most evident among couples without a child in the present study, which may indicate that childbearing is still associated with a need for a more formalized relationship even if cohabitating parents in Norway generally have the same rights as married parents (Lovdata, Citation2021; Noack, Citation2001). Moreover, the increasing trend of living together without being married applied particularly to the youngest age groups. This finding corresponds with the general trend of postponement of marriage observed in most Western countries (Lesthaeghe, Citation2020; Sassler & Lichter, Citation2020), which also is a central part of the Second Demographic Transition.

In line with previous studies, more cohabitants than married couples broke up during the following years after moving in together, but the difference was much smaller than has frequently been reported (e.g., Jensen & Clausen, Citation2003; Lichter et al., Citation2016; Treter et al., Citation2021). Jensen and Clausen (Citation2003) concluded in their study of breakup among cohabiting and married parents in Norway between 1980 and 1992, that the elevated risk of dissolution for cohabiting parents had not diminished even if cohabitation became more prevalent during that period. However, our study is undertaken in a period in which cohabitation has become the predominant living condition at the time of the first child’s birth, and during this period the risk of dissolution among cohabiting parents relative to married parents has steadily decreased. In fact, for married and cohabiting couples between 30 and 44 years with a child, there was no substantial difference in dissolution risk.

A similar declining trend over time has been demonstrated from other studies of Norwegian couples conducted by our research group, focusing on differences in dissolution risk between first-time married couples and remarried (Zahl-Olsen, Citation2022); different types of remarried couples (Zahl-Olsen et al., Citation2019); and same-sex couples vs. different-sex couples (Zahl-Olsen & Thuen, Citation2022). Thus, this may suggest that the observed declining difference in dissolution risk between cohabitants and married couples is part of a more general trend in Norway during the last decades where the conceptual boundaries that separate various types of living arrangments has become less salient and therefore less consequential in everyday life.

An alternative explanation for these findings may reflect the way living arrangement was measured in the present study. In contrast to much of the previous research in which the stability of cohabitation couples has been based on an arbitrary distinction between cohabitants and married couples rather than acknowledging that most couples start living together before they eventually enter marriage (Jalovaara, Citation2013). Thus, when comparing cohabitating and married couples as distinct groups from the point when they start living together, the differences between the two groups seem to diminish or almost disappear (Jalovaara, Citation2013). However, it is likely that some of the couples in this study, perhaps most of them, have partly been living together informally in the same household before they officially moved into the same residence. Still, by extracting data about couples who start their formal living arrangement either as cohabitants or as a married couple, we could differentiate between more distinct groups than most previously conducted studies. Therefore, this data may provide more valid findings regarding the actual risk of dissolution among cohabitants and married couples. This is of particular significance for cohabitating parents since any parental breakups may have a serious impact on the stability of the children’s upbringing and well-being (Grundström et al., Citation2021; Lansford, Citation2009).

Contrary to the general declining trend of divorce during the last decades in many Western countries (Raley & Sweeney, Citation2020; Zahl-Olsen, Citation2022), we did not identify a consistent pattern at four-year follow-up. For all age groups of married couples without a child, a decline was identified from 2006 to 2016, while the trend was inclining for all age groups of cohabitants.

Moreover, we observed that the dissolution risk increased with age throughout the follow-up period for couples without a child. The risk of breakup was lowest among couples below 30 years of age and highest for the oldest group. A similar pattern was observed among couples with a child, with a few exceptions. This is contrary to much of the previous research on marriage and divorce, where a strong inverse association between age-at-marriage and divorce risk has been reported (Glass & Levchak, Citation2014; Kuperberg, Citation2014; Lyngstad & Jalovaara, Citation2010). However, a recent study from our research team did not identify the age of marriage as a substantial predictor of divorce for cohorts from 1981 until 2018 (Zahl-Olsen, Citation2022). Thus, this association is potentially contingent on various cultural, societal, or historical contexts.

Even if most of the cohabiting couples without a child dissolved within 14 years, most of the lasting ones ended up as married couples. Also, for cohabiting couples with a child, most of the lasting cohabiting couples got married within 14 years. This indicates that marriage still appears to be the choice for lasting relationships, in contrast to predictions based on the Second Demographic Transition that forecasts an increasing emphasis on individual autonomy and self-actualization and, consequently, a fall in the high value of monogamous and institutionalized marriages (Lesthaeghe, Citation2014). On the other hand, the popularity of marriage has declined almost all over the globe during the last few decades (Sassler & Lichter, Citation2020). When focusing only on the transition from cohabitation to marriage, it might seem as if cohabitation is now more the new marriage rather than a living condition prior to marriage, a conclusion made by other researchers (Hiekel & Keizer, Citation2015; Perelli-Harris et al., Citation2014). However, since most cohabiting couples end their relationship, this may lead to a false conclusion. Our study identifies that among those starting as nonmarital cohabiting couples, the majority chose to marry if they continue in the relationship, especially after getting a child.

Research on gray divorces has shown a rapid increase during the last decades (Brown & Lin, Citation2012). Our study also revealed high divorce rates among the oldest group of couples (≥45 years of age). More surprisingly, we found that a high number of the married couples without a child above 45 years of age were moving away from their partner, without being formally divorced or separated. To our knowledge, this trend has not been identified by other studies, which may suggest that the numbers of gray breakups are even larger than previously indicated. Possible explanations for this observed trend might be religious or cultural attitudes against divorce, or that they chose a living apart together relationship (Levin & Trost, Citation1999). In any case, if this pattern also exists in other countries, this may indicate that research based on marriage and divorce records is underestimating the portion of broken relationships in their population.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of the present study is the high number of participants from all over Norway, a long follow-up period, the inclusion of different age groups, and information on family composition. Another strength is that we had access to data that made it possible to identify newly formed couples (within the past year). This is of great importance when comparing married and nonmarital relationships on equal conditions. However, the strategy utilized in this study to identify new couples has some shortcomings. Firstly, we do not know whether the pair lived together earlier in life (i.e., remarried or re-cohabited). Secondly, we do not know if the participants identified themselves as a couple for a long or short period before moving in together.

Furthermore, even though almost 2% of all marriages in Norway are same-sex marriages (Zahl-Olsen, Citation2022), and it is possible to assume that it is at least as common among cohabitations, they were not included in the present study as we did not have the necessary information available to detect this groups.

Conclusion and implications for future research

Firstly, even though Norway has led the transition from marriage to cohabitation since the 1980s (Lesthaeghe, Citation2020), the proportion of cohabitating couples continued to increase between 2006 and 2016, especially among childless couples. Secondly, the increased risk of dissolution among cohabiting parents compared to married parents was substantially lower in our study than in studies with a predominantly married population (e.g., Lichter et al., Citation2016; Treter et al., Citation2021). Thus, as cohabitation becomes more prevalent, the disparity between cohabiting and married parents’ likelihood of dissolution seems to diminish. Thirdly, we discovered that the risk of dissolution increased with age throughout the follow-up period, which contradicts the findings of earlier research (Glass & Levchak, Citation2014; Kuperberg, Citation2014; Lyngstad & Jalovaara, Citation2010).

Future research should investigate if these findings apply to other countries, and when comparing the dissolution of cohabitations and marriage researchers should take into account the fact that these living arrangements are typically different stages of a relationship rather than separate entities. Future research should also aim to utilize data relevant for individual-level analysis, as opposed to cohort data.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.4 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2023.2277648

References

- Andersen, E. (2022). Økt fruktbarhet for første gang på 12 år. Statistics Noway. https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/fodte-og-dode/statistikk/fodte/artikler/okt-fruktbarhet-for-forste-gang-pa-12-ar

- Anderson, K. L. (1997). Gender, status, and domestic violence: An integration of feminist and family violence approaches. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59(3), 655–669. https://doi.org/10.2307/353952

- Andersson, G. (2002). Children’s experience of family disruption and family formation: Evidence from 16 FFS countries. Demographic Research, 7, 343–364. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2002.7.7

- Andersson, G., & Philipov, D. (2002). Life-table representations of family dynamics in Sweden, Hungary, and 14 other FFS countries: A project of descriptions of demographic behavior. Demographic Research, 7, 67–144. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2002.7.4

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Bildtgård, T. (2022). Gray divorce: An increasingly common path to uncoupling in later life. Innovation in Aging, 6(Suppl 1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igac059.153

- Bloome, D., & Ang, S. (2020). Marriage and union formation in the United States: Recent trends across racial groups and economic backgrounds. Demography, 57(5), 1753–1786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00910-7

- Brown, S. L., & Lin, I. F. (2012). The gray divorce revolution: Rising divorce among middle-aged and older adults, 1990–2010. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(6), 731–741. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs089

- Brown, S. I., Lin, I. F., Hammersmith, A. M., & Wright, M. R. (2019). Repartening following gray divorce: The roles of resources and constraints for womem and men. Demography, 56(2), 503–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0752-x

- Brownridge, D. A., & Halli, S. S. (2002). Understanding male partner violence against cohabiting and married women: An empirical investigation with a synthesized model. Journal of Family Violence, 17(4), 341–361. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020370516420

- Budinski, R. A., & Trovato, F. (2005). The effect of premarital cohabitation on marital stability over the duration of marriage. Canadian Studies in Population [ARCHIVES], 32(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.25336/P6B304

- Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(4), 848–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00058.x

- Cohan, C. L., & Kleinbaum, S. (2002). Toward a greater understanding of the cohabitation effect: Premarital cohabitation and marital communication. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(1), 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1741-3737.2002.00180.X

- Coleman, D. (2013). Partnership in Europe; its variety, trends and dissolution. Finnish Yearbook of Population Research, 48, 5–49. https://doi.org/10.23979/fypr.40927

- Elizabeth, V., & Baker, M. (2015). Transition through cohabition to marriage: Emerging commitment and diminishing ambiguity. Family Relationships and Societies, 4(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674314X14036151626086

- Glass, J., & Levchak, P. (2014). Red states, blue states, and divorce: Understanding the impact of conservative Protestantism on regional variation in divorce rates. American Journal of Sociology, 119(4), 1002–1046. https://doi.org/10.1086/674703

- Gross, N. (2005). The detraditionalization of intimacy reconsidered. Sociological Theory, 23(3), 286–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0735-2751.2005.00255.x

- Grundström, J., Konttinen, H., Berg, N., & Kiviruusu, O. (2021). Associations between relationship status and mental well-being in different life phases from young to middle adulthood. SSM-Population Health, 14, 100774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100774

- Harris, L. E. (2021). Committing before cohabiting: Pathways to marriage among middle-class couples. Journal of Family Issues, 42(8), 1762–1786. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X20957049

- Hiekel, N., & Keizer, R. (2015). Risk-avoidance or utmost commitment? Dutch focus group research on cohabitation and marriage. Demographic Research, 32, 311–340. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2015.32.10

- Hiekel, N., Liefbroer, A. C., & Poortman, A.-R. (2014). Understanding diversity in the meaning of cohabitation across Europe. European Journal of Population, 30(4), 391–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10680-014-9321-1

- Jalovaara, M. (2013). Socioeconomic resources and the dissolution of cohabitations and marriages. European Journal of Population, 29(2), 167–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-012-9280-3

- Jalovaara, M., & Kulu, H. (2018). Separation risk over union duration: An immediate itch? European Sociological Review, 34(5), 486–500. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy017

- Jensen, A.-M., & Clausen, S.-E. (2003). Children and family dissolution in Norway: The impact of consensual unions. Childhood, 10(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568203010001004

- Kenney, C. T., & McLanahan, S. S. (2006). Why are cohabiting relationships more violent than marriages? Demography, 43(1), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2006.0007

- King, V., & Scott, M. E. (2005). A comparison of cohabiting relationships among older and younger adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00115.x

- Koren, C., Cohen, Y., Demeter, N., & Egert, M. (2022). The meaning of familiehood for gray divorces in Israel. Innovation in Aging, 6(Supplement 1), 41–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igac059.157

- Krokedal, L. (2023). Rekordlav fruktbarhet i 2022. Statistics Norway. https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/fodte-og-dode/statistikk/fodte/artikler/rekordlav-fruktbarhet-i-2022

- Kulu, H., & Boyle, P. (2010). Premarital cohabitation and divorce: Support for the “trial marriage” theory? Demographic Research, 23, 879–904. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.31

- Kuperberg, A. (2014). Age at coresidence, premarital cohabitation, and marriage dissolution: 1985–2009. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(2), 352–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12092

- Lansford, J. E. (2009). Parental divorce and children’s adjustment. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(2), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01114.x

- Lappegård, T., & Noack, T. (2015). The link between parenthood and partnership in contemporary norway-findings from focus group research. Demographic Research, 32, 287–310. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2015.32.9

- Laurent, S. (2015). Brr Package for R. In https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/brr/versions/1.0.0

- Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00328.x

- Lesthaeghe, R. (2014). The second demographic transition: A concise overview of its development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(51), 18112. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1420441111

- Lesthaeghe, R. (2020). The second demographic transition, 1986–2020: Sub-replacement fertility and rising cohabitation—a global update. Genus, 76(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-020-00077-4

- Levin, I., & Trost, J. (1999). Living apart together. Community, Work & Family, 2(3), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668809908412186

- Lewis, J. (2001). The end of marriage?. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lichter, D. T., Michelmore, K., Turner, R. N., & Sassler, S. (2016). Pathways to a stable union? Pregnancy and childbearing among cohabiting and married couples. Population Research and Policy Review, 35(3), 377–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9392-2

- Liefbroer, A. C., & Dourleijn, E. (2006). Unmarried cohabitation and union stability: Testing the role of diffusion using data from 16 European countries. Demography, 43(2), 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2006.0018

- Lin, I. F., Brown, S. L., & Carr, D. S. (2021). The economic consequences of gray divorce for women and men. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(10), 2073–2085. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa157

- Lovdata. (2021). Lov om arv og dødsboskifte (arveloven). Retrieved July 5, 2023. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2019-06-14-21?q=arveloven

- Lyngstad, T., & Jalovaara, M. (2010). A review of the antecedents of union dissolution. Demographic Reseach, 23, 257–292. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.10

- Manning, W. D., Smock, P. J., & Majumdar, D. (2004). The relative stability of cohabiting and marital unions for children. Population Research and Policy Review, 23(2), 135–159. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:POPU.0000019916.29156.a7

- Moors, G., & Bernhardt, E. (2009). Splitting up or getting married? Competing risk analysis of transitions among cohabiting couples in Sweden [peer reviewed]. Acta Sociologica, 52(3), 227–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001/6993/0933/9800

- Musick, K., & Michelmore, K. (2015). Change in the stability of marital and cohabiting unions following the birth of a child. Demography, 52(5), 1463–1485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0425-y

- Musick, K., & Michelmore, K. (2018). Cross-national comparisons of union stability in cohabiting and married families with children. Demography, 55(4), 1389–1421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0683-6

- Noack, T. (2001). Cohabitation in Norway: An accepted and gradually more regulated way of living. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 15(1), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/15.1.102

- NOCK, S. L. (1995). A comparison of marriages and cohabiting relationships. Journal of Family Issues, 16(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251395016001004

- Perelli-Harris, B., & Amos, M. (2015). Changes in partnership patterns across the life course: An examination of 14 countries in Europe and the United States. Demographic Research, 33(6), 145–178. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2015.33.6

- Perelli-Harris, B., Mynarska, M., Berrington, A., Berghammer, C., Evans, A., Isupova, O., Keizer, R., Klärner, A., Lappegård, T., & Vignoli, D. (2014). Towards a new understanding of cohabitation: Insights from focus group research across Europe and Australia. Demographic Research, S17(34), 1043–1078. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.34

- Rackin, H. M., & Gibson‐Davis, C. M. (2018). Social class divergence in family transitions: The importance of cohabitation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(5), 1271–1286. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12522

- Raley, R. K., & Sweeney, M. M. (2020). Divorce, repartnering, and stepfamilies: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12651

- Raley, R. K., & Wildsmith, E. (2004). Cohabitation and children’s family instability. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(1), 210–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00014.x-i1

- R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Reneflot, A. (2006). A gender perspective on preferences for marriage among cohabitating couples. Demographic Research, 15, 311–328. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2006.15.10

- Sassler, S., & Lichter, D. T. (2020). Cohabitation and marriage: Complexity and diversity in union‐formation patterns. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12617

- Schoen, R., & Weinick, R. M. (1993). Partner choice in marriages and cohabitations. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55(2), 408–414. https://doi.org/10.2307/352811

- Smock, P. J., & Schwartz, C. R. (2020). The demography of families: A review of patterns and change. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 9–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12612

- Sobotka, T., & Toulemon, L. (2008). Overview chapter 4: Changing family and partnership behaviour: Common trends and persistent diversity across Europe. Demographic Research, S7(6), 85–138. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.6

- Stykes, B. (2015). FP-15-11 marital stability following mother’s 1st marital birth. National Center for Family and Marriage Research Family Profiles. Retrieved 31.03.22, from https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/ncfmr_family_profiles/76

- Thomson, E., Winkler-Dworak, M., & Beaujouan, É. (2019). Contribution of the rise in cohabiting parenthood to family instability: Cohort change in Italy, Great Britain, and Scandinavia. Demography, 56(6), 2063–2082. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00823-0

- Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., & Xie, Y. (2007). Marriage and cohabitation. University of Chicago Press.

- Treter, O., Rhoades, M., K, G., Scott, S. B., Markman, H. J., & Stanley, S. M. (2021). Having a baby: Impact on married and cohabiting parents’ relationships. Family Process, 60(2), 477–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12567

- Vila, J. (2021). Social support and longevity: Meta-analysis-based evidence and psychobiological mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 717164–717164. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.717164

- Vitali, A., & Fraboni, R. (2022). Pooling of wealth in marriage: The role of premarital cohabitation. European Journal of Population, 38(4), 721–754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-022-09627-2

- Wiik, K. A., Bernhardt, E., & Noack, T. (2009). A study of commitment and relationship quality in Sweden and Norway. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(3), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00613.x

- Wiik, K. A., Keizer, R., & Lappegård, T. (2012). Relationship quality in marital and cohabiting unions across Europe. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(3), 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00967.x

- Wu, L. L., & Musick, K. (2008). Stability of marital and cohabiting unions following a first birth. Population Research and Policy Review, 27(6), 713–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-008-9093-6

- Zahl-Olsen, R. (2022). Understanding divorce trends and risks: The case of Norway 1886–2018. Journal of Family History, 48(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/03631990221077008

- Zahl-Olsen, R., & Thuen, F. (2022). Same-sex marriage over 26 years: Marriage and divorce trends in rural and urban Norway. Journal of Family History, 48(2), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/03631990221122966

- Zahl-Olsen, R., Thuen, F., & Espehaug, B. (2019). Divorce and remarriage in Norway: A prospective cohort study between 1981 and 2013. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 60(8), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2019.1619378