Abstract

Background: the typical mode of assessment in studies on intersession processes (ISP) in psychotherapy is using cross-sectional or weekly measurements. Daily dynamics of intersession processes have not yet been studied. Method: intersession process data from 22 ambulatory psychotherapy cases were collected in a naturalistic study with high temporal resolution, resulting in a total of 1026 daily measurements. Multilevel vector autoregressive (VAR) modelling was applied to discover the temporal course and causal influences among intersession processes. Centrality analysis was applied to discover unique functions of various intersession process variables. Results: a group-level network structure was discovered, offering first insights on the role of different intersession processes during psychotherapy. Centrality analysis revealed unique roles for various aspects of the intersession process. Temporal distance from the last session had only weak influence on the ISP. Conclusions: using short, daily measures, the unique role of various aspects of the ISP were uncovered. Some aspects of the ISP, like recalling session contents or reflection on future session contents, are facilitators of overall ISP intensity. Other aspects like thoughts on payment or appointments or negative treatment-related emotions are likely to suppress ISP.

lLa modalità tipica di valutazione negli studi sui processi tra le sedute (ISP) in psicoterapia sta usando misurazioni trasversali o settimanali. Le dinamiche quotidiane dei processi tra le sedute non sono ancora state studiate. Metodo: i dati del processo tra le sedute di 22 casi di psicoterapia ambulatoriale sono stati raccolti in uno studio naturalistico con alta risoluzione temporale, ottenendo un totale di 1026 misurazioni giornaliere. La modellazione autoregressiva vettoriale multilivello (VAR) è stata applicata per scoprire il corso temporale e le influenze causali tra i processi tra le sedute. L'analisi della centralità è stata applicata per scoprire le funzioni uniche di varie variabili del processo ISP. Risultati: è stata evidenziata una struttura di rete a livello di gruppo, che offre delle prime intuizioni sul ruolo dei diversi processi tra le sedute durante la psicoterapia. L'analisi della centralità ha rivelato ruoli unici per vari aspetti del processo tra le sedute. La distanza temporale dall'ultima sessione ha avuto solo un'influenza debole sull'ISP. Conclusioni: usando brevi misure quotidiane, è stato scoperto il ruolo unico di vari aspetti dell'ISP. Alcuni aspetti dell'ISP, come il richiamo dei contenuti della sessione o la riflessione sui contenuti della sessione futura, sono facilitatori dell'intensità complessiva dell'ISP. Altri aspetti come pensieri sul pagamento o appuntamenti o emozioni negative legate al trattamento probabilmente sopprimono l'ISP.

Introdução: o modo típico de avaliação em estudos sobre processos entre sessão (PES) em psicoterapia é usando medidas transversais ou semanais. A dinâmica diária dos processos de intersessão ainda não foi estudada. Método: os dados do processo entre sessões de 22 casos de psicoterapia ambulatorial foram coletados em um estudo naturalista com alta resolução temporal, resultando em um total de 1026 medidas diárias. O modelo multinível de autorregressão vetorial foi aplicado para descobrir o curso temporal e as influências causais entre os processos entre sessões. A análise de centralidade foi aplicada para descobrir funções únicas de várias variáveis do processo entre sessão. Resultados: uma estrutura de rede em nível grupal foi descoberta, oferecendo idéias iniciais sobre o papel dos diferentes processos entre sessões durante a psicoterapia. A análise da centralidade revelou papéis únicos para vários aspectos do processo entre sessão. A distância temporal da última sessão teve apenas uma fraca influência no PES. Conclusões: usando medidas diárias curtas, foi descoberto o papel único de vários aspectos do PES. Alguns aspectos do PES, como recuperar o conteúdo da sessão ou refletir sobre o conteúdo da sessão futura, são facilitadores da intensidade geral do PES. Outros aspectos, como pensamentos sobre pagamento ou compromissos ou emoções negativas relacionadas ao tratamento, provavelmente irão suprimir o PES.

目的:在心理治療中,逐次晤談間之歷程(ISP)的典型評估方式多是使用每週或是橫斷式量表。ISP 的每日動力尚未被研究。方法:在自然研究中,藉由高時間解 析率從 22 位日間心理治療個案搜集了 1026 份每日量表。應用多階層向量自回歸模式(VAR)以探究 ISP 的時間過程與因果影響。中心度分析則應用於發現不同 ISP 變項的獨特功能。結果:發現一個團體層次的網絡架構,此架構對心理治療中不同 ISP 所扮演的角色提供提供初步的見解。中央性分析顯示出 ISP 不同面向的獨特角色。而從最後一次晤談的時間距離,對 ISP 則只具有微弱影響。結論:使用短版的每日量表可以發現 ISP 不同面向的獨特角色。ISP 的一些面向,例如:回想晤談內 容或是未來歷程內容的反思,是整體 ISP 強度的催化劑。至於其他面向,例如:對於費用或預約的想法、或是與處遇相關的負向情緒,則可能抑制 ISP。

Clinical and methodological significance: In recent years, an increasing number of empirical studies have been conducted to model psychopathological data obtained from high-frequency outpatient studies. Leading authors in this area have called for variables other than symptoms to be included in these models. This article is intended to contribute to this by offering a short scale for the measurement of intersession processes.

For the first time, intersession processes are modelled using approaches from network analysis using data from daily measurements. This offers first insights into the role of different change processes in psychotherapy.

Introduction

A successful psychotherapy continues to have an effect after a session and between sessions. Over time, patients begin to form mental representations of their psychotherapy that can be activated between therapy sessions. Following this assumption, Orlinsky, Geller, Tarragona, and Farber (Citation1993) proposed the “representations of a patient’s psychotherapy between two sessions” as a focus for psychotherapy research, building the foundation of what later on became the concept of intersession processes (ISP). The concept of ISP encompasses thoughts, feelings, and behaviours concerning a patient’s current psychotherapy, including the therapist. ISP occur between two therapy sessions and can be of different emotional quality, intensity, and frequency. They include memories of words and feelings towards the dyadic partner as well as application of techniques learned in the psychotherapy or therapeutic homework (Hartmann, Orlinsky, & Zeeck, Citation2011). ISP have been operationalized and can be measured for a specific period between two sessions using the “Intersession Experience Questionnaire.” Patients’ positive ISP have been linked to a better therapy outcome in various studies (Schröder, Wiseman, & Orlinsky, Citation2009) and were found to be predictive of therapy outcome if measured weekly before a therapy session (Hartmann, Orlinsky, Weber, Sandholz, & Zeeck, Citation2010; Zeeck et al., Citation2016).

Most of the previous studies have assessed the intersession process only retrospectively, using cross-sectional designs. One notable exception is a multilevel analysis of weekly assessments in a large dataset conducted by (Hartmann et al., Citation2016).

This study showed characteristic patterns of change that differed significantly between patients with favourable and less favourable outcomes. Due to the relatively short time that outpatients are exposed to clinical procedures, fine-grained information about their ISP can also be helpful for the therapist. Empirical evidence of how a successful therapy works between sessions remains remarkably scarce. This could be the result of a prolonged debate on how change processes in psychology should be examined in general (Cronbach & Furby, Citation1970; Molenaar, Citation2004). It has been argued that psychological processes do not possess the properties that would enable researchers to study them in cross-sectional designs because they are non-ergodic (Molenaar, Citation2013). Non-ergodic processes are non-stationary, so their mean values and variances change over time. Moreover, these processes are not homogeneous, implying that their underlying dynamic model varies across different people. This requires data analysis methods that begin at the level of intraindividual variation and try to generalize individual models to a group level in a second step. Although valid arguments have been put forward for both individual designs and group studies, these approaches need not be mutually exclusive. Recent developments in time series analysis have produced approaches that can combine the strengths of case studies with the robustness of group designs (Tschacher & Ramseyer, Citation2009).

So far, however, the intersession process has not been investigated with sufficient temporal resolution to really understand its dynamics in psychotherapy. The daily measurement of these processes could reveal important patterns that show how psychotherapy patients process their therapies and deal with their experiences in the session. Certain patterns of processing might facilitate or inhibit therapeutic change. Nowadays, the daily measurement is facilitated by the broad availability of Internet access at home and ubiquitous mobile devices. In recent years, the dynamic assessment approach has become increasingly popular. Using these new technologies, different variables that are relevant to psychotherapy have been studied, such as externalizing behaviour (Wright, Beltz, Gates, Molenaar, & Simms, Citation2015) or interpersonal processes (Roche, Pincus, Rebar, Conroy, & Ram, Citation2014) or symptoms (Fisher, Citation2015).

Network Analysis in Clinical Psychology

A relatively new and promising approach for modelling intraindividual differences comes from the field of network analysis. A large body of literature on the modelling of dynamic data as network structures emerged in recent years (Borsboom, Citation2017; Fried et al., Citation2017). In a recent review of literature, Borsboom (Citation2017) proposed a “network theory of mental disorders.” There are many current examples of attempts to make dynamic data from the clinical context usable. Kroeze et al. (Citation2017) showed how personalized feedback can motivate treatment-resistant patients to accept interventions better. However, network modelling studies focused almost solely on symptoms, which led researchers to propose the inclusion of other variables in networks (Jones, Heeren, & McNally, Citation2017). First studies on non-symptom variables in network models of psychopathology included several variables that were hypothesized to play a causal role in psychopathology. Isvoranu et al. (Citation2017) included childhood trauma in symptom networks of psychosis and showed possible influences of traumatic experiences on the probability of developing psychotic symptoms. Hoorelbeke, Marchetti, De Schryver, and Koster (Citation2016) investigated risk and resilience factors in depression and showed that resilience is a central hub in symptom networks of depression that suppresses symptoms and simultaneously promotes adaptive emotion regulation. Heeren and McNally (Citation2016) included a measure of attentional bias in their social anxiety network models, showing its role in maintaining social anxiety symptomatology. In this study, a new aspect in the treatment of mental health disorders will be considered to expand the spectrum of aspects relevant for psychotherapy. For psychotherapy process research, network analysis is likely to offer new insights on how patients process their treatments. The aim of this study is to combine the promising theoretical model of intersessional processes with modern methods of Ecological Momentary Assessment. Network analyses will be used to investigate the temporal dynamics of these processes in high temporal resolution.

The paper is structured as follows: first, we will infer the network representing the temporal dynamics of intersession processes. Second, we will perform a centrality analysis on the inferred network to interpret the role of different ISP.

Method

Design and Recruitment Process

22 courses of dyadic psychotherapy were selected from a dataset aggregated from two projects carried out between 2015 and 2017. These cases were selected based on data availability Patients who had answered the questionnaire for at least 21 consecutive days were selected. The data from the two projects were aggregated to maximize the statistical power of the group model. The first project was a pilot study in which the evaluation of ISPs with outpatients was tested. In this project the patients were referred by their therapists. The resident therapists were contacted with letters informing them about study goals and methods and asking them to contact the researchers when they were ready to refer patients. The therapists then contacted their clients and provided them with the contact details of the research group. The participating patients were then contacted and interviewed with an online questionnaire on demographics, their primary diagnoses, treatment duration, number of sessions and the theoretical approach of their therapists. The number of therapy sessions at the beginning of the study could be chosen from a menu ranging from 0 to 100 in steps of 10 (e.g., 0, less than 10, 11–20, 21–30, etc., with the last category being “more than 100”). Therapists with all legally recognized approaches were contacted. These approaches include various psychodynamic approaches, humanistic and client-centred therapy, systemic therapy, and cognitive-behavioural therapy.

The second project was a study conducted at the University of Salzburg’s research ambulance. In this project, patients contacting the ambulance were directly asked for participation in this study. Patients willing to participate were met for a diagnostic interview to determine their diagnosis.

A German translation of the “Unified Protocol,” a transdiagnostic, cognitive-behavioural treatment manual (Barlow, Citation2011) was used in all treatments. The manual consists of eight different treatment modules, including motivational interviewing, psychoeducation, cognitive reappraisal, mindfulness exercises, exposure, and relapse prevention. It was developed to develop an effective, uniform treatment method for all disorders whose central problem lies in dealing with emotions. These include anxiety disorders, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD. The translator commissioned by the publisher has made the German version of the manual available to the authors.

Patients suffering from psychosis, bipolar disorder and current substance abuse or addiction were excluded. In the second project, only patients suffering from depression, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and/or obsessive-compulsive disorder were recruited.

Additionally, patients completed the German version of the SCL-27 (Hardt, Egle, Kappis, Hessel, & Brähler, Citation2004) at intake and once every week in the first project. In the second project, patients received the PHQ-9 (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, Citation2001) and the GAD-7 (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, Citation2006, p. 7) together with the daily ISP scale, as well as the GHQ-12 at intake. Symptom data will not be included in the reported analyses due to lack of statistical power with increasing items in the group-level network analysis.

In both projects, the same daily measure of intersession processes was used. Courses with a length of at least three weeks (20 days) containing at least three sessions were selected based on availability. The mean length of courses was 46.9 days (SD = 10.38). Nine patients were selected from the first project’s data set while 13 patients were selected from the second project. Data from subjects who completed more than 21 daily questionnaires were included in the study. Overall, 22 participants (three male, 19 female) were included. Patient’s mean age was 28.95 years (SD = 8.60). Client characteristics, including symptom severity at intake, are summarized in Appendix 1. Age, sex, diagnosis, and therapy characteristics (approach and number of therapy sessions undergone at the beginning of study) were measured with an online demographics questionnaire. As compensation for participation in the study, feedback sessions were offered in which participants could review their process data together with a member of the research group. Study procedure and aims were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the University of Salzburg.

Table I. Means and standard deviations of all items in the short intersession process questionnaire averaged over all persons and time points.

Materials and Procedures

Short Intersession Process Scale

A short questionnaire with 10 items was generated to measure intersession processes. Item content was chosen so that it related to the content dimensions found in a principal component analysis of the German version of the Intersession Experience Questionnaire (IEQ) by Hartmann, Orlinsky, Geller, and Zeeck (Citation2003). Items with significant (>.30) primary factor loadings were selected and their formulation was adapted for daily measurements. The items were selected in such a way that they cover the original IEQ factors in terms of content but can also be interpreted individually. The items can be grouped into two rationally constructed scales corresponding to the three content dimensions (item group C) that Hartmann et al. (Citation2003) have found. Reflecting treatment (containing three items) measures thoughts about the patient’s behaviour towards psychotherapy. This is an indicator of the degree to which a patient is integrated into the boundary conditions of his therapy, like session scheduling or future sessions’ contents. Relationship processes (containing two items) indicates the frequency of thoughts involving the therapist, indicating a desire for contact. Problem-solving contains three items remembering therapy contents and applying them in patients’ daily routine. In addition, two scales with individual items were added that correspond to the two emotional dimensions of IEQ. These measure positive and negative emotions in relation to the therapy. Instead of asking for single emotions, examples of positive (relief, hope, confidence, security) and negative (anxiety, frustration, sadness, hurt) emotions taken from the IEQ were included in the item text. Emotions with highest factor loadings were chosen as examples. Appendix 2 contains the scales and their respective items. The intersession questionnaire was completed daily. Participants received reminders via E-mail or text messages sent to their mobile phones, including a link to their daily questionnaire. Reminding times could be chosen individually by the participants and were typically set to the late afternoon or evening. Items were rated on a 0 (not at all) to 100 (all the time) scale with steps of one point. All process data were recorded using the DynAMo software package (Kaiser & Laireiter, Citation2017). Patients completed an average of 46.9 (SD = 10.38, range 24–63) daily assessments of the scale, resulting in a grand total of 938 observations.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Gnu R . Network modelling, analysis, and plotting were performed using the mlVAR, qgraph, and networktools packages (Epskamp, Bringmann, & F, Citation2017; Epskamp, Cramer, Waldorp, Schmittmann, & Borsboom, Citation2012; Jones, Citation2017)

Network analysis

Multilevel vector autoregressive (mlVAR) models were estimated for the complete data set. In this model the temporal dynamics of the 10 items is represented by a vector autoregressive (VAR) model. The dependent variable at time t is predicted from previous values (t−1) of all variables. The number of preceding values used as predictors (“lags”) can vary. In the present study, a model with one lag (t−1) was preferred to models including two (t−2) or three lags (t−3), as this model resulted in the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for all variables, indicating the best model fit. The dependent variables in this study are the values of all 10 items of the Intersession short scale on the previous day. A multilevel VAR model combines individual VAR models estimated for every patient and consists of fixed (average) and random (individual) effects. In the present study, only fixed effects were estimated due to the relatively short time series. Each ISP item was used as a dependent variable once, so 10 different mlVAR models were estimated. mlVAR models can be estimated for stationary data only, meaning that a time series fluctuates around a non-changing mean value. KPSS tests (Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt, & Shin, Citation1992) were performed for individual time series. If this test is significant, a time series contains a positive or negative trend and is thus non-stationary. All time series with significant non-stationarity were trend adjusted by subtracting the linear trend component from the time series. Additionally, cubic spline interpolation was applied to all time series. This was done to generate equally-spaced time series when daily questionnaires were not equidistant due to delays in handling time or to missing data. All 10 intersession process items were included in the models. In addition, a counter variable was included that indicates the days since the last therapy session. This way, a possible cyclical course of the intersession processes resulting from the influence of the therapy sessions was to be examined.

When mlVAR models are estimated, their results can be visualized as network graphs. In these graphs, intersession process items are represented as nodes, while edges show how different process items influence each other over time (temporal network) and how they are connected to each other at one point in time (contemporary network). Using the qgraph package, graphs of estimated networks of intersession processes were created. Nodes that have strong connections were placed closer to each other using the algorithm by Fruchterman and Reingold (Citation1991). Edges represent fixed (average) effects of the influence of one item on the other. Because ISP were measured over time, connections can be interpreted as approximating causal influence as defined by Granger (Citation1969). The stronger the relationship between nodes, the thicker the edge connecting them.

In network analysis, centrality analysis can be performed to determine the relative importance or influence of a specific node. This is helpful for interpreting results of these analyses especially if networks contain many significant associations because centrality indices can serve as a summary of findings in a network. Analyses were performed by calculating different parameters of centrality: “outstrength,” instrength, and “betweenness.” Outstrength indicates how many outgoing arrows an item has and how strong the outgoing influences are. Items with high outstrength send more information to the network. Instrength indicates how many incoming arrows a node receives from other nodes. The betweenness of a node indicates on how many paths between other nodes it is located. Nodes with high betweenness are important for transmitting information along the network.

Additionally, the one- and two-step expected influence (Robinaugh, Millner, & McNally, Citation2016) of nodes was calculated. The one-step expected influence is defined as the sum of all edges extending from a given node, while the two-step expected influence also includes nodes connected to the initial node. This measure was included because negative influences were expected in ISP networks. Expected influence can be viewed as an extension of outstrength by considering whether network edges are positive or negative. According to Robinaugh et al. (Citation2016), expected influence is considered more appropriate for analysing networks containing edges with negative weight.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Mean scores and standard deviations of intersession process items are summarized in . All items showed a high degree of variation. Sources of variance will be analysed in the next session.

Missing Data

The mean percentage of missing daily questionnaire data was 10.84 (SD = 9.63) and ranged from 0 to 34.57.

Network Analysis

Graphical representation

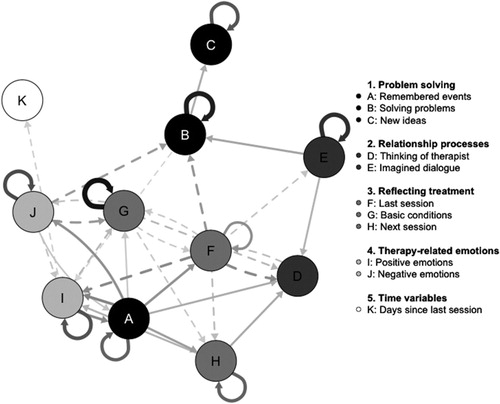

shows the estimated network of the dynamics between intersession process item scores after applying significance level correction. Solid edges show positive associations of item scores from one day on item scores on the next day while dashed edges show negative associations. For example, an increase of the item score “imagined dialogue” on one day predicts an increase of the item score of “solving problems.” On the other hand, an increase of negative therapy-related emotions predicts a lower score of “solving problems.” Most items have significant autoregressive components, indicating a certain temporal stability of scores over time. The cyclic time variable did not have any influence in the temporal network.

Figure 1 .#Network of time-lagged associations of intersession processes. Only edges that surpass the FDR-corrected significance level are visualized. Thicker, darker edges represent stronger connections. Solid edges indicate positive influences while dashed edges indicate negative influences.

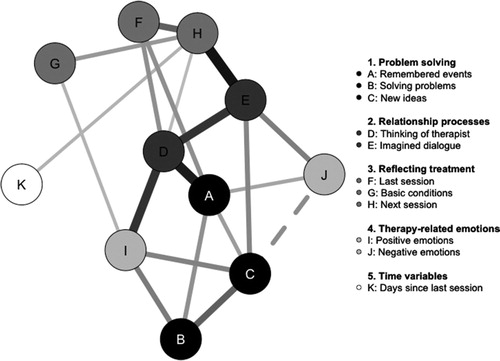

In , partial correlations of item scores on the same day are visualized. As in the time-lagged association network, solid edges indicate a positive association while dashed edges represent a negative association. For example, patients who imagined dialogues with their therapists (node E) also reflected on new ideas for session content on the same day (node H). There was only one negative association in the contemporaneous network: patients reporting more negative treatment-related emotions (node J) report less new ideas concerning past session content (node C). A positive association was observed between nodes K and H, indicating that thoughts concerning the next session become more frequent with increased temporal distance to the last therapy session.

Figure 2. Network of contemporaneous associations of intersession processes. Only edges that surpass the FDR-corrected significance level are visualized. Thicker, darker edges represent stronger connections. Solid edges indicate positive correlations while dashed edges indicate negative correlations.

Correlation coefficients for both the time-lagged and the contemporaneous network are listed in Appendix 3 and 4.

Centrality analysis

Centrality measures for the time-lagged network are summarized in . These scores allow inferences on the causal structure of intersession experience. Both the “Remembered events” and the “Last session” items have a relatively high outstrength, meaning that high scores on these items are likely to increase item scores in the rest of the network on subsequent days. On the other hand, the items “thinking of therapist” and “positive emotions” have relatively high instrength scores, indicating that high scores on these items are the result of another item’s influence. The betweenness scores are highest for nodes that are important for transferring information along the network because they link nodes to each other. The “last session” and “positive emotions” items are an example for this. Expected influence scores add to this information by indicating the direction of a node’s influence. This is especially helpful when interpreting the outstrength of items. “Remembered events” has a high positive expected influence, so its strong influence on other nodes is positive. An increase in this item predicts an increase of scores in connected nodes. Conversely, the “last session” item has a high outstrength, too, but its expected influence scores are negative. This means that its influence on connected nodes is negative.

Table II. Centrality measures for the time-lagged network of intersession process items and distance to the last therapy session. The higher a centrality index, the stronger the influence of the item in the network.

Similar interpretations are possible for the centrality measures for the contemporaneous network summarized in . Even though inferences on the direction of influences cannot be made in this kind of network, relationship processes were identified to be most influential in this network, and most strongly connected to other nodes. Epskamp and Fried (Citation2016) argue that partial contemporaneous correlations in networks can serve as exploratory indicators of causal influence (Appendix 4). Thus, this network still conveys important information about the “intraday” influence among intersession processes.

Table III. Centrality measures for the contemporaneous network of intersession process items and distance to the last therapy session. The higher a centrality index, the stronger the influence of the item in the network.

Discussion

We successfully derived a network structure of daily reports on intersession processes, showing significant temporal and contemporaneous effects and association. This can be considered a first look into the dynamics of intersession processes in ambulatory psychotherapies.

The most influential nodes in the estimated temporal network were both related to reflection on the last therapy session. The first one asked if the patient “remembered or thought about events in the last session,” was shown to increase the intensity of other ISP items, as indicated by its high positive expected influence. To a lesser degree, reflection on what to address in the next session had the same function.

Another item that addressed session content, asking if the patient thought about anything that they “could not express freely in the last session,” predicts a decrease in ISP intensity. This item’s content describes a more critical engagement with the last session and could be an indicator of negative session evaluation, of frustration or anxiety. If patients report thoughts on basic conditions of their therapies, this predicted lower ISP intensity as well. It is conceivable that a patient with a high value for this item is currently busy with a postponed or cancelled therapy session. Problems with the payment of the sessions are also conceivable. Interestingly, in-session hindering events have also been associated with basic conditions like time and the pace of treatment in a qualitative study by Richards and Timulak (Citation2012). Negative treatment-related emotions suppressed ISP activity as well, but to a much lesser extent than other items with negative expected influence.

The node, which stands for positive emotions, had positive and negative influences on other nodes. However, the affected nodes had a positive influence in the network. This is reflected by the low step-1 expected influence and the high step-2 expected influence of positive emotions. This node also has a high “betweenness” score, indicating that it is a “bridge node” and thus relays information across the network. Negative treatment-related emotions suppress other ISP scores in the first step while the connected nodes mainly have a positive influence on the network. Positive treatment-related emotions predicted favourable outcomes in the study conducted by Zeeck and Hartmann (Citation2005) while negative emotions predicted poorer outcome. At the day-to-day level, we found negative treatment-related emotions to have a damping function in the network model, decreasing the occurrence of other processes. This damping influence is in in alignment with previous findings stating that negative treatment-related emotions predicted unfavourable treatment outcomes (Hartmann et al., Citation2016).

Relationship-related processes had only a weak influence in the temporal network. This could due to the relatively high proportion of CBT courses in our sample, which is more focused on behavioural change and less on working in the therapeutic relationship. However, those aspects of the ISP were highly influential in the contemporaneous network, showing high betweenness and strength scores. The causal direction cannot be determined in this network, but it is likely that relationship processes play an important role in intra-day ISP. Future studies could increase the sampling rate to further examine the role of this processes, as more frequent recreation of therapeutic dialogue between sessions while undergoing therapy was found to predict treatment outcome (Zeeck & Hartmann, Citation2005). Adding to this finding, Hartmann et al. (Citation2016) showed that recreating dialogues was predictive of negative treatment outcomes when they co-occurred with negative emotions.

The integration of our results with those from studies using more traditional methods such as cross-sectional analyses or multilevel models for weekly measurements shows that both approaches are important. Our data complement previous results by providing a first look at the daily dynamics of intersession processes. Given that we found positive treatment-related emotions to facilitate the propagation of information along the network, this could be the mechanism of change that is key for successful therapies.

The “problem-solving” aspect of the ISP was not influential in the network, but was strongly influenced by other nodes, reflected by its instrength. Processes like remembering or applying session content can be considered an indicator for the successful transfer of therapy contents into a patient’s everyday life, including therapeutic homework (Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, Citation2000). However, because outcome data were not available in our dataset, this is merely a speculation. Future studies could explore the relationship of these fine mechanics to treatment outcome or compare the network structures of successful and non-successful therapies. Soon, process monitoring systems based on these findings could support therapists in planning and adjusting their treatments.

Limitations

There is several limitations to this study. The focus of this study was within-person modelling of intersession processes. Thus, the number of participants was low when compared to the number of time points and our results should be generalized only with caution. Due to the exploratory nature of this study, the sample was selected based on the availability of data. For this reason, the data contain participants from different treatment stages and are generally susceptible to sampling error. For example, male participants were rare in this sample. It could be argued that this accurately represents the number of men undergoing ambulatory psychotherapy compared to women. In previous studies on the intersession process (Hartmann et al., Citation2003, Citation2011), male participants formed the minority as well. The tendency of men to be reluctant in recognizing mental health problems has been established for decades (e.g., Horwitz, Citation1977). Additionally, the average amount of time points allowed patients to attain only between four and nine sessions of psychotherapy. Thus, the data should not be interpreted as representative of a whole course of psychotherapy.

Psychometrically, it is debatable whether single-item scales are useful to measure treatment-related emotions. While single-item measures of positive and negative affect were shown to be useful (Hoeppner, Kelly, Urbanoski, & Slaymaker, Citation2011) further data on the validity of the proposed treatment-related emotion items are needed.

The daily questionnaires measuring ISP could have influenced ISP frequency and intensity as well. Patients might not have any thoughts about their therapist at all if they were never asked about it. Processes that might take place in a more implicit (or unconscious) manner could become explicit when measured.

Outlook and Future Work

As already suggested by Jones et al. (Citation2017) for network models in clinical psychology, this study goes beyond symptoms. Future studies with larger, more balanced datasets should examine whether intersession processes play a causal role in reducing symptoms. This can provide important insights into the mechanisms of action of psychotherapy. Monitoring of intersession processes could also improve the understanding of sudden symptom reductions (sudden gains, Tang and DeRubeis, Citation1999). These sudden changes are in turn predictive of overall therapy outcome (Aderka et al., Citation2012). Sudden gains have been identified using post-session questionnaires and were linked to patient-rated quality of the therapeutic relationship (Lutz et al., Citation2013).

A warm interpersonal style reported by therapists is a positive predictor of patient-reported outcomes, while a lack of empathy and negative emotions towards their patients were negative predictors (Nissen-Lie, Havik, Høglend, Monsen, & Rønnestad, Citation2013). It can be speculated that these global therapeutic orientations can lead to specific dynamics in intersession processes. If a therapist engages the patient in a warm and empathic way, this might foster positive treatment-related emotions, while the opposite could be true if negative personal reactions dominate the treatment sessions.

Future studies could relate network centrality of intersession processes to other important variables in psychotherapy. This would require larger samples, so that individual network models could be derived, but possibly yields interesting findings. For example, the centrality of negative treatment-related emotions could be related to less favourable outcomes. Conversely, an idiographic approach could be taken, with single case evaluations or small-N designs that contrast intensive repeated measurements of intersession processes and symptoms with qualitative data on details of the treatment course. This is advisable especially for the study of longer and more complex treatments like personality disorders. It could be speculated that the temporal dynamics (i.e., the correlational structure) change with the course of treatment. Thus, the application of Mixed Graphical Models (Haslbeck & Waldorp, Citation2015) to longer time series of ISP could prove to be a fruitful undertaking.

In conclusion, it can be said that researchers with daily surveys of the proposed items can improve the temporal resolution with which change processes in psychotherapy can be observed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nadine Scharnowski (University of Kassel, Germany) for providing us with the German translation of the Unified Protocol.

ORCID

Tim Kaiser http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6307-5347

References

- Aderka, I. M, Nickerson, A, Bøe, H. J, & Hofmann, S. G. (2012). Sudden gains during psychological treatments of anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 80(1), 93–101. 10.1037/a0026455

- Barlow, D. H. (ed.). (2011). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Borsboom, D. (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 5–13. doi: 10.1002/wps.20375

- Cronbach, L. J., & Furby, L. (1970). How we should measure “change”: Or should we? Psychological Bulletin, 74(1), 68–80. doi: 10.1037/h0029382

- Epskamp, S., Bringmann, M. K. D., & F, L. (2017). mlVAR: Multi-Level Vector Autoregression (Version 0.4). Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mlVAR.

- Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). QGraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(4), 1–18. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i04

- Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2016). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. ArXiv:1607.01367 [Stat]. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.01367.

- Fisher, A. J. (2015). Toward a dynamic model of psychological assessment: Implications for personalized care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(4), 825–836. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000026

- Fried, E. I., van Borkulo, C. D., Cramer, A. O. J., Boschloo, L., Schoevers, R. A., & Borsboom, D. (2017). Mental disorders as networks of problems: A review of recent insights. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z

- Fruchterman, T. M., & Reingold, E. M. (1991). Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Software: Practice and Experience, 21(11), 1129–1164.

- Granger, C. W. J. (1969). Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica, 37(3), 424–438. doi: 10.2307/1912791

- Hardt, J., Egle, U. T., Kappis, B., Hessel, A., & Brähler, E. (2004). Die Symptom-Checkliste SCL-27. PPmP-Psychotherapiė Psychosomatik˙ Medizinische Psychologie, 54(05), 214–223.

- Hartmann, A., Orlinsky, D. E., Geller, J. D., & Zeeck, A. (2003). [The Intersession Questionnaire—an inventory for the measurement of patients’ processing of psychotherapy between sessions]. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 53(11), 464–468.

- Hartmann, A., Orlinsky, D., Weber, S., Sandholz, A., & Zeeck, A. (2010). Session and intersession experience related to treatment outcome in bulimia nervosa. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47(3), 355–370. doi: 10.1037/a0021166

- Hartmann, A., Orlinsky, D., & Zeeck, A. (2011). The structure of intersession experience in psychotherapy and its relation to the therapeutic alliance. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(10), 1044–1063. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20826

- Hartmann, A., Zeeck, A., Herzog, W., Wild, B., de Zwaan, M., Herpertz, S., & Zipfel, S. (2016). The intersession process in psychotherapy for anorexia nervosa: Characteristics and relation to outcome: intersession process and outcome in anorexia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Psychology, doi: 10.1002/jclp.22293

- Haslbeck, J. M. B., & Waldorp, L. J. (2015). mgm: Estimating time-varying mixed graphical models in high-dimensional data. ArXiv, 1510.06871. [Stat]. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1510.06871.

- Heeren, A., & McNally, R. J. (2016). An integrative network approach to social anxiety disorder: The complex dynamic interplay among attentional bias for threat, attentional control, and symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 42, 95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.06.009

- Hoeppner, B. B., Kelly, J. F., Urbanoski, K. A., & Slaymaker, V. (2011). Comparative utility of a single-item vs. multiple-item measure of self-efficacy in predicting relapse among young adults. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 41(3), 305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.04.005

- Hoorelbeke, K., Marchetti, I., De Schryver, M., & Koster, E. H. W. (2016). The interplay between cognitive risk and resilience factors in remitted depression: A network analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 195, 96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.001

- Horwitz, A. (1977). The pathways into psychiatric treatment: Some differences between men and women. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 18(2), 169–178. doi: 10.2307/2955380

- Isvoranu, A.-M., Borkulo, V., C, D., Boyette, L.-L., Wigman, J. T. W., Vinkers, C. H., & Borsboom, D. (2017). A network approach to psychosis: Pathways between childhood trauma and psychotic symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(1), 187–196. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw055

- Jones, P. (2017). Networktools: Tools for identifying important nodes in networks. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=networktools

- Jones, P. J., Heeren, A., & McNally, R. J. (2017). Commentary: A network theory of mental disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01305

- Kaiser, T., & Laireiter, A. R. (2017). DynAMo: A Modular Platform for Monitoring Process, Outcome, and Algorithm-Based Treatment Planning in Psychotherapy. JMIR Medical Informatics, 5(3), e20. doi: 10.2196/medinform.6808

- Kazantzis, N., Deane, F. P., & Ronan, K. R. (2000). Homework assignments in cognitive and behavioral therapy: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7(2), 189–202.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Kroeze, R., van der Veen, D. C., Servaas, M. N., Bastiaansen, J. A., Voshaar, R. C. O., Borsboom, D., & Riese, H. (2017). Personalized feedback on symptom dynamics of psychopathology: A proof-of-principle study. Journal for Person-Oriented Research, 3(1), 1–11. doi: 10.17505/jpor.2017.01

- Kwiatkowski, D., Phillips, P. C., Schmidt, P., & Shin, Y. (1992). Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root: How sure are we that economic time series have a unit root? Journal of Econometrics, 54(1–3), 159–178. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(92)90104-Y

- Lutz, W, Ehrlich, T, Rubel, J, Hallwachs, N, Röttger, M A, Jorasz, C, & Mocanu, S. (2013). The ups and downs of psychotherapy: Sudden gains and sudden losses identified with session reports. Psychotherapy Research, 23(1), 14–24. doi:10.1080/10503307.2012.693837

- Molenaar, P. C. M. (2004). A Manifesto on Psychology as Idiographic Science: Bringing the Person Back Into Scientific Psychology, This Time Forever. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives, 2(4), 201–218. doi: 10.1207/s15366359mea0204_1

- Molenaar, P. C. M. (2013). On the necessity to use person-specific data analysis approaches in psychology. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 10(1), 29–39. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2012.747435

- Nissen-Lie, H. A., Havik, O. E., Høglend, P. A., Monsen, J. T., & Rønnestad, M. H. (2013). The contribution of the quality of therapists’ personal lives to the development of the working alliance. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 483–495. doi: 10.1037/a0033643

- Orlinsky, D. E., Geller, J. D., Tarragona, M., & Farber, B. (1993). Patients’ representations of psychotherapy: A new focus for psychodynamic research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 596–610. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.4.596

- Richards, D., & Timulak, L. (2012). Client-identified helpful and hindering events in therapist-delivered vs. self-administered online cognitive-behavioural treatments for depression in college students. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 25(3), 251–262. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2012.703129

- Robinaugh, D. J., Millner, A. J., & McNally, R. J. (2016). Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 747–757. doi: 10.1037/abn0000181

- Roche, M. J., Pincus, A. L., Rebar, A. L., Conroy, D. E., & Ram, N. (2014). Enriching psychological assessment using a person-specific analysis of interpersonal processes in daily life. Assessment, 21, doi: 10.1177/1073191114540320

- Schröder, T., Wiseman, H., & Orlinsky, D. (2009). “You were always on my mind”: Therapists’ intersession experiences in relation to their therapeutic practice, professional characteristics, and quality of life. Psychotherapy Research, 19(1), 42–53. doi: 10.1080/10503300802326053

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Tang, T. Z, & DeRubeis, R. J. (1999). Sudden gains and critical sessions in cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 67(6), 894–904. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.894

- Tschacher, W., & Ramseyer, F. (2009). Modeling psychotherapy process by time-series panel analysis (TSPA). Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 469–481. doi: 10.1080/10503300802654496

- Wright, A. G. C., Beltz, A. M., Gates, K. M., Molenaar, P. C. M., & Simms, L. J. (2015). Examining the dynamic structure of daily internalizing and externalizing behavior at multiple levels of analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01914

- Zeeck, A., & Hartmann, A. (2005). Relating therapeutic process to outcome: Are there predictors for the short-term course in anorexic patients? European Eating Disorders Review, 13(4), 245–254. doi: 10.1002/erv.646

- Zeeck, A., Hartmann, A., Wild, B., De Zwaan, M., Herpertz, S., & Burgmer, M. … The Antop Study Group (2016). How do patients with anorexia nervosa “process” psychotherapy between sessions? A comparison of cognitive–behavioral and psychodynamic interventions. Psychotherapy Research, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2016.1252866

Appendices

Appendix 1 Overview of participants including recruiting source (private practice vs. university centre), basic demographic data, diagnoses, treatment approach and number of therapy sessions already undergone before the beginning of EMA assessments

Appendix 2. Proposed scales and items used in the short daily intersession questionnaire

Appendix 3. Partial directed correlation matrix of intersession process items and temporal distance to the last session

Appendix 4. Partial contemporaneous correlation matrix of intersession process items