?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective: Evidence is inconclusive on whether variability in alliance ratings within or between therapists is a better predictor of treatment outcome. The objective of the present study was to explore between and within patient and therapist variability in alliance ratings, reciprocity among them, and their significance for treatment outcome. Method: A large primary care psychotherapy sample was used. Patient and therapist ratings of the working alliance at session three and patient ratings of psychological distress pre–post were used for analyses. A one-with-many analytical design was used in order to address problems associated with nonindependence. Results: Within-therapist variation in alliance ratings accounted for larger shares of the total variance than between-therapist variation in both therapist and patient ratings. Associations between averaged patient and therapist ratings of the alliance for the individual therapists and their average treatment outcome were weak but the associations between specific alliance ratings and treatment outcome within therapies were strong. Conclusions: The results indicated a substantial dyadic reciprocity in alliance ratings. Within-therapist variation in alliance was a better predictor of treatment outcome than between-therapist variation in alliance ratings.

Clinical and methodological significance: The variation in alliance between patients within therapists seems to influence outcome. Therapists should be observant of such variability. The one-with-many design partitions alliance ratings meaningfully.

A moderate but consistent association between the quality of the working alliance in psychological treatment and treatment outcome has been found in many studies (Flückiger, Del Re, Wampold, & Horvath, Citation2018; Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger, & Symonds, Citation2011). These findings are valid across rating perspectives, treatment orientation, and treatment modality (Wampold & Imel, Citation2015). Several issues, however, are still unclear concerning the relationship between alliance and outcome. One of the most salient is the significance of the mutual congruence of the participants’ ratings.

Most studies of the alliance-treatment outcome association have analyzed the relationship between the patient’s ratings of the working alliance and outcome. In the meta-analysis by Flückiger et al. (Citation2018), there were 223 studies of patient-rated alliance and 40 of therapist-rated alliance. In this study, the correlations between alliance and outcome did not differ between patient ratings and therapist ratings (r = .25 vs. r = .22). A number of studies have used both patient and therapist ratings in the same analyses (Atzil-Slonim et al., Citation2015; Hartmann, Joos, Orlinsky, & Zeeck, Citation2015; Kivlighan, Hill, Gelso, & Baumann, Citation2016; Marmarosh & Kivlighan, Citation2012). Most of these studies found that patients’ ratings have stronger associations with treatment outcome (Gullo, Lo Coco, & Gelso, Citation2012; Huppert et al., Citation2014; Marcus, Kashy, & Baldwin, Citation2009). Only a few studies have assessed the contribution of one rater perspective when the contribution of the other was adjusted for. Zilcha-Mano et al. (Citation2015) found that the therapist’s ratings of the alliance only marginally influenced outcome four sessions later, when the contribution of the patient’s rating of the alliance was adjusted for. However, Falkenström, Ekeblad, and Holmqvist (Citation2016) found a stronger effect of therapist-reported than patient-reported alliance on symptom change at the following session.

These analyses do not, however, take into account the fact that there is dependence between the therapist’s and the patient’s perspectives on the alliance, as the participants usually communicate about their collaboration (Safran & Muran, Citation2000). In the therapeutic interaction, the therapist’s behavior and perception is continually influenced by the patient’s and vice versa (Lingiardi, Holmqvist, & Safran, Citation2016). Adjusting statistically for the contribution of one source of variation does not imply that the sequential mutual influence is taken into account. Even if the participants do not have access to each other’s ratings, it is probable that they are aware at least to some extent of the other’s perception of the working alliance. A patient who has a very positive perception of the alliance will likely influence the therapist’s view of the alliance; a therapist who suddenly perceives the working alliance as impaired will color the patient’s perception of the alliance.

In the Social Relations Model described by Kenny (SMR; Kenny, Citation1994) mutual perception and behavior is thought of as influenced by three sources: the perceiver, the partner, and the relationship. In order to disentangle the variances associated with each source, the study must include ratings from several perceivers about several partners, like in a group setting where everybody reports perceptions about everybody else. However, when studying working alliance in psychotherapy, the positions of therapist and patient entail an obvious difference (Bachelor, Citation2013; Hartmann et al., Citation2015). The patient only has one therapist whereas the therapist usually has a number of patients. Thus, there may be ratings by one therapist about the quality of the working alliance with many of his or her patients but each patient only rates his or her alliance with one therapist. This means that the therapist may compare the quality of the alliance in the specific treatment with a number of therapeutic relationships whereas the patient usually only compares between different sessions with the same therapist.

These issues are of psychological as well as methodological interest. Marcus et al. (Citation2009) tried to address some of the problems that arise in this situation. Using a modification of SRM (Kenny, Citation1994; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, Citation2006), they attempted to adjust for the unbalanced situation that the therapist rates many relationships and the patient only one by disentangle different sources of variance in ratings. They called their modified design “one-with-many” to reflect this difference in perspectives between therapists and patients (where one therapist rates many relationships). In the one-with-many model four sources of variance (or effects) are assessed:

the therapist partner effect (do patients report similar alliances with their therapist?)

patient relationship effect (do patients report specific alliances with their therapist?)

the therapist perceiver effect (do therapists report similar alliances across their patients?)

the therapist relationship effect (do therapists report specific alliances with patients?).

In addition, the one-with-many model allows for two types of reciprocity analyses. In the first, called generalized reciprocity, the correlations between the average ratings of perceivers and partners are analysed (e.g., the therapist perceiver effect correlated with the therapist partner effect). If the therapist, for instance, rates the alliance as weak with all patients, does that correspond with weak alliance ratings from all his or her patients? Generalized reciprocity reflects to what extent the average of the ratings of one party, e.g., the therapist, is congruent with the average of the ratings from the other party, e.g., the patients. Dyadic reciprocity, on the other hand, assesses the strength of association in a specific relationship (the patient relationship effect correlated with the therapist relationship effect). Does the therapist’s particularly strong alliance with a specific patient correspond with stronger alliance ratings from this patient in comparison with ratings from the therapist’s other patients?

As noted above, there are some limitations in the one-with-many model. For example, since the patient only rates alliance with one therapist we do not know whether the patient’s ratings would be similar across different therapists (the patient’s perceiver effect). Similarly, since there are no ratings from other therapists about the patient we cannot know to what extent other therapists would rate the alliance with the patient in a similar way (the patient’s partner effect). Thus, the therapist relationship effect will be confounded with the patient partner effect (since this effect cannot be assessed), and the patient relationship effect will be confounded with the patient perceiver effect (since this effect cannot be assessed). As a consequence, the dyadic reciprocity estimate will be attenuated since this estimate is the correlation between the therapist relationship effect with the patient relationship effect. However, Marcus et al. (Citation2009) suggested that even though the patient and therapist relationship effects are attenuated in this way, the correlation between the two might still be used as a conservative estimate of the degree of dyadic reciprocity.

By using one-with-many modeling it is possible to address a number of problems in psychotherapy research, particularly concerning independence of ratings. In most psychotherapy studies, data is nested and multilevel designs must be used. Most commonly, patients are nested within therapists. In the modified social relations design presented by Marcus et al. (Citation2009), the dependence among ratings is to some extent adjusted for. The interdependence in the data can for instance be used for separating the general reciprocity in the ratings from the unique dyadic ratings.

The main findings in Marcus et al. (Citation2009) were that the dyadic reciprocity accounted for a much larger share of the variance in alliance ratings than the average ratings. Specifically, the uniformity in ratings from patients about the same therapist (the therapist partner effect) was low. In addition, the therapist perceiver effect was considerable, implying that some therapists saw themselves as creating generally strong alliances whereas others did not. Also, the general reciprocity accounted for a very small part of the variance whereas the dyadic, unique relationship share was considerable. Thus, the raw correlation between therapists’ and patients’ alliance ratings (Tryon, Blackwell, & Hammel, Citation2007) is almost entirely due to the specific congruence in individual relationships.

An important question is of course whether the association between alliance and treatment outcome can be better understood with this analysis design. Several different multilevel models have been used for investigating whether variation in alliance within or between therapists is a more robust predictor of treatment outcome. Most studies have found that the association is generally accounted for by differences in patient-rated alliance between therapists but not by patients within therapists (Baldwin, Wampold, & Imel, Citation2007; Del Re, Flückiger, Horvath, Symonds, & Wampold, Citation2012; Kivlighan, Gelso, Ain, Hummel, & Markin, Citation2015; Zuroff, Kelly, Leybman, Blatt, & Wampold, Citation2010). However, by using one-with-many modeling, Marcus et al. (Citation2009) were able to reveal associations that may have been obscured in an earlier analysis of the same sample by Baldwin et al. (Citation2007). Both studies showed that differences in patients’ average alliance ratings towards therapists (the therapists’ partner effect) were significantly associated with outcome. However, Baldwin et al. (Citation2007) did not find significant associations between outcome and alliance within therapists. This was in contrast to the findings of Marcus et al. (Citation2009) who found that the relationship effect was associated with outcome. Thus, therapists who were rated by their patients as creating strong alliances did get better outcomes, but good outcomes were also found in therapies with therapists who did not usually create strong alliances but did so in a particular therapy (as rated by the patient).

The purpose of the present study was to use the same one-with-many modeling technique as Marcus et al. (Citation2009). The study by Marcus et al. (Citation2009) was carried out at a particular therapy service in a university setting with relatively young patients (mean age 23.1). Our study uses a large Swedish primary care psychotherapy sample.

The aim of the study was to explore the shares of variance between the different elements of the working alliance and to analyze the association between these alliance elements and outcome. More specifically, we investigated the proportion of variance accounted for by the therapist partner effect and the patient relationship effect in the patients’ alliance ratings, as well as the proportion of variance accounted for by the therapist perceiver effect and the therapist relationship effect in the therapists’ alliance ratings. Furthermore, we studied the degree of dyadic reciprocity as well as the degree of generalized reciprocity in these ratings. Finally, we analyzed to what extent the therapist perceiver effect, therapist partner effect as well as the patient and therapist relationship effects predicted outcome. Alliance was the primary outcome measure in the study and was completed by both therapists and patients.

Method

Participants and Procedure

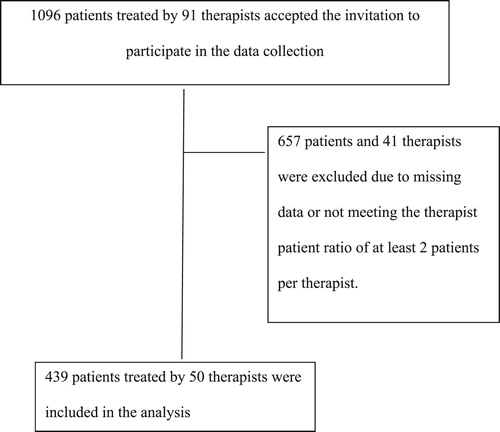

Data from two primary care service regions in Sweden, with a total population of about 600,000 people, was used in this study. In Sweden, primary care is the first line treatment for mild to moderate psychiatric disorders involving interventions such as psychotherapy, counseling, and/or medication. Therapists were asked to invite all patients who started treatment within a period of six months (November 2009 to April 2010) to participate in the study. In all, 1096 patients treated by 91 therapists accepted to participate and completed at least one measure of psychological distress. A demographic description of these patients is presented in . Due to missing data demographic information was available for 75% of the sample. The dataset has previously been used to study several psychotherapy concepts (Falkenström, Granström, & Holmqvist, Citation2013; Falkenström, Granström & Holmqvist, Citation2014; Falkenström, Hatcher & Holmqvist, Citation2015; Falkenström, Hatcher, Skjulsvik, Larsson, & Holmqvist, Citation2015; Falkenström, Josefsson, Berggren, & Holmqvist, Citation2016; Holmqvist, Ström, & Foldemo, Citation2014; Mechler & Holmqvist, Citation2016), but not for exploring between and within patient and therapist variability in alliance ratings, reciprocity among them, and their significance for treatment outcome.

Table I. Demographic information.

The most common therapy types were supportive therapy (30%), psychodynamic therapy (24%), and cognitive behavioral therapy (18%). Treatment was delivered as usual at each primary care unit. The most common basic professions were social worker (62%) or psychologist (28%). All participating patients gave informed consent. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Linköping (ref. M72-09). Most patients stopped treatment when they had reached a “good-enough level of functioning” but some dropped out prematurely due for instance to disappointment with treatment. To be included in the analyses both patients and therapists had to have completed a measure of working alliance collected directly after attending treatment session three and patients had to have completed a measure of psychological distress at intake and termination (see Measures). In addition, only cases where therapists had treated at least two patients were included in the analysis. A flow chart of the number of patients and therapists selected for analysis using these criteria is provided in . The median therapist caseload was eight patients (with a range of two to 25) and the median attended treatment sessions per patient was five (with a range of three to 29).

Since Marcus et al. (Citation2009) collected alliance data prior to the fourth therapy session both their and our samples included patients who had attended three treatment sessions before completing the alliance measure.

Instruments

The Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM)

CORE-OM (Evans et al., Citation2002) is a self-report measure consisting of 34 items measuring psychological distress experienced during the last week. The measure has a 5-point scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Most or all the time.” The items cover four major domains: well-being, problems, functioning, and risk (to self or others). In the present study, only the total score with a possible range between 0 and 4 was used. Higher scores indicate greater distress. The present study used the Swedish version (Elfström et al., Citation2012) with reported internal consistency of α = .93–.94 and test-retest reliability of .85. In this study, participants completed the CORE-OM at intake and termination. These ratings showed an internal consistency of α = .93, and α = .96, respectively.

Working Alliance Inventory (WAI)

WAI (Horvath & Greenberg, Citation1989) consists of three components: bond, task, and goal. The original instrument contained 36 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale and showed satisfactory reliability and validity. The current study used the 12-item revised version, WAI-SR for patient ratings (Hatcher & Gillaspy, Citation2006), and WAI-S for therapist ratings (Tracey & Kokotovic, Citation1989). The WAI-SR has shown adequate reliability and validity (Falkenström, Hatcher, & Holmqvist, Citation2015). In the present study, only the total score with a possible range between 1 and 7 was used. A higher score indicates a stronger working alliance. WAI ratings were completed by therapists and patients immediately after session three. The internal consistency of the WAI-SR and WAI-S ratings for the present study was α = .95 for both measures.

Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 24) was used for analyzing the data. Since alliance as the primary outcome measure was completed by both therapists and patients, a multivariate multilevel model based on the two-intercept approach (e.g., Baldwin, Imel, Braithwaite, & Atkins, Citation2014; Raudenbush, Brennan, & Barnett, Citation1995) was fitted to the data using the MIXED procedure. Parameter estimation was made using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) with an unstructured correlations structure in accordance with Marcus et al. (Citation2009). The correlation between variance components was used to investigate reciprocity in the working alliance ratings provided by the therapists and patients as depicted in Equation (1). Wald- z tests were used to determine the significance of the different variance components and their correlations.(1)

(1)

In Equation (1) i is the patient, j is the therapist, and k denotes whether the data was rated by the therapist (k = 1) or the patient (k = 2). b01j is the average of the working alliance ratings by therapist j, averaging across j’s patients, and b02j estimates the average of the working alliance ratings by therapist j’s patients. Te1ij is the unique part of therapist j’s rating of patient i after removing therapist j’s average (the error component). Pe2ij is the unique part of patient i’s rating of therapist j after removing therapist j’s average. a01 is the grand mean for therapists’ ratings and a02 is the grand mean for patients’ ratings. d1j is the individual deviance between the grand mean of therapists’ ratings and the working alliance ratings by therapist j, averaging across j’s patients. d2j is the individual deviance from the grand mean of patients’ ratings and the working alliance ratings by therapist j’s patients (Appendix A shows these variance components in relation to the social relations model).

The next step was to examine the relationship between working alliance and treatment outcome. The model used for this analysis is depicted in Equation (2).(2)

(2)

In line with Marcus et al. (Citation2009), treatment outcome was based on residualized change scores, which were calculated by using the CORE-OM scores at intake to predict CORE-OM scores at termination. The rationale for using residualized change scores was to control for the fact that more distressed patients could be assumed to have higher change rates due to personal rating liability or regression to the mean. Since a higher score on the CORE-OM form indicates greater distress, a negative residual indicates that the patient improved more than would be expected based on the intake score. Two outcome variables were then created from these residual scores. They were denoted as AvgCORE and IndCORE.

AvgCORE is a therapist-level variable measuring the average residual score across patients who were treated by the same therapist. This variable was used for examining (1) whether therapists whose patients, on average, improved more rated higher levels of working alliance across their patients and (2) whether these therapists tended to have patients who, on average, perceived higher levels of working alliance with their therapist.

The indCORE variable is a patient-level variable computed by subtracting the mean residual score for the therapist from the individual patient’s residual score. If this variable is negative it indicates that a specific patient improved more than other patients treated by the same therapist. This mean-deviated change variable was used to examine (1) whether therapists’ alliance ratings were more positive with patients who improved more than their typical patient and (2) whether alliance ratings from patients who improved more than their therapist’s typical patient were especially positive.

In this model, b01j estimates the relationship between the alliance ratings by therapist j and the residual score for therapist j’s patients. The a11AvgCOREj parameter estimates the average of this effect across therapists, addressing the question of whether patients who are seen by their therapist as forming stronger alliances tend to have a better treatment outcome.

The b12j parameter estimates the relationship between the alliance ratings by therapist j’s patients and the residual score for those patients, and so c02 estimates whether, averaging across therapists, patients who perceive stronger alliances than other patients seeing the same therapist have better therapeutic outcomes. The two random effects components, d3j and d4j, estimate whether the perceptions of alliance and treatment outcome vary from therapist to therapist. Wald t-tests were used to determine the significance of variation between therapists in the model.

Results

Variance Partitioning

The results indicate a non-significant therapist partner effect, with s2 = 0.06, z = 1.86, p > .05. Thus, the patients’ alliance ratings did not vary significantly among therapists and accounted for 7.1% of the total variance. In contrast, large and significant amounts of the variance in the patient-rated alliance scores (92.9%) could be attributed to the patient relationship effect (confounded by the patients’ perceiver effect and error variance components) with s2 = 0.84, z = 14.05, p < .01. In addition, the therapist perceiver effect accounted for a significant 45% of the total variance in therapist rated alliance, with s2 = 0.35, z = 4.13, p < .01. Thus, some therapists reported stronger alliances, on average, than other therapists. However, the major part of the variance in the therapist ratings (55% of the total variance) was due to the unique therapist relationship effect (confounded by the patients’ partner effect and error variance component), with s2 = 0.43, z = 13.92, p < .01. The variance partitioning for the patient-rated and therapist-rated versions of the WAI is reported in .

Table II. Variance partitioning.

The dyadic reciprocity correlation (patient-rating of the unique relationship aspect combined with therapist-rating of the unique relationship aspect) was statistically significant with r = .38, z = 8.73, p < .01. Therefore, if a therapist reported an especially strong working alliance with a particular patient (better than with his or her other patients), that patient was likely to report an especially strong alliance (better than those reported by the therapist’s other patients). The generalized reciprocity (perceiver–partner) correlation was also significant with r = .52, z = 2.61, p < .05. Thus, therapists who generally saw themselves as forming strong alliances with their patients had patients who reported stronger alliances. Estimates of dyadic and generalized correlation are reported in .

Table III. Estimates of dyadic and generalized reciprocity correlation session three.

Working Alliance and Treatment Outcome

The results showed that the therapist partner effect was not significantly associated with outcome: b = −.54, t(50) = −1.84, p > .05. Thus, therapists who had patients who, on average, saw them as establishing stronger working alliances (in reference to the average therapist) did not have better outcomes. Neither was the therapist perceiver effect significantly associated with outcome: b = .66, t(48) = 1.48, p > .05. This means that therapists who, on average, reported stronger working alliances in comparison with the average therapist did not have better outcome. The dyad-specific results indicate that both patient (b = −.51, t(393) = −6.34, p < .01) and therapist (b = −.37, t(386) = −6.44, p < .01) relationship effects were strongly associated with outcome. In other words, patients who reported a uniquely strong working alliance (relative to the ratings provided by their therapist’s other patients) had better treatment outcomes compared with other patients treated by the same therapist. Also, patients whose therapy sessions were seen as having a uniquely strong alliance by their therapists (relative to the therapists’ other patients) had better outcomes. The model parameter estimates of the analysis regarding the association between alliance and outcome are specified in .

Table IV. Parameter estimates for the association between alliance and outcome.

The treatment outcome variable (residualized change scores) had an estimated therapist variance of s2 τ = 0.02 and a residual variance of s2 ε = 0.302. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for this variable was .006, z = .29, p > .05.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to analyze proportions of variance in patients’ and therapists’ reciprocal ratings of the alliance and their associations with outcome. No significant therapist partner effect in the patients’ ratings (e.g., differences between therapists) was found, but a large patient relationship effect (e.g., variation in ratings made by different patients seeing the same therapist). There was a significant therapist perceiver effect in the therapists’ ratings (differences between therapists) as well as a large therapist relationship effect (e. g. variation in ratings made by the same therapist about the alliance with different patients). Both the dyadic reciprocity correlation and the generalized reciprocity correlation were significant. The results showed no significant association between therapist perceiver effect and outcome, nor was there any significant association between therapist partner effect and outcome. In contrast, both patient and therapist relationship effects were related to outcome. Thus, alliance and outcome were strongly related when analysed within each therapist but the average alliance scores for the therapists did not predict outcome.

The results of our study diverged from findings in Marcus et al. (Citation2009) concerning the relationship between alliance and outcome. Marcus et al. (Citation2009) showed that the therapist partner effect as well as the patient relationship effect predicted outcome but found no association between therapist perceiver effect or therapist relationship effect and outcome. As noted in the Introduction, several studies have found associations between working alliance and treatment outcome between therapists but not by patients within therapists (Baldwin et al., Citation2007; Del Re et al., Citation2012; Kivlighan et al., Citation2015; Zuroff et al., Citation2010). A few studies have found that both between- and within-therapist variation was related to outcome (Marcus et al., Citation2009; Marcus, Kashy, Wintersteen, & Diamond, Citation2011). In contrast, the results in the present study indicated that within-therapist variation was more important for the relation between the working alliance and treatment outcome.

These findings have clinical implications. If the association between alliance and outcome is primarily explained by differences in alliance ratings between therapists, research to identify therapist characteristics that are associated with stronger alliance would be highly relevant. However, our results suggest that the unique relationship between a therapist and his or her specific patient, and not general skills or characteristics, determined the level of the alliance. The challenge for therapists is thus to practice how to attend to and manage problems in particularly challenging therapeutic relationships. Research on therapist-patient matching is an important subject for further investigation.

In this study, reciprocity meant that patient and therapist rated WAI scales at the same time. They evaluated their common work from their respective perspectives. Although we have argued that there is a dependence between the ratings in the sense that they enter their ratings after an hour of mutual collaborative effort, it is interesting to note that the correlation between their ratings was in the medium range. Not more than 14% of the ratings of one partner could be predicted by the ratings of the other. In future studies of the meaning of reciprocity, it might be interesting to use other rating perspectives such as asking one partner how he or she thinks that the other partner rates the alliance (Hartmann et al., Citation2015).

Our findings do not preclude that some therapists may be more skillful, on average, at creating strong alliances, or that there are patients with whom most therapists would find it hard to create a fruitful alliance. But even so, it is important that therapists continuously monitor the alliance development in their therapies. This may be an important way to develop “deliberate practice” (Rousmaniere, Goodyear, Miller, & Wampold, Citation2017). It should be noted that the finding that unusually high and reciprocal alliance ratings from therapist and patient were associated with positive outcome also entails that particularly low ratings were associated with worse outcome. Considering both these observations, there is the possibility that extreme ratings could be seen as alliance ruptures or alliance peaks.

At this point, it is not possible to know why some studies indicate that differences between therapists account for a larger share of outcome variance whereas others, including this one, rather emphasize the importance of variation within therapists. Differences in sample size and distribution of the number of patients treated by each therapist, patient characteristics, treatment orientation, hidden layers in data (for example treatment units) and differences in procedure and data analysis may account for the seeming inconsistency in findings. Kivlighan et al. (Citation2015) hypothesize that one likely reason why patient relationship ratings are related to patient outcome ratings is the common rater confound (Heppner, Wampold, & Kivlighan, Citation2008). In our study, both therapists’ and patients’ ratings were associated with outcome when analyzed within therapists. Thus, the association between outcome and alliance within therapists cannot be attributed to the common rater confound when therapists provide the alliance ratings.

A limitation in this study is inherent in its one-with-many design. Since patients only provide alliance ratings for a single therapist, it is not possible to disentangle how much of the total variance can be attributed to patients provoking specific alliance experiences from their therapists. Also, it is not possible to investigate whether patients might have specific patterns of rating the alliance regardless of therapists. Unfortunately, when investigating working alliance in individual psychotherapy, it is hard to imagine a valid method for partitioning this variance since it would assume patients being treated by several therapists. However, as stated earlier, the model used in this study is still an improvement over handling dyadic variables as raw scores. The symptom change variables were treated as predictors in the models. This conceptualization of the alliance-outcome association might be seen as problematic since it differs from the standard way of predicting outcome from alliance. However, in order to compare our results to Marcus et al. (Citation2009) we chose not to alter the model.

Marcus et al. (Citation2009) analyzed cross-sectional ratings of alliance collected prior to session four. In our study, alliance ratings were collected directly after sessions three. Crits-Christoph, Gibbons, Hamilton, Ring-Kurtz, and Gallop (Citation2011) have shown that aggregating several alliance scores might be necessary for a reliable measurement of the alliance quality. In addition, analyses of consecutive alliance ratings over the course of treatment might create more adequate models of the significance of ratings within and between therapists.

There was limited therapist-level variability concerning treatment outcome in the study. This might have restricted the ability to find an association between the therapist partner and perceiver effects and outcome. Our study had fewer therapists (n = 50) but more patients (n = 456) than Marcus et al. (Citation2009), who had 65 therapists and 227 patients. Schiefele et al. (Citation2017) investigated sample size requirements for multilevel models for detecting therapist effects in the context of naturalistic study designs. According to Schiefele et al. (Citation2017), the therapist- patient ratio in Marcus et al. (Citation2009) might show a small overestimation of therapist effects in comparison with the present study. Another caveat was that only patients rated treatment outcome in this study.

To summarize, most studies support the importance of therapist effects in the alliance-outcome association, and some studies support the view that both within- and between-therapist effects are significant. This study deviates by showing mainly within-therapist effects. Thus, the evidence on this issue is inconclusive, and research on the alliance-outcome correlation would benefit from further testing. Importantly, future studies should continue to use mixed effects models to disentangle patient and therapist contributions to the association. Also, alliance measures collected over the course of the treatment should be included to investigate how different patterns of change are influenced by the dyadic relationships.

ORCID

Carl-johan Uckelstam http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2402-4547

Rolf Holmqvist http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2093-2510

Björn Philips http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4313-1011

Fredrik Falkenström http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2486-6859

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atzil-Slonim, D., Bar-Kalifa, E., Rafaeli, E., Lutz, W., Rubel, J., Schiefele, A.-K., & Peri, T. (2015). Therapeutic bond judgments: Congruence and incongruence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 773–784. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000015

- Bachelor, A. (2013). Clients’ and therapists’ views of the therapeutic alliance: Similarities, differences and relationship to therapy outcome. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20, 118–135. doi: 10.1002/cpp.792

- Baldwin, S. A., Imel, Z. E., Braithwaite, S. R., & Atkins, D. C. (2014). Analyzing multiple outcomes in clinical research using multivariate multilevel models. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(5), 920–930. doi: 10.1037/a0035628

- Baldwin, S. A., Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2007). Untangling the alliance–outcome correlation: Exploring the relative importance of therapist and patient variability in the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 842–852. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.842

- Crits-Christoph, P., Gibbons, M. B. C., Hamilton, J., Ring-Kurtz, S., & Gallop, R. (2011). The dependability of alliance assessments: The alliance–outcome correlation is larger than you might think. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 267–278. doi: 10.1037/a0023668

- Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., Horvath, A. O., Symonds, D., & Wampold, B. E. (2012). Therapist effects in the therapeutic alliance–outcome relationship: A restricted-maximum likelihood meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.07.002

- Elfström, M. L., Evans, C., Lundgren, J., Johansson, B., Hakeberg, M., & Carlsson, S. G. (2012). Validation of the Swedish version of the clinical outcomes in routine evaluation outcome measure (CORE-OM). Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20, 447–455.

- Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., McGrath, G., Mellor-Clark, J., & Audin, K. (2002). Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: Psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 51–60. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.1.51

- Falkenström, F., Ekeblad, A., & Holmqvist, R. (2016). Improvement of the working alliance in one treatment session predicts improvement of depressive symptoms by the next session. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(8), 738–751. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000119

- Falkenström, F., Granström, F., & Holmqvist, R. (2013). Therapeutic alliance predicts symptomatic improvement session by session. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 317–328. doi: 10.1037/a0032258

- Falkenström, F., Granström, F., & Holmqvist, R. (2014). Working alliance predicts psychotherapy outcome even while controlling for prior symptom improvement. Psychotherapy Research, 24, 146–159. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.847985

- Falkenström, F., Hatcher, R. L., & Holmqvist, R. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis of the patient version of the working alliance inventory - short form revised. Assessment, 22, 581–593. doi: 10.1177/1073191114552472

- Falkenström, F., Hatcher, R. L., Skjulsvik, T., Larsson, M. H., & Holmqvist, R. (2015). Development and validation of a 6-item working alliance questionnaire for repeated administrations during psychotherapy. Psychological Assessment, 27(1), 169–183. doi: 10.1037/pas0000038

- Falkenström, F., Josefsson, A., Berggren, T., & Holmqvist, R. (2016). How much therapy is enough? Comparing dose-effect and good-enough models in two different settings. Psychotherapy, 53(1), 130–139. doi: 10.1037/pst0000039

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., & Horvath, A. O. (2018, May 24). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy. Advance Online Publication, doi: 10.1037/pst0000172

- Gullo, S., Lo Coco, G., & Gelso, C. (2012). Early and later predictors of outcome in brief therapy: The role of real relationship. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68, 614–619. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21860

- Hartmann, A., Joos, A., Orlinsky, D. E., & Zeeck, A. (2015). Accuracy of therapist perceptions of patients’ alliance: Exploring the divergence. Psychotherapy Research, 25, 408–419. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2014.927601

- Hatcher, R. L., & Gillaspy, J. A. (2006). Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychotherapy Research, 16, 12–25. doi: 10.1080/10503300500352500

- Heppner, P. P., Wampold, B. E., & Kivlighan, D. M., Jr. (2008). Research design in counseling (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

- Holmqvist, R., Ström, T., & Foldemo, A. (2014). The effects of psychological treatment in primary care in Sweden—A practice-based study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 68(3), 204–212. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2013.797023

- Horvath, A. O., Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., & Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9–16. doi: 10.1037/a0022186

- Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(2), 223–233. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223

- Huppert, J. D., Kivity, Y., Barlow, D. H., Gorman, J. M., Shear, M. K., & Woods, S. W. (2014). Therapist effects and the outcome-alliance correlation in cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 52, 26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.11.001

- Kenny, D. A. (1994). Interpersonal perception: A social relations analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Kivlighan, D. M., Jr., Gelso, C. J., Ain, S., Hummel, A. M., & Markin, R. D. (2015). The therapist, the client, and the real relationship: An actor–partner interdependence analysis of treatment outcome. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 314–320. doi: 10.1037/cou0000012

- Kivlighan, D. M., Jr., Hill, C. E., Gelso, C. J., & Baumann, E. (2016). Working alliance, real relationship, session quality, and client improvement in psychodynamic psychotherapy: A longitudinal actor partner interdependence model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(2), 149–161. doi: 10.1037/cou0000134

- Lingiardi, V., Holmqvist, R., & Safran, J. D. (2016). Relational turn and psychotherapy research. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 52, 275–312. doi: 10.1080/00107530.2015.1137177

- Marcus, D. K., Kashy, D. A., & Baldwin, S. A. (2009). Studying psychotherapy using the one-with-many design: The therapeutic alliance as an exemplar. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(4), 537–548. doi: 10.1037/a0017291

- Marcus, D. K., Kashy, D. A., Wintersteen, M. B., & Diamond, G. S. (2011). The therapeutic alliance in adolescent substance abuse treatment: A one-with-many analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(3), 449–455. doi: 10.1037/a0023196

- Marmarosh, C. L., & Kivlighan, D. M., Jr. (2012). Relationships among client and counselor agreement about the working alliance, session evaluations, and change in client symptoms using response surface analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(3), 352–367. doi: 10.1037/a0028907

- Mechler, J., & Holmqvist, R. (2016). Deteriorated and unchanged patients in psychological treatment in Swedish primary care and psychiatry. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 70(1), 16–23. doi: 10.3109/08039488.2015.1028438

- Raudenbush, S. W., Brennan, R. T., & Barnett, R. C. (1995). A multivariate hierarchical model for studying psychological change within married couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 9(2), 161–174. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.9.2.161

- Rousmaniere, T., Goodyear, R. K., Miller, S. D., & Wampold, B. E. (2017). The cycle of excellence. Using deliberate practice to improve supervision and training. . Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance: A relational treatment guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Schiefele, A. K., Lutz, W., Barkham, M., Rubel, J., Böhnke, J., Delgadillo, J., … Lambert, M. J. (2017). Reliability of therapist effects in practice-based psychotherapy research: A guide for the planning of future studies. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(5), 598–613. doi: 10.1007/s10488-016-0736-3

- Tracey, T. J., & Kokotovic, A. M. (1989). Factor structure of the working alliance inventory. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1(3), 207–210. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.1.3.207

- Tryon, G. S., Blackwell, S. C., & Hammel, E. F. (2007). A meta-analytic examination of client-therapist perspectives of the working alliance. Psychotherapy Research, 17, 629–642. doi: 10.1080/10503300701320611

- Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Zilcha-Mano, S., Solomonov, N., Chui, H., McCarthy, K. S., Barrett, M. S., & Barber, J. P. (2015). Therapist-reported alliance: Is it really a predictor of outcome? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(4), 568–578. doi: 10.1037/cou0000106

- Zuroff, D. C., Kelly, A. C., Leybman, M. J., Blatt, S. J., & Wampold, B. E. (2010). Between-therapist and within-therapist differences in the quality of the therapeutic relationship: Effects on maladjustment and self-critical perfectionism. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(7), 681–697.

Appendix A

The variance components in reference to Equation (1) and the social relations model