Abstract

Objective: There is a need to understand more of the dyadic processes in therapy and how the therapist’s ways of being are experienced and reflected upon by both patient and therapist. The aim of this dyadic case study was to investigate how the therapist’s personal presence was perceived by the patient and the therapist as contributing to change.

Method: From a larger project on collaborative actions between patient and therapist, a dyadic case involving in-depth interviews of the therapist and patient was selected to examine the research question. Interpretative phenomenological analysis of four interviews with the therapist and one interview with the patient was conducted.

Results: The analyses indicated that the therapist’s way of being, as perceived by both therapist and patient, was expressed at a superordinate level through the concept of embodied listening, which was of particular help for the patient, and influenced by the therapist’s theoretical orientation, as well as being rooted in his own personal history. Three sub-themes emerged from the analysis, each illustrating how embodied listening contributed to the therapeutic relationship and process. Our findings flesh out how the underlying phenomena of emotional attunement, presence, and genuineness are observable in therapeutic encounters.

Clinical and methodological significance of this article:

By combining four qualitative interviews with a therapist and one with his patient, this in-depth case study provides a dual perspective on one psychotherapy process. The results contribute to the understanding of how the therapeutic work was influenced and rooted both in the therapist`s personal history and in his preferred theoretical model. This case study provides material about therapist presence and congruence/ attunement that could be useful in the education, training, and supervision of therapists, and thus be of interest and relevance to a larger audience of clinicians working with patients.

There is a need to understand more of the dyadic processes in therapy (Atzil-Slonim & Tschacher, Citation2020), that is, the mutual influence and emotional co-regulation between patient and therapist and how these contribute to therapeutic change. Toward this end, we need a breadth of methodological approaches, from advanced statistical methods to in-depth case studies, taking both the therapist’s and patient’s perspective into account. As a consequence of the “relational turn” in psychotherapy (Lingiardi et al., Citation2016; Norcross & Lambert, Citation2018), it is now commonly accepted to see all therapeutic interactions as interdependent, dynamic systems in which both patient and therapist are mutually shaped and transformed over time, even if they have different responsibilities and roles in the therapy work (Atzil-Slonim & Tschacher, Citation2020). This development owes a great deal to the discovery of significant therapist effects (Baldwin & Imel, Citation2013), and the burgeoning literature on what distinguishes more and less effective therapists (see Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017; Heinonen & Nissen-Lie, Citation2020). Research on both favorable therapist characteristics and therapist professional development indicates that effective therapists are typically characterized by a sophisticated set of skills and capabilities which essentially merge their professional and personal attributes to create a unique way of being or therapeutic presence. This is a quality that is not easily defined but may be observed in action (Bennett-Levy, Citation2019; Hayes & Vinca, Citation2017; Macdonald & Muran, Citation2020; Nissen-Lie et al., Citation2017). In this study, we will go into the matter of therapeutic presence and how this is perceived from a dyadic perspective through a challenging but ultimately fruitful therapy process.

Therapeutic presence is related to the therapist’s personal domain and can be seen as a prerequisite for empathy and successful outcome of therapy. It is defined as the therapist’s ability and way of “being aware of and centered in oneself while maintaining attunement to and engagement with another person” (Hayes & Vinca, Citation2017, pp. 86–87).

More and more empirical studies have examined how both personal and professional skills and attributes of the therapist have directly or indirectly influenced the therapy process or outcome (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2009; Heinonen & Nissen-Lie, Citation2020; Nissen-Lie et al., Citation2017). However, what many of these quantitative studies do not capture is how these aspects of the therapist’s functioning come into play and are experienced and reflected upon by the therapists themselves as well as their patient in a mutual interplay between intentional actors (Nissen-Lie et al., Citation2017).

Conceptually, in addition to therapist presence (Hayes & Vinca, Citation2017), appropriate responsiveness (Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017; Stiles et al., Citation1998); emotional attunement (Colosimo & Pos, Citation2015; Dunn et al., Citation2013; Geller & Greenberg, Citation2012); and the real relationship (Gelso et al., Citation2018; Greenson, Citation1971) all seek to frame how the inter- and intra-personal skills of the therapist come to work together with his or her professional expertise in the therapeutic relationship with the patient. For example, appropriate responsiveness is defined as therapists’ ability “to generally respond to benefit their patients, seeking to be aware of their behavior and to adjust it in response to patients’ needs” (Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017, p. 72). The construct of the real relationship (Gelso, Citation2011; Greenson, Citation1971) is defined as “the personal relationship existing between two or more persons as reflected in the degree to which each is genuine with the other and perceives the other in ways that befit the other” (Gelso, Citation2011, pp. 12–13). The “real” part, thus, relates to the authentic personal bond between two people rooted in reality and to the concepts of the therapist’s personal congruence and genuineness/authenticity (Gelso, Citation2011). Following Greenson’s conception of the therapeutic relationship as consisting of three parts, the alliance, the transference-counter-transference configuration, and the real relationship, Gelso argues that the real relationship constitutes a fundamental precondition for an alliance (Bordin, Citation1994) to be established, as well as for the transference/counter-transference processes to occur (Gelso, Citation2011; Greenson, Citation1971). The underlying tenet in much of this literature seems to be in line with Carl Rogers (Citation1957) formulation of genuineness and congruence; namely, that in order to help others gain insight into and become more their genuine selves, the therapist must also possess the same authenticity.

These theoretical ideas are supported by a number of qualitative studies of therapist characteristics that seem to promote a fruitful therapy process. For example, the body of literature on expert therapists has identified emotional receptivity and openness as key characteristics of experienced and effective therapists (Jennings et al., Citation2008; Orlinsky & Rønnestad, Citation2005; Skovholt & Jennings, Citation2004). In their in-depth study of eight therapists, Spinelli and Marshall (Citation2001) have found a close connection between the therapist’s personal worldview and his or her professional theories of change. This has led these authors to introduce the concept of embodied theories, describing how professional knowledge becomes integrated with their personal selves, indicating “a significant level of comfort, affirmation or discovering which resonates with one’s being at a deep level” (p. 166). Moltu and Binder (Citation2013) have investigated how skilled therapists experience their contribution to constructively resolving impasses during therapy. They have found that the therapist’s active listening stance toward his or her own bodily sensations is perceived as important in getting emotionally close enough to the patient’s change process. The authors see this capacity for embodied empathy as related to the therapists’ relational competencies (p. 8).

In short, both conceptual contributions and empirical evidence point to the idea that for therapists to work effectively in dyadic processes, they also need to be able to address their own experiences and feelings with the same degree of openness and flexibility that they try to facilitate in the patient (Hayes & Vinca, Citation2017; Jørgensen, Citation2019). Although there has been increased attention to the therapist’s contribution and that of the unique dyad in understanding how psychotherapy achieves change (Heinonen & Nissen-Lie, Citation2020), few studies have explored how therapists’ attributes such as responsiveness, attunement, presence, and the real relationship are observable in actual psychotherapeutic processes or are experienced by the therapists themselves and their patients. Often our knowledge about the interplay of the personal and the professional is relatively general and decontextualized, and many scholars have called for research to explore therapists’ own experiences of their personal qualities and life history as potentially relevant to, and present in, their actual clinical work (Gelso & Perez-Rojas, Citation2017; Hayes et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, how the patient perceives and makes use of the therapist’s way of being present, genuine, and real needs to be explored too. Therapists in training could benefit from a deeper understanding of how to transform personal experiences of theirs into something they might apply therapeutically (Rønnestad & Skovholt, Citation2013).

To pursue these aims, one previous qualitative study (Bernhardt et al., Citation2019), as well as the current case study, was conducted as part of a larger project on collaborative actions between patient and therapist (Råbu et al., Citation2013, see details about the design in the methods section). Based on two in-depth interviews with the participating therapists, the earlier study explored therapists’ experiences of the significance of their own personal qualities and development for their professional practice. All the therapists in that sample described experiencing a tension between their personal strengths and vulnerabilities and their professional role (Bernhardt et al., Citation2019). During the process of analyzing the data from this prior study, the idea emerged to explore one therapeutic process more fully. Traditionally, in most case studies within the field of psychology and medicine, it is the patient who is considered to be “the case.” However, when it comes to psychotherapy, case studies offer a valuable possibility of getting different subjective perspectives on the same therapy process. Such dual perspectives have been used in several previous case studies exploring psychotherapy (Halvorsen et al., Citation2016; Råbu & Haavind, Citation2012; Yalom & Elkin, Citation1974).

Thus, the aim of this current in-depth dyadic case study was to gain insight into how the therapist’s personal way of being (i.e., personal presence) was experienced as potentially useful by both therapist and patient, and how it might contribute beneficially in an actual therapeutic change process. Hence, the case in this study is the dyadic therapeutic process, as it was explored from the viewpoint of the participants’ subjective experiences and reflections on the development of their relationship. The exploration of the case was guided by the following research question: How does the therapist’s personal presence, as perceived by both therapist and patient, influence the therapeutic relationship, and (how) did it contribute to the process of achieving change in a specific therapy with a favorable outcome according to the both parties?

Method

As part of the research program to which this case study belongs (Råbu et al., Citation2013), we interviewed 16 therapists about how they draw upon and combine knowledge arising from life experience and professional expertise. All participants worked within the public mental health care system in Norway and were judged by their clinic managers as likely to establish constructive psychotherapy processes with patients. The therapists were encouraged to invite one of their patients to join the project based on their early conception of being able to help this particular person. All in all, 11 patients ended up participating in the project. We did not collect the formal diagnosis of the patients, but since all were admitted in the public mental health system, they had been formally diagnosed with a mental disorder with loss of function in need of treatment.

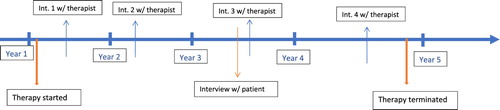

The design of the research program included four in-depth qualitative interviews of each therapist over a time span of 2–4 years, as well as 1 or 2 interviews with the patient (depending on treatment and what was feasible). The timing of the interviews was adjusted from case to case, depending on the therapist’s schedule, when they recruited the patient, and when the treatment was initiated. The first two interviews with the therapists focused on their personal development and their experience with and views on psychotherapy. The third interview with the therapist and the first interview with the patient focused on their specific therapy process. The fourth interview with the therapist served as an open-ended conversation without a specific interview guide where the researcher and participant had the opportunity to summarize and reflect on the central issues and themes that had emerged during the research process. In the current case study of one psychotherapy process, we included all four interviews with the therapist, as well as the single interview that was conducted with his patient (see for a timeline of the interview process).

Selection of the Case From the Sample

The selection of the current case was based on our conception that it would be able to provide both depth and fresh perspectives to central themes and patterns in the larger dataset (Bernhardt et al., Citation2019) and on our aim of understanding how the therapist’s personal way of being might contribute to the shaping of an actual therapeutic change process. In addition, this particular therapist’s use of his bodily, nonverbal presence in his therapeutic work, as described to us, distinguished him from the other therapists in the research project and in our view made this case particularly interesting to explore further. The recruited patient was also able to provide a rich description of the therapy process and her observations of the therapist. Finally, during the interviews the therapy process was referred to as beneficial by both parties.

Participants

The therapist

The therapist is a male in his late thirties working in a public outpatient clinic in a medium-size city in Norway. At the start of the research program he had 7 years of clinical experience and had completed a postgraduate program to become a specialist in clinical psychology. In addition, he was in the process of completing a 5-year training program in one form of psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapy (i.e., character analysis; cf. Sletvold, Citation2014). Character analysis is a theoretical and methodological orientation that has its roots in the work of Freud and Wilhelm Reich (Citation1972) but is also closely related to, and inspired by, relational psychoanalysis and infant research (cf. Aron, Citation1996; Bebee & Lachmann, Citation2014; Stern, Citation2004). It is characterized by its focus on nonverbal aspects of the therapeutic encounter as a source of meaning: movement, emotional interaction, and the therapist’s own bodily experience in the analytic encounter (Sletvold, Citation2016, p. 187). The personal history of the therapist includes several challenges due to a serious injury in his twenties and a congenital physical condition that has required him to undergo several major surgeries as an adult.

The patient

The patient is a woman in her fifties. As a young adult, she moved to Norway from another country. She has a history of high functioning both in her work life as a health care professional and in her private life. At the time of her referral to the unit where the therapist worked, a serious personal loss had triggered a psychological crisis with serious depression and anxiety, characterized by a distinct bodily collapse that made her unable to move and function in her daily life, which was interpreted to be part of a severe depression and anxiety disorder.

Context and background of the therapeutic process

The patient first encountered the therapist as the supervisor of a mobile emergency team that worked with her in her home as part of her initial treatment. As her condition improved during the next few months, she was referred to continue treatment as an outpatient at the clinic where the therapist worked. Then his manager decided that she should be offered psychotherapeutic treatment with him. The frequency of the meetings between patient and the therapist varied during these years according to the patient’s needs. They met on a weekly basis the first 2 years and then reduced the frequency to twice a month due to the patient’s work schedule as she gradually regained her mental health. Then followed a period with more frequent contact before a slow transition to more infrequent encounters toward the termination of therapy. In total, the therapeutic process lasted for approximately 5 years and was approaching its final phase when the data collection was completed.

Researchers

In addition to the three authors, two researchers affiliated with the larger project participated in analyzing the five interviews. All researchers are clinical psychologists with 15–40 years of experience with various clinical populations. The authors are trained in psychodynamic approaches and are also familiar with and inspired by other approaches to psychotherapy such as emotion-focused, humanistic, and cognitive therapy. All researchers work in a university setting, combining research with teaching and part-time psychotherapy practice.

Interviews

The interviews were semi-structured, following a set of exploratory open-ended questions in interview guides specific to either therapists and patients in the research program (see online Appendix for the full interview guides). As mentioned above, the fourth interview did not follow a specific interview guide, but served as an opportunity to summarize the interview-/research process, and check back on central themes and results with the participants.

For this case study, the first author conducted the interviews over a period of 4 years. Three interviews with the therapist were conducted in his own office, and one was conducted in the researcher’s office (out of practical reasons). The interviews were scheduled approximately once a year according to feasibility. Since the first two interviews focused solely on the therapist, and the third on the particular therapeutic process, the interview with the patient was scheduled to take place at approximately the same time as the third interview with the therapist (see with an overview of the therapeutic process and the interviews). Each interview lasted 60–90 min, and the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the first author. The interview with the patient was conducted in the therapist’s office, without the therapist being present.

Data Analysis

Methods of analyzing linguistic data must take account of the reflexivity and interpretative practice that characterize human language (Finlay, Citation2011; McLeod, Citation2013). With this in mind and in line with the primary goal of getting as close as possible to the lived experiences of both the therapist and the patient, in this current research project we applied Interpretative phenomenological analysis (Smith et al., Citation2009). The method is idiographic in that it studies the specific individual situation; phenomenological in its concern with individuals’ perceptions of objects or events; and hermeneutic in its recognition of the central role of the analyst in making sense of (observed) personal experience (Smith et al., Citation2009, p. 4.).

The process of analyzing the data for this case was led by the first author and proceeded in accordance with the main recommendations of Interpretative phenomenological analysis through the following steps. (1) All the authors read through the complete written material independently to obtain a basic sense of the therapeutic relationship from the perspectives of both the therapist and the patient. (2) The first author prepared the analysis by sorting text segments into broad content units that represented various aspects of each of the participants’ subjective experiences. The interviews of the therapist and the patient were analyzed separately and then were compared with regard to possible similarities and differences. (3) The preliminary themes and the condensed text segments for each participant were then presented, compared, and thoroughly discussed within the research group. The themes were presented with detailed reference to the transcribed material showing how the preliminary categories had emerged from the interviews and were consistent with what the participants had highlighted as significant. (4) The first author continued the analysis by further coding of the meaning segments. (5) Themes took form in the course of the rereading of transcripts, the writing of drafts, and reflective dialog among the researchers. Group discussions led to further revision of the themes and a sharpened focus on the therapeutic dyad in the final version of the themes. (6) Quotes to illustrate the eventual themes were suggested by the first author and discussed and refined with the other researchers.

Levitt et al. (Citation2017) propose the overarching concept of methodological integrity as a common foundation for trustworthiness across various approaches within qualitative research, replacing the traditional concepts of reliability, validity, and generalizability by fidelity and utility (Levitt et al., Citation2017, p. 8). Likewise, Finlay (Citation2011) replaces the concepts of external validity and generalizability by transferability, referring to the idea that readers should be given sufficient information to judge the applicability of the findings to other settings (pp. 262–263). To enhance openness and trustworthiness, we checked back with the participants regarding preliminary findings and themes from the analyses (i.e., member checking, Elliott et al., Citation1999). The themes were further validated through returning to the interview transcripts repeatedly to ensure a fit between the interpretation and the empirical data.

Reflexivity

In quantitative as well as in qualitative research, the researcher’s pre-existing intentions, assumptions, and theoretical affiliation give direction to the research design and the researcher’s interpretations (Finlay & Gough, Citation2003). To enhance our awareness of our own pre-understanding of the object of study (in this case, the role played in the therapeutic process by the therapist’s personal domain and way of being), after each interview with the therapist and the patient, the interviewer wrote down immediate thoughts, which were later shared with the larger research group. One pitfall we detected during this process was the interviewer’s tendency to idealize the therapist because of his apparent level of competence and reflectiveness. By participating in reflective writing tasks and discussions with the research group we sought to enhance transparency of the researcher’s interpretations and the analytic process, thus strengthening the methodological integrity of the study (Levitt et al., Citation2017; Råbu et al., Citation2019).

Ethics

The Norwegian Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics and the Norwegian Social Science Data Services approved the main study (Råbu et al., Citation2013). The audio files and the transcribed materials have been stored in a university database specifically developed for sensitive data. Both participants had each signed a consent form and were aware that they would participate together as a dyad in the study. Following a practice of process consent, which is widely used in situations of ethical sensitivity and potential participant vulnerability (Speer & Stokoe, Citation2014), both participants read a late draft of the paper to ensure that their experiences were conveyed in a suitable manner throughout the presentation of the case and to give their final consent. Both participants approved of the manuscript and expressed that they felt they recognized how the therapy process was presented.

Results

The theme of the embodied listener emerged as an overarching concept that incorporated the congruent quality between what both therapist and patient valued in the therapist’s specific way of using his personal and professional qualities. Both the superordinate theme and the three constituent sub-themes are described below.

The Embodied Listener: The Therapist’s Integration and Use of Personal and Professional Knowledge

In describing how he starts to work with a new patient, the therapist highlighted his use of a bodily presence to be able to capture what the patient needs from him:

We get the opportunity to repair something. So, how does this happen? I use the whole me, in a way. I ask myself: “What does this person need from me? In terms of emotional regulation, does he depend too much on himself or does he lean too much on others?” These issues manifest themselves through the body. It is so automatic, intuitive, and unconscious for many.

I feel that my physical challenges in many ways relate to my emotional issues. Not that my attachment history manifests itself directly in my legs, but still … it relates to my character and personality because I have lived with physical pain my whole life. I have endured the pain, dutifully moving forward, putting aside my own needs. In addition, I never talked about it. What would have happened if I did? I will never know. This is so rooted in my personality, and I also feel it is very much manifested in my body. Then, as an adult, I experienced a total collapse of the body. I understand this “collapse” as the result of how I dealt with everything on my own. I used to never listen to bodily signals, neither physical nor emotional.

Through the attention, intimacy, and authenticity my therapist showed me, I became more real in a way. I became important. I could easily have gone through years of therapy just talking, being analyzed, or being subject to behavioral therapy, but I think his way of being bodily present connected with me on another level – it allowed me to develop from just being someone that adjusts and accommodates to what other people need. This was the core issue in my personal therapy.

The patient’s descriptions of how she perceived the therapist and what he was doing to help her develop also emphasized the therapist’s holistic focus and how he listened to her with a distinct bodily presence:

He never gives advice, contrary to what I expected when I entered therapy. The therapy has worked very well because he has given me (the) space and time to talk about myself. He brings up and repeats small things, and I need that – that he says the same thing over again from different angles. Then, there is his focus on the bodily aspects; he can tell when I am anxious, and he can tell me about my breathing, he observes …

The following three constituent sub-themes encompass reflections by both the therapist and his patient with regard to their specific therapeutic process.

In the Beginning: The Significance of the Therapist’s Nonverbal Presence

The first time the therapist and this particular patient met each other, the patient’s health condition was characterized by severe anxiety and depression, with strong physical symptoms. He described the first meeting with her in the following way:

I remember that there was a great deal of concern about her because of the degree of despair and anxiety, and what could be described as a complete bodily “arrest.” She felt very detached and distant and seemed to have very little sense of her own body.

The therapist then described an experience of having to balance his communication with the patient carefully in order to avoid overwhelming her:

In the beginning, I had a strong sense that much of what I said did not resonate well with her, it was like having to balance myself on a tight rope. I would try to formulate or say something, and she would correct me. It became a sort of pattern. I perceived her as a quite guarded person who needed to stay in control … I think she was very anxious.

From the start, I listened very carefully to her nonverbal appeal to comprehend what was going on with her. It was my clear conception that she was very confused and frightened by her symptoms. A complete emotional shut-down, and a strong fear of approaching it.

The very first time I met him I was in a very bad state: I was seriously depressed. I thought: “Who is this person?” They had found me this person, but I had no idea of how I was going to use a therapist. When you have never been to therapy, you do not know what to expect, right? Nevertheless, it did not take long before I trusted him. He was very careful and attentive. No big plans like: “Now we’re going to fix you,” and that type of thing … He just listened. Back then, that was very important for me.

It was challenging, but there were always moments of contact where I felt I could reach her, and that gave me a strong faith in the therapeutic process from the very start. I never really knew how to proceed, but I just said to myself that I had to endure these feelings of insecurity in order for the process to move further. I tried to show her that we were in this together by inviting her to explore instead of defining and confronting.

Attuning to Each Other: Identification and Experienced Therapeutic Match

As the therapy proceeded, both participants highlighted the experience of a “match” between them as being an important feature of their therapeutic relationship. The following quote is from the patient:

I feel we have chemistry – we are a good match, which means I can be myself with him. I can use my irony and humor and – maybe he thinks I am a little crazy sometimes, he laughs, but he always brings me back to the “heart of the matter.”

If we have insight and knowledge about ourselves, I think we are more able to capture and uncover similar issues in the other. This can be both helpful but also a limitation … To be aware of one’s own experiences, and what one can relate to, even if it is not good, can open up so much in the relationship with the patient.

As I have gradually developed and become more familiar with myself as a therapist, I found myself operating in a very intuitive and “nonlinear” way that works with many of my patients. I use my different “hooks” to keep myself and the patient in an experiential mode, trying to get as close as possible to whatever the moment brings with it. The way I approach this is by waiting for the moment where I feel that I can come closer and maybe get behind the patient’s manifest behavior.

Another point of identification that both participants brought up as important in their relationship was a shared experience of being an “outsider” struggling to belong. They both referred to this as an objective fact in that they both were newcomers to the community, but also as a common existential theme with which they both could identify, concerning their difficulty in attaching to other people. The following quote illustrates the therapist’s use of such mutual experience by his deliberate use of self-disclosure.

It is a major theme for her, to feel different and that she does not belong. In the beginning, I chose to share with her that I myself moved here not that long ago. I think that the fact that I showed her that I could relate to how frustrating it could be to adapt to this local culture made her feel that I took her seriously and understood her feeling of isolation. This eventually made her open up about her loneliness and the sorrow she felt over what she had left behind in her country of origin.

I still have a long way to go. I have a picture of being able to come to terms with my life, and that I will be able to accept this place where I live now. That it can feel all right. To not always be longing for somewhere else. Yes, that this place where I live can feel like “my lot.”

Throughout my life, I have a pattern of establishing relationships, friendships, and then I move away or start something new, and I am not able to keep in touch, as if people slip away. Gradually I have gained insight into this pattern having to do with my own avoidance, and an expression of an underlying insecurity about myself – am I worth it?

Therapeutic Change: Creating a Safe Space for The Authentic Parts of Both the Therapist and the Patient

The therapist summarized the essence of his therapeutic theory of change and related this to what he thinks contributed to change in this specific therapeutic process:

I think that much of the changing effect of therapy happens in an implicit and nonverbal way. This happens through the therapist’s and patient’s way of being together, and the patient’s experience of feeling understood … With her, I feel this has had great value – that she could feel safe and understood.

He creates a very calm atmosphere. … and he often say to me, you know (name of the patient), this is your space where you can feel safe … In the beginning I used to write down stuff before the sessions. He said to me: you don’t have to plan our conversation, we can just be here together.

To create space for something new to happen, to be together, stay together in an emotional state, share this experience, and then to explore how this affects life and relationships outside of the therapy room.

In my personal life, I have adjusted to others to a very large degree and managed things on my own. Not to be so self-sufficient and dare trust others has been a major project for me … My training in character analysis challenged my personal strengths and vulnerabilities, because of its focus on both the empathic and authentic parts of the therapist: The empathic as being able to see and feel the other person, the authentic as being able to come forth with oneself in a more clear and confident way.

I have challenged her typical way of being, using mentalization-based exercises, often based on her bodily postures. We could explore how it feels to move this way or the other, how she regulates herself … She could handle that I “mirrored” her typical way of moving and leaning forward, leaving her little room for underlying emotions that have been shut off. When we practiced this, she was often able to establish contact with what goes on inside her.

Discussion

The aim of this dyadic case study was to contextualize and understand more of the ongoing interplay between patient and therapist, which unfolds in a fruitful but challenging therapy process. This was explored through both the therapist’s and the patient’s perspectives on the therapist’s way of being (or therapeutic presence; Hayes & Vinca, Citation2017) as an integrated whole of the therapist’s personal history and characteristics, professional insights, and skills. The findings indicated that the therapist’s way of being present was expressed at a superordinate level through the concept of embodied listening. This turned out to be of particular help for the patient in her acute emotional pain, which had a strong bodily component – and was influenced by the therapist’s theoretical orientation (i.e., a bodily focused psychodynamic approach, Sletvold, Citation2014), as well as being rooted in his own personal history of longstanding physical symptoms and emotional pain, which had been processed actively in personal therapy.

Both empirical evidence and theoretical rationales suggest that for therapists to be of help to a patient they need to be able to address their own experiences and feelings with the same degree of openness and flexibility that they try to facilitate in the patient (Hayes & Vinca, Citation2017; Jørgensen, Citation2019). Our findings, albeit resting on a single dyadic case study, support this notion and point to ways in which this is transferable to other therapeutic processes and clinical work in general. The therapist’s use of his own insights from personal therapy, his striving toward bodily presence and active use of emotional regulation strategies, as well as the use of therapeutically meaningful and well-timed self-disclosures are all important clues to understand how this dyadic case progressed toward a healthy end.

The themes found in the case study also point to how the therapist’s personal domain plays a part in clinical concepts known to be of significance for therapeutic outcomes. Apart from the therapist’s presence (Hayes & Vinca, Citation2017), these include nonverbal attunement and emotional co-regulation (Coyne et al., Citation2018), appropriate responsiveness and purposeful timing of empathy and technical interventions (Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017), as well as genuineness/authenticity (Gelso et al., Citation2018).

Both the therapist and patient in this case emphasized the therapist’s bodily focus and use of nonverbal interventions as being decisive for therapeutic change to occur, pointing to the significance of the therapist’s unspoken and nonverbal behavior in their therapeutic work. At first glance, one could ascribe this to the therapist’s particular theoretical orientation, i.e., character analysis – a bodily focused psychodynamic approach. While both the therapist’s personal therapy and psychoanalytic theoretical framework undoubtedly constituted an important inspirational source for his therapeutic stance, a substantial amount of the clinical literature has emphasized the affirmative and therapeutic power of nonverbal attunement and the preverbal messages that the therapist is able to convey (Colosimo & Pos, Citation2015; Dunn et al., Citation2013; Geller & Greenberg, Citation2012; Geller & Porges, Citation2014). Thus, the results from this study could transfer and have relevance beyond this specific case and psychoanalytic oriented therapies. The clinical significance of the ability to be rooted in oneself has been pointed out in earlier studies (cf. Jennings & Skovholt, Citation1999; Moltu & Binder, Citation2013; Spinelli & Marshall, Citation2001). Also, posture, eye contact, facial expression, use of minor sounds, and so on have been demonstrated to constitute a vital part of clinical communication, regardless of the therapist’s theoretical affiliation (cf. Baldini et al., Citation2014; Stern, Citation2004). Furthermore, how such nonverbal attunement and therapist presence can play a significant role in therapy is supported by evidence from neuroscience and interpersonal neurobiology showing that the human brain perceives and processes affective information in highly automatic and unconscious ways (Siegel, Citation2010). Witnessing nonverbal exchanges, posture, and eye gaze of another person during the relational process prompts similar cortical representations (mirroring) in the other person, potentially influencing his/her affective state (Hasson et al., Citation2012, p. 115). One could, for example, hypothesize that when safety is communicated by the therapist via such nonverbal cues, the patient’s defensiveness is down-regulated (Geller & Porges, Citation2014). Due to the spontaneous quality and moment-to-moment nature of such “mirroring,” it is likely that many of these microprocesses take place on an intuitive and implicit level, often outside of the therapist’s conscious control. Many therapists report that they experience their listening skills and ability to tune into the experience of others as something that come naturally to them (Bernhardt et al., Citation2019; Skovholt & Jennings, Citation2004). However, research on therapist presence has shown that patients rate the sessions as more effective when the therapist had done mindfulness exercises before therapeutic sessions (e.g., Dunn et al., Citation2013). This indicates that the therapist’s ability to be present can be enhanced by “deliberate practice” and various forms of exercises and is not a static quality that is developed once and for all (Bennett-Levy, Citation2019; Macdonald & Muran, Citation2020; Rousmaniere, Citation2016).

Related to this is the proposition that nonverbal attunement is a prerequisite for the therapist to show appropriate responsiveness in each clinical situation (Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017). The therapist’s ability to respond to the other person’s needs emanates partly from the inner work of the therapist (Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017). The therapist in this case illustrated such reflective activity in his inner dialog about the patient (“what does this person need from me?” and “In terms of emotional regulation, does he depend too much on himself or does he lean too much on others?”) and through his limited and strategic use of self-disclosure. This points to the way this particular therapist used both his authentic, personal and professional parts to revise and adjust his knowledge base for each new encounter or moment with the specific patient. Such flexibility is seen as a vital part of the therapist’s “personalized approach” (Rihacek & Roubal, Citation2017). It also points to the idea that regardless of theoretical orientation and how much theoretical knowledge and practical experience a therapist has, s/he still needs to improvise and adjust to the specific patient in the specific context in order to be of use to him or her (Oddli & McLeod, Citation2017; Owen & Hilsenroth, Citation2014). Also, through the therapist’s and his patient’s respective reflections on how some of their personal aspects complemented those of the other, it becomes clear how they both perceived the other as a “real person,” not just a “therapist” or a “patient.” As such, the case offers insight into what genuineness and “realness” are about, and how these can play out in the context of a specific therapeutic process. One could argue that the therapist’s ability to stay genuinely present facilitated the therapeutic process both by enabling the establishment of a real relationship and by setting the stage for both transference and counter-transference to occur (Gelso et al., Citation2018).

Finally, the congruent quality in the dual perspectives of the therapist and the patient in this case was striking and draws attention to the concept of congruence and therapist-patient attunement, which has been studied as a predictor of more favorable outcomes and consequently as a potential marker of therapist responsiveness (e.g., Coyne et al., Citation2018). As an example, a study by Kivlighan and Arthur (Citation2000) showed that the agreement between patient and therapist in the recalling of important therapeutic events increased over time and in turn was related to better outcomes, as measured by a decrease in interpersonal problems. The authors raised the question of how such convergence in perceived important events develops. Other studies also indicate that increased synchrony and increasingly similar ratings of the bond aspect of the therapeutic alliance are linked to therapy outcomes (Atzil-Slonim et al., Citation2015).

However, access into how the therapist’s personalized embodied theory is used in clinical work (Spinelli & Marshall, Citation2001) may also draw attention to the possibility that more congruence between patient and therapist may be a sign of unresolved counter-transference issues and over-identification with the patient material. For example, it is possible that the therapist’s experienced congruence in the current case could arise from seeing the patient in correspondence with his own past or present needs, rather than his tuning into the state and emotional needs of the patient (cf. Gelso & Hayes, Citation2007). Hence, experienced congruence could serve to keep therapist’s experienced dissonance at bay, ensuring a feeling of being “the good helper” (and as such feeding the therapist’s own more narcissistic need – cf. Miller, Citation1981). If so, the congruence is interpreted as a product not of the therapist’s genuine self (cf. Rogers, Citation1957) but rather of his/her more defensive needs, and could ultimately result in inadequate responsiveness and interventions, as well as stagnation or poorer therapeutic outcomes (Castonguay et al., Citation2010; Rønnestad & Skovholt, Citation2013; Stiles et al., Citation1998; Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017).

In line with this, Gabbard (Citation1995, Citation2001) has discussed how a therapist’s hooks seem to represent aspects of his or her internal world that can become activated (and actualized) by the behavior of the patient. By being a source for counter-transference, such hooks constitute both a resource for therapists to draw upon in their work as well as a risk for enactment and over-identification with the patient (cf. Gabbard, Citation2001, p. 987; Nissen-Lie & Stänicke, Citation2014). However, the therapist in this case study refers to his personal hooks as something he actively uses to guide him in keeping himself and the patient in an “experiential mode,” a core characteristic of, and prerequisite for, change in his preferred psychotherapeutic model (i.e., character analysis, Sletvold, Citation2014). Thus, it seems for him that these hooks are not merely about his preconscious internal world “disrupting his familiar self” (and thereby letting the patient material become available to the therapist’s consciousness; Gabbard, Citation2001, p. 986). Rather, they seem to involve a more active and deliberate use of his personal inner experience that seem useful to the patient and to promote therapeutic change. The results from the current case study might shed light on how these underlying dyadic processes might occur. It is suggested that the attunement between the patient and the therapist was facilitated by the therapist’s use of his personal knowledge and his reflective, responsive stance and bodily presence, which combined with an effective use of self-disclosure brought about a special “moment of meeting” (Halvorsen et al., Citation2016; Stern, Citation2004) between the two. It seems that the therapist’s ability to be personally authentic and to integrate his personal and professional identities (Nissen-Lie et al., Citation2017; Rønnestad & Skovholt, Citation2013) could underlie patient–therapist attunement or convergence, as well as the ability to maintain a therapeutic stance (Jørgensen, Citation2019).

Implications and Future Research

The results from this study point to the importance for therapists of generally focusing more on their ability to access their own ongoing thoughts, feelings, and memories (i.e., their hooks) in their therapeutic work. Therapists’ awareness of their own personal “seesaw” of strengths and vulnerabilities can facilitate their identification with patients, keep them grounded in the therapist role, and help them differentiate constructive use of their own inner experience from nontherapeutic, harmful processes of stagnation and enactment. Also, students could systematically be encouraged to consider their motivation for entering a helping profession, as well as urged to think about what kind of personal “core” issues and hooks they would regard as potential strengths and/or limitations in their training.

Related to this is the question of the degree to which such personal capacities, especially the nonverbal and embodied qualities, first and foremost are an expression of “natural talent” or something that is possible to learn and cultivate through professional training. However methodologically challenging it would be to map such personal qualities of those entering education or training to become psychotherapists, this would be a promising area to explore further in future research (Bennett-Levy, Citation2019; Heinonen & Nissen-Lie, Citation2020), with potential implications for the selection and admission of individuals to psychotherapy training programs.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of the current case study lies in the access we obtained into how both a therapist and a patient reflect upon their mutual therapeutic process and the therapist’s personal way of being in the here and now (McLeod, Citation2013). The practical knowledge studied and produced by case studies is a kind of “intimate knowledge” (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006, p. 222) that is not offered in the same way by the theoretical, rational, and rule-based knowledge that is the basis of conventional learning. Also, we have worked toward an a-theoretical dissemination of results, which hopefully can enhance the relevance and utility for clinicians across varying theoretical schools. Despite this, our results are unavoidably influenced by the therapist’s psychoanalytic theoretical orientation and the fact that the therapy in question was a long-term psychodynamic treatment. For example, the linguistic and therapeutic focus on the significance of being seen, held, and contained can be seen as typical for many psychodynamically oriented therapies (cf. Kohut, Citation1984; Winnicott, Citation1971); Gullestad & Killingmo, Citation2020). Furthermore, due to the design of the overarching project, which had a primary research aim of studying the therapist’s contribution to fruitful therapy process (Råbu et al., Citation2013), we had four interviews with the therapist and only one with the patient. Hence, our results could be skewed toward the therapist’s perspective, de-emphasizing the patient’s experience, which one could argue is the most valuable source for the appraisal of the therapist’s therapeutic presence. Also, we lacked standardized outcome measures. Nonetheless, the therapeutic outcome was judged as favorable based on the self-report of both the patient and therapist during the interviews.

References

- Anderson, T., Ogles, B. M., Patterson, C. L., Lambert, M. J., & Vermeersch, D. A. (2009). Therapist effects: Facilitative interpersonal skills as a predictor of therapist success. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(7), 755–768. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20583

- Aron, L. (1996). A meeting of minds. The Analytic Press.

- Atzil-Slonim, D., Bar-Kalifa, E., Rafaeli, E., Lutz, W., Rubel, J., Schiefele, A.-K., & Peri, T. (2015). Therapeutic bond judgments: Congruence and incongruence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(4), 773–784. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000015

- Atzil-Slonim, D., & Tschacher, W. (2020). Dynamic dyadic processes in psychotherapy: Introduction to a special section. Psychotherapy Research, 30(5), 555–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1662509

- Baldini, L. L., Parker, S. C., Nelson, B. W., & Siegel, D. J. (2014). The clinician as neuroarchitect: The importance of mindfulness and presence in clinical practice. Clinical Social Work Journal, 42(3), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-014-0476-3

- Baldwin, S. A., & Imel, Z. E. (2013). Therapist effects: Finding and methods. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed., pp. 258–297). Wiley.

- Bebee, B., & Lachmann, F. M. (2014). The origins of attachment. Routledge.

- Bennett-Levy, J. (2019). Why therapists should walk the talk: The theoretical and empirical case for personal practice in therapist training and professional development. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 62, 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.08.004

- Bernhardt, I. S., Nissen-Lie, H. A., Moltu, C., McLeod, J., & Råbu, M. (2019). “It’s both a strength and a drawback.” How therapists’ personal qualities are experienced in their professional work. Psychotherapy Research, 29(7), 959–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2018.1490972

- Bordin, E. S. (1994). Theory and research on the therapeutic working alliance: New directions. In A. O. Horvath, & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Wiley series on personality processes. The working alliance: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 13–37). John Wiley & Sons.

- Castonguay, L. G., Boswell, J. F., Constantino, M. J., Goldfried, M. R., & Hill, C. E. (2010). Training implications of harmful effects of psychological treatments. American Psychologist, 65(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017330

- Colosimo, K. A., & Pos, A. E. (2015). A rational model of expressed therapeutic presence. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 25(2), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038879

- Coyne, A. E., Constantino, M. J., Laws, H. B., Westra, H. A., & Antony, M. M. (2018). Patient–therapist convergence in alliance ratings as a predictor of outcome in psychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 28(6), 969–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1303209

- Dunn, R., Callahan, J. L., Swift, J. K., & Ivanovic, M. (2013). Effects of pre-session centering for therapists on session presence and effectiveness. Psychotherapy Research, 23(1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.731713

- Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466599162782

- Finlay, L. (2011). Phenomenology for therapists: Researching the lived world. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Finlay, L., & Gough, B. eds. (2003). Reflexivity: A practical guide for researchers in health and social sciences. Blackwell Science.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Gabbard, G. O. (1995). Countertransference: The emerging common ground. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 76, 475–485.

- Gabbard, G. O. (2001). A contemporary psychoanalytic model of countertransference. Journal of Clinical Psychology: in Session, 57(8), 983–991. https://doi.org/10.10002/jclp.1065

- Geller, S., & Greenberg, L. S. (2012). Therapeutic presence: A mindful approach to effective therapy. American Psychological Association.

- Geller, S. M., & Porges, S. W. (2014). Therapeutic presence: Neurophysiological mechanisms mediating feeling safe in therapeutic relationships. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 24(3), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037511

- Gelso, C. J. (2011). The real relationship in psychotherapy: The hidden foundation of change. American Psychological Association.

- Gelso, C. J., & Hayes, J. A. (2007). Countertransference and the inner world of the psychotherapist: Perils and possibilities. Erlbaum.

- Gelso, C. J., Kivlighan, D. M., & Markin, R. D. (2018). The real relationship and its role in psychotherapy outcome: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000183

- Gelso, C. J., & Perez-Rojas, A. E. (2017). Inner experience and the good therapist. In L. Castonguay, & C. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others? Understanding therapist effects (pp. 101–115). American Psychological Association.

- Greenson, R. R. (1971). The “real” relationship between the patient and the psychoanalyst. In M. Kanzer (Ed.), The unconscious today: Essays on Max Schur (pp. 213–232). International Universities Press.

- Gullestad, S., & Killingmo, B. (2020). The theory and practice of psychoanalytic therapy: Listening for the subtext. Routledge.

- Halvorsen, M. S., Benum, K., Haavind, H., & McLeod, J. (2016). A life-saving therapy: The theory-building case of “cora.”. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 12(3), 158–193. https://doi.org/10.14713/pcsp.v12i3.1975

- Hasson, U., Ghazanfar, A. A., Galantucci, B., Garrod, S., & Keysers, C. (2012). Brain-to-brain coupling: A mechanism for creating and sharing a social world. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(2), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2011.12.007

- Hayes, J., Gelso, C. J., & Hummel, A. M. (2011). Managing countertransference. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022182

- Hayes, J. A., & Vinca, M. (2017). Therapist presence, absence and extraordinary presence. In L. Castonguay, & C. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others? Understanding therapist effects (pp. 85–99). American Psychological Association.

- Heinonen, E., & Nissen-Lie, H. A. (2020). The professional and personal characteristics of effective psychotherapists: A systematic review. Psychotherapy Research, 30(4), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1620366

- Jennings, L., D’Rozario, V., Goh, M., Sovereign, A., Brogger, M., & Skovholt, T. M. (2008). Psychotherapy expertise in Singapore: A qualitative investigation. Psychotherapy Research, 18(5), 508–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802189782

- Jennings, L., & Skovholt, T. M. (1999). The cognitive, emotional, and relational characteristics of master therapists. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 46(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.46.1.3

- Jørgensen, C. R. (2019). The psychotherapeutic stance. Springer International Publishing.

- Kivlighan, D. M. J., & Arthur, E. G. (2000). Convergence in patient and counselor recall of important session events. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0167.47.1.79

- Kohut, H. (1984). The role of empathy in psychoanalytic cure. In A. Goldberg & P. E. Stepansky (Eds.), How does analysis cure?. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Levitt, H. M., Motulsky, S. L., Wertz, F. J., Morrow, S. L., & Ponterotto, J. G. (2017). Recommendations for designing and reviewing qualitative research in psychology: Promoting methodological integrity. Qualitative Psychology, 4(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000082

- Lingiardi, V., Holmqvist, R., & Safran, J. D. (2016). Relational turn and psychotherapy research. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 52(2), 275–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00107530.2015.1137177

- Macdonald, J., & Muran, C. J. (2020). The reactive therapist: The problem of interpersonal reactivity in psychological therapy and the potential for a mindfulness-based program focused on “mindfulness-in-relationship” skills for therapists. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000200

- McLeod, J. (2013). Increasing the rigor of case study evidence in therapy research. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 9(4), 382–402. https://doi.org/10.14713/pcsp.v9i4.1832

- Miller, A. (1981). Prisoners of childhood: the drama of the gifted child and the search for the true self.

- Moltu, C., & Binder, P. E. (2013). Skilled therapists’ experiences of how they contributed to constructive change in difficult therapies: A qualitative study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research: Linking Research with Practice, 14(2), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2013.817596

- Nissen-Lie, H. A., Rønnestad, M. H., Høglend, P. A., Havik, O. E., Solbakken, O. A., Stiles, T. C., & Monsen, J. T. (2017). Love yourself as a person, doubt yourself as a therapist? Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 24(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1977

- Nissen-Lie, H., & Stänicke, E. (2014). “Yes, of course it hurts when buds are breaking”: therapist reactions to an adolescent patient’s sexual material in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology: in Session, 70(2), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22067

- Norcross, J. C., & Lambert, M. J. (2018). Psychotherapy relationships that work III. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000193

- Oddli, H. W., & McLeod, J. (2017). Knowing-in-relation: How experienced therapists integrate different sources of knowledge in actual clinical practice. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 27(1), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000045

- Orlinsky, D. E., & Rønnestad, M. H. (2005). How psychotherapists develop: A study of therapeutic work and professional growth. American Psychological Association.

- Owen, J., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (2014). Treatment adherence: The importance of therapist flexibility in relation to therapy outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(2), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035753

- Råbu, M., & Haavind, H. (2012). Coming to an end: A case study of an ambiguous process of ending. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 12(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2011.608131

- Råbu, M., McLeod, J., Haavind, H., Bernhardt, I. S., Nissen-Lie, H. A., & Moltu, C. (2019). How psychotherapists make use of their experiences from being a patient: Lessons from a collective autoethnography. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1–20. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1671319

- Råbu, M., Moltu, C., & McLeod, J. (2013). The art and science of conducting psychotherapy: How collaborative action between client and therapist generates and sustains productive life change. University of Oslo. Department of Psychology.

- Reich, W. (1972). Character analysis (3rd ed.). Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

- Rihacek, T., & Roubal, J. (2017). Personal therapeutic approach: Concept and implications. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 27(4), 548–560. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000082

- Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045357

- Rønnestad, M. H., & Skovholt, T. M. (2013). The developing practitioner: Growth and stagnation of therapists and counselors. Routledge.

- Rousmaniere, T. (2016). Deliberate practice for psychotherapists: A guide to improving clinical effectiveness. Routledge.

- Siegel, D. J. (2010). The mindful therapist: A clinician’s guide to mindsight and neural integration. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Skovholt, T. M., & Jennings, L. (2004). Master therapists: Exploring expertise in therapy and counseling. Allyn & Bacon.

- Sletvold, J. (2014). The embodied analyst: From Freud and Reich to relationality. Routledge.

- Sletvold, J. (2016). The analyst’s body: A relational perspective from the body. Psychoanalytic Perspectives, 13(2), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/1551806X.2016.1156433

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. Theory, method and research. Sage Publications, Ltd.

- Speer, S. A., & Stokoe, E. (2014). Ethics in action: Consent-gaining interactions and implications for research practice. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12009

- Spinelli, E., & Marshall, S. (2001). Embodied theories. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Stern, D. (2004). The present moment in psychotherapy and everyday life. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Stiles, W. B., Honos-Webb, L., & Surko, M. (1998). Responsiveness in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(4), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00166.x

- Stiles, W. B., & Horvath, A. O. (2017). Appropriate responsiveness as a contribution to therapist effects. In L. Castonguay, & C. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others? Understanding therapist effects (pp. 71–84). American Psychological Association.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. New York: Routledge.

- Yalom, I., & Elkin, G. (1974). Every day gets a little closer: A twice told therapy. Basic Books.