ABSTRACT

Objective: Few studies have examined factors associated with patient’s choice of particular psychological treatments. The present study explores possible associations to, and the reasons given for, patient’s choice of Panic Control Treatment (PCT) or Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (PFPP) for Panic Disorder with or without Agoraphobia (PD/A).

Method: Both quantitative and qualitative analyses were applied to data obtained from 109 adults with PD/A who were randomized to the Choice condition in the doubly randomized controlled preference trial from which this data are drawn.

Results: The strongest associations were between treatment credibility ratings and the treatment choice (d = −1.00 and 1.31, p < .01, for PCT and PFPP respectively). Treatment choice was also moderately associated with patient characteristics, treatment helpfulness beliefs, and learning style. Qualitative analysis revealed that patients gave contrasting reasons for their treatment choice; either a focus on the present, symptom reduction and problem-solving for those who chose PCT or a focus on the past, symptom understanding and reflection for those who chose PFPP.

Conclusions: When offered a choice between two evidence-based psychotherapies for PD/A, the resulting choice was primarily a function of the patient’s beliefs about the chosen therapy, its potential for success, and their preferred learning style.

Clinical or Methodological Significance of this Article: Offering patients a choice between two or more evidence-based treatments (when available) is an important part of evidence-based medicine, and is associated with a range of improved health outcomes. However, little is known about the variables that are associated with the patient’s stated preference. The present study benefits from the data being drawn from the first doubly randomized controlled preference trial (DRCPT) offering patients a choice between two evidence-based psychotherapies for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (PD/A). The results demonstrate that patients with PD/A, if offered a choice, willingly express a treatment preference, and this reflects the subjective credibility of the chosen treatment, their beliefs about helpfulness factors and their preferred learning styles, rather than their sociodemographic or clinical characteristics, or previous experiences of treatment. The results suggest that therapists ask patients with PD/A about their expectations of therapy, and particularly how they think change might be best achieved for them given their learning style. This would be followed by the presentation of brief, simple-language (written) explanations about the how the various approaches on offer work, and then a discussion that helps to match the patient’s expectations to the relevant treatment approach.Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01606592.

Introduction

Brewin and Bradley (Citation1989) were among the first to acknowledge that in a randomized controlled trial of two or more distinct treatments, patients who are randomly allocated to their “preferred” treatment may experience better outcomes. Since then several studies have linked treatment preferences to various aspects of health outcomes. The majority have focused on various treatments for depression, not for anxiety disorders, usually comparing medication and psychotherapy, or two different formats (individual versus group) of the same psychotherapy. Several meta-analyses have found evidence of small but significant effects of preference on outcomes for a wide range of treatments for health and mental health conditions (Cohen’s d = 0.15–0.31) (Lindhiem et al., Citation2014; Swift et al., Citation2011; Swift et al., Citation2018). A meta-analysis by Windle et al. (Citation2019) that only included studies on mental health treatments found that receiving one’s preferred treatment was associated with lower drop-out rates and stronger therapeutic alliance, but not with better outcomes at the symptom/diagnosis level.

Given the modest but positive effects on mental health outcomes of accommodating the patient’s treatment preference, researchers have called for studies that identify the factors that are associated with preferences (McHugh et al., Citation2013; Steidtmann et al., Citation2012). To date, only a relatively small number of such studies have been carried out, with a high degree of heterogeneity in terms of sample characteristics and methods for eliciting patient treatment preferences (Swift et al., Citation2018). Overall, these studies find inconsistent and limited evidence for an association between treatment preferences and gender, age, education level, baseline clinical severity (mainly depression), previous treatment experience (mainly medication versus psychotherapy), social functioning and relational problems, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Dwight-Johnson et al., Citation2000; Houle et al., Citation2013; Markowitz et al., Citation2016; Sandell et al., Citation2011). To date, one study (Perreault et al., Citation2014) has examined factors associated with patient preferences for treatment of panic disorder (PD). The authors assessed patient preferences for individual versus group therapy prior to their enrolment in group-based cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for PD. No associations were observed between patient demographics, medication usage, treatment experience, or panic and agoraphobic symptom severity and their preference for group or individual CBT.

Some studies have examined the association between patient beliefs about the cause of their illness and treatment preferences. Houle et al. (Citation2013) found that adults seeking treatment for first-onset depression in primary care, who attributed their depression to social rather than psychological or physical causes, preferred psychotherapy (any) to medication. In a randomized controlled trial of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for chronic depression, Steidtmann et al. (Citation2012) found that participants who attributed their depression to a chemical imbalance preferred pharmacotherapy to CBT or supportive therapy, while participants who attributed their depression to stressful experiences preferred psychotherapy plus medication. In a mixed sample of psychotherapy patients, Tompkins et al. (Citation2017) found only limited support for associations between patient beliefs about the cause of their depression and their preferences for behavioural activation, cognitive therapy, interpersonal therapy, pharmacotherapy and psychodynamic therapy. Significant associations were found between biological beliefs for depression and preferences for pharmacotherapy and behavioural activation in a positive direction, and preferences for cognitive therapy in a negative direction.

A few studies have examined the role of patient’s beliefs about the therapy itself and their treatment preference. In a trial comparing CBT, behaviour therapy, cognitive therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy for weight loss, five primary reasons were identified that differentiated patient treatment preferences. Comprehensiveness was most commonly mentioned as the primary reason for preferring CBT, practicality for behaviour therapy, personal relevance for acceptance commitment therapy, and personal relevance and perceived effectiveness for cognitive therapy (Moffitt et al., Citation2015). Sandell et al. (Citation2011) administered the patient-report version of the Psychotherapy Experience Questionnaire (PEX) to a sample of psychiatric patients and non-clinical participants. The PEX is comprised of five subscales measuring helpfulness beliefs: externalization, internalization, catharsis, support, and defensiveness (Sandell et al., Citation2011). Participants who preferred psychodynamic therapy had higher scores on the internalization and lower scores on the externalization subscales of the PEX while participants preferring CBT had the opposite pattern.

Given the significant (though small) effects of treatment preferences on health outcomes, factors that are associated with such preferences are an important area for study. Studies attempting to identify such associations for mental health treatments are still relatively rare, with the majority having focused on how patient’s demographic and clinical characteristics relate to treatment preference, primarily medication versus psychotherapy for depression. Panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (PD/A) is a commonly occurring and highly debilitating condition (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000). The two most studied and recommended treatments are pharmacotherapy and various forms of CBT, but approximately 40-50% fail to achieve a clinically significant response during treatment or relapse when these treatments are withdrawn (Barlow et al., Citation2000; Hofmann & Spiegel, Citation1999; Imai et al., Citation2016; Pompoli et al., Citation2016). There is evidence that other forms of psychotherapy, including psychodynamic therapy, yield comparable outcomes to CBT in individuals with PD/A (Milrod et al., Citation2016; Pompoli et al., Citation2016). Whether offering patients with PD/A a choice between CBT and another form of psychotherapy is associated with improved outcomes remains unclear.

The present study uses data from the first doubly randomized controlled preference trial (DRCPT) (Sandell et al., Citation2015) examining whether outcomes for PD/A are superior when patients choose their treatment compared to when the treatment is randomly allocated. The two forms of psychotherapy offered to the participants were a form of CBT called Panic Control Treatment (PCT; Craske & Barlow, Citation2006) and Panic Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (PFPP; Milrod et al., Citation1997). The primary aim of the present study is to explore variables that were associated with the choice of either PCT or PFPP in patients who were randomized to the treatment choice condition in this trial. Specifically, we investigate whether the treatment choice is associated with sociodemographic (gender, age, education, employment) and clinical characteristics (symptom severity, comorbidity, prior treatment, and relational problems). Building on and extending the existing literature, we also examine whether the treatment choice is related to the participant’s beliefs about the relative helpfulness of various psychotherapy treatment components as measured by the PEX and their answers (in the context of their choosing) to a question about what appealed to them in the chosen treatment and why they chose that treatment. Finally, we administered the Learning Style Inventory (LSI; Kolb, Citation1984) which measures a person’s preference for different approaches to learning along four dimensions (Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation). The LSI was found to differentiate psychology students’ preferences for training in either CBT or PDT (Heffler & Sandell, Citation2009). This is the first study to use the LSI as part of an examination of patient preferences for either PCT or PFPP.

Method

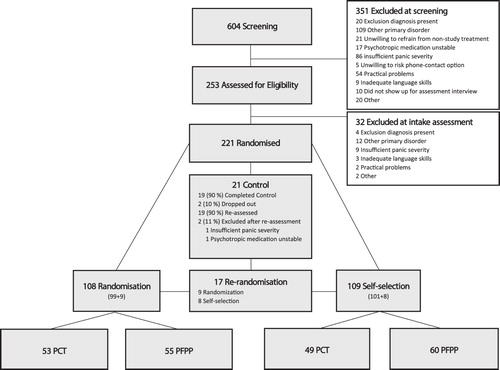

The project Psychotherapy Outcome and Self-selection Effects (POSE) was a multicentre, DRCPT of PCT and PFPP for PD/A. Participants were randomized to three conditions: one in which they were randomized to either PCT or PFPP (Random); or one in which they were informed that they would not be further randomized into treatment but given a choice of these same two treatments for PD/A (Choice); and a supported wait-list control condition (WL). Participants in the WL condition were re-randomized to either the Random or Choice conditions after twelve weeks. Details of the trial protocol are available in Sandell et al. (Citation2015).

Participants

Participants were between the ages of 18 and 70 years and had a current principal diagnosis of PD/A according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000), assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I; First et al., Citation1996). A total of 221 participants were randomized to the three conditions; 109 to the Choice condition (see ). Only data collected from participants in the Choice condition are analysed in this study. presents the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics separately for the participants who chose either PCT or PFPP at pre-treatment.

Interventions

A full description of the treatments are available in the trial protocol (Sandell et al., Citation2015). Briefly, PCT and PFPP are individual, manualized treatments for adults with PD/A (Craske & Barlow, Citation2006). PCT helps patients to anticipate and respond to situations that trigger panic attacks and to manage their physical symptoms of panic. PFPP helps patients to understand how their panic attacks are related to difficulties expressing emotions in an interpersonal context, including the therapeutic relationship.

Measures

Clinical measures

PD/A severity was assessed with the clinician-rated Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS; Shear et al., Citation1997). The PDSS is comprised of 7 items, each scored on a 5-point scale (0–4), with higher total scores (range 0-28) indicating greater symptom severity and impairment. Age-at-onset and duration of the current diagnostic episode were assessed during the intake interview. Psychiatric comorbidity was assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I and SCID-II; First et al., Citation1996; First et al., Citation1997). Relational problems were assessed with the 64-item, self-report Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz et al., Citation2000). Each item is rated on a five-point scale (0-4) and eight subscale scores calculated, with higher scores reflecting the person’s most salient interpersonal difficulties (Domineering, Vindictive, Cold, Socially avoidant, Non-assertive, Exploitable, Overly Nurturant, and Intrusive). Overall clinical severity was assessed with the 34-item, self-report Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM; Evans et al., Citation2002). Each item is rated on a five-point frequency scale for the past week (0 = Not at all; 4 = Most of the time). Items are grouped into ten subscales with higher scores reflecting greater levels of distress/dysfunction (Subjective Well-Being, Anxious, Depressed, Physical, Trauma, Close, General, Social, Risk to self, and Risk to others).

Treatment beliefs and learning style measures

Helpfulness beliefs were assessed with the 50-item, self-report Psychotherapy Experience Questionnaire (PEX; Sandell et al., Citation2011). Each item is rated on 6-point scale (1-6), and summed to produce five subscales scores (Externalization, Internalization, Catharsis, Support, and Defensiveness) assessing beliefs about particular types of interventions and styles of doing psychotherapy. Higher scores indicate stronger beliefs. Learning style was assessed with the 13-item, self-report Learning Style Inventory - II (LSI-II; Smith & Kolb, Citation1986). Each item asks the respondent to rank order four sentences (1-4) in a way that best describes their typical way of approaching a learning task. Items are grouped into four subscales (Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation) with higher scores indicating more typical way of learning. All scales used in this trial had acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach´s alpha = .68 to .89).

Beliefs about PCT and PFPP

Prior to choosing one of the two treatments, participants in the Choice condition read 500-word descriptions of PCT and PFPP and then answered six questions. The first two questions asked about the perceived credibility of each kind of therapy, followed by two questions about how challenging they perceived the two treatments. These four items were each rated on a 1–9 scale with higher scores indicating stronger beliefs. After choosing a treatment, the participants were asked about the certainty of their treatment choice in a single item with four fixed responses: Certain about PCT; Certain about PFPP; Not certain but chose PCT; and Not certain but chose PFPP. The participants were then asked to rate how important it was for them to have the opportunity to choose a treatment (1 = not important, 9 = extremely important). Finally, the participants were asked two open-ended questions, “What do you find most appealing with the treatment you have selected?” and “Why did you choose that treatment?” and asked to provide their answers in writing.

Statistical Methods

Differences between participants who chose PCT or PFPP were examined using chi-square and independent samples t-tests. Standardized Mean Differences (SMDs) were calculated using www.psychometrica.de according to Cohen’s d, with pooled standard deviations as denominator units (Cohen, Citation1988). Associations between continuous variables and treatment choice were examined using point-biserial correlations rpbis . Variables that significantly differentiated between the PCT and PFPP choice groups were then entered into a logistic regression as independent variables with the choice of therapy type as the dependent variable (0 = PCT, 1 = PFPP). Variables were entered in blocks based on the three categories of measurements used in the trial (1 = clinical measures, 2 = treatment beliefs and learning style measures, and 3 = specific beliefs about PCT and PFPP), in order to separately analyse the added contribution of each block to the regression. Residuals were analysed for the constant and all predictors. As age-at-onset of PD/A was positively skewed, the data were analysed in two ways; first by normalizing this variable to a stanine scale, and second by replacing raw age-at-onset scores exceeding z = 3.29 (p <.001) with raw scores corresponding to z = 3.29 (only two scores were above this value) (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007). No differences were found in the results of the logistic regressions for when age-at-onset was entered as a normalized variable or as a raw score, and so raw scores were used for all analyses. All data was analysed using SPSS for Windows, Version 25.

Qualitative Methods

Qualitative analysis was carried out on the written answers to the two questions about therapy type that were asked immediately after participants chose PCT or PFPP. The written answers were generally brief, 1–2 sentences per question. The first author, blinded to treatment choice, coded responses according to the principles of text interpretation developed by Strauss and Corbin (Citation1998). Specifically, written responses for each question were allocated a code that summarized the original expression as closely as possible, generating a list of codes. During coding, a deliberate effort was made to produce codes that were as close to participant’s formulations as possible and were not specific for, or otherwise linked to, any particular theory. The first reading of the participant’s written answers generated 53 codes that were then compared. Overlapping codes were combined and reformulated with the aim of generating a code list that covered the full range of expressed reasons for the patient’s treatment choice with as few codes as possible. The final coding list contained 22 well-differentiated codes representing the participant’s views about the therapies and their choice (see ). Each code was assigned a value of 0 (view not expressed by the participant) or 1 (view expressed) and then the written answers to the two therapy questions were re-analysed by the first author, and each of the 22 codes was scored for each participant’s answers.

Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

Of the 109 participants who were randomized to the Choice condition in the trial from which this data were drawn, 49 (45%) chose PCT and 60 (55%) chose PFPP as their preferred treatment (χ2(1, 109) = 1.11, p = .29). presents the summary statistics (means, standard deviations, proportions) for the sociodemographic and clinical variables for the two treatment choice groups, as well as the p-values and SMDs for the between-group comparisons. As can be seen in , the two groups were equivalent on all variables with the exception that participants in the PCT group had a longer duration of the current panic episode, and participants in the PFPP group had higher scores on the Trauma subscale of the CORE-OM and the Cold subscale of the IIP.

Table I. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by chosen treatment (PCT or PFPP).

Beliefs About Therapy and Learning Style

provides a summary of the results for the six questions about the two treatments, as well as the participant’s scores on the PEX and LSI-II. Participants gave high credibility ratings to their chosen treatment and lower credibility ratings to the non-chosen treatment. Participants who chose PCT rated PCT as significantly more challenging than PFPP and vice versa. Overall, participants tended to choose the treatment that they perceived as most challenging. Not reported in , 84% of the participants in the PCT group selected the most challenging treatment, thus 16% chose PCT while they believed that PFPP was the more challenging. In the PFPP group, 70% selected the most challenging treatment, thus 30% chose PFPP while they believed PCT was more challenging. These proportions did not differ between groups (χ2(1, 109) = 2.77, p = .09). A smaller, but not significantly different proportion of participants in the PCT versus PFPP groups (63.3% vs 76.7%) indicated that they were certain about their choice of treatment. The mean ratings for the importance of having a choice of treatment in both groups were high with no significant differences between groups.

Table II. Means, standard deviations, and proportions for questions about treatment, beliefs about therapy (PEX) and learning style (LSI) by chosen treatment group.

In respect of the participant’s helpfulness beliefs (PEX) and their preferred learning style (LSI-II), there were several significant differences between the two treatment groups (see ). Specifically, participants who chose PCT scored higher on the Externalization subscale of the PEX and on the Active Experimentation subscale of the LSI-II than participants who chose PFPP. Participants who chose PFPP scored higher than those in the PCT group on the Internalization subscale of the PEX and the Reflective Observation subscale of the LSI-II.

Logistic Regression

A multivariate logistic regression was carried out with the choice of treatment as the dependent variable. The variables included in the blocks all had collinearity statistics within acceptable cut-offs, tolerances (.587 to.976), and variance inflation factors (1.024 to – 1.585), suggesting that the variables functioned as independent predictors of treatment choice. presents bivariate correlations among all the variables included in the regression. Because of how treatment choice was coded (0 = PCT and 1 = PFPP), negative correlations indicate PCT choice and positive correlation indicate PFPP choice. As can be seen the correlations are in the small to moderate range, and in the expected direction. presents the variables included in each block, and the summary statistics for the variables in the final logistic regression model (including all three blocks). As can be seen, the variables together (across blocks) correctly classified 89.9% of the participants into the PCT and PFPP groups (for the overall model: χ2(11, N = 109) = 90.31, p < .001). Of the variables entered, only those in Block 3 (beliefs about the credibility of PCT and PFPP and the challenging nature of PFPP) remained as significant predictors in this multivariate model. In simple terms, after controlling for the sociodemographic and clinical variables, helpfulness beliefs (PEX) and learning style preferences (LSI), all of which differentiated the two treatment groups on a univariate basis, only the credibility and challenging beliefs about the specific treatment were significant predictors of treatment choice, accounting for 85.3% of the correctly classified cases.

Table III. Pairwise correlations among variables significantly associated with treatment choice

Table IV. Logistic regression predicting participants’ choice of treatment.

Qualitative Analyses

presents the 22 codes used by the rater (first author) to categorize the written answers given by the participants when asked to explain why they chose PCT or PFPP, and the number and proportions in each treatment group for whom the codes were assigned. The number of reasons (assigned codes) varied across participants, with a range of 1–8 reasons, and a mean of three reasons per participant. Two of the specific reasons given for the choice of treatment stand out in differentiating the two groups. More than half of the participants who chose PCT (and none of those who chose PFPP) wanted a treatment that involved concrete exercises and other types of practical work around their panic symptoms (code 1). By way of contrast, more than half of the participants who chose PFPP (and only 4 of those who chose PCT), wanted a treatment that focused on identifying the underlying causes of their panic symptoms (code 22). These differences are indirectly reflected in several other codes, namely that participants who chose PCT wanted a treatment focused on current panic symptoms and how to cope with them (codes 2-6), while those who chose PFPP wanted a focus on the links between panic and past or present life experiences, and to talk more about their emotional experiences (codes 17-21).

Table V. Participants’ Reasons for Choosing Treatment.

Discussion

The present study aimed to help fill a gap in the literature with respect to patient treatment preferences using data collected as part of a doubly randomized controlled preference trial of Panic Control Therapy (PCT) and Panic Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy (PFPP) in adults with PD/A. Consistent with previous preference studies, we found little evidence of an association between participant’s sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and their choice of PCT or PFPP. Overall, the strongest associations were found between choice of treatment and the participant’s beliefs about the two treatments, particularly the perceived content/focus of sessions and the credibility of the two approaches, and to a lesser extent their views about psychotherapy more broadly and their preferred learning styles.

Consistent with studies reporting on the relationship between patient characteristics and treatment preferences, there were very few differences between the patients who chose PCT or PFPP in this study. Specifically, participants who chose PCT had a longer mean duration of the current panic disorder episode (d = 0.56). To the extent that episode duration may index the overall severity and impact of a condition, it may be that participants with longer duration episodes of PD/A chose PCT because they thought its narrower focus on current panic symptoms and coping response would bring about more rapid symptom reduction than PFPP. Participants who chose PFPP scored higher on the 2-item posttraumatic distress scale (measuring traumatic intrusions) from the CORE-OM (d = 0.6) and the Cold subscale (measuring feelings of alienation from others) from the IIP (d = 0.38). Again, it is possible that participants with these additional difficulties were more inclined to choose PFPP because they believed this approach addressed the underlying causes of panic symptoms (e.g., trauma and attachment style) and their impact on interpersonal relating. While these inferences are speculative, they are based on the fact that participants read brief descriptions of each treatment before choosing, and these descriptions made clear that PCT was focused on gaining control over current symptoms of panic, while PFPP was focused on understanding the causes of panic, including their relations to (and impact upon) interpersonal relationships.

The present study is the first, to our knowledge, to report how treatment credibility beliefs relate to treatment choice. While our findings point to the overarching importance of treatment credibility to the ultimate choice of treatment, the relationship is likely more complex than the present analyses suggest. Participants in this study tended to choose the treatment they found more credible after reading about both treatments, although they tended to rate both therapies as credible. Thus, it seems likely that there are other factors related to treatment credibility that in turn informed their choice of PCT or PFPP. There is an extensive literature showing that treatment credibility ratings are highly correlated with patient expectancies about the likely outcome of the delivered therapy (Mooney et al., Citation2014). Importantly, this research indicates that treatment credibility, usually assessed during the second or third therapy session, is strongly correlated with symptom change during the first few treatment sessions. In the present study, no outcome expectancy ratings were obtained and credibility ratings were obtained prior to commencing treatment. Of note, prior treatment history was unrelated to choice of either PCT or PFPP in this study. This is interesting given that the majority of participants had a prior history of treatment for PD/A (or some comorbid condition), including psychotherapy. While not directly addressed in this study, it is possible that by reading the 500-word descriptions of the two therapies before making a choice of treatment (which is standard in preference studies), the participants were able to discriminate (or set aside their experiences of) previous treatments from those currently offered and estimate the credibility (and likely outcome) of the offered treatments. This is a finding warranting further investigation, including the usefulness and influence of treatment descriptions on subsequent credibility beliefs, treatment adherence and outcomes.

It is reasonable to assume that credibility ratings reflect not just outcome expectancies but some understanding on the part of the patient about specific targets in therapy sessions (e.g. present-focused problem-solving versus an understanding of the underlying causes of symptoms) and whether this contrast overlaps with their beliefs about how they best learn new skills and change. The present results replicate previous findings for the PEX (Sandell et al., Citation2011), wherein individuals who rated the helpfulness of having concrete goals and a problem solving focus in therapy (PEX Externalizing Scale) tended to prefer cognitive behavioural approaches. In contrast, those who rated the helpfulness of focusing on repeating life patterns and painful memories (PEX Internalizing Scale) tended to prefer psychodynamic approaches. The same held true in this study for PCT (a form of CBT) and PFPP (a form of PDT). This pattern of differences reflecting the participant’s understanding of the foci in the two therapies was further supported by our findings for the participant’s preferred methods of learning generally (assessed by the LSI-II). Participants who chose PCT scored higher on the Active Experimentation subscale indicating a preference for learning through practice, while those who chose PFPP scored higher on the Reflective Observation subscale indicating a preference for learning through observation of, and reflecting on, their own experiences. Interestingly, the majority of participants in this study chose the treatment approach they rated as the more challenging. This may be interpreted in several ways, but perhaps most parsimoniously, participants may want to be challenged on those aspects of functioning they view as most pertinent to achieving change in relation to their panic-related difficulties.

The results of the qualitative analysis lend further support to the argument that participant’s choice of treatment was related to their views about what happens in PCT and PFPP. Consistent with their respective scores on the subscales of PEX and LSI, participants who chose PCT were more likely to explain this choice by reference to PCT’s focus on the present, effective symptom reduction, and an active problem-solving approach. Those who chose PFPP explained this choice by reference to the treatment’s focus on the past and the underlying causes/meaning of their panic symptoms.

Finally, the participant’s sociodemographic/clinical characteristics, beliefs about helpfulness and learning style, and their views on the credibility and challenging nature of the two treatments correctly classified 89.9% of the participants in the two treatment choice groups. The participant’s views about the credibility of both PCT and PFPP, and the challenging nature of PFPP (only) were significant contributors to their final choice, with these variables alone correctly classifying 85.3% of the participants in the two treatment choice groups. Thus, the present findings suggest that a patient’s choice of treatment when offered distinct forms of psychotherapy may be related to the extent to which they view each of the specific treatments as credible. However, as mentioned above, treatment credibility itself is likely associated with a number of different factors including outcome expectancies for that treatment. Further studies are needed involving larger samples, including measures of treatment expectancy in addition to those used here, to evaluate more complex models of the potential influences on patient treatment preferences.

In regards to clinical implications, the results suggest that patients appreciate being given chance to voice their treatment preference, and that therapists should confer with the patient with PD/A about his or her treatment preference to help match the patient’s expectations to the relevant treatment approach. A discussion based on some form of explanation about how the various treatment approaches on offer work on a methodological and theoretical level, the patient´s expectation of therapy, and how he or she believe change might be best achieved given his or her learning style, and general view on therapeutic change.

Future studies from the DRCPT from which the data in the current article is drawn (Sandell et al., Citation2015), will test the associations of choice in moderator analysis of treatment outcome in the four treatment arms (randomised to PCT, randomised to PFPP, self-selected PCT, and self-selected PFPP).

Limitations

The results of the current study must be viewed within the context of certain strengths and limitations. The study benefits from the data being drawn from a randomized clinical trial designed to test the effect of patient treatment choice on outcome, the use of standardized measures of symptoms and beliefs about psychotherapy and learning style, and questions about their reasons for their treatment choice. However, the trial involved the choice between two panic-focused treatments in individuals with a primary PD/A diagnosis, and the choice being made after the participants had read separate 500-word statements about the two treatments. Thus, the present results may not generalize to other designs, treatments, or disorder groups. In a similar vein, although ratings of preference strength were high, it may be that patients with very strong treatment preferences for one particular treatment chose not to participate in the trial in the first place, due to the risk of being randomized to either of the two treatments, either initially or following randomization to a delayed treatment condition. In addition, the participants were recruited from outpatient clinics in Sweden, and reflecting the country as a whole, had a high level of education, and most were vocationally employed. In addition, a large number of statistical analyses were carried out which may have inflated the experiment-wise Type 1 error rate. No correction for the number of analyses was carried out as this was the first to explore which variables were associated with the actual choice of treatment as the dependent variable (as opposed to preference ratings) in a doubly randomized controlled preference trial design. Finally, due to limitations in sample size, no cross validation of the logistic regression was performed.

Conclusions

In this first study on the associations, and stated reasons, for the choice between two forms of psychotherapy for PD/A, the strongest contributors to the choice of treatment were the participant’s helpfullness beliefs about psychotherapy broadly, their learning style, and their beliefs about the two treatments under study. Further studies involving other treatments and more diverse patient groups are needed to help further understand the potential influences on patient treatment preferences.

Data Sharing Statement

In compliance with university, national and European guidelines on the use of patient data, portions of the data from this trial, deidentified for individuals, may be made available to other researchers upon formal request and pending review by the relevant governing authorities.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical Manual of mental disorders, Fourth edition, text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349

- Barlow, D. H., Gorman, J. M., Shear, M. K., & Woods, S. W. (2000). Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 283(19), 2529–2536. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.19.2529

- Brewin, C. R., & Bradley, C. (1989). Patient preferences and randomised clinical trials. BMJ, 299(6694), 313–315. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.299.6694.313

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences. Routledge: Taylor & Francis.

- Craske, M. G., & Barlow, D. H. (2006). Mastery of Your anxiety and panic: Therapist Guide. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780195311402.001.0001

- Dwight-Johnson, M., Sherbourne, C. D., Liao, D., & Wells, K. B. (2000). Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 15(8), 527–534. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x

- Evans, C., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., McGrath, G., Mellor-Clark, J., & Audin, K. (2002). Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: Psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.1.51

- First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Benjamin, L. S. (1996). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I. American Psychiatric Press.

- First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Benjamin, L. S. (1997). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis II. American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

- Heffler, B., & Sandell, R. (2009). The role of learning style in choosing one's therapeutic orientation. Psychotherapy Research, 19(3), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300902806673

- Hofmann, S. G., & Spiegel, D. A. (1999). Panic control treatment and its applications. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 8(1), 3–11. PMCID: PMC3330525. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3330525/pdf/3.pdf.

- Horowitz, L. M., Alden, L. E., Wiggins, J. S., & Pincus, A. L. (2000). Inventory of interpersonal problems Manual. The Psychological Corporation.

- Houle, J., Villaggi, B., Beaulieu, M. D., Lesperance, F., Rondeau, G., & Lambert, J. (2013). Treatment preferences in patients with first episode depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(1-3), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.016

- Imai, H., Tajika, A., Chen, P., Pompoli, A., & Furukawa, T. A. (2016). Psychological therapies versus pharmacological interventions for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10(10), 1–123. CD011170.https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011170.pub2.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the Source of learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs.

- Lindhiem, O., Bennett, C. B., Trentacosta, C. J., & McLear, C. (2014). Client preferences affect treatment satisfaction, completion, and clinical outcome: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(6), 506–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.002

- Markowitz, J. C., Meehan, K. B., Petkova, E., Zhao, Y., Van Meter, P. E., Neria, Y., Pessin, H., & Nazia, Y. (2016). Treatment preferences of psychotherapy patients with chronic PTSD. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(3), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09640

- McHugh, R. K., Whitton, S. W., Peckham, A. D., Welge, J. A., & Otto, M. W. (2013). Patient preference for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(6), 595–602. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12r07757

- Milrod, B. L., Busch, F. N., Cooper, A. M., & Shapiro, T. (1997). Manual of panic focused psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychiatric Press.

- Milrod, B., Chambless, D. L., Gallop, R., Busch, F. N., Schwalberg, M., McCarthy, K. S., Gross, C., Sharpless, B. A., Leon, A. C., & Barber, J. P. (2016). Psychotherapies for panic disorder: A tale of two sites. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77(7), 927–935. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09507

- Moffitt, R., Haynes, A., & Mohr, P. (2015). Treatment beliefs and preferences for psychological therapies for weight management. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(6), 584–596. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22157

- Mooney, T. K., Gibbons, M. B., Gallop, R., Mack, R. A., & Crits-Christoph, P. (2014). Psychotherapy credibility ratings: Patient predictors of credibility and the relation of credibility to therapy outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 24(5), 565–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.847988

- Perreault, M., Julien, D., White, N. D., Belanger, C., Marchand, A., Katerelos, T., & Milton, D. (2014). Treatment modality preferences and adherence to group treatment for panic disorder with agoraphobia. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 85(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-013-9275-1

- Pompoli, A., Furukawa, T. A., Imai, H., Tajika, A., Efthimiou, O., & Salanti, G. (2016). Psychological therapies for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in adults: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, CD011004. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011004.pub2

- Sandell, R., Clinton, D., Frovenholt, J., & Bragesjo, M. (2011). Credibility clusters, preferences, and helpfulness beliefs for specific forms of psychotherapy. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 84(4), 425–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.2010.02010.x

- Sandell, R., Svensson, M., Nilsson, T., Johansson, H., Viborg, G., & Perrin, S. (2015). The POSE study - panic control treatment versus panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy under randomized and self-selection conditions: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 16(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0656-7

- Shear, M. K., Brown, T. A., Barlow, D. H., Money, R., Sholomskas, D. E., Woods, S. W., Gorman, J. M., & Papp, L. A. (1997). Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(11), 1571–1575. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.154.11.1571

- Smith, D. M., & Kolb, D. A. (1986). Use's Guide for the learning-style Inventory. McBer & Company.

- Steidtmann, D., Manber, R., Arnow, B. A., Klein, D. N., Markowitz, J. C., Rothbaum, B. O., Thase, M. E., & Kocsis, J. H. (2012). Patient treatment preference as a predictor of response and attrition in treatment for chronic depression. Depression and Anxiety, 29(10), 896–905. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21977

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage.

- Swift, J. K., Callahan, J. L., Cooper, M., & Parkin, S. R. (2018). The impact of accommodating client preference in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1924–1937. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22680

- Swift, J. K., Callahan, J. L., & Vollmer, B. M. (2011). Preferences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20759

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

- Tompkins, K. A., Swift, J. K., Rousmaniere, T. G., & Whipple, J. L. (2017). The relationship between clients’ depression etiological beliefs and psychotherapy orientation preferences, expectations, and credibility beliefs. Psychotherapy (Chic), 54(2), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000070

- Windle, E., Tee, H., Sabitova, A., Jovanovic, N., Priebe, S., & Carr, C. (2019). Association of patient treatment preference with dropout and clinical outcomes in adult psychosocial mental health interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3750