Abstract

Objective:

Despite increasing research on psychotherapy preferences, the preferences of psychotherapy trainees are largely unknown. Moreover, differences in preferences between trainees and their patients could (a) hinder symptom improvement and therapy success for patients and (b) represent significant obstacles in the early career and development of future therapists.

Method:

We compared the preferences of n = 466 psychotherapy trainees to those of n = 969 laypersons using the Cooper-Norcross Inventory of Preferences. Moreover, we compared preferences between trainees in cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and psychodynamic trainees.

Results:

We found significant differences between both samples in 13 of 18 items, and three of four subscales. Psychotherapy trainees preferred less therapist directiveness (d = 0.58), more emotional intensity (d = 0.74), as well as more focused challenge (d = 0.35) than laypeople. CBT trainees preferred more therapist directiveness (d = 2.00), less emotional intensity (d = 0.51), more present orientation (d = 0.76) and more focused challenge (d = 0.33) than trainees in psychodynamic/psychoanalytic therapy.

Conclusion:

Overall, the results underline the importance of implementing preference assessment and discussion during psychotherapy training. Moreover, therapists of different orientations seem to cover a large range of preferences for patients, in order to choose the right fit.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: The study identifies that preferences for specific therapy activities differ significantly between psychotherapy trainees and laypeople, as well as between trainees of different therapy orientations. The findings highlight the need for psychotherapy trainees to implement preference assessment for self-reflection, for adapting therapy to patient preferences and for discussing disagreements with their patients in order to increase the chances of therapy success and prevent unfavourable therapy processes in the early career of psychotherapists.

In most countries, becoming a psychotherapist requires several years of theoretical and practical training (e.g., American Psychological Association, Citation2014). For example, in order to become a licensed psychotherapist in Germany, one has to have a Master’s Degree in psychology, followed by full-time training of at least three years (PsychThG, Citation2019). During training, trainees change from laypeople in psychotherapy to professionals. Furthermore, at this young age, trainees are expected to grow on a personal and a professional level, mostly through personal practice and supervision (Orlinsky & Rønnestad, Citation2005). The newly formed identity as therapists includes specific preferences and expectations towards certain aspects of psychotherapy (Pieterse et al., Citation2013). However, with the individual development of psychotherapists during the course of their training, as well as prior psychotherapy experience as a general predictor of preference choices (Cooper et al., Citation2019; Speight & Vera, Citation2005), it is unclear how psychotherapy trainee preferences differ from laypeople preferences (and potential patients). Our aim was thus to investigate the preferences of psychotherapy trainees and of laypersons, and to compare commonalities and differences between the two.

Definition of Preferences and Empirical Results

We need to differentiate treatment expectations and preference from one another, despite both sharing a priori stances towards psychotherapy (and its content and external circumstances), as well as a dynamic and multidimensional nature and operations at different levels of consciousness (i.e., un-, sub- or conscious; Constantino et al., Citation2018). Whereas expectations refer to individual predictions of different aspects actually occurring in psychotherapy (i.e., outcome, treatment, or change expectations), preferences are desirable aspects of psychotherapy that people wish for (Swift et al., Citation2011). Preferences can be unrealistic, whereas expectations take into account different anticipated barriers and practical constraints. For example, Hispanic patients might prefer psychotherapy in Spanish, but expect it in English (expectation), if there are few Spanish-speaking therapists in their vicinity. Positive outcome expectations are associated with better outcomes (Constantino et al., Citation2018), and preference accommodation is associated with lower dropout, better alliance and outcomes (e.g., Swift et al., Citation2018). Three subcategories distinguish most preferences (Swift et al., Citation2011, Citation2018). First, people can prefer different forms of treatment, e.g., cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), psychodynamic therapy (PD) or pharmacological treatment. Second, participants might have preferences towards specific characteristics of a psychotherapist, e.g., regarding gender, age or personality. Third, preferences regarding the activities that take place during psychotherapy might differ. Thus, a client could prefer a directive approach by the therapist, a focus on cognitive rather than emotional aspects and homework after each session.

Several studies have pointed out the association between psychotherapeutic experience and preference choices for all three subcategories. Concerning preferences towards psychotherapists’ characteristics, participants with prior psychotherapeutic experience were more likely to express any preference in an open-ended format, whereas non-experienced participants less often indicated specific preferences (Speight & Vera, Citation2005). In a recent study investigating preferences towards therapist characteristics, German participants with prior psychotherapeutic experience were significantly more likely to prefer female therapists (Heinze et al., Citation2022b). For treatment preference, knowledge of psychotherapy and prior psychotherapeutic experience were associated with preferring subsequent psychotherapeutic treatment (Churchill et al., Citation2000; Houle et al., Citation2013; van Schaik et al., Citation2004). Moreover, an early study established that activity preferences of patients changed over the course of psychotherapeutic treatment, i.e. preferences for approval, advice, audience and relationship differed, depending on the treatment phase (Tracey & Dundon, Citation1988).

Most studies on this topic were conducted primarily with laypeople (without therapy experience, e.g. Cooper & Norcross, Citation2016; Heinze et al., Citation2022a) or with mental health patients (e.g., Houle et al., Citation2013; Speight & Vera, Citation2005; van Schaik et al., Citation2004). On the one hand, prior experiences can act as anchors for preferences regarding future treatments. If one has already experienced psychotherapy and its elements, it might be easier to judge the relevance of specific features. Moreover, preferences correspond with past experiences, so that people prefer treatments or therapists they already experienced (van Schaik et al., Citation2004). On the other hand, others suggest that preferences were indicated irrespective of the satisfaction with prior treatment (Kealy et al., Citation2021; Stiggelbout & de Haes, Citation2001). However, only a few empirical studies have investigated the preferences of therapists and how they may differ from non-therapist preferences.

Preferences of Psychotherapists

So far, there has been an abundance of investigations on why therapists choose a specific theoretical orientation. Predictors range from personality traits such as openness and conscientiousness, to organismic vs. mechanistic worldviews or the need for security (e.g., Buckman & Barker, Citation2010; Safi et al., Citation2017; Tartakovsky, Citation2016). Furthermore, several investigations have focused on the treatment preferences of therapists. For example, most therapists who were in psychotherapeutic treatment themselves chose therapists of another theoretical orientation than their own (Norcross et al., Citation2009; Norcross & Grunebaum, Citation2005). Interestingly, psychiatrists showed different treatment preferences when asked whether the treatment is supposed to be for patients suffering from generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) or for psychiatrists suffering from GAD. In comparison to recommendations for general patients, psychiatrists more often recommended psychotherapy, and less often recommended psychopharmacological treatment for themselves (Latas et al., Citation2018).

Regarding activity preferences, there are very few studies at hand that describe psychotherapists’ preferences towards particular methods, approaches and attitudes both during the course of treatment as well as in single sessions. One notable exception is a study conducted by Cooper et al. (Citation2019) who investigated the preferences of mental health professionals and of laypeople. Overall, mental health professionals preferred an approach that resembled psychodynamic therapy, i.e. client directiveness and emotional intensity. In comparison, laypersons preferred an approach more closely resembling CBT, as they preferred significantly more therapist directiveness and less emotional intensity than mental health professionals. The authors argue that therapists should not project their own preferences onto their patients, but rather use questionnaires or interviews to identify the patients’ preferences, and to adjust therapy accordingly. Furthermore, it seems necessary not only to look at treatment preferences, but also at preferences at the micro level (i.e., activity preferences), because approaches of different therapists adapting the same treatment orientation may differ markedly (Katz et al., Citation2021).

Why Psychotherapist Preferences Matter

Despite these findings, other studies on psychotherapist’s activity preferences are rare, leaving us with a highly relevant gap in research for several reasons. Psychotherapists’ own therapy experiences were the primary influence on how treatment and single sessions were conducted within two previous studies (Safran et al., Citation2011; Stewart & Chambless, Citation2007). Given that one’s own choices and behaviours are considered as more common than alternatives (i.e. false consensus effect; Ross et al., Citation1977), therapists who have specific preferences might not adapt their approach to their patients’ needs, but rather to their own preferences. This can be problematic for at least two reasons. First, congruence in alliance ratings (Laws et al., Citation2017; Zilcha-Mano et al., Citation2017), as well as goal consensus and collaboration between therapists and clients were associated with better psychotherapy outcomes and lower symptom levels (Tryon et al., Citation2018). Moreover, a recent study revealed that agreement between patients and their therapists on the helpful aspects of psychotherapy was associated with reductions in symptoms and interpersonal problems (Chui et al., Citation2020). Therefore, consensus and agreement seem to have a beneficial influence on therapy. Second, several meta-analyses underlined that preference accommodation, i.e., whether patients received their preferred psychotherapy, was associated with more positive treatment outcomes, lower dropout as well as higher treatment satisfaction (Lindhiem et al., Citation2014; Swift et al., Citation2011, Citation2018; Windle et al., Citation2020). Therefore, it is necessary to measure therapist preferences and compare them to those of their (potential) patients.

Why Psychotherapy Trainee Preferences Matter

Psychotherapy trainees and their preferences should also be taken into account thoroughly, as trainees often struggle with low self-efficacy, self-doubt and challenging first-time therapy encounters. Psychotherapists early in training experience sessions as stressful and challenging (Orlinsky & Rønnestad, Citation2005; Taubner et al., Citation2010). However, students’ initially low levels of counseling self-efficacy increased throughout the course of their training (Mullen et al., Citation2015). Moreover, self-confidence increased and professional insecurity decreased with the number of years since beginning their training and with the number of supervision sessions received (Junga et al., Citation2019). Similarly, experiences of professional self-doubt and negative personal reaction decreased during CBT training (Odyniec et al., Citation2019).

Given these challenges early in the professional career of a psychotherapist, disagreement over preferences between trainees and patients may become an obstacle for psychotherapy trainees, as the benefits of agreement and consensus (fewer symptoms, better alliance, less dropout) cannot be utilized, potentially increasing the chances of unsuccessful therapies and disappointment during the course of therapy. Since, to the best of our knowledge, there are no empirical investigations of the preferences of psychotherapy trainees so far, we investigated the preferences of psychotherapy trainees and differences between them and laypeople’s preferences (i.e., their potential patients). Thus, our study adds to the previous investigation of mental health professionals by Cooper et al. (Citation2019), by now investigating the activity preferences of both laypeople and psychotherapy trainees. To the best of our knowledge, the Cooper-Norcross Inventory of Preference (C-NIP) is the only validated and standardized questionnaire available in German (Heinze et al., Citation2022a). Referring to previous results with licensed therapists (Cooper et al., Citation2019), we hypothesized that psychotherapy trainees preferred less therapist directiveness and more emotional intensity than laypeople. Furthermore, we explored differences in preferences between trainees of different theoretical orientations (i.e., CBT or PD trainees).

Methods

Procedure and Participants

The study was conducted online, using the survey provider SoSciSurvey (Leiner, Citation2019). Participants gave informed consent and provided their data fully anonymized. The ethics committees of both affiliated universities approved the study (University of Mainz: no. 2017-JGU-psychEK-018; University of Potsdam: no. 13/2020).

We recruited two samples from April until June 2020. First, the convenience sample of laypeople was recruited via the German non-commercial SoSciPanel respondent pool (n = 733; Leiner, Citation2016). The panel included approximately 80,000 participants in total (59% female) who voluntarily signed up to be informed about current studies, with half of them holding a university degree. Our study link was forwarded to 4,000 members of the panel after an independent review of the study design. The link was also forwarded via social media, student mailing lists and the University of Potsdam’s participant recruitment platform (n = 236). Students of the University of Potsdam received course credit, and we randomly selected five participants for a 10€ voucher. Inclusion criteria were sufficient German skills to complete the questionnaire, as well as age ≥ 18 years. After excluding n = 3 participants who were younger than 18, the sample included n = 969 participants (female = 66.97%, n = 649). The mean age was 40.01 (SD = 16.09, range = 18-85), and two thirds had some kind of prior experience with psychotherapy (65.1%; n = 627), for example as (former) patients, acquaintance with a patient or on a professional basis. For more detailed sample characteristics, refer to the C-NIP validation using the same sample (Heinze et al., Citation2022a).

Second, after creating a list of German postgraduate training institutes (including adult/adolescent psychotherapy as well as behavioural, psychodynamic or systemic therapy; n = 210), we contacted all institutes asking them to distribute the link of the online survey to their trainees. Data acquisition took place between January and February 2020. Participants were eligible if (a) they were currently in psychotherapy training and (b) gave informed consent. N = 468 participants completed the online survey. Two were excluded due to a lack of informed consent or not participating in psychotherapy training. Accordingly, the trainee subsample consisted of N = 466 participants (female = 86.48%, n = 403). The mean age was 32.08 (SD = 6.83). 53.21% (n = 248) received training in CBT, 27.25% (n = 127) in PD, and 13.30% (n = 62) in psychoanalysis. Most participants focused on psychotherapy for adults: 66.95% (n = 312). For more details on the trainee sample, refer to Hahn et al. (Citation2022).

As expected, trainees were significantly more often female (86.48% vs. 66.98%, X(2) = 61.67, p < .001) and significantly younger (M = 32.08 vs. 40.01, t(1415.4) = 13.08, p < .001) than the laypersons.

Measures

We used the 18-item Cooper-Norcross Inventory of Preferences (C-NIP; Cooper & Norcross, Citation2016; German translation: Heinze et al., Citation2022a) to measure different activity preferences on an item- or factor-level (e.g., “I would like the therapist to focus on specific goals” vs. “I would like the therapist to not focus on specific goals”). Psychotherapy trainees were asked to indicate their preference as to how a psychotherapist should work with their patients, whereas laypeople indicated their preference as to how a psychotherapist should work with them. Participants indicate their preferences using 7-point semantic differentials with scores ranging from +3 to −3. Zero scores indicate no preference or an equal preference for both options. The authors of the original measure proposed a four-factor structureFootnote1: therapist vs. client directiveness, emotional intensity vs. reserve, past orientation vs. present orientation and warm support vs. focused challenge. Overall, reliabilities ranged from .61 (warm support vs. focused challenge) to .89 (past vs. present orientation). Psychometrically, there is no evidence to support a total score for all 18 items (Cooper & Norcross, Citation2016; Heinze et al., Citation2022a).

Furthermore, laypeople were asked whether they had any prior psychotherapeutic experience. If they indicated yes, participants could specify the source of their experience (as patient, professional, acquaintance or other).

Analytic Approach

To investigate differences between laypeople and trainees, we used t-tests for independent samples. Due to the exploratory nature of the approach used for single C-NIP item analyses, we employed Bonferroni-correction. Therefore, p-values below .003 were considered significant. We indicated effect sizes with Cohen’s d (small: 0.2, medium: 0.5, large: 0.8; Cohen, Citation1992). Moreover, we calculated sum scores for the four factors. Depending on the number of items per factor, preferences can range from +9 to −9 (i.e. past vs. present orientation) or +15 to −15, respectively, with positive scores indicating a preference towards the left-hand option. Furthermore, we investigated the influence of psychotherapeutic experience of participants on preference choices using a one-way ANOVA with trimmed means, due to significant Levene’s tests of homoscedasticity. We compared participants of the layperson sample that indicated having therapy experience or not, and psychotherapists in training (0 = laypeople: no experience, 1 = laypeople: self-reported experience, 2 = trainees). The effect size ξ (Xi) can be interpreted as small (.15), medium (.35) or large (.50; Wilcox & Tian, Citation2011).

We further investigated differences between psychotherapy trainees of different theoretical orientations. We compared CBT trainees (n = 248) with those having a psychodynamic or psychoanalytic focus (n = 189) using t-tests for independent samples. Again, we indicated effect sizes using Cohen’s d. All analyses were performed using the statistic software R v.4.0.2 with lavaan and WRS2 packages (Mair & Wilcox, Citation2020; R Core Team, Citation2020; Rosseel, Citation2012).

Results

Differences between Trainees and Laypersons

We calculated independent t-tests to compare the means of the C-NIP items between the two samples. The results are presented in . Overall, there were significant differences between the two samples in 13 of 18 items. Most differences reached a medium effect size (d > .50), indicating relevant differences in preference choices.

Table I. Item level comparison between samples.

Moreover, we investigated differences in scale means between both samples (). Laypersons preferred significantly more therapist directiveness (M = 6.85 vs. 3.47, p < .001, d = 0.58 [0.46; 0.69]), less emotional intensity (M = 6.07 vs. 9.54, p < .001, d = 0.74 [0.63; 0.86]) and less focused challenge (M = −1.38 vs. −3.07, p < .001, d = 0.35 [0.24; 0.47]) than psychotherapy trainees.

Table II. Scale level comparisons between samples.

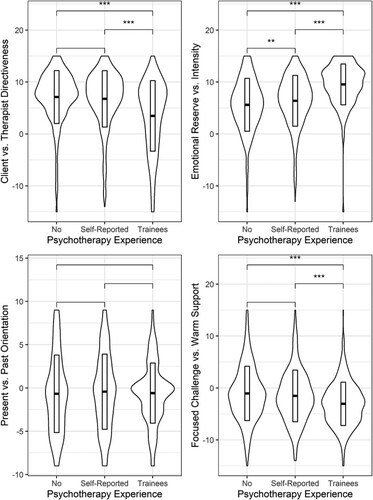

Psychotherapeutic Experience

Additionally, we explored differences between levels of psychotherapeutic experience. We found significant influences of psychotherapeutic experience on therapist vs. client directiveness (F(2, 480.74) = 33.87, p < .001, ξ = .36 [.26; .45]), emotional intensity vs. reserve (F(2, 482.49) = 105.55, p < .001, ξ = .45 [.36; .52]), and warm support vs. focused challenge (F(2, 491.44) = 20.77, p < .001, ξ = .21 [.15; .27]). There was no significant effect on past vs. present orientation (F(2, 472.64) = 0.99, p = .37). shows the means (± 1 SD) and the data distribution of the three groups across all C-NIP subscales. Post-hoc tests showed that laypeople with or without therapy experiences preferred significantly more therapist directiveness than psychotherapy trainees (M = 7.69 or 7.84 vs. 4.55, p < .001). Moreover, participants with and without some kind of experience differed significantly in their preference for emotional intensity (M = 6.88 vs. 5.85, p < .01). Again, trainees preferred significantly more emotional intensity than participants with self-reported experience (M = 6.88 vs. 9.92, p < .001) or participants without prior experience (M = 5.85 vs. 9.92, p < .001). However, trainees preferred less warm support than laypeople with or without therapy experiences (M = 4.97 or 5.23 vs. 4.16, p < .001).

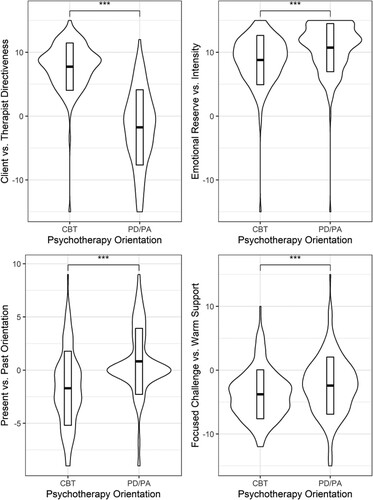

Psychotherapy Orientation

Within the trainee sample, we further investigated whether there were differences in preferences between psychotherapists trained in CBT or in psychodynamic/psychoanalytic therapy. There were significant differences between both orientations on all four C-NIP scales (see ): therapist vs. client directiveness: t(297.81) = 19.45, p < .001, d = 2.00 [1.74; 2.25]; emotional intensity vs. reserve: t(409.47) = 5.29, p < .001, d = 0.51 [0.32; 0.70]; past vs. present orientation: t(424.43) = 7.97, p < .001, d = 0.76 [0.56; 0.96]; warm support vs. focused challenge: t(368.48) = 3.34, p < .001, d = 0.33 [0.14; 0.52]. Specifically, CBT trainees preferred more therapist directiveness, less emotional intensity, more present orientation and more focused challenge than trainees in psychodynamic/psychoanalytic therapy.

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the activity preferences of psychotherapy trainees, and how they differed from the preferences of laypeople. Trainees preferred less therapist directiveness and less emotional intensity during psychotherapy than laypeople. Moreover, laypersons significantly preferred less focused challenge. In subsequent analyses, trainees preferred significantly less therapist directiveness, more emotional intensity and more focused challenge, than laypeople both with or without psychotherapy experience. Laypeople without experience preferred less emotional intensity than laypeople with self-reported experience. Moreover, CBT trainees preferred significantly more therapist directiveness, present orientation and focused challenge, as well as less emotional intensity than trainees trained in psychodynamic and psychoanalytic approaches.

Using a German-speaking trainee sample, we replicated the findings of an English-speaking therapist sample, using the same questionnaire (Cooper et al., Citation2019). In both studies, psychotherapists preferred less therapist directiveness and more emotional intensity than laypeople. However, differing from the original study, trainees in our sample preferred more focused challenge than laypeople, i.e., a more challenging and confrontational approach rather than unconditional support. This might be because, on the one hand, trainees are taught the effectiveness of confrontational methods such as exposition interventions, and subsequently prefer effective treatment options (Mayo-Wilson et al., Citation2014). On the other hand, therapists are often reluctant to implement confrontational interventions, as they have negative beliefs about exposition and worry about distress for both patients and therapists (Deacon & Farrell, Citation2013; Pittig et al., Citation2019). Moreover, demographic differences between the groups of laypeople and trainees might also account for different preferences. Most importantly, our trainee sample primarily included highly educated, female participants in their late twenties to early thirties, due to the postgraduate nature of psychotherapy training, whereas the laypeople sample was more heterogeneous (age ranging from 18 to 85, 67% female). In an earlier validation of the C-NIP, we already found that, within the laypeople sample, women preferred less focused challenge than men, as well as a positive correlation between age and emotional intensity (Heinze et al., Citation2022a). Given these prior results, the difference between the younger sample of trainees preferring less emotional intensity than laypeople, confirms previous findings. However, trainees prefer more focused challenge than laypeople, possibly because trainees are more likely to be aware of the benefits of experience-based methods and exposition, given their theoretical and practical experience. There might be other potential confounds, such as (higher) levels of education, agreeableness, or empathy in the trainee sample (Cooper & Norcross, Citation2016; Heinze et al., Citation2022a). Furthermore, preferences depend on the type and severity of the specific problem that leads people to seek therapy in the first place (Dancey et al., Citation1992; Landes et al., Citation2013). For example, younger participants preferred older therapists for treating universal problems, whereas they preferred younger therapists for problems associated with a lower age (e.g. cyberbullying; Kessler et al., Citation2020), We recommend accounting for such effects in future studies by anchoring the problem type or including patients of various diagnoses.

In our sample, CBT trainees preferred more focused challenge than therapists trained in psychodynamic or psychoanalytic orientations. There were no differences on the scale for past vs. present orientation between laypeople and trainees. However, within the trainee sample, CBT trainees preferred more present orientation, whereas psychodynamic trainees preferred more past orientation. Thus, whereas there is no consensus between trainees of different orientations about a sole focus on either the causes of psychological distress or how a patient’s problems should be approached, our results suggest that laypeople prefer an equal focus on childhood experiences and present situational challenges rather than focusing exclusively on either present or past events. Interestingly, a recent study found that PD therapists are most effective if they incorporate CBT interventions and methods into their therapy (Katz et al., Citation2021). Taken together, undogmatic and individualized approaches for each patient seem to conform to laypeople’s preferences more closely and could promote symptom improvement. Overall, since the authors of the original study did not provide any information on the therapeutic orientation of their mental health professional samples (Cooper et al., Citation2019), our study underlines the distinction in preferences between therapeutic orientations.

Moreover, CBT trainee preferences resembled the preferences in our laypeople sample more closely, i.e., a clear preference for therapist directiveness and slightly less emotional intensity. In line with our results, another study showed that laypeople valued and preferred treatments that were based on a scientific rationale, tested in clinical trials and had proved to be effective (Farrell & Deacon, Citation2016). Moreover, therapists underestimated how much laypeople preferred such scientifically based treatments, especially if the therapists did not value research themselves. Possibly, CBT therapists were more familiar with scientific principles, and therefore closer to the laypeople’s preferences in our sample. However, common factors such as relational aspects or following a treatment rationale were also preferred by laypeople in previous studies (Farrell & Deacon, Citation2016; Swan & Heesacker, Citation2013; Swift & Callahan, Citation2010). As all therapy orientations use common factors, though through different means (Wampold & Imel, Citation2015), common factors might not contribute much to differences in preferences between different therapeutic approaches.

Implications

Psychotherapists should bear in mind that their patients do not necessarily share their preferences and perceptions of therapy. If patient preferences are not met, or if there is no communication about differences, dissatisfaction with therapy, ruptures or dropout may result (Lindhiem et al., Citation2014). Therefore, we recommend implementing preference assessments at the beginning of the therapy, especially for trainees, in order to explore different areas of preference and potential incongruence. Open communication about divergent preferences can help the patient to adjust their expectations, or if necessary, to find a more suitable therapist. Norcross and Cooper (Citation2021) recommend various options for dealing with patient preferences. It is possible to either adopt the preferences, adapt them by adjusting to therapy circumstances, propose alternatives or to refer patients to other therapists. The significant differences between CBT trainees and trainees in psychodynamic and psychoanalytic approaches open up the opportunity to account for a broad range of patient preferences.

So far, it remains unclear whether trainees choose their therapy orientation based on prior preferences, or if preferences form and amplify during the course of psychotherapy training. Furthermore, there is no research on the impact of flexibility or rigidity of therapists’ preferences and their consequences for therapy. However, we encourage training curricula to include reflection on preferences and opportunities, in order to gain experience with interventions that do not necessarily reflect the trainee’s preference. For example, we recommend using role plays with simulated patients, as they may not only improve competence, communication skills and alliance in trainees (Kühne et al., Citation2022), but are a safe space for trying out new behaviours (Kühne et al., Citation2021). We assume that trainees who have learned how to adapt to patient preferences and have experienced both the advantages and challenges of different therapeutic approaches first-hand, are more likely to be flexible and adaptive in future therapies, and thus might benefit from positive effects of patient accommodation, such as lower dropout or enhanced symptom improvement (Swift et al., Citation2018).

On the other hand, preference accommodation and patient personalization for the mere sake of accommodation might be counterproductive for several reasons. First, trainees are already exposed to numerous challenges such as low levels of self-efficacy (Mullen et al., Citation2015), professional insecurity and self-doubts (Junga et al., Citation2019; Odyniec et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the implementation of methods that trainees do not really want could entail even higher workload and error-proneness. Second, just as therapists should accept different beliefs, personalities and preferences on the part of their patients, there are ethical concerns as to whether programmes to challenge therapist preferences are justified. However, limited options and insufficient resources in terms of offering psychotherapy to everyone in need, does not always enable preference accommodation through differences in preference between practitioners, so that it might be necessary for individual therapists to be flexible towards different patient wishes. Third, patient preferences might contradict evidence-based treatment methods, e.g. a patient with phobia preferring not to have exposition treatment. In such cases, preference accommodation might lead to malpractice. Taken together, we are advising trainees to reflect on their preferences and identify areas where accommodation to patient preferences is feasible. To quantify the impact of preference accommodation, we encourage studies that investigate the gains and losses if therapists use a therapeutic approach with which they are less familiar, but which really matches the patient’s preferences.

Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

We recruited two adequately sized samples in order to perform high-power, sophisticated statistical analyses, including a good representation of all psychotherapy trainees in Germany, through contacting every training institute. Despite being one of the first to investigate differences between laypeople and trainees, our study is not without its limitations. First, we conducted a cross-sectional study. Future studies should investigate how preferences change during psychotherapy and over the course of training. Possibly, during the course of training, initial preferences that led to the decision for a specific orientation might intensify, due to a thorough study of the orientation paradigms and methods.

Second, we did not determine the effect of preference disagreements on clinically relevant outcomes such as symptoms, dropout or the therapeutic relationship. However, in a recent study with a patient sample, preferences for active input (i.e. focused challenge, therapist directiveness and emotional intensity) were indeed associated with symptom improvement over the course of psychotherapy (Cooper et al., Citation2021).

Third, although single-fit indices of the C-NIP were acceptable, the confirmatory factor analysis failed to confirm the original factor structure (Cooper & Norcross, Citation2016; Heinze et al., Citation2022a). As in all other studies conducted with the C-NIP (Cooper & Norcross, Citation2016; Özer & Yalçın, Citation2021; Volders, Citation2021), the warm support vs. focused challenge scale only showed acceptable reliability. Specifically, items 17 (challenge vs. not challenge beliefs and views) and 18 (support behaviour unconditionally vs. challenge behaviour) seemed to differ from the other three items statistically and in their content. Therefore, a revision of the C-NIP should focus on its factor structure, and specifically consider these items.

Fourth, there are some limitations regarding our sample. Overall, since the data acquisition took place online, we might have excluded people with little experience or interest in web applications, particularly older people. Moreover, members of the respondent pool signed up voluntarily and thus might be (a) more interested in scientific studies, and (b) more interested in psychological and psychotherapeutic topics, than other individuals. By contrast, the respondent pool more closely approximates the diversity and heterogeneity of the general public than other common recruitment methods such as convenience sampling (Leiner, Citation2016). Furthermore, our study investigated laypeople who are not representative, might not be in need of psychotherapy or might struggle to estimate the impact of given preferences. However, since patients tend to describe their actual psychotherapist rather than indicating preferences (Russell et al., Citation2022), and given that preferences as anticipatory choices need to be assessed prior to psychotherapy by definition (Grantham & Gordon, Citation1986), we decided to recruit a heterogeneous sample of people who could engage in psychotherapy at some point. Moreover, we argue that all preferences should be considered, even if they are not based on experiences or insight into the therapy process. Moreover, controlled trials could investigate the impact of the implementation of preference assessments on process and outcome measures of psychotherapy.

Conclusion

Laypeople and therapists in training, as well as trainees of different treatment orientations, differed significantly in their preferences for psychotherapy activities. Therefore, we highly recommend practitioners in the early phases of their career to assess their patients’ preferences, and to carefully reflect on their own preferences as well. Both parties should discuss significant disagreements in order to manage expectations, lessen the likelihood of alliance ruptures, and increase the chances of better therapy processes and outcomes.

Author Note

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Peter Eric Heinze, University of Potsdam, Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Karl-Liebknecht-Straße 24-25, 14476 Potsdam, Germany. Email: [email protected].

The research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Brian Bloch for his editing of the English.

Disclosure Statement

We declare a potential conflict of interest, as Prof Florian Weck is an advisory editor for Psychotherapy Research.

Notes

1 The factor structure of the C-NIP is still the subject of debate, and multiple models have been proposed (Cooper & Norcross, Citation2016; Heinze et al., Citation2022a). Therefore, we performed confirmatory factor analysis using the trainee sample prior to all other analyses. The results are presented in the supplementary material.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2014). Pursuing a Career in Clinical or Counseling Psychology. https://www.apa.org/education-career/guide/subfields/clinical/education-training

- Buckman, J. R., & Barker, C. (2010). Therapeutic orientation preferences in trainee clinical psychologists: Personality or training? Psychotherapy Research, 20(3), 247–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300903352693

- Chui, H., Palma, B., Jackson, J. L., & Hill, C. E. (2020). Therapist–client agreement on helpful and wished-for experiences in psychotherapy: Associations with outcome. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(3), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000393

- Churchill, R., Khaira, M., Gretton, V., Chilvers, C., Dewey, M., Duggan, C., & Lee, A. (2000). Nottingham counselling and antidepressants in primary care (CAPC) study group (2000). Treating depression in general practice: Factors affecting patients’ treatment preferences. British Journal of General Practice, 50(460), 905–906. https://bjgp.org/content/50/460/905.long

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Constantino, M. J., Vîslă, A., Coyne, A. E., & Boswell, J. F. (2018). A meta-analysis of the association between patients’ early treatment outcome expectation and their posttreatment outcomes. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 473–485. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000169

- Cooper, M., & Norcross, J. C. (2016). A brief, multidimensional measure of clients’ therapy preferences: The Cooper-Norcross Inventory of Preferences (C-NIP). International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 16(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.08.003

- Cooper, M., Norcross, J. C., Raymond-Barker, B., & Hogan, T. P. (2019). Psychotherapy preferences of laypersons and mental health professionals: Whose therapy is it? Psychotherapy, 56(2), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000226

- Cooper, M., van Rijn, B., Chryssafidou, E., & Stiles, W. B. (2021). Activity preferences in psychotherapy: What do patients want and how does this relate to outcomes and alliance? Counselling Psychology Quarterly. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2021.1877620

- Dancey, C. P., Dryden, W., & Cook, C. (1992). Choice of therapeutic approaches as a function of sex of subject, type of problem, and sex and title of helper. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 20(2), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069889208253622

- Deacon, B. J., & Farrell, N. R. (2013). Therapist barriers to the dissemination of exposure therapy. In E. A. Storch, & D. McKay (Eds.), Handbook of Treating variants and complications in anxiety disorders (pp. 363–373). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6458-7_23

- Farrell, N. R., & Deacon, B. J. (2016). The relative importance of relational and scientific characteristics of psychotherapy: Perceptions of community members vs. Therapists. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 50, 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.08.004

- Grantham, R. J., & Gordon, M. E. (1986). The nature of preference. Journal of Counseling & Development, 64(6), 396–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1986.tb01146.x

- Hahn, D., Weck, F., Witthöft, M., & Kühne, F. (2022). What characterizes helpful personal practice in psychotherapy training? Results of an online survey [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Department of Psychology, Johannes-Gutenberg-University Mainz.

- Heinze, P. E., Weck, F., & Kühne, F. (2022a). Assessing patient preferences: Examination of the German Cooper-Norcross Inventory of preferences. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.795776

- Heinze, P. E., Weck, F., & Kühne, F. (2022b). The ideal psychotherapist: What therapist characteristics do laypersons prefer? [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, University of Potsdam.

- Houle, J., Villaggi, B., Beaulieu, M.-D., Lespérance, F., Rondeau, G., & Lambert, J. (2013). Treatment preferences in patients with first episode depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(1-3), 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.016

- Junga, Y. M., Witthöft, M., & Weck, F. (2019). Assessing therapist development: Reliability and validity of the supervisee levels questionnaire (SLQ-R). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(9), 1658–1672. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22794

- Katz, M., Hilsenroth, M., Moore, M., & Gold, J. R. (2021). Profiles of adherence and flexibility in psychodynamic psychotherapy: A cluster analysis. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 31(4), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000226

- Kealy, D., Seidler, Z. E., Rice, S. M., Oliffe, J. L., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., & Kim, D. (2021). Challenging assumptions about what men want: Examining preferences for psychotherapy among men attending outpatient mental health clinics. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 52(1), 28–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000321

- Kessler, E.-M., Rahn, S., & Klapproth, F. (2020). Do young people prefer older psychotherapists? European Journal of Ageing, 17(1), 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-019-00519-9

- Kühne, F., Heinze, P. E., & Weck, F. (2022). Modeling in psychotherapy training: A randomized controlled trial with different perspectives [Manuscript submitted for publication]. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, University of Potsdam.

- Kühne, F., Maaß, U., & Weck, F. (2021). Ist der einsatz simulierter patient_innen zum erwerb psychotherapeutischer fertigkeiten praktikabel? Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 50(3-4), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1026/1616-3443/a000638

- Landes, S. J., Burton, J. R., King, K. M., & Sullivan, B. F. (2013). Women’s preference of therapist based on sex of therapist and presenting problem: An analog study. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 26(3-4), 330–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2013.819795

- Latas, M., Trajković, G., Bonevski, D., Naumovska, A., Vučinić Latas, D., Bukumirić, Z., & Starčević, V. (2018). Psychiatrists’ treatment preferences for generalized anxiety disorder. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 33(1), e2643. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2643

- Laws, H. B., Constantino, M. J., Sayer, A. G., Klein, D. N., Kocsis, J. H., Manber, R., Markowitz, J. C., Rothbaum, B. O., Steidtmann, D., Thase, M. E., & Arnow, B. A. (2017). Convergence in patient–therapist therapeutic alliance ratings and its relation to outcome in chronic depression treatment. Psychotherapy Research, 27(4), 410–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1114687

- Leiner, D. J. (2016). Our research’s breadth lives on convenience samples A case study of the online respondent pool “SoSci panel”. Studies in Communication | Media, 5(4), 367–396. https://doi.org/10.5771/2192-4007-2016-4-367

- Leiner, D. J. (2019). SoSci Survey (Version 3.1.06). SoSci Survey GmbH. https://www.soscisurvey.de

- Lindhiem, O., Bennett, C. B., Trentacosta, C. J., & McLear, C. (2014). Client preferences affect treatment satisfaction, completion, and clinical outcome: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(6), 506–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.002

- Mair, P., & Wilcox, R. (2020). Robust statistical methods in R using the WRS2 package. Behavior Research Methods, 52(2), 464–488. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01246-w

- Mayo-Wilson, E., Dias, S., Mavranezouli, I., Kew, K., Clark, D. M., Ades, A. E., & Pilling, S. (2014). Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(5), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70329-3

- Mullen, P., Uwamahoro, O., Blount, A., & Lambie, G. (2015). Development of counseling students’ self-efficacy during preparation and training. The Professional Counselor, 5(1), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.15241/prm.5.1.175

- Norcross, J. C., Bike, D. H., & Evans, K. L. (2009). The therapist’s therapist: A replication and extension 20 years later. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015140

- Norcross, J. C., & Cooper, M. (2021). Personalizing psychotherapy: Assessing and accommodating patient preferences. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000221-000

- Norcross, J. C., & Grunebaum, H. (2005). The selection and characteristics of therapists’ psychotherapists: A research synthesis. In J. D. Geller, J. C. Norcross, & D. E. Orlinsky (Eds.), The psychotherapist’s own psychotherapy: Patient and clinician perspectives (pp. 201–213). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780195133943.001.0001

- Odyniec, P., Probst, T., Margraf, J., & Willutzki, U. (2019). Psychotherapist trainees’ professional self-doubt and negative personal reaction: Changes during cognitive behavioral therapy and association with patient progress. Psychotherapy Research, 29(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1315464

- Orlinsky, D. E., Rønnestad, M. H., & Collaborative Research Network of the Society of Psychotherapy Research. (2005). How psychotherapists develop: A study of therapeutic work and professional growth. American Psychological Association. https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F11157-000

- Özer, Ö, & Yalçın, İ. (2021). The turkish adaptation of the Cooper-Norcross Inventory of Preferences: A validity and reliability study. Anadolu Journal of Educational Sciences International, 11(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.18039/ajesi.790673

- Pieterse, A. L., Lee, M., Ritmeester, A., & Collins, N. M. (2013). Towards a model of self-awareness development for counselling and psychotherapy training. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 26(2), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2013.793451

- Pittig, A., Kotter, R., & Hoyer, J. (2019). The struggle of behavioral therapists with exposure: Self-reported practicability, negative beliefs, and therapist distress about exposure-based interventions. Behavior Therapy, 50(2), 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.07.003

- Psychotherapeutengesetz [PsychThG]. (2019). https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/psychthg_2020/BJNR160410019.html.

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 4.0.2). R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13(3), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(77)90049-X

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: AnRpackage for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 2. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Russell, K. A., Swift, J. K., Penix, E. A., & Whipple, J. L. (2022). Client preferences for the personality characteristics of an ideal therapist. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 35(2), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2020.1733492

- Safi, A., Bents, H., Dinger, U., Ehrenthal, J. C., Ackel-Eisnach, K., Herzog, W., Schauenburg, H., & Nikendei, C. (2017). Psychotherapy training: A comparative qualitative study on motivational factors and personal background of psychodynamic and cognitive behavioural psychotherapy candidates. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 27(2), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000031

- Safran, J. D., Abreu, I., Ogilvie, J., & DeMaria, A. (2011). Does psychotherapy research influence the clinical practice of researcher–clinicians? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(4), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01267.x

- Speight, S. L., & Vera, E. M. (2005). University counseling center clients' expressed preferences for counselors. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 19(3), 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1300/J035v19n03_06

- Stewart, R. E., & Chambless, D. L. (2007). Does psychotherapy research inform treatment decisions in private practice? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(3), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20347

- Stiggelbout, A. M., & de Haes, J. C. J. M. (2001). Patient preference for cancer therapy: An overview of measurement approaches. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 19(1), 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.220

- Swan, L. K., & Heesacker, M. (2013). Evidence of a pronounced preference for therapy guided by common factors. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(9), 869–879. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21967

- Swift, J. K., & Callahan, J. L. (2010). A comparison of client preferences for intervention empirical support versus common therapy variables. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(12), 1217–1231. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20720

- Swift, J. K., Callahan, J. L., Cooper, M., & Parkin, S. R. (2018). The impact of accommodating client preference in psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1924–1937. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22680

- Swift, J. K., Callahan, J. L., & Vollmer, B. M. (2011). Preferences. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20759

- Tartakovsky, E. (2016). The motivational foundations of different therapeutic orientations as indicated by therapists’ value preferences. Psychotherapy Research, 26(3), 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2014.989289

- Taubner, S., Kächele, H., Visbeck, A., Rapp, A., & Sandell, R. (2010). Therapeutic attitudes and practice patterns among psychotherapy trainees in Germany. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 12(4), 361–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642537.2010.530085

- Tracey, T. J., & Dundon, M. (1988). Role anticipations and preferences over the course of counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.35.1.3

- Tryon, G. S., Birch, S. E., & Verkuilen, J. (2018). Meta-analyses of the relation of goal consensus and collaboration to psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 372–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000170

- van Schaik, D. J. F., Klijn, A. F. J., van Hout, H. P. J., van Marwijk, H. W. J., Beekman, A. T. F., de Haan, M., & van Dyck, R. (2004). Patients’ preferences in the treatment of depressive disorder in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry, 26(3), 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.12.001

- Volders, A. (2021). Déterminer les préférences thérapeutiques d’un·e patient·e: Validation de la version française de l’Inventaire des préférences de cooper-norcross [Master's thesis]. Université de Liège. https://hdl.handle.net/2268.2/12216

- Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203582015

- Wilcox, R., & Tian, T. (2011). Measuring effect size: A robust heteroscedastic approach for two or more groups. Journal of Applied Statistics, 38(7), 1359–1368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664763.2010.498507

- Windle, E., Tee, H., Sabitova, A., Jovanovic, N., Priebe, S., & Carr, C. (2020). Association of patient treatment preference With dropout and Clinical outcomes in adult psychosocial mental health interventions. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(3), 294–302. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3750

- Zilcha-Mano, S., Snyder, J., & Silberschatz, G. (2017). The effect of congruence in patient and therapist alliance on patient’s symptomatic levels. Psychotherapy Research, 27(3), 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1126682