ABSTRACT

Background

Patients with eating disorders and childhood trauma have clinical presentations that make them less suitable for standard eating disorder treatment. This might be due to high levels of shame and self-criticism. Self-compassion can be a mechanism of change, especially for patients with eating disorders and childhood trauma.

Method

A total of 130 patients with or without childhood trauma were admitted to 13 weeks of inpatient treatment and randomized to either compassion-focused therapy or cognitive–behavioral therapy. Self-compassion and eating disorder symptoms were measured every week. The data were analyzed for within-person effects using multilevel modeling.

Results

We did not find a within-person effect of self-compassion on eating disorder symptoms. Rather, the analysis indicated that eating disorder symptoms predict self-compassion in the overall sample. However, we found a stronger within-person relationship between self-compassion and eating disorder symptoms in patients with trauma receiving compassion-focused therapy compared to the remaining patients in the study.

Conclusion

Overall, eating disorder symptoms predicted subsequent self-compassion at a within-person level. Patients with trauma in compassion-focused therapy demonstrated a stronger relationship between self-compassion and eating disorder symptoms. More studies with a cross-lagged design are needed to further illuminate self-compassion as a mechanism of change for these patients.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02649114.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: The findings in this article indicate that self-compassion might be an important focus, particularly in the treatment of patients with eating disorder and a history of childhood trauma.

Public Health Significance

Patients with eating disorders and childhood trauma demonstrate severe eating disorder pathology, high dropout rates, and worse outcomes than other patients with eating disorders. Overall, level of eating disorder symptoms predicted subsequent level of self-compassion on a within-person level. There was a stronger relationship between self-compassion and eating disorder symptoms among patients with a history of childhood trauma randomized to compassion- focused therapy than among the remaining patients. More studies with a cross-lagged design are needed to further illuminate self-compassion as a mechanism of change for these patients.

One of the main issues facing the science of eating disorders is a deficient understanding of the mechanisms that cause, maintain, and change eating disorders (Jansen, Citation2016; Wilson et al., Citation2007). A high probability of poor treatment outcomes in patients with eating disorders has been observed in those who experienced childhood sexual abuse and exposure to violent acts at an early age (Mahon et al., 2001; Rodriguez et al., Citation2005; Vrabel et al., Citation2010). Patients with eating disorders combined with childhood trauma experience an earlier onset of eating disorders, demonstrate worse pathology than non-trauma patients, and have higher dropout rates (Brewerton et al., Citation2007, Citation2020; Castellini et al., Citation2018; Molendijk et al., Citation2017; Scharff et al., Citation2019; Rodriguez et al., Citation2005; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2020; Trottier, Citation2020, Vrabel et al., Citation2010). As such, the complexity of these patients’ clinical presentations makes them less suitable for the treatment with the strongest evidence and the treatment recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, that is, cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) (Fairburn et al., Citation2003; Keel & Brown, Citation2010; National Guideline Alliance (UK), Citation2017).

Research on treatment for patients with eating disorders and a history of childhood trauma is currently lacking (Rijkers et al., Citation2019), and the relevant therapies to treat them have not been empirically tested (Brewerton et al., Citation2020). The scarce knowledge concerning evidence-based therapies for eating disorders and childhood trauma means that even less is known about the mechanisms of change—that is, processes within the patient that lead to treatment outcomes in patients with eating disorders and childhood traumas (Brauhardt et al., Citation2014). Identifying possible mechanisms of change in therapy provides a basis for more reliable, focused, and effective interventions (Kazdin, Citation2007, Citation2009). Thus, there is a need to investigate different therapies with several proposed mechanisms of change.

Compassion-focused therapy for eating disorders (CFT-E) has been developed to cope with specific symptoms of eating disorders and childhood trauma, such as shame and self-criticism, through increasing self-compassion (Gilbert, Citation1998; Goss & Allan, Citation2012, Citation2009; Gale et al., Citation2014; Kelly et al., Citation2013). Self-compassion can be defined in multiple ways, such as sensitivity to suffering accompanied by a commitment to alleviate and prevent it (Gilbert, Citation2014) or relating to one’s suffering with a loving, kind, and nonjudgmental attitude (Neff, Citation2003b). Increasing self-compassion can be an antidote against high levels of shame and self-criticism, especially for patients with a history of trauma (Gilbert & Proctor, Citation2006) and might be a possible mechanism of change.

One study found that a high fear of self-compassion predicted poor treatment response and more severe eating disorder symptoms than for patients with a lower fear of self-compassion (Kelly et al., Citation2013). The study focused on between-person relationships—that is, how differences between patients in self-compassion (the predictor) related to differences in level of eating disorder symptoms (outcome) (Molenaar, Citation2004). Within-person effects examine how each individual changes in relation to himself or herself on a given set of variables, e.g., whether higher (than usual) levels of self-compassion in a person predicts lower levels (than usual) of eating disorder symptoms. It is also possible to investigate the reversed relationship, whether a change in symptoms leads to a change in the process variables.

To the best of our knowledge, only two studies have investigated the within-person effect of self-compassion in eating disorder treatment. Kelly et al. (Citation2020) found that on the days when a person with anorexia nervosa felt more self-compassionate than usual, he/she/they would report fewer eating disorder symptoms. Importantly, they only found an effect among those who reported medium or higher initial self-compassion. Kelly and Tasca (Citation2016) measured levels of shame, self-compassion, self-criticism, and eating disorder symptoms every four weeks across 12 weeks of treatment. The results indicated that when a person scored higher on self-compassion than normal, this led to lower levels of shame and eating disorder symptoms at the following time point.

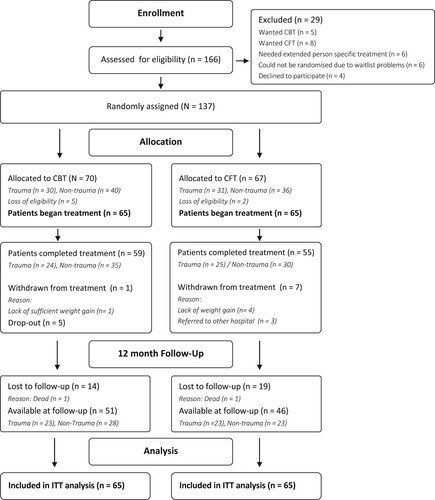

This study is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing CFT-E against CBT. A total of 50% of the patients in each treatment group had a history of childhood trauma (see ). The main outcome of this RCT was that there were no differences between the therapies at discharge. However, at the one-year follow-up, CFT-E retained its impact for patients with a trauma history better than CBT, indicating that the mechanisms of CFT-E are more suited to cases where trauma has been reported (Vrabel et al, under revision).

The current study will expand on the results of (Kelly et al., Citation2020; Kelly & Tasca, Citation2016) and aims to strengthen the existing literature on patients with childhood trauma. We will examine eating disorder symptoms and self-compassion weekly for all patients throughout treatment using multilevel modeling. This method enables the investigation of within-person effects by lagging and detrending. Additionally, we will investigate the two-way interaction effect of trauma and the within-person effect and treatment and the within-person effect. Last, we will investigate the three-way interaction effect of the combination of trauma and treatment categories on the within-person effect of self-compassion on eating disorder symptoms. Specifically, we hypothesize the following:

Self-compassion will predict subsequent eating disorder symptoms over the course of therapy on a within-person level. That is, when a patient’s self-compassion a week is higher than usual (expected) for that patient, eating disorder symptoms the next week will be lower than usual (expected).

The within-person relationship of self-compassion on eating disorder symptoms will be stronger in CFT-E than in CBT.

The within-person relationship of self-compassion on eating disorder symptoms will be stronger in patients with childhood trauma in CFT-E compared to other patients.

The reversed within-person relationship between eating disorder symptoms and subsequent self-compassion will be analyzed.

Methods

Treatment Setting

Participants were referred to treatment at the Department of Eating Disorders at Modum Bad psychiatric hospital in Norway from a local general practitioner’s office or a local psychiatric hospital. The clinic is a nationwide, specialized hospital running an inpatient treatment program for patients with longstanding eating disorders and a history of failing to respond to treatment in local treatment facilities. The unit treats anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and other feeding and eating disorders. For more information on the RCT, please consult Vrabel and colleagues (2019).

Procedures

All patients participated in a pre-care evaluation week for diagnostic evaluation before admission. After identifying their eligibility (see the inclusion and exclusion criteria), written informed consent was obtained. Subjects were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could always withdraw from the study. If they preferred either CFT-E or CBT, they received treatment, but were not included in the RCT. The patients were admitted to 13 weeks of inpatient treatment. Data were collected between spring 2014 and fall 2018. No financial compensation was offered to the participants.

Inclusion Criteria

To be eligible to participate in this study, individuals had to meet the following criteria: (1) adult inpatient (18 years or older) with an eating disorder diagnosis, such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and atypical variants (other specified feeding and eating disorders), according to the Eating Disorder Examination-Interview (Fairburn et al., Citation2008), (2) a non-responder to outpatient treatment, (3) no need for immediate additional treatment (see exclusion criteria), and (4) the provision of informed consent.

Exclusion Criteria

Individuals who met any of the following criteria were excluded from participation in the study: (1) current suicidal risk or psychosis necessitating extensive care, (2) serious substance abuse interfering with treatment, or (3) ongoing trauma (e.g., current involvement in an abusive relationship).

Randomization

Patients completed the baseline measures, and after they provided informed consent, a researcher blind to the study condition conducted the random assignment procedure. A blocked randomization procedure was used to ensure that an equal number of patients with trauma and non-trauma were assigned to each condition. Hence, the blocks were in pairs, and two patients with trauma and two non-trauma patients were randomly assigned to each condition. The probability of each patient ending up in any of the two conditions was kept constant at 0.5. The researchers in the study were blind to the trauma category and the patients’ allocation to the groups. Because of the nature of treatments and procedures, the therapists and patients were not blinded to group allocations. The patients were informed of their group allocations after completing their pre-care evaluations.

Participants

Patients

As shown in , 166 patients were eligible for the study. A total of 29 were excluded from randomization, such as those who wanted a specific therapy (see for the reasons for exclusion). The sample available for statistical analysis included 130 patients, 65 of whom began CBT (trauma: n = 30) and 65 of whom began treatment with CFT-E (n = 31). A total of 137 patients were randomized. Seven lost their eligibility (CBT: n = 5, CFT-E: n = 2; see ), meaning that they did not meet inclusion criteria or met exclusion criteria at the time of admission. There were eight dropouts (CBT: n = 5, CFT-E: n = 3).Footnote1 A total of 126 (97%) were women, and four (3%) were men. The mean age was 30.9 years (SD = 9.7), and the mean duration of illness was 14.2 years (SD = 8.9). There were 37 (28%) patients who met the criteria for anorexia nervosa, 44 (34%) met the criteria for bulimia nervosa, and 44 (34%) patients had symptoms in line with atypical variants (other specified feeding and eating disorders). A total of 97 (75%) patients had previous experience with eating disorder treatment. Most patients, 87 (67%), were either disabled, on sick leave, or out of work. As shown in , the patients had a mean 2.1 axis one diagnosis. As shown in , the most frequent type of childhood trauma was physical and emotional neglect in their childhood.

Therapists and Adherence

A total of nine trained clinical psychologists and one psychiatrist served as therapists in the CBT condition, and six clinical psychologists and three psychiatrists served as therapists in the CFT-E group. The therapists worked in the department at the time of the trial and had formal clinical training in CFT-E or CBT. Each therapist treated 9.3 patients on average (SD = 4.1, Range = 3−16). In the CBT group, the average years of clinical experience were 8.7 (SD = 3.7), and in the CFT-E group, the average years of experience were 9.2 (SD = 5.6). The therapists attended two courses in either CBT or CFT-E, depending on which treatment team they belonged to, and followed detailed treatment manuals. An expert in CBT (Glen Waller) and an expert in CFT-E (Ken Goss) supervised the therapist groups biweekly and ensured the therapists’ fidelity to the respective treatment manuals. All sessions were recorded and were regularly audited to ensure that the treatments were properly implemented.

Treatments

Both treatments lasted approximately 13 weeks. The two treatment conditions were both in closed groups of eight patients. They all received individual therapy in addition to group therapy. There were two to three group sessions per week for each treatment group. The patients received three individual sessions each week that lasted 45 minutes. The therapists used the respective treatment manuals in their delivery of CFT-E and CBT. The treatment manuals had a plan for group and individual sessions every week. For example, in the first weeks of CBT, the patients made a timeline and a case formulation and presented them to the group. In CFT-E, the plan for the initial weeks was an introduction to the CFT-E model and work with one of the main ingredients: compassionate mind training. The patients learned about different aspects of CFT-E, such as attachment theory, and made their own case formulation based on CFT-E principles.

The overall focus in therapy was not modified to accommodate variations in the eating disorder symptomatology. If patients were admitted with a body mass index below 20, measures were taken to secure weight normalization in line with national guidelines for inpatient care for eating disorders (Helsedirektoratet, Citation2017). This did not interfere with the overall therapy focus of CBT or CFT-E. All the interventions, either cognitive or compassion-focused, were tailored to fit all types of eating disorders. Nutrition was also part of the psychoeducative content of both treatment manuals. These have been shown to be important factors in successful eating disorder treatment, regardless of the therapeutic approach (e.g., Geller & Srikameswaran, Citation2006).

However, the two treatments propose different mechanisms of change. The proposed mechanism of change in CBT includes altering deep-rooted cognitions about oneself and coping strategies, such as eating disorder behavior. The aim of CBT is working with patients’ cognitive structures, such as the fear of weight gain, fear of fattening foods, and deeper-rooted cognitive schemas regarding body concepts, body dissatisfaction, and self-worth (Waller et al., Citation2007). Mapping and changing negative automatic beliefs (e.g., “If I get fat, people will think I’m lazy, and I will feel horrible”) and coping strategies (e.g., “I can only eat low-calorie food”) are key focal areas for changing eating disorder symptoms in CBT.

CFT-E aims to increase self-compassion that can enable patients to challenge their self-criticism and shame. The objective of CFT-E is to help patients regulate their affect systems through compassionate mind training and self-compassion (Goss & Allan, Citation2010, Citation2012, 2014). Compassionate mind training trains patients to feel calm and safe through techniques such as mindfulness and by becoming more self-compassionate toward themselves (Goss & Allan, Citation2010, Citation2012, 2014). It is hypothesized that one can work effectively with core symptoms of an eating disorder like shame, self-criticism, and self-directed hostility by practicing self-compassion.

Measurements

Patients in the study were first admitted to a pre-evaluation week, during which they were assessed with the Eating Disorder Examination-Interview 12.0/17.0 (Fairburn et al., Citation2008) by trained therapists and advanced psychology students to determine an eating disorder diagnosis (Fairburn et al., Citation2008; Rø et al., Citation2015). Both versions 12.0 and 17.0 were used, first 12.0 and later 17.0, since a validated Norwegian version of the EDE-I was launched during the project period (2016).

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) was used to assess childhood trauma (Bernstein et al., Citation2003). This questionnaire measures childhood maltreatment in five areas. After the reverse coding of some items, the items can be added to obtain a total CTQ score. To identify possible cases of childhood trauma and differentiate between no trauma and trauma, we used this instrument as a categorical measure with the recommended scoring options by Walker et al. (Citation1999). Patients who scored ≥ 8 on the sexual abuse, physical abuse, or physical neglect subscale; ≥ 10 on the emotional abuse subscale; or ≥ 15 on the emotional neglect subscale were placed in the trauma group. Patients with childhood trauma were randomized as trauma patients, regardless of their current PTSD diagnosis. This is in line with leading trauma theory, which argues that prolonged and repeated trauma exposure in childhood has more extensive consequences than a single traumatic event in adulthood (Herman, Citation1992; Cloitre et al., Citation2009; Felitti et al., Citation1998; Felitti et al., Citation2019). In addition, the CTQ has good psychometric properties (Bernstein et al., Citation2003).

Weekly Measures

The patients filled out weekly outcome and process questionnaires every Monday during the 13-week treatment period. The self-compassion scale (Neff, Citation2003a) was used to measure self-compassion as a weekly process measure. In our study, we chose to use only its self-kindness subscale, as self-kindness has been considered to tap the construct of self-compassion as the final product of compassionate mind training (the main component in CFT-E). This is in line with other prominent researchers in the field (e.g., Gilbert & Procter, Citation2006). The self-compassion scale had five claims rated regarding how often they felt true to the patients, such as “I try to be understanding and patient toward those aspects of my personality that I do not like” and “When I am going through a very hard time, I give myself the caring and tenderness I need.” The items are rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, according to which a high global score indicates high self-compassion. The self-compassion scale demonstrates good construct, content, and convergent validity and good test–retest reliability (Neff, Citation2003a). Cronbach’s alpha varied between 0.82 and 0.94 on the self-compassion scale across weekly measurements.

Eating disorder symptoms as weekly outcomes were measured by the Eating Disorder Examination Self-Report Questionnaire 6.0 (EDE; Fairburn & Beglin, Citation2008). The questionnaire is based on a diagnostic semi-structured interview, the EDE 12.0 (Cooper & Fairburn, Citation1987). Both versions 12.0 and 17.0 were used since a validated Norwegian version of the EDE-I was launched during the project period (2016). For weekly assessments, the patients were questioned in the last seven days (instead of the last 28 days). EDE consists of four subscales: “fear of eating,” “fear of weight,” “fear of figure,” and “restriction.” The global score was used as an outcome measure in this study. The items are rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1–6, where a high score indicates high eating disorder symptoms. The Norwegian translation has satisfactory psychometric properties and satisfactory internal consistency (Rø et al., Citation2015). Cronbach’s alpha varied between 0.89 and 0.91 for the EDE global score across weekly measurements.

Missing data

In all, 26.8% of the weekly scores were missing for eating disorder symptoms, and 17.4% were missing on the self-compassion weekly scores. The MCAR (Missing Completely at Random) test (Little, Citation1988) was not significant for either eating disorder symptoms (χ² [755] = 782.08, p < 0.240) or self-compassion (χ² [513.15] = 587, p < 0.902), indicating that the data could be considered to be missing at random. As some data were missing, the maximum likelihood estimation was used, in which individuals contribute the proportion of data they have available in the estimation procedure, being the state-of-the-art approach in scenarios with missing data (Schafer & Graham, Citation2002).Footnote2

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS Version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York). Longitudinal multilevel modeling (MLM) was used to investigate our hypotheses (Curran & Bauer, Citation2011).

The mean number of measurements across treatment weeks was 9.7 for self-compassion and 8.6 for eating disorder symptoms. Intraclass correlations (ICCs) were calculated for all variables using raw scores at the available assessment points. Higher ICCs indicate that scores varied between participants to a greater degree than their within-person variations over time (i.e., during treatment; Snijder & Bosker, Citation2011). The ICC analysis indicated that for self-compassion, 33% of the variance could be accounted for by between-person differences and 66% by within-person variations. For eating disorder symptoms, 22% could be accounted for by between-person differences and 77% by within-person variations. Thus, there was a large within-person variation in the weekly measures, making them suitable for within-person analyses.

The time-varying predictors were disaggregated, that is, the within-person variability was separated from the between-person variability (Curran & Bauer, Citation2011). Disaggregation enables an examination of within-individual processes of change that are not contaminated with between-person variability (Paccagnella, Citation2006; Enders & Tofighi, Citation2007; Curran & Bauer, Citation2011). The method of detrending was chosen because we expected the time-varying predictor to change during therapy (Curran & Bauer, Citation2011; Wang & Maxwell, Citation2015). Thus, the within-person deviations were calculated as the difference between a time-specific observation and the trend line for the variable (i.e., the expected value given a linear change in the variable). The estimated differences on the time-varying predictors at the first measurement occasion were used to represent their between-person component.

The models were built by starting with only a fixed intercept and no random effects. Random intercepts and random slopes were then added if they significantly increased model fit, which they did for eating disorder symptoms and self-compassion. We tested for curvilinearity with the log likelihood (−2LL) and obtained a marginal better fit compared to the linear model. However, a visual inspection of the individual slopes did not reveal a clear impression of curvilinearity. Subsequently, we opted for the linear model, considering the principle of parsimony. Models were compared for model fit using the Aikaikes and −2LL criteria. The first-order autoregressive (AR1) covariance structure of the residuals provided the best model fit for self-compassion, and the first order autoregressive (DIAG) covariance structure of the residuals provided the best fit for eating disorder symptoms.

Our first model was built by including only time as a predictor of eating disorder symptoms to investigate overall changes. Furthermore, we included the lagged within-person predictor (self-compassion) to investigate the effect on eating disorder symptoms in the overall sample. In our second model, we added the two-way interaction effect of treatment group to investigate whether there was a difference in within-person and between-person effects in treatment groups. In our third model, we investigated the three-way interaction effect of trauma and treatment groups on the within-person effect of self-compassion on eating disorder symptoms. We also investigated the reversed effects, i.e., whether eating disorder symptoms predicted self-compassion. Last, to clarify the results of the three-way interaction, a post-hoc analysis was performed to investigate the within-person relationship between eating disorder symptoms and self-compassion in all four treatment conditions (see syntax and table in the supplements) in the RCT.

Results

No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups concerning baseline characteristics, except for the duration of previous treatment before admission (see ). The patients randomized into CFT-E had received significantly more treatment than the patients randomized into CBT prior to admission.

Table 1. Sample and group characteristics at pre-treatment.

Table II. Number of diagnosis, trauma categories and trauma severity.

Overall Change and Between-person Effects

The overall level of self-compassion increased significantly during therapy (B = 0.05, SE = 0.01, t(121.3) = 6.1, p = 0.001). The overall level of eating disorder symptoms decreased (B = −0.06, SE = 0.11, t(121.3) = −5.91, p = 0.001). There was a negative between-person effect of self-compassion on eating disorder symptoms (B = −1.01, SE = 0.16, t(120.2) = −6.77, p = 0.001), meaning that the level of self-compassion at the start of therapy was negatively related to the level of eating disorder symptoms throughout therapy.

Testing Hypotheses

Our first model (see ) tested our first hypothesis, whether there was a within-person effect of self-compassion on subsequent eating disorder symptoms in the overall sample. This was not significant (B = 0.01, SE = 0.04, t(712.9) = 0.38, p = 0.706), meaning we did not find support for this hypothesis.

Table III. SC: Fixed effect estimates and variance for models by between- and within-person by treatment and trauma for eating disorder symptoms in MLM.

Table IV. EDE: Fixed effect estimates and variance for models by between- and within-person by treatment and trauma for self-compassion in MLM.

Our second model tested the two-way interaction. That is, the within-person relationship was stronger in CFT-E than in CBT (second hypothesis). This was not significant (B = −0.11, SE = 0.07, t(706.9) = −1.49, p = 0.136).

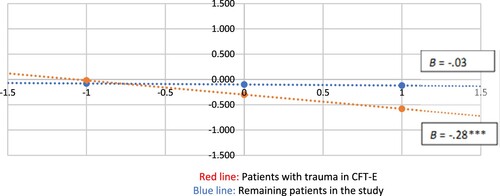

Our third model investigated the three-way interaction, that is, whether patients with trauma in CFT-E had a stronger within-person relationship than the remaining patients in the study (third hypothesis). To understand the direction of the effect, we coded trauma = 0, non-trauma = 1, CFT-E = 0, CBT = 1. This hypothesis was supported (B = −0.70, SE = 0.15, t(740.7) = −4.70, p = 0.001); there was a stronger negative within-person relationship between self-compassion and subsequent eating disorder symptoms among patients in CFT-E with childhood trauma than among the remaining patients. To illustrate this three-way interaction, the results of regressing the within-person symptom scores on the within-person self-compassion scores in the CFT-E with trauma patients versus the remaining patients, are presented in .

Examining the Reversed Effects

In the overall sample, there was a within-person effect of eating disorder symptoms on self-compassion (B = −0.09 SE = 0.31, t(509.4) = −3.0, p = 0.003) (See ). We also explored whether the within-person effect of eating disorder symptoms on self-compassion was stronger in CFT-E than in CBT. This two-way interaction was non-significant (B = −0.24 SE = 0.06, t(722.4) = .41, p = 0.681), meaning that there were no differences between the therapies in the within-person effect of eating disorder symptoms on self-compassion.

Last, we examined the three-way interaction of the treatment group, trauma category and eating disorder symptoms on self-compassion. This interaction was significant (B = 0.24, SE = 0.12, t(434.0) = 2.0, p = 0.04). Given that the overall effect of symptoms on self-compassion is negative, this positive effect means that the effect for the total sample is attenuated in the patients with trauma who receives CFT-E.

Discussion

The overall level of self-compassion increased, and the overall level of eating disorder symptoms decreased significantly during therapy. Notably, given the longevity of illness and the level of care (inpatient), these patients, on average, experienced symptom relief over therapy.

However, we did not find support for our first hypothesis that the within-person level of self-compassion would predict subsequent levels of eating disorder symptoms for all patients in the sample. Rather, analyses indicated that eating disorder symptoms predicted self-compassion on a within-person level. This might indicate that changing eating disorder symptoms, like normalizing eating behavior, gaining weight, and stopping purges and vomiting, is a significant first step to accessing self-compassion. Perhaps when patients stop their eating disorder behavior and work with issues related to body and weight, they are more able to direct compassion toward oneself. In this way, improvement on eating disorder symptoms might be seen as a way of “unlocking” (the access of) self-compassion.

Our second hypothesis, that there would be a stronger within-person relationship of self-compassion on eating disorder symptoms in CFT-E, was not supported. Many studies have investigated various therapies and outcomes on eating disorder measures. Most studies on the effect of eating disorder therapy have found that therapies perform equally well as long as there is a focus on eating disorder behavior (e.g., Zipfel et al., Citation2014; Poulsen et al., Citation2014; Fairburn et al., Citation2003). This corroborates our analysis, indicating that the effect (less eating disorder therapy and more self-compassion) was present regardless of CFT-E or CBT. However, given that only CFT-E actively addresses and works with self-compassion, we expected that this group would increase more. Perhaps for most patients with eating disorders, self-compassion is a generic process that increases due to symptom relief.

As stated in the introduction, patients with childhood trauma might have a particular effect of a self-compassion focus given that they are more prone to self-criticism and shame (e.g., Tripp & Petrie, Citation2001; Gilbert, Citation1998; Goss & Allan, Citation2009). Thus, our third hypothesis investigated the three-way interaction of trauma and treatment on the within-person relationship of self-compassion with eating disorder symptoms. This was supported. The reversed effect was also significant and positive, indicating that for patients with childhood trauma in CFT-E, the relationship between eating disorder symptoms and self-compassion is stronger than among the rest of the patients in this study. In other words, our analysis indicated that patients with childhood trauma in CFT-E were less sensitive to preceding changes in symptoms than the remaining patients. This supports the theory that these patients need a focus on self-compassion and compassionate mindfulness in their recovery process, as they seem more prone to high levels of shame and self-critique, which, in turn, may trigger eating disorder behaviors. Therefore, self-compassion can be important in stopping the vicious cycle for these patients. The reversed effect, that is, that eating disorder behavior also predicted self-compassion, highlights the importance of working with both eating disorder behaviors and self-compassion in therapy.

In summary, our analysis indicated that, in the overall sample, eating disorder symptom change precedes self-compassion. For patients with childhood trauma in CFT-E, there is a stronger relationship between self-compassion and eating disorder symptoms than among the remaining patients. Post-hoc analyses indicated that the patients with childhood trauma in self-compassion was the only group in which self-compassion predicted eating disorder symptom reduction. Although the sample size is small in the post-hoc analysis and should be interpreted with caution, the findings indicate that self-compassion has a role in symptom improvement among these patients. This can be viewed in conjunction with the main outcome of this study: Patients with childhood trauma in CFT-E retain their improvement at the one-year follow up better than patients in CBT (Vrabel et al, under revision).

CBT could also have led to heightened levels of self-compassion in an indirect way through changed cognitive beliefs or through other mechanisms that we did not measure. Other treatment factors may be involved, such as therapists’ compassionate attitudes; non-negotiable, mandatory elements in therapy (Geller & Srikameswaran, Citation2006); or positive bieffects of sharing in group therapy. For some patients, social support in a therapy group is important as they eat and do group therapy together. This opens many arenas to practice vulnerability and to give and receive support. This holds for both treatment conditions, as all patients engage and are encouraged to share in group sessions; thus, it is less likely that this has affected the results. Additionally, alliance could be a confounding variable nested within therapists or therapy groups; however, a recent simulation study argues that within-patient effects are mostly unaffected by therapist effects (Falkenström et al., Citation2020).

To establish self-compassion as a mechanism of change, there is a need for more studies investigating within-person relationships in a structural, dynamic model (see limitations). As stated in the supplement, a more dynamic model was run (Latent Growth Curve with Structured Residuals LCM–SR; Curran et al., Citation2014), but resulted in estimation problems. The results were, however, pointing in the same direction as the MLM-analyses (i.e., eating disorder symptoms predicts self-compassion), which further increases the robustness of the findings in this study.

Strengths and limitations

This study is a part of an RCT in a naturalized setting, which enables the generalizability of findings to other treatment contexts. To the best of our knowledge, no RCT has been completed on self-compassion as a mechanism of change within an eating disorder treatment context for patients with a defined childhood trauma. The use of repeated weekly measures enables statistical analyses that can look beyond pre- and post-treatments and investigate mechanisms of change. In turn, this can guide important interventions in therapy with a complex patient group.

This study used MLM to disaggregate between-person effects from within-person effects to investigate the mechanisms of change. There are several other ways to investigate the mechanisms of change in longitudinal models (see supplements for a review on the method selection process). Some models enable a direct comparison of constructs using structured residuals and cross-lagged effects, such as the LCM-SR and Random-Intercept with a Cross-Lagged Panel Model (RI–CLPM; Hamaker et al., Citation2015). All three analyses were conducted on the dataset. However, due to the complexity of LCM-SR analyses, our data was insufficient with its limited sample size which resulted in estimation problems. Thus, MLM was chosen. We investigated the reversed effects and performed post-hoc analyses to remedy the lack of a more dynamic statistical model. Although LCM–SR did yield Heywood cases, the direction of the constructs was in line with the results of the MLM-analysis (i.e., eating disorder symptoms predicted self-compassion in the total sample. The three-way interaction analysis is unfortunately not supported for LCM-SR as of now). However, in future RCTs, one should obtain higher sample size and/or use more frequent measurements when aiming to investigate change mechanisms.

The study was pre-registered in Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02649114?cond=Eating+Disorders&cntry=NO&draw=2&rank=4 NCT02649114. Data is available upon request.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (39.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Tonje Kvande Nielsen, Mari Sandnes Vehus, Nina Monclair and Rebekka Hedenstrøm for contributing to the diagnostic work.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2022.2149363.

Notes

1 We monitored adverse events, closely monitoring patients throughout therapy and at the one-year follow-up. Two deaths were reported in this sample, but the incidents were not related to the treatment and do not qualify as adverse events as defined by clinicaltrials.gov.

2 Data are available upon request. Kindly contact the corresponding author for more information.

References

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

- Brauhardt, A., de Zwaan, M., & Hilbert, A. (2014). The therapeutic process in psychological treatments for eating disorders: A systematic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(6), 565–584. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22287

- Brewerton, T. D. (2007). Eating disorders, trauma, and comorbidity: Focus on PTSD. Eating Disorders, 15(4), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260701454311

- Brewerton, T. D., Perlman, M. M., Gavidia, I., Suro, G., Genet, J., & Bunnell, D. W. (2020). The association of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder with greater eating disorder and comorbid symptom severity in residential eating disorder treatment centers. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(12), 2061–2066. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23401

- Castellini, G., Lelli, L., Cassioli, E., Ciampi, E., Zamponi, F., Campone, B., Monteleone, A. M., & Ricca, V. (2018). Different outcomes, psychopathological features, and comorbidities in patients with eating disorders reporting childhood abuse: A 3-year follow-up study. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(3), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2586

- Cloitre, M., Stolbach, B. C., Herman, J. L., Kolk, B. v. d., Pynoos, R., Wang, J., & Petkova, E. (2009). A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(5), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20444

- Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. (1987). The eating disorder examination: A semi-structured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198701)6:1<1::AID-EAT2260060102>3.0.CO;2-9

- Curran, P. J., Howard, A. L., Bainter, S. A., Lane, S. T., & McGinley, J. S. (2014). The separation of between-person and within-person components of individual change over time: A latent curve model with structured residuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(5), 879–894. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035297

- Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2011). The disaggregation of within-person and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 583–619. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356

- Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

- Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(5), 509–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00088-8

- Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & O'Connor, M. (2008). Eating disorder examination. In C. G. Fairburn (Ed.), Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders (16th ed.) (pp. 265–309). Guilford Press.

- Fairburn, C. G., & Beglin, S. J. (2008). Eating disorder examination questionnaire. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy and Eating Disorders, 309, 313.

- Falkenström, F., Solomonov, N., & Rubel, J. A. (2020). Do therapist effects really impact estimates of within-patient mechanisms of change? A monte carlo simulation study. Psychotherapy Research, 30(7), 885–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1769875

- Falkenström, F., Solomonov, N., & Rubel, J. A. (2022). How to model and interpret cross-lagged effects in psychotherapy mechanisms of change research: A comparison of multilevel and structural equation models. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 90(5), https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000727

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (2019). REPRINT OF: Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(6), 774–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.001

- Gale, C., Gilbert, P., Read, N., & Goss, K. (2014). An evaluation of the impact of introducing compassion focused therapy to a standard treatment programme for people with eating disorders. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1806

- Geller, J., & Srikameswaran, S. (2006). Treatment non-negotiables: Why we need them and how to make them work. European Eating Disorders Review, 14(4), 212–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.716

- Gilbert, P. (1998). What is shame? Some core issues and controversies. In P. Gilbert, & B. Andrews (Eds.), Series in affective science. Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture (pp. 3–38). Oxford University Press.

- Gilbert, P. (2009). Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 15(3), 199. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.107.005264

- Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12043

- Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism: Overview and pilot study of a group therapy approach. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(6), 353–379. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.507

- Goss, K., & Allan, S. (2009). Shame, pride and eating disorders. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(4), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.627

- Goss, K., & Allan, S. (2010). Compassion focused therapy for eating disorders. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 3(2), 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2010.3.2.141

- Goss, K., & Allan, S. (2012). An introduction to compassion-focused therapy for eating disorders (CFT-E). In J. R. E. Fox, & K. P. Goss (Eds.), Eating and its disorders (pp. 303–314). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118328910.ch20

- Goss, K., & Allan, S. (2014). The development and application of compassion-focused therapy for eating disorders (CFT-E). British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12039

- Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. P. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

- Helsedirektoratet. (2017). Nasjonal faglig retningslinje for tidlig oppdagelse, tidlig utredning og behandling av spiseforstyrrelser. https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/spiseforstyrrelser.

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490050305

- IBM Corp. (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (version 25.0 armonk). IBM Corp.

- Jansen, A. (2016). Eating disorders need more experimental psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 86, 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.08.004

- Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432

- Kazdin, A. E. (2009). Understanding how and why psychotherapy leads to change. Psychotherapy Research, 19(4–5), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802448899

- Keel, P. K., & Brown, T. A. (2010). Update on course and outcome in eating Disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(3), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12006

- Kelly, A. C., Waring, S. V., & Dupasquier, J. R. (2020). Most women with anorexia nervosa report less eating pathology on days when they are more self-compassionate than usual. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(1), 133–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23185

- Kelly, A. C., Carter, J. C., Zuroff, D. C., & Borairi, S. (2013). Self-compassion and fear of self-compassion interact to predict response to eating disorders treatment: A preliminary investigation. Psychotherapy Research, 23(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.717310

- Kelly, A. C., & Tasca, G. A. (2016). Within-persons predictors of change during eating disorders treatment: An examination of self-compassion, self-criticism, shame, and eating disorder symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(7), 716–722. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22527

- Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

- Molenaar, P. C. (2004). A manifesto on psychology as idiographic science: Bringing the person back into scientific psychology, this time forever. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research & Perspective, 2(4), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15366359mea0204_1

- Molendijk, M. L., Hoek, H. W., Brewerton, T. D., & Elzinga, B. M. (2017). Childhood maltreatment and eating disorder pathology: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 47(8), 1402–1416. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003561

- National Guideline Alliance (UK). (2017). Eating Disorders: Recognition and Treatment. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

- Neff, K. D. (2003a). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

- Neff, K. D. (2003b). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

- Paccagnella, O. (2006). Centering or not centering in multilevel models? The role of the group mean and the assessment of group effects. Evaluation Review, 30(1), 66–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X05275649

- Poulsen, S., Lunn, S., Daniel, S. I. F., Folke, S., Mathiesen, B. B., Katznelson, H., & Fairburn, C. G. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of psychoanalytic psychotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(1), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121511

- Rijkers, C., Schoorl, M., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2019). Eating disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 32(6), 510–517. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000545

- Rodríguez, M., Pérez, V., & García, Y. (2005). Impact of traumatic experiences and violent acts upon response to treatment of a sample of Colombian women with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 37(4), 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20091

- Rosenbaum, D. L., White, K. S., & Artime, T. M. (2020). Coping with childhood maltreatment: Avoidance and eating disorder symptoms. Journal of Health Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105320937068

- Rø, Ø, Reas, D. L., & Stedal, K. (2015). Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) in Norwegian adults: Discrimination between female controls and eating disorder patients. European Eating Disorders Review, 23(5), 408–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2372

- Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147

- Scharff, A., Ortiz, S. N., Forrest, L. N., & Smith, A. R. (2019). Comparing the clinical presentation of eating disorder patients with and without trauma history and/or comorbid PTSD. Eating Disorders, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2019.1642035

- Snijders, T. A., & Bosker, R. J. (2011). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Tripp, M. M., & Petrie, T. A. (2001). Sexual abuse and eating disorders: A test of a conceptual model. Sex Roles, 44(1‒2), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011081715575

- Trottier, K. (2020). Posttraumatic stress disorder predicts non-completion of day hospital treatment for bulimia nervosa and other specified feeding/eating disorder. European Eating Disorders Review, 28(3), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2723

- Vrabel, K. R., Hoffart, A., Rø, Ø., Martinsen, E. W., & Rosenvinge, J. H. (2010). Co-occurrence of avoidant personality disorder and child sexual abuse predicts poor outcome in long-standing eating disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 119(3), 623. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019857

- Vrabel, K. R., Wampold, B., Quintana, D. S., Goss, K., Waller, G., & Hoffart, A. (2019). The modum-ED trial protocol: Comparing compassion-focused therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in treatment of eating disorders with and without childhood trauma: Protocol of a randomized trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01638

- Vrabel, K. R., Waller, G., Goss, K., Wampol, B., Kopland, M., & Hoffart, A. (submitted). Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus compassion focused therapy for adult patients with eating disorder with and without childhood trauma: A randomized controlled trial in an intensive treatment setting.

- Walker, E. A., Gelfand, A., Katon, W. J., Koss, M. P., Von Korff, M., Bernstein, D., & Russo, J. (1999). Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. The American Journal of Medicine, 107(4), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00235-1

- Waller, G., Cortosphine, E., Hinrichsen, H., Lawson, R., Mountford, V., & Russell, K. (2007). Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A comprehensive treatment guide. Cambridge University Press.

- Wang, L. P., & Maxwell, S. E. (2015). On disaggregating between-person and within-person effects with longitudinal data using multilevel models. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000030

- Wilson, G. T., Grilo, C. M., & Vitousek, K. M. (2007). Psychological treatment of eating disorders. American Psychologist, 62(3), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199

- Zipfel, S., Wild, B., Groß, G., Friederich, H.-C., Teufel, M., Schellberg, D., Giel, K. E., de Zwaan, M., Dinkel, A., Herpertz, S., Burgmer, M., Löwe, B., Tagay, S., von Wietersheim, J., Zeeck, A., Schade-Brittinger, C., Schauenburg, H., & Herzog, W. (2014). Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 383(9912), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61746-8

Appendix A

Data Transparency Statement

The data reported in this manuscript were collected as part of a randomized controlled trial from 2014–2018. MS 1 (Vrabel et al, Citation2019) is a trial paper describing a randomized controlled trial. Findings from the data collection have been reported in separate manuscripts. MS 2 (submitted) focuses on the main outcome of the randomized controlled trial, that is, the overall change from pre- to post- eating disorder symptoms among the trauma and non-trauma patients in each treatment condition. This study, MS 3, focuses on weekly changes in eating disorder symptoms and self-compassion during therapy.