Abstract

Objective

When therapists’ proposals are too demanding exceeding clients’ readiness to move into change, clients may resist advancing. We aimed to understand how a therapist behaved immediately after the client resisted advancing into change within Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy.

Methods

We analyzed a recovered and an unrecovered case, both with Major Depression, and followed by the same therapist. Through the Therapeutic Collaboration Coding System, we analyzed 407 exchanges of interest.

Results

In both cases, clients resisted more in advancing at intermediate sessions, mainly by the therapist’s challenges to raise insight and debate cognitive beliefs in the recovered case, and to seek experiential meanings in the unrecovered case. Immediately after clients resisted advancing, the therapist tended to insist on challenging them in the same direction. In the recovered case, the therapist did so continually throughout the therapy, sometimes balancing between insisting or stepping back. In the unrecovered case, the therapist insisted on challenging, but mostly at the final session. Occasionally, the therapist insisted on challenging, and clients resisted over consecutive exchanges.

Conclusion:

Our results reinforce that to enact progress and change clients need to be pushed into change, however it requires therapists’ skillful assessment of clients’ tolerance to move in time.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: (1) This study employs an intensive observational coding of the unfolding interaction between the therapist and client, conducted in a session-level, moment-to-moment and across time. (2) The study results reinforce the theoretical proposition of pushing clients to move further into a challenging zone to enact progress and promote change, requiring from therapists a skillful assessment of clients’ readiness to move in time.

Building knowledge of how therapists can address challenging interpersonal moments has much practical value as it may guide them to better clinical practices. Ribeiro et al. (Citation2013) developed a transtheoretical model—the Therapeutic Collaboration Model (TCM)—to study how therapists foster clients’ gradual movement into change. According to the model, when therapists’ proposals exceed clients’ readiness to change or exceed their Therapeutic Zone of Proximal Development (TZPD), clients feel threatened and experience that movement as too risky to their sense of self. In turn, clients avoid or reject therapists’ proposals and resist moving. This kind of clients resistance is understood by constructivist approaches to psychotherapy as self-protective and a way of maintaining self-coherence, even if it is dysfunctional (e.g., Feixas et al., Citation2014; Kelly, Citation1955). In a broader field, the need and motivation to maintain self-coherence have long been postulated by social theorists. In the Self-Verification Theory, Swann (Citation1983) argued that people’s self-views provide them with a sense of control, prediction, and familiarity. When self-continuity and integrity are called into question, people often engage themselves in cognitive, behavioral, and relational security operations to preserve their favorable self-views and to self-verify others’ positivity about themselves (Sullivan, Citation1953). Psychotherapy is a social context where applications of the self-verification theory help to understand clients’ resistance to proposals that, stemming from their familiar perspectives, challenge their comfort and predictability, and promote self-discrepancy.

Moreover, this literature offers some insight into how therapists’ flexible behavior can facilitate a balance between clients’ experiences of being verified and change in the therapeutic relationship context (see Pinel & Constantino, Citation2003, for a revision). According to Ribeiro et al. (Citation2013), therapists do not have prior knowledge about clients’ TZPD limits. Following an implicit principle of push where it moves, therapists can adjust their interventions to help clients to progress along their TZPD. Although exceeding clients’ TZPD is an inevitable occurrence in therapy, it can, if handled well, pose a relational change opportunity or, if handled poorly, contribute to stuckness or deterioration. Driven by the TCM (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013), in this study, we aimed to understand how the therapist behaved immediately after exceeding the client’s TZPD within Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

Therapeutic Collaboration Model

The TCM posits that change occurs toward a developmental continuum where clients move from an actual development level into a potential one in collaboration with their therapists (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013). Or, clients move from what brings them into therapy (usually maladaptive perspectives) into what they intend to achieve (more functional and adaptive perspectives). The distance between levels is conceptualized as clients’ TZPD, reflecting therapists’ and clients’ joint activity in a developmental sequence from which clients progress (Leiman & Stiles, Citation2001). Theoretically, clients gradually move from an actual to a potential level through collaborative dyadic exchanges (e.g., the therapist invites the client to adopt a new action and she/he agrees on doing it). Yet, to achieve the desired change clients must be challenged to move into their potential levels. Therapists’ interventions pushing clients to move into their potential levels exceeding their TZPD are our main focus. These therapeutic exchanges are operationalized as therapists’ challenging interventions and clients’ invalidation responses by an experience of intolerable risk—Challenging-Intolerable Risk (C-IR; Ribeiro et al., Citation2013). An experience of intolerable risk indicates clients’ developmental inability to move into their potential levels by a feeling of threat in their usual sense of self. In CBT, it may happen when therapists try to debate clients’ beliefs. For example, a CBT therapist may ask Let’s look at the evidence! How do you know no one is going to be there for you? As clients do not get used to questioning their cognitions, they may resist by defending their usual perspectives. For example, a depressed client may respond to that question because I’m a failure and useless! To Ribeiro et al. (Citation2013), C-IR exchanges represent an interruption of dyads’ collaborative work being defined as Therapeutic Collaboration (TC) breaks.

Collaboration between therapists and clients is defined as dyads’ joint effort to work within clients’ TZPD (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013). Working within clients’ TZPD indicates their ability to accept the therapists’ proposals through validation responses. These responses occur when therapists intend to work at clients’ actual levels to better understand their problematic perspectives by supporting problem interventions (e.g., questioning), or the emerging changes by supporting innovation interventions (e.g., reflecting). Or, when therapists intend to work at clients’ potential levels proposing to them alternative perspectives by challenging interventions (e.g., inviting them to explore hypothetical scenarios). Validation responses are delivered by clients when they feel safe to work at their actual levels (e.g., giving more information about their problematic or emergent novel perspectives), or tolerate being pushed into their potential levels (e.g., elaborating on the new perspectives proposed by the therapist).

By contrast, when clients reject therapists’ proposals through invalidation responses, TC breaks emerge since the therapeutic work is placed outside clients’ TZPD (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013). Invalidation responses are delivered by clients when they feel disinterest in the topic initiated, placing the work below their TZPD (e.g., lack of involvement in the response). Or, when they feel threatened with being pushed into change (intolerable risk), placing the work above their TZPD (e.g., shifting the topic). TC breaks are re-established when dyads return to work within clients’ TZPD, or when clients validate the therapists’ proposals. Accordingly, if their responses remain of invalidation, TC breaks are not re-established and sustained. Clients can also oscillate between validation and invalidation within the same response, or between accepting and rejecting therapists’ proposals. As clients are ambivalent about moving into their potential levels or staying at their actual levels the work is placed at their TZPD limits. In turn, TC breaks (non)reestablishment stays undefined (for full details see Ribeiro et al., Citation2013).

Intensive case studies conducted in diverse therapeutic approaches have been reinforcing that therapeutic work is productive when it is performed within clients’ TZPD. It was found that in recovered cases therapists privileged work within clients’ TZPD, and their collaborative interventions tended to increase across time (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2019; Ribeiro, A. P. et al. Citation2014). Nonetheless, therapists’ work outside clients’ TZPD, especially exceeding it, was common, yet more frequent in unrecovered and dropout cases than in recovered ones (Ferreira et al., Citation2015; Pinto et al., Citation2018). Moreover, dyads’ non-collaborative work tended to decrease across time in recovered cases and to increase across time in unrecovered and dropout cases. As critical points for exploration, we intended to understand how the therapist behaved immediately after the client expressed developmental inability and resisted advancing into change within CBT.

Resistance within Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy

The concept of TC breaks addressed in this study is in line with the concept of resistance as an interpersonal phenomenon in psychotherapy. There are related constructs of resistance in the field. The majority of the studies concern to alliance ruptures defined as minor or major tensions in therapists’ and clients’ ability to negotiate the alliance components (Safran & Muran, Citation2000). Other studies employ the TZPD concept to analyze clients’ setbacks, defined as reversals in the therapeutic progress since after therapists’ interventions clients shift back into a less-advanced stage of assimilation (Caro Gabalda et al., Citation2016, Caro Gabalda & Stiles, Citation2018).

Clients’ resistance has been identified as a key process marker with consequences to both the therapeutic alliance and treatment outcomes (Westra & Norouzian, Citation2018). In CBT, it can be raised by therapists’ misconceptions regarding clients’ functioning, instead of assuming a posture of discovery or facilitation of cognitive reappraisal (Leahy, Citation2001). In turn, clients display some level of resistance such as homework non-compliance, disengagement with the therapy, ignoring, disagreeing, or arguing with therapists (see Westra & Nourozian, Citation2018). Previous studies show that when therapists rigidly adhere to CBT rationale or dogmatically insist to apply its techniques regardless of clients’ concerns strains in the therapeutic relationship emerge and are sustained (Aspland et al., Citation2008; Beutler et al., Citation2011; Westra et al., Citation2011). Therapists’ directive posture has been found to impact negatively clients’ improvement, yet attending to strains by building an engaging and collaborative environment enacts clients’ gains (Westra et al., Citation2016). For example, the correlation between repaired alliance ruptures and good outcomes, and unrepaired ones and poor outcomes in CBT is well established (Eubanks et al., Citation2018; Flückinger et al., Citation2018).

Kazantzis et al. (Citation2017) argued that therapists’ ability to address strains in the therapeutic relationship before engaging on how to proceed is a skill for a collaborative resolution process. In the first study conducted in CBT, Aspland et al. (Citation2008) found that alliance ruptures were repaired when the therapist took the responsibility for them validating and realigning with clients’ points of view. Castonguay et al. (Citation2004, Citation2010) highlighted the role played by humanistic and interpersonal listening skills such as feeling empathy, inquiry, and disarming techniques to better address ruptures. Integrating those skills into standard Cognitive Therapy for depression, Constantino et al. (Citation2008) found support for their efficacy in ruptures resolution and their causal role in enacting the application of the cognitive rationale and techniques by therapists. Anderson et al. (Citation2009, Citation2016, Citation2020), applying the Facilitative Interpersonal Skills principles, found that therapists who reacted to ruptures non-defensively and with immediacy demonstrated appropriate responsiveness, and their clients achieved better outcomes. According to Kramer and Stiles (Citation2015), therapists with appropriate responsiveness are those who are influenced by the emergent context. In face of difficult relational moments, they adjust their interventions consistently with their clients, theoretical and personal principles (Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017). Recently, Caro Gabalda and Stiles (Citation2022) observed how the therapist acted after the client had TZPD setbacks in Linguistic Therapy of Evaluation. These setbacks occurred when the therapist exceeded the client’s TZPD. Authors found that the therapist nevertheless gave up on the avoided strand by the client, being appropriate to the therapeutic approach and responsive to the client's clinical needs to achieve change. In Emotion-Focused Therapy, Ribeiro et al. (Citation2016) verified that the therapist’s interventions exceeding the client’s TZPD at intermediate sessions were associated with the client's progress in stages of assimilation. The mentioned intensive case studies were conducted in successful cases, and their results indicate that even if exceeding clients’ TZPD briefly interrupts their progress, it may enact their progress as well. Widespread in the empirical literature, high or poor adherence to the CBT agenda and its role in clients’ progression ultimately depends on a variety of contextual circumstances, such as the dyad’s interpersonal dynamic (Coyne et al., Citation2018), the client’s diagnosis (Hauke et al., Citation2014; Schwartz et al., Citation2022; Strunk et al., Citation2010), and their needs for self-enhancement and positive interactions (see Pinel & Constantino, Citation2003, for a revision), and the time itself in therapy (Westra & Norouzian, Citation2018).

Observing process markers in the unfolding interaction between therapists and clients has much importance since it is a source of information about clients’ readiness for change (Westra & Norouzian, Citation2018). According to Ribeiro et al. (Citation2013), TC breaks are an interpersonal phenomenon imbued in clients’ TZPD range and therapists’ responsiveness to their developmental levels. When TC breaks of C-IR emerge, clients are signalizing therapists that their invitations to move into change are too demanding for what they can tolerate at that particular moment. In this study, we intended to extend the depth observations into CBT contributing to the knowledge of how therapists can address difficult interpersonal moments within the emerging context of therapeutic collaboration across time. We aimed to understand how the therapist demonstrates appropriate responsiveness to the client's readiness for change in two contrasting cases. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comparative case study conducted moment-to-moment and across time in CBT.

Study Purpose and Design

We aimed to understand how the therapist effectively adjusts her interventions immediately after C-IR exchanges in two contrasting cases within CBT. According to the TCM (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013), therapists’ interventions are effective if they promote moving from a work performed outside clients’ TZPD to within it. We employed an in-session and moment-to-moment analytic lens to address the following questions: (1) How does the therapist perform immediately after C-IR exchanges? (2) Are, or are not C-IR exchanges immediately re-established? (3) If not, how long are C-IR exchanges extended?

We followed a single-case methodology since it offered us the opportunity for a fine-grounded analysis of how the phenomenon of interest took place in its context. As we intended to reinforce the theoretical model that guides us, namely the theoretical proposition of challenging clients to move further into a potential zone to enact progress and promote change (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013), our study was drawn within a theory-building approach (Stiles, Citation2009). Our study is framed by (a) an interpretative lens, in an attempt to reinforce the theoretical proposition aforementioned by comparing it with the observations made; (b) a descriptive design, since our interest was to observe how the phenomenon of interest occurred and do not search for causalities; and (c) an interactive research format, since our findings led us to bring up new research questions.

Method

Participants

Clients. Both cases were diagnosed with Major Depression according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria (APA, Citation2000). Kate is a Brazilian female who had 29 years of age and was a Ph.D. student at the moment of the treatment. She asked for psychological help due to her intimate relationship breakup, which was setting up emotional and cognitive disruption since she and her ex-boyfriend shared the same working context. Her life events were arousing sadness, feelings of emptiness, a lack of hope in the future, and willingness to engage herself in used joyful activities. Kate’s sadness was matched with anger since her ability to stay on track and work was compromised, pulling a trigger of a lack of life-affirming ability arousing anxiety.

Annie is a Portuguese female who had 32 years old of age, was working as a financial manager in a private company and running her own at the moment of treatment. She asked for psychological help due to emotional and cognitive disruption triggered by the inability to balance her personal and professional lives. She had a lack of ability to set up boundaries in the working context and was struggling with the acceptance of care displayed by a significant other within the same context. Her life circumstances were arousing sadness and loneliness, impairing her ability for decision-making, and compromising her working environment.

Therapist. The therapist is a Portuguese female with a Ph.D. graduation level and clinical experience running cases with the therapeutic approach and the diagnosis, she had 49 years of age and 22 of clinical practice at the moment of treatment.

Treatment. Both cases were conducted weekly throughout 16 sessions. The treatment followed CBT guidelines according to clients’ emerging needs: (a) psychoeducation; (b) behavioral activation; (c) identification of automatics thoughts and associated emotions; (d) identification of the underlying core beliefs; (e) cognitive techniques to debate beliefs; and (f) coping strategies for relapse prevention (Leahy et al., Citation2012).

Researchers. All researchers have clinical experience in CBT, training, and practice with the Therapeutic Collaboration Coding System (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013). The first and second authors are Ph.D. students, they were the independent coders of the cases and were unaware of their outcome status. The third author has a Ph.D. graduation level, audited, and helped to solve the judges’ disagreements by negotiating with them. The fourth author has a Ph.D. graduation level and supervised the entire study as a senior researcher and expert in qualitative research.

Measures

Outcome Questionnaire - 45.2 (OQ-45.2, Lambert et al., Citation1996, Portuguese version by Machado & Fassnacht, Citation2015). The OQ-45.2 allowed us to measure cases outcome based on clients’ total scores to 45 items (ranging from 0 to 180) assessing general clinical symptomatology, interpersonal functioning, and social role performance. The Portuguese version presents good internal consistency, validity, and reliability (Cronbach's alpha between .60 and .92, and Test-retest between .41 and .80). Considering Jacobson and Truax’s (Citation1992) criteria, reliable and clinically significant improvement requires at least 15 points of difference between the OQ-45 total scores from pre to post-treatment, and a clinical cut-off of 62 points.

Kate’s case was considered improved and recovered since she started her treatment with an OQ-45.2 total score of 119, namely 76 in general clinical symptomatology, 29 in interpersonal functioning, and 14 in social role performance. At the end of treatment, her OQ-45.2 total score dropped to 34, with subscales scores of 15, 11, and 8, respectively. Annie’s case was considered improved but unrecovered since she started her treatment with an OQ-45.2 total score of 107, namely 56 in general clinical symptomatology, 31 in interpersonal functioning, and 20 in social role performance. At the end of treatment, her OQ-45.2 total score dropped to 81, with subscales scores of 44, 21, and 16, respectively. Therefore, in contrast with the case of Kate, Annie’s case was above the clinical cut-off of the OQ-45.2 total score.

Therapeutic Collaboration Coding System (TCCS; Ribeiro et al., Citation2013). The TCCS is a transcript-based instrument yielded to observe the therapeutic collaboration evolution at a moment-to-moment level through the therapist and client's adjacent pair of speaking turns. The therapist’s interventions are coded in broadest categories marking where the work is intended to occur by reference to the client’s TZPD: Supporting Problem or Innovation are located at the client’s actual development level; and, Challenging is close to the client’s potential development level. The client’s responses are coded in broadest categories as well, marking in which TZPD positions the work is performed: Validation by an experience of safety or tolerable risk places the work within the client’s TZPD; Invalidation by an experience of disinterest or intolerable risk places the work outside the client’s TZPD; and, Ambivalence by an oscillation between validation and invalidation within the same response places the work at the client’s TZPD limits. The intersection of the therapist and client’s categories yields the observation of 15 therapeutic exchange types: six collaboratives, six non-collaboratives, and three ambivalent. Based on 3,234 utterances, the TCCS initial trial presents good and acceptable reliability with mean Cohens Kappa values of .92 for therapists’ interventions and .93 for clients’ responses (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013). We selectively used the TCCS to code (a) the therapist’s interventions to address the first and third research questions, and (b) the clients’ responses to address the second research question.

Procedure

Selecting cases. Cases belong to the Project COLPsi database, consented to by the Institutional Ethical Committee from University of Minho, and conducted at Psychology Research Centre, School of Psychology. Cases were independently selected by the coordinator of the project taking into account the study purpose and its design. As we followed a single-case approach, we wanted to control variables that may affect the phenomenon occurrence such as the therapist, the treatment outcome, the clinical approach, and the clinical diagnosis and its features. As so, cases were intentionally selected by interest since they (a) were followed by the same senior therapist, (b) were conducted by the same approach, (c) had the same primary diagnosis, plus similar precipitants to it (relational issues in intimate matters and performance commitment in the working context), and (d) had different clinical outcomes as our study aimed to contrast.

Ensuring methodological integrity. Data confidentiality was guaranteed by an informed consent signed by clients and the therapist authorizing the application of their data for research purposes. To ensure clients’ anonymity we used pseudonyms and restricted the data dissemination to their clinical information only. To control coders’ subjectivity in the analytic process, they reflected on and discussed their expectations and familiarity with the TCCS coding procedure in an attempt to minimize their potential bias. Through a consensus practice by the coding pair of judges and an auditory of their disagreements by an expert researcher, we addressed the trustworthiness of our findings. As the clinical cases selected were used in a previous study with different research aims, we analyzed their data with parsimony to only address our research aim and questions.

Coding data. Due to constraints on videotapes, sessions 12 in the recovered case, and 10, 14, and 15 in the unrecovered case were inaccessible. The remaining sessions were verbatim transcripted. Two pairs of judges with training (one master and one doctoral student each) followed the TCCS coding procedure for 30% of the sessions (four per case), making combined use of their videotapes and transcripts. Session by session they (1) carefully read and/or listened to the session, (2) determined the therapist and client’s speaking turns, (3) defined the client’s problematic and innovative perspectives (actual and potential levels), (4) discussed and agreed on the previous steps, and (5) independently coded the therapist and client’s speaking turns accordingly. The judging pairs achieved a satisfactory average percentage of agreement either for the therapist’s interventions (86.4% in the recovered case and 80.7% in the unrecovered one) and for the client’s responses (85.5% in the recovered case and 86.5% in the unrecovered one). The remaining sessions were coded independently by the doctoral students who had been paired. Although we describe below clients’ actual and potential levels in a broad sense, their specifications were formulated session-by-session. Based on the idea that clients’ TZPD is like a developmental continuum moving according to clients’ readiness to progress, TC breaks of C-IR were contextualized on clients’ specific problematic and emergent innovative perspectives within each of the sessions.

Defining Kate’s Therapeutic Zone of Proximal Development. Through a developmental trajectory characterized by high-performance demands and relational ruptures, Kate showed up in the therapy with rigid core beliefs regarding (a) herself (I need to be the best otherwise I am a failure, I need to be strong otherwise I will not succeed, I need to control my life otherwise I will be deceived), (b) others (as relationships are short-time lived I cannot trust on others), and (c) the world (as successful people are strong I cannot show my vulnerabilities, as happy people have a spouse I need to be in a relationship). This dysfunctional perspective represented Kate’s actual level. Her potential level was defined as (a) accepting her intimate breakup, (b) allowing herself to experience sadness and anger to relieve and signify her grief, (c) increasing her working ability and engagement on used pleasant activities, (d) accepting significant others as differentiated from her to promote trust and sharing, and (e) focusing on the present moment to deal with uncertainty in intimate matters.

Defining Annie’s Therapeutic Zone of Proximal Development. Through a developmental story characterized by high expectations as a daughter, parentification, and a lack of care, Annie showed up in the therapy with rigid core beliefs regarding (a) herself (I need to be perfect otherwise I am weak, I need to match others expectations otherwise I am worthless, I need to work hard otherwise I am lazy), (b) others (as others expect perfection I need to check up on everything, as others do not care I cannot trust), and (c) the world (value people are strong). Annie’s actual level was represented by this dysfunctional perspective. Her potential level was defined as (a) increasing her ability for decision-making to set up boundaries in the working context, (b) redefining her priority setting on work to be engaged in self-care, (c) allowing herself to accept care displayed by others to promote trust and proximity, and (d) redefining the relationship nature with the significant other to decrease the conflicting environment in the working context.

Analyzing data. Based on the TCCS coding, we tracked the occurrence of TC breaks of C-IR in each of the sessions extracting 407 exchanges in total. Afterward, we observed which therapist’s interventions and clients’ responses were coded immediately after C-IR exchanges. Finally, we performed descriptive analysis through percentages to answer our questions and presented the results descriptively. As in a previous study conducted by Ribeiro et al. (Citation2016), we considered that Kate and Annie’s therapeutic processes were composed of initial sessions (1–4), intermediate ones (8–12), and final sessions (13–16).

Results

In both cases, C-IR exchanges occurred around 10%. Overall, they were progressively increasing being higher from session 8 forward in both cases. In the recovered case, after session 10, they were progressively decreasing until the treatment ended. In the unrecovered case, they decreased at session 12 but increased again at sessions 13 and 16. Looking deeper into the content of the sessions with the highest proportion of C-IR exchanges, we noted that in the recovered case they emerged mostly from the therapist’s attempts to raise insight on Kate regarding her functioning, as we can follow in this illustration at session 10.

Tr: It seems that what is feeding the cycle you’re living in is your anger … but this is a small piece of what’s happening … deep down, the most difficult is the sadness of losing someone you loved, of being deceived … it’s like the anger you’re feeling is tying up your sadness cause all of this is calling into question your values. (Challenging intervention by interpreting)

Cl: I’m not sad because of this … it’s because of what I’m dealing with. (Invalidation response by disagreeing with the therapist's previous intervention)

In the unrecovered case, C-IR exchanges emerged mostly from the therapist’s efforts to re-focus Annie on experiential meanings, as we can follow in this illustration at session 9.

Tr: At that party you made your presence noted and he (her significant other) was dull! What do you think happened there? Why was it so important for you to be noted that night? (Challenging intervention by inviting to change the level of analysis)

Cl: I don’t know! Then I called him but he said he was feeling tired and didn’t want to stay there anymore … wherever. (Invalidation response by disconnecting from the topic)

How does the Therapist Perform Immediately after Challenging-Intolerable Risk Exchanges?

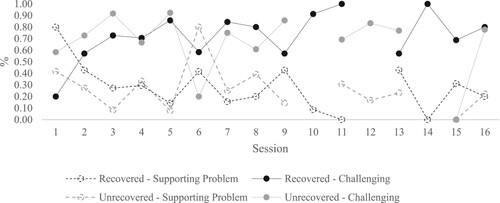

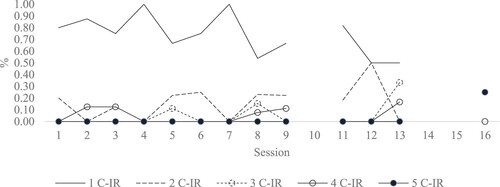

In both cases, most of the time the therapist continued challenging clients to move into their potential levels, compared to working at their actual levels through supporting problem (around 70% and 30%, respectively). The therapist insisted on challenging clients since their therapeutic processes began, only stepping back to their actual levels by supporting problem in a few sessions (see ). In the recovered case, the therapist balanced more between challenging and supporting problem compared to the unrecovered case.

Are, or are not Challenging-Intolerable Risk Exchanges Immediately Re-established?

In both cases, clients’ responses to the therapist’s supporting problem interventions were of validation. Thus, when immediately after C-IR exchanges the therapist stepped back to their actual levels TC breaks were re-established. For example, in the recovered case, immediately after Kate disagreed with the therapist's interpretation regarding the role played by her sadness illustrated above, the therapist stepped back to better understand Kate’s point of view. In turn, she explained it, as we can follow.

Tr: Which is it? Can you tell me? (Supporting Problem intervention by questioning)

Cl: I’m sad cause I see that I hit the bottom! (Validation response by giving more information).

In the unrecovered, immediately after Annie disconnected from the topic not allowing the therapist to seek for the implicit meaning of her behavior illustrated above, the therapist stepped back to better understand her experience. In turn, Annie followed the therapist’s movement, as we can follow.

Tr: How was it for you seeing him with another woman? (Supporting Problem intervention by questioning)

Cl: Still difficult … I’m trying to not think about it that much cause everybody tells me that I need to accept it … we talked about it and I only gave him my opinion. (Validation response by giving more information)

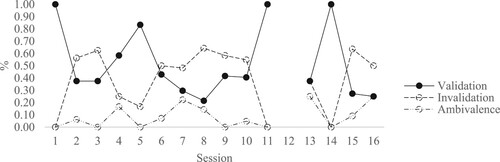

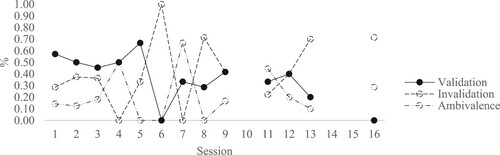

On the other hand, when the therapist insisted on challenging clients to move into their potential levels their responses were different. In the recovered case, Kate’s responses were more of invalidation than validation (around 50% and 40%, respectively). Thus, TC breaks were most often non re-established immediately. In the unrecovered case, Annie’s validation and invalidation responses were approximate (around 40% each). Thus, TC breaks were equally (non)re-established immediately. Moreover, Annie's ambivalent responses to the therapist’s challenging interventions were higher compared to Kate's (around 20% and 10%, respectively). Thus, TC breaks (non)reestablishment stayed more undefined in the unrecovered case. As some of the clients’ responses to the therapist’s challenging interventions were of invalidation, TC breaks were consequently extended, at least to the coming exchange. Therefore, we only focused on these exchanges to observe their distribution within sessions.

As we can follow in , until session 5, Kate was either validating or invalidating more the therapist’s challenging interventions, as well as from session 13 forward. In these sessions, TC breaks were immediately re-established or extended. From sessions 6 to 10, Kate started to invalidate more being TC breaks extended more continuously. Looking deeper into the content of these intermediate sessions, we noted that C-IR exchanges emerged and were extended mostly by the therapist’s attempts to debate Kate’s cognitive beliefs. Here is an example at session 7.

Figure 2. Client’s responses to the therapist’s challenging interventions immediately after Challenging-Intolerable Risk exchanges in the recovered case.

Note: Session 12 = missing data.

Tr: Noticing that people around you are talking with Peter (her ex-boyfriend) is seen by you as they don’t care about you … as far as I understood, you would like Mary (one of her friends) share with you more or tell you about what Peter is feeling confused by. (Supporting Problem intervention by reflecting)

Cl: Yes, yes. (Validation response by confirming)

Tr: Okay. I was wondering if she knows indeed something or if she only knows that he’s feeling confused? (Challenging intervention by confronting)

Cl: She knows something else, for sure! They were talking with each other for more than one hour! (Invalidation response by defending her usual perspective)

Tr: Hm_hm. And how do you know it? How do you know they were talking about what happened between the two of you? (Challenging intervention by confronting)

Cl: Cause we were at lunchtime, and they missed the institute meeting, they stayed lunching and were alone at the table … Mary only show up after one hour! Common, what else could be?! (Invalidation response by defending her usual perspective)

In the unrecovered case (see ), until session 5 Annie validated more the therapist’s challenging interventions, thus TC breaks were most often immediately re-established (we can follow below an illustration at session 5). From session 6 forward, Annie increased abruptly her invalidating responses and kept doing it more until her process ended. From there on, C-IR exchanges started to be extended. Moreover, since her process began, Annie was displaying ambivalence to move into her potential level, increasing it from session 4 forward.

Figure 3. Client’s responses to the therapist’s challenging interventions immediately after Challenging-Intolerable Risk exchanges in the unrecovered case.

Note: Sessions 10, 14, and 15 = missing data.

Tr: You took the Saturday to visit your friends, and you enjoyed it but then you felt guilty. (Supporting Problem intervention by reflecting)

Cl: Exactly! (Validation response by confirming)

Tr: Hm_hum. Guilty for taking time to yourself instead of working … if you try to put yourself outside this feeling, what you would like to say to that guilty? (Challenging intervention by inviting to change the level of analysis)

Cl: You know, as I’m with a lot of responsibilities all minutes count for me … to do some kinds of stuff I can’t do others, I need to choose. (Invalidation response by defending her usual perspective)

Tr: You’re saying that even if you want to take time to yourself, doing it turns into something uncomfortable cause, in a way, it calls for a functioning that you rigidified, oriented to the work, with many duties … it seems that taking that choice is uncomfortable now because it’s something new to you. (Challenging intervention by interpreting)

Cl: Exactly! It’s mainly because I’m not used to doing it … That’s why I always ended up feeling that sorrow and guilt. (Validation response by giving information)

How Long are Challenging-Intolerable Risk Exchanges Extended?

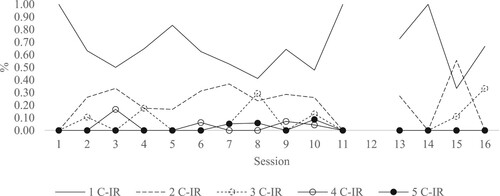

Most of the time, C-IR exchanges occurred only one time in both cases (around 60% in the recovered case and 70% in the unrecovered one). Thus, immediately after a C-IR exchange dyads performed differently. The remaining proportion was distributed by sequences of consecutive C-IR exchanges in a maximum of five in both cases. We can follow their distributions within sessions in and .

Figure 4. Sequences of consecutive Challenging-Intolerable Risk exchanges within sessions in the recovered case.

Note: Session 12 = missing data; C-IR: Challenging-Intolerable Risk.

Figure 5. Sequences of consecutive Challenging-Intolerable Risk exchanges within sessions in the unrecovered case.

Note: Sessions 10, 14, and 15 = missing data; C-IR: Challenging-Intolerable Risk.

In the recovered case (see ), C-IR exchanges occurred only one time across Kate’s therapeutic process as well as sequences of two consecutive C-IR exchanges, yet with a lowest proportion. Sequences of three consecutive C-IR exchanges only occurred in a few sessions. Thus, TC breaks were occasionally extended to sequences of two and/or three consecutive exchanges. Although residually, bigger sequences occurred more recurrently from sessions 6 to 10. Thus, TC breaks were longer within these sessions.

In the unrecovered case (see ), C-IR exchanges also occurred only one time across Annie’s therapeutic process. Sequences of two and three consecutive C-IR exchanges occurred most often from session 5 forward. Bigger sequences occurred in a few sessions throughout the therapy. TC breaks were longer in session 13, where the dyad extended the work outside Annie’s TZPD over five consecutive exchanges.

Looking deeper into the phenomenon, we went back to our research questions and raised the following one: which therapist’s interventions preceded re-established TC breaks of consecutive C-IR exchanges? In other words, it was the therapist who stepped back into clients’ actual levels, or were the clients who move into their potential levels? As sequences of four and five consecutive C-IR exchanges were residual in both cases, we only focused on the remaining. shows the therapist’s interventions and clients’ validation responses immediately after sequences of consecutive C-IR exchanges according to their extension.

Table I. Percentage of the therapist’s interventions and clients’ validation responses according to the sequence of consecutive Challenging-Intolerable Risk exchanges by case.

In the recovered case, before re-established C-IR exchanges that only occurred one time and sequences of three consecutive exchanges, the therapist insisted on challenging Kate to move into her potential level the most. In contrast, in sequences of two consecutive C-IR exchanges, the therapist stepped back more to Kate’s actual level by supporting problem interventions. Most of the time, Kate ended up moving into her potential level immediately after the therapist insisted on challenging her to move one more time. On the other hand, in the unrecovered case, regardless of the extension of re-established C-IR exchanges, the therapist mostly insisted on challenging Annie to move into her potential level. Annie’s validation responses to the therapist’s challenging interventions were higher in sequences of three consecutive C-IR exchanges. Thus, Annie was able to move into her potential level the most as much as the therapist insisted on challenging her.

Discussion

Our study aimed to understand how the therapist effectively adjusted her interventions immediately after TC breaks in two contrasting cases within CBT. We specifically focused on TC breaks raised by the therapist’s challenging interventions and clients’ invalidation responses by an experience of intolerable risk (C-IR). Our observations are theoretically driven by the TCM (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013), thus we considered the therapist’s interventions as effective when they promoted TC breaks reestablishment. It implies that the dyad moved from a work performed outside the client’s TZPD to within it.

Accordingly to the TCM (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013), to achieve change clients need to be challenged by therapists to move into their potential developmental levels. Yet, if this movement is felt by clients as too risky to their usual sense of self, they shift back into a safety zone interrupting their progress. This assumption has been supported by the results of several studies (Caro Gabalda et al., Citation2016; Caro Gabalda & Stiles, Citation2018, Citation2022; Ribeiro et al., Citation2013, Citation2019; Ribeiro, A. P. et al., Citation2014), but most of all in poor outcome and dropout cases (Ferreira et al., Citation2015; Pinto et al., Citation2018; Ribeiro et al, Citation2016). In our study, in both recovered and unrecovered cases, TC breaks of C-IR did not occur that much. It may be similar among the cases because their treatment outcomes were not entirely contrasting. Although the unrecovered client did not achieve a clinically significant change at the end of treatment, she improved.

We find that TC breaks of C-IR emerged more prominently within intermediate sessions in both cases. In the recovered case, they occurred more when the therapist invited Kate to think about the role played by her emotions on her dysfunctional functioning and tried to debate her cognitive beliefs. In the unrecovered case, they mainly occurred by the therapist’s efforts to re-focus Annie on experiential meanings in an attempt to raise insight regarding her emotional and behavioral dysfunctional functioning. Our results show that it was difficult for both clients to be engaged in discovery work, and support that in face of cognitive reappraisal clients may resist it (Leahy, Citation2001).

Although it would be expected that in face of clients’ difficulties a responsive therapist quickly shifts back to realign with their experiences (Anderson et al., Citation2020; Aspland et al., Citation2008; Ribeiro et al., Citation2013; Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017), in our study we find the opposite. Overall, immediately after both clients signalized that the therapist was exceeding their tolerance levels to move close to the change, the therapist tended to insist on pushing them. Unexpectedly, Kate (recovered client) resisted more in advancing than Annie (unrecovered client). Therefore, the therapist’s insistence on challenging was more effective for TC breaks of C-IR immediate reestablishment in the unrecovered case. Yet, it was only effective in the initial sessions. From session five forward, Annie started to reject and resist moving into change and to display higher levels of ambivalence. Thus, from that moment in Annie’s process on, TC breaks of C-IR were emerging and being sustained or undefined in terms of its (non)re-establishment. These results are not only congruent with the TCM principles (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013), but also with previous studies showing that ambivalent clients commonly limit their engagement in the therapy and its treatment procedure, and their resistance to advance into change impairs their treatment benefits (Ribeiro, A. P. et al., Citation2014; Westra et al., Citation2011; Westra & Norouzian, Citation2018).

We also find that the therapist insisted more on challenging over consecutive exchanges above clients’ tolerance to move into change in the recovered case. The therapist tended to do it across Kate’s therapeutic process, yet more continuously in intermediate sessions. In a matter of fact, at session six the therapist and Kate agreed on focusing on her automatic thoughts and core assumptions from there on. Previous findings suggested that resistance and shifts in the therapeutic relationship are sustained when therapists dogmatically insist on the cognitive rationale and its techniques (Aspland et al., Citation2008; Beutler et al., Citation2011; Westra et al., Citation2011). Although we observed it as well, the therapist's insistence on the cognitive agenda at such a time in Kate’s therapeutic process may have fostered her change in the long run. This result is in line with previous findings where it was observed that therapists pursued their line of action to re-focus clients on the difficult material to help them progress (Ribeiro et al., Citation2016; Caro Gabalda & Stiles, Citation2022). Congruently, Strunk et al. (Citation2010) verified that depressed clients had less symptom improvement in the following sessions when the therapist adhered less to the CBT agenda. Looking deeper at Kate’s case, we conclude that she may have benefited from the therapist’s consecutive invitations in advance due to her intense desire to back on track with her life. Kate often verbalized in therapy a sense of being “stuck on her own life” and an urgency of “moving on”. Although Kate signalized discomfort, the therapist's directedness and adherence to the cognitive agenda may have fostered her TZPD expansion over time and, in turn, promoted her tolerance of being pushed to advance into change. In fact, she needed less time to actually move compared to Annie.

Likewise, looking deeper into Annie’s case, it was noticeable a tendency to avoid or reject the therapist’s invitations to advance perhaps to the fact that most of those invitations concerned to experiential meanings. Annie often showed self-doughs in her competence and value as a person in therapy. As some studies show, people with low self-esteem truly feel threatened with self-discrepant evaluations by a credible person (see Pinel & Constantino, for a revision). Since Annie’s TZPD was more narrow, she may need more balance between working at her actual level and being pushed into her potential level on the therapist's behalf.

Kramer and Stiles (Citation2015) defended that a therapist with appropriate responsiveness does the right thing at the right moment, which can be different for each client, time, and treatment delivered. Thus, what seems beneficial for clients with certain needs and characteristics may not fit other clients. For example, Huake et al. (Citation2014) found that for clients with panic disorder therapists’ adherence was both beneficial and detrimental to clients’ improvement. Also, in a recent study with panic disorders, Schwartz et al. (Citation2022) verified that therapists’ rigid adherence contributed to clients hostile resistance while acting with flexibility minimized the possibility of further hostility and poor treatment responses. Stepping back with directive CBT intentions in favor of supportive and motivational interviewing techniques have been proven to work in resistant and ambivalent clients with generalized anxiety (Coyne et al., Citation2018).

Limitations and Implications

We are aware our findings are limited to the sessions available for observation, especially in the unrecovered case. Not being able to observe its final sessions does not allow us a full understanding of the case. Our conclusions are limited to the TC break type analyzed. According to the TCM (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013), TC breaks can also emerge by clients disinterest in the topic initiated by therapists. Under these circumstances, a therapist may behave differently. From our observations, we conclude that the therapist may have a personal style of insisting on challenging, perhaps to the fact she is a senior therapist. Therapists’ effectiveness in addressing TC breaks according to their clinical experience is unknown yet. Moreover, we may have found a similar pattern on the therapist's behalf because the cases were not entirely contrasting. Perhaps, in a deteriorated case or with less improvement the phenomenon occurs differently. Could it be the case that in such a context a therapist steps back more to the client’s actual level spending less time working on key aspects for change? Or, the therapist pushes even more continually the client above what he/she can tolerate increasing his/her discomfort in the therapy?

Driven by a case study approach, we do believe our observations shed light on the field, contributing to the knowledge of how therapists can be responsive to clients’ readiness to move into change. Firstly, our results support previous findings regarding the efficacy of stepping back to realign with clients’ points of view (Anderson et al., Citation2020; Aspland et al., Citation2008; Ribeiro et al., Citation2013). We find that when the therapist validated and supported clients’ intolerable risk experiences, TC breaks of C-IR were immediately re-established in both cases. To display a minimal level of validation, therapists may simply follow their clients through active listening skills. Secondly, our results reinforce the theoretical proposition of pushing clients to move into a challenging zone to enact progress and promote change (Ribeiro et al., Citation2013). However, it requires from therapists a skillfully assessment of clients’ tolerance to move in time. To promote change, therapists need to be aware that clients’ assumptions are connected to their sense of self, moment-to-moment in the therapy. Thus, to challenge clients’ dysfunctional perspectives and create an opportunity to revise them timing matters. As Westra and Norouzian (Citation2018) pointed out, to roll with resistance in CBT timing matters, perhaps differentiating therapists with good and poor outcome cases.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted at the Psychology Research Centre (PSI/01662), School of Psychology, University of Minho. This work was partially supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through the Portuguese State Budget (Ref.: UIDB/PSI/01662/2020).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). CLIMEPSI EDITORES.

- Anderson, T., Crowley, M. J., Himawan, L., Holmberg, J., & Uhlin, B. (2016). Therapist facilitative interpersonal skills and training status: A randomized clinical trial on alliance and outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 26(5), 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1049671

- Anderson, T., Finkelstein, J. D., & Horvath, S. A. (2020). The facilitative interpersonal skills method: Difficult psychotherapy moments and appropriate therapist responsiveness. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 20(3), 463–469. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12302

- Anderson, T., Ogles, B. M., Patterson, C. L., Lambert, M. J., & Vermeersch, D. A. (2009). Therapist effects: Facilitative interpersonal skills as a predictor of therapist success. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(7), 755–768. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20583

- Aspland, H., Llewelyn, S., Hardy, G. E., Barkham, M., & Stiles, W. B. (2008). Alliance ruptures and rupture resolution in cognitive–behavior therapy: A preliminary task analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 18(6), 699–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300802291463

- Beutler, L. E., Harwood, T. M., Michelson, A., Song, X., & Holman, J. (2011). Resistance/reactance level. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20753

- Caro Gabalda, I., & Stiles, W. B. (2018). Assimilation setbacks as switching strands: A theoretical and methodological conceptualization. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 48(4), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-018-9385-z

- Caro Gabalda, I., Stiles, W. B., & Pérez Ruiz, S. (2016). Therapist activities preceding setbacks in the assimilation process. Psychotherapy Research, 26(6), 653–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1104422

- Caro Gabalda, I., & Stiles, W. B. (2022). Therapeutic activities after assimilation setbacks in the case of Alicia. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2021.2023467

- Castonguay, L. G., Boswell, J. F., Constantino, M. J., Goldfried, M. R., & Hill, C. E. (2010). Training implications of harmful effects of psychological treatments. American Psychologist, 65(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017330

- Castonguay, L. G., Schut, A. J., Aikins, D. E., Constantino, M. J., Laurenceau, J.-P., Bologh, L., & Burns, D. D. (2004). Integrative cognitive therapy for depression: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 14(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/1053-0479.14.1.4

- Constantino, M. J., Marnell, M., Haile, A. J., Kanther-Sista, S. N., Wolman, K., Zappert, L., & Arnow, B. A. (2008). Integrative cognitive therapy for depression: A randomized pilot comparison. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 45(2), 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.122

- Coyne, E. A., Constantino, M. J., Laws, H. B., Westra, H. A., & Antony, M. M. (2018). Patient–therapist convergence in alliance ratings as a predictor of outcome in psychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 28(6), 969–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1303209

- Eubanks, C. F., Muran, J. C., & Safran, J. D. (2018). Alliance rupture repair: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 508–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000185

- Feixas, G., Montesano, A., Erazo-Caicedo, M. I., Compañ, V., & Pucurull, O. (2014). Implicative dilemmas and symptom severity in depression: A preliminary and content analysis study. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 27(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2014.850369

- Ferreira, Â., Ribeiro, E., Pinto, D., Pereira, C., & Pinheiro, A. (2015). Colaboração terapêutica: Estudo comparativo de um caso finalizado e de um caso de desistência. Análise Psicológica Psicológica, 33(2), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.938

- Flückinger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., & Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000172

- Hauke, C., Gloster, A. T., Gerlach, A. L., Richter, J., Kircher, T., Fehm, L., Stoy, M., Lang, T., Klotsche, J., Einsle, F., Deckert, J., & Wittchen, H. U. (2014). Standardized treatment manuals: Does adherence matter? Sensoria: A Journal of Mind, Brain & Culture, 10(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.7790/sa.v0i0.362

- Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1992). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Methodological issues & strategies in clinical research (pp. 631–648). American Psychological Association.

- Kazantzis, N., Dattilio, F. M., & Dobson, K. S. (2017). The therapeutic relationship in cognitive-behavioral therapy. A Clinician's Guide.

- Kelly, G. (1955). Personal construct psychology. Norton.

- Kramer, U., & Stiles, W. B. (2015). The responsiveness problem in psychotherapy: A review of proposed solutions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 22(3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12107

- Lambert, M., Burlingame, G. M., Umphress, V., Hansen, N. B., Vermeersch, D., Clouse, G. C., & Yanchar, S. C. (1996). Reliability and Validity of the Outcome Questionnaire. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 3(4), 249–258.

- Leahy, R. L. (2001). Overcoming resistance in cognitive therapy.

- Leahy, R. L., Holland, S. J. F., & McGinn, L. K. (2012). Treatment plans and interventions for evidence-based psychotherapy. Treatment plans and interventions for depression and anxiety disorders. Guilford Press.

- Leiman, M., & Stiles, W. B. (2001). Dialogical sequence analysis and the zone of proximal development as conceptual enhancements to the assimilation model: The case of Jan revisited. Psychotherapy Research, 11(3), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/713663986

- Machado, P. P. P., & Fassnacht, D. (2015). The Portuguese version of the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45): Normative data, reliability, and clinical significance cut-offs scores. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 88(4), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12048

- Pinel, E. C., & Constantino, M. J. (2003). Putting self psychology to good use: When social and clinical psychologists unite. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 13(1), 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/1053-0479.13.1.9

- Pinto, D., Sousa, I., Pinheiro, A., Freitas, A. C., & Ribeiro, E. (2018). The therapeutic collaboration in dropout cases of narrative therapy: An exploratory study. Revista de Psicoterapia, 29(110), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.33898/rdp.v29i110.209

- Ribeiro, A. P., Ribeiro, E., Loura, J., Gonçalves, M. M., Stiles, W. B., Horvath, A. O., & Sousa, I. (2014). Therapeutic collaboration and resistance: Describing the nature and quality of the therapeutic relationship within ambivalence events using the therapeutic collaboration coding system. Psychotherapy Research, 24(3), 346–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.856042

- Ribeiro, E., Cunha, C., Teixeira, A. S., Stiles, W. B., Pires, N., Santos, B., Basto, I., & Salgado, J. (2016). Therapeutic collaboration and the assimilation of problematic experiences in emotion-focused therapy for depression: Comparison of two cases. Psychotherapy Research, 26(6), 665–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1208853

- Ribeiro, E., Ribeiro, A. P., Gonçalves, M. M., Horvath, A. O., & Stiles, W. B. (2013). How collaboration in therapy becomes therapeutic: The therapeutic collaboration coding system. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 86(3), 294–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.2012.02066.x

- Ribeiro, E., Silveira, J., Azevedo, A., Senra, J., Ferreira, Â, & Pinto, D. (2019). Therapeutic collaboration: A comparative study of two contrasting cases of constructivist therapy. Revista Argentina de Clinica Psicologica, 28(II), 127. https://doi.org/10.24205/03276716.2019.1104

- Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance: A relational treatment guide. Guilford Press.

- Schwartz, R. A., McCarthy, K. S., Solomonov, N., Chambless, D. L., Milrod, B., & Barber, J. P. (2022). How does hostile resistance interfere with the benefits of cognitive–behavioral therapy for panic disorder? The role of therapist adherence and working alliance. Psychotherapy Research, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2022.2044086

- Stiles, W. B. (2009). Logical operations in theory-building case studies. Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy, 5(3), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.14713/pcsp.v5i3.973

- Stiles, W. B., & Horvath, A. O. (2017). Appropriate responsiveness: A key therapist function. In L. Castonguay & C. E. Hill (Eds.), Therapist effects and therapist effectiveness (pp. 71–84). APA Books.

- Strunk, D. R., Brotman, M. A., & DeRubeis, R. J. (2010). The process of change in cognitive therapy for depression: Predictors of early inter-session symptom gains. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(7), 599–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.011

- Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. Norton.

- Swann, W. B., Jr. (1983). Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the self. In J. Suls & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Social psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 2, pp. 33–66). Erlbaum.

- Westra, H. A., Constantino, M. J., & Antony, M. M. (2016). Integrating motivational interviewing with cognitive-behavioral therapy for severe generalized anxiety disorder: An allegiance-controlled randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(9), 768–782. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000098

- Westra, H. A., Constantino, M. J., & Aviram, A. (2011). The impact of alliance ruptures on client outcome expectations in cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 21(4), 472–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2011.581708

- Westra, H. A., & Norouzian, N. (2018). Using motivational interviewing to manage process markers of ambivalence and resistance in cognitive behavioral therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(2), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-017-9857-6