ABSTRACT

Background: Emotion regulation (ER) refers to the process of modulating an affective experience or response. Objectives: This is a systematic review of the research on therapist methods to facilitate patient ER, including affect-focused, experiential methods that aim to enhance immediate patient emotion regulation, and structured psychoeducation, skills training in ER. Method: A total of 10 studies of immediate and intermediate outcomes of emotion regulation methods were examined. A total of 38 studies were included in the meta-analysis of distal treatment effects on emotion regulation. Results: In eight studies with 84 clients and 33 therapists, we found evidence of positive intermediate outcomes for affect-focused therapist methods and interpretations. A meta-analysis of 26 studies showed that the average effect size of ER methods from pre- to post-treatment was large (g = 0.82). Conclusions: Both affect-focused and structured skill training are associated with distal improvements in emotion regulation. When working with ER in psychotherapy, therapists must consider how patients’ cultural backgrounds inform display rules, as well as what might be considered adaptive or maladaptive. The article concludes with training implications and therapeutic practices based on the research evidence.

Clinical Impact Statement

Enhancing patient emotional regulation capacity is therapeutic for a variety of behavioral disorders.

Therapists may use either affect-oriented methods or structured psychoeducational and skill training methods to work with emotion regulation.

Therapist in-session methods aimed at undoing experiential avoidance, enhancing emotional awareness, promoting a full emotional experience, and teaching strategies to cope with distress may be effective in facilitating in-session emotion regulation.

Emotion dysregulation is considered one of the common core mechanisms of psychopathology (Gratz et al., Citation2015) and is an emerging transdiagnostic focus of psychotherapy for a wide range of behavioral disorders. Frequent methods of enhancing patient emotion regulation across a variety of treatment packages include: (a) undoing avoidance of negative emotions, (b) enhancing emotional awareness, (c) allowing the full experience of feared or avoided emotion, (d) learning effective cognitive reappraisal, and (e) learning behavioral and action strategies to modulate unpleasant emotions (Berking et al., Citation2008; McMain et al., Citation2010).

Psychotherapies that address emotion regulation can be roughly divided into two groups. The first group consists of structured psychoeducation and emotion regulation skills training rooted in the cognitive behavioral tradition. These include the unified protocol (UP; Barlow et al., Citation2017), acceptance-and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes, Citation2004), dialectical-behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan, Citation1993), and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al., Citation2002). The methods developed specifically to address emotion regulation skills include skills training in affect and interpersonal regulation (STAIR; Cloitre et al., Citation2002), acceptance-based behavioral therapy (ABBT; Roemer et al., Citation2008), emotion regulation therapy (ERT; Mennin et al., Citation2015; Renna et al., Citation2017), and affect regulation training (ATR: Berking & Lukas, Citation2015).

The second group of psychotherapies is affect-focused, experiential treatments that aim to facilitate immediate patient ER, most often used in affect-focused therapies. These include emotion-focused therapy (EFT; Greenberg, Citation2021), accelerated experiential dynamic psychotherapy (AEDP; Fosha, Citation2021), affect phobia therapy (McCullough et al., Citation2003), and intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy (ISTDP: Abbass, Citation2015; Frederickson et al., Citation2018). The therapist helps patients tolerate and regulate maladaptive emotions and transform them by facilitating the experience of adaptive emotions (Greenberg, Citation2021), ultimately resulting in decreased emotional arousal and greater calmness and wellbeing (Fosha, Citation2021).

Although these approaches have somewhat different therapeutic foci reflecting respective underlying theories of emotion regulation, they nonetheless address patient emotion regulation as one of the central targets of psychotherapy. In the structured methods, modules address each of the above emotion regulation components and progressively build emotion regulation capacities. In affect-focused methods, therapists try to be responsive to the patient’s immediate emotional experiencing in selecting an optimally facilitative method.

Definitions and Clinical Description

Emotion regulation (ER) refers to the process of modulating one or more aspects of an emotional experience or response (Gross, Citation1998). Regulated emotion keeps the individual within a window of tolerance in which optimal emotional functioning is possible (Greenberg, Citation2021; Siegel, Citation1999). Emotion regulation is considered to be intrinsic to mental health and adaptive psychological functioning.

ER involves both internal and external actions to initiate, increase, maintain, decrease, or transform both positive and negative emotions in response to changing demands of emotion-evoking situations. Although often used to refer to a person’s behaviors undertaken once distressing emotions have occurred, ER also includes emotion generation, which is how emotion occurs (e.g., Campos et al., Citation2004). Thus, therapeutic work is not only about teaching strategies to cope with emotions that have already occurred but about transforming those aversive emotions so that more adaptive emotions are experienced in their place (Greenberg, Citation2021).

There is no singular therapist method directly associated with enhancing patient ER. Therefore, enhancing ER can be defined as a group of therapist methods and responses designed to build and strengthen patient emotion regulation capacity. That can be accomplished through a variety of means: providing relational and dyadic responses, facilitating emotional processing and transformation, and teaching skills for tolerating distressing emotions.

Given that most people seeking psychotherapy have difficulties regulating emotions, facilitating effective ER is a common goal across psychotherapies (Leahy et al., Citation2011). Reviewing the clinical literature on emotion processing and regulation, McMain and associates (2010) detailed eight common principles: (a) engage in an ongoing assessment of patient’s capacity to modulate emotions; (b) develop a compassionate, accepting, and genuine therapeutic relationship; (c) educate patients about emotions and their function; (d) promote awareness and acceptance; (e) help patients reduce problematic avoidance and inhibition of emotions; (f) increase the capacity to adaptively express emotion; (g) increase positive emotional experiences; and (h) facilitate changes in emotional processes by providing opportunities for new experiences.

Structured Approaches

Structured methods frequently address ER skills by means of psychoeducation, skills training, and homework exercises. The outline of each session typically includes specific tasks to be completed with accompanying workbooks that patients use for homework.

The Unified Protocol (UP; Barlow et al., Citation2017; Farchione et al., Citation2021) teaches ER skills in 10–20 sessions of individual treatment. Four modules specifically target ER: (a) psychoeducation about the nature and function of emotions, including a detailed discussion of how the patient’s avoidance of emotion is problematic as it reduces the emotion in the short term but reinforces the cycle of emotions in the long term; (b) teaching patients to observe, name, and let go of their emotions without evaluation; (c) learning cognitive emotion regulation strategies to change misappraisals related to negative emotions; and (d) modifying emotionally driven behaviors, which are a specific set of reactive behaviors associated with emotion to drive a person to withdraw, avoid, and escape with exposure to feared emotions.

In dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan, Citation2015), the enhancement of ER is guided by three basic principles (McMain et al., Citation2001): (a) enhancing the ability to be aware of and accept emotional experience, (b) cultivating the ability to regulate emotions and tolerate distress, and (c) changing negative emotions through new learning experiences with exposure. DBT differentiates distress tolerance skills from ER skills. The goal of distress skills is to accept overwhelming emotions and survive through the crises by distracting themselves with pleasurable and self-soothing activities, but not to effect and change their environment as is the aim of ER skills. Mindfulness skills play a central role in both ER and distress tolerance skill learning. Patients learn to nonjudgmentally observe and describe the present moment through contemplative practice and develop wise mind, which is finding a middle path integrating their reason and emotion (Linehan, Citation2015).

In the first phase of emotion regulation therapy (ERT; Mennin et al., Citation2015; Renna et al., Citation2017), the therapist helps the patient cultivate mindful ER skills to increase awareness of emotional experiences, and act flexibly to the intense emotional experiences. They then teach meta-cognitive regulation skills, such as decentering, reframing, and distancing to create a healthy distance and emotional clarity rather than being reactive and consumed by emotions. The therapist also uses a series of imagery exercises to have the patient vividly remember and experience triggers of their emotional response and facilitate “Do-Overs” in which the patient elaborates and enacts a sequence of more adaptive responses in the session. Patients are also taught breathing and other relaxation techniques. In the second phase, therapists teach patients to adopt a proactive orientation, consciously choosing to exposing themselves to anxiety-provoking, yet rewarding experiences to replace dysregulating patterns. The therapist also uses imaginal exposure and chair dialogue to rehearse taking actions toward their personal values rather than responding reactively through worry and rumination.

Affect-Focused Therapies

ER is enhanced in affect-focused therapies by accessing and facilitating the experience of adaptive emotion whose experience has been previously inaccessible, blocked, or avoided (Greenberg, Citation2021). The therapist’s consistent empathy, warmth, and validation, even in the face of patient’s feeling upset or overwhelmed, is important because it is internalized by the patient and becomes a part of the way the patient subsequently responds to upsetting events. In addition, the moment-to-moment empathic attunement to the patient’s emotional state creates a clear focus on the patient’s here-and-now experiences as well as ongoing assessment of emotional processing. Therapists also help patients pay attention to physical signs of emotions from changes in breathing, muscular tension, and other nonverbal signs, staying with and absorbing/taking in such experiences, and symbolizing or finding words to describe them.

In addition, therapists facilitate the experience of adaptive emotions through various expressive and evocative techniques (Medley, Citation2021). The therapist encourages the patient to stay with the emerging emotional experience, sometimes exaggerating and repeating certain actions or phrases so that these are vividly experienced. Dysregulated emotions are transformed by a new experience of adaptive emotions, which Greenberg (Citation2021) called “changing emotion with emotion.” The experience of adaptive emotions is followed by a reflective process of creating its new meaning. Therapists may also help patients reflect the relational experience of being accompanied by the therapist who bears witness to the transformation (Fosha, Citation2001).

Assessment

Assessing ER Methods

We know of no specific measures of ER methods. Early psychotherapy process researchers identified affect-focused therapist responses using categories of therapist verbal responses (Elliott et al., Citation1987), such as the revised Hill Counselor Verbal Response Modes Category System (Hill, Citation1985, Citation1986). These studies differentiate therapist responses that were facilitative of patient affect such as reflection and minimum encourager from those that were not directly related to facilitation of affect such as provision of information, direct guidance, and advice-giving.

Three rating scales used by trained judges include items that evaluate the extent of affect focus and some aspects of therapist methods for ER. For example, the Psychotherapy Process Q-set (Jones et al., Citation1988) has items such as, “Therapist draws attention to patient’s non-verbal behavior.” The Comparative Psychotherapy Process Scale (Hilsenroth et al., Citation2005) includes items such as, “Therapist encourages patient to experience and express feelings in the session.” The Multitheoretical List of Interventions-30 (Solomonov et al., Citation2019) includes items that identify and label emotions, defenses, conflict splits, moment-to-moment experience, exploring personal meaning, and showing interest in patient’s experience.

Fosha et al. (Citation2018) developed the AEDP 9 + 1 Change Process Scale, a therapist-rated measure of therapeutic methods used in AEDP. Five of the nine items (facilitating access to the bodily-rooted experience and to the felt sense of experience, defense work, experientially processing core affective experience, metatherapeutic processing of transformational experience, promoting integration and processing core state experience) relate to facilitating patient emotional process. One item relates to responding to in-session emotion dysregulation (working with overwhelming and highly distressing emotions and alleviating these emotions within the window of tolerance).

Assessing Outcomes of ER Work

Several observer-rated scales measure in-session behavioral indications of ER. Adequate interrater agreement or reliability have been demonstrated for all of them. The Observer-Measure of Affect Regulation (Watson et al., Citation2011) defines emotion regulation as consisting of level of awareness/labeling, modulation and arousal, modulation of expression, acceptance of affective experience, and reflection on experience. The Client Emotional Productivity Scale-Revised (Auszra et al., Citation2013) measures the degree to which a patient experiencing a primary emotion in an effective and useful manner (attending, symbolization, congruence, acceptance, regulation, agency, and differentiation). The Classification of Affective-Meaning State (Pascual-Leone & Greenberg, Citation2005) classifies patient emotional state into specific types of primary or secondary emotions based on vocal tone, involvement, and meaning. The Achievement of Therapeutic Objectives Scale (Berggraf et al., Citation2012) includes a subscale of Activating Affects, and the Client Expressed Emotional Arousal Scale-III-R (Machado et al., Citation1999) measures expressed emotions in terms of its intensity and type (anger, fear, joy, love, sadness, and surprise) based on the vocal quality and nonverbal behaviors.

In addition, there are a number of self-report measures of ER that would typically be completed by patients’ post-session; adequate reliabilities and validities have been reported for all. These include: Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Gross & John, Citation2003), Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004), Emotion Dysregulation Questionnaire (Gill et al., Citation2021), Action and Acceptance Questionnaire-II (Bond et al., Citation2011), Affective Style Questionnaire (Hofmann & Kashdan, Citation2010), Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (Berking & Znoj, Citation2008), Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Garnefski et al., Citation2001), Affect Integration Inventory (Solbakken et al., Citation2011), Distress Tolerance Scale (Simons & Gaher, Citation2005), Meta-emotion Scale (Mitmansgruber et al., Citation2008), Emotional Processing Difficulties Scale-Revised (Faustino et al., Citation2022), Emotion Regulation Goals Scale (Brandão et al., Citation2022), and Dimensions of Openness to Emotions (Reicherts, Citation2007). Several scales tapping common positive and negative emotions are also sometimes used as client self-report measures of emotion regulation: The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson et al., Citation1988) and Profiles of Mood State Questionnaires (Mcnair et al., Citation1971). In addition, the Self-Compassion Scale (Neff, Citation2003) measures how individuals respond to emotionally distressing events.

Zelkowitz and Cole (Citation2016) examined convergent and discriminant validity of eight self-report emotion regulation scales with a large university student sample. Exploratory factor analysis revealed three factors: out-of-control negative emotions representing the degree to which a person experiences strong negative emotions that are beyond one’s ability to regulate; emotional awareness and expression representing the degree to which individuals are aware of, admit to, and express strong pro-social emotions ranging from joy to guilt; and cognitive strategies for emotion regulation, reflecting concrete cognitive strategies for regulating negative emotion such as positive reappraisal, refocusing on planning, and putting into perspective.

Clinical Examples

In the following, we present three examples of working with emotional regulation. All three are within the context of psychotherapy practice from the United States with experienced therapists of each orientation.

AEDP Methods for Working with Dysregulated Emotions

The first example is taken from Lamagna (Citation2021) who illustrates the work with emotion dysregulation in AEDP. A married white female patient in a late middle age (P) on the verge of leaving her husband was flooded with distressing emotions.Footnote1 The therapist is an experienced AEDP white male therapist.

(Getting more distressed) It just hurts so much. (tears up) It’s still so close — that feeling . . . (pause) and I feel afraid of it.

Yes. Let me help you with that feeling.

I don't know what I'm feeling. It's too hard for me (increasingly agitated, gasping with tears in her eyes).

Linda . . . can you just check in with me for a second? Can you feel me here with you?

[Not registering the therapist’s statement] It all hurts too much. I miss my mother. (breaks into sobs).

(Softly) Yes.

(Sobbing) I missed so much.

(Slowly and with softness) Yeah, you did. Keep breathing.

I keep telling myself I'm doing well. I have this wonderful world around me . . . (sobs)

Can you check in and see that I'm here with you? See if we can ask this distressed part of you if she would be willing to separate out —- just a little bit. And if she won’t, it's okay. We'll figure out other ways of helping.

I’m just surprised it's so deep.

Okay. Do you have a sense whether there is a willingness for the distress to step back? Did you feel any shifting in your body?

I’m just able to breathe. (Seems slightly calmer)

Just notice that you can breathe now. (long pause) What are you noticing now?

The therapist first responded with calling attention to his empathic presence, using a gentle tone and slowed-down speech, to dyadically regulate the patient’s dysregulation that exacerbated her sense of aloneness. Then he used physical regulation (breathing) to help the patient attend to and accept the somatic experience of her emotion, to which the patient responded partially. The therapist also used intra-relational method which asked the patient to separate from the distressed part of herself. The patient finally made a meaningful contact with the therapist and partially regulated her distressing emotion.

Affect-oriented Methods for Enhancing Emotional Awareness

In the following vignette (from Paivio & Pascual-Leone, Citation2010), a young adult male patient, who had complex PTSD, felt he could never rely on others for support.Footnote2 Acknowledging his emerging sense of insecurity and neediness was uncomfortable and made him uneasy. The experienced middle-age white therapist oriented the patient’s attention to emergent feelings and aimed to help him allow the emotional experience and increase his emotional awareness.

So, it’s about feeling alone, that’s the main concern, like you can’t handle it?

It’s not, “can’t handle it,” exactly, but … lonely. I hate it.

OK, stay with that lonely feeling. It’s uncomfortable, I know, but let’s explore it a bit.

Like, I hate coming home from work, the apartment is so empty, we used to talk about stuff. She always seemed to understand, well, at least listen (laughs) … Like now I‘m just floundering around …

Floundering, directionless. So, she was like your anchor, it’s like you were so very attached to her.

Yes, I guess I was.

And now she’s gone, you’ve become unattached, not only lonely but kind of insecure?

Yes, I do feel insecure, less confident, it’s weird. I never realized how much I depend on her.

Say more, depended on her for what?

UP Methods for Addressing Emotional Avoidance

The third example, taken from the UP for emotional disorders by Barlow et al. (Citation2018), addresses patient’s emotional avoidance and concerns about being more in the present with her emotional experiences in the module of mindful emotional awareness. The therapist is a middle age experienced white male, while the patient is a young adult white female.

I don’t like to sit still— it makes me more anxious.

Tell me more— what happens when you sit still?

I don’t know— I just feel like I should be doing something. I feel like if I stop thinking about everything I need to do, my whole day will fall apart. I’m also afraid I’ll start thinking about things I’d really rather not think about.

So by sitting still and focusing on the present, you’re afraid you will be losing control of things that are supposed to happen today and that you might start thinking about things that have happened in the past?

Yeah, and that just makes me even more anxious.

So, you are not late for anything at the moment, but you are focusing on the possibility that

you might be late later on. How does focusing on the possibility you might be late later on make you feel?

Anxious!

And what about the information that right now, in this moment, you are not running late?

Well, much less anxious. But I still could run late later!

The thing is, you have no way of knowing exactly what may happen later. You may hit traffic or your doctor’s appointment might run over. Or, alternatively, you might find the roads are clear and your appointment only lasts 15 minutes instead of the scheduled 30 minutes. In other words, you just don’t know. The only thing you do know for sure is that you are in this office right now, and at the moment you are not late for anything. This means that the only thing that is different about worrying about the future as opposed to paying attention to the present moment is that one makes you really anxious and the other makes you less anxious.

In this excerpt, the therapist uses a psychoeducational approach to help the patient focus on the present rather than worrying about the future. He thus tried to help her modulate her anxiety by differentiating the anxious thoughts from the external reality.

Previous Reviews

Sloan and associates (Citation2017) identified 67 studies that measured changes in both emotion regulation and psychopathology following a psychological treatment, both individual and group. The treatments examined included affect-focused therapies such as EFT and STDP, as well as structured therapies such as ACT, CBT, DBT, EMT, and MBCT. Both maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and overall emotion dysregulation significantly decreased at post-treatment in all but two studies regardless of (a) specific treatment, (b) the measure of emotion regulation, and (c) the patient’s disorder.

Moltrecht and colleagues (Citation2021) examined 21 RCTs of psychological treatments for improving ER in youth (from ages 6–24). These treatments improved patients’ ER, which in turn was associated with the improvements in psychopathology, but effect sizes were small.

A meta-analysis by Daros et al. (Citation2021) included 90 RCTS on treating depression and anxiety among patients aged from 14 to 24. Treatments included a variety of cognitive-behavioral therapies, such as ACT, CBT, and DBT, as well as ERT. Patients’ ER skills significantly improved, which was positively related to improvements in their depression and anxiety.

In sum, these meta-analyses generally showed the positive effect of structured treatment packages on ER. They did not, however, review the specific components of treatments associated with the changes in ER.

Research Review

Search Strategy and Inclusion Criteria

We searched PUBMED, PsycINFO, and Web of Science between August 2021 and May 2022 using the following terms: counseling or therapy, therapist response, therapist interventions, therapist strategies, emotion regulation, emotional experience, outcome, and emotional expression. We also asked colleagues for articles that might have been missed in the search.

The following inclusion criteria were set: (a) actual individual psychotherapy studies (no analogues), (b) published in English, (c) included actual adult patients (age 18 or over) with psychological problems, (d) included at least one validated self-report or observational measure of ER, (e) included a measure of immediate, intermediate, or distal outcome. Studies were excluded if (a) the treatment was predominantly given in a group format or in an e-learning format; (b) they consisted of analog sessions with those within a normative population; and (c) the studies did not report sufficient data on above inclusion criteria (e.g., pre- and post-treatment means, SDs, sample sizes) or obvious errors in these values were found (e.g., unusually large effect sizes).

Identified publications were downloaded from the databases. If relevant literature was identified during the abstract screening, we manually screened their reference lists for further eligible publications. The selected studies were appraised independently by the first two authors for methodological aspects, such as sampling and sample characteristics according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The two authors discussed and came to agreement when the eligibility of a study was unclear. The final list was examined by the third author.

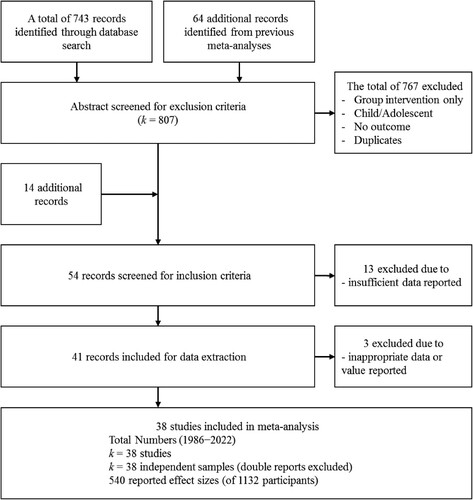

The flow chart provides an overview of the extraction procedure (). The initial web search identified 743 articles. We added 64 additional records identified from previous meta-analyses. From a total of 807 studies, 763 articles were excluded based on the abstract and method screening. An effectiveness study on AEDP (Iwakabe et al., Citation2022) was added because it included an ER measure. In total, 44 studies entered the full text screening. Of these, 13 papers had to be excluded due to insufficient data reported. Thirty-one studies matched the selection criteria and provided sufficient data. During the data extraction, three studies were excluded because some values were clearly wrong (e.g., effect size d > 3.0).

ER and Immediate and Intermediate Outcomes

We first reviewed the literature on immediate and intermediate in-session treatment outcomes. Immediate outcomes were typically assessed in the subsequent speaking turn or the same segment of a session in which a therapist method was used. Intermediate outcomes were assessed with self-report ER questionnaires administered at post session after a particular intervention module such as emotional awareness skills module was used.

summarizes a total of eight studies (84 clients and 33 therapists) of ER in association with immediate in-session outcomes and two studies (14 clients and 2 therapists) of intermediate outcomes. Most studies were multiple case studies, and one was a qualitative study. Given the small number of studies, we could not conduct a meta-analysis. Instead, we used box scores (our judgment based on the evidence of the outcomes) to aggregate the effects of ER methods across studies.

Table I. Studies of immediate and intermediate outcomes of emotion regulation methods.

contains the coded results of the 10 studies. For all outcomes, the three authors read each study and consensually arrived at box score for each outcome: “+” denotes a positive effect, “ = ” denotes a neutral/no effect, and “−“ denotes a negative effect. We assigned +1 to a positive box score, 0 to a neutral box score, and −1 to a negative box score in order to determine an overall box score for each outcome across samples. Furthermore, in order to account for sample size differences, we then multiplied the box score by the sample size for the finding, summed across the samples, and then divided into the total sample size to get a weighted box score for each immediate and intermediate outcome. We considered scores between −1 to -.5 negative, between -.49 to + .49 neutral, and between .5 to +1 positive.

Table II. Studies included in meta-analysis of treatment distal effects on patient emotion regulation.

For immediate outcomes, we first looked at five studies of client experiencing. In two studies of short-term psychodynamic therapy, plan-compatible interpretations were associated with the higher level of client experiencing (Silberschatz et al., Citation1986; Silberschatz & Curtis, Citation1993). Similarly, in client-centered therapy, interpretations referring to feelings given with particular nonverbal qualities were associated with a higher level of experiencing (Gazzola & Stalikas, Citation1997). In Hill et al. (Citation1988), however, interpretations did not have a higher experiencing level compared to other response modes such as self-disclosure, open question, and approval. Similarly, Stalikas and Fitzpatrick (Citation1996) did not find a significant relationship between therapist response modes and the client experiencing. There were thus three positive and two neutral box scores. The weighted box score across these five studies was .50 for interpretations on ER as measured with the client experiencing scale.

We also examined three short-term dynamic psychotherapy studies of therapist affect-oriented skills including confrontation on affect, defenses, and facilitative/supportive methods (Town et al., Citation2012) and focusing on affects (Ulvenes et al., Citation2014) in association with adaptive affect. Therapist focus on affect was associated with a higher level of adaptive affect experiences, which is a part of ER via emotional transformation. In a qualitative study, Nakamura and Iwakabe (Citation2018) found that the immediate outcome of experiential methods was arriving at an emotional resolution. For these three studies, there were three positive box scores; the average weighted box score was 1.

In terms of intermediate outcomes, Bentley and colleagues (Citation2017) tested the introduction of mindful emotional awareness skills and emotion modulation skills related to improvements in specific areas of ER (The Southanmpton Mindfulness Questionnaire for mindful emotional awareness and The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-Reappraisal Subscale for emotion modulation) in the Unified Protocol. The result showed no module-specific effects. Abasi et al. (Citation2021) studied four cases of Emotion Regulation Therapy for social anxiety disorder in which the introduction of ER modulation skills component had an additive effect to the mindful emotional awareness component that was initially given. They used the acceptance subscale of Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale for emotional awareness, the Affect Intensity Measure for emotional modulation, and Reappraisal subscale of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for adaptive emotion regulation strategy for every session. Neither study found module-specific effects, though most patients achieved reliable change by the end of the course of treatment on these emotion regulation scales as well as their symptoms for social anxiety. Box scores for module-specific outcome are neutral for three emotion regulation scales.

In sum, immediate outcomes (client experiencing and activating affect) were positive, indicating that interpretations focusing on immediate feelings with gentle and tentative manner of delivery and focusing on the patient immediate emotional experience resulted in a higher level of experiencing and adaptive affect. The experiencing level, however, does not specifically tell us about what aspects of emotion regulation is at work. On the other hand, Nakamura and Iwakabe (Citation2018) showed that the process of emotional change leading to a regulated emotional state may involve qualitative shifts from secondary emotions which are symptomatic emotional distress such as helplessness, anxiety, and feeling hurt, via more painful emotions to grief and self-compassion, followed by positive emotional experience with the therapist. This finding suggests that ER involves overcoming avoidance and defenses to allow distressing emotions, facing more difficult and painful emotions, allowing of underlying adaptive emotions and reflecting on emotional experience in the therapeutic relationship.

In contrast, no module specific effects of mindful emotional awareness or emotion modulation skills were found in studies on intermediate outcomes, though they were effective in improving ER. Bentley et al. (Citation2017) suspected that different therapist methods may address the extinction of distress in response to intense emotions. They also suggested that individuals respond differently to different treatment modules.

ER and Distal Treatment Outcomes

From the search strategy detailed above, 28 independent studies encompassing a total of 1034 patients and 201 therapists (the number of therapists was not cited in 10 studies) were included in the meta-analysis of distal outcomes. The main characteristics of the 28 included studies are summarized in . The data on which our analysis is based span over 15 years (2007–2022) and consist of published studies using independent samples collected in naturalistic settings (k = 18) and RCTs (k = 10). The number of eligible studies (k = 28) included in this meta-analysis is smaller than the size of previous meta-analyses because we included only individual treatments with clinical samples. ACT (k = 7), DBT (k = 3), and UP (k = 2), were the most commonly employed treatment packages. These therapies had some group components (k = 7) in addition to individual therapy. Although one study compared online intervention with in-person intervention, we included only the in-person data in this meta-analysis. A variety of psychological disorders and problems were treated, including anxiety disorders, eating disorder, borderline personality disorder, and substance use disorder.

The most frequently used outcome scales were DERS (k = 13), AAQ (k = 10), and ERQ (k = 5). Although they measure somewhat different aspects of ER, we combined them in one analysis given that moderate to high correlations have been reported among them. We report both overall mean scores and subscale means when they were available (). For the meta-analysis, we used effect sizes for the full scale unless specified.

We conducted a series of random effects models. This model is based on the assumption that the studies in this meta-analysis were randomly sampled from a population of studies. All analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Borenstein et al., Citation2013). First, we tested an overall pre-and post-treatment difference in ER. Second, we examined potential moderators –whether effect sizes systematically varied due to (a) measures, (b) types of treatments, (c) types of control group, and (d) type of disorder. In addition, comparisons between the treatment group and different control groups were tested when available. Treatment effect was estimated using the weighted mean effect size Hedges’ g.

The random effects model with all 28 independent studies resulted in a large treatment effect (g = 0.82, 95% CI [0.71, −0.93], p < .001) compared to no treatment/wait list. That is, multiple therapies evidenced large improvements in patient ER compared to no treatment or pre to post treatment. At the same time, there was a large heterogeneity in the effect sizes, I2 = 82.66% (Q = 155.68, df = 27, p < .001).

We also calculated the effect size of pre-treatment to 2-to 6-month follow-up for the 10 studies that reported those data (g = 0.86, 95% CI [0.59, −1.14], p < .001; I2 = 74.06; Q = 34.69, df = 9, p < .001) and pre-treatment to 12-month follow-up for 3 studies (g = 0.71, 95% CI [0.26, −1.15], p = .002; I2 = 89.37; Q = 18.81, df = 2, p < .001). The results indicate that treatment gains in ER were largely maintained; there was no significant deterioration from post-treatment to 2- to 6- and 12-month follow-up (for 2- to 6-month, k = 10; g = −0.07, 95% CI [−0.26, - 0.12], p = .456; I2 = 58.02; Q = 21.44, df = 9, p = .011; for 12-month, k = 3; g = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.29, - 0.35], p = .871; I2 = 83.12; Q = 11.85, df = 2, p = .003). Although the number of studies with the follow-up data was small, the treatment effect on ER was maintained after termination.

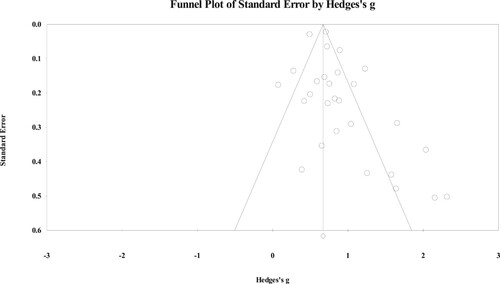

The fail-safe N indicated that approximately 6811 studies with an effect size of zero would be need to be published in order to bring the weighted mean effect below .10, or practical significance. We also calculated Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill. The adjusted effect size for a random effects model was g = 0.71 (observed value g = 0.82, 95% CI [0.60, - 0.83]). All our data are based on a search of electronic databases and included only published articles, which may have resulted in bias toward larger N studies and positive effect sizes. presents a funnel plot, which is a diagram of standard error on the Y axis and the ES on the X axis.

Given the large heterogeneity in effect sizes, we conducted a series of moderator analyses. The moderator analyses related to the ER measure, therapy type, comparison group, and patient type were all statistically significant. The effect sizes for each ER measure are presented in . The effect sizes for the DERS, AAQ, and SCS as outcome measures were similar (from 0.86 to 0.97), whereas effect sizes for the suppression subscale in ERQ were significantly smaller in comparison (g = 0.49). also shows the average effect sizes for the psychological treatments on the ER outcome. ACT (k = 7; g = 0.95) and DBT (k = 3; g = 1.11) had slightly larger effect sizes than CBT and UP, but all were moderate to large effect sizes. The effect size comparing the ER treatment against active control (k = 9) was g = 0.67 (95% CI [0.39, −0.94], p < .001). Compared to waiting list group, the effect size was significantly larger (k = 3; g = 1.51, 95% CI [0.85, −2.18], p < .001). For the 16 studies with no control group, the effect size was also large (g = 0.83, 95% CI [0.70, −0.96], p < .001).

Table III. Effect sizes by outcome assessment timet, ER measure, treatment package, control group, disorder.

The psychological treatments were more effective for depression and anxiety (k = 10; g = 0.82, 95% CI [0.60, −1.05], p < .001), personality disorder (k = 5; g = 0.93, 95% CI [0.61, −1.26], p < .001; mostly of borderline personality disorder), and substance use disorder (k = 2; g = 0.85, 95% CI [0.47, −1.23], p < .001) than eating disorder (k = 4; g = 0.81, 95% CI [0.34, −1.27], p = .001). The number of sessions (g = −0.001), year of publication (g = 0.006), the number of participants (g = −0.00) bore no systematic relation to the ER effect sizes (p > .33).

Possible Negative Effects and Harm

Therapists using affect-focused methods to activate or evoke strong emotions need to be cautious when working with patients with impulse control problems, active substance abuse, and those whose dysregulation is exacerbated due to organic factors, including thought disorders (Greenberg, Citation2015). Individuals suffering from these disorders may not contain strong emotions and as a result act out on them. Affect-focused methods may not lead to patient’s productive emotional experience when patients are feeling negative toward the self, such as shame, guilt, and self-contempt (Ulvenes et al., Citation2014).

There has been no evidence that suggests that ER methods lead to higher risk for dropouts and negative effects than psychotherapy methods that do not directly focus on or evoke emotional experience. Nonetheless, future studies need to identify patient characteristics that are associated with non-improvement and deterioration.

Limitations of the Research

Few studies have examined therapist moment-to-moment methods and their immediate, in-session and intermediate effects on patient ER. Virtually all studies have examined the effects of multicomponents treatment packages on distal ER outcomes. The overall treatments prove effective in enhancing ER, but we do not know which specific components or methods account for the improvement. Affect-focused methods and structured methods are quite different. Common and different change processes according to each method should be delineated.

Another important task is to define ER and its multiple facets. There are several similar concepts, such as emotional processing and emotional experiencing, and their differences as well as overlaps have not yet been empirically delineated.

Future researchers can also examine the therapeutic relationship in ER work. Implicit ER is hypothesized to develop through internalizing an empathic therapist. One study showed that patients with therapists who had higher ER ability had significantly better improvements in emotion regulation (Abargil & Tishby, Citation2021). Future researchers could also examine common and unique factors associated with ER methods of different orientations in the context of particular therapeutic relationships.

The vast majority of studies in our meta-analysis were conducted in the United States among samples of predominantly White individuals. Ethnoracial status, gender differences, socioeconomic status, and other cultural identity factors have not been adequately examined.

The measurement of ER as an outcome has mostly been conducted using self-report scales; however, they may not capture the variability in how individuals spontaneously select and implement ER strategies (Aldao, Citation2013). Self-report questionnaires tend to overlook natural fluctuations of ER in response to daily environmental demands and emotional experiences. They are also subject to recall bias and do not necessarily correspond to the concurrent report of ER (Aldao et al., Citation2010; Solhan et al., Citation2009).

An alternative to the self-report scales is ecological momentary assessment, a set of techniques that utilize repeated sampling of individuals’ real-time behaviors by the use of mobile and internet technology (Shiffman et al., Citation2008). This might identify how a particular therapist method can affect patient’s ER in their daily life. In addition, the moment-to-moment measure of ER can be used to test the immediate effect of therapist methods and relationship behaviors. Common autonomic and electromyographic measures may be used to track physiological arousal (Zaehringer et al., Citation2020). Motion energy analysis (Ramseyer, Citation2020) using an automated computer program may be also an effective way to track emotion regulation in the moment-to-moment manner. Nonverbal synchrony, or the coordination of patient’s and therapist’s bodily movement, has been shown to be associated with psychotherapy outcome and also with emotion regulation (Tschacher et al., Citation2014). Considering that ER occurs dyadically (Fosha, Citation2001), a combination of these measures may detect microprocess of therapist method and relational behaviors.

Training Implications

Given the meta-analytic evidence that multiple psychological treatments lead to improvement in ER for a range of psychological problems, trainees could benefit from learning about ER as well as its therapeutic methods. Students may learn to use observer rating scales to identify in-session markers for ER. They also can learn methods to increase emotional awareness, identify emotional avoidance, modulate dysregulated emotions, and transform maladaptive emotions with adaptive emotions as these are frequent components of ER work.

We suspect that deliberate practice might prove helpful in mastering affect-focused methods and related skills (Goldman et al., Citation2021). The therapist’s use of voice and nonverbal behavior is critical in communicating empathy (Abargil & Tishby, Citation2021) and helping patients modulate their emotions (Paivio & Laurent, Citation2001). Trainees can practice these responses while focusing on their voice and nonverbals associated with ER, repeatedly watch their performance, receive feedback from supervisors, incorporate it, and practice the skill until it is mastered. One of the components of deliberate practice training is the acquisition of inner skills for trainees to regulate themselves. Working with dysregulated patients can arouse strong emotional reactions in therapists. Trainees need to develop their emotional capacity to be aware of their own emotional state, stay empathically attuned to their patients, and adjust their verbal and nonverbal responses. In most affect-focused therapies, videotaped supervision is the norm in which both supervisor and supervisee track the moment-to-moment emotional process and formulate therapist responses that are most facilitative of emotional change (e.g, Greenberg & Tomescu, Citation2017; Prenn & Fosha, Citation2017).

Finally, trainees can benefit from receiving training in treatments focusing on ER. ACT, AEDP, DBT, and EFT demonstrated larger effect sizes on ER in our meta-analysis. Specific instructions for structured exercises and homework will be helpful tools for trainees working with patients with emotional dysregulation.

Therapeutic Practices

The meta-analysis demonstrated large gains in patient ER from psychological treatments, but empirical evidence is lacking on the effectiveness of specific components or therapist methods. Hence, we offer recommendations based on the sparse research evidence and our clinical practice:

Enhance patient ER capacity for a variety of behavioral disorders.

Use either affect-oriented methods or structured psychoeducational and skill training methods to work with ER.

Employ steps associated with enhancing patient ER: undoing experiential avoidance, enhancing emotional awareness, promoting a full emotional experience, understanding the meaning of experience, and learning strategies to cope with distress.

Provide a therapeutic relationship characterized by empathy, validation, and support to help patients develop ER capacity. Such a relationship is frequently internalized by the patient and may function to change schemas that are putatively at the root of emotional dysregulation.

Address patients’ fearful avoidance or suppression of emotional experience via psychoeducation.

Consider the patient’s sense of self in focusing on ER in session: When patients are in their negative self-state, they frequently do not recognize positive aspects of themselves and focusing on emotion is not likely to bring adaptive affects.

Consider the patient’s cultural identity and worldview as well as the context in which the patient’s emotional experience occurs in evaluating the appropriateness of ER.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The clinical material presented here was gathered in compliance with the APA ethics code and a written consent from the patient was obtained. The original material was modified for brevity.

2 The case material was fictitious clinical amalgams for the sake of clinical illustration by the authors.

References

- Abargil, M., & Tishby, O. (2021). How therapists’ emotion recognition relates to therapy process and outcome. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2680

- *Abasi, I., Pourshahbaz, A., Mohammadkhani, P., Dolatshahi, B., Moradveisi, L., & Mennin, D. S. (2021). Emotion regulation therapy for social anxiety disorder: A single case series study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465821000175

- Abbass, A. (2015). Reaching through resistance: Advanced psychotherapy techniques. Seven Leaves Press.

- Aldao, A. (2013). The future of emotion regulation research: Capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(2), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612459518

- Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

- *Arch, J. J., Eifert, G. H., Davies, C., Plumb Vilardaga, J. C., Rose, R. D., & Craske, M. G. (2012). Randomized clinical trial of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for mixed anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 750–765. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028310

- Auszra, L., Greenberg, L. S., & Herrmann, I. (2013). Client emotional productivity-optimal client in-session emotional processing in experiential therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 23(6), 732–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.816882

- *Axelrod, S. R., Perepletchikova, F., Holtzman, K., & Sinha, R. (2011). Emotion regulation and substance use frequency in women with substance dependence and borderline personality disorder receiving dialectical behavior therapy. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.535582

- Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Fairholme, C. P., Ellard, K. K., Boisseau, C. L., Allen, L. B., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2017). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press.

- Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Sauer-Zavala, S., Murray-Latin, H., Ellard, K. K., Bullis, J. R., Bentley, K., Boettcher, H., & Cassiello-Robbins, C. (2018). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- *Beaumont, E., Galpin, A., & Jenkins, P. (2012). Being kinder to myself': A prospective comparative study, exploring post-trauma therapy outcome measures, for two groups of clients, receiving either cognitive behaviour therapy or cognitive behaviour therapy and compassionate mind training. Counselling Psychology Review, 27(1), 31–43.

- *Bentley, K. H., Nock, M. K., Sauer-Zavala, S., Gorman, B. S., & Barlow, D. H. (2017). A functional analysis of two transdiagnostic, emotion-focused interventions on nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(6), 632–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000205

- Berggraf, L., Ulvenes, P. G., Wampold, B. E., Hoffart, A., & McCullough, L. (2012). Properties of the achievement of therapeutic objectives scale (ATOS): a generalizability theory study. Psychotherapy Research, 22(3), 327–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2011.653997

- Berking, M., & Lukas, C. A. (2015). The affect regulation training (ART): a transdiagnostic approach to the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.02.002

- Berking, M., Wupperman, P., Reichardt, A., Pejic, T., Dippel, A., & Znoj, H. (2008). Emotion-regulation skills as a treatment target in psychotherapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(11), 1230–1237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.005

- Berking, M., & Znoj, H. (2008). Entwicklung und Validierung eines Fragebogens zur standardisierten Selbsteinschätzung emotionaler Kompetenzen [Development and validation of a self-report measure for the assessment of emotion-regulation skills]. Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie, Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 56(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1024/1661-4747.56.2.141

- *Bianchini, V., Cofini, V., Curto, M., Lagrotteria, B., Manzi, A., Navari, S., Ortenzi, R., Paoletti, G., Pompili, E., Pompili, P. M., Silvestrini, C., & Nicolò, G. (2019). Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) for forensic psychiatric patients: An Italian pilot study. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health: CBMH, 29(2), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.2102

- Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., Waltz, T., & Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire-II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2013). Comprehensive meta-analysis version 3. Biostat.

- Brandão, T., Brites, R., Hipólito, J., & Nunes, O. (2022). The emotion regulation goals scale: Advancing its psychometric properties using item response theory analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23343

- Campos, J. J., Frankel, C. B., & Camras, L. (2004). On the nature of emotion regulation. Child Development, 75(2), 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00681.x

- Chadwick, P., Hember, M., Symes, J., Peters, E., Kuipers, E., & Dagnan, D. (2008). Responding mindfully to unpleasant thoughts and images: Reliability and validity of the southampton mindfulness questionnaire (SMQ). The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47(4), 451–455. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466508X314891

- *Chavooshi, B., Mohammadkhani, P., & Dolatshahee, B. (2017). Telemedicine vs. in-person delivery of intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy for patients with medically unexplained pain: A 12-month randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 23(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X15627382

- Cloitre, M., Koenen, K. C., Cohen, L. R., & Han, H. (2002). Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1067–1074. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1067

- Curtis, J. T., Ransohoff, P., Sampson, F., Brumer, S., & Bronstein, A. (1986). Expressing warded-off contents in behavior. In J. Weiss, H. Sampson, & the Mount Zion Psychotherapy Research Group (Eds.), The psychoanalytic process: Theory, clinical observation, and empirical research (pp. 187–205). Guilford Press.

- *Dalrymple, K. L., & Herbert, J. D. (2007). Acceptance and commitment therapy for generalized social anxiety disorder: A pilot study. Behavior Modification, 31(5), 543–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507302037

- Daros, A. R., Haefner, S. A., Asadi, S., Kazi, S., Rodak, T., & Quilty, L. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of emotional regulation outcomes in psychological interventions for youth with depression and anxiety. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(10), 1443–1457. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01191-9

- *Dehlin, J. P., Morrison, K. L., & Twohig, M. P. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for scrupulosity in obsessive compulsive disorder. Behavior Modification, 37(3), 409–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445512475134

- *Doorn, K. A., Macdonald, J., Stein, M., Cooper, A. M., & Tucker, S. (2014). Experiential dynamic therapy: A preliminary investigation into the effectiveness and process of the extended initial session. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(10), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22094

- Elliott, R., Hill, C. E., Stiles, W. B., Friedlander, M. L., Mahrer, A. R., & Margison, F. R. (1987). Primary therapist response modes: Comparison of six rating systems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(2), 218–223. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.55.2.218

- Farchione, T. J., Tirpak, J. G. W., & Olesnycky, O. S. (2021). The unified protocol: A transdiagnostic treatment for emotional disorders. In A. Wenzel (Ed.), Handbook of cognitive behavioral therapy: Overview and approaches (pp. 701–730). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000218-024

- Faustino, B., Vasco, A. B., Da Silva, A. N., & Barreira, J. (2022). Emotional processing difficulties scale-revised: Preliminary psychometric study. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 21(4), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2022.2028661

- Fosha, D. (2001). The dyadic regulation of affect. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:2<227::AID-JCLP8>3.0.CO;2-1

- Fosha, D., Edlin, J., & Iwakabe, S. (2018). AEDP 9 + 1 Change Process Scale. Unpublished manuscript.

- Fosha, D, ed. (2021). Undoing aloneness & the transformation of suffering into flourishing: AEDP 2.0. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000232-000

- Frederickson, J. J., Messina, I., & Grecucci, A. (2018). Dysregulated anxiety and dysregulating defenses: Toward an emotion regulation informed dynamic psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2054. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02054

- Friedlander, M. L. (1982). Counseling discourse as a speech event: Revision and extension of the Hill counselor verbal response category system. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 29(4), 425–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.29.4.425

- Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinhoven, P. (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(8), 1311–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6

- *Gazzola, N., & Stalikas, A. (1997). An investigation of counselor interpretations in client-centered therapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 7(4), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOPI.0000010886.33685.64

- Gill, D., Warburton, W., Sweller, N., Beath, K., & Humburg, P. (2021). The emotional dysregulation questionnaire: Development and comparative analysis. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 94(S2), 426–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12283

- *Glisenti, K., Strodl, E., & King, R. (2018). Emotion-focused therapy for binge-eating disorder: A review of six cases. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(6), 842–855. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2319

- Goldman, R. N., Vaz, A., & Rousmaniere, T. (2021). Deliberate practice in emotion-focused therapy. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000227-000

- *Goodman, M., Carpenter, D., Tang, C. Y., Goldstein, K. E., Avedon, J., Fernandez, N., Mascitelli, K. A., Blair, N. J., New, A. S., Triebwasser, J., Siever, L. J., & Hazlett, E. A. (2014). Dialectical behavior therapy alters emotion regulation and amygdala activity in patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 57, 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.06.020

- Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

- Gratz, K. L., Weiss, N. H., & Tull, M. T. (2015). Examining emotion regulation as an outcome, mechanism, or target of psychological treatments. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.02.010

- Greenberg, L. S. (2015). Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14692-000

- Greenberg, L. S. (2021). Changing emotion with emotion: A practitioner's guide. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000248-000

- Greenberg, L. S., & Tomescu, L. R. (2017). Supervision essentials for emotion-focused therapy. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/15966-000

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–295. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

- Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior Therapy, 35(4), 639–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80013-3

- Hill, C. E. (1985). Manual for counselor verbal response modes category system (Rev. Ed.). Unpublished manuscript. University of Maryland at College Park.

- Hill, C. E. (1986). An overview of the hill counselor and client verbal response modes category systems. In L. S. Greenberg & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook (pp. 131–160). Guilford Press.

- *Hill, C. E., Helms, J. E., Tichenor, V., Spiegel, S. B., O'Grady, K. E., & Perry, E. S. (1988). Effects of therapist response modes in brief psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35(3), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.35.3.222

- Hilsenroth, M. J., Blagys, M. D., Ackerman, S. J., Bonge, D. R., & Blais, M. A. (2005). Measuring psychodynamic-interpersonal and cognitive-behavioral techniques: Development of the comparative psychotherapy process scale. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 42(3), 340–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.42.3.340

- Hofmann, S. G., & Kashdan, T. B. (2010). The affective style questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(2), 255–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9142-4

- *Ito, M., Horikoshi, M., Kato, N., Oe, Y., Fujisato, H., Nakajima, S., Kanie, A., Miyamae, M., Takebayashi, Y., Horita, R., Usuki, M., Nakagawa, A., & Ono, Y. (2016). Transdiagnostic and transcultural: Pilot study of unified protocol for depressive and anxiety disorders in Japan. Behavior Therapy, 47(3), 416–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.02.005

- *Iwakabe, S., Edlin, J., Fosha, D., Thoma, N. C., Gretton, H., Joseph, A. J., & Nakamura, K. (2022). The long-term outcome of accelerated experiential dynamic psychotherapy: 6- and 12-month follow-up results. Psychotherapy. Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000441

- *Jain, S., Ortigo, K., Gimeno, J., Baldor, D. A., Weiss, B. J., & Cloitre, M. (2020). A randomized controlled trial of brief skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation (STAIR) for veterans in primary care. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(4), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22523

- Jones, E. E., Cumming, J. D., & Horowitz, M. J. (1988). Another look at the nonspecific hypothesis of therapeutic effectiveness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.56.1.48

- *Khoramnia, S., Bavafa, A., Jaberghaderi, N., Parvizifard, A., Foroughi, A., Ahmadi, M., & Amiri, S. (2020). The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 42(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2019-0003

- Klein, M. H., Mathieu-Coughlan, P., & Kiesler, D. J. (1986). The experiencing scales. In L. S. Greenberg & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook (pp. 21–71). Guilford Press.

- *Kumar, S., Feldman, G., & Hayes, A. (2008). Changes in mindfulness and emotion regulation in an exposure-based cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(6), 734–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-008-9190-1

- Lamagna, J. (2021). Finding healing in the broken places: Intra-relational AEDP work with traumatic aloneness. In D. Fosha (Ed.), Undoing aloneness & the transformation of suffering into flourishing: AEDP 2.0 (pp. 293–319). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000232-012

- Larsen, R. J., Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1986). Affect intensity and reactions to daily life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(4), 803–814. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.4.803

- Leahy, R. L., Tirch, D., & Napolitano, L. A. (2011). Emotion regulation in psychotherapy: A practitioner's guide. Guilford Press.

- Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

- Linehan, M. M. (2015). DBT skills training handout and worksheets (2nd. ed.). Guilford Press.

- *MacDonald, D. E., McFarlane, T. L., Dionne, M. M., David, L., & Olmsted, M. P. (2017). Rapid response to intensive treatment for bulimia nervosa and purging disorder: A randomized controlled trial of a CBT intervention to facilitate early behavior change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(9), 896–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000221

- Machado, P. P., Beutler, L. E., & Greenberg, L. S. (1999). Emotion recognition in psychotherapy: Impact of therapist level of experience and emotional awareness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(1), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199901)55:1<39::aid-jclp4>3.0.co;2-v

- McCullough, L., Larsen, A. E., Schanche, E., Andrews, S., Kuhn, N., & Hurley, C. L. (2003). Achievement of therapeutic objectives scale. Short-Term Psychotherapy research program at Harvard Medical School. Available from www.affectphobia.com.

- McMain, S., Korman, L. M., & Dimeff, L. (2001). Dialectical behavior therapy and the treatment of emotion dysregulation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:2<183::aid-jclp5>3.0.co;2-y

- McMain, S., Pos, A., & Iwakabe, S. (2010). Facilitating emotion regulation: General principles for psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Bulletin, 45(3), 16–21.

- Mcnair, D. M., Lorr, M., & Droppleman, L. F. (1971). Manual for the profile of mood states.

- Medley, B. (2021). Portrayals in work with emotion in AEDP: Processing core affective experience and bringing it to completion. In D. Fosha (Ed.), Undoing aloneness & the transformation of suffering into flourishing: AEDP 2.0 (pp. 217–240). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000232-009

- Mennin, D. S., Fresco, D. M., Ritter, M., & Heimberg, R. G. (2015). An open trial of emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder and cooccurring depression. Depression and Anxiety, 32(8), 614–623. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22377

- *Mennin, D. S., Fresco, D. M., O'Toole, M. S., & Heimberg, R. G. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder with and without co-occurring depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(3), 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000289

- Mitmansgruber, H., Beck, T. N., & Schüßler, G. (2008). Mindful helpers”: experiential avoidance, meta-emotions, and emotion regulation in paramedics. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(5), 1358–1363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.03.012

- Moltrecht, B., Deighton, J., Patalay, P., & Edbrooke-Childs, J. (2021). Effectiveness of current psychological interventions to improve emotion regulation in youth: A meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(6), 829–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01498-4

- *Monell, E., Clinton, D., & Birgegård, A. (2022). Emotion dysregulation and eating disorder outcome: Prediction, change and contribution of self-image. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 95(3), 639–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12391

- *Nakamura, K., & Iwakabe, S. (2018). Corrective emotional experience in an integrative affect-focused therapy: Building a preliminary model using task analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(2), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2150

- Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

- *Normann-Eide, E., Johansen, M. S., Normann-Eide, T., Egeland, J., & Wilberg, T. (2015). Personality disorder and changes in affect consciousness: A 3-year follow-up study of patients with avoidant and borderline personality disorder. PloS one, 10(12), e0145625. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145625

- *O'Toole, M. S., Renna, M. E., Mennin, D. S., & Fresco, D. M. (2019). Changes in decentering and reappraisal temporally precede symptom reduction during emotion regulation therapy for generalized anxiety disorder with and without co-occurring depression. Behavior Therapy, 50(6), 1042–1052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.12.005

- Paivio, S. C., & Laurent, C. (2001). Empathy and emotion regulation: Reprocessing memories of childhood abuse. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:2<213::aid-jclp7>3.0.co;2-b

- Paivio, S. C., & Pascual-Leone, A. (2010). Emotion-focused therapy for complex trauma: An integrative approach. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12077-000

- Pascual-Leone, A., & Greenberg, L. (2005). Classification of affective-meaning states. In A. Pascual-Leone (Ed.), Emotional processing in the therapeutic hour: “Why the only way out is through” (pp. 289–367). York University. https://www.uwindsor.ca/people/apl/sites/uwindsor.ca.people.apl/files/pascual-leone_greenberg_2005_cams_measure.pdf.

- *Petersen, C. L., & Zettle, R. D. (2009). Treating inpatients with comorbid depression and alcohol use disorders: A comparison of acceptance and commitment therapy versus treatment as usual. The Psychological Record, 59(4), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03395679

- Prenn, N. C. N., & Fosha, D. (2017). Supervision essentials for accelerated experiential dynamic psychotherapy. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000016-000

- *Price, C. J., Thompson, E. A., Crowell, S. E., Pike, K., Cheng, S. C., Parent, S., & Hooven, C. (2019). Immediate effects of interoceptive awareness training through mindful awareness in body-oriented therapy (MABT) for women in substance use disorder treatment. Substance Abuse, 40(1), 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2018.1488335

- Ramseyer, F. T. (2020). Exploring the evolution of nonverbal synchrony in psychotherapy: The idiographic perspective provides a different picture. Psychotherapy Research, 30(5), 622–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1676932

- Reicherts, M. (2007). Dimensions of openness to emotions (DOE): A model of affect processing, manual (Scientific report no. 168). University of Fribourg.

- Renna, M. E., Quintero, J. M., Fresco, D. M., & Mennin, D. S. (2017). Emotion regulation therapy: A mechanism-targeted treatment for disorders of distress. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 98. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00098

- Roemer, L., Orsillo, S. M., & Salters-Pedneault, K. (2008). Efficacy of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder: Evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(6), 1083–1089. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012720

- *Roemer, L., & Orsillo, S. M. (2007). An open trial of an acceptance-based behavior therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy, 38(1), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.04.004

- *Sauer-Zavala, S., Bentley, K. H., & Wilner, J. G. (2016). Transdiagnostic treatment of borderline personality disorder and comorbid disorders: A clinical replication series. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2015_29_179

- Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. Guilford Press.

- Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A., & Hufford, M. R. (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415

- Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Guilford Press.

- *Silberschatz, G., & Curtis, J. T. (1993). Measuring the therapist's impact on the patient's therapeutic progress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(3), 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.61.3.403

- *Silberschatz, G., Fretter, P. B., & Curtis, J. T. (1986). How do interpretations influence the process of psychotherapy? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(5), 646–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.54.5.646

- Simons, J. S., & Gaher, R. M. (2005). The distress tolerance scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion, 29(2), 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3

- Sloan, E., Hall, K., Moulding, R., Bryce, S., Mildred, H., & Staiger, P. K. (2017). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.002

- Solbakken, O. A., Hansen, R. S., Havik, O. E., & Monsen, J. T. (2011). Assessment of affect integration: Validation of the affect consciousness construct. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(3), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.558874

- Solhan, M. B., Trull, T. J., Jahng, S., & Wood, P. K. (2009). Clinical assessment of affective instability: Comparing EMA indices, questionnaire reports, and retrospective recall. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 425–436. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016869

- Solomonov, N., McCarthy, K. S., Gorman, B. S., & Barber, J. P. (2019). The multitheoretical list of therapeutic interventions–30 items (MULTI-30). Psychotherapy Research, 29(5), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1422216

- *Stalikas, A., & Fitzpatrick, M. (1996). Relationships between counselor interventions, client experiencing, and emotional expressiveness: An exploratory study. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 30(4), 262–271. https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/article/view/58562

- *Town, J. M., Hardy, G. E., McCullough, L., & Stride, C. (2012). Patient affect experiencing following therapist interventions in short-term dynamic psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 22(2), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2011.637243

- Tschacher, W., Rees, G. M., & Ramseyer, F. (2014). Nonverbal synchrony and affect in dyadic interactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1323. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01323

- *Twohig, M. P., Hayes, S. C., Plumb, J. C., Pruitt, L. D., Collins, A. B., Hazlett-Stevens, H., & Woidneck, M. R. (2010). A randomized clinical trial of acceptance and commitment therapy versus progressive relaxation training for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(5), 705–716. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020508

- *Ulvenes, P. G., Berggraf, L., Wampold, B. E., Hoffart, A., Stiles, T., & McCullough, L. (2014). Orienting patient to affect, sense of self, and the activation of affect over the course of psychotherapy with cluster C patients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(3), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000028

- *Walser, R. D., Garvert, D. W., Karlin, B. E., Trockel, M., Ryu, D. M., & Taylor, C. B. (2015). Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy in treating depression and suicidal ideation in veterans. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 74, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.012

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Watson, J. C., McMullen, E. J., Prosser, M. C., & Bedard, D. L. (2011). An examination of the relationships among clients’ affect regulation, in-session emotional processing, the working alliance, and outcome. Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2010.518637

- *Wonderlich, S. A., Peterson, C. B., Crosby, R. D., Smith, T. L., Klein, M. H., Mitchell, J. E., & Crow, S. J. (2014). A randomized controlled comparison of integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) and enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 44(3), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713001098

- Zaehringer, J., Jennen-Steinmetz, C., Schmahl, C., Ende, G., & Paret, C. (2020). Psychophysiological effects of downregulating negative emotions: Insights from a meta-analysis of healthy adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 470. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00470

- *Zalaznik, D., Weiss, M., & Huppert, J. D. (2019). Improvement in adult anxious and avoidant attachment during cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 29(3), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1365183

- Zelkowitz, R. L., & Cole, D. A. (2016). Measures of emotion reactivity and emotion regulation: Convergent and discriminant validity. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.045