?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective

This study examined the relationships between patient–therapist similarity and therapy outcome. We aimed to explore whether patient–therapist match in personality and attachment styles leads to a better therapy outcome.

Method

We collected data from 77 patient–therapist dyads in short-term dynamic therapy. Patients’ and therapists’ personality traits (Big-5 Inventory) and attachment styles (ECR) were assessed prior to beginning therapy. Outcome was measured on the OQ-45.

Results

When patients and therapists scored either high or low on neuroticism and conscientiousness we found a decrease in symptoms from beginning to end of therapy. When patients’ and therapists’ combined scores were either high or low on attachment anxiety, we found an increase in symptoms.

Conclusion

Match or mismatch on personality and attachment style in therapy dyads contributes to therapy outcome.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: This study suggests that pre-therapy personality traits and attachment styles of the patient and therapist are related to therapy outcome. A pre-therapy match or mismatch might be used to refer patients to therapists in order to achieve a better therapeutic outcome.

Introduction

Psychotherapy is a dyadic process during which patient and therapist form a unique relationship (Tronick, Citation2003), with the process affected by the individual characteristics of each participant. To date, studies have tended to view patients and therapists separately when examining the impact of their characteristics on process and outcome. Broadening the perspective, we hypothesized that studying the combination of the traits and attachment styles of both the patient and the therapist could shed new light on therapeutic relationships. Accordingly, this study examined whether patient–therapist similarity leads to a better therapeutic outcome.

Similarity in Relationships

There is a vast literature on similarity and compatibility in relationships. Similarity in personality has been found to be related to interpersonal attraction (Montoya et al., Citation2008); similarity in traits is a component of children's and adolescents’ formation of spontaneous friendships (Ilmarinen et al., Citation2017; Selfhout et al., Citation2010). Among married couples, similarity in values, attachment style, and personality traits has been associated with higher marital satisfaction and marital quality (Leikas et al., Citation2018; Luo & Klohnen, Citation2005; O’Rourke et al., Citation2011; Robins et al., Citation2000). Moreover, among married couples, the effects of personality on marital quality have been found to persist into old age (Wang et al., Citation2018).

Patient–Therapist Similarity

As noted, studies that have examined the influence of individual characteristics on psychotherapy process and outcome have tended to consider therapists and patients separately. Some studies have explored how patients’ needs, characters, or expectations played a role in therapy outcomes (Connolly Gibbons et al., Citation2003; Levy et al., Citation2018; McCarthy et al., Citation2008). Other studies have examined therapy tailored to patients’ religious or spiritual values (Captari et al., Citation2018) or their characteristics (Norcross & Wampold, Citation2011). Regarding therapists, several studies have investigated the relationship between various therapist characteristics and therapy outcome (Castonguay & Hill, Citation2017; Diener et al., Citation2007; Kim et al., Citation2006; Lingiardi et al., Citation2018; Wampold et al., Citation2017). However, research on the effects of patient–therapist similarity remains scarce.

In the current context, it is important to distinguish between similarity in “trait-like” features and in “state-like” dynamics. Trait-like refers to individual differences between patients and therapists, while state-like refers to change occurring throughout treatment (Zilcha-mano, Citation2017). Thus, the state-like view would focus on the mutual influences that therapists and patients have on each other's negative and positive emotions (Chui et al., Citation2016) or emotion regulation (Soma et al., Citation2020) within the therapy sessions. Another state-like issue that has drawn scholarly attention is therapists’ and patients’ congruence in the perception of therapy processes (i.e., therapy alliance, emotions, session events, etc.) and how this relates to session and therapy outcome (Atzil-Slonim et al., Citation2018; Jennissen et al., Citation2020; Rubel et al., Citation2018; Zilcha-mano, Citation2017).

By contrast, trait-like dynamics focus on pre-therapy features of both patients and therapists. Research on patients’ and therapists’ matching for personality characteristics is lacking. A recent study found that matched patient–therapist dyads (in terms of orientation on relatedness or self-definition) was linked to larger effect sizes on all outcome measures (Werbart et al., Citation2018). However, much remains to be explored in pre-therapy dyadic trait-like matches. The current study focused on two main trait-like domains: personality constructs and attachment style.

Personality Constructs

Personality is defined as a complex latent construct represented by a combination of characteristics. For the past 70 years, scholars have sought to formalize the factor structure of personality construct (Ferguson & Hull, Citation2018). Digman and Inouye (Citation1986) and McCrae and Costa (Citation1987) produced an influential model of personality factors, known as the “Big Five”: (i) neuroticism—the tendency to experience relatively high emotional distress; (ii) extraversion—the tendency to experience positive emotions and to be warm, gregarious, fun-loving, and assertive; (iii) openness to experience—the tendency to be curious, imaginative, creative, psychologically minded, and flexible; (iv) agreeableness—the tendency to be good-natured, courteous, helpful, and trusting; and (v) conscientiousness—the tendency to be habitually careful, reliable, hardworking, and purposeful (see O’Brien & DeLongis, Citation1996). These five factors are considered stable (Cobb-Clark & Schurer, Citation2012) and related to various issues, such as values (Roccas et al., Citation2002), resilience (Oshio et al., Citation2018), and mental health (Dash et al., Citation2019; Koorevaar et al., Citation2013; Lewis & Cardwell, Citation2020).

The Big Five personality factors have been associated with intimacy and relationship satisfaction (White et al., Citation2004). A meta-analysis found that high scores in agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion, and low scores in neuroticism were related to satisfaction in intimate relationships (Malouff et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, although sometimes opposites attract, similarity in personality domains has been associated with marital quality (Luo & Klohnen, Citation2005) and marital satisfaction (O’Rourke et al., Citation2011). Moreover, similar levels of the Big Five factors predicted choice of new friends among young adults (Selfhout et al., Citation2010) and children (Ilmarinen et al., Citation2017).

A recent meta-analysis (Bucher et al., Citation2019) found that lower patient neuroticism and higher extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness were associated with favorable therapy outcome. In addition, global therapist–patient personality similarity has been associated with better outcome (Coleman, Citation2006). Pérez-Rojas et al. (Citation2021) found that patients’ perceptions of similarity to their therapists on the Big-5 traits was related to better outcomes. More specifically, similarity on higher levels of conscientiousness and openness to experience and on lower levels of neuroticism was related to reports of stronger real relationships. Similarly, clients reported a stronger real relationship when they perceived their therapists were similarly high in extraversion; perceived similarity at high and low levels of agreeableness was also associated with stronger real relationships. Thus, the current study aimed to explore patient–therapist match on the Big Five factors and its relationship to symptoms reduction at the end of treatment. In line with the above results, and those presented by Bucher et al. (Citation2019) and Coleman (Citation2006), we expected that similarity in lower mutual neuroticism and higher mutual extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness would be related to better therapy outcomes.

Attachment Styles

According to John Bowlby (Citation1969/1982) the way an infant experiences their dependence on their caregivers—which he terms attachment—shapes long-term beliefs and behaviors in relationships (i.e., expectations, wishes, needs, and attitudes). Attachment styles persist from infancy to adulthood. Brennan et al. (Citation1998) defined two main attachment dimensions: anxiety (overdependence and anxiety in relations) and avoidance (difficulties in relying on others). Those two dimensions underline most attachment styles in maturity (Brennan et al., Citation1998; Mikulincer & Shaver, Citation2007). Attachment style is considered relatively stable, with more stability in adulthood compared to adolescence (Jones et al., Citation2018). Attachment style has been found to predict relationship quality and satisfaction (Candel & Turliuc, Citation2019; Noftle & Shaver, Citation2006) and marital satisfaction and quality (Bedair et al., Citation2020; Knoke et al., Citation2010; Mohammadi et al., Citation2016).

Both patient- and therapist-attachment styles are central components of the therapeutic process (Levy et al., Citation2018; Strauss & Petrowski, Citation2017). There is a substantial literature on the relationship between patient attachment style, alliance, and outcome. As alliance is strongly related to therapy outcome, greater attachment security among patients has been associated with stronger therapeutic alliances, whereas greater attachment insecurity has been associated with weaker therapeutic alliances (Diener & Monroe, Citation2011). A recent meta-analysis shows that not only do patients with secure attachment pretreatment show better psychotherapy outcomes than insecurely attached patients, the improvements in attachment security during therapy may coincide with better treatment outcome (Levy et al., Citation2018). Patients characterized by avoidant attachment style showed the least improvement (Wiseman & Tishby, Citation2014), and anxious and avoidant attachment styles were negatively related to patient rating of the working alliance (Bernecker et al., Citation2014). Patient attachment styles also influence their response to therapy ruptures and resolution strategies (Miller-Bottome et al., Citation2018). Likewise, therapist attachment style is related to their reflective functioning (Cologon et al., Citation2017) and their perceptions of ruptures and tension (Marmarosh et al., Citation2015). Moreover, therapist attachment anxiety was related to their ability to accurately perceive patient alliance. As therapists’ attachment anxiety increased, the difference between their and their patients’ alliance rating was greater (with therapists rating it as more negative) (Kivlighan & Marmarosh, Citation2018). However, considering both patient and therapist attachment styles, there are mixed results. Bucci et al. (Citation2016) found that when the difference is greater between patient and therapist preoccupied and dismissing attachment styles, the more favorable the therapist-rated and patient-rated alliance ratings would be. Alliance rating has a strong relation to therapy outcome (Flückiger et al., Citation2018). Moreover, Marmarosh et al. (Citation2014) found that patients’ alliance ratings were higher when therapists with high attachment anxiety treated patients with lower levels of anxiety. However, other studies have indicated the opposite. Wiseman and Tishby (Citation2014) found that similarity in low attachment avoidance style leads to a greater decrease in symptoms compared to dissimilarity. In addition, O’Connor et al. (Citation2019) found that agreement between patients and therapists on their alliance was high when their attachment styles were “matched” (either high or low in anxiety or avoidance). Due to the mixed results in patient–therapist match on attachment styles, we did not make directional hypotheses. Thus, in the current research, we looked at similarities and dissimilarities in both anxiety and avoidant attachment styles and their relation to therapy outcome and decrease in symptoms.

Research Hypotheses

The study examined the following two broad questions and sub-hypotheses regarding each of the issues:

Hypotheses 1a–1e: personality

Regarding the relationship between match or mismatch in therapist and patient personality traits and symptom change at the end of therapy, we hypothesized that similarity on lower levels of (1a) neuroticism and similarity on higher levels of (2b) extraversion, (3c) openness to experience, (4d) agreeableness, and (5e) conscientiousness would be related to favorable therapy outcomes.

Hypotheses 2a–2b: attachment styles

Regarding the relationship between match or mismatch in therapist and patient attachment styles and symptom change at the end of therapy, we left it as an open question: What are the relationships between similarity and dissimilarity in patient and therapist attachment styles and therapy outcome. We examined attachment style in two dimensions: (2a) attachment anxiety and (2b) attachment avoidant.

Method

Participants

Seventy-seven patients participated in the study. The sample consisted of 56 female and 21 male patients between the ages of 18 and 56 (mean age 27.8, SD = 5.98). Patients were diagnosed with mild depression and/or anxiety, according to DSM-5. Diagnoses were based on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I 5; Sheehan et al., Citation1998) and the DASS-21 questionnaire (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995). Exclusion criteria were age younger than 18, severe dysfunction, psychotic disorders, severe suicidality, and substance abuse disorder. In addition, patients were assessed for their suitability to short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy (Levenson, Citation2010). Patients were assigned to therapists based on scheduling and availability.

Therapists

Forty-eight therapists participated in the study (19 male and 29 female) between the ages of 23 and 52 (mean age 29.7, SD = 4.5). Therapists were clinical psychology graduate students and advanced interns, and one clinical social worker. All therapists received weekly supervision meetings with the second author, a licensed clinical psychologist. Out of the 48 therapists participating in the study, 15 had more than one patient.

Therapy

The form of therapy studied was Supportive Expressive Short-Term Therapy (Luborsky, Citation1984). This 16-session treatment focuses on the patient's core conflictual relationship theme, which is based on childhood experiences repeated in the patient's current relationships and with the therapist.

Procedure

Patients in the study contacted our research center while actively looking for therapy. They all faced a situation of long waiting lists in the public sector, and learned about short-term therapy from ads in social media and referrals from clinics. Initially, they completed an online questionnaire, and then the research coordinator (a Ph.D. intern) conducted a short screening interview to assess their willingness to participate in the study and their global functioning. Patients whose questionnaires indicated moderate levels of depression and/or anxiety and who were willing and able to come to the clinic were invited for a clinical intake with a senior clinical psychologist. The senior clinical psychologist assessed their suitability for short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy. Those for whom this type of therapy was not recommended were referred to therapists in the community who had openings.

Treatment was conducted at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and was provided free of charge. Participants signed consent forms in which they agreed to have the sessions (audio-video or only audio) recorded and to complete questionnaires before and after treatment. Before beginning treatment, therapists and patients completed two questionnaires: the personality questionnaire and the attachment questionnaire. Additionally, prior to the beginning of each session, patients filled out a symptom questionnaire.

Sixty-three treatments lasted 16 sessions or more (17 or 18), eight treatments comprised fewer than 16 sessions, but had 10 sessions or more, and six treatments consisted of three to nine sessions. Three dyads with fewer than three sessions were excluded from analyses. Moreover, for two dyads, some data about their personality traits were missing and they were excluded from some of the analyses. The study receives research ethics committee by “The University Committee for the Use of Human Subjects in Research.”

Measures and Data Collection

Personality traits

The Big Five Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava, Citation1999) consists of 44 items measuring five main personality traits: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. The items were rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The BFI questionnaire was administered to both therapists and patients before the beginning of treatment. In this sample, the five personality scales had an average Cronbach's alpha of 0.78 with a range of 0.76–0.83 for patients, and average Cronbach's alpha of 0.86 with a range of 0.81–0.92 for the therapists.

Attachment style

The Experience in Close Relationship Questionnaire (ECR: Brennan et al., Citation1998) consists of 36 items divided into two main attachment styles: attachment anxiety style (18 items) and attachment avoidant style (18 items). Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The ECR questionnaire was administered to both therapists and patients before the beginning of treatment. The internal reliability level of the total ECR in this study was α = 0.89 and α = 0.86 for patients’ and therapists’ anxiety scales, respectively, and α = 0.89 and α = 0.89 for patients’ and therapists’ avoidant scales, respectively.

Outcome

Psychological dysfunction was assessed by the Outcome Questionnaire-45 (OQ-45; Lambert et al., Citation1996). This questionnaire assesses patients’ general level of distress based on three factors: subjective discomfort, interpersonal relations, and social role performance. The questionnaire consists of 45 items, each of which is rated on a scale from 0 to 4. The total score ranges from 0 to 180, with higher scores representing more severe symptoms. The internal reliability level of the total OQ score in the present study was α = 0.922. The clinical cutoff score is 63.

Patient change score

Change in symptoms was defined as each patient's change in the symptom questionnaire (i.e., OQ-45) score, considered the starting point. We made a simple regression model from the OQ symptoms score at the beginning of therapy to the final score of the patient in the last session. We then took the standard residual scores and used them as the dependent outcome variable, thereby ensuring the removal of all change that could be explained by the pre-therapy symptoms score (Dalecki & Willits, Citation1991). We considered the patient's score on OQ before the first session as the beginning score (nine missing OQ scores were completed with the patients before the second session).

Data Analysis

We used the polynomial regression version of the response surface analysis (RSA), following the steps outlined by Barranti et al. (Citation2017) and Shanock et al. (Citation2010) to examine the dyadic congruence (for a discussion of the problems associated with the previous use of difference scores as measures of similarity, see Edwards, Citation2001). RSA is an emerging technique that allows exploration of the combined effect of two predictor variables (i.e., therapist and patient) on one outcome variable. Analyses were performed using R version R-4.0.3 and the RSA package (version 0.10.4; Schönbrodt & Humberg, Citation2021). RSA retains information about the main effects and examines them in three-dimensional space. The x-axis serves as the patient axis, the y-axis as the therapist axis, and the z-axis as the outcome axis. The polynomial regression consists of five predictors, as performed in the following equation:

In this equation, Z is the dependent variable (i.e., therapy outcome scores), PS is the first predictor that presents patient scores, and TS is the second predictor that presents therapist scores. Thus, the therapy outcome is regressed on each of the two predictor variables (PS and TS), the interaction between the two predictors (TSXPS), and the squared terms for each of the two predictors (PS2 and TS2) (Shanock et al., Citation2010). Thus, we had six estimate coefficients in the equation: an intercept (b0), a linear (b1), and a quadratic (b3) effect of the patients, a linear (b2) and quadratic effect of the therapist (b5), and an interaction between the linear effects of therapist and patient (b4). We used the coefficients from the regression model to calculate test values for two slopes and two respective curvatures along the response surface: (

) the slope of the agreement line. This slope reveals if and how congruence in therapist and patient scores are associated with therapy outcome (

). (

) the curvature along the line of agreement. This curvature reveals whether the association given congruence in therapist and patient scores, and therapy outcome is quadratic (

). (

) the slope of the incongruence line. This slope reveals if and how incongruence in therapist and patient scores is associated with therapy outcome (

). (

) the curvature along the congruence line. This curvature shows whether the relationship between patient and therapist incongruence reports and therapy outcome is quadratic (

) (for more information, see Edwards & Parry, Citation1993; Shanock et al., Citation2010). We tested separate models using symptom change as the dependent variable for each hypothesis.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Before turning to our primary analysis of match or mismatch, we examined the mean-level differences between therapists and the patients on all variables of interest. The correlations between patients and therapists were low and insignificant, indicating two different constructs for each analysis. Due to the nested data structure in which the patients are nested within the therapists, we initially used multi-level models (MLM). Nevertheless, the likelihood ratio test (LRT) was not significant , thus indicating that therapist effect was insignificant to the outcome measure; the more parsimonious model was preferred. Data were centered before analysis was carried out (Edwards & Parry, Citation1993). Therapist and patient scores were centered around the mean of their group (i.e., patient scale around the patient mean, and therapist scale around the therapist mean). In all the analyses below, multicollinearity was checked and was sufficiently low (variance inflation factor [VIF] was smaller than 5 [Fox, Citation2015]).

Personality Traits

We used response surface analysis and polynomial regression to examine the relations between therapist and patient within-dyad combinations of personality traits and patient symptom change. shows the results of the polynomial regression models, while shows the response surface parameters. We looked at all five personality factors and analyzed 75 patient–therapist dyads:

Table I. Response surface for patients and therapist self-personality traits ratings and symptom change at end of therapy.

Table II. Response surface for patients and therapist attachment style and emotional regulation strategies and symptoms changed along the therapy.

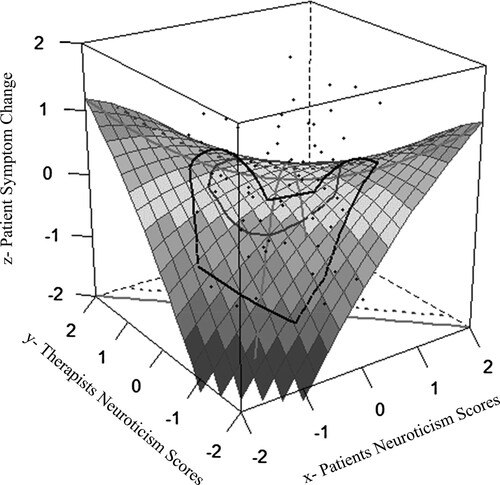

(1a) Neuroticism. Regarding the first part of our first hypothesis, we received a partially expected result. In the polynomial regression analysis, we examined the response surface analysis to assess the effects of patient and therapist match or mismatch in neuroticism. Based on previous research (Barranti et al., Citation2017), we found a significant negative curvature along the line of agreement ( = −0.30, p = 0.001), indicating that the quadric relation is significant (). That is, symptom severity decreased throughout therapy when therapist and patient and therapist combined pre-therapy neuroticism scores were at the low or high end of the combined scale, as shown in .

Figure 1. Patient and therapist congruence in neuroticism scores and therapy outcome. Note: Response surface displaying the association between patient and therapist neuroticism and symptoms changed throughout therapy. The x-axis is the patient’s self-reported neuroticism scores; the y-axis is the therapist’s self-reported neuroticism scores; and the z-axis is the symptom change with decrease in the score, meaning a decrease in symptoms. The line from the nearest to the farthest corner of the plane represents the line of agreement (i.e., patient score = therapist score). The farther the line, the higher the mutual scores are in neuroticism.

(1b) Extraversion, (1c) Openness to experience, (1d) Agreeableness. As shown in , none of the response surface analysis parameters showed a significant association within the patient–therapist similarity in extraversion, openness to experience, or agreeableness.

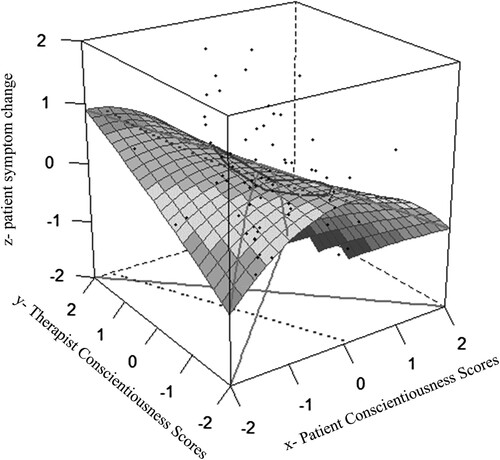

(1e) Conscientiousness. Regarding the fifth part of our first hypothesis, we received partially expected results. shows a significant negative slope along the line of agreement ( = −0.59, p = 0.01), and a significant negative effect for the curvature along the line of agreement (

= −0.55, p = 0.02). The linear and curvature effects of negatively significant parameters along the agreement line suggest that although symptom severity decreased as combined patient and therapist conscientiousness increased, the decrease in symptom severity was more pronounced at the high and low ends of the combined conscientiousness score ().

Figure 2. Patient and therapist congruence in conscientiousness scores and therapy outcome. Note: Response surface displaying the association between patient and therapist conscientiousness and symptoms changed throughout therapy. The x-axis is the patient’s self-reported conscientiousness scores; the y-axis is the therapist’s self-reported conscientiousness scores; and the z-axis is the symptom change with decrease in the score, meaning a decrease in symptoms. The line from the nearest to the farthest corner of the plane represents the line of agreement (i.e., patient score = therapist score). The farther the line, the higher the mutual scores are in conscientiousness.

Attachment style

To test the second hypothesis, we used response surface analysis and polynomial regression to examine the relations between therapist and patient within-dyad combinations of attachment styles and patient symptom change:

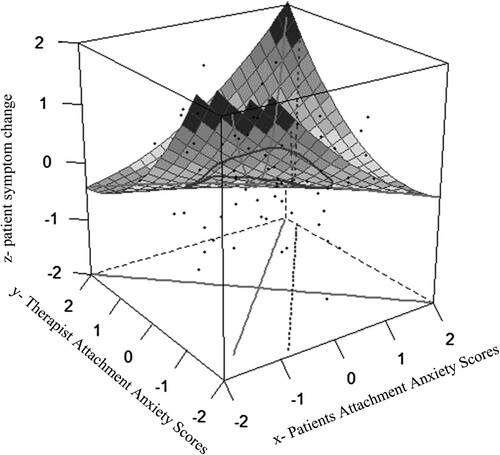

(2a) Anxiety Attachment. Based on previous research (Barranti et al., Citation2017), we examined the response surface analysis for patient–therapist attachment anxiety. We found a positive and significant association in the curvature along the line of agreement ( = 0.68, p < 0.001), indicating that the quadric relation is significant (). The significant positive quadric results suggest a reverse association at the lower and higher ends of the combined attachment anxiety scores. Thus, the more patient and therapist combined scores were at the higher or lower ends, the more symptoms increased throughout therapy. shows both the trend and the significant quadric relations.

Figure 3. Patient and therapist congruence in attachment anxiety scores and therapy outcome. Note: Response surface displaying the association between patient and therapist attachment anxiety and symptoms changed throughout therapy. The x-axis is the patient’s self-reported attachment anxiety scores; the y-axis is the therapist’s self-reported attachment anxiety scores; and the z-axis is the symptoms change with decrease in the score, meaning a decrease in symptoms. The line from the nearest to the farthest corner of the plane represents the line of agreement (i.e., patient score = therapist score). The farther the line, the higher the mutual scores are on attachment anxiety.

(2b) Attachment Avoidance. As shown in , none of the response surface analysis parameter were significant.

Discussion

This study examined the relationships between symptom change and pre-therapy match on patient and therapist personality traits and attachment styles. We used polynomial regression and response surface analysis to investigate these over the course of therapy.

In support of our first hypothesis (1a), we found a significant relationship between decrease in symptoms and patient–therapist match on two personality traits: neuroticism and conscientiousness. Regarding neuroticism, results show a curvature relation between neuroticism and a decrease in symptom severity. Thus, there is partial support for our hypothesis. While the combined scores were at the low end of neuroticism, the symptom decrease throughout therapy was greater. However, when the combined scores were at the high end, the symptom decrease throughout therapy was also greater. According to these results, a match on neuroticism is relevant to symptom change only when the combined scores are very high or very low. Neuroticism is known to be a negative trait that often correlates with mental disorders (Dash et al., Citation2019; Muris et al., Citation2005) and is generally associated with low scores on relationship measures (Malouff et al., Citation2010; White et al., Citation2004) and poor therapy outcome (Bucher et al., Citation2019). Thus, when combined scores were at the lower end, the therapy relationship was likely to be stronger, and therapy outcome better. Rodriguez and Anestis (Citation2023) in their study found that most therapists preferred patients who had high levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness and low levels of neuroticism. Surprisingly, our results showed symptom decrease also when the combined scores were at the high end. One possible explanation for this finding is related to the concept of responsiveness (Kramer & Stiles, Citation2015). Therefore, therapists who scored high on neuroticism may have been more responsive to their patients due to their familiarity with their own neuroticism. Moreover, these therapists may feel more comfortable with such patients, compared to therapists in Rodriguez and Anestis’s (Citation2023) study, who preferred not to treat high level, neurotic patients.

The combined scores of conscientiousness showed two significant effects. First, along the agreement line, we saw, in continuation of our hypothesis, that higher combined scores on conscientiousness predicted greater symptom decrease throughout therapy. Additionally, when the mutual scores were very high or low, the symptom decrease was more pronounced. Thus, better therapy outcomes (i.e., decrease in symptom severity) could be achieved either by a greater mutual conscientiousness or by both patient and therapist being very high or very low in conscientiousness. Conscientiousness is a trait that contributes to relationship satisfaction and therapy success (Bucher et al., Citation2019; Malouff et al., Citation2010; White et al., Citation2004). Moreover, conscientiousness is correlated with commitment (Syed et al., Citation2015), and commitment is one of the components of therapy alliance (Cullen et al., Citation2000). This can explain the positive effect that higher levels of conscientiousness had on therapy outcome.

Surprisingly, and contrary to our hypothesis, curvature effect also indicated an improvement in symptoms at a very low level of combined conscientiousness. If we consider conscientiousness a desirable trait, as shown in both the linear and the upper side of curvature effects, it seems puzzling that we see improvement at its lower levels. One line of thinking is related to the main domains that make up the trait of conscientiousness: orderliness and industriousness (Roberts et al., Citation2014). It is reasonable to assume that this is a trait where similarity affects the therapy relationship. When one partner in a dyad is orderly and industrious and the other is not, a clash is expectable, for example, when a patient is a few minutes late and the therapist becomes tense. However, when both are somewhat more flexible in this domain, they will get along more easily.

In contrast to the second, third, and fourth parts of our first hypothesis (1b, 1c, 1d), we did not find any relationship between symptom change (increase or decrease) and the remaining traits (extraversion, agreeableness, and openness to experience). Those traits usually correlated with better relationship measures and therapy success (Bucher et al., Citation2019; Malouff et al., Citation2010), although perhaps without the need for a match in the therapeutic dyad.

In regard to the first part of our second hypothesis (2a), we found a significant relationship between patient and therapist match on attachment anxiety and change in symptom severity. The positive significant curvature along the agreement line indicated that when patients and therapists were both either high or low on attachment anxiety, symptoms increased from the beginning of therapy to the end. Those results indicate a matching effect with less favorable results. Nevertheless, we did not see an opposing effect, as in previous studies (Marmarosh et al., Citation2014), which have shown that patients with high attachment anxiety have poor outcomes (Levy et al., Citation2011). It is possible that when both the patient and the therapist have high attachment anxiety, outcomes are hindered. Furthermore, attachment anxiety has been found to be associated with poor relationship abilities (Candel & Turliuc, Citation2019). It is also negatively related to patient rating of the working alliance (Bernecker et al., Citation2014). Accordingly, patients and therapists who scored high on attachment anxiety may find it difficult to form a secure alliance. Thus, our findings regarding patients and therapists who scored on the higher end of attachment anxiety are in line with previous research. However, the findings showing a relationship between patient–therapist low attachment anxiety scores and increased symptoms are surprising. One possible explanation is that low attachment anxiety might cause therapists to overlook ruptures that are related to patient-specific therapy focusing on relationship patterns. Marmarosh et al. (Citation2015) found that therapists with higher levels of attachment anxiety spent more effort in attending to ruptures during the session. Thus, it is possible that therapists with low attachment anxiety were less focused on ruptures. We also considered the possibility that patients who scored low on attachment anxiety also scored high on avoidant attachment style. However, this explanation was ruled out when we reanalyzed the data. Thus, our findings indicate that a better outcome is expected when the mutual attachment anxiety style is neither too high nor too low.

In regard to the second part of our second hypothesis (2b), patient and therapist match or mismatch on avoidant attachment style was not related to outcome, a finding that is not consistent with previous research. Unlike findings by Wiseman and Tishby (Citation2014), our results did not show a relationship between match in avoidant attachment style and outcome. We also did not find the difference effect (mismatch) that was found in Bucci et al. (Citation2016) for preoccupied and dismissing styles. Possible explanations for these differences are the type of therapy, the length of therapy, and diagnoses of the patients. For example, the sample in Wiseman and Tishby’s (Citation2014) study consisted of young adults in long-term psychodynamic therapy. In this type of therapy, deeper issues usually surface at later stages in therapy, whereas in our study, treatment lasted only 16 sessions. It is possible that the difficulties with avoidant attachment style patients were not as conspicuous in such a short time span, when the work mainly concerned conscious rather than unconscious issues.

Our findings indicate that matching in personality traits and attachment style is important for developing good therapeutic relations. These results are in line with studies of other types of relationships (Ilmarinen et al., Citation2017; Luo & Klohnen, Citation2005; O’Rourke et al., Citation2011; Selfhout et al., Citation2010), including therapeutic ones (Coleman, Citation2006; Taber et al., Citation2011). The study contributes to existing research by highlighting the issue of pre-therapy matching between the therapist and the patient.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations. First, the therapists in the study were graduate students and psychology interns. Although they all received weekly individual supervision, they conducted a rather demanding kind of therapy. Replication with more experienced therapists is recommended in order to enhance the generalizability of our current findings. In addition, our sample consisted of patients with moderate depression and/or anxiety, and thus our findings are not representative of a variety of diagnoses. Regarding the current analysis, along with its complexity, the results of the RSA could be interpreted in various ways (see Barranti et al., Citation2017; Humberg et al., Citation2019; Nestler et al., Citation2019; Shanock et al., Citation2010). In the current study, we interpreted the parameters of the RSA as isolated (Barranti et al., Citation2017; Shanock et al., Citation2010); following the restrictions imposed by Humberg et al. (Citation2019), we looked at the mutual score combination. In addition, we focused on only two patient–therapist characteristics: personality traits and attachment style. A promising avenue for future research could be investigating patient–therapist match in emotional regulation, interpersonal patterns, and many other areas. Lastly, because of the counter-intuitive nature of some of our findings, replication is advisable.

Implications for Clinical Practice

The results of this study might be applied to the process of assigning patients to therapists. Common practice in the field usually does not consider matching personality traits, although patients tend to do better with a matched therapist. Thus, personality and attachment could be identified in the intake appointment and be considered a factor in referring patients to specific therapists, along with experience, scheduling issues, and other factors. However, additional research and replications are needed in order to solidify this recommendation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.5 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atzil-Slonim, D., Bar-kalifa, E., Fisher, H., Peri, T., Lutz, W., Rubel, J., & Eshkol, R. (2018). Emotional congruence between clients and therapists and its effect on treatment outcome. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000250

- Barranti, M., Carlson, E. N., & Côté, S. (2017). How to test questions about similarity in personality and social psychology research: Description and empirical demonstration of response surface analysis. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617698204

- Bedair, K., Hamza, E. A., & Gladding, S. T. (2020). Attachment style, marital satisfaction, and mutual support attachment style in Qatar. Family Journal, 28(3), 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480720934377

- Bernecker, S. L., Levy, K. N., & Ellison, W. D. (2014). A meta-analysis of the relation between patient adult attachment style and the working alliance. Psychotherapy Research, 24(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.809561

- Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss: Vol 1. Attachment. Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

- Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson, & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). Guilford Press.

- Bucci, S., Seymour-Hyde, A., Harris, A., & Berry, K. (2016). Client and therapist attachment styles and working alliance: Attachment and working alliance. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 23(2), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1944

- Bucher, M. A., Suzuki, T., & Samuel, D. B. (2019). A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.04.002

- Candel, O. S., & Turliuc, M. N. (2019). Insecure attachment and relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis of actor and partner associations. Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.037

- Captari, L. E., Hook, J. N., Hoyt, W., Davis, D. E., McElroy-Heltzel, S. E., & Worthington, E. L. (2018). Integrating clients’ religion and spirituality within psychotherapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1938–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22681

- Castonguay, L. G., & Hill, C. E. (2017). Therapist effects: Integration and conclusions. In L. G. Castonguay, & C. E. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others? Understanding therapist effects (pp. 325–341). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000034-018

- Chui, H., Hill, C. E., Kline, K., Kuo, P., & Mohr, J. J. (2016). Are you in the mood? Therapist affect and psychotherapy process. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(4), 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000155

- Cobb-Clark, D. A., & Schurer, S. (2012). The stability of big-five personality traits. Economics Letters, 115(1), 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2011.11.015

- Coleman, D. (2006). Therapist-client five-factor personality similarity: A brief report. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 70(3), 232–241. https://doi.org/10.1521/bumc.2006.70.3.232

- Cologon, J., Schweitzer, R. D., King, R., & Nolte, T. (2017). Therapist reflective functioning, therapist attachment style and therapist effectiveness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 44(5), 614–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-017-0790-5

- Connolly Gibbons, M. B., Crits-Christoph, P., de la Cruz, C., Barber, J. P., Siqueland, L., & Gladis, M. (2003). Pretreatment expectations, interpersonal functioning, and symptoms in the prediction of the therapeutic alliance across supportive-expressive psychotherapy and cognitive therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 13(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptr/kpg007

- Cullen, J. B., Johnson, J. L., & Sakano, T. (2000). Success through commitment and trust: The soft side of strategic alliance management. Journal of World Business, 35(3), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(00)00036-5

- Dalecki, M., & Willits, F. K. (1991). Examining change using regression analysis: Three approaches compared. Sociological Spectrum, 11(2), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.1991.9981960

- Dash, G. F., Slutske, W. S., Martin, N. G., Statham, D. J., Agrawal, A., & Lynskey, M. T. (2019). Big five personality traits and alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and gambling disorder comorbidity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(4), 420. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000468

- Diener, M. J., Hilsenroth, M. J., & Weinberger, J. (2007). Therapist affect focus and patient outcomes in psychodynamic psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(6), 936–941. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.164.6.936

- Diener, M. J., & Monroe, J. M. (2011). The relationship between adult attachment style and therapeutic alliance in individual psychotherapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy, 48(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022425

- Digman, J. M., & Inouye, J. (1986). Personality processes and individual further specification of the five robust factors of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(1), 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.50.1.116

- Edwards, J. R. (2001). Ten difference score myths. Organizational Research Methods, 4(3), 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810143005

- Edwards, J. R., & Parry, M. E. (1993). On the use of polynomial regression equations as an alternative to difference scores in organizational research. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1577–1613. https://doi.org/10.2307/256822

- Ferguson, S. L., & Hull, D. M. (2018). Personality profiles: Using latent profile analysis to model personality typologies. Personality and Individual Differences, 122, 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.029

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., & Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000172

- Fox, J. Jr. (2015). Applied regression analysis and generalized linear models (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. Incorporated.

- Humberg, S., Nestler, S., & Back, M. D. (2019). Response surface analysis in personality and social psychology: Checklist and clarifications for the case of congruence hypotheses. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 10(3), 409–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550618757600

- Ilmarinen, V. J., Vainikainen, M. P., Verkasalo, M. J., & Lönnqvist, J. E. (2017). Homophilous friendship assortment based on personality traits and cognitive ability in middle childhood: The moderating effect of peer network size. European Journal of Personality, 31(3), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2095

- Jennissen, S., Nikendei, C., Ehrenthal, J. C., Schauenburg, H., & Dinger, U. (2020). Influence of patient and therapist agreement and disagreement about their alliance on symptom severity over the course of treatment: A response surface analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(3), 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000398

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S.. (1999). The Big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 102–138). Guilford Press.

- Jones, J. D., Fraley, R. C., Ehrlich, K. B., Stern, J. A., Lejuez, C. W., Shaver, P. R., & Cassidy, J. (2018). Stability of attachment style in adolescence: An empirical test of alternative developmental processes. Child Development, 89(3), 871–880. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12775

- Kim, D. M., Wampold, B. E., & Bolt, D. M. (2006). Therapist effects in psychotherapy: A random-effects modeling of the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program data. Psychotherapy Research, 16(02), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300500264911

- Kivlighan, D. M., & Marmarosh, C. L. (2018). Counselors’ attachment anxiety and avoidance and the congruence in clients’ and therapists’ working alliance ratings. Psychotherapy Research, 28(4), 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1198875

- Knoke, J., Burau, J., & Roehrle, B. (2010). Attachment styles, loneliness, quality, and stability of marital relationships. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 51(5), 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502551003652017

- Koorevaar, A. M. L., Comijs, H. C., Dhondt, A. D. F., van Marwijk, H. W. J., van der Mast, R. C., Naarding, P., Voshaar, R. C. O., & Stek, M. L. (2013). Big Five personality and depression diagnosis, severity and age of onset in older adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(1), 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.075

- Kramer, U., & Stiles, W. B. (2015). The responsiveness problem in psychotherapy: A review of proposed solutions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 22(3), 277. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12107

- Lambert, M. J., Burlingame, G. M., Umphress, V., Hansen, N. B., Vermeersch, D. A., Clouse, G. C., & Yanchar, S. C. (1996). The reliability and validity of the Outcome Questionnaire. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory and Practice, 3(4), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199612)3:4<249::AID-CPP106>3.0.CO;2-S

- Leikas, S., Ilmarinen, V. J., Verkasalo, M., Vartiainen, H. L., & Lönnqvist, J. E. (2018). Relationship satisfaction and similarity of personality traits, personal values, and attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences, 123, 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.024

- Levenson, H. (2010). Time-limited dynamic psychotherapy. In L. M. Horowitz & S. Strack (Eds.), Handbook of interpersonal psychology: Theory, research, assessment, and therapeutic interventions (pp. 545–563). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118001868.ch32.

- Levy, K. N., Ellison, W. D., Scott, L. N., & Bernecker, S. L. (2011). Attachment style. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 193–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof

- Levy, K. N., Kivity, Y., Johnson, B. N., & Gooch, C. V. (2018). Adult attachment as a predictor and moderator of psychotherapy outcome: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1996–2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22685

- Lewis, E. G., & Cardwell, J. M. (2020). The big five personality traits, perfectionism and their association with mental health among UK students on professional degree programmes. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00423-3

- Lingiardi, V., Muzi, L., Tanzilli, A., & Carone, N. (2018). Do therapists’ subjective variables impact on psychodynamic psychotherapy outcomes? A systematic literature review. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 25(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2131

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behavior Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Luborsky, L. (1984). Principles of psychoanalytic psychotherapy. A manual for supportive expressive treatment. Basic Books.

- Luo, S., & Klohnen, E. C. (2005). Assortative mating and marital quality in newlyweds: A couple-centered approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(2), 304–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.2.304

- Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Schutte, N. S., Bhullar, N., & Rooke, S. E. (2010). The Five-Factor Model of personality and relationship satisfaction of intimate partners: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 44(1), 124–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.09.004

- Marmarosh, C. L., Kivlighan, D. M., Bieri, K., LaFauci Schutt, J. M., Barone, C., & Choi, J. (2014). The insecure psychotherapy base: Using client and therapist attachment styles to understand the early alliance. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 404–412. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031989

- Marmarosh, C. L., Schmidt, E., Pembleton, J., Rotbart, E., Muzyk, N., Liner, A., Reid, L., Margolies, A., Joseph, M., & Salmen, K. (2015). Novice therapist attachment and perceived ruptures and repairs: A pilot study. Psychotherapy, 52(1), 140–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036129

- McCarthy, K. S., Gibbons, M. B. C., & Barber, J. P. (2008). The relation of rigidity across relationships with symptoms and functioning: An investigation with the revised central relationship questionnaire. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(3), 346–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012578

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.81

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. Guilford Press.

- Miller-Bottome, M., Talia, A., Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2018). Resolving alliance ruptures from an attachment-informed perspective. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 35(2), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/pap0000152

- Mohammadi, K., Samavi, A., & Ghazavi, Z. (2016). The relationship between attachment styles and lifestyle with marital satisfaction. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 18(4), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.23839

- Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. S., & Kirchner, J. (2008). Is actual similarity necessary for attraction? A meta-analysis of actual and perceived similarity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(6), 889–922. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508096700

- Muris, P., Roelofs, J., Rassin, E., Franken, I., & Mayer, B. (2005). Mediating effects of rumination and worry on the links between neuroticism, anxiety, and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(6), 1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.04.005

- Nestler, S., Humberg, S., & Schönbrodt, F. D. (2019). Response surface analysis with multilevel data: Illustration for the case of congruence hypotheses. Psychological Methods, 24(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000199

- Noftle, E. E., & Shaver, P. R. (2006). Attachment dimensions and the big five personality traits: Associations and comparative ability to predict relationship quality. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(2), 179–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2004.11.003

- Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2011). What works for whom: Tailoring psychotherapy to the person. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 127–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20764

- O’Brien, T. B., & DeLongis, A. (1996). The interactional context of problem-, emotion-, and relationship-focused coping: The role of the Big five personality factors. Journal of Personality, 64(4), 775–813. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00944.x

- O’Connor, S., Kivlighan Jr, D. M., Hill, C. E., & Gelso, C. J. (2019). Therapist – client agreement about their working alliance: Associations with attachment styles. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000303

- O’Rourke, N., Claxton, A., Chou, P. H. B., Smith, J. Z., & Hadjistavropoulos, T. (2011). Personality trait levels within older couples and between-spouse trait differences as predictors of marital satisfaction. Aging and Mental Health, 15(3), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.519324

- Oshio, A., Taku, K., Hirano, M., & Saeed, G. (2018). Resilience and Big Five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.048

- Pérez-Rojas, A. E., Bhatia, A., & Kivlighan, D. M. (2021). Do birds of a feather flock together? Clients’. Perceived personality similarity, real relationship, and treatment progress. Psychotherapy, 58(3), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000361

- Roberts, B. W., Lejuez, C., Krueger, R. F., Richards, J. M., & Hill, P. L. (2014). What is conscientiousness and how can it be assessed? Developmental Psychology, 50(5), 1315–1330. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031109

- Robins, R. W., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2000). Two personalities, one relationship: Both partners’ personality traits shape the quality of their relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(2), 251. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.2.251

- Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., Schwartz, S. H., & Knafo, A. (2002). The big five personality factors and personal values. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(6), 789–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202289008

- Rodriguez, T. R., & Anestis, J. C. (2023). An initial examination of mental healthcare providers’ Big 5 personality and their preferences for clients. Psychological Studies, 68(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-022-00700-8

- Rubel, J. A., Bar-Kalifa, E., Atzil-Slonim, D., Schmidt, S., & Lutz, W. (2018). Congruence of therapeutic bond perceptions and its relation to treatment outcome: Within-and between-dyad effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(4), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000280

- Schönbrodt, F., & Humberg, S. (2021). RSA: An R package for response surface analysis (version 0.10.4). https://cran.r-project.org/package = RSA.

- Selfhout, M., Burk, W., Branje, S., Denissen, J., van Aken, M., & Meeus, W. (2010). Emerging late adolescent friendship networks and Big Five personality traits: A social network approach. Journal of Personality, 78(2), 509–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00625.x

- Shanock, L. R., Baran, B. E., Gentry, W. A., Pattison, S. C., & Heggestad, E. D. (2010). Polynomial regression with response surface analysis: A powerful approach for examining moderation and overcoming limitations of difference scores. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(4), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9183-4

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(20), 22–33.

- Soma, C. S., Baucom, B. R. W., Xiao, B., Butner, J. E., Hilpert, P., Narayanan, S., Atkins, D. C., & Imel, Z. E. (2020). Coregulation of therapist and client emotion during psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 30(5), 591–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1661541

- Strauss, B. M., & Petrowski, K. (2017). The role of the therapist’s attachment in the process and outcome of psychotherapy. In L. G. Castonguay, & C. E. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others?: Understanding therapist effects (pp. 117–138). American Psychological Association.

- Syed, N., Saeed, A., & Farrukh, M. (2015). Organization commitment and five factor model of personality: Theory recapitulation. Journal of Asian Business Strategy, 5(8), 183–190. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.1006/2015.5.8/1006.8.183.190

- Taber, B. J., Leibert, T. W., & Agaskar, V. R. (2011). Relationships among client-therapist personality congruence, working alliance, and therapeutic outcome. Psychotherapy, 48(4), 376–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022066

- Tronick, E. Z. (2003). “Of course all relationships are unique”: How co-creative processes generate unique mother-infant and patient-therapist relationships and change other relationships. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 23(3), 473–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351692309349044

- Wampold, B. E., Baldwin, S. A., Holtforth, M., & Imel, Z. E. (2017). What characterizes effective therapists? In L. G. Castonguay, & C. E. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others?: Understanding therapist effects (pp. 37–53). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000034-003

- Wang, S., Kim, K., & Boerner, K. (2018). Personality similarity and marital quality among couples in later life. Personal Relationships, 25(4), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12260

- Werbart, A., Hägertz, M., & Borg Ölander, N. (2018). Matching patient and therapist anaclitic–introjective personality configurations matters for psychotherapy outcomes. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 48(4), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-018-9389-8

- White, J. K., Hendrick, S. S., & Hendrick, C. (2004). Big five personality variables and relationship constructs. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(7), 1519–1530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.02.019

- Wiseman, H., & Tishby, O. (2014). Client attachment, attachment to the therapist and client-therapist attachment match: How do they relate to change in psychodynamic psychotherapy? Psychotherapy Research, 24(3), 392–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2014.892646

- Zilcha-mano, S. (2017). Is the alliance really therapeutic? Revisiting this question in light of recent methodological advances. American Psychologist, 72(4), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040435