ABSTRACT

Objective

Behavioral activation (BA) is an extensively examined treatment for depression which is relatively simple to apply in comparison to other psychotherapies. BA aims to increase positive interactions between a person and the environment. All previous meta-analyses focused on BA in groups and guided self-help, but none focused on BA in individual psychotherapy. The goal of the current meta-analysis is to examine the pooled effects of trials comparing individual BA to control conditions.

Methods

We conducted systematic searches and conducted random effects meta-analyses to examine the effects of BA.

Results

We included 22 randomized controlled trials (with 819 patients) comparing individual behavioral activation with waitlist, usual care, or other control conditions on distal treatment outcomes. Nine studies were rated as low risk of bias. We found a large effect (Hedges’ g = 0.85; 95% CI: 0.57; 1.1) with high heterogeneity (75%; 95% CI: 62; 83). When only studies with low risk of bias were considered, the effect size was still significant (g = 0.56; 95% CI: 0.09; 1.03), with high heterogeneity (I2 = 80%; 95% CI: 66; 89; prediction interval: −0.85; 1.98).

Conclusion

BA is an effective, relatively simple type of therapy that can be applied broadly in differing populations/.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: Behavioral Activation (BA) is effective in the treatment of adult depression, with effect sizes that are comparable to those found for as other psychotherapies for depression, such as CBT and interpersonal psychotherapy. It can be used briefly in a few sessions as part of a more extensive treatment package, or more extensively as an independent treatment. BA is especially useful in more severe depression, when more insight-oriented therapies are not feasible, because it is a straightforward method. Accounting for personal preferences and cultural identities of the patient is important, because BA is flexible and can be adapted to the patients’ situation and needs.

Introduction

With about 280 million people suffering from depressive disorders, depression is the most prevalent mental disorder (World Health Organization, Citation2022). Furthermore, depression is known to be associated with considerable excess mortality and morbidity. Apart from the personal suffering by patients and their relatives, depression is also associated with huge economic costs. Because it affects people in their working age, the costs associated with production losses are especially high (Herrman et al., Citation2022). Depression is considered to be one of the main major public health challenges of the coming decades (World Health Organization, Citation2017).

Several psychological treatments are available for depression, which are usually considered to be first-line treatments. These include cognitive behavior therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, non-directive counseling, problem-solving therapy, psychodynamic therapy, and behavioral activation (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021). Behavioral activation (BA) is one of the best examined methods for treating depression. In this study we will mostly focus on BA as an independent treatment, and only briefly on treatment packages where BA is only one of the components.

BA can be briefly defined as a psychological method aimed at increasing positive interactions between a person and the environment (Cuijpers et al., Citation2020). A more extensive and precise definition was given in an authoritative review of the origins and current status of BA (Dimidjian et al., Citation2017, pp. 3–4): a “structured, brief psychotherapeutic approach that aims to (a) increase engagement in adaptive activities (which often are those associated with the experience of pleasure or mastery), (b) decrease engagement in activities that maintain depression or increase risk for depression, and (c) solve problems that limit access to reward or that maintain or increase aversive control.”

Four types of BA can be distinguished (Cuijpers et al., Citation2019; Mazzucchelli et al., Citation2009): (1) Pleasant activity (consisting of monitoring and scheduling pleasant activities, sometimes including social skills training; Lewinsohn, Citation1974); (2) Self-control (monitoring of activities and mood, goal setting, self-evaluation of performance and self-administering rewards; Rehm, Citation1984); (3) Contextual BA (activity scheduling, self-monitoring, graded task assignment, role playing, functional analysis, mental rehearsal and mindfulness; Jacobson et al., Citation2001; Martell et al., Citation2001); and (4) Behavioral activation treatment for depression (contracting to change immediate environmental contingencies, goal setting and graduated task assignment, monitoring, and self-administering rewards; Lejuez et al., Citation2001).

One of the most interesting aspects of BA is that it is relatively simple compared to full CBT. The basic idea of BA is that therapists help patients find which activities are related to a bettemood and then work to build more of these pleasant activities into the patients’ lives. This method does not require higher-level patterns of thoughts, which for many patients is quite complicated and an intensive learning process. Therapists do not need, therefore, necessarily to be fully trained psychotherapists or clinical psychologists. One seminal randomized trial conducted in the UK showed that BA delivered by nurses in primary care was not inferior to full CBT delivered by highly trained therapists (Richards et al., Citation2016).

Because BA is relatively easy for both therapists and patients, it has also been used with patients suffering from other disorders and more complicated population. These groups include caregivers of dementia patients (Teri et al., Citation1997), children with physical disabilities (Suh et al., Citation2021), adults with PTSD (Wagner et al., Citation2019), bereavement (Acierno et al., Citation2021), anxiety and depression in cancer survivors, concurrent methamphetamine dependence and sexual risk for HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men (Mimiaga et al., Citation2019), and as a preventive intervention in college students (Fazzino et al., Citation2020).

Although the effects of BA were examined in several randomized trials in the 1970s, all of these early studies were small and did not have sufficient statistical power to find small effects. Several later trials have proven important for the development of BA. The study by Jacobson et al. (Citation1996) was relatively large compared to the previous studies and found no indication that BA was less effective than CBT. Building on these results, another influential trial was conducted and again found no significant difference between BA and CBT, although BA was more effective with more severe depression (Dimidjian et al., Citation2006). A third significant trial conducted in the UK with 440 randomized patients showed that BA delivered by junior mental health workers in primary care was as effective as CBT delivered by psychotherapists (Richards et al., Citation2016).

Several recent meta-analyses have integrated the findings from randomized trials of BA as an independent treatment package on distal, end of treatment outcomes. The largest, most recent meta-analysis included 28 trials and found a pooled effect size (Hedges’ g) of 0.83 on depression, 0.37 on anxiety, and 0.64 on activation (Stein et al., Citation2021). Although the quality of most of the trials was modest, this meta-analysis suggested that BA is an effective treatment for depression as well as other outcomes.

A larger network meta-analysis included 331 RCTs comparing eight major types of psychotherapy for depression with each other or with control groups (waitlist, usual care, pill placebo) on distal, end of treatment outcomes (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021). A total of 36 trials included a BA treatment arm. No significant difference was found between BA and other major types of therapy such as CBT and Interpersonal Psychotherapy. A more specific, but smaller network meta-analysis included studies that compared treatments including BA (as independent treatment package), cognitive restructuring (CR), or the combination of BA and CR for depression, with each other or with waitlist or usual care (Ciharova et al., Citation2021). This meta-analysis suggested that all three had comparable effects on depression, and no significant outcome differences were found.

In recent years, several smaller meta-analytic studies of treatments including BA have been conducted. Most of these meta-analyses focused on specific target groups, such as older adults (Orgeta et al., Citation2017), young people (Tindall et al., Citation2017), and dementia and informal caregivers (Zabihi et al., Citation2020). Other meta-analyses focused on specific treatment formats of BA, including internet-based BA (Huguet et al., Citation2018) and group BA (Simmonds-Buckley et al., Citation2019). Another recent meta-analysis focused on BA for patients with co-occurring depression and substance use disorders (Pott et al., Citation2022). The number of randomized trials included in these narrower meta-analyses was relatively small, but most found moderate to large effects when comparing BA to usual care or waitlist control groups and confirmed the results of the larger (network) meta-analyses (although the effects in co-occurring depression and substance use disorders were small and non-significant; Pott et al., Citation2022).

All of the previous meta-analyses focused on BA in groups and guided self-help, but none focused on BA in individual psychotherapy. We decided therefore to conduct a meta-analysis of individual BA on distal, end of treatment outcomes in adult depression.

Method

Identification and Selection of Studies

The current study is part of a larger meta-analytic project on psychological treatments of depression that was registered at the Open Science Framework (Cuijpers & Karyotaki, Citation2020). Supplemental materials are available at the project’s website (www.metapsy.org). This database has been used in a series of earlier published meta-analyses (Cuijpers, Citation2017).

The studies included in the current review were identified through the larger, already existing database of randomized trials on the psychological treatment of depression. For this database we searched four major bibliographical databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, Embase, Cochrane Library) by combining terms (both index terms and text words) indicative of depression and psychotherapies, with filters for randomized controlled trials. The full search strings can be found at the website (www.metapsy.org). Further, we checked the references of earlier meta-analyses on psychological treatments of depression. The database is continuously updated and was developed through a comprehensive literature search (from 1966 to 1 January 2022). All records were screened by two independent researchers, and all papers that could possibly meet inclusion criteria according to one of the researchers were retrieved as full-text. The decision to include or exclude a study in the database was also done by the two independent researchers, and disagreements were resolved through discussion.

For this meta-analysis, we included randomized controlled trials in which BA in an individual format for adults with depression were compared with a control condition (waitlist, care-as-usual, other non-active control groups). We operationalized BA as an intervention in which the registration of pleasant activities and the increase of positive interactions between a person and his or her environment were the core elements of the treatment (Cuijpers et al., Citation2020). Social skills training could be a part of the intervention. Cognitive behavioral interventions in which also other components, such as cognitive restructuring were included, were not included in this meta-analysis. Depression could be defined as meeting criteria for a depressive disorder according to a diagnostic interview or as a score above the cut-off on a self-report depression measure.

Quality Assessment and Data Extraction

We assessed the validity of included studies using four criteria of the Risk of Bias (RoB) assessment tool (version 1, developed by Cochrane Collaboration; Higgins et al., Citation2011). The RoB tool assesses possible sources of bias in randomized trials including: the adequate generation of allocation sequence; the concealment of allocation to conditions; the prevention of knowledge of the allocated intervention (masking of assessors); and dealing with incomplete outcome data (this was assessed as positive when intention-to-treat analyses were conducted, meaning that all randomized patients were included in the analyses). Assessment of the validity of the included studies was conducted by two independent researchers, and disagreements were solved through discussion.

We coded participant characteristics (diagnostic method; recruitment method; target group; mean age; proportion of women); characteristics of BA (number of sessions) as well as general characteristics of the studies (type of control group; publication year; country). Extended definitions of the moderators are available at the website of the meta-analytic project from which these meta-analytic data were drawn (www.metapsy.org). Because we have collected these data over a period of 15 years and because the number of trials in our database is very large (currently more than 900 RCTs), reliabilities across different raters have not been collected.

Outcome Measures

For each comparison between BA and a control condition, the effect size indicating the difference between the two groups at post-test in terms of distal outcomes (depressive symptoms) was calculated (Hedges’ g; Hedges & Olkin, Citation1985). Effect sizes were calculated by subtracting (at post-test) the average score of the BA group from the average score of the control group and dividing the result by the pooled standard deviation. Because some studies had relatively small sample sizes, we corrected the effect size for small sample bias. When means and standard deviations were not reported we calculated the effect size using dichotomous outcomes; and if these were not available either, we used other statistics (such as t-value or p-value) to calculate the effect size.

Meta-Analyses

The meta-analyses were conducted with the meta and metafor packages in R (version 4.1.1) and R studio (version 1.1.463 for Mac). The “metapsyTools” package (Harrer et al., Citation2022) was specifically developed for the meta-analytic project of which this study is a part. We calculated the pooled effect sizes in several different ways so that we could explore if different methods of pooling outcomes resulted in different outcomes. We pooled all outcomes within a study, before pooling across studies. To pool effect sizes within studies, an intra-study correlation coefficient of ρ = 0.5 was assumed. This method of pooling the effect sizes was the main method of analyses.

In addition to these main analyses, we also calculated the pooled effect size in several different ways to ensure that all methods of pooling pointed in the same direction: (2) We also calculated the pooled effect size based on a multilevel (three-level) model (effect sizes nested in studies), using the three-level “correlated and hierarchical effects” (CHE) model, which was recently proposed by Pustejovsky and Tipton (Citation2022); parameter tests and confidence intervals of which are also calculated using RVE to guard against model misspecification. We assumed an intra-study correlation of ρ = 0.5 for this model. (3) Then we calculated the pooled effect size with the smallest outcome per study and (4) the pooled effect size with the largest outcome per study. (5) The pooled effect size while excluding outliers, using the “non-overlapping confidence intervals” approach, in which a study is defined as an outlier when the 95% CI of the effect size does not overlap with the 95% CI of the pooled effect size (Harrer et al., Citation2022). (6) The pooled effect size with influential cases excluded according to the methods developed by Viechtbauer and Cheung (Citation2010). (7) The pooled effect size adjusted for publication bias, using Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure (Duval & Tweedie, Citation2000), which yields an estimate of the effect size after correction for the funnel plot asymmetry. (8) The pooled effect size from studies with low risk of bias. (9) In addition, as another sensitivity analysis, we calculated the pooled effect size under the assumption that all effect sizes are independent. Random effects models were conducted in which the between-study heterogeneity variance was estimated using the restricted maximum likelihood method. We applied the Knapp-Hartung method to obtain robust confidence intervals and significance tests of the overall effect (IntHout et al., Citation2014). As a test of homogeneity of effect sizes, we calculated the I2-statistic and its 95% confidence interval, which is an indicator of heterogeneity in percentages, with 0% indicating no observed heterogeneity, 25% low, 50% moderate, and 75% high heterogeneity (Higgins et al., Citation2003). Because I2 cannot be interpreted as an absolute measure of the between-study heterogeneity, we also added the prediction interval which indicates the range in which the true effect size of 95% of all populations will fall (Borenstein et al., Citation2009, Citation2017). In addition to Hedges’ g, we also calculated the Numbers-needed-to-treat (NNT; Furukawa, Citation1999), in which the control group’s event rate was set at a conservative 17% (based on the pooled response rate of 50% symptom reduction across trials in psychotherapy for depression; Cuijpers et al., Citation2021).

In addition to calculating the effect size after adjustment for publication bias trim and fill procedure, we tested for publication bias by inspecting the funnel plot on primary outcome measures and by Egger’s test of the intercept to quantify the bias captured by the funnel plot and to test whether it was significant.

Because the number of included studies was low and subgroup analyses usually have low statistical power (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021), we conducted only a small number of subgroup analyses that we considered essential: Type of control group, diagnosed mood disorder versus a cut-off on a self-report measure, recruitment method, adults in general versus a more specific target group, and risk of bias (low versus other).

Results

Selection and Inclusion of Studies

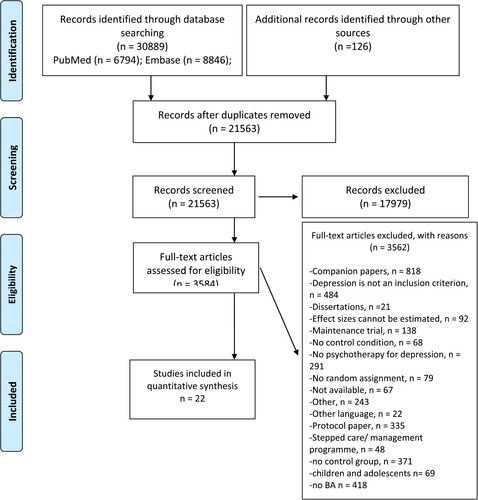

After examining a total of 30,889 records (21,563 after removal of duplicates), we retrieved 3,584 full-text papers for further consideration. We excluded 3563 of the retrieved papers. The PRISMA flowchart describing the inclusion process, including the reasons for exclusion, is presented in . A total of 22 randomized controlled trials with 819 patients (399 in the BA conditions and 420 in the control conditions) met inclusion criteria.

Characteristics of Included Studies

A summary of key characteristics of the 22 included studies is presented in . In 7 trials participants met criteria for a depressive disorder according to a diagnostic interview, while the other 15 trials included participants who scored above a cut-off on a self-report depression scale. In 14 studies, usual care was used as control group, 5 used a waitlist control group and the 3 remaining studies used another control group (placebo, brief non-specific support, life style advice). Ten studies were conducted in the USA, 6 in Europe, and 6 in other countries. The number of sessions ranged from 1 to 24, with the majority (18 interventions) between 4 and 12 sessions.

Table 1. Selected characteristics of randomised trials comparing individual behavioral activation to control groups.

Sixteen of the 22 studies reported that the random numbers were generated correctly (adequate sequence generation; 73%); 11 reported allocation to conditions by an independent party (50%); 4 reported using blinded outcome assessors (18%) while 14 used only self-report outcomes (64%). In 17 studies, intent-to-treat analyses were conducted (77%). Nine studies (41%) met all criteria for low risk of bias, 9 other studies (41%) met 2 or 3 criteria, and 4 met only one criterion (18%).

Distal Outcomes for Individual BA on Depression

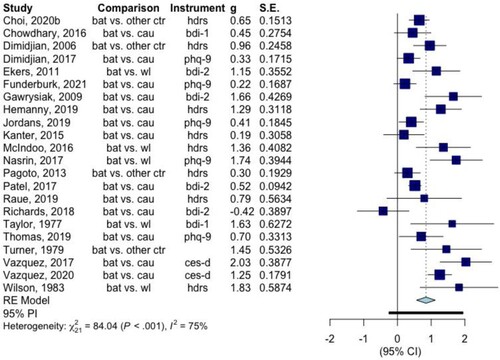

The results of the meta-analysis according to the different models are presented in . The forest plot is given in . The main analyses indicated a large effect of BA on depression compared with control groups. Hedges’ g was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.57; 1.1), which corresponds to an NNT of 3.48. Heterogeneity was high (75%; 95% CI: 62; 83), and the prediction interval was broad (−0.25; 1.94).

Figure 2. Forest plot a) Abbreviations: bat: behavioral activation therapy; cau: care-as-usual; ctr: control; g: Hedges’ g; S.E.: standard error; vs: versus; wl: waiting list.

Table 2. The effects of individual Behavioral activation for depression according to different models.

The majority of the other models indicated comparable pooled outcomes for BA, with only small differences from the main model. The overall outcomes of individual BA on distal, end-of-treatment outcomes were robust. However, the effect size was considerably smaller when only studies with low risk of bias were considered, although the effect size was still significant (g = 0.56; 95% CI: 0.09; 1.03). Heterogeneity was still high in these analyses (I2 = 80%; 95% CI: 66; 89; prediction interval: −0.85; 1.98). Excluding outliers and influential cases did not reduce heterogeneity much.

We also found significant indications for publication bias. Egger’s test was significant (p = 0.02), and the effect size was considerably reduced after adjusting through trim and fill procedure (g = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.29; 0.92). Heterogeneity was still high after this adjustment (I2 = 79%; 95% CI: 70; 85; prediction interval: −0.85; 2.06).

The results of the subgroup analyses are reported in . We found a significant difference between studies using different types of control groups (p < 0.001). Studies that used a waitlist control had a considerably larger effect size than studies using usual care or other groups. The other subgroup analyses examined the type of control group, diagnosis (mood disorder versus scoring above a cut-off), recruitment, target group, and risk of bias. None of these analyses pointed at significant differences between subgroups.

Table 3. Subgroup analyses.

Discussion

This meta-analysis shows that individual BA has significant end-of-treatment effects on depression. Although these effects may be somewhat overestimated because of publication bias and the suboptimal quality of several trials, the effects are still statistically significant and clinically meaningful after adjusting for these problems. The type of control group also affected the effect size, with waiting lists possibly overestimating the actual effects, which is in line with previous research on psychotherapies for depression (Furukawa et al., Citation2014; Cuijpers et al., Citation2021). However, several sensitivity analyses indicated that the effects found for BA are robust.

Few studies have focused on in-session outcomes of BA. One randomised trial indicated that 66% of patients receiving BA responded (their BDI score after treatment was at least 50% lower compared to baseline), whereas this proportion was 45% in the control group (Pagoto et al., Citation2013). Other trials have rarely reported response and remission rates of BA. Several studies did find high completion rates, treatment fidelity and treatment satisfaction (Funderburk et al., Citation2021; Gros et al., Citation2019).

In a study examining in-session outcomes of BA (Santos et al., Citation2017), it was found that in 79% of the patients participating in BA, changes in activation preceded or co-occurred with changes in depression, whereas this was not the case in patients receiving usual care. In another study among women with postpartum depression, it was found that sudden gains predicted lower depression scores after treatment (O'Mahen et al., Citation2017) and that participants with higher social functioning at baseline, did not experience a stressful life event during therapy, and completed more online modules were more likely to have a sudden gain. Sudden gains were defined as a large and stable drop in symptoms from one session to the next, and typically occurring early in treatment (Tang & DeRubeis, Citation1999). It was also found in this study that therapists focussed on specific, concrete content more in the session preceding the sudden gain than in the yoked sessions with women who did not have sudden gains. However, a more concrete therapist focus was only associated with having a sudden gain, not with the outcome on depressive symptoms at post-test. In another study of BA it was found that enactment of activities was significantly related to the likelihood of remission at post-treatment, and of maintaining improvement at 3-month follow-up (Meeks et al., Citation2019). More research is clearly needed to understand in-session processes and outcomes of BA.

Unfortunately, potential negative effects of BA have hardly been examined. Some of the trials in our meta-analysis report negative effects in patients receiving BA. Ekers et al. (Citation2011) reported that none of the patients receiving BA deteriorated, whereas 16% in usual care deteriorated. In another study (Funderburk et al., Citation2021), the symptoms worsened in 10% of participants receiving BA, whereas 7% worsened in the control group. Other studies also reported serious adverse events (Patel et al., Citation2017; Raue et al., Citation2019; Richards et al., Citation2018; Thomas et al., Citation2019) but these numbers are very low (<5%) and in most cases not related to the treatment, such as hospital admissions, or equally divided across the treatment and control groups. Because of the small number of trials reporting negative effects, it is unfortunately not possible to make a reliable estimate of the proportion of patients who deteriorate during BA. Meta-analyses of psychotherapies in general show that this proportion is low and significantly smaller in treatment than in control conditions (Cuijpers et al., Citation2018, p. 2021).

The studies included in our meta-analysis varied considerably in terms of target samples. Only six of the 22 studies were aimed at adults in general, whereeas one study was specifically aimed at Latinos in the US (Kanter et al., Citation2015), one at veterans (Funderburk et al., Citation2021), one at women with obesity (Pagoto et al., Citation2013), two were aimed at older adults (Choi et al., Citation2020; Raue et al., Citation2019), two at college students (Gawrysiak et al., Citation2009; McIndoo et al., Citation2016), two at non-professional caregivers (Vázquez et al., Citation2017, Citation2020), and two at patients with comorbid general medical disorders (Richards et al., Citation2018; Thomas et al., Citation2019). While most studies were conducted in the US and Europe, four studies were conducted in low- and middle-income countries, two in India (Chowdhary et al., Citation2016; Patel et al., Citation2017), one in Nepal (Jordans et al., Citation2019) and one in Brasil (Hemanny et al., Citation2020). There were not enough studies in each of these specific groups to examine whether the effect sizes differed from those in other groups.

The number of trials examining the effects of individual BA is relatively small, and the quality of many of these trials is suboptimal. Although our meta-analysis indicated significant effects of individual BA treatment packages on distal outcomes, these results should be considered with caution because of the modest number and the low quality of these trials. However, overall individual BA is effective in the treatment of depression and previous research has shown that there are few indications that BA is less effective than other methods. We know that the entire BA treatment package works on distal outcomes, but we know little of its effects on immediate session or intermediate outcomes. Virtually all of the research conducted has focused on distal, end-of-treatment outcomes. It should be noted that this meta-analysis only focused on BA for depression. Future meta-analytic research should also focus on other mental health problems that can be treated with BA, as well as other outcomes next to depression.

We also do not we know which of the components of BA are responsible for its salutatory impact. The science has not made enough progress to say which of the components prove necessary. BA is often used as a stand-alone intervention for depression, but it is also often combined with cognitive restructuring and other components, such as problem-solving. It is not known what the relative contribution of BA is compared with other components of such broader cognitive behavioral packages. Research on working mechanisms and mediators of therapies has mostly been correlational and currently, no mechanism of BA or any other therapy or component has been sufficiently empirically validated (Cuijpers et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it is still unknown how therapies work. Additional research using additive or dismantling designs are probably necessary.

Author Note: This article is adapted, by special permission of Oxford University Press, from a chapter by the same authors in C. E. Hill & J. C. Norcross (Eds.) (2023), Psychotherapy skills and methods that work. The interorganizational Task Force on Psychotherapy Methods and Skills was cosponsored by the APA Division of Psychotherapy/Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

*indicates studies included in the meta-analysis.

- Acierno, R., Kauffman, B., Muzzy, W., Tejada, M. H., & Lejuez, C. (2021). Behavioral activation and therapeutic exposure vs. Cognitive therapy for grief Among combat veterans: A randomized clinical trial of bereavement interventions. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 38(12), 1470–1478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909121989021

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley.

- Borenstein, M., Higgins, J. P. T., Hedges, L. V., & Rothstein, H. R. (2017). Basics of meta-analysis:I2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Research Synthesis Methods, 8(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1230

- *Choi, N. G., Marti, C. N., Wilson, N. L., Chen, G. J., Sirrianni, L., Hegel, M. T., Bruce, M. B., & Kunik, M. E. (2020). Effect of telehealth treatment by Lay counselors vs by clinicians on depressive symptoms Among older adults Who Are homebound. JAMA Network Open, 3(8), e2015648. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.15648

- *Chowdhary, N., Anand, A., Dimidjian, S., Shinde, S., Weobong, B., Balaji, M., Hollon, S. D., Rahman, A., Wilson, G. T., Verdeli, H., Araya, R., King, M., Jordans, M. J. D., Fairburn, C., Kirkwood, B., & Patel, V. (2016). The healthy activity program lay counsellor delivered treatment for severe depression in India: Systematic development and randomised evaluation. British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(4), 381–388. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.161075

- Ciharova, M., Furukawa, T. A., Efthimiou, O., Karyotaki, E., Miguel, C., Noma, H., Cipriani, A., Riper, H., & Cuijpers, P. (2021). Cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of adult depression: A network meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(6), 563–574. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000654

- Cuijpers, P., Cristea, I. A., Karyotaki, E., Reijnders, M., & Hollon, S. D. (2019). Component studies of psychological treatments of adult depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 29(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1395922

- Cuijpers, P. (2017). Four decades of outcome research on psychotherapies for adult depression: An overview of a series of meta-analyses. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 58(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000096

- Cuijpers, P., & Karyotaki, E. (2020). A meta-analytic database of randomized trials on psychotherapies for depression. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/825C6

- Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., de Wit, L., & Ebert, D. D. (2020). The effects of fifteen evidence-supported therapies for adult depression: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy Research, 30(3), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1649732

- Cuijpers, P., Quero, S., Noma, H., Ciharova, M., Miguel, C., Karyotaki, E., Cipriani, A., Cristea, I., & Furukawa, T. A. (2021). Psychotherapies for depression: A network meta-analysis covering efficacy, acceptability and long-term outcomes of all main treatment types. World Psychiatry, 20(2), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20860

- Cuijpers, P., Reijnders, M., Karyotaki, E., de Wit, L., & Ebert, D. D. (2018). Negative effects of psychotherapies for adult depression: A meta-analysis of deterioration rates. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 138–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.050

- *Dimidjian, S., Goodman, S. H., Sherwood, N. E., Simon, G. E., Ludman, E., Gallop, R., Gallop, R., Welch, S. S., Boggs, J. M., Metcalf, C. A., Hubley, S., Powers, J. D., & Beck, A. (2017). A pragmatic randomized clinical trial of behavioral activation for depressed pregnant women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000151

- *Dimidjian, S., Hollon, S. D., Dobson, K. S., Schmaling, K. B., Kohlenberg, R. J., Addis, M. E., Gallop, R., McGlinchey, J. B., Markley, D. K., Gollan, J. K., Atkins, D. C., Dunner, D. L., & Jacobson, N. S. (2006). Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 658–670. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658

- Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

- *Ekers, D., Richards, D., McMillan, D., Bland, J. M., & Gilbody, S. (2011). Behavioural activation delivered by the non-specialist: Phase II randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 198(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.079111

- Fazzino, T. L., Lejuez, C. W., & Yi, R. (2020). A behavioral activation intervention administered in a 16-week freshman orientation course: Study protocol. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 90, 105950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2020.105950

- *Funderburk, J. S., Pigeon, W. R., Shepardson, R. L., Wadea, M., Ackera, J., Fivecoat, H., Wray, L. O., Maisto, S. A., Wade, M., & Acker, J. (2021). Treating depressive symptoms among veterans in primary care: A multi-site RCT of brief behavioral activation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 283, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.033

- Furukawa, T. A. (1999). From effect size into number needed to treat. The Lancet, 353(9165), 1680. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01163-0

- Furukawa, T. A., Noma, H., Caldwell, D. M., Honyashiki, M., Shinohara, K., Imai, H., Chen, P., Hunot, V., & Churchill, R. (2014). Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: A contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 130(3), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12275

- *Gawrysiak, M., Nicholas, C., & Hopko, D. R. (2009). Behavioral activation for moderately depressed university students: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(3), 468–475. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016383

- Gros, D. F., Oglesby, M. E., & Wray, J. M. (2019). An open trial of behavioral activation in veterans with major depressive disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 21(5), 26690.

- Harrer, M., Kuper, P., & Cuijpers, P. (2022). metapsyTools: Several R helper functions for the “metapsy” database. R package version 0.3.2, https://github.com/MathiasHarrer/metapsyTools.

- Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Academic Press.

- *Hemanny, C., Carvalho, C., Maia, N., Reis, D., Botelho, A. C., Bonavides, D., Seixas, C., & de Oliveira, I. R. (2020). Efficacy of trial-based cognitive therapy, behavioral activation and treatment as usual in the treatment of major depressive disorder: Preliminary findings from a randomized clinical trial. CNS Spectrums, 25(4), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852919001457

- Herrman, H., Patel, V., Kieling, C., Berk, M., Buchweitz, C., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T. A., Kessler, R. C., Kohrt, B. A., Maj, M., McGorry, P., Reynolds III, C. F., Weissman, M. M., Chibanda, D., Dowrick, C., Howard, L. M., Hoven, C. W., Knapp, M., Mayberg, H. S., …, Uher, R. (2022). Time for united action on depression: a Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Commission. Lancet, epub ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02141-3

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 327(7414), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

- Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., Gotzsche, P. C., Juni, P., Savovic, J., Schulz, K. F., Weeks, L., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2011). The cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343(oct18 2), d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

- Huguet, A., Miller, A., Kisely, S., Rao, S., Saadat, N., & McGrath, P. J. (2018). A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy of internet-delivered behavioral activation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 235, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.073

- IntHout J., Ioannidis J. P., & Borm G. F. (2014). The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14, 25.

- Jacobson, N. S., Dobson, K. S., Truax, P. A., Addis, M. E., Koerner, K., Gollan, J. K., Gortner, E., & Prince, S. E. (1996). A component analysis of cognitive–behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.295

- Jacobson, N. S., Martell, C. R., & Dimidjian, S. (2001). Behavioral activation treatment for depression: Returning to contextual roots. Clinical Psychologist, 8, 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.8.3.255

- *Jordans, M. J. D., Luitel, N. P., Garman, E., Kohrt, B. A., Rathod, S. D., Shrestha, P., Komproe, I. H., Lund, C., & Patel, V. (2019). Effectiveness of psychological treatments for depression and alcohol use disorder delivered by community-based counsellors: Two pragmatic randomised controlled trials within primary healthcare in Nepal. British Journal of Psychiatry, 215(2), 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.300

- *Kanter, J. W., Santiago-Rivera, A. L., Santos, M. M., Nagy, G., López, M., Hurtado, G. D., & West, P. (2015). A randomized hybrid efficacy and effectiveness trial of behavioral activation for latinos with depression. Behavior Therapy, 46(2), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.09.011

- Lejuez, C. W., Hopko, D. R., & Hopko, S. D. (2001). A brief behavioral activation treatment for depression. Behavior Modification, 25(2), 255–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445501252005

- Lewinsohn, P. M. (1974). A behavioral approach to depression. In R. J. Friedman, & M. M. Katz (Eds.), The psychology of depression: Contemporary theory and research (pp. 157–185). Winston-Wiley.

- Martell, C. R., Addis, M. E., & Jacobson, N. S. (2001). Depression in context: Strategies for guided action. W. W. Norton.

- Mazzucchelli, T., Kane, R., & Rees, C. (2009). Behavioral activation treatments for depression in adults: A meta-analysis and review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 16(4), 383–411. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01178.x

- *McIndoo, C. C., File, A. A., Preddy, T., Clark, C. G., & Hopko, D. R. (2016). Mindfulness-based therapy and behavioral activation: A randomized controlled trial with depressed college students. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.012

- Meeks, S., Van Haitsma, K., & Shryock, S. K. (2019). Treatment fidelity evidence for BE-ACTIV - a behavioral intervention for depression in nursing homes. Aging & Mental Health, 23(9), 1192–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1484888

- Mimiaga, M. J., Pantalone, D. W., Biello, K. B., White Hughto, J. M., Frank, J., O'Cleirigh, C., Reisner, S. L., Restar, A., Mayer, K. H., & Safren, S. A. (2019). An initial randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation for treatment of concurrent crystal methamphetamine dependence and sexual risk for HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men. AIDS Care, 31(9), 1083–1095. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1595518

- *Nasrin, F., Rimes, K., Reinecke, A., Rinck, M., & Barnhofer, T. (2017). Effects of brief behavioural activation on approach and avoidance tendencies in acute depression: Preliminary findings. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 45(1), 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465816000394

- O'Mahen, H. A., Wilkinson, E., Bagnall, K., Richards, D. A., & Swales, A. (2017). Shape of change in internet based behavioral activation treatment for depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 95, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.011

- Orgeta, V., Brede, J., & Livingston, G. (2017). Behavioural activation for depression in older people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 211(5), 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.117.205021

- *Pagoto, S., Schneider, K. L., Whited, M. C., Oleski, J. L., Merriam, P., Appelhans, B., Ma, Y., Olendzki, B., Waring, M. E., Busch, A. M., Lemon, S., Ockene, I., & Crawford, S. (2013). Randomized controlled trial of behavioral treatment for comorbid obesity and depression in women: The Be active trial. International Journal of Obesity, 37(11), 1427–1434. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.25

- *Patel, V., Weobong, B., Weiss, H., Anand, A., Bhat, B., Katti, B., Dimidjian, S., Araya, R., Hollon, S. D., King, M., Vijayakumar, L., Park, A.-L., McDaid, D., Wilson, T., Velleman, R., Kirkwood, B. R., & Fairburn, C. G. (2017). The healthy activity program (HAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for severe depression, in primary care in India: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 389(10065), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31589-6

- Pott, S. L., Delgadillo, J., & Kellett, S. (2022). Is behavioral activation an effective and acceptable treatment for co-occurring depression and substance use disorders? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 132, 108478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108478

- Pustejovsky, J. E., & Tipton, E. (2022). Meta-analysis with robust variance estimation: Expanding the range of working models. Prevention Science, 23(3), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01246-3

- *Raue, P. J., Sirey, J. A., Dawson, A., Berman, J., & Bruce, M. L. (2019). Lay-delivered behavioral activation for depressed senior center clients: Pilot RCT. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(11), 1715–1723. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5186

- Rehm, L. P. (1984). Self-management therapy for depression. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 6(2), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(84)90004-3

- Richards, D. A., Ekers, D., McMillan, D., Taylor, R. S., Byford, S., Warren, F. C., Barrett, B., Farrand, P. A., Gilbody, S., Kuyken, W., O'Mahen, H., Watkins, E. R., Wright, K. A., Hollon, S. D., Reed, N., Rhodes, S., Fletcher, E., & Finning, K. (2016). Cost and outcome of behavioural activation versus cognitive behavioural therapy for depression (COBRA): A randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet, 388(10047), 871–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31140-0

- *Richards, S. H., Dickens, C., Anderson, R., Richards, D. A., Taylor, R. S., Ukoumunne, O. C., Kessler, D., Turner, K., Kuyken, W., Gandhi, M., Knight, L., Gibson, A., Davey, A., Warren, F., Winder, R., Wright, C., & Campbell, J. (2018). Assessing the effectiveness of enhanced psychological care for patients with depressive symptoms attending cardiac rehabilitation compared with treatment as usual (CADENCE): study protocol for a pilot cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials, 17(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1184-9

- Santos, M. M., Rae, J. R., Nagy, G. A., Manbeck, K. E., Hurtado, G. D., West, P., Santiago-Rivera, A., & Kanter, J. W. (2017). A client-level session-by-session evaluation of behavioral activation's mechanism of action. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 54, 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.07.003. Epub 2016 Jul 7.

- Simmonds-Buckley, M., Kellett, S., & Waller, G. (2019). Acceptability and efficacy of group behavioral activation for depression Among adults: A meta-analysis. Behavior Therapy, 50(5), 864–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.01.003

- Stein, A. T., Carl, E., Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., & Smits, J. A. J. (2021). Looking beyond depression: A meta-analysis of the effect of behavioral activation on depression, anxiety, and activation. Psychological Medicine, 51(9), 1491–1504. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720000239

- Suh, J. W., Lee, E. B., Han, Y., Lee, M. G., & Choi, K. H. (2021). The effects of brief behavioral activation (BA) on children with physical disabilities: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(1), 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000517

- Tang, T. Z., & DeRubeis, R. J. (1999). Sudden gains and critical sessions in cognitivebehavioral therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(6), 894–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.67.6.894

- *Taylor, F. G., & Marshall, W. L. (1977). Experimental analysis of a cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01173505

- Teri, L., Logsdon, R. G., Uomoto, J., & McCuryy, S. M. (1997). Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: A controlled clinical trial. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 52B, P159–P166. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/52B.4.P159

- *Thomas, S. A., Drummond, A. E., Lincoln, N. B., Palmer, R. L., das Nair, R., Latimer, N. R., Hackney, G. L., Mandefield, L., Walters, S. J., Hatton, R. D., Cooper, C. L., Chater, T. F., England, T. J., Callaghan, P., Coates, E., Sutherland, K. E., Eshtan, S. J., & Topcu, G. (2019). Behavioural activation therapy for post-stroke depression: The BEADS feasibility RCT. Health Technology Assessment, 23(47), 1–176. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta23470

- Tindall, L., Mikocka-Walus, A., McMillan, D., Wright, B., Hewitt, C., & Gascoyne, S. (2017). Is behavioural activation effective in the treatment of depression in young people? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90(4), 770–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12121

- *Turner, R. W., Ward, M. F., & Turner, D. J. (1979). Behavioral treatment for depression: An evaluation of therapeutic components. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35(1), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(197901)35:1<166::AID-JCLP2270350127>3.0.CO;2-1

- *Vázquez, F. L., López, L., Torres, Á. J., Otero, P., Blanco, V., Diaz, O., & Paramo, M. (2020). Analysis of the components of a cognitive-behavioral intervention for the prevention of depression administered via conference call to nonprofessional caregivers: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062067

- *Vázquez, F. L., Torres, Á, Otero, P., Blanco, V., Díaz, O., & Estévez, L. E. (2017). Analysis of the components of a cognitive-behavioral intervention administered via conference call for preventing depression among non-professional caregivers: A pilot study. Aging & Mental Health, 21(9), 938–946. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1181714

- Viechtbauer, W., & Cheung, M. W. L. (2010). Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.11

- Wagner, A. W., Jakupcak, M., Kowalski, H. M., Bittinger, J. N., & Golshan, S. (2019). Behavioral activation as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder Among returning veterans: A randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 70(10), 867–873. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800572

- *Wilson, P. H., Goldin, J. C., & Charbonneau-Powis, M. (1983). Comparative efficacy of behavioral and cognitive treatments of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 7(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01190064

- World Health Organisation. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. World Health Organization. 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization. (2022). World mental health report; transforming mental health for all. World Health Organization.

- Zabihi, S., Lemmel, F. K., & Orgeta, V. (2020). Behavioural activation for depression in informal caregivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled clinical trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 1173–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.124