ABSTRACT

Objective: We present a mixed methods systematic review of the effectiveness of therapist empathic reflections, which have been adopted by a range of approaches to communicate an understanding of client communications and experiences. Methods: We begin with definitions and subtypes of empathic reflection, drawing on relevant research and theory, including conversation analysis. We distinguish between empathic reflections, reviewed here, and the relational quality of empathy (reviewed in previous meta-analyses). We look at how empathic reflections are assessed and present examples of successful and unsuccessful empathic reflections, also providing a framework of the different criteria used to assess their effectiveness (e.g., association with session or treatment outcome, or client next-turn good process). Results: In our meta-analysis of 43 samples, we found virtually no relation between presence/absence of empathic reflection and effectiveness, both overall and separately within-session, post-session and post-treatment. Although not statistically significant, we did find weak support for reflections of change talk and summary reflections. Conclusions: We argue for research looking more carefully at the quality of empathy sequences in which empathic reflections are ideally calibrated in response to empathic opportunities offered by clients and sensitively adjusted in response to client confirmation/disconfirmation. We conclude with training implications and recommended therapeutic practices.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: We found that therapist empathic reflections (as opposed to therapist empathy) are not inherently effective; instead, timing, delivery, and adjustment are critical. Detailed, careful process research on successful and unsuccessful empathic reflections is urgently needed to confirm emerging qualitative results and can improve psychotherapy practice and training.

Therapist empathic reflections are used to “reflect back” or share understandings of client communications and experiences. They are central to person-centered and experiential approaches to psychotherapy (Elliott et al., Citation2004; Goodman & Esterly, Citation1988; Murphy, Citation2019), but have been widely adopted and are a core part of basic therapeutic skills training programs (e.g., Hill, Citation2020; Ivey et al., Citation2022; Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013). We see empathic reflection as a type of therapist activity, technique or response mode. As part of the core curricula for training therapists and other professional helpers, therapeutic activities such as empathic reflections have been referred to as “skills” since the 1970s and 1980s (e.g., Ivey & Authier, Citation1978; Martin, Citation1983), deviating from in the ordinary language sense of “skill” as expertise or ability to do something well (Oxford English Dictionary, Simpson & Weiner, Citation1989).

In this article, we begin with definitions and subtypes of empathic reflection and provide clinical examples. We report an original meta-analysis of quantitative research on the effectiveness of empathic reflection without regard to how well or poorly it is carried out. We also review qualitative research briefly but focus more on conversation analysis research. We also examine the limitations of the research reviewed, before concluding with training implications and recommended therapeutic practices.

Definitions and Clinical Description

At the outset, we note that the term reflection is somewhat misleading. The term connotes a simple mirroring or paraphrasing of what the other person says; however, many empathic reflections are more complex than this. Accordingly, proponents of the person-centered tradition (e.g., Brodley, Citation2006; Mearns et al., Citation2013; Rogers, Citation1975) prefer empathic understanding responses or empathic following responses, while conversation analysts (e.g., Muntigl et al., Citation2014b) simply prefer empathic responses. Following Goodman and Dooley (Citation1976; see also Stiles, Citation1986), we define empathic reflections primarily in terms of their expressed intention (communicating understanding) rather than their form (paraphrase).

By calling them empathic reflections we highlight the connection of this form of response with empathy, while still distinguishing between the two concepts. That is, empathic reflections refer to responses primarily intended to convey the therapist’s empathic understanding of the client (Goodman & Esterly, Citation1988), regardless of how well they are performed. On the other hand, we use empathy to denote the quality or skillfulness of empathic responding more generally (including reflections). The classic definition of empathy is that of Carl Rogers (Citation1957, p. 99): “To sense the client’s private world as if it were your own, but without ever losing the ‘as if’ quality.”

In any case, as used in contemporary practice, empathic reflections are not necessarily either simple mirroring or paraphrasing responses, although they may be. They often express therapists’ implicit processes of inferring what clients are getting at and resonating (emotionally and bodily) with clients’ unspoken experiences (Elliott & Greenberg, Citation2021). Therefore, empathic reflections may have a depth dimension (Gendlin, Citation1968) and may be “additive” (Hammond et al., Citation1977). However, the degree of inference does not go beyond what the client presumably has available to conscious awareness.

Conversational analysis (CA), a qualitative, interdisciplinary approach to the study of social interaction (Sidnell & Stivers, Citation2013), has developed an extensive and useful body of research on empathic responses. CA researchers describe how, in response to troubles telling (e.g., by a client), empathic responses reveal the listener’s (e.g., therapist’s) understanding and appreciation of those troubles and the accompanying emotional experience (Weiste & Peräkylä, Citation2014). According to Hepburn and Potter (Citation2007), empathic responses are speaking turns that (a) formulate or describe/reference the other’s perspective or experience, and (b) acknowledge the client’s “expert” authority to know and describe their experience. In CA, formulations overlap substantially with what we are referring to as empathic reflections, displaying understanding by summarizing or providing an upshot of prior talk (e.g., Antaki, Citation2008; Heritage & Watson, Citation1979). Consistent with this CA perspective, empathy and empathic responses do not occur in isolation but are part of larger jointly accomplished empathy sequences (Muntigl et al., Citation2014b) in which clients attempt to make themselves understood, therapists offer understandings (commonly via empathic responses or formulations), and clients provide feedback about the accuracy or appropriateness of those understandings, thus critiquing a more conventional view of empathy as a one-way therapist intervention or discrete speech act (e.g., Heritage, Citation2011; Ruusuvuori, Citation2007).

Types of empathic reflection. Contemporary psychotherapists have identified various kinds of empathic reflection. We briefly summarize some of their distinctions. Hill’s (Citation2020) helping skills system includes two types of empathic reflection responses, primarily based on their target or content: Reflections of feeling can repeat, rephrase, or identify the client’s feelings, or may be more inferentially arrived at from nonverbal behavior or other aspects of the client’s situation or verbal communication. Restatements paraphrase content and meaning, and can reference material in the moment, earlier in a session, or even earlier in therapy. Ivey’s (Ivey et al., Citation2022; Ivey & Authier, Citation1978) microskill taxonomy includes several types of empathic reflections: encouraging (repeating what the client said), paraphrasing, summarizing, reflection of feelings, reflection of meaning, and empathic self-disclosure (where the therapist demonstrates understanding by sharing a relevant personal experience). To these Larson (Citation2020) adds first-person responses. In a first-person response, the therapist speaks from the point of view of the client, using the first-person (e.g., “So I hear a part of you saying, ‘I can’t stand this job anymore!’”).

Within motivational interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013) many kinds of reflection have been described and studied (Amrhein et al., Citation2008; Moyers et al., Citation2014). Broadly, reflections can be either simple (restating what the person has just said with little or no added meaning) or complex (where a guess is made about previously implicit meaning, or meaning or emphasis is added). MI then distinguishes among content of reflections: change talk (e.g., desire or reasons to change), sustain talk (difficulties in changing or reasons not to change), commitment language, and other (everything else). Among others, MI also describes summary reflections, which bring together multiple things the client has said. Finally, in order to help therapists broaden the range of their empathic reflections, Elliott and Greenberg (Citation2021) identified nine types of empathic reflections, based on different client micro-markers and corresponding aspects or tracks of client experience (empathic repetition, empathic reflection, empathic formulation, empathic refocusing, evocative reflection, exploratory reflection, process reflection, and empathic conjecture). However, there is little differential information about when and how to use specific types of empathic reflection. (See Elliott et al., Citationin press, Table 1 for a set of hypotheses about this.)

Table I. Conversation analysis transcription notation.

Assessment

Assessment of Empathic Reflections

There are several general systems for classifying therapist response modes that include empathic reflections. Hill’s system (e.g., Hill, Citation1986) has probably been used over the longest time period. However, over the past 20 years, the most frequently-used approach has been based on motivational interviewing, including the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC; Amrhein et al., Citation2008) and the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Coding Manual (MITI; e.g., Moyers et al., Citation2005, Citation2014). Empathic reflections are also included in the coding systems of Stiles (Citation1992) and Elliott (Citation1985). Beyond this, psychodynamic therapy researchers have sometimes assessed empathic reflection, although commonly referred to as clarification (e.g., McCullough et al., Citation1991).

Identifying reflections within different coding systems can be done reliably (e.g., Elliott et al., Citation1987; Hill, Citation1986; Lietaer & Gundrum, Citation2018; Stiles, Citation1986). However, there can be problems with identifying reflections across coding systems. For example, Ivey et al. (Citation1987) system scores deeper empathic reflections as interpretations (e.g., Weinrach, Citation1990), whereas Hill’s (Citation1986) coding definition sticks closer to the person-centered/experiential therapy tradition, which has a more expansive definition of reflections, including deeper, more exploratory empathic responses. In spite of these differences, Elliott et al. (Citation1987) found moderate convergence between six response mode scoring systems used to rate a common set of sessions with seven psychotherapists.

Assessment of the Effects of Empathic Reflections

The most widely-used method for assessing the effects or effectiveness of empathic reflections is the process-outcome approach, in which researchers measure empathic reflections (typically aggregated across a whole session) and use it to predict post-session or post-treatment outcome. At the post-session level, measures might include relationship quality (e.g., the Working Alliance Inventory, cf., Boardman et al., Citation2006). At the treatment level, measures might include client post-therapy abstinence from substance misuse (e.g., Palfai et al., Citation2016) or amount of pre–post symptom reduction (e.g., Brief Symptom Inventory; Milbrath et al., Citation1999). Such studies are intuitively appealing but suffer from causal inference problems, such as reverse- or third-variable causation (e.g., Stiles & Shapiro, Citation1994).

Sequential process methods are also increasingly used. In these studies, researchers identify examples of a particular therapy process, such as empathic reflection, and then look at what the client does next in the session, using measures of productive (e.g., client experiencing; Hill et al., Citation1983) or unproductive (e.g., counterchange talk in motivational interviewing; Moyers et al., Citation2009) process. The chief strength of this design is that it comes closer to warranting causal inference, because we can directly see whether what the client says next is ostensibly a response to what the therapist just said, as opposed to an evasion or change of topic.

Two other methods have also been used: In process-process correlational research, researchers throw out the sequential information and instead simply correlate the rate of empathic reflections with the rate of good or poor client process (e.g., observer ratings of client engagement), most often for whole sessions (e.g., Boardman et al., Citation2006). A less often used approach, sequential experiential research, has clients review recordings of sessions and rate the immediate within-session impact (e.g., helpfulness) of particular empathic reflections using Interpersonal Process Recall (e.g., Elliott et al., Citation1982).

Clinical Examples

We present two segments of emotion-focused therapy taken from Muntigl et al. (Citation2013), a CA study illustrating the sequential structures involved in successful re-affiliation after clients have disagreed with therapists’ prior empathic reflections. In order to convey important details about an interaction, CA uses special transcription conventions (Table 1; Jefferson, Citation2004), similar to a musical score. We invite the reader to study the following transcript for relevant details about the verbal and nonverbal means used by the client and therapist to construct a successful empathy sequence. The example of successful empathy we present here comes from near the end of therapy. The client Paula (a pseudonym for a good-outcome client in an EFT outcome study) is reporting on how she has acted in ways that are contrary to her prior patterns of behavior: rather than withdrawing from certain uncomfortable situations, she has confronted others and stood up for herself. (In addition to obtaining specific informed consent, identifying information has been removed from the following example. See for transcription conventions.)

Extract 1: 312.16(03) [13:28]/ Muntigl et al., Citation2013, p. 4.

Table

Next, we present part of a contrasting example of failed empathy, illustrating an empathic reflection in which the therapist makes an inaccurate guess about client self-critical process and ignores client signals of impending disagreement, leading to a small relational rupture (for more details, see Elliott et al., Citationin press).

Extract 2: 312.09(08)/ taken from Muntigl et al., Citation2012, p. 126.

Table

We will have more to say about these examples later. We are also aware that it can take some effort to fully appreciate CA transcripts, but we believe the standard simplified transcripts omit important interactional detail and, as a result, grossly underestimate the interpersonal complexity and collaborative nature of the empathic reflection process.

Previous Reviews

Orlinsky et al. (Citation2004) summarized the results of 14 previous process-outcome studies of therapist reflection using the box score method. Eight of these studies reported no association between reflections and outcome, five reported negative correlations, whereas only one reported a positive correlation. We are not aware of any previous quantitative meta-analyses of research on the effectiveness of empathic reflections. In contrast, a cumulative series of meta-analyses of process-outcome research on therapist empathy have been published (Bohart et al., Citation2002; Elliott et al., Citation2011, Citation2019). These reviews are consistent in finding a moderate association between therapist empathy and client post-therapy outcome (r = .28; equivalent to d = .58). These previous meta-analyses do not overlap with the studies in the following meta-analysis, in which we evaluated the effectiveness of empathic reflection without regard to how well or poorly it was carried out. In any case, we found no quantitative research on the skillful or unskillful delivery of empathic reflections per se.

Research Review

Meta-analysis of Quantitative Research

We carried out an original meta-analysis of available research relating therapist empathic reflections to measures of their effectiveness. Our research question was: What associations are there between presence or rate of empathic reflections and measures of their effectiveness? We were also interested in a range of potential moderator variables.

Search strategy

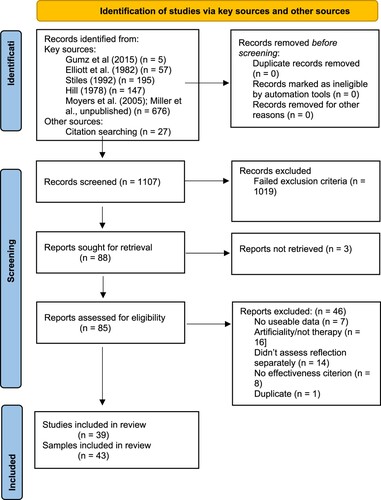

Because of the multiple meanings of the word “reflection” in the psychological literature and the fact than measures of empathic reflection are often not mentioned in abstracts, traditional keyword searching proved to be impossible. Instead, we started with a recent systematic review of measures of therapist verbal response modes (Gumz et al., Citation2015). From this, we identified the major approaches to measuring therapist response modes, and for each, one or two original or key references. For MI we used Amrhein et al. (Citation2008) and Moyers et al. (Citation2005); for general response mode rating systems we used Hill (Citation1978; Hill et al., Citation1981), Stiles (Citation1979, Citation1992), and Elliott et al. (Citation1982; Elliott, Citation1985); for psychodynamic response rating systems we used Gumz et al. (Citation2015). For each of these we did a cited source search using PsycInfo. In addition, we used citation searching of the studies we found to identify a further 27 sources to check. provides PRISMA information.

Characteristics of the studies

We arrived at 43 samples of clients (from 39 studies) and 214 effects (n = 2710 clients, 573 + therapists). Research on the effectiveness of empathic reflections has burgeoned over the past 20 years, driven largely by research on MI for substance misuse, which is now the most-studied treatment approach and client presenting problem in this literature. Reflection was overwhelmingly assessed by nonparticipant observers; most often raters did not distinguish between different types and contents of reflections. Reflections were most frequently coded at the therapist speaking turn level, but often then aggregated to the session level. Effectiveness evaluation most often involved observer ratings of good client process or client ratings (e.g., of outcome or helpfulness). The most common index of effectiveness was client next-speaking-turn good process (e.g., client change talk), but client post-therapy outcome measure scores were also common.

Estimation of effect size

We used Pearson correlations as our main metric of effect size, employing a set of procedures for extracting these. For example, if we had no other information than that the effect was nonsignificant, we set r at 0. We converted standardized difference and odds ratio effect sizes to correlations using standard formulas. For transition probabilities in sequential process design studies, we calculated phi coefficients. We also report results as Cohen’s d.

Coding procedure and analyses

In keeping with the exploratory nature of this meta-analysis, we coded multiple features of each study, including sample characteristics (e.g., client presenting problem), methodological features (e.g., rater perspective), and reflection characteristics (e.g., content of reflection). We conducted two sets of analyses, all using inverse variance weighting: First, we analyzed the 214 separate effects (nested within studies) to examine the impact of reflection and effectiveness criterion parameters, with inverse weighting by the number of effects within studies to control for nonindependence. Second, study-level analyses used weighted averages (weighted by inverse error: n – 3) of individual effects within client samples before further analysis, thus avoiding problems of nonindependence (Lipsey & Wilson, Citation2001). For overall effects and moderator and subgroup analyses, we also used Fisher’s r-to-z transformation, weighted studies by inverse error (n-3), analyzed for heterogeneity of effects using Cochrane’s Q, and used a restricted maximum likelihood random effects model (calculated using Wilson’s, Citation2021 updated macros for SPSS). Finally, we calculated I2, an estimate of the proportion of variation due to true variability as opposed to random error (Higgins et al., Citation2003) and generated a funnel plot. The main features of the 43 studies (organized by effectiveness criterion) can be found in supplemental Table S1.

Results

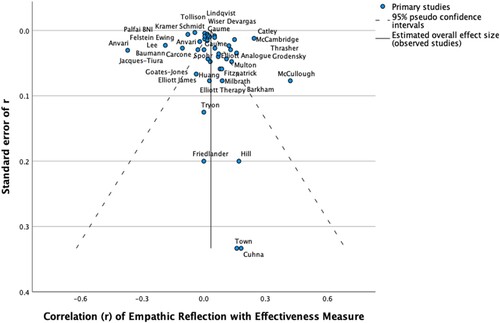

Overall Effectiveness. We calculated the overall effectiveness for empathic reflections in three ways (study level, effects level without weighting, effects level with weighting by inverse error and number of effects per study), with virtually identical findings of around zero (the largest with mean rw = .02, equivalent to d = .04). Overall, we found no relation between therapist empathic reflections and effectiveness with clients. Furthermore, these effects were highly homogeneous (low Higgins I2 values). The null effect here obviates the usual bias checks, such as funnel plots and fail-safe numbers, although we did find some evidence of bias in the form of a medium-sized correlation of .33 (p < .05) between effect size (r) and standard error of r (see funnel plot in ). This might mean that our estimate of mean weighted r = .02 is, if anything, overly optimistic.

Figure 2. Funnel plot of empathic reflection-effectiveness effects by standard error: study level effects.

Immediate Within-session Effectiveness. As shows, our null results were remarkably consistent across all three levels of effectiveness: within-session, postsession, and posttherapy. Within-session effectiveness included results using three criteria (sequential process, sequential experiential, and process-process correlational); because studies often included measures using different criteria, only effects-level data could be analyzed (k = 136 effects), although analyses controlled for number of effects per study. In addition, empathic reflections did not predict within-session effectiveness. Breaking down within-session effectiveness further, we found for sequential process (k = 82) and sequential experiential (k = 42) effects, mean rw values were -.01 (d = -.03) and .04 (d = .08) respectively, again indicating no relation between empathic reflections and immediate within-session effectiveness. On the other hand, process-process correlation effects (k = 12) showed heterogenous (I2 = 53%) but slightly favorable results marginally supporting the effectiveness of empathic reflections (mean rw = .14; CI: -.08, .35; d = .28). This result suggests that therapist empathic reflections show a small tendency to be associated within sessions with higher rates of client productive process (e.g., proportion of client change talk; Catley et al., Citation2006). However, the direction of causal influence is not clear in these studies, so this effect is likely to be inflated by unmeasured reverse or circular causal processes.

Table II. Effect-level effects across change process criteria and temporal level.

Postsession Effectiveness. We found no effect for postsession effectiveness measures (k = 11 effects; rw = .01; CI: -.22, .19; d = .02; Q = 2.1, NS). Although the sample was small, the effects are consistent, suggesting that rates of empathic reflection are generally unrelated to global measures of good session outcome or process, including, for example, client post-session engagement in treatment (e.g., Huang et al., Citation2013).

Posttherapy Effectiveness. Similarly, we found no effect for empathic reflections on measures of posttherapy outcome (k = 67 effects), in spite of the more robust sample and high consistency. The effects level mean rw was .03 (d = .06; Q = 29.6, NS). Thus, frequency of empathic reflections appears to be unrelated to treatment outcome. As with immediate within-session effectiveness, these effects were significantly and consistently smaller than r = .1, generally considered to be a small effect, justifying an inference of a null or no-difference effect.

Moderator Analyses

The lack of heterogeneity made it unlikely that we would find substantial effects for moderator variables, while at the same time leaving open the question of what might make reflections helpful or unhelpful. For this reason, we carried out exploratory analyses on a range of potential moderators.

Type of Reflection. The most common distinction we encountered in the literature was simple, brief reflections vs. more complex, ambitious reflections, a distinction described variously as additive (Hammond et al., Citation1977), change-focused, deeper or complex (e.g., Amrhein et al., Citation2008), or exploratory (e.g., Barkham & Shapiro, Citation1986). However, we found no overall difference in effects between (a) undifferentiated general reflections, (b) simple reflections, and (c) more complex reflections, with all effects hovering around zero. Perhaps complexity or ambitiousness of reflections is still too undifferentiated a concept; further, adding more of a speculative element may simply mean that the therapist is more likely to get it wrong.

Target/Content of Reflection. A more fine-grained and potentially promising approach has been to examine the specific contents of reflections, that is, what they refer to. This is certainly the rationale behind the common distinction between reflections of content and feeling (e.g., Hill, Citation1978), as well as the proliferation of the different types of change-related reflections in MI (e.g., Amrhein et al., Citation2008). We found two small, statistically nonsignificant but intriguing effects favoring change talk reflections (k = 13; mean rw = .12; CI: -.08, .31; ns; d = .24) and summary reflections (k = 5; mean rw = .15; CI: -.22, .48; ns; d = .30). These effects also help explain the general null effect, which may be the result of watering down slightly helpful reflection contents with contents that have no relation to effectiveness.

Other Moderators. Looking at sample level effects (k = 43), we found no differences or significant effects for type of therapy (MI, psychodynamic, mixed/unspecified), therapist experience, client presenting difficulty, client ethnicity (non-European origin) or decade in which the study was conducted. Similarly, for effect level effects (k = 214), we found highly consistent null results across a wide range of effectiveness variables, including client IPR turn-ratings, client next-turn productive process, client or observer post-session ratings, client posttherapy outcome or status, and therapist turn-level or post session ratings.

Review of Qualitative Research

We located only four qualitative studies specifically examining the effectiveness of psychotherapist empathic reflections (Bachelor, Citation1988; Bohart & Boyd, Citation1997; MacFarlane et al., Citation2016; Myers, Citation2000). A common theme across the four studies was that empathic reflections can be interpreted by clients in different ways, and they are not the only responses that lead to clients’ experiences of empathy. Three of the four studies did find that reflections were associated with an increase in client self-understanding.

Review of Conversation Analysis Studies

CA investigations typically identify and describe commonly occurring sequences of responsive actions (e.g., question-answer, storytelling-response) for how they are accomplished in interaction both vocally (e.g., grammar, prosody) and non-vocally (e.g., gesture, gaze). There is a growing body of CA work on empathic responses in psychotherapy and related helping interactions, most of which address empathic reflection (“formulation”; e.g., Elliott et al., Citation2000; Muntigl et al., Citation2014b). We found 21 CA studies specifically focused on psychotherapy (marked with “+” in the reference list). These studies involved roughly 1150 segments of therapy, and an unknown number of clients. (A summary of CA findings, with more information, is available in supplemental Table S2.)

Muntigl et al. (Citation2014b; see also Elliott et al., Citation2000) observed a three-part sequence in psychotherapy involving therapist empathic formulations (i.e., reflections): (a) the client reports a distressing experience or situation, (b) the therapist provides an empathic formulation (reflection), and (c) the client confirms or disconfirms the therapist’s empathic reflection. We refer back to the CA transcript with the client Paula presented earlier to illustrate how CA research has shed light on how empathic reflections feature in successful empathy sequences.

Successful empathy (Extract 1)

Empathic opportunities: Client Troubles telling + Affective Stance Displays. CA research indicates that empathy sequences begin with clients providing the therapist with detailed, step-by-step access to a distressing experience or situation (troubles telling; Jefferson, Citation1988) and their progress in dealing with those troubles, as well as their affective stance (Stivers, Citation2008) toward those troubles (i.e., how they feel about them). This offers an empathic opportunity for therapists to show their understanding and support (e.g., Davis, Citation1986; Muntigl et al., Citation2014b). In example 1, lines 01–10 illustrate how clients can develop an affective stance, first through descriptions of being “a little bit on the aggressive side of things” and adopting an “assertiv:e behaviour, mode.”, and then by stating a “worry” in which she is unsure as to whether she will be able to find a balance of taking control while not exceeding boundaries (lines 14–17). In line 17, Paula conveys some tentative self-reassurance via a positive assessment “it's comin:g (0.4) alo:ng (0.7) alright” and a series of slow successive nods. The therapist, in turn, nods in unison, thus displaying token affiliation ( = the minimum required) with Paula’s assessment. Paula’s stance is also built up through a number of non-vocal, mainly gestural, resources. For example, in line 03, her circular hand movement reinforces her claim that her behavior is “starting to- (.) to change.” Thus, the affective stance components of Paula’s turn include descriptions of having been aggressive/assertive, claims of desiring change, worry, and positive assessment that she will find a balance along with gestures that accompany and strengthen Paula’s stance.

Therapist formulation response. CA research shows that therapists commonly respond to empathic opportunities with formulation responses (empathic reflections; e.g., Antaki, Citation2008; Muntigl et al., Citation2014b). Broadly, these are affiliative responses that act to support, validate, or help clients feel that they make sense (Heritage, Citation2011). In lines 18–22, we see the therapist offering a summary formulation that captures the gist of the client’s prior talk. The formulation is produced without any intervening pauses (i.e., contiguous to Paula’s prior turn, which often conveys affiliation or “being in agreement”) and highlights how Paula is able to achieve a “healthy” balance between competing needs: taking control/ standing up for herself vs. not imposing on others (“do it too aggressively”). Then, in lines 25–27, the therapist continues her turn by downplaying the possible negative effects of Paula taking control and being assertive (“isn’t, … turning off everyone you meet”). In common with other CA studies (e.g., Weiste et al., Citation2016), the therapist’s formulation here works empathically in multiple ways: (a) it demonstrates understanding of the client’s dilemma by summarizing her affective stance and staying close to the client’s own descriptions of her experience; (b) it invites confirmation from the client, thus allowing her to maintain “ownership of experience” and to validate her expert role by confirming or disagreeing with the therapist’s response; (c) it supports and thus affiliates with the client’s emotional meanings, but without identifying with or intruding on the client’s feelings as, for example, through sympathy. Such subtleties are difficult to capture in standardized measures of therapist empathic reflection.

Client Confirmation. Responses to therapist formulations/empathic reflections, which constitute the third position of empathy sequences, have been shown to be either affiliative or disaffiliative (e.g., Muntigl & Horvath, Citation2014). Whereas affiliative responses display varying degrees of agreement with the therapist’s proffered empathy, disaffiliative responses convey disagreement (e.g., Elliott et al., Citation2000), often as either a form of direct opposition or as communicating disengagement such as refraining from answering. Strong forms of affiliation have been noted to co-accomplish empathic moments (Heritage, Citation2011), in which speakers display interactional synchrony at both the vocal and non-vocal (e.g., synchronous nodding) levels and display (prosodically) upgraded, overlapping confirmation, as seen in Example 1, lines 21–29.

Failed empathy and client disconfirmation (Extract 2)

The defining feature of a failed empathy sequence is client disaffiliation (disconfirmation; e.g., Muntigl, Citation2020; Weiste, Citation2015), as can be seen in Extract 2 (from session 6 of Paula’s therapy, presented earlier), which involves an overly-ambitious empathic conjecture (lines 8–10). Lines 11–15 illustrate how the client disaffiliates with what the therapist had put forward and instead prepares to clarify her original position (not shown in transcript). Her disaffiliation at lines 12 onwards can be immediately inferred from the transcript: First, there is a significant silence following the therapist’s turn completion (line 11), which implicates that confirmation may not be provided (see Pomerantz, Citation1984). Second, she utters a pronounced sigh, as expressed via a deep in- and out-breath (“.hhh::: hhh:::”), which also signals potential disagreement in this sequential position (Hoey, Citation2014). Third, following another lengthy pause of 8.8 sec., she expresses explicit disagreement, “no:” in line 14. After having rejected the therapist’s attempt at formulating the basis of her “feelings of failure,” the client will continue by articulating her own explanation. (For the complete extract and analysis see Elliott et al., Citationin press.)

The two examples illustrate how empathic reflections appear to succeed or fail through the operation of multiple complex and nuanced moment-by-moment processes. The chief value of this CA literature is to document the existence of some of these processes, essentially qualitative moderator variables not currently reflected in the quantitative research literature.

Limitations of the Research

Although empathy is considered a critical change process in psychotherapy (e.g., Bohart & Greenberg, Citation1997; Elliott et al., Citation2019), little work has been done to show how empathy is achieved within sessions at an interactional level, for example, via therapist empathic reflections and the client and therapist actions that precede and follow them. Historically, research on empathy and empathic reflections has lacked the specificity and contextual sensitivity needed for clarifying when and how (i.e., using which communicative resources) empathic reflections and the empathy sequences in which they are embedded are most likely to succeed or fail. CA research challenges notions of therapists as the sole and unilateral empathy providers and of clients as passive empathy recipients, highlighting the interconnectedness and sequential nature of therapy participants’ interactions. Note also that CA researchers, using audio- and video-recordings and detailed transcripts, have evaluated the success or failure of the therapist’s empathic reflections based on the commonsense criteria of client affiliation/disaffiliation and progress on therapeutic work, evaluative standards that were not used in any of the studies in our meta-analysis.

Our results make clear that we still lack a clear account of what kinds of reflections, in what kinds of within-session contexts, have what kinds of helpful and hindering effects. The preliminary work needed for a fuller understanding of how and when empathic reflections work has not been addressed by any of the change process research included in our meta-analysis. This suggests that psychotherapy researchers have engaged in premature quantification before fully understanding how and when empathic reflections work and what makes a skillful, effective empathic reflection. Furthermore, as the CA literature highlights, the existing rating systems for therapist empathic reflections are blunt instruments that ignore important aspects of client context (e.g., empathic opportunities), fail to account for nonverbal and paralinguistic factors, and do not assess client next turn affiliation/disaffiliation and therapist ability to attend to and use this kind of client feedback.

Training Implications

Training programs that teach empathy and empathic reflection go back to Carl Rogers’ training courses in the 1940s and expanded rapidly in the 1970s. Meta-analyses (e.g., Ngo, Citation2022; Teding van Berkhout & Malouff, Citation2016) suggest that such training programs are generally effective in imparting empathy and empathic reflection skills, and that both didactic and skill practice components contribute to this effectiveness. Unfortunately, the impact of such trainings on client outcome is unknown; further, their curricula have often promulgated simplistic ideas about empathic reflections and led to their indiscriminate use.

CA research on empathy sequences and empathic reflection/formulation can inform therapy practice and training. First, therapists can be taught to better recognize opportunities for empathy. Supervisors can help students improve the timing and accuracy of their empathic reflections by attending to opportunities for clients to unpack their experiences and further develop their stance.

Second, in teaching about empathic reflections, trainers can use existing CA work to help their supervisees to learn about multiple, multimodal ways to display an understanding of clients’ troubles, including a range of empathic reflections and related responses. For example, supervisors can point out the value of matching or not matching the client in speech rhythm or pitch for influencing whether an utterance is heard by the client as more or less empathic (Weiste & Peräkylä, Citation2014). CA studies can also highlight that therapists’ responses may convey different degrees of empathic strength or intensity (Jefferson, Citation1988). For example, a nod at the end of the trouble telling may convey insufficient empathy (Stivers, Citation2008).

Finally, in evaluating empathic receipts, trainers and supervisors can help supervisees recognize when their empathic reflections are not confirmed by clients so that they can make efforts to reaffiliate or adjust their responses in order elicit a stronger endorsement from clients (e.g., “exactly!”). For example, a CA-trained therapist in Example 2 would probably have recognized Paula’s initial expressive sigh and silence as signaling disagreement, that is, disaffiliation with her therapist’s empathic conjecture. In fact, we would argue that the most important form of deliberate practice comes from learning how to learn from our clients’ immediate reactions to what we have offered them.

Therapeutic Practices

Based on our research review, as well as clinical experience, we suggest that therapists:

Listen for and reflect client change talk (e.g., desire for change), especially with clients struggling with ambivalence about self-damaging activities. [Source of recommendation: reflection meta-analysis]

Offer summary reflections that pull together what therapist and client have talked about, where possible formulating client experience into narratives about how their difficulties unfold. [Source: reflection meta-analysis]

Base empathic reflections on genuine empathy and positive regard for the client, allowing this to be conveyed to the client. [Source: empathy meta-analysis]

Offer empathic reflections when clients offer empathic opportunities, for instance, when they express emotion in the context of telling about their troubles (or other important experiences). [Source: CA review]

Offer empathic reflections particularly when patients are confused or uncertain about their feelings, in order to enhance their self-understanding [Source: review of qualitative research]

Reflect not only what the client is saying and feeling but also how intensely they are saying or feeling it, and try to match this intensity in the manner of the reflection. [Source: CA review]

Match the delivery of reflections to their distance from the client’s main message: The further away a reflection is from the client’s expressed experience, the more careful, tentative or humble it needs to be. [Source: CA review]

Pay close attention to how clients immediately respond to reflections; reflect hesitation and lukewarm agreement nondefensively as signs of having missed the client’s meaning [Source: CA review]

Correct empathic reflections when this happens and perhaps acknowledge having initially missed the client’s meaning or experience. [Source: CA review]

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (53.6 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2023.2218981.

References

- (*Sources used in meta-analysis; +Sources used in conversational analysis review)

- Amrhein, P., Miller, W. R., Moyers, T., & Ernst, D. (2008). Manual for the motivational interviewing skill code (MISC). Department of Psychology Faculty Scholarship and Creative Works. 27. https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/psychology-facpubs/27.

- +Antaki, C. (2008). Formulations in psychotherapy. In A. Peräkylä, C. Antaki, S. Vehviläinen, & I. Leudar (Eds.), Conversation analysis and psychotherapy (pp. 26–42). Cambridge University Press.

- *Anvari, M., Hill, C. E., & Kivlighan, D. M. (2020). Therapist skills associated with client emotional expression in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 30(7), 900–911. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1680901

- *Anvari, M. S., Dua, V., Lima-Rosas, J., Hill, C. E., & Kivlighan Jr, D. M. (2021, September 30). Facilitating exploration in psychodynamic psychotherapy: Therapist skills and client attachment style. Journal of Counseling Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000582

- Bachelor, A. (1988). How clients perceive therapist empathy: A content-analysis of received empathy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 25(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085337

- *Barkham, M., & Shapiro, D. A. (1986). Counselor verbal response modes and experienced empathy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 33(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.33.1.3

- *Baumann, E., & Hill, C. E. (2008). The attainment of insight in the insight stage of the hill dream model: The influence of client reactance and therapist interventions. Dreaming, 18(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/1053-0797.18.2.127

- +Bercelli, F., Rossano, F., & Viaro, M. (2008). Clients’ responses to therapists’ reinterpretations. In A. Peräkylä, C. Antaki, S. Vehviläinen, & I. Leudar (Eds.), Conversation analysis and psychotherapy (pp. 43–61). University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511490002.004

- *Boardman, T., Catley, D., Grobe, J., Little, T., & Ahluwalia, J. (2006). Using motivational interviewing with smokers: Do therapist behaviors relate to engagement and therapeutic alliance? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 31(4), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.006

- Bohart, A. C., & Boyd, G. (1997, December). Clients’ construction of the therapy process: A qualitative analysis. Poster presented at meeting of North American Chapter of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, Tucson, AZ.

- Bohart, A. C., Elliott, R., Greenberg, L. S., & Watson, J. C. (2002). Empathy. In J. Norcross (Ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work (pp. 89–108). Oxford University Press.

- Bohart, A. C., & Greenberg, L. S. (1997). Empathy and psychotherapy: An introductory overview. In A. Bohart & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Empathy reconsidered: New directions in psychotherapy (pp. 3–31). American Psychological Association Press.

- Brodley, B. T. (2006). Non-directivity in client-centered therapy. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 5(1), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2006.9688391

- *Carcone, A. I., Naar-King, S., Brogan, K. E., Albrecht, T., Barton, E., Foster, T., Martin, T., & Marshall, S. (2013). Provider communication behaviors that predict motivation to change in black adolescents with obesity. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 34(8), 599–608. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182a67daf

- *Catley, D., Harris, K. J., Mayo, M. S., Hall, S., Okuyemi, K. S., Boardman, T., & Ahluwalia, J. (2006). Adherence to principles of motivational interviewing and client within-session behavior. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465805002432

- *Cunha, C., Gonçalves, M. M., Hill, C. E., Mendes, I., Ribeiro, A. P., Sousa, I., Angus, L., & Greenberg, L. S. (2012). Therapist interventions and client innovative moments in emotion-focused therapy for depression. Psychotherapy, 49(4), 536–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028259

- +Davis, K. (1986). The process of problem (re)formulation in psychotherapy. Sociology of Health and Illness, 8(1), 44–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep11346469

- *DeVargas, E. C., & Stormshak, E. A. (2020). Motivational interviewing skills as predictors of change in emerging adult risk behavior. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000270

- *Elliott, R. (1985). Helpful and nonhelpful events in brief counseling interviews: An empirical taxonomy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 32(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.32.3.307

- *Elliott, R., Barker, C. B., Caskey, N., & Pistrang, N. (1982). Differential helpfulness of counselor verbal response modes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 29(4), 354–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.29.4.354

- Elliott, R., Bohart, A., Larson, D., Muntigl, P., & Smoliak, O. (in press). Empathic reflection. In C. E. Hill & J. C. Norcross (Eds.), Psychotherapy skills and methods that work (pp. 99–137). Oxford University Press.

- Elliott, R., Bohart, A. C., Watson, J. C., & Greenberg, L. S. (2011). Empathy. In J. Norcross (Ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work (2nd ed., pp. 132–152). Oxford University Press.

- Elliott, R., Bohart, A. C., Watson, J. C., & Murphy, D. (2019). Empathy. In J. C. Norcross, & M. J. Lambert (Eds.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Evidence-based therapist contributions (3rd ed., Vol. 1, pp. 245–287). Oxford University Press.

- Elliott, R., & Greenberg, L. S. (2021). Emotion-focused counselling in action. Sage.

- Elliott, R., Hill, C. E., Stiles, W. B., Friedlander, M. L., Mahrer, A., & Margison, F. (1987). Primary therapist response modes: A comparison of six rating systems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(2), 218–223. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.55.2.218

- *Elliott, R., James, E., Reimschuessel, C., Cislo, D., & Sack, N. (1985). Significant events and the analysis of immediate therapeutic impacts. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 22(3), 620–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085548

- +Elliott, R., Slatick, E., & Urman, M. (2000). “So the fear is like a thing … ”: A significant empathic exploration event in process-experiential therapy for PTSD. In J. Marques-Teixeira, & S. Antunes (Eds.), Client-centered and experiential psychotherapy (pp. 179–204). Vale & Vale.

- Elliott, R., Watson, J. C., Goldman, R. N., & Greenberg, L. S. (2004). Learning emotion-focused therapy: The process-experiential approach to change. American Psychological Association.

- *Feldstein Ewing, S. W., Gaume, J., Ernst, D. B., Rivera, L., & Houck, J. M. (2015). Do therapist behaviors differ with hispanic youth? A brief look at within-session therapist behaviors and youth treatment response. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(3), 779–786. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000079

- *Fitzpatrick, M. R., Stalikas, A., & Iwakabe, S. (2001). Examining counselor interventions and client progress in the context of the therapeutic alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(2), 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.2.160

- *Friedlander, M. L., Thibodeau, J. R., & Ward, L. G. (1985). Discriminating the “good” from the “bad” therapy hour: A study of dyadic interaction. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 22(3), 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085549

- *Gaume, J., Bertholet, N., Faouzi, M., Gmel, G., & Daeppen, J. B. (2010). Counselor motivational interviewing skills and young adult change talk articulation during brief motivational interventions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 39(3), 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2010.06.010

- *Gaume, J., Gmel, G., & Daeppen, J. B. (2008). Brief alcohol interventions: Do counsellors’ and patients’ communication characteristics predict change? Alcohol and Alcoholism, 43(1), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agm141

- Gendlin, E. T. (1968). The experiential response. In E. Hammer (Ed.), Use of interpretation in treatment (pp. 208–227). Grune & Stratton. http://previous.focusing.org/gendlin/docs/gol_2156.html.

- *Goates-Jones, M. K., Hill, C. E., Stahl, J. V., & Doschek, E. E. (2009). Therapist response modes in the exploration stage: Timing and effectiveness. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 22(2), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070903185256

- Goodman, G., & Dooley, D. (1976). A framework for help-intended communication. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 13(2), 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088322

- Goodman, G., & Esterly, G. (1988). The talk book: The intimate science of communicating in close relationships. Ballantine.

- *Grodensky, C., Golin, C., Parikh, M. A., Ochtera, R., Kincaid, C., Groves, J., Widman, L., Suchindran, C., McGirt, C., Amola, K., & Bradley-Bull, S. (2017). Does the quality of safetalk motivational interviewing counseling predict sexual behavior outcomes among people living with HIV? Patient Education and Counseling, 100(1), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.08.014

- Gumz, A., Treese, B., Marx, C., Strauss, B., & Wendt, H. (2015). Measuring verbal psychotherapeutic techniques: A systematic review of intervention characteristics and measures. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1705), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01705

- +Guxholli, A., Voutilainen, L., & Peräkylä, A. (2021). Safeguarding the therapeutic alliance: Managing disaffiliation in the course of work with psychotherapeutic projects. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(596972), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.596972

- +Hak, T., & de Boer, F. (1996). Formulations in first encounters. Journal of Pragmatics, 25(1), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(94)00076-7

- Hammond, D. C., Hepworth, D. H., & Smith, V. G. (1977). Improving therapeutic communication: A guide for developing effective techniques. Wiley.

- +Hepburn, A., & Potter, J. (2007). Crying receipts: Time, empathy, and institutional practice. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 40(1), 89–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810701331299

- +Heritage, J. (2011). Territories of knowledge, territories of experience: Empathic moments in interaction. In T. Stivers, L. Mondada, & J. Steensig (Eds.), The morality of knowledge in conversation (pp. 159–183). Cambridge University Press.

- +Heritage, J., & Watson, R. (1979). Formulations as conversational objects. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language (pp. 123–162). Irvington Press.

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ, 327(7414), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

- Hill, C. E. (1978). The development of a system for classifying counselor responses. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 25(5), 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.25.5.461

- Hill, C. E. (1986). An overview of the hill counselor and client verbal response modes category systems. In L. S. Greenberg, & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook (pp. 131160). Guilford.

- Hill, C. E. (2020). Helping skills: Facilitating exploration, insight, and action (5th ed.). American Psychological Association.

- *Hill, C. E., Carter, J. A., & O'Farrell, M. K. (1983). A case study of the process and outcome of time-limited counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.30.1.3. [original study].

- *Hill, C. E., Greenwald, C., Reed, K. G., Charles, D., O’farrell, M. K., & Carter, J. A. (1981). Manual for the counselor and client verbal response category system. Columbus, OH: Marathon.

- +Hoey, E. M. (2014). Sighing in interaction: Somatic, semiotic, and social. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47(2), 175–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2014.900229

- *Houck, J. M., & Moyers, T. B. (2015). Within-session communication patterns predict alcohol treatment outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 157, 205–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.025. [see also Moyers et al., 2009).

- *Huang, T., Hill, C., & Gelso, C. (2013). Psychotherapy engagers versus non-engagers: Differences in alliance, therapist verbal response modes, and client attachment. Psychotherapy Research, 23(5), 568–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.807378

- Ivey, A. E., & Authier, J. (1978). Microcounseling: Innovations in interviewing, counseling, psychotherapy, and psychoeducation (2nd ed.). Charles C Thomas.

- Ivey, A. E., Ivey, M. B., & Simek-Downing, L. (1987). Counseling and psychotherapy: Skills, theories, and practice (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Ivey, A. E., Ivey, M. B., & Zalaquett, C. P. (2022). Intentional interviewing and counselling: Facilitating client development in a multicultural society (10th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- *Jacques-Tiura, A. J., Carcone, A. I., Naar, S., Brogan Hartlieb, K., Albrecht, T. L., & Barton, E. (2017). Building motivation in African American caregivers of adolescents with obesity: Application of sequential analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 42(2), jsw044–jsw141. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsw044

- +Jefferson, G. (1988). On the sequential organization of troubles talk in ordinary conversation. Social Problems, 35(4), 418–441. https://doi.org/10.2307/800595

- +Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13–31). John Benjamins.

- *Kramer Schmidt, L., Moyers, T. B., Nielsen, A. S., & Andersen, K. (2019). Is fidelity to motivational interviewing associated with alcohol outcomes in treatment-seeking 60+ year-old citizens? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 101, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.03.004

- Larson, D. (2020). The helper's journey: Empathy, compassion, and the challenge of caring (2nd ed.). Research Press.

- *Lee, D. Y., Uhlemann, M. R., & Haase, R. F. (1985). Counselor verbal and nonverbal responses and perceived expertness, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 32(2), 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.32.2.181

- Lietaer, G., & Gundrum, M. (2018). His master’s voice: Carl rogers’ verbal response modes in therapy and demonstration sessions throughout his career: A quantitative analysis and some qualitative-clinical comments. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 17(4), 275–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2018.1544091

- *Lindqvist, H., Forsberg, L., Enebrink, P., Andersson, G., & Rosendahl, I. (2017). The relationship between counselors’ technical skills, clients’ in-session verbal responses, and outcome in smoking cessation treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 77, 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2017.02.004

- Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Sage.

- MacFarlane, P., Anderson, T., & McClintock, A. S. (2016). Empathy from the client’s perspective: A grounded theory analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 27(2), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1090038

- Martin, D. C. (1983). Counseling and therapy skills. Prospect heights. Waveland Press.

- *McCambridge, J., Day, M., Thomas, B. A., & Strang, J. (2011). Fidelity to motivational interviewing and subsequent cannabis cessation among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 36(7), 749–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.002

- *McCullough, L., Winston, A., Farber, B. A., Porter, F., Pollack, J., Vingiano, W., Laikin, M., & Trujillo, M. (1991). The relationship of patient-therapist interaction to outcome in brief psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 28(4), 525–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.28.4.525

- Mearns, D., Thorne, B., & McLeod, J. (2013). Person-centred counselling in action (4th ed.). Sage.

- *Milbrath, C., Bond, M., Cooper, S., Znoj, H. J., Horowitz, M. J., & Perry, J. C. (1999). Sequential consequences of therapists’ interventions. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 8(1), 40–54.

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (3rd ed.). Guilford.

- Moyers, T. B., Manuel, J. K., & Ernst, D. (2014). Motivational interviewing treatment integrity coding Manual 4.1. [Unpublished manual, University of New Mexico].

- *Moyers, T. B., Martin, T., Houck, J. M., Christopher, P. J., & Tonigan, J. S. (2009). From in-session behaviors to drinking outcomes: A causal chain for motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(6), 1113–1124. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017189. [see also Houck & Moyers, 2009).

- Moyers, T. B., Martin, T., Manuel, J. K., Hendrickson, S. M., & Miller, W. R. (2005). Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28(1), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001

- *Multon, K. D., Ellis-Kalton, C. A., Heppner, M. J., & Gysbers, N. C. (2003). The relationship between counselor verbal response modes and the working alliance in career counseling. The Career Development Quarterly, 51(3), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2003.tb00606.x

- +Muntigl, P. (2020). Managing distress over time in psychotherapy: Guiding the client in and through intense emotional work. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 3052. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03052

- +Muntigl, P., & Horvath, A. O. (2014). The therapeutic relationship in action: How therapists and clients co-manage relational disaffiliation. Psychotherapy Research, 24(3), 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.807525

- +Muntigl, P., Knight, N., & Angus, L. (2014a). Targeting emotional impact in storytelling: Working with client affect in emotion-focused psychotherapy. Discourse Studies, 16(6), 753–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445614546255

- +Muntigl, P., Knight, N., Horvath, A. O., & Watkins, A. (2012). Client attitudinal stance and therapist-client affiliation: A view from grammar and social interaction. Research in psychotherapy: Psychopathology. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 15(2), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.4081/RIPPPO.2012.119

- +Muntigl, P., Knight, N., & Watkins, A. (2014b). Empathic practices in client-centered psychotherapies. In E. M. Graf, M. Sator, & T. Spranz-Fogasy (Eds.), Discourses of helping professions (pp. 33–57). John Benjamins.

- +Muntigl, P., Knight, N., Watkins, A., Horvath, A. O., & Angus, L. (2013). Active retreating: Person-centered practices to repair disaffiliation in therapy. Journal of Pragmatics, 53, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2013.03.019

- Murphy, D. (2019). Person-centred experiential counselling for depression (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Myers, S. (2000). Empathic listening: Reports on being heard. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 40(2), 148–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167800402004

- Ngo, H. L. (2022). Instructional components and their combinations for teaching empathy to mental health practitioners and trainees: Pairwise and network meta-analyses. [Unpublished Masters thesis]. Graduate Department of Applied Psychology and Human Development, University of Toronto.

- Orlinsky, D. E., Rønnestad, M. H., & Willutzki, U. (2004). Process and outcome in psychotherapy. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed., pp. 307–389). Wiley.

- *Palfai, T. P., Cheng, D. M., Bernstein, J. A., Palmisano, J., Lloyd-Travaglini, C. A., Goodness, T., & Saitz, R. (2016). Is the quality of brief motivational interventions for drug use in primary care associated with subsequent drug use? Addictive Behaviors, 56, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.12.018

- +Peräkylä, A. (2019). Conversation analysis and psychotherapy: Identifying transformative sequences. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 52(3), 257–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2019.1631044

- +Pomerantz, A. (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shaped. In J. M. Atkinson & J. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action: Studies in conversation analysis (pp. 57–101). Cambridge University Press.

- *Rodriguez, M., Walters, S. T., Houck, J. M., Ortiz, J. A., & Taxman, F. S. (2018). The language of change among criminal justice clients: Counselor language, client language, and client substance use outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 626–636. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22534

- Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045357

- Rogers, C. R. (1975). Empathic: An unappreciated way of being. The Counseling Psychologist, 5(2), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/001100007500500202

- Ruusuvuori, J. (2007). Managing affect: Integrating empathy and problem solving in two types of health care consultation. Discourse Studies, 9, 597–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445607081269

- Sidnell, J., & Stivers, T. (2013). The handbook of conversation analysis. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Simpson, J. A., Weiner, E. S. C, & Oxford University Press (1989). The Oxford English dictionary. Clarendon Press.

- *Spohr, S. A., Taxman, F. S., Rodriguez, M., & Walters, S. T. (2016). Motivational interviewing fidelity in a community corrections setting: Treatment initiation and subsequent drug use. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.07.012

- Stiles, W. B. (1979). Verbal response modes and psychotherapeutic technique. Psychiatry, 42, 49–62.

- Stiles, W. B. (1986). Development of a taxonomy of verbal response modes. In L. S. Greenberg & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook (pp. 161–200). Guilford.

- Stiles, W. B. (1992). Describing talk: A taxonomy of verbal response modes. Sage.

- Stiles, W. B., & Shapiro, D. A. (1994). Disabuse of the drug metaphor: Psychotherapy process-outcome correlations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(5), 942–948. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.62.5.942

- +Stivers, T. (2008). Stance, alignment, and affiliation during storytelling: When nodding is a token of affiliation. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 41(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810701691123

- Teding van Berkhout, E., & Malouff, J. M. (2016). The efficacy of empathy training: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000093

- *Thrasher, A. D., Golin, C. E., Earp, J. A., Tien, H., Porter, C., & Howie, L. (2006). Motivational interviewing to support antiretroviral therapy adherence: The role of quality counseling. Patient Education and Counseling, 62(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.003

- *Tollison, S. J., Lee, C. M., Neighbors, C., Neil, T. A., Olson, N. D., & Larimer, M. E. (2008). Questions and reflections: The use of motivational interviewing microskills in a peer-led brief alcohol intervention for college students. Behavior Therapy, 39(2), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2007.07.001

- *Tollison, S. J., Mastroleo, N. R., Mallett, K. A., Witkiewitz, K., Lee, C. M., Ray, A. E., & Larimer, M. E. (2013). The relationship between baseline drinking status, peer motivational interviewing microskills, and drinking outcomes in a brief alcohol intervention for matriculating college students: A replication. Behavior Therapy, 44(1), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2012.09.002

- *Town, J. M., Hardy, G. E., McCullough, L., & Stride, C. (2012). Patient affect experiencing following therapist interventions in short-term dynamic psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 22(2), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2011.637243

- *Tryon, G. S. (2003). A therapist's use of verbal response categories in engagement and nonengagement interviews. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 16(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951507021000050168

- *Villarosa-Hurlocker, M. C., O'Sickey, A. J., Houck, J. M., & Moyers, T. B. (2019). Examining the influence of active ingredients of motivational interviewing on client change talk. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 96, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2018.10.001

- +Voutilainen, L. (2012). Responding to emotion in cognitive psychotherapy. In A. Peräkylä & M.-L. Sorjonen (Eds.), Emotion in interaction (pp. 235–255). Oxford University Press.

- +Voutilainen, L., Peräkylä, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2010). Recognition and interpretation: Responding to emotional experience in psychotherapy. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 43(1), 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351810903474799

- *Wampold, B. E., & Kim, K.-h. (1989). Sequential analysis applied to counseling process and outcome: A case study revisited. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(3), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.36.3.357. [reanalysis of Hill et al., 1983].

- Weinrach, S. G. (1990). Rogers and Gloria: The controversial film and the enduring relationship. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 27(2), 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.27.2.282

- +Weiste, E. (2015). Describing therapeutic projects across sequences: Balancing between supportive and disagreeing interventions. Journal of Pragmatics, 80, 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2015.02.001

- +Weiste, E., & Peräkylä, A. (2013). A comparative conversation analytic study of formulations in psychoanalysis and cognitive psychotherapy. Research on Language & Social Interaction, 46(4), 299–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2013.839093

- +Weiste, E., & Peräkylä, A. (2014). Prosody and empathic communication in psychotherapy interaction. Psychotherapy Research, 24(6), 687–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.879619

- Weiste, E., Voutilainen, L., & Peräkylä, A. (2016). Epistemic asymmetries in psychotherapy interaction: Therapists’ practices for displaying access to clients’ inner experiences. Sociology of Health & Illness, 38(4), 645–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12384

- Wilson, D. B. (2021). SPSS meta-analysis macro. Computer software. http://mason.gmu.edu/~dwilsonb/MetaAnal.html.

- *Wiser, S., & Goldfried, M. R. (1998). Therapist interventions and client emotional experiencing in expert psychodynamic–interpersonal and cognitive–behavioral therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(4), 634–640. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.634

- +Wu, Y. (2019). Empathy in psychotherapy: Using conversation analysis to explore the therapists’ empathic interaction with clients. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 37(3), 232–246. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2019.1671881

- +Wynn, R., & Wynn, M. (2006). Empathy as an interactionally achieved phenomenon in psychotherapy: Characteristics of some conversational resources. Journal of Pragmatics, 38(9), 1385–1397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2005.09.008