ABSTRACT

Objective: Although theorists and researchers have stressed the importance of rupture resolution episodes for successful treatment process and outcome, little is known about patients’ retrospective reflections about rupture resolution. Aim: The overarching goal of the present study was to use a mixed-method approach to examine patients’ retrospective reflections on the frequency, types, and consequences of rupture resolution episodes and the association between rupture resolution episodes and patients’ attachment orientation and treatment outcome. Method: Thirty-eight patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) were interviewed, on average three years after termination, about their experiences of ruptures in short-term dynamic psychotherapy. Results: Thirty patients reported having experienced at least one rupture, with patients who showed less improvement in depressive symptoms more likely to report having had a rupture. Ruptures were judged as having been successfully resolved for 13 of these patients; suggesting that patients with a high level of attachment anxiety were less likely to be judged as having had a successful resolution. Patients whose ruptures were successfully resolved with the therapist's help reported better treatment process and outcome than patients whose ruptures were not successfully resolved. Conclusion: Results highlight the importance of hearing patients’ perspectives on ruptures, rupture resolution, and treatment outcome.

Clinical and methodological significance of this article: The study demonstrated that for most patients, rupture and rupture resolution episodes were still remembered years after the treatment ended. The results of our study support the importance of therapists being attuned to and aware of these rupture events, since they can significantly influence the process and outcome of treatment.

Alliance ruptures have been defined as deterioration or tension in the alliance, manifested by a disagreement between the patient and therapist on treatment goals or tasks or a strain in their emotional bond (Bordin, Citation1979). These ruptures might manifest as a major break in therapy or as a minor tension between the patient and therapist (Safran & Muran, Citation2000). According to the theoretical and empirical literature on rupture resolution processes, such ruptures can serve as a key element in the treatment process and outcome if they are successfully resolved (Muran et al., Citation2009; Muran & Barber, Citation2011; Safran & Muran, Citation2000). Successful resolutions are defined as resuming collaboration on the work of therapy by employing resolution strategies, such as changing the task or exploring the rupture and what underlies it (Eubanks et al., Citation2018). Indeed, the resolution process is thought to be the critical ingredient that makes the alliance curative (Safran & Muran, Citation2000; Zilcha-Mano, Citation2017). Because the patient's retrospective reflections about rupture resolution have received little attention in the literature, our overall purpose in the present study was to explore how patients recall their experiences of ruptures and rupture repairs.

In a recent meta-analysis, patients who were able to resolve their ruptures with the help of their therapists were found to have had better treatment outcome than patients without ruptures or with unresolved ruptures (Eubanks et al., Citation2018). Moreover, unresolved ruptures were associated with a poor treatment process (Coutinho et al., Citation2011), poor treatment outcomes (Zlotnick et al., Citation2020), and a greater risk of treatment dropouts (Eubanks et al., Citation2019). Relatedly, negative consequences were found in qualitative studies of misunderstandings and impasses (Hill et al., Citation1996; Rhodes et al., Citation1994).

Based on self-report measures, patients reported that ruptures occurred in between 25% to 68% of treatment sessions (Muran, Citation2019), whereas the rate was 91% to 100% when assessed on an observer-based system (Muran, Citation2019). When examining resolution reports from patients’ self-reported measures, the prevalence ranged from 15% to 80% (Muran, Citation2019). Thus, there was a difference in prevalence between patient and observer reports, perhaps because the wide range of definitions of both rupture and repair makes it difficult to compare across studies. Whereas patients’ reports of ruptures and repairs right after the sessions are commonly collected in research, the retrospective memory of ruptures and repairs has not yet been examined.

Asking patients about their memories retrospectively might help us understand what contributes to long-term outcomes and “what sticks” or becomes part of the inner representations or internalizations of patients. However, memory is complex, and the amount in which a memory is accurate is very controversial (Coon et al., Citation2016) since memories are very subjective and influenced by various factors such as emotions, expectations, and biases (Coon et al., Citation2016; Tyng et al., Citation2017). Despite its complexity, psychotherapists work on a daily basis with patients’ subjective memories and life stories (Singer et al., Citation2013), and therefore, the subjective memory and unique narrative that patients consolidate and internalize as their treatment experiences might have a meaningful influence on their long-term treatment outcome.

Researchers have used semi-structured interviews to examine patients’ reflections about significant moments in treatment (e.g., corrective relational experiences, Huang et al., Citation2016; therapist self-disclosure, Audet, Citation2011), what patients value most in treatment and what they believe to have facilitated change (Levitt et al., Citation2006; Wucherpfennig et al., Citation2020), and what patients and therapists agree to have been helpful in treatment and its relationship with treatment outcome (Chui et al., Citation2020). In most of these studies, patients reported that the therapeutic alliance was one of the factors that facilitated change or were significantly helpful in treatment (Chui et al., Citation2020; Levitt et al., Citation2006; Wucherpfennig et al., Citation2020). However, little is known about patients’ inner experiences of the repair of alliance ruptures.

In addition, it makes sense to look for the moderators of rupture resolution. One likely candidate is attachment orientation. Given that the rupture and repair process reflects patients’ struggles in relationships that theoretically echo their initial relationships with caregivers(Safran & Muran, Citation2000), it seems reasonable to assume that a secure attachment would be associated with the ability to negotiate a rupture repair process (Miller-Bottome et al., Citation2019). Indeed, patients’ attachment orientations were found to be related to reports on rupture resolution episodes, such that therapists reported a higher frequency of ruptures with preoccupied attachment patients (Eames & Roth, Citation2000), while insecure patients were less likely to report successful resolutions (Miller-Bottome et al., Citation2019). In addition, since patients’ internal narratives and memories of treatment experiences are shaped by the patients’ internal working models (Bowlby, Citation1969, Citation1982), which reflect beliefs and expectations from self and others (Singer et al., Citation2013), it seems important to understand if patients’ attachment orientation is correlated with how they internalize and reflect on ruptures.

Therefore, the first purpose of the present study was to qualitatively investigate patients’ reports on ruptures and rupture resolutions in terms of frequency, types, intensity, and consequences. The second purpose was to associate rupture resolutions with outcome: We hypothesized that those patients who report successful resolutions of alliance ruptures would report more positive consequences for the therapeutic process and outcome compared with those who report unsuccessful resolutions.

Our third and fourth purposes in the present study were to quantitatively examine whether patients’ reports on ruptures and resolution in terms of rupture report, rupture intensity, and successful resolutions were related to patients’ attachment orientation and to treatment outcome (reduction of depressive symptoms). We hypothesized that patients with high levels of attachment anxiety or attachment avoidant orientation would be more likely to report major ruptures and that their ruptures would be less likely to be successfully resolved. Additionally, we hypothesized that those patients who showed more improvement in their depressive symptoms during treatment would be less likely to report a major rupture and that what ruptures they did report would be more likely to be successfully resolved. We used a mixed-method approach to get a complete picture of the phenomena of rupture resolution episodes and to learn about patients’ internalizations of their relationship with the therapist over time.

Method

Dataset

Patients in the current study were a subset of patients in the pilot and active phase of a randomized controlled trial (RCT; Zilcha-Mano et al., Citation2018) for MDD. All participants provided written informed consent before joining the study.

Participants

There were 38 participants (28 women, 10 men; 31 Jewish, 3 Christian, 1 Muslim, 1 Atheist; 27 single, 10 married, 1 divorced/widowed; 29 employed, 9 unemployed; 2 with a high school education, 4 with some college, 12 undergraduate students, 14 with a graduate degree, and 6 with post-graduate degrees; average age 30.79, SD = 7.57 years).Footnote1

There were 8 therapists (5 women, 3 men; all Jewish; years of clinical experience: M = 11.00, SD = 6.1). All had formal training and at least five years of experience in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Before seeing patients, therapists attended a 20-hour training workshop in supportive and expressive psychodynamic techniques and engaged in weekly individual and group supervision throughout the study. The therapists’ median caseload for the current study was 5 (range 1–9).

A 49-year-old Jewish male post-doctoral licensed clinical psychologist (man), a 30-year-old Jewish doctoral clinical psychology student (woman), a 26-year-old Jewish master's clinical psychology student (woman), and two undergraduate psychology majors (a 24-year-old Christian woman and a 28-year-old Jewish man) served as interviewers after participating in intensive training. All the interviewers, except the post-doctoral licensed clinical psychologist, also served as judges in the qualitative analysis. A 46-year-old Jewish female post-doctoral licensed clinical psychologist (woman) and a 73-year-old non-religious female licensed psychologist (woman) served as auditors.

Measures

The Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR; Brennan et al., Citation1998) is a widely-used 36-item self-report measure assessing adult general attachment orientation. The measure examines two primary dimensions: Avoidance, the extent to which people are uncomfortable opening up to others and depending on them (e.g., “I feel uncomfortable when other people want to be close to me”), and Anxiety, which reflects the extent to which people tend to worry about attachment-related concerns (e.g., “I find that my partner(s) don't want to get as close as I would like”) (Brennan et al., Citation1998; Fraley et al., Citation2000). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree); high scores reflect high avoidance or anxiety attachment levels. Adequate psychometric properties, including test-retest reliability and construct validity, have been demonstrated for the ECR (Brennan et al., Citation1998). Recent studies have also provided support for the ECR’s validity, given the association with similar constructs such as personal problems (Lopez & Gormley, Citation2002) and ineffective coping strategies (Wei et al., Citation2003, Citation2006). High internal consistency reliabilities of >.90 for both subscales have been reported in the past (Brennan et al., Citation1998; Ehrlich et al., Citation2014; Wei et al., Citation2007) and for the present study (.92 for Avoidance, .90 for Anxiety).

The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, Citation1967) is a 17-item clinically-administered measure assessing the severity of depression by examining the existence and severity of different symptoms associated with depression during the past week. The HRSD is known as a gold standard measure for depression (Cusin et al., Citation2010; Lamb et al., Citation2005; Worboys, Citation2013). Reports from previous studies suggest adequate convergent validity (Bagby et al., Citation2004) and high inter-rater reliability rates (M = .93) (Trajković et al., Citation2011). For the present study, the ICC among the 12 interviewers was .98.

The original semi-structured post-therapy interview protocol was developed revising the Knox et al. (Citation2012) interview protocol by changing and deleting some of the questions (See S3). We also added questions from the Post-session Questionnaire (PSQ; Muran et al., Citation1992, Citation2009) regarding the occurrence of rupture resolution episodes in the treatment (i.e., “Did you experience any tension or problem, any misunderstanding, conflict or disagreement, in your relationship with your therapist during the therapy?”). Our revised protocol included questions regarding patients’ overall treatment experiences, struggles in interpersonal relationships, corrective relational experiences, rupture resolution episodes, and what the patient wished the therapist had done differently (see Appendix).

Procedures

Treatment

As a part of the RCT (Zilcha-Mano et al., Citation2018), patients received 16 50-minute weekly sessions of supportive-expressive treatment (Luborsky et al., Citation1995), a time-limited psychodynamic treatment adapted for depression, either in a supportive-focused condition or in a supportive-expressive-focused condition. Upon completion of the active phase of treatment, the treating therapist provided four monthly follow-up sessions.

Patients completed the ECR at intake. The HRSD was administered at intake and after every session by trained evaluators (advanced undergraduate, graduate, and PhD students in clinical psychology).

Patients’ recruitment to the post-Therapy interview

We contacted all patients who had completed the active and follow-up stages of treatment (20 treatment sessions) by the time we conducted the study, and invited them to participate in the interview. Patients were contacted based on their entry order into the trial and represented the entire sample.

The mean time between the final session and the post-therapy interview was 3.09 (SD = 1.24, Range = 0.73–4.93) years. Of the 64 patients invited to participate in post-therapy interviews, 14 did not answer our calls and messages, and 9 declined the invitation to participate. Hence, 82% of patients who answered our calls agreed to participate in the current study. Of the 41 who agreed to participate, 3 canceled the interview or stopped answering our calls, yielding a final total of 38 patients (59% of the original sample) who completed the interviews.

Interviews

Before conducting the interviews, the four judges and first auditor discussed their personal biases regarding psychotherapy (i.e., “personal issues that make it difficult for researchers to respond objectively to the data,” Hill et al., Citation1997, p. 539). In this discussion, the four judges shared their beliefs that successful treatment is characterized by positive changes in patients’ well-being, whereas the auditor thought that successful treatment is when the patient and therapist work together to achieve treatment goals. Three of the four judges and the auditor believed that the RCT treatment was generally effective (one of the judges was new to the team and did not have an opinion).

In terms of expectations (i.e., “beliefs that researchers have formed based on reading the literature and thinking about and developing the research questions,” Hill et al., Citation1997, p. 538), all judges and the auditor believed that successful resolutions of alliance ruptures would be related to better treatment outcomes; two thought that unresolved ruptures would be related to poor treatment outcomes and treatment dropouts. In the discussion about what best facilitates successful rupture resolution, about half of the team specified patient or therapist characteristics and therapeutic techniques, whereas the other half focused on characteristics of the dyad, such as the level of working alliance. It is important to note that our research team, which conducted and coded the interviews, had not been trained as Rupture Resolution Rating System coders (3RS; Eubanks et al., Citation2015), but they had read about the theoretical concept of ruptures.

For training, interviewers read transcripts of several interviews and then listened to three audio recordings of past or pilot interviews. They also conducted a simulation interview with an experienced interviewer.

The post-therapy interviews were conducted virtually and were videotaped and recorded. The average length of the interviews was 51 min (SD = 17.24). Interviewers conducted a median of 6 (range of 2–19) interviews for the current study. For the five cases with more than one rupture (four patients reported two ruptures, and one reported three), we asked patients to discuss the most salient rupture for them. If they were unable to describe just one event (two patients), the research team later selected what we considered to be the most salient based on the patient report (rupture type and intensity) and by reaching a consensus. Patients were given code numbers to protect confidentiality.

Consensual qualitative research (CQR) coding

Judges completed 22 h of training, which consisted of reading about CQR (Hill, Citation2012) and rupture resolution (Eubanks et al., Citation2015, Citation2018; Safran & Muran, Citation2000). Judges were asked not to analyze interviews if they recognized the patient (two judges recognized two different patients and were not part of the judgment procedure for those interviews).

We followed the general procedures outlined for CQR (Hill, Citation2012; Hill et al., Citation2005; Hill & Knox, Citation2021) for all the steps of CQR. More specifically, we carefully followed the data collection and analysis process described in Huang et al. (Citation2016).

The first and second authors created a list of domains (i.e., topic areas) based on the research questions and relevant literature. The team revised this domain list after reviewing several transcripts and continued revising throughout the process.

After independently coding sections of the transcripts of the first eight interviews into domains, the judges met and consensually agreed upon the coding into domains. Judges then independently constructed core ideas (i.e., summaries in more concise terms) for the raw data in each domain for the eight interviews, which were reviewed by the entire consensus team. The auditor checked the domain coding and the core ideas. The auditor and judges discussed the suggestions, and then the judges revised the domains and core ideas.

After constructing core ideas for the first eight interviews, judges then independently started to develop preliminary categories that reflected themes within domains across cases. Then, judges discussed their ideas and reached a consensus about a list of categories. The auditors reviewed the categories and provided feedback, which was considered in the final revision of the cross analysis.

The primary coding process for the first eight interviews was conducted in Word. After this step, we started to use the Atlas.ti software (9.0.7.) a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software package (CAQDAS). The four judges entered all 38 transcripts into the software (including those that were already coded using Word), constructed core ideas, and selected suitable categories from the category lists. Revisions were made to domains, core ideas, and categories as we refined the cross-analyses and wrote the manuscript. The final list was: (a) a description of the rupture, (b) a description of the resolution, (c) in-session consequences of rupture resolution, (d) out-of-session consequences of rupture resolution, and (e) other.

Classification of ruptures and repairs

When asked about experiencing any tension or problem, any misunderstanding, conflict or disagreement in their relationship with the therapist during the therapy, any moment that patients reported as challenging or uncomfortable was considered to be a rupture. As noted earlier, only one rupture was included for each case. The final sample was thus 30 patients, each with one rupture, and eight patients without a rupture.

We coded rupture occurrence (Yes or No for the 38 cases) and then further subdivided the cases into major/high intensity and minor/low intensity/no rupture based on patients’ reports in the post-therapy interview (for the 38 cases). We did this comparison based on previous literature regarding the PSQ (Muran et al., Citation2009), where a rupture is considered to be a substantial rupture when a rupture intensity item is rated with a score of 2 or above. We also coded successful vs. unsuccessful resolutions for the 30 rupture cases. We followed patients’ answers to the question: “To what degree do you feel this problem was resolved?” (see Appendix). If the patient answered that they felt that this problem was resolved, we considered the case as a successful resolution. If the patient's answer was ambivalent, the interviewers asked them further questions to get more clarity about the rupture resolution process. If the answer to this question was missing, we removed the patient from the analyses (N = 1).

Quantitative Data Collection and Analyses

We conducted three separate logistic regressions examining whether patients’ attachment orientation (e.g., Avoidant and Anxious, each as continuous variables) predicted rupture occurrence, rupture intensity, and rupture resolution (all dichotomous variables), controlling for time since the end of treatment to the post-therapy interview. We also did three separate logistic regressions examining whether HRSD Δ (i.e., change in patient's levels of depressive symptoms, calculated for each patient as pre HRSD rates minus post HRSD rates) predicted rupture occurrence, rupture intensity, and rupture resolution (all dichotomous variables), controlling for time since the end of treatment to the post-therapy interview. We used one-level logistic regression analyses because every patient had only one observation of each variable and we had eight therapists in our study, which is below the suggested minimum level of clusters for the estimation of random effects (Snijders & Bosker, Citation2011). All analyses were conducted using R software (Team, Citation2020).

Results

Qualitative Data

Following CQR guidelines, general refers to categories that emerged for all or all-but-one patient (29–30 patients), typical to more than half up to the cut-off for general (16–28 patients), variant to two up to the cut-off for half (3–15 patients), and rare to 2 patients. Data that emerged for only one patient were dropped or combined into other categories. See for the results. We provide quotes from the interviews, with ellipses (…) where words were deleted to facilitate the flow of the narrative.

Table I. Categories and subcategories for domains for ruptures and successful resolution of ruptures.

Of the 38 cases, patients typically (30, 79%) reported at least one rupture. For example, P26 said there were “some incidents where I was talking about something and felt that the therapist was bored and not interested in me. His facial expressions made me feel this. That led me to stop talking and explaining about some topics.”

Types of ruptures

There were three variant types of ruptures. The first involved a disagreement on treatment tasks. These ruptures involved challenging moments related to conversation topics, therapist suggestions, and the amount of feedback desired from the therapist. For example, P22 said, “I wanted to talk about a specific topic, but the therapist led the conversation in another direction. I was angry because of that, but I didn't say anything to him.” P7 said, “When the therapist wanted to reflect on what I said, it bothered me, especially when she did that again and again and tried to connect between things after I thought that I had already understood.”

The second variant type of rupture (with three variant subcategories) involved strains in the bond with their therapist. In the first subcategory, patients reported having difficulty opening up to or connecting with the therapist (e.g., for P5, “There were times when I was talking and talking but feeling that I can't say what I want and feeling disconnected from the therapist”). In the second subcategory, patients felt dismissed by the therapist (e.g., P32 said, “I felt that the therapist was trying to analyze what I said and also attack me because of it [what I said].”). In the third subcategory, patients wished the therapist had been more attuned. For P17,

I talked about something that occurred at work, and I had to explain to the therapist some technical things. It happened several times, and I was angry because I wanted him to remember these things about my work and in general to remember what I struggle with and what is challenging for me.

The third variant rupture type involved feelings of discomfort related to the therapeutic setting, such as the cameras being present. Included in this type were moments when the patient was afraid to talk about an awkward or a sensitive topic, moments of silence, and feelings of discomfort. For example, P3 said, “I wanted to talk about sexuality. It was inconvenient. I wanted to bring it up, but I felt a certain exposure, not to mention the cameras.” Another patient [P4] was “really afraid of the fact that the sessions were recorded and videotaped … I talked about very private and sensitive topics, and after that, it took me a few sessions to feel safe and comfortable again.”

Rupture intensity

Ruptures were typically categorized as major (i.e., high in intensity, N = 17). For P24, “There was an intense tension, I remember bouncing my legs and my fingers, I simply wanted to run away.” Other ruptures were variantly categorized as minor (i.e., low in intensity, N = 13), involving smaller disagreement or tension. For P35, “I wasn't angry or something likewise, it just wasn't a pleasant moment but overall, it was okay.”

Rupture type by rupture intensity

We also compared the intersection of rupture types and rupture intensity, using a criterion established by Hill and Knox (Citation2021) that groups had to differ by 30%. In contrast to the minor intensity group, the major intensity group was categorized as experiencing more strains in the emotional bond (56% vs. 8%). Discomfort ruptures were more often categorized as minor than major (100% vs. 0%). Groups did not differ in disagreement on treatment tasks.

Therapist strategies used to resolve ruptures

Of the 30 patients who reported a rupture, we categorized 14 (variant) as not being successfully resolved, 13 (variant) as having been discussed and successfully resolved with the help of the therapist, and two as having successfully resolved the rupture on their own without the help of the therapist (e.g., P3 said, “I wanted to talk about sexuality. It was inconvenient. I wanted to bring it up, but I felt a certain exposure … However, I managed to overcome my feelings of embarrassment and awkwardness alone and brought up this subject”), and one was missing data about the resolution due to technical problems in that the recording stopped in the middle of the interview (see ). We first present data across all the first three groups and then compare the first two groups.

Table II. Domains and categories for resolution strategies and consequences.

Of the 28 patients (excluding the two who resolved the rupture on their own), patients variantly reported that the therapist changed treatment tasks according to the patient's needs to facilitate a resolution to a rupture. For example, P1 said, “The therapist saw that I wasn't ready to talk about this and that it was hard for me, so she talked about other things.” P28 said, “In the moments I was silent, the therapist paid attention to that and said that it's okay not to talk about this and navigated the conversation to other topics.”

Patients also variantly reported that the therapist helped the patient explore the rupture and gain some understanding regarding interpersonal problems that led to the rupture. For P12,

The therapist offered me a new way to think about my need to look for practical tools from others rather than looking for emotional aspects and said that she thinks that I was looking for practical tools because it was easier for me to refer to certain topics in a practical way, rather than in an emotional way, which makes me feel weaker.

In the next session I brought this [the rupture] up and we talked about it together, about what I felt and why. We talked about it in-depth and it gave me some new understanding on what I tend to do (…) then everything was okay and continued as usual.

The third variant was the therapist validating the patient's experience. For example, P4 said, “The therapist understood my fear of sharing personal information when being filmed and calmed me down by explaining that the recordings were very secure and that only the research team would have access to it.” P31 said, “The therapist validated my feelings about silence and said to me that the silence is okay, so I shouldn't be afraid of it and that it's a part of the treatment. For me, it legitimized the moments of silence.”

The fourth variant involved the therapist apologizing and clarifying a misunderstanding in the context of ruptures. For P23, “She was very nice and explained to me why we are talking about this and apologized that it was not comfortable for me.” For P6, “The therapist then took responsibility for our misunderstanding in a most respectful way.”

We then compared the strategies used by therapists in the resolved and unresolved groups (note that the two patients who resolved the rupture on their own without the help of the therapist were not included in this comparison). For the cases that were resolved with the help of the therapist, general was 12–13, typical 6–12, and variant 2–6. Only one patient from the unresolved group reported on a resolution strategy (e.g., P20 said: “she [the therapist] was very nice and tried to validate my feelings on our forced ending (due to the RCT format) … I believed she was trying to help, but it was not helpful for me”).

Consequences

Consequences were divided into in-session and outside-session. We first describe consequences across the total sample, and then compare the “resolved with therapist's help” group and “unresolved” group (see ).

For the total sample (N = 29), the most common (albeit variant) in-session consequence was “no consequence”. The other two in-session consequences (both variant) were “improved therapeutic relationship” (e.g., P6 said, “It brought us closer together and strengthened our relationship; P2 reported, “After that I felt that the therapist is really there with me and for me. I was going home after each session and waiting for the following one”), and “negatively affected therapeutic relationship” (e.g., P38 said, “This led to a certain distrust. I understood that apparently, I will not get what I hoped for;” P13 said, “It made me doubt the effectiveness of the treatment and to think that there is something weird about it.”).

The most common (albeit variant) outside-session consequence was “no consequence”, followed by a variant category of “broadened perspective” (e.g., P33 said, “I managed to understand my behavior in different situations and think about them from a different point of view, like my ability to experience moments of silence or to cope with a certain situation”), another variant of “returning to old patterns” (e.g., For P37, “I remember feeling again in other relationships that I am disappointing the other side as I felt with her [the therapist]”), and a final variant of “reflected on the rupture” (e.g., For P21, “It made me think about what I need in treatment and my general need in active feedback and direction”).

The patients who were judged as having successfully resolved the ruptures with the help of the therapist, more often than those with unresolved ruptures, reported improved therapeutic relationships (46% vs. 7%) in terms of in-session consequences and more often reported a broadened perspective (38% vs. 7%) in terms of outside-session consequences. No differences were found for other categories using the 30% criterion.

Quantitative Results

The mean and standard deviation of all quantitative variables are presented in .

Table III. Means and standard deviations for HRSD delta and attachment orientation.

Preliminary analysis

We found no significant differences in treatment outcome and alliance scores between the group of patients who agreed versus those who did not agree to participate in the post-therapy interview (See S1).

Pre-treatment attachment orientation as a moderator

We did not find a significant relationship between patients’ attachment orientation (Anxiety or Avoidant) and whether or not they reported a rupture (Avoidant; b = −.07, SE = .37, t(34) = −.2, p = .84, ηp 2 < .001, Anxiety; b = −.42, SE = .38, t(34) = −1.1, p = .27, ηp 2 = .03) or of rupture intensity (Avoidant; b = −.11, SE = .31, t(34) = −.36, p = .71, ηp 2 < .001 Anxiety; b = −.49, SE = .33, t(34) = −1.48, p = .13, ηp 2 = .06).

The relationship between successful resolutions of ruptures (Yes vs. No) and attachment Anxiety, b = −.09, SE = .48, t(23) = −1.91, p = .055, ηp 2 = .15, had a large effect size (according to Cohen, Citation1988) but did not reach significance, suggesting that patients with higher attachment anxiety were less likely to report that ruptures were successfully resolved. The relationship between successful resolutions and attachment avoidant orientation was not significant, b = .33, SE = .38, t(23) = .86, p = .38, ηp 2 = .05.

Change in depression as a moderator

We found a significant negative relationship, b = −.18, SE = .09, t(35) = −1.99, p = .046, ηp 2 = .11, between rupture reports in the post-therapy interview and HRSD Δ. Hence, patients who did not report a rupture had greater reduction in depression during treatment.

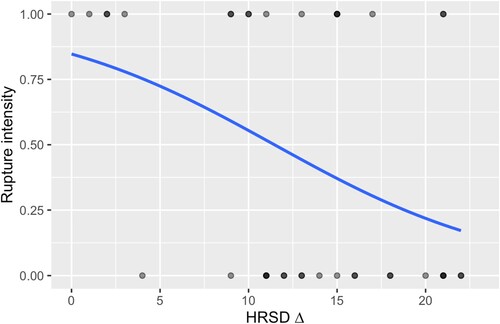

We also found a significant negative relationship (b = −.14, SE = .06, t(35) = −2.18, p = .02, ηp 2 = .16) between rupture intensity reports and HRSD Δ. Hence, patients who reported that they had a major rupture showed less reduction in depression during treatment (See ). We did not find a significant relationship (b = .06, SE = .06, t(24) = 0.96, p = .33, ηp 2 = .03) between successful resolutions and HRSD Δ. Hence, patients who reduced their depressive symptomatology did not report a rupture or reported on a more minor rupture than major ruptures, but there were no differences in distal outcome between those who successfully resolved the ruptures and those who did not.

Figure 1. Predicting patients’ reports on rupture intensity in the post-therapy interview by HRSD Δ. Note: HRSD Δ = Hamilton change levels during treatment (i.e., reduction of depressive symptoms, intensity = 0 – no rupture or only minor, 1 – major rupture).

We repeated all analyses using two-level hierarchical logistic regression with patients nested within therapists. We found similar results and concluded that our results were not affected by the therapist effect (see S2).

Discussion

In this mixed-method study of 38 patients who had participated in supportive or supportive-expressive treatment for depression, 30 (79%) reported the occurrence of a rupture in their treatment. This number is relatively high compared with patients’ reports on ruptures with self-report methods (25–68%), but relatively low when compared with observer-based methods (91–100%; Muran, Citation2019), both following the session. The observer-based method uses an external coder who does not take an active part in the dyad, while the self-reported measures are filled by the patient (who takes an actual part in the dyad) and therefore might be more emotionally involved in these episodes. We speculate that when patients retrospectively look back over the entire treatment, it may be emotionally easier to reflect on the sessions and remember one significant rupture during the entire treatment, rather than recall a particular rupture occurring in a specific session.

The first type of rupture was a disagreement on the tasks of treatment, most often related to the topics discussed and the amount of feedback given by the therapist. The second type involved strains in the emotional bond, with patients feeling that therapists were not sufficiently attuned to their needs, feeling dismissed by therapists, or having difficulty opening up and connecting with therapists. The third type involved feelings of discomfort, embarrassment, or awkwardness related to discussing certain topics in treatment. Similarly, minor ruptures mostly involved a slight or temporary discomfort, which often arose at the beginning of treatment before the therapeutic relationship was solidly established, but they were clearly remembered years later. When such ruptures arise in the relationship with the therapist, they may be crucial to the process of treatment and have an effect on the patient's self-esteem or feeling that the treatment is a secure place (Mallinckrodt, Citation2010).

Patients recalled four types of strategies used more frequently by therapists in resolved cases: Therapists changed what they were doing, validated patients’ experiences, explored the rupture to help the patient gain insight into relational patterns, and apologized and clarified the misunderstanding. Similarly, Eubanks et al. (Citation2015) suggested that therapists explicitly acknowledge their contribution to the rupture and link the rupture to larger interpersonal patterns, and Rhodes et al. (Citation1994) identified that apologizing and clarifying misunderstanding was related to resolutions of misunderstandings in treatment.

In terms of consequences, when patients reported a successful resolution of alliance rupture, they also reported that there were improvements in the therapeutic relationship. In contrast, when ruptures were not successfully resolved, patients reported negative effects on the treatment and the therapeutic relationship. These findings align with the large body of literature and empirical findings that emphasize the importance of successful rupture resolution processes for better treatment outcome (Eubanks et al., Citation2018; Muran et al., Citation2009; Muran & Barber, Citation2011).

It is important to note, however, that about a third of the patients across all cases reported no consequences of the ruptures. Given that these patients stayed in treatment, these ruptures may not have been serious. In addition, it might be that these ruptures were simply remembered as less meaningful to the treatment as a result of an emotional “fading”. Moreover, it is possible that when ruptures were repaired and the dyad resumed collaboration on treatment tasks, patients felt like these moments were more a “return to homeostasis” that did not have a meaningful impact.

Interestingly, two patients reported that they had managed to overcome their ruptures without the help of their therapists and that the rupture resolution episodes had positive consequences. This surprising, although rare, type of “self-sufficient repair” is, as far as we know, not known to research and is one of the benefits of qualitative research, which allows us to discover new options that were not theoretically driven. We might speculate that perhaps the memory of being able to repair a rupture alone in a meaningful way is part of the narrative of their (successful) therapy. It might be connected to growing self-agency and a sense of control, which are important issues, especially for people with depression.

We also studied the moderating effect of patients’ initial attachment orientation on the process and outcome of ruptures. We found a suggestion that patients who were initially anxiously attached reported less successful resolutions in the post-therapy interview. Similarly, Miller-Bottome et al. (Citation2019) found that patients with secure attachment were more likely to report successful resolutions in the Post-Session Questionnaire (PSQ; Muran et al., Citation1992, Citation2009), although Ben David-Sela et al. (Citation2021) did not find this relationship when using the Eubanks et al. (Citation2015) Rupture Resolution Rating System to measure successful resolutions. Notably, the three studies used different measures and methods, which might have led to the different findings.

In addition, in the quantitative analyses we found no significant relationships between rupture reports and rupture intensity and attachment orientation, whereas Eames and Roth (Citation2000) found that the frequency of ruptures was related to patients’ preoccupied attachment orientations. Our findings suggest that a patient's pre-treatment attachment orientation might be related to the way patients can openly share and collaborate in rupture resolution episodes, including bringing up a difficulty with the therapist and actively working on it. This finding aligns with literature on similar concepts, such as immediacy, which was found to be more useful with secure patients (Hill et al., Citation2014).

In terms of the quantitative associations with outcome, patients who reported a rupture, and especially patients’ with major ruptures, had worse outcomes in terms of depression. However, we did not find a significant relationship between reports of successful resolutions and reduction of depressive symptoms through treatment. The findings regarding the relationship between ruptures and outcome are consistent with the literature regarding unresolved ruptures (Muran et al., Citation2009; Muran & Barber, Citation2011), but are in contrast to the literature that the occurrence of rupture resolution episodes is related to good treatment outcomes (Eubanks et al., Citation2018; Safran & Muran, Citation2000). Given that prior researchers found that ruptures occur in almost every session (Muran, Citation2019), it is interesting to speculate why the patients who had better treatment outcomes did not remember a rupture in the treatment when they were interviewed after therapy. It is possible to speculate that patients who had a positive treatment experience were more likely to remember the entire treatment as a whole, coherent, “positive” experience.

Strengths and Limitations

The large sample size was a strength for the qualitative analyses, although the sample size was small for the quantitative analyses, which might affect the ability to detect meaningful changes. Moreover, the sample of this study was relatively homogenous (all patients had 16 sessions of short-term psychodynamic treatment, all suffered from a major depressive disorder and did not drop out of treatment), which is a strength in terms of making sense of the qualitative data but is also a limitation in terms of generalizing to other treatment approaches and clinical populations. For example, the fact that all patients suffered from major depressive disorder might have made them more vulnerable in relationships and, therefore, more alert to ruptures in the alliance. In addition, rupture reflections could have a greater impact on patient treatment narratives when patients drop out of treatment. In this type of therapy (i.e., supportive or supportive-expressive psychodynamic psychotherapy), the therapeutic relationship and alliance are important, yet therapists do not focus directly on alliance ruptures and repairs. In that sense, it might be similar to other psychodynamic or interpersonal psychotherapies, including therapy in a naturalistic setting.

Moreover, it is important to note that only 59% of the original sample of patients actually participated in the current study, although when looking at the patients that did answer our calls (50), 82% of patients agreed to participate in the current study. Additionally, there were no differences in treatment outcome, in terms of reduction of depressive symptoms, and therapeutic alliance scores between those who actually participated in the post-therapy interview and those who did not. It is possible that patients who participated in the current study had better treatment experiences.

Another major strength of the current study was our focus on patients’ retrospective reflections, which can shed light on patients’ memories about the therapeutic relationship. But the retrospective nature of the data is also a limitation given that subjective factors might have influenced patients’ memory, such as different events that patients experienced in the time gap between the end of treatment and the interview, such as being at different levels of functioning.

In addition, our team's familiarity with the 3RS coding system might have enriched our understanding of the phenomenon but also might have narrowed our perspective about what to look for. Lastly, another strength is the use of CQR, a rigorous method with a heterogeneous group of judges that met weekly to discuss each interview and reach consensus.

Implications

Our results demonstrate the importance of therapists attuning to rupture events, since they may have a meaningful impact on the therapeutic process and outcome. Furthermore, it is especially important for therapists to pay attention to ruptures for anxiously attached patients.

This study also yields implications for training. Given the importance of rupture resolutions, therapists should be trained to be aware of the signs of ruptures, rupture repairs, and attachment orientation, and to be professional in working to repair ruptures, hopefully resulting in a better treatment experience and outcome.

This research also demonstrates the importance of combining qualitative and quantitative methods to gain a more complete understanding of the complexity of ruptures. When looking only from the quantitative point of view, it seems that the reports on ruptures in the post-therapy interview were related to poor treatment outcomes. However, when considering the qualitative point of view and patients’ reports on their perception of the consequences of these episodes, it seems that, when ruptures were successfully resolved, they had a very meaningful impact on patients. The differences between the qualitative and quantitative findings may be because we had a relatively small sample for quantitative analysis so that there was not enough “power” to detect significant results. Moreover, it is possible that there was heterogeneity in the way that rupture resolution processes related to results, and that heterogeneity made it hard to capture the complexity of the relationship through quantitative analysis.

Future researchers could examine whether other patient characteristics (e.g., personality disorder, insight levels) might influence the way that patients perceive rupture resolution episodes. Moreover, it would be interesting to compare patients’ retrospective reflections regarding rupture resolution episodes when they received relational treatment that focused on these moments, versus when there was no such focus. In addition, future research is needed on the impact of measurement, given the differences found between self-report versus observers and post-session versus retrospective reports.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2023.2245128.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Diversity is distributed based on the minority/non-minority religion division, according to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (Central Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016), the division into ethnic (Krieger & Crahan, Citation2001).

References

- Audet, C. T. (2011). Client perspectives of therapist self-disclosure: Violating boundaries or removing barriers? Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 24(2), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2011.589602

- Bagby, R. M., Ryder, A. G., Schuller, D. R., & Marshall, M. B. (2004). The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale: Has the gold standard become a lead weight? American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(12), 2163–2177. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2163

- Ben David-Sela, T., Dolev-Amit, T., Eubanks, C. F., & Zilcha-Mano, S. (2021). Achieving successful resolution of alliance ruptures: For whom and when? Psychotherapy Research, 31(7), 870–881. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1862432

- Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16(3), 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085885

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Volume I: Attachment. In attachment and loss: Volume I: Attachment. The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

- Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(4), 664–678. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x

- Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. Guilford Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-36873-002

- Central Bureau of Statistics. (2016). Population group.

- Chui, H., Palma, B., Jackson, J. L., & Hill, C. E. (2020). Therapist–client agreement on helpful and wished-for experiences in psychotherapy: Associations with outcome. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(3), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000393

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed., Vol. 2). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

- Coon, D., Mitterer, J. O., & Martini, T. S. (2016). Psychology: Modules for active learning. Cengage Learning.

- Coutinho, J., Ribeiro, E., Hill, C., & Safran, J. (2011). Therapists’ and clients’ experiences of alliance ruptures: A qualitative study. Psychotherapy Research, 21(5), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2011.587469

- Cusin, C., Yang, H., Yeung, A., & Fava, M. (2010). Rating scales for depression. In L. Baer, & M. Blais (Eds.), Handbook of clinical rating scales and assessment in psychiatry and mental health (pp. 7–35). Humana Press.

- Eames, V., & Roth, A. (2000). Patient attachment orientation and the early working alliance—a study of patient and therapist reports of alliance quality and ruptures. Psychotherapy Research, 10(4), 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptr/10.4.421

- Ehrlich, K. B., Cassidy, J., Lejuez, C. W., & Daughters, S. B. (2014). Discrepancies about adolescent relationships as a function of informant attachment and depressive symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(4), 654–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12057

- Eubanks, C. F., Lubitz, J., Muran, J. C., & Safran, J. D. (2019). Rupture resolution rating system (3RS): Development and validation. Psychotherapy Research, 29(3), 306–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2018.1552034

- Eubanks, C. F., Muran, J. C., & Safran, J. D. (2015). Rupture resolution rating system (3RS): Manual. Unpublished Manuscript, Mount Sinai-Beth Israel Medical Center, New York, NY.

- Eubanks, C. F., Muran, J. C., & Safran, J. D. (2018). Alliance rupture repair: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 508–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000185

- Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350

- Hamilton, M. A. X. (1967). Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 6(4), 278–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x

- Hill, C. E. (2012). Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. American Psychological Association.

- Hill, C. E., Gelso, C. J., Chui, H., Spangler, P. T., Hummel, A., Huang, T., Jackson, J., Jones, R. A., Palma, B., & Bhatia, A. (2014). To be or not to be immediate with clients: The use and perceived effects of immediacy in psychodynamic/interpersonal psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 24(3), 299–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.812262

- Hill, C. E., & Knox, S. (2021). Essentials of consensual qualitative research. American Psychological Association.

- Hill, C. E., Knox, S., Thompson, B. J., Williams, E. N., Hess, S. A., & Ladany, N. (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 196. https://epublications.marquette.edu/edu_fac/18

- Hill, C. E., Nutt-Williams, E., Heaton, K. J., Thompson, B. J., & Rhodes, R. H. (1996). Therapist retrospective recall impasses in long-term psychotherapy: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(2), Article 207. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.43.2.207

- Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25(4), 517–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000097254001

- Huang, T. C.-C., Hill, C. E., Strauss, N., Heyman, M., & Hussain, M. (2016). Corrective relational experiences in psychodynamic-interpersonal psychotherapy: Antecedents, types, and consequences. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000132

- Knox, S., Hess, S. A., Hill, C. E., Burkard, A. W., & Crook-Lyon, R. E. (2012). Corrective relational experiences: Client perspectives. In L. G. Castonguay & C. E. Hill (Eds.), Transformation in psychotherapy: Corrective experiences across cognitive behavioral, humanistic, and psychodynamic approaches (pp. 191–213). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13747-011

- Krieger, J., & Crahan, M. E. (2001). The Oxford companion to politics of the world. Oxford University Press.

- Lamb, R. W., Michalak, R. W., & Swinson, R. P. (2005). Assessment scales in depression, mania and anxiety. Depression and Anxiety, 22(1), 45–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20120

- Levitt, H., Butler, M., & Hill, T. (2006). What clients find helpful in psychotherapy: Developing principles for facilitating moment-to-moment change. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(3), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.314

- Lopez, F. G., & Gormley, B. (2002). Stability and change in adult attachment style over the first-year college transition: Relations to self-confidence, coping, and distress patterns. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49(3), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.49.3.355

- Luborsky, L., Mark, D., Hole, H. V., Popp, C., Goldsmith, B., & Cacciola, J. (1995). Supportive-expressive dynamic psychotherapy of depression: A time-limited version (pp. 41–83). Basic Books. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-98051-001

- Mallinckrodt, B. (2010). The psychotherapy relationship as attachment: Evidence and implications. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27(2), 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509360905

- Miller-Bottome, M., Talia, A., Eubanks, C. F., Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2019). Secure in-session attachment predicts rupture resolution: Negotiating a secure base. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 36(2), 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/pap0000232

- Muran, J. C. (2019). Confessions of a New York rupture researcher: An insider’s guide and critique. Psychotherapy Research, 29(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1413261

- Muran, J. C., & Barber, J. P. (2011). The therapeutic alliance : an evidence-based guide to practice. Guilford Press.

- Muran, J. C., Safran, J. D., Gorman, B. S., Samstag, L. W., Eubanks-Carter, C., & Winston, A. (2009). The relationship of early alliance ruptures and their resolution to process and outcome in three time-limited psychotherapies for personality disorders. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(2), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016085

- Muran, J. C., Safran, J. D., Samstag, L. W., & Winston, A. (1992). Patient and therapist postsession questionnaires, Version 1992. Beth Israel Medical Center.

- Rhodes, R. H., Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Elliott, R. (1994). Client retrospective recall of resolved and unresolved misunderstanding events. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41(4), 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.41.4.473

- Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Resolving therapeutic alliance ruptures: Diversity and integration. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(2), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200002)56:2<233::AID-JCLP9>3.0.CO;2-3

- Singer, J. A., Blagov, P., Berry, M., & Oost, K. M. (2013). Self-defining memories, scripts, and the life story: Narrative identity in personality and psychotherapy. Journal of Personality, 81(6), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12005

- Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (2011). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling. Sage.

- Team, R. C. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Version 4.0. 2 (Taking Off Again). R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Trajković, G., Starčević, V., Latas, M., Leštarević, M., Ille, T., Bukumirić, Z., & Marinković, J. (2011). Reliability of the Hamilton Rating Scale for depression: A meta-analysis over a period of 49 years. Psychiatry Research, 189(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.12.007

- Tyng, C. M., Amin, H. U., Saad, M. N. M., & Malik, A. S. (2017). The influences of emotion on learning and memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8: Article 1454. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01454

- Wei, M., Heppner, P. P., & Mallinckrodt, B. (2003). Perceived coping as a mediator between attachment and psychological distress: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(4), 438–447. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.4.438

- Wei, M., Heppner, P. P., Russell, D. W., & Young, S. K. (2006). Maladaptive perfectionism and ineffective coping as mediators between attachment and future depression: A prospective analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.67

- Wei, M., Russell, D. W., Mallinckrodt, B., & Vogel, D. L. (2007). The experiences in close relationship scale (ECR)-short form: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 88(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890701268041

- Worboys, M. (2013). The Hamilton Rating Scale for depression: The making of a “gold standard” and the unmaking of a chronic illness, 1960–1980. Chronic Illness, 9(3), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395312467658

- Wucherpfennig, F., Boyle, K., Rubel, J. A., Weinmann-Lutz, B., & Lutz, W. (2020). What sticks? Patients’ perspectives on treatment three years after psychotherapy: A mixed-methods approach. Psychotherapy Research, 30(6), 739–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1671630

- Zilcha-Mano, S. (2017). Is the alliance really therapeutic? Revisiting this question in light of recent methodological advances. American Psychologist, 72(4), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040435

- Zilcha-Mano, S., Dolev, T., Leibovich, L., & Barber, J. P. (2018). Identifying the most suitable treatment for depression based on patients’ attachment: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of supportive-expressive vs. Supportive treatments. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), Article 362. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1934-1

- Zlotnick, E., Strauss, A. Y., Ellis, P., Abargil, M., Tishby, O., & Huppert, J. D. (2020). Reevaluating ruptures and repairs in alliance: Between-and within-session processes in cognitive–behavioral therapy and short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(9), 859–869. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000598

Appendix

Post-Therapy Interview Protocol

What brought you to therapy?

Were there also interpersonal struggles that brought you to therapy?

Can you please tell me more about it?

Did any changes occur to these interpersonal struggles over the course of your psychotherapy or since your psychotherapy?

Overall, how did you feel about your therapy experience?

Now we're interested in your relationship with the therapist. Let's talk about times you felt a distinct shift, such that you came to understand or experience your relationship with the therapist in an unexpected or different way that was ultimately very positive. Clarification may be needed. (If none, go on to question #5).

Approximately when in the therapy did this event/moment occur?

What was going on in therapy prior to that event/moment?

What made that event/moment positive? Meaningful? Unexpected?

What happened in the therapy/your relationship with the therapist as a result of that event/moment?

What changed for you as a result of that event/moment? It may have helped you with understanding something about your interpersonal relationships.

Now let's talk about challenging moments in your relationship with the therapist. Did you experience any tension or problem, any misunderstanding, conflict or disagreement, in your relationship with your therapist during the therapy? If yes:

Please describe this moment/event.

How did you feel during that moment/event?

Please rate how tense or upset you felt about this moment/event during the session?

What was going on in therapy prior to that moment?

Did you or the therapist talk about this moment? If not, why didn't you talk about it?

How did you move on from that event?

To what degree do you feel this problem was resolved?

What happened in the therapy/your relationship with the therapist as a result of that event/moment?

What changed for you as a result of that event/moment?

What do you think the therapist had done that helped you in therapy?

What do you wish the therapist would have done differently in your therapy?

Can you think about a metaphor or a short sentence that describes/summarizes the therapy?

Are there things I didn't ask about that you expected me to ask?

How was your experience participating in this interview?