Abstract

Objective

Group cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for social anxiety disorder (SAD) is effective, but little data exist on generic relational components of the therapeutic process, such as group cohesion and therapy alliance, and central CBT-specific components such as homework engagement, beliefs, and perceived consequences. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationships between homework, group cohesion, and working alliance during group CBT for social anxiety disorder.

Method

Participants (N = 105) with SAD engaged in 12 sessions of group CBT. Measures of homework, working alliance, and group cohesion were completed at multiple points throughout treatment. Random-intercept cross-lagged panel models were used to evaluate the prospective relationships between measures.

Results

Prospective relationships between the homework outcomes did not vary throughout the treatment period, with the only significant relationships seen between the random intercepts (“trait” levels). Homework beliefs were a significant negative predictor of future group cohesion, but only in mid- to late-treatment. Homework consequences and working alliance were significantly and positively predictive of each other throughout therapy.

Conclusion

Early homework engagement is associated with higher engagement throughout therapy. Working alliance and homework engagement are important to bolster early in group CBT.

Trial registration: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry identifier: ACTRN12616000579493..

Clinical Significance of This Article

Higher early homework engagement was associated with higher subsequent homework engagement in individuals who completed group cognitive behaviour therapy for social anxiety disorder, so early homework engagement is important. Beliefs that homework tasks are understood, have a clear rationale, and match with therapy goals were negatively associated subsequent group cohesion, indicating that when homework is highly valued as an important mechanism of change then perceptions of cohesion may be subsequently lower. Experiencing homework consequences of mastery over progress and problems was reciprocally related with working alliance throughout therapy, indicating that successful homework engagement is associated with stronger alliance (and vice versa).

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is characterized by a debilitating fear and apprehension of negative evaluations from others, resulting in severe anxiety before, during, and after social situations (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for SAD is explicitly designed to challenge and diminish fear of negative evaluation and has been associated with large effect sizes (e.g., McEvoy, Hyett, et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, a noteworthy proportion of individuals fail to respond to this treatment, underscoring the imperative for additional investigation into factors predictive of treatment outcomes (McEvoy et al., Citation2012; McEvoy et al., Citation2015; Stein et al., Citation2017; Struhldreher et al., Citation2014).

Considerable evidence supports the efficacy of both individual and group CBT for social anxiety (Barkowski et al., Citation2016). Group and individual CBT encompass working alliance as a relational factor, but group CBT includes the additional relational factor of group cohesion (Kazantzis & Dobson, Citation2022; Norton & Kazantzis, Citation2016). These factors are likely to play a crucial role in facilitating change, working in tandem with specific CBT techniques that are implemented within and between sessions. For instance, increased engagement in homework assignments between sessions, which constitutes a central element of CBT involving clients applying treatment principles to their own life context, has been linked to improved treatment outcomes (see Beck, Citation2011; Kazantzis, Citation2021; Ryum et al., Citation2023). However, there is limited research exploring the reciprocal relationships between the relational aspects of group CBT and homework engagement, a gap that holds potential significance in optimizing treatment outcomes (Kazantzis, Dattilio et al., Citation2017). Understanding these relationships becomes particularly relevant in the context of treating Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD), given the heightened interpersonal sensitivity often associated with the disorder.

Previous investigations into the relationships among working alliance, group cohesion, homework engagement, and treatment outcomes have yielded inconclusive results (McEvoy, Bendlin et al., Citation2023). Some studies have failed to establish a significant association between working alliance and outcomes in the context of CBT for social anxiety (e.g., Calamaras et al., Citation2015; Draheim & Anderson, Citation2019; Hoffart et al., Citation2012; Jazaieri et al., Citation2018; Mortberg, Citation2014). Conversely, others have identified a positive correlation between a stronger working alliance and improved treatment outcomes later in the therapy process (Haug et al., Citation2016). Similarly, the literature on group cohesion's impact on group CBT for SAD is mixed. Some studies have reported a significant positive relationship between higher group cohesion and better treatment outcomes (e.g., Mululo et al., Citation2012; Taube-Shiff et al., Citation2007), while others have found no such association (e.g., Woody & Adessky, Citation2002). Additionally, increased homework engagement has been linked to improved outcomes in group CBT for SAD (Leung & Heimberg, Citation1996), but other research has failed to establish a predictive relationship between homework completion and treatment outcomes (Edelman & Chambless, Citation1995).

Enhancing our understanding of the reciprocal relationships between factors such as working alliance, group cohesion, and homework engagement may offer insights into these disparities. For instance, if the working alliance plays a pivotal role in fostering homework engagement, which subsequently positively affects treatment outcomes, then the impact of the working alliance on outcomes may be indirect and observable primarily in studies where there are well-integrated, engaging, and collaborative homework tasks aligned with clients’ treatment objectives (Kazantzis, MacEwan et al., Citation2005). Furthermore, it is plausible that group cohesion fosters strong social norms regarding high or low homework engagement. Alternatively, some individuals with social anxiety might derive benefits from the group cohesion as it provides a context in which they can challenge their expectations of negative evaluation from others, while other clients may find greater value in homework assignments conducted outside of therapy sessions (Kazantzis, Dattilio et al., Citation2017).

In light of the mixed findings regarding the significance of the working alliance, group cohesion, and homework in their relation to treatment outcomes in group CBT for SAD, McEvoy, Bendlin et al. (Citation2023) conducted an investigation into these factors over time within the context of group CBT for SAD. Their study revealed a significant association between group cohesion and social anxiety symptoms at the conclusion of the treatment, whereas no significant relationship with the working alliance was observed. Previous research has suggested that the working alliance might exert an indirect influence on social anxiety during treatment (e.g., Hoffart et al., Citation2012), implying that the alliance might facilitate improved outcomes rather than directly contribute to them. For instance, it is plausible that a stronger working alliance leads to greater engagement with homework assignments, which, in turn, leads to improved outcomes.

Notably, greater engagement with homework was found to predict lower social interaction anxiety, but this relationship was only evident during the middle phase of group treatment (McEvoy, Bendlin et al., Citation2023). Further research is now needed to explore different components of homework to shed light on why this relationship manifested during the middle phase of treatment. Given the results of this recent study on homework engagement and relational factors such as group cohesion and the working alliance (McEvoy, Bendlin et al.), it would be valuable to examine two other major components of homework, namely beliefs and consequences of homework, as predictors of homework engagement. A more comprehensive understanding of how the working alliance and group cohesion predict homework engagement could provide insights into the intricate interplay among these variables in group CBT for social anxiety. As argued by Dobson (Citation2021), research on homework has evolved beyond a focus on adherence to encompass more complex relationships, including those with the working alliance (see also Kazantzis & Dobson, Citation2022; Strunk et al., Citation2021). Therefore, it is essential to investigate the relationship between the working alliance and homework engagement.

The primary objective of the present study was to expand upon McEvoy, Bendlin et al.'s (Citation2023) recent investigation by examining how elements of the therapeutic relationship, specifically the group cohesion and working alliance, are associated with homework engagement during group CBT for social anxiety. Our approach was guided by Kazantzis and Miller's (Citation2022) comprehensive model, which draws on behavioural and cognitive determinants of engagement with homework. This model emphasizes three key stages: (a) collaborative homework design, involving the formulation of specific hypotheses about the potential benefits for the client; (b) homework planning; and (c) homework review in the subsequent session, which includes addressing the client's perceived difficulties and obstacles in engaging with the homework. These factors collectively constitute the construct of “homework engagement” (see also McEvoy, Bendlin et al., Citation2023). Therefore, the model and associated practice guidelines recommend that therapists focus on a clinically meaningful understanding of “engagement” with homework, rather than narrowly concentrating on quantity or quality of adherence (Holdsworth et al., Citation2014; Kazantzis et al., Citation2016; Neimeyer et al., Citation2008).

Client evaluations of their skill mastery and progress resulting from homework are theoretically crucial determinants of engagement (J. S. Beck, Citation1995; J. S. Beck & Tompkins, Citation2007; Kazantzis & L'Abate, Citation2005). Numerous research groups have demonstrated the value of assessing client appraisals of homework using the Homework Rating Scale – Revised (HRS-II; Kazantzis, Deane, et al., Citation2005) to study their relationship with treatment outcomes (Helbig & Fehm, Citation2004; McDonald & Morgan, Citation2013; Sachsenweger et al., Citation2015; Yew et al., Citation2021; Zelencich et al., Citation2020, and see a systematic review in Kazantzis, Brownfield, et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, the present study assessed client appraisals of homework and levels of engagement using the HRS-II.

The overarching aim of this study was to investigate the relationships between homework, group cohesion, and working alliance during group CBT for SAD. Our first hypothesis was that beliefs and consequences related to homework would significantly predict homework engagement. Our second hypothesis was that group cohesion would significantly predict homework engagement. Our third hypothesis was that working alliance would also significantly predict homework engagement.

Method

Design

Data were from a randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing standard and imagery enhanced CBT for social anxiety (McEvoy, Hyett et al., Citation2022). Data were combined across the two conditions, given there were no significant differences on treatment outcome across the groups (McEvoy, Hyett et al., Citation2022).

Participants

The participants were 105 individuals (50.5% male; mean age 28.6 years, age range 18-72, SD = 11.36) who completed group CBT at the Centre for Clinical Interventions, Perth. The inclusion criteria were over 18 years or above, stable psychotropic medication for one month prior to study engagement, and diagnosis of social anxiety disorder on the Structured Clinical Interview (First et al., Citation2015) for DSM-5 (APA, Citation2013). Exclusion criteria were bipolar disorder, psychosis, substance use disorder, high suicide risk and current CBT for social anxiety. Most participants were of Anglo/European (88.3%) or Asian (7.8%) cultural backgrounds. Further details of the RCT and treatment conditions can be found in McEvoy, Hyett et al (Citation2022).

Measures

Gross Cohesiveness Scale (GCS; Stokes, Citation1983). The GCS is a 9-item measure of group cohesion (e.g., “How many of the group members fit what you feel to be the ideal of a good group member?”) and was administered at treatment sessions 4, 7 and 10. The 9-point rating scale ranges from 0 to 8. The internal consistency was acceptable, McDonalds omega = .80.

Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Horvath & Greenberg, Citation1989). The short form revised version of the 12-item WAI (Hatcher & Gallaspy, Citation2006) measured alliance between client and therapist, and the scale was answered at treatment sessions 3, 6 and 9. The WAI instructs respondents to “mentally insert the name of your therapist in place of _____ in the text.” This allowed clients to rate how aligned they felt with their co-therapists overall, rather than each co-therapist separately. The 5-point Likert scale ranges from 1 = seldom to 5 = always. The internal consistency was good, McDonalds omega = .88.

Homework Rating Scale-Revised (HRS-II; Kazantzis et al., Citation2005). The HRS-II assesses client engagement with homework in CBT in the context of the practical obstacles experienced, and difficulties encountered in attempting the homework (Kazantzis & Miller, Citation2022). The HRS-II was administered at treatment sessions 2, 5, 8 and 11 in the present study. All subscales were used following an examination of the item performance in the present sample, and consistent with a recent study of CBT for depression (N = 50, Yew et al., Citation2021), items 3, 4, 7, 8, and 10 of the HRS-II were excluded on the basis of low inter-item correlations in our sample. HRS-II subscales included homework engagement (items 1 and 2 assessing quantity and quality, respectively), homework beliefs (items 5, 6, and 9, assessing comprehension of homework activities, clarity on the rationale for the activity, and match with therapy goals, respectively), and homework consequences (11 and 12, assessing mastery over problems and progress, respectively). All items are assessed on a 5-point scale (0-4), meaning the two-item scale score can range from 0 to 8 and a three-item scale score can range from 0 to 12. The three HRS-II subscales showed acceptable internal consistency: Engagement ω = .77, Beliefs ω = .69, Consequences ω = .78.

Procedure

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE 87_2016) and the North Metropolitan Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee for Mental Health (approval number 04_2016). The trial was pre-registered on the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12616000579493). Eligible participants completed the 12-session group treatment (see McEvoy, Hyett et al., Citation2022 for further details of treatment content) and group sizes varied from 6 to 11 clients. Groups were facilitated by two therapists who were masters- or doctoral-level clinical psychologists trained in the protocols and who received weekly supervision (see McEvoy, Hyett et al., Citation2022, for more details). Demographic details of the therapists were not coded in the database. The two conditions did not significantly differ on the WAI, GCS and HRS-II (McEvoy, Hyett et al., Citation2022). From session 2 onwards, all sessions began with a homework review, followed by new content and homework setting for the subsequent week. The GCS (sessions 4, 7, 9), WAI (sessions 3, 6, 9), and HRS (sessions 2, 5, 8, 11) were administered at timepoints designed to capture early, mid, and late therapy processes. They were not all administered at the same sessions to reduce client burden.

Statistical Analysis

Random-intercept cross-lagged panel models (RI-CLPM) were used to investigate reciprocal and prospective associations between the variables at multiple time points. The RI-CLPM allows for separating stable between-person relationships from the time-varying within-person relationships, reducing spurious significant findings (Hamaker, Kuiper, & Grasman, Citation2015). Three models were estimated (one for each aim):

Homework Outcomes

Homework Outcomes & Group Cohesion

Homework Outcomes & Working Alliance

Note that while three models are estimated there are no relationships for which we interpret the null hypothesis more than once – each aim is evaluated separately within each model, and so there is no increase to our Type 1 error rate.

MPlus version 8.10 (Muthen & Muthen, Citation2017) was used with robust maximum likelihood estimation to account for non-normality. Missing data was accounted for through full information maximum likelihood. Evaluation of model fit was assessed through the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). Good fit was judged as TLI > .90, CFI > .95 and RMSEA < .07 (Bentler, Citation1990; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Steiger, Citation2007). To assess the statistical power of this approach, a Monte Carlo simulation was conducted in Mplus. When assuming average autoregressive effects between successive time points of .60, and direct effects of predictors on subsequent symptoms of .40 and an alpha of .05, the sample size of 105 participants provided 80% power for direct effects and 73% power for indirect effects (.16).

Two sensitivity analyzes were also performed. To assess whether the clustered nature of group-delivered CBT impacted the results, the models were re-estimated with clustered bootstrapping for 10000 bootstrapped samples and the bootstrapped bias-corrected confidence intervals inspected. To assess the appropriateness of collapsing the two treatment groups in the analyzes, multiple-groups RI-CLPM with clustered bootstrapping were estimated. The multiple-groups models assess whether model fit significantly deteriorates when constraining the model parameters to equality between treatment groups. As the sample size in each group could not support the full models, instead all pairwise combinations of measures were estimated separately (for a total of nine models). The Mplus inputs and outputs for all models are provided online in the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/bhv98/

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Data were available at each time point for between 68 to 88 clients due to non-attendance, but data from all clients were used in the analyzes. As seen in , working alliance and group cohesion increased during the course of therapy. The three homework subscales did not show any consistent change, with all fluctuating throughout the treatment period.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for working alliance, group cohesion and homework over treatment.

Model 1: Homework Outcomes

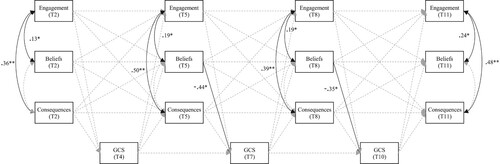

Model 1 showed good fit to the data: χ2(48) = 64.76, p = .054; RMSEA = .06 [.00, .10]; CFI = .95; TLI = .93. The model identified no significant prospective relationships between any of the homework outcomes (see and ). However, the random intercepts (between-individual “trait” variation) of the three outcomes were significantly positively correlated (see ). This indicates that the increases/decreases in a given homework outcome at a single timepoint were not predictive of any of the homework outcomes at the following timepoint. Rather, it was only the average “trait” levels of each of the outcomes throughout the treatment period that were related.

Table 2. Model 1 auto-regressive and cross-lagged estimates.

Table 3. Model 1 random intercept variances & correlations.

Model 2: Group Cohesion

Model 2 showed borderline fit to the data: χ2(76) = 112.19, p = .004; RMSEA = .07 [.04, .10]; CFI = .92; TLI = .89. Inspection of modification indices showed misfit was present due to assuming the same relationship between group cohesion and homework beliefs in both early and late treatment. When allowing the early treatment relationships between group cohesion and homework beliefs to differ from late treatment, the model showed good fit: χ2(74) = 95.96, p = .044; RMSEA = .06 [.01, .09]; CFI = .95; TLI = .93. The model identified a significant prospective relationship from homework beliefs (treatment sessions 5 and 7) to mid- to late-treatment group cohesion (treatment sessions 7 and 10, respectively; see and ). This indicates that, in the latter half of treatment, a 1 SD increase in an individual’s belief in the understanding, clarity and match to therapy goals of their homework resulted in their group cohesion being 44% of a SD smaller at the next assessment. Note that this prospective relationship was not reciprocal – there was no significant relationship between changes in group cohesion and future homework beliefs.

Figure 2. Model 2: Random-intercept cross-lagged panel model of homework outcomes and group cohesion.

Table 4. Model 2 auto-regressive and cross-lagged estimates: group cohesion.

Model 3: Working Alliance

Model 3 showed good fit to the data: χ2(76) = 97.80, p = .047; RMSEA = .06 [.01, .09]; CFI = .96; TLI = .94. The model identified significant prospective relationships between working alliance and homework consequences (mastery over progress and problems; see ). These relationships were also reciprocal. For example, early in therapy 1 SD increase in working alliance was associated with an individual’s rating of homework consequences being 36% of an SD higher at the following assessment. Similarly, a 1 SD increase in an individual’s rating of homework consequences was associated with their working alliance rating being 20% of an SD higher at the next assessment (see ).

Figure 3. Model 3: Random-intercept cross-lagged panel model of homework outcomes and working alliance.

Table 5. Model 3 auto-regressive and cross-lagged estimates: working alliance.

Sensitivity Analyzes

The clustered bootstrapping models identified that all estimates presented above did not have bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence that contained 0 (i.e., no effect). However, there were a small number of estimates with demonstrated significant p-values that did have bootstrapped confidence intervals containing 0. These estimates have been marked in the relevant table.

The multiple-groups (clustered bootstrapped) models identified no significant changes in model fit when constraining the growth parameters to equality between the treatment groups. This implies that it was appropriate to collapse the treatment groups for the present analysis. These results and all Mplus outputs are provided in the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/bhv98/

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationships between homework, group cohesion, and working alliance during group CBT for SAD. Our first hypothesis was that homework beliefs and consequences would significantly predict homework engagement, which was supported. The results indicated that while changes in homework beliefs and consequences were not predictive of future levels of homework engagement, there was a stable “trait” level relationship between homework engagement and homework beliefs and consequences. Our second hypothesis was that group cohesion would significantly predict homework engagement, which was not supported. Group cohesion did not predict future homework engagement. In contrast, homework beliefs were significantly and negatively predictive of future group cohesion, but this effect only became evident mid- to late-therapy. Our third hypothesis was that working alliance would also significantly predict homework engagement, which was also not supported. However, we did observe a bidirectional predictive relationship between working alliance and homework consequences.

The finding of a stable, trait level relationship between homework engagement, beliefs, and consequences provides support for the Kazantzis and Miller (Citation2022) model, which emphasizes the role of appraisals of homework as correlates of engagement. Although group cohesion and working alliance were not directly associated with homework engagement, their relationships with other aspects of homework (homework beliefs and consequences) were consistent with Kazantzis and Miller’s (Citation2022) model by providing evidence of the interplay between working alliance, group cohesion, and client homework appraisals. Additionally, these findings support the concept of the CBT process as comprising therapeutic techniques and in-session processes, such as the integration of homework, within a relational context (see Huibers et al., Citation2021; Strunk et al., Citation2021).

A practical implication of these findings is that individuals who have a clear understanding of the value of homework tasks and derive benefits from them are more likely to engage in homework tasks, and vice versa. These aspects of homework engagement do not appear to fluctuate significantly during treatment within individuals. Therefore, it is critical from the outset of treatment to ensure that clients have a clear rationale for homework, that homework tasks align closely with their treatment goals, and that tasks are collaboratively designed and implemented as early as possible in treatment (Kazantzis & Miller, Citation2022). Additionally, therapists should facilitate clients experiencing early success in gaining perceived mastery over homework techniques and progress toward their goals.

Homework engagement encompasses both the quantity and quality of adherence to homework, taking into account obstacles and task difficulties (Kazantzis & Miller, Citation2022). Meta-analyzes of CBT for anxiety have consistently shown that the quantity and quality of homework completion significantly predict treatment outcomes (Kazantzis et al., Citation2010, Citation2016). Therefore, clinicians should prioritize optimizing engagement. Clinicians can emphasize the importance of homework engagement by assessing and monitoring it, along with clients’ beliefs, during the first four weeks of CBT for anxiety disorders using the HRS-II (Kazantzis, Citationin press). Early identification of low engagement allows for prompt intervention through strategies that enhance positive appraisals of homework, such as greater collaboration and clarification (e.g., highlighting potential benefits of homework tasks and empiricism). Furthermore, clinicians can increase positive beliefs about homework by soliciting more extensive feedback from clients regarding the consequences of homework and by designing homework tasks that are likely to boost confidence, competence, and other positive outcomes related to the client's goals as early in treatment as possible (Hudson & Kendall, Citation2005; Ryum et al., Citation2023; Yew et al., Citation2021).

Group cohesion was unrelated to future homework engagement, beliefs, and consequences, but homework beliefs relating to comprehension, clarity, and matching of homework to therapy goals were associated with future group cohesion from mid- to late- therapy. Interestingly, this relationship was negative, such that higher homework beliefs were associated with less group cohesion or, conversely, lower homework beliefs was associated with higher group cohesion. The whole group implemented similar techniques for homework (e.g., cognitive reappraisal, behavioural experiments), including some within-session tasks that were set for homework for the whole group (e.g., reviewing recordings of their own within-session presentations to challenge self-images), which may be expected to strengthen group cohesion. However, most homework tasks were individualized to align with each participant’s therapy goals, so the outcomes of each task may be seen as less relevant to other members and may therefore weaken cohesion. This intriguing effect may indicate that by mid-treatment clients who comprehend and have clarity over the purpose of homework, and for whom homework matches their therapy goals, the role of the group process may have reduced in perceived cohesion. For these individuals, homework tasks may be seen as the principal mechanism through which they believe they will meet their goals, with the group process being perceived as secondary and less cohesive.

Conversely, for clients who do not understand the relevance of the homework to their problems, group cohesion may be subsequently perceived more highly and thus the relational aspects of group CBT may be more highly valued. Our previous work with the same sample found that higher group cohesion was associated with lower fear of negative evaluation social anxiety symptoms late in therapy. We also found a reciprocal relationship between homework and fear of negative evaluation, whereby higher homework engagement by mid-treatment (total HRS scores, session 5) was associated with subsequent lower fear of negative evaluation (session 8), which, in turn was associated with higher homework engagement later in therapy (session 11, McEvoy et al., Citation2023). Therefore, on average, both group cohesion and homework engagement appear to be associated with cognitive and/or emotional shifts during CBT for SAD. McEvoy et al. (Citation2023) did not, however, include group cohesion and homework engagement in the same model, and they did not investigate each aspect of homework engagement separately. The dissociation between homework and cohesion in the current study, reflected by the negative association between homework beliefs and subsequent group cohesion, points to the possibility that relational and technical aspects of therapy being somewhat separable and differentially important vehicles for change for different individuals. It therefore may be important for clinicians to facilitate both homework engagement and group cohesion so that both processes can work to optimize outcomes for all clients. This possibility requires further research.

Working alliance predicted future homework beliefs (mastery and progress) throughout therapy and this relationship was reciprocal. This finding indicates that stronger working alliance is associated with higher perceptions of mastery and progress from homework, and higher levels of mastery and progress from homework are associated with stronger future working alliance. Clients therefore appear to hold more positive beliefs about important components of CBT, such as a belief that homework will benefit them, if they have a stronger working relationship. Together with evidence that homework engagement (Kazantzis et al., Citation2010, Citation2016) and working alliance (Dobson, Citation2021) directly improve outcomes, the current findings underscore the importance of clinicians enhancing working alliance to improve outcomes directly and indirectly via homework. Importantly, positive outcomes from homework may also be an important mechanism through which to strengthen working alliance. Therefore, for clinicians who have difficulty establishing early alliance, particularly with clients with social anxiety disorder, successful homework tasks may be an active and experiential strategy for strengthening the therapist-client relationship.

The results should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, there is the possibility that socially desirable responding may have biased responses on the homework scales. Individuals may have responded more positively about homework tasks, or over-emphasised their level of engagement, to avoid perceived negative judgements. Second, the length of time between assessments may have been too great for the analysis to identify dynamic relationships over shorter periods of time. That is, prospective relationships between measures may only exist on a week-to-week basis, such that these influences have already “washed out” by the next assessment time point in the current study. Moreover, the within-individual effects we did detect may be specific to the timepoints during which each measure was administered, and may not be generalizable to other timepoints. Third, there are general limitations of cross-lagged panel analysis. Sorjenen and Melin (Citation2023) have outlined evidence that cross-lagged effects may often be spurious due to regression to the mean and correlations with residuals (Castro-Schilo & Grimm, Citation2018; Eriksson & Haggstrom, Citation2014; Sorjenen et al., Citation2019). Hence, the results should be viewed with the context of limitations of cross-lagged panel analysis. Fourth, although full information maximum likelihood was used to account for missing data so that all participants’ data could be used, future research with larger sample sizes would enable smaller effects to be detected. Fifth, participants rated alliance with respect to their co-therapists, rather than each co-therapist separately. It is unclear whether assessing alliance separately for each therapist, and then using average, strongest, or weakest alliance, would have yielded different findings (McEvoy et al., Citation2023). Finally, the strengths of the relationships investigated in this study could be moderated by a range of client characteristics (e.g., gender, cultural background, co-occurring diagnoses), and therapist characteristics and behaviours, which should be investigated in future studies that are sufficiently powered to detect potential effects.

In summary, our findings emphasize the importance of engaging clients with successful homework as early and as collaboratively as possible in therapy. In addition to previous evidence indicating that homework engagement is associated with improved treatment outcomes (Kazantzis et al., Citation2010, Citation2016; McEvoy et al., Citation2023), our findings further indicate that successful engagement in homework is associated with stronger therapeutic alliance, which, in turn, is associated with higher homework mastery over problems and progress. Interestingly, clients who understand the rationale and benefits of homework and who see homework tasks as being aligned with their therapy goals by mid-treatment perceive lower subsequent group cohesion. Clients who have less clarity over homework tasks tend to report stronger group cohesion. Although further work is required, this intriguing finding suggests that different individuals may derive benefit from the relational and homework components of group CBT for social anxiety disorder.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

McEvoy receives royalties from Guilford Press (Imagery-Enhanced CBT for Social Anxiety Disorder). Kazantzis disclosed his royalties from Guilford Press (Therapeutic Relationship in Cognitive Behavior Therapy; Cognitive and Behavior Theories in Clinical Practice), Routledge (Using Homework Assignments in Cognitive Behavior Therapy); SpringerNature publishers (CBT: Science into Practice Book Series; Handbook of Homework Assignments in Psychotherapy: Research, Practice, & Prevention). The other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Data Sharing

Trial data from the randomized clinical trial is available in an open-access repository, Research Data Australia (see https://researchdata.ands.org.au/).

Author Contribution Statement

McEvoy was the lead author who obtained funding, designed the study, co-ordinated data collection, analysis, data interpretation, writing and editing of the manuscript. Johnson conducted data analysis, data interpretation and contributed to writing the manuscript. Kazantzis consulted on the design, data interpretation, and contributed to writing and editing of the manuscript. Egan contributed to data interpretation,wrote the first drafts of the manuscript, and contributed to editing the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the clinicians at the Centre for Clinical Interventions, Perth, Western Australia, who facilitated the interventions: Mark Summers, Melissa Burgess, Bruce Campbell, Samantha Bank, Adelln Sng, Olivia Carter, and Louise Pannekoek. The contributions of authors to the randomized controlled trial who were also grant awardees are also acknowledged: Lisa Saulsman, Michelle Moulds, Jessica Grisham, Emily Holmes, David Moscovitch, Ottmar Lipp and Ron Rapee.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Barkowski, S., Schwartze, D., Strauss, B., Burlingame, G. M., Barth, J., & Rosendahl, J. (2016). Efficacy of group psychotherapy for social anxiety disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 39, 44–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.005

- Beck, J. S. (1995). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. Guildford Press.

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive therapy for challenging problems: What to do when the basics don’t work. Guilford.

- Beck, J. S., & Tompkins, M. A. (2007). Cognitive therapy. In N. Kazantzis, & L. L'Abate (Eds.), Handbook of homework assignments in psychotherapy: Research, practice, prevention (pp. 51–63). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-29681-4_4

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

- Calamaras, M. R., Tully, E. C., Tone, E. B., Price, M., & Anderson, P. L. (2015). Evaluating changes in judgmental biases as mechanisms of cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 71, 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.006

- Castro-Schilo, L., & Grimm, K. J. (2018). Using residualized change versus difference scores for longitudinal research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(1), 32–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517718387

- Conklin, L. R., Curreri, A. J., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2021). Homework compliance and quality in cognitive behavioral therapies for anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behavior Therapy, 52(4), 1008–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2021.01.001

- Dobson, K. S. (2021). A commentary on the science and practice of homework in cognitive behavioral therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 45(2), 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10217-5

- Draheim, A. A., & Anderson, P. L. (2019). Working alliance does not mediate the relation between outcome expectancy and symptom improvement following cognitive behavioural therapy for social anxiety disorder. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 12, e41. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X19000266

- Edelman, R. E., & Chambless, D. L. (1995). Adherence during sessions and homework in cognitive-behavioral group treatment of social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(5), 573–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00068-U

- Eriksson, K., & Haggstrom, O. (2014). Lord’s paradox in a continuous setting and a regression artifact in numerical cognition research. PLoS One, 9(4), e95949. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0095949

- First, M. B., Williams, J. B. W., Karg, R. S., & Spitzer, R. L. (2015). Structured clinical interview for DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association.

- Glymour, M. M., Weuve, J., Berkman, L. F., Kawachi, I., & Robins, J. M. (2005). When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. American Journal of Epidemiology, 162(3), 267–278. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi187

- Haller, E., & Watzke, B. (2021). The role of homework engagement, homework-related therapist behaviors, and their association with depressive symptoms in telephone-based CBT for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 45(2), 224–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10136-x

- Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

- Hatcher, R. L., & Gallaspy, J. A. (2006). Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychotherapy Research, 16(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300500352500

- Haug, T., Nordgreen, T., Öst, L. G., Tangen, T., Kvale, G., Hovland, O. J., Heiervang, E. R., & Havik, O. E. (2016). Working alliance and competence as predictors of outcome in cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety and panic disorder in adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.004

- Helbig, S., & Fehm, L. (2004). Problems with homework in CBT: Rare exception or rather frequent? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 32(3), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465804001365

- Hoffart, A., Borge, F.-M., Sexton, H., Clark, D. M., & Wampold, B. E. (2012). Psychotherapy for social phobia: How do alliance and cognitive process interact to produce outcome? Psychotherapy Research, 22(1), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2011.626806

- Holdsworth, E., Bowen, E., Brown, S., & Howat, D. (2014). Client engagement in psychotherapeutic treatment and associations with client characteristics, therapist characteristics, and treatment factors. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(5), 428–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.004

- Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hudson, J. L., & Kendall, P. C. (2005), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 75–94). Routledge.

- Huibers, M. J. H., Lorenzo-Luaces, L., Cuijpers, P., & Kazantzis, N. (2021). On the road to personalized psychotherapy: A research agenda based on cognitive behavior therapy for depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 607508. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.607508

- Jazaieri, H., Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2018). The role of working alliance in CBT and MBSR for Social Anxiety Disorder. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1381–1389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0877-9

- Johnson, A., Bank, S., Summers, M., Hyett, M., Erceg-Hurn, D., Kyron, M., & McEvoy, P. M. (2020). A longitudinal assessment of the bivalent fear of evaluation model with social interaction anxiety in social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 37(12), 1253–1260. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23099

- Kazantzis, N. (2021). Introduction to the special issue on homework in cognitive behavioral therapy: New clinical psychological science. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 45(2), 205–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10213-9

- Kazantzis, N., Brownfield, N., Mosely, L., Usatoff, A., & Flighty, A. (2017). Homework in CBT: A systematic review of adherence assessment in anxiety and depression treatment (2011-2016). Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 40(4), 625–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.001

- Kazantzis, N., Dattilio, F. M., & Dobson, K. S. (2017). The therapeutic relationship in cognitive behavior therapy: A clinician’s guide. Guilford.

- Kazantzis, N., Deane, F., & Ronan, K. (2005). Homework rating scale II – Client version. In N. Kazantzis, F. P. Deane, K. R. Ronan, & L. L’Abate (Eds.), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy. Routledge.

- Kazantzis, N., & Dobson, K. S. (2022). Therapeutic relationships in cognitive behavioral therapy: Theory and recent research. Psychotherapy Research, 32(8), 969–971. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2022.2124047

- Kazantzis, N. (in press). Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Kazantzis, N., & L'Abate, L. (2005). Theoretical foundations. In N. Kazantzis, F. Deane, K. Ronan, & L. L'Abate (Eds.), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 9–34). Routledge.

- Kazantzis, N., MacEwan, J., & Dattilio, F. M. (2005). A guiding model for practice. In N. Kazantzis, F. P. Deane, K. R. Ronan, & L. L’Abate (Eds.), Using homework assignments in cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 359–407). Routledge.

- Kazantzis, N., & Miller, A. R. (2022). A comprehensive model of homework in cognitive behavior therapy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46, 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10247-z

- Kazantzis, N., Whittington, C., & Dattilio, F. (2010). Meta-analysis of homework effects in cognitive and behavioral therapy: A replication and extension. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2010.01204.x

- Kazantzis, N., Whittington, C. J., Zelencich, L., Norton, P. J., Kyrios, M., & Hofmann, S. G. (2016). Quantity and quality of homework compliance: A meta-analysis of relations with outcome in cognitive behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 47(5), 755–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.05.002

- Kenny, D. A. (1975). Cross-lagged panel correlation: A test for spuriousness. Psychological Bulletin, 82(6), 887–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.82.6.887

- LeBeau, R. T., Davies, C. D., Culver, N. C., & Craske, M. G. (2013). Homework compliance counts in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 42(3), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2013.763286

- Leung, A. W., & Heimberg, R. G. (1996). Homework compliance, perceptions of control and outcome of cognitive-behavioral treatment of social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(5-6), 423–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(96)00014-9

- Mattick, R. P., & Clarke, J. C. (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(4), 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10031-6

- McDonald, B., & Morgan, R. (2013). Enhancing homework compliance in correctional psychotherapy. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(7), 814–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854813480781

- McEvoy, P. M., Bendlin, M., Johnson, A. R., Kazantzis, N., Campbell, B. N. C., Bank, S., & Egan, S. J. (2023). The relationships among working alliance, group cohesion and homework engagement in group cognitive behaviour therapy for social anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy Research, https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2022.2161966

- McEvoy, P. M., Erceg-Hurn, D. M., Saulsman, L. M., & Thibodeau, M. A. (2015). Imagery enhancements increase the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural group therapy for social anxiety disorder: A benchmarking study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 65, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.12.011

- McEvoy, P. M., Hyett, M. P., Bank, S. R., Erceg-Hurn, D. M., Johnson, A. R., Kyron, M. J., Saulsman, L. M., Moulds, M. L., Grisham, J. R., Holmes, E. A., Moscovitch, D. A., Lipp, O. V., Campbell, B. N. C., & Rapee, R. M. (2022). Imagery-enhanced versus verbally based group cognitive-behaviour therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomised clinical trial. Psychological Medicine, 52(7), 1277–1286. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720003001

- McEvoy, P. M., Moulds, M. L., Grisham, J. R., Holmes, E. A., Moscovitch, D. A., Hendrie, D., Saulsman, L. M., Lipp, O. V., Kane, R. T., Rapee, R. M., Hyett, M. P., & Erceg-Hurn, D. M. (2017). Assessing the efficacy of imagery-enhanced cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 60, 34–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2017.06.010

- McEvoy, P. M., Nathan, P., Rapee, R. M., & Campbell, B. N. C. (2012). Cognitive behavioural group therapy for social phobia: Evidence of transportability to community clinics. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(4), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.01.009

- Mörtberg, E. (2014). Working alliance in individual and group cognitive therapy for social anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Research, 220(1-2), 716–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.004

- Mululo, S. C. C., Menezes, G. B. D., Vigne, P., & Fontenelle, L. F. (2012). A review on predictors of treatment outcome in social anxiety disorder. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 34(1), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462012000100016

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthen, B. (2017). Mplus user's guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables, user's guide. Muthén & Muthén.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2013). Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment and treatment. Downloaded from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg159 on 1/1/2022.

- Neimeyer, R. A., Kazantzis, N., Kassler, D. M., Baker, K. D., & Fletcher, R. (2008). Group cognitive behavioural therapy for depression outcomes predicted by willingness to engage in homework, compliance with homework, and cognitive restructuring skill acquisition. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 37(4), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070801981240

- Norton, P. J., & Kazantzis, N. (2016). Dynamic relationships of therapist alliance and group cohesion in transdiagnostic group CBT for anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(2), 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000062

- Rodebaugh, T. L., Woods, C. M., Thissen, D. M., Heimberg, R. G., Chambless, D. L., & Rapee, R. M. (2004). More information from fewer questions: The factor structure and item properties of the original and brief fear of negative evaluation scale. Psychological Assessment, 16(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.16.2.169

- Ryum, T., Bennion, M., & Kazantzis, N. (2023). Integrating between-session homework in psychotherapy: A systematic review of immediate in-session and intermediate outcomes. Psychotherapy, 60(3), 306–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000488

- Sachsenweger, M., Fletcher, R., & Clarke, D. (2015). Pessimism and homework in CBT for depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(12), 1153–1172. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22227

- Schuurman, N. K., Ferrer, E., de Boer-Sonnenschein, M., & Hamaker, E. L. (2016). How to compare cross-lagged associations in a multilevel autoregressive model. Psychological Methods, 21(2), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000062

- Sorjonen, K., & Melin, B. (2023). Spurious prospective effect of perfectionism on depression: Reanalysis of a meta-analytic cross-lagged panel analysis. Preprint at psyarxiv.com.

- Sorjonen, K., Melin, B., & Ingre, M. (2019). Predicting the effect of a predictor when controlling for baseline. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 79(4), 688–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164418822112

- Steiger, J. H. (2007). Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 893–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.017

- Stein, D. J., Lim, C. C. W., Roest, A. M., DeJonge, P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Bruffaerts, R., de Giralamo, G., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Harris, M. G., He, Y., Hinkov, H., Horiguchi, I., Hu, C., … Scott, K. M. (2017). The cross-national epidemiology of social anxiety disorder: Data from the world mental health survey initiative. BMC Medicine, 15(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0889-2

- Stokes, J. P. (1983). Components of group cohesion: Intermember attraction, instrumental value, and risk taking. Small Group Behavior, 14(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649648301400203

- Struhldreher, N., Leibing, E., Leichsenring, F., Beutel, M. E., Herpetz, S., Hoyer, J., Konnopka, A., Salzer, S., Strauss, B., Wiltink, J., & Konig, H. H. (2014). The costs of social anxiety disorder: The role of symptom severity and comorbidities. Journal of Affective Disorders, 165, 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.039

- Strunk, D. R., Lorenzo-Luaces, L., Huibers, M. J. H., & Kazantzis, N. (2021). Editorial: contemporary issues in defining the mechanisms of cognitive behavior therapy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 1541. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.755136

- Taube-Schiff, M., Suvak, M. K., Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., & McCabe, R. E. (2007). Group cohesion in cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(4), 687–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.06.004

- Woody, S. R., & Adessky, R. S. (2002). Therapeutic alliance, group cohesion, and homework compliance during cognitive-behavioral group treatment of social phobia. Behavior Therapy, 33(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(02)80003-X

- Yew, R. Y., Dobson, K. S., Zyphur, M., & Kazantzis, N. (2021). Mediators and moderators of homework-outcome relations in CBT for depression: A study of engagement, therapist skill, and client factors. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 45(2), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-019-10059-2

- Zelencich, L., Kazantzis, N., Wong, D., McKenzie, D., Downing, M., & Ponsford, J. (2020). Predictors of homework engagement in CBT adapted for traumatic brain injury: Pre/post-injury and therapy process factors. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 44(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-019-10036-9