Abstract

Objective

Deliberate practice (DP) is recommended as a new approach to facilitate the acquisition of discrete therapeutic skills, however, its implementation and effectiveness in psychotherapy remains unclear.

Method

A systematic search on DP for therapeutic skills among psychotherapy trainees and psychotherapists yielded eleven studies for inclusion. Nine were randomized controlled studies (RCTs), including seven unique RCTs, and two were within-group studies.

Results

Risk of bias was assessed as “high” for one RCT, “some concerns” for the remaining RCTs, and “serious” for within-group studies. All RCTs found the DP group performed better than the control group. All studies involved efforts to improve performance based on learning objectives and iterative practice but varied in the source of expert guidance and feedback. The included studies provide limited insight into best practice for delivering DP.

Conclusion

The results highlight the paucity of research in this field; however they offer insight into current applications of DP and provide preliminary empirical support DP for as a model for promoting the development of discrete therapeutic skills. Given the rapid dissemination of DP publications and manuals in psychotherapy, future research is strongly encouraged.

Clinical or Methodological Significance of this Article: The application of DP to psychotherapy stems from efforts to enhance psychotherapy outcomes, and educators in psychotherapy training are already adopting DP to teach a range of therapeutic skills across therapeutic modalities. This review offers preliminary support for DP, while demonstrating that there is currently limited empirical evidence to support the rapid dissemination of DP materials and more research is strongly needed.

Therapist-related factors are pivotal in determining the effectiveness of psychotherapy. Meta-analytic evidence from naturalistic and efficacy studies underscores the significance of therapist-related effects in shaping client outcomes (Baldwin & Imel, Citation2013; Constantino et al., Citation2021; Wampold & Imel, Citation2015). A number of therapist factors have been found to contribute to client engagement and outcomes, including optimistic expectations (Constantino et al., Citation2020), positive regard and affirmation (Farber et al., Citation2019), and empathy (Elliott et al., Citation2019). Since these factors are theoretically modifiable, attention has been focused on how to adjust and enhance these therapist factors. Notably, findings from both cross-sectional (Chow et al., Citation2015; Delgadillo et al., Citation2020; Wampold & Brown, Citation2005) and longitudinal (Goldberg et al., Citation2016b; Hill et al., Citation2015; Owen et al., Citation2016) studies indicate that years of therapist experience alone does not appreciably impact client outcomes. This suggests that intentional and effortful modification of therapist factors is crucial for improving therapy outcomes.

Traditional approaches to therapy training typically prioritize the acquisition of theoretical knowledge and offer opportunities to apply the practical skills necessary for conducting psychotherapy interventions. These have been taught primarily through didactic (e.g., lectures, readings) and supervised clinical work, respectively (Kazantzis & Munro, Citation2011; Schwartz, Citation2004; Scott et al., Citation2011). Therapist qualities, including interpersonal abilities, subjective efficacy, and attitudes toward therapy, have been shown to be important for shaping client outcomes (Heinonen & Nissen-Lie, Citation2020; Wampold & Owen, Citation2021). Experiential approaches (e.g., roleplays, modelling, supervision, reflective practice) have been theorized and shown to be more effective in nurturing these key characteristics (Anderson et al., Citation2020; Baillie et al., Citation2011; Beidas & Kendall, Citation2010; Farber et al., Citation2019; Odyniec et al., Citation2019), while also addressing criticisms of traditional teaching methods, such as inadequate preparation for real-world practice and being insufficient for the development of complex therapist skills, including self-reflective capacity, self-awareness, and managing countertransference (Bennett-Levy et al., Citation2009; Scott et al., Citation2021; Taylor & Neimeyer, Citation2017).

These criticisms have led to the emergence of active teaching methods including simulation-based education (SBE), which is a form of experiential learning that allows learners to practice and develop their clinical skills in a safe and controlled environment that replicates real-life situations (Gaba, Citation2004). SBE incorporates simulation modalities, such as standardized or simulated clients, structured clinical examinations, or roleplays into the learning process, with a view towards improving the education and training of clinicians (Bearman et al., Citation2013; Ziv et al., Citation2005). Best practice SBE includes feedback before (e.g., discussion of intended learning outcomes) and after the simulation and promotes ongoing repetition to help learners master skills, thereby including components seen to be integral to learning process (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007) and responding to criticisms directed at didactic teaching methods. However, in practice, time and resourcing constraints often limit the potential for iterative practice and feedback (Australian Postgraduate Psychology Simulation Education Working Group [APPESWG], Citation2021), which may make it more difficult for learners to identify and address areas for improvement. Additionally, SBE commonly targets broad competency domains (e.g., ethics, risk management, structured interviews; APPESWG, Citation2021) rather than discrete clinical skills.

Deliberate practice (DP) is an active, focused, and intentional form of skills practice that incorporates elements from traditional teaching approaches and SBE. DP has been defined as consisting of four key elements: (i) a focused and systematic effort to improve performance, based on clear identification of learning objectives and pursued over an extended period, (ii) guidance from a “knowledgeable other” (e.g., coach, teacher, mentor), (iii) immediate, ongoing, and informative feedback relevant to the specific skills identified, and (iv) successive refinement and repetition (Miller et al., Citation2017). The core assumption of DP is that expert performance is acquired gradually, and that effective improvement requires the identification of suitable training tasks (i.e., outside of the individual’s current realm of reliable performance) that can be sequentially mastered through effortful action (Ericsson, Citation2006). DP is well-established as skill development methodology across a range of domains, including sports, music, and medicine (Macnamara et al., Citation2014; McGaghie et al., Citation2011), however comparatively little is known about its role in the development of therapeutic skills.

Emerging evidence has promoted researchers to consider DP as a potential framework to complement existing approaches for promoting the skill development and acquisition of therapists (McLeod, Citation2022; Rousmaniere et al., Citation2017) and to address the limitations and challenges of current pedagogies. For instance, a cross-sectional study identified that conducting more DP was associated with better client outcomes for therapists, which included psychotherapists, psychologists, social workers, marriage and family therapists, and counsellors (Chow et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, Goldberg and colleagues' (Citation2016a) analysed seven years of data from 153 therapists and 5128 clients at a mental health agency focused on improving the outcomes of therapists and found that therapists’ outcomes improved over time using DP. However, both studies relied on therapists’ retrospective accounts of how much they engaged in DP and data that examines the prospective impact of DP on therapeutic outcomes is lacking. A single scoping review has been conducted and found that DP, while still in its infancy, compares favourably to traditional didactic training for skill acquisition across various therapeutic skills and practices (Mahon, Citation2023). Using a scoping methodology, this review did not conduct risk of bias assessments or ask specific research questions and imposed broad inclusion criteria. Training methods like motivational interviewing training have incorporated elements similar to DP, such as targeted and repeated practice, individual coaching, feedback on performance, and measurement over time (Madson et al., Citation2019; Söderlund et al., Citation2011). As such, this review specifically focuses on the application of DP within psychotherapy to provide a concentrated analysis of its unique contributions and potential in this domain, and to explore whether the enthusiasm for its uptake is warranted. It will systematically review evidence regarding the application of DP as a training approach in psychotherapy. It will seek to inform and guide educators about how to deliver DP in an effective and feasible way, with respect to chosen skill(s), educator, trainee or therapist level, mode of delivery, duration, and intensity, as well as explore the most salient components of DP. The systematic review had several research questions: (1) How was DP used in the included studies and how effective was it? (2) What key elements of DP were adopted and adhered to in the included studies? (3) How do the included studies inform future understandings of delivering DP?

Defining Key Terms

The present review adopted the previously stated definition of DP from Miller et al. (Citation2017). The terms “psychotherapist” and “psychotherapy trainees” encompass individuals across various specific disciplines, including, but not limited to, psychology, counselling, and social work. The term “psychotherapy training” refers to the educational programmes that teach the knowledge and skills necessary for providing effective therapy to individuals with mental health concerns. This term will occasionally be abbreviated to “therapy” for brevity. The term “learner” and “coach” refer to the participants/therapists/trainees and the supervisor/mentor/teacher, respectively.

Method

Inclusion Criteria

Initially, studies were required to (i) fulfill DP requirements outlined by Miller and colleagues (Citation2017), (ii) explore the acquisition of discrete, specific therapeutic skill(s), (iii) provide information about the measure or index of performance, (iv) have an appropriate pre-intervention baseline measurement for single group designs, or comparison group featuring traditional, clinical education for controlled studies (McGaghie et al., Citation2011), (v) objectively assess skill acquisition, rather than self-reported knowledge and perceptions (McGaghie et al., Citation2011), (vi) use DP as a standalone methodology where isolating its effects is possible, and (vii) have psychotherapists and psychotherapy trainees as participants, in order to explore the application of DP for skill acquisition in these populations. The latter criterion was influenced by research exploring the training of microskills in early trainee education (Hill et al., Citation2016).

Given the limited research on DP in psychotherapy, very few studies met the initial inclusion criteria at the time of the initial search. Therefore, less stringent inclusion criteria were set to capture the literature more comprehensively. The modified inclusion criteria required that the studies (i) largely meet the DP requirements outlined by Miller and colleagues (Citation2017), (ii) explore the acquisition of discrete, specific therapeutic skill(s), (iii) provide information about the measure or index of performance, (iv) have an appropriate pre-intervention baseline measurement for single group designs, or comparison group featuring traditional, clinical education for controlled studies, (v) have a prospective quantitative or qualitative study design, in order to minimize recall bias, allow for controlled assessment of the effectiveness of DP, and develop an understanding of participants’ experience of DP, (vi) report on any/all relevant outcomes related to skill acquisition and the effectiveness of DP, and (vii) have psychotherapists and psychotherapy trainees as participants.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if they were: (i) reviews, (ii) books or book chapters, (iii) systematic reviews or meta-analyses, (iv) conference abstracts, (v) dissertations, (vi) editorials, (vii) interviews, (ix) reliability or validity studies, (x) case studies, (xi) curricula or programme plans or evaluations, (xii) written in a language other than English, and (xii) unavailable in full-text.

Search Strategy

A systematic and comprehensive search of peer-reviewed literature was conducted from inception until September 2023 in APA PsycINFO (via EBSCO), MEDLINE Complete (via EBSCO), CINAHL (via EBSCO) and Embase (via Embase). The search was not limited to a specific date range to allow all published studies on the topic to be included. The search was conducted using relevant key terms and controlled vocabulary terms relating to DP (e.g., deliberate practice, feedback-informed practice) and clinician-related terms (e.g., psychotherapist, psychologist, counsellor; see Supplementary Materials for replicable search strategy).

Selection of Studies

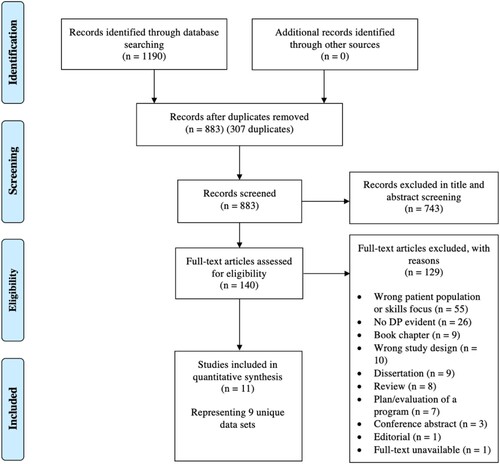

Covidence (Citation2023) was used to remove all duplicates. No further duplicates were detected during screening. Using Covidence, a single author (KN) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all identified studies, and then conducted a full-text review, to identify relevant studies for inclusion. Additionally, 10% of the studies were randomly selected for external review by a second author (NC) at the full-text screening stage. Inter-rater reliability calculation revealed complete agreement (kappa = 1, p < .001). This did not lead to any changes to the studies included within the review. Covidence was used to sort references according to the PRISMA workflow diagram (see ; Moher et al., Citation2009).

To identify any additional studies, a snowball search was conducted of the citations and references of key articles (e.g., Chow et al., Citation2015) and book chapters (e.g., Rousmaniere et al., Citation2017). Key psychological journals (e.g., Psychotherapy, Psychotherapy Research, and Counselling and Psychotherapy Research) and websites relevant to DP in psychotherapy (e.g., https://www.idpsociety.com/research and https://sentio.org/dpresearch) were also hand searched. No further studies were identified via this method.

Data Extraction

The search yielded 1190 results, consisting of 883 non-duplicates. Following title and abstract screening, the full text of 140 articles were assessed for eligibility and 11 studies met the inclusion criteria. Snowball searching identified no studies that met inclusion criteria, resulting in 11 studies being included within the review. Once all articles eligible for inclusion were identified, data was extracted regarding participant demographic information, study design, target skill, training duration, sample size, outcome data, and how DP was applied within each study.

Quality Assessment

The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2; Sterne et al., Citation2019) for the RCTs and the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—Interventions (ROBINS-I; Sterne et al., Citation2016) for the non-randomized within-group studies.

Analysis

A dual analysis approach was considered the best option to answer the research questions and based on the studies identified: descriptive synthesis and vote counting. Within the descriptive synthesis, the following domains were considered: participant characteristics, study design, target therapeutic skill(s), mode of delivery, duration and intensity, and application of DP. Collectively, these data were used to ascertain the best ways to undertake research on DP in psychotherapy and identify avenues for future research. Vote counting was used to determine the number of studies supporting the effectiveness of DP compared to the control group or baseline comparison.

Results

Included Studies

This review included nine RCTs with sample sizes ranging from 36 to 109 participants, and two within-group studies with sample sizes ranging from seven to 13 participants. The within-group studies used a mixed-methods design with qualitative and pre- and post-training data. Three studies were published in 2020 (27%), three in 2021 (27%), two in 2022 (18%), and three in 2023 (27%). Notably, all RCTs have been published since 2020 onwards. The RCTs are summarized in and within-group studies are summarized in .

Table 1. Randomized controlled studies (RCTs) to evaluate the use of deliberate practice in psychotherapy.

Table 2. Within-group studies to evaluate the use of deliberate practice in psychotherapy.

Therapy Training Characteristics. The RCTs targeted various specific therapeutic skills. Three studies targeted facilitative interpersonal skills (FIS; e.g., empathy, alliance bond capacity, and warmth/positive regard, among others; Anderson et al., Citation2020; Perlman et al., Citation2020, Citation2023). Three studies focused on managing ambivalence and resistance within motivational interviewing, specifically “rolling with resistance” (e.g., amplified reflection, reframing; Di Bartolomeo et al., Citation2021; Westra et al., Citation2021) and support (e.g., reflecting, normalizing) and demand (e.g., advising fixing, warning) behaviours (Shukla et al., Citation2021). One study targeted communication skills (e.g., paraphrasing, reflecting feelings; Newman et al., Citation2022b). One study focused on emotional processing skills (e.g., eliciting client disclosure of difficult experiences, eliciting adaptive emotions; Yamin et al., Citation2023). One study targeted expressed empathy, both verbal and non-verbal (Larsson et al., Citation2023). Within-group studies targeted communication skills (e.g., paraphrasing, reflecting feelings; Newman et al., Citation2022a) and the skill of immediacy (Hill et al., Citation2020), which refers to therapists disclosing or inquiring about immediate feelings related to the client, themselves, or the relationship.

DP was part of larger training approach in four studies (Newman et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Perlman et al., Citation2020, Citation2023) and was the sole training approach in the remaining seven studies.

The duration ranged from a single 60-minute session (Yamin et al., Citation2023) to a 45-hour course over 15 weeks (Newman et al., Citation2022a). One study provided no duration information (Shukla et al., Citation2021). One RCT conducted training individually (Yamin et al., Citation2023). The remaining RCTs used a group format, but some involved independent skills practice (e.g., practice recorded in private or online; Anderson et al., Citation2020; Newman et al., Citation2022b; Perlman et al., Citation2020, Citation2023). Of the within-group studies, one used an individual format (Newman et al., Citation2022a) and one used both group and individual (Hill et al., Citation2020).

Participant Characteristics. Most participants were female across all studies. Most studies focused on psychotherapy students, rather than experienced therapists. Nine studies recruited postgraduate psychotherapy or psychology students, six recruited undergraduate students, and four recruited professional and community therapists, and one study included undergraduate and master’s students from fields other than psychotherapy (e.g., medicine, nursing). Four studies recruited participants across multiple levels of experience and/or qualification. Of the studies reviewed, six (54%) did not provide information on the participants’ experience beyond describing who the participants were. Others reported years of experience (9%; Westra et al., Citation2021), self-estimated lifetime clinical hours (9%; Perlman et al., Citation2020), highest degree earned (9%; Shukla et al., Citation2021), or multiple measures of experience (18%; Di Bartolomeo et al., Citation2021; Newman et al., Citation2022b).

Outcomes of Deliberate Practice Application. The included studies’ application of specific DP components will be addressed in the discussion. All RCTs found that the DP group outperformed the control group for the primary study outcome measures. Two studies conducted longitudinal follow-ups. One study found that, despite a decline in skills for both groups, the DP group maintained their relative advantage over the control group at the 4-month follow-up (Westra et al., Citation2021). Another study found that all three skills were maintained at the 5-week follow-up, as was the relative advantage of the DP group over the control for eliciting disclosure (Yamin et al., Citation2023). Across these studies, the control group received information and skills training in a more traditional, passive learning format, such as workshops involving didactic presentations, video demonstrations, paper-and-pencil exercises, and group discussions. The within-group studies did not objectively assess participants’ performance of the skill of immediacy (Hill et al., Citation2020) or communication microskills (Newman et al., Citation2022a). However, Hill and colleagues (Citation2020) identified improved self-efficacy for immediacy and therapist-rated working alliance, but no significant effect for client-rated working alliance. Participants also reported the training was effective for managing emotions and countertransference. Newman and colleagues (Citation2022a) reported increased trainee communication self-efficacy and overall satisfaction with the training.

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias for the randomized studies was rated as “some concerns” for eight studies (i.e., the study raises some concerns in at least one domain for this result, but not to be at high risk of bias for any domain) and “high” for one study (i.e., the study is judged to be at high risk of bias in at least one domain; Sterne et al., Citation2019). The assignment to intervention (the “intention-to-treat” effect) results were extracted in the RoB 2 assessments. A common risk of bias was in “selection of the reported result,” which was primarily due to no available information about adherence to a pre-specified analysis plan.

Notably, confounding in RCTs is largely mitigated by the randomization process. Of the RCTs, seven studies had blinded primary outcome assessors and two did not provide information (Di Bartolomeo et al., Citation2021; Newman et al., Citation2022b). One study had blinded participant allocation (Anderson et al., Citation2020), seven did not provide information, and one stated that participants were aware of group assignment (Larsson et al., Citation2023).

The risk of bias for both non-randomized studies was rated as “serious” (i.e., has some important problems; Sterne et al., Citation2016), indicating that these results need to be interpreted with caution. The ROBINS-I recommends excluding studies deemed to be of critical risk (i.e., the study is too problematic to provide any useful evidence; Sterne et al., Citation2016), however, no studies met this level, and all studies were retained. The ROBINS-I tool considers risk of bias due to confounding, deviations from intended intervention, and selection of participants, among others, in the overall bias rating (see Sterne et al., Citation2016). For full risk of bias assessments, see Supplementary Materials.

Discussion

In light of the emerging interest in DP as a model for therapists’ skill development, this review aimed to systematically review evidence regarding the application of DP as a training approach in psychotherapy and inform future practice. Eleven studies were identified which included three studies examining the same dataset, with nine utilizing a RCT study design. Findings from identified RCTs suggest that DP outperforms more traditional training (e.g., didactic presentation of central concepts, watching clinical videos, group discussions). However, of these studies, three incorporated DP as part of a larger training. This, alongside the fact that all included studies were published since 2020, confirms the emerging state of the literature and shows there is limited available research from which to evaluate DP’s effectiveness as a standalone training approach for therapy skills. The two within-group studies found that DP led to improved self-efficacy for the skills of immediacy and communication, suggesting that DP may be a promising method for enhancing self-efficacy in important clinical skills. The present review builds on a single previous scoping review (Mahon, Citation2023), corroborating findings that research is scarce and DP outperforms traditional workshops for improving therapeutic skills. The current review goes a step further by evaluating the quality of existing research, adherence to key components of DP, and optimal implementation of DP. While Mahon (Citation2023) positioned DP as “one method that can support the development of expertise and superior outcomes” (p. 12), this review suggests that, while current evidence is promising, a more conservative stance may be appropriate.

Effectiveness and Application of Deliberate Practice

An aim of this review was to explore the effectiveness of DP for acquiring therapeutic skills and how it has been applied in the literature. The findings indicate that DP as a standalone modality can be effective in improving performance for FIS (Anderson et al., Citation2020), managing ambivalence and resistance (Di Bartolomeo et al., Citation2021; Shukla et al., Citation2021; Westra et al., Citation2021), emotional processing skills (Yamin et al., Citation2023), and expressed empathy (Larsson et al., Citation2023). As part of a broader training approach, DP can help enhance FIS (Perlman et al., Citation2020, Citation2023) and communication microskills (Newman et al., Citation2022b). Furthermore, two studies found that skills acquired through DP were maintained at five-week (Yamin et al., Citation2023) and four-month follow-up (Westra et al., Citation2021).

The reviewed studies also suggest that DP can benefit individuals at different stages of therapist development, from undergraduate students to professional therapists. However, it was not possible to determine whether DP is more helpful for a particular population. Most included studies did not customize DP to individual skill levels, despite recommendations to identify and practice within learners’ zone of proximal development for more targeted and effective skill acquisition (Chow, Citation2022), and it was not possible to determine how this impacted effectiveness. Eight RCTs delivered DP in a group format, while one conducted training individually (Yamin et al., Citation2023), and the two within-group studies used an individual format or a combination. As a result, there were not enough controlled studies to assess which format was more effective. However, the reviewed studies indicate that DP can be adapted to group settings and provide a blueprint for doing so. This contrasts with the typical application of DP in individual settings (Rousmaniere et al., Citation2017). Future research should explore the impact of these different conditions on the effectiveness of DP, compare DP to other teaching methods, and conduct longitudinal investigations.

Adherence to Key Components of Deliberate Practice

A further aim was to explore the studies’ adherence to the key elements of DP. The review found the nature of DP differed between studies. All studies aimed to improve performance of specific skills based on the clear learning objectives and the successive refinement of skills. Notably, only one study incorporated personalized learning objectives and tailored DP to help participants apply the skill of immediacy to their therapy with a challenging client and sought to ensure participants were practicing at an adequate difficulty level (Hill et al., Citation2020). There were differences between studies in the source of expert guidance and feedback provided.

Source of Expert Guidance. Within DP, the process of refinement and repetition occurs through the direct engagement and dialogue between coach and learner (Goodyear & Rousmaniere, Citation2017). The coach provides feedback that focuses on performance goals slightly beyond the learner’s current level of functioning and, once specific skill competencies have been met through practice, the coach increases the difficulty to further refine the learner’s performance. However, only five studies included in the review offered learners the opportunity to receive guidance from an expert coach in this way (Hill et al., Citation2020; Larsson et al., Citation2023; Perlman et al., Citation2020, Citation2023; Yamin et al., Citation2023). This is noteworthy given that the coach’s role in providing feedback and direct instruction is considered an important factor that sets DP apart from other active learning models (Rousmaniere et al., Citation2017). Three studies from the same trial involved the presenter debriefing responses for each vignette and offering ideal responses (Di Bartolomeo et al., Citation2021; Shukla et al., Citation2021; Westra et al., Citation2021). Three studies used an automated online source (Anderson et al., Citation2020; Newman et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b), which is consistent with using simulators and automated systems for providing feedback within DP in medicine (McGaghie et al., Citation2011). However, since therapeutic skills training involves more complex interpersonal processes (Hill et al., Citation2017) than professions with concrete procedures and outcomes, the coach-learner engagement is likely to be more critical and should be a primary focus for DP in therapy.

Provision of Feedback. The review included nine studies that provided immediate feedback and two that provided weekly feedback (Newman et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b).

This is consistent with Ericsson and colleagues' (Citation1993) emphasis in their seminal paper about the importance of “immediate informative feedback” (p. 367) for learners. Of the included studies, only six provided individualized feedback (Hill et al., Citation2020; Larsson et al., Citation2023; Newman et al., Citation2022b; Perlman et al., Citation2020, Citation2023; Yamin et al., Citation2023). Feedback in the remaining five studies took various forms that relied on participants having good evaluative judgement and the capacity to translate general feedback into specific, individualized actions. DP theory and research on effective feedback suggest that coaches focus on individualized performance objectives, break down feedback into manageable chunks to help learners exceed their current level of functioning, and provide timely, personalized, and non-punitive feedback (Goodyear & Rousmaniere, Citation2017; Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007; Miller et al., Citation2017; Shute, Citation2008). It can therefore be inferred that most included studies did not adopt the recommended practices for ensuring effective learning from feedback in DP. Several studies found that DP was more effective than controls even when using an automated feedback source (e.g., Anderson et al., Citation2020; Di Bartolomeo et al., Citation2021). This suggests that modified forms of DP can still be effective and may be an important finding in the context of concerns about the practicality of DP as a training modality (Clements-Hickman & Reese, Citation2020), including time, resource and budget constraints, and accessibility of expert coaches.

Self-Reflection. Only two studies included a formal self-reflection component as part of DP (Newman et al., Citation2022b; Perlman et al., Citation2020). Self-reflection is described as an important step in the process of successive refinement in DP (Miller et al., Citation2017), and self-assessment and self-reflection are crucial components of feedback that contribute to learners’ self-regulatory skills (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, Citation2006; Tai et al., Citation2018; Yan & Carless, Citation2022). Efforts to integrate learner self-reflection into the DP framework may be aiming to expand the model to align with best practice guidelines. However, self-reflection was not explicitly mentioned as part of Ericsson and colleagues' (Citation1993) original conception of DP, and this may contribute to a lack of consistency in the degree to which self-reflection is formally elicited by the researchers.

Practical Considerations for the Delivery of Deliberate Practice

A final aim was to examine how the included studies contribute to future understandings of delivering DP. While the conclusions that can be drawn are limited, they offer useful insights into how DP could be applied in future training. The review shows that DP can be effective when used alone or combined with other teaching methods. This provides some support for recommendations to incorporate DP with other learning practices (e.g., self-reflection; Thwaites et al., Citation2017). The findings suggest that DP can benefit learners at different stages of therapist development. However, it may be important to tailor learning to individual needs and skill levels, as recommended within the DP literature (Rousmaniere et al., Citation2017) and asserted by research highlighting the growing value and effectiveness of personalized learning approaches in primary, secondary, and higher education (Schmid et al., Citation2022; Trojer et al., Citation2022). Researchers may use available DP training resources (Sentio University, Citation2021) to obtain difficulty assessments and make adjustments to ensure learners practice at the appropriate level (Castle, Citation2022). This review also indicates that DP can be adapted to a group setting, but with some limitations. For instance, authors describe restrictions on the amount of time available for feedback and practice, and the degree to which learning can be individualized (Di Bartolomeo et al., Citation2021; Westra et al., Citation2021). Conversely, group learning can promote observational and collaborative learning, communication skills, self-confidence, motivation, and diverse perspectives (Bandura, Citation1986; Hassanien, Citation2007; Johnson & Johnson, Citation1991; Slavin, Citation1980).

The duration of DP ranged from 60 minutes to 45 hours, with 90 minute sessions being the most common. It was not possible to determine the optimal length for DP from the included studies due to variability in study design and target skill, among others. Participants’ feedback and authors’ recommendations indicated that longer or multiple sessions would be beneficial (Di Bartolomeo et al., Citation2021; Hill et al., Citation2020; Newman et al., Citation2022a; Shukla et al., Citation2021). However, the recommended maximum duration for a single DP session is 90 minutes (Behary et al., Citation2023) and the impact of more repeated sessions over time is unclear. Extended training may give learners more time to practice, self-reflect and process learned material, and build a relationship with the educator, which are associated with positive outcomes for therapy trainees and practitioners (Bearman et al., Citation2019; Schneider & Rees, Citation2012; Scott et al., Citation2021). Conversely, brief DP may be more practically viable, and current findings indicated it can also facilitate skill acquisition (Perlman et al., Citation2020, Citation2023). Educators should consider these factors and their specific goals and circumstances in determining how they deliver DP.

Limitations

The study is limited by the small number of existing studies on this topic. This represents the early stage of DP research within the field of therapy and limits the strength and robustness of the conclusions that can be drawn. For instance, there was high diversity between studies in the implementation of DP, small sample sizes, and only two studies examined skill maintenance. The study is limited by the fact that both data extraction and the risk of bias assessments were conducted by a single author. Additionally, published case studies on therapist development may offer insights into how learning develops, however, these were not included in the present review due to the focus on DP. The chosen risk of bias tools may have limitations when applied to psychology research (Munder & Barth, Citation2018). For example, the blinding of study participants to their assigned intervention within psychotherapy research is often not feasible due to the interactive nature of the interventions, and this could increase reviewers’ ratings for “bias due to deviations from intended interventions” on the RoB 2 (Sterne et al., Citation2019). As such, the risk of bias ratings should be interpreted carefully.

Future Directions

The principal goal of DP is to improve client outcomes through their engagement with therapy. To date, however, only a few studies have investigated the impact of DP on client outcomes. These particular studies were not included in this review as they did not meet inclusion criteria, relying on therapists’ retrospective recall of independently engaging in DP, without a systematic investigation of DP training. Overall, these landmark preliminary studies suggest that therapists who spent more time practicing therapeutic skills have better client outcomes (Chow et al., Citation2015; Goldberg et al., Citation2016a), however a recently published replication of Chow and colleagues' (Citation2015) study found no correlation between therapists’ time spent on learning activities and treatment outcomes (Janse et al., Citation2023). Further research is encouraged to explore the impact of DP on client outcomes. In the interim, future research in DP should prioritize skills that are empirically linked to client outcomes (e.g., empathy, positive regard and affirmation; Elliott et al., Citation2019; Farber et al., Citation2019), thereby contributing to the broader goal of enhancing therapist efficacy. This is important considering that DP is a method aimed at skill enhancement but does not specify a particular target skill.

There is an ongoing challenge of defining DP within the literature (Ericsson, Citation2016; Macnamara et al., Citation2016). Vaz and Rousmaniere (Citation2022) caution that the lack of a clear differentiated definition of DP will compromise its study and implementation in therapy, however, they also acknowledge that delineating strict boundaries around DP may restrict the emergence of innovative and helpful forms. It is therefore important for future research to explicitly describe their application of DP while also being open to empirically supported adaptations to the framework to improve therapeutic skills and client outcomes.

It is also crucial for future research to reconsider the use of self-report measures given their potential for bias (Tracey et al., Citation2014) and endeavour to employ robust evaluation methods, such as assessing performance in simulation or actual practice settings and direct measures of client outcomes. Furthermore, since both automated and individualized feedback were related to positive learning outcomes, future research may explore innovative feedback methods in DP, such as a stepped feedback model wherein generic feedback is offered first and followed by more individualized or intensive feedback.

Questions also remain as to the acceptability and experience of learners engaged in DP, for example, in comparison to other training approaches. There is a need for qualitative research that explores learners’ perspectives and experiences of DP, which may inform future conceptions of how to tailor DP to align with learners’ personal and professional needs and objectives. Despite the limited research and strong need for further investigation, educators are already adopting DP to teach a range of therapy skills. This can be observed in the recent emergence of numerous manuals using DP to teach skills in cognitive–behavioural therapy (Boswell & Constantino, Citation2022), child and adolescent therapy (Bate et al., Citation2022), schema therapy (Behary et al., Citation2023), and more. This indicates that educators recognize potential in DP as a pedagogy for enhancing therapeutic practice, despite the early phase of the research.

Conclusion

This review provides support for DP as a potential model for promoting the development of discrete therapeutic skills for trainees and qualified therapists. All studies involved efforts to improve performance based on learning objectives and iterative practice, but varied in the source of expert guidance and feedback and provide limited insight into best practice for delivering DP. Despite the early phase of the literature, models of DP proliferate with remarkable speed, reflecting considerable enthusiasm about the approach and the need for more intensive investigation. Future research focused on assessing whether DP would be an effective adjunct to current training models, and understanding the acceptability and feasibility of DP in teaching clinical skills through conducting qualitative research will be crucial to support its application.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here doi:10.1080/10503307.2024.2308159

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, T., Perlman, M. R., McCarrick, S. M., & McClintock, A. S. (2020). Modeling therapist responses with structured practice enhances facilitative interpersonal skills. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 659–675. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22911

- Australian Postgraduate Psychology Simulation Education Working Group (APPESWG). (2021). A new reality: The role of simulated learning activities in postgraduate psychology training programs. Frontiers in Education, 6, 653269. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.653269

- Baillie, A. J., Proudfoot, H., Knight, R., Peters, L., Sweller, J., Schwartz, S., & Pachana, N. A. (2011). Teaching methods to complement competencies in reducing the “junkyard” curriculum in clinical psychology. Australian Psychologist, 46(2), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00036.x

- Baldwin, S. A., & Imel, Z. E. (2013). Therapist effects: Findings and methods. In M. J. Lambert, & A. E. Bergin (Eds.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed, pp. 258–297). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

- Bate, J., Prout, T., Rousmaniere, T., & Vaz, A. (2022). Deliberate practice in child and adolescent psychotherapy. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000288-017

- Bearman, M., Eppich, W., & Nestel, D. (2019). How debriefing can inform feedback: Practices that make a difference. In M. Henderson, R. Ajjawi, D. Boud, & M. Bearman (Eds.), The impact of feedback in higher education: Improving assessment outcomes for learners (pp. 165–188). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25112-3_10

- Bearman, M., Nestel, D., & Andreatta, P. (2013). Simulation-based medical education. In K. Walsh (Ed.), Oxford textbook of medical education (pp. 186–197). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Behary, W. T., Farrell, J. M., Vaz, A., & Rousmaniere, T. (2023). Deliberate practice in schema therapy. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000326-001

- Beidas, R. S., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x

- Bennett-Levy, J., McManus, F., Westling, B. E., & Fennell, M. (2009). Acquiring and refining CBT skills and competencies: Which training methods are perceived to be most effective? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 37(5), 571–583. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465809990270

- Boswell, J. F., & Constantino, M. J. (2022). Deliberate practice in cognitive behavioral therapy. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000256-000

- Castle, N. (2022). Practical ways to do deliberate practice. In K. Frankcom, D. Chow, R. Alvarz Wicklein, N. Castle, & A. Frost (Eds.), Creating impact: The four pillars of private psychology practice (pp. 190–217). Global Stories. ePub version.

- Chow, D. (2022). Therapist focused: Supervision and deliberate practice. In K. Frankcom, D. Chow, R. Alvarz Wicklein, N. Castle, & A. Frost (Eds.), Creating impact: The four pillars of private psychology practice (pp. 93–134). Global Stories. ePub version.

- Chow, D. L., Miller, S. D., Seidel, J. A., Kane, R. T., Thornton, J. A., & Andrews, W. P. (2015). The role of deliberate practice in the development of highly effective psychotherapists. Psychotherapy, 52(3), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000015

- Clements-Hickman, A. L., & Reese, R. J. (2020). Improving therapists’ effectiveness: Can deliberate practice help? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51(6), 606–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000318

- Constantino, M. J., Aviram, A., Coyne, A. E., Newkirk, K., Greenberg, R. P., Westra, H. A., & Antony, M. M. (2020). Dyadic, longitudinal associations among outcome expectation and alliance, and their indirect effects on patient outcome.. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000364

- Constantino, M. J., Boswell, J. F., & Coyne, A. E. (2021). Patient, therapist, and relational factors. In M. Barkham, W. Lutz, & L. G. Castonguay (Eds.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (7th ed, pp. 225–263). John Wiley & Sons.

- Covidence. (2023). https://www.covidence.org/.

- Delgadillo, J., Branson, A., Kellett, S., Myles-Hooten, P., Hardy, G. E., & Shafran, R. (2020). Therapist personality traits as predictors of psychological treatment outcomes. Psychotherapy Research, 30(7), 857–870. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1731927

- Di Bartolomeo, A. A., Shukla, S., Westra, H. A., Shekarak Ghashghaei, N., & Olson, D. A. (2021). Rolling with resistance: A client language analysis of deliberate practice in continuing education for psychotherapists. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(2), 433–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12335

- Elliott, R., Bohart, A. C., Watson, J. C., & Murphy, D. (2019). Empathy. In J. C. Norcross and M. J. Lambert (Eds.), Psychotherapy relationships that work, Vol. 1: Evidence-based therapist contributions (3rd ed., pp. 245–288). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ericsson, K. A. (2006). The influence of experience and deliberate practice on the development of superior expert performance. In K. A. Ericsson, N. Charness, P. J. Feltovich, & R. R. Hoffman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance (pp. 683–703). Cambridge University Press.

- Ericsson, K. A. (2016). Summing up hours of any type of practice versus identifying optimal practice activities. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(3), 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616635600

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

- Farber, B. A., Suzuki, J. Y., & Lynch, D. A. (2019). Positive regard and affirmation. In J. C. Norcross and M. J. Lambert (Eds.), Psychotherapy relationships that work, Vol. 1: Evidence-based therapist contributions (3rd ed., pp. 288–323). Oxford University Press.

- Gaba, D. M. (2004). The future vision of simulation in health care. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13(Suppl. 1), i2–i10. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.009878

- Goldberg, S. B., Babins-Wagner, R., Rousmaniere, T. G., Berzins, S., Hoyt, W. T., Whipple, J. L., Miller, S. D., & Wampold, B. E. (2016a). Creating a climate for therapist improvement: A case study of an agency focused on outcomes and deliberate practice. Psychotherapy, 53(3), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000060

- Goldberg, S. B., Rousmaniere, T., Miller, S. D., Whipple, J., Nielsen, S. L., Hoyt, W. T., & Wampold, B. E. (2016b). Do psychotherapists improve with time and experience? A longitudinal analysis of outcomes in a clinical setting. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000131

- Goodyear, R. K., & Rousmaniere, T. (2017). Helping therapists to each day become a littlebetter than they were the day before: The expertise-development model of supervision and consultation. In T. Rousmaniere, R. K. Goodyear, S. D. Miller, & B. E. Wampold (Eds.), The cycle of excellence: Using deliberate practice to improve supervision and training (pp. 67–97). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Hassanien, A. (2007). A qualitative student evaluation of group learning in higher education. Higher Education in Europe, 32(2-3), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/03797720701840633

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

- Heinonen, E., & Nissen-Lie, H. A. (2020). The professional and personal characteristics of effective psychotherapists: A systematic review. Psychotherapy Research, 30(4), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1620366

- Hill, C. E., Anderson, T., Kline, K., McClintock, A., Cranston, S., McCarrick, S., Petrarca, A., Himawan, L., Pérez-Rojas, A. E., Bhatia, A., Gupta, G., & Gregor, M. (2016). Helping skills training for undergraduate students The Counseling Psychologist, 44(1), 50–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000015613142

- Hill, C. E., Baumann, E., Shafran, N., Gupta, S., Morrison, A., Rojas, A. E. P., Spangler, P. T., Griffin, S., Pappa, L., & Gelso, C. J. (2015). Is training effective? A study of counseling psychology doctoral trainees in a psychodynamic/interpersonal training clinic. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 184–201. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000053

- Hill, C. E., Kivlighan III, D. M., Rousmaniere, T., Kivlighan Jr, D. M., Gerstenblith, J. A., & Hillman, J. W. (2020). Deliberate practice for the skill of immediacy: A multiple case study of doctoral student therapists and clients. Psychotherapy, 57(4), 587–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000247

- Hill, C. E., Spiegel, S. B., Hoffman, M. A., Kivlighan Jr. D. M., & Gelso, C. J. (2017). Therapist expertise in psychotherapy revisited. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(1), 7–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016641192

- Janse, P. D., Bakker-Brehm, D. T., Geurtzen, N., Scholing, A., & Hutschemaekers, G. J. (2023). Therapists’ self-assessment of time spent on learning activities and its relationship to treatment outcomes: A replication study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(4), 1070–1081. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23459

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, F. P. (1991). Joining together: Group theory and group skills. Prentice Hall.

- Kazantzis, N., & Munro, M. (2011). The emphasis on cognitive-behavioural therapy within clinical psychology training at Australian and New Zealand universities: A survey of program directors. Australian Psychologist, 46(1), 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2010.00011.x

- Larsson, J., Werthén, D., Carlsson, J., Salim, O., Davidsson, E., Vaz, A., Sousa, D., & Norberg, J. (2023). Does deliberate practice surpass didactic training in learning empathy skills? – A randomized controlled study. Nordic Psychology, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2023.2247572

- Macnamara, B. N., Hambrick, D. Z., & Moreau, D. (2016). How important is deliberate practice? Reply to Ericsson (2016). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(3), 355–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616635614

- Macnamara, B. N., Hambrick, D. Z., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). Deliberate practice and performance in music, games, sports, education, and professions: A meta-analysis. Psychological Science, 25(8), 1608–1618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614535810

- Madson, M. B., Villarosa-Hurlocker, M. C., Schumacher, J. A., Williams, D. C., & Gauthier, J. M. (2019). Do self-administered positive psychology exercises work in persons in recovery from problematic substance use? An online randomized survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 99, 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.01.006

- Mahon, D. (2023). A scoping review of deliberate practice in the acquisition of therapeutic skills and practices. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 23(4), 965–981. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12601

- McGaghie, W. C., Issenberg, S. B., Cohen, M. E. R., Barsuk, J. H., & Wayne, D. B. (2011). Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Academic Medicine, 86(6), 706–711. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318217e119

- Mcleod, J. (2022). How students use deliberate practice during the first stage of counsellor training. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(1), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12397

- Miller, S. D., Hubble, M. A., & Chow, D. (2017). Professional development: From oxymoron to reality. In T. Rousmaniere, R. K. Goodyear, S. D. Miller, & B. E. Wampold (Eds.), The cycle of excellence: Using deliberate practice to improve supervision and training (pp. 23–48). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Munder, T., & Barth, J. (2018). Cochrane’s risk of bias tool in the context of psychotherapy outcome research. Psychotherapy Research, 28(3), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1411628

- Newman, D. S., Gerrard, M. K., Villarreal, J. N., & Kaiser, L. T. (2022a). Deliberate practice of consultation microskills: An exploratory study of training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 16(3), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000368

- Newman, D. S., Villarreal, J. N., Gerrard, M. K., McIntire, H., Barrett, C. A., & Kaiser, L. T. (2022b). Deliberate practice of consultation communication skills: A randomized controlled trial. School Psychology, 37(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000494

- Nicol, D., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090

- Odyniec, P., Probst, T., Margraf, J., & Willutzki, U. (2019). Psychotherapist trainees’ professional self-doubt and negative personal reaction: Changes during cognitive behavioral therapy and association with patient progress. Psychotherapy Research, 29(1), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1315464

- Owen, J., Wampold, B. E., Rousmaniere, T. G., Kopta, M., & Miller, S. (2016). As good as it gets? Therapy outcomes of trainees over time. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000112

- Perlman, M. R., Anderson, T., Finkelstein, J. D., Foley, V. K., Mimnaugh, S., Gooch, C. V., David, K. C., Martin, S. J., & Safran, J. D. (2023). Facilitative interpersonal relationship training enhances novices’ therapeutic skills. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 36(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2022.2049703

- Perlman, M. R., Anderson, T., Foley, V. K., Mimnaugh, S., & Safran, J. D. (2020). The impact of alliance-focused and facilitative interpersonal relationship training on therapist skills: An RCT of brief training. Psychotherapy Research, 30(7), 871–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1722862

- Rousmaniere, T., Goodyear, R. K., Miller, S. D., & Wampold, B. E. (2017). Introduction. In T. Rousmaniere, R. K. Goodyear, S. D. Miller, & B. E. Wampold (Eds.), The cycle of excellence: Using deliberate practice to improve supervision and training (pp. 3–22). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Schmid, R., Pauli, C., Stebler, R., Reusser, K., & Petko, D. (2022). Implementation of technology-supported personalized learning—its impact on instructional quality. The Journal of Educational Research, 115(3), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2022.2089086

- Schneider, K., & Rees, C. (2012). Evaluation of a combined cognitive behavioural therapy and interpersonal process group in the psychotherapy training of clinical psychologists. Australian Psychologist, 47(3), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2012.00065.x

- Schwartz, S. (2004). Time to bid goodbye to the psychology lecture. The Psychologist, 17(1), 26–27. http://ezproxy.deakin.edu.au/login?url = https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/time-bid-goodbye-psychology-lecture/docview/211822335/se-2.

- Scott, J., Yap, K., Bunch, K., Haarhoff, B., Perry, H., & Bennett-Levy, J. (2021). Should personal practice be part of cognitive behaviour therapy training? Results from two self-practice/self-reflection cohort control pilot studies. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(1), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2497

- Scott, T. L., Pachana, N. A., & Sofronoff, K. (2011). Survey of current curriculum practices within Australian postgraduate clinical training programmes: Students' and programme directors' perspectives. Australian Psychologist, 46(2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00030.x

- Sentio University. (2021). Instructions for DP exercises. https://sentio.org/instructions-for-dp-exercises.

- Shukla, S., Di Bartolomeo, A. A., Westra, H. A., Olson, D. A., & Shekarak Ghashghaei, N. (2021). The impact of a deliberate practice workshop on therapist demand and support behavior with community volunteers and simulators. Psychotherapy, 58(2), 186–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000333

- Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 153–189. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654307313795

- Slavin, R. E. (1980). Cooperative learning. Review of Educational Research, 50(2), 315–342. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543050002315

- Söderlund, L., Madson, M. B., Rubak, S., & Nilsen, P. (2011). A systematic review of motivational interviewing training for general health care practitioners. Patient Education and Counseling, 84(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.025

- Sterne, J. A., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., Henry, D., Altman, D. G., Ansari, M. T., Boutron, I., Carpenter, J. R., Chan, A.-W., Churchill, R., Deeks, J. J., Hróbjartsson, A., Kirkham, J., Jüni, P., Loke, Y. K., Pigott, T. D., … Higgins, J. P. (2016). ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ, 355, i4919. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

- Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H.-Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Hernán, M. A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D. R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J. J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., McAleenan, A., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 366, l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

- Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Panadero, E. (2018). Developing evaluative judgement: Enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. Higher Education, 76(3), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3

- Taylor, J. M., & Neimeyer, G. J. (2017). The ongoing evolution of continuing education: Past, present, and future. In T. Rousmaniere, R. Goodyear, S. Miller, & B. Wampold (Eds.), The cycle of excellence: Training, supervision, and deliberate practice (pp. 219–248). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Thwaites, R., Bennett-Levy, J., Cairns, L., Lowrie, R., Robinson, A., Haarhoff, B., Lockhart, L., & Perry, H. (2017). Self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR) as a training strategy to enhance therapeutic empathy in low intensity CBT practitioners. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 46(2), 63–70.

- Tracey, T. J. G., Wampold, B. E., Lichtenberg, J. W., & Goodyear, R. K. (2014). Expertise in psychotherapy: An elusive goal? American Psychologist, 69(3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035099

- Trojer, L., Ambele, R. M., Kaijage, S. F., & Dida, M. A. (2022). A review of the development trend of personalized learning technologies and its applications. International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research and Engineering, 08(11), 75–91. https://ijasre.net/index.php/ijasre/article/view/1617/1999.

- Vaz, A., & Rousmaniere, T. (2022). Reaching for expertise: A primer on deliberate practice for psychotherapists. Sentio University.

- Wampold, B. E., & Brown, G. S. (2005). Estimating variability in outcomes attributable to therapists: A naturalistic study of outcomes in managed care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.914

- Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). Therapist effects: An ignored but critical factor. In B. E. Wampold, & Z. E. Imel (Eds.), The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed, pp. 158–178). Routledge.

- Wampold, B. E., & Owen, J. (2021). Therapist effects: History, methods, magnitude, and characteristics of effective therapists. In M. Barkham, W. Lutz, & L. G. Castonguay (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (7th ed., pp. 297–327). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Westra, H. A., Norouzian, N., Poulin, L., Coyne, A., Constantino, M. J., Hara, K., Olson, D., & Antony, M. M. (2021). Testing a deliberate practice workshop for developing appropriate responsivity to resistance markers. Psychotherapy, 58(2), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000311

- Yamin, J. B., Cannoy, C. N., Gibbins, K. M., Krohner, S., Rapport, L. J., Trentacosta, C. J., Zeman, L. L., & Lumley, M. A. (2023). Experiential training of mental health graduate students in emotional processing skills: a randomized, controlled trial. Psychotherapy, 60(4), 512–524. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000495

- Yan, Z., & Carless, D. (2022). Self-assessment is about more than self: The enabling role of feedback literacy. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 47(7), 1116–1128. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.2001431

- Ziv, A., Ben-David, S., & Ziv, M. (2005). Simulation based medical education: An opportunity to learn from errors. Medical Teacher, 27(3), 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500126718