?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objective

Parents’ rejection of their LGBTQ + young adults can have a negative impact on their young adult’s psychological welfare, and on the young adult-parent relationship. Parents’ ability to reflect on their child’s pain and unmet needs is thought to evoke empathy and compassion, and reduce rejection. Empirical and clinical evidence suggest that parents’ level of reflective functioning (RF) is impacted by their level of emotional arousal (EA). This study examined the association between parents’ EA and RF within the context of attachment-based family therapy for nonaccepting parents and their LGBTQ+ young adults.

Methods

43 therapy sessions drawn from six different cases were coded for parental RF and EA, based on 30-second segments. This generated a total of 343 observations for analyses.

Results

Hierarchal linear modeling revealed that parents’ level of RF was a function of their concomitant EA, with moderate levels of arousal predicting the highest RF levels.

Conclusion

Moderate EA may facilitate optimal parental reflective functioning. With nonaccepting parents, who typically present for treatment with high levels of maladaptive fear and shame, therapists would do well to assess their level of arousal and, when indicated, employ downregulating interventions before inviting them to reflect on their young adult’s experience and needs.

Clinical or Methodological Significance of this Article: Promoting parental reflective functioning can be critical to evoking empathy and compassion when working with parents who reject their young adult’s sexual orientation or gender identity. Our findings suggest that parents are best able to reflect on their young adult’s experience of rejection when they are moderately aroused. In contrast, when parents’ experience high levels of threat related arousal, they are more defensive and less likely to be able to imagine their child’s pain and unmet needs. Likewise, when parents are not emotionally engaged, they may be less motivated to exert the effort required to reflect on their young adult’s experience. Our findings suggest that, before inviting parents to reflect on their child’s experience, therapists should assess parents’ level of arousal and employ either emotional engagement or downregulating interventions, as indicated.

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and other sexual and gender minority (LGBTQ+) young adults experience higher rates of depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation than their heterosexual peers (Haas et al., Citation2010). Research findings suggest that these mental health disparities are rooted in sexual and gender minority people’s exposure to minority stress, including stigmatizing social structures (e.g., discriminatory laws, policies, community attitudes), interpersonal rejection, discrimination and victimization (Coulter et al., Citation2015; Eldahan et al., Citation2016; Hatzenbuehler & Pachankis, Citation2016; Lehavot & Simoni, Citation2011; Meyer, Citation2003; Pachankis et al., Citation2018; Raifman et al., Citation2018). According to the psychological mediational framework, stigma-related stressors, such as discrimination and victimization, can lead to both general and LGBTQ+ unique maladaptive stress responses, such as internalized stigma (i.e., adopting negative societal views of LGBTQ+ people into one’s own self-concept), identity concealment (i.e., hiding one’s sexual or gender identity from others) and the expectation of being rejected by others. Such maladaptive stress responses can, in turn, then lead to various forms of distress and psychopathology (Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2009). While identity concealment and the expectation of being rejected may be prudent under certain circumstances, when such responses are pervasive and fixed they can lead to social isolation and hypervigilance which can then lead to a state of chronic over-arousal, fear, anxiety and psychiatric morbidity (Hoy-Ellis, Citation2023; Nurius & Hoy-Ellis, Citation2013). In regards to internalized stigma (i.e., negative self-concept), there is ample research showing the link between self-criticism and various forms of psychopathology, including depression and suicidality (Werner et al., Citation2019).

One particularly pernicious minority stressor is parental rejection of one’s sexual orientation or gender identity. As Stone Fish and Harvey (Citation2005) have pointed out, it is impossible to grow up in a culture in which heterosexist, homophobic, and transphobic messages are prevalent and not be affected by such messages. It is no wonder that most parents experience some degree of fear, shame and loss upon learning that their own child is same-sex oriented or gender diverse. Some parents perceive being LGBTQ+ as a flaw or a sin, worry about how others, including their friends and extended family members, will react, and grieve the loss of their hetero- and gender-normative dream of sitting around the dinner table with their child, his or her opposite-sex spouse, and biological grandchildren. Parents may also fear for their child’s welfare, afraid that they will be discriminated against, victimized and generally have a hard time in life. Such fear, shame and sense of loss are what seem to drive parents to reject their LGBTQ+ children’s identity. Although most parents become more accepting over time, others remain partially or fully rejecting, even years after learning that their child is LGBTQ+ (Beals & Peplau, Citation2006; Cramer & Roach, Citation1988; Grossman et al., Citation2021; Samarova et al., Citation2014).

Ongoing parental rejection, expressed as invalidation, criticism, shaming, emotional withdrawal, guilt induction, psychological coercion and, in extreme cases, verbal and physical abuse or banishment from the family, is associated with heightened risk for anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Bouris et al., Citation2010; D’augelli, Citation2002; Kiekens et al., Citation2020; Pachankis et al., Citation2018; Parra et al., Citation2018; Ryan et al., Citation2009) Not only does parental rejection have a direct, negative effect on the welfare of young adults, but it can also undermine the quality of the young adult-parent attachment relationship (Allen & Hauser, Citation1996). This is important because high levels of parental acceptance and support have been found to buffer against the negative effects of minority stress (D’augelli, Citation2002; Eisenberg & Resnick, Citation2006; Elizur & Ziv, Citation2001; Hershberger & D’Augelli, Citation1995; Needham & Austin, Citation2010; Ryan et al., Citation2010; Savin-Williams, Citation1989; Sheets & Mohr, Citation2009; Shilo et al., Citation2015).

One treatment specifically designed to reduce parental rejection, increase parental acceptance and strengthen the young adult-parent bond is attachment-based family therapy for sexual and gender minority young adults and their nonaccepting parents (ABFT-SGM; Diamond & Boruchovitz-Zamir, Citation2023). ABFT is one of very few empirically-informed treatments designed to target a unique LGBTQ+ minority stress– ongoing parental rejection of their sexual or gender minority identity. There has been a call for developing such targeted treatments (Bochicchio et al., Citation2022; Pachankis, Citation2014). ABFT-SGM is a family-based, experiential, emotion-focused, LGBTQ+ affirmative and empirically informed treatment model. One of the primary change processes in ABFT-SGM is helping parents reflect on their young adult’s experience of being rejected by them. This process, which occurs in the context of individual sessions with parents, involves helping parents reflect on the negative impact their rejection has had on their young adult and on their relationship with their young adult. The assumption is that, as parents increasingly recognize the pain, fear, shame, loneliness and frustration their rejection has caused their child to feel, they become saddened, more compassionate and regretful. This, in turn, activates parents’ natural instincts to better understand, accept, support and protect their child.

The process of parents’ reflecting upon their young adult’s experience of rejection is a form of mentalizing or reflective functioning. Mentalizing, or reflective functioning, has been defined as the capacity to understand human behavior in terms of underlying mental states, including emotions, thoughts, and intentions (Luyten et al., Citation2020; Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015). The ability to effectively and accurately reflect on others’ mental states is essential for interpreting and comprehending complex and ever-changing social interactions that demand mutual understanding and collaboration (Freeman, Citation2016; Luyten et al., Citation2019). When people are able to openly consider and understand others’ needs, feelings and wishes in interpersonal contexts, they are better able to respond effectively. Not surprisingly, quality of reflective functioning is associated with the quality of romantic relationships (DiMaggio, Citation2020; Jessee et al., Citation2018; Salo et al., Citation2021), relationships with friends and peers (Białecka-Pikul et al., Citation2021; Bosacki & Wilde Astington, Citation1999) and parent–child relationships (Camoirano, Citation2017; Menashe-Grinberg et al., Citation2021; Ordway et al., Citation2015).

One factor that may impact parents’ ability to reflect on their young adult’s experience is their level of stress related emotional arousal. Such stress is part and parcel of nonaccepting parents’ experience. As mentioned above, persistently nonaccepting parents typically present for ABFT-SGM with high levels of fear, shame and grief. According to the bio-behavioral model (Lieberman, Citation2007; Luyten et al., Citation2020; Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015; Satpute & Lieberman, Citation2006), when people are stressed and face threatening situations, they typically switch into an automatic mode of mentalization which allows them to make quick fight or flight decision. Such automatic mentalization, however, often leads to overly simplistic and biased assumptions about the minds of others and, consequently, problematic or maladaptive interpersonal responses. In contrast, when people are not overly stressed, they are able to mentalize in a more deliberate, controlled manner that allows for a more nuanced and accurate understanding of the mental states of others. This, in turn, leads to more adaptive and effective interpersonal responses, particularly in complex or ambiguous social situations (Luyten et al., Citation2020).

Indeed, some laboratory findings have shown that the presence of stress, and especially attachment-related stress, impedes or inhibits a person’s ability to mentalize (Luyten et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Nolte et al., Citation2013). For example, in one study of university students, higher levels of anger arousal led to a decreased ability to take the perspective of the other (Yip & Schweitzer, Citation2019). In contrast, other studies have found that stress improved mentalization. For example, in one study including both a sample of adults who had undergone inpatient treatment and a non-clinical sample of adults who had no mental health disorders, an attachment-related stress induction procedure led to an increase in affect-centered mentalization, as measured by the Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale (Lane et al., Citation1990), in the clinical group but not in the non-clinical group (Herrmann et al., Citation2018). In another study, including a group of individuals with borderline personality disorder, a group of individuals with Cluster C personality disorders and a non-clinical group, a social stress induction procedure led to increases in participants’ ability to recognize the affect of others based on a facial emotion recognition task across all three groups (Deckers et al., Citation2015). In yet another study, including a sample of depressed and healthy adults, activation of the attachment system was associated with both decreases and increases in mentalizing, depending on the individual’s attachment classification (i.e, secure, insecure or disorganized)(Fizke et al., Citation2013). Together, these findings suggest that stress related emotional arousal does impact upon mentalization, though the mixed findings suggest that the association is not simply linear.

One possibility is that the link between arousal and mentalization is curvilinear. In other words, a minimal amount of arousal may be required to activate the cognitive resources necessary to deliberately mentalize, but too much arousal may undermine mentalization. This hypothesis is consistent with the bio-behavioral model (Fonagy & Luyten, Citation2009), which suggests that when people reach a certain threshold of stress arousal, they switch from deliberate, controlled mentalization to automatic, reflexive mentalization. Indeed, findings from a two-year longitudinal study found that children with very high or very low emotional reactivity (based on teachers’ ratings) tended to have less developed abilities to take the perspective of others (Bengtsson & Arvidsson, Citation2011), suggesting that moderate levels of stress related arousal may be linked to optimal mentalization.

This hypothesis is also consistent with our clinical experience. Our clinical observations suggest that when parents feel threatened and are stressed (i.e., highly aroused), they have a harder time mentalizing about their young adult’s experience of feeling rejected. They are, instead, consumed by their own fear, shame or anger, leaving them unavailable to consider their child’s state of mind. On the other hand, when parents are insufficiently distressed about their young adult’s suffering, they are unmotivated to try to understand their young adult’s state of mind from a more open, curious position. In our clinical experience, parents are most likely to effectively reflect on their young adult’s experience when they are moderately aroused.

The current pilot study examined both the linear and curvilinear associations between parents’ level of emotional arousal and the degree to which they were able to mentalize about their young adult’s experience in the context of actual ABFT-SGM sessions. A unique feature of this study is that we measured parents’ in-session emotional arousal and reflective functioning on a moment-to-moment basis in the context of actual therapy sessions. To our knowledge, there has been only one previous study that examined the association between in-session emotional arousal and mentalization at the level of speech turns. Kivity et al. (Citation2021) examined sessions of dialectical behavioral therapy (Linehan, Citation2018), transference-focused therapy (Clarkin et al., Citation1999) and supportive psychodynamic therapy (Appelbaum, Citation2007) with clients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder. The researchers used vocal acoustic correlates to assess clients’ moment-by-moment emotional arousal and independently analyzed the transcripts of sessions to ascertain clients’ moment-by-moment level of reflective functioning. Results showed that higher levels of reflective functioning predicted lower emotional arousal during the same speech turn. On the other hand, level of emotional arousal did not predict the level of reflective functioning in the same speech turn. These researchers, however, did not examine the potential curvilinear relationship between arousal and reflective functioning.

Based on the biobehavioral model and our clinical observations, we hypothesized that the relationship between emotional arousal (EA) and reflective functioning (RF) during the act of reflecting would be curvilinear, such that moderate levels of EA would predict higher levels of RF.

Method

Participants

Participants were a subsample of six parents who had participated in an open clinical trial of attachment-based family therapy for sexual and gender minority young adults and their persistently nonaccepting parents (G. M. Diamond et al., Citation2022). In order to be included in the open clinical trial, the young adult had to: (a) self-identify as LGBTQ+; (b) be above the age of 20; (c) have disclosed their minority identity to their parents at least 12 months prior to being enrolled in the study; and (d) not be currently living with their parents. In addition, either the young adult or their parents needed to have reported elevated levels of either parental rejection or non-acceptance, as measured by the Parental Acceptance and Rejection of Sexual Orientation Scale (PARSOS; Kibrik et al., Citation2019).

The subsample of six parents in this study were selected because their level of reflective functioning had already been assessed as part of a previous study on reflective functioning and alliance in ABFT-SGM (Strifler et al., Citation2022). Each parent was from a different family. In order to minimize potential confounds related to the constellation of the sessions, only cases in which both parents attended all individual sessions with the therapist were considered. The number of individual sessions with parents ranged from 6 to 10 per case. Overall, across all parents, 43 therapy sessions were analyzed (n = 43). Parents ranged from 51 to 64 years of age. All parents identified as heterosexual and cisgender. Their adult children ranged in age from 20 to 35 years old. Five of the adult children identified as cisgender male and gay, and one identified as cisgender female and bisexual.

Treatment

Attachment-based family therapy for sexual and gender minority young adults and their nonaccepting parents (G. M. Diamond & Boruchovitz-Zamir, Citation2023) is specifically designed to reduce parental rejection and increase parental acceptance of their young adult’s sexual orientation or gender identity, and improve the quality of the attachment relationship. The treatment is manualized and time-limited (26 weeks). It is rooted in structural family therapy (Minuchin, Citation2018), multidimensional family therapy (Liddle, Citation2009), and emotion-focused therapy and theory (Greenberg, Citation2011), and was adapted from attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents (G. S. Diamond et al., Citation2014).

The treatment is comprised of five interrelated tasks, conducted in sequence. The first task, conducted during the initial conjoint session of treatment, is to form an initial bond with each family member and establish building closer, more open, mutually respectful relationships as the shared goal of treatment. The second task, conducted in the context of individual sessions with the young adult, is to build a strong therapeutic alliance with the young adult. The third task, conducted in the context of individual sessions with parents, is to build a strong therapeutic alliance with each parent. The fourth task, the attachment task, is the purported primary change mechanism of the treatment. This task, conducted in the context of conjoint sessions, consists of corrective attachment episodes. During such episodes, the young adult effectively communicates to their parents, often for the first time, their experience of feeling rejected and their unmet needs for safety and connection. At the same time, parents are helped to respond in an attuned, empathic, nondefensive, validating, and caring manner. Finally, after tension in the relationship has diminished, the fifth task of the treatment involves helping family members work collaboratively as they consider future shared challenges. Results from a recent open clinical trial of ABFT-SGM suggest that the treatment indeed facilitates parental acceptance, decreases parental rejection, and reduces attachment avoidance (G. M. Diamond et al., Citation2022)

Therapists

Treatment was delivered by six different therapists. One of the therapists, the second author, was a licensed clinical psychologist. One was a licensed clinical social worker, and the remaining four were advanced graduate clinical psychology interns. One of the therapists identified as a gay cisgender male, one as a cisgender heterosexual male, and the remaining four as cisgender heterosexual women. All of the therapists had previous training in family therapy, and all were trained to deliver ABFT-SGM and live supervised by the second author – the primary developer of the model.

Instruments

Parents’ nonacceptance and relationship specific reflective functioning

Parents’ in-session RF specific to their young adult’s experience of nonacceptance and the quality of their relationship with their young adult, was coded as part of a previous study (Strifler et al., Citation2022) using a modified version of the Reflective-Functioning Scale (RFS) (Fonagy et al., Citation1998). The RFS is an 11-point scale that was originally designed to evaluate the quality of RF based on narratives/transcripts from the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI; George et al., Citation1996). The modified version of the scale included three modifications to the original scale. The first was to narrow the target of the RF. Whereas the original scale assesses general RF, this modified version specifically assesses parents’ RF in regard to their young adult’s experience of nonacceptance and the quality of their relationship with their young adult. Second, the modified version allows coders to rate parents’ RF based on 30-second videotaped segments of therapy sessions. Third, the modified version includes only four levels of reflective functioning, as opposed to eleven. This is because: (a) levels −1 and 0 (i.e., negative RF) and 9 (i.e., exceptional RF) of the original scale did not manifest in the narratives of the clients in our sample; and (b) levels 2, 4, 6 and 8 of the original scale do not have defined anchors (i.e., they are intermediate scores), and thus could not be scored based on 30-second intervals.

The four levels of the modified version of the scale are as follows. “Distorted reflectivity” (“0”) was scored when parents defied an invitation for reflection, distorted the mental states of their young adult, and/or attributed evilness or hostility as underlining their young adult’s mental state (e.g., “How should I know why he thinks that? You’re the therapist! It’s your job to figure that out”). “Deficient reflectivity” (1) was scored when parents expressed rigid, closed narratives regarding their young adult’s mental state (or assumed mental state) or related to their young adult’s mental states (or assumed mental states) as invalid, confused, or arbitrary (e.g., “Every time I bring that up, he just lashes out at me for no reason”). “Intermediate reflectivity” (2) was scored when parents showed a minimal to moderate level of uncertainty regarding their current understanding of their young adult’s mental state, or curiosity about their young adult’s internal experience/point of view (e.g., “I’m not sure why, but I think that he gets very sensitive when we talk about his sexual orientation … ”). Finally, “High reflectivity” (3) was scored when parents showed a high level of openness and curiosity about their young adult’s mental states, and about the quality of their relationship with their young adult. This level depicts complex, elaborate or original reasoning about mental states while acknowledging the opaqueness of mental states (e.g., “I am just now beginning to understand how difficult it is for him being in the closet, it's like always hiding, concealing a part of yourself, it's hard … ”). Other researchers have also modified the RF scale in order to code pre-defined segments or speech turns from actual therapy sessions (Talia et al., Citation2019), and have obtained adequate inter-rater reliability (ICC = 0.86) (Kivity et al., Citation2021; Möller et al., Citation2017).

Coders used this modified version of the RF scale to code all 30-second segments in which parents spoke at least one sentence about their young adult’s experience of feeling unaccepted or about their relationship with their young adult. Only segments in which parents clearly referred to their young adult's mental state were coded. Only segments in which all coders independently agreed that the parent’s statement met all above-mentioned criteria were coded.

Client emotional arousal scale

Parents’ emotional arousal was observationally measured using the Client Emotional Arousal Scale III-Revised (CEAS-III-R; Warwar & Greenberg, Citation1999). The CEAS-III-R is a 7-point, observer-rated ordinal measure of clients’ expressed arousal. Average CEAS-III-R has been shown to predict treatment outcomes in psychotherapy (Greenberg et al., Citation2007; Missirlian et al., Citation2005). Observers use the scale to rate expressed emotion based on vocal accentuation patterns and vocal regularity of pace, as well as disruptions in speech patterns that occur under high arousal. An “emotional voice” is indicated by irregular patterns of accentuation and unexpected terminal contours with an uneven regularity of pace, all of which suggest aroused feelings. High CEAS-III-R levels indicate higher arousal intensities. Lower levels (i.e., 1 and 2) indicate restricted emotion. For example, Level 1 is when the client does not express emotions, and voice or gestures do not disclose any emotional arousal. Level 4 arousal is when there are moderate changes in voice and body movements. For example, emotional voice is present when ordinary speech patterns are moderately disrupted by emotional overflow as represented by changes in accentuation patterns, unevenness of pace, and changes in pitch. Level 7, in contrast, is when arousal is extremely high, reflected by both the person’s voice and body, and usual speech patterns are completely disrupted by emotional overflow (there is a falling-apart quality). When applying the rating scale, raters rate both the modal (most frequent) and peak levels of intensity of the client’s expressed emotional arousal during a given segment. Previous studies reported inter-rater reliability scores ranging from .75 to .81 (Carryer & Greenberg, Citation2010), which are considered excellent (Fleiss et al., Citation2013). In this study, all segments previously coded for level of parental reflective functioning in the Strifler and colleagues study (Strifler et al., Citation2022) were coded for level of emotional arousal.

Procedure

RF coder training and coding procedure

As part of the Strifler et al. (Citation2022) study, four undergraduate psychology students, naïve to the research hypothesis, coded parents’ RF. Coders were trained by the first author to use the adapted version of the RF scale. The trainer had participated in a RF training seminar with Howard Steele, one of the developers of the RF scale, and then worked closely with the research team to revise and manualize the scale to adapt it for the purposes of this study.

Coder training consisted of two initial meetings, three-hours in length each, dedicated to learning about the concept of RF. The next five weeks were dedicated to learning about the four levels of RF represented in the adapted scale. Videotaped therapy sessions drawn from the open clinical trial, but not included in the sample for this study, were used to train coders on the scale. These sessions were used to exemplify each level on the scale, and distinctions between levels of RF. Each weekly training session lasted two and half hours. Over the course of the subsequent two months, coders were assigned two practice videotaped sessions, not part of this study’s sample, to code each week. At the end of each week, they met with the trainer for two and half hours to discuss discrepancies in their coding. After reaching sufficient interrater reliability as a group (ICC [2,4] = >.70), coders began coding the sessions included in this study.

Two coders coded each session included in the study sample (n = 43). Sessions were assigned to coders based on a block-randomized rotating basis, such that each session was coded by a pair of raters, and all raters were paired an equal number of times with each of the other coders. During the coding phase, coders met weekly with the first author to discuss ratings in order to maintain reliability and avoid raters’ drift.

EA coder training and coding procedure

A second, independent group of three undergraduate psychology students, naïve to the research hypothesis, coded EA in each segment that was previously coded for RF. Coders were trained by the first author to use the CEAS scale (CEAS-III-R). Coder training consisted of two initial meetings of 90 min in length that included learning about the concept of EA, reading the CEAS-III-R manual and practice applying the scale to videotaped sessions not included in the study sample. Over the course of the subsequent seven weeks, coders were assigned two-to-three additional practice videotaped sessions, also not included in the study’s sample. At the end of each week, coders met with the trainer for a 90-minute group training session to discuss discrepancies in their coding. After reaching acceptable interrater reliability as a group, both on the modal (ICC [2,3] = .57) and peak ratings (ICC [2,3] = .60), tapes were assigned to pairs of coders on a randomized rotating basis. During the coding of actual study sessions, coders met weekly with the first author to discuss ratings in order to maintain reliability and avoid rater drift.

Results

Preliminary Results

Reliability of RF scores

In order to estimate the reliability of raters’ coding of RF, we calculated the interclass correlation coefficient using a one-way random-effects model. Results revealed an ICC[1,2] of .70 (F[337,338] = 3.32, p < .001, 95%CI [.627,.757]), indicating moderate to good reliability (Koo & Li, Citation2016).

Reliability of EA scores

In order to estimate the reliability of raters’ coding of EA, we calculated the interclass correlation coefficient using a one-way random-effects model. Results revealed an ICC [1,3] of .70 (F[191,384] = 3.35, p < .001, 95%CI [.620,.768]) for the peak EA scores, indicating moderate to good reliability, and an ICC[1,3] of .56 (F[191,384] = 2.29, p < .001, 95%CI [.445,.661]) for the modal EA scores, indicating poor to moderate reliability score. Due to the poor to moderate reliability scores of the EA modal ratings, and because there was a strong positive correlation between modal and peak scores r(334) = .76, p < .001, we conducted our analyses on the EA peak scores only.

Descriptive Statistics for Reflective Functioning

Descriptive statistics showing the average score for the overall reflectivity of each parent, as well as the RF score in the first and last individual session, according to each case, appear in .

Table I. Descriptive statistics for parental reflective functioning scores, based on 30-second segments.

Data Analytic Approach

In order to estimate the fluctuation of parents’ reflective functioning, and because the data was nested within case, we employed hierarchal linear modeling to account for dependency between measurements (Hox et al., Citation2017), with level-1 being emotional arousal at a given 30-second segment and level-2 being parent. This analytic approach is suitable and recommended for single-case designs such as ours (Shadish et al., Citation2013). Analyses were run using the nlme package (Pinheiro et al., Citation2017) in R (Core R Team, Citation2019). RF levels were grand-mean centered, and Emotional arousal levels were person-mean centered.

We ran two models in order to compare the fit of a linear multilevel model versus a quadratic multilevel model for parents reflective functioning. We predicted that RF would be higher at the moderate levels of EA and would decrease towards the lowest and highest levels of EA. Therefore, we expected that the curvilinear relationship between RF and EA would be a better fit than the linear relationship. In these models, the intercept was estimated as a random effect.

The following equations were used to model parents’ reflectivity score at segment j, for parent i:

The level-2 equation was:

The level-1 equation modeled parental reflectivity of parent i at segment j as a function of (i) the parent's intercept (β0i), (ii) the EA level on the 30-seconds segment (β1i), (iii) The square of the EA level, and (iv) and the level-1 residual term (eji). At level 2, the intercept of each parent (β0i) was modeled as a function of the sample’s intercept (γ00; fixed effect) and the parent’s random effect (U0i); In addition, the effect of the parent's EA level (β1i) was modeled as a function of the sample's fixed slope (γ10) and the parent's random slope (U1i). The quadratic term (β2i) was modeled only as a fixed effect (γ00), as including a random term did not improve the model fit (χ2 = .00, p = 1).

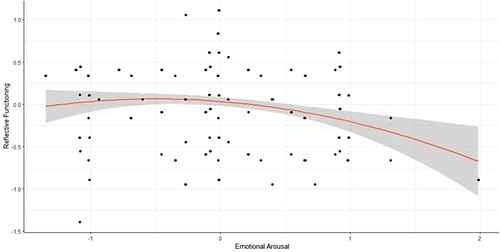

As shows, and in line with our hypothesis, the quadratic term for EA peak level was significant, evidencing a negative quadratic association between EA peak level and RF level (Est. = −.14, SE = .05, p = .006). In other words, parental RF level was higher when EA scores were moderate than when they were low or high. Also, when including time as a potential confound for levels of parents’ RF, the pattern of results remained unchanged. We also ran a linear multilevel model, without including the quadratic term as a predictor. This linear model was not significant (Est. = −.10, SE = .07, p = .23), and showed a poorer fit to the data than the quadratic model (χ2 = 7.25, p = 0.007). The fixed effects at level-1 explain 3.6% of within variance in parents’ level of RF in a given segment, analysis was run using the r2mlm package (Shaw et al., Citation2023). shows the scatter plot of reflective functioning scores by emotional arousal peak scores, with a smoothed means line. RF scores are grand-mean-centered, and EA scores are person-mean-centered.

Figure 1. Scatter plot of mean-centered reflective functioning levels by mean-centered emotional arousal peak levels, with a smoothed means line.

Table II. HLM model predicting RF by EA peak at the level of 30-second segments.

Discussion

The ability to deliberately and openly reflect upon others’ thoughts, feelings and intentions, or what has been called “reflective functioning” (Luyten et al., Citation2020), is crucial to forming and maintaining relationships. In the context of ABFT-SGM for LGBTQ+ young adults and their nonaccepting parents, parents’ ability to reflect upon the negative impact of their rejection of their young adult’s sexual orientation or gender identity on their young adult’s emotional welfare, and on their relationship with their young adult, is a critical element in promoting parental acceptance and repairing the young adult-parent attachment bond. Typically, when parents reflect upon their young adult’s experience of pain and loss associated with being rejected, their natural instinct to care for and support their young adult is activated, and motivation to accept their child is increased (G. M. Diamond & Boruchovitz-Zamir, Citation2023; Strifler et al., Citation2022).

Prior research and clinical experience suggest that parents’ level of emotional arousal may impact their capacity for reflective functioning and that too high or too low levels of emotional arousal may interfere with effective reflective functioning. Findings from this study provide further evidence of the link between parental reflective functioning and emotional arousal. Our findings showed that moderate levels of emotional arousal were associated with optimal parental reflective functioning. More specifically, when parents evidenced moderate levels of emotional arousal, they were better able to reflect on their young adult’s experience of feeling rejected in an open, curious, and accurate manner (e.g., Parent: “Maybe for him, when we don’t bring up this issue, he thinks that we don’t really care about it … or about him … ”) than when they were highly aroused or under aroused (e.g., Parent: “I really don’t know what he thinks—he is just overreacting!”).

Our findings showing that parents’ moderate levels of emotional arousal were associated with optimal reflective functioning are consistent with Fonagy and Luyten’s bio-behavioral model (Fonagy & Luyten, Citation2009; Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015). The bio-behavioral model suggests that sufficient stress related arousal may be necessary to engage in controlled, deliberate reflective functioning, while very high levels of stress related arousal may lead to a switch to an automatic, reflexive and potentially less nuanced and less accurate mode of mentalizing. This relationship between stress and mentalization may be best represented by an inverted U-curve, whereby increases in stress lead to better mentalization up to a “switch point,” at which arousal becomes so high that it has the opposite effect, causing a shift to pre-mentalizing modes of functioning (Herrmann et al., Citation2018; Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the curvilinear relationship between emotional arousal and reflective functioning. A number of prior studies have examined the linear function between arousal and reflective functioning among both clinical and community samples, with mixed results. Results from some studies found that stress related arousal was associated with poorer reflective functioning. For example, Nolte et al. (Citation2013) found that stress related arousal was associated with reduced accuracy and reaction times in a reading the mind in the eyes task. In another study, employing an emotion recognition task to capture level of mentalizing, higher levels of stress related arousal were associated with poorer mentalizing, but only among participants with disorganized attachment representation (Fizke et al., Citation2013). In yet a third study, Yip and Schweitzer (Citation2019) found that higher levels of anger arousal predicted lower levels of perspective taking. On the other hand, some studies have found that stress related arousal was linked to improved reflective functioning, manifested as more accurate emotional face recognition in patients with borderline personality disorder (Smeets et al., Citation2009), better affect centered mentalization in psychosomatic patients (Herrmann et al., Citation2018) and more accurate facial emotion recognition among both patients with personality disorders and non-clinical participants (Deckers et al., Citation2015). These mixed and seemingly contradictory findings from prior research may be explained by the fact that different studies generated different levels of stress arousal, that arousal was often measured as a dichotomous variable, and that the curvilinear function between arousal and mentalizing was not explored.

This is also one of only two studies to examine the link between emotional arousal and reflective functioning in actual psychotherapy sessions as opposed to highly controlled, laboratory conditions. This is important because, unlike laboratory conditions, psychotherapy involves reflecting upon one’s own mind, and the minds of significant others, in the context of what are usually complex, emotionally laden and meaningful relationships. Examining the link between arousal and reflective functioning in psychotherapy provides a more contextualized and ecologically valid test of the association context between the two processes. In the only other study on reflectivity in the context of psychotherapy of which we are aware, Kivity et al. (Citation2021) found that higher levels of in-session client reflective functioning were linked to lower levels of emotional arousal, and suggested that reflective functioning led to a down regulation of emotional arousal. While it seems reasonable to propose that reflective functioning impacts upon emotional arousal, it seems equally reasonable that emotional arousal impacts upon reflective functioning. Most likely, the effects of these two variables are bidirectional and future research using temporal designs should attempt to disentangle the effect of arousal on reflective function and the effect of reflective functioning on arousal.

Our finding showing a link between stress related arousal and parents’ reflective functioning has important clinical implications. In the context of ABFT-SGM for LGBTQ+ young adults and their nonaccepting parents, it suggests that therapists would do well to first assess parents’ level of stress related emotional arousal before inviting them to reflect on their young adult’s feelings, attributions and behaviors. This is particularly important when working with nonaccepting parents, who commonly present for therapy in a high state of distress. Inviting such parents to reflect on their child’s experience while they are still consumed by their own fears, hurt, shame, grief, frustration and anger is not likely to be effective, and has the potential to cause a rupture in the therapeutic relationship. In such moments, parents may feel as though the therapist is minimizing or somehow insensitive to their feelings and experiences as parents of a sexual or gender minority young adult, reflecting an empathic failure. In contrast, those moments when parents are sufficiently aroused but still able to regulate their emotions may be an opportunity to invite parents to engage in reflective functioning.

This finding also has implications for other LGBTQ+ affirmative treatments from other orientations. For example, cognitive behavioral treatments for LGBTQ+ adults typically include in vivo exposure tasks to reduce avoidance and increase assertiveness (Burton et al., Citation2019). When parental rejection is a core stressor, clients are prepared to approach parents, be assertive and set healthy boundaries. Our findings suggest that it might be helpful to teach LGBTQ+ clients to assess and monitor their parents’ level of arousal before and during such interactions, in order to determine when parents’ level of arousal leaves them capable of engaging in productive conversations and interactions, and when such conversations and interactions are best left for another time and place. Our findings may also have implications for those who lead parent groups for nonaccepting parents, such as those groups run by Parents and Friends for Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG). Such groups, prevalent not only in the U.S. but across the world, provide both support and important tips for parents struggling to accept their LGBTQ+ child. One potentially helpful psychoeducational component of such groups might be to help parents be aware of and learn how to regulate their level of arousal in order remain within their own window of tolerance and be able to productively participate in constructive conversation with their LGBTQ+ child around emotionally laden, conflictual topics.

Our study has a number of methodological strengths. First, it was conducted on actual therapy sessions, rather than laboratory-based interactions. This contributed to the ecological validity of our results. Second, independent, objective raters were able to reach good interrater reliability when observationally coding parents’ RF and EA at 30-second intervals. The ability to obtain reliable measures of these processes at such short intervals provides the opportunity to examine how these processes unfold over time, and their relation to one another, in future studies. Third, we adapted the RF scale to capture parents’ reflective functioning specifically related to their young adult’s experience of rejection, and the quality of their relationship with their young adult. This is important since these domains were the reason why family members came for the therapy, and prior research has shown that reflective functioning is not necessarily even across relationships and situations (Luyten et al., Citation2020; Luyten & Fonagy, Citation2015).

With that said, our results must be interpreted within the context of several noteworthy methodological limitations. First, the sample size was small. This was due to the labor-intensive nature of the data collection procedure. Our results need to be replicated with a larger sample of clients. Second, because we did not have a series of adjacent RF and EA scores, we could not examine the directionality of the effects. Future research with multiple, repeated, and continuous measures of both variables could potentially shed light on the temporal nature of this relationship. Third, this is the first time this adaptation of the RF scale has been used. More psychometric data regarding the scale’s reliability and validity needs to be gathered.

Even considering these limitations, the results of this pilot study have potentially important research and clinical implications. Our results provide some of the first data regarding the association between emotional arousal and mentalization in the context of psychotherapy and speaks to the importance of considering clients’ level of emotional arousal before inviting them to mentalize. One important but yet unexamined question is whether the link between EA and RF differs according to discrete emotions. It may be, for example, that while high levels of fear or anger impair mentalizing, high levels of sadness interfere less with mentalizing. Future psychotherapy research could potentially disentangle these potentially differential effects and provide clinical guidance for therapists as they navigate between helping clients connect with their emotions and reflect on the experience of others.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allen, J. P., & Hauser, S. T. (1996). Autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of young adults’ states of mind regarding attachment. Development and Psychopathology, 8(4), 793–809. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400007434

- Appelbaum, A. H. (2007). Supportive psychotherapy. In J. M. Oldham, A. E. Skodol, & D. S. Bender (Eds.), The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of personality disorders (pp. 311–326). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Beals, K. P., & Peplau, L. A. (2006). Disclosure patterns within social networks of gay men and lesbians. Journal of Homosexuality, 51(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v51n02_06

- Bengtsson, H., & Arvidsson, Å. (2011). The impact of developing social perspective-taking skills on emotionality in middle and late childhood. Social Development, 20(2), 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00587.x

- Białecka-Pikul, M., Stępień-Nycz, M., Szpak, M., Grygiel, P., Bosacki, S., Devine, R. T., & Hughes, C. (2021). Theory of mind and peer attachment in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 1202–1217. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12630

- Bochicchio, L., Reeder, K., Ivanoff, A., Pope, H., & Stefancic, A. (2022). Psychotherapeutic interventions for LGBTQ+ youth: A systematic review. Journal of LGBT Youth, 19(2), 152–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2020.1766393

- Bosacki, S., & Wilde Astington, J. (1999). Theory of mind in preadolescence: Relations between social understanding and social competence. Social Development, 8(2), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00093

- Bouris, A., Guilamo-Ramos, V., Pickard, A., Shiu, C., Loosier, P. S., Dittus, P., Gloppen, K., & Michael Waldmiller, J. (2010). A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(5–6), 273–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-010-0229-1

- Burton, C. L., Wang, K., & Pachankis, J. E. (2019). Psychotherapy for the spectrum of sexual minority stress: Application and technique of the ESTEEM treatment model. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 26(2), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2017.05.001

- Camoirano, A. (2017). Mentalizing makes parenting work: A review about parental reflective functioning and clinical interventions to improve it. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00014

- Carryer, J. R., & Greenberg, L. S. (2010). Optimal levels of emotional arousal in experiential therapy of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018401

- Clarkin, J. F., Yeomans, F. E., & Kernberg, O. F. (1999). Psychotherapy for borderline personality. Wiley.

- Core R Team. (2019). A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2. http://www.r-project.org

- Coulter, R. W. S., Kinsky, S. M., Herrick, A. L., Stall, R. D., & Bauermeister, J. A. (2015). Evidence of syndemics and sexuality-related discrimination among young sexual-minority women. LGBT Health, 2(3), 250–257. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2014.0063

- Cramer, D. W., & Roach, A. J. (1988). Coming out to mom and dad: A study of gay males and their relationships with their parents. Journal of Homosexuality, 15(3–4), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v15n03_04

- D’augelli, A. R. (2002). Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(3), 433–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104502007003010

- Deckers, J. W. M., Lobbestael, J., Van Wingen, G. A., Kessels, R. P. C., Arntz, A., & Egger, J. I. M. (2015). The influence of stress on social cognition in patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 52, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.11.003

- Diamond, G. M., & Boruchovitz-Zamir, R. (2023). Attachment-based family therapy for sexual and gender minority young adults and their nonaccepting parents. American Psychological Association.

- Diamond, G. M., Boruchovitz-Zamir, R., Nir-Gotlieb, O., Gat, I., Bar-Kalifa, E., Fitoussi, P., & Katz, S. (2022). Attachment-based family therapy for sexual and gender minority young adults and their nonaccepting parents. Family Process, 61(2), 530–548.

- Diamond, G. S., Diamond, G. M., & Levy, S. A. (2014). Attachment-based family therapy for depressed adolescents. American Psychological Association.

- DiMaggio, D. J. (2020). What contributes to marital satisfaction? The relationship between attachment style, emotion regulation, mentalization and marital satisfaction. Alliant International University.

- Eisenberg, M. E., & Resnick, M. D. (2006). Suicidality among gay, lesbian and bisexual youth: The role of protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(5), 662–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.024

- Eldahan, A. I., Pachankis, J. E., Rendina, H. J., Ventuneac, A., Grov, C., & Parsons, J. T. (2016). Daily minority stress and affect among gay and bisexual men: A 30-day diary study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 190, 828–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.066

- Elizur, Y., & Ziv, M. (2001). Family support and acceptance, gay male identity formation, and psychological adjustment: A path model*. Family Process, 40(2), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4020100125.x

- Fizke, E., Buchheim, A., & Juen, F. (2013). Activation of the attachment system and mentalization in depressive and healthy individuals: An experimental control study. Psihologija, 46(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI1302161F

- Fleiss, J. L., Levin, B., & Paik, M. C. (2013). Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Wiley.

- Fonagy, P., & Luyten, P. (2009). A developmental, mentalization-based approach to the understanding and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 21(4), 1355–1381. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409990198

- Fonagy, P., Target, M., Steele, H., & Steele, M. (1998). Reflective-functioning manual, version 5.0, for application to adult attachment interviews (pp. 161–162). University College London.

- Freeman, C. (2016). What is mentalizing? An overview. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 32(2), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12220

- George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1996). Adult attachment interview.

- Greenberg, L. S. (2011). Emotion-focused therapy. American Psychological Association.

- Greenberg, L. S., Auszra, L., & Herrmann, I. R. (2007). The relationship among emotional productivity, emotional arousal and outcome in experiential therapy of depression. Psychotherapy Research, 17(4), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300600977800

- Grossman, A. H., Park, J. Y., Frank, J. A., & Russell, S. T. (2021). Parental responses to transgender and gender nonconforming youth: Associations with parent support, parental abuse, and youths’ psychological adjustment. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(8), 1260–1277. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1696103

- Haas, A. P., Eliason, M., Mays, V. M., Mathy, R. M., Cochran, S. D., D’Augelli, A. R., Silverman, M. M., Fisher, P. W., Hughes, T., Rosario, M., Russell, S. T., Malley, E., Reed, J., Litts, D. A., Haller, E., Sell, R. L., Remafedi, G., Bradford, J., Beautrais, A. L., … Clayton, P. J. (2010). Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, Gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: Review and recommendations. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(1), 10–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.534038

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Dovidio, J. F., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Phills, C. E. (2009). An implicit measure of anti-gay attitudes: Prospective associations with emotion regulation strategies and psychological distress. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(6), 1316–1320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.08.005

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Pachankis, J. E. (2016). Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: Research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatric Clinics, 63(6), 985–997.

- Herrmann, A. S., Beutel, M. E., Gerzymisch, K., Lane, R. D., Pastore-Molitor, J., Wiltink, J., Zwerenz, R., Banerjee, M., & Subic-Wrana, C. (2018). The impact of attachment distress on affect-centered mentalization: An experimental study in psychosomatic patients and healthy adults. PLoS One, 13(4), e0195430. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195430

- Hershberger, S. L., & D’Augelli, A. R. (1995). The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology, 31(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.31.1.65

- Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & Van de Schoot, R. (2017). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Routledge.

- Hoy-Ellis, C. P. (2023). Minority stress and mental health: A review of the literature. Journal of Homosexuality, 70(5), 806–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.2004794

- Jessee, A., Mangelsdorf, S. C., Wong, M. S., Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Shigeto, A., & Brown, G. L. (2018). The role of reflective functioning in predicting marital and coparenting quality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(1), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0874-6

- Kibrik, E. L., Cohen, N., Stolowicz-Melman, D., Levy, A., Boruchovitz-Zamir, R., & Diamond, G. M. (2019). Measuring adult children’s perceptions of their parents’ acceptance and rejection of their sexual orientation: Initial development of the Parental Acceptance and Rejection of Sexual Orientation Scale (PARSOS). Journal of Homosexuality, 66(11), 1513–1534. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1503460

- Kiekens, W., la Roi, C., Bos, H. M. W., Kretschmer, T., van Bergen, D. D., & Veenstra, R. (2020). Explaining health disparities between heterosexual and LGB adolescents by integrating the minority stress and psychological mediation frameworks: Findings from the TRAILS study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(9), 1767–1782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01206-0

- Kivity, Y., Levy, K. N., Kelly, K. M., & Clarkin, J. F. (2021). In-session reflective functioning in psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: The emotion regulatory role of reflective functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(9), 751–761. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000674

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

- Lane, R. D., Quinlan, D. M., Schwartz, G. E., Walker, P. A., & Zeitlin, S. B. (1990). The levels of emotional awareness scale: A cognitive-developmental measure of emotion. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55(1–2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.1990.9674052

- Lehavot, K., & Simoni, J. M. (2011). The impact of minority stress on mental health and substance use among sexual minority women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022839

- Liddle, H. A. (2009). Multidimensional family therapy: A science-based treatment system for adolescent drug abuse. In The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of family psychology (pp. 341–354). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444310238.ch23

- Lieberman, M. D. (2007). Social cognitive neuroscience: A review of core processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 259–289. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085654

- Linehan, M. M. (2018). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Publications.

- Luyten, P., Campbell, C., Allison, E., & Fonagy, P. (2020). The mentalizing approach to psychopathology: State of the art and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16(1), 297–325. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-071919-015355

- Luyten, P., & Fonagy, P. (2015). The neurobiology of mentalizing. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 6(4), 366–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000117

- Luyten, P., Malcorps, S., Fonagy, P., & Ensink, K. (2019). Assessment of mentalizing. In Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice (pp. 37–62). American Psychological Association.

- Menashe-Grinberg, A., Shneor, S., Meiri, G., & Atzaba-Poria, N. (2021). Improving the parent–child relationship and child adjustment through parental reflective functioning group intervention. Attachment & Human Development, 24(2), 208-228.

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Minuchin, S. (2018). Families and family therapy. Routledge.

- Missirlian, T. M., Toukmanian, S. G., Warwar, S. H., & Greenberg, L. S. (2005). Emotional arousal, client perceptual processing, and the working alliance in experiential psychotherapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 861–871. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.861

- Möller, C., Karlgren, L., Sandell, A., Falkenström, F., & Philips, B. (2017). Mentalization-based therapy adherence and competence stimulates in-session mentalization in psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder with co-morbid substance dependence. Psychotherapy Research, 27(6), 749–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2016.1158433

- Needham, B. L., & Austin, E. L. (2010). Sexual orientation, parental support, and health during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1189–1198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9533-6

- Nolte, T., Bolling, D. Z., Hudac, C., Fonagy, P., Mayes, L. C., & Pelphrey, K. A. (2013). Brain mechanisms underlying the impact of attachment-related stress on social cognition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 816. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00816

- Nurius, P. S., & Hoy-Ellis, C. P. (2013). Stress effects on health. In C. Franklin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of social work online (pp. 1–16). New York: NASW & Oxford University Press. Retrieved August 22, 2016, from http://socialwork.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.001.0001/acrefore-9780199975839-e-1045?rskey=f3iOcW&result=10.

- Ordway, M. R., Webb, D., Sadler, L. S., & Slade, A. (2015). Parental reflective functioning: An approach to enhancing parent-child relationships in pediatric primary care. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 29(4), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.12.002

- Pachankis, J. E. (2014). Uncovering clinical principles and techniques to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21(4), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12078

- Pachankis, J. E., Sullivan, T. J., Feinstein, B. A., & Newcomb, M. E. (2018). Young adult gay and bisexual men’s stigma experiences and mental health: An 8-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 54(7), 1381–1393. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000518

- Parra, L. A., Bell, T. S., Benibgui, M., Helm, J. L., & Hastings, P. D. (2018). The buffering effect of peer support on the links between family rejection and psychosocial adjustment in LGB emerging adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(6), 854–871. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517699713

- Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., Sarkar, D., Heisterkamp, S., Van Willigen, B., & Maintainer, R. (2017). Package ‘nlme’. Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models, Version, 3(1).

- Raifman, J., Moscoe, E., Austin, S. B., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Galea, S. (2018). Association of state laws permitting denial of services to same-sex couples with mental distress in sexual minority adults: A difference-in-difference-in-differences analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(7), 671–677. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0757

- Ryan, C., Huebner, D., Diaz, R. M., & Sanchez, J. (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123(1), 346–352. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3524

- Ryan, C., Russell, S. T., Huebner, D., Diaz, R., & Sanchez, J. (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(4), 205–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x

- Salo, S. J., Pajulo, M., Vinzce, L., Raittila, S., Sourander, J., & Kalland, M. (2021). Parent relationship satisfaction and reflective functioning as predictors of emotional availability and infant behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(5), 1214–1228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-01934-2

- Samarova, V., Shilo, G., & Diamond, G. M. (2014). Changes in youths’ perceived parental acceptance of their sexual minority status over time. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(4), 681–688. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12071

- Satpute, A. B., & Lieberman, M. D. (2006). Integrating automatic and controlled processes into neurocognitive models of social cognition. Brain Research, 1079(1), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.005

- Savin-Williams, R. C. (1989). Parental influences on the self-esteem of gay and lesbian youths. Journal of Homosexuality, 17(1–2), 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v17n01_04

- Shadish, W. R., Kyse, E. N., & Rindskopf, D. M. (2013). Analyzing data from single-case designs using multilevel models: New applications and some agenda items for future research. Psychological Methods, 18(3), 385–405. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032964

- Shaw, M., Rights, J. D., Sterba, S. S., & Flake, J. K. (2023). r2mlm: An R package calculating R-squared measures for multilevel models. Behavior Research Methods, 55(4), 1942–1964. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01841-4

- Sheets, R. L., Jr., & Mohr, J. J. (2009). Perceived social support from friends and family and psychosocial functioning in bisexual young adult college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.56.1.152

- Shilo, G., Antebi, N., & Mor, Z. (2015). Individual and community resilience factors among lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer and questioning youth and adults in Israel. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(1–2), 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-014-9693-8

- Smeets, T., Dziobek, I., & Wolf, O. T. (2009). Social cognition under stress: Differential effects of stress-induced cortisol elevations in healthy young men and women. Hormones and Behavior, 55(4), 507–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.01.011

- Stone Fish, L., & Harvey, R. G. (2005). Nurturing queer youth: Family therapy transformed. WW Norton & Co.

- Strifler, Y., Zisenwine, T., & Diamond, G. M. (2022). Parents’ reflective functioning and their agreement on treatment goals in attachment-based family for sexual and gender minority young adults and their nonaccepting parents. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 48(4), 982–997. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12581

- Talia, A., Miller-Bottome, M., Katznelson, H., Pedersen, S. H., Steele, H., Schröder, P., Origlieri, A., Scharff, F. B., Giovanardi, G., Andersson, M., Lingiardi, V., Safran, J. D., Lunn, S., Poulsen, S., & Taubner, S. (2019). Mentalizing in the presence of another: Measuring reflective functioning and attachment in the therapy process. Psychotherapy Research, 29(5), 652–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1417651

- Warwar, S., & Greenberg, L. S. (1999). Client emotional arousal scale–III. Unpublished Manuscript, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

- Werner, A. M., Tibubos, A. N., Rohrmann, S., & Reiss, N. (2019). The clinical trait self-criticism and its relation to psychopathology: A systematic review–update. Journal of Affective Disorders, 246, 530–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.069

- Yip, J. A., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2019). Losing your temper and your perspective: Anger reduces perspective-taking. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 150, 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.07.003