Abstract

Objective:

There are significant temporal and financial barriers for individuals with personality disorders (PD) receiving evidence-based psychological treatments. Emerging research indicates Group Schema Therapy (GST) may be an accessible, efficient, and cost-effective PD intervention, however, there has been no synthesis of the available evidence to date. This review therefore aimed to investigate the efficacy of GST for PDs by systematically synthesizing available literature.

Method:

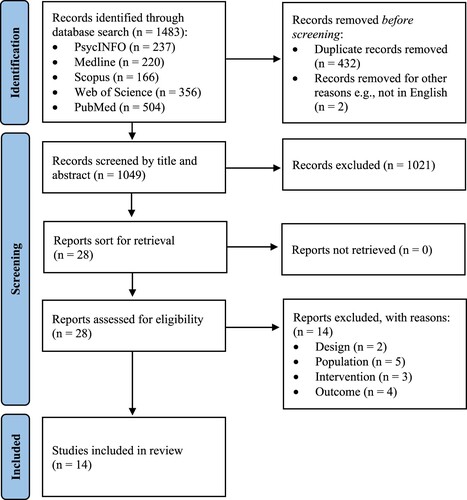

Five electronic databases were screened with resulting studies subjected to a specific eligibility criteria, which yielded fourteen relevant studies. Characteristics were extracted and methodological quality rigorously assessed.

Results:

Strong support was evidenced for GST’s ability to reduce Cluster B and C symptomology, particularly for Borderline and Avoidant PD. GST appeared to improve global symptom severity, quality of life and functional capacity, as well as treatment targets such as schemas and modes.

Conclusion:

Although not without limitations and a moderate risk of bias, the current body of evidence supports GST as a potential solution to current service deficits in economical and evidence-based care for individuals with PD. Implications for treatment and future research are discussed.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: There is promising preliminary evidence in support of the efficacy of Group Schema Therapy GST for personality disorders (PD). Specifically, for Borderline PD, and Cluster B and C PDs more broadly, GST can lead to improvements in PD symptom severity; global and specific symptom severity; quality of life; functional capacity; and treatment-related process outcomes such as schemas and modes.

Schema Therapy (ST; Young, Citation1999) is an integrative treatment, for a diverse range of psychopathology, that draws upon cognitive–behavioral, psychodynamic, gestalt and object relations theory principles and techniques. ST arose primarily from Young et al.’s (Citation2003) attempts to provide more effective treatment for patients with a personality disorder (PD). A PD is a severe mental condition characterized by a pervasive, inflexible pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from cultural expectations and leads to clinically significant distress and impairment (American Psychiatric Association; APA, Citation2013). The prevalence rate of PDs ranges from 4% to 15% in community samples (Eaton & Greene, Citation2018; Weissman, Citation1993; Torgersen et al., Citation2001; Coid et al., Citation2006), from 21% to 51% in psychiatric outpatient settings (Moran et al., Citation2000; Beckwith et al., Citation2014), and up to 68% in forensic inpatient settings (Fazel & Danesh, Citation2002). A PD diagnosis is associated with increased mortality rates (Fok et al., Citation2012), greater likelihood of treatment dropout and comorbidities (Davidson et al., Citation2010), higher rates of smoking and substance misuse (Frankenburg & Zanarini, Citation2004), and increased rates of unemployment and criminal activity (Cruitt & Oltmanns, Citation2019), than those without.

Individuals with PDs tend to demonstrate life-long patterns of over- or under-developed capacities that result from the interaction of genetic predisposition, unmet core needs during childhood, and early environmental conditions (Barazandeh et al., Citation2016; Beck et al., Citation2004). ST terms these life-long patterns as “Early Maladaptive Schemas” (EMS), which encompass beliefs about oneself, others and the world, as well as memories, somatic sensations, emotions, behaviors and cognitions. There are currently 18 recognized EMSs, and once activated, individuals attempt to cope with the subsequent schema-related distress via avoidance, surrender or over-compensation (Young et al., Citation2003). More recent literature focusses on Schema “modes,” which are emotional, protective, or critical “parts,” or temporary states, that can be activated by underlying EMS “traits.” Schema modes are of particular empirical and clinical significance as they may be more responsive to intervention than EMSs (Jacob & Arntz, Citation2013; Young et al., Citation2003). Replacing the dysfunctional behavioral patterns of EMSs and modes with more adaptive strategies ultimately enables core unmet needs to be met and is the primary treatment goal of ST (Jacob & Arntz, Citation2013; Young et al., Citation2003). Beyond behavioral skills and symptom change, there is facilitation of fundamental personality change by reducing the intensity of EMSs and modes that trigger under- or over-modulated emotion (Farrell et al., Citation2014).

1.1. Efficacy of Schema Therapy for Personality Disorders

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have supported ST’s efficacy for improving PD symptoms and EMS severity (Taylor et al., Citation2017; Nadort et al., Citation2009), reducing emotion dysregulation (Dadomo et al., Citation2016), and resulting in diagnostic remission (Jacob & Arntz, Citation2013; Bamelis et al., Citation2014). ST has lower treatment dropout rates than competing PD therapies such as Transference-Focused Psychotherapy (Giesen-Bloo et al., Citation2006; Gülüm, Citation2018) and sustainable therapeutic gains when assessed at six-, 12- and 36-month follow-up (Nordahl & Nysaeter, Citation2005; Fassbinder et al., Citation2016; Nadort et al., Citation2009). Large treatment effect sizes observed in PD populations to date may be attributed ST’s all-encompassing integration of cognitive, behavioral, experiential, and relational techniques that may facilitate a deeper, longer-lasting personality change than competing interventions (Giesen-Bloo et al., Citation2006; Farrell et al., Citation2009). Alternative approaches to PD treatment that heavily focus on primarily cognitive, behavioral, experiential, or relational interventions tend to neglect one or more of the other components. This holistic integration is integral to ST’s model and its emphasis on needs, quality of life, and recovery rather than symptomatic reduction in isolation (Van Asselt et al., Citation2008; Nordahl & Nysaeter, 2005).

While ST treatment length can be highly variable due to differences in pervasiveness, complexity of symptoms, and patient engagement (Young et al., Citation2003), the approach is considered long-term, typically six to 24 months (e.g. Van Vreeswijk et al., Citation2014; Nadort et al., Citation2009). Hence, considerable cost to patients and the healthcare system are associated with individual ST (Bamelis et al., Citation2015), which significantly limits the intervention’s accessibility. Iliakis and colleagues’ (Citation2019) analysis of the supply of—and demand for—PD treatments found that the ratio of treatment-seeking PD patients to mental health professionals with training in evidence-based PD interventions ranges from approximately 2878 to 1 in Australia, to 5933 to 1 in the United States. Given the evidence base for ST, the prevalence rates of PDs, and the temporal and financial barriers of ST for individuals, there are compelling economic and service delivery reasons to consider a group psychotherapy modality.

1.2. Group Schema Therapy

Supportive peer interactions, a sense of belonging and universality, vicarious and observational learning, opportunities for in vivo practice and the instillation of hope are amongst several therapeutic factors with curative properties thought to be enhanced in a group therapy modality (Yalom, Citation1995; Burlingame et al., Citation2004). Farrell and Shaw (Citation2012) outline a Group Schema Therapy (GST) model that is theoretically consistent with the individual ST model, albeit with some practical adaptations. For example, it is essential to redirect the focus of limited reparenting in individual ST—a therapeutic style of “acting as a good parent would in meeting child mode needs within the bounds of an appropriate therapy relationship” (Farrell et al., Citation2014, p. 10)—to balancing the collective needs of the group as a parent would for siblings, in group reparenting. The group provides opportunity beyond that of the therapist for emotional learning, socialization, conflict resolution and relationship management. As the impairment of PDs is largely interpersonal, Farrell and colleagues (Citation2014) assert that “such a setting rich in interpersonal interaction is particularly well-suited to providing the required corrective emotional experiences” (p. 35).

Farrell et al. (Citation2009) provided the first formal investigation of GST, with the authors observing clinically significant reductions in BPD symptoms, severity of global psychiatric symptoms, and improvements in global functioning when compared to treatment as usual (TAU), with large effects that were sustained at six-month follow up. This study was the first of its kind and evidenced strong preliminary support for GST as an effective treatment for BPD, although the growing body of evidence that has emerged in its wake has not been reviewed in a systematic way. Since group therapy is the most commonly employed treatment modality in inpatient settings (Reiss et al., Citation2014)—where PDs in general have the highest prevalence—it is of the utmost clinical importance to extend the empirical knowledge and application of GST to BPD and other PDs.

1.3. The Current Review

A number of literary and systematic reviews have been conducted exploring individual ST applications for PDs (e.g. Jacob & Arntz, Citation2013; Masley et al., Citation2012; Dadomo et al., Citation2018). However, the authors are not aware of any attempt to date to systematically review the emerging empirical evidence for the efficacy of GST for PDs, despite a need for a more holistic, efficient and cost-effective treatment for this population. Given the empirical, theoretical, and clinical significance of determining the efficacy of GST for PDs, the current review aims to amalgamate empirical evidence and evaluate the efficacy of GST outcomes in PD populations. Second, it aims to appraise the resulting body of evidence’s methodological quality, identify limitations, and propose meaningful future research directions. Third, it aims to provide a synthesis of the literature and consider the broader clinical implications essential in aiding mental health practitioners to provide economical and evidence-based care to their patients with PDs.

2. Method

2.1. Protocol and Registration

The current systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Page et al., Citation2021) reporting standards. Its protocol was pre-registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022309451) and conducted in accordance with Cochrane’s Handbook for systematic reviews (Higgins & Green, Citation2011).

2.2. Search Strategy

The key search terms outlined in were applied in a multi-field format to comprehensively screen PsycINFO, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed on the 14th of August 2023. The reference lists of all included studies were manually examined to ensure that additional studies of relevance were not inadvertently omitted in the initial search of databases.

Table I. Key words and search terms utilized in the electronic database screening.

2.3. Study Selection

The records identified through the database research were imported into EndNote, a commonly used software package utilized in systematic and meta-analytic reviews (Peters, Citation2017; Peters et al., Citation2015). After the removal of duplicate studies, titles and abstracts were screened by the first author (MT). Twenty percent of studies at the title and abstract stage were double-screened by an auxiliary reviewer, with an 98% inter-rater reliability. All remaining manuscripts were appraised for eligibility at the full-text level by both the first (MT) and third author (AN). Any disagreement between reviewers regarding the eligibility of studies was resolved through collaborative discussion.

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

To be included in the current review studies were required to: (a) be published in a peer-reviewed journal; (b) be published in English language; (c) be empirical in design; (d) include a population of participants who met criteria for one or more PD as identified by a recognized diagnostic system, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; APA, Citation2013); (e) evaluate a psychological intervention via a group modality, with the primary treatment component being within an ST framework; and (f) report outcomes pertaining to the efficacy of the intervention with particular relevance to the target population.

2.4.1. Design

Non-empirical research such as commentaries and literary reviews (e.g., Bachrach & Arntz, Citation2021; Tan et al., Citation2018) were excluded.

2.4.2. Population

Participants who did not meet criteria for one or more PD as identified by a recognized diagnostic system, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; APA, Citation2013) were also excluded (e.g., Renner et al., Citation2013; Schaap et al., Citation2016; Van Vreeswijk et al., Citation2014, Citation2020; Younan et al, Citation2018).

2.4.3. Intervention

Studies that did not apply a primary ST intervention component via a group modality were excluded. Interventions were deemed consistent with true ST if the intervention included cognitive, behavioral, experiential, and relational components (see Farrell et al.’s [Citation2014] manual for a comprehensive overview). ST that was delivered exclusively individually (e.g., Van den Broek et al., Citation2011) or only within a psychoeducational capacity without an active intervention component (e.g., Leppänen et al., Citation2015, Citation2016) resulted in exclusion.

2.4.4. Outcome

Studies were excluded if they omitted, or failed to investigate, outcomes pertaining to the efficacy of the intervention provided with particular relevance to the target population. For example, studies that explored process-oriented outcomes not specific to a particular treatment (e.g., Tschacher et al., Citation2012; Van Dijk et al., Citation2020) or only provided commentary on a treatment protocol (e.g., Lowenstein et al., Citation2020; Van Dijk et al., Citation2019) were excluded.

2.5. Data Extraction

Two standardized extraction forms derived specifically from the aims of the current review was applied by the first (MT) and third (AN) author independently to extract and record key data, with any incongruences resolved via collaborative discussion or consultation with the second author (EP). The first extraction form obtained information pertaining to study design, population, setting and other methodological characteristics of interest, while the second provides a summary of key characteristics of the interventions provided and their subsequent within- and between-group outcomes (see and , respectively).

Table II. Design, population and methodological characteristics of included studies.

Table III. Intervention characteristics and treatment outcomes of included studies.

2.6. Assessment of Methodological Quality

In light of the diversity in study design, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Hong et al., Citation2018) was considered the most appropriate tool to assess the methodological quality of the current body of evidence (Oliveira et al., Citation2021; Souto et al., Citation2015; Crowe & Sheppard, Citation2011). The answer to each of the five questions pertaining to the study’s design was answered with “yes” (Y), “no” (N) or “cannot tell” (CT). As a comparison of results over the calculation of an overall score is encouraged (Hong et al., Citation2018), a sensitivity analysis is represented in . The first (MT) and third (AN) authors independently applied the MMAT to the included studies and then compared results via collaborative discussion. Robust interrater reliability was achieved (93.85%).

Table IV. Assessment of methodological quality for included studies via the MMAT criteria.

2.7. Evidence Synthesis

Due to the vast disparity in design, target outcomes, and measures used amongst the included studies, meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate and unfeasible. The results were therefore conveyed via a convergent narrative synthesis.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The initial search across databases applying the key search terms resulted in 1483 publications (refer to ). Prior to screening, 432 duplicates and 2 records unable to be obtained in the English language were removed. A further 1021 were excluded at the title and abstract stage. Upon full-text review of the 28 remaining articles, 14 publications met the current criteria for inclusion.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Of the 14 included studies, two were conducted in the United States (Farrell et al., Citation2009; Reiss et al., Citation2014), two in Germany (Fassbinder et al., Citation2016; Nenadić et al., Citation2017), one in Finland (Hilden et al., Citation2021), and one in Australia (Skewes et al., Citation2015). One study was conducted internationally across multiple sites between Australia, Germany, Greece, Netherlands and the United Kingdom (Arntz et al., Citation2022). The remaining seven studies were conducted in the Netherlands. Four of the included studies were randomized control trials (RCT), two were uncontrolled pilot studies, one utilized mixed-methods, and the remaining eight were naturalistic in design. The combined population comprised of 1271 clinical participants with at least one PD as identified by a recognized diagnostic system. The mean age across studies ranged from 23.9 to 65 years (M = 35.59, SD = 9.67). Female participants comprised 79.76% of the total population. Notably, Van Vreeswijk et al. (Citation2020) did not report age statistics and Skewes et al. (Citation2015) omitted gender statistics. Seven of the studies excluded individuals with low intelligence or cognitive impairment, 11 excluded participants with psychotic symptoms, eight excluded individuals with comorbid substance use difficulties, and six studies excluded those with two or more Antisocial or Narcissistic PD traits. Six studies focused solely on BPD, two studies on Cluster C PDs, and four on both Cluster B and C PDs. Two studies utilized “mixed” PD samples, although upon further inspection these predominantly comprised of Avoidant, Obsessive-Compulsive, and Borderline PDs. Attrition ranged from 0% to 35.70% (M = 16.31, SD = 12.01) across treatment conditions in all studies, and from 14% to 33.33% (M = 24.58, SD = 7.97) across the compiled TAU conditions included in four of the 14 studies.

Treatment length ranged from six weeks to 24 months. A follow up assessment post-treatment was included in 10 of the 14 studies, which ranged from one to 24 months in duration (M = 6.60, SD = 6.87). Nine studies followed Farrell and Shaw’s (Citation2012) and Farrell et al.’s (Citation2009) high fidelity GST treatment manual, four used Broerson and Van Vreeswijk’s (Citation2012) shorter, more cognitively-focused protocol with less of an experiential emphasis, and one used Aalders and Van Dijk’s (Citation2012) semi-open, more psychodynamically-oriented approach. Two studies exclusively applied GST (Doomen, Citation2018; Koppers et al., Citation2021), while six studies integrated GST with individual ST, and three studies integrated GST with another modality such as Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (Koppers et al., Citation2020; Nenadić et al., Citation2017), or exposure and response prevention (ERP) and drama techniques (Peeters et al., Citation2021). The proportion of true GST across these nine studies ranged from 53% to 85% (M = 64.50, SD = 11.76). Three other studies applied additional treatment alongside GST such as supportive counseling (Hilden et al., Citation2021), psychomotor therapy (PMT; Van Dijk et al., Citation2022), and mindfulness-based therapy (i.e. Schema Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy [SMCBT]; Van Vreeswijk et al., Citation2020). However, the true amount of GST could not be determined from the information reported. Due to the heterogeneity of GST protocols used, the following patterns are only identified if also present in studies utilizing Farrell and Shaw’s (Citation2012) protocol, which has the highest level of fidelity to the model and associated interventions originally described by Young et al. (Citation2003).

3.3. Methodological Quality

Inspection of the MMAT sensitivity analysis indicated that four of the 14 included studies could be deemed low risk on all relevant items. Notably, some risk of bias was observed. Doomen (Citation2018) and Peeters et al. (Citation2021) failed to reasonably account for confounding variables in their design and analyses, while Skewes and colleagues’ (Citation2015) qualitative component lacked methodological rigor more broadly. It was unclear whether Hilden et al.’s (Citation2021) conditions were comparable at baseline, as was whether their assessors were blinded to the intervention provided, which was also the case with Van Vreeswijk et al. (Citation2020). Farrell and colleagues (Citation2009) did however acknowledge their assessors were unblinded. Whether Koppers et al. (Citation2020, Citation2021) had participants representative of their target population lacked clarity, and Dickhaut and Arntz’s (Citation2014) intervention may have changed without anticipation as clinicians received additional training. Lastly, four studies (Van Vreeswijk et al., Citation2020; Dickhaut & Arntz, Citation2014; Peeters et al., Citation2021; Van Dijk et al., Citation2022) reported either incomplete outcome data or dropout rates over 30%. Empirically, acceptable data values and dropout rates tend to range from 80% to 95%, and 5% to 20%, respectively (Higgins et al., Citation2019; Van Tulder et al., Citation2003; Viswanathan & Berkman, Citation2012). Notably, it was difficult to determine this criterion in four studies as they did not report missing data values. Overall, the current body of evidence is not without methodological flaws, leaving it susceptible to a moderate risk of bias. Therefore, the conclusions drawn must be interpreted with caution.

3.4. Group Schema Therapy Outcomes

The outcomes investigated across the resulting body of evidence were clustered into four overarching categories: (a) PD symptom severity and rate of remission, (b) global and specific symptom severity, (c) quality of life and associated functioning, and (d) process outcomes pertaining to the intervention provided. While within and between group effects are differentiated where possible, some studies have one or both effects. For a direct visual comparison of pre/post effects, refer to .

3.4.1. PD symptom severity and remission.

Seven of the 14 studies investigated outcomes pertaining to PD symptoms. Two RCTs demonstrated reductions in BPD symptomology with large to extremely large effects when compared to TAU that were maintained at six- (Farrell et al., Citation2009) and 12-month (Arntz et al., Citation2022) follow up. Interestingly, Arntz et al. (Citation2022) found a combination of individual and GST was superior to a primarily group-based delivery. In both of their GST cohorts, Dickhaut and Arntz (Citation2014) demonstrated significant reductions in BPD symptoms at two-year follow-up with extremely large effect sizes. Their second cohort did, however, improve more and more quickly than the first cohort post-treatment, which was considered a consequence of more specialized training of therapists in the second cohort. Fassbinder et al.’s (Citation2016) pilot study aligns with these findings, demonstrating extremely large effects for GST’s ability to significantly reduce BPD symptomology, an effect that was sustained at two years post-treatment. BPD symptomology also reduced significantly in all three of Reiss et al.’s (Citation2014) pilot studies. The first two pilots exhibited extremely large effect sizes, while the third was medium in size, which was attributed to discrepancies in treatment length, number of group facilitators, and their level of expertise. Conversely, Hilden et al.’s (Citation2021) RCT observed BPD symptoms to reduce significantly across conditions, with GST no more effective than TAU. In addition to these findings drawing on predominantly BPD samples, Skewes et al. (Citation2015) demonstrated significant reductions in Avoidant PD symptomology upon completion of GST and at six-month follow up, with extremely large effect sizes. Of note, while PD presence was assessed in a diagnostic sense across all studies, six studies did not provide any assessment of PD symptom presence or severity across, at the cessation of, or post-treatment.

3.4.2. Global and specific symptom severity

Eleven of the included studies assessed global psychiatric symptom severity or more specific symptoms related to various areas of psychological distress or dysfunction. Three studies reported significant improvements in global psychological distress in their BPD samples post-GST with effect sizes ranging from medium to extremely large that were sustained at follow-up (Dickhaut & Arntz, Citation2014; Farrell et al., Citation2009; Reiss et al., Citation2014). Similar findings were reported in five other studies that utilized mixed PD samples, demonstrating sustainable medium to large effects post-GST (Koppers et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Nenadić et al., Citation2017; Skewes et al., Citation2015; Peeters et al., Citation2021). While one study with a mixed PD sample exhibited significant improvements in global psychological distress, the effects of GST were not significantly different from TAU (Van Vreeswijk et al., Citation2020). Notably, their GST program was amongst the shortest in duration, with treatment lasting two months.

Significant reductions in depressive and anxiety-related symptoms were observed in two studies with medium to extremely large effect sizes, which were maintained at follow-up (Skewes et al., Citation2015; Hilden et al., Citation2021). However, Hilden et al.’s (Citation2021) TAU could not be differentiated from their GST condition. Koppers et al.’s (Citation2020) post-hoc analyses found depressive symptoms to play a moderating role between PD symptoms and global distress, with high rates of comorbid depressive symptoms leading to greater reduction in global distress post-GST. Lastly, Fassbinder et al. (Citation2016) found days of hospitalization decreased significantly in their sample of individuals with BPD after their GST application, with extremely large effect sizes post-treatment and at two-year follow up.

3.4.3. Quality of life and associated functioning

Of the 14 included studies, seven independent publications reported outcomes associated with quality of life and functional capacity. Three studies found GST to significantly improve global functioning, social and occupational functioning, work and social adjustment, and self-reported happiness in BPD samples with large to extremely large effects post-treatment and at follow-up (Arntz et al., Citation2022; Fassbinder et al., Citation2016; Dickhaut & Arntz, Citation2014). Two studies found global functional capacity specifically to improve with GST for individuals with BPD, with extremely large effect sizes that were also sustainable at follow-up (Farrell et al., Citation2009; Reiss et al., Citation2014). van Dijk and colleagues found quality of life among older adults with Cluster B and/or C PDs to improved significantly with small effects immediately post-treatment that evolved into a medium effect at two-month follow up. Lastly, Hilden et al. (Citation2021) observed self-reported degree of disability and impairment in individuals with BPD to improve significantly across conditions, although was unable to identify any significant differences between GST + TAU and TAU alone.

3.4.4. Process outcomes

Eleven studies investigated more process-oriented outcomes related to the specific treatment administered. GST significantly improved EMSs and functional and dysfunctional modes in three studies with BPD samples (Arntz et al., Citation2022; Dickhaut & Arntz, Citation2014; Fassbinder et al., Citation2016), one when compared to TAU alone (Arntz et al., Citation2022), with large to extremely large effect sizes that were maintained at follow up. In mixed PD samples, five studies exhibited significant EMS and mode improvement with small to large effects that were maintained post-treatment (Nenadić et al., Citation2017), and at two- (Van Dijk et al., Citation2022), three- (Koppers et al., Citation2020, Citation2021) and six-months (Skewes et al., Citation2015) follow up. Interestingly, Koppers et al.’s (Citation2020) post-hoc analysis of differences between participants with high and low levels of depression revealed no differences in reliable EMS improvement.

The findings of studies integrating GST with other treatment modalities appear more mixed. For example, Doomen’s (Citation2018) naturalistic provision of GST integrating drama techniques for individuals with Cluster C PDs exhibited significant improvements in self-reported and observer-reported modes, with effect sizes ranging from small to large across their subscales. Integrating exposure and response prevention tasks into GST, Peeters et al.’s (Citation2021) pilot of individuals with Cluster C PDs and comorbid chronic anxiety demonstrated significant improvements in schemas and modes, with a medium-sized effect. Utilizing a mixed sample of Avoidant PD and BPD, Van Vreeswijk et al. (Citation2020) did observe schema improvement in their comparison between SMCBT and Competitive Memory Training (COMET), although this effect was extremely small and non-significant. Modes appeared to worsen at the end of treatment with small effect, and to exhibit improvements at follow-up with small effect. Participant awareness of Mindfulness practices appeared neither to improve nor deteriorate.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

The current mixed-methods systematic review provides the first amalgamation and evaluation of empirical evidence pertaining to GST outcomes in PD populations. While most studies evidenced strong support for GST’s ability to reduce Cluster B and Avoidant PD symptomology with sustainable effects at follow-up, one study (Hilden et al., Citation2021) could not differentiate GST from TAU, and many of those in strong support of GST omitted a control condition. Similarly, most studies found GST to improve global symptom severity, psychological distress, depression and anxiety, although two found comparable effects for TAU (Van Vreeswijk et al., Citation2020; Hilden et al., Citation2021). In terms of quality of life and functional capacity, all studies but one (Hilden et al., Citation2021) evidenced the robust efficacy of GST with stable effects at follow-up, which is consistent with ST’s long term focus on characterological change beyond symptomatic reduction. Last, GST in isolation was observed to result in significant EMS and mode improvements in individuals with Cluster B and/or C PDs, particularly for BPD and Avoidant PD. While the integration of ERP and drama therapy techniques produced similar effects, the assimilation of mindfulness was not significantly different to an active comparator condition, with its effects less clear.

4.2. Limitations of the Evidence Base

The current body of evidence presents several empirically robust studies with meaningful results that demonstrate the efficacy of GST for PDs. However, several limitations across and within the body of evidence form a hindrance to appraisals of GST’s overall efficacy for PD. Overall, there is a significant discrepancy in the GST program applied in terms of protocol used, length of treatment delivered, frequency and duration of sessions, and percentage of true ST. Namely, whilst Farrell and Shaw’s (Citation2012) approach is generally viewed as truly ST-based—due to its high fidelity to the original model and interventions outlined in Young et al. (Citation2003)—it is difficult to make the same claim for the Van Vreeswijk et al. (Citation2020) schema-based Cognitive-Behaviour Group Therapy protocol that omits experiential techniques. Similarly, Aalders and Van Dijk’s (Citation2012) protocol has a greater emphasis on a psychodynamic framework that, whilst not completely incompatible with ST (i.e. shared Object-Relations foundation; Bernstein, Citation2005), heavily relies on psychodynamic interventions rather than ST strategies to meet relational goals. These protocols therefore differ in their inclusion and delivery of experiential and/or relational techniques, leading to significant challenges comparing results, identifying mechanisms of change, and drawing meaningful conclusions from dropout rates and follow-up assessments. Methodologically, the majority of studies failed to include a control or comparator condition—and of those that did, a number combined GST with additional therapies like ERP, mindfulness and psychomotor therapy. While this reflects the highly integrative nature of ST, the percentage of true ST was often unclear and so the treatment outcomes obtained cannot be exclusively attributed to GST. In terms of the sample, there is an observable over-representation of BPD patients and an under representation of other PDs such narcissistic and antisocial PDs and Cluster A PDs more broadly. There is also an under-representation of individuals with low intelligence, substance use problems, and risk behaviors such as self-harm, which can be common comorbidities with PDs (e.g. Trull et al., Citation2010; Shah & Zanarini, Citation2018). Lastly, the evidence base’s current stage of development, which made quantitative analysis not possible, meant that sample sizes and subsequently the power of the included studies could not be taken into consideration.

4.3. Research Agenda

In order to strengthen and expand the promising findings regarding the efficacy of GST for PDs, we propose a number of important foci for future research. First, future research would benefit from an increase in methodological rigor, including randomization, control/comparison conditions, reasonable follow-up post-intervention, and reporting of dropout rates. Promisingly, there are several protocols and RCT designs that have been published that may solidify the current preliminary evidence for GST’s efficacy. Namely, published protocols indicate that RCTs are currently underway comparing the efficacy and cost effectiveness of GST and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (an alternative evidence-based group therapy; Linehan, Citation1993a) for BPD in outpatient settings (Fassbinder et al., Citation2018; Wibbelink et al., Citation2022). Extending to other PDs, proposals have aimed to compare GST and CBT for individuals with comorbid Avoidant PD and social anxiety (Baljé et al., Citation2016) and GST with individual ST for Cluster C PDs (Groot et al., Citation2022). The collective findings resulting from this next phase of research trials is highly anticipated, and has the potential to both fill the empirical gaps identified and have real-world implications for the accessibility and affordability of evidence-based PD treatment.

Second, future research should compare the effects of specific GST protocols given their differential emphases on techniques and length of treatment. For example, Broersen and van Vreeswijk (Citation2012) place a greater emphasis on cognitive techniques than Farrell and Shaw’s (Citation2012) original protocol, and also insist on a short-term delivery of 20 weeks, in contrast to the recommended one-year. Controlling for factors, such as treatment content and duration and session length and frequency, in future studies is paramount in identifying mechanisms of change and optimizing treatment for psychopathology that has historically been extremely costly and resource-intensive to treat. In addition, determining in which populations individual, group, or hybrid individual-group ST is most effective—and in what dose—may have wide-reaching implications for effectively including ST within a stepped-care model; a graded approach to treatment intensity depending on need, which has previously demonstrated efficacy in the effective and timely treatment of PDs (e.g. Choi-Kain et al., Citation2016; Paris, Citation2013).

Finally, future research should expand the overly strict exclusion criterion that has often been employed. While the difficulties working with and recruiting individuals with narcissistic and antisocial traits, Cluster A symptomology more broadly, and substance use and high-risk behaviors—both in a group and individual capacity—are well-documented (Bernstein et al., Citation2023; Bernstein et al., Citation2019), a broader understanding of how GST generalizes to these populations is essential given their burden on healthcare systems (e.g. Soeteman et al., Citation2008). This will further inform how the utility of GST may differ for presentations varying in severity and functioning, and subsequently, how the treatment may be effectively optimized.

4.4. Treatment Implications

Despite the aforementioned limitations and pressing need for further research, a number of important practical and clinical implications can be drawn from the current body of evidence:

GST appears to be efficacious for Cluster B and C PD symptomology, and their related EMSs and modes. GST may also lead to improvements in global symptom severity, anxiety and depression, quality of life, and functional capacity in these presentations.

It is possible that GST can be effectively integrated with other evidence-based psychotherapies such as ERP and drama therapy, although the efficacy of integrating other interventions, such as mindfulness, is not yet clear.

Caution is warranted in implementing GST for Cluster A PDs, individuals deemed to have low intelligence or cognitive impairment, those with dissociative or psychotic symptoms, or individuals with comorbid substance use difficulties, as there is currently little evidence for these populations.

4.5. Conclusions

The integration of cognitive, behavioral, experiential, and relational techniques allows ST to facilitate complete recovery from PD beyond symptomatic remission and a reduction in maladaptive behaviors (Van Asselt et al., Citation2008; Nordahl & Nysæter, Citation2005). However, ST is a long-term approach with a considerable associated cost when delivered individually (Bamelis et al., Citation2015). The current body of literature provides promising preliminary evidence in support of the efficacy of GST for BPD, and Cluster B and C PDs more broadly, in four areas: PD symptom severity, global and specific symptom severity, quality of life, broader functional capacity, and treatment-related process outcomes such as schemas and modes. Although the current body of evidence is not without limitations and a moderate risk of bias, it has allowed for the proposal of a future research agenda and the identification of implications for clinicians in-practice. Ultimately, the available evidence base supports GST as a promising economical alternative to individual ST, and a promising holistic alternative to other costly PD treatments that reduce or eliminate life-threatening and self-harming behaviors, but can leave patients feeling empty and dysphoric (Alexander, Citation2006a, Citation2006b).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aalders, H., & van Dijk, J. (2012). Schema therapy in a psychodynamic group. The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Schema Therapy: Theory, Research, and Practice, 383–390.

- Alexander, K. (2006a). Peer support for borderline personality disorder: Meeting the challenge through partnership and collaboration [Paper presentation]. Yale University School of Medicine & the National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder Conference, New Haven, CT.

- Alexander, K. (2006b). Bpd recovery and peer support [Paper presentation]. National Alliance on Mental Illness, Expert BPD Focus Group, Arlington, VA.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (Vol. 5). Washington, DC: American psychiatric association.

- Arntz, A., Jacob, G. A., Lee, C. W., Brand-de Wilde, O. M., Fassbinder, E., Harper, R. P., Lavender, A., Lockwood, G., Malogiannis, I. A., Ruths, F. A., Schweiger, U., Shaw, I. A., Zarbock, G., & Farrell, J. M. (2022). Effectiveness of predominantly group schema therapy and combined individual and group schema therapy for borderline personality disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(4), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0010

- Bachrach, N., & Arntz, A. (2021). Group schema therapy for patients with cluster-C personality disorders: A case study on avoidant personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 1233–1248. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23118

- Baljé, A., Greeven, A., van Giezen, A., Korrelboom, K., Arntz, A., & Spinhoven, P. (2016). Group schema therapy versus group cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder with comorbid avoidant personality disorder: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 17(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1605-9

- Bamelis, L. L., Arntz, A., Wetzelaer, P., Verdoorn, R., & Evers, S. M. (2015). Economic evaluation of schema therapy and clarification-oriented psychotherapy for personality disorders: A multicentre, randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(11), 5383. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14m09412

- Bamelis, L. L., Evers, S. M., Spinhoven, P., & Arntz, A. (2014). Results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness of schema therapy for personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(3), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12040518

- Barazandeh, H., Kissane, D. W., Saeedi, N., & Gordon, M. (2016). A systematic review of the relationship between early maladaptive schemas and borderline personality disorder/traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.021

- Beck, A. T., Davis, D. D., & Freeman, A.2004). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders. Guilford Publications.

- Beckwith, H., Moran, P. F., & Reilly, J. (2014). Personality disorder prevalence in psychiatric outpatients: A systematic literature review. Personality and Mental Health, 8(2), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1252

- Bernstein, D. P. (2005). Schema therapy for personality disorders. In S. Strack (Ed.), Handbook of personology and psychopathology (pp. 462–477). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Bernstein, D. P., Keulen-de Vos, M., Clercx, M., de Vogel, V., Kersten, G. C. M., Lancel, M., Jonkers, P. P., Bogaerts, S., Slaats, M., Broers, N. J., Deenen, T. A. M., & Arntz, A. (2023). Schema therapy for violent PD offenders: A randomized clinical trial. Psychological Medicine, 53(1), 88–102. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001161

- Bernstein, A., Zvolensky, M. J., Vujanovic, A. A., & Moos, R. (2009). Integrating anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and discomfort intolerance: A hierarchical model of affect sensitivity and tolerance. Behavior Therapy, 40(3), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.08.001

- Bernstein, D. P., Zvolensky, M. J., Vujanovic, A. A., & Moos, R. (2019). Integrating anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and discomfort intolerance: a hierarchical model of affect sensitivity and tolerance. Behavior therapy, 40(3), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.08.001.

- Bloo, J., Arntz, A., & Schouten, E. (2017). The borderline personality disorder checklist: Psychometric evaluation and factorial structure in clinical and nonclinical samples. Annals of Psychology, 20(2), 311–336. https://doi.org/10.18290/rpsych.2017.20.2-3en

- Bohus, M., Kleindienst, N., Limberger, M. F., Stieglitz, R. D., Domsalla, M., Chapman, A. L., … & Wolf, M. (2009). The short version of the Borderline Symptom List (BSL-23): development and initial data on psychometric properties. Psychopathology, 42(1), 32–39.

- Broersen, J., & van Vreeswijk, M. (2012). Schema therapy in groups: A short-term schema CBT protocol. In The Wiley- Blackwell handbook of schema therapy: Theory, research, and practice (p. 373–381). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Online ISBN: 9781119962830, Print ISBN: 9780470975619. https://research.vumc.nl/en/publications/79d9a9ee-45b2-4887-8ea2-151f2277ae56.

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

- Burlingame, G. M., Fuhriman, A. J., & Johnson, J. (2004). Process and outcome in group counseling and psychotherapy: A perspective. In J. L. DeLucia-Waack, D. A. Gerrity, C. R. Kalodner, & M. T. Riva (Eds.), Handbook of Group Counselling and Psychotherapy (pp. 49–61). Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452229683.n4

- Choi-Kain, L. W., Albert, E. B., & Gunderson, J. G. (2016). Evidence-based treatments for borderline personality disorder: Implementation, integration, and stepped care. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 24(5), 342–356.

- Coid, J., Yang, M. I. N., Tyrer, P., Roberts, A., & Ullrich, S. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188(5), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.188.5.423

- Conte, H. R., Plutchik, R., Karasu, T. B., & Jerrett, I. (1980). A self-report borderline scale: Discriminative validity and preliminary norms. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 168(7), 428–435. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198007000-00007

- Crowe, M., & Sheppard, L. (2011). A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: Alternative tool structure is proposed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.008

- Cruitt, P. J., & Oltmanns, T. F. (2019). Unemployment and the relationship between borderline personality pathology and health. Journal of Research in Personality, 82, 103863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103863

- Dadomo, H., Grecucci, A., Giardini, I., Ugolini, E., Carmelita, A., & Panzeri, M. (2016). Schema therapy for emotional dysregulation: Theoretical implication and clinical applications. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1987. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01987

- Dadomo, H., Panzeri, M., Caponcello, D., Carmelita, A., & Grecucci, A. (2018). Schema therapy for emotional dysregulation in personality disorders: A review. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 31(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000380

- Davidson, K. M., Tyrer, P., Norrie, J., Palmer, S. J., & Tyrer, H. (2010). Cognitive therapy V. usual treatment for borderline personality disorder: Prospective 6-year follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(6), 456. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074286

- Derogatis, L. R., & Savitz, K. L. (2000). The SCL-90-R, brief symptom inventory, and matching clinical rating scales. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (pp. 679–724). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Dickhaut, V., & Arntz, A. (2014). Combined group and individual schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45(2), 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.11.004

- Doomen, L. (2018). The effectiveness of schema focused drama therapy for cluster C personality disorders: An exploratory study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 61, 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.12.002

- Eaton, N. R., & Greene, A. L. (2018). Personality disorders: Community prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Current Opinion in Psychology, 21, 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.09.001

- Farrell, J. M., Reiss, N., & Shaw, I. A. (2014). The schema therapy clinician's guide: A complete resource for building and delivering individual, group and integrated schema mode treatment programs. John Wiley & Sons.

- Farrell, J. M., & Shaw, I. A. (2012). Group schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: A step-by-step treatment manual with patient workbook. Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119943167

- Farrell, J. M., Shaw, I. A., & Webber, M. A. (2009). A schema-focused approach to group psychotherapy for outpatients with borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40(2), 317–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.01.002

- Fassbinder, E., Assmann, N., Schaich, A., Heinecke, K., Wagner, T., Sipos, V., & Schweiger, U. (2018). Pro* BPD: Effectiveness of outpatient treatment programs for borderline personality disorder: A comparison of schema therapy and dialectical behavior therapy: Study protocol for a randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1905-6

- Fassbinder, E., Schweiger, U., Martius, D., Brand-de Wilde, O., & Arntz, A. (2016). Emotion regulation in schema therapy and dialectical behavior therapy. Frontiers In Psychology, 7, 1373. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01373

- Fazel, S., & Danesh, J. (2002). Serious mental disorder in 23 000 prisoners: A systematic review of 62 surveys. The Lancet, 359(9306), 545–550. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07740-1

- First, M. B., & Gibbon, M. (2004). The structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders (SCID-I) and the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II disorders (SCID-II). In M. J. Hilsenroth & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment, Vol. 2. Personality assessment (pp. 134–143). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Fok, M. L. Y., Hayes, R. D., Chang, C. K., Stewart, R., Callard, F. J., & Moran, P. (2012). Life expectancy at birth and all-cause mortality among people with personality disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 73(2), 104–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.05.001

- Franke, G. H. (2016). SCL-90®-S. Symptom-Checklist-90®-Standard - German Manual. In Diagnostische Verfahren in der Psychotherapie (Vol. 1, p. 426). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- Frankenburg, F. R., & Zanarini, M. C. (2004). The association between borderline personality disorder and chronic medical illnesses, poor health-related lifestyle choices, and costly forms of health care utilization. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(12), 1485. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v65n1211

- Giesen-Bloo, J., van Dyck, R., Spinhoven, P., van Tilburg, W., Dirksen, C., van Asselt, T., Kremers, I., Nadort, M., & Arntz, A. (2006). Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Randomized trial of schema-focused therapy Vs transference-focused psychotherapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(6), 649–658. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.649

- Giesen-Bloo, J. H., Wachters, L. M., Schouten, E., & Arntz, A. (2010). The borderline personality disorder severity index-Iv: Psychometric evaluation and dimensional structure. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(2), 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.023

- Groot, I. Z., Venhuizen, A. S. S., Bachrach, N., Walhout, S., de Moor, B., Nikkels, K., Dalmeijer, S., Maarschalkerweerd, M., van Aalderen, J. R., de Lange, H., Wichers, R., Hollander, A. P., Evers, S. M. A. A., Grasman, R. P. P. P., & Arntz, A. (2022). Design of an RCT on cost-effectiveness of group schema therapy versus individual schema therapy for patients with Cluster-C personality disorder: the QUEST-CLC study protocol. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 637. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04248-9

- Group, T. E. (1990). EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health policy, 16(3), 199–208.

- Gülüm, İ. V. (2018). Dropout in schema therapy for personality disorders. Research in psychotherapy (Milano), 21(2), 314. https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2018.314

- Hall, R. C. (1995). Global assessment of functioning: A modified scale. Psychosomatics, 36(3), 267–275. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71666-8

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 5.1.0). http://handbook.cochrane.org/.

- Higgins, J. P., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., & Sterne, J. A. (2019). Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 205–228.

- Hilden, H. M., Rosenström, T., Karila, I., Elokorpi, A., Torpo, M., Arajärvi, R., & Isometsä, E. (2021). Effectiveness of brief schema group therapy for borderline personality disorder symptoms: A randomized pilot study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 75(3), 176–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2020.1826050

- Hilsenroth, M. J., Ackerman, S. J., Blagys, M. D., Baumann, B. D., Baity, M. R., Smith, S. R., & Holdwick Jr, D. J. (2000). Reliability and validity of DSM-IV axis V. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(11), 1858–1863. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1858

- Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), Version 2018. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf.

- Iliakis, E. A., Sonley, A. K., Ilagan, G. S., & Choi-Kain, L. W. (2019). Treatment of borderline personality disorder: Is supply adequate to meet public health needs? Psychiatric Services, 70(9), 772–781. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900073

- Jacob, G. A., & Arntz, A. (2013). Schema therapy for personality disorders—A review. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 6(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2013.6.2.171

- Koppers, D., Van, H., Peen, J., Alberts, J., & Dekker, J. (2020). The influence of depressive symptoms on the effectiveness of a short-term group form of schema cognitive behavioural therapy for personality disorders: A naturalistic study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02676-z

- Koppers, D., Van, H., Peen, J., & Dekker, J. J. (2021). Psychological symptoms, early maladaptive schemas and schema modes: Predictors of the outcome of group schema therapy in patients with personality disorders. Psychotherapy Research, 31(7), 831–842. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1852482

- Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–515. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06

- Lambert, M. J., Burlingame, G. M., Umphress, V., Hansen, N. B., Vermeersch, D. A., Clouse, G. C., & Yanchar, S. C. (1996). The reliability and validity of the outcome questionnaire. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 3(4), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199612)3:4<249::AID-CPP106>3.0.CO;2-S

- Leppänen, V., Kärki, A., Saariaho, T., Lindeman, S., & Hakko, H. (2015). Changes in schemas of patients with severe borderline personality disorder: The Oulu BPD study. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12172

- Leppänen, V., Vuorenmaa, E., Lindeman, S., Tuulari, J., & Hakko, H. (2016). Association of parasuicidal behaviour to early maladaptive schemas and schema modes in patients with BPD: The Oulu BPD study. Personality and Mental Health, 10(1), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.1304

- Linehan, M. M. (1993a). Dialectical behavior therapy for treatment of borderline personality disorder: Implications for the treatment of substance abuse. NIDA Research Monograph, 137, 201–216.

- Lowenstein, J. A., Stickney, J., & Shaw, I. (2020). Implementation of a schema therapy awareness group for adult male low secure patients with comorbid personality difficulties: Reflections and challenges. The Journal of Forensic Practice, 22(2), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-10-2019-0045

- Luciano, J. V., Bertsch, J., Salvador-Carulla, L., Tomás, J. M., Fernández, A., Pinto-Meza, A., & Serrano-Blanco, A. (2010). Factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity of the Sheehan disability scale in a Spanish primary care sample. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16(5), 895–901. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01211.x

- Masley, S. A., Gillanders, D. T., Simpson, S. G., & Taylor, M. A. (2012). A systematic review of the evidence base for schema therapy. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 41(3), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2011.614274

- Millon, T. (1997). Millon clinical multiaxial inventory-III (Manual 2nd ed.). Pearson Assessments.

- Moran, P., Jenkins, R., Tylee, A., Blizard, R., & Mann, A. (2000). The prevalence of personality disorder among UK primary care attenders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102(1), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102001052.x

- Mundt, J. C., Marks, I. M., Shear, M. K., & Greist, J. M. (2002). The work and social adjustment scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5), 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.180.5.461

- Nadort, M., Arntz, A., Smit, J. H., Giesen-Bloo, J., Eikelenboom, M., Spinhoven, P., & van Dyck, R. (2009). Implementation of outpatient schema therapy for borderline personality disorder with versus without crisis support by the therapist outside office hours: A randomized trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(11), 961–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.013

- Nenadić, I., Lamberth, S., & Reiss, N. (2017). Group schema therapy for personality disorders: A pilot study for implementation in acute psychiatric In-patient settings. Psychiatry Research, 253, 9–12. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.093

- Nordahl, H. M., & Nysæter, T. E. (2005). Schema therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder: A single case series. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 36(3), 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.05.007

- Norman, S. B., Hami Cissell, S., Means-Christensen, A. J., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). Depression and Anxiety, 23(4), 245–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20182

- Oliveira, J. L. C. D., Magalhães, A. M. M. D., Matsuda, L. M., Santos, J. L. G. D., Souto, R. Q., Riboldi, C. D. O., & Ross, R. (2021). Mixed methods appraisal tool: Strengthening the methodological rigor of mixed methods research studies in nursing. Texto & Contexto-Enfermagem, 30, e20200603.

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01552-x

- Paris, J. (2013). Stepped care: an alternative to routine extended treatment for patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Services, 64(10), 1035–1037. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201200451

- Peeters, N., van Passel, B., & Krans, J. (2021). The effectiveness of schema therapy for patients with anxiety disorders, OCD, or PTSD: A systematic review and research agenda. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(3), 579–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12324

- Peters, M. D. (2017). Managing and coding references for systematic reviews and scoping reviews in EndNote. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 36(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2017.1259891

- Peters, M. D., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

- Priebe, S., Huxley, P., Knight, S., & Evans, S. (1999). Application and results of the Manchester short assessment of quality of life (MANSA). International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 45(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/002076409904500102

- Reinert, D. F., & Allen, J. P. (2002). The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): A review of recent research. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 26(2), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02534.x

- Reiss, N., Lieb, K., Arntz, A., Shaw, I. A., & Farrell, J. (2014). Responding to the treatment challenge of patients with severe BPD: Results of three pilot studies of inpatient schema therapy. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 42(3), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465813000027

- Renner, F., Arntz, A., Leeuw, I., & Huibers, M. (2013). Treatment for chronic depression using schema therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20(2), 166. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12032

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Measures Package, 61(52), 18.

- Schaap, G. M., Chakhssi, F., & Westerhof, G. J. (2016). Inpatient schema therapy for nonresponsive patients with personality pathology: Changes in symptomatic distress, schemas, schema modes, coping styles, experienced parenting styles, and mental well-being. Psychotherapy, 53(4), 402. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000056

- Schreurs, P. J. G., van de Willige, G., Tellegen, B., & Brosschot, J. F. (1993). Herziene handleiding Utrechtse Coping Lijst (UCL). Swets & Zeitlinger B.V.

- Shah, R., & Zanarini, M. C. (2018). Comorbidity of borderline personality disorder: Current status and future directions. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 41(4), 583–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2018.07.009

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(20), 22–33.

- Skewes, S. A., Samson, R. A., Simpson, S. G., & van Vreeswijk, M. (2015). Short-term group schema therapy for mixed personality disorders: A pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1592. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01592

- Soeteman, D. I., Hakkaart-van Roijen, L., Verheul, R., & Busschbach, J. J. V. (2008). The economic burden of personality disorders in mental health care. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(2), 259–265. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v69n0212

- Souto, R. Q., Khanassov, V., Hong, Q. N., Bush, P. L., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2015). Systematic mixed studies reviews: Updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the mixed methods appraisal tool. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(1), 500–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.08.010

- Tan, Y. M., Lee, C. W., Averbeck, L. E., Brand-de Wilde, O., Farrell, J., Fassbinder, E., & Arntz, A. (2018). Schema therapy for borderline personality disorder: A qualitative study of patients’ perceptions. PLoS One, 13(11), e0206039.

- Taylor, C. D., Bee, P., & Haddock, G. (2017). Does schema therapy change schemas and symptoms? A systematic review across mental health disorders. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90(3), 456–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12112

- Torgersen, S., Kringlen, E., & Cramer, V. (2001). The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58(6), 590–596. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590

- Trull, T. J., Jahng, S., Tomko, R. L., Wood, P. K., & Sher, K. J. (2010). Revised NESARC personality disorder diagnoses: Gender, prevalence, and comorbidity with substance dependence disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 24(4), 412–426. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2010.24.4.412

- Tschacher, W., Zorn, P., & Ramseyer, F. (2012). Change mechanisms of schema-centered group psychotherapy with personality disorder patients. PLoS One, 7(6), e39687. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039687

- Van Asselt, A. D., Dirksen, C. D., Arntz, A., Giesen-Bloo, J. H., van Dyck, R., Spinhoven, P., van Tilburg, W., Kremers, I. P., Nadort, M., & Severens, J. L. (2008). Outpatient psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cost-effectiveness of schema-focused therapy Vs. transference-focused psychotherapy. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(6), 450–457. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.033597

- Van den Broek, E., Keulen-de Vos, M., & Bernstein, D. P. (2011). Arts therapies and schema focused therapy: A pilot study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38(5), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2011.09.005

- Van Dijk, S. D. M., Bouman, R., Folmer, E. H., den Held, R. C., Warringa, J. E., Marijnissen, R. M., & Voshaar, R. C. O. (2020). (Vi)-rushed into online group schema therapy based day-treatment for older adults by the COVID-19 outbreak in The Netherlands. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(9), 983–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.028

- Van Dijk, S. D. M., Bouman, R., Folmer, E. H., van Alphen, S. P. J., van den Brink, R. H. S., & Oude Voshaar, R. C. (2022). A feasibility study of group schema therapy with psychomotor therapy for older adults with a cluster B or C personality disorder. Clinical Gerontologist, 1–7. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2022.2099330

- Van Dijk, S. D. M., Veenstra, M. S., Bouman, R., Peekel, J., Veenstra, D. H., Van Dalen, P. J., & Oude Voshaar, R. C. (2019). Group schema-focused therapy enriched with psychomotor therapy versus treatment as usual for older adults with cluster B and/or C personality disorders: A randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1996-0

- Van Tulder, M., Furlan, A., Bombardier, C., Bouter, L., & Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. (2003). Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine, 28(12), 1290–1299.

- van Vreeswijk, M., & Broersen, J. (2013). Schematherapie in groepen. Kortdurende schemagroepstherapie: Cognitief gedragstherapeutische technieken–Handleiding, 11–18.

- Van Vreeswijk, M. F., Spinhoven, P., Eurelings-Bontekoe, E. H. M., & Broersen, J. (2014). Changes in symptom severity, schemas and modes in heterogeneous psychiatric patient groups following short-term schema cognitive–behavioural group therapy: A naturalistic pre-treatment and post-treatment design in an outpatient clinic. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1813

- Van Vreeswijk, M. F., Spinhoven, P., Zedlitz, A. M. E., & Eurelings-Bontekoe, E. H. M. (2020). Mixed results of a pilot RCT of time-limited schema mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and competitive memory therapy plus treatment as usual For personality disorders. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 11(3), 170. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000361

- Viswanathan, M., & Berkman, N. D. (2012). Development of the RTI item bank on risk of bias and precision of observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 65(2), 163–178.

- Weissman, M. M. (1993). The epidemiology of personality disorders: A 1990 update. Journal of Personality Disorders, (Suppl 1), 44–62.

- World Health Organization. (1996, December). WHOQOL-BREF: introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment: Field trial version (No. WHOQOL-BREF). World Health Organization.

- Wibbelink, C. J., Arntz, A., Grasman, R. P., Sinnaeve, R., Boog, M., Bremer, O., & Kamphuis, J. H. (2022). Towards optimal treatment selection for borderline personality disorder patients (BOOTS): A study protocol for a multicenter randomized clinical trial comparing schema therapy and dialectical behavior therapy. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03670-9

- Yalom, I. (1995). The theory and practice of group psychotherapy (3rd ed). Basic Books.

- Younan, R., Farrell, J., & May, T. (2018). ‘Teaching me to parent myself’: The feasibility of an in-patient group schema therapy programme for complex trauma. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 46(4), 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465817000698

- Young, J. E. (1990). Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A schema-focused approach. Professional Resource Exchange, Inc.

- Young, J. E. (1999). Cognitive therapy for personality disorder: A schema focused approach. Professional Resource Exchange Inc.

- Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema therapy (p. 254). Guilford.

- Zanarini, M. C., Gunderson, J. G., & Frankenburg, F. R. (1990). Cognitive features of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147(1), 57–63. doi:10.1176/ajp.147.1.57