Abstract

Objective

The present paper focuses on therapist responsiveness during the initial therapy session with clients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), aiming to analyze therapist responsiveness at short intervals during the initial session and determine if it can predict therapeutic alliance from both therapist and client viewpoints.

Method

A sample of 47 clients participated in the study for 10 sessions of therapy. Therapeutic alliance from therapists’ and clients’ perspectives was rated after each session; external raters assessed therapist responsiveness during the initial session. Multiple linear regression models and linear mixed models with backward variable selection based on AIC were run to analyze whether specific therapist behaviors during session one predicted therapeutic alliance rated from therapists’ and clients’ perspectives.

Results

The results indicate that therapists normalizing and validating clients’ experiences during the first session are crucial for establishing therapeutic alliance for BPD clients; however, for therapists, the increase in variability of emotions verbalized by clients during the initial session negatively impacts therapeutic alliance.

Conclusion

The study contributes to further understand the impact of therapists’ behavior at the beginning of therapy with BPD clients. Therapist responsiveness is crucial for therapy outcome but is methodologically challenging; therefore, efforts in this direction should be pursued.

Clinical or methodological significance of this article: therapist responsiveness is a crucial ingredient for therapy outcome, thus necessitating an in-depth exploration. However, from a methodological point of view, it is extremely complex to explore; it is imperative to address this domain in order to propose new and elaborate solutions for the study of responsiveness, ultimately advancing our clinical knowledge. The current paper can be regarded as a step toward this goal.

The concept of therapist responsiveness may prove highly valuable for psychotherapy researchers interested in examining how therapists adapt to the clients’ needs and tailor treatment accordingly. Such responsiveness is assumed to promote early engagement in therapy and facilitate the therapeutic alliance (Stiles et al., Citation1998; Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017). While responsiveness in general is inherent to all social interactions, its role becomes notably important in the context of psychotherapy, and this is from the first moment on. A therapist who is responsive to the client is able to tailor their own interaction style and behaviors to the individual client, for the benefit of the client. In psychotherapy, this beneficial aspect can more accurately be referred to as appropriate responsiveness, where therapists attempt to be reasonably responsive in order to obtain a desired outcome (Stiles, Citation2009, Citation2013; Stiles et al., Citation1998). Appropriate responsiveness allows the therapist to closely collaborate with the client, as well as establish a foundation for the therapeutic alliance. While appropriate therapist responsiveness is a crucial ingredient of clinical practice, it poses a significant challenge for psychotherapy research as it introduces important complexities in interpreting the results (Stiles, Citation2013). Different solutions were proposed over the past years to include therapist responsiveness as a variable in psychotherapy research (Kramer & Stiles, Citation2015). Among them, a quantitative measure was developed: Elkin et al. (Citation2014) put forward the Therapist Responsiveness Scale, an observer-rated measure which will be used in the present study. In the current study, therapist responsiveness will be defined accordingly:

The degree to which the therapist is attentive to the patient; is acknowledging and attempting to understand the patient’s current concerns; is clearly interested in and responding to the patient’s communication, both in terms of content and feelings; and is caring, affirming, and respectful towards the patient. (Elkin et al., Citation2014, p. 53)

A client population for which the minute-by-minute fluctuation of in-session behavior is critical for the development of a strong therapeutic alliance is clients with borderline personality disorder (BPD). The latter presents with patterns of unstable interpersonal relationships and functioning, as well as identity disturbance and marked patterns of impulsiveness and self-harm behaviors. The symptomatic presentation of BPD poses a unique challenge for the formation of the alliance: the interpersonal difficulties associated with BPD will inevitably manifest in the therapeutic relationship (Hirsh et al., Citation2012; Kramer, Citation2021; Levy et al., Citation2010; McMain et al., Citation2015). Therapeutic alliance has consistently been shown to be a significant predictor of therapy outcomes, underscoring its critical importance for psychotherapy (Flückiger et al., Citation2018). A possible consequence of the difficulties in establishing a good therapeutic alliance is the high dropout rate reported for clients with BPD, especially during the first quarter of treatment (Arntz et al., Citation2023; Iliakis et al., Citation2021). Therapeutic alliance has been found to relate to the frequency of treatment dropout (Yeomans et al., Citation1994), suggesting that within-session factors make an important contribution to the efficacy of psychotherapeutic treatment for BPD, especially in the beginning stages of therapy (Hilsenroth & Cromer, Citation2007). In fact, the formation of alliance in early sessions seems key for therapy engagement and outcome (Horvath et al., Citation2011). Studies have shown that therapist influence is vital to establish a healthy therapeutic alliance (Yeomans et al., Citation1994), and, as highlighted by Elliott et al. (Citation2018), to do so therapists need to be able to adapt and adjust to the unique client. Therapist interventions in the first session are particularly relevant for predicting the quality of further process in psychotherapy (Anderson et al., Citation2012), including relationship interventions, interventions fostering the therapeutic alliance, therapist warmth and body language, in a variety of contexts and populations (Del Rio Olvera et al., Citation2022; Lavik et al., Citation2018; Macewan, Citation2008; Spencer et al., Citation2019; Van Benthem et al., Citation2020).

Focusing on therapist responsiveness facing clients with BPD, Culina et al. (Citation2023) employed the Therapist Responsiveness Scale to the first session of a brief psychotherapy lasting in total of 10 sessions: the results indicated that the global evaluation of appropriate therapist responsiveness in the first session of therapy positively predicted the temporal evolution of therapeutic alliance rated by therapists. No analysis was proposed in this study on the level of the specific therapist behavior, its fluctuation, and complex interaction with client in-session features in the very first session. Indeed, the global nature of the item used in the study by Culina et al. (Citation2023) does not provide information on specific behaviors that make up therapist responsiveness and does not capture the important fluctuations that often characterize BPD, which can result in frequent changes in therapist responsiveness. Therefore, if we are seeking a detailed examination of in-session responsiveness, a moment-to-moment investigation of therapist behavior variations over very short time intervals provides a nuanced understanding of therapists’ adjustments and their impact on the therapeutic alliance formation, especially in interaction with in-session client’s behavior.

This approach is especially important given the significant influence of therapists’ in-session contributions, including their personal characteristics and the use of therapeutic techniques, on the development of a positive therapeutic relationship (e.g., Ackerman & Hilsenroth, Citation2003; Del Re et al., Citation2021; Kadur et al., Citation2020). Additionally, as mentioned earlier, first sessions are particularly relevant for early engagement and alliance formation. Stiles and Horvath (Citation2017) specifically describe how appropriate therapist responsiveness plays a crucial role in fostering a positive therapeutic alliance during psychotherapy sessions, which in turn predicts successful therapy outcomes. Therefore, we might assume that the fluctuation of therapist in-session behavior, very early in treatment for BPD, is relevant for predicting the therapeutic alliance over the course of treatment. More specifically, it would help distinguish which specific therapist behavior contribute to the evaluation of appropriate therapist responsiveness and help form the therapeutic alliance over time, from specific therapist behavior which may contribute negatively to average levels of alliance and its progression over time. Consequently, in the present study, with the goal of expanding on previous results from Culina et al. (Citation2023), we focus on the initial impact of therapist behaviors on the formation of the therapeutic alliance from sessions 1 to 10, in order to observe how the initial moment-to-moment in-session therapist responsiveness influences the development and trajectory, as well as the mean level, of the alliance over time. Indeed, both the mean and the temporal evolution of the therapeutic alliance are relevant for the understanding of the early therapy process for clients with BPD (Dimaggio et al., Citation2019; Eubanks et al., Citation2018; Hirsh et al., Citation2012; Kramer, Flückiger et al., Citation2014). This approach provides valuable insights into the early establishment and evolution of therapeutic relationship, bearing interest for understanding the dynamics and progression of therapy.

Accordingly, the aim of the current study is to conduct exploratory analyses to assess whether initial therapist responsiveness rated on short time intervals predicts therapeutic alliance over 10 sessions from both therapist’s and client’s perspectives. Specifically, we investigate if the mean and variability of each therapist responsiveness item, as well as one specific item assessing client’s expressed feelings, rated on 5-minute intervals at session 1, predict the mean as well as the temporal evolution over 10 sessions of the therapeutic alliance as rated by (a) therapists and (b) clients.

Methods

Participants

The present study draws on archival data from a previous project focusing on therapist responsiveness (for more methodological information, see: Culina et al., Citation2023; Kramer, Kolly et al., Citation2014). Participants were outpatients at a French-speaking University Clinic; potential participants received information on the study at the beginning of their treatment. The same sample as in the study by Culina et al. (Citation2023) was used here: a total of N = 47 clients forms the sample of the current study, more specifically 30 clients were female (63.8%) and the age of the participants ranged from 20 to 55 years (M = 33, SD = 9.28). Participants met the criteria for BPD diagnosis according to the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2000). Additionally, comorbid disorders were assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Lecrubier et al., Citation1997) and the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II Disorders (SCID-II; First et al., Citation1997). Thirteen therapists took part in the study and were supervised during the entire study duration, supervisors were trained in psychodynamic psychotherapy and, in addition, had followed specific training for treating BPD. Therapists included in the study were psychiatrists, psychologists or, in two cases, nurses. At inclusion time, nine therapists had completed a clinical residency ranging from 2 to 3 years, whereas four therapists possessed 4 years or more of clinical experience.

Raters

Ratings of therapist responsiveness were conducted by four Master’s level students. The preparation for the rating phase consisted of several meetings under the supervision of the project manager during which students were trained on the correct use of the scale. Additionally, the developer of the scale was available for consultation when necessary. In order to ascertain that inter-rater reliability was satisfactory, intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated (ICC) on 27 sessions (57.45% of the total) which were evaluated by two raters. The remaining 20 sessions were coded by one rater only. The sessions were distributed evenly among the four raters, ensuring that each rater contributed in a balanced way to the overall assessment. Inter-rater reliability ranged from good to excellent, the ICC (1,1) score being of 0.81(0.74–0.86).

Treatment

As per study design, participants were randomly assigned to either of the two following conditions: General Psychiatric Management (GPM; Gunderson & Links, Citation2014) or GPM with the implementation of Motive Oriented Therapeutic Relationship (MOTR; Caspar, Citation2007), this second condition had the aim of providing a more individualized treatment by taking into account individual plans and motives. Randomization took place following the initial session, ensuring equivalency between both groups during the first session.

GPM is an evidence-based generalist treatment for BPD which is highly adaptable to different treatment settings and is suitable to be implemented by all mental health professionals (Gunderson et al., Citation2018). GPM conceptualizes the disorder as primarily rooted in interpersonal hypersensitivity and, as such, places a particular focus on interpersonal stressors and psychoeducation (Gunderson et al., Citation2018). The primary objective of the initial session is to generate interest and active involvement in the treatment; in addition, in the context of the present study, a 10-session treatment is also proposed to the client by the end of the first session (Kramer et al., Citation2022).

Measures

The Therapist Responsiveness Scale (Elkin et al., Citation2014)

The Therapist Responsiveness Scale is an observer-rated measure developed with the goal of assessing therapist responsiveness during therapy sessions. The scale is divided in three parts and all items of the measure are rated on a scale ranging from 0 to 4. Part I consists of 11 items rated every 5 min: eight items evaluate positive therapist' behaviors and three items evaluate negative therapist’ behaviors; there is an additional item (item 12) that evaluates if the client verbally expresses feelings. Part II and part III of the scale focus on the entire session globally. Part II includes nine items that evaluate the general therapeutic atmosphere as well as specific client’s behaviors that might be used as a control variable. Part III includes five items aimed at obtaining a general rater’s impression of the therapist and the client. In the current study, only items of part I of the scale are analyzed (see for the list of items found in Part I of the scale). For simplicity, throughout the entire article, when referring to responsiveness items, we describe items of part I of the scale, which include one item (item 12) focusing specifically on client’s behavior and not therapist responsiveness. The inclusion of item 12 has the main goal of assessing its interaction with therapist behavior, and also to control for its impact on the working alliance. Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample, for the whole scale, was α = .975; Cronbach’s alpha for part I of the scale (including only the items that were used in the current study), was α = .976.

Table I. Part I of the Therapist Responsiveness Scale (Elkin et al., Citation2014).

The Working Alliance Inventory—Short Form (WAI-Short Form, Horvath & Greenberg, Citation1989)

The short form of the Working Alliance Inventory is a 12-item self-reported questionnaire that evaluates the therapeutic alliance. All items are rated on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). The questionnaire evaluates the following domains of the therapeutic alliance: (a) agreement between therapist and client on the tasks of therapy, (b) their agreement on the goals of therapy, and (c) the affective bond between therapist and client. Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was α = .913 (therapist’s perspective) and α = .921 (client’s perspective).

Procedure

The study received approval by the local ethics board (clearance number 254/08). The total length of therapy included in the study was of 10 sessions; if necessary, a longer therapy was offered but was not included in the study (for more information on the original study, see Kramer, Kolly et al., Citation2014). All therapy sessions were videotaped or, less frequently, audio recorded. At the end of each therapy session, both the therapist and the client filled out the short form of the working alliance inventory.

Raters individually assessed initial sessions using the Therapist Responsiveness Scale (Elkin et al., Citation2014) watching the video-taped (or audio recorded) therapy sessions.

Statistical Analyses

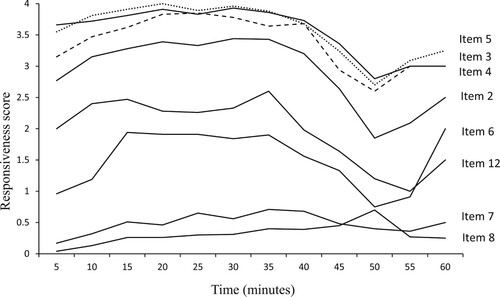

As a first step, we calculated within person mean and within person standard deviation for each responsiveness item, as well as item 12 assessing client’s behavior, and we then performed correlation analyses to establish whether the responsiveness items were too highly correlated. Correlation analyses between the means and standard deviations of all responsiveness items showed that item 2 (therapist uses minimum encouragers), item 3 (therapist focuses on/demonstrates interest), item 4 (therapist makes effort to understand from patient’s perspective), and item 5 (on topic) are strongly correlated with respect to their mean and standard deviation. In order to avoid multicollinearity problems, we grouped these items by calculating their average. Furthermore, item 6 (therapist responds to patient’s verbally expressed feelings) and item 12 (patient verbally expresses feelings) are dependent. If the score of item 6 is 0 and the client did not express any feelings, than therapist’s behavior is appropriately responsive, on the contrary, if the score of item 6 is 0 and the client expressed feelings, than the therapist’s behavior would not be considered appropriately responsive. For this reason, we included the interaction of these two items in the model selection procedure (item 6 x item 12), thus operationalizing appropriate therapist responsiveness given the context of the client. Therefore, the full model before variable selection contains the main effect of item 6, the main effect of item 12, and the multiplication of item 6 and item 12 that takes the values greater than zero only if both items are different from 0. Additionally, because of the high number of missing data, item 1 (Therapist makes eye contact) was excluded from the analyses; the high missing data is caused by the therapy sessions that were audio recorded. Items evaluating negative therapist behaviors (item 9: therapist disrupts the flow of sessions, item 10: therapist lectures the patient, item 11: therapist makes critical/judgmental, countering, minimizing, invalidating statements) were also excluded from analyses because of their almost complete absence and because of the lack of variability. The fluctuations of the raw scores of each item of therapist responsiveness during the first therapy session are shown in .

Figure 1. Fluctuation of items of responsiveness during session 1. Note: Item 1 as well as the items measuring negative therapist behavior (item 9, item 10, item 11) were not included in the analyses, for this reason, their fluctuation is not depicted in .

As a second step, four models were run separately to determine predictors of the mean over 10 sessions of therapeutic alliance. We tested whether: (1) the mean scores of responsiveness items predicted the mean score over 10 sessions of therapists’ ratings of the therapeutic alliance, (2) the standard deviation scores of responsiveness items predicted the mean score over 10 sessions of therapists’ ratings of the therapeutic alliance (3) the mean scores of responsiveness items predicted the mean score over 10 sessions of clients’ ratings of the therapeutic alliance, and (4) the standard deviation scores of responsiveness items predicted the mean score over 10 sessions of clients’ ratings of the therapeutic alliance. We ran multiple linear regression models with a stepwise backward variable selection method based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) in order to select the most relevant predictors of the therapeutic alliance.

As a third step, to analyze whether responsiveness predicted the evolution of the therapeutic alliance in time, we ran linear mixed models where the variable “session” was included as a continuous variable as a fixed factor, we considered a random intercept and random time slope for each subject to account for the hierarchical structure of the data. We ran four separate models to test whether: (1) the mean scores of responsiveness items predicted the temporal evolution over 10 sessions of therapists’ ratings of the therapeutic alliance, (2) the standard deviation scores of responsiveness items predicted the temporal evolution over 10 sessions of therapists’ ratings of the therapeutic alliance (3) the mean scores of responsiveness items predicted the temporal evolution over 10 sessions of clients’ ratings of the therapeutic alliance, and (4) the standard deviation scores of responsiveness items predicted the temporal evolution over 10 sessions of clients’ ratings of the therapeutic alliance. Stepwise AIC method with backward selection was used to select the most relevant predictors.

Predictor variables exhibited statistically significant effects on the outcome variable when p-values were below 0.05. All models were run on R software environment for statistical computing (Version 4.1.0).

Results

Therapist Responsiveness as a Predictor of the Mean Score of the Therapeutic Alliance Rated by Therapists

None of the mean scores of the responsiveness items were selected as predictors of the mean score over 10 sessions of the therapeutic alliance rated by therapists.

The model testing whether standard deviation scores of the responsiveness items predicted the mean score over 10 sessions of the therapeutic alliance rated by therapists selected the following predictors: the standard deviation of item 6: therapist responds to patient’s verbally expressed feelings, β = −20.69, CI 95% [−40.88, −0.50], p < . 045, the standard deviation of item 12: patient verbally expresses feelings, β = −12.04, CI 95% [−30.69, 6.61], p < . 200 and the standard deviation of the item 6 x item 12, β = 15.08, CI 95% [−03.01, 33.17], p < . 100. As indicated by the reported coefficients, only item 6 (“therapist responds to patient’s verbally expressed feelings”) was significant. The selected variables explain 3.9% of the variance, R2 = .039.

Therapist Responsiveness as a Predictor of the Mean Score of the Therapeutic Alliance Rated by Clients

The model testing whether the mean scores of the responsiveness items predict the mean score over 10 sessions of the therapeutic alliance rated by clients selected as the only predictor the mean score of item 8: Therapist makes affirming, validating, normalizing, optimistic affirmations, β = 12.62, CI 95% [1.21, 24.03], p < .031. The selected variable explains 7.9% of the variance, R2 = .079.

The model testing whether standard deviation scores of the responsiveness items predict the mean score over 10 sessions of the therapeutic alliance rated by clients selected the following predictors: the standard deviation of item 8: Therapist makes affirming, validating, normalizing, optimistic affirmations, β = 7.29, CI 95% [−2.73, 17.31], p < .015 and the standard deviation of item 12: patient verbally expresses feelings, β = −9.25, CI 95% [−18.58, 0.09], p < .052. The selected variables explain 8.3% of the variance, R2 = .083.

Therapist Responsiveness as a Predictor of the Temporal Evolution of the Therapeutic Alliance Rated by Therapists

The first model we tested investigated the mean levels of the responsiveness items as predictors. The following variables were selected as predictors of the temporal evolution of the therapeutic alliance from therapists’ perspective: the mean level of item 8, Therapist makes affirming, validating, normalizing, optimistic affirmations, β = −6.38, CI 95% [−13.16, 0.41], p = 0.067, the mean level of item 6, therapist responds to patient’s verbally expressed feeling, β = −2.84, CI 95% [−8.92, 3.25], p = 0.357, the mean level of item 12: patient verbally expresses feelings, β = −1.63, CI 95% [−5.83, 2.57], p = 0.441 and the mean level of the item 6 x item 12, β = 1.62, CI 95% [−0.61, 3.85], p = 0.153. For this first model, the ICC was found to be ICC = 0.66, additionally, the results showed marginal R2 = 0.200 and conditional R2 = 0.729.

The second model we tested investigated the standard deviations of the responsiveness items as predictors. The following variables were selected as predictors of the temporal evolution of the therapeutic alliance from therapists’ perspective: the standard deviation of item 6: therapist responds to patient’s verbally expressed feeling, β = −19.72, CI 95% [−37.77, −1.68], p = 0.034, the standard deviation of item 12: patient verbally expresses feelings, β = −13.29, CI 95% [−29.92, 3.34], p = 0.117 and the standard deviation of the item 6 x item 12, β = 15.25, CI 95% [−0.90, 31.39], p = 0.065. For this second model, the ICC was found to be ICC = 0.67, additionally, the results showed marginal R2 = 0.190 and conditional R2 = 0.729.

Therapist Responsiveness as a Predictor of the Temporal Evolution of the Therapeutic Alliance Rated by Clients

The first model we tested investigated the mean levels of the responsiveness items as predictors. the mean level of item 8: Therapist makes affirming, validating, normalizing, optimistic affirmations, predicted the temporal evolution of the therapeutic alliance from clients’ perspective, β = 11.85, CI 95% [0.61, 23.09], p = 0.040. For this first model, the ICC was found to be ICC = 0.77, additionally, the results showed marginal R2 = 0.103, and conditional R2 = 0.789.

The second model we tested investigated the standard deviations of the responsiveness items as predictors. The standard deviation of item 12: patient verbally expresses feelings predicted the temporal evolution of the therapeutic alliance evaluation done by clients, β = −8.94, CI 95% [−18.20, 0.32], p = 0.059. For this model, the ICC was found to be ICC = 0.77, additionally, the results showed marginal R2 = 0.088 and conditional R2 = 0.788.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether the mean levels and the variability of different items assessing therapist responsiveness at session 1 predict the therapeutic alliance rated by therapists and clients during a 10-session therapy for BPD. We tested whether therapist responsiveness items predicted the mean levels of the therapeutic alliance and its temporal evolution over therapy.

Firstly, when considering the therapeutic alliance rated by therapists, the only selected predictors of the mean level of therapist alliance referred to variability (and not mean levels) which indicates that the present study illuminates therapist responsiveness in real time, which was discussed as a limitation by Culina et al. (Citation2023). The results indicate that, taken as individually separated items, the higher the variance of the items therapist responds to patient’s verbally expressed feelings and patients verbally expresses feelings, the lower the mean of the therapeutic alliance rated by therapists. However, if these two items were conditionally combined (i.e., assessing the therapist behavior, given a specific emotional expression by the client, in the form of statistical interaction), we found that the higher the variability of the responsiveness, the higher the mean score of the therapist perception of the alliance was. This could mean that the actual client context is crucial when it comes to the assessment of therapist responsiveness, and denotes the idea that therapist responds to a specific client behavior with a specific therapist behavior, which together predict a strong therapeutic alliance. While Culina et al. (Citation2023) noted a significant association between the global evaluation of responsiveness and therapists’ assessment of therapeutic alliance, the current study expands on these findings by conducting a more in-depth analysis, providing insights into the observed phenomena. It does so by examining specific behaviors contributing to therapist responsiveness within a brief timeframe, as opposed to providing a broad rating for the overall session's responsiveness, and by incorporating the client's behavior recognizing the interactive nature of responsiveness.

Although three predictors were selected, only the variability of the item therapist responds to patient’s verbally expressed feelings had a significant effect on the therapeutic alliance. This suggests that, taken as individual predictors during the first session, the more the therapist is required to alternate between moments of actively responding to expressed emotions to moments of low responding to emotions—which may be an indicator of high distress related to the experience of clients with BPD, or to the current therapy situation—the lowest the therapist will rate the therapeutic alliance; the effect of the item patient verbally expresses feelings went into the same direction. As soon as these two items were conditionally linked (i.e., if–then), potentially reflecting appropriate responsiveness to expressed emotions specifically, therapist responsiveness positively predicted the therapist perception of the mean alliance. Such conditional “if–then” methodological paradigms are particularly relevant for the study of therapist responsiveness from a variety of approaches (Constantino et al., Citation2021; Eubanks et al., Citation2018; Kramer et al., Citation2022).

We found consistent results for the model which focused on the temporal evolution of the therapeutic alliance from the therapist perspective in the first session with clients with BPD. The model showed negative relationships with the alliance for the mean levels of responsiveness items: therapist makes affirming, validating, normalizing, optimistic affirmations, the mean level of the item therapist responds to patient’s verbally expressed feelings, the mean level of the item patient verbally expresses feelings., when these items were taken individually. Again, when studying items 6 and 12 in a conditional context (i.e., if–then), the predictive relationship with the temporal evolution of the therapist-rated alliance was positive. This consistent result may show again that the client may express strong emotions and require a lot of validation, normalizing, and optimism—which may in its own right stress the development of the therapeutic alliance (McMain et al., Citation2015). If analyzed in a conditional way, the therapist-specific responses if the client expresses intense emotions predicted positively the therapeutic alliance over time.

The present study found specific therapist behaviors predicting the therapeutic alliance rated by the clients with borderline personality disorder. The only significant predictor found was the mean level of the item therapist makes affirming, validating, normalizing, optimistic affirmations: this therapist’s behavior at initial session seems to be related to a positive evaluation of therapeutic alliance by clients. This item was significant for both the average therapeutic alliance and the temporal evolution over the course of therapy. The fact that the therapist starts “on the right foot” may in this case not depend on the expressed distress by the client and may speak to the importance of affirmative, validating, and normalizing statements facing these clients.

From a clinical viewpoint, what seems particularly relevant for clients with BPD at the beginning of therapy is that therapists normalize the experiences, maintain an optimistic outlook, and validate the issues that clients bring to the therapeutic session. Instead, what seems to negatively influence therapists’ evaluation of the therapeutic alliance are the feelings verbalized during the initial session by clients and how much therapists need to respond accordingly, especially when this adds a lot of variability to the session. In the context of expressed emotion by the client, a conditional model may prove to be most important when studying the impact of in-session therapist responses on further therapy processes. In the context of BPD specifically, the degree of instability and the severity of the client’s difficulties can make the therapeutic process particularly unpredictable, which increases the risk of therapist feeling overwhelmed, frustrated or pessimistic (McMain et al., Citation2015). It is exactly because of these specificities of BPD and its manifestations, that the question of how a therapist can manage to be appropriately responsive deserves attention (Levy et al., Citation2010; McMain et al., Citation2015).

Therapist appropriate responsiveness is a crucial ingredient for treatment process and outcome and therefore needs to be studied in a minute-by-minute fashion. The nature of therapist responsiveness poses several methodological obstacles making it a challenging task for researchers (Hatcher, Citation2015; Stiles, Citation2009, Citation2013, Citation2021): therapist responsiveness cannot be translated into a specific behavior, intervention or technique and the same therapist can be differently responsive depending on the session, the person or the context; the same technique or intervention can suit one client and be exaggerated or not enough for someone else (Stiles, Citation2021; Stiles & Horvath, Citation2017; Wu & Levitt, Citation2020). The present study used the Therapist Responsiveness Scale and proposed conditional relationships for certain items, so that appropriate responsiveness can really be assessed in a context-dependent way. This approach highlights previously unexplored aspects. Indeed, the literature on therapist responsiveness in BPD is limited, with most studies focusing on the impact of applying MOTR (Caspar, Citation2007), which enhances therapist responsiveness by personalizing treatment (Kramer, Kolly et al., Citation2014, Citation2017; Signer et al., Citation2020; Zufferey et al., Citation2019). Moreover, studies specifically examining the relationship between therapist responsiveness and working alliance in the context of BPD are rare. To the best of our knowledge, the study by Culina et al. (Citation2023) is the only one, for therapy with clients with BPD, to do so by using a validated scale specifically designed to rate in-session therapist responsiveness. The present study extends this research by conducting more detailed analyses of specific therapist behaviors rated over short intervals, while also integrating client behaviors. As highlighted by Kramer (Citation2021), grasping the complexities of therapist responsiveness in the treatment of BPD is extremely relevant, given the unique challenges of developing and maintaining a collaborative therapeutic environment with clients with BPD.

The study presents some limitations that need to be discussed. It might be argued that because of the above points, the choice to study specific therapist behaviors is not relevant. Additionally, as the present study presents secondary analysis of archival data, all of the limitations of the original articles need to be taken into consideration (see Culina et al., Citation2023; Kramer, Kolly et al., Citation2014). First, the sample size is relatively small; second, the suboptimal quality of audio or video images in certain videotapes posed challenges in coding nonverbal aspects of the interaction; third, the brief duration of therapy might be insufficient, and the effects of longer-term treatments remain unknown.

In sum, the results of the current study contribute to give a more fine-grained picture of the dynamics at play during the very first session of therapy for clients with severe psychological problems, including borderline personality disorder. The study suggests that the type of specific therapist in-session behavior, some in direct response to client emotional expressions, some independently from the client expressions, plays a crucial role for predicting the level and the course of the therapeutic alliance over a brief psychotherapy.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackerman, S. J., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (2003). A review of therapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00146-0

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision).

- Anderson, T., Knobloch-Fedders, L., Stiles, W. B., Ordonez, T., & Heckman, B. D. (2012). The power of subtle interpersonal hostility in psychodynamic psychotherapy: A speech act analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 22(3), 384–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2012.658097

- Arntz, A., Mensink, K., Cox, W. R., Verhoef, R. E. J., van Emmerik, A. A. P., Rameckers, S. A., Badenbach, T., & Grasman, R. P. P. P. (2023). Dropout from psychological treatment for borderline personality disorder: A multilevel survival meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 53(3), 668–686. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722003634

- Caspar, F. (2007). Plan analysis. In T. D. Eells (Ed.), Handbook of psychotherapeutic case formulations (2nd ed., pp. 251–289). Guilford Press.

- Constantino, M. J., Goodwin, B. J., Muir, H. J., Coyne, A. E., & Boswell, J. F. (2021). Context-responsive psychotherapy integration applied to cognitive behavioral therapy. In J. C. Watson & H. Wiseman (Eds.), The responsive psychotherapist: Attuning to clients in the moment (pp. 151–170). American Psychological Association.

- Culina, I., Fiscalini, E., Martin-Soelch, C., & Kramer, U. (2023). The first session matters: Therapist responsiveness and the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 30(1), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2783

- Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., Horvath, A. O., & Wampold, B. E. (2021). Examining therapist effects in the alliance-outcome relationship: A multilevel meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(5), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000637

- Del Rio Olvera, F. J., Rodriguez-Mora, A., Senin-Calderon, C., & Rodriguez-Testal, J. F. (2022). The first session in the one that counts: An exploratory study of therapeutic alliance. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1016963. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1016963

- Dimaggio, G., Maillard, P., MacBeth, A., & Kramer, U. (2019). Effects of therapeutic alliance and metacognition on outcome in a brief psychological treatment for borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry, 82(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2019.1610295

- Elkin, I., Falconnier, L., Smith, Y., Canada, K. E., Henderson, E., Brown, E. R., & Mckay, B. M. (2014). Therapist responsiveness and patient engagement in therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 24(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.820855

- Elliott, R., Bohart, A. C., Watson, J. C., & Murphy, D. (2018). Therapist empathy and client outcome: An updated meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000175

- Eubanks, C. F., Muran, J. C., & Safran, J. D. (2018). Alliance rupture repair. A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 508–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000185

- First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Benjamin, L. S. (1997). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). American Psychiatric Press.

- Flückiger, C., Del Re, A. C., Wampold, B. E., & Horvath, A. O. (2018). The alliance in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 316–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000172

- Gunderson, J. G., & Links, P. (Collaborator). (2014). Handbook of good psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

- Gunderson, J., Masland, S., & Choi-Kain, L. (2018). Good psychiatric management: A review. Current Opinion in Psychology, 21, 127–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.12.006

- Hatcher, R. L. (2015). Interpersonal competencies: Responsiveness, technique, and training in psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 70(8), 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039803

- Hilsenroth, M. J., & Cromer, T. D. (2007). Clinician interventions related to alliance during the initial interview and psychological assessment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 44(2), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.44.2.205

- Hirsh, J. B., Quilty, L. C., Bagby, M., & McMain, S. F. (2012). The relationship between agreeableness and the development of the working alliance in patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 26(4), 616–627. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2012.26.4.616

- Horvath, A. O., Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., & Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022186

- Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223

- Iliakis, E. A., Ilagan, G. S., & Choi-Kain, L. W. (2021). Dropout rates from psychotherapy trials for borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 12(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000453

- Kadur, J., Lüdemann, J., & Andreas, S. (2020). Effects of the therapist's statements on the patient's outcome and the therapeutic alliance: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 27(2), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2416

- Kramer, U. (2021). Therapist responsiveness in treatments for personality disorders. In J. C. Watson & H. Wiseman (Eds.), The responsive psychotherapist: Attuning to clients in the moment (pp. 237–256). American Psychological Association.

- Kramer, U., Eubanks, C. F., Bertsch, K., Herpertz, S. C., McMain, S., Mehlum, L., Renneberg, B., & Zimmermann, J. (2022). Future challenges in psychotherapy research for personality disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 24(11), 613–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-022-01379-4

- Kramer, U., Flückiger, C., Kolly, S., Caspar, F., Marquet, P., Despland, J.-N., & de Roten, Y. (2014). Unpacking the effects of therapist responsiveness in borderline personality disorder: Motive-oriented therapeutic relationship, patient in-session experience and the therapeutic alliance. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(6), 386–387. https://doi.org/10.1159/000365400

- Kramer, U., Keller, S., Caspar, F., de Roten, Y., Despland, J. N., & Kolly, S. (2017). Early change in coping strategies in responsive treatments for borderline personality disorder: A mediation analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(5), 530–535. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000196

- Kramer, U., Kolly, S., Berthoud, L., Keller, S., Preisig, M., Caspar, F., Berger, T., De Roten, Y., Marquet, P., & Despland, J. N. (2014). Effects of motive-oriented therapeutic relationship in a ten-session general psychiatric treatment of borderline personality disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(3), 176–186. https://doi.org/10.1159/000358528

- Kramer, U., Kolly, S., Charbon, P., Ilagan, G. S., & Choi-Kain, L. W. (2022). Brief psychiatric treatment for borderline personality disorder as a first step of care: Adapting general psychiatric management to a 10-session intervention. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 13(5), 516–526. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000511

- Kramer, U., & Stiles, W. B. (2015). The responsiveness problem in psychotherapy: A review of proposed solutions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 22(3), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12107

- Lavik, O. K., Froysa, H., Brattebo, K. F., McLeod, J., & Moltu, C. (2018). The first session of psychotherapy: A qualitative meta-analysis of alliance formation processes. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 28(3), 348–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000101

- Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, D. V., Weiller, E., Amorim, P., Bonora, I., Harnett Sheehan, K., Janavs, J., & Dunbar, G. C. (1997). The mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: Reliability and validity according to the CIDI. European Psychiatry, 12(5), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8

- Levy, K. N., Beeney, J. E., Wasserman, R. H., & Clarkin, J. F. (2010). Conflict begets conflict: Executive control, mental state vacillations, and the therapeutic alliance in treatment of borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 20(4), 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503301003636696

- Macewan, G. H. (2008). The efforts of therapists in the first session to establish a therapeutic alliance [Masters theses]. University of Massachusetts, Amherst. https://doi.org/10.7275/825619

- McMain, S., Boritz, T. Z., & Leybman, M. J. (2015). Common strategies for cultivating a positive relationship in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 25(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038768

- Signer, S., Estermann Jansen, R., Sachse, R., Caspar, F., & Kramer, U. (2020). Social interaction patterns, therapist responsiveness, and outcome in treatments for borderline personality disorder. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 93(4), 705–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12254

- Spencer, J., Goode, J., Penix, E. A., Trusty, W., & Swift, J. K. (2019). Developing a collaborative relationship with clients during the initial sessions of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 56(1), 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000208

- Stiles, W. B. (2009). Responsiveness as an obstacle for psychotherapy outcome research: It's worse than you think. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 16(1), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01148.x

- Stiles, W. B. (2013). The variables problem and progress in psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy, 50(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030569

- Stiles, W. B. (2021). Responsiveness in psychotherapy research: Problems and ways forward. In J. C. Watson, & H. Wiseman (Eds.), The responsive psychotherapist: Attuning to clients in the moment (pp. 15–36). American Psychological Association.

- Stiles, W. B., Honos-Webb, L., & Surko, M. (1998). Responsiveness in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(4), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00166.x

- Stiles, W. B., & Horvath, A. O. (2017). Appropriate responsiveness as a contribution to therapist effects. In L. G. Castonguay & C. E. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others?: Understanding therapist effects (pp. 71–84). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000034-005

- Van Benthem, P., Spijkerman, R., Blanken, P., Kleinjan, M., Vermeiren, R. R. J. M., & Henriks, V. M. (2020). A dual perspective on first-session therapeutic alliance: Strong predictor of youth mental health and addiction treatment outcome. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(11), 1593–1601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01503-w

- Wu, M. B., & Levitt, H. M. (2020). A qualitative meta-analytic review of the therapist responsiveness literature: Guidelines for practice and training. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 50(3), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-020-09450-y

- Yeomans, F. E., Gutfreund, J., Selzer, M. A., Clarkin, J. F., Hull, J. W., & Smith, T. E. (1994). Factors related to drop-outs by borderline patients: Treatment contract and therapeutic alliance. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 3(1), 16–24.

- Zufferey, P., Caspar, F., & Kramer, U. (2019). The role of interactional agreeableness in responsive treatments for patients With borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 33(5), 691–706. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2019_33_367