ABSTRACT

Background

This paper explores K-12 interdisciplinary learning in the humanities (IL-Humanities), an area that, until now, has seen limited research focus compared to its STEM counterparts. We asked: (1) What are the outcomes of IL-Humanities in terms of interdisciplinary competences? (2) How do learners in these environments engage in cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work?

Methods

We assessed the efficacy of IL-Humanities across ten Israeli middle schools through a pre-post intervention/comparison design, utilizing the novel Interdisciplinary Competences Assessment (ICA). Qualitative insights into the learning processes within classrooms were derived using discourse analysis methods.

Findings

Students’ interdisciplinary competences were found to increase following the IL-Humanities interventions. Qualitative analyses offered “thick descriptions” of the process: Students leveraged cross-disciplinary transfer of knowledge to deepen their understanding of complex phenomena and used personal narratives to engage in identity work.

Contribution

This study enhances interdisciplinary education research by: (1) providing and operationalizing a model of interdisciplinary competences as an assessment tool; (2) demonstrating the effectiveness of IL-Humanities environments in developing these competences; and (3) advancing our understanding of learners’ engagement with cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work.

Introduction

Interdisciplinary teaching and learning, broadly defined as the integration of two or more subjects or disciplines (St Clair & Hough, Citation1992), has been practiced in K-12 settings for over a century (Grossman et al., Citation2001; Schwab et al., Citation1978; Tyler, Citation1949). With roots in Dewey’s (Citation1938) thought and the Progressive Education movement of the 1920’s, it has been enjoying a renaissance since the 2000s (Dowden, Citation2007; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2018; Kidron, Citation2019; Rothgangel & Vollmer, Citation2020); has been adopted as official government policy in Hong Kong (Zhan et al., Citation2017), Singapore (Lam et al., Citation2013), South Africa (Naidoo, Citation2010), Finland (Mård & Hilli, Citation2022) and elsewhere; and has been endorsed by international organizations (OECD, Citation2019; UNESCO International Commission for the Future of Education, Citation2021).

This paper focuses on processes and outcomes of interdisciplinary learning (IL) in K-12 settings in the humanities. Integrating and adapting various definitions (Apostel, Citation1972; Chettiparamb, Citation2007; Frodeman, Citation2017; Helmane & Briška, Citation2017; Holley, Citation2017; Nikitina, Citation2005), we consider interdisciplinary learning in the humanities (IL-Humanities) to be any sort of integrative learning activity that meaningfully connects the learner to the broader human condition, culture, history, thought, and products, while drawing from multiple fields of inquiry and knowledge within the humanities. IL-Humanities can be achieved through a broad range of integrative pedagogies, as will be later discussed.

Such a significant form of learning should be backed by a robust research program, yet, to date, most research on IL focuses on higher education (e.g., DeZure, Citation2017; Kidron & Kali, Citation2015; Spelt et al., Citation2009) and/or on the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM, e.g., Li et al., Citation2020; Takeuchi et al., Citation2020). Neither body is fully applicable to K-12 IL-Humanities, due to developmental, content and methodology differences. Existing research is thus insufficient to provide an empirical foundation for the current interdisciplinary turn in K-12 settings in the humanities.

Despite the urgent global need for a shared sense of humanity, the humanities face a persistent crisis, evident in their diminishing prestige within the public sphere and in higher education in Israel, where this study took place (Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Citation2023), and around the world (Meranze, Citation2015; Nussbaum, Citation2012; Tay et al., Citation2018). This situation served as the impetus for our study, predicated on the premise that IL-Humanities, as an innovative pedagogical approach for enhancing student engagement in the humanities, is worth exploring. We hypothesized that IL-Humanities could enhance students’ abilities and opportunities to engage with “the great issues of truth, goodness, beauty, and justice” (Klein & Frodeman, Citation2017, p. 144), by offering deep inter-connections of knowledge on such issues and by relating them to the students’ own experiences and identities. We therefore set out to explore the efficacy of teacher-designed IL-Humanities units in middle schools in Israel in terms of changes to student competences, and to advance our understanding of the learning processes that ensued.

The article unfolds as follows: The “Conceptual Framework” section differentiates between two forms of IL-Humanities: cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work, exploring their potential interrelations from an ecological learning perspective. In the “Literature Review,” we present empirical findings related to these processes. By proposing a schema that defines three measurable interdisciplinary competences, we operationalize our concepts and apply this framework in an empirical research context. The “Methods” and “Results” sections detail the study’s context, design, outcomes, and findings. Finally, in the “Discussion,” we reflect on the broader implications of our findings and suggest directions for future research.

Conceptual framework for IL-Humanities

In previous research, the concept of interdisciplinarity has been used to refer to various, partially overlapping, domains and activities, including the nature of knowledge and its organization (Darbellay, Citation2019; Klein, Citation2017), knowledge production through research (Huutoniemi et al., Citation2010), learning and cognition (Boix-Mansilla, Citation2017; Nikitina, Citation2005), and teaching (Helmane & Briška, Citation2017; Markauskaite, Carvalho, et al., Citation2023). Each of these offers its own sets of definitions and uses for “interdisciplinarity” and its sub-types. This study is about interdisciplinary learning and cognition. Like previous work (e.g., Huutoniemi et al., Citation2010; Markauskaite, Carvalho, et al., Citation2023), we use the term “interdisciplinary” as an overarching “umbrella” term, in this case, for learning that occurs across subjects and epistemological boundaries.

A “relatively canonical” (Darbellay, Citation2019, p. 91) typology of interdisciplinary practices (Apostel, Citation1972; Klein, Citation2017) categorizes interdisciplinarity according to its degree of disciplinary integration. In this typology, Multidisciplinary involves “a juxtaposition of various disciplines” (Apostel, Citation1972, p. 25), interdisciplinarity* implies integrating concepts, methods, and theories across disciplines (we follow Huutoniemi et al., Citation2010 in using an asterisk to connote the specific, rather than generic, meaning of the term) and transdisciplinarity is a term that has taken on various meanings but generally implies moving beyond disciplines altogether (Klein, Citation2017). However, in the context of K-12 education within the humanities, we propose a dual typology reflecting two distinct forms of interdisciplinary learning. It is important to recognize that knowledge production differs from K-12 learning; thus, forms of interdisciplinary engagement in these contexts do not necessarily align. One distinction lies in the conceptualization of “disciplines” in academic research as opposed to “school subjects” among K-12 learners. Further, whereas research is primarily designed to change the state of knowledge, learning in K-12 settings is primarily intended to change the learners.

Previous studies have highlighted two distinct learning processes associated with interdisciplinary learning in the humanities within K-12 settings. We term the first process cross-disciplinary knowledge building to indicate that it involves learning across subjects by either exploring, juxtaposing or integrating disciplinary perspectives. We name the second transdisciplinary identity work to connote the way it transcends subject boundaries altogether by focusing on students’ identities. We describe each conceptually, followed by empirical findings about each type of interdisciplinary learning.

Cross-disciplinary knowledge building

Cross-disciplinary knowledge building is the process of gaining, organizing, and constructing knowledge by drawing on different subjects. According to Boix Mansilla et al. (Citation2000), advancing learners’ capacity to integrate knowledge and modes of thinking in two or more disciplines to produce a cognitive advancement is the primary goal of interdisciplinary learning environments. Accomplishing this goal requires “(1) an emphasis on knowledge use, (2) a careful treatment of each discipline involved, and (3) appropriate interaction between disciplines” (pp. 25–26).

Engaging with multiple subjects typically requires learners to first comprehend core concepts and develop cognitive skills from each discipline (e.g., Reading like a historian; Reisman, Citation2012). It can then involve engagement in comparisons across disciplines, and/or in integration. According to Boix Mansilla et al. (Citation2000), Integration means that “disciplines are not simply juxtaposed. Rather, they are purposefully intertwined. Concepts and modes of thinking in one discipline enrich students’ understanding in another discipline … concepts that emerge as findings in one discipline contribute to generating hypotheses in another domain” (p. 29). For example, the historical question of how Nazism took hold in Germany in the 1930s can be explained by drawing on findings from social psychology (Milgram, Citation1963) and the history of biology (the eugenics movement).

Transdisciplinary identity work

Transdisciplinary identity work catalyses change in learners, going beyond the focus on knowledge acquisition. It facilitates the construction of learners’ identities, values, and worldviews, fostering their personal development and flourishing. It is helpful to think of this as a process of authoring oneself (Rahm et al., Citation2022), following McAdams’ et al.’s (Citation2013) theory of narrative identity, according to which a person’s internalized and evolving life story provide their life with a sense of unity and purpose. An example of this is the learning that takes place in the program “Facing History and Ourselves,” whose content and methods are geared toward “making personal connections to the subject matter and linking the past to current social and civic issues [in contrast with other] humanities courses that emphasize teaching factual information and de-emphasize drawing connections” (Barr et al., Citation2015, pp. 5–6). Transcending disciplinary boundaries allows learners to bring their identities to the fore more readily, by foregrounding their personal experiences, values and meanings, rather than the knowledge to be acquired (Cohen et al., Citation2024; Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2018; Solomon et al., Citation2022).

While transdisciplinary identity work can mediate the construction of learners’ identities in any combination of subjects, a focus on the humanities organically activates mechanisms of cultural and social immersion, embeddedness, socialization, and reflectiveness, all of which can positively impact students’ growth (Tay et al., Citation2018). Successful transdisciplinary identity work in the humanities involves envisionment-building, that is, “patterns of discussion and interaction that allow students to explore emerging ideas and multiple perspectives” (Applebee et al., Citation2007, p. 1015). Such learning processes center on learners’ values and beliefs, and develop their sense of self, identity, autonomy, and agency.

IL-Humanities from an ecological perspective

Understanding the relationship between cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work is key to designing powerful learning environments that capitalize on the unique affordances of IL-Humanities in K-12 settings.

One way to conceptualize the complex connections between these two learning processes is through an ecological perspective on learning. Ecological perspectives consider learning as hybrid, distributed and unbounded processes that occur on personal, relational and community levels. Like ecosystems, learning environments and processes tend to be multilayered and include individuals, relations, communities, and entire populations, each of whom is constantly in flux. The ecological view of learning thus recognizes that within any learning environment, various processes unfold simultaneously, on different planes of activity and within various contexts, even as they shape and constitute one another (Markauskaite, Goodyear, et al., Citation2023).

An ecological lens can be used to analyze the emergent dynamics of learning within classrooms (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2007; Sangrá et al., Citation2019), and through this ecological perspective it becomes clear that conceptualizing IL-Humanities in either/or terms, either as cross-disciplinary knowledge building or as transdisciplinary identity work, falls short. A more credible view would consider both processes to play out in tandem. We next draw on the ecological metaphor to introduce two theoretical views on IL-Humanities that might frame the connection between the two learning processes.

Firstly, it is possible to view these two processes as stages of progression, where knowledge building may (but does not necessarily) evolve into identity work. Movement between these stages need not be unidirectional. Applebee et al. (Citation2007) proposed a typology of interdisciplinary teaching and learning. Their typology distinguished between correlated curricula, where disciplinary concepts from multiple subjects are brought to bear on a single theme; shared curricula, where disciplinary concepts overlap and support one another; and reconstructed curricula, where disciplinary boundaries are eliminated, and transdisciplinary concepts are reconstructed. Their study showed how the first two types of curricula mainly mediated knowledge building, while the latter mediated “envisionment-building,” which maps onto what we call identity work. Applebee et al. (Citation2007, p. 1033) observed an “ebb and flow,” whereby teachers exhibited “the ability to move along the interdisciplinary continuum” (p. 1034). The notion of an organically occurring ebb and flow would be one way to conceptualize the connection between knowledge building and identity work: Each comes to the fore at times and recedes into the background at others.

A second conceptualization that evokes an ecological lens posits that because learners and their social environments are co-constitutive, any cross-disciplinary knowledge building can also be understood in terms transdisciplinary identity work, and vice versa. Educational philosopher Paulo Freire proposed that these two dimensions of interdisciplinarity can coalesce to enact dialogical education, by linking knowledge and identity:

In contrast with the antidialogical and non-communicative “deposits” of the banking method of education, the program content of the problem-posing method—dialogical par excellence—is constituted and organized by the students’ view of the world, where their own generative themes are found. The content thus constantly expands and renews itself. The task of the dialogical teacher in an interdisciplinary team working on the thematic universe revealed by their investigation is to “re-present” that universe to the people from whom she or he first received it—and “re-present” it not as a lecture, but as a problem. (Freire, Citation1970/1996, p. 90)

Freire identified a direct link between the two interdisciplinary learning processes that we discussed, and showed how they simultaneously play out on different planes. In his view, generating new and relevant insights about the world can help learners engage in self-authorship as they reposition themselves vis-à-vis their social surroundings. Similarly, meaningful identity work might contribute to efforts to construct novel insights about the world, which require crossing disciplinary boundaries and integrating them. In the next section, we consider what previous research has found about both learning processes in IL-Humanities.

Literature review

Cross-disciplinary knowledge building—process and outcomes

Several studies have found that learners leverage IL-Humanities opportunities to advance their understanding of complex concepts and develop sophisticated higher-order thinking skills. Kuisma and Ratinen (Citation2021) investigated a learning environment that combined subjects from the humanities, arts, and sciences and explored how interdisciplinary learning helped students experience conceptual change in their structure of knowledge. For many of the students, the “Aha!” moments in which concepts and their attributes shifted across entire subjects (“ontological trees”) were ones of deep creativity and insight. Similarly, both De La Paz (Citation2005) and Schuitema et al. (Citation2009) showed how integrating two subjects in the humanities advanced learners’ argumentation skills, reflecting enhanced integration abilities. For example, when combining history and language arts, learners wrote essays that were more historically accurate and persuasive, when compared to a control group.

Studies of academic achievement related to knowledge building in IL-Humanities offer inconclusive results: some indicate no discernible advantage of interdisciplinary approaches over disciplinary ones (e.g., Dorion, Citation2009; Reiska et al., Citation2018) while others report positive outcomes for IL (e.g., improved school grades - Birsa, Citation2018; better understanding of the topic - Girod & Twyman, Citation2009; Lo, Citation2015). However, in the neighboring interdisciplinary domain of STEM studies, robust meta-analyses have substantiated the efficacy of IL in enhancing knowledge-related outcomes. Batdi et al. (Citation2019) found the average effect size for academic achievement through STEM to be 0.65 and Kang et al. (Citation2018) found it to be 0.52. Although no such meta-analysis exists on IL-Humanities, this suggests that perhaps, with suitable adaptations, integrating multiple subjects in the humanities might also yield successful knowledge-related outcomes.

Transdisciplinary identity work—process and outcomes

Studies focusing on moral development, autonomy, identity formation and personal growth within IL-Humanities contexts frequently, but not always, report beneficial effects. One study of an IL-Humanities program on ethical and citizenship awareness revealed significantly elevated levels of moral reasoning post-intervention compared to a control group (Araújo & Arantes, Citation2009), while a study of a different program with a similar ethical focus (Barr et al., Citation2015) did not find significant change in moral development.

In terms of student autonomy and personal development, Applebee et al. (Citation2007) found that reconstructed curricula (which promote transdisciplinary learning) generated significantly more student discussions and position-taking than correlated curricula (which emphasizes cross-disciplinary learning). Another study found that IL-Humanities involving outdoor exploration deepened students’ local identity and enhanced their sense of autonomy and agency (Beames & Ross, Citation2010). Additional studies found enhanced self-regulated learning (DiDonato, Citation2013), higher levels of self-advocacy (Ivzori et al., Citation2020), and even a deeper spiritual awareness (Clark & Button, Citation2011).

Transdisciplinary curricula have also been found to support equitable multicultural identity building. For example, Ferreira et al. (Citation2022) studied disenfranchised migrant children who participated in a unit that integrated citizenship education and language arts. The study demonstrated the affordances of IL-Humanities for engaging refugee-background learners in telling meaningful stories about their past, present and future. In another example, Fitzpatrick et al. (Citation2018) described a Negotiated Integrated Curriculum that attempts to “redress the power imbalance” (p. 455) between teachers and students by removing disciplinary boundaries, and inviting learners to determine the objectives, foci, and methods of inquiry. Similarly, in another study of an IL-Humanities program, multiple subjects were integrated in the production of a play (De Korne, Citation2012). Outcomes included “the normalization of multilingual practices […] as well as participation structures that validate students as speakers and knowledge producers” (p. 496).

Studies focusing on identity work in IL-STEM, uncover a similar finding: In addition to fostering learners’ scientific identities (Calabrese Barton et al., Citation2012; Van Horne & Bell, Citation2017), IL-STEM promotes critical identity work. In several studies, learning processes helped marginalized and disempowered students develop a justice-oriented community-based identity (Greenberg et al., Citation2020), a resistance to hegemonies (Allen & Eisenhart, Citation2017), and a connection between their cultural and scientific identities (Rahm et al., Citation2022). This matches one of several trendlines of transdisciplinarity identified by Klein (Citation2017)—transdisciplinarity as transgressive: “[Transdisciplinarity] began appearing more frequently as a label for knowledge formations shaped by critical imperatives in humanities […] and societal movements for change” (p. 30).

In conclusion, research in IL-Humanities has focused on knowledge building and identity work, which have been typically studied separately. Also, while interdisciplinary performance assessment rubrics have been proposed for STEM contexts (Linn & Eylon, Citation2011) and for higher education (Boix-Mansilla et al., Citation2009; Schijf et al., Citation2023), we found no equivalent for K-12 IL-Humanities learners. These lacunae prompted us to operationalize both learning processes through the concept of interdisciplinary competences.

A proposed schema of interdisciplinary competences

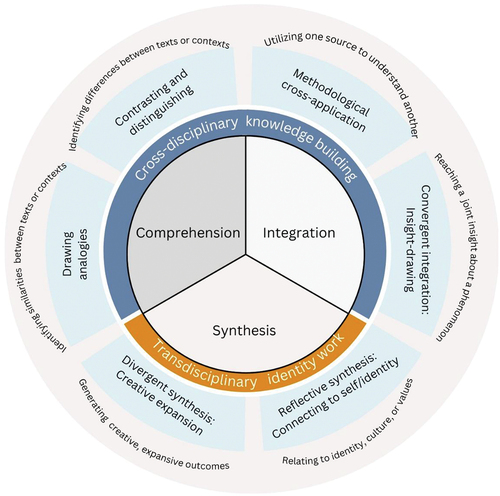

Competences are comprehensive abilities to perform tasks, actions, or roles in a manner that benefits both individuals and their environment. These multi-dimensional abilities involve knowledge, skills, attitudes and values (Rychen, Citation2016), making this concept well-suited to assess both knowledge building and identity work. Competency-based learning has been identified as a potent mediator of motivation, perceived autonomy, and learning outcomes in STEM higher education (Henri et al., Citation2017), possibly indicating its potential for assessing IL-Humanities as well. Drawing on our conceptual and empirical literature reviews, we introduce a novel schema that encompasses three interdisciplinary competences—comprehension, integration, and synthesis—and two actions for each. Although this schema could be relevant across different interdisciplinary contexts, it was specifically designed with IL-Humanities in mind.

Comprehension. An important aspect of learning, reasoning, problem-solving, and decision-making (McNamara & Magliano, Citation2009), comprehension encompasses essential aspects of learners’ understanding such as the connections between text, context, prior knowledge, and the activation of related concepts. In single-subject contexts, various models such as the Documents Model Framework (Britt & Rouet, Citation2012) distinguish between making sense of the contents of multiple sources and reconciling the contexts of the sources (Barzilai et al., Citation2018; Nelson & King, Citation2022). However, comprehending texts across multiple disciplines involves additional cognitive elements such as identifying different contextual disciplinary frameworks and being able to compare them (Bråten et al., Citation2020). Building on these sources, we posit that students who are competent in interdisciplinary comprehension in the humanities can (1) identify and discuss similarities between sources from different subjects/disciplines (“Drawing analogies”), and (2) identify and expound upon differences between them (“Contrasting and distinguishing”).

Integration. Based on the concept of integrative complexity (Suedfeld & Tetlock, Citation2014), we suggest that this competency involves incorporating different elements into a joint schema. Despite its centrality, empirical investigations into its underlying processes remain limited (Boix-Mansilla, Citation2017). An epistemology of interdisciplinary learning as integration proposed by Boix-Mansilla (Citation2017), positions pragmatic constructionism at its core, defining it as “a system of thought in reflective equilibrium” (p. 268). Integration, marked by goal-oriented and purposeful reasoning, applies to various combinations of topics, leverages disciplinary insights and integrative thinking, and undergoes constant revision through critical examination. Students who are competent at interdisciplinary integration can (1) use methods, terms, and ideas from one discipline to explain a source from another (“Methodological cross-application”); and (2) integrate sources across disciplinary boundaries to reach new and shared insights (“Convergent integration: Insight drawing”).

Synthesis. The third competency entails the application of integrated knowledge from disparate sources to reflect and connect. It is a process of bringing the integration into conversation with oneself. Often, its outcomes are expressed through creative endeavors of self-expression. While synthesis is a natural human activity, interdisciplinary synthesis requires instruction and practice (Boix-Mansilla, Citation2017). The ability to synthesize can involve self-reflection, identity formation, moral development and/or creative pursuits (Sill, Citation2001). Students competent in synthesizing can (1) express their insights creatively through artistic expressions, social action, or dialogue (“Divergent synthesis: Creative expansion”); and (2) leverage integrative insights to reflect on their self, identity, values and beliefs (“Reflective synthesis: Connecting to self/identity”).

Jointly, these three competences allow IL-Humanities learners to recognize the intricate interconnectedness of seemingly unrelated facets of social reality, while appreciating the critical role of social context (Berger & Luckmann, Citation1969); and incorporate them in their own ever-evolving process of self-authorship. presents these competences as a framework that can help to evaluate interdisciplinary learning in the humanities.

Research questions and author positionality

To assess the efficacy of IL-Humanities and to advance our understanding of cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work, we collaborated with educational practitioners and policymakers in the design and implementation of a study on interdisciplinary learning in the humanities in ten Israeli middle schools. We asked two questions:

What are the outcomes of IL-Humanities in terms of interdisciplinary competences?

How do learners engage in cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work?

As educational scholars, our perspectives on learning and preferred research methodologies varied considerably. The disciplinary variety within our research group, which included a social psychologist, two learning scientists, three educational philosophers, and an educational historian, led us to explore IL-Humanities from multiple perspectives. An ecological learning perspective informed our choice to consider both individual learners and classroom discourse as separate but complementary units of analysis, the first through a learning outcomes lens, and the second through an intersubjective, communal lens, and then to integrate these findings. This diversity led to various challenges, as we experienced firsthand the attachment to professional identities that hindered interdisciplinary efforts (Grossman et al., Citation2001; Wineburg & Grossman, Citation2000). While challenging, our iterative, interdisciplinary dialogue also served as an important resource, as it provided us with direct insight into the inner-workings of IL-Humanities. We return to our experiences as a team in the “Conclusion” section.

Methods

Study context

The broader context of the study was a research-practice partnership (RPP; Coburn et al., Citation2013) that our research group forged with Israel’s Ministry of Education and ten public middle schools. Prior to the commencement of this study, senior policymakers at the Ministry had envisioned a shift to interdisciplinary learning in the humanities throughout Israel’s education system, as part of efforts to advance a set of cognitive, emotional, and social goals, such as promoting critical thinking, digital literacy, self-awareness, and global literacy (Ministry of Education [MoE], Citation2021). The schools that joined our study were interested in implementing new interdisciplinary curricula or strengthening existing ones primarily from a desire for educational renewal and enhanced student engagement in humanities studies (Cohen et al., Citation2024).

In year 1, 43 leading teacher from ten schools were trained in a shared, national-level course on the foundations of IL-Humanities. In year 2, the leading teacher teams from year 1 led school-wide initiatives in their schools. Overall, 127 teachers from ten schools participated in ten collaborative 30-hour professional development (PD) courses and then developed and taught IL-Humanities units. The courses offered teachers definitions and typologies of interdisciplinarity and provided them with tools to help cultivate interdisciplinary competences among their students, including a model for developing their own IL-Humanities units to facilitate both cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work. Significant time was allocated to teacher teams developing interdisciplinary curricular units, with the researchers’ support and guidance. To that end, participants were provided with various scaffolds, such as worksheets, poster templates, and opportunities to share their work collaboratively and receive feedback. During this period, 25 educators from the original teacher leadership cohort (year 1) also participated in an advanced 30-hour course by Zoom, where they shared ideas and offered feedback to each other, in their capacity as IL leaders in their schools.

By the end of the course, each team had designed an interdisciplinary unit in the humanities. For example, one team planned a thematic unit on courage that integrated sources from three subjects: literature, Bible, and language arts. By comparing the various approaches to courage in each discipline, this team hoped to mediate cross-disciplinary knowledge building (in the teachers’ own words: “cognitive tools for analysis and comparative observation”) and to promote transdisciplinary identity work (“expand learners’ Jewish identity and consciousness and position it in a universal cultural context.”) Other interdisciplinary units developed included: Social protests; Heroes’ journeys; Colonialism and its effects; Eco-Poetics; Women Path Blazers and Person and Environment. For further details see Supplementary Information part 1: The professional development courses.

Participants

Participants in the full study included 142 teachers and 1109 students in 34 classes drawn from 10 schools. Of them, 903 students and 127 teachers participated in interdisciplinary learning units while 206 students and 15 teachers formed a comparison group. In this paper we focus on two student subsamples, one for each research question:

586 students who were assessed in terms of their interdisciplinary competences, using the Interdisciplinary Competences Assessment (ICA; see in “Data collection and analysis”). These students were from 17 classes in five schools. 380 students were the intervention group and 206 were the comparison group. See for details.

Table 1. ICA sample details by school, classroom: intervention and comparison groups.

128 students from four classes, as well as their teachers, who were observed as part of the qualitative data collection (76 of these were also part of the first subsample).

Prior to data collection, Institutional Review Board approvals were obtained from the University and from the Ministry of Education’s Chief Scientist Office (no. 11236). Parental approvals were obtained on a yearly basis. For further details see Supplementary Information, part 2: Details of the study sample.

Data collection and analysis

Quantitative data collection: The Interdisciplinary Competences Assessment (ICA)

Building upon the interdisciplinary competences scheme outlined earlier, we developed an assignment for students that featured pairs of texts loosely linked by an unnamed common theme (e.g., “gold,” “love,” “women’s rights”) but diverging in context, style, and disciplinary origin (e.g., one text associated with history and the other with Bible studies). The texts, selected in a process that involved expert assessment and a student focus-group, were previously unseen by both students and teachers in the study. Six essay questions were designed to evaluate students’ performance of various actions, using the interdisciplinary competences schema outlined above. provides an overview of the questions, their hypothesized underlying competences, sample responses, and a scoring rubric on a 0–3 scale, intended to gauge the proficiency of each competency. The scoring rubric is akin to ones used in previous knowledge integration studies, with adaptations to fit the context of humanities (Linn & Eylon, Citation2011). Inter-rater reliability, calculated using Krippendorff’s Alpha (Hayes & Krippendorff, Citation2007), ranged from .74 to .94 for each question. For full details see Supplementary Information, part 3: ICA measure development, administration and scoring.

Table 2. The Interdisciplinary Competences Assessment (ICA): questions, skills, scoring rubric and examples.

Students completed one version of the assignments before IL-Humanities units and another after units were taught. The time-lag between the pre- and post-intervention assessments ranged between a minimum of 4 months and 2 weeks to a maximum of 6 months and 3 weeks. For Further details, see Supplementary Information part 4: Project timeline.

Quantitative data analysis

A principal-components analysis with varimax rotation of the pretest scores suggested a single factor solution that explained 40.1% of the variance, on which all six questions loaded between .454 and .733. A single factor solution explaining 43.1% of the variance was also found for posttest scores, with questions loading between .544 and .713. We cautiously interpret this to allow for the possibility of a single construct behind all questions—interdisciplinary competences—but further research is needed to corroborate this.

Reliability levels of the full 6-item measure in both pretest (n = 375) and posttest (n = 418) were satisfactory. Cronbach’s alpha scores were 0.70 in the pretest and 0.74 in the posttest. Aggregated scores of interdisciplinary competences (calculated by summing all 6 sub-scores) for respondents who completed all 6 questions on both timepoints (n = 297) were significantly correlated at r = .492, p < .001 despite the significant time lag between administrations, indicating consistency.

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests were conducted to compare the level of each type of competency between the pretest and the posttest and between the intervention and comparison groups. To test for distribution normality, in line with sample size (>50), the distribution histogram and Q-Q plot were examined, and both suggested that the data’s distribution closely approximates normality. Skewness (−0.17) and Kurtosis (0.79) were acceptable as well. The aggregated scores on overall competences on a 0–18 scale ranged from 0–16. The choice to employ the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test for analyzing changes in final scores was made to ensure methodological consistency across our analyses, particularly for ordinal variables. Note that at large sample sizes, the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test yields results that are broadly analogous to those obtained via the t-test.

Qualitative data collection

During the implementation of the units, ethnographic data was collected from two schools. One researcher was assigned to Tikvah middle school as a participant-observer, and two researchers were assigned to Tel Nof secondary school (pseudonyms). These schools were selected for the qualitative study based on the principle of maximum variation (Patton, Citation2015, pp. 428–29). Located in Israel’s northern region, Tel Nof is large and well established, with some 1800 students in grades 7–12, and serves a wealthy population. The principal had first launched an IL-Humanities curriculum six years before our study. Tikvah is a recently established small school located in a lower SES city in Israel’s central district. In 2022, it numbered about 300 students, grades 7–9. The core values at Tikvah were community and identity, and it comprised mainly Mizrachi students (i.e., Jews hailing from a North African and Middle Eastern heritage).

We collaborated with four teachers (all names are anonymized to preserve participants’ privacy): David and Anna at Tel Nof, and Ruth and Lia at Tikvah. David had become a civics teacher, after a long military career, six years before our study. He was a seventh-grade homeroom teacher and was well-regarded by his students. Anna, the director of Tel Nof’s interdisciplinary humanities curriculum, was highly experienced. Several years after starting out as a physical education teacher, she shifted to teaching literature, and ultimately gained the confidence of the school head, who promoted her to her current role. Ruth was an energetic founding member of Tikvah in her late twenties and was in the final stages of completing her master’s degree in the humanities. Lia was a first-year homeroom teacher at Tikvah, who perceived herself as having been involuntarily assigned to teach an interdisciplinary unit, despite preferring to teach history within a disciplinary framework.

As ethnographers, we forged meaningful relationships with teachers and principals, and in general immersed ourselves into the social fabric of the schools as much as possible over the course of the school year. We observed and transcribed video and/or audio recordings of seventeen lessons lasting between 45–90 minutes each, conducted six hour-long semi-structured interviews with the teachers, collected students’ end-of-year assignments from two classes, and collected field notes (see ).

Table 3. Qualitative data corpus.

Qualitative data analysis

The overall aim of this qualitative analysis is to understand how teachers’ and students’ discourse mediated interdisciplinary learning. Our analysis began with a segmentation of the data, as we divided each transcript into episodes. Each episode comprised 3–15-minute segments of speech surrounding a single theme or topic (Huguet et al., Citation2017). For each episode, we noted participants, topic, and activity (e.g., explaining, giving instructions, etc.). We then conducted a second round of coding to identify the relationship between each episode and knowledge building discourse (codes included perspective-taking, integrative reasoning and Both/And reasoning, which involves considering multiple perspectives to be valid simultaneously, see Novis-Deutsch, Citation2018) and identity work (codes included references to self, values, and culture). These codes were based on themes that teachers and principals whom we previously interviewed had tied to interdisciplinary learning (Cohen et al., Citation2024). Following these two initial rounds of coding, we employed discourse analysis tools to conduct a turn-by-turn analysis of all 143 episodes (Gee, Citation2014; Wortham & Reyes, Citation2015).

These steps led us to (1) distinguish more clearly between knowledge building and identity work; and to (2) identify a large degree of variation in how each of the participating teachers approached the challenge of interdisciplinary teaching and learning. David and Lia put a greater emphasis on knowledge building discourse, and invited students to engage in inquiry projects aimed at advancing their understanding of out-in-the-world phenomena: religious leadership and the Renaissance period. David provided scaffolding and mentorship that mediated IL-Humanities very effectively, leading to novel insights and understanding among students. In contrast, Lia’s students were typically left confused about how an interdisciplinary lens might advance their understanding of the phenomena under investigation.

Ruth and Anna leaned more toward the view that IL-Humanities offered an opportunity to look inwards, so that students might engage in self-authorship. However, here too we found a large degree of variation. Ruth was often effective in engaging students in an open and candid identity discourse, whereas Anna missed many opportunities to do so. Our turn-by-turn analysis also revealed that (3) although one facet of IL-Humanities (knowledge building or identity work) was typically foregrounded, the other was easily discernable.

Upon completing the initial two rounds of coding and the analysis of all episodes that followed, we purposefully selected two episodes—one for each process—to illustrate our findings. These episodes were selected based on two criteria. First, our ethnographic data, including fieldnotes, observations, and interviews, indicated that they were representative of each respective teacher’s approach to IL-Humanities (e.g., the first episode, which was drawn from David’s class, was representative of his approach). Second, we purposefully selected episodes that we found to be especially telling with regards to IL-Humanities (i.e., theoretically rich; see Mitchell, Citation1984).

The discourse analysis followed the methodology outlined by Wortham and Reyes (Citation2015). We chose this method because it is especially suitable for interpreting learning processes that link the content of classroom discourse (i.e., IL-Humanities) with the learning processes that classroom discourse mediates (i.e., knowledge building and identity work). According to Wortham and Reyes (Citation2015), the goal of discourse analysis is to identify and characterize social actions that interlocutors are performing in the present, here-and-now, by talking about certain events—real or hypothetical; past, present or future—in certain ways. To accomplish this, an analyst begins by mapping the narrated events (“what is being talked about;” Wortham & Reyes, Citation2015, p. 3). These can include characters, roles, traits, courses of action, etc. Next, the analyst identifies indexical signs, which are signs that have a particular meaning within a given context, and seeks out the ones that seem especially meaningful. Meaningful indexicals often include—but are not limited to—deictics (words that can only be understood in light of their context, e.g., “me,” “they,” “yesterday,” or “over there”), and reported speech (e.g., “I told you so”). Finally, in light of their interpretation of the narrated events, analysts can also provide a rich explanation of the social action unfolding in the narrating event, here-and-now, and can interpret how the narrative positions interlocutors vis-à-vis one another. In connecting the narrated and narrating events, we took particular note of any participant examples offered by narrating participants. Participant examples are sections of narrated events “in which at least one participant [in the interaction] takes part” (Wortham, Citation1992, p. 5). Wortham (Citation1992) has shown participant examples to be powerful means by which students and teachers engage in identity work in the classroom, by simultaneously discussing narrated and narrating events. Our focus on discourse in general, and participant examples in particular, aimed to shed light on the IL-Humanities processes, addressing our second research question. We also used the Interdisciplinary Competences schema () as a key interpretive lens while conducting the discourse analysis of these episodes.

The trustworthiness of our interpretations was established through deliberate steps designed to ensure credibility, transferability, confirmability, and reflexivity throughout the data analysis process (Korstjens & Moser, Citation2018). Credibility, which refers to the accuracy of qualitative interpretations, was enhanced by implementing several measures, including: (1) prolonged ethnographic engagement with participating teachers and students; (2) persistent analysis procedures that incorporated all previously detailed steps; and (3) triangulation of interpretations from our primary data sources (recorded lessons) by comparing them with additional data sources (fieldnotes, interviews, and lesson plans).

Transferability, a further dimension of trustworthiness, was achieved by providing detailed descriptions in our qualitative “Results” section. This allows readers to determine the applicability of our findings to their known contexts. Confirmability, the third dimension, is the assurance that findings are rooted in the data. We facilitated this through transparent reporting in our “Methodology” and “Results” sections. Lastly, we upheld a reflexive stance by maintaining journals during data collection and analysis, and by hosting weekly meetings throughout the analysis period. In these meetings, we extensively discussed our data and considered “rival explanations” (Yin, Citation2012).

Results

Learning outcomes: Quantitative findings using the ICA

Following the administration of the ICA, we found that students in the intervention group significantly improved their interdisciplinary competences. Improvement in the comparison group was not significant, indicating that developmental maturation cannot fully explain these results. presents the medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) of each of the six types of interdisciplinary competences that the ICA assignment measured before and after the IL unit, as well as the results of Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests between pretest and posttest scores, for the intervention and comparison groups separately.

Table 4. Results of Wilcoxon signed-rank test for the change in students’ interdisciplinary competences assessment (ICA) scores.

As indicates, students’ interdisciplinary competency levels were low overall, both pre-intervention and post-intervention. They were highest for the two comprehension questions, intermediate for the integration questions, and lowest for the synthesis questions.

For the intervention group, all posttest scores (aggregated 6 items) showed a significant improvement from the pretest to the posttest with a moderate-to-large Rank Biserial Correlation effect sizes, suggesting that students enhanced their interdisciplinary competences significantly, following IL. For the comparison group, the change between pretest and posttest scores was not significant, indicating no substantial improvement.

The same pattern appeared at item-level: Each of the six actions significantly improved (with small effect sizes) in the intervention group but none improved significantly in the comparison group. No other systematic differences were found between the comparison and intervention groups.

To statistically assess differences in changes between the intervention and control groups, a mixed-effects model framework was employed accommodating the nested structure of the data (measurements within individuals and individuals within classrooms). Given the potential non-normality of the response variable and to ensure robustness to violations of ANOVA assumptions, the Aligned Rank Transform (ART) was applied to the score variable. Significant interaction effects between time (pre vs. post) and group were observed for the divergent synthesis question, F(1, 460.7) = 5.4, p = .020, and for overall interdisciplinary competency, F(1, 401.5) = 7.4, p = .007. These results suggest that, compared to control participants, those in the intervention group exhibited greater gains in both divergent synthesis and overall interdisciplinary competency.

Learning processes: Qualitative findings from the discourse analysis

An overview of the qualitative findings

In what follows, we shall delve more deeply into two episodes that shed light on the moment-to-moment classroom discourse that mediated cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work. The first episode sheds light on the process of methodological cross-application (a form of knowledge building) and the second episode features reflective synthesis (a form of identity work; see ). These two examples were purposefully selected because we found them to be particularly telling, but they were not exceptional. The first episode was representative of David’s approach to IL-Humanities, whereas the second episode was representative of Ruth’s approach.

Cross-disciplinary knowledge building

Tel Nof’s 7th grade IL-Humanities teachers jointly designed an interdisciplinary unit on religious leadership that combined history, literature, and Bible studies. David saw this IL-Humanities unit as a means to hone students’ cross-disciplinary knowledge building skills. Indeed, in an interview we conducted with him, he shared his belief that cross-disciplinary knowledge building competences would enable students to become independent learners, attain deeper understandings, and grasp complex phenomena. In the weeks that we spent observing his lessons, David divided his class into groups of 4–5 students and required each group to conduct an independent inquiry project into the notion of religious leadership. He held meetings with each of the groups in his office to touch base and provide students with constructive feedback. Below is a sequence from one of those meetings, with three female students named Liat, Michal, and Noa (pseudonyms):

To conceptualize the learning process that learners were engaged in here-and-now, our analysis began by mapping the contents of the discussion. This initial mapping led us to distinguish between three focal points in the sequence. The first, in lines 101–2, frames the entire narrated event. Chronologically, these two lines are like brackets that frame the rest of the sequence, which begins with a broad question about the team’s progress: “what about religious leadership?” and ends after the process reported on the rest of the sequence is complete: “we did that too.” What did they do? How did they do it? The answers to these questions can shed light on the cross-disciplinary knowledge building processes we observed.

The second focal point, portrayed in line 107, and then again in 116–7, is the group’s understanding of religious leadership. As the group members discuss their understanding of religious leadership, they differentiate between two phases. Initially, they were stumped: “we weren’t able to understand and get the definition of religious leadership,” line 107; but by the end, they had articulated a sophisticated classification: religious leaders influence individual followers’ faith without resorting to coercion. In other words, their definition addressed three key tensions to any understanding of religion: (1) individual versus communal; (2) internal and spiritual versus publicly accessible and tangible; and (3) internal versus external motivations. Touching on these tensions demonstrates a complex grasp of religion that echoes some influential religious philosophers (e.g., James, Citation1982/1902).

Going from no understanding to such a advanced definition required Liat, Michal, and Noa to engage in cross-disciplinary knowledge building, by utilizing one source that they understood well (politics) to decipher another (religion). According to our schema (see ), this methodological cross-application, which appears in lines 105 and 108–113, constituted an act of integration. As secular adolescents from a well-off community, it was not surprising that at the outset their understanding of politics and political leadership was more advanced than their understanding of religion and religious leadership. For example, in line 113–4, when Michal defined peace as an example of a tangible political goal, Noa suggested that the current Prime Minister wasn’t actually working toward peace at all, because it contradicted his electoral interests. This exchange demonstrated these students’ nuanced understanding of the political sphere and their confidence in discussing political leadership.

Lines 111–3 contain the most direct reference to the act of integration. Michal explains that in contrast to politics, which is about achieving tangible goals in the shared, real, world, religion is about “the person … working towards the goal” by which she alludes to a private and internal realm. The reference to Israel’s Prime Minister in line 114, who is typically unpopular among the population of Tel-Nof, evokes the coercive nature of politics, which the group juxtaposed with religion. In lines 105 and 109, Michal and then Noa articulate the method by which they drew on their knowledge of politics to develop a better understanding of religion: “we realized that political leadership is kind of the opposite of religious leadership.”

The segment ends with a deictic that connects between the contents of the conversation and the interaction unfolding here-and-now, as Noa explains the function of religious leaders by referring to her teacher, David, in the second person, to elaborate on their understanding of the concept: “You help them and like convince them about something you believe in, it’s not […] like you have too much control over them, you get them to believe in something that you believe is really true.” Although she is ostensibly still talking about the narrated events, Noa’s use of this deictic drew the interlocutor’s attention back to the present, signaling that the discussion of their inquiry into religious leadership was complete and that the question posed in line 101 had been answered by means of a methodological cross application ().

Transdisciplinary identity work

We hypothesized that the interdisciplinary humanities learning environment would mediate learning on themes that were relevant to students’ everyday lives. One theme that emerged repeatedly in the lessons we observed and the interviews we conducted was the notion of identity, which we understood simultaneously as a reference to recognizable social categories such as gender, ethnicity, faith, and nationality (Gee, Citation2000) and as a process of self-narration (McAdams & McLean, Citation2013).

Some of the teachers designed learning environments with the explicit aim of mediating acts of synthesis, including reflections on identity and self, and creative expression. Ruth was especially drawn to explorations of identity, and particularly to the ways in which the tension between Ashkenazi (European Jews) and Mizrachi (North African and Middle Eastern Jews) identities shaped public discourse in Israel (Ruth herself came from a mixed ethnic background). Because most of Ruth’s students at Tikvah were Mizrachi, she saw her humanities lessons as an opportunity to celebrate their marginalized heritage. This was accomplished through an extended inquiry project into students’ family histories. At one point in the inquiry the students took advantage of an online tool made available by the diaspora museum to investigate their surnames. The following segment offers a glimpse into one case of transdisciplinary identity work. According to Ruth’s lesson plan leading up to the following interaction, students were supposed to investigate their surnames. However, when Ruth brought up the topic of surnames, a student named Amit raised a question surrounding middle names, and the following discussion ensued:

This sequence combines two types of narrated events (“what is being talked about,” see “Methods” section), which together constituted an act of synthesis () that was accomplished in the narrating event, here-and-now. The first topic is the custom of giving middle names (lines 202–5, 207, 210, 213, 218, 223), and the second is a series of examples in which learners tell stories about people they know as a means of elaboration and clarification (206, 209, 212, 214, 217, 219–22, 224–226). The topic of middle names is broached from several directions: who gives them, under what circumstances, and for what reason. For example, the teacher suggests that some people believe that a middle name might provide strength in cases of severe illness (207), or that it can serve to commemorate someone who has passed away (218).

The second set of narrated events includes a series of five examples (). A closer look at the deictics and reported speech in each of these examples is revealing. What is particularly striking is how the identities of the name givers/users, and the people being named within the examples move increasingly closer from a far-off then-and-there to an immediate here-and-now. The final three examples are participant examples, in which class members feature within the example itself, enabling students to simultaneously index narrating and narrated events, and thus engage in meaningful identity work by drawing a connection between them. In the first example, Ruth recounts the tale of a relative who fell ill at a very young age and was given a new middle name “to strengthen him” (206). The relative is apparently distant, and the identity of those giving/using the name remains anonymous. In the second example, a student named Ella tells a similar story—an infant who fell ill was given a second name in the hope of curing her. But in this case, the identity of the name giver is revealed (“The Rabbi,” line 209), as is Ella’s relationship with the infant (“my cousin”). Rena’s third example is a participant example: she and other family members call her brother by his middle name because it is more modern than his first name, which is after a grandfather (212). In the fourth example, Amit brings the topic of conversation to bear upon himself, sharing that his own middle name was given in memory of his late grandfather (217). And finally, the sequence culminates with a fifth participant example, as a student named Itai reveals that Amit had indeed asked his classmates to call him by his middle name, Jacob (225).

Table 5. Five examples about middle names.

The final two participant examples offer a rich illustration of transdisciplinary identity work within an IL-Humanities lesson. Amit seized on the topic of names, which afforded him the opportunity to engage in an act of synthesis as he reflected on the nature of his relationship with his family heritage, and identified with his late grandfather, who was also his namesake. Ruth’s choice to divert her lesson plan from surnames to middle names was clearly a deliberate one, as was her decision to allow for so many examples, while calling on the students to hear each other out (e.g., line 216). These strategies enabled meaningful identity work that deepened the students’ connections with one another in addition to strengthening their family ties. Indeed, the final participant example brought the conversation round full circle. Initially, the discussion began with Ruth’s story of a nameless distant relative who was named, then-and-there, by an anonymous “them.” By the end, in Itai’s participant example, both name giver and name holder were participants in the narrating event (Itai and Amit).

Discussion

This study examined interdisciplinary learning in K-12 humanities units by asking about changes in learner competences and by exploring how such learning occurred in classrooms. We now turn to an integrative discussion of our answers to these questions.

Our conceptual and empirical reviews suggested that IL-Humanities may promote two types of learning: cross-disciplinary knowledge building, which is rarely the goal of single subject learning; and transdisciplinary identity building, which can readily be brought to the fore in interdisciplinary contexts, by focusing on immersion, embeddedness and reflectiveness.

To gain a sense of how effective IL-Humanities is in promoting these two processes of interdisciplinary learning, we developed the novel Interdisciplinary Competences Assessment (ICA). Our findings offered preliminary affirmation of the reliability of the ICA for assessing IL-Humanities outcomes: the reliability levels of the measure were satisfactory, the coding scheme lent itself to satisfactory Inter-rater reliability, pre and post scores on the assignments were highly positively correlated indicating consistency, data distribution approximated normality, the range of scores was broad, and the factor analysis indicated a single construct behind all the questions, which we conceptualized as interdisciplinary competency. While these findings indicate a satisfactory level of reliability, there remains work to be done to enhance the psychometric robustness of the ICA. Future research could explore the inclusion of additional items to better capture the multidimensional nature of interdisciplinary competences, potentially leading to a multifactor solution that could explain a larger portion of the variance, and further investigation into the discriminant and convergent validity of the measure could test whether the tool accurately captures the construct it is intended to assess, distinct from related disciplinary competences.

Building on the satisfactory psychometric properties of the measure, we tested middle school students before and after engaging in IL-Humanities units and found that interdisciplinary competences were amenable to improvement following such learning, in contrast to the comparison group, where improvements were not statistically significant. This indicates that when students learn in interdisciplinary environments, their abilities to comprehend, integrate and synthesize sources across different subjects and disciplines improve. However, the small magnitude of change, although statistically significant, indicates that further pedagogical development is needed to help students enhance these competences, and to help teachers mediate them.

We also asked how learners engage in cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work. Coding the class discourses enabled us to ascertain that both major categories (knowledge building and identity work) were reflected in real classroom dialogue and were in fact represented in nearly equal proportions, while discourse analysis revealed some of the ways in which these learning processes unfolded.

A close reading of two telling episodes (Mitchell, Citation1984) offered insights into the learning processes that could explain these advances in interdisciplinary competences: The removal of disciplinary boundaries for students in the case of David’s class meant that students could draw on their understanding of one subject domain (in this case, the political realm) to advance their understanding of another (in this case, of religion). In terms of the Interdisciplinary Competences schema, this is an example of how “Methodological cross-application” (part of “Integration;” see ) can be enacted in the humanities. The case of Ruth and her students offered a glimpse into the inner workings of transdisciplinary identity work, which was afforded by several elements in the learning environment, including the teacher’s willingness to diverge from the original lesson plan, classroom norms that included openness and respect, and the empathy of both teacher and students toward participant examples, which were personal and even intimate. This is an example of how “Reflective synthesis: Connecting to self/identity” (part of the “Synthesis” component; see ) can be performed in interdisciplinary humanities environments.

These findings can offer directions for future design-based research studies related to the question of how IL-Humanities can be applied successfully in classrooms. We tentatively suggest that such research could begin by encouraging teachers to facilitate identity work in IL-Humanities by allowing students to shift the lesson’s focus, so that it revolves around issues relevant to them across domains of knowledge, and by making space for personal stories and for self-authoring in the context of learning communities. Future research could then use the ICA to explore how these design principles affect the students’ interdisciplinary learning competences.

The quantitative and qualitative findings do not triangulate a single question; instead, they commence from a common conceptual framework, employed for complementary objectives. The quantitative factor analysis indicates that cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work could be part of a single construct which we termed “interdisciplinary competences.” Conversely, the qualitative findings offer data on the appearance and frequency of both processes in a classroom setting (rather than in a predesigned assignment) and offer insights into how these competences can be promoted.

Although the interdisciplinary learning that we observed included a significant element of cross-disciplinary knowledge integration, a caveat is in order: The kind of cross-disciplinary knowledge integration that we observed in the classrooms (in the episode of David and his students which we presented, and in other analyzed episodes) tended to revolve around exploring topics or questions from different perspectives. It was rarely of the kind that is described in theoretical models of interdisciplinarity (e.g., Boix Mansilla et al., Citation2000; Spelt et al., Citation2009) or in empirical studies on IL in higher education settings (e.g., Schijf et al., Citation2023). Class discussions did not often focus on what we termed “comprehension” competences (). In fact, learning was rarely concerned with disciplinary distinctions, such as how a historian’s thought process differs from that of a philosopher. Perhaps disciplinary categories were simply not salient enough to these students; their limited familiarity with the characteristics of various disciplines hindered meaningful engagement in this aspect.

However, interdisciplinary learning in K-12 settings need not be of a meta-disciplinary nature, that is, about disciplines and how they interact. Other challenges relating to knowledge building loom large for students today, who face an overload of information, fake news and post-truth (Chinn et al., Citation2021). To successfully navigate this knowledge-scape, students need to be able to make sound knowledge connections across subjects. Our findings show that they can improve the competences required to accomplish this (to a certain degree at least) and shed light on some of the specific ways in which it plays out.

Contemporary life also poses new challenges to identity and belonging, as students grapple with the ever-growing venues for self-realization and participation in local and global communities, online and offline. Simultaneously, identity politics have been fueling an increasingly radical political discourse. Hitherto, identity discourse tended to be considered out of bounds in public schools that were ostensibly apolitical. Yet, to counter the challenges posed by this new reality, schools today may need to allocate more space to mindful identity work to sustain liberalism and value pluralism (Alexander, Citation2015; Novis-Deutsch, Citation2018). By mediating meaningful identity work and cultivating students’ competences to engage with it fruitfully, IL-Humanities can play a part in realizing this goal too.

Limitations and future directions for study

Our findings beg caution for several reasons. IL-Humanities is a large field, and as with any specific study, our context-dependent findings may be difficult to replicate. This study was additionally limited by the scope and short duration of the class interventions, in part due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the promising aspects of this study was a focus on competences that undergird IL-Humanities, especially considering recent work on measuring interdisciplinary understanding in higher education (Schijf et al., Citation2023). Due to the preliminary nature of the ICA measure, further research is recommended to corroborate these findings. Such work includes testing the measure using different pairs of texts, different subjects in the humanities (e.g., literature and philosophy), and different contexts (e.g., countries, age of students). This could bolster the internal validity of the measure and enhance its applicability in diverse educational settings. Further testing of the relationship between the two processes of interdisciplinary learning—cross-disciplinary knowledge building and transdisciplinary identity work—is warranted as well. We took preliminary steps in this direction by coding class interactions using the learning actions suggested by our conceptual model, but further work is needed. Future studies could also link the schema of interdisciplinary competences with designs for learning environments, thereby enabling more robust assertions regarding the ICA’s implications for learning. Finally, Future studies could examine the impact of different pedagogies within the broad range of what we termed “interdisciplinary” learning on interdisciplinary competences.

As we noted in the “Literature Review” section, STEM research, which covers another form of interdisciplinary learning, is far more developed, cohesive, and theoretically advanced than research on IL-Humanities. It is worth considering some of the steps taken in the STEM field, as inspiration. STEM researchers developed a large body of work on knowledge integration (Linn & Eylon, Citation2011) including a Design Principles database (Kali, Citation2006). We envision a similar process in IL-Humanities, perhaps gradually leading to a third body of research where the two sets of findings and learning principles can be integrated.

Conclusion

The humanities have a major role to serve in any society, but especially in those experiencing fragmentation, threats to their democratic infrastructure, and deficiency of pluralism. If a humanistic approach to public discourse offers a chance of repairing societal breaches, then a good place to begin is in defining goals for humanities education. Interdisciplinary humanities education can help learning communities focus on the big questions of humanity, by allowing learners to integrate the insights attained in various disciplines such as philosophy, literature and history, about the human condition. It also has the capability, as this study demonstrates, to promote an identity-centered discourse about who we are as a society and who we want to become. One of the postulates of the relations-based ecological perspective on knowledge (Markauskaite, et al., Citation2023) is that “in learning, not only knowledge but also the whole person is transformed. Learning is seen as a process of constant becoming, in which knowledge is continuously (re)constructed based on information available in the environment” (p. 35). This study suggests that interdisciplinary learning contexts in the humanities, may be especially suitable for both mediating and studying such co-constitutive knowledge-building and identity-developing processes.

We noted that our research team began this project challenged by our own disciplinary differences. As our work progressed, we identified three strategies that enabled us to overcome these differences: (1) articulating a shared commitment (in our case, to a pluralistic, liberal democratic society), (2) identifying a shared goal (furthering humanities education in preparing citizens for such a society) and (3) a willingness to engage in open dialogue and in learning from each other. This shared positionality may be key to other successful IL-Humanities programs, and our findings support our recommendation to develop IL-Humanities that center on integration, dialogue and reflection and help learners develop the competences necessary to engage in such activities. This can allow learners to weave together the complex historical, literary, artistic, ideational, and social strands of the humanities, thus enhancing their knowledge and their identities.

Author’s contribution

Nurit Novis-Deutsch: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing (original draft, review and editing) visualization, supervision. Etan Cohen: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing (original draft, review and editing). Hanan A. Alexander: conceptualization, supervision, review, funding acquisition. Liat Rahamian: Project administration, Uri Gavish, Ofir Glick, Oren Yehi-Shalom, Gad Marcus and Ayelet Mann: Investigation, data curation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31 KB)Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the financial and substantive support offered by the Bureau of the Chief Scientist of the Education Ministry and especially of Dr. Odette Sela, Chief Scientist. We gratefully acknowledge the collaboration and support of the Be’eri Program at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem for managing the PD programs, and especially the support of Alon Mor, head of the Be’eri Program, and of Dr. Noga Baror who managed the PD courses. We are grateful for the advice and input of Prof. Anat Zohar, Prof. Sarit Barzilai, Dr. Racheli Levin Peled and Prof. Adam Lefstein. We cannot thank editor Prof. Lina Markauskaite enough for her support and advice during the publication process. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose thoughtful and wise comments helped us improve the manuscript. We are deeply appreciative of the hard work of research assistants and data analysts Nofar Mizrachi, Tamar Zohar, Gili Bublil, Einav Levi, Rana Swaid; Brian Oren, and Maya Elazar. Finally, we extend our grateful thanks to all the principals, teachers, and students who participated wholeheartedly in this study.

Disclosure statement

We confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and that no financial supporters of this work influenced its outcome. All the sources of funding for the work described in this publication are acknowledged: the Israel Ministry of Education and the Center for Jewish Education, University of Haifa.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2024.2346915

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexander, H. A. (2015). Reimagining liberal education: Affiliation and inquiry in democratic schooling. Bloomsbury.

- Allen, C. D., & Eisenhart, M. (2017). Fighting for desired versions of a future self: How young women negotiated STEM-related identities in the discursive landscape of educational opportunity. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 26(3), 407–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2017.1294985

- Apostel, L. (1972). Interdisciplinarity Problems of Teaching and Research in universities. OECD Publications.

- Applebee, A. N., Adler, M., & Flihan, S. (2007). Interdisciplinary curricula in middle and high school classrooms: Case studies of approaches to curriculum and instruction. American Educational Research Journal, 44(4), 1002–1039. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207308219

- Araújo, U., & Arantes, V. (2009). The ethics and citizenship program: A Brazilian experience in moral education. Journal of Moral Education, 38(4), 489–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240903321956

- Barr, D. J., Boulay, B., Selman, R. L., Mccormick, R., Lowenstein, E., Gamse, B., Fine, M., Leonard, M. B., Associates, A., Lowenstein, E., Gamse, B., & Leonard, M. B. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of professional development for interdisciplinary civic education: Impacts on humanities teachers and their students. Teachers College Record, 117(2), 52. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811511700202

- Barzilai, S., Zohar, A. R., & Mor-Hagani, S. (2018). Promoting integration of multiple texts: A review of instructional approaches and practices. Educational Psychology Review, 30(3), 973–999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-018-9436-8

- Batdi, V., Talan, T., & Semerci, C. (2019). Meta-analytic and meta-thematic analysis of STEM education. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 7(4), 382–399.

- Beames, S., & Ross, H. (2010). Journeys outside the classroom. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 10(2), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2010.505708

- Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1969). The social construction of reality. Penguin.

- Birsa, E. (2018). Teaching strategies and the holistic acquisition of knowledge of the visual arts. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal, 8(3), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.26529/cepsj.39

- Boix-Mansilla, V. (2017). Interdisciplinary learning: A cognitive–epistemological foundation. In R. Frodeman, J. T. Klein, & R. Pacheco (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity (2nd ed., pp. 261–275). Oxford University Press.

- Boix-Mansilla, V., Duraisingh, E. D., Wolfe, C. R., & Haynes, C. (2009). Targeted assessment rubric: An empirically grounded rubric for interdisciplinary writing. The Journal of Higher Education, 80(3), 334–353. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.0.0044

- Boix Mansilla, V., Miller, W. C., & Gardner, H. (2000). On disciplinary lenses and inter-disciplinary work. In S. Wineburg & P. Grossman (Eds.), Interdisciplinary curriculum: Challenges to implementation (pp. 17–38). Teachers College Press.

- Bråten, I., Braasch, J. L., & Salmerón, L. (2020). Reading multiple and non-traditional texts: New opportunities and new challenges. In E. B. Moje, P. P. Afflerbach, P. Enciso, N. K. Lesaux, & M. Kwok (Eds.), Handbook of Reading Research (Vol. V, pp. 79–98). Routledge.

- Britt, M. A., & Rouet, J. F. (2012). Learning with multiple documents: Component skills and their acquisition. In J. R. Kirby & M. J. Lawson (Eds.), Enhancing the quality of learning: Dispositions, instruction, and learning processes (pp. 276–314). Cambridge University Press.