ABSTRACT

Intergenerational trauma research typically focuses on parent survivors. No specific guidelines are available for conducting research with parent survivors despite potentially unique risks. To investigate research safety with parent survivors, we conducted an online survey of 38 researchers regarding experiences of parent survivors in their research, precautions taken, ethical review experiences, and researchers’ mental health during the project(s). Most researchers felt that parent survivors are a unique population that require extra support. However, the response rate was low. Findings show the need for specific research guidelines informed by parent survivors’ lived experiences, and to support researchers against vicarious traumatic stress.

Approximately one in three adults has reported being abused or neglected by a caregiver during their childhood (i.e., they have experienced child maltreatment), though the exact prevalence differs by maltreatment type, gender, and country (Moody et al., Citation2018; Stoltenborgh et al., Citation2015). A history of child maltreatment significantly increases the risk for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and substance use disorders later in life (Carr et al., Citation2020; Greene et al., Citation2020; Toth & Manly, Citation2019). The consequences of child maltreatment can create a self-perpetuating cycle, known as intergenerational trauma, both directly (e.g., an abused parent abusing their own children) and indirectly (e.g., higher rates of mental illness observed in children of parent survivors) (McDonnell & Valentino, Citation2016).

To intervene in the cycle of intergenerational trauma, substantial literature has focused on understanding the experiences of “parent survivors” (i.e., parents who were abused or neglected as children), in particular, parents of infants (pregnancy to their first 12 months is seen as the most critical time for outcomes; Bowlby, Citation1988). In the context of intergenerational trauma literature, a “parent” is defined as one of the primary caregivers of a child (not necessarily biologically related) to whom the child forms a strong attachment as an infant (Bowlby, Citation1969). Becoming a parent provides an opportunity to either heal from or continue intergenerational trauma (Chamberlain et al., Citation2019), and is therefore an optimal time for research and intervention. The form of research with parent survivors has ranged from qualitative interviews to self-report surveys and observational studies, with the aim of better understanding how the consequences of trauma are manifested in parenthood and transferred, in some cases, to the wellbeing of survivor’s children (Greene et al., Citation2020). Parent survivors may face particular challenges during research participation that are not as common in other trauma populations, however, it appears that there are not widely available guidelines or literature to account for their specific context as research participants.

For trauma survivors in general, participating in research that focuses on their traumatic experiences has been reported to rarely cause significant lasting distress, and potentially be an empowering experience (Dragiewicz et al., Citation2023; Jaffe et al., Citation2015; Legerski & Bunnell, Citation2010). However, the effects of research participation have not been studied specifically in relation to parent survivors of child maltreatment, who exist in a particularly complicated context and are at an increased risk for psychological distress due to a combination of innate stressors involved in the transition to parenthood, and stressors particular to parent survivors (Chamberlain et al., Citation2019).

Common stressors involved in becoming a parent, such as parental fatigue, financial stress, relationship strain, and reduced leisure time, often cause the transition to parenthood to be one of the most challenging periods in an individual’s life (Trub et al., Citation2018). This can be further complicated by guilt and shame due to societal pressures to fit within unrealistic standards of being the “perfect” parent (Eaton et al., Citation2016; Liss et al., Citation2013). Research has observed a general increase in the prevalence of depression and anxiety in parents during the postnatal period (Smythe et al., Citation2022).

Stress levels during the transition to parenthood can be even more elevated in parent survivors of child maltreatment, due to the interaction between consequences of trauma with parenting stressors (e.g., the parent’s already elevated fear response being more easily triggered by their child’s distress) (Chamberlain et al., Citation2019). In addition to the increased risks for adverse outcomes experienced by trauma survivors (e.g., physical or mental illness, difficulty with psychosocial adaptation; Carr et al., Citation2020), a recent systematic review by Greene et al. (Citation2020) found that parent survivors of child maltreatment are also at an increased risk for perpetuating child maltreatment (though this happens in the minority of cases; Yang et al., Citation2018), having maladaptive dynamics with their children (e.g., role reversal, rejection, withdrawal), lower levels of positive parenting behaviors, and at an increased risk of experiencing interpersonal violence. Further, some survivors of child maltreatment have been found to experience long-lasting negative appraisals of their experience, such as shame and alienation, which in turn have been associated with higher rates of externalizing and internalizing symptoms in their children (Fenerci & DePrince, Citation2018). The interaction between consequences of child maltreatment with the innate stressors related to becoming a parent indicate that parent survivors are more likely to be vulnerable to psychological distress in general (compared to non-parent trauma populations). Findings regarding experiences and safety precautions in other trauma populations may therefore not fully account for the experiences and risks of parent survivors of child maltreatment as research participants.

An additional factor which distinguishes parent survivors of child maltreatment from other trauma populations is the increased potential for mandatory reporting of child abuse or neglect (Mathews, Citation2022). Mandatory reporting refers to the legal and ethical obligations of certain professions (e.g., healthcare workers, researchers) to report suspected child abuse or neglect to relevant authorities (e.g., police, child welfare department, etc.). The combination of stressors as described above, in the context of research which is investigating parenting experiences and/or abilities after trauma, creates a situation where instances of child abuse or neglect are more likely to be uncovered. Mandatory reporting practices were enacted with the goal of improving child safety and often do so (see review by Schwab-Reese et al., Citation2023), however, the legalities and practicalities of mandatory reporting are highly complex and typically vary by country, state, and/or discipline (Mathews, Citation2022). Unfortunately, due to a complex interplay of historical and structural factors (e.g., historical child removal policies, structural inequality such as racism; Edelman, Citation2023), difficulty in defining child abuse and neglect, and the complexity of individual situations, mandatory reporting and the fear thereof can be a barrier to accurate research, effective intervention, and/or have unintended and unfavorable consequences for participants and their families (Moensted & Day, Citation2020; Schwab-Reese et al., Citation2023). Very few studies have examined the effectiveness of mandatory reporting (Mctavish et al., Citation2017), and fewer have explored the effect of mandatory reporting in the context of research participation (Mathews, Citation2022). The potential for mandatory reporting of child maltreatment in the context of research with parent survivors therefore creates unique risks for participants and their families, and unique responsibilities for the researchers involved, that are unlikely to be as prevalent in non-parent trauma populations.

Despite the complexities of the interaction between trauma and parenting, and the potential for mandatory reporting of child abuse or neglect, there are currently no specific safety guidelines that exist for research with parent survivors of child maltreatment. Essentially all health research is governed by a research entity’s governing body which is typically informed by a national policy (for summary see Mathews, Citation2022). These policies typically employ the principles of likely research benefit needing to outweigh potential risks, careful anticipation of risks, and ways to mitigate or prevent negative consequences to participants due to said risks (Mathews, Citation2022). Some international guidelines exist specifically relating to research with trauma populations and/or children, such as those for ethical research with children (Graham et al., Citation2013), interpersonal violence (World Health Organization, Citation2001), and prevention of vicarious trauma (Sexual Violence Research Initiative, Citation2015). While these are invaluable resources, there is no one guideline that accounts for the interaction between trauma consequences and parenting stress, in the context of the increased likelihood of mandatory reporting, when conducting intergenerational trauma research with parent survivors. For example, the World Health Organization guideline (Putting women first. Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women) prioritizes confidentiality of the mother, without comment on child protection. The guideline for ethical research involving children (Graham et al., Citation2013), does not provide specific guidance on trauma-informed engagement of families. Therefore, the complicated interplay of risk factors for parent survivors and their families warrants an investigation of ethical dilemmas in this specific context and dedicated ethical guidelines.

Direct consultation with parent survivors is, theoretically, the ideal way to understand how to safely conduct research with them. However, when considering the increased potential of risks to parent survivors, it may not be entirely appropriate to conduct direct consultation with this population before obtaining evidence regarding the safest way to do so (e.g., likely risks and useful support mechanisms). Despite a lack of information about how to safely engage parent survivors, it is common for research to target parent survivors as the main population in intergenerational trauma studies (e.g., see meta-analysis of 97 studies with parent survivors by Greene et al., Citation2020). It is therefore imperative that evidence regarding the potentially unique safety needs of parent survivors in research is sought as a priority.

An alternative form of obtaining evidence to support the safety of parent survivors during research is to conduct a survey of researchers who have worked with them. This has been done in other sensitive areas of research, such as suicide (Bailey et al., Citation2020). Investigator surveys in suicide research have been used to identify likely risks that may arise during research, how the ethics process accounted for these, how risks were addressed, and how researchers and ethics committees can best collaborate to ensure the safety of participants while maintaining the fidelity and generalizability of the research (Andriessen et al., Citation2019; Bailey et al., Citation2020). Gathering information about adverse events and ethics processes from investigators in the field of child maltreatment may therefore provide an opportunity to increase the safety of parent survivors in research before we directly engage them.

Growing evidence has suggested that the safety of research participants is also associated with the level of support provided to the researchers themselves. van der Merwe and Hunt (Citation2019) found that if researchers were not adequately supported, they were more likely to experience vicarious traumatic stress symptoms, which in turn compromised their ability to support participants. Vicarious traumatic stress symptoms in researchers can lead to poor boundaries with participants (Trippany et al., Citation2004), biased data collection and/or analysis (e.g., the type of questions asked or not asked in a qualitative interview) (Collins & Long, Citation2003), and high turn-over of staff resulting in loss of human capital and increased organizational costs (Williamson et al., Citation2020). Conversely, researchers engaging in positive coping may buffer against vicarious traumatic stress (Michalopoulos & Aparicio, Citation2012). Studies have suggested that vicarious trauma should be accounted for in ethical applications to mitigate risks for researchers and participants (Berger, Citation2021; Isobel, Citation2021), particularly considering that trauma researchers are likely to have higher levels of empathy (which aids job performance in this area but creates vulnerability to “absorbing” negative emotions), and a personal history of trauma (Alessi & Kahn, Citation2023; Campbell et al., Citation2009). If a researcher is also a parent, potentially with their own history of childhood trauma, they may be even more likely to over-identify with participants in parent survivor research and be at a higher risk for vicarious trauma. When the psychological safety of researchers is taken into consideration, therefore, it is more likely that research will be safer for participants and researchers alike.

In sum, participants in trauma research have generally reported positive experiences, but parent survivors of child maltreatment may represent a unique population that requires extra support due to the particular challenges they are likely to face as parents and potentially as research participants. To our knowledge, no study has explored the experiences and safety requirements of parent survivors as a specific research population, or how best to support researchers to minimize the impact of vicarious traumatic stress when working with parent survivors.

The present study aimed to address these gaps by conducting an exploratory mixed-methods online survey with researchers who have worked with parent survivors of child maltreatment. We sought to gain accounts of researchers’ experiences in relation to three factors that show potential for informing safer research with parent survivors: (1) experiences of participant safety (e.g., safety precautions taken, instances of harm witnessed), (2) experiences of the human research ethics process (e.g., typical concerns for research with parent survivors), and (3) researchers’ experiences of their own mental health when working with parent survivors (e.g., experiences of vicarious traumatic stress).

METHOD

Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional online survey with a mixture of multiple-choice and open-ended questions based on the aforementioned factors. The survey consisted of 22 questions, requiring approximately 10–15 minutes to complete. The survey instrument was purpose-designed for our study, by adapting previous expert surveys (Andriessen et al., Citation2019; Bailey et al., Citation2020). Survey items and format were further developed using the authors’ expertise (in neuropsychology, research with marginalized populations, clinical psychology, and psychiatry) and previous studies (e.g., van der Merwe & Hunt, Citation2019).

Survey questions included multiple-choice questions regarding examples of potential instances of adverse events or harm, experiences with the ethical review process in relation to research with parent survivors, and experiences of mental health of researchers. Open-ended questions enquired about general comments, concerns, or advice in relation to research with parent survivors. This survey was then piloted with three individuals which led to feedback being incorporated. The full survey can be found in supplementary material.

Participants were required to provide consent by selecting “yes” or “no” at the end of the participant information and consent page (the initial page of the online survey). This study received ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Western Australia (approval number 2022/ET000341).

Sampling

Researchers from all nationalities were eligible to participate in the survey if they were aged 18 years or older and had participated in a human research ethics application within the previous three years that involved recruiting parent survivors of child maltreatment. While research indicates that the perinatal period (pregnancy until two years) is most influential for parenting outcomes following child maltreatment (Chamberlain et al., Citation2019), we invited any researcher who had engaged in research with parent survivors (regardless of child age) to participate. This was partly due to the exploratory nature of the study, and to maximize possible recruitment given that other studies who have recruited researchers have reported very low participation rates (e.g., 15–30 participants; Andriessen et al., Citation2019; Bailey et al., Citation2020). Researchers were excluded if they had conducted only secondary research (e.g., systematic review, meta-analysis), as this would not typically involve the opportunity for researchers to witness individual participants’ experiences.

Researchers were identified either through the investigators’ professional networks or a systematic search. The systematic search was conducted using two databases (PsycInfo and PubMed) with variations and synonyms of terms for the concepts: 1) parents and 2) child maltreatment. Results were limited to the previous three years (6th July 2019–6th July 2022), returning 2,304 articles. Studies were screened for relevance (i.e., whether they were an empirical study with parent survivors as participants), and the first and last author of each eligible article was contacted via e-mail. However, saturation appeared to be reached (i.e., no new authors were being identified) after reviewing the first 455 articles (sorted by relevance in the respective database) and screening was ceased. Three-hundred-and-sixty-three researchers were identified through the systematic search. Four researchers did not have a publicly available e-mail address, and four e-mails were not able to be delivered due to the recipients’ server rejecting the message. Fifteen eligible participants were identified through investigators’ professional networks. In total, 370 researchers were invited to participate in the survey. Once eligible participants were identified, they were emailed an invitation to participate in the survey and encouraged to share it with their eligible contacts who fit the inclusion criteria. A reminder e-mail was sent after four weeks.

Data Analysis

Quantitative questions were analyzed descriptively with frequencies, proportions, and ranges (as appropriate). For some multiple-choice questions, participants were able to select as many relevant responses as required, and thus percentages did not always add to 100.

Responses provided in writing (in response to open-ended questions, or as “other” options to multiple-choice questions) were analyzed using conceptual content analysis (Schreier, Citation2012). This analysis involved the primary author (EJ) first reading a section of the qualitative data (three participants’ answers) to inductively create a trial coding frame, until all emerging concepts were accounted for by categories in the coding frame. Data was then segmented into thematic units, and trial coding was independently conducted on a further six participants’ data by two authors (EJ and NW). The interrater reliability for the trial coding frame showed near perfect agreement (κ = 0.86). All data was then independently re-coded by EJ and NW for the main analysis, showing near perfect agreement (κ = 0.82) across the 322 units. All discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two coders.

After the main qualitative analysis, some of the “miscellaneous” subcategories appeared to show one additional theme not accounted for by the original coding frame (“insufficient safety protocol” under “concerns of ethics committees”). The primary author (EJ) reexamined all qualitative data for any further instances. Miscellaneous categories were also reexamined to see if units could be placed appropriately in the other categories, and this occurred in eight instances.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Sample

Thirty-eight researchers participated (see for characteristics of the sample). Since there were no forced-choice questions, the number of participants who answered any given question varied. Two respondents reported conducting most of their research with parent survivors in an upper middle-income country (South Africa) according to the World Bank (Citation2019) criteria, while the remaining 36 researchers conducted most of their research in high-income countries (e.g., the United States, Australia). The average years’ experience in conducting research with parent survivors and number of ethics applications was considerable but with substantial range. Researchers reported a relatively even mixture of study settings, research designs, and analysis types when conducting research with parent survivors. The number of respondents for multiple-choice questions ranged from 33–38 participants, while the number of respondents for open-ended questions ranged from 7–31 participants.

Table 1. Characteristics of the sample.

Overview of Results

Results are reported below by category, with relevant multiple-choice results first presented followed by qualitative content analysis results. Percentages for both multiple-choice and content analysis results are provided out of the total 38 participants (regardless of the number of respondents to a given question). An overview of results to multiple-choice questions is provided in supplementary material.

The results of the qualitative content analysis revealed five main categories: (1) risk of adverse events or harm to parent survivors, (2) experiences of parent survivors in research, (3) concerns of ethics committees, (4) researchers’ perceptions of the ethics process, and (5) mental health support for researchers. Qualitative content analysis results are summarized in (for a more comprehensive version of the table, including code definitions, see supplementary material).

Table 2. Qualitative content analysis coding frame and response rates.

In some instances, the response rates for the same “answer” varied between multiple-choice versus qualitative content analysis findings due to differing number of respondents for multiple-choice versus open-ended questions.

Risk of Adverse Events or Harm to Parent Survivors

Most researchers (65.8%; n = 25) believed that extra caution is needed when conducting research with parent survivors, compared to trauma survivors in general. Ten researchers (26.3%) felt that extra precautions were not necessary. Of the three researchers who selected “other” (7.9%), two researchers suggested extra precautions are not needed when working with parent survivors compared to trauma survivors in general, while the third researcher indicated that extra precautions are needed. Most researchers therefore felt that parent survivors are a unique trauma population who require extra support.

Most researchers reported in multiple-choice responses that they took extra precautions in research with parent survivors to avoid psychological harm (n = 32; 84.2%). The most common of these was survey format (e.g., online and anonymous; n = 20; 52.6%), followed by having a mental health professional on-site (n = 18; 47.4%). Common responses to indications of harm were providing information for psychological services (n = 19; 50%), individual follow-up with participants (n = 18; 47.4%), and/or facilitating a referral to a psychological service (n = 12; 31.6%).

Through qualitative content analysis, two categories emerged regarding steps taken to mitigate psychological harm to parent survivors: preventative measures (n = 27; 71.1%) and reactive measures (n = 9; 23.7%). The most common preventative measures were appropriate staffing (e.g., in qualifications and experience; n = 13; 34.2%), providing mental health resources (n = 13; 34.2%), and study design (e.g., preempting distressing components and planning supports accordingly, n = 12; 31.6%). Regarding appropriate staffing, one participant shared an approach for improving safety of parent survivors as “Working with agencies who support parent survivors to discuss process and support needs” (Participant #19). Specifically, it was recommended that “having mandated reporting training for all study staff so that the boundaries of that step are understood in a way that can benefit the interests of the child (rather than being a tick-box exercise)” (Participant #30). The most common reactive measures were follow-up by the research team or representative (n = 4; 10.5%) and referral to appropriate services (n = 3; 7.9%). These referrals included “mandatory referral to child protection services and to the police” (Participant #14).

The two researchers who elaborated on their view that additional precautions were not necessary for research with trauma survivors described their reasons as “for most who experienced the above ‘adverse or harmful’ things these are not adverse effects of the study, but of the trauma and they exist independently of the study” (Participant #3), and “I think the same precautions that are appropriate for trauma survivors or for parents are suitable. In other words, thinking about vicarious trauma and also offering skills and direct referrals for safe parenting” (Participant #30).

Experiences of Parent Survivors in Research

Multiple-choice responses showed that more than half of researchers (n = 22; 57.9%) experienced potential indicators of adverse events or harm in parent survivors, with the most common being displays of emotional distress such as crying (n = 17; 44.7%). Twelve researchers (31.6%) stated that they had not experienced any indicators of adverse events or harm in parent survivors. Most researchers (n = 30; 78.9%) also reported that parent survivors had indicated positive experiences as research participants.

In response to open-ended questions, a small number of researchers (n = 5; 13.2%) described negative experiences of parent survivors, with four indicating mental distress in the parent. One instance of a negative experience (2.6%) shared was very serious, with the researcher describing instances of severe physical harm during their research study. One researcher reported that they had witnessed “signs for parents maltreating their children during the study … . (and) children showing mental illness” (Participant #7).

Most researchers (n = 28; 73.7%) again described that many parent survivors had reported a positive research experience (percentages vary from multiple-choice to content analysis results, due to differing response rates). The most common benefits described by parent survivors were the opportunity to share their story (n = 16; 42.1%), research as a therapeutic process (n = 14; 36.8%) and feeling that they were helping others (n = 8; 21.1%). Researchers described that “participants reported that telling their story was cathartic” (Participant #35), with parents reportedly sharing comments such as “finally someone asks” (Participant #7) and parents communicating the experience as “validating to be seen as experts in their own experience and to be believed” (Participant #24).

Concerns of Ethics Committees

In response to multiple-choice questions, researchers reported the most common concerns of ethics committees in relation to research with parent survivors were potential harm to participants (“e.g., psychological distress due to asking about trauma;” n = 19; 50.0%), and participant consent (“e.g., concern about informed consent;” n = 12; 31.6%). Nine participants (23.7%) reported that ethics committees did not show unique concerns in their studies with parent survivors compared to research with other populations.

Qualitative results indicated that some ethics committees showed concerns particular to research with parent survivors (n = 20; 52.6%), such as study design (e.g., ensuring that psychological support was available on-site or online; n = 8; 21.1%), and child protection (n = 7; 18.4%). Unique concerns in the context of research with parent survivors included the explicitness of child maltreatment measures and having trained mental health professionals at hand to address distress throughout the project (e.g., “added two therapists in the agency as key personnel, so they could help with recruitment and follow up;” Participant #12). Regarding child protection, a reportedly common concern of ethics committees was the responsibility of researchers to report to authorities and/or child protection services if they uncovered instances of child abuse. An additional concern relevant to this population, is the situation where parents are still technically children themselves:

For parent survivors who were under the age of 16 years we were not able to interview without consent although they were parents in their own right. This would mean we had to either try to obtain consent from the state if they were under child protection orders or attempt to gain consent through other guardians however many did not have these figures.

Researcher’s Perceptions of the Ethics Process

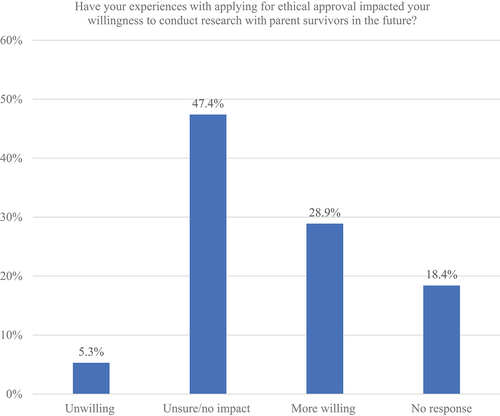

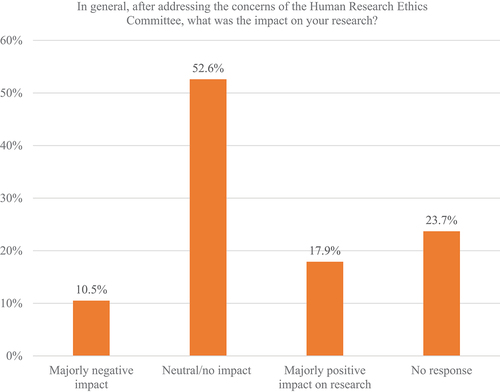

Through multiple-choice responses, most researchers reported that interactions with ethics committees had no impact (or that they were unsure of the impact) on their willingness to conduct future research with parent survivors (). Most researchers also reported that after addressing concerns of ethics committees, the impact on their research was neutral or not noticeable ().

Figure 1. Responses to a multiple-choice question about the impact of experiences with ethics committees on researchers’ willingness to undertake future research with parent survivors.

Figure 2. Responses to a multiple-choice question about researchers’ perception of the impact on their research after addressing concerns from ethics committees.

Few researchers commented on their perceptions of the ethics process in response to open-ended questions (n = 7; 10.5%). Of those who did, four researchers reported that they found it unnecessarily disruptive to their research (n = 4; 10.5%), while two reported finding it helpful (n = 2; 5.3%). One participant who reported finding the ethics process overly disruptive shared that:

Ethics applications can be lengthy, over-cautious or inappropriately cautious, and frustrating – and permissions processes taking a long time are the key barrier to successful research in this area for me – not the parents themselves. For example, requiring the recruitment method to change in my study severely limited my recruitment and therefore sample size – and the impact of my findings.

Another participant reported an overwhelmingly positive experience with their ethics committee:

The [name retracted] committee were fantastic to work with and provided some really good advice as we set out on our research, and it gave me great comfort knowing they took this very seriously and would tell us if we needed to do anything differently.

The final respondent to this question provided an answer that was neither favorable nor unfavorable of the ethics process when working with parent survivors but did highlight the need for further research into developing ethical guidelines when working with parent survivors: “There needs to be greater attention paid to these [ethics process] concerns and guidance provided to the field and researchers” (Participant #32).

Mental Health Support for Researchers

Half of participants (n = 19; 50.0%) indicated in multiple-choice responses that they had experienced symptoms of vicarious traumatic stress during research with parent survivors. The most reported symptoms were preoccupation with thoughts of participants’ story outside of conducting the research (n = 15; 39.4%) and distressing emotions (“e.g., grief, depression, anxiety, etc.”; n = 6; 15.8%). Fourteen participants (36.8%) reported that they had not experienced vicarious traumatic stress symptoms. Almost all participants also reported positive aspects of working with parent survivors (n = 33; 86.8%), including work satisfaction (n = 28; 73.7%), positive feedback from parent survivors (n = 25; 65.8%), and the ability to influence psychological practice through research (n = 18; 47.4%). Approximately half of the researchers reported that they felt their mental health was adequately supported (n = 18; 47.4%), four felt that they did not receive adequate support for their mental health (10.5%), and six selected the “other” option (15.8%). Those who selected “other” described that they had to personally advocate for mental health support for researchers (n = 1; 2.6%), that they did not feel this was necessary because they were able to find their own support (n = 3; 7.9%), and one was unsure (n = 1; 2.6%).

Qualitative contributions predominantly consisted of helpful strategies in protecting against vicarious traumatic stress (n = 27; 71.1%). Researchers reported that supervision or mentorship was essential for protecting researchers’ mental health (n = 17; 44.7%), followed by peer support (n = 15; 39.5%), and/or having a contingency plan for mental health (i.e., supports in place should researchers struggle with their mental health; n = 11; 28.9%). This was summarized by one participant as follows:

We generally allow for weekly group supervision with all case managers to talk about all difficult cases. This is a useful tool in terms of teaching. But for avoiding vicarious symptoms individual supervision would be preferable. I think we caught most of it by being very engaged with our case managers, but without the time for that one can never be certain. This ideally would work with mental health professionals and individual supervision on a regular basis. That however is costly.

Four researchers (10.5%) described that they felt insufficiently supported in their mental health, while four (10.5%) reported that they did not feel additional support was needed (e.g., “I feel I am able to manage this myself and seek support if and when needed;” Participant #26). One of the researchers who reported feeling inadequately supported in terms of mental health described:

I have to advocate very hard for it in public health systems and research institutions to ensure it is funded and properly supported … Again, this is a hard sell to funders and research institutions, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where mental health resources are generally underfunded or not available at all … . As a researcher in this kind of context, I feel it is my responsibility to ensure the research team has access to resources and often I need to fund that. (and defend my position to do so – which is typically a hard sell to institutions that typically don’t have a mental health focus)

DISCUSSION

The present study found preliminary evidence that research with parent survivors of child maltreatment may require extra safety precautions and considerations when compared to research with trauma survivors in general. Most researchers in our survey felt that parent survivors are a unique trauma population who require extra safety considerations, and most acted on this by including both preventative and reactive measures to avoid psychological or physical harm to the parents and themselves. This is at odds with findings from research with trauma survivors in general (i.e., non-parents or not studied in their capacity as parents; Jaffe et al., Citation2015). More than half of researchers had witnessed negative experiences of parent survivors during research (e.g., crying, complaint e-mails), and reported that ethics committees tended to treat studies with parent survivors as different to other trauma populations. Despite our findings supporting the hypothesis that parent survivors require dedicated safety guidelines and considerations, to the best of our knowledge, these do not currently exist. Although this is the first expert survey focusing on the safety of parent survivors of child maltreatment as research participants, these foundational findings should be considered in the context of a low response rate (discussed further in the limitations section).

Most researchers reported that they included extra precautions in research with parent survivors (e.g., ensuring staff were appropriately qualified and experienced to work with this population). Some participants referred to guidelines such as those for ethical research with children (Graham et al., Citation2013), interpersonal violence (World Health Organization, Citation2001), and prevention of vicarious trauma (Sexual Violence Research Initiative, Citation2015). However, only three participants reported using them as a reference. These resources cover a range of information for ethical research with children, however, only some sections are relevant to research with parent survivors. Therefore, it is advised that guidelines specific to safer research with parent survivors be created, ideally in collaboration with parent survivors (with appropriate precautions).

Researchers in the present study provided a variety of examples of safety precautions which may be useful in future research with parent survivors. An overarching theme in safety precautions was consideration of the trauma history of parent survivors in all aspects of study design, including (but not limited to): the study platform (e.g., online and anonymous, or in-person where psychological support can be provided), the type of psychological support provided and how it is offered (e.g., links to services provided at multiple time-points, or a combination of links and offer of a follow-up), and employing appropriate staff (ensuring both experience with parent survivors and appropriate qualifications in mental health).

These findings are in accordance with the principles of trauma-informed care. Trauma-informed care takes the position that many clients will have a trauma history which influences their symptoms, that this should be planned for in all aspects of care, and that a key responsibility of healthcare workers is to avoid re-traumatizing individuals (Racine et al., Citation2019). Recent studies have outlined trauma-informed approaches to qualitative research with trauma survivors (Alessi & Kahn, Citation2023; Isobel, Citation2021) and research in general (Edelman, Citation2023). However, there are not currently guidelines which provide guiding principles for working with parent survivors of trauma, which as the current study results indicate, are in a unique context compared to other trauma populations. As is outlined by Edelman (Citation2023), trauma-informed practice assumes that the research context has the power to exacerbate or attenuate adversities, such that the exact “protections” required will depend on the specific research project and participant (p. 47). The intersectional identities of being a trauma survivor and a parent do not currently appear to be catered for by available research safety guidelines and principles. While ethical/institutional review boards cannot account for every possible scenario, having clear, relevant, and specific trauma-informed principles can be important guides (Alessi & Kahn, Citation2023; Isobel, Citation2021). Currently available ethical guidelines do not appear to comprehensively account for the unique context of parent survivors of child maltreatment.

Promisingly, many researchers shared that some parent survivors had reported a positive experience as research participants. The most reported benefits of participating in intergenerational trauma research were the opportunity for parent survivors to share their story, finding research to be a therapeutic experience, and feeling that by sharing their experiences they could help other survivors. This pattern of both negative and positive experiences of parent survivors in research is in line with findings from other trauma populations as outlined by Jaffe et al. (Citation2015). However, Jaffe et al. (Citation2015) outlined mainly transitory and mild negative experiences in trauma survivors during research (e.g., fleeting psychological distress of significantly lower severity than the original traumatic stressor), whereas it is unclear if this was true of parent survivors with whom researchers in our survey worked. For example, some researchers outlined instances of severe mental distress in participants, and one researcher provided an example of the death of a participant during the study. However, it is important to note that experiences of child maltreatment are complex and will vary significantly in form and severity between individuals such that general conclusions about a given research sample are difficult to make (Jackson et al., Citation2019). The small and selected sample size limits understanding of how common such extreme adverse reactions are, however, given the evidence for increased risk for psychological distress in parent survivors it is imperative that the utmost precautions should be taken during research with them.

Some researchers shared that parent survivors found research participation to be a “steppingstone” toward receiving appropriate support, and an introduction to psychological therapy. This encouraging finding illustrates the potential for research with parent survivors to be especially impactful (i.e., that it can directly benefit parent survivors and their children), despite possible risks specific to this population. Specific guidelines for supporting the safety of parent survivors and their children in research may therefore have the potential to facilitate and improve engagement with necessary services.

The finding that vicarious traumatic stress symptoms were experienced by half of the study participants is of considerable note. As per van der Merwe and Hunt (Citation2019), ensuring the psychological safety of researchers is an important part of ensuring the safety of research participants. Further, as commented upon by participants in the present study, when conditions are psychologically safe for the participants and research staff, the quality of research tends to be higher (Nikischer, Citation2019). While most participants reported that their mental health was adequately supported, a small proportion of participants did not. Given high rates of burnout and staff turnover amongst mental health professionals and trauma researchers, it is important that the psychological safety of researchers is also prioritized and planned for (Močnik, Citation2020). Fortunately, almost all researchers reported significant benefits from working in this field, such as work satisfaction, positive feedback from parent survivors, and feeling that they were able to influence policy and psychological practice through research.

Researchers in the present study reported that the most helpful measures to protect their mental health while working with parent survivors were high quality supervision or mentorship, peer support, and a contingency plan for mental health (i.e., supports and access are agreed upon and outlined prior to the research project beginning). It is therefore important for researchers and their employing institutions to plan, budget, and prioritize these components of study design. This will help to ensure that research is as psychologically safe as possible for researchers, parent survivors and their families during and following research participation. Similar to van der Merwe and Hunt (Citation2019), our study results underscore the importance of ethics applications including provisions for mandatory trauma-informed psychological support, regular training, and supervision of researchers who work with trauma survivors. Without this support, it is likely that researchers will be negatively affected by vicarious traumatic stress.

Limitations and Future Directions

While the present study shows the strengths of novelty and recruiting a difficult population to access (e.g., small sample sizes are commonplace regardless of recruitment attempts when investigating researchers; Andriessen et al., Citation2019; Bailey et al., Citation2020), findings should be interpreted considering limitations. Although the sample size is not uncommon for expert surveys and mixed method data (and our data saturation indicates high quality evidence; Morton et al., Citation2012; Vasileiou et al., Citation2018), the response rate of 38 participants of the 370 contacted indicates that there was likely a strong selection bias. We hypothesize that our low response rate could be due to a variety of possible reasons: issues in retaining researchers in the field, our invitation ending in spam folders, researchers taking leave for summer break at universities, disagreement or lack of interest in the premise of the study, a larger pool of researchers compared to suicide research as per Andriessen et al. (Citation2019) and Bailey et al. (Citation2020) (and thus names being less easily recognizable via e-mail), and potentially researchers being excluded due to not submitting an ethics application within the last three years (in the context of recruiting in early-mid 2022, and the global pandemic interrupting research activities from 2020). Experts have been widely reported to be a difficult population to recruit (e.g., Shiyab et al., Citation2023), and future studies would benefit from incorporating differing recruitment approaches (e.g., in-person, via mailing lists).

Further, the study design may have influenced the results such that fewer people provided answers to the open-ended questions, potentially because they felt that their contributions were covered in the comprehensive multiple-choice options provided or because they understood it was optional. Future studies should prioritize direct consultation with parent survivors such as focus groups (to learn from their experiences as research participants) and/or advisory groups (to co-design and implement research) which can facilitate better understanding of their experiences as research participants and the support or precautions which they feel should be in place. These studies should consider relevant evidence regarding appropriate safety precautions for research with parent survivors (as outlined in the present paper) throughout the research planning stage, to ensure that participation is psychologically safe for all involved.

CONCLUSION

Research with parent survivors likely requires unique support and safety considerations compared to other trauma populations. Our results provide a rich source of ideas for how to support parent survivors and their families, and a point of reference for researchers and ethics committees in the absence of an evidence base specific to parent survivors. Findings from our study may increase the efficiency of ethical reviews, and the safety of research with parent survivors – though should be considered in the context of a low response rate. Researchers shared that both negative and positive experiences in parent survivors during research were common (the latter more so). Research participation appears to be a potential gateway to appropriate services for families or can be therapeutic in and of itself. However, given that negative experiences also occurred, in some instances, extremely severe (e.g., death), it is even more pertinent that appropriate safety precautions are sought and employed for all research with parent survivors and that this topic is further explored. Researchers who work with parent survivors should be aware that vicarious trauma symptoms are relatively common, but that appropriate support can help researchers to deal with these symptoms, and that this work remained highly rewarding. Given the documented prevalence of vicarious traumatic stress in trauma researchers, it is an institutional and ethical responsibility for project plans to include psychological support for researchers, and regular supervision from a trauma-informed professional. Without these provisions, the health of researchers may be negatively impacted, the issue of high staff turnover in trauma-related fields exacerbated, and poorer-quality research may be produced.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (44 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank the researchers who took the time to participate in our survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is not available for further investigation due to the requirement to protect the privacy of participants. Given the mixture of multiple-choice and open-ended responses, and the limited number of researchers in this field, it may be possible to identify participants if data is made available.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2023.2265519

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Alessi, E. J., & Kahn, S. (2023). Toward a trauma-informed qualitative research approach: Guidelines for ensuring the safety and promoting the resilience of research participants. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 20(1), 121–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2022.2107967

- Andriessen, K., Reifels, L., Krysinska, K., Robinson, J., Dempster, G., & Pirkis, J. (2019). Dealing with ethical concerns in suicide research: A survey of Australian researchers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(7), 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16071094

- Bailey, E., Mühlmann, C., Rice, S., Nedeljkovic, M., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Sander, L., Calear, A. L., Batterham, P. J., & Robinson, J. (2020). Ethical issues and practical barriers in internet-based suicide prevention research: A review and investigator survey. BMC Medical Ethics, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-020-00479-1

- Berger, R. (2021). Studying trauma: Indirect effects on researchers and self - and strategies for addressing them. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 5(1), 100149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2020.100149

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Volume1 Attachment. Basic Books. https://mindsplain.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/ATTACHMENT_AND_LOSS_VOLUME_I_ATTACHMENT.pdf

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge.

- Campbell, R., Adams, A. E., Wasco, S. M., Ahrens, C. E., & Sefl, T. (2009). Training interviewers for research on Sexual violence. Violence Against Women, 15(5), 595–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801208331248

- Carr, A., Duff, H., & Craddock, F. (2020). A systematic review of reviews of the outcome of noninstitutional child maltreatment. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 21(4), 828–843. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018801334

- Chamberlain, C., Gee, G., Harfield, S., Campbell, S., Brennan, S., Clark, Y., Mensah, F., Arabena, K., Herrman, H., Brown, S., Atkinson, J., Nicholson, J., Gartland, D., Glover, K., Mitchell, A., Atkinson, C., McLachlan, H., Andrews, S., Hirvoven, T. … Dyall, D. (2019). Parenting after a history of childhood maltreatment: A scoping review and map of evidence in the perinatal period. PLoS ONE, 14(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213460

- Collins, S., & Long, A. (2003). Working with the psychological effects of trauma: Consequences for mental health-care workers - a literature review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10(4), 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00620.x

- Dragiewicz, M., Woodlock, D., Easton, H., Harris, B., & Salter, M. (2023). “I’ll be okay”: Survivors’ perspectives on participation in domestic violence research. Journal of Family Violence, 38(6), 1139–1150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00518-6

- Eaton, K., Ohan, J. L., Stritzke, W. G. K., & Corrigan, P. W. (2016). Failing to meet the good parent ideal: Self-stigma in parents of children with mental health disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(10), 3109–3123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0459-9

- Edelman, N. L. (2023). Trauma and resilience informed research principles and practice: A framework to improve the inclusion and experience of disadvantaged populations in health and social care research. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 28(1), 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/13558196221124740

- Fenerci, R. L. B., & DePrince, A. P. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of trauma: Maternal trauma–related cognitions and toddler symptoms. Child Maltreatment, 23(2), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517737376

- Graham, A., Powell, M., Taylor, N., Anderson, D., & Fitzgerald, R. (2013). Ethical Research Involving Children. UNICEF Office of Research - Innocenti.

- Greene, C., Haisley, L., Wallace, C., & Ford, J. (2020). Intergenerational effects of childhood maltreatment: A systematic review of the parenting practices of adult survivors of childhood abuse, neglect, and violence. Clinical Psychology Review, 80, 1–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101891

- Isobel, S. (2021). Trauma-informed qualitative research: Some methodological and practical considerations. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(S1), 1456–1469. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12914

- Jackson, Y., McGuire, A., Tunno, A. M., & Makanui, P. K. (2019). A reasonably large review of operationalization in child maltreatment research: Assessment approaches and sources of information in youth samples. Child Abuse and Neglect, 87(September 2018), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.09.016

- Jaffe, A. E., DiLillo, D., Hoffman, L., Haikalis, M., & Dykstra, R. E. (2015). Does it hurt to ask? A meta-analysis of participant reactions to trauma research. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.004

- Legerski, J. P., & Bunnell, S. L. (2010). The risks, benefits, and ethics of trauma-focused research participation. Ethics and Behavior, 20(6), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2010.521443

- Liss, M., Schiffrin, H. H., & Rizzo, K. M. (2013). Maternal guilt and shame: The role of self-discrepancy and fear of negative evaluation. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(8), 1112–1119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9673-2

- Mathews, B. (2022). Legal duties of researchers to protect participants in child maltreatment surveys: Advancing legal epidemiology. UNSW Law Journal, 45(January), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.53637/OAKC2052

- McDonnell, C. G., & Valentino, K. (2016). Intergenerational effects of childhood trauma: Evaluating pathways among maternal ACEs, perinatal depressive symptoms, and infant outcomes. Child Maltreatment, 21(4), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559516659556

- Mctavish, J. R., Kimber, M., Devries, K., Colombini, M., Macgregor, J. C. D., Wathen, C. N., Agarwal, A., & MacMillan, H. L. (2017). Mandated reporters’ experiences with reporting child maltreatment: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. British Medical Journal Open, 7(10), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013942

- Michalopoulos, L. M., & Aparicio, E. (2012). Vicarious trauma in social workers: The role of trauma history, social support, and years of experience. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 21(6), 646–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2012.689422

- Močnik, N. (2020). Re-thinking exposure to trauma and self-care in fieldwork-based social research: Introduction to the special issue. Social Epistemology, 34(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2019.1681559

- Moensted, M. L., & Day, C. A. (2020). Health and social interventions in the context of support and control: The experiences of marginalised people who use drugs in Australia. Health and Social Care in the Community, 28(4), 1152–1159. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12946

- Moody, G., Cannings-John, R., Hood, K., Kemp, A., & Robling, M. (2018). Establishing the international prevalence of self-reported child maltreatment: A systematic review by maltreatment type and gender. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6044-y

- Morton, S. M. B., Bandara, D. K., Robinson, E. M., & Carr, P. E. A. (2012). In the 21st Century, what is an acceptable response rate? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 36(2), 106–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00854.x

- Nikischer, A. (2019). Vicarious trauma inside the academe: Understanding the impact of teaching, researching and writing violence. Higher Education, 77(5), 905–916. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0308-4

- Racine, N., Killam, T., & Madigan, S. (2019). Trauma-informed care as a universal precaution: Beyond the adverse childhood experiences questionnaire. Paediatrics and Child Health (Canada), 24(4), 274–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxz043

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. SAGE.

- Schwab-Reese, L. M., Albright, K., & Krugman, R. D. (2023). Mandatory reporting “will paralyze people” or “without it, people would not report”: Understanding perspectives from within the child protection System. Child and Youth Care Forum, 52(1), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-022-09676-y

- Sexual Violence Research Initiative. (2015). Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Vicarious Trauma Among Researchers of Sexual and Intimate Partner Violence. https://svri.org/documents/svri-resources?link-section=2016-2015

- Shiyab, W., Ferguson, C., Rolls, K., & Halcomb, E. (2023). Solutions to address low response rates in online surveys. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 22(4), 441–444. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvad030

- Smythe, K. L., Petersen, I., & Schartau, P. (2022). Prevalence of perinatal depression and anxiety in both parents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open, 5(6), E2218969. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.18969

- Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Alink, L. R., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2015). The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: Review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review, 24(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2353

- Toth, S. L., & Manly, J. T. (2019). Developmental consequences of child abuse and neglect: Implications for intervention. Child Development Perspectives, 13(1), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12317

- Trippany, R. L., Kress, V. E. W., & Wilcoxon, S. A. (2004). Preventing vicarious trauma: What counselors should know when working with trauma survivors. Journal of Counseling and Development, 82(1), 31–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2004.tb00283.x

- Trub, L., Powell, J., Biscardi, K., & Rosenthal, L. (2018). The “good enough” parent: Perfectionism and relationship satisfaction among parents and nonparents. Journal of Family Issues, 39(10), 2862–2882. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18763226

- van der Merwe, A., & Hunt, X. (2019). Secondary trauma among trauma researchers: Lessons from the field. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 11(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000414

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., & Thorpe, S. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

- Williamson, E., Gregory, A., Abrahams, H., Aghtaie, N., Walker, S. J., & Hester, M. (2020). Secondary trauma: Emotional safety in sensitive research. Journal of Academic Ethics, 18(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-019-09348-y

- World Bank. (2019). Country Classification. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/topics/19280-country-classification

- World Health Organization. (2001). Putting women first. Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Department of Gender and Women’s Health, Family and Community Health, World Health Organization.

- Yang, M. Y., Font, S. A., Ketchum, M., & Kim, Y. K. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: Effects of maltreatment type and depressive symptoms. Children and Youth Services Review, 91(April), 364–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.06.036