ABSTRACT

For contemporary Cree artist Kent Monkman, painting offers a means of rehistoricizing Indigenous life. However, rather than attempt to capture a putative authenticity, Monkman's work questions the relationship between visual representation and historical truth, deeply complicating his own task. This complication is managed in part through the careful deployment of self-reflection, such that the images of history he composes always advertise their unstable relationship to the past and the present, questioning theirs authority in the process of exposing how European artists attempted to establish their own. This exploration produces works that are highly citational, in which figures and elements from across European history and art history are juxtaposed and arranged into fantastic, anachronistic tableaus. But it is especially the works of Romantic painters that serve him as models for remodeling and settings for repopulation. Indeed, if Romantic painters such as George Catlin (1769–1872), Paul Kane (1810–71), and Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) flatten Indigenous people or actually evacuate them from North American landscapes, Monkman does not simply reject their work but realizes in it a rich potential for dialogic revision. In Monkman's painting, Romanticism's own historical self-consciousness finds new expression.

In “Altering Sight: Ideas in Motion,” Cree painter and performance artist Kent Monkman remarks, “Most of my work challenges history, or rather, dominant versions of history” (14). The “dominant versions of history” to which Monkman refers are those formulated, in part, by visual artists such as George Catlin (1769–1872), Paul Kane (1810–71), and Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902). Even if these artists make attempts to represent—rather than completely erase—Indigenous people from North American landscapes, such representations often tend, ironically, to dehistoricize their subjects. For these artists, Indigenous people and North America more generally often became props in an attempt to reproduce the Eden from which Europeans felt themselves banished by their own modernization and claims to cultural sophistication. As Jonathan D. Katz says of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century landscape painting:

Vast swaths of canvas were enlisted to perform an act of transubstantiation, reintegrating man and nature in a seamless unity at the very moment that unity began to fray, recasting a language of exploitation and conquest into images of Arcadian fullness and plentitude. (16)

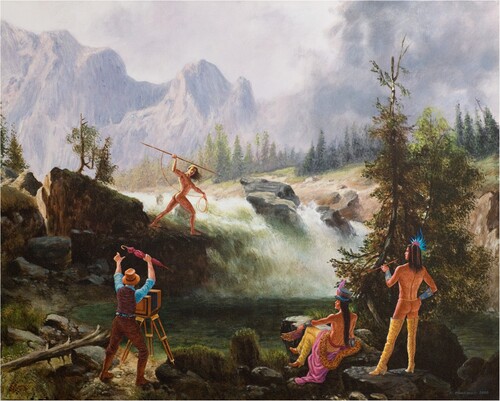

Monkman offers a concise reflection on the paradoxes of the visual representation of history in his 2008 painting, The Treason of Images (). A muscular, nude Indigenous figure hovers over rushing water, spear poised to strike. The surrounding landscape is wild; so too is the figure's hair, suggesting perhaps some kind of symbiosis of potent forces. Power and beauty combine in the idealization of Indigenous identity. However, as the larger frame of the action reveals, this is all for show: the spear hunter poses deliberately for the American photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868–1952), while two other Indigenous figures, spectacularly adorned, look on, their cool boredom juxtaposing Curtis's animation.

As this work makes especially clear, we cannot trust the documentary evidence of photography or even our own eyes, vulnerable as they are to such illusions. By widening the frame of Curtis's photograph, Monkman invites us to reflect on how historical facts are both discovered and produced. That is, Curtis's subject participates in a traditional activity using tools that are not inaccurate. And yet, he is also deliberately posed by Curtis, and is clearly imitating the action he performs. The moment is artificially manufactured and highly stylized. Still, as a citation of sorts, it is not pure invention. Moreover, it would be incorrect to assume that the wider scene, including the two flamboyant spectators, is true in any absolute sense—or that it is less the product of Monkman's own deliberate stylization of Indigenous identity. The image reminds us of the many complexities surrounding the historiography that emerges in the Romantic period, a time that witnesses, in the words of Stephen Bann, “a remarkable enhancement of the consciousness of history” and in which approaches to writing history multiply (4).Footnote1 It is precisely the legacy of this “consciousness of history” and the reshaping of genres of historical writing that animates Monkman's own practice.

Figure 1. Kent Monkman. The Treason of Images. 2008. Acrylic on canvas. 24 × 30 in. Image courtesy of the artist.

The title of the painting only deepens the work's intricacy. That is, at perhaps the plainest level, the title announces that images—even the most realistic, photographic images—are unreliable. The painting demonstrates this by illustrating what the photograph ignores and how the photographer stages the action. Yet viewers are quickly embroiled in a larger paradox in that this illustration of the unreliability of images is itself an image. Rather than offering the audience a stable position from which to judge the contrived representations of colonizers—a position of some kind of Indigenous authority and authenticity—Monkman opts instead to eliminate the prospect of an outside. Instead of claiming to offer a distinction between truth and falsity or history and fiction or authentic identity and inauthentic identity, Monkman suggests that there are only competing images and that selection among these images is a process unto itself guided by the desires of different audiences. This attitude chimes with the prevailing sense that historical writing cannot be simply factual, or that factuality is but one dimension of what makes history compelling. Indeed, the very determination of what counts as an historical fact comes about through a process of deliberate selection, baking the historian's interests and concerns into the analysis at this fundamental level. As E. H. Carr explains in his influential 1961 book What is History?:

The reconstitution of the past in the historian's mind is dependent on empirical evidence. But it is not in itself an empirical process and cannot consist in a mere recital of facts. On the contrary, the process of reconstitution governs the selection and interpretation of facts: this, indeed, is what makes them historical facts. (22)

To the extent that reality eludes quantification and extends beyond the photographable surfaces, knowledge limited to what can be supported by conventional evidence will never feel satisfying. The imaginative push through the impermeable membrane of other minds and lost actions will always be a movement towards truth, not fantasy. (28)

Yet Monkman does not title this work The Deception of Images or The Unreliability of Images or The Betrayal of Images—he calls it The Treason of Images. The term “treason” has an important legal resonance, suggesting as it does the usurpation or attempted usurpation of a state or sovereign power. Indeed, the fourteenth-century formulation of high treason indicates that merely thinking about such transgressions was already criminal; in the words of the statute as recorded in the OED, treason is in part defined as “compassing or imagining the king's death, or that of his wife or eldest son” (“Treason,” def. 2b). This attempt to police thought reaches a distressing intensity in the Treason Trials of the 1790s, which some have suggested lends to the entire decade a predominant mood of paranoia (Pfau 146–90). I am not suggesting that Monkman's title is a deliberate allusion to the Treason Trials. However, by casting the instability of images in these terms Monkman evokes the specter of an authority violated, of a sovereignty betrayed, of a state keen to censor and silence its critics. But whose authority or sovereignty is at issue for Monkman? It is tempting to stabilize the coordinates here and to say something like, “Monkman's painting performs a treasonous violation of Curtis's authority” or “Monkman's painting reveals how Curtis's photography violates historical truth.” However, both of these readings would reactively inflate the very authority that Monkman is attempting more radically to puncture. That is, Monkman's decision to cast the instability of images as “treasonous” aims to assert the power of the image and the imagination while, at the same time, revealing the fragility of any sovereignty that the charge of treason is supposed to protect. If images are treasonous by nature then they can never be fully coopted by authority. This may be the only reason to trust them.

The compositional counterpart to The Treason of Images is Monkman's Study for Artist and Model (2003).Footnote2 As with Treason, Study is a picture about images. Indeed, it is another example of what W. J. T. Mitchell calls a metapicture. In Mitchell's words, a metapicture is “an attempt to construct a second-order discourse about pictures without recourse to language, without resorting to ekphrasis” (38, original emphasis). In a metapicture, an image contemplates its own medium but from inside of and through its visual expression alone. Study for Artist and Model undertakes this self-reflection in several ways. For instance, the work highlights a distinction between mediums: Curtis's camera is literally axed and Monkman's alter-ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, sketches on an easel. Further, the image performs a complex displacement of model with artist. That is, not only does the Indigenous figure turn Curtis into the subject of her drawing, Miss Chief is herself a version of George Catlin in his self-portrait, Catlin Painting the Portrait of Mah-to-toh-pa-Mandan (1861/1869) (Madill 38). As is always the case with Monkman, there are several additional allusions to canonical works in the European tradition. Curtis's body position and wounds recall, for instance, Rubens's painting of the martyrdom of St. Sebastian (1614). Yet his attire—what little there is—is something out of “the cowboy painters Frederick Remington and Charles Russell who created the iconography of hats and boots and six guns that Hollywood sold to the world a few decades later as American mythology” (Hill 55). The lighting and lineation suggests yet another visual register. As Richard Hill observes:

the hard, clear, even light that defines this cowboy-photographer's body is not that of the cowboy painters, who preferred a looser brush and even flirted with impressionism. It is the light of mid-20th century illustration and of cartoon pornography, a light that wants to expose the body in clear detail, lest we miss something. (55)

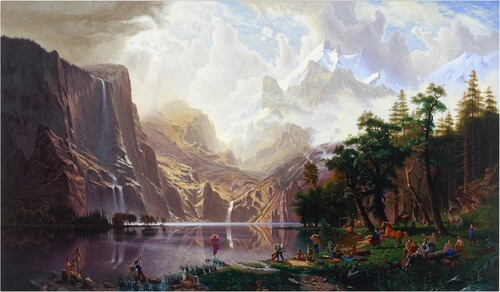

Figure 2. Kent Monkman. Trappers of Men. 2006. Acrylic on canvas. 84 × 144 in. Collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Art. Image courtesy of the artist.

Near the center of the scene “the Yanktonais winter count keeper, Lone Dog, is working on the winter count that bears his name” (Perry 89). Monkman notes that Catlin is “taking copious notes” from Lone Dog's count, a calendar in which a single “glyph or symbol represents a significant event for each year” (23). As Jack Halberstam remarks of Monkman's canvas, Catlin's cribbing from Lone Dog reveals how “modernist aesthetics are deeply dependent on the material they mine, discard, and then represent as primitive” (10). It is also true, however, that the cultural traffic was not all one way: precisely in response to artists such as Catlin and Karl Bodmer “the style of pictographs changed and [count keepers] began to incorporate additional details into their images” (Burke 1). This object also reminds us of Monkman's fundamentally Romantic interest in the expansion of what qualifies as history and the diversification of genres of historical writing. Indeed, the disorienting effect of the larger scene in which Lone Dog is located, one in which elements from different periods of European and art history are juxtaposed, taps into what James Chandler identifies as “a new conception of anachronism” that emerges in Romanticism, where “the spirit of the age” is given shape and definition through “a measurable form of dislocation” (107). The count itself, as a form of writing history, operates differently from Monkman's anachronistic museum. Still, in its idiosyncratic approach to which mundane facts are elevated into historical facts, the count rhymes with Romantic historical and poetic sensibilities.

Lone Dog's count covers the period 1800–70.Footnote3 It opens with a tally indicating that thirty Dakotas were killed by Crow Indians. Many of the pictograms in this and other counts record deaths, either though armed conflict or disease (for example, measles, smallpox, whooping cough, and dropsy). They often also record key diplomatic interactions with other tribes and European settlers as well as hunts and harvests especially good or bad. But there are also events rendered in pictograms that go beyond these perhaps predictable choices. For instance, there is a special interest in astronomical events in 1821–22, 1833–34, and 1869–70. There are also years in which the signal event is remarkably marginal or trivial. Take, for example, the pictogram for 1806–07, to which the following description is attached: “A Dakota killed an Arikara (Ree) as he was about to shoot an eagle” (Greene and Thornton 139). While this is a moment of violence, it does not concern known figures, and the scale is comparatively small. Yet there is a poignancy in the episode that speaks to a deeper poetic intelligence. For as concise as it is, the moment contains a dramatic reversal in which the hunter becomes prey. It is also an interestingly precise instant of time: the Dakota's arrow strikes its victim a split second before the latter secures the bird. The moment here selected to represent the year is especially fragile and fleeting; that it should be promoted into the official historical record may therefore seem odd. However, Romanticists are well positioned to appreciate how its very oddity is part of its virtue. Romantic poetry is full of instances that, like Wordsworth's spots of time, are “ordinary sights” (Wordsworth [1805] 11.308) that nevertheless become invested with exceptional, memorial power, or that erupt suddenly at “an uncertain hour” (Coleridge [1798], 615). Indeed, we will struggle less than most audiences to appreciate how much could hang on the decision to shoot a bird. The larger point, though, is not that the calendar here somehow channels the Ancient Mariner but that the winter count demonstrates a complex sense of what counts as history that parallels the Romantic recalibration of historical speeds and scales (Sachs 315). By featuring this form of record keeping in Trappers of Men, Monkman's canvas becomes not just a meta-picture but a meta-historical picture. The work invites viewers to reflect both on the juxtaposition of elements from different periods of art history for what this tells us about history's plasticity, and to reflect on what Mark Salber Phillips identifies as the sort of “formal experimentation,” distinctive of the Romantic period, “that changed the shape of historical accounts and altered the character of historical reading” (xii). In Monkman's work, the legacy of Romantic historical reading finds new life.

Notes

1 On the multiplication of historical genres, see Phillips. On the intensification of historical consciousness in Romanticism and its literary implications, see Chandler.

2 While Study for Artist and Model dates from 2003, the final product of this study, Artist and Model, was not completed until 2012.

3 Perry's claim that “this winter count is from the year the Lakota defeated Custer (1876) at the battle the Lakota call of the Greasy Grass but which is more commonly known as the Battle of the Little Bighorn” is misleading (89). The count was acquired by Hugh T. Reed in 1876 but there is nothing to suggest that the events of this year played any role in the production of the count or in its acquisition by Reed.

References

- Bann, Stephen. Romanticism and the Rise of History. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1995. Print.

- Burke, Christina E. “Waniyetu Wówapi: An Introduction to the Lakota Winter Count Tradition.” Greene and Thornton 1–11.

- Carr, E. H. What is History? 2nd ed. London: Penguin, 1990. Print.

- Chandler, James. England in 1819: The Politics of Literary Culture and the Case of Romantic Historicism. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1998. Print.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, and William Wordsworth. Lyrical Ballads 1798 and 1799. Ed. Michael Gamer and Dahlia Porter. Peterborough: Broadview, 2008. Print.

- Cronon, William. “The Trouble with Wilderness, or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature. Ed. William Conron. New York: Norton, 1995. 69–90. Print.

- Greene, Candice S., and Russell Thornton, eds. The Year the Stars Fell: Lakota Winter Counts at the Smithsonian. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2007. Print.

- Halberstam, Jack. Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire. Durham: Duke UP, 2020. Print.

- Hill, Richard W. “Kent Monkman’s Constitutional Amendments: Time and Uncanny Objects.” Thériault 49–72.

- Katz, Jonathan D. “Miss Chief is Always Interested in the Latest European Fashions.” Thériault 15–47.

- Madill, Shirley. Kent Monkman: Life and Work. Toronto: Art Canada Institute, 2022. Print.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1994. Print.

- Monkman, Kent. “Altering Sight: Ideas in Motion.” Art in Motion: Native American Explorations of Time, Place, and Thought. Ed. John P. Lukavic and Laura Caruso. Denver: Denver Art Museum, 2016. 14–37. Print.

- Partner, Nancy F. “Historicity in the age of Reality-Fictions.” A New Philosophy of History. Ed. Frank Ankersmit and Hans Kellner. London: Reaktion, 1995. 21–39. Print.

- Perry, Nicole. “Translating the ‘Dead Indian’: Kent Monkman, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, and the Painting of the American West.” Imaginations 11.3 (2020): 79–99. Print.

- Pfau, Thomas. Romantic Moods: Paranoia, Trauma, and Melancholy, 1790–1840. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 2005. Print.

- Phillips, Mark Salber. Society and Sentiment: Genres of Historical Writing in Britain, 1740–1820. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2000. Print.

- Plug, Jan. Borders of a Lip: Romanticism, Language, History, Politics. Albany: SUNY P, 2003. Print.

- Sachs, Jonathan. “Slow Time.” PMLA 134.2 (2019): 315–31. Print.

- Thériault, Michéle, ed. Interpellations: Three Essays on Kent Monkman. Montréal: Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery, 2012. Print.

- “Treason, n.” OED Online. June 2022. Oxford UP. Web. 18 May 2022.

- Wordsworth, William. The Prelude: 1799, 1805, 1850. Ed. Jonathan Wordsworth, M. H. Abrams, and Stephen Gill. New York: Norton, 1979. Print.