ABSTRACT

In spring 1892 the Stockholm literary magazine Ord och bild commissioned Swedish poet Gustaf Fröding (1860–1911) with a translation of Shelley’s “Hymn to Intellectual Beauty” (1816). At the time, Fröding was an accomplished poet and an experienced translator of Romantic poetry from English, German, and French. However, Fröding lamented in a letter to his editor that in “Hymn” he had encountered an unexpected problem with rendering Shelley’s poetry of meteorological form into Swedish. This is peculiar as Fröding’s own poetic compositions, original and translations alike, are deeply preoccupied with meteorology. Taking its outset in Fröding’s struggle with the translation, this essay investigates weather in “Hymn,” arguing that what had puzzled Fröding was a mode of meteorological representation idiosyncratic to Shelley. The essay suggests that it is precisely through these idiosyncratic meteorological representations that Shelley develops discourses of French materialist and British skeptical and empirical philosophy. This development culminates in an “aesthetics of weather,” expressive of Shelley’s radical conceptions of the social and physical world. The essay concludes that Fröding’s pronounced struggle and the variation in semantic content of his version of the poem reveal what is really the meteorologically precise poetic form of an aesthetics of weather in “Hymn.”

The weather in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poetry cannot be translated. So declared Gustaf Fröding (1860–1911), a Swedish poet who had been commissioned by the Stockholm literary magazine Ord och bild [Word and Picture] to translate “Hymn to Intellectual Beauty” (1816) in spring 1892. Fröding, a distinguished poet in his own right and an experienced translator from English, German, and French, had gained the commission owing to the fact that Hellen Lindgren (1857–1904)—a prominent critic of English literature—needed a poem to accompany an essay that he was writing on Shelley for the magazine. Although a couple of Shelley translations had begun to circulate at the time, Lindgren had indiscriminately dismissed them as “lousy,” as he put it in an unpublished letter to Ord och bild’s editor, Karl Wåhlin (1861–1937).Footnote1 Much impressed with one of Fröding’s translations of Byron, Lindgren consequently urged Wåhlin to ask Fröding for a translation of “Hymn,” stressing in a postscript to his letter that this poem “would be the best” for the purpose. At stake with the translation, as Lindgren would state in his 1892 essay, was to introduce “a poet whom we fear that few Swedes know about, even though his poems are regarded by many as the finest poetic work of the century” (354). Lindgren was sure that Fröding would do Shelley’s poetry justice. However, Fröding had encountered an unexpected problem with “Hymn”: a problem with meteorological form. As he lamented in a letter to Wåhlin, dated 30 June 1892, “the language itself is so sky light and moon glimmer-like that it cannot be replicated” (Gustaf Frödings Brev 2 [hereafter Brev 2] 45).

Fröding’s perplexity is curious because his own writings were deeply preoccupied with meteorology. Around the same time he was struggling with Shelley’s “Hymn,” he composed his own poems, “Vackert väder” ‘Beautiful weather,’ “Vinternatt” ‘Winter night,’ “En litten låt ôm vårn” ‘A short lyric on spring,’ “Vår” ‘Spring,’ “Höst” ‘Autumn,’ and “Infruset” ‘Icebound,’ as well as translating some other Romantic European poetry on meteorological topics. During this period he rendered German poet and explorer Adelbert von Chamisso’s “Ungewitter” (1826) as “Oväder” ‘Bad weather,’ and Austrian poet Nikolaus Lenau’s “Herbstgefühl” (1832) simply as “Höst” ‘Autumn.’ As Dag Nordmark has argued, Fröding’s own poetry was greatly influenced by the meteorological forms he encountered in these translations, indeed, so much so that the wild storm described in Fröding’s free translation of Chamisso’s lines “Das Ungewitter ziehet / herauf mit Sturmesgewalt” as “Se ovädret nalkas och stormen / har börjat sin vilda lek!” ‘See the bad weather approaching and the storm / has begun its wild play!’ (19–20) was an image to recur frequently in Fröding’s own poetry, where it becomes a kind of leitmotif as a metaphor of social upheaval (Pajas 84).Footnote2 Even so, despite his evident facility for evoking the elements in verse, Fröding had encountered a unique challenge in Shelley’s “Hymn”—an idiosyncratic representation of weather that stubbornly resisted translation.

In part, Fröding had accepted the commission for reasons of financial necessity. A few months earlier he had reluctantly relocated from Norway to Sweden to work as a journalist. Just before seeking renewed treatment for mental illness at the Norwegian sanatorium, Fröding had written to Albert Bonnier (1820–1900), his publisher, offering to undertake translation work. Although he was primarily in need of some “gentle occupation,” as he put it, he explained that “the pecuniary side of things also has some significance for me” (Gustaf Frödings Brev 1 [hereafter Brev 1] 204).Footnote3 Such considerations evidently overcame his misgivings about translating “Hymn” and he duly submitted his rendition to Ord och bild, in whose debut volume it appeared as “Hymn till den själiska skönheten” ‘Hymn to the spiritual beauty,’Footnote4 before being republished, with minor emendations, in his own collection Nya Dikter [New poems] in 1894.Footnote5 As these minor emendations indicate, however, Fröding was not pleased with his “Hymn.” In fact, his translation troubled him for the remainder of his life, to the effect that many years later he inserted a self-critical comment in the margin of his copy of the published version of his “Hymn”: “[T]he subtle beauty of [Shelley’s] original has only been done justice to a slight degree” (Samlade Dikter).

The strangeness of the poetic weather that Fröding claimed as being so frustrating in that letter is readily apparent from the opening stanza of Shelley’s “Hymn.” The immediate challenge for the translator is to render Shelley’s evocation of “The awful shadow of some unseen Power” that “Floats tho’ unseen amongst us” through a succession of complex meteorological similes: “As summer winds,” “Like moonbeams,” “Like hues and harmonies of evening,” and “Like clouds in starlight widely spread” (1–9). While this “Power” may be “unseen”—and Shelley is insistent on this point—it nevertheless can be conceptualized and has a parallel in a system of meteorological phenomena that is both precise and measurable. No less importantly, and a fact of which Fröding, as a practicing poet, would have been acutely aware, this relationship is also intimately bound up with meter; together, measured language and semantic content establish Shelley’s poetic form of weather. However, as Fröding regretfully stated in a letter, dated 2 May 1891, “English words are generally a third shorter than in Swedish and if one wants to maintain the same verse form it becomes therefore absolutely impossible to express all thoughts completely as in the original” (Brev 1 238). He was faced with a dilemma: either abandon meter in favor of literal fidelity or prioritize metrical conformity over semantic content. With “Hymn,” he chose to replicate the meter.

This decision was unfortunate, however, because the meteorological precision of the similes in “Hymn” is more important than meter for the poem’s argument, which is that specific forms of weather reveal truths about humanity’s relationship to Nature. Thus in the second stanza, Shelley’s speaker poses a series of questions about these truths in relation to modes of weather:

Shelley’s answers to these meteorological questions come in the following stanza and are framed in atheistic terms. The evidence of the weather indicates that the unseen power cannot be divine in nature: “No voice from some sublimer world hath ever / To sage or poet these responses given” (25–26). The speaker refuses to attribute the inconsistencies of rainbows or sunlight to the actions of a creative deity. On the contrary, the dynamic forms of weather reveal that humanity’s relationship to Nature is sufficiently sublime in its own right:

What frustrated Fröding in his harried efforts at translating “Hymn” was thus a radically new poetic representation of weather that integrated a philosophical vision of human life with minute observation of the physical world. The precise nature of this poetic object is the focus of the following essay. Taking my starting point in Fröding’s struggle to articulate Shelley’s “hues and harmonies” in Swedish, I engage with textual history, unpublished archival materials, Fröding’s own theories of translating Romantic poetry, his readings in European literature and philosophy, and recent scholarship on Shelley’s poetry and his intellectual development in order to shed new light on the meteorological framework of this landmark poem and, above all, its embodiment of what I will be calling an aesthetics of weather. As I argue, through the poetic representations of meteorological phenomena in “Hymn,” Shelley develops discourses of French materialist and British skeptical and empirical philosophy to express his radical sentiments on natural philosophy and art. Engaging with contemporary and historical discourses on the relationship between physical sense perception and the human imagination, Shelley came to conceive of meteorology as a materially experienced, but imaginatively re-presented poetic form: the beauty of weather as formulated through a philosophical framework of physical sense perception, the meaning of the word aesthesis. It follows then that the idea of an “aesthetic” can be employed as a critical term for conceptualizing how poetic forms of weather constitute Shelley’s engagement with a philosophy of nature and a philosophy of beauty in art. Thinking through Shelley’s aesthetics in this way, the term recalls the Greek origins of the word which, through the German metaphysicians (especially Baumgarten and in turn Kant’s responses to him), came to expand as a discipline and develop in terms of its applications throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.Footnote6 Read closely against the original, the variations in semantic content and literary form in Fröding’s Swedish translation of “Hymn” can also help us better understand how and why Shelley developed and positioned himself within philosophical and literary discourses through such an idiosyncratic treatment of weather. Reading Shelley’s poem back through Fröding’s difficult and unsuccessful attempts to translate it grants us a fresh comparative perspective on Shelley’s weather in “Hymn.”

Reading Shelley’s original and Fröding’s translation side by side, we can notice a few crucial differences, with the first casualty of the Swedish version being empirical precision. In Shelley’s first stanza the adjective “inconstant” makes two appearances: the “unseen Power” presents itself “with as inconstant wing / As summer winds” (1–4) and “It visits with inconstant glance / Each human heart and countenance” (6–7). On the first occasion, Fröding omitted the adjective entirely, and on the second he chose to use the Swedish word “flyktigt” (“flighty,” “fickle”). There was no historical-linguistic rationale for such a decision: the Swedish cognate inkonstant was well established and in common use by the early eighteenth century and further consolidated as an empirical term in the course of the nineteenth century. Nor is it likely that Fröding, a skilled poet who frequently altered the structure and changed or omitted words in his other translations, made these choices merely in order to preserve the tetrameter. Had he felt it necessary to use this particular word, he could easily have accommodated it in his text.Footnote7

Rather, Fröding’s alteration and omission of Shelley’s “inconstant” seem to have derived from two factors: his underestimation of the poem’s empiricist tenor and his imposition of an arbitrary choice of meter. The latter, however, is not so curious. Fröding freely acknowledged that arbitrary choices were part of his approach to the craft of translation. Two years previously, he had sent some specimen translations to Carl Rupert Nyblom (1832–1907), a professor of literature at Uppsala University and himself a talented translator of English poetry, who responded that Fröding’s renditions were “quite good” if “overly ‘free’” (Brev 1 190). Fröding had anticipated this critique and defended his “free” translations to Nyblom as a point of principle:

The liberties I have taken with the originals probably depend partly on sloth, but also partly on fundamental principle. I try to imagine how the poet would have expressed himself had he written in Swedish, and it seems to me that he would not always have chosen the same words and phrasing as in the foreign language. (Brev 1 179)

As it happens, the textual history of “Hymn” reveals that Shelley had been highly deliberate in using the word “inconstant” in relation to weather. Comparison of the first published version of the poem in The Examiner on 19 January 1817 with the version in the Scrope Davies notebook (famously rediscovered in a London bank vault in 1976) shows that his second use of “inconstant” had originally been “wavering” in manuscript.Footnote8 Obviously, Fröding could not have known about Shelley’s emendation of the draft, but he can hardly have overlooked the emphasis created by the word’s reappearance within the space of four lines. Like Shelley’s repetition of “unseen” in the first two lines, it directs the reader to identify inconstancy as central to the significance ascribed to weather in “Hymn.” The repetition here, moreover, is a self-referential linguistic form, since it draws attention to what is both its expressive precision and linguistic limitation. It is exemplary of how Shelley’s engagement with weather forces him to develop a register that is nevertheless firmly based on a skepticism about language, by which, as William Keach has argued, “Shelley acknowledges its [language’s] inherent limitations while extending its resources” (42). It is a repetition of a highly deliberate word, a precise use of an elaborate poetic form, yet through its mode of repetition it also manifests the limitations of its own precision. Jerrold E. Hogle has characterized such repetitions, occurring within the scope of a few lines in “Hymn,” as an example of Shelley’s “hope of pinning down that movement” which is the “perpetual metamorphosis” (69) of the form of the spirit in the poem. But as such, this bold repetition also problematizes what Daniel Westwood identifies as Shelley’s recurrent “way of teasing out nuance” (36) in this poem. On this occasion, by contrast, the poem values emphasis above nuance by insisting that the reader experiences weather neither as “wavering” nor “fickle,” but only as “inconstant.”

In his later essay fragment “On Love” (1818), Shelley would further problematize such linguistic precision in meteorological terms. Although he regrets in a marginal note “words inefficient & metaphorical,” emphasizing that “Most words so—No help—” (618), he finds that “[t]here is an eloquence in the tongueless wind” (619) capable of revealing its “inconceivable relation to something within the soul” (619). The way Shelley’s “Hymn” repeats the word “inconstant” in relation to the poetic mode of simile suggests that in meteorological events, in their physical form and force, the sign-signifier relationship is particularly precise in its nature.Footnote9 Through its paradoxically precise inconstancy, weather reveals “the bond and the sanction which connects not only man with man, but with every thing which exists” (618). For Shelley, such a sensuous understanding of the relationship between weather and the condition of being human, at once a social and ecological being, demanded an uncompromisingly tight poetic form that makes linguistic expression and philosophical content completely interdependent.

Yet in order to grasp the importance of what Fröding lost in translation, we need to consider also the underlying philosophical discourses of the term “inconstant.” As a substantial body of scholarship has now established, Shelley, more so than his contemporaries, integrated his extensive readings in eighteenth-century British and Continental philosophy into his poetic composition.Footnote10 What this means is that Shelley’s poetical representations of the physical world and its various phenomena and dimensions—and, perhaps above all, meteorology—must be read as an engagement with material and skeptical philosophy. More specifically, Shelley’s weather was informed by his reading of Baron d’Holbach, David Hume, and William Drummond, whose ideas are readily discernible in “Hymn” and his other works of this period.Footnote11

A key premise for our reading of the weather in “Hymn” is how Shelley’s own contribution to these philosophical discourses on the physical world involved theorizing the creative process of the human imagination. Principally we must turn to his Defence in this regard, that “great aesthetic peroration on many themes concerning the imagination developed in the two generations preceding Shelley,” as James Engell puts it (256). In the Defence, Shelley offers an account of the relationship between empirical philosophy and the imagination; noting that “We want the creative faculty to imagine that which we know” (672), he argues that the imagination or “creative faculty” must process, modify, evaluate, and develop philosophical truths about the world or “that which we know” into new and refined forms of knowledge. As Cian Duffy observes, the Defence sketches a Shelleyan concept of an “educated imagination,” designating an active, critical, and selective process that shapes human understanding of the physical world by interpreting knowledge derived from sensuous impression (Shelley 9). For Shelley, true knowledge starts with empirical sense perception but ends in the processes of the creative imagination. In the case of “Hymn,” the sensuous impressions in question are various kinds of weather phenomena: the philosophical truths offered by the poem are products of Shelley’s creatively imagined weather.

This creatively imagined weather led Shelley to reject what he saw as misconceptions about the natural sublime in favor of a logic of sensory perception; his speaker disavows any notion of “some sublimer world” (25). As Duffy and Hamilton have argued respectively, such philosophical reconfiguration of the sublime is owing to Shelley’s engagement with the theories of Holbach, the French materialist whose writings he read especially closely.Footnote12 In his Système de la Nature (1770), Holbach had declared that the religious doctrine of a supernatural world was the result of “une imagination égarée par l’autorité” ‘an imagination misled by authority’ (“Preface de l’auteur”; my trans.), a telling formulation which implied that the imagination is forced into drawing uneducated conclusions about the physical world. It was precisely such dogmatic thinking that Shelley sought to challenge with the weather of his “Hymn.” As his speaker explains, in contrast to the sensuously unheard and unseen “voice” of the “poisonous names with which our youth is fed” (53), weather is both seen and heard; it is precisely sensuously perceptible. Contrary to Richard Isomaki’s conclusion, that like the creative deity the intellectual beauty is “equally incapable” (65) of revelation, the unseen Power is indeed revealed in the action of the elements. The wind is heard as “Thro’ strings of some still instrument” (34) and is visible in its “wooing / All sweet things that wake to bring / News of buds and blossoming” (56–58). Weather defines the growth cycle of plants and “All vital things” (57) and ensures that every feature of the physical world—animate and inanimate, human and non-human, material and immaterial—act and react upon each other. More than this, it reveals to Shelley’s speaker “the truth / Of nature” (78–79) in a dynamic which makes “Love, Hope and Self-esteem, like clouds depart / And come, for some uncertain moments lent” (37–38). Paradoxically, the very uncertainty of these meteorological stimuli reveals to Shelley’s speaker the true quality of the natural sublime. The fluctuations of meteorological stimuli such as winds and clouds create a movement that works upon the speaker’s senses, connecting him to an underlying—and, crucially, inconstant—order in the physical world. “Hymn” replaces the theistic sublime with the sensuously imagined sublime of weather.

By re-imagining the sublime as a “Power” that is physically present in the meteorological events in “Hymn,” Shelley revises the currency of the term through his negation of the inflected form, “sublimer.” The inflection of this precise word, as with the repetition of “inconstant,” reveals a Shelleyan meteorological register that would have been consciously and conspicuously provocative for prevailing contemporary cultural discourse on the physical world. It is a determinate and inviolable grammar of sublimity which is integral to the meteorological integrity of the poem because there can be no power beyond such meteorological sublimity. However, in Fröding’s “Hymn” this crucially inflected word is missing: “Men ingen röst från ofvan ger ett svar” ‘But no voice from on high gives an answer’ (25). But as with his treatment of “inconstant,” Fröding’s decision to translate the critical phrase “some sublimer world” (25) as simply “ofvan” ‘on high’ cannot be rationalized on linguistic or cultural-discursive grounds. The cognate term sublim was well established in Swedish at this time and used frequently by Fröding himself. In a letter to his relative K. G. Petterson, dated 19 July 1886, he explains that without the appropriate use of the “sounds of language” in poetic diction “the sublimest thoughts appear dry and prosaic” (Brev 1 113). Fröding uses the term with philosophical appropriateness here, even exhibiting his sure command by inflecting the concept in the superlative. In the case of “Hymn,” however, “on high” cannot substitute for the sublime because the phrase needs to evoke connotations beyond merely alluding to the spatial positioning of the perceiving subject and the meteorological phenomena in the poem. Although he was familiar with the concept as one of intense emotional experience in relation to physical space and material phenomena, Fröding seems to have chosen arbitrarily a less precise substitute phrase that sacrifices the semantic domain of Shelley’s “sublimer.”

Fröding would have been familiar with the concept of the sublime owing to his extensive reading in Romantic literature. As Brian Downs notes, from an early age he had “immersed himself” (850) in English Romantic writing and, during his institutionalization in Germany in 1889–90, he had been an avid reader of Tauchnitz’s editions of British and American poetry and biography, including works by Byron, Burns, Poe, and Carlyle. The latter’s The French Revolution (1837), Fröding declared, “is a particularly remarkable book, original in every letter” (Brev 1 167). He would also have encountered the sublime in his reading of German Romanticism. In a letter to his sister, dated 7 October 1889, he relates spending “the whole day reading German classics and romantics – Lessing, Schiller, Kleist, Chamisso, Lenau etc” (Brev 1 152). The Romantic aesthetics of the sublime was at Fröding’s disposal, intellectually and linguistically, should he have chosen to adopt it.Footnote13

Fröding’s arbitrary lyrical translation of “sublimer” fails to capture Shelley’s attempt to position himself within contemporary cultural-philosophical discourse on the sublime. Shelley’s specific aim was, as Duffy argues, “to revise the standard, pious or theistic configuration of that discourse along secular and politically progressive lines” (Shelley 7). Particularly suitable for such cultural revision were the dynamic and material effects of weather on the human senses, because weather is a democratic form of nature insofar as it exists to various degrees in the popular imagination of all individuals and, in some way or other, affects all people regardless of their class or geographical position. As Peter Anderson notes succinctly, “The weather, like death, makes kin of us all” (55).Footnote14 In this shared human sensibility Shelley saw a means of expressing secular democratic ideas through forms of weather. And in developing his weather in accordance with such a rationale that materially rejects the supernatural sublime, Shelley aligned “Hymn” with what at the time was rapidly becoming a secular and scientific understanding of meteorology in public, private, and professional discourse.

At the time when Shelley composed “Hymn,” meteorology like other disciplines within natural philosophy—as the natural sciences would have been known then—had increasingly become a systematized inquiry based on physical and measurable observation. These new material understandings had their roots in the philosophical discourses and institutions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As Jan Golinski has documented in his history of popular discourse on English weather, the predominance of “divine punishment” in explaining extreme meteorological phenomena such as storms, cloudbursts, and heatwaves or cold snaps had by the early eighteenth century been challenged by scientists and commentators who “urged a more ‘philosophical’ approach to weather” (42).Footnote15 The founding of the Royal Society in 1660 had provided that natural philosophers could conduct research more closely as a collaborative effort. The Society fellow Robert Hooke (1635–1703) succinctly describes this new practice in his preface to Micrographia (1665):

By means of Telescopes, there is nothing so far distant but may be represented to our view; and by the help of Microscopes, there is nothing so small, as to escape our inquiry; hence there is a new visible World discovered to the understanding. By this means the Heavens are open’d, and a vast number of new Stars, and new Motions, and new Productions appear in them, to which all the antient [sic] Astronomers were utterly strangers. (par. 12; original italics)

There are three main reasons to be found in Fröding’s writings for his misconstruction of such poetic-scientific synthesizing in “Hymn.” Firstly, unlike Shelley, Fröding did not care for a tight relationship between natural science and poetry. In a letter to his sister, dated 12 April 1889, he laments that “poetry has lost its connection to the music and instead approached science” (Brev 1 142), a point of opinion which he consolidates in his letter to Carl Rupert Nyblom, dated 12 March 1890, complaining that “. . . poets of late much too little take into consideration the musical element in versification” (Brev 1 179). For Fröding, lyrical quality was paramount to semantic content. Secondly, Fröding did not appreciate an epistemology rooted in materialism. In a letter to his cousin, Siri Fröding, dated 1 January 1889, he explains his admiration for the theological idealism of the Uppsala professor of philosophy Christopher Jacob Boström (1797–1866) rather than for Herbert Spencer’s “empiricism,” finding the latter “almost too heavy for me,” “at least around Christmas.” He consequently quipped: “How much better would not my stomach fare if it were only seemingly real pork sausages and pork ribs I consumed. I wish that stomach ailments and constipation and all other infirmity were only Boströmian ‘phenomena’” (Brev 1 126). Thirdly, Fröding did not recognize the empirical dimensions of the creative imagination. In his manifesto on the difference between Romanticism and Naturalism in European literature, “Naturalism och romantik” (1890), he conceptualizes the Romantic “imagination” as a whimsical power with a “sovereign right to govern as it pleases” (16). This sketches an arbitrary power of the imagination which is in complete contrast to the educated imagination Shelley explicates in his Defence, the kind that can be exercised to improve human understanding of the social and material world. Whereas Shelley recognizes that the imagination is the instrument for reconciling the ideal and material, Fröding merely recognizes the imagination as the instrument of the “teller of fairytales” (27). By extension, Fröding may be taken to imply that there was a lack of material substance in Romantic diction.

The progress that had been made in the mode of meteorological observation in the seventy-odd years between Shelley’s “Hymn” and Fröding’s translation, however, was directly related to such Romantic-period poetic-empirical relations which Shelley’s “Hymn” evokes through its philosophically imagined weather. Not least were the improvements in cloud classification, conducted by international meteorological authorities H. H. Hildebrandsson (1838–1925), professor at Uppsala University, and Royal Meteorological Society Fellow Ralph Abercromby (1842–97), specifically grounded on the work of Shelley’s contemporary, Luke Howard (1772–1864). Fröding’s paramount regard for lyrical quality over scientific content does indeed, as he himself feared in one of his letters, “offend the conception of romanticism” (Brev 1 179) in this neglect for the materially precise. Such an “offence” underwrites his choices in translation and helps to explain the limitations of his rendition of Shelley’s weather in “Hymn.”

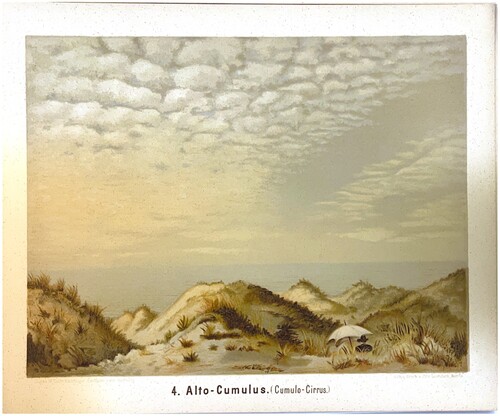

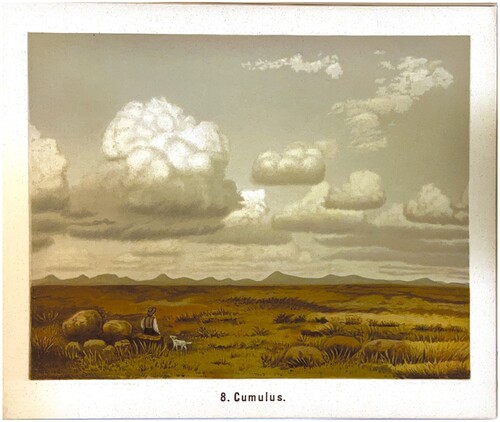

Indeed, his “offence” against the Romantics in general, and Shelley’s “Hymn” specifically, becomes graver as we consider that the so-called “scientific” mode of weather observation, pioneered by figures such as Hildebrandsson and Abercromby, was in fact directly dependent on aesthetic configurations of meteorology. The first Cloud-Atlas (1890), compiled by Hildebrandsson and his colleagues Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) and Georg von Neumayer (1826–1909), is an essential document in this regard. In it, meteorology is developed as a science proceeding from human subjective responses to aerial events. Aided by artistically rendered representations of the sky, Hildebrandsson and his colleagues developed an atlas of the clouds based on such subjectivity. Particularly notable instances in the Atlas are pictures 4 and 8 (see and ), where the former (of the Alto-Cumulus) depicts a human figure positioned under a parasol sheltering from the sunlight that slips through the clouds, and where the latter (of the Cumulus) depicts clouds as being observed by a human figure looking roughly at a 45 degrees angle towards the sky, suggesting the active contemplation of these celestial phenomena.

Figure 1. “Plate 4. Alto-Cumulus,” from H. H. Hildebrandsson, Cloud Atlas (1890). Courtesy of National Library of Sweden.

Figure 2. “Plate 8. Cumulus,” from H. H. Hildebrandsson, Cloud Atlas (1890). Courtesy of National Library of Sweden.

As these pictures illustrate, the Atlas does not show what the clouds are in themselves but rather how they appear to human observation. The mode of painting, moreover, was unmatched by contemporary technology for achieving this human dimension in cloud description. Although employed in the Atlas, photography, still in its relative infancy as a technology, was incapable of reproducing the important color distinctions of cloud landscapes, to the extent, as the authors complain, that many such renderings would seem “almost unnatural to the human eye” (par. 6). As much as these pictures (paintings and photographs alike) were by no means meant to be especially “artistic” (as Hildebrandsson and his colleagues make clear in the first passages of the Atlas), the Atlas’s emphasis on sensuous experience nevertheless necessitates an aesthetic configuration of the clouds. Moreover, this aesthetic mode of description becomes a shared human experience as readers are invited to reflect on their own bond to the weather as much as on that of their fellow perceivers figured in the foregrounds. In fact, such an aesthetic mode of description, as Robert A. Houze Jr. and Rebecca Houze have argued, was much more closely related to the “human experience” (442) than our contemporary methods of meteorological observation. Fröding’s anxiety of invoking a poetics subsumed by science emerges as a false premise, then, because, as the Atlas makes clear, the matter would rather have been the opposite: a science of the weather was dependent on aesthetic configuration of the atmosphere, in 1892 no less than in 1816.

The creatively imagined and empirical meteorological phenomena in Shelley’s “Hymn” are such a configuration of weather as aesthetics. Weather is aesthetic here because of its mode of aesthesis. The celestial features in the poem manifest a “form” which like “spells did bind” the speaker (82–84). As external material stimuli, weather “Descended” on the “passive youth” (78–79). The preposition “on” designates that the speaker is subject to the meteorological powers which integrate him as an object into the natural system. The “harmony / In autumn” (74–75) and the “lustre in its sky” (75) “supply” (80) sensuous stimuli through which the speaker re-connects our perceptions of what is internal and what is external to us at the same time, “To fear himself, and love all human kind” (84). Moreover, the meteorological processes blend internal with external beauty, poetic affection with philosophical discovery, and create the aesthetic experience of the “truth / Of nature” (78–79). Such drawing together of the external with the internal in the meteorological mode of aesthesis produces that effect which Keach has recognized as the “perceptual continuum” in Shelley’s poetry, that “indeterminacy” (78) in his figurative language which challenges the reader to recognize this interplay between mind and matter in its various linguistic forms. And however carefully elaborated, these linguistic forms remain imperfect products of the meteorological aesthesis, which becomes that “awful Loveliness” (71) that “Wouldst give whate’er these words cannot express” (72). Yet despite all such indeterminacy, in “Hymn” the “spirit of Beauty” with its perpetually manifested inconstancy is still recognizable in such aesthesis of weather, just as it is revealed for the speaker in the action of winds:

Such moments of meteorological beauty are constantly bound up with change and restlessness in Shelley’s later poetry. To take only two obvious examples, in “The Cloud” (1820) we find the paradoxical quality of such constant inconstancy. The personified cloud muses that “I change, but I cannot die,” because the cloud is “the daughter of Earth and Water, / And the nursling of the sky” (73–76). Like the “unseen Power” in “Hymn,” the cloud is a dynamic celestial form that alters constantly, rendering the experience of cloud formation an inconstant experience for those “thirsting flowers” (1) and “mortals” (46) who are exposed to the meteorological effect contained in, and expressed through, this vaporized inconstancy suspended, while always changing, in the sky. In his great “Ode to The West Wind” (1819), however, such transitory meteorological formations are an experience more acutely altitudinal than in either “The Cloud” or “Hymn.” In the “Ode,” the aesthesis for the speaker is now a visual prospect of height and verticality, where “’mid the steep sky’s commotion, / Loose clouds like Earth’s decaying leaves are shed” (15–16). Unlike what we read in the “Hymn,” there is a hierarchical relationship between the various meteorological phenomena: the wind is that “Uncontroulable” (47) and “tameless, and swift, and proud” (56) “Spirit fierce” (61) from which clouds are shed as byproducts. And the speaker longs to be incorporated into a tighter relationship with this meteorological power, exclaiming “Oh! Lift me as a wave, a leaf, a cloud!” (53). Yet the underlying anxious tone alludes to the West Wind’s transitory state in which seasons prevail over this atmospheric phenomena, because “If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?” (70). The one meteorological form ushers the next. Like the terza rima in its Ode, the Wind and the speaker are interlocked in a meteorological process that constantly develops, yet, like any meteorological phenomena, never completely alters as it is necessarily dependent on both past, present, and future form. The power of the West Wind is materially sensuous for the speaker while offering an intellectual beauty of nature that becomes a joint process in Shelley’s radical views on human life and the physical world. The emphasis on the sensuous, moreover, in such meteorological aesthesis, as we have seen, had already been a prominent feature for Shelley in his “Hymn.”

Through this aesthesis of weather, in which the speaker truly can be in sensuous connection with the “unseen Power,” Shelley positions himself against the way in which the first generation of British Romantics had conceptualized the weather. A fervent reader of Coleridge’s work, Shelley would have found his “Hymn before Sunrise, in the Vale of Chamouni” (1802) provocative in its theistic understanding of weather:

In addition to this intertextuality, Shelley’s development of an aesthetics of weather in “Hymn” was clearly shaped by his own personal experience of specific meteorological events, including his firsthand material encounter with the Alpine climate alluded to in the “Hymn.” In a letter to his friend Thomas Peacock detailing his travels around Lake Geneva with Byron, Shelley sought to convey the intense impressions made by meteorological phenomena:

We arrived at this town about seven o’clock, after a day which involved more rapid changes of atmosphere than I ever recollect to have observed before. The morning was cold and wet; then an easterly wind, and the clouds hard and high; then thunder showers, and wind shifting to every quarter; then a warm blast from the south, and summer clouds hanging over the peaks, with bright blue sky between. About half an hour after we had arrived at Evian, a few flashes of lightening came from a dark cloud, directly over head, and continued after the cloud had dispersed. (Letters 482)

The cultural-geographical context of Shelley’s weather experience is, however, also crucial for the detailed description in his letter. In fact, his aesthetics of weather in “Hymn” was an intertextual and personal response to a particularly well-documented landscape which he would have put on his itinerary quite deliberately, and, more importantly, with literary anticipation. Duffy has called the landscapes of the Alps of the early nineteenth century quintessential examples of “classic ground,” those landscapes that were common destinations of the Grand Tour itineraries, or places which were otherwise popular tourist destinations for educated travelers. The fact that these landscapes had been so well-documented and extensively written about throughout the eighteenth century, Duffy argues, means that a traveler in these places could only have experienced an “interested” as opposed to a “disinterested” aesthetics (in Kantian sense of the terms) (Landscapes 8). Shelley’s aesthetic experience of the weather of the subalpine Savoy area would have been precisely such an “interested” aesthetic; in opposition to Wordsworth and Coleridge and others like them, he sought specifically to revise the commonly held view that the climate of these particular landscapes manifested divine power.Footnote18 This was precisely the place for such an undertaking too, because as Duffy has argued, by the early nineteenth century, this Alpine region “had become the major focal point for the pious configuration of the discourse on the natural sublime” (Shelley 85). By way of his “Hymn,” Shelley offered for the popular imagination a new kind of meteorological mode of the “natural sublime” formulated in relation to his interested first-hand experience of the Alpine weather. Through a publicly shared “aesthesis” he submitted his atheistic aesthetics of weather in the “Hymn” to the benefit of the many interested travelers and readers to come. By highlighting material weather as it can be perceived, Shelley’s “Hymn” offered revolutionary knowledge to the public imagination of the “unseen Power” of the natural system contained in the inconstantly sublime mechanisms of winds, clouds, sunlight, and moonbeams—a revolutionary knowledge, however, which was meticulously formulated in a poetic form suppressed by Fröding’s translation inaccuracies.

Indeed, Fröding’s inaccuracies are doubly significant when read in relation to Shelley’s own theories with respect to the matter of poetic translation. As is well-known, in his Defence Shelley goes so far as to write that translations of poetry are sheer “vanity,” and that “it were as wise to cast a violet into a crucible that you might discover the formal principle of its colour and odour, as seek to transfuse from one language into another the creations of a poet” (656).Footnote19 Yet not even this poet’s own translations would be exempt from this precept. Valentina Varinelli has recently pointed out that Shelley’s laborious work of translating his own poetry into Italian especially contradicts his position on the matter. As she argues, Shelley made these Italian translations at the time of writing his Defence, and Italian, more so than any other language he somewhat commanded, would have had him “writing in a foreign language of which he had but an imperfect knowledge” (258). This experience, as Varinelli suggests, would have given Shelley further material on “the limits” and “potential” of language to express thought, while, at the same time, undermining the integrity of his argument about the violet in the crucible (258).

Still more revealing is Shelley’s argument on metrical innovation. If he had held true to Shelley’s own concept, Fröding ought to have abandoned, at least to some degree, the restrictive meter in his translation, in keeping with the semantics of Shelley’s weather. Such, in any case, is Shelley’s advice on translation as he theorizes it in the Defence: while he suggests that meter is “convenient and popular,” he maintains that, “it is by no means essential that a poet should accommodate his language to this traditional form” (656). Shelley, of course, would have theorized this in relation to Wordsworth and Coleridge’s disputes on the subject, with Shelley urging the poet to “innovate upon the example of his predecessors” (656). Following from this argument about innovative poetic form is also another theoretical premise of Shelley’s. Besides the debate on the possible advantages of a prescriptive metrical form, Keach has noted the way Shelley, unlike Wordsworth and Coleridge again, “freely appropriates the idea of language as dress or vestment to express his sense that the poet must inevitably articulate his conceptions in words not entirely of his own making” (26). Shelley accepts that words are expressive of thoughts even though they “can never be those thoughts” (26), Keach comments. Here lies Shelley’s reason for dismissing the necessity of metrical form, where the ideal dimension follows from this emphasis on the thought, rather than the linguistic expression of that thought. As part of his ideal argument for innovative metrical form, Shelley emphasizes the importance of what he finds in Plato to be “a harmony of thoughts” (656). Indeed, this kind of “harmony of thoughts” is more important than metrical form to Shelley’s philosophically constituted aesthetics of weather. This too explains Fröding’s failures. Whereas Shelley emphasizes the poetic value of philosophy over and above formal questions, Fröding, as we have come to see, favored what he considered the “musical” qualities of strict meter.Footnote20 Because of this insistence on meter in translating, Fröding fatally rendered Shelley’s lustrous autumnal “sky” (75) as “klarblå” ‘bright blue’ (76). But in “Hymn,” Shelley afforded no place for such overwritten literary phrases, since his was the register of an innovative poetic representation of, and engagement with, weather developed in the mode of aesthesis.

Reading “Hymn” back through Fröding, then, what we discover is precisely the fact that Shelley’s poetic expression of meteorological form constituted an aesthetics of weather. Moreover, such an aesthetics of weather was not to be defined by any cultural conventions, literary, philosophical, or political, excepting as Shelley personally conceived of them. Set “conveniently” in meter or not, for Shelley, meteorological events, seasonal changes, anticipated or sudden ruptures in the atmosphere, sunlight, moonlight, winds, clouds, and darkness possessed legislative poetic powers for the formulation of a radical aesthetics of weather in his “Hymn.” Indeed, it is the very absence of this aesthetics in Fröding’s translation of the poem which testifies so forcefully to his struggle to render Shelley’s “Hymn” faithfully.

Notes

1 All translations from Swedish are mine, unless otherwise indicated. This letter correspondence is also discussed in Sven Rinman’s 1942 article on the history of Ord och bild.

2 For example, such Chamissonian storm tropes appear in Fröding’s later poem, “Frågande svar och obesvarade frågor om ondt och godt” ‘Inquiring answers and unanswered questions about evil and good’ (1898), as well as in his more contemporary, “Uppror” ‘Rebellion’ (1892).

3 For further discussion of Fröding’s financial reasons for publishing his work, see Nordmark, Förvandlingar (ch. 1).

4 Fröding also found it particularly difficult to render Shelley’s title in Swedish, asking if his editor or Lindgren might aid him in his endeavor (see Brev 2 200). For a discussion of the title of “Hymn,” see Rosenthal.

5 The manuscript of Fröding’s “Hymn” is in the Mörner-Fröding Collection at Örebro University Library. The manuscript is a fair copy with very few emendations. For an account of the emendations concerning the published versions, see Fröding, Samlade Skrifter 224–25.

6 The OED cites Baumgarten’s definition of “aesthetics” as directly derived from the Greek origin, but Latinized as a noun designating a philosophy of the senses, extended to the meaning of “criticism of good taste.” This meaning was adopted into German and other European languages. In early-nineteenth-century British discourse, it was especially novel in its adjectival uses. Coleridge, as one of the first to employ the term as an adjective in English, felt compelled to explain in a footnote to one of his 1821 Blackwood’s articles that it could be adopted like “no other usable adjective, to express that coincidence of form, feeling, and the intellect” (234; original italics).

7 As testament to Fröding’s skill in composing verse, we find in his letters the less common story that he had in fact been sought out by one of Sweden’s most well-reputed publishers at the time, Albert Bonnier, and asked if he wanted to publish his poetry with them (see Brev 1 158).

8 For an introduction to the textual history of “Hymn,” see the commentary that Jack Donovan and Cian Duffy provide in Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley 716–18. See also Whickman’s and Westwood’s respective essays for critical readings of the two versions of “Hymn.”

9 William Keach too has argued that Shelley, in fact, “sometimes writes about language in ways that seem to anticipate ideas familiar in modern linguistic and critical theory” (xvi), finding also that Shelley’s “linguistic skepticism . . . runs throughout the Defence like a counterplot” (22).

10 In his classic study, M. H. Abrams explains that Shelley sought to combine his poetry with an intellectual commitment to natural philosophy, as he “held no commerce with the opinion that what he called ‘Science and her sister Poesy,’ need be at odds” (310). The poetics which resulted from that commitment has been, in turn, the focus of a rich body of work by critics such as Angela Leighton, Paul Hamilton, and Cian Duffy, as well as shorter studies by Evan Gottlieb, Alan Weinberg, and Paul Whickman, to only name a few. All agree on philosophy’s central role in Shelley’s writing. For Weinberg, Shelley “was among the most philosophical of English poets” (501). Whickman notes that poems like “Hymn” are now recognized as framed by “the difficult relation of Shelley’s reading of and admiration for such works [of eighteenth century philosophers], and the philosophical scepticism they offer, to his aesthetic or creative work as a poet” (145).

11 I refer here particularly to the following sections from Shelley’s early and later writings: in his “Notes” (1813) to Queen Mab, for example, Shelley paraphrases Holbach’s empirical rejection of the theistic understanding of the physical world, stating that material discoveries in astronomy are testament to the “falsehoods of religious systems” (83–84). In “On Life” (1819), he similarly praises the “most clear and vigorous” philosophy of Drummond, which leads him to conclude that even the material instrument of poetry, language itself, should be regarded with great skepticism on account of its subjective and metaphorical foundation (621–22). Likewise, in A Defence of Poetry (1821), Shelley states that “Locke, Hume, Gibbon, Voltaire, Rousseau, and their disciples, in favour of oppressed and deluded humanity are entitled to the gratitude of mankind” (672).

12 Hamilton, for instance, has argued that despite his evidently extensive “philosophical affiliations,” “Shelley’s advocacy of Holbach is still unusual and surprising” (“Literature and Philosophy” 171–73). For detailed explorations and critical readings of Shelley’s engagement with Holbach, see Duffy, Shelley, especially chapter 1, “From Religion to Revolution.”

13 My definition of the sublime here correlates to Burke’s rather than Kant’s notion of the sublime. For an extensive discussion of the “widely unexamined Kantian appropriation” (293) of readings of the sublime in eighteenth-century British discourse, see de Bolla.

14 For a cultural-historical exploration of aesthetic representations and engagements with weather in English literature and arts, see Harris.

15 For an example of readings in historical meteorology in the works of other Romantics, see McGann; and Bate. The unusual climate of the years that preceded Keats’s composition of “To Autumn” (1820) has provided material for contrary interpretations by these critics. For McGann “To Autumn” is about idealizing the true social hardships associated with poor harvests and starvation, whereas for Bate, Keats’s poem is about climate change if read accurately against historical records on meteorological conditions. For a study which extends Bate’s eco-critical theories in a reading of Shelley’s poetry, see Gidal. For an introduction to eco-critical readings of Shelley’s poetic work, see Morton, who argues, in line with his eco-critical theories, that “In the reformed worlds of Queen Mab and Prometheus Unbound, it is not just ‘as if’ nature is transformed along with political and cultural change; it really is transformed” (189).

16 See also Janković’s two monographs, Reading the Skies and Confronting the Climate.

17 Weather in Coleridge’s writings has received more critical attention than in Shelley’s. For key contributions on the topic see Reed; and McKusick.

18 For a discussion on Shelley’s atheism and the Alps, see Duffy, Introduction.

19 For a thorough study on Shelley’s work as a translator, see Webb.

20 In fact, not many years after Fröding had translated Shelley’s “Hymn” and declared his preference for measured meter, as Eva Jonsson has argued, he would adopt the Modernist conventions of free verse. For a thorough investigation of this shift in Fröding’s composition, see Jonsson.

References

- Abrams, M. H. The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1953. Print.

- Anderson, Peter. “Overhearing the Hail: A Poetics of Weather for Patrick Cullinan.” English Academy Review 25.2 (2008): 53–64. Print.

- Bate, Jonathan. “Living with the Weather.” Studies in Romanticism 35.3 (1996): 431–47. Print.

- Chamisso, Adelbert von. “Ungewitter.” Chamissos Werke. Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut, 1907. 214. Print.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “Hymn Before Sun-Rise, in the Vale of Chamouni.” The Major Works. Ed. H. J. Jackson. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. 118–20. Print.

- Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “Letter III: To Mr. Blackwood.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine 10 (Aug.–Dec. 1821): 253–55. Print.

- Davy, Humphry. Researches, Chemical and Philosophical, Chiefly Concerning Nitrous Oxide, or Dephlogisticated Nitrous Air, and Its Respiration. Bristol: Biggs and Cottle, 1800. Print.

- De Bolla, Peter. The Discourse of the Sublime: Readings in History, Aesthetics and the Subject. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989. Print.

- Downs, Brian. “Anglo-Swedish Literary Relations 1867–1900: The Fortunes of English Literature in Sweden.” The Modern Language Review 65.4 (1970): 829–52. Print.

- Duffy, Cian. Introduction. A Description of the Valley of Chamouni, in Savoy. Romantic Circles. 2018. Pars. 1–27. Web. 7 Mar. 2019.

- Duffy, Cian. The Landscapes of the Sublime, 1700–1830: Classic Ground. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Print.

- Duffy, Cian. Shelley and the Revolutionary Sublime. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005. Print.

- Engell, James. The Creative Imagination: Enlightenment to Romanticism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1981. Print.

- Ford, Thomas H. Wordsworth and the Poetics of Air. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2018. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “En litten låt ôm vårn.” Fröding, Nya Dikter 31–33.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Frågande svar och obesvarade frågor om ondt och godt.” Gralstänk. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1898. 25–45. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. Gustaf Frödings Brev 1: 1877–1891. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1981. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. Gustaf Frödings Brev 2: 1892–1910. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1982. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Hymn till den själiska skönheten.” Fröding, Nya Dikter 161–65.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Hymn till den själiska skönheten.” Nya Dikter. Birger Mörners Fröding-samling. Örebro Universitetsbibliotek. Manuscript.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Hymn till den själiska skönheten.” Ord och bild. Ed. Karl Wåhlin. Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt och Söner, 1892. 23. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Höst.” Fröding, Nya Dikter 81–82.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Höst: efter Nikolaus Lenau.” Fröding, Nya Dikter 153.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Infruset.” Fröding, Nya Dikter 140–41.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Naturalism och romantik.” Samlade Skrifter: Prosa I. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1921. 12–31. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. Nya Dikter. 2nd ed. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1894. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Oväder: efter Adelbert v. Chamisso.” Fröding, Nya Dikter 151–52.

- Fröding, Gustaf. Samlade Dikter II. Frödings Bibliotek, Uppsala Univ. Lib.

- Fröding, Gustaf. Samlade Skrifter: Nytt och gammalt; Gralstänk; Översättningar. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1919. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Uppror.” Samlade Skrifter: Efterskörd. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1921. 64. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Vackert Väder.” Guitarr och dragharmonika: Mixtum pictum på vers. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1891. 16–19. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Vinternatt.” Guitarr och dragharmonika: Mixtum pictum på vers. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1891. 116–18. Print.

- Fröding, Gustaf. “Vår.” Fröding, Nya Dikter 79–80.

- Gidal, Eric. “‘O Happy Earth! Reality of Heaven!’: Melancholy and Utopia in Romantic Climatology.” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 8.2 (2008): 74–101. Print.

- Golinski, Jan. British Weather and the Climate of Enlightenment. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2007. Print.

- Gottlieb, Evan. Romantic Realities: Speculative Realism and British Romanticism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2016. Print.

- Hamilton, Paul. “Literature and Philosophy.” The Cambridge Companion to Shelley. Ed. Timothy Morton. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006. 166–84. Print.

- Hamilton, Paul. Percy Bysshe Shelley. Tavistock: Northcote House Publishers Ltd, 2000. Print.

- Harris, Alexandra. Weatherland: Writers and Artists Under English Skies. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 2015. Print.

- Hildebrandsson, Hugo Hildebrand, Wladimir Köppen, and Georg von Neumayer. Wolken-Atlas. Atlas des Nuages. Cloud-Atlas. Moln-Atlas. Hamburg: Gustav W. Seitz Nachf., Besthorn Gebr., 1890. Print.

- Hogle, Jerrold E. Shelley’s Process: Radical Transference and the Development of His Major Works. New York: Oxford UP, 1988. Print.

- Holbach, Baron Paul Henri Thiry d’. La Système de la Nature. Amsterdam: M. M. Rey, 1770. Print.

- Hooke, Robert. Micrographia: Or, Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses: With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon. London: John Martyn, 1667. Print.

- Houze Jr., A. Robert, and Rebecca Houze. “Cloud and Weather Symbols in the Historic Language of Weather Map Plotters.” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 100.12 (2019): 423–43. Print.

- “Inkonstant.” Ordbok över svenska språket, utgiven av Svenska Akademien. Vol. 12. Lund, 1933. N. pag. Print.

- Isomaki, Richard. “Interpretation and Value in ‘Mont Blanc’ and ‘Hymn to Intellectual Beauty.’” Studies in Romanticism 30.1 (1991): 57–69. Print.

- Janković, Vladimir. Confronting the Climate: British Airs and the Making of Environmental Medicine. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. Print.

- Janković, Vladimir. “The End of Classical Meteorology, c. 1800.” The History of Meteoritics and Key Meteorite Collections: Fireballs, Falls and Finds. Ed. G. J. H. McCall, A. J. Bowden, and R. J. Howarth. London: Geological Society, 2006. 91–99. Print.

- Janković, Vladimir. Reading the Skies: A Cultural History of English Weather, 1650–1820. Chicago: Chicago UP, 2010. Print.

- Jonsson, Eva. Hospitaltidens lyrik: Textkritisk edition av Gustaf Frödings lyriska produktion dec. 1898 – mars 1905. Uppsala: Universitetstryckeriet, 2002. Print.

- Keach, William. Shelley’s Style. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016. Print.

- Knapp, John. “The Spirit of Classical Hymn in Shelley’s ‘Hymn to Intellectual Beauty.’” Style 33.1 (1999): 43–66. Print.

- Leighton, Angela. Shelley and the Sublime: An Interpretation of the Major Poems. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1984. Print.

- Lenau, Nikolaus. “Herbstgefühl.” Werke in Einem Band, Mit Dem Essay ‘Der Katarakt’ von Reinhold Schneider. Ed. Egbert Hoehl. Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe Verlag, 1966. 110. Print.

- Lindgren, Hellen. Letter to Karl Wåhlin. N.d. MS. Special Collections, Uppsala Univ. Lib.

- Lindgren, Hellen. “Percy Bysshe Shelley.” Ord och bild. Ed. Karl Wåhlin. Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt och Söner, 1892. 354–60. Print.

- McGann, Jerome. “Keats and the Historical Method in Literary Criticism.” MLN 94.5 (1979): 988–1032. Print.

- McKusick, James C. Green Writing: Romanticism and Ecology. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000. Print.

- Morton, Timothy. “Nature and Culture.” The Cambridge Companion to Shelley. Ed. T. Morton. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006. 185–207. Print.

- Nordmark, Dag. Frödings Förvandlingar: Historien om ett Författarskap. Karlstad: Gustaf Fröding-sällskapet i samarbete med Bild, text och form, 2015. Print.

- Nordmark, Dag. Pajas, politiker och moralist: Om Gustaf Frödings Tidningstexter 1885–1896. Hedemora: Gidlunds Förlag, 2010. Print.

- Reed, Arden. Romantic Weather: The Climates of Coleridge and Baudelaire. Hanover, NH: Brown UP, 1983. Print.

- Rinman, Sven. “Kring en brevsamling och en årgång.” Ord och bild. Ed. S. Rinman. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand, 1942. 9–24. Print.

- Rosenthal, Adam R. “The Gift of the Name in Shelley’s ‘Hymn to Intellectual Beauty.’” Studies in Romanticism 55.1 (2016): 29–50. Print.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “The Cloud.” Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley 420–22.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. A Defence of Poetry. Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley 651–78.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “Hymn to Intellectual Beauty.” Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley 134–39.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. The Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley. Ed. Frederick L. Jones. Vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1964. Print.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “Notes” to Queen Mab. Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley 83–105.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “Ode to the West Wind.” Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley 398–401.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “On Life.” Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley 619–23.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. “On Love.” Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley 618–19.

- Shelley, Percy Bysshe. Percy Bysshe Shelley Selected Poems and Prose. Ed. Jack Donovan and Cian Duffy. London: Penguin, 2016. Print.

- Varinelli, Valentina. “‘Accents of an Unknown Land’: Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Writings in Italian.” European Romantic Review 30.3 (2019): 255–63. Print.

- Webb, Timothy. The Violet in the Crucible: Shelley and Translation. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1976. Print.

- Weinberg, Alan. “Reading Shelley and Adorno on ‘Life’: A Further Exploration.” European Romantic Review 30.5–6 (2019): 501–17. Print.

- Westwood, Daniel. “Movement in ‘Hymn to Intellectual Beauty.’” The Wordsworth Circle 48.1 (2017): 32–39. Print.

- Whickman, Paul. “The Poet as Sage, Sage as Poet in 1816: Aesthetics and Epistemology in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘Hymn to Intellectual Beauty.’” Keats-Shelley Review 30.2 (2016): 142–54. Print.