Abstract

This article explores how prisoners plan to achieve desistance from crime. In many respects, prisoners have poor prospects upon their release. A prisoner’s chances of reintegration can be hindered by conditions such as structural barriers, lack of social support, and the after-effects of imprisonment. Using qualitative interviews with prisoners (N = 45) who were serving at open low-security prisons in Finland, this analysis demonstrates that the majority of the prisoners had optimistic expectations and devised concrete plans for desistance. To achieve this desired change, the prisoners intended to use three self-regulating strategies; to secure employment or another daily routine, to seek help from others, and to shift surroundings. Even if work, support, and solitude are viable strategies for achieving desistance from crime, this article recognizes the risk of these self-regulating strategies failing due to inherent uncertainties and weak implementation intentions.

Introduction

Within the field of desistance research, the importance of expectations in achieving desistance has attracted increasing attention in recent years. Prisoners’ desistance expectations have generated particular interest, indicating that a vast majority of prisoners assess their chances for desistance as good (Dhami et al., Citation2006; Kivivuori & Linderborg, Citation2010) and that a prisoner’s positive outlook for the future may be connected to actual desistance (Burnett & Maruna, Citation2004; Doekhie et al., Citation2017; Kivivuori et al., Citation2012; Souza et al., Citation2015). When examining recidivism rates, a somewhat different picture emerges. There is clearly a gap between prerelease desistance optimism and post-release reality.

Researchers have found that optimistic desistance expectations are closely intertwined with other changes that prisoners aspire to, and these expectations are often framed as aspirations for creating a conventional life (Doekhie & Van Ginneken, Citation2020; Shapland & Bottoms, Citation2011). The wish to rebuild one’s life according to conventional goals and values is important to both desisters and persisters, however, indicating that harboring dreams and making plans for a “normal life” are not sufficient to achieve it (Doekhie & Van Ginneken, Citation2020; Liem & Richardson, Citation2014; Shapland & Bottoms, Citation2011). The lack of realistic and specified planning can, together with structural barriers and perceived obstacles, stand in the way of making reentry plans come through (Bottoms & Shapland, Citation2011; Farrall et al., Citation2014).

Motivation theories stress that a clearly formulated goal needs to be accompanied with motivation and self-regulation in order to be attainable. This article approaches prerelease expectations from this motivational aspect, not solely focusing on what prisoners wish to accomplish, but how. Doekhie and Van Ginneken advocate for distinguishing between goals and pathways when studying desistance expectations, arguing that “concrete pathways and scripts to realize conventional aspirations and possible selves are more important in explaining desistance” (Citation2020, p. 757). Following this line of argument, this article explores the expectations of Finnish prisoners prior to their release, searching for the strategies prisoners use to outline their future.

From a narrative perspective, prerelease expectation can be understood as antecedent to behavior (see Presser, Citation2009). Speech is not understood as less important than action; rather, stories are analyzed as action, considering that narratives are largely constructed through shared formats (Sandberg, Citation2010). As observed by Maruna (Citation2001), offenders using a redemptive narrative, connecting their negative pasts experiences with more positive futures, were most successful in desisting from crime. Acknowledging that personal narratives matter, this article discusses the self-regulating strategies prisoners plan to perform to achieve desistance from crime. Even if prisoners are optimistic and motivated about their desistance prior to release, their prerelease expectations are not likely to endure unless they are supported by self-regulated implementation intentions.

Building on qualitative interviews with 45 prisoners serving in Finnish open prisons, the aim of this article is to explore the prerelease expectations of soon-to-be-released prisoners, and the subjective and social considerations underlying these expectations. Although prisoners’ prerelease desistance expectations involve the problem of false positives, they nevertheless depict how prisoners aim to achieve desistance, and thereby offer a generous insight into the variable pathways along which prisoners approach their desistance process. The narrative accounts of how prisoners are planning to achieve desistance are not solely to be understood as a basis for measuring recidivism. Prisoners’ prerelease expectations themselves offer important insights into how prisoners envision, negotiate, and undertake desistance in their transition from prison to community.

The Finnish context

Finland has a prison population of approximately 3,000 prisoners (Criminal Sanctions Agency, Citation2020b), and a prisoner rate of 53 prisoners per 100,000 of the national population. The vision of the Finnish prison system is to ensure a safe enforcement of sanctions and to reduce recidivism by “preparing for a life without crime” (Criminal Sanctions Agency, Citation2020a). In doing so, the Finnish Criminal Sanctions Agency aims at more open sentences, both in terms of punishment overall and during individual prison terms. Prisoners with a sentence shorter than two years can serve their sentence entirely in an open prison, while prisoners from closed prisons may apply for transfer to an open prison toward the end of their sentence (Finnish Imprisonment Act, 2005, 4 §8).

For many Finnish prisoners, an important step in their release process is to serve some part of the prison sentence in an open low-security prison. The open prison aims at facilitating rehabilitation and reintegration upon release more effectively than is possible in closed high-security prisons. Open prisons in Finland allow prisoners to move within their unit, workplace, and other activity spaces without immediate supervision (Finnish Imprisonment Act, 2005, 4 §1). Social support from the welfare state and civil society is heavily present in Finnish open prisons. The more open prison environment is assumed to affect prisoners positively and prepare them for release and a life without crime. Research on low-security prisons is however scarce, especially concerning whether this type of prison can have a positive effect on reintegration and desistance.

Motivation and action

Motivation theories attempt to explain how people move from motivation to action. Two factors are central in determining how people choose to act: their striving for control and how they organize their goal engagement (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, Citation2008). The process of organizing and prioritizing one’s goals and motivation not only involves individual effort but is intrinsically determined by the individual’s situation. The situation poses opportunities and constraints that function as incentives for the individual to act upon (Beckmann & Heckhausen, Citation2008). For a prisoner reentering society, structural barriers are undeniably constraining the possibilities and probabilities for reaching the desirable goal (Bottoms & Shapland, Citation2011).

In order for a goal to be worth attaining, it must be possible to anticipate the existence of the goal state. In addition, the goal state must have some subjective significance for the individual (Beckmann & Heckhausen, Citation2008). In moving from motivation to action, volition—or will—can be profoundly important. Volition is the process in which the individual decides which motivations to implement, and in what manner (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, Citation2008). Volition thus clarifies one’s motivations. It is important to note that individuals differ in their ability to regulate volition and motivation, depending on their level of self-regulation (Kuhl, Citation2008). Self-regulation here refers to the psychological regulation that the individual needs to do when the realization of intended action is threatened by internal or external barriers (Beckmann, Citation2001). Self-regulation can take the form of self-monitoring, management of emotions, planning, and decision-making, and it functions as a supplementary action to support motivation, when this alone may not prove sufficient to achieve the wished-for goal (Beckmann, Citation2001).

Gollwitzer (Citation1999) emphasizes that an individual’s self-regulatory skills are essential for a goal to be effective. Formulating implementation intentions, in the form of if-then plans, increases the probability of attaining individual goals. Implementation intentions specify when, where, and how a goal is to be attained and thus cognitively tie behavior to the situation of striving to meet the goal. Strong goals have been found to be realized more often than those never formulated at all (Ajzen, Citation1991). The correlation between intention and behavior is modest, however, and past behavior commonly predicts more than current intentions (Gollwitzer, Citation1999). One can assume, that implementation intentions become particularly important for prisoners reentering society, as the structural barriers they encounter after release are considerable. This aligns with findings from desistance research, stating that the hope of change characterizes the early phase of desistance, while more-developed aspirations take form as the desistance journey progresses (Farrall et al., Citation2014). One considerable challenge for desistance supportive practice is therefore to strengthen prisoners’ implementation intentions, making the desistance optimism something more than hope (McNeill & Weaver, Citation2010).

Desistance expectations

Desistance theory recognizes the importance of motivation and volition in achieving desistance from crime. Psychological desistance theories, such as the theory of cognitive transformation (Giordano et al., Citation2002) and identity theory of desistance (Paternoster & Bushway, Citation2009), acknowledge individual decisions and cognitive development as prerequisites for changes in offending behavior. In contrast, ontological and sociological theories place more significance on maturing (Moffitt, Citation1993), social bonds, and social control (Farrall & Bowling, Citation1999; Sampson & Laub, Citation1993, Citation2003). Within psychological theories of desistance, motivation is understood intrinsically, meaning that the behavioral change is motivated by internal desires (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). Further, much of desistance theory acknowledges that desistance is a process rather than an event. The process perspective allows desistance to be understood in a way that embraces individual, structural, social, and relational change over time. In line with this, Graham and McNeill (Citation2017, p. 435) propose a conceptualization of desistance “as a dynamic process of human development—one that is situated in and profoundly affected by its social contexts—in which persons move away from offending and towards social re/integration.”

Following the psychological reasoning on motivation, desistance expectations can be essential for actual desistance; having hope for one’s future appears to be central to achieving it. A handful of researchers have examined the association between expected and actual offending. One of the more influential longitudinal studies in the field, the British Dynamics of Recidivism study, looked at 130 male medium-risk offenders with follow-up interviews conducted two and ten years after their release from prison (Burnett, Citation1993; Burnett & Maruna, Citation2004). The researchers noticed a clear coherency between prerelease predictions and self-reported crime after two and ten years. They found that the level of optimism and self-perceived control correlated with desistance. Building on this research, LeBel et al. (Citation2008) report that the most influential factor for desistance is the prisoners’ view of themselves. Those prisoners who were most likely to desist had, besides few problems facing them upon release, developed new identities, for example as fathers. In contrast, those who felt stigmatized or powerless were at greatest risk of reoffending and returning to prison.

Cross-sectional studies on the same topic have mainly focused on describing desistance expectations and ascertaining the reasons for desistance optimism (Cobbina & Bender, Citation2012; Dhami et al., Citation2006; Doekhie et al., Citation2017; Kivivuori & Linderborg, Citation2010; Schaefer, Citation2016; Visher & Connell, Citation2012). Descriptive studies have also examined gender differences (Friestad & Skog Hansen, Citation2010) and variations in partner expectations for desistance (Souza et al., Citation2015). The importance of desistance optimism has also been supported by Kivivuori et al. (Citation2012), who report how self-assessed reoffending, estimated during incarceration, predicted post-release crime, measured by a subsequent criminal record. The researchers concluded that measures of reoffending probability are useful in predicting recidivism even when false positives are considerable, particularly as desistance optimism may be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Methods

This article is based on data from 45 qualitative semi-structured interviews with prisoners at low-security prisons in Finland. This constitutes the first part of a longitudinal study on release from prison and desistance from crime. The interviews explored prisoners’ thoughts regarding their future offending and general plans upon release. The participants were asked to assess their chances of committing crimes again, and to give reasons for their assessments. Further, they were asked about their future plans and hopes, both shorter and longer term, and whether this release from prison differed at all from any earlier releases. The interviewees were approached as agentic and rational agents. This approach is reflected in the finding that participants predominantly focus on their own responsibility for achieving desistance. The agentic focus in the interviews presumably contributed to prisoners being less able to reflect on the structural aspects of their desistance process. The study was evaluated and granted a research permit by the Finnish Criminal Sanctions Agency.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted during spring 2019, at five medium-size low-security prisons holding about 80 prisoners each. The participants were recruited during a one-to-two week visit at each prison, where the researcher presented the research project to potential participants and conducted the interviews. Prior to the visit, prison officers had informed prisoners about the research project, either orally or in writing. The criteria for participation were that the prisoner had less than three months until release (or until early release with electronic monitoring), was reintegrating to the Finnish society, and had a history of repeat offending. Prison governors provided the researcher with a list of participants meeting the inclusion criteria, and prison officers assisted the researcher in contacting the potential participants. When meeting the potential participants face to face, the researcher stressed that participation was voluntary and building on informed consent. The eligible participants were explained that the interview would concern their release from prison, with an interest in their expectations and preparations for their release. 45 prisoners consented to be interviewed, and the interviews were held in meeting rooms suitable for confidential conversations, without any presence of prison officers. The interviews lasted, on average, for 45 min. All but two of the interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The author conducted and transcribed all interviews, and translated the quotes from interviewees cited in this article. The names of the interviewees have been changed to typical Finnish names to protect the anonymity of interviewees.

The co-operation with the prison staff in the initial phase of the recruitment process might have biased the sample, as the researcher was not able to control how or by whom the research project initially was presented to the prisoners. One example of possible sample bias concerns ethnicity. At one of the research sites, members of a specific ethnic group were consistently reluctant to participate. Such a response did not occur in any other prisons. Misconceptions concerning the role of the researcher might have been present even if the independence of the researcher was repeatedly stressed. The co-operation with the prison staff was, on the other hand, beneficial in securing a broad sampling, as it enabled the inclusion of prisoners who were less visible in the daily life of the open prison, for example, because of having work outside of the prison grounds. The personality and gender of the interviewer, circumstances of the interview, and institutional context, are additional factors likely to have affected who participated and how they communicated in the interviews.

Sample characteristics

Basic background information on the participants was gathered during the interviews. On average, the participants had 72 days until their release. Including the time until their early release with electronic monitoring would begin, the average was 43 days. Thirteen participants were serving their first prison sentence, but many of these had prior experience of other penalties, such as community sanctions or fines. The criminal background of the participants was diverse, as was the main offense for the prison sentence: offenses against property (N = 14), offenses against life and health (N = 12), traffic offenses (N = 9), drug offenses (N = 9), and offenses against public authority (N = 1). The length of the prison sentences varied from 2 months to 14 years, and the participants were between 22 and 54 years old, with an average age of 39. Of the 45 persons who agreed to participate, four were women. The fact that only one of the selected research sites held female prisoners accounts for the disproportionate share of women in the data. Nevertheless, this obviously low number of women corresponds to the proportion of women in Finnish prisons. The women are included in the sample in line with men, as gender not was seen as reason enough for the excluding women’s perspective on release and desistance from this report.

For this study, interviews were only conducted at open prisons, so it does not give a representative picture of all Finnish prisoners. Instead, it covers a sample of prisoners who have received more structural support and therefore might be better able to pursue desistance. One can assume that the clientele of an open prison has more reason to be desistance optimistic; these prisoners are generally serving shorter sentences, comply with prison rules, and are desistance motivated. The broad diversity in the types of offenses the prisoners committed and differences in their sentence lengths pose a serious challenge for theorization. With open enforcement and criminal careers as common denominators, however, the sample is considered usable for theoretical generalization; the findings may be applicable beyond the immediate research setting (Lewis & Ritchie, Citation2003).

Analysis

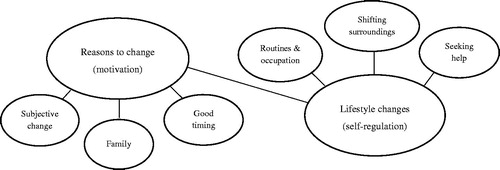

In order to meet the research goals—to explore the strategies prisoners have for their desistance processes upon release—thematic analysis, with its potential for qualifying descriptions and interpretations, was a suitable choice. Thematic analysis is appropriate for identifying, analyzing and describing patterns within the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Vaismoradi et al., Citation2013). The thematic analysis was approached as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). All interviews were initially read through several times to enhance familiarity with the data. After an inductive open coding of the material in Atlas.ti, relevant codes were sorted and assembled into meaningful groups. The coding was inductive, without any pre-determined codes. The codes were then assembled into a thematic map, as shown in , which was further revised in relation to the whole data set to ensure that the themes corresponded to the data as a whole. The further the analytical process developed, concepts from motivational theory and desistance theory—like volition, motivation, self-regulation, and “hooks of change”—were used for interpreting the themes.

Findings

In their prerelease desistance expectations, prisoners clearly distinguished between the reasons to change and the planned or accomplished lifestyle changes that were a part of this transformation (see ). Here, the focus will be on the three types of lifestyle changes that the prisoners mentioned when talking about their aims to desist from crime: to get employed or find other daily routines, to seek help from others, and to shift surroundings. Theoretically, these lifestyle changes are understood as self-regulating strategies. Cognitive processes are also an important part of self-regulation, in addition to practical and concrete forms of self-regulative behavior (Beckmann, Citation2001). It was not possible to address any internal processes of self-regulation based on the empirical material, and the focus will therefore be on the concrete and practical strategies that the prisoners mentioned. The motivations behind these strategies—subjective change, family, and good timing—provide a background for the analysis, showing how both subjective, relational, and situational aspects motivate prisoners in their plan making.

In line with previous research on desistance expectation, the vast majority of the prisoners in the study (N = 39) were optimistic that they would succeed in desisting from crime upon release. The distinction between those who were desistance optimistic, and those who were not, was not clear-cut. A large number of optimistic informants had a hidden reservation about not going straight, as one can “never say never.” To some, this appeared to be a rhetorical strategy that was adopted in advance as neutralization and was learned from earlier mistakes. Prisoners that were uncertain about their future have been included in this analysis, as, despite their hesitation, they reveal important knowledge about how prisoners attempt desistance at different stages in their criminal careers. As emphasized by the desistance literature, desistance should not be understood only as the cessation of crime, but more generally as the process through which offending is of lesser gravity and decreasing in number and pace (Kazemian, Citation2007). The veracity of the expectations is not as interesting as how they reflect and help us to understand the values, identity, cultures, and communities behind them (Sandberg, Citation2010).

Next, the three strategies of self-regulation—work, support, and solitude—that emerged in prisoners’ narratives about their prerelease desistance expectations will be presented. Lastly, the discussion will focus on the prisoners who lacked motivation and plans for how to achieve their desistance, and on how they differentiate from the other prisoners.

Work

When planning how to steer clear of committing crimes again, many prisoners talked about the need to self-regulate their actions in their daily lives. Some had plans to return to their old workplace or to education (n = 15), while others (n = 5) had managed to arrange a new job during imprisonment. Prior to release, employment or education was still only a plan or an imaginative idea for many prisoners (n = 12). Regardless of the forecasts, interviewees repeatedly mentioned being employed or having other daily routines as a necessity for achieving the anticipated desistance. These answers echo classic desistance theory, recounting the importance of having something to do and earning a living for achieving desistance from crime (Sampson & Laub, Citation1993; Uggen & Wakefield, Citation2008). Even if the prisoners generally viewed the desistance process as a subjective undertaking, driven by their personal change, they still largely relied on structures to prevail.

A salient theme that arose in the accounts on employment concerned the self-respect and control that the prisoners hoped to gain through work. As noticed in motivation theory, striving for control is central for how people choose to act. Among the interviewees, striving for control was often connected to the prospect of earning a living and coping on the earned income. This was the case for Samuli who, after some years outside the labor market, was building up his life again:

then I can pay all the rent myself, and all other expenses that come. I don’t have to go anywhere to ask for help and that’s a big thing for me, that I can make it completely on my own. (Samuli)

Samuli’s account also illustrates how getting a job can be closely connected to the desire for autonomy. Autonomy has been discussed as a central aspect of the desistance process, and especially the aspect of being able to formulate and realize one’s own goals (Laws & Ward, Citation2011). In this material, autonomy was most clearly linked to the economic independence offered by employment and not having to be a burden for others.

For many of the interviewees, having work or another daily routine was a goal in itself, and not only a means for desistance. Those who were returning to their workplace were especially invested in their work and genuinely eager to go back. Even if employment had not hindered them from committing crime before, they still saw it as a possible “hook for change” (Giordano et al., Citation2002, p. 992) this time. This was the case for Markus, who had been working in constructions prior to imprisonment, and helping out at the family farm. When asking what he wished for upon release, he quickly mentioned work:

I’ll contact the employer right away to see what the situation ’s like, when I can start. I also need to fit the farming and the paid work together again. And if I can’t start at any construction site at once, then I’ll just go to the employment service agency to find something. (Markus)

Markus’ attitude to work highlights how work not was considered only a one-off hook for change but as an institution that continuously would promote integration.

Insights from motivation theory suggest that desistance projects should not only be framed preventively as the end of offending, but rather through desired promotion goals that can replace some of the emotional, social, and practical functions that crime signified to the individual. Without promotion goals, the possible negative outcomes of the desistance process can become dominant and undermine the process itself (Nugent & Schinkel, Citation2016). Antero was one of the prisoners, who talked about work as something he wanted rather than needed. To him, work created necessary structures for the life and delimited the leisure time:

I don’t have to work. I live cheap, so for living I don’t need to work. But it’s nice to work. What would I do if I didn’t work? Enough money for flying isn’t there anyway. A job brings with it regularity and…well, I don’t know what I’d do if I didn’t work. (Antero)

Several prisoners mentioned that the allurement of crime was linked to leisure time. Having routines and something to do was therefore of utmost importance. As explained by Jarkko: “When you know that you need to show up on Monday morning, you don’t let the weekend get out of control. You need to take it quietly and prepare for the workweek.” To have workplace was hence desired both in itself and as a means of self-regulation.

Some of the interviewees had work-life experiences that were the very opposite of desistance supportive. The negative experiences were mainly linked to work-life stress, which in turn had been conducive for crimes committed. In order for work to have a positive impact on the desistance process, the interviewees recognized the need for a healthy balance between work and leisure time. As described by Juho and Ilmari:

The greatest challenge [when released] is probably to give my self time to just live. Usually, my sober periods have failed because of me working so much that I havn’t seen any other way out than starting using drugs again. (Juho)

Last time I burned myself out because of work. I did long days at work, with both relationships and other things suffering. But now I have made clear rules, I’m gonna work from 8 to 4, that’s the shift. […] I’m like really proud, and thankful to my friend, that the workplace is still there and that I can return to the work that I did before. But now I’m gonna put my own health and my relationships before work. (Ilmari)

Both Juho and Ilmari planned to go back to work and highlighted work as an important aspect of their desistance process. They were however realistic about the fragility of the self-regulating strategy chosen.

Support

The prisoners mentioned their readiness to seek help and support from others as a second possible self-regulating strategy for achieving desistance from crime. One can understand this psychosocial self-regulating strategy as a practical implementation strategy, but also more broadly as a general attitude of knowing and admitting one’s own limitations. Most interviewees planning to utilize this strategy linked it to a subjective change that they had undergone. This subjective change often came as a response to being tired of their criminal lifestyle and wanting something else in their life; “…one want’s more from life than just sitting behind these bars” (Samuli). To some, the prison sentence functioned as a wake-up call and gave them time and a reason to review and recalibrate the type of life they would want to live. The subjective changes that the interviewees accounted for concerned gained self-confidence, greater perseverance, acceptance of punishment, honesty toward themselves and others, and readiness to seek help. The interviewees explained that especially the readiness to seek help was a substantial change in their lives, as previously they had viewed seeking help and opening up to others as a weakness. Tuomo was one interviewee that had condemned others seeking help, but then experienced its benefits, and saw this as a strategy for his future:

Previously, if I got into trouble, I just had to make a call and the trouble was taken care of. Nowadays I have to fix things myself. Like money trouble and everything like that. […] I was in [a closed] prison and I got to speak to the correctional counselor. And I went to talk with him/her on six occasions, six long conversations. And I noticed that it did help, actually. […] And, I’d say it’s up to the prisoner, do you wanna open up to someone unknown or not? Like I’ve always been, that I don’t tell anyone anything, hell no, that’s my business. But during this sentence, I’ve talked… and I’ve noticed that it has helped. To some extent. Well, maybe my life situation is so different this time. Before, if they had talked to me, there would have been a death next, damn it. So… [laughs] kind of different situation. (Tuomo)

Researchers have shown that institutional settings and cultural characteristics are likely to affect readiness to seek help (Vogel et al., Citation2007). Typically, neither criminal culture nor prisons are settings prone to promote a culture of help-seeking. Opening up to others can therefore be seen as an important social and psychological shift in the desistance process.

The opportunities for family contact in prison was another reason for the change. Although the prisoners attributed their subjective change and shift toward help-seeking largely to their own thinking process, psychosocial support from both family and professionals had played an influential role. Several of the interviewees talked about how during their sentence they had started having visits from or visiting their children, and how this gave them a reason to be optimistic concerning their future. As described by Samuli:

Now [during imprisonment] I’ve started meeting regularly with all of my kids. Every month I get to go for a leave and visit them. That’s really good, cause I’ve had many years when I didn’t meet them. And all that just added to the depression, like, it gave you another reason to drink, which then worsened the chances of seeing them when I constantly was so drunk. I wasn’t capable of being a dad. It became like an unending…But now I have started gaining back some trust with their mothers. (Samuli)

Many Finnish open low-security prisons heavily promote family contact, for example through extended visits, “family houses,” regular leave, and mobile phones in prison. Here, the open prison presumably can play an important role in inspiring and sustaining motivations to desist from crime.

Psychological help from professionals in prison was mentioned as another fundamental reason for change. The prisoners interviewed in this study were in many aspects critical to the management of the open prisons they served at, but considering the access to social and psychological services, most prisoners perceived it to be substantially better than in closed prisons. As for example described by Ilmari, the help and support from staff was usually only a question away:

Being here, I’ve learned to talk, to open up about things, and not keeping them inside. So if I start worrying about something or just need to talk, then I’ve learned that I can just pull somebody’s sleeve, someone from the staff, and “I’d like to talk.” (Ilmari)

The psychological services offered in prison were considered helpful in many aspects, also concerning the desistance process:

And, all these things that I’ve never been willing to deal with before, now I’ve been through them all with the psychologist. And it really have helped. If one would have understood that earlier, like to make use of these psychology services and all, it probably wouldn’t have been this many relapses (Samuli)

In addition to supporting the prisoner during imprisonment, the psychosocial work seemed to inspire the individuals to seek similar support after prison. Ilmari was one of the prisoners who underlined the necessity of psychosocial support after release. He recognized the need to seek professional help for some of the problems that prisoners can face upon release, rather than relying only on the social surroundings, friends, and families:

I would say that I’ve really turned myself around. The way I nowadays think about things, how I’m able to talk about them, that I no longer need to pile them up in my head… I don’t need to worry on my own now that I can talk to others. And I know that I have, like if something was to happen, then I have the opportunity for example to go to the [prisoner NGO] and talk, so that it’s not only, that you not only talk about it with friends or your partner, but that you also get professional help with it if needed. (Ilmari)

Even if prisoners envisioned some problems that they might encounter upon release, they are still highly likely to face many more unforeseen structural and social challenges. How they handle these thresholds is critical, as the desistance process is a fragile project, in practical, emotional, and many other terms (Halsey et al., Citation2017). Prisoners who base their desistance process on seeking help from supportive environments have an advantage as, besides concrete support, they can benefit more generally from the societal inclusion that this openness toward others might create.

Solitude

Lastly, several of the prisoners planned to shift their physical and social surroundings to ensure that their desistance optimism would become reality. Some of the informants had deliberately planned to change city or neighborhood, while others had radically delimited who they were in contact with. Both these approaches demonstrate how social self-regulation can function as a rational strategy for achieving desistance. For some of the prisoners, this shift in surroundings was extremely extensive. This was the case for Juho, who chose to delimit his social surroundings drastically and change his place of residence:

most of my friends either use or sell. So, if I’m gonna stay out of drugs that means I have to start again from scratch. When I cleaned up my phone numbers, I think I was left with 12 numbers. That’s how few people in my life that’s not connected to drugs, either by selling or buying or both. And I mean, if I’m gonna give up crime and stay out [of prison] it also means I have to give up these people. Combining those two, that’s not possible, at least not to me. I know myself that well, that doesn’t work. (Juho)

The informants clearly linked the strategy of shifting surroundings to their desistance ambitions. By identifying people, places, and situations that could present a challenge to their attempt to stay away from crime, they specified individual prerequisites for a successful desistance process. To some, like Juho above, the required changes were drastic; to others, it was more a question of alertness to one’s social surroundings. Such alertness could be implemented by avoiding specific restaurants or districts, or refraining from answering the phone when certain people called. Several prisoners had told their previous friends and partners in crime about their wish to change, as they hoped that this would help them to stay disconnected from their former lives.

Despite the risk of becoming lonely, many informants deliberately sought to scale down their social lives. Many mentioned, like Juho, that this was needed to prevent him from engaging in crime. Others deliberately wished for smaller social settings. Nugent and Schinkel (Citation2016) recognized this social isolation as one of the pains of desistance, when prisoners both wanted and needed to isolate themselves in order to avoid crime. This type of isolation was also a foreseen factor in the desistance process in the interview data for this study. Solitude was something deliberately chosen, and in some cases, even longed for. This was exemplified by Kristian, who wanted to lead a calmer life after release from prison:

It will probably be a rather peaceful and quiet life. Mostly concentrating on being at home and in the small circle of family and friends, I think. […] …my life before was such that I had to be running around all the time. Now it’s the opposite, now I just wanna have it calm and I don’t see any need for running around everywhere, stressing out… Just like you’d miss out on something if you’re not there. So that has changed. (Kristian)

The shift in social surroundings was to some of the prisoners perceived as both desirable and necessary for achieving desistance. A voluntary choice of solitude like the one described by Kristian can also be understood as an effect of imprisonment, a custom of the prison culture taken on by the prisoner (Clemmer, Citation1958). Even so, the risks and harmful consequences of isolation must be articulated. It however seemed like the interviewees planning to adopt this self-regulating strategy calculated the social costs of shifting surroundings and were ready to endure the pain of isolation in order to achieve desistance from crime. As commented by Sakari:

…right now it doesn’t feel like a problem [to leave old friends]. But then again, here you get to be social all the time, it’s another thing when you’re released and you don’t have anyone. Then you get lonely quite quickly. (Sakari)

The prisoners seemed at least somewhat prepared for the possible pains that would follow the change in social surroundings. The motivation of desisting from crime counted for more. As Kristian formulated it, one just needs to “focus on the small things in life and concentrate on the life at home.”

Absence of self-regulating strategies

Some prisoners interviewed did not have any strategy for achieving desistance (N = 9). This group consisted both of prisoners who did not believe they would or could desist from crime and of prisoners being desistance optimistic. The latter prisoners expressed a hope or wish for desistance but had no concrete plans for how this change would occur. They just wanted to get back to the life they lived prior to imprisonment. One typical example was Jari, who neither had an income nor a place to live upon release, but still hoped for things to solve as time passes:

I haven’t made any greater plans. I’m gonna serve the time I have to serve and not gonna… it’ll show in spring, when I get out of here, maybe the summer will show some new things. (Jari)

The precariousness of hopes and plans that lack a subjective grounding is clearly emphasized in the theory of intrinsic motivation, noting that a goal needs to be of subjective significance to an individual in order to be worth pursuing (Beckmann & Heckhausen, Citation2008).

The reasons for not having planned or adopted any self-regulating strategies varied. Firstly, there were several of the prisoners that had upcoming sentences and therefore were particularly hesitant to formulate plans that they knew were impossible to keep for a longer time. This was the case for Petri. He was desistance optimistic, but mentioned how upcoming sentences hindered him from making any plans and changes in his life:

The upcoming sentence doesn’t help the situation at all. It’s just like this high threshold, hindering me from getting my family life in order and all such. And no plans can be made because basically all revolve around the sentence and how long it will be. […] I’ve got a well-paid work, but… But the employer wants me to get all the sentences dealt with and away so that I can start from a clean slate, with nothing upcoming. (Petri)

Others had disappointed themselves so many times that they were hesitant to plan. Like Petteri who, when asked if he had any expectations or plans upon release, replied that “I must confess, I don’t. Not really. In a way that depresses me, but I’m also totally fine with having it that way. That way you don’t get any disappointed expectations in any direction.” The same kind of hopelessness and indifference was present when Jaakko talked about his future, describing his situation like a rat race.

Yeah, it’d be nice [to find paid work], but then again… the bailiff comes and takes it all away. So it’ll have to be something more informal, finding the workplaces through contacts so that you’re actually left with something. And that’s the reason why financial difficulties makes me commit these crimes. That’s the goddamn problem […] it’s like a rat race. (Petteri)

Lastly, some of the prisoners considered themselves innocent and wrongly sentenced. As these informants did not perceive themselves as having committed a crime, consequently they did not see themselves as able to desist from it. As Heikki put it: “How can I desist from crime if I don’t see myself as having even committed a crime?”

These prisoners remained optimistic about not committing crimes but acknowledged the risk of being arrested and sanctioned, as they viewed the criminal justice system as a game of chance. Linked to this, Mika pointed to the fact that once labeled as a criminal, the chances of breaking free have become slim and somewhat out of his control. The criminal justice system remembers his past like was it an identity:

usually, these lables that you get when having been in prison or being accused of doing something… it doesn’t go away, like, it always follows what is written in the papers. Even if it shouldn’t, it can affect everything. (Mika)

The reasons for prisoners’ absence of self-regulating strategies not only varied but more importantly, they highlight some of the structural barriers for reintegration that prisoners encounter. Debts, long waiting times for upcoming sentences, and stigmatization of former prisoners were some of the most obvious barriers mentioned; barriers hindering prisoners from making and implementing their plans of desistance.

Discussion

This article contributes to our knowledge about how prisoners prior to release plan to achieve desistance from crime. The majority of the prisoners interviewed in this study formulated their desistance expectations as optimistic, consisting of a hope or an aim to desist from criminal activity. The prisoners planned to employ three different strategies for achieving their desistance plans; to get employed or find other daily routines, to seek help from others, and to shift surroundings. The three self-regulating strategies are not a comprehensive list but indicate what the prisoners in this study felt to be the necessary means for desisting from crime. A small group of prisoners did not have any specified strategy for achieving desistance, mostly because they had upcoming sentences or felt wrongly sentenced. The lack of desistance ambitions and self-regulating strategies indicates that these prisoners were likely to persist in their offending.

The prisoners interviewed for this study consider subjective change as the most decisive factor in their successful desistance process. This is in line with much of the desistance theory that lists subjective readiness combined with a sense of agency as the most essential piece in the desistance puzzle (Liem & Richardson, Citation2014; Maruna, Citation2001). The subjective significance of a goal and concrete implementation intentions are also essential to making plans reality (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, Citation2008; Gollwitzer, Citation1999). However, when prisoners base their motivation for desistance optimism on subjective change, the change is difficult to delineate, both theoretically and empirically. What exactly this subjective change means, and what type of change is required, remains underdeveloped in the desistance literature. In this material, an apparent feature of subjective change was the readiness to seek help. This highlights openness to support as one significant aspect of subjective change, a finding worth further study.

The results presented here must be understood in the context of open low-security prisons in Finland. Like all prisons, open prisons have far-reaching and damaging consequences on their prisoners, psychologically, physically, and socially. The analysis has however demonstrated that open prisons’ investment in promoting family contact seems to affect desistance optimism positively and provide useful means for reintegration. Likewise, the therapeutic services and psychosocial work in prisons are portrayed as important in preparing for release and in promoting help-seeking after release. Open low-security prisons encourage prisoners to actively plan and prepare for their release, aiding them in job seeking, training, and education. Despite the potential for promoting desistance through family work, psychosocial efforts, and strengthening of prisoners’ attachment to work in open prisons, many prisoners forecast social and structural challenges upon release.

When prisoners mention work, support, and solitude as decisive for their desistance process, it reflects the structural circumstances that prisoners face upon reintegration. Albeit framed as individual undertakings, one can interpret prisoners’ forecasted self-regulating strategies as areas of life where they expect social and structural challenges. To secure employment, manage emotional strain, and integrate socially, are all difficult but well-known challenges in prisoners’ reintegration process.

Recidivism rates indicate that the self-regulating strategies proposed in this study will prove insufficient in achieving desistance. The analysis has presented two factors explaining the gap between prerelease desistance optimism and post-release outcome. Firstly, the self-regulation strategies themselves carry inherent risks; work can become too much work, solitude can turn into loneliness, and relying on support from others makes oneself vulnerable. Secondly, prisoners’ implementation intentions (if-then-plans) for how to desist from crime varies greatly. The more advanced implementation intentions articulated in this study included several self-regulating strategies and acknowledged both social and structural factors of the desistance process, while the less developed intentions rested on a simple hope or single strategy. Articulating an implementation strategy for one’s desistance process is important, as aspirations that are specified, possible to anticipate, and at an attainable distance from the current situation, have better chances of realization (Beckmann & Heckhausen, Citation2008; Genicot & Ray, Citation2017). Herein lies much of the fragility of prisoner’s desistance projects. Many prisoners frame their desistance ambitions as being stories of subjective choice, while their practical plans of self-regulation indicate that they are intrinsically dependent on circumstances and other people. When any of those circumstances or people fail, the plans of self-regulation risk falling short.

Limitations

Although this article has furthered knowledge on desistance expectations, it is not without limitations. Desistance literature has been criticized for not critically examining the concept of crime (Graham & McNeill, Citation2017). This article unfortunately follows the same pattern. Official views of crime have been reproduced in the interview guide and therefore likewise in much of the material. Few prisoners in the data challenged the understanding of crime; the exceptions, such as prisoners who deny having committed a crime, are not problematized in detail in this article, even though these issues warrant further study. This also applies to the structural understanding of contexts that affect desistance from crime. This article has a clear subjective focus on an individual’s desistance process; whereas the importance of situational and structural contexts are acknowledged, they are not adequately considered. The effect of larger structural contexts such as gender, class, and ethnicity has only been indirectly recognized in the analysis. The analysis was further unable to capture the emotional and cognitive aspects of self-regulation. The exclusion of these essential parts of self-regulation have weakened the analysis and simplified the understanding of desistance.

Another limitation concerns the diversity of the sample interviewed. The theoretical generalizations in this article are limited particularly by the broad range of sentence lengths and types of crimes. Lengths of criminal careers and imprisonments are likely to affect the desistance processes notably. This raises the question of whether advancing a general theory of desistance is productive. While more recent desistance research has narrowed the contexts of desistance, knowledge about the general desistance process still needs to be refined.

Concluding remarks

This study shows the need for further research on prerelease expectations, especially concerning how motivation and self-regulation operate throughout the desistance process. Here, longitudinal approaches can highlight how and when different internal and external strategies for self-regulation are adopted in trying to desist from crime. Based on earlier research into the effect of desistance optimism on actual desistance, supporting and fostering desistance optimism is important during imprisonment. The findings of this study indicate that low-security prison conditions can affect prerelease expectations positively, even if many social and structural challenges in reintegration prevail. By recognizing and supporting the motivations and implementation intentions that prisoners have for their desistance optimism, prisons might be able to foster desistance.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Beckmann, J. (2001). Sports performance, self-regulation of. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (Vol. 11, pp. 14947–14952). Elsevier.

- Beckmann, J., & Heckhausen, H. (2008). Motivation as a function of expectancy and incentive. In J. Heckhausen & H. Heckhausen (Eds.), Motivation and action. Cambridge University Press.

- Bottoms, A., & Shapland, J. (2011). Steps towards desistance among male young adult recidivists. In S. Farrall, R. Sparks, S. Maruna, & M. Hough (Eds.), Escape routes: Contemporary perspectives on life after punishment (pp. 43–80). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203835883

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Burnett, R. (1993). Recidivism and imprisonment. Home Office Research Bulletin, 36, 19–22.

- Burnett, R., & Maruna, S. (2004). So ‘prison works’, does it? The criminal careers of 130 men released from prison under Home Secretary, Michael Howard. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(4), 390–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2311.2004.00337.x

- Clemmer, D. (1958). The prison community. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Cobbina, J., & Bender, K. (2012). Predicting the future: Incarcerated women's views of reentry success. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 51(5), 275–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2012.683323

- Criminal Sanctions Agency. (2020a). Goals, values, and principles. Criminal Sanctions Agency. Retrieved January 23, 2020, from https://www.rikosseuraamus.fi/en/index/criminalsanctionsagency/goalsvaluesandprinciples.html

- Criminal Sanctions Agency. (2020b). Statistical yearbook 2019. Criminal Sanctions Agency. https://www.rikosseuraamus.fi/material/attachments/rise/julkaisut-tilastollinenvuosikirja/pjeawUKaf/Statistical_Yearbook_2019_of_the_Criminal_Sanctions_Agency.pdf

- Dhami, M., Mandel, D., Loewenstein, G., & Ayton, P. (2006). Prisoners' positive illusions of their post-release success. Law and Human Behavior, 30(6), 631–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9040-1

- Doekhie, J., & Van Ginneken, E. (2020). House, bells and bliss? A longitudinal analysis of conventional aspirations and the process of desistance. European Journal of Criminology, 17(6), 744–763. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370818819702

- Doekhie, J., Dirkzwager, A., & Nieuwbeerta, P. (2017). Early attempts at desistance from crime: Prisoners’ prerelease expectations and their postrelease criminal behavior. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 56(7), 473–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2017.1359223

- Farrall, S., & Bowling, B. (1999). Structuration, human development and desistance from crime. British Journal of Criminology, 39(2), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/39.2.253

- Farrall, S., Hunter, B., Sharpe, G., & Calverley, A. (2014). Criminal careers in transition: The social context of desistance from crime. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199682157.001.0001

- Friestad, C., & Skog Hansen, I. (2010). Gender differences in inmates' anticipated desistance. European Journal of Criminology, 7(4), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370810363375

- Genicot, G., & Ray, D. (2017). Aspirations and inequality. Econometrica, 85(2), 489–519. https://doi.org/10.3982/ecta13865

- Giordano, P. C., Cernkovich Stephen, A., & Rudolph, J. L. (2002). Gender, crime, and desistance: Toward a theory of cognitive transformation. American Journal of Sociology, 107(4), 990–1064. https://doi.org/10.1086/343191

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54(7), 493–503. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493

- Graham, H., & McNeill, F. (2017). Desistance: Envisioning futures. In P. Carlen & L. A. França (Eds.), Alternative criminologies. Routledge.

- Halsey, M., Armstrong, R., & Wright, S. (2017). ‘F*ck it!’: Matza and the mood of fatalism in the desistance process. British Journal of Criminology, 57(5), 1041–1060. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azw041

- Heckhausen, J., & Heckhausen, H. (Eds.). (2008). Motivation and action. Cambridge University Press.

- Kazemian, L. (2007). Desistance from crime: Theoretical, empirical, methodological, and policy considerations. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 23(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986206298940

- Kivivuori, J., & Linderborg, H. (2010). Negative life events and self-control as correlates of self-assessed re-offending probability among Finnish prisoners. European Journal of Criminology, 7(2), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370809354139

- Kivivuori, J., Linderborg, H., Tyni, S., & Aaltonen, M. (2012). The robustness of self-control as a predictor of recidivism [Research Brief, 25/2012]. National Research Institute of Legal Policy.

- Kuhl, J. (2008). Individual differences in self-regulation. In J. Heckhausen & H. Heckhausen (Eds.), Motivation and Action. Cambridge University Press.

- Laws, D. R., & Ward, T. (2011). Desistance from sex offending: Alternatives to throwing away the keys. Guilford Press.

- LeBel, T. P., Burnett, R., Maruna, S., & Bushway, S. (2008). The ‘chicken and egg’ of subjective and social factors in desistance from crime. European Journal of Criminology, 5(2), 131–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370807087640

- Lewis, J., & Ritchie, J. (2003). Generalising from qualitative research. In J. Ritchie & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. Sage Publications.

- Liem, M., & Richardson, N. (2014). The role of transformation narratives in desistance among released lifers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 41(6), 692–712. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854813515445

- Maruna, S. (2001). Making good: how ex-convicts reform and rebuild their lives. American Psychological Association.

- McNeill, F., & Weaver, B. (2010). Changing lives? Desistance research and offender management [SCCJR Project Report No. 77]. SCCJR.

- Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100(4), 674–701. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674

- Nugent, B., & Schinkel, M. (2016). The pains of desistance. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 16(5), 568–584.

- Paternoster, R., & Bushway, S. (2009). Desistance and the “feared self”: Toward an identity theory of criminal desistance. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 99(4), 1103–1156.

- Presser, L. (2009). The narratives of offenders. Theoretical Criminology, 13(2), 177–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480609102878

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

- Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Harvard University Press.

- Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (2003). Life-course desisters? Trajectories of crime among delinquent boys followed to age 70. Criminology, 41(3), 555–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2003.tb00997.x

- Sandberg, S. (2010). What can “lies” tell us about life? Notes towards a framework of narrative criminology. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 21(4), 447–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2010.516564

- Schaefer, L. (2016). On the reinforcing nature of crime and punishment: An exploration of inmates’ self-reported likelihood of reoffending. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 55(3), 168–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2016.1148091

- Shapland, J., & Bottoms, A. (2011). Reflections on social values, offending and desistance among young adult recidivists. Punishment & Society, 13(3), 256–282.

- Souza, K. A., Lösel, F., Markson, L., & Lanskey, C. (2015). Pre‐release expectations and post‐release experiences of prisoners and their (ex‐)partners. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 20(2), 306–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12033

- Uggen, C., & Wakefield, S. (2008). What have we learned from longitudinal studies of work and crime? In A. M. Liberman (Ed.), The long view of crime: A synthesis of longitudinal research (pp. 191–219). Springer. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-71165-2_6

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12048

- Visher, C. A., & Connell, D. J. (2012). Incarceration and inmates’ self perceptions about returning home. Journal of Criminal Justice, 40(5), 386–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2012.06.007

- Vogel, D. L., Wester, S. R., & Larson, L. M. (2007). Avoidance of counseling: Psychological factors that inhibit seeking help. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85(4), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00609.x