Abstract

Recent studies have emphasized that silence is a fundamental element in meditative practices for stress relief, well-being, and stimulating faith in the future. This study describes the educational experience of implementing the Practice of Silence Device in a prison setting during the second wave of Covid-19 pandemic (May–July, 2021). Interviews with 23 adult male imprisoned individuals (average age = 48.79; 65% Italians) were analyzed through a qualitative-phenomenological method. The results revealed this technique’s positive impact on rehabilitating imprisoned individuals across 3 dimensions: coping, emotion management, and ability to plan the future. Future studies should investigate specific silence-based techniques to support imprisoned individuals’ rehabilitation.

Introduction

An in-depth investigation of the scientific literature related to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental and physical well-being of imprisoned individuals revealed an increase of self-injurious and suicidal behaviors, and hetero-directed aggression episodes (Hewson et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, pandemic-related experiences, especially in the most fragile and marginalized populations, have exacerbated the sense of an uncertain future (Freeman & Seymour, Citation2010) and the perception of social isolation (Johnson et al., Citation2021).

At the end of March 2022, Italian prisons were in a state of chronic overcrowding, with 54,609 incarcerated individuals in nearly 200 institutions across the country, when compared to a regulatory capacity of 50,853 (Dipartimento dell’Amministrazione penitenziaria [Department of Prison Administration], Citation2022; Associazione Antigone, Citation2022). Article 27 of the Italian Constitution stipulates that sentences should aim at reeducating the convicted individual; however, intramural treatment activities that can contribute to this goal (e.g., work, school, cultural activities, etc.) are scarce and diversely implemented between institutions. This is caused by the limited numbers of educators, approximately 700 (an average of one educator for every 74 imprisoned individuals), in Italy. Conversely, the presence of prison police is much higher at approximately 31,000 officers. This disproportion depicts the penitentiary as a place of deprivation of freedom that leads to non-progressive pathways for the social reintegration of imprisoned individuals (Maculan, Citation2019). However, researchers who investigated the functioning of alternative rehabilitative activities in penitentiaries with incarceration rates higher than Italy’s (Derlic, Citation2020), reported that employing resources in complementary activities increases imprisoned individuals’ well-being and decreases total management costs (Bilderbeck et al., Citation2013; Crichlow & Joseph, Citation2015; Ruedy & Schweitzer, Citation2010; Shapiro et al., Citation2012).

A recent systematic review (Derlic, Citation2020) highlighted the use of alternative rehabilitation methods, including yoga, meditation, and mindfulness, integrated into structured programs and carried out regularly in complex and difficult contexts, such as prisons, to protect and promote psychophysical well-being and gain a better perception of life in prison; moreover, these methods strengthen life skills, which influence the complex process of societal reintegration (Lorenzon, Citation2020) in the long-term. Yoga helps the mind to “listen” to the “breath” by silencing thoughts and allowing the body to release tensions. It fosters greater self-awareness and self-healing and reduces anxiety and depressive symptoms. Additionally, it results in a perception of general well-being and improved physical pain control in the imprisoned individuals (Bilderbeck et al., Citation2013; Crichlow & Joseph, Citation2015). Meditative practices appear to elicit the incarcerated individuals’ awareness of self and body, relaxation, attention and focus skills, feelings of self-actualization, self-efficacy, empathy, and forgiveness (Derlic, Citation2020; Moore et al., Citation2018). In the prison context, mindfulness techniques can increase imprisoned individuals’ awareness of their cognitive decision-making processes by anchoring them in the present through reinforcement of their internal experience (that occurs during the practice of silence) (Crichlow & Joseph, Citation2015) and improving their prosociality with a concomitant decrease in stress and aggressive behaviors (Ruedy & Schweitzer, Citation2010; Shapiro et al., Citation2012). Practicing meditation during incarceration may both improve individual emotional intelligence (Combs et al., Citation2019; Moore et al., Citation2018; Perelman et al., Citation2012), control aggression and decrease sleep disturbances and the sense of guilt (Sumter et al., Citation2009). Psychotherapeutic approaches for imprisoned individuals, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and integrated principles of Buddhist meditation, lead to a significant decrease in anger and reactivity (Moore et al., Citation2018; Vannoy & Hoyt, Citation2004). Similarly, holistic therapies may support imprisoned individuals in recognizing and accepting their self-image, provide a meaningful experience and offer a flexible tool to adapt to prison settings (Griera & Clot-Garrell, 2005; Derlic, Citation2020).

Among the different techniques, silence (an element of meditation, guided meditation, and mindfulness) can specifically impact stress and anxiety management. Silence activates adaptive coping strategies in fragile and exposed individuals, such as incarcerated individuals (irrespective of whether they have overt psychiatric illnesses) (Combs et al., Citation2019; Hölzel et al., Citation2011; Leidenfrost et al., Citation2016). Silence-based meditative practices can increase mental clarity, focused attention, de-automatize the cognitive responses, and decrease rumination (Hanley & Garland, Citation2019; Shonin & Van Gordon, Citation2016).

In Italy, only Garofalo et al. (Citation2020) investigated mindfulness among imprisoned individuals, where they highlighted a negative association between this construct and aggressiveness. However, up to date qualitative research on the effects of silence-based meditation among incarcerated individuals is still lacking. Thus, the present study wants to deepen a still unexplored field, both theoretically and empirically.

Practice of Silence Device (PSD)

Among the different guided meditation and mindfulness techniques, the Practice of Silence Device (PSD) was applied within the Envisioning the Future (EF) training program in the prison context (Di Giuseppe, Perasso, Mazzeo, et al., Citation2022; Di Giuseppe, Perasso, Maculan, et al., Citation2022; Paoletti, Di Giuseppe, et al., Citation2023). The PSD is a short 3-min meditation technique inspired by the O.M.M. (One Minute Meditation) method (Paoletti, Citation2018), which is based on the theoretical framework of the Sphere Model of Consciousness (Paoletti & Ben-Soussan, Citation2019, Citation2020; Pintimalli et al., Citation2020). The nodal and integral parts of EF training program mainly focus on fostering resilience. Furthermore, PSD can be used in a variety of challenging contexts (educational, rehabilitation, emergency, etc.). The EF training program aims to support well-being and the prefiguration of the future (Di Giuseppe et al., Citation2023; Paoletti, Perasso, et al., Citation2023), emotional self-regulation, and the ability to proactively resignify individual experiences (Di Giuseppe, et al., Citationin press; Maculan et al., Citation2022; Paoletti, Di Giuseppe, Lillo, Serantoni, et al., Citation2022).

EF training program integrates the 10 keys for resilience (Di Giuseppe, Citation2022; Paoletti, Di Giuseppe, Lillo, Anella, et al., Citation2022); specifically, key 9 proposes the PSD (). According to this theoretical and practical framework, PSD splits the individual’s attention between breath and body and requires them to focus on images of a better version of themselves. Several studies have reported that individual cognitive processes are stimulated by the experience of silence, which can strengthen an individual’s internal and relational resources. Silence leads to a present characterized by the absence of stimuli that usually trigger negative emotions (Crichlow & Joseph, Citation2015; Pintimalli et al., Citation2020; Ruedy & Schweitzer, Citation2010; Shapiro et al., Citation2012). The PSD has three main goals: (i) increase the ability to self-observe automatic and maladaptive dynamics of thinking and behavior; (ii) develop emotional management skills by encouraging neutral and positive purpose-directed emotions; and (iii) improve the proactive intentional resignification of experiences, resulting in an awakening of future planning skills. The PSD was taught to incarcerated individuals according to its five phases: (1) a meditation preparatory phase of simple and brief instructions that prepares participants for the subsequent phases of actual meditation; (2) division of participants’ attention both on breath and body relaxation, through an enhanced attention to the here and now; (3) connection to silence as a psychophysical state related to both emotional and mental predisposition and to self-acceptance, neutrality, and nonjudgment. During this stage, participants are invited to welcome and neutralize their emotions, whether positive or negative, and to assume a nonjudgmental position; (4) construction of a better mental self-image involving awareness of the body, emotions, and thoughts. During this stage, participants are invited to be conscious of their posture, physical energy, and emotional and mental states. Through this process, participants aim for a better version of themselves, fostering the expression of their future desires; and (5) identification of the small daily acts that can enable participants to achieve the desired change.

Table 1. 10 Keys to resilience (mod. Paoletti, Di Giuseppe, Lillo, Ben-Soussan, et al., Citation2022).

Objectives and hypotheses

This qualitative study aims at analyzing the influence of PSD on the coping skills of imprisoned individuals who participated in EF. We hypothesize that the program could ameliorate imprisoned individuals’ coping skills, emotional regulation, and the ability to plan their future.

Materials and methods

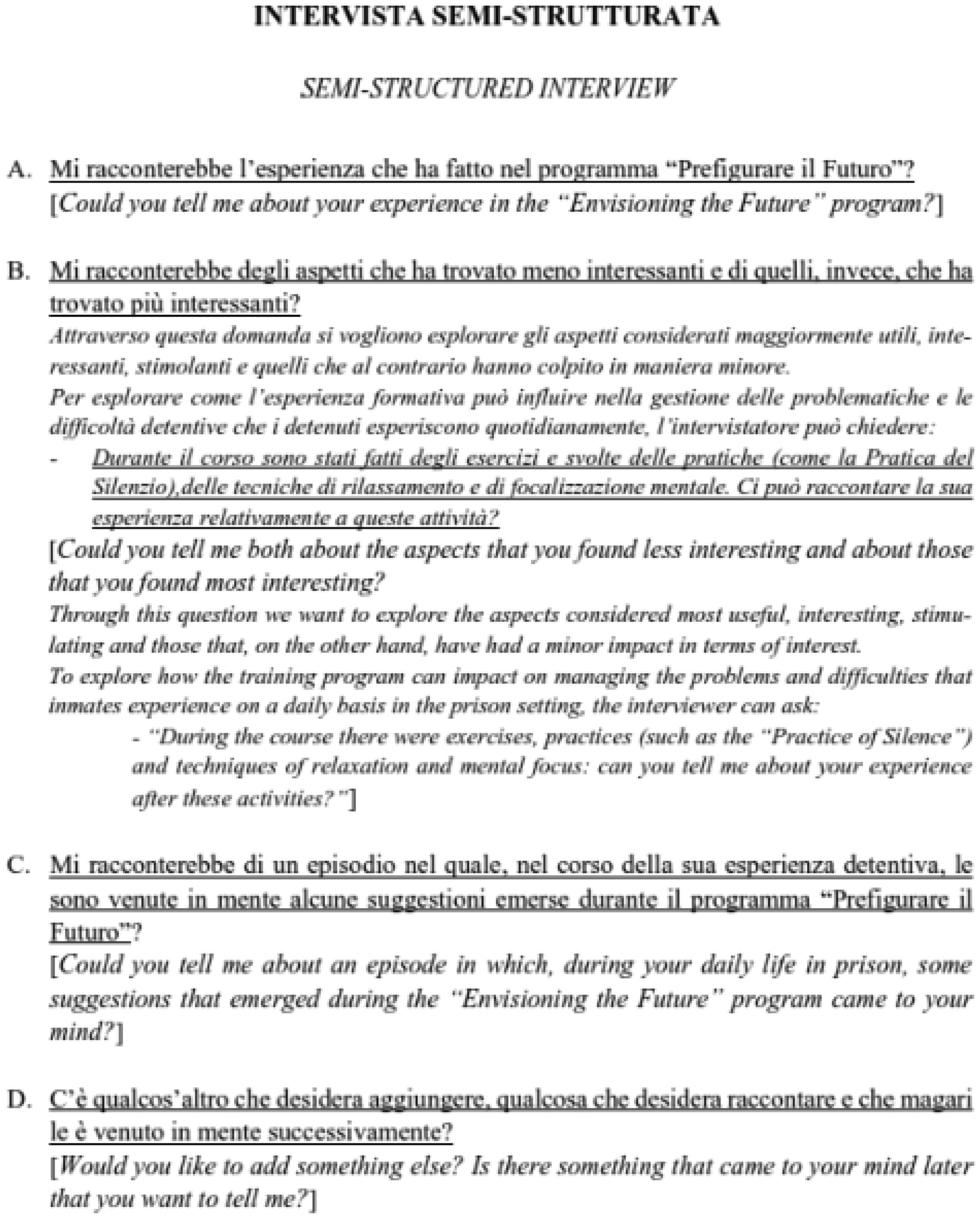

The EF training program proposed at the Padua Prison, originally conceived by the interdisciplinary team of the Patrizio Paoletti Foundation in 2017, was remodeled based on the specific needs arising from both the COVID-19 pandemic situation and prison context. It was remotely implemented through collaboration among the Patrizio Paoletti Foundation, the University of Padua, and Padua Prison. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee (EC) of the University of Padua (dossier no. 2020-III/13.41.4). The program included 9 sessions of 60 min, conducted weekly over a three-month period, led by trainers with expertise in the Pedagogy for the Third Millennium method (PTM) (Paoletti, Citation2008). The sessions explored the 10 keys to resilience (), based on interdisciplinary studies (Paoletti, Di Giuseppe, Lillo, Anella, et al., Citation2022), and special attention was given to key 9 (i.e., “Practice a few minutes of silence”). Trainers prescribed participants to also practice the PSD in the intervals between lessons. To evaluate the experience of participation in the training, an ad hoc semi-structured interview was created for investigating with three open questions: (a) main aspects of participation in the program; (b) usefulness of the proposed techniques, in particular the PSD, in the management of daily life in prison; and (c) anecdotes and insights (See Appendix A). The interviews were conducted in person, 8-weeks after the end of the training, due to institutional and organizational issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Interviews were administered by two qualified researchers from the University of Padua. The mean time-length of the interviews was 1.5 hours.

Participants

The project involved N = 36 male imprisoned individuals of Padua prison who participated in the training. Among them, a group of imprisoned individuals (N = 23) (average age = 48.79 years; 65% were of Italian nationality) voluntarily participated in the research (i.e., convenience sampling), responding to semi-structured interviews after the end of the training. All participants understand and speak Italian. The participants had been sentenced to >5 years of imprisonment as “medium-security level” incarcerated individuals, according to Italian law (D.A.P. Circular No. 3359/5890, dated April 21, 1993). The interviews were conducted by trained operators at the Padua prison, with adequate privacy. Each participant completed an informed consent form for participation and audio recording of the interviews.

Data analysis

Data analysis aimed at the exploration of the explicit and implicit meanings of the testimonies (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Sbraccia & Vianello, Citation2016). The data was thematically analyzed in a bottom-up, inductive, and recursive sense in the framework of the Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Terry et al., Citation2017). Subsequently, a Content Analysis identified the emerging themes and categories from the transcribed texts, as shown in .

Figure 1. Coding tree of the categories identified through content analysis, tagging and thematic analysis of the full text interviews with 23 imprisoned individuals participating in the research [N = number of interviews/recurrence of the topic].

![Figure 1. Coding tree of the categories identified through content analysis, tagging and thematic analysis of the full text interviews with 23 imprisoned individuals participating in the research [N = number of interviews/recurrence of the topic].](/cms/asset/c17b4324-8455-40ee-b270-b84c3b7d8d73/wjor_a_2246449_f0001_b.jpg)

To control the biases related to qualitative text analysis, two independent evaluators attributed scores on interval (relevance from “1 to 10”) and ordinal (relevance from “insufficient” to “excellent”) scales. This step aided in proceeding with the calculation of two specific indices of interrater agreement (Banerjee et al., Citation1999), namely, Pearson’s r and Cohen’s k for interrater consistency analysis.

Results

The emerging categories, in line with the aims of this study, were identified from the qualitative analysis of the interview transcripts: (i) Silence and stress coping skills (); (ii) Silence and emotion regulation (); (iii) Silence and future planning ().

Table 2. Self-report excerpts selected for the ‘silence and coping’ category identified by text analysis.

Table 3. Self-report excerpts selected for the ‘silence and emotion regulation’ category identified by text analysis.

Table 4. Self-report excerpts selected for the ‘silence and future planning’ category identified by the text analysis.

The narratives collected among the imprisoned individuals, while different and containing specific details about their personal experiences during the EF training program, had common themes related to the training experience. The chosen excerpts are representative of most of the interview responses. The inter-rater agreement scores were positively correlated (r = .83; p < .001) and demonstrated high agreement (Cohen’s k = .89).

Discussion

Silence and coping

Coping is defined as the individual’s ability to deal with stressful events (Sica et al., Citation2008) by using different strategies aimed at reducing the potentially harmful consequences of the exposure to stressors and to contain the negative emotions triggered (Cramer, Citation1998). Coping, as a relatively stable and adaptive personality trait, works primarily on two aspects: both on containing the damage that might result from a stressful event (problem-focused coping) and negative emotion reactions (emotion-focused coping) (Baker & Berenbaum, Citation2007). According to the literature, coping is related to resilience (Leipold & Greve, Citation2009) in a biunivocal relationship (Kang & Suh, Citation2015; Liang et al., Citation2020). Coping strategies such as problem-focused strategies (De la Fuente et al., Citation2017) and positive attitude (Tugade & Fredrickson, Citation2004) can increase individual resilience in the face of adverse events and contexts.

In the specific context of prison, scientific literature has shown that coping is one of the most important variables in predicting imprisoned individuals’ well-being (Gullone et al., Citation2000), through different coping strategies such as: optimism (Segovia et al., Citation2012), sharing negative emotions (Van Harreveld et al., Citation2007), sought-after friends and family social support (Agbakwuru & Awujo, Citation2016), reevaluation of individual’s past (Skowroński & Talik, Citation2018), spirituality and the search for meaning (Agbakwuru & Awujo, Citation2016; Vanhooren et al., Citation2018; Skowroński & Talik, Citation2018). The last two, in particular, predict post-traumatic growth, which is fundamental to the individual’s present and future (Vanhooren et al., Citation2018). In addition, prison is a context where coping can determine the response to environmental stimuli by modulating the individual’s cognitive, physical and behavioral responses (Leban et al., Citation2015).

As emerges from the testimonies of imprisoned individuals and on the basis of scientific evidence, the EF training, implemented in a multidimensional way through the PSD, underlines how silence can be an adaptive coping strategy (Bonanno & Burton, Citation2013). In the EF training, PSD is taught through observation, which elicits an imitation response at the neurophysiological level (Van Gog et al., Citation2009). Extracts from the incarcerated individuals’ interviews show how the PSD has become part of their daily routine, representing a peculiar and multidimensional coping response, at the physical, emotional, and behavioral levels simultaneously. To this target population, the practice of silence seems to represent a useful instrument in promoting improvement in terms of an increased positive attitude (Paoletti, Di Giuseppe, Lillo, Serantoni, et al., Citation2022) and improved communication skills and social support seeking (Seema & Ajithkumar, Citation2019). In some cases, PSD also represented a positive coping strategy, useful in discouraging incarcerated individuals from negative and harmful ways of dealing with stress, like avoidance (Luke et al., Citation2021) and substance use (van de Baan et al., Citation2022).

Silence and emotional regulation

Emotional regulation involves monitoring and modulating the frequency and intensity of both experienced emotions and related psychophysical states (Gross, Citation2002). Emotions can be regulated through the following strategies (Goldin et al., Citation2008; McRae et al., Citation2010): (i) reappraisal (reinterpreting the cause of the emotion); (ii) distraction (directing attentional focus away from the emotional stimulus); and (iii) suppression (inhibiting spontaneous emotional responses, such as facial expressions).

In difficult contexts, including prisons, emotional modulation implies effective control over anger, irritation, and discouragement, and actively protecting individual’s mental and physical well-being (Caprara et al., Citation2008). Moreover, these emotions are common among incarcerated individuals due to multiple factors, such as clashes with other incarcerated individuals resulting from promiscuity and forced cohabitation, conflicting relationships with prison staff (often due to the existing asymmetry of power), the sense of uncertainty, and the indeterminacy of their sentences (Crewe, Citation2011).

Interview excerpts revealed that the PSD may be an emotional regulation instrument for incarcerated individuals. They reported on PSD-related experiences and reflections, such as perceiving an increased state of calm and tranquility. These results may be useful in blocking the negative emotional responses of anger, increased arousal, and anxiety, while increasing decision-making and reasoning on the moral and ethical nature of their actions (Shapiro et al., Citation2012; Ruedy & Schweitzer, Citation2010). Meditation can be considered an emotional regulation strategy, as it can promote both attentional refocusing through the interruption of rumination and dysfunctional thoughts, and a reinterpretation of exogenous and endogenous stimuli (Walsh & Shapiro, Citation2006). In addition, it focuses attention on a conscious process of alteration of the states of relaxation and alertness (Lutz et al., Citation2007). Several studies have reported that the practice of silent meditation for a few minutes for at least 3–8 weeks (Menezes et al., Citation2012) can significantly improve the regulation of negative emotions and internal states (Schroevers & Brandsma, Citation2010), such as anxiety (Goldin & Gross, Citation2010), sadness (Farb et al., Citation2010), and stress (Fang et al., Citation2010), by increasing these abilities and inducing a state of relaxation and attentional control (Menezes et al., Citation2012; Venditti et al., Citation2020).

Silence and future planning

The results demonstrate that PSD can awaken the capacity to set goals and plan the future among imprisoned individuals. The testimonies of the imprisoned individuals suggest that the PSD allowed them to accept their past to project themselves into the future, discover new personal skills, and choose a positive perspective. Nevertheless, the scientific literature reports that the imprisoned individuals’ concept of the future is influenced by several factors, such as (i) length of sentence, (ii) socio-anagraphical variables (e.g., age, marital status), (iii) perceived social support and (iv) being engaged in organized activities that facilitate social reintegration (Vuk & Applegate, Citation2021). Meditative practices in prison may have a virtuous influence because they offer immense social and cognitive stimuli that promote future planning in an environment that is normally does not stimulate this specific aspect (Lorenzon, Citation2020). Similar to other activities that imprisoned individuals can perform when there is an opportunity (work, training, etc.), alternative rehabilitative practices influence the possibility and ability to think ahead (Carvalho et al., Citation2018). Time spent in prison need not be a time of suspension and waiting; it can be a time for the promotion of new methods of learning, including techniques for self-care, such as the PSD, as experienced by the participants.

Several studies on increased optimism and positive attitudes in incarcerated individuals have reported that these variables are correlated with a change in the concept of the future in terms of employment, social relationships, attainment of educational qualifications, involvement in childcare, financial and domestic stabilization (Giordano et al., Citation2007), and decreased recidivism (Maruna, Citation2001).

Limitations

Qualitative research is often dependent on the researchers’ interpretation (Lieblich et al., Citation1998). Therefore, to counteract potential biases, rating grids were established for two independent evaluators. Subsequently, the quantitative and qualitative responses correspondence was analyzed to measure the categorization effectiveness of the interview excerpts.

Social desirability (Edwards, Citation1957), a potential bias by the respondent to a questionnaire or interview to ensure that he or she is perceived as trustworthy, is another limitation. This construct is widespread, especially among imprisoned individuals (Mielitz & MacDonald, Citation2020; Stuckless et al., Citation1995). This aspect intercepts a deep need to be seen as individuals beyond the stigma of incarceration (LeBel, Citation2012; Chui & Cheng, Citation2013). Imprisoned individuals respond by endeavoring to interpret and meet the expectations of others, including the prison staff and the society.

A final consideration needs to be made as regards the difficulties in applying the DPS. The imprisoned individuals’ excerpts highlight that practicing such techniques within prisons require the capacity to isolate the self, in a place where an individual’s privacy is often threatened by forced coexistence with other people and the overcrowdedness of penitentiaries (Goffman, Citation1968). Recent literature has reported that the continuous noise generated by imprisoned individuals’ conversations, the shouts of the staff summoning someone, and the clanging of the keys to the gates are peculiar characteristics of detention, which negatively impact the conditions of prison life (Elger, Citation2009; Rice, Citation2016) and, consequently, on the possibility to practice the DPS.

Conclusion

The outcomes of the present study emphasize that the practice of silence can be an invaluable instrument in strengthening the coping skills required to deal with the adversities of daily life in prison. Concurrently, PSD may increase emotional regulation skills and reinforce internal responsiveness that enable better coping with difficulties and promote a generalized state of well-being. PSD is an easily transferable and applicable device, even in settings with limited personal space. The daily practice of meditation and silence enabled the imprisoned individuals to experience a state of calm and balance that allowed them to proactively reconsider the narrative of themselves and their future. Additionally, the imprisoned individuals’ responses suggest their willingness to practice silence-based meditation in the long term, even after they leave prison, and indicates their desire to project themselves confidently into the future. The challenges they may face during the complex process of reentering society are perceived as less threatening due to their enhanced self-determination and personal empowerment. Therefore, the present study is a pioneering investigation into the effects of PSD.

Acknowledgements

The Regional Guarantor of Personal Rights of the Veneto Region, Mirella Gallinaro; Fondazione Mediolanum Onlus (co-financer of the project): Sara Doris and Oscar Di Montigny; the Director of the C.R. Padua: Claudio Mazzeo; the pedagogical area official—C.R. Padua, Anna Maria Morandin; the computer referent of C. R. Padua, Edoardo De Santis; the pedagogical area responsible—C. R. Padova, Lorena Orazi; the deputy Commander of the Penitentiary Police—C.R. Padua, Maria Grazia Grassi; the agents of the Penitentiary Police—C. R. Padua: Amedeo Salentini, Alessandro Pinto; the project coordinator for the Paoletti Foundation, Luca Cerrao. We would also like to thank the research participants, volunteers, penitentiary police officers, prison workers, social workers and students from the University of Padua.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agbakwuru, C., & Awujo, G. C. (2016). Strategies for coping with the challenges of incarceration among Nigerian prison inmates. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(23), 153–157.

- Associazione Antigone. (2022). Il carcere visto da dentro. XVIII rapporto di Antigone sulle condizioni di detenzione. https://www.rapportoantigone.it/diciottesimo-rapporto-sulle-condizioni-di-detenzione/

- Banerjee, M., Capozzoli, M., McSweeney, L., & Sinha, D. (1999). Beyond kappa: A review of interrater agreement measures. Canadian Journal of Statistics, 27(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/3315487

- Baker, J. P., & Berenbaum, H. (2007). Emotional approach and problem-focused coping: A comparison of potentially adaptive strategies. Cognition & Emotion, 21(1), 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600562276

- Bilderbeck, A. C., Farias, M., Brazil, I. A., Jakobowitz, S., & Wikholm, C. (2013). Participation in a 10-week course of yoga improves behavioural control and decreases psychological distress in a prison population. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(10), 1438–1445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.06.014

- Bonanno, G. A., & Burton, C. L. (2013). Regulatory flexibility: An individual differences perspective on coping and emotion regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613504116

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Caprara, G. V., Di Giunta, L., Eisenberg, N., Gerbino, M., Pastorelli, C., & Tramontano, C. (2008). Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychological Assessment, 20(3), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.20.3.227

- Carvalho, R. G., Capelo, R., & Nunez, D. (2018). Perspectives concerning the future when time is suspended: Analysing inmates’ discourse. Time & Society, 27(3), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X15604533

- Chui, W. H., & Cheng, K. K. Y. (2013). The mark of an ex-prisoner: Perceived discrimination and self-stigma of young men after prison in Hong Kong. Deviant Behavior, 34(8), 671–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2013.766532

- Combs, E., Guston, K., Kopak, A., Raggio, A., & Hoffmann, N. G. (2019). Posttraumatic stress, panic disorder, violence, and recidivism among local jail detainees. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 15(4), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPH-06-2018-0036

- Cramer, P. (1998). Coping and defense mechanisms: What’s the difference? Journal of Personality, 66(6), 919–946. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00037

- Crewe, B. (2011). Depth, weight, tightness: Revisiting the pains of imprisonment. Punishment & Society, 13(5), 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474511422172

- Crichlow, W., & Joseph, J. (Eds.). (2015). Alternative offender rehabilitation and social justice: Arts and physical engagement in criminal justice and community settings. Springer.

- De la Fuente, J., Fernández-Cabezas, M., Cambil, M., Vera, M. M., González-Torres, M. C., & Artuch-Garde, R. (2017). Linear relationship between resilience, learning approaches, and coping strategies to predict achievement in undergraduate students. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1039. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01039

- Derlic, D. (2020). A systematic review of literature: Alternative offender rehabilitation-Prison yoga, mindfulness, and meditation. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 26(4), 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345820953837

- Di Giuseppe, T. (2022). Envisioning the future and the 10 keys for resilience. In Resilience For The Future. An international roundtable to promote resilience in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. https://elearning.fondazionepatriziopaoletti.org/resilience-for-the-future-in-time-of-pandemic-da-covid-19-an-international-roundtable.

- Di Giuseppe, T., Serantoni, G., Paoletti, P., & Perasso, G. (2023). Un sondaggio a quattro anni da Prefigurare il Futuro, un intervento neuropsicopedagogico postsisma [A survey four years after Envisioning the Future, a post-earthquake neuropsychopedagogic intervention]. Orientamenti Pedagogici, 70(2), 79–85.

- Di Giuseppe, T., Perasso, G., Mazzeo, C., Maculan, A., Vianello, F., & Paoletti, P. (2022). Envisioning the future: A neuropsycho-pedagogical intervention on resilience predictors among inmates during the pandemic. Ricerche Di Psicologia – Open Access, (3). https://doi.org/10.3280/rip2022oa14724

- Di Giuseppe, T., Perasso, G., Paoletti, P., Mazzeo, C., Maculan, A., & Vianello, F. (in press) Prefigurare il Futuro: un intervento neuro-psicopedagogico sui predittori della resilienza nei detenuti in tempi pandemici. Ricerche di psicologia, Open Access.

- Di Giuseppe, T., Perasso, G., Maculan, A., Vianello, F., & Paoletti, P. (2022). Envisioning the future: Ten keys to enhance resilience predictors among inmates. In The Paris Conference on Education 2022: Official Conference Proceeding, Vol. 10, pp. 2758–0962. https://doi.org/10.22492/issn.2758-0962.2022.21

- Dipartimento dell’Amministrazione penitenziaria. (2022). – Ufficio del Capo del Dipartimento – Sezione Statistica. https://www.giustizia.it/giustizia/it/mg_1_14.page.

- Edwards, A. L. (1957). The social desirability variable in personality assessment and research. Dryden.

- Elger, B. S. (2009). Prison life: Television, sports, work, stress and insomnia in a remand prison. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 32(2), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2009.01.001

- Fang, C. Y., Reibel, D. K., Longacre, M. L., Rosenzweig, S., Campbell, D. E., & Douglas, S. D. (2010). Enhanced psychosocial well-being following participation in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program is associated with increased natural killer cell activity. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(5), 531–538. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2009.0018

- Farb, N. A., Anderson, A. K., Mayberg, H., Bean, J., McKeon, D., & Segal, Z. V. (2010). Minding one’s emotions: Mindfulness training alters the neural expression of sadness. Emotion, 10(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017151

- Freeman, S., & Seymour, M. (2010). ‘Just waiting’: The nature and effect of uncertainty on young people in remand custody in Ireland. Youth Justice, 10(2), 126–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225410369298

- Garofalo, C., Gillespie, S. M., & Velotti, P. (2020). Emotion regulation mediates relationships between mindfulness facets and aggression dimensions. Aggressive Behavior, 46(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21868

- Giordano, P. C., Schroeder, R. D., & Cernkovich, S. A. (2007). Emotions and crime over the life course: A neo-Meadian perspective on criminal continuity and change. American Journal of Sociology, 112(6), 1603–1661. https://doi.org/10.1086/512710

- Goffman, E. (1968). Asylums: Le istituzioni totali: i meccanismi dell’esclusione e della violenza. Einaudi.

- Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2010). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder. Emotion, 10(1), 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018441

- Goldin, P. R., McRae, K., Ramel, W., & Gross, J. J. (2008). The neural bases of emotion regulation: Reappraisal and suppression of negative emotion. Biological Psychiatry, 63(6), 577–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.031

- Griera, M., & Clot-Garrell, A. (2015). Doing yoga behind bars: A sociological study of the growth of holistic spirituality in penitentiary institutions. In Religious diversity in European prisons (pp. 141–157). Springer.

- Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(3), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0048577201393198

- Gullone, E., Jones, T., & Cummins, R. (2000). Coping styles and prison experience as predictors of psychological well‐being in male prisoners. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 7(2), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218710009524983

- Hanley, A. W., & Garland, E. L. (2019). Spatial frame of reference as a phenomenological feature of self-transcendence: Measurement and manipulation through mindfulness meditation. Psychology of Consciousness, 6(4), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000204

- Hewson, T., Shepherd, A., Hard, J., & Shaw, J. (2020). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of prisoners. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(7), 568–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30241-8

- Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671

- Johnson, L., Gutridge, K., Parkes, J., Roy, A., & Plugge, E. (2021). Scoping review of mental health in prisons through the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ open, 11(5), e046547. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046547

- Kang, J., & Suh, E. E. (2015). The influence of stress, spousal support, and resilience on the ways of coping among women with breast cancer. Asian Oncology Nursing, 15(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2015.15.1.1

- Leban, L., Cardwell, S. M., Copes, H., & Brezina, T. (2015). Adapting to prison life: A qualitative examination of the coping process among incarcerated offenders. Justice Quarterly, 33(6), 943–969. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2015.1012096

- LeBel, T. P. (2012). Invisible stripes? Formerly incarcerated persons’ perceptions of stigma. Deviant Behavior, 33(2), 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2010.538365

- Leidenfrost, C. M., Calabrese, W., Schoelerman, R. M., Coggins, E., Ranney, M., Sinclair, S. J., & Antonius, D. (2016). Changes in psychological health and subjective well-being among incarcerated individuals with serious mental illness. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 22(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345815618200

- Leipold, B., & Greve, W. (2009). Resilience: A conceptual bridge between coping and development. European Psychologist, 14(1), 40–50. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1027/1016-9040.14.1.40

- Liang, S. Y., Liu, H. C., Lu, Y. Y., Wu, S. F., Chien, C. H., & Tsay, S. L. (2020). The influence of resilience on the coping strategies in patients with primary brain tumors. Asian Nursing Research, 14(1), 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2020.01.005

- Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Sage.

- Lorenzon, J. (2020). Dalla matematica della recidiva alla complessità del fine pena. Autonomie locali e servizi sociali, 43(3), 631–644. https://doi.org/10.1447/99931

- Luke, R. J., Daffern, M., Skues, J. L., Trounson, J. S., Pfeifer, J. E., & Ogloff, J. R. (2021). The effect of time spent in prison and coping styles on psychological distress in inmates. The Prison Journal, 101(1), 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885520978475

- Lutz, A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2007). Meditation and the neuroscience of consciousness: An introduction. In P. Zelazo, M. Moscovitch & E. Thompson (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of consciousness (pp. 499–554). Cambridge University Press.

- Maculan, A., Di Giuseppe, T., Vianello, F., & Vivaldi, S. (2022). Narrazioni e risorse. Gli operatori del sistema penale minorile al tempo del Covid. Autonomie locali e servizi sociali, 2, 2022.

- Maculan, A. (2019). Non Solo Detenuti: Chi Lavora nelle Nostre Carceri?. In Associazione Antigone, Il Carcere Secondo la Costituzione. XV Rapporto di Antigone Sulle Condizioni di Detenzione, Associazione Antigone.

- Maruna, S. (2001). Making good: How ex-convicts reform and rebuild their lives. American Psychological Association.

- McRae, K., Hughes, B., Chopra, S., Gabrieli, J. D., Gross, J. J., & Ochsner, K. N. (2010). The neural bases of distraction and reappraisal. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(2), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2009.21243

- Menezes, C. B., Pereira, M. G., & Bizarro, L. (2012). Sitting and silent meditation as a strategy to study emotion regulation. Psychology & Neuroscience, 5(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.3922/j.psns.2012.1.05

- Mielitz, K., & MacDonald, M. (2020). Social desirability in multivariate context for inmate survey research. Corrections, 7(4), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/23774657.2020.1789520

- Moore, K. E., Folk, J. B., Boren, E. A., Tangney, J. P., Fischer, S., & Schrader, S. W. (2018). Pilot study of a brief dialectical behavior therapy skills group for jail inmates. Psychological Services, 15(1), 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000105

- Paoletti, P. (2008). Crescere nell’eccellenza. Armando editore.

- Paoletti, P. (2018). OMM, the One Minute Meditation, Tenero. Medidea.

- Paoletti, P., & Selvaggio, A. (2011a). Osservazione. Quaderni di Pedagogia per il Terzo Millennio. Edizioni 3P.

- Paoletti, P., & Selvaggio, A. (2011b). Mediazione. Quaderni di Pedagogia per il Terzo Millennio. Edizioni 3P.

- Paoletti, P., & Selvaggio, A. (2012). Traslazione. Quaderni di Pedagogia per il Terzo Millennio. Edizioni 3P.

- Paoletti, P., & Selvaggio, A. (2013). Normalizzazione. Quaderni di Pedagogia per il Terzo Millennio. Edizioni 3P.

- Paoletti, P., & Ben-Soussan, T. D. (2019). The Sphere model of consciousness: From geometrical to neuro-psycho-educational perspectives. Logica Universalis, 13(3), 395–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11787-019-00226-0

- Paoletti, P., & Ben-Soussan, T. D. (2020). Reflections on inner and outer silence and consciousness without contents according to the sphere model of consciousness. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1807. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01807

- Paoletti, P., Di Giuseppe, T., Lillo, C., Anella, S., & Santinelli, A. (2022). Le Dieci Chiavi della Resilienza. https://fondazionepatriziopaoletti.org/10-chiavi-resilienza/

- Paoletti, P., Di Giuseppe, T., Lillo, C., Serantoni, G., Perasso, G., Maculan, A., & Vianello, F. (2022). La resilienza nel circuito penale minorile in tempi di pandemia: un’esperienza di studio e formazione basata sul Modello Sferico della Coscienza su un gruppo di educatori. In Narrare i Gruppi, latest – 10 luglio 2022, 1–21. www.narrareigruppi.it.

- Paoletti, P., Di Giuseppe, T., Lillo, C., Ben-Soussan, T. D., Bozkurt, A., Tabibnia, G., Kelmendi, K., Warthe, G. W., Leshem, R., Bigo, V., Ireri, A., Mwangi, C., Bhattacharya, N., & Perasso, G. F. (2022). What can we learn from the Covid-19 pandemic? Resilience for the future and neuropsychopedagogical insights. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 993991. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.993991

- Paoletti, P., Di Giuseppe, T., Lillo, C., Serantoni, G., Perasso, G., Maculan, A., & Vianello, F. (2023). Training spherical resilience in educators of the juvenile justice system during pandemic. World Futures, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2023.2169569

- Paoletti, P., Perasso, G. F., Lillo, C., Serantoni, G., Maculan, A., Vianello, F., & Di Giuseppe, T. (2023). Envisioning the future for families running away from war: Challenges and resources of Ukrainian parents in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1122264. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1122264

- Perelman, A. M., Miller, S. L., Clements, C. B., Rodriguez, A., Allen, K., & Cavanaugh, R. (2012). Meditation in a deep south prison: A longitudinal study of the effects of Vipassana. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 51(3), 176–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509674.2011.632814

- Pintimalli, A., Di Giuseppe, T., Serantoni, G., Glicksohn, J., & Ben-Soussan, T. D. (2020). Dynamics of the sphere model of consciousness: Silence, space, and self. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 548813. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.548813

- Rice, T. (2016). Sounds inside: Prison, prisoners and acoustical agency. Sound Studies, 2(1), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/20551940.2016.1214455

- Ruedy, N. E., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2010). In the moment: The effect of mindfulness on ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(S1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0796-y

- Sbraccia, A., & Vianello, F. (2016). Introduzione. Carcere, ricerca sociologica, etnografia. Etnografia e Ricerca Qualitativa, 9(2), 183–210. https://doi.org/10.3240/84117

- Schroevers, M. J., & Brandsma, R. (2010). Is learning mindfulness associated with improved affect after mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy? British Journal of Psychology, 101(Pt 1), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712609X424195

- Seema, P., & Ajithkumar, V. V. (2019). Effectiveness of Vipassana meditation on communication skills of employees. SIMSARC 2018: Proceedings of the 9th Annual International Conference on 4C’s-Communication, Commerce, Connectivity, Culture, SIMSARC 2018, 17–19 December 2018 (pp. 158). European Alliance for Innovation.

- Segovia, F., Moore, J. L., Linnville, S. E., Hoyt, R. E., & Hain, R. E. (2012). Optimism predicts resilience in repatriated prisoners of war: A 37‐year longitudinal study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(3), 330–336. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21691

- Shapiro, S. L., Jazaieri, H., & Goldin, P. R. (2012). Mindfulness-based stress reduction effects on moral reasoning and decision making. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 7(6), 504–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2012.723732

- Shonin, E., & Van Gordon, W. (2016). The mechanisms of mindfulness in the treatment of mental illness and addiction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14(5), 844–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-016-9653-7

- Sica, C., Magni, C., Ghisi, M., Altoè, G., Sighinolfi, C., Chiri, L. R., & Franceschini, S. (2008). Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced-Nuova Versione Italiana (COPE-NVI): uno strumento per la misura degli stili di coping. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale, 14(1), 27.

- Skowroński, B. Ł., & Talik, E. (2018). Coping with stress and the sense of quality of life in inmates of correctional facilities. Psychiatria Polska, 52(3), 525–542. https://doi.org/10.12740/pp/77901

- Stuckless, N., Ford, B. D., & Vitelli, R. (1995). Vengeance, anger and irrational beliefs in inmates: A caveat regarding social desirability. Personality and Individual Differences, 18(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)00134-E

- Sumter, M. T., Monk-Turner, E., & Turner, C. (2009). The benefits of meditation practice in the correctional setting. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 15(1), 47–57; quiz 81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345808326621

- Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2, 17–37.

- Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 320–333. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.320

- Van de Baan, F. C., Montanari, L., Royuela, L., & Lemmens, P. H. (2022). Prevalence of illicit drug use before imprisonment in Europe: Results from a comprehensive literature review. Drugs, 29(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2021.1879022

- Van Gog, T., Paas, F., Marcus, N., Ayres, P., & Sweller, J. (2009). The mirror-neuron system and observational learning: Implications for the effectiveness of dynamic visualizations. Educational Psychology Review, 21(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9094-3

- Van Harreveld, F., Van Der Pligt, J., Claassen, L., & Van Dijk, W. W. (2007). Inmate emotion coping and psychological and physical well-being: The use of crying over spilled milk. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(5), 697–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854806298468

- Vanhooren, S., Leijssen, M., & Dezutter, J. (2018). Coping strategies and posttraumatic growth in prison. The Prison Journal, 98(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885517753151

- Vannoy, S. D., & Hoyt, W. T. (2004). Evaluation of an anger therapy intervention for incarcerated adult males. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 39(2), 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1300/J076v39n02_03

- Venditti, S., Verdone, L., Reale, A., Vetriani, V., Caserta, M., & Zampieri, M. (2020). Molecules of silence: Effects of meditation on gene expression and epigenetics. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1767. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01767

- Vuk, M., & Applegate, B. K. (2021). From future orientation to readiness for reentry: An exploratory study of prelease cognitions of incarcerated men. Incarceration, 2(3), 263266632110522. https://doi.org/10.1177/26326663211052282

- Walsh, R., & Shapiro, S. L. (2006). The meeting of meditative disciplines and Western psychology: A mutually enriching dialogue. The American Psychologist, 61(3), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.227