Abstract

This article presents results from a case study which investigated how Norwegian English foreign language (EFL) learners, roughly aged 16–17, take action through redesigning a multimodal advertisement. Data was collected from a redesign task at the end of a 16-week intervention, in which three classes were introduced to critical visual literacy practices as an integrated part of their EFL lessons. A thematic analysis of the learners’ deconstructions, multimodal redesigns and written reflections showed that the learners engaged with one or more of the themes power, diversity, identification and symbolism during the task. Utilising a variety of semiotic resources, the learners were largely successful in identify underlying ideologies in the advertisement and addressing these in their redesigns, thus creating a new version of the world which was more in line with their personal beliefs.

Introduction

Todays’ youth grow up in an increasingly globalized and digitalized world, where information and ideas are more accessible and distributed more widely, and in more forms, than ever before (Sturken & Cartwright, Citation2009). This means education needs to prepare learners to navigate an environment which is characterized by a multiplicity of modalities and an ‘increasing local diversity and global connectedness’ (New London Group, Citation1996, p. 64). I will argue, along with many other scholars (e.g. Albers et al., Citation2018; Jaeckel, Citation2018; Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006; Sturken & Cartwright, Citation2009), that visuals play a particularly important role as carriers of meaning in this environment. Firstly, people are increasingly both consumers and producers of visual texts in their everyday life through digital technologies. Secondly, visual texts, and photographs in particular, tend to be taken as credible representations of reality and are often not subjected to the same critique as verbal texts (Sherwin, Citation2008). Consequently, readers risk passively accepting messages conveyed through the multitude of visual texts they are exposed to unless they are taught to read them critically, to uncover how texts position them to accept a particular worldview, and the interests being served or disadvantaged through this positioning (Janks, Citation2010).

In English foreign language (EFL) teaching, images have traditionally been utilized as means for aiding comprehension and language learning, whereas their cultural significance and potential for critical engagement have been largely ignored (Corbett, Citation2003; Liruso et al., Citation2019). While Norway’s newly revised English subject curriculum states that learners should gain strategies for reflecting on and critically considering a wide variety of complex texts, little guidance is given to teachers on classroom practice, particularly regarding visual or multimodal texts. Likewise, although the number of studies investigating critical literacy (CL) practices in EFL classrooms is growing (e.g. Hayik, Citation2015; Lau, Citation2013; Lee, Citation2020), few of these focus on images, despite the fact that many of the visual texts learners meet in school and in their personal lives are produced in a foreign context.

Research has shown that while learners often have an intuitive, although unarticulated, understanding of design elements, such as salience and shot distance (Callow, Citation2003, Citation2020), they tend to read images at a superficial level, without recognising underlying ideologies or the particular ways images position them (Albers et al., Citation2008). However, studies which included some form of instruction have found that even younger learners can perform critical and complex analysis of visual texts given the appropriate scaffolding and the introduction of a vocabulary with which to talk about visual texts (Arizpe & Styles, Citation2003; Callow, Citation2003).

Similarly, studies have shown that the introduction of an analytical framework for deconstructing visual texts can facilitate an understanding of the intentionality behind semiotic choices and the effects these choices could have in the world (Papadopoulou et al., Citation2018) as well as the constructedness of texts (Walsh et al., Citation2007). In the latter study, however, this was not sufficient to move the primary school participants beyond superficial readings. Thus, this research appears to support the argument that visual literacy is a skill that needs to be taught (Howells & Negreiros, Citation2012), and that the development of an analytical framework for deconstruction is an important, but not sufficient, part of this (Anstey & Bull, Citation2016).

One way to provide learners with the analytical tools necessary to engage critically with images is through critical visual literacy (CVL) (Chung, Citation2013; Newfield, Citation2011), which is here understood as an approach to investigating the ‘cultural significance, social practices and power relations’ of visual texts and their context (Rose, Citation2001, p. 3). Building on the principles that all texts are constructed and that they are ideological in the sense that they work to position the reader to accept a particular worldview, CVL aims to develop the ability to interrogate and challenge ideologies inherent in the production and reading of visual texts. As such, it aims to provide the tools necessary for becoming resistant readers of visual texts, to ‘engage consciously with the ways in which semiotic resources have been harnessed to serve the interests of the producer and how different resources could be harnessed to redesign and reposition the text’ (Janks, Citation2014, p. 36, italics in original).

This study contributes to exploring critical literacies as an approach to texts in the EFL classroom, with a particular focus on the visual. More specifically, it seeks to investigate what the introduction of CVL practices allows learners to do with visual texts. Accordingly, the following research question has been posed:

In what ways do Norwegian upper secondary EFL learners change the meaning(s) of an advertisement when engaging in a redesign task after explicit critical visual literacy instruction?

Utilising data collected from a redesign task performed at the end of a 16-week case-study intervention, the study explores how CVL instruction scaffolds Norwegian EFL learners (roughly aged 16–17) in deconstructing and re-constructing a multimodal advertisement.

De-constructing and re-constructing texts through critical visual literacy

The instruction in the current study is based on Lewison, Flint and van Sluys’ (2002) model of critical social practices, as this model does not situate itself within any one orientation to CL, i.e. domination, access, diversity and design (Janks, Citation2000), but outlines social practices through which one can engage with one or several orientations depending on one’s focus. This provides flexibility and supports a dialogic approach to CL, where teachers and learners can explore problems together (Freire, Citation1970/1993). The model includes four dimensions, namely, disrupting the commonplace, interrogating multiple viewpoints, focussing on socio-political issues and taking informed action. Disrupting the commonplace entails stepping back from our normalized and naturalized worldviews, recognising texts as socially constructed re-presentations of the world, and developing the ability to read both with and against them (Janks, Citation2010).

Interrogating multiple viewpoints involves recognising the multiplicity of perspectives, i.e. that it is always possible to see things from multiple viewpoints (Vasquez et al., Citation2013). This includes asking questions such as ‘whose voices are heard and whose are absent?’ (Luke & Freebody, Citation1997), and attempting to ‘stand in the shoes of others’ (Lewison et al., Citation2002, p. 383). In focussing on socio-political issues, learners are asked to interrogate socio-political consequences of the positions on offer in images. This can be done through questioning who stands to benefit from this way of representing the world and who stands to be disadvantaged (Janks et al., Citation2014; Luke & Freebody, Citation1997).

The final dimension, taking informed action, involves drawing on the knowledge gained from engaging with the previous dimensions to instigate change. This change is both internal, i.e. understanding one’s own role in maintaining the status quo and aspiring to change it (Vasquez et al., Citation2013), and external, i.e. taking action to change something in the world. This final dimension is crucial, as without change, image deconstruction remains an academic exercise without an aim. As pointed out by Janks (Citation2014, p. 37), ‘critique is not the endpoint; transformative and ethical reconstruction and social action are’.

One way to take action is through redesign. If all texts are re-presentations of the world, to change the text is to make a change in the way we see the world, making redesign ‘an act of transformation’ (Janks et al., Citation2014, p. 8). Janks (Citation2010) has developed a model of the redesign cycle (), which shows how the act of redesigning involves a deconstruction of the original design, which in turn enables the learner to create an alternative design. The model’s cyclic form illustrates how the redesign is in itself a new design, which could (and perhaps should) be subjected to further de-construction and further re-design. The model also highlights the importance of deconstruction as a mediator between design and redesign; one ‘has to be able to read the content, form, and interests of the text, however unconsciously, in order to be able to redesign it’ (Janks, Citation2014, p. 35). An important part of this process is understanding how meaning is created (Kramsch, Citation2006), and in the context of reading images this involves developing analytical tools for deconstruction.

Figure 1. The redesign cycle (from Janks, Citation2010, p. 183).

Previous research on redesign of multimodal texts

While some studies have been conducted on redesign of verbal texts in EFL settings (e.g. Hayik, Citation2015; Lee, Citation2020), more systematic research on redesign of visual or multimodal texts has almost exclusively been conducted in first language settings. For example, Mantei and Kervin (Citation2016) analysed redesigns of a short film created by 12-year old Australian learners. They found that while many learners were successful in deconstructing and problematising the ideologies present in the original film, this was not the case for all the redesigns. Mantei and Kervin (Citation2016) conclude that the task required the learners to activate their knowledge about the world and suggest that the learners might have a limited understanding of social justice issues due to their age and life experience. Focussing on adults, Harste and Albers (Citation2013) investigated how teachers enrolled in a CL master’s program redesigned advertisements from their own context. They found that although the teachers were successful in conveying multimodal meaning, using the analytical tools provided through instruction to position ‘viewers to read the message they wished to convey’ (p. 385), some groups were less successful in disrupting traditional discourses, instead reproducing these in their redesigned advertisements.

To summarize, most research on redesign has been conducted in a first language setting, often using texts from the learners’ own context. While situating the activity in the learners’ context has many advantages (Vasquez et al., Citation2019), it does not take into account the added complexity of the global interconnectedness present in today’s digitalized world. Learners today need the ability to interpret texts from a range of contexts, and researchers and teachers need to understand more about whether and how this can be facilitated through a critical framework. The EFL classroom, with its inherent focus on texts from different contexts, seems to be a valuable, yet underutilized, arena for such practices. This study thus aims to address this research gap, while also extending our knowledge of how learners engage critically with representational modes other than traditional literature.

Methodology

The intervention

The intervention designed for the current study was conducted in an upper secondary school located in a medium-sized city on the west coast of Norway. Three first-year general studies classes, including eighty-three learners in total (38 girls and 45 boys, mean age 16) and their respective English teachers, were recruited for participation through convenience sampling. Ethical permission for the study was granted by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, and through the learners’ informed written consent before data collection started.

The intervention lasted for 16 weeks and consisted of twelve tasks (see Appendix for an overview), adding up to around 9 hours (roughly 20% of the total teaching time for the English subject during the period). The tasks were designed to integrate with the topics covered in the EFL lessons during the period, namely, ‘stereotypes, indigenous people and multiculturalism’, ‘politics and multiculturalism’, and ‘race and class’. They were also developed to address the curricular learning aims for the English subject at the time (Udir. Citation2013) and a set of learning aims developed specifically for the intervention, which were as follows:

The critically visually literate reader should:

Be aware of their own visual stereotypes and how these work.

Recognize that all texts are partial re-presentations of the worl.d

Be able to interrogate multiple perspectives.

Recognize the role of images in society.

Recognize how the choices made by image-makers and users position the viewer to respond in particular ways.

Recognise how the different elements of a multimodal text work together to create meaning.

Explore how texts can be re-designed in order to give a more just representation of the world.

Maintain a metalanguage and analytical tools to interrogate images.

Following the teachers’ classroom practices and the research project’s theoretical position, the tasks were developed and conducted from a social constructivist view of learning. Thus, active co-construction of meaning was encouraged through group and whole-class discussions, learning was in focus as opposed to performance, and the teachers’ role was to facilitate rather than instruct (Adams, Citation2006).

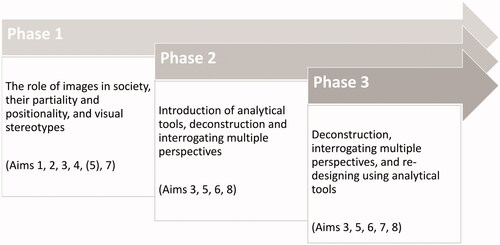

Overall, the intervention was structured around three phases (). The first phase focussed on developing awareness of the constructedness of images. As learners are often not accustomed to giving attention to visuals, they might be inclined to see them as value-neutral, leading to a resistance towards engaging in critical analysis of images (Jaeckel, Citation2018). It was therefore seen as important to provide the learners with enough time to cultivate this understanding while simultaneously drawing their attention to design elements and their potential effects, before introducing them to a more systematic framework for inquiry.

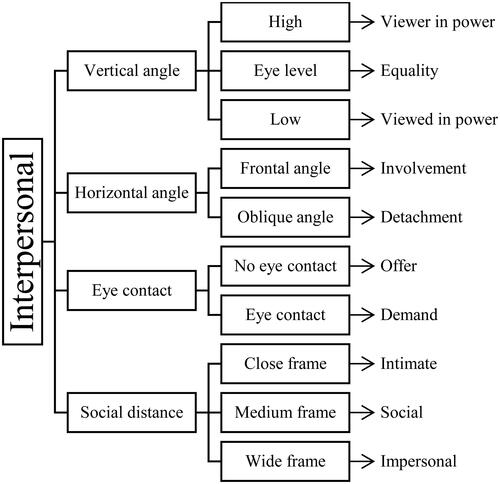

The second phase included introducing an analytical framework based on Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation2006) Grammar of Visual Design, as well as opportunities for practice. Because visual grammar is complex and requires learning (Avgerinou & Pettersson, Citation2011, p. 8), and since the intervention was limited in time, only parts of the visual grammar were introduced. The focus was given to visual grammar concepts related to the constructed relationship between the viewer and the viewed, whose emphasis on power relationships and emotional engagement strongly correlates with the CVL approach as described above. gives an overview of the introduced analytical tools, which included vertical and horizontal angles, eye contact, and social distance. It was stressed that this framework was not a formal set of guidelines to be applied to any reading (New London Group, Citation1996), but that the tools could be utilized when deemed relevant. In relation to a task requiring the learners to analyse political cartoons (see Appendix), the learners were also provided a description of some persuasive techniques, including symbolism, i.e. the use of people or objects to represent larger concepts or ideas; exaggeration, i.e. overdoing physical characteristics of people or objects to make a point; labelling, i.e. making the meaning clearer through labelling people or objects; and analogies, i.e. comparing a complex issue or situation with a more familiar one.

Figure 3. Overview of introduced metalanguage (based on Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006).

In the third and final phase of the intervention, the aim was to bring together emerging understandings of the constructedness of visual texts and the introduced analytical framework. The tasks in this phase were therefore designed with the aim of moving towards the last two dimensions of CL practices, namely focussing on socio-political issues and taking informed action (Lewison et al., Citation2002).

The advertisement redesign task

The redesign task, from which data will be presented here, was conducted at the end of the intervention, when the classes were working with the wider topic ‘race and class’. During this topic, they engaged with issues such as white privilege, redlining, and analysed political cartoons about racial issues in the US educational system. The redesign task took up a full eighty-minute lesson and was introduced by a brief lecture of about 15 minutes given by me in an auditorium with all three classes present.

The advertisement chosen for this task was from an Intel advertising campaign for the Intel Core 2 Duo processor, published in 2007. In the advertisement, a fair-skinned man (henceforth: employer) is standing in the centre of an office environment. He has his arms crossed and is looking directly at the viewer from a frontal angle. On both the left and right side of the advertisement, computer-generated duplicates of a dark-skinned man in running gear (henceforth: employees) are standing in crouching positions, facing the employer, but looking down. They are depicted from an oblique horizontal angle and have no eye contact with the viewer. A caption placed above the employer reads: ‘Multiply computing performance and maximize the power of your employees’. In response to strong criticism over the depiction of dark-skinned people as subservient, Intel tried to withdraw the campaign from the market, but one publication still printed it. Despite being over a decade old at the time of the intervention, this advertisement was chosen because of the use of semiotic resources related to the introduced analytical framework, and because of the relevance to the topic ‘race and class’.

The redesign task involved three phases: deconstruction, redesign, and reflection. Following the social constructivist approach, the learners were first given 35 minutes to discuss the advertisement in groups of 4–6. For this they were provided with a copy of the advertisement centred on an A3 piece of paper with space to make annotations around the edges. To aid in the deconstruction, the learners were given a list of question based on Stevens and Bean (Citation2007):

Who/what is represented in this advertisement?

How are they represented?

Who/what is absent or not represented?

What is the author(s) trying to accomplish with this advertisement?

Who is the target audience of this advertisement?

Who could benefit/be hurt from this advertisement? Why?

Are there any problems, anything that could have been done better? How?

Following this, the learners worked individually to sketch a redesign of the advertisement based on the issues they had identified as problematic. The aim was not to produce a refined product, but to explore different ways in which the advertisement could be structured. They were then asked to write a reflection about the changes they had made to the redesigns, the reasons for these changes, and how they thought this had improved the original advertisement.

Data collection and analysis procedures

Data was collected from the learners who had consented and included (1) annotated advertisements completed in groups; (2) individual redesigns; and (3) individually written reflections. Regarding the annotations, data could only be collected from the groups in which all learners had consented. The data from this part of the task therefore consists of 10 annotated advertisements, from a total of 41 learners. Additionally, the data set includes 54 individually drawn redesigns and 54 accompanying reflections.

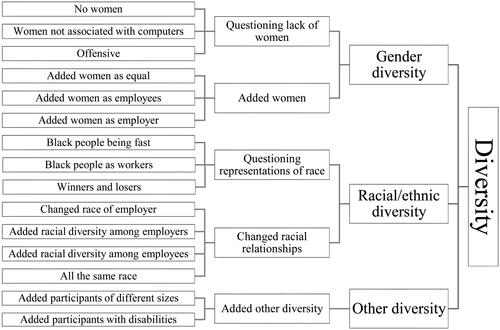

In order to analyse the three parts of the data set in such a way that I could take into account their individual nature and modality, but also synthesize the results to address the research question, thematic analysis was deemed most productive. Drawing on Braun and Clarke's (Citation2006) six phases of thematic analysis, I first familiarized myself with the data set through transcribing the verbal texts and reading and re-reading the data set while making notes of salient aspects and potential themes. The transcriptions and redesigns were then coded systematically using NVivo 12 pro (version 12.6.0.959), utilising both deductive and inductive codes (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2007, p. 565). The deductive codes consisted of concepts that had been introduced through instruction (), whereas the inductive codes derived from the data itself. In the next phase of the analysis, the codes were revisited to ensure internal consistency, before the codes were sorted into one or two levels of categories, and finally broader level themes (). The relationship between codes, categories and themes was then explored through the development of a thematic map. Finally, the entire data set was re-read to ensure that the themes were representative of the data set as a whole and coding items left uncoded during previous coding cycles.

Figure 4. Example of progression from codes, through first- and second-level categories and finally theme.

Many codes were transferrable between the different modes. For example, a focus on angle was identified in the annotations through explicit references. In the redesigns, the same could be identified through semiotic analysis (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006) when the redesigned advertisement had made any changes in the angles from the original. Finally, a reference to angles in the reflections was also sometimes accompanied by an explanation of why they thought this was important and/or the effect of the change. Taken together, the three data sources provide a more holistic overview of the thought processes behind the redesigns, including which meanings they focussed on changing, and how and why they chose to change them.

Analysis and results

Four main themes were generated through the analysis: power, identification, diversity, and symbolism (described below). Responses show that the learners all engaged with one or more of these themes in their redesigns to change the meaning of the original advertisement.

gives an overview of how the themes were represented in the different parts of the data set. In the following, the themes will be presented separately, including information about the overall results as well as more detailed analyses of a selection of redesigns to illustrate some of the findings.

Table 1. Distribution of themes within the three parts of the data set.

Engaging with power

Power was a prominent theme in the data set, and consisted of two categories, namely, internal and external power relationships. The external power relationship attends to how the viewer is being positioned in relation to the participants and the power relationship which is simulated based on this. Seven groups mentioned eye-contact in their annotations, ranging from mechanical deconstructions, e.g. ‘eye contact (-> demand)’ (Group 5), to more elaborate comparisons, e.g. ‘he [the employer] has eye contact and makes the demands. While the black people do not have eye contact which makes them on “offer”.’ (Group 3). Three groups mentioned vertical angle, also making comparisons: ‘white man is in eye-level, we see the black men from above, which makes them small’ (Group 9).

Equally prominent in the annotations was a focus on internal power relationships. The groups all identified the employer as being most powerful in the advertisement, describing him as ‘the boss’, ‘powerful’, and ‘dominating’. Conversely, the employees were described as ‘workers’ and ‘slaves’. Furthermore, the learners translated the action in the picture as ‘they [the employees] are kneeling down at the white man’ (Group 1). The relationship between the two groups of participants was therefore deconstructed as being intimately connected with power relationships. Some groups also suggested that the representation of this particular fair-skinned man as powerful could represent ideas about race as a whole, e.g. ‘[d]ominant race: white’ (Group 7), and other groups labelled the advertisement ‘[r]acist’ (Group 5 and 10) and ‘[w]hite supremacy’ (Group 5). Additionally, three groups connected the internal power relations and slavery: ‘[c]oloured “slaves” kneeling for the white’ (Group 2). One learner wrote in his reflection that he had removed the sprinters ‘because the people kneeling may remind people of the slavetime and that subject can hurt someone’ (Leonard, all names are pseudonyms).

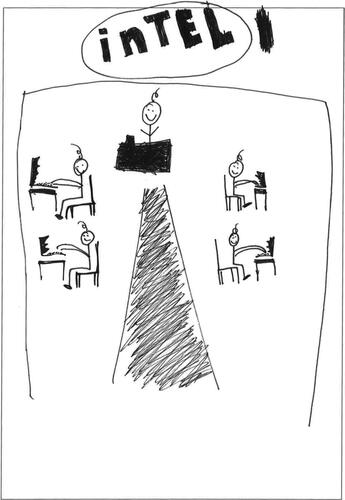

Several different approaches to addressing the power relationship issues outlined above were identified in the redesigns. External power relationships were altered through depicting the employees from an eye-level vertical angle (N = 32), and/or with eye contact (N = 25). In relation to addressing internal power relationships, a common tactic was to make the employees sit up (N = 7) or stand (N = 27). Additionally, eleven learners chose to remove the employer from the advertisement, depicting only employees, and thus circumventing internal power differences altogether. One of the redesigns focussing on both external and internal power relationships was Anne’s. In her redesign (), Anne changed the internal power relationships through drawing everyone sitting up, and the external power relationships by depicting all participants from an eye-level vertical angle and demanding eye-contact from the viewer. In her reflection, Anne wrote ‘[t]he changes I made was that the boss was at the same level as the workers’.

It is interesting, however, that while many learners wrote that they made the employer equal to, or on the same level as, the employees, they still made him stand out in some way. In Anne’s redesign, for instance, the vectors formed by the pathway lead the viewers’ gaze towards the employer, whose salience is further enhanced by standing behind a dark desk. Thus, the implied reading path asks the viewer first to see the employer, whose eye-contact and smile demand the viewer to enter into a social relationship with him (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006, p. 118). The other participants are positioned along the sides of the vectors and are thus the secondary focal point in this structure. One can therefore question whether Anne’s aim to position the employer ‘at the same level as the workers’ has been fully achieved through the chosen redesign. Other redesigns which aimed for equality depicted the employer in the centre and/or as significantly larger than the other participants, making him more salient. The fact that many learners wrote that there was equality between the two groups of participants, while still representing them as visually different, might indicate that this was not necessarily a conscious choice. For example, only two groups (Group 9 and 10) mentioned the fact that the fair-skinned man was in the centre in their annotations, indicating a beginning awareness or an intuitive understanding that the centre position carries some meaning. However, neither group elaborated on the effects of this particular positioning.

Engaging with diversity

Within the theme of diversity, the main issues identified were related to stereotypes denoted from representations of race in the original advertisement, and the lack of women and ethnic diversity. Three categories were included, namely gender, race/ethnicity, and other diversity (size, disabilities etc.). In relation to the first category, three groups mentioned and/or questioned why there were no women, and Group 7 suggested women could be offended by this and connected it to stereotypes and the wider socio-political context by stating ‘[w]omen are not associated with computers and intelligence’.

Eighteen learners chose to add women to their redesigns, and fifteen of these included a mention of gender in their reflections. The main argument was that they added women to create equality, one learner stating that she ‘wanted to have a more equal workplace for the advertisement, since I know that advertisements have an effect on the society’ (Nina). Interestingly, in eleven of these redesigns, women were added in combination with removing the employer, thus indeed creating a more equal presentation of the different participants. Of the remaining seven redesigns, however, only one included a female employer, arguing that ‘I put women [as the leader] to show that women has [sic] as much power as men do in this leader role’ (Olivia).

In relation to race, two stereotypes were identified in the annotations, namely ‘black people being fast’ (Group 4) and ‘black people are always employees (workers)’ (Group 10). In relation to the latter stereotype, Group 5 explicitly addressed underlying ideologies represented in the advertisement when they annotated that the ‘[a]dvert implies that employers are white and employees/workers are black’. They furthermore suggested that socio-political consequences of this might be oppression of ‘black people’ and that ‘[w]hite people benefit from it’.

Twenty-five redesigns addressed racial diversity. In contrast to the findings within gender diversity, six of these included a dark-skinned employer. Only four redesigns in this category had a fair-skinned employer as the only employer. Some learners argued that by changing the employer’s and/or the employees’ skin colour, the advertisement ‘cannot be misinterpreted as stereotyping’ (Oscar). For these learners, it can be deduced, the power difference between employer and employees was not the main issue, but their respective skin colours. Similarly, six learners chose to leave out diversity altogether, depicting only fair-skinned males, arguing ‘that way it can’t be racist’ (Malin). Such an argument seems to overlook the problem of not being represented that other learners identified in relation to lack of women.

Other redesigns focussed on representing ethnic variety, often also in combination with gender and/or other diversity. Like the redesigns focussing on levelling out internal power relations, these redesigns were often argued to ‘picture [everyone] as equal’ (Ronja), and the participants were consequently often positioned identically. One such example is Caroline’s redesign (), where six people were positioned in a line. From the clothes and hair, we can guess that half are female, and the shaded faces suggest a variety of skin colours. They are similar in size and are depicted from the same angle and social distance. In her written reflection, Caroline wrote ‘they are all standing together, no one smarter than the other, equal’.

Engaging with identification

Identification here refers to who the viewer is asked to identify with and includes three categories, namely, horizontal angle, eye-contact, and target audience. In the annotations, only two groups mentioned horizontal angle, focussing either on the employees being ‘[d]etached from the viewer’ (Group 7) or on the employer’s frontal angle implying involvement (Group 5), neither group comparing the employer and employees. Four groups mentioned eye-contact in relation to this theme, and here comparisons were more prominent. In relation to the last category, three groups included annotations about the target audience, all three identifying this as being employers or businesses.

While this theme was not very prominent in the annotations, forty of the fifty-four learners chose to address identification in their redesigns. Twenty redesigns depicted all the employees with eye contact and from a frontal angle. Others depicted the employees from an oblique angle, but with their face turned towards the viewer and establishing eye contact, and only six redesigns kept the original structure wherein the viewer was to identify only with the employer. The horizontal angle and eye-contact therefore seemed to be important to the learners, although only two learners explicitly addressed identification in their reflections. One of these was Kasun, who wrote that he ‘felt like [the original advertisement] was targeting only big companies and business places’ and did not have ‘the younger generation, who use computers in their daily lives in mind’. In his redesign he chose to address this, wanting to depict the ‘struggles both young and old people [have] with computers and our frustrations that come with it’.

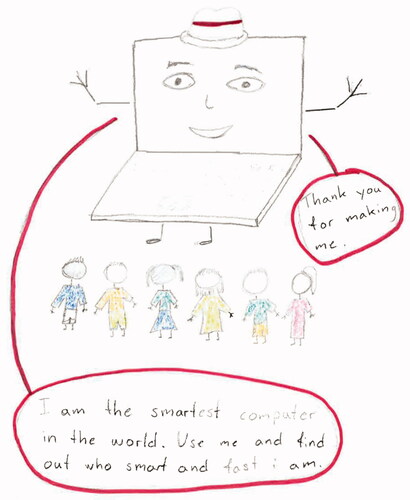

In his redesign (), which is almost structured like a comic with invisible lines between the panels and can be read from top to bottom, left to right, he tells a compelling story of the ‘frustrations that come with’ computer usage. At the top left, he has drawn a laptop computer with a person standing next to it with a confused look. Further to the right, another person was drawn crying. An arrow between the two people indicates a causal or temporal process; the frustration led to, or was followed by, despair. A verbal message then introduces the viewer to the solution, namely that Intel can solve ‘all problems related to slowing down of your computer’. Below the verbal text, the person is drawn standing with a smile on their face and holding an Intel product. Finally, the drawing on the bottom shows the person with a wide smile next to a computer with Intel written on the screen. Hearts and the exclamation 'whoooo’ indicate a blissful state. In terms of identification, Kasun positioned the viewer to be involved with all participants, but only to engage in a social relationship with the first drawing through the establishment of eye-contact. The reader is therefore asked to connect with the ‘frustrated’ person, while the continuation of the story is someone ‘like you’; someone you might be if you buy this product. Kasun here displayed a creativity in his utilisation of semiotic resources, predominately from comics, to create a message which is largely conveyed through visual means. He also successfully changed the target audience by altering who the reader is asked to identify with and his reflections show he is largely aware of this.

Engaging with symbolism

Several groups displayed an awareness of the advertisements’ intended message in their annotations; that the sprinters were supposed to symbolize speed, either as representing ‘increased processing power’ (Group 7), or as representing the speed at which employees could work with this new processor (Group 5 and 8). However, they also exposed stereotypes conveyed through using dark-skinned sprinters as a symbol of speed. For example, Group 1 suggested in their annotations that the sprinters could be changed to ‘[o]ther fast-going things. To avoid stereotypes’. Some learners were also concerned with the relevance of sprinters to the work environment, stating that a ‘running position […] has nothing to do with an office’ (Group 5).

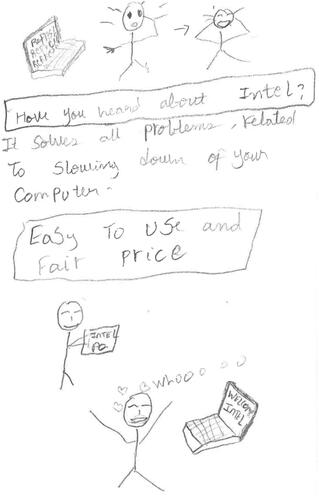

In their redesigns, the learners chose to address symbolism in three ways, corresponding with the categories changing visual symbol of speed, conveying speed verbally, and changing message. Within the first category, in which twenty-five redesigns were coded, some learners chose to replace the sprinters as a visual symbol of speed with, for example, fast animals or cars. Others conveyed speed visually through, for example, utilising action lines to indicate motion (McCloud, Citation1994), or through visually comparing the processor with previous models. Ten learners chose to convey speed and productivity through drawing employees working. One of these was Hanna, who argued that by drawing employees behind computers, looking ‘like they are talking to costumers’ would make them seem ‘efficient and productive’. She argued that she thought Intel ‘should have known that this advertisement could potentially offend’ non-whites, and that this was particularly problematic ‘because Intel is an American company’, pointing to the problems with racism in America. Similar to other reflections in this category, changing the advertisement’s symbolism was therefore argued to be one approach to dealing with the racist issues they identified. Redesigns coded within ‘conveying speed verbally’ also stayed true to the intended message, but instead of a visual symbol, conveyed this verbally through, for example, changing the slogan, labelling or speech bubbles (e.g. and ).

Redesigns in the category ‘changing message’ did not focus on the speed or productivity of the processor and/or employees. Instead, they either intentionally changed the message, or appeared not to focus on any particular message at all. For example, several redesigns seemed so concerned with depicting equality, they had no traces of an advertising message for computers.

Discussion and conclusions

The current study set out to explore the ways in which Norwegian upper secondary EFL learners engage with and transform the meaning(s) of an advertisement through a redesign task after explicit CVL instruction. Through their engagement in the task, the learners demonstrated their ability to read both with and against the text (Janks, Citation2010). Reading with the text, they decoded the intended meaning of the advertisement and saw the sprinters as symbolising the processor’s speed. As resistant readers, the learners focussed on how the message was constructed and which implied meanings can be deduced from this. Therefore, unlike the findings in previous research in which no instruction was provided (Albers et al., Citation2008), the participants were also able to decode underlying ideologies, such as how the power imbalances between the participants in the advertisement could be perceived as racist, and stereotypical portrayals of gender and race, discussed during Phase 1 of the instruction.

Engagement within all four dimensions of CVL practices was evident in the learners’ responses. The learners disrupted commonplace ways of viewing the world and demonstrated an emerging awareness of how meaning is constructed through semiotic resources, for example when they used the analytical tools introduced through instruction to deconstruct the effects of angles and eye contact. Their redesigns also displayed an understanding of how different semiotic resources could be utilized to convey alternative meanings. Thus, they are displaying both an awareness of how meaning is created, and an ability to create meaning through these means (Kramsch, Citation2006). These findings are consistent with previous research which has showed that the introduction of an analytical framework can facilitate an understanding of the constructedness of visual texts (Papadopoulou et al., Citation2018; Walsh et al., Citation2007). In the current study, however, the introduction of the analytical tools was integrated into a larger critical framework, which was also used to scaffold the learners during task performance. In addition to the age difference, this could explain why the learners went beyond superficial readings, unlike the primary school learners in Walsh et al.’s study (2007).

The results show that the learners interrogated multiple perspectives, for example by questioning absent voices (Luke & Freebody, Citation1997), such as women and other ethnicities, through their engagement with diversity, or by trying to ‘stand in the shoes of others’ (Lewison et al., Citation2002, p. 383), imagining how these groups might react to the advertisement. Both of these approaches were discussed and practiced during Phase 3 of the intervention. The multiple ways in which the learners chose to change the original advertisements in their redesigns also attest to their willingness to consider alternative perspectives.

Similarly, the learners’ responses indicated an awareness of the wider socio-political consequences of the representation (Lewison et al., Citation2002), which allowed them to deconstruct the advertisement from perspectives outside of their own context. For example, when the learners described the power imbalances in the advertisements and linked these to slavery, they had to activate their knowledge about the advertisement’s context. They also showed an awareness of the consequences of this when they suggest that ‘white people’ benefit. During the intervention, the learners had worked with racism issues in the US from historical and current perspectives. What the learners are demonstrating is their ability to use this knowledge in their interpretation of a particular advertisement, showing an awareness of how production and reading of visual texts are situated in and contribute to reproducing certain ideologies. Thus, a more integrated approach, in which the CVL instruction and tasks were closely linked to the topics the learners were working on for longer periods of time, may have contributed to the learners’ wider understanding of the socio-political context and the related social justice issues, identified as lacking in Mantei and Kervin (Citation2016) study.

In their redesigns, the learners displayed a willingness and ability to engage in social action, showing both imagination and creativity in addressing the identified issues, for example, by utilising comic-based semiotic resources. Using the analytical tools provided through the intervention, learners changed the participants’ positions in order to level out power relationships they saw as problematic, and/or the level of identification the viewer was encouraged to have with the different participants. They also addressed issues of diversity through including a more varied set of participants, and deliberately changed the advertisement’s symbolism so that the messages conveyed were more in line with their personal beliefs and views.

However, unlike the teachers in Harste and Albers' (Citation2013) study, these learners were not always completely successful in conveying the meanings they wanted to, possibly due to the difference in age and experience with CL practices. An example is when the learners communicated a desire to create equality between the employer and the employees, yet represented them as visually different in relation to, among other things, salience and the centre position. As visual grammar elements such as information value and salience had not been introduced as part of the analytical framework in the intervention, it is possible that the learners did not notice these elements to the same extent. For example, only two groups mentioned the centre position in their annotations, but without further elaboration. As such, it might be that due to lack of explicit instruction, the value of the centre remained a vague and unarticulated understanding (Callow, Citation2003; Callow & Buch, Citation2020; Cloonan, Citation2011), and therefore did not enter into the resource pool from which the learners could draw in their redesigns.

Similar to Harste and Albers' (Citation2013) findings, the results also indicate that the learners were not always successful in disrupting traditional discourses, and there was little evidence of critical reflection of their personal positions. For instance, while many learners added women to their redesigns, they rarely placed them in the employer position. This scarcity might be reflective of general societal trends in Norway, in which gender equality is treated as already accomplished, although gender imbalances in work life are still present, thus creating a ‘blindness’ to certain gender inequalities (Handal, Citation2020). Similarly, the strong focus on equality found in the data could be related to the egalitarian ideals upon which Norwegian society is built (Skarpenes & Sakslind, Citation2010), with equality of wealth and opportunities being perceived as essential to a just society. However, while some superficial reflections about their own position could be identified, the responses showed little evidence of critical reflection of their own ideologies, or of unpacking ‘the position(s) from which [they] engage in literacy work’ (Vasquez et al., Citation2019, p. 307).

This article has argued for the utilisation of CVL in the EFL classroom as an approach to provide learners with rich opportunities for navigating our globally interconnected and multimodal society. Particularly, the EFL classroom’s inherent engagement with issues outside of the learners’ own context allows a more integrated approach, where learners can use their knowledge in their attempts to make sense of and critique visual texts. The findings from this small-scale case study have demonstrated that even with a relatively short CVL instruction, the learners were largely successful in deconstructing underlying ideologies in the advertisement and connecting this to their wider knowledge of the world, as well as taking action to challenge these through redesign.

Being able to re-imagine the world, thus breaking with the worldviews which they have been socialized into over many years, is a challenging and complex task, and one which is perhaps difficult to achieve in the time-span of the intervention described here. Given this complexity, and the limited time allotted to individual subjects, the EFL classroom is only one of the places in which CVL practices could be included. As the results from the current study has indicated, critical reading and production of images can be supported by instruction, but this requires time. Furthermore, the learners’ understanding of social justice issues might expand with the introduction of perspectives from different subject areas. Future research might therefore want to consider investigating cross-curricular and/or more longitudinal approaches. Additionally, the current study investigated redesigns in a time-limited task. Thus, many of the redesigns were unfinished, and the learners might have prioritized the issues they saw as most important, perhaps overlooking other, less dominant, deconstructions. A potential avenue for exploring this further could be to take the redesigns into another cycle (Janks, Citation2010), allowing the learners to analyse and critique their own and their peers’ redesigns and through this perhaps also gain a better understanding of their own role in challenging the status quo (Vasquez et al., Citation2013).

| List of abbreviations | ||

| CL | = | critical literacy |

| CVL | = | critical visual literacy |

| EFL | = | English foreign language |

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, P. (2006). Exploring social constructivism: Theories and practicalities. Education 3–13, 34(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270600898893

- Albers, P., Harste, J. C., Vander Zanden, S., & Felderman, C. (2008). Using popular culture to promote critical literacy practices. 57th yearbook of the National Reading Conference,

- Albers, P., Vasquez, V., & Harste, J. C. (2018). Critically reading image in digital spaces and digital times. In K. A. Mills, A. Stornaiuolo, A. Smith, & J. Z. Pandya (Eds.), Handbook of writing, literacies, and education in digital cultures (pp. 223–234). Routledge.

- Anstey, M., & Bull, G. (2016). Pedagogies for developing literacies of the visual. Practical Literacy: The Early and Primary Years, 21(1), 22.

- Arizpe, E., & Styles, M. (2003). Children reading pictures: Interpreting visual texts. RoutledgeFalmer.

- Avgerinou, M. D., & Pettersson, R. (2011). Toward a cohesive theory of visual literacy. Journal of Visual Literacy, 30(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2011.11674687

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Callow, J. (2003). Talking about visual texts with students. Reading Online, 6(8), 1–16.

- Callow, J. (2020). Visual and verbal intersections in picture books – multimodal assessment for middle years students. Language and Education, 34(2), 115–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2019.1689996

- Callow, J., & Buch, B. (2020). Making meaning using a metalanguage: Grammar and international curricula. The Reading Teacher, 73(5), 669–677. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1889

- Chung, S. K. (2013). Critical visual literacy. The International Journal of Arts Education, 11(2), 1–36.

- Cloonan, A. (2011). Creating multimodal metalanguage with teachers. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 10(4), 23–40.

- Corbett, J. (2003). An intercultural approach to English language teaching. Multilingual Matters.

- Council of Europe (2013). Images of others: An autobiography of intercultural encounters through visual media. https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/autobiography/Source/AIEVM_en/AIEVM_autobiography_en.pdf

- Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum. (Original work published 1970)

- Handal, M. (2020). Vi … er på vei inn i en ny tidsalder der det i stor grad er kvinnekjønnet som setter premissene for sammfunsutviklingen” – en kritisk analyse av laerebøker i samfunnsfag. Nordidactica - Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 3, 88–108.

- Harste, J. C., & Albers, P. (2013). I’m riskin’it”: Teachers take on consumerism. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56(5), 381–390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/JAAL.149

- Hayik, R. (2015). Diverging from traditional paths: Reconstructing fairy tales in the EFL classroom. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 9(4), 221–236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2015.1044084

- Howells, R., & Negreiros, J. (2012). Visual culture (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

- Jaeckel, K. S. (2018). Pedagogical strategies for developing visual literacy through social justice. In B. T. Kelly & C. A. Kortegast (Eds.), Engaging images for research, pedagogy, and practice (pp. 105–118). Stylus Publishing, LLC.

- Janks, H. (2000). Domination, access, diversity and design: A synthesis for critical literacy education. Educational Review, 52(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/713664035

- Janks, H. (2010). Literacy and power. Routledge.

- Janks, H. (2014). The importance of critical literacy. In J. Z. Pandya & J. Ávila (Eds.), Moving critical literacies forward: A new look at praxis across contexts (pp. 32–44). Routledge.

- Janks, H., Dixon, K., Ferreia, A., Granville, S., & Newfield, D. (2014). Doing critical literacy: Texts and activities for students and teachers. Routledge.

- Kramsch, C. (2006). From communicative competence to symbolic competence. The Modern Language Journal, 90(2), 249–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00395_3.x

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Lau, S. M. C. (2013). A study of critical literacy work with beginning English language learners: An integrated approach. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 10(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2013.753841

- Lee, Y. J. (2020). What today’s children read from “happily ever after” Cinderella stories. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 2020, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2020.1781641

- Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 557–584. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1045-3830.22.4.557

- Lewison, M., Flint, A. S., & Van Sluys, K. (2002). Taking on critical literacy: The journey of newcomers and novices. Language Arts, 79(5), 382–392.

- Liruso, S., Cad, A. C., & Ojeda, H. (2019). A multimodal pedagogical approach to teach a foreign language to young learners. Punctum, 5(1), 138–158.

- Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1997). Shaping the social practices of reading. In A. Luke & P. Freebody (Eds.), Constructing critical literacies: Teaching and learning textual practice (Vol. 6, pp. 185–225). Allen & Unwin.

- Mantei, J., & Kervin, L. K. (2016). Re-examining “redesign” in critical literacy lessons with grade 6 students. English Linguistic Research, 5(3), 83–97.

- McCloud, S. (1994). Understanding comics: The invisible art. Harper Collins.

- New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u

- Newfield, D. (2011). From visual literacy to critical visual literacy: An analysis of educational materials. English Teaching, 10(1), 81–94.

- Papadopoulou, M., Goria, S., Manoli, P., & Pagkourelia, E. (2018). Developing multimodal literacy in tertiary education. Journal of Visual Literacy, 37(4), 317–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1051144X.2018.1540177

- Rose, G. (2001). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. Sage.

- Sherwin, R. K. (2008). Visual literacy in action: Law in the age of images. In J. Elkins (Ed.), Visual literacy (pp. 179–194). Routledge.

- Skarpenes, O., & Sakslind, R. (2010). Education and egalitarianism: The culture of the Norwegian middle class. The Sociological Review, 58(2), 219–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2010.01901.x

- Stevens, L., & Bean, T. (2007). Critical literacy: Context, research, and practice in the K-12 classroom. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452204062

- Sturken, M., & Cartwright, L. (2009). Practices of looking: An introduction to visual culture. (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Utdanningsdirektoratet (Udir.) [Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training] (2013). English subject curriculum. http://data.udir.no/kl06/ENG1-03.pdf?lang=eng

- Vasquez, V. M., Janks, H., & Comber, B. (2019). Critical literacy as a way of being and doing. Language Arts, 96(5), 300–311.

- Vasquez, V., Tate, S. L., & Harste, J. C. (2013). Negotiating critical literacies with teachers: Theoretical foundations and pedagogical resources for pre-service and in-service contexts. Routledge.

- Walsh, M., Asha, J., & Sprainger, N. (2007). Reading digital texts. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 30(1), 40–53.

- Yang, G. L. (2006). American Born Chinese. St. Martin’s Press.