Abstract

Many persuasive messages intermingle images with text. Readers who wish to interpret such messages must grapple with the information in both modalities as well as the relationship between them. One instance of this occurs in modern advertising, which is predominantly visual with verbal text assuming a supporting role. The text functions to anchor the meaning of the image, thereby guiding the reader to the preferred conclusion. However, little is known about how variations in verbal anchoring produce meaning and persuasion. To address this knowledge gap, the present study sketches a model of message processing in which perceived interpretational guidance is the key explanatory mechanism. A repeated measures experiment (N = 304) finds that verbal anchoring (complete vs. moderate vs. none) is positively related to perceived interpretational guidance, regardless of the complexity of an ad’s image (straightforward vs. visual rhetorical figure). Moreover, perceived interpretational guidance explains the effects of verbal anchoring on persuasion. Findings suggest that complete anchoring should be preferred over moderate or no anchoring because people value the cognitive efficiency associated with being guided in their interpretation of the ad’s visual imagery.

Addressing significant social problems, such as public health, climate change, and environmental pollution, depending on their success in the creation of effective persuasive messages (Atkin & Rice, Citation2013). Over the past decades, a remarkable shift in the use of imagery and text has taken place in these messages (Kjeldsen, Citation2012). As evidenced by several content analyses, the emphasis on images over words has continuously increased (McQuarrie & Phillips, Citation2008; Pollay, Citation1985; Pracejus et al., Citation2006). It is now common for imagery to take the thematic spotlight with text assuming more of a supporting role (Phillips, Citation2000). This trend is interpreted as an indication that we are living in an increasingly visual society in which we are losing our patience with written words (Machin, Citation2014; Pierson, Citation2013).

From a visual literacy perspective, this raises fundamental, yet rarely addressed questions about message processing. Being visually literate requires processing visual and verbal information together, then integrating them into a coherent whole (Pettersson, Citation2007; Williams, Citation2019). What remains largely unknown is how variation in the amount of verbal copy influences sense-making and persuasion. Should the text give a hint at the preferred meaning of the image instead of completely spelling out its meaning? Or, should the verbal copy be eliminated altogether?

Using a visual literacy lens, this paper proposes a compact model of message processing that enables clear and testable answers to these questions. It supposes that the primary function of verbal anchoring is to guide readers towards the interpretation preferred by the message source. The model further posits that this guidance function can affect the persuasiveness of verbal anchoring – either positively or negatively – depending on which of two basic message processing dynamics is prepotent. The study also takes into consideration that the complexity of an ad’s image might influence whether readers perceive verbal anchoring as more or less constraining. Before we unpack the theoretical model, we present the visual literacy lens underlying this paper and the key message variable under scrutiny: verbal anchoring.

Theoretical background

Verbal anchoring

Given the increasingly visual society in which we live, visual literacy is considered a key literacy to successfully navigate the everyday challenges of the 21st century (Avgerinou, Citation2009). Being visually literate involves ‘a group of largely acquired abilities, i.e. the abilities to understand (read), and use (write) images, as well as to think and learn in terms of images’ (Avgerinou, Citation2001, p. 26). Since visual imagery mostly occurs in combination with verbal text, visual literacy also requires processing information encoded in both modalities and integrating them into one coherent whole (Pettersson, Citation2007; Williams, Citation2019). This takes place in a complex sense-making process, in which the two modes fulfill complementary functions (Geise & Baden, Citation2015). Specifically, verbal information is associated with an anchoring function that disambiguates the meaning of the image.

Verbal anchoring, a concept that can be traced to Barthes (Citation1977), refers to the degree to which the ad copy explains the meaning of the accompanying image. The contemporary theory holds that verbal anchoring can be understood as a continuum (Phillips, Citation2000). No anchoring occurs when an ad contains an image but lacks any verbal copy except for the brand or product name. Moderate verbal anchoring refers to the presence of a word or phrase that hints at the meaning of the image (Phillips, Citation2000). An instance of moderate verbal anchoring can be found in an Amnesty International ad campaign (Ads of the World, Citation2010). The ad shows a man who is being beaten by armed militia, while people are gathering around in circle formation. The people stand with their backs against the centre and hence look away. The verbal text anchors the meaning of the image by stating ‘ignore us ignore human rights’. Complete verbal anchoring describes the presence of verbal text that explicitly spells out the meaning of the image (Phillips, Citation2000). The Child Health Foundation uses complete verbal anchoring in one of its anti-smoking ads (Ads of the World, Citation2007). The ad depicts a girl with a smoke halo over her head, with a headline explaining that ‘children of parents who smoke, get to heaven earlier’.

Verbal anchoring performs a guidance function: It increases the comprehensibility of an ad and leads readers towards the intended meaning of the message advocacy (Lagerwerf et al., Citation2012). This ability to guide readers’ interpretation was demonstrated in van Enschot and Hoeken (Citation2015), who examined consumer response data for 153 TV commercials. They found that complete verbal anchoring was perceived as more comprehensible than commercials containing moderate verbal anchoring. Two experimental studies (Bergkvist et al., Citation2012; Phillips, Citation2000) on the effects of verbal anchoring in commercial print advertising point in the same direction. Both investigations found that complete verbal anchoring helped readers to better understand the ad. Similarly, Lagerwerf et al. (Citation2012) showed in an experimental study on print advertising that readers more often discerned the intended interpretation when exposed to complete verbal anchoring compared to no verbal anchoring.

Comprehending an ad and discovering its intended meaning likely go hand-in-hand with perceptions of being guided. It is straightforward to assume that people consciously notice that verbal anchoring pushes them towards certain inferences. This brings us to the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The higher the amount of verbal anchoring, the greater the perceived interpretational guidance.

The present study takes into consideration that visual complexity might influence whether readers perceive verbal anchoring as more or less constraining.

Visual complexity

Visual complexity refers to a property of images that determines the level of cognitive load required for readers to process the ad (Phillips & McQuarrie, Citation2004). This concept is best conceived as a set of ordered categories. The least complex images are straightforward, in that they articulate literal meanings (i.e. matter of fact depictions of reality) (Huhmann, Citation2018; van Mulken et al., Citation2005). An example is an ad of the Shelter Pet Project showing a dog (Petfinder, Citation2014). More complex images come in the form of rhetorical figures (Phillips, Citation2000). This term describes artful deviations from the expectation that are not rejected as nonsensical (McQuarrie & Mick, Citation1996). One example is that of an image of a melting penguin, implying that polar animals will lose their natural habitat and eventually die out due to global warming. Although penguins cannot actually melt, readers do not perceive this as an error but rather understand it as a fusion of two concepts.

Phillips and McQuarrie (Citation2004) assert that some visual rhetorical figures are more complex than others due to the manner in which they structure the relationship between the visual elements. The least complex option is juxtaposition, which involves a side-by-side arrangement that implicitly instructs viewers to make a comparison (AdForum, Citation2017). Fusion is the blending or merging of elements (Ads of the World, Citation2011). It is more complex than juxtaposition because one must derive the meaning of the two elements alone and together. Replacement occurs when one element appears in place of the other (Ads of the World, Citation2009). Replacement is the most complex type because one must substitute the element that is present with an element that is visually absent.

Previous research supports the idea that these visual complexity categories are ordered in terms of the cognitive demands that they place on the readers (Gkiouzepas & Hogg, Citation2011; van Mulken et al., Citation2014). For instance, participants in an experimental study consistently identified ads with straightforward images as the least complex type, followed by ads with juxtaposition and fusion figures, which were in turn followed by replacement figures (van Mulken et al., Citation2010).

This study explores the possibility that visual complexity influences how much readers perceive verbal anchoring to push them towards certain interpretations. We speculate that verbal anchoring is perceived as relatively more constraining when paired with a less vs. more complex image. This is because less complex images are easier to understand, even without the aid of verbal description. Verbal anchoring thus offers interpretational guidance that is not necessarily required and that might increase readers’ perceptions of being constrained in their reading of the ad. We therefore posit the following research question:

RQ1: Does visual complexity influence readers’ perceptions about the amount of perceived interpretational guidance offered by verbal anchoring?

The purpose of this study is to examine what amount of verbal anchoring is most persuasive. We argue that perceived interpretational guidance is the central explanatory mechanism underlying the effects of verbal anchoring. We further maintain that the effects of interpretational guidance are governed by two principles of message processing.

Principles of message processing

Need for sense-making

The first principle asserts that people possess an innate need to make sense of their experiences, their lives, and the world (Chater & Loewenstein, Citation2016). This desire to understand one’s physical and social world is the product of an evolutionary design process that ‘motivates people to gather, attend to, and process information in a fashion that augments, and complements, autonomous sense-making’ (Chater & Loewenstein, Citation2016, p. 137). However, people are minimalist in that they try to invest as little effort as required to understand information and often stop sense-making processes after having found the first relevant interpretation (Forceville, Citation2014; Sperber & Wilson, Citation1986).

Sense-making operates via pleasure and aversion mechanisms. Pleasure arises when one can make sense of information (Chater & Loewenstein, Citation2016). The aha moment evokes a pleasurable sense of achievement (Jeong, Citation2008). In contrast, the inability to make sense of information is aversive and causes frustration (Chater & Loewenstein, Citation2016).

The first principle has clear implications for the persuasive effects of verbal anchoring. We should expect that anchoring would aid sense-making by guiding the reader’s interpretation and, in doing so, produce greater persuasion. The underlying assumption is that the interpretational guidance offered by verbal anchoring meets people’s need to comprehend the world around them: it facilitates the pleasurable experience of ‘getting’ what the ad says while minimizing cognitive effort. The more readers feel guided in their interpretation, the more favourable they should be towards message advocacy. We therefore assume that:

Hypothesis 2: Perceived interpretational guidance positively predicts persuasion.

Need for autonomy

The second principle, rooted in theories of psychological reactance and politeness, asserts that people wish to determine their preferences and actions and to be unimpeded in the process of making these choices (Brehm & Brehm, Citation1981; Brown & Levinson, Citation1987). In other words, they desire autonomy. Thus, when individuals perceive that their freedom to choose is constrained, they resist persuasion. Although any attempt to persuade can be considered a threat to freedom, message strategies vary in the degree to which they are likely to be seen as threatening (Jenkins & Dragojevic, Citation2013). Inexplicit speech invites people to elaborate on the message to discover the speaker’s wants. The act of filling in the gaps makes readers more willing to accept the message because they can draw their own conclusions (Blum-Kulka, Citation1987; O’Keefe, Citation1997). Accordingly, discerning the speaker’s wants on their own gives readers the pleasurable experience of being supported in their need for autonomy (Jenkins & Dragojevic, Citation2013).

And what are the implications for verbal anchoring? Explicit requests and verbal anchoring are related in that both concepts are concerned with the extent to which meanings are spelled out (van Enschot & Hoeken, Citation2015). While the concept of explicitness refers to the degree to which a message source renders transparent his or her intentions in the message, verbal anchoring describes various degrees to which a verbal text explains the meaning of an image (Blum-Kulka, Citation1987; Dillard, Citation2014). We should expect that any attempt to impose a specific reading on the readers, including explicit requests and verbal anchoring, would interfere with the need for autonomy and, in so doing, decrease persuasion. This effect is presumably driven by perceived interpretational guidance. The more readers feel guided in their interpretation, the less favourable they should be towards message advocacy because they make the unpleasant experience of not being allowed to derive their own interpretation. Accordingly, perceived interpretational guidance should have an inverse impact on persuasion.

Hypothesis 3: Perceived interpretational guidance negatively predicts persuasion.

Taken together, the need for sense-making and the need for autonomy yield conflicting implications for the impact of verbal anchoring. On the one hand, readers may appreciate the cognitive efficiency offered by higher levels of anchoring, and they may be more persuaded because of it. On the other hand, readers may dislike being told what to think and may, therefore, manifest resistance to persuasion. Depending on which need prevails, either complete or no verbal anchoring should be most persuasive. Implied in both perspectives is the assumption that interpretational guidance operates as the key mechanism explaining the relationship between verbal anchoring and persuasion. We therefore posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: Perceived interpretational guidance is the key explanatory mechanism accounting for the effects of verbal anchoring on persuasion.

Persuasion process

Persuasion is not a single event, but rather a ‘sequence of linked changes’ (Seo et al., Citation2013, p. 567). It is a process in which early judgments about the perceived effectiveness of a message shape later and more stable outcomes, including attitudes, intentions, and behaviours (Dillard & Seo, Citation2013; Rhodes & Ewoldsen, Citation2013). Perceived effectiveness refers to the overall judgement of the expected impact of a given message (Seo et al., Citation2013). It taps readers' perceptions of how persuasive, convincing, and effective they find the message. Previous research has consistently identified perceived effectiveness as a key determinant of attitude (Dillard et al., Citation2007; Seo et al., Citation2013). Attitude means a general assessment of the advocacy put forward by a persuasive message (Seo et al., Citation2013).

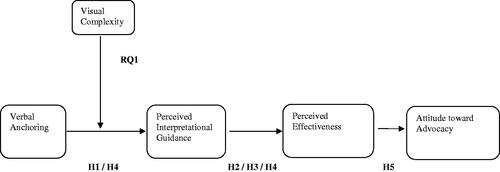

Given prior work, we conceive persuasion as a process of linked changes, with perceived effectiveness being a causal antecedent of attitude toward the advocacy (Hypothesis 5). summarizes the presumed persuasion process that follows from variations in verbal anchoring and visual complexity and illustrates the specific expectation that:

Hypothesis 5: Attitude toward the advocacy is a direct function of perceived effectiveness.

Method

Design

The study was a 3 (verbal anchoring: none vs. moderate vs. complete) × 4 (visual complexity: straightforward vs. juxtaposition vs. fusion vs. replacement) factorial design, where complexity and anchoring were both within-participants factors. Via control of the survey software, each participant viewed and rated one message in each of the visual complexity conditions. Within each complexity condition, participants were randomly assigned to one of the three verbal anchoring conditions. To enhance the generalizability of the findings, each of the 12 experimental conditions included three stimuli which were constructed from professionally produced advertisements. The step of assigning participants to messages involved a random draw from the three ads within each of the 12 experimental conditions.

Stimuli and pre-tests

To maintain topical consistency across messages, we selected only ads that dealt with environmental pollution. Twenty-three print advertisements that contained either a straightforward image, a juxtaposition figure, a fusion figure, or a replacement figure were collected from online databases (e.g. www.adsoftheworld.com and www.pinterest.com).

Each ad was produced in three levels of verbal anchoring. To create ads with no verbal anchoring, we removed all the text except for the brand logo. Then we added text to create completely anchored and moderately anchored versions. In most cases, the original text was utilized for the high anchoring version. Variation in anchoring was accomplished via the following rules: The complete anchoring version included information about a problem (human-generated waste) and its negative impact (does what?) on the environment (to whom?). An example is a headline stating ‘Plastic waste replaces marine animals’. The moderate anchoring version mentioned only negative impact and the environment (e.g. ‘replaces marine animals’). Thus, readers had to infer from the image that human waste was the problem.

Two separate pre-tests were conducted. The first assessed perceived levels of verbal anchoring. Twenty-five participants, drawn from a Qualtrics online panel, were shown two versions of each of the 23 ads, one with moderate and the other with complete verbal anchoring, Following each ad, they rendered a judgement on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 =strongly agree) as to the extent to which the ad explained the meaning of the image. A series of paired samples t-tests showed that the complete verbal anchoring headlines in all 23 advertisements were perceived as providing more explanation than the moderate verbal anchoring headlines: mean values differed at p < .05 for all comparisons but one, which was p = .054. We concluded that our manipulation of verbal anchoring was successful.

The second pre-test assessed visual complexity. All 23 ads were submitted to four judges with academic training in communication science or rhetoric. The pre-test started with a brief explanation of the differences between straightforward images and visual rhetorical figures and introduced the visual complexity typology developed by Phillips and McQuarrie (Citation2004). The judges were then shown the ads in randomized order and asked to indicate whether or not the image contained a rhetorical figure. If participants thought a rhetorical figure was present in the image, they were asked to classify it as juxtaposition, fusion, or replacement. Within each visual complexity category, we retained three ads for the main study. This was done to reduce the risk that the study results would be biased by the idiosyncratic features of individual ads. For each visual complexity category, we chose those three ads that were most often classified correctly (i.e. in agreement with our collective judgement). This meant ads with the highest pairwise percent agreement among all judges, whereby their classification had to be congruent with ours. The analysis showed an average pairwise agreement of 88%, a Fleiss’ κ of 0.84, and a Krippendorff’s α (nominal) of 0.84 for the selected ads.

Overall, 12 ads were retained for the main study: three ads with straightforward images, three with juxtaposition figures, three with fusion figures, and three with replacement figures. Each of the 12 ads varied verbal anchoring (none vs. moderate vs. complete), which gave a total of 36 stimuli.

Participants

Members of the Qualtrics panel were invited into the study if they were residents of the U.S and 18 or older. Participants are recruited into the panel through a variety of means (e.g. newspaper advertising) and receive various forms and levels of compensation appropriate to their location.

Screening questions ensured that the sample was balanced on gender, age, and education. The initial sample included 340 participants of which 36 were excluded because of straight-lining (final N = 304). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 91 years (M = 46.0, SD = 17.7), 148 (49%) were female, 156 (51%) were male. In terms of ethnicity, 239 identified as white (79%), 29 as African descent (10%), 19 as Asian descent (6%), 18 as Hispanic (6%), and six as American Indian or Alaska Native (2%). The total value exceeds 100% because participants were allowed to check multiple categories. With regard to education, 11 indicated not having completed high school (4%), 94 indicated having a high school diploma (31%), 32 an associate’s degree (11%), 97 a bachelor’s degree (32%), and 70 a higher degree (23%).

Procedure

The experiment was conducted online in May 2020. Participants were first informed about the study conditions and asked to give their consent to participate in the experiment. They were subsequently directed to an experimental survey that consisted of two parts: (a) social category information (age, gender, ethnicity, education) and (b) four ads (i.e. experimental treatments) each of which was followed by questions about their reactions to the ad (interpretational guidance, perceived effectiveness, and attitude toward the advocacy).

Measures

Perceived interpretational guidance

Perceived interpretational guidance (M = 4.0, SD = 1.81) was measured with three 7-point scale items ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree): ‘The ad tried to constrain my interpretation’, ‘The ad pushed me towards a particular interpretation’, ‘The ad tried to tell me what to think’ (α = .85).

Perceived effectiveness

Three 7-point semantic differentials measured perceived effectiveness (M = 5.3, SD = 1.78). Participants were asked to report how persuasive (not at all persuasive–very persuasive), how convincing (not at all convincing–very convincing) and how effective (not at all effective–very effective) they perceived the ad (Seo et al., Citation2013). The items showed good internal consistency (α = .95).

Attitude toward the advocacy

Attitude toward the advocacy (M = 6.0, SD = 1.63) was measured by three items on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The items were ‘I support what the message was trying to accomplish’, ‘I agree with the position advocated in the message’, and ‘I am favourable towards the main point of the message’ (α = .93). The items were adopted from Seo et al. (Citation2013).

Controls

Three sociodemographic variables were included as control variables: gender (M = 1.5, SD = 0.50),Footnote1 age (M = 46.0, SD = 1.81), and education (M = 3.4, SD = 1.24).

Measurement analysis

To evaluate the structure of the theoretical measures (guidance, effectiveness, and attitude), we performed an exploratory factor analysis using principle axis factoring withpromax rotation. The analysis supported a three-factor solution in which all of the items showed high loadings on their intended factor (.71–.95) and low cross-loadings (−.14–.11). Each of the factors produced eigenvalues >1.

Theoretical analyses

Our data were structured into two levels. Level 1 captured the within-participant variation (i.e. the verbal anchoring, visual complexity manipulation, and the self-reported persuasion data). Level 2 captured the between-participant variation (i.e. sociodemographic data). Multilevel modelling was conducted via SPSS using restricted maximum-likelihood estimation and treating intercepts as random effects. We first computed the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for the unconditional models to check whether there was sufficient variation in the dependent variables at level 1. We observed significant variation at level 1 for perceived interpretational guidance (68%, p < .001), perceived effectiveness (55%, p < .001), and attitude toward the advocacy (78%, p < .001).

We then performed a series of multilevel analyses that followed the process depicted in . Accordingly, we began with the simplest model first, in which interpretational guidance was the dependent variable. The next model cast perceived effectiveness as the outcome and the third treated attitude as the dependent variable. To assess the predicted process, all predictors and outcome variables, once included in the analysis, were kept and used as predictors in all subsequent analyses. Predictors were entered as covariates.

For the interpretational guidance model, we included gender, age, and education (level 2) as well as verbal anchoring, visual complexity, and an interaction term (level 1) as predictors. To facilitate interpretation and reduce multicollinearity, we assigned orthogonal codes to verbal anchoring and visual complexity, then calculated the interaction term as their product. The second model deployed perceived effectiveness as the dependent variable. We used the same predictors and added perceived interpretational guidance as another level-1-predictor. The third analysis used attitude as the dependent variable. We included all predictors from the previous analyses in the model and added perceived effectiveness as another level-1-predictor. When the level-1 and level-2 predictors showed non-significant effects, we tested a reduced model without these variables. Results are reported only for the reduced models.

Results

The results are presented in three sections with each section being organized around one of the outcome variables in the model (i.e. perceived interpretational guidance, perceived effectiveness, attitude toward the advocacy). Within each, we briefly present the results for the full model and subsequently detail the results for the reduced model.

Effects on perceived interpretational guidance: H1, RQ1

For the full model, the level-1 predictor verbal anchoring, as well as the level-2-predictors gender, age, and education, had a significant impact on perceived interpretational guidance. Neither visual complexity nor the interaction between anchoring and complexity yielded a significant effect. Thus, both were removed from the model. Results for the reduced model appear in . As shown, verbal anchoring was significantly related to perceived interpretational guidance (b = .09, p = .022) such that higher levels of anchoring corresponded with higher levels of guidance.

Table 1. Multilevel modelling results arranged in columns by research questions and hypotheses (predictors entered as covariates).

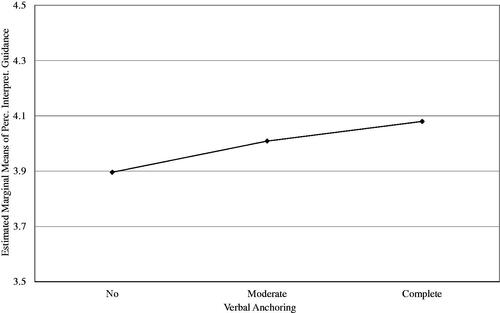

To gain a more nuanced understanding of this effect, we conducted a follow-up analysis using verbal anchoring as a factor in the model (instead of a covariate). presents the estimated marginal means for each level of anchoring. Pairwise comparisons of the estimated marginal means using Fisher’s least significant difference test (LSD) showed that complete verbal anchoring (M = 4.1, SE = .096) led to significantly higher perceptions of being guided relative to no verbal anchoring (M = 3.9, SE = .095, p = .022). The difference between complete anchoring and moderate anchoring (M = 4.0, SE = .096, p = .388), as well as the difference between moderate and no anchoring (p = .168), were non-significant.

The first hypothesis predicted a positive relationship between verbal anchoring and perceived interpretational guidance. H1 was supported. The study also took into consideration that the complexity of an ad’s image might influence whether readers perceive verbal anchoring as more or less constraining. RQ1 inquired about an interaction between verbal anchoring and visual complexity on perceived interpretational guidance. However, the interaction proved non-significant, suggesting that the effect of verbal anchoring on perceived interpretational guidance was unaffected by the complexity of an ad’s image.

Effects on perceived effectiveness: H2, H3, H4

For the full model, verbal anchoring and perceived interpretational guidance, as well as age predicted perceived effectiveness. Visual complexity, the interaction term, gender, and education showed non-significant relationships with perceived effectiveness. These variables were removed. Age was subsequently removed when its effect became unequivocally non-significant in the reduced model. The final reduced model included only verbal anchoring and perceived interpretational guidance ().

Hypothesis 2 and 3 predicted contrary effects of perceived interpretational guidance on perceived effectiveness. Whereas H2 assumed a positive relationship, H3 anticipated a negative relationship. The results showed that perceived interpretational guidance was positively associated with perceived effectiveness (b = .07, p = .033). Hence, H2 was supported while H3 was not.

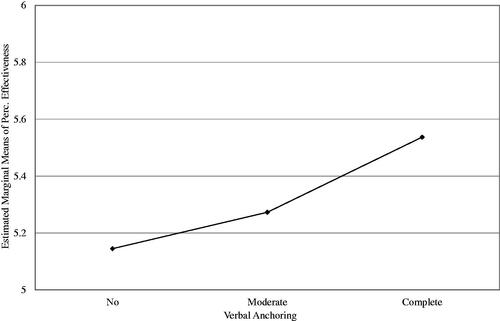

Hypothesis 4 anticipated that perceived interpretational guidance would be the key mechanism explaining the effects of verbal anchoring on persuasion. Besides a significant relationship between anchoring and guidance, this prediction required two further conditions to be met: (1) a significant positive relationship between perceived interpretational guidance and perceived effectiveness and (2) the absence of a significant relationship between verbal anchoring and perceived effectiveness. In line with our expectations, interpretational guidance had a significant positive effect on perceived effectiveness. However, verbal anchoring (b = .20, p = .000) also had a significant positive impact on perceived effectiveness, suggesting that greater amounts of verbal anchoring lead to greater perceptions of message effectiveness. Pairwise comparisons () indicated that ads with complete verbal anchoring (M = 5.5, SE = .098) were perceived to be significantly more effective than ads with moderate verbal anchoring (M = 5.3, SE = .099, p = .01) and no verbal anchoring (M = 5.1, SE = .098, p = .000). The difference between moderate and no verbal anchoring proved non-significant (p = .211). Overall, the results imply that perceived interpretational guidance partially mediates the relationship between verbal anchoring and perceived effectiveness. Accordingly, we only find partial support for H4.

Effects on attitude towards the advocacy: H5

For the full model, interpretational guidance, perceived effectiveness, gender, age, and education had a significant impact on attitude toward the advocacy. No significant relationship was found for the level-1-predictors verbal anchoring, visual complexity, or the interaction term. These predictors were therefore removed. Although significant in the full model, interpretational guidance was also removed from the reduced model because its effect did not meet the traditional p < .05 criterion (). The analysis in the reduced model produced b = .06, p = .001 for the relationship between perceived effectiveness and attitude toward the advocacy, indicating that the more effective participants considered an ad to be, the more favourable they were towards the message advocacy.

H5 predicted that attitude toward the advocacy would be a direct function of perceived effectiveness. This required two conditions to be met: (1) a significant positive relationship between perceived effectiveness and attitude toward the ad and (2) the absence of significant relationships between other level-1-predictors (i.e. verbal anchoring, visual complexity, interaction term, perceived interpretational guidance) and attitude toward the ad. Perceived effectiveness was positively related to attitude toward the advocacy. Moreover, none of the other level-1-predictors exhibited a significant effect. H5 was thus supported.

Discussion

Predicated on the assumption that visually literacy requires understanding text-image relationships, we conducted an experiment that manipulated verbal anchoring and visual complexity. Next, we examine the findings pertinent to each step of the proposed theoretical process.

Persuasive mechanism of verbal anchoring

Verbal anchoring is the idea that the intention of image-based advertisements may be explained, to varying degrees, by accompanying text. Previous studies have consistently shown that verbal anchoring increases perceived comprehension and help readers discern the intended interpretation (Bergkvist et al., Citation2012; Lagerwerf et al., Citation2012; Phillips, Citation2000; van Enschot & Hoeken, Citation2015). These investigations did not, however, address the mechanism by which verbal anchoring achieves that end. Our project sought to fill this gap.

We anticipated that higher levels of verbal anchoring would be perceived as providing more interpretational guidance, that is, as an effort to steer readers towards one interpretation of the message and away from others (Lagerwerf et al., Citation2012). The data showed precisely this effect. The association between three levels of verbal anchoring and perceived guidance was statistically significant and roughly linear. This establishes a clear empirical connection between the message feature – anchoring – and the expected psychological state – perceived guidance. The result suggests that comprehension follows from the guidance offered by verbal anchoring.

We were also interested in the effect of interpretational guidance on downstream persuasion variables. Here the study was governed by two competing assumptions. One held that readers possess an innate need to make sense of the world and, therefore, appreciate assistance in drawing a preferred interpretation. The other assumption supposed that readers value autonomy and, thus, dislike being told what to think. The data revealed a positive relationship between interpretational guidance and perceived message effectiveness, suggesting that the need for sense-making was prepotent in our data. Under the conditions of our experiment, message readers prioritized cognitive efficiency over autonomy.

Despite this result, we caution against the conclusion that the desire for autonomy is unimportant to persuasion theory. Indeed, decades of research suggest otherwise (Brehm & Brehm, Citation1981). It seems more plausible that our findings, while veridical, are limited to certain conditions, such as low personal relevance. Despite its serious impact on the environment and sea life, plastic pollution does not have an immediate or direct impact on most people’s life. In such circumstances, message readers may prioritize a quick and easy way to formulate their attitude (Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1981).

We also observed a statistically significant and unexpected direct effect of anchoring on perceived effectiveness: Higher levels of anchoring produced higher levels of perceived effectiveness. This result indicates that perceived interpretational guidance is a key explanatory mechanism, but not the sole explanatory mechanism (because there is an effect for anchoring even after controlling for guidance). An explanation for this may lie in our conception of the guidance function of anchoring as a cognitive mechanism. In retrospect, it is apparent that a purely cognitive perspective overlooks the potential for affective influences on persuasion that may co-occur (Seo & Dillard, Citation2019). Future research might consider theorizing and measuring both types of processes.

Overall, the data make a compelling case for why visual literacy requires message consumers to consider the relationship between imagery and text. Our study demonstrates that – even in visually dominant advertisements – text plays a crucial role in persuasion. Pairing visual imagery with complete verbal anchoring increases persuasion, and this occurs because readers appreciate the enhanced informational value offered by the explanatory headline.

Effects of visual complexity

Visual complexity is a message property that distinguishes literal visual messages from three conceptually distinct visual rhetorical forms: juxtaposition, fusion, and replacement. These forms are arrayed on a continuum that varies in terms of the degree of cognitive effort that is needed to grasp the intended meaning of a message (Phillips & McQuarrie, Citation2004). We examined the possibility that visual complexity might influence perceptions of being guided towards certain interpretations, either alone or in combination with verbal anchoring. Because the data showed no such effect on perceived interpretational guidance, we must ask why.

One possibility is that our operationalization of complexity was flawed. However, our assessment of the images, as well as those of our pre-test judges leads us to give this possibility little weight. However, the ultimate arbiter of this point is the scientific community. Readers can inspect the images themselves to judge the degree to which our operations/images correspond with the concept of visual complexity as articulated in the literature (Phillips & McQuarrie, Citation2004).

Alternatively, we cannot rule out the possibility that the results reflect reality. Perhaps the notion of visual complexity captures the attention of academics, but has no impact on members of a lay audience? Evidence showing that visual complexity influences persuasion, however, suggests otherwise (Lagerwerf et al., Citation2012; van Mulken et al., Citation2010, Shen & Han, Citation2014).

A more plausible explanation for why visual complexity did not yield an effect on perceived interpretational guidance may have to do with the semiotic potential of the visual mode. The visual arranges information holistically and simultaneously. Since there are multiple ways of relating information to each other and since the visual mode lacks a distinct syntax, images guide meaning making to a lesser extent than verbal texts (Meyer et al., Citation2013). This polysemy inherent in images may be the reason why images – even when they are straightforward and easy to understand – are not perceived as offering interpretational guidance. These findings are theoretically valuable insofar as they support the idea that, even in a visual society, some communicative functions are more effectively performed by the verbal mode.

Persuasion process

In line with previous research (Seo et al., Citation2013), we conceptualized persuasion as a sequence of linked changes, with perceived effectiveness serving as a causal antecedent of attitude toward the advocacy. The data showed the anticipated pattern. This result is compatible with the idea of a ‘hierarchy of effects’ in message processing (Slater, Citation2002, p. 166). Because perceived effectiveness precedes attitude toward the advocacy, it is relatively more sensitive to variations in message features (Shen & Han, Citation2014). This result is not novel. But, because it replicates a well-known effect, it implies the veracity of other findings from our data.

Practical implications

With advertising becoming increasingly visual, the question poses itself, how much verbal copy is most persuasive? Our study suggests that practitioners should use complete verbal anchoring to achieve the maximal persuasive effect.

Although prior research has found that rhetorical figures enhance persuasion compared to non-figurative ads (Huhmann & Albinsson, Citation2019), our data did not show this effect. One difference is that previous work has focussed almost exclusively on commercial advertising, whereas our study examined social issue campaigns. This disparity can be seen as a cautionary note to practitioners: Best practices in commercial advertising may not transfer seamlessly to social advertising.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The most obvious is our focus on the single social problem, that is, environmental pollution. Although the use of multiple messages within this broad category should increase confidence in our findings, it simultaneously reduces our ability to generalize beyond that topic. Our sample, which consisted solely of U.S. residents presents another limitation. A third limitation concerns the stimuli. We used professionally produced advertisements and manipulated only the amount of verbal anchoring presented in each one. However, the fact that the ads came from known sources, including the World Wildlife Fund and Greenpeace, might have influenced responses. Brand familiarity is known to affect responses to persuasive messages (Mikhailitchenko et al., Citation2009).

Conclusion

The present study offers a compelling case for why visual literacy requires message readers to consider the relationship between image and text. The findings show that higher levels of anchoring text decisively influence persuasion. In the context of prosocial advertising, complete anchoring should be preferred over moderate or no anchoring because people value the cognitive efficiency associated with being guided in their interpretation of the ad’s meaning.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 1 = male, 2 = female.

References

- AdForum (2017). Ocean Care: Sea horse – Toothbrush. https://www.adforum.com/creative-work/ad/player/34550285/sea-horse-toothbrush/oceancare

- Ads of the World (2007). Child Health Foundation: Smoke ring. https://www.adsoftheworld.com/media/print/smoke_ring

- Ads of the World (2009). WWF: Lungs. https://www.adsoftheworld.com/media/print/wwf_lungs

- Ads of the World (2010). Amnesty International: Street beating campaign. https://www.adsoftheworld.com/media/print/amnesty_international_street_beating

- Ads of the World (2011). WWF: Panda campaign. https://www.adsoftheworld.com/media/print/wwf_panda_3

- Atkin, C. K., & Rice, R. E. (2013). Theory and principles of public communication campaigns. In R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkin (Eds.), Public communication campaigns (4th ed., pp. 3–19). Sage.

- Avgerinou, M. D. (2001). Towards a visual literacy index. In R. E. Griffin, V. S. Williams, & L. Jung (Eds.), Exploring the visual future: Art design, science & technology (pp. 17–26). IVLA.

- Avgerinou, M. D. (2009). Re-viewing visual literacy in the “bain d'images” era. Tech Trends, 53(2), 28–34.

- Barthes, R. (1977). Image music text. Hill and Wang.

- Bergkvist, L., Eiderbäck, D., & Palombo, M. (2012). The brand communication effects of using a headline to prompt the key benefit in ADS with pictorial metaphors. Journal of Advertising, 41(2), 67–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367410205

- Blum-Kulka, S. (1987). Indirectness and politeness in requests: Same or different? Journal of Pragmatics, 11(2), 131–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-2166(87)90192-5

- Brehm, S. S., & Brehm, J. W. (1981). Psychological reactance: A theory of freedom and control. Academic Press.

- Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Studies in interactional sociolinguistics, 4. Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press.

- Chater, N., & Loewenstein, G. (2016). The under-appreciated drive for sense-making. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 126, 137–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.10.016

- Dillard, J. P. (2014). Language, style, and persuasion. In T. M. Holtgraves (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of language and social psychology (pp. 177–187). Oxford University Press.

- Dillard, J. P., & Seo, K. (2013). Affect and persuasion. In J. P. Dillard & L. Shen (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of persuasion: Developments in theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 150–166). Sage.

- Dillard, J. P., Weber, K. M., & Vail, R. G. (2007). The relationship between the perceived and actual effectiveness of persuasive messages: A meta-analysis with implications for formative campaign research. Journal of Communication, 57(4), 613–631. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00360.x

- Forceville, C. (2014). Relevance Theory as model for analysing visual and multimodal communication. In David Machin (Ed.), Visual communication (pp. 51–70). de Gruyter Mouton.

- Geise, S., & Baden, C. (2015). Putting the image back into the frame: Modeling the linkage between visual communication and frame-processing theory. Communication Theory, 25(1), 46–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12048

- Gkiouzepas, L., & Hogg, M. K. (2011). Articulating a new framework for visual metaphors in advertising: A structural, conceptual, and pragmatic investigation. Journal of Advertising, 40(1), 103–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367400107

- Huhmann, B. A. (2018). Rhetorical figures. The case of advertising. In Ø. Ihlen & R. L. Heath (Eds.), The handbook of organizational rhetoric and communication (pp. 229–244). John Wiley & Sons.

- Huhmann, B. A., & Albinsson, P. A. (2019). Assessing the usefulness of taxonomies of visual rhetorical figures. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 40(2), 171–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2018.1503106

- Jenkins, M., & Dragojevic, M. (2013). Explaining the process of resistance to persuasion: A politeness theory-based approach. Communication Research, 40(4), 559–590. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650211420136

- Jeong, S. H. (2008). Visual metaphor in advertising: Is the persuasive effect attributable to visual argumentation or metaphorical rhetoric? Journal of Marketing Communications, 14(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010701717488

- Kjeldsen, J. E. (2012). Pictorial argumentation in advertising: Visual tropes and figures as a way of creating visual argumentation. In F. H. van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Topical themes in argumentation theory: Twenty exploratory studies (pp. 239–255). Springer Science + Business Media.

- Lagerwerf, L., van Hooijdonk, C. M. J., & Korenberg, A. (2012). Processing visual rhetoric in advertisements: Interpretations determined by verbal anchoring and visual structure. Journal of Pragmatics, 44(13), 1836–1852. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2012.08.009

- Machin, D. (2014). Handbooks of communication science: 4. Visual communication. de Gruyter.

- McQuarrie, E. F., & Mick, D. G. (1996). Figures of rhetoric in advertising language. Journal of Consumer Research, 22(4), 424–438. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209459

- McQuarrie, E. F., & Phillips, B. J. (2008). It’s not your father’s magazine ad. Magnitude and direction of recent changes in advertising style. Journal of Advertising, 37(3), 95–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367370307

- Meyer, R. E., Höllerer, M. A., Jancsary, D., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2013). The visual dimension in organizing, organization, and organization research: Core ideas, current developments, and promising avenues. Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 489–555. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2013.781867

- Mikhailitchenko, A., Javalgi, R. G. J., Mikhailitchenko, G., & Laroche, M. (2009). Cross-cultural advertising communication: Visual imagery, brand familiarity, and brand recall. Journal of Business Research, 62(10), 931–938. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.11.019

- O’Keefe, D. J. (1997). Standpoint explicitness and persuasive effect: A meta-analytic review of the effects of varying conclusion articulation in persuasive messages. Argumentation and Advocacy, 34(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00028533.1997.11978023

- Petfinder (2014). Shelter Pet Project. https://pro.petfinder.com/blog/2014/05/follow-friday-shelter-pet-project/

- Pettersson, R. (2007). Visual literacy in message design. Journal of Visual Literacy, 27(1), 61–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2007.11674646

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1981). Attitudes and persuasion: Classic and contemporary approaches. Brown.

- Phillips, B. J. (2000). The impact of verbal anchoring on consumer response to image ads. Journal of Advertising, 29(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673600

- Phillips, B. J., & McQuarrie, E. F. (2004). Beyond visual metaphor: A new typology of visual rhetoric in advertising. Marketing Theory, 4(1–2), 113–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593104044089

- Pierson, J. (2013). A world without words. NZ Marketing Magazine, 59.

- Pollay, R. W. (1985). The subsiding sizzle: A descriptive history of print advertising, 1900–1980. Journal of Marketing, 49(3), 24–37.

- Pracejus, J. W., Olsen, G. D., & O’Guinn, T. C. (2006). How nothing became something: White space, rhetoric, history, and meaning. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(1), 82–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/504138

- Rhodes, N., & Ewoldsen, D. R. (2013). Outcomes of persuasion. In J. P. Dillard & L. Shen (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of persuasion: Developments in theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 53–69). Sage.

- Seo, K., & Dillard, J. P. (2019). A process analysis of message style and persuasion: The effects of gain-loss framing and emotion-inducing imagery. Visual Communication Quarterly, 26(3), 131–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15551393.2019.1638785

- Seo, K., Dillard, J. P., & Shen, F. (2013). The effects of message framing and visual image on persuasion. Communication Quarterly, 61(5), 564–583. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2013.822403

- Shen, F., & Han, J. (2014). Effectiveness of entertainment education in communicating health information: A systematic review. Asian Journal of Communication, 24(6), 605–616. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2014.927895

- Slater, M. D. (2002). Entertainment education and the persuasive impact of narratives. In J. J. Strange & T. C. Brock (Eds.), Narrative impact: Social and cognitive foundations (pp. 157–182). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1986). Relevance: Communication and cognition. Basil Blackwell.

- van Enschot, R., & Hoeken, H. (2015). The occurrence and effects of verbal and visual anchoring of tropes on the perceived comprehensibility and liking of TV commercials. Journal of Advertising, 44(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2014.933688

- van Mulken, M., Le Pair, R., & Forceville, C. (2010). The impact of perceived complexity, deviation and comprehension on the appreciation of visual metaphor in advertising across three European countries. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(12), 3418–3430. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.04.030

- van Mulken, M., van Enschot, R., & Hoeken, H. (2005). Levels of implicitness in magazine advertisements: An experimental study into the relationship between complexity and appreciation in magazine advertisements. Information Design Journal, 13(2), 155–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/idjdd.13.2.09mul

- van Mulken, M., van Hooft, A., & Nederstigt, U. (2014). Finding the tipping point: Visual metaphor and conceptual complexity in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 43(4), 333–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2014.920283

- Williams, W. R. (2019). Attending to the visual aspects of visual storytelling: using art and design concepts to interpret and compose narratives with images. Journal of Visual Literacy, 38(1–2), 66–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1051144X.2019.1569832