Abstract

Medicaid is expanding funding for tenancy support services (TSS) that help people who have experienced homelessness or lived in institutional settings obtain and maintain housing. To identify critical considerations for Medicaid TSS regulations, we compared two successful TSS provider agencies in North Carolina, and conducted additional stakeholder interviews in North Carolina and Louisiana, which is ahead of North Carolina in expanding Medicaid-funded TSS. Stakeholder concerns focused on the impact of regulation on goals of access, quality, and flexibility, and noted tensions among these goals. Specific regulatory approaches may mitigate the tension among these goals, such as outcome- and client feedback-based accountability, and an emphasis on job-specific training. Moreover, meeting the goals of access, quality, and flexibility and mitigating their trade-offs is supported by state infrastructure that includes braided funding; horizontal and vertical coordination across agencies; and the capacity for multimodal, multilevel quality assurance and multilevel training and technical assistance.

As Medicaid funding is applied to services addressing the social drivers of health, states are faced with the challenge of designing effective regulations to address nonmedical needs. Housing is now a focus of Medicaid transformation across the country, due to its importance to the well-being of all people and particularly those with physical and mental disabilities. Housing stability for people with disabilities is fostered by permanent supportive housing (PSH), which combines affordable housing with tenancy support services (TSS)—resident-centric services that include coaching, assistance, and skill-building for a range of behaviors associated with tenancy (e.g., negotiating relationships with landlords, budgeting, minor home maintenance, and daily activities such as cooking and cleaning). Although PSH has been associated with decreased homelessness, increased housing tenure, and positive health outcomes, public financial support for PSH has historically been limited, with funding primarily provided by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In 2015, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued an informational bulletin advising that Medicaid funds could be used to reimburse specifically for TSS, creating a significant expansion in the funding available for a key component of PSH.

To effectively utilize Medicaid funds, however, states need to better understand the regulatory and funding environments that support successful services. There are several mechanisms that can be used to fund TSS through Medicaid and a number of choices to make about what services are covered, service duration, service provider qualifications, etc. Currently, there is no standard definition of TSS to help with those decisions (NASEM, Citation2018). Moreover, Medicaid’s orientation toward funding fragmented clinical and institution-based services and its lack of flexibility are not well aligned with the varied and individualized needs of people who need housing support (Wilkins, Citation2015).

To help understand the regulatory and funding environment that can support effective TSS, this paper describes lessons learned from comparative case studies of two successful TSS providers in North Carolina (NC) and additional key participant interviews (KPIs) with stakeholders working at the state and regional levels in NC and Louisiana (LA).

Background

The Need for Community-Based Housing Solutions

There is an enormous need in the United States to help individuals who are institutionalized or experiencing homelessness obtain independent housing. In 1999, the United States Supreme Court held in Olmstead v. L.C. that unjustified segregation of persons with disabilities constitutes discrimination in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act. In its opinion, the majority cited the adverse impact of unnecessary institutionalization, stating that “confinement in an institution severely diminishes the everyday life activities of individuals, including family relations, social contacts, work options, economic independence, educational advancement, and cultural enrichment” (Olmstead v. L.C., 527 U.S. 581, Citation1999). Almost two decades later, there are thousands of people with physical, mental, and developmental disabilities living in institutionalized settings who could be residing in communities; according to the American Community Survey, from 2012 to 2016, 5.1% of individuals with disabilities were living in institutions (such as correction facilities, nursing homes or mental hospitals) and another 1.7% in other group settings (PARC, Citation2020).

In addition, the 2020 Point-in-Time (PIT) count estimate identified approximately 580,000 Americans experiencing homelessness (primarily sleeping outside or in emergency shelters, or residing in transitional housing) (Henry et al., Citation2021). Due to the difficulty of enumerating homeless persons, the problem is likely underestimated (Brush et al., Citation2016). Of those experiencing homelessness, more than one fourth were identified as chronically homeless individuals who would benefit from long-term affordable housing and support services (Henry et al., Citation2021).

The Importance of TSS

One of the most promising policy solutions to decrease institutionalization and homelessness for high-need populations is expanding access to PSH. PSH combines long-term affordable housing and the TSS that help people with securing and maintaining a home. There is no agreed-upon definition of TSS. Whereas some programs define TSS narrowly, others expect their staff to provide a broad array of services ranging from helping with a housing application to solving hygiene problems that might result in eviction to connecting a consumer with health services. Box 1 provides the list of individual-level services allowable by CMS, as designated in their 2015 bulletin.

Box 1 Individual-level tenancy support services as described in Wachino (Citation2015).

Individual housing transition services: Housing transition services provide direct support to individuals with disabilities, older adults needing long-term services and supports, and those experiencing chronic homelessness. These services are:

Conducting a tenant screening and housing assessment that identifies the participant’s preferences and barriers related to successful tenancy. The assessment may include collecting information on potential housing transition barriers, and identification of housing retention barriers.

Developing an individualized housing support plan based upon the housing assessment that addresses identified barriers, includes short- and long-term measurable goals for each issue, establishes the participant’s approach to meeting the goal, and identifies when other providers or services, both reimbursed and not reimbursed by Medicaid, may be required to meet the goal.

Assisting with the housing application process. Assisting with the housing search process.

Identifying resources to cover expenses such as security deposit, moving costs, furnishings, adaptive aids, environmental modifications, moving costs, and other one-time expenses.

Ensuring that the living environment is safe and ready for move-in.

Assisting in arranging for and supporting the details of the move.

Developing a housing support crisis plan that includes prevention and early intervention services when housing is jeopardized.

Individual housing and tenancy sustaining services: This service is made available to support individuals to maintain tenancy once housing is secured. The availability of ongoing housing-related services in addition to other long-term services and supports promotes housing success, fosters community integration and inclusion, and develops natural support networks. These tenancy support services are:

Providing early identification and intervention for behaviors that may jeopardize housing, such as late rental payment and other lease violations.

Education and training on the role, rights, and responsibilities of the tenant and landlord.

Coaching on developing and maintaining key relationships with landlords/property managers with the goal of fostering successful tenancy.

Assistance in resolving disputes with landlords and/or neighbors to reduce risk of eviction or other adverse action.

Advocacy and linkage with community resources to prevent eviction when housing is, or may potentially become, jeopardized.

Assistance with the housing recertification process.

Coordinating with the tenant to review, update and modify their housing support and crisis plan on a regular basis to reflect current needs and address existing or recurring housing retention barriers.

Continuing training in being a good tenant and lease compliance, including ongoing support with activities related to household management.

Despite this heterogeneity, research shows that PSH is associated with decreased homelessness and increased housing tenure (Bassuk & Geller, Citation2006; Benston, Citation2015; Burt, Citation2012; Byrne et al., Citation2014; Henwood et al., Citation2015; Rog et al., Citation2014). Homelessness is a known risk factor for poor health (Dennis et al., Citation1991) and the research literature also indicates an association between PSH and multiple positive health outcomes, including decreased alcohol use, improved HIV status, decreased use of acute health services (ambulance, emergency department, and hospital), and increased use of outpatient services (Buchanan et al., Citation2009; Cantor et al., Citation2020; Collins et al., Citation2012; Mackelprang et al., Citation2014; Martinez & Burt, Citation2006; Paradise & Cohen Ross, Citation2017; Rieke et al., Citation2015; Rog et al., Citation2014; Wilkins, Citation2015). Reductions are found as well in overall service use, including public shelters, public hospitals, Medicaid-funded services, veterans’ inpatient services, psychiatric inpatient services, prisons and jails (Culhane et al., Citation2002a, 2002b).

A recent report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) states that, outside of the benefits of PSH for the health of individuals with HIV, the evidentiary base for demonstrating a causal relationship between PSH and health outcomes is limited by inconsistencies in the definition of PSH, a lack of consensus on minimum standards for services, and poor data systems (NASEM, Citation2018). However, the authors note the following:

While this [the lack of a strong evidence base] is the inescapable finding based on an impartial review of the evidence available at the time of this assessment, the committee believes that housing in general improves health, and notes that PSH is important in increasing the ability of some individuals to become and remain housed. Remaining housed should improve the health of these individuals because housing alleviates a number of negative conditions…. Sustained housing provides a platform from which other physical, mental, and social concerns can begin to be addressed. (p. 4)

The Importance and Challenge of Medicaid Funding for TSS

Public financial support for PSH has historically been limited, with funding coming primarily through HUD. There has been some limited Medicaid funding for TSS through inclusion in specific service models and auxiliary services. However, on June 26, 2015, CMS—in recognition of the potential benefits of PSH for health outcomes—issued the informational bulletin advising that Medicaid funds could be used by states to reimburse specifically for TSS (Wachino, Citation2015). This constitutes a significant expansion in eligibility for Medicaid-funded TSS; the opportunity to pair more Medicaid-funded TSS with affordable housing sets the stage for the possibility of a significant increase in access to PSH (contingent, of course, on the availability of housing).

Whereas new Medicaid funding expands potential access to TSS, the impact of that access depends on the requirements associated with those funds. The CMS bulletin reviews mechanisms and gives examples of how states can use Medicaid to fund TSS but leaves regulation development up to each state’s Medicaid program. States have a variety of decisions to make. They may fund TSS through a number of Medicaid vehicles, including rehabilitative services, targeted case management, several home and community-based services options, Section 1115 waiver programs (a mechanism for testing new Medicaid payment models), contracts with managed care organizations, Health Care for the Homeless programs, and “health homes” that provide comprehensive services for Medicaid enrollees with chronic conditions. Moreover, whichever mechanism or mechanisms are used, states need to develop service definitions that delineate what services can be covered for whom, how, how long, and with what oversight. This task is complicated by the fact that, as noted in the 2018 NASEM report, there is a lack of consensus even as to minimum standards for TSS. The challenges of the decisions facing policymakers are compounded by political and economic realities constraining the options that are feasible in any given state.

Employing Medicaid as a funding source for nonmedical services like TSS poses a particular dilemma. Whereas Medicaid has undergone some changes as a result of funding community-based long-term care services, it is grounded in a model of time-delimited, single-goal medical care. Commenting on the challenges of using Medicaid to fund housing supports in particular, Carol Wilkins notes:

It has often been an uphill battle to align the services in supportive housing with the definitions of Medicaid-covered benefits that were often not designed to cover services delivered outside the walls of clinics, offices, and treatment facilities. Fragmented service definitions and inflexible program rules can be a poor fit for the flexible and individualized services and supports needed by homeless people with multiple co-occurring chronic health conditions, mental health, and substance use disorders. (Wilkins, Citation2015, p. 69)

A body of literature is developing to address the need for thoughtful consideration of how Medicaid TSS funding can be designed for success. This literature has highlighted the challenges of client uptake and recruitment and retention of staff (Burt et al., Citation2014; Thompson et al., Citation2021); the strengths of the different Medicaid vehicles for funding TSS (Burt et al., Citation2014; CSH, Citation2021); the difficulties for housing agencies of meeting Medicaid requirements or of contracting with other agencies that can (Thompson et al., Citation2021); a need for Medicaid to expand the services it covers and/or a need for flexible sources of funding to pay for the services and individuals not covered by Medicaid (Wilkins, Citation2015); and the need for more training to transform current Medicaid providers into TSS providers and transform current TSS providers into Medicaid providers (Burt et al., Citation2014; CSH, Citation2021). Research has also indicated the value of better linking homeless and healthcare service providers with the state agencies overseeing these sectors (Burt et al., Citation2014; Paradise & Cohen Ross, Citation2017; Thompson et al., Citation2021; Wilkins, Citation2015) and coordinating different funding sources for TSS (Clary & Kartika, Citation2017; Paradise & Cohen Ross, Citation2017). This literature also notes some concerns specific to the 1115 waiver, including its time-limited nature and administrative burden (Thompson et al., Citation2021).

Purpose of Our Study and This Paper

The impetus for the study described here came from changes that were on the horizon for NC in 2017–2018, when the study was conducted. At the time of the study, TSS in NC was funded through a combination of philanthropy and public programs, with monies from HUD comprising the largest source of public funding. Public sources also included a small amount of Medicaid funding for specific populations (e.g., the “transition coordination” services that help low-income elderly and adults with physical disabilities obtain housing in the community) or for TSS as one component of specific service definitions—most notably, in the Assertive Community Treatment Teams (ACTT) service model, which provides multidisciplinary community-based services to people with severe and persistent mental illness. In 2012, the Department of Justice had determined that NC was in violation of the Olmstead decision and NC had created the state-funded Transitions to Community Living Initiative, which provides TSS to persons moving from institutional settings. A small amount of funding from other sources made up the remainder of public financing.

In response to CMS’ 2015 bulletin, NC policymakers began planning to incorporate TSS into the Community Support Team service model (which serves individuals with a lower acuity level than does ACTT), submitted a 1115 waiver proposal to CMS that included new vehicles for TSS funding, and began considering other potential mechanisms for Medicaid funding of TSS. The 1115 waiver was approved in October of 2018. Together these changes meant a dramatic increase to come in the number of people eligible for Medicaid-funded TSS in NC.

The goal of our study was to inform decisions being made around the definition of TSS service in NC and to contribute to the emerging literature on Medicaid funding of TSS by illuminating the opportunities and challenges facing a state poised to significantly expand that support. Our specific aims included: (1) delineating outcomes to be expected from successful TSS, (2) identifying promising provider practices for reaching those outcomes, and (3) ascertaining characteristics of the funding and regulatory environment that would support those practices and promote desired outcomes. It is that last aim that is addressed in this paper. As will be seen, although our original focus was on identifying considerations for the design of a TSS service definition, our data also led us to think about the state infrastructure that can promote success in this endeavor.

Because TSS is not defined in a standardized way, we offer a few comments on its meaning within the context of our study. We take a broad view of TSS, as agency services designed to help individuals who have been homeless or living in institutional settings obtain and maintain community-based housing. This includes coaching, assistance, and skill-building for a range of behaviors associated with tenancy (e.g., negotiating relationships with landlords, budgeting, minor home maintenance, and daily activities such as cooking and cleaning). TSS may be stand-alone services or part of a service model.

In addition to being paired with affordable housing in the PSH model, TSS can be provided together with short-term financial assistance through Rapid Rehousing. Because direct assistance is time-limited for Rapid Rehousing, TSS in this model is also limited, with consumers referred to service providers outside of the TSS arena for any long-term needs. Receipt of Medicaid-funded TSS in NC requires that the adult beneficiary have a disability, making it most likely that these individuals will have complex needs and therefore will be served through PSH. Our study thus focuses specifically on TSS services provided in the context of PSH.

Methods

Overview

This study of critical considerations for the TSS regulatory/funding environment draws on comparative case studies of two agencies at the forefront of providing TSS in NC and KPIs with representatives from the NC state infrastructure responsible for funding, oversight, and administrative of these services. To further illuminate the opportunities and challenges facing NC, we treated LA—a state with a long history of Medicaid-funded TSS—as a comparison state, and conducted KPIs there with state officials and service providers. For our larger study, we also analyzed Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) data for NC to shed light on TSS outcomes. (The results of that data analysis are not relevant to this article and therefore are not presented here). Data collection took place from 2017 to 2018. This research was approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board.

Comparative Case Studies

The two NC agencies that were the focus of this study were purposively chosen on the basis of two criteria. First, they are highly regarded TSS providers, offering the opportunity to generate information about effective strategies for TSS provision. To use the taxonomy of case selection (Seawright & Gerring, Citation2008), these are “extreme” cases exemplifying a phenomenon we wanted to understand (i.e., high-performing TSS). They are also “diverse” cases in terms of sector and region. Each represents one of the two primary sectors involved in TSS—mental health services and homeless and housing services—which allowed us to learn about ways in which provision of TSS in those sectors is similar and different. They are also located in different environments in different parts of the state.

Key characteristics of these two agencies are summarized in . Homeward Bound is a nonprofit agency located in Western NC that connects homeless individuals with housing and provides case management, including TSS. From 2006 to 2021, the agency housed over 2,250 individuals in permanent housing, with a 92% retention rate (Homeward Bound, Citation2021). As one of the largest providers of services for people experiencing homelessness in Buncombe County, they are recognized as having made a significant contribution to reducing chronic homelessness in their community, by 73% between 2008 and 2014.Footnote1

Table 1. North Carolina service provider agencies for the comparative case study.

The University of North Carolina (UNC) Center for Excellence in Community Mental Health, located in the middle of the state, has led NC’s mental health system in making the connection between housing and recovery. The Center provides TSS through high-intensity services such as ACTT, which serve individuals with persistent, severe mental illness and/or substance abuse disorders who require intensive intervention. In addition to running their own programs, the UNC Center for Excellence has been chosen by the state to perform fidelity oversight of other providers of integrated services.

Primary data sources for the case studies of these two agencies included focus groups with case managersFootnote2 and clients, KPIs with agency leads/unique personnel and landlords/property managers, and existing written documentation describing the agencies and their programs.

Additional Qualitative Research

Further insight into our research questions from the NC context was provided through KPIs with NC state officials and housing specialists at NC Local Management Entities-Managed Care Organizations (which coordinate safety net mental health services in the state). We supplemented the NC data with insights from LA. LA was selected as a comparison state because it is one of the few states with an extensive history of funding TSS through Medicaid (see for a comparison of the NC and LA contexts). It has also been cited for its success in sustaining its program over many years despite changes in executive leadership and funding streams (Clary & Kartika, Citation2017). In addition, the Medicaid program in LA is structured similarly to NC’s program, which makes lessons learned particularly relevant. Interviewees in LA included three state officials and two directors of housing service provider agencies. The LA agencies were selected based on recommendations from LA Department of Health and LA Housing Corporation leadership and were considered some of the highest performing TSS providers in the state.

Table 2. State contexts.

Data Collection

In total, 89 persons participated in the qualitative component of the study through interviews and focus groups (see for further detail on interview and focus group respondents). Careful consideration was given to participant selection and data collection modality (single interview, group interview, or focus group). In addition to expanding the number of individuals we could speak with, group interviews and focus groups allowed for the rich discussion generated by bringing together different individuals with a shared experience; group interviews specifically were conducted when the type of respondent (e.g., a particular staff position) did not allow for the volume of respondents needed for a focus group. Individual interviews provided participants with unique circumstances the space to fully describe their experiences and perspectives and the opportunity to share sensitive information (see Lambert & Loiselle, Citation2008 for discussion of the benefits of interviews and focus groups and their combined use). Where travel proved a barrier to participation, secure web meeting platforms were used for interviews and focus groups. Informed consent was secured prior to any data collection. Two research team members attended all data collection events: one acting as the primary interviewer and the other taking notes and recording observations of participant mannerisms. A single exception to this process occurred when two landlords arrived for an interview at the same time, so each was interviewed by only one team member. All interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim ().

Table 3. Interview and focus group respondents (n = 89).

Data Analysis

The research team developed a priori codes based on our research questions and interview guides. Code book changes were made and comprehensive code definitions formulated during coding of the initial transcripts, with the research team discussing and coming to consensus on all decisions. All data were double-coded (i.e., coded independently by two members of the study team) and differences reconciled through discussion.

A standard operating procedure guided analysis within each code. Data reports were generated for codes and co-occurring codes by participant type. Data within each code were analyzed by one member of the study team for each participant type; the same member of the study team then created four analytic summaries of the code: one for each of our NC case studies, one for NC overall, and one for LA overall. Analytic summaries were presented to the rest of the team for review, discussion, and revision if needed.

Written case studies of the two agencies were developed using the analytic summaries of case study data and existing written documentation describing the agencies and their programs. These case studies were compared to draw conclusions about promising practices for TSS and to identify key considerations for the design of Medicaid funding and oversight. The final analysis utilized the comparative case studies and state-level analytic summaries, with a return to more granular qualitative data to provide deeper insight as needed.

Community Engagement

A multipronged community engaged approach was used for this study (see CTSA, Citation2011 for more information on the benefits and practice of community engagement.). Emily Carmody from the NC Coalition to End Homelessness served as a coprincipal investigator on the study together with two university-based researchers, Donna Biederman and Mina Silberberg. The three co-PIs collaborated equally on all phases of the study, contributing their perspectives and expertise to decision-making and implementation throughout. In fact, the study topic came originally from the community co-PI. Officials from the NC Department of Health and Human Services were key stakeholders in the research, meeting with the research team on a quarterly basis to help us refine study questions, identify our study sample, design instruments, and develop dissemination approaches. Our study also involved a consumer advisory council comprising PSH clients that met four times and provided significant insight into the study sample, instrument design, and interpretation of findings. The case study agencies were also given the opportunity to refine research questions, helped us define and recruit our sample, and provided feedback on our written case studies. More detail on our community engagement approach and its contributions to the study is provided in Silberberg et al. (Citation2019).

Results

Overview

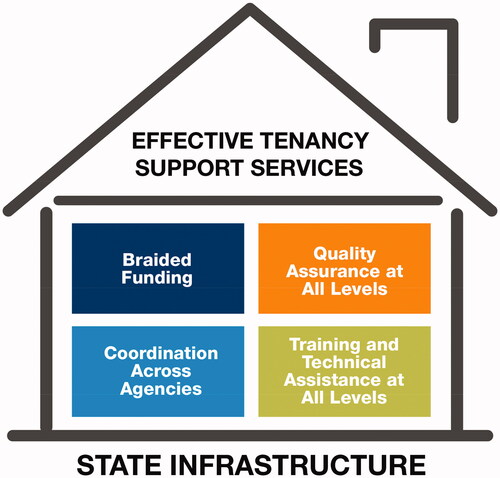

Data analysis through the iterative process described above generated themes in two domains relative to creating a regulatory and funding environment that promotes effective TSS: (1) the need for service definitions to promote, and balance tensions among, goals of access, quality, and flexibility; and (2) and the need for a supportive government infrastructure combining braided funding, interagency coordination, quality assurance at all levels of service provision and oversight, and training at all these levels.

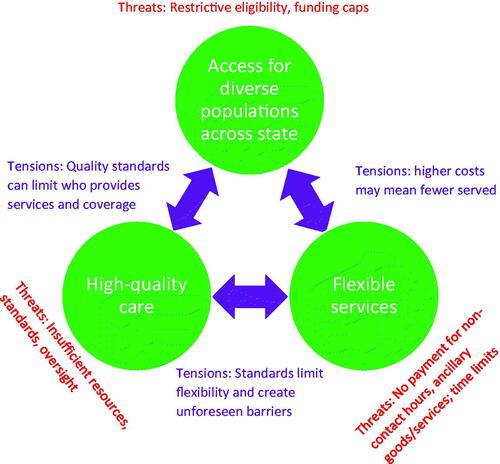

Promoting Access, Quality, and Flexibility

Overall, three needs or goals for the TSS service definition emerged from our interview responses: access, quality, and flexibility. Sometimes these were described by respondents using precisely those words. Other times, without direct use of that language, respondent concerns fell into these categories, such as whether people in rural areas would have enough service providers (access), whether new agencies in the field would understand TSS (quality), or whether regulations would allow services to last as long as was needed (flexibility).Footnote3 An additional theme in our data, as illustrated in , was the tension among these goals. We describe here how these themes are reflected in our data.

Despite some variation in their particular foci, personnel at the NC provider agencies, state agencies, and managed care organizations all expressed concerns about the regulatory environment at the time of the study, citing multiple ways in which funding and oversight were insufficient for achieving access, quality, and flexibility. The total amount of available funding was a particular concern of state and managed care organization respondents, who spoke to the need for greater access to services across the state or in the regions they served. Eligibility requirements were cited as a barrier to accessing services by all types of respondents, but were a particular concern at the mental health agency, because many individuals with mental illness do not meet ACTT’s stringent disease severity requirements.

Respondents also cited a number of deficiencies associated with reimbursement structures. These were for the most part consistent across respondent types and included:

Low reimbursement rates, resulting in large caseloads, hiring of inexperienced staff, inadequate staff compensation, and a limited supply of service providers—affecting both access to and quality of services.

Lack of funding for work that does not involve patient contact, particularly building and maintaining relationships with landlords, which is essential for access to affordable housing—creating barriers to flexibility in and quality of services.

The inability to fund case management services as such through NC Medicaid, which was the result of a scandal surrounding use of case management in the state and the elimination of the Targeted Case Management service definition from the service array in 2012. This was a particular concern at the mental health agency.

Lack of funding for ancillary but necessary expenses such as furniture and toiletries, and money for past arrears (rent and damages), limiting both the quality and the flexibility of services. Even at the homeless services agency, where the availability of funding for their client base was less frequently mentioned as a concern than at the mental health agency, restrictions on how that funding could be used and the need to fund ancillary expenses were prevalent concerns.

Time limits on services that preempt the support needed as clients settle into their new situations—a particularly vulnerable time for housing stability—thereby limiting flexibility and quality.

Reauthorization periods of 90 days for Medicaid, which make it impossible to respond in a timely manner when former clients are in crisis—undercutting access, quality, and flexibility.

Furthermore, stakeholders agreed that quality assurance and oversight of TSS within NC Medicaid had been inadequate to date. This concern was consistent across state officials, managed care organization housing specialists, and agency leadership (although not case managers). The concern of agency leaders is particularly striking, because providers often find oversight to be restrictive. In fact, despite some of the challenges associated with meeting regulatory requirements, the homeless services agency leads expressed positive opinions about HUD oversight. As one respondent put it:

There is certainly a lot of paperwork, but…I don’t think that we have anything that I would say we’re just doing this because we’re told to. Like I think all of it actually serves a purpose that is good for case management…I think that HUD rules are flexible enough that it doesn’t restrict us at all, doesn’t put us into any boxes that we feel like we’re actually spending more time doing this and not enough time with our clients.

In contrast, NC Medicaid pre-TSS expansion was simultaneously seen as inadequate for quality assurance and overly restrictive. One agency lead, for example, described documentation requirements that were onerous and yet not helpful for creating useful case notes.

Not surprisingly, NC stakeholders of all types expected new Medicaid funding for TSS to increase access to services through the creation of a TSS entitlement and incorporation of new populations. More interestingly, they also saw it as a source of improved service quality—through the greater accountability they hoped would be associated with the new payment mechanisms. State- and agency-level respondents from LA indicated that this is precisely what has occurred in that state. Despite some concerns about Medicaid restrictions, both agency leads and state officials in LA indicated that increased Medicaid funding for TSS has increased access to services and—because Medicaid is very specific about what it will cover—has improved quality. Regulations have weeded out service providers who do not understand or are not committed to the work of TSS and resulted in a structure that requires agencies to provide higher quality care more efficiently. Part of the strength of quality assurance in LA is that it is multifaceted and includes random file checks, service monitoring, financial audits, and outcome review (e.g., retention rates, housing transfers).

However, our data surfaced a number of important issues to be considered if Medicaid is to achieve its future potential in NC. Some service definition provisions can be double-edged swords even for a single goal; for example, lower reimbursement of workers can increase access by serving more beneficiaries with less cost per person and simultaneously decrease access by disincentivizing workers and agencies from entering the market. Moreover, goals of access, quality, and flexibility can be in tension with each other. Despite the fact that respondents hoped to see Medicaid enhance both access and quality, they also described concerns about ways in which these goals might undercut each other. Lower service rates, for example, may increase access but also pose a threat to service quality. In another example, respondents in both LA and NC and at the state, managed care organization, and agency levels expressed concern that quality standards can reduce access by excluding or leading to the closing of agencies that are essential service providers in lower-resourced areas of the state. On a similar note, smaller, grassroots organizations (many of which serve people with disabilities) and housing agencies may find it challenging to develop the infrastructure necessary to bill Medicaid, despite their potential to be highly effective in this area—possibly more so than the agencies that already bill Medicaid but have less relevant experience and skills.

Similarly, both access and quality can be in tension with the goal of flexibility. The importance of flexibility in what services can be provided and the duration of services was a consistent theme for personnel at both NC provider agencies and across the two states. The multipronged, evolving, and diverse needs of clients, the challenges of the service context, and the need for creative problem-solving—particularly when trying to make housing work for people with complex needs—make it essential that providers be able to tailor TSS content and duration to the individual. Respondents across the board were also in favor of a Housing First approach, which removes any contingencies (such as sobriety or medication adherence) from eligibility for PSH and has been associated by prior literature with positive outcomes (Hanratty, Citation2011); they noted that Housing First heightens the need for creativity and flexibility. In both states, and at the state, managed care organization, and agency leadership levels, there was concern about Medicaid’s impact in this area, largely because of the tendency for Medicaid to medicalize services and client needs (as highlighted by Carol Wilkins, Citation2015). Even the NC mental health agency, despite providing clinical services, has been active in shaping service definitions to recognize nonmedical needs and allow for nonmedical services. Moreover, whereas Medicaid service definitions generally specify short service duration, respondents of all types stressed the need for many people to have ongoing support services within the first couple of years after obtaining housing and for some people to be supported for even longer periods of time, necessitating regulatory flexibility around service duration. Moreover, the highly prescriptive service definitions that are often used to create accountability in Medicaid can undercut the flexibility needed for creative, client-centric TSS.

A number of respondents had had positive experiences with or were interested in the potential of three specific approaches to increasing accountability that have the potential to truly increase quality and lessen trade-offs with flexibility. In LA, interviewees appreciated the fact that the state routinely solicits feedback from clients on TSS services. One agency official commented, “The monitoring that we do that I kind of feel is most important is…where we actually once a year go out and meet with tenants to hear what their experience in the program is.” In contrast, managed care organization housing specialists noted that in NC client feedback is limited and must be initiated by clients themselves; they indicated an interest in strengthening client input into quality control. Respondents from both NC and LA, particularly at the state level, indicated that more can be done at all levels to use data to improve service quality; there was particular interest in both states in experimenting with outcome-based regulation and the use of financial incentives tied to outcomes. This approach was of particular interest because it gives providers flexibility in what services they provide while holding them responsible for what they achieve with that flexibility.

In addition to oversight, another critical component of quality improvement is staff training requirements. As many respondents noted, getting this right is critical, because training requirements—while potentially increasing quality—can also decrease access by excluding providers and staff from the market and by increasing the cost per person served. Respondents of all types (including clients) and across the two states stressed the importance of hiring for attitudes and character traits that are largely (but not entirely) unrelated to training—a belief in the right of all people to have housing, a passion for the work, creativity, etc. At the same time, agency staff and leadership, managed care organization housing specialists, and state officials overwhelmingly saw a need for some training specifications. Most agreed that there was a need for job-specific training that would not be part of most formal education programs—training on the nature of TSS, housing systems, the Housing First philosophy, and so forth.

There was less agreement on the formal education required to do this work. Notably, given that this is a Medicaid service, there was general agreement that TSS is not clinical and that staff need not all have clinical training. However, NC mental health agency personnel (for logical reasons) and NC state officials cited a need to have some clinicians (particularly licensed clinical social workers) in specialized roles and supervisory positions. Despite the cost to them, LA service providers also stressed the importance of having some clinically licensed staff in order to provide high-quality services.

In sum, study findings indicate that if TSS funding is to achieve its ultimate end of helping people obtain and maintain housing, service definitions must be crafted with an eye to achieving access, quality, and flexibility, and to mitigating the tensions among them. In particular, whereas there is great hope that increased Medicaid funding will improve access and quality, there is also concern that it will decrease flexibility. Respondents expressed an interest in quality assurance approaches—such as client feedback and outcomes-based accountability—that they saw as having the potential to achieve meaningful quality improvement while lessening trade-offs with flexibility, and they promoted training as a critical approach to quality improvement.

Infrastructure

Although we entered into this study focused on the characteristics of a good service definition, an additional theme emerged from our data—the need for a state infrastructure that supports effective TSS. The lessons learned through implementing Medicaid funding for TSS by LA respondents as well as the observations of NC stakeholders indicated that a good service definition is not by itself enough. Rather, a strong state infrastructure is required to achieve the goals of access, quality, and flexibility, and to balance the tensions among them. Four desirable characteristics of state infrastructure emerged from our analysis. As depicted in , these are braided funding, coordination across agencies, a strengthened infrastructure for quality assurance at all system levels, and a state infrastructure for training at all system levels.

Braided Funding

A common theme relative to the provision of accessible, effective TSS was the benefits, and even necessity, of multiple funding sources. Leadership at both NC provider agencies described how access to diverse funding sources allows them to expand the number and type of clients to whom they can provide services, provide a broader array of services, and fund budget components other than direct services, such as administrative work and limited provision of goods. Even in LA, where Medicaid funding has been extensive, it has not eliminated the need for diverse funding. In fact, service providers reported having as many as 20 different funding sources for their work, and both agency leads and state officials noted the importance of this diversity. Diverse funding sources, in essence, reinstate some of the flexibility and access taken away by the regulation and oversight associated with any one funding source—helping to lessen the tensions among access, quality, and flexibility.

For example, Medicaid will only cover direct client contact, prohibiting billing for administrative work, outreach to potential clients, coordination with other service providers, seeking housing, relationship-building with landlords, training and onboarding of providers, or accompaniment of a fellow provider when a client may be violent. As a result, even in LA, with its increased Medicaid funding, covering agency costs is still a challenge. For example, one agency had concluded that an eight-person team plus a supervisor, with a billing rate of $20/h, requires 20–25 h of billable patient-contact time per case manager per week to cover a week’s worth of salary for the team. However, it can be hard to get that many hours of billable time in some weeks, especially when clients do not engage with services. In LA, as in NC, respondents described a need for funds to pay for items other than staff time; for example, paying clients’ past unpaid utility bills and rental arrears prevents past history from being an impediment to obtaining new housing.

On the other hand, having multiple funding sources is not without costs. Service providers in both NC and LA described the significant effort that they expend understanding how different funding sources can be used and carefully monitoring expenditures so as to be in compliance with all requirements. State officials in LA believed that some service providers had left the field primarily because of this challenge.

One of the ways that the state can help service providers handle multiple funding sources is by “braiding” funding at the state level—that is, actively identifying coverage gaps associated with different funding sources, seeking forms of funding that help to fill those gaps, and developing procedures that facilitate the use of multiple funding sources by service providers. In LA, state officials have pursued Community Development Block Grants (CDBGs), Social Service Block Grants, and state funding to supplement Medicaid, and have designed a streamlined requisition process to decrease the billing burden on agencies. State officials are also involved in facilitating braiding of funding for individuals—for example, putting a client on CDBG funding when they have a lapse in their Medicaid funding and are awaiting reinstatement.

Coordination Between Agencies and Providers and Across Agencies

In both LA and NC, state officials—and, in NC, managed care organization housing specialists—cited the benefits of vertical coordination among state agencies, intermediary organizations, and provider agencies. For example, they reported positive results when state agencies have staff who support providers in the field on challenging cases or who step in when there is a temporary lapse in agency services. In LA, where vertical integration is more developed, its importance was mentioned by service providers as well as state officials.

In addition to vertical integration, NC has less horizontal coordination, or coordination across state agencies, than LA. NC state officials mentioned this lack of coordination, and LA state officials and service providers were vociferous about the benefits of horizontal coordination. Leveraging different funding sources to achieve comprehensive coverage requires coordination across the multiple divisions and agencies that receive and/or distribute these funds. Coordination across agencies also allows state officials to play a strong, unified role in collaboration with developers and landlords to make housing available. Moreover, interagency coordination allows state officials to make sure that populations have access to both services and housing and to share effective practices. In fact, LA’s permanent supportive housing program represents a partnership between the state’s Department of Health (providing services) and the LA Housing Corporation (providing housing). CDBG funding, which is an essential component of their funding, is administered by the Department of Health but overseen by the Housing Corporation. Describing the collaboration between the Department of Health and the Housing Corporation, one respondent noted:

People realize that it is a jointly administered program and you can’t go to [one official] and get one answer and go to [another official] and get another answer. We actually work together…. There’s no wrong door to any issues that anyone should have with our permanent supportive housing program. I’m never going to turn anybody away and say you need to go talk to [another official].

As with braided funding, coordination helps not only to improve the program and program context overall, but also to meet the immediate needs of individual beneficiaries; both vertical and horizontal coordination can help with this. For example, when a client’s Medicaid coverage ends but the provider agency working with them is not receiving CDBG funding, the LA Department of Health, the Housing Corporation, and the provider agency coordinate to prevent a lapse in services.

Quality Assurance Infrastructure at All System Levels

NC state-level respondents were aware that the desire for stronger quality assurance in NC Medicaid requires a significant enhancement of both state and managed care organization infrastructure. This is particularly true if new approaches such as client feedback, outcomes-based assessment, and other novel uses of data are to be employed, requiring new procedures, skill sets, and technical capacity.

Moreover, agency leads, managed care organization housing specialists and state officials in NC were concerned not only about insufficiency of accountability for providers, but also what they saw as insufficient accountability of the managed care organizations to the state. Improving quality assurance at this level is not a function of the service definition; rather, it requires a change in the managed care organization and state infrastructure supporting TSS. One respondent commented, “So I think it is fair to say from the Department of Health and Human Services on down to the provider we need to strengthen the contract, we need to strengthen guidance, we need to strengthen, you know, really the whole gamut.”

Technical Assistance and Training at All System Levels

Although the importance of quality assurance was a prevalent theme in our data, some respondents noted that oversight by itself does not produce quality and that training is critical, particularly because they saw many of the skills and knowledge involved in effective TSS as lying outside of formal education. In the words of one state official, “Even now they do the fidelity reviews it’s still that issue of staff not getting it.” In NC, effective agencies often train their own workforce because they see the external trainings available to them as insufficient and not detailed enough for their staff. Our data revealed multiple reasons for the state to provide or arrange training. First, having each agency train its own staff is expensive and will be insufficient to support the workforce expansion required to match the new funding. If agencies have to train their own staff in order to improve service quality, many will be unable to participate. State-provided training therefore mitigates the trade-off between access and quality. This need was mentioned by agency leadership, state officials, and managed care organization respondents in NC. In LA, the state provides a great deal of workforce training, which was cited by both service providers and state officials as a critical element of their success.

Second, state-provided training is necessary because training is required at the agency, regional, and state levels as well as for front-line staff. LA officials have recognized the importance of training agency administrators and other specialized staff in addition to case managers and have focused these efforts on helping agencies to succeed at providing effective services, billing and complying with Medicaid, and managing the complexities of having multiple funding sources. In fact, they require that all agencies participate in what they call “Permanent Supportive Housing 101” and offer agencies ongoing technical assistance. With this requirement, LA has contributed to quality improvement not only by making training easily available to agencies, but also by incentivizing (actually, requiring) engagement with this training. In part, this is a response to experiences during the early days of Medicaid funding:

I think for folks on the behavioral health end when, you know, they went from a funding that had some loose criteria to very specific, you know, having it all be face to face and then we’re transporting people. It’s like, okay, but when you’re in the car with someone, what are you doing, what are you talking about? Are you talking about hey, let’s talk about what’s going on? Like, just getting people to understand something that they are doing is billable and you weren’t billing for it or, you know, how do you minimize your time on doing the things that aren’t billable but also making sure someone’s getting what they need?

Respondents from both states noted that having adequate ongoing training, guidance, and technical assistance for provider agencies can simultaneously promote service access and quality by helping agencies meet requirements and meet them well.

Respondents also indicated that managed care organizations and state agencies need training as they move into new territory. One NC managed care organization respondent argued that it is only recently, with the creation of the Transitions to Community Living Initiative, that their employers really understand what it takes to house people:

For the first time ever I think that people are seeing within the managed care organization and without that housing's a really technical field. There’s, you know, so many different subsidies and there's laws attached to it and, you know, like we all cover huge areas with different counties and different zoning, and we have to be aware of all of that different stuff throughout our catchment area.

Similarly, the new demands on state government for achieving and balancing goals of access, quality, and flexibility require learning from experiences of other states. In the words of one LA state official, technical assistance from national experts has been “instrumental” for them; even now, with many years of experience behind them, they still confront new circumstances for which they don’t have the answers.

Whereas many consultants and other entities have developed TSS training, one LA respondent asserted that it is critical that training in their state was tailored to address their specific conditions, rather than being “off-the-shelf” training from a national organization. Moreover, even providing such “off the shelf” training and incentivizing its use—particularly at the scale that will be needed with the expansion of Medicaid-funded TSS—requires the development of a state infrastructure that currently does not exist in NC or, presumably, many other states.

Discussion

Summary of Findings

This study compared data from agencies from different TSS provider sectors (homelessness services and mental health) and different geographic regions of NC. The expansion of Medicaid funding for TSS has different implications for these agencies, as one is already primarily funded by Medicaid and the other by HUD. Nonetheless, our comparative case study analysis indicated striking similarities between the perspectives on funding and oversight of personnel at these two very different agencies. Moreover, these perspectives were congruent with those of state officials and the managed care organization (MCO) housing specialists. Furthermore, hopes and concerns articulated by NC stakeholders as they looked to the future aligned with the story that LA stakeholders had to tell about the lessons they had learned in the past and were still learning about creating a regulatory and funding environment that promotes effective TSS.

Overall, our findings indicate that, as states move to develop new service definitions associated with increased Medicaid funding for TSS, three goals must be prioritized for the TSS sector: access to care across the state for diverse populations, provision of high-quality services, and the flexibility to meet the needs of individual beneficiaries. States need to balance tensions and trade-offs among these goals, not only through service definition choices, but also through the creation of infrastructure that can mitigate these trade-offs.

Implications of the Study for the Regulatory and Funding Environment

We would certainly be misguided if we were to believe that our research—even if combined with the research of others—allows us to “prescribe” a Medicaid TSS service definition. There are cost considerations, political considerations, and other specific contextual realities that policymakers must take into account and know far better than we. However, we hope that the access–quality–flexibility tension framework provides a useful way for decision makers to think about their choices. In particular, this analysis elevates the importance of experimenting with approaches to service definition and infrastructure design that seem to mitigate rather than exacerbate tensions among these goals. Based on our data, examples include:

Client-informed and outcomes-based quality assurance that have the potential to maintain flexibility while improving quality. (The push toward outcomes-based quality assurance has, of course, been a larger trend in health and social services in recent years, including attention to its own attendant challenges (Averill et al., Citation2016)).

Substitution of formal education requirements with job-specific training requirements where possible (with the recognition that a specific educational background is required within the team, but not for all members), to reduce barriers to market entry and increase access while also increasing quality.

Provision of job-specific and agency training by the state, further reducing barriers to market entry while enhancing quality.

State involvement with braided funding to optimize access, quality, and flexibility without making the administrative burden an obstacle to market participation for provider agencies.

Vertical and horizontal coordination across the service sector to develop a comprehensive spectrum of care, align strategies that improve access to and quality of services, marry housing and service access, and create the flexibility to meet the needs of diverse individuals.

Another policy implication of our study is the necessity to find a way of dealing with the ebb and flow, likely long duration, and unpredictability of TSS needs. This can be accomplished through longer eligibility periods, easier and faster reauthorization and reinstatement processes, and/or braided funding and care coordination approaches that allow for the application of quick stopgap funding.

A surprising finding from our study was the association of Medicaid funding with quality improvement. When even provider agency leadership welcomes greater accountability, it speaks to the importance of attending to this concern, albeit with attention to the access and flexibility trade-offs that can result. On a related note, policymakers must go beyond thinking about training and quality assurance for front-line providers and make sure that these needs are also met at the provider agency level, for the state agencies administering TSS programs, and for any intermediary organizations involved (such as the MCOs in NC).

Relationship of Study Findings to the Existing Literature

Some of the specific hopes and concerns for Medicaid funding raised in our study have been identified in the existing literature as well, particularly the need for flexible sources of funding to pay for the services and individuals not covered by Medicaid; the challenges for provider agencies of meeting Medicaid requirements; and the need for more training to transform current Medicaid providers into TSS providers and transform current TSS providers into Medicaid providers (Burt et al., Citation2014; CSH, Citation2021; Paradise & Cohen Ross, Citation2017; Wilkins, Citation2015). Like the work of Clary and Kartika (Citation2017), our study points to the value of braided funding to meet the needs of a diverse population, cover all costs, and minimize the time that clients are without needed services. Other findings align with prior research on TSS outside the realm of Medicaid. In particular, the literature documents a wide diversity of client needs (Tiderington et al., Citation2020; Wright & Rubin, Citation1991) and demonstrates that demands from the regulatory/funding environment can undercut the flexibility needed for effective TSS and a true Housing First approach (van den Berk-Clark, Citation2016).

There are other findings that we have not seen elsewhere, particularly the universal enthusiasm—even among providers—for the greater accountability and higher quality of services they see as associated with Medicaid funding. (Interestingly, although personnel at the homeless services agency in our study recognized that new Medicaid funding would require some changes of them, even there we did not see the level of apprehension about this change that has been found elsewhere (Thompson et al., Citation2021).) Thompson et al. (Citation2021) noted the importance of horizontal coordination between government agencies overseeing the healthcare and homeless services sectors (as well as among the on-the-ground agencies in these sectors). Our data provide insight into what this coordination has looked like in LA (not one of the states studied by Thompson and colleagues), and also stresses the importance of vertical coordination within the TSS arena. Finally, we hope that the access–quality–flexibility tension and infrastructure frameworks that emerged from our analysis provide a useful way of thinking about the more specific issues addressed in the study.

Future Research

We see a number of implications of our study for future research and evaluation. The access–quality–flexibility tension framework provides one possible conceptual model for program and policy evaluation. Moreover, it speaks to the importance of studying service definition and infrastructure approaches (like those detailed above) that have the potential to mitigate trade-offs. Finally, we propose that the presence, absence, and nature of the four infrastructure characteristics laid out here be understood as salient dimensions of the state context when making cross-state comparisons of TSS services.

Study Limitations and Strengths

This study focused on TSS to the exclusion of affordable housing. PSH requires both elements. The focus of this study on TSS alone should not detract from the reality that a lack of housing is a limiting factor for the success of tenancy support. Data on TSS outcomes from our larger study (paper in progress) indicate that TSS can increase the willingness of developers to expand affordable housing and to the willingness of landlords to rent to individuals who have been without homes or lived in institutional settings. TSS can be not only the needed complement to affordable housing, but also a contributor to housing availability. Clearly, however, this is only a small part of the solution to our national affordable housing crisis.

A methodological limitation of this study is that it included only two states, with intensive data collection from two high-performing agencies in one of those states, potentially limiting the transferability of findings. A particularly important aspect of the NC context is the failure to expand Medicaid under the terms of the Affordable Care Act. It is for this reason that Medicaid-funded TSS in the state is likely to be associated with PSH, rather than Rapid Rehousing, leading us to focus this study on TSS within the context of PSH.

Nonetheless, the commonality of themes across two very different agencies and across two states indicates the need for service providers and policymakers to seriously consider the issues raised here. This study, together with other literature, provides a platform for important conversations about funding needs, standards for TSS service definitions, institutionalization of training and technical assistance, quality assurance, and infrastructure development across the United States.

Conclusion

As Medicaid funding is applied to services addressing concerns such as homelessness and institutionalization, policymakers are faced with the challenge of designing effective regulations to address nonmedical needs. Medicaid funding has expanded considerably for TSS, but states have a number of decisions to make that will affect the impact of these funds on service delivery and outcomes. The study findings reported here indicate that, as they increase the use of Medicaid funding for TSS, states need to prioritize the three goals of access, quality, and flexibility; be attentive to the trade-offs among them (particularly the potential negative impact of Medicaid on flexibility even as it can improve access and quality); and find ways to mitigate those tensions. Using approaches to quality assurance such as client feedback and outcomes-based accountability can reduce some of these tensions, as can emphasizing job-specific training. The right state infrastructure can also promote these goals and lessen trade-offs. Our research suggests that an enabling state infrastructure includes braided funding, vertical and horizontal coordination across agencies, a strengthened quality assurance infrastructure that addresses all levels of the TSS sector, and the infrastructure to develop, provide, and incentivize technical and training assistance for everybody, from the those on the front lines to the state agencies responsible for this service.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge our Consumer Advisory Council, who gave of their time and expertise to strengthen our tools for understanding tenancy support services.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mina Silberberg

Mina Silberberg is an associate professor in the Department of Community and Family Medicine at Duke School of Medicine, vice-chief for research and evaluation in the department's Division of Community Health, and a faculty affiliate in the Duke Council on Race and Ethnicity. Prior to coming to Duke, she was a senior policy analyst at the Rutgers Center for State Health Policy. Her research focuses primarily on program and policy evaluation for community health. She received her doctorate in political science from the University of California at Berkeley.

Donna J. Biederman

Donna J. Biederman is an associate professor at the Duke University School of Nursing (DUSON) and the Director of the DUSON Community Health Improvement Partnership Program (D-CHIPP). Her research and programmatic interests intersect with housing and health care, including transitional care for homeless people exiting institutional settings and the health correlates of eviction. She is a coprincipal investigator for the Durham Homeless Transitions Care program where she is the research, evaluation, and education lead. She was an emergency department nurse and then a case manager at a federally funded Health Care for the Homeless Clinic prior to completing her DrPH at the University of North Carolina Greensboro.

Emily Carmody

Emily Carmody is a founding partner with Redesign Collaborative, LLC. Prior to forming her technical advisory firm in 2021, she was a program manager at the North Carolina Coalition to End Homelessness (NCCEH), a statewide membership nonprofit that works to end homelessness by creating alliances, encouraging public dialogue, securing resources, and advocating for systemic change. She served as the state lead for the NC SOAR program and advised on projects including health and human services and technical support for continuums of care. Prior to working at NCCEH, she worked in homeless services for 10 years in Connecticut, Washington, DC, Michigan, and North Carolina and received her master’s in social work from the University of Michigan in 2007.

Notes

1 Calculated using HUD PIT data (HUD, Citation2020).

2 For reasons that are explained later in the paper, “case manager” is a problematic term in the NC context. Different agencies use different terminology. We have used “case manager” here to be easily understandable.

3 We recognize that from the point of view of funders and the larger society, there is also a need to control the costs of TSS. Our questions were about what it takes to achieve effective TSS and hopes and desires for Medicaid; access, quality, and flexibility were the overarching themes of responses to those questions. Certainly, the need to control costs is a contextual reality that heightens the challenge of achieving these goals and mitigating the trade-offs among them.

References

- Averill, R. F., Fuller, R. L., McCullough, E. C., & Hughes, J. S. (2016). Rethinking medicare payment adjustments for quality. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 39(2), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAC.0000000000000137

- Bassuk, E. L., & Geller, S. (2006). The role of housing and services in ending family homelessness. Housing Policy Debate, 17(4), 781–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2006.9521590

- Benston, E. A. (2015). Housing programs for homeless individuals with mental illness: Effects on housing and mental health outcomes. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 66(8), 806–816. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400294

- Brush, B., Gultekin, L., & Grim, E. (2016). The data dilemma in family homelessness. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 27(3), 1046–1052. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2016.0122

- Buchanan, D., Kee, R., Sadowski, L. S., & Garcia, D. (2009). The health impact of supportive housing for HIV-positive homeless patients: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health, 99(S3), S675–S680. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.137810

- Burt, M. R. (2012). Impact of housing and work supports on outcomes for chronically homeless adults with mental illness: LA’s HOPE. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 63(3), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100100

- Burt, M. R., Wilkins, C., & Locke, G. (2014). Medicaid and permanent supportive housing for chronically homeless individuals: Emerging practices from the field. Report to ASPE, August 9, 2014.

- Byrne, T., Fargo, J. D., Montgomery, A. E., Munley, E., & Culhane, D. P. (2014). The relationship between community investment in permanent supportive housing and chronic homelessness. Social Service Review, 88(2), 234–263. https://doi.org/10.1086/676142

- Cantor, J. C., Chakravarty, S., Nova, J., Kelly, T., Delia, D., Tiderington, E., & Brown, R. (2020). Medicaid utilization and spending among homeless adults in New Jersey: Implications for medicaid-funded tenancy support services. The Milbank Quarterly, 98(1), 106–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12446

- Clary, A., & Kartika, T. (2017). Braiding funds to house complex Medicaid beneficiaries: Key policy lessons from Louisiana. National Academy for State Health Policy. Braiding-Funds-Louisiana.pdf (nashp.org)

- Collins, S. E., Malone, D. K., Clifasefi, S. L., Ginzler, J. A., Garner, M. D., Burlingham, B., Lonczak, H. S., Dana, E. A., Kirouac, M., Tanzer, K., Hobson, W. G., Marlatt, G. A., & Larimer, M. E. (2012). Project-based Housing First for chronically homeless individuals with alcohol problems: Within-subjects analyses of 2-year alcohol trajectories. American Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 511–519. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300403

- CSH (Corporation for Supportive Housing). (2021). Summary of state actions: Medicaid and housing services. Policy Brief. Summary-of-State-Action_-Medicaid-and-Supportive-Housing-Services-2021-08.pdf (csh.org)

- CTSA Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement (2011). Principles of community engagement. (2nd ed.). National Institutes of Health.

- Culhane, D. P., Metraux, S., & Hadley, T. (2002a). Public service reductions associated with placement of homeless persons with severe mental illness in supportive housing. Housing Policy Debate, 13(1), 107–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2002.9521437

- Culhane, D. P., Metraux, S., & Hadley, T. (2002b). The impact of supportive housing for homeless people with severe mental illness on the utilization of the public health, corrections, and emergency shelter systems. Housing Policy Debate, 13(1), 107–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2002.9521437

- Dennis, D. L., Levine, I. S., & Osher, F. C. (1991). The physical and mental health status of homeless adults. Housing Policy Debate, 2(3), 815–835. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1991.9521073

- Hanratty, M. (2011). Impacts of Heading Home Hennepin’s Housing First programs for long-term homeless adults. Housing Policy Debate, 21(3), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2011.594076

- Henry, M., de Sousa, T., Roddey, C., Gayen, S., Bednar, T. J., & ABT Associates (2021). The 2020 annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to Congress. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2020-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

- Henwood, B. F., Katz, M. L., & Gilmer, T. P. (2015). Aging in place within permanent supportive housing. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(1), 80–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4120

- Homeward Bound (2021, August 16). Homeward Bound receives grant to offer financial incentives to landlords. https://mountainx.com/blogwire/homeward-bound-receives-grant-to-offer-financial-incentives-to-landlords/

- HUD (2020). CoC homeless populations and subpopulations reports. HUD. https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/coc/coc-homeless-populations-and-subpopulations-reports/?filter_Year=2016&filter_Scope=CoC&filter_State=NC&filter_CoC=&program=CoC&group=PopSub

- Lambert, S. D., & Loiselle, C. G. (2008). Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(2), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x

- Mackelprang, J. L., Collins, S. E., & Clifasefi, S. L. (2014). Housing First is associated with reduced use of emergency medical services. Prehospital Emergency Care : Official Journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors, 18(4), 476–482. https://doi.org/10.3109/10903127.2014.916020

- Martinez, T. E., & Burt, M. R. (2006). Impact of permanent supportive housing on the use of acute care health services by homeless adults. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 57(7), 992–999. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.992

- NASEM (2018). Permanent supportive housing: Evaluating the evidence for improving health outcomes among people experiencing chronic homelessness. The National Academy Press.

- Olmstead v. L.C., 527 U.S. 581, (1999).

- Paradise, J., & Cohen Ross, D. (2017). Linking Medicaid and supportive housing: Opportunities and on-the-ground examples. Report of Kaiser Family Foundation.

- PARC (2020). Community & work disparities: A program of the ADA participatory action research consortium. ADA-PARC. https://www.centerondisability.org/ada_parc/utils/indicators.php?id=1&palette=3

- Rieke, K., Smolsky, A., Bock, E., Erkes, L. P., Porterfield, E., & Watanabe-Galloway, S. (2015). Mental and nonmental health hospital admissions among chronically homeless adults before and after supportive housing placement. Social Work in Public Health, 30(6), 496–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2015.1063100

- Rog, D. J., Marshall, T., Dougherty, R. H., George, P., Daniels, A. S., Ghose, S. S., & Delphin-Rittmon, M. E. (2014). Permanent supportive housing: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 65(3), 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300261

- Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research a menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907313077

- Silberberg, M., Biederman, D. J., & Carmody, E. (2019). Joining forces: The benefits and challenges of conducting regulatory research with a policy advocate. Housing Policy Debate, 29, 475–478.

- Thompson, F. J., Farnham, J., Tiderington, E., Gusmano, M. K., & Cantor, J. C. (2021). Medicaid waivers and tenancy supports for individuals experiencing homelessness: Implementation challenges in four states. The Milbank Quarterly, 99(3), 648–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12514

- Tiderington, E., Petering, R., Huang, M., Harris, T., & Tsai, J. (2020). Expert perspectives on service user transitions within and from homeless service programs. Housing Policy Debate, 30, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1825012

- van den Berk-Clark, C. (2016). The dilemmas of frontline staff working with the homeless: Housing First, discretion, and the task environment. Housing Policy Debate, 26(1), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2014.1003142

- Wachino, V. (2015). CMS informational bulletin: Coverage of housing related activities and services for individuals with disabilities. Center for Medicaid & CHIP Services (CMCS) Informational Bulletin. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Wilkins, C. (2015). Connecting permanent supportive housing to health care delivery and payment systems: Opportunities and challenges. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 18(1), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487768.2015.1001690

- Wright, J. D., & Rubin, B. A. (1991). Is homelessness a housing problem? Housing Policy Debate, 2(3), 937–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1991.9521078